The Wellcome Library in London holds an extensive archive of clinical notes, papers, images, and other materials of the pioneering psychoanalyst Melanie Klein (1882-1960). The Melanie Klein Trust’s Archivist, Christine English, offers us glimpses into Klein’s thoughtas she explores this rich trove of material, continuing the work of the blog’s originator, Jane Milton.To learn more about Klein's life and work, visit the Melanie Klein Trust website.For more on Klein's archive at the Wellcome, and to view materials online, click here.The blog is now also being translated into Russian. To visit the Russian version click here.Блог переводится на русский язык – русская версия здесь.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

‘Anxieties of persecution inside and outside’: Klein’s self-observation after an operation

4th July 2025

This is a guest blog by Margherita Margiotti, a psychoanalytic psychotherapist with a deep interest in the theoretical and clinical contributions of Melanie Klein.

PP/KLE/C.95 is an interesting file. It is at once autobiographical and rich in theoretical value, as has been pointed out by various scholars, notably by Claudia Frank (2020).* It can be found in the ‘Manuscripts’ section of the digital archive, and consists of fifteen typed pages. It was likely written in 1937 after Klein had her gallbladder removed, and contains her close observations of her feelings and states of mind after this surgical procedure.

Klein describes two dreams that she has whilst in hospital, and reflects on the infantile phantasies and paranoid anxieties which are revived, post-operation, by her state of physical discomfort, internal pain, and childlike dependency on those giving her medical care. As she writes, she is ‘doing a lot of work with myself’, and in the process comes to a better understanding of her own ‘internalised processes’ and ‘fears of inner destruction and persecution’. She also notices that her usual capacity for contact with ‘people and things’ was altered by the operation.

The file starts with Klein expressing surprise about having ‘nothing but a feeling of anger’ as she emerged from the effects of the anaesthetic. She was in pain, she felt suspicious, and her usual interest in other people and gratitude for their help were disturbed. She felt grateful for their visits and for the flowers she received, yet was also withdrawn: she was ‘lost somewhere and couldn’t get out of it’. She writes:

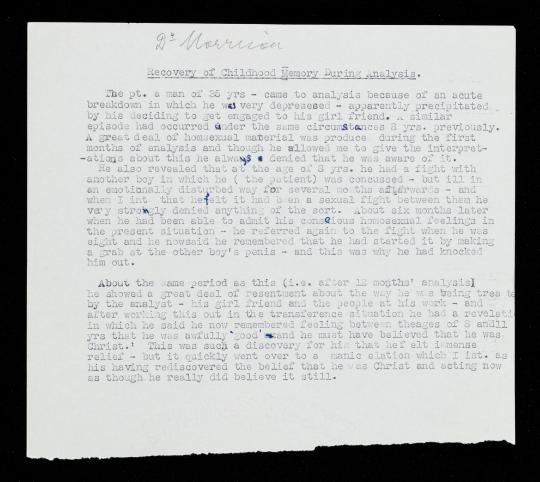

This feeling of anger, dissatisfaction with the world, persecution, was rather striking at the time, in contrast to my actual appreciation that it had all being done so easily, quickly, without my knowing it, my recognition of people’s helpfulness and my pleasure that it was over. [Image 1/15]

In pain, she felt like ‘the little girl who felt so persecuted by something having been done to her without her knowing what it was’. She writes:

On the fourth day I observed the sun shining on the brick wall, which was all I could see from my bed. I felt very pleased with this sunshine, but discovered that I tried to strengthen these feelings of pleasure, suddenly realizing that this whole sunshine on the wall was absolutely artificial and untrue to me. A realization of a feeling of loss of reality and of something which I could not define came over me, and I found that I was trying to regain relations which had been broken off. Also there was a relation with grief and the ways of overcoming grief. [3/15]

Klein notes that she began to recover her appetite and found that she greatly disliked hospital food. After she was given some fish to eat, she had a dream about an enormous and frightening fish. She writes that there was ‘something about my sucking or wanting to suck this fish, and then it turning into something very terrifying’, and then recalls some waterfalls and there being ‘an important reason to shut a door against the dangers of this water’. In the dream, someone was meant to shut this door but did not.

Her associations to the fish are to a ‘good and motherly figure’ who turns dangerous. Meanwhile, her associations to the person who is meant to close the door are to a fatherly figure who could have been benign and helpful, ‘but I felt I could not rely on him at all, and everything seemed to go wrong’.

In exploring the dream, Klein makes a number of references to persons and situations in her life which have brought her great pain. However, she stresses that the dream’s importance lies not so much in its reference to external events but rather to ‘deep anxiety situations connected to the inside’, and to a paranoid, dangerous internal situation where ‘all these things went wrong inside me’. On the following night, another dream confirmed her ‘strong feelings’ of things blowing up inside, and her fears of her internal objects deserting her, as she dreamt of ‘a bathroom with the bath tub turned up, gas blowing up and everything going to bits’.

On page five, in a handwritten note, Klein points the reader to ‘further additions and associations to this material on pp. a-g’. In these pages, she follows her insight regarding the ‘deep anxiety situations’ and further works on her associations.

At the beginning of this insert, she considers another detail from the dream, the sun shining through rocks in the water, and realises that ‘I tried to make contact with the world again and to think it is all very nice and pleasant, but in the dream I catch myself with the feeling "Do I not try now to make this much nicer because really I am afraid of all that?"' Here, Klein is grappling with the very frightening impact of an invasive procedure, which has made her feel vulnerable and at risk in the world, while returning her to a state of childlike dependency in the form of the hospital care she is receiving.

She further thinks about the male figure who failed to ‘stem the tide’ and ‘shut some door’, and remembers another detail about a ‘certain compartment to be kept water-tight’. She links this to internal processes:

…this shut door, this compartment, keeping watertight, really meant keeping my internal objects separate from each other, which was however so difficult because the good ones were entirely unreliable [7/15].

Klein links this to the surgeons whom she ‘tried so much to keep as helpful objects, because otherwise they had just injured and done harm to me’, and also to the feeling that something sinister was ‘behind the beauty, which I tried to cling to’. Similarly, the fish, which initially she told herself was nice, grew into a monster, jumped out of the water and sucked her lips. Klein sees here her own projections, her ‘intense and dangerous attacks on [the] breast with my teeth and intensely sucking mouth’.

At this point, her thoughts about oral greed, frustration, and infantile sadism in relation to the breast, connect to a ‘detail of my history which I have been told, of the fit I had when I was 10 months old, in which I went blue, and my uncle ran for the doctor because it seemed so serious’. Klein had been given a pastry by her wet nurse and, presumably, had choked on it. She links her ‘sinister’ feeling about this event to her ‘guilt and fears about the rage and anger and sadism which must have gone along with this fit’.

Klein then reflects on other situations in her life of disappointment, sorrow, and pain, including in relation to her father. Again, she connects this to the surgeon who represents a good father, but who, as the dream shows, is not fully trusted. She remarks how present and past history are relevant as they are ‘all internalised’. I think that here she is referring implicitly to the relevance of unconscious phantasies and their meanings, which become accessible to her through her dreams and associations. She writes:

Now this feeling of these objects being internalized I never had as strongly as in this dream. It really opened my eyes so very much to things which I had repeatedly seen in patients but not experienced so strongly about myself. This vivid feeling of internalized processes was of course strengthened and stimulated by the actual discomfort inside me, but on the other hand that just helped me to understand the meaning of this internal discomfort [10/15].

With some surprise and, I think, relief, Klein finds that her hard associative work has altered her mental state. She recovers ‘greater contact with things and people’ and in a stronger way, with people appearing to her as ‘more real, more trustworthy, less vague, ephemeral’.

The insert ends with Klein writing:

I had the feeling, which I have again noticed so often in patients and which stands for a memory, in which a feeling appears as if it had been so in early childhood. Now this revival of a feeling which I experienced meant the early stages in which I tried to cling to people (such a strong feature in my early life, strong clinging to objects) against these fears of inner destruction and persecution [12/15].

Returning to her main notes, Klein writes of her sense of people becoming more real to her:

I felt that the relations to people became more real, the world less artificial, and that deep anxiety situations connected with the inside had, as it were, cut off my relation with external objects. It is, of course, more complicated than this, because I felt very strong gratitude and a very friendly relation to the surgeon, who came to see me every day, and who even seemed to take great interest in some of the psychological aspects which I discussed with him, and who said, quite spontaneously and before I gave him such details, that he feels sure that extremely early fears are stirred by an operation; that it takes one back into quite early times, and that in his view, to recover from an operation is more determined by mastering it psychologically than physically [5–6/15].

