Photo

Stephenie Meyer | Twilight

Alice Notley | Alma, or The Dead Women

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This is also the message of classic horror: if the monster learns appropriate restraint, it becomes an angel.”

— Kirk J. Schneider, Horror and the Holy: Wisdom-Teachings of the Monster Tale. (via letterful)

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the wake of the modern decoupling of monstrosity from appearance, the monster can be anyone and anywhere, and we only know it when it springs upon us or emerges from within us.”

— Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Invisible Monsters: Vision, Horror, and Contemporary Culture

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

“what makes a human monster a monster is not just its exceptionality relative to the species form; it is the disturbance it brings to juridicial regularities… the human monster combines the impossible and the forbidden.”

— foucault

400 notes

·

View notes

Photo

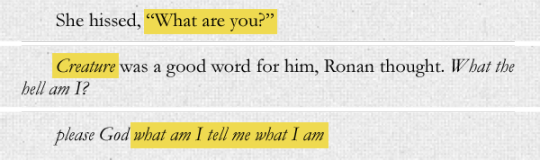

Ronan Lynch + Creature

Ronan Lynch + Dog | Ronan Lynch + Snake

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Monsters and Self-Acceptance in YA Lit: The Dream Thieves

The word monster “derives from the Latin monstrum, which is related to the verbs monstrare (‘show’ or ‘reveal’) and monere (‘warn’ or ‘portend’) [1].” Monsters have been a staple of our stories for hundreds of years. What do monsters, specifically in stories for young adults, warn us against?

The Dream Thieves, a 2012 YA novel by Maggie Stiefvater, explores how monsters in literature can meaningfully characterize self-loathing and illuminates the path to overcoming it. The Dream Thieves is the second novel in a young adult fantasy series that follows a group of friends on their quest to find and obtain a wish from a mythical king said to be sleeping in the hills of western Virginia. In the second book, the friends learn that one of them, Ronan, has the ability to take things from his dreams; however, Ronan has little control over this ability and frequently brings monsters out of his nightmares. These monsters, I will argue, represent Ronan’s self-hatred and the journey he takes to tame these monsters is a meaningful tale of self-acceptance.

In the first scene involving these monsters, we see one of Ronan’s dreams quickly turn into a nightmare. "Ronan could hear the night horrors coming, in love with his blood and his sadness. Their wings flapped in time with his heartbeat... Ronan was afraid of [them] in a ... permanent way that came from being killed by them again and again in his head.” When he accidentally brings two of the monsters out of his nightmare, he has to explain to his friends that “they come when I’m having a nightmare... They hate me. In the dreams, they’re called night horrors.’” Since the night horrors Ronan dreams of loath him, when he brings these monsters out of his dreams, he is essentially creating a physical manifestation of the hatred he feels towards himself.

We do not immediately learn why Ronan is filled with so much resentment towards himself. The prologue, however, reveals that “Ronan Lynch lived with every sort of secret.” His first is that he has the ability to take things from his dreams, but we also learn that he has a “harder kind of secret. One you keep from yourself.” Both secrets are intertwined with Ronan’s monstrosity and his self-hatred.

The first secret about his magical ability makes Ronan view himself as a monster:

“It was not the easiest thing to take only one thing from a dream… To bring any of the things from his nightmares — no one but Ronan knew the terrors that lived in his mind. Plagues and devils, conquerors and beasts. Ronan had no secret more dangerous than this… He remembered what Gansey had said: You incredible creature! Creature was a good word for him, Ronan thought. What the hell am I?”

He remembers the words his closest friend told him when Ronan showed him something he dreamed for the first time: “You incredible creature!” Later, in church, “Ronan closed his eyes to be blessed” and silently prays, “please God what am I tell me what I am." Ronan’s strange ability allows him to take monsters from his nightmares, but it also causes leads him to view himself as a monster or creature. This ability also makes him constantly wonder what exactly he is. Later in the novel, a character looks at Ronan and plainly says “I know what you are.”

This character is Joseph Kavinsky, a classmate of Ronan and his friends and an antagonistic force in their lives. At the beginning of the book, Kavinsky, as he is called, is mainly known for his wild parties and fast cars, and frequently street-races Ronan. After one of these races, the night horror that escaped from Ronan’s dreams in the first scene attacks him. Kavinsky drives up and shoots the night horror dead. As they are driving away from the scene, Kavinsky tells Ronan, “I know what you are,” and subsequently reveals that he, too, can take things out of his dreams, that the very car they are riding away in was dreamed up by him. Suddenly, Ronan is not alone. He still does not have a word for what he is, the “creature” that he is still does not have a name, but Ronan is no longer the only one. In fact, one of the first questions Ronan asks Kavinsky is “are there others?” However, Kavinsky just replies, “hell if I know.” Despite his strong dislike of Kavinsky, Ronan is relieved. He is also disturbed that his secret – something only his friends know – is out. “Ronan’s heart twitched convulsively. It couldn’t seem to get used to this secret being the opposite of one.” But as we know from the prologue, this secret is Ronan’s only secret.