Klein notes that she was doing ‘a lot of work with myself at this time’, working hard on deep anxieties about the ‘loss of belief in internal and external objects’, and experiences that had ‘overwhelmed, cut open, attacked from within’. Although grateful to medical professionals and to those coming to visit her, she also felt grief and a deep longing for those she had already mourned in her life, as well as increased feelings of being hurt. Klein describes these feelings as similar to mourning, the ‘great sensitiveness [sic], very strong resentment for the slightest thing’ experienced ‘like a psychological assault’.

Concluding these notes, she writes:

The work I did with myself showed me how, when I could bring out to consciousness these deep anxieties of persecution inside and outside, I regained my balance, trust in external people, relation with them, while the internal situation had improved. I am convinced that what is called a ‘shock to the system’ is a revival of earliest internal anxiety-situations, due to what is felt to be an attack from without and within through the operation, and internal discomfort and pain reviving the early fears of internal persecution. The effect of the work I could do myself on this line was very striking to me [15/15].

I think this file is a fine illustration of Klein’s thinking about ‘deep anxieties of persecution inside and outside’, and about the link between somatic internal states and unconscious phantasies. Claudia Frank (2020) highlighted the file’s theoretical value in a very interesting article (currently only published in German), arguing that it represents a ‘building block on the way to the concept of the paranoid-schizoid position’. She makes an important point that one might consider in relation to both Klein’s life and her clinical work: Klein had lost her eldest son in 1934, and then in 1935 she formulated her radical new concept of the depressive position. When she wrote ‘Observations after an operation’, Klein had already encountered in her child patients very violent states, paranoid feelings, and powerful splitting and projection. In her work with adult patients, she similarly encountered states of enormous guilt and persecution, which she linked to depressive anxieties. Thus, paranoid anxieties and schizoid mechanisms were already evident in her clinical work long before she took the conceptual leap of formulating the paranoid-schizoid position, which she theorised is a feature of normal infantile development as well as more pathological states.

This file is a short one, and if readers want to approach it they will find good evidence of Klein’s conviction that working on internal states leads to greater contact with, and appreciation of, reality; and, moreover, that gratitude follows from this.

---

* Frank, Claudia, 2020, “I was doing a lot of work with myself”. Zu Melanie Kleins unpublizierten Beobachtungen nach einer Operation (1937). Luzifer-Amor. 33(65):154–168.

See also: Barratt, Harriet (2021) ‘Strong clinging to objects’: materiality and relationality in Melanie Klein’s Observations after an Operation (1937). Wellcome Open Research, 6; p.40.

0 notes

Text

Material illustrating fear of integration

12th December 2024

In file B.98, titled ‘Theoretical thoughts’, I’ve found some interesting and somewhat unusual clinical material about a patient ‘E’, dated 15th April 1947. E is not so ill, but his case helpfully illustrates some implications of the projection of parts of the personality. Klein records that this patient is ‘well adapted and integrated’, and ‘intellectually, and also to some extent emotionally, interested in analysis’. However, ‘again and again it appears there seems to be no deep need for it’. One reason for this, Klein notes, is his ‘particular way of splitting emotions’, something which may be ‘very characteristic for normal well-developed people’ [Image 73/152].

Klein then cites the following:

Dream material in which two little orphans have entered, as well as other material, showed that the unhappy wretched part of his personality had been projected outwards…[and] had become the basis for the particular interest he took in helping certain people. For instance, adolescent problems about masturbation did not arise in him consciously, but he was very interested in helping other boys to deal with them. By means of this splitting off and projecting into other people the anxious, suffering part of his personality, he managed to develop in a very integrated way another part of his personality, which is in many ways mature and integrated. [73/152 and 75/152]

Klein notes a certain of lack of emotion in E, though ‘not great enough to make it pathological or to impede too much the personality.’ She remarks that emotions haven’t only been projected outwards, but have also been ‘distributed away from the original conflicts and relation[s]’.

She writes:

Now it has often appeared that in spite of his great interest in analysis, there is as well a strong detachment from it, which is a defence, the danger being that he will be confronted with this suffering and conflicts which he had avoided by this particular mechanism of projection. [75/152 and 77/152]

Whilst E does in part want to get to know his unconscious, Klein stresses that he also feels it to be something very dangerous, something ‘equate[d] with anxiety’. She interprets this, and in response E says, ‘what else could it be?’ In the session that follows, E brings a dream; a ‘very ambitious dream’, according to Klein:

There was a pageant with beautiful chargers on which people were racing up a hill – it was a race. One of the chargers had fire coming out of its nostrils: It was a beautiful sight. [One] particular rider got ahead of everybody and got first up the hill, but the fire spread and he set on fire a building which was on top of the hill. However, it turned out to be only cardboard and of course it did not matter. [77/152]

Another dream fragment – part of the same dream – is recorded by Klein as follows:

[…]a party was going on, and the hostess had some features which reminded him of the analyst. There was some disappointment regarding the party, and it could all be linked with dissatisfaction in the analytic relation, which was not giving the satisfactions which were asked for in this dream and on other occasions. [77/152 and 79/152]

Klein interprets that E is the rider on the charger who gets ahead of everybody. He is quite pleased with this and, according to Klein, ‘seemed quite aware of his own ambition and his wish to get ahead of his rivals.’ She also suggests that she is the hostess of the party, that,

I lived in Clifton Hill, that the fire was in my house, and that the danger of setting fire – the destructive part of his ambition – was instrumental in making the house into a cardboard house, that is to say no value attached to it and therefore no danger. [79/152]

E has some associations to the fire: he recalls once thinking a fire may have been started in his own home, and though he quickly realised that he had merely seen the embers of a fire in the hearth, he had been ready to act. He also thinks of ‘a love experience in front of the fire with great gratification and love’, and he links this to the fire in Klein’s hearth. Klein writes, ‘it became clear that unconsciously the analyst had been part of this love experience’. Further,

In the hours following this particular dream material, he associated [to a] radio play [and] some search for treasures, and to his own surprise associated the quiet fire with the treasures, which would be good if [the search] were not so driven by ambition, hatred and rivalry. [81/152]

E also associates to the relationship he has with his mother, and to his anxiety about her being ill. Klein notes that this connects to a ‘fear of loss, which was very great, though unconscious, in his childhood’. She links,

…the quiet fire, the hidden treasure now experienced in relation to K* in this particular gratifying experience, with the hidden treasures in the unconscious, the love feeling which had been buried and which he was longing to find, though anxiety and other feelings were working against these discoveries in the unconscious. [81/152 and 83/152] (*Klein usually refers to herself in the third person in her clinical notes, often abbreviated as ‘K’.)

It seems that this interpretation makes quite an impression on E, for his mood changes significantly. Klein notes that, ‘He felt grateful and co-operative on this aspect of his unconscious’. However,

Suddenly a Frankenstein monster came up as an association. This Frankenstein was a scientist who had been able to bring together out of the skeletons of several criminals a whole being which was a monster. When I asked him if he knew why this association came up in the middle of this peaceful and helpful mood, he could not say. K’s suggestion was that finding the hidden treasures in the unconscious [suddenly felt] very frightening…that K was the scientist who was mobilising inside himself ideas which, though linked with feelings of love, are also connected with dangers and desires which would have led in the past to dangerous situations in relation to mother and father, and which now in his mind are experienced in connection with K. He pointed out how suddenly the dangerous and frightening aspect of analysis had come up in his mind, but, at the same time, the feeling of having lost treasures by his methods of dealing with the unconscious had also appeared in the same hour. [83/152 and 85/152]

Klein is highlighting in this material E’s fear of the return of split-off parts of his personality, which analysis threatens to put him back in touch with; his ambition and rivalry, but also his loving and desirous feelings. The projection of these aspects, Klein feels, goes some way towards explaining E’s detachment from analysis, and his lack of emotion. When his ambition returns in a dream, along with his fear that this may ‘spread a fire’, Klein brings this into connection not only with his destructive ambition, but also with his loving feelings towards her. This may be a treasure that analysis could uncover, but it also something terrifying to E. Loving feelings connect strongly to anxieties about parental relations, Klein thinks. Analysis, which threatens to return such feelings to consciousness, poses a great threat to E’s psychic stability, which he sustains by recourse to splitting and projection. This brief yet richly suggestive vignette helps us think about what may drive resistance to treatment, and about the role of projection in possibly facilitating the development of healthier aspects of the personality.

#melanie klein#psychoanalysis#unconscious phantasy#wellcome library#projection#splitting#oedipus complex

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Better to let sleeping dogs lie…’ – An unconscious phantasy regarding a biting and dangerous internal object

16th July 2024

In my last blog I shared material from archive file KK/PLE/B.69, and I am returning once more to that file. B.69 contains notes about a patient, ‘H’, whom we learn is a zoologist, as well as an air raid warden during the war. Readers may recall that he presents with a worry about frequent urination, believing that it will harm his penis, which he has long felt to be inferior and damaged.

In her treatment of H, and in her thinking about this particular symptom, Klein clearly has in mind that urine is one of the bodily products available to the infant in the earliest period of life, which may be employed as a weapon against objects when sadistic impulses are in the ascendant. With its poisonous and burning qualities, urine could be used, for example, to paralyse or destroy the object, or to protect against attacks felt to be coming from objects. It could even, as her work with H suggests, be hijacked by an internal object and used against the subject.

Klein feels that, in focusing his fear on his penis and the problem of urination, H has localised deeper anxieties concerning what is going on inside him. There are conscious fears of ‘internal trouble’, including a dread of cancer, and a belief that such internal problems will last forever, or may even lead to death. Last time I showed Klein linking such fears to an unconscious phantasy of an angry, dangerous internal father who wreaks havoc both inside H and in his external life. It is clear from Klein’s notes that H’s father, who is deceased by this time, was an alcoholic, and a violent, troubled man, and it seems that H had long been estranged from him.

Klein suggests that her patient’s symptoms connect to a belief that his destructive internal father urinates through him. H’s sense of his father also interferes greatly in his sexual relations with his wife, with the effect that their intercourse is often interrupted. H has earlier remarked to Klein that when he feels anxious about his symptoms, he thinks it ‘better to let sleeping dogs lie’ than to explore the meaning of them. About this, Klein writes, ‘here is another aspect of his internal objects. They are felt to be biting and dangerous dogs.’ Though H remarks that he had no conscious fear of dogs in childhood, he remembers that he was always interested to see them muzzled, and was told that they had to be muzzled because of rabies.

On 28th March 1940, H brings a dream, which highlights another difficulty ensuing from his anxieties concerning his internal father; that is, his trouble in separating from his mother. In the dream,

‘He was setting out on a journey on his bicycle from his house, and felt he could not do it, especially because there was such a crowd of people there he would have to get through.’ [33/67]

Klein writes,

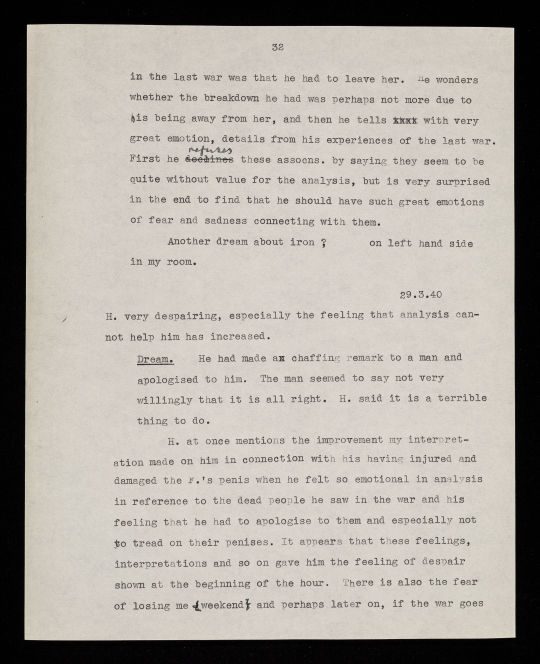

This dream is so typical of his whole life for his feelings of impotence…In this dream he set out from his mother’s house and feels that he could never really get away from her. The worst thing in the last war was that he had to leave her. He wonders whether the breakdown he had was perhaps not more due to his being away from her, and then he tells me with very great emotion, details from his experiences of the last war. First, he refuses these associations by saying they seem to be quite without value for the analysis, but is very surprised in the end to find that he should have such greater emotions of fear and sadness connecting with them. [33/67–34/67]

Shortly after this dream, on 2nd April 1940, H ‘spontaneously and unusually easily’ reports a change in his symptom. Klein writes,

‘He had been out the whole day and found no getting worse… he could pay so much more attention to work, without having continually to force himself. But that, he thinks, is the result of his not having to think all the time about his fears of urinating. He describes the terrible strain of holding a grip, which he shows with the gesture of his hand, and the necessity to urinate. Feels all the time that he would be lost if he was getting weaker and could not control it.’ [37/67]

Klein writes that H ‘feels himself burdened and exhausted by the continuous necessity to watch and control.’ She refers to:

‘…the drinking, urinating, dangerous father inside, whom he must continuously watch and control. If he relaxes (and that would apply to him being able to work easily and not having to keep rigid the flow of thoughts), then the father inside him would bring disaster over his mother inside him, as well as the whole world, through urinating through him.’ [36/67–37/67]

The material I shared last time showed that H was, as a child, terrified of leaving his mother, feeling that she would come to some terrible harm at the hands of her husband, H’s father. In this context, H’s ‘holding on’, or resisting the need to urinate, means preventing his father from doing harm. One can imagine the strain, as well as H’s reluctance to relinquish his symptom. Indeed, H is most unhappy that Klein is implying there is something wrong with controlling, ‘as if it implied something very dangerous for him to control’. Klein writes, ‘plaintively once or twice he said if he had not needed to control his urination he would be left without defence – weak.’ [38/67]

The following day, 3rd April 1940, Klein notes that, ‘H reported an awful getting worse of his symptom. As usual [he] puts it, ‘it had never been as bad as that’’ [38/67]. He fears ‘the absolute destruction of his penis’. While he feels hopeless about Klein being able to help him, H also expresses the view that,

‘when urination went on he felt like running to [me] and asking [me], ‘do help me’. He is helpless, despairing, not hostile. It is quite obvious that I still represent a good object to him.’ [39/67]

Klein returns to the theme of control. She refers to the ‘drunken, violent father inside… his dangerous and poisonous urine, the various dangers resulting from restraining him; the father’s temper and hostility if he was restrained; if he cannot put out his urine, as it were, into the external world, he will be all the wilder and more dangerous inside.’ She writes of H’s,

‘fear of retribution at the slightest complaints he might make, and points out how terrifying this retaliating and revenging wild father, whom he must control about the urination and ejaculation, would be.’ [39/67]

Taking this in the transference too, Klein says that she,

‘tries to get hold of his anxiety in relation to her when she interprets control; that he felt he had fallen out with me for reasons I could not quite understand enough, as if [I] had blamed him about controlling the object, and that would really refer in the past to mother who tries to protect father against his controlling… siding with the father against him, and in this way he loses the helpful mother to whom he turns against the dangerous couple.' [39/67–40/67]

In this brief excerpt from Klein’s work with H, we see her analysing the powerful influence of an unconscious phantasy on her patient’s internal and external life. Klein interprets H’s symptoms and anxieties in light of his experience of ongoing persecution by his internal father, whom he also believes poses a great threat to his mother. Klein’s interpretation seems to be borne out when it emerges that in addition to his concerns about his penis and urination, H feels so tied to his mother, whom he feels he must go on protecting long after his father has left, or even died. H’s breakdown, when he is separated from his mother during the war, seems to further evidence this.

Readers can learn more by visiting the Wellcome Collection's online catalogue, and searching for file KK/PLE/B.69.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patient H: An acute worry about urination

7th March 2024

I have resumed my explorations in the Melanie Klein archive this month after a short time away. My latest find comes from the B files, which contain Klein’s clinical notes on both adult and child patients. Here I'm sharing some excerpts from file B.69, which contains notes on a male patient, ‘H’, from 1940. The file is fairly large, running to some 67 pages, so I am picking out some particularly thought-provoking fragments here. If you want to read more of this material, you can do so at PP/KLE/B.69 on the Wellcome Library website.

The file opens with Klein describing patient H’s ‘acute worry about urination’, which is connected to fears he has about his penis. She writes,

‘…from an analysis many years ago, he knows much about castration fear, and has evidently stabilised himself in localising his fears in this way.’ [image 3/67]

Klein writes that H’s worry about his penis and about urination is connected to a fear of ‘internal trouble’ or disease, and of cancer specifically. She links these preoccupations to a concern that arose during H’s adolescence, related to his enthusiasm for collecting butterflies and insects: namely, a presentiment that the cabinets in which the creatures were displayed would become disarranged. Klein describes the rituals by which H tried to ensure the cabinets were not tampered with, and records that he could eventually no longer bear the strain of his anxieties and gave up collecting altogether.

She writes, ‘his fears about internal disaster…actually, the fears about the inside, the cabinets, and the penis, are alternating…,’ and also that his, ‘fear about the penis [is] obviously over-emphasised in order to keep away from these internal fears’. [image 4/67]

‘Abundant dream material’ follows from Klein’s connection of these things, and she records that,

‘the butterfly, a very much admired and loved object to begin with, in a dream changed into another insect with mutilated wings, much less good, and also much less attractive, and then into the insect which paralyses another insect.’ [image 4/67]

Klein’s notes show her interpreting H’s dream in light of his dread of homosexuality, which he feels ���would be somehow disastrous for his penis’. H associates to catching a butterfly with a white net, and Klein says this highlights H’s longing for a good penis, and that the net represents, ‘the mouth by which he took in the penis of the father, a good object, [which] changes instantly into a more and more dangerous one as soon as it is inside.’ In association, H recalls,

‘…feelings of being insincere towards his mother, who seemed to think that he was a paragon of virtue, beyond temptation, as it were, and he knew, when she said something of the kind…that he was interested in other boys’ penises. This interest was quite conscious. He took it that it was mainly to compare them with his own, which, in childhood he had felt to be inferior and damaged. He feels also that in his frequent urination the penis has shrunk, and he must see it and make sure that it is still there. That is one of his conscious feelings about the obsession to urinate.’ [image 5/67]

Feelings of insincerity follow, Klein writes, from H’s sense that he has robbed his mother of father’s good penis, represented by the butterfly he tries to catch.