We do not learn for sure what this concealed secret is until almost the end of the novel. After Kavinsky teaches Ronan how to take things from his dreams more deliberately, Ronan goes back to his friends. In a tense exchange as Ronan is leaving, Kavinsky says, “you don’t fucking need him” meaning Ronan’s best friend, Gansey. To this, Ronan responds “Wait. You thought- it was never gonna be you and me. Is that what you thought?” This interaction marks the end of friendly relations between the two dreamers and leads us closer to discovering Ronan’s second secret.

During the climax of the book, Ronan and Kavinsky meet in the dreamspace where they both take things from. Ronan asks Kavinsky “What’s here, K? Nothing! No one!” to which Kavinsky replies “Just us.” Ronan contemplates Kavinsky’s response: “There was a heavy understanding in that statement, amplified by the dream. I know what you are, Kavinsky had said.” This contemplation leads to the Ronan admitting his second secret:

‘That’s not enough,’ Ronan replied.

‘Don’t say Gansey, man. Do not say it. He is never going to be with you. And don’t tell me you don’t swing that way, man. I’m in your head.’

‘That’s not what Gansey is to me,’ Ronan said.

‘You didn’t say you don’t swing that way.’

Ronan was silent. Thunder growled under his feet. ‘No, I didn’t.’”

Up until this point, Ronan has not said aloud - or even thought about - the second secret mentioned in the prologue, but in this climactic scene of the novel, Ronan replies with, “no, I didn’t.” We now see that the secret Ronan kept from himself is about his sexuality. This revelation sheds light on why Ronan’s mind was filled with monsters that hated him, and casts light on another reason why he also viewed himself as a monster.

The author, Maggie Stiefvater, has said that the most important part of writing her stories is “getting into the reader’s head and moving the emotional furniture around.” As book reviewer Lee Mandelo notes, in regards to Ronan’s “sexuality, his secrets from others and himself, his attraction to Adam and Kavinsky in equal and terrifying measures” Stiefvater is “‘moving the emotional furniture around’ while the reader isn’t looking.” While we haven’t seen Ronan contemplating his sexuality in any part of the book, we realize that the parts we have seen (Ronan’s shame, self-hatred, and fear of his secrets being revealed) all tie into his sexuality as well. Ronan remembers Kavinsky’s earlier statement, “I know what you are,” but where before it meant that Kavinsky knew Ronan was a dreamer, here it means he knows he is gay. Stiefvater continues this emotional work after we realize the reason for Ronan’s self-loathing.

After Ronan’s “no, I didn’t,” Kavinsky, spurned by Ronan, takes a monster of his own from the dreamspace. Ronan knows that the monster, now in reality, poses a great threat to his friends in the waking world. Ronan needs to dream up something to combat Kavinsky’s monster; Then a night horror appears. Since these monsters “never want anyone else,” Ronan laments, “this won’t save anyone.” A friend in the dreamspace tells Ronan, “‘It’s only you. Why do you hate you?’” The statement “it’s only you” cements the supposition that Ronan’s night horrors are an extension of himself, particularly the part of himself that loathes what he is (both a dreamer, and gay, as we now know). However, Ronan considers what his friend says and in response to “why do you hate you?” concludes, “I don’t.” When Ronan wakes up he brings the night horror with him, but this time the monster does not set out to kill him. It saves his friends from Kavinsky’s monster. “The fire dragon pitched towards Gansey and Blue. Ronan didn’t have to shout to his night horror. It knew what Ronan wanted. It wanted exactly what Ronan wanted. Save them.” The night horror had always “wanted exactly what Ronan wanted,” but it is only after Ronan realizes that he does not hate himself anymore, that the night horrors do not wish him harm.

The other dreamer, Kavinsky, does not get the self-acceptance arc that Ronan does. Ronan’s journey of self-acceptance quite literally saves his life when he tames the dream monsters that represented his self-hatred. The opposite happens with Kavinsky. Kavinsky shares both parts of Ronan’s identity that gave him so much shame and self-hatred: a gay teenage boy, who is also a dreamer. Kavinsky does not have a “I don’t” moment regarding his self-hatred, and while Ronan’s monster learn to obey him, Kavinsky’s monster (and perhaps his self-hatred) destroys him. As the two dream monsters combat, Ronan notices that Kavinsky is standing purposefully in the path of destruction. Ronan shouts to Kavinsky to get down, but “Kavinsky didn’t look away from the two creatures. He said, ‘The world’s a nightmare.’ A second later, the fire dragon exploded into him. It went straight through him, around him, flame around an object. Kavinsky fell. He crumpled to his knees and then slumped gracelessly off the car.” Ronan remarks that “Kavinsky was dead. But he had been dying since Ronan met him. They both had been.” Both characters started off in the same place: depressed, amazed yet terrified at their ability to bring things from their dreams, coping with alcohol and street racing, mired in self-hatred and internalized homophobia, but only one of the characters makes it out.