H’s father, Klein notes, is a frightening figure felt to be violent and dangerous. Whilst H recalls feeling little warmth for his mother, he does bring a memory of clinging to her bedsheets when he was terrified of going to kindergarten. Klein notes that,

‘…he was so terrified that his only help was to stand there with closed eyes, which seem[ed] to relieve some anxiety, as if he would see something awful if he opened his eyes…he feels the terror was that he left his mother behind in danger.’ [image 6/67]

H also remembers,

‘…that when his parents had not come up from the evening meal by eight o’clock – which had been a ritual – then he started to yell, so that it could be heard all over the house. If they came up by eight then it seemed to be all right. We understood that some awful danger was to happen to them at night time, and that this was shifted on to this definite hour at which he knew that the parents were at a meal with the people there as well.’ [image 6/67]

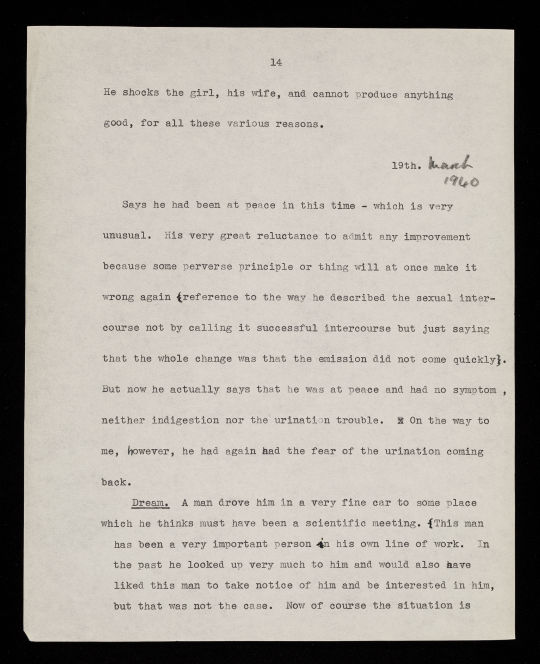

On 19th March 1940, H tells Klein that he feels peaceful. He is reluctant to admit any improvement, lest things go wrong again (Klein thinks that he is referring here to intercourse), but there are no symptoms to speak of, no indigestion or urination trouble. H then reports a dream, a fragment of which I will share here:

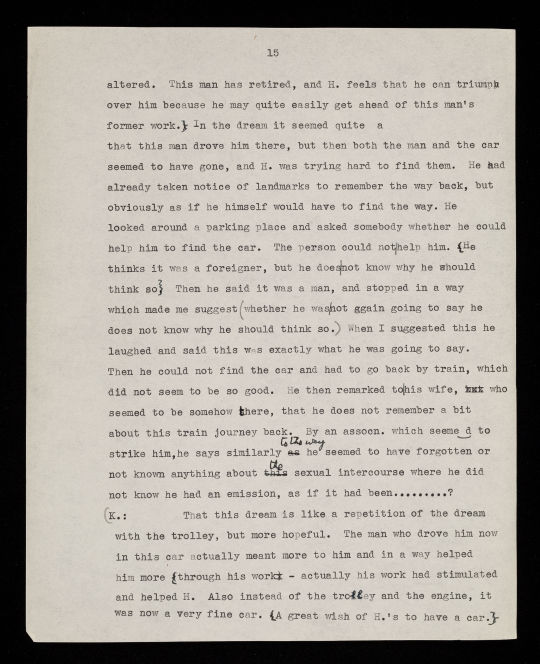

‘A man drove him in a very fine car to someplace which he thinks must have been a scientific meeting. (This man has been a very important person in his own line of work. In the past he looked up very much to him and would also have liked this man to take notice of him and be interested in him, but that was not the case. Now of course the situation is altered. This man has retired, and H feels that he can triumph over him because he may quite easily get ahead of this man’s former work.) In the dream it seemed quite a…[word missing] that this man drove him there, but then both the man and the car seem to have gone, and H was trying hard to find them. He had already taken notice of landmarks to remember the way back…as if he himself would have to find the way.’ [image 15–16/67]

Klein tells H that the man who drove him had clearly helped him, and meant something to him. He was important too, and has a very fine car. She notes H’s great wish to have a car of his own. The situation of being driven by an important man, Klein says, ‘points to the internalised father’, and she connects H’s admiration of this man’s work to his admiration of his own father, who built a harbour in a place where they spent summer holidays. She suggests,

‘…there may have been great admiration in [the] early days for the potent father, the father who owned mother, who made children, who had skill and power, etc. Great desire and longing to be on good terms with his father, to be taught by him, to be introduced into sexuality, to share with him mother. I suggest that the fine car stands for mother.’ [image 17/67]

Klein also writes that,

‘H was in the dream trying to undo the loss of the important and good father and the mother, wishing to have the two with him and united in a good way inside him. At the same time the wish to become independent of his internal figures, the landmarks he made because he was going to find the way himself…In this hour as well as in former ones, much work about the repression of his love and admiration for his father, actually there is only one friendly memory so far, when his father had him on his knee, and offered him a chestnut, which H very much liked, but could not accept it, and told his father he could not accept it because he had to find chestnuts for himself. He thinks his father was very angry.’ [image 18-19/67]

To learn more about Klein’s work with H, readers should go to PP/KLE/B.69, and start from image 19/67, where the notes reproduced here end. I will certainly be doing this, and in my next blog post may bring more about H, or perhaps another of the patients who appear in this fascinating file. I am struck that, in the brief excerpts I have shared, Klein is once more grappling with the way in which the patient’s conception of a parental couple powerfully influences both his sense of himself and his relations with others. She clearly feels it is part of her role to help H uncover the better memories of his parents, which she perceives in his material – though often deeply buried.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fear of influence – projective identification in love and work

20th September 2023

My last few blogs have focused on psychoanalytic technique. In them we saw Klein advising colleagues in relation to interpretation and the use of silence, and emphasising the need to be ‘self-critical enough’ and to ‘keep our minds and technique flexible.’ Here, I am changing tack slightly, and in the coming months intend to share a number of clinical vignettes, recorded by Klein, which she clearly felt threw light on various theoretical ideas.

The vignette I share here is from file B.98 of the archive, which is named ‘Theoretical Thoughts 1946’. As readers may know, Klein published her seminal paper on the paranoid-schizoid position in 1946, in which she discussed projective identification. This is the complex mechanism by which, in unconscious phantasy, parts of the self are located in the other for various reasons – such as to control or to harm – and with varying effects both on the self and the object. Klein clearly has this concept in mind as she explains the preoccupations of one her adult patients, ‘M’. Regarding this patient M, she writes:

...the influence the projective identifications have on sexual intercourse are seen quite clearly in somebody whose analysis has not been carried to any length yet.

M, Klein observes, is worried about ‘influencing and moulding’ the women with whom he becomes romantically involved. His specific concern is that he should influence them, ‘in such a way that they are greatly changed and become really like himself.’ Klein notes that M,

…saw with dismay that a girl he likes and who likes him had changed her style of dressing in the way in which he sometimes likes women to be dressed and he called this “the thin end of the wedge”.

Further, she records that,

He speaks with great concern about an earlier relation in which this [his influence] seemed to be one of the factors which made the girl too fond, too dependent on him… [The relationship] finished unsatisfactorily, because he cannot bear too great dependence in the woman.

Klein seems to have in mind here the way in which, in phantasy, M locates aspects of himself (such as his liking for women who dress in a particular way), in the women he is in relationships with. He then finds them changed as a result: more like him because they contain aspects of him. In M’s case, it appears that there is some continuing recognition of the split-off parts – hence his perturbation – although often, if the aim is to entirely disown such parts, one may feel absolutely disconnected from them in the other.

Another effect of projective identification in this case, is that M feels these women to be too dependent on him. One may surmise, however, that M himself felt very dependent on these women because they now contained parts of him. M seemed to respond to this experience by projecting his own feelings of dependency right back into these women.

Klein notes that M’s concern regarding his influence extends beyond romantic relationships, to professional ones. She writes,

Somebody said that he is apt to choose people (in working conditions) who are so receptive to his ideas that they will make a perfect staff. In referring to this influence he said: “They become really too much like myself and then I become very tired because I am not really so fond of myself and don’t want to see so much of myself about.”

Again, when one is projecting parts of oneself into others, one is apt to feel surrounded by these aspects – surrounded by oneself, as patient M observes. Klein notes that, in M’s case, it is relationships with women that are particularly affected, and that he ‘does not seem to feel having [sic] such powers over men.'

I think Klein was using this brief vignette to illustrate one particular impact of projective identification, namely the way in which a phantasy of having located parts of the self in the other can leave one feeling frighteningly powerful; worryingly capable of controlling or influencing the object. This is why M says that the girl dressing in a way that he would like, is just ‘the thin end of the wedge’; i.e., only the beginning. Another response might be that M feels quite trapped by these women into whom he projects. Perhaps this is also what he is getting at when he says that they become too fond of, or too dependent on him.

Klein ends her notes with a ‘Conclusion’ which, though it sounds very definitive, is to my mind more a postulation about what might be going on in M’s case. It’s not clear whether, or how, she put this to her patient, but it is interesting that she suggests M’s projection may lead him to feel rather less powerful, or potent, than he consciously fears himself to be. She notes the possible implications for sexual relations in this connection. She writes,

Conclusion: The penis being used as a controlling object, as an object to be split off, and then the mechanism of splitting is very active. Not only faeces are split off but parts of the body which are entering the body [of the other] and controlling it. Now the penis is then felt to remain inside in a controlling, guiding, et cetera way. That too must have a bearing on difficulties in potency, because if it is too much a sent out part of oneself it impedes the capacity…

The notes tail off at this point, with Klein highlighting the way in which the ego can become depleted by excessive projection. Her remark about the potential impact on sexual potency indicates that one may feel most concretely, the loss of a part of the body, such as the penis, following a projection. Readers interested in this aspect of Klein’s thinking can learn more in the Theory section of the Melanie Klein Trust website.

In April 2024, the British Psychoanalytical Society will host a conference in Edinburgh called ‘The Dynamics of Influence’. The aim of the conference is to provide a space to explore the ways in which analyst and patient can powerfully influence one another. The mechanism of projective identification, and the implications of its use, will likely be central to discussions.

#paranoid-schizoid position#psychoanalysis#melanie klein#projective identification#sexuality#dependency#1946#unconscious phantasy

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

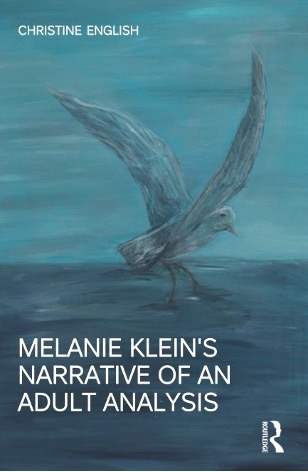

New publication: Melanie Klein’s Narrative of an Adult Analysis

5th June 2023

This month’s post is a bit different from usual, as I am delighted to announce the publication of my new book, the latest – and most substantial – product of my research in the Melanie Klein archive. Melanie Klein’s Narrative of an Adult Analysis brings to light Klein’s work with an adult patient, Mr B, which took place between the years 1934 and 1949. While Klein’s 1961 Narrative of a Child Analysis provided a detailed record of the psychoanalysis of a child patient, Richard, there hasn’t previously been a similarly full account of her work with an adult patient.

My new contribution to Klein scholarship builds on the valuable work that Elizabeth Spillius, Claudia Frank, John Steiner and Jane Milton, among others, have already done to illuminate Klein’s theories and clinical work. This record of Mr B’s analysis provides the reader with detailed clinical evidence in support of Klein’s ideas concerning the combined parental couple, phantasies about the inside of the maternal body, attacks on objects using bodily products as ‘weapons’, and the guilt that follows these attacks – which may go hand in hand with a terror of retribution by damaged objects.

Klein’s work with Mr B also reveals so much about the nature of the fundamental conflict between love and hate, which, as Klein saw it, is first experienced in connection with the breast. In this account of an analysis we can see the terrible implications where such a conflict is not well worked out in development. The book also reveals Klein’s great insights into what may drive a negative therapeutic reaction, and into the dynamics of, and obstacles to, mourning. There is very moving material on the impact of the unexpected arrival of a sibling, and the way in which love can become almost entirely obscured where hatred has instead been nurtured through grievance. Love, however, as Klein’s work with Mr B shows, may in turn be liberated through the rigorous analysis of aggressive impulses and hatred.

The following excerpt, from Chapter 2, gives a flavour of what readers can expect from the book. Here, Klein is describing a difficult but important period in Mr B’s analysis, which begins when he bumps into another patient of hers, a child. Klein writes:

Confidence in me had increased, though this easily changed one day to give place to full distrust and to accusations which we could easily connect with the attitude towards mother and nurse. I had been able to make an arrangement by which Mr B did not meet either the patient before him, or the patient after him. I made a special point not to alter his hour since the definite possession of this special hour meant very much to him, and seemed to be partly a compensation for the great frustration which, in repetition of the old situation, analysis brought to him. But [at some point] I had to alter this arrangement for a child patient who could not come earlier. To begin with Mr B seemed to take it reasonably, but he could not maintain this attitude. He became silent only to break out in accusations about how I had disappointed him and let him down. I had promised him this hour and he asked me to remember how strongly he had felt about this promise. When I pointed out to him that he could still have his hour, but that I could not then help his meeting the child, he seemed to take it fairly reasonably.

The next day he came a few minutes earlier, obviously in order to avoid meeting the child, and he waited in the waiting room until the child had gone. He heard me talk with the child in the hall, since I escorted this child to the door partly to make quite sure that he would leave the house, as he was very reluctant to do so. The child, who had meanwhile developed similar feelings towards the grown-up patient as Mr B had towards him, said before he left, pointing at Mr B’s hat which he saw in the hall, ‘oh, that man has arrived’, a remark which was heard by Mr B in the waiting room. Mr B again tried to take it reasonably and attempted a joke about the child, obviously disliking him, but he then became silent and a very critical part of his analysis began. Near the end of the hour, he broke the silence only to accuse me, full of hate and indignation, of having let him down and broken my promise to keep this particular hour for him. When I pointed out that I understood the difficulties which had arisen out of the presence of the other patient, but that I had actually not altered his hour, Mr B replied that I had actually kept him waiting. It is true [that this was] only for a very short while, actually one minute, but still this waiting occurred in his own hour. It appeared that the old situation, namely the unexpected arrival of the sister, had been reactivated with full strength, and Mr B recognized it himself… He even said that had I announced the child to him before he met him suddenly, it would not have made so much difference, because he would nevertheless have felt the deprivation quite as strongly. It [would] not [have] relieve[d] the feelings roused in him. Analysis had become absolutely bad. Everything that I had ever interpreted was wrong. Mr B felt hopeless and wanted to break off his analysis. When, after my interpretation of the whole situation something seemed to loosen, he said ‘you will not be able to do anything because my army is ready and I am fully on its side’.

Klein’s notes continue:

During the next few days Mr B came very late, nearly at the end of his hour, so that I could see him only for a few minutes. He had repudiated my suggestion to move his hour 10 minutes later so that he would not meet the child because, [he said,] that would mean that he had no more the same hour, [that the hour would be] no more his own. Still, he came every day, although during the day he always made up his mind not to come at all and to break off. But those few minutes we had and to which I was able to add another 10 minutes or so of extra time, gave me the possibility of analysing the situation. I may mention that Mr B felt very guilty for coming so late, for keeping me waiting and for losing so much of his time and accepting extra time, and he watched very anxiously my reaction to all this. He agreed with me that his coming so late was partly to show that he would not keep to time since I had not done so, at least this is how he felt, but I did not stress this point much. I showed him, both in my attitude and in my interpretations, that I quite understood that he could not help staying away since there was too much anxiety connected with the remote possibility of meeting the child, and that altogether he could not bear to be with me for the full time. It certainly relieved some anxiety that I said that we would just have to be patient and do at the moment as much work as we could. I had generally interpreted that the main thing was not his disappointment, but the anxiety aroused in connection with his aggression, [that arose] both against the child and against me. I substantiated this with a few remarks he had made. He had said that even if I happened to abolish this child it would not help now any more. In one of these short sessions, he had spoken of feeling like falling into a well with burning pitch and of disaster all around him. He had not lied down, or if so, had soon got up again and sat further away from me or was even standing. After an interpretation he had quoted a line of Coleridge, ‘if we fall out with those we love it works like poison on the brain.’ He had spoken of the kettle in him which would boil over and which he could not control. I could relate all this to former material in which his words and thoughts were equated to attacks with burning and poisoning, and I interpreted his anxiety of meeting the child on the grounds of his destructive wishes against this child and his anxiety of abolishing the child directly – as well as of the child being destroyed because of his secretive sadistic attacks against it.