The opposite endings Ronan and Kavinsky receive show the dangers of not accepting yourself and warn us of the self-hatred that often comes with having a marginalized identity. This story is steeped in a magic: there’s dreamworlds and kings and nightmare monsters, but it is a story completely applicable to real life. Ronan also starts off wondering “what am I?” and worrying that the answer is a “creature.” This parallels how certain identities can make one a monster in the eyes of society. Thankfully, Ronan realizes that he is not a monster for either secret or for either piece of his identity.

When I read The Dream Thieves for the first time years ago, I was somewhere between my own “no, I didn’t” realization, but before my “I don’t” moment. I was so moved by Ronan’s story. After watching Ronan progress through The Dream Thieves, burdened by the secrets he will not admit and terrorized by the monsters of his own creation, we can rejoice when he tames his monsters, accepts himself, and realizes he does not deserve his hatred. I can only hope that young readers will look at how undeserving Ronan is of his self-loathing and how he unlearns it, and undertake that same journey themselves.

This story lays a roadmap for young readers to forgo the self-loathing they may feel at certain aspects of themselves. Reader can to find love and adoration for characters who have yet to find love for themselves, and in watching these characters find ways to accept shunned and monstrous parts of themselves, they can be encouraged to embark on their own journeys of banishing self-hared.

Perhaps this is why there are so many memorable stories of monsters being transformed by love and self-acceptance, such as the recent The Shape of Water and the enduring Beauty and the Beast. Regarding this last story, psychologist John Gressel P.h.D., says the story encourages us to “find the beauty in the beasts in our lives.” He tells readers to

“Think of some part of you or your life that you don't like, can't accept, wish were otherwise… some aspect of yourself or your circumstances that has you feeling trapped, that you hate, that you want to go away or to escape from. According to this tale… you must learn to love this very thing you currently hate... Until you do, you are trapped in this prison cell of not accepting yourself or your life as it is. It is only through this kind of self acceptance, genuine and complete, that… we can unite with this previously unacceptable feature of our lives and live happily ever after. This is when that which we despise is transformed into something beautiful.”

In Beauty and the Beast, the Beast is literally transformed by earning Belle’s true love. As Gressel points out, Beauty and the Beast – and I would argue Twilight and The Dream Thieves –encourage the reader to “learn to love [the] very thing you currently hate.” Monster stories geared towards young people, whether in classics from the 1800s or in modern Young Adult novels, are a great opportunity to warn young readers of the dangers of self-hatred and the power of loving and accepting yourself.

In The Dream Thieves, Ronan’s self-hatred is literally a threat against his life. His dreams are filled with monsters that hate him as much as he hates himself, and he has to contend with these monsters when he brings them into his waking life. After accepting his sexuality, his monsters – and his self-hatred – are transformed similarly to how Gressel describes the meaning of monster stories happening when something “we despise is transformed into something beautiful.”

#the dream thieves#monsters#monster theory#literature#the raven cycle#ronan lynch#beauty and the beast

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monsters and Self-Acceptance: Twilight

Twilight and the subsequent books follow 17-year-old Bella Swan and her romance with Edward Cullen, a vampire. Much of the books’ conflict stems from the danger Edward’s vampirism puts Bella in. This is also where much of Edward’s self-hatred stems from. Over the course of the series, however, we see this self-loathing diminish as Edward realizes he is worthy of the love Bella shows him.

Throughout the books Edward often professes hatred at what he is. Part of this self-loathing is related to his beliefs on morality. As Edward’s father explains, Edward “doesn’t believe there is an afterlife for our kind… he thinks we’ve lost our souls” (73). He does not believe a vampire, a creature as monstrous as he, could possibly have a soul, and even if he did have one, the human lives he took in his earliest years as a vampire would damn him regardless.

A larger part of his self-loathing is rooted in the danger he poses to Bella. As a vampire, he thirsts for her blood, and his presence in her life brings other dangerous vampires to her, but he cannot bear to leave her. He tells Bella, “I infuriate myself. The way I can’t seem to keep from putting you in danger. My very existence puts you at risk. Sometimes I truly hate myself. I should be stronger... I love you. It’s a poor excuse for what I’m doing, but it’s still true” (641). He believes someone braver than he would simply leave Bella to keep her safe, and loathes himself for refusing to do so.

In one of the most memorable scenes of the series, the meadow scene, Edward explains to Bella exactly the danger he poses to her, but Bella declares, “I would rather die than stay away from you” (487). To this, Edward muses, “and so the lion fell in love with the lamb… what a sick, masochistic lion.”