Klein quotes this line from Coleridge (which is slightly misquoted by Mr B) in her 1937 paper, ‘Love, Guilt and Reparation’. There, she writes of the concern and guilt one may experience upon feeling hatred, at times, towards a loved one. I think she must have had Mr B in mind when she included this quotation. In the notes above Mr B rages at Klein, whose arrangements have provoked the re-emergence in him of very early, unbearable feelings of displacement and hatred. He now feels ‘on a razor’s edge’ with respect to the analysis, just as he had felt all his life in relation to his mother. Klein’s understanding clearly helps Mr B to cling on until the emotional storm is worked through.

The cover picture of the book was painted by Beccy Kean, and is called Stormy Petrel*. It was inspired by an extremely poignant moment in Mr B’s analysis: his painfully moving description of this tiny seabird which struggles so much to get to its young and Klein’s connecting of this to Mr B’s experience of his mother, whom he felt had struggled so much to feed and nurture him. It is remarkable to understand the ways in which Mr B’s relations with both parents are revised in the course of his analysis with Klein.

* In Klein’s notes, she writes ‘stormy petrel’, though the correct name of the bird is Storm Petrel. Mr B, who was so knowledgeable about the natural world, presumably knew this. We cannot know for certain which term he used. The term ‘stormy petrel’, however, was once used to denote ‘a person who brings or portends trouble’ (Collins English Dictionary), deriving apparently from a belief held by sailors that storm petrels foretold or caused bad weather at sea. One can imagine Mr B may also have used this term, which seems not unconnected with his experience of his mother.

**

Praise for the book:

'This is a formidable work on the source of Melanie Klein’s ideas that provides a fascinating picture of Klein as a clinician, and sheds light on many of the deepest questions raised by psychoanalysis. Aptly entitled Narrative of an Adult Analysis, this book may come to rival the Narrative of a Child Analysis as a means of understanding Klein’s work.' (John Steiner, Training and Supervising Analyst, British Psychoanalytical Society)

'Christine English has produced a book of tremendous interest and major importance. It is also gripping to read. This book is the first and for now the only account of Melanie Klein’s day-to-day psychoanalytic treatment of an adult patient, and it is enthralling.' (Priscilla Roth, Training and Supervising Analyst, British Psychoanalytical Society)

'Christine English has taken a hugely important step forward in Klein studies. Tapping a rich seam in the Klein archive, she shows in detail how Klein worked with an adult patient, Mr B. This rare and moving account of an adult analysis deserves to become as famous as Klein’s analysis of her child patient, Richard.' (Jane Milton, Training and Supervising Analyst, British Psychoanalytical Society)

#melanie klein#psychoanalysis#routledge#mourning#unconscious phantasy#psychotherapy#anxiety#reparation

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

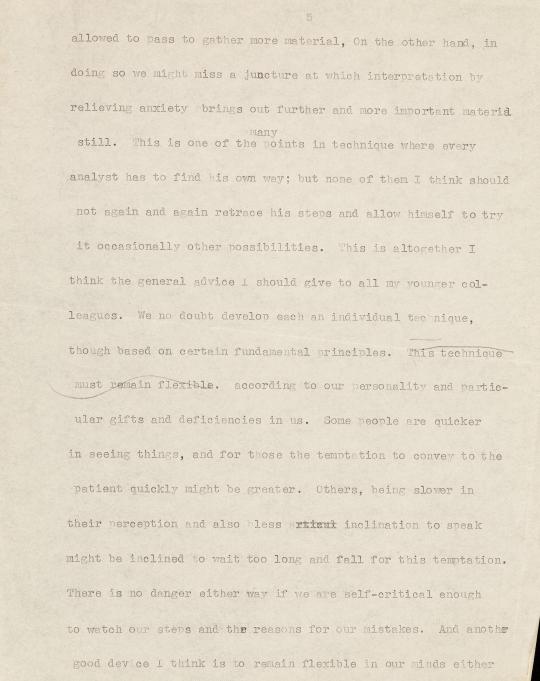

‘Every analyst has to find his own way’: further notes on technique

13th March 2023

This is the third in a series of blog posts addressing the subject of technique. In my previous two posts I shared material from file D.3 of the archive, called ‘Notes on interpretation, notes on defences’. Here, I share another handful of illuminating fragments from the same file. Again, Klein speaks about interpretation, the patient’s resistance or reaction to it, and of the ‘synthesising’ action of analytic work.

This wasn’t a term I was familiar with from Klein’s writing, nor one which is in regular usage these days, as far as I know. However, it does appear in a number of Klein’s later papers, including in ‘Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms’ (1946), and ‘On the Theory of Anxiety and Guilt’ (1948). In this latter paper Klein writes that, ‘the basis of depressive anxiety is the synthesis between destructive impulses and feelings of love towards one object’ (p.35). Klein gives an example of synthesis in the notes I reproduce below, and I have also included an excerpt from her work with Richard, from her 1961 Narrative of a Child Analysis, which illustrates it well.

Firstly though, returning to the matter of finding the right balance between interpreting and allowing material to flow, Klein writes that it takes,

…much experience and constant vigilance even later on not to err in this respect. We have to ask ourselves over and over again whether now is the right moment for interpretation, [or] whether what we have seen now as an important point should not be allowed to pass to gather more material. On the other hand, in doing so we might miss a juncture at which interpretation, by relieving anxiety, brings out further and more important material still. This is one of the many points in technique where every analyst has to find his own way; but none of them I think should not again and again retrace his steps and allow himself to try occasionally other possibilities. (PP/KLE/D.3; Image 5-7/85)

Demonstrating just this sort of vigilance in her own work, Klein reflects upon receiving criticism from colleagues. Somewhat amusingly, she insists that she has seriously considered this criticism, while simultaneously making it clear she feels it was wrong:

I have often made good use of criticism which, though it had missed the mark, made me try over and over again [to think about] whether certain things I was criticised for could not contain some truth. (Image 9/85)

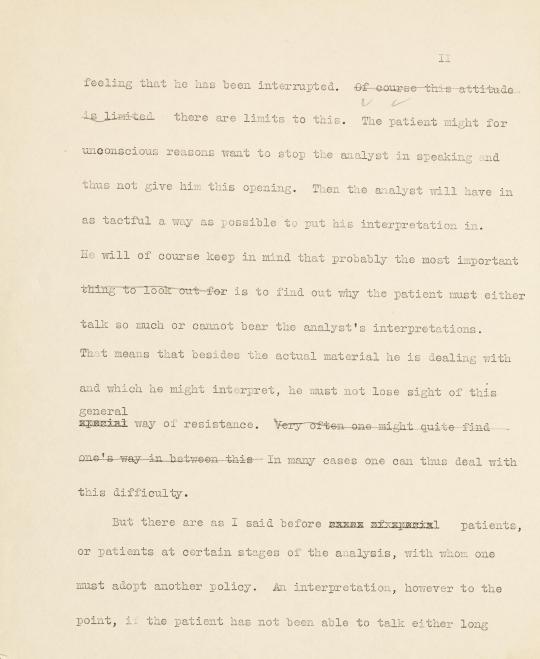

Then, regarding the patient’s resistance to interpretation, she writes:

The patient might for unconscious reasons want to stop the analyst in speaking and thus not give him [an] opening [to interpret]… [In this case,] probably the most important thing is to find out why the patient must either talk so much or cannot bear the analyst’s interpretations. That means that besides the actual material he is dealing with and which he might interpret, [the analyst] must not lose sight of this general way of resistance. (Image 43/85)

Klein highlights one possible reason why a patient may experience an interpretation as an attack. She says that, on occasion,

…the content of the material presented is of such a nature that instant and dangerous punishment is awaited. The first feeling when the analyst opens his mouth is that now the scolding or the pronouncement of the judgement has come. (Image 46/85)

Klein turns next to ‘synthesis’, and she uses a vignette to illustrate this:

Synthesis is equated to bringing to life or fighting deadness. But the way it is done by interpretation is sometimes to collect parts of the personality which seem not to be there anymore and which we guess from this bit, and that bit…

Instance: the dream where the dreamer urgently wanted to see what was at the moment her best object [friend]. She [the friend] had a party and did not want to see the dreamer. And everything depended on her [the dreamer] being able at least for a little while to see that person before she undertook some essential thing which all amounted to trying to find herself again. The good object (the person giving the party) stood for one part of herself and she was desperately trying to bring herself together. If she could not find that part, she could not achieve her objective. [My] interpretation was that this [friend] was herself and this was the part [of her] she was struggling to find. Yet she was saying in the analysis that nothing of her was there, that nothing had any meaning, that interpretations had no meaning. But the particular person she chose as the best part of herself had all the qualities which she felt would help her both to re-integrate herself and a good relation with me. That person was not over ambitious, did her job well, was exactly the part of herself which she should find. (Image 49/85)

Further connecting the synthesising function of interpretation to the life instinct, Klein comments:

The analyst’s work in synthesising implies that in the struggle between [the] life and death instincts, which underlies all mental processes, he strengthens the life instinct, the expression of which is synthesis. Insofar as analytic procedure strengthens the derivatives, namely, libido, love and hope, it serves the purposes of the life instinct in its polarity with the death instinct. (Image 83/85)

In her 1961 Narrative of a Child Analysis, Klein discusses synthesis in relation to her child patient Richard. She writes:

It is an essential part of psychoanalytic therapy…that the patient should be enabled by the analyst’s interpretations to integrate the split-off and contrasting aspects of his self; this implies also the synthesis of the split-off aspects of other people and of situations. Such progress in synthesis and integration during an analysis, while giving relief, also brings up anxiety. For the patient is bound to experience the persecutory and depressive anxieties, which were largely responsible for the tendency to split, splitting being one of the fundamental defences against persecutory and depressive anxiety. (p.77)

Klein gives an example from Richard’s ninth session, illustrating her use of interpretation to help him integrate aspects of his mother. She records that,

Richard chose a country on the map to speak about; this time Germany. He said he wanted to whack Hitler and to attack Germany. Then he decided to ‘choose’ France instead. He spoke about France, which betrayed Britain but might not have been able to help it, and he was sorry for France.

Mrs K. pointed out that there were various kinds of Mummy in his mind: the bad Mummy, Germany, whom he wanted to attack in order to destroy Hitler inside her; the injured, and not-so-good Mummy whom he still loved, represented by France; when they came together in his mind, he could not bear to attack Germany, and rather turned to France for whom he could allow himself to feel sorry. (p.49)

Interpretation, which so often aims at the integration or synthesis of objects or the self, may produce guilt and depressive anxiety, Klein remarks in her notes to this session (ibid.). Indeed, she records that Richard soon begins to pick up books, ‘but without interest and seems lost in thought’ (ibid.)

-------------------

References:

Klein, M (1961) Narrative of a Child Analysis: The conduct of the psycho-analysis of children as seen in the treatment of a ten-year-old boy. Vintage.

Klein, M (1946) ‘Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms’. In Envy and Gratitude and other works 1946-1963 (1975/1997). Vintage.

Klein, M (1948) ‘On the Theory of Anxiety and Guilt’. In Envy and Gratitude and other works 1946-1963 (1975/1997). Vintage.

#melanie klein#psychoanalysis#interpretation#child analysis#death instinct#anxiety#guilt#integration

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

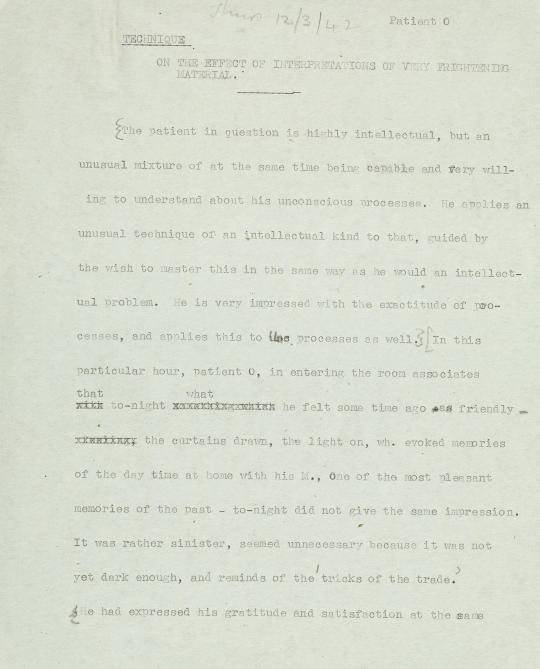

Klein at work: The interpretation of very frightening material

8th December 2022

In my last blog post I shared some of Klein’s notes on technique, and on interpretation specifically. These notes did not feature in her Lectures on Technique (Steiner, 2017), but I suggest that they are an interesting accompaniment to them. In the material that I have unearthed here, Klein talks further about interpretation - and we see her at work. One begins to form a vivid picture of her technical approach, and her way of being with her patients.

The following notes come from file PP/KLE/D.3 of the archive, which is titled, ‘Notes on Interpretation, notes on defence’. First, I share a short clinical vignette, which is typed, with added handwriting dating it to 12th March 1942. Klein has headed this vignette, ‘On the effect of interpretations of very frightening material’. She writes:

A woman patient who was in great stress of very deep anxieties in [which] her inside was felt to be like a sewer (her expression); everything deteriorated, in bits, mixed up with each other. In this particular hour the patient had expressed her feelings of dislike of herself – of disgust. The analysis was horrid, confusing, hostile. (PP/KLE/D.3; Image 15/85)

Klein often wrote about herself in the third person - frequently using 'K' as an abbreviation - and she does so here (the following passage appears within parentheses):

Klein’s interpretation was that the patient experienced Klein as if she were the processes going on inside her [the patient], even the bits of faeces, which she felt were mixed up with her bits [presumably the patient’s internal objects and processes]; and that the confusion in her mind which came from analysis was the confusion she herself experienced in her inner world. (Image 15/85)

The interpretation clearly brings relief, and the patient responds by saying, ‘Well, why didn’t you say so to me earlier?’ One imagines that further “groundwork” must have been done to enable the patient to accept such an interpretation. Nonetheless, Klein notes that,

The next part of the hour consisted in clearing up, of understanding and of a positive transference.

The following, longer clinical excerpt, comes from a session with a male patient whom Klein calls ‘O’. This material is also headed, ‘On the effect of interpretations of very frightening material’, and also dated ‘12/3/42’. Klein writes:

The patient in question is highly intellectual, but an unusual mixture of at the same time being capable and very willing to understand about his unconscious processes. He applies an unusual technique of an intellectual kind to that, guided by the wish to master this in the same way as he would an intellectual problem.

… In this particular hour, patient O, in entering the room, associates that tonight, what he felt some time ago as friendly – the curtains drawn, the light on, which evoked memories of the day time at home with his mother, one of the most pleasant memories of the past, tonight did not given the same impression. It was rather sinister, [and] seemed unnecessary because it was not yet dark enough… [It] reminds [O] of ‘the tricks of the trade’. He had expressed his gratitude and satisfaction at the same situation on other occasions. That is why he feels that doing this is to win him over, or to make him friendly after some rather frightening material in the last few hours. (Images 17/ and 19/85)

Again referring to herself in the third person, Klein writes:

(K. reminds him of what he himself has described as the enemy within. That applied to inefficient people in the conduct of our affairs, in contrast to the external enemy whom we have to fight.)

Now he himself caught on this expression ‘enemy within’ and came back to it later. He said that reminds [him]…of Klein’s interpretations of the ‘black sausage’ – an association which he had connected with a man whom he disliked in connection with a woman who he is fond of; and he said that he is dark and unlikeable in his mind. One of the next associations had been to the black sausage.

Now this and other material of internalised persecutors had come up in connection with his drawing Klein’s attention to the remark of the internal enemy. This was the material preceding this hour which started with the sinister impression of Klein’s room and the ‘tricks of the trade’ – expressing the distrust of Klein and her interpretations. It is important that he is constantly thinking of giving up the analysis, for which he had not very urgent motives, because his symptoms are consciously not of a very disturbing kind. He came for a particular reason, but since discovered that his relationships are not what they should be, that his relation to men is not at its best, and makes complications for him.

The fact that there was much unhappiness underneath and that he has dealt with it by getting away from love, or rather distributing it to a number of people, avoiding every tie and arranging his life accordingly: all this has become understood by him, but going with his very great fear of being tied in analysis there is a constant wish to give it up, at the same time preventing him from doing so for rational and irrational reasons.

(After his remarks about the sinister impression, Klein interprets that the last material was concerned with internal persecutors, his internal fears, and that now Klein’s room seemed probably full of the same things; and also that the internal enemies and processes which Klein interpreted to him, when they are experienced by him are transferred on to her – she becomes the representative of them.)

A moment after this, O turned round, looking into Klein’s face, and said with a voice more warm and friendly than she had ever heard in him: ‘I really hope that you do not believe that my remarks about tricks of the trade are of great importance. They are just fleeting associations. I really am very grateful to you for what you are doing for me, and I want you to know that’. After lying back again, O says that he thought Klein would probably be interested why he sat up; but he did feel that he wanted to look into her face and to tell her the affectionate feeling which he just had at that moment.