Tracy L. Bealer, in Bringing Light to Twilight: Perspectives on a Pop Culture Phenomenon, describes how this line reflects Edward’s self-hatred and the journey he takes to unlearn it. She remarks that the “depth and power of [Edward’s] self-loathing… derive from a profound hatred of himself stemming from his dangerous body” (120). She goes on to say,

“by calling himself a ‘sick, masochistic lion,’ Edward reveals… that he understands himself to be wicked and contaminated because his vampirism renders his body inherently predatory. However, his second defining term, “masochistic,” is both insightful and misapplied. It is not his masochistic desire to expose himself to the temptation Bella embodies that causes Edward’s torment… this masochism is actually his salvation. He has convinced himself that his transformation into a vampire has cost him his soul, and he has internalized this perceived loss by identifying himself as a “monster” doomed to destroy Bella” (120).

This speaks to the role Bella’s love has in Edward’s journey of unlearning his self-hatred. He sees his relationship with her as “masochistic” because of the danger he poses to her (though Bella adamantly says multiple times she does not care), but it is this relationship that is actually his “salvation.”

At the beginning of the story, he cannot comprehend how a monster like him could be deserving of Bella’s love, and often expresses this confusion to her. In one early scene in Twilight, Bella proclaims, “I’m absolutely ordinary” and Edward tells her, “You don’t see yourself very clearly, you know” (375). Later, when Edward asks Bella how she can bear to be with such a monster, Bella tells him same thing: “Do you remember when you told me that I didn’t see myself very clearly? You obviously have the same blindness” (861). While Edward does not understand how Bella can love him, she does not understand how he cannot love himself.

At almost every facet of Edward’s self-hatred, Bella disagrees. She does not view him as monstrous or doomed as he does. In fact, she believes the opposite. Bella says Edward is “more angel than man” (49). It is clear in the beginning of the story that Edward does not share Bella’s high opinion of himself, despite her insistence; however, by the final book, Breaking Dawn, Edward has come to terms with being a vampire and embraces living forever with Bella. In this book, Edward is forced to change Bella to save her life, and she becomes a vampire. When she is transformed into a vampire, the monster that he has always been, Edward still loves her just as he did when she was human. He tells her, “I am completely amazed” (733) about her beauty and retained humanity. In her, he is able to see the beauty that she had spoken so high of, and he revels in the fact that being vampires will allow them to spend eternity together. Finally, his fate does not seem so monstrous, and the love Bella showed him becomes love he shows himself as well.

Both stories discussed here lay a roadmap for young readers to forgo the self-loathing they may feel at certain aspects of themselves. Reader can to find love and adoration for characters who have yet to find love for themselves, and in watching these characters find ways to accept shunned and monstrous parts of themselves, they can be encouraged to embark on their own journeys of banishing self-hared.

Perhaps this is why there are so many memorable stories of monsters being transformed by love and self-acceptance, such as the recent The Shape of Water and the enduring Beauty and the Beast. Regarding this last story, psychologist John Gressel P.h.D., says the story encourages us to “find the beauty in the beasts in our lives.” He tells readers to

“Think of some part of you or your life that you don't like, can't accept, wish were otherwise… some aspect of yourself or your circumstances that has you feeling trapped, that you hate, that you want to go away or to escape from. According to this tale… you must learn to love this very thing you currently hate... Until you do, you are trapped in this prison cell of not accepting yourself or your life as it is. It is only through this kind of self acceptance, genuine and complete, that… we can unite with this previously unacceptable feature of our lives and live happily ever after. This is when that which we despise is transformed into something beautiful.”

In Beauty and the Beast, the Beast is literally transformed by earning Belle’s true love. As Gressel points out, Beauty and the Beast – and Twilight I would argue –encourage the reader to “learn to love [the] very thing you currently hate.” Monster stories geared towards young people, whether in classics from the 1800s or in modern Young Adult novels, are a great opportunity to warn young readers of the dangers of self-hatred and the power of loving and accepting yourself.

In Twilight, Bella helps show Edward that he is not a monster, and that being a vampire could have the benefit of allowing them to be together forever. This radical love causes Edward to… In The Dream Thieves, Ronan’s self-hatred is literally a threat against his life. His dreams are filled with monsters that hate him as much as he hates himself, and he has to contend with these monsters when he brings them into his waking life. After accepting his sexuality, his monsters – and his self-hatred – are transformed similarly to how Gressel describes the meaning of monster stories happening when something “we despise is transformed into something beautiful.”

#twilight#monsters#monster theory#young adult#edward cullen#bella swan#literary analysis#the twilight saga#breaking dawn#new moon#eclipse#midnight sun

27 notes

·

View notes