(K. interpreted the fact that giving him an interpretation referring to the aspect of K in which she was mixed up with his internal affairs and so on, made it possible for him to compare these feelings and aspects of her with ones nearer to reality, and allowed the friendly feelings to come up.) (Images 19/, 20/ and 22/55)

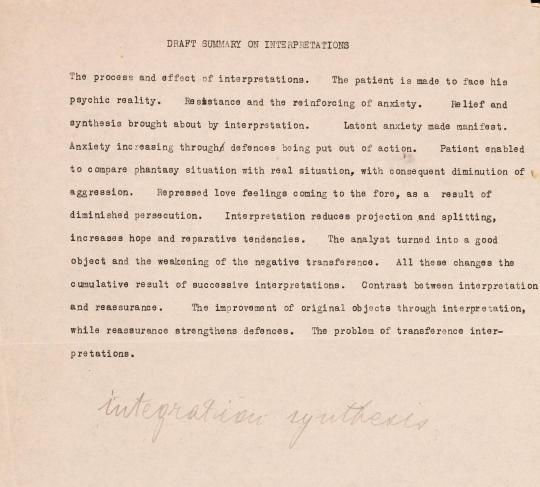

In a page entitled, ‘Draft summary on interpretations’ (image 50/85), Klein reflects that it is through interpretation that the patient is helped to ‘face his psychic reality’, and to compare this to external experiences which can become so coloured and distorted by phantasy.

Just this sort of process occurs when patient O experiences the drawn curtains and warm light of Klein’s consulting room as a trick, or an attempt to win him over following a difficult period in the analysis. O is helped by Klein to see that her consulting room becomes, in his experience, full of the internal persecutors they have been discussing. One result of this interpretive work is a very clear liberation of affectionate feelings. Klein writes:

[The] patient [is] enabled to compare phantasy situation with real situation, with consequent diminution of aggression. Repressed love feelings coming to the fore, as a result of diminished persecution. Interpretation reduces projection and splitting, increases hope and reparative tendencies. The analyst [is] turned into a good object and the[re is a] weakening of the negative transference.

---------------------

References:

Steiner, J (2017) Lectures on Technique by Melanie Klein. Routledge.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On interpretation

19th October 2022

Melanie Klein delivered her Lectures on Technique (edited with a critical review by John Steiner in 2017) to Candidates of the British Psychoanalytical Society for the first time in 1936. In these lectures, Klein directly addressed the subject of interpretation, alongside the ‘analytic attitude’, transference and countertransference, phantasy and grievance.

At the time she began the lecture series, there had been quite a sea change in analytic technique, following Klein’s work on early anxiety situations and the defences against them. Psychoanalysts, she thought, were increasingly approaching anxiety more directly, regarding it as necessary to ‘liberate small quantities’ of anxiety in order to prevent a ‘dangerous accumulation’ of it (Klein, in Steiner, p.57). Interpretation, of course, was the analyst’s main means of achieving this.

Klein agreed with Strachey (1934), that an interpretation could be felt by both patient and analyst as a ‘magic weapon’ (Steiner, 2017, p.54). However, her Lectures suggest that she felt more that interpretations were ‘feelers towards the unconscious’, a ‘means of exploring… unconscious phantasy’ (Ibid, p.23), and hypotheses for the patient to consider, rather than ‘a way of providing knowledge or insight from on high’ (Ibid, p.14). Klein’s Lectures, Steiner remarks, ‘come across as entirely modern’ (p.1), and there is no doubt that her inclusion of vivid clinical material, to illustrate the impact of interpretation, makes them especially engaging.

Recently I have been exploring file PP/KLE/D.3 of the archive, which is entitled, ‘Notes on interpretation, notes on defences’. Here, Klein makes a number of other points about interpretation, which are interesting to consider alongside her Lectures on Technique. She addresses, for example, the importance for the analyst of being ‘self-critical enough’ to pace and judge the impact of their interventions, and also underlines the value of remaining silent on occasion, even for long periods - and even when the patient demands it.

In an early part of file D.3, Klein writes,

It seems to me a central problem for psychoanalysts… to decide the right balance between interpretation and allowing the patient’s associations and material free and uninterrupted flow. (PP/KLE/D.3; Image 5/85)

We no doubt develop each an individual technique, though based on certain fundamental principles, according to our personality and [the] particular gifts and deficiencies in us. Some people are quicker in seeing things, and for them the temptation to convey to the patient quickly might be greater. Others, being slower in their perception, and also less inclined to speak, might be inclined to wait too long and fall for this temptation. There is no danger either way if we are self-critical enough to watch our steps and the reasons for our mistakes. (Image 7/85)

On the matter of the analyst, on occasion, restricting his ‘talk and interpretations’, Klein emphasises the need to ‘silently co-operate’ with the patient, and to take into account the patient’s history. With reference to a child patient, she recalls,

I have tried not to interpret at the beginning of an analysis [and] I [shall] give one instance of the kind. [In the case of a] boy who didn’t speak for so long, [I] refrain[ed] from interpreting for some weeks in order to gain the confidence of the child through more or less silent cooperation. This child had a father who had overwhelmed him with speech and constant interference, and the silence of the child was in some way connected with this attitude of the father. This attempt was instructive because, when I did take up interpretations, the difference it made in the progress of this analysis was all the more striking. (Image 9/85)

Klein emphasises, as she had in her earlier Lectures, that,

…we must keep our minds and technique flexible. There are cases, and this child was one of them, in which we might have very much to restrict our talk and interpretations, and miss interpretations rather than stir too much anxiety. (Image 9/85)

Later on, Klein stresses that the patient should always feel he has enough ‘free rope’ to talk. However, even in the case of silent patients, she suggests that plenty of room should be left by the analyst, though it may be tempting to say more:

[...] even silent patients sometimes cannot bear at certain stages of the analysis the analyst’s talking. There is nothing easier than to overdo one or the other attitude. I found that with great care and patience, one can arrive at a compromise in these cases, and that having given the patient free reign for the largest part of the hour or complied with his necessity to remain silent for a time, I could bring in some interpretations at some junctures, or at the end of the hour. (Image 11/85)

Finally, Klein gives the example of another young patient who literally restricts the amount of words Klein can use in an interpretation. Klein shows that her compliance with the patient’s demands enables the analytic work to go on until such time as the patient can tolerate her more usual way of making interpretations:

An extreme case was a boy with strong psychotic and delinquent features and liable to great violence, with whom I could at some stages of the analysis only interpret when he gave me formal permission for it. At hours of great anxiety it happened that the only interpretation could be given when he was already going out of the door from the hall. A few times he restricted me to giving the interpretation in 10 words, and it was not a small feat to put the most important interpretation into these 10 words. But I did not find even in this extreme case that I had to stick to this method. As soon as anxiety had diminished I could interpret more again, and strikingly enough even the 10 word interpretations couched in the most important words only, had repeatedly the effect of diminishing anxiety as well as the fact that I had submitted to this condition, I proceeded to more normal ways of interpretation. (Images 11/ and 13/85)

----------

References:

Steiner, J (2017) Lectures on Technique by Melanie Klein. Routledge.

Strachey, J (1934) ‘The Nature of the Therapeutic Action of Psycho-Analysis’. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 15:127-159.

#psychoanalysis#child psychoanalysis#melanie klein#psychotherapy#unconscious phantasy#anxiety#psychosis#unconscious

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the prophylactic value of play

17th May 2022

In my last blog post I shared some of Melanie Klein’s notes on friendship, found in file PP/KLE/C.9 of the archive. The material I’ve unearthed this time comes from the same file, but here we see Klein reflecting on the importance of play in the early relationship between the mother and her infant/child, and that between the infant/child and other important individuals in his or her life, including siblings. Klein’s focus here is the impact of the child’s experience of play on their development and overall happiness, and she draws on her work with an adult patient to highlight the suffering that may follow when a mother doesn’t play with her child.

We can see Klein reflecting carefully upon the subtle interplay of external and internal or constitutional factors, which has such a bearing on the infant and, later, child’s subjective experience of the world, environment, and other people. She takes into account, for example, the infant’s ‘responsive attitude’, as well as the capacity of the mother or others to really engage with the infant, for instance by getting down and playing ‘on the nursery floor’. She also points to the mitigating function of happy play, which helps an individual to bear conflict and worry, and lessens the sense of a gap between the generations.

As with many of her notes, those reproduced here are typed up, though clearly still in the process of being thought through and developed, with handwritten annotations, corrections and sometimes lines drawn through words and passages.

The first play therapy – a prophylactic one – starts with the mother’s playing with her child. The baby early responds to a playful attitude on the part of the people around him, and much is gained by this responsive attitude of the baby. Play between mother and baby contributes greatly to their happy relation. Furthermore, the playing together of children in the home, and next, with other playmates in the kindergarten – all the settings in which children play together or grown-ups play with children – are of great prophylactic value.

In the psycho-analysis of grown-ups one can see how these memories of happy play with mother or brothers and sisters or friends make up for much worry and conflict of different kinds, and produce a very strong tie between members of the same family. A home where there is no play in common remains cold, and there will be a wide gap between the child and his parents.