Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

You're never getting rid of me!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have you been seeing things?

Have they been haunting your dreams?

#08 feb 2025#music#i don't usually post music before it's Ready ready#but i've thought about nothing but this track for 2 days#so i have to inflict it on everyone else to save myself#am i working on a new album? maybe. hopefully. we'll see.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghost Lights

Words: 4,383 Tags: Fantasy, Noir Warnings: Gore, hand injury

***

The ghost on Isa’s desk tapped politely against the green glass of its lantern. Isa didn’t look up, intent on getting the invoice to her latest client written up before midnight. Rain spattered against the window. The lamps fluttered in a draft from some-damn-where.

Labor – 16wt. Lantern – 80wt. Travel & Lodging Reimbursement – 30wt.

Thunder trundled down the street outside. The ghost tapped on the glass again. Isa’s fingers tightened on the pen.

Fee & Fine Reimbursement – 25wt. Whining Surcharge – 5wt.

The ghost dragged its nails down the glass. The pen’s nib tore through the paper. Isa slammed the pen down, printing a firework of ink on the invoice, and glared at the lantern on the corner of her desk.

“What?�� she snapped.

Vague limbs stirred behind the green glass. Something like an arm made overtures at the window.

“No,” said Isa. She crumpled up the ruined invoice and pitched it at the waste bin. She took out a fresh sheet of paper and smoothed it on her desk.

The lantern rattled. The ghost moaned, a mouse-sound, tinny and distorted.

“Use your words,” said Isa, starting the invoice over.

Attn. G. Palacios Re:Services Rendered….

Keep reading

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

GuMo Diaries, Epilogue: A Story About Mountains

This epilogue has a prologue, but it isn’t mine to tell.

In unromantic itinerary terms, it was the kind of logistical Rubik’s Cube that my brain seems to latch onto as the ideal vacation:

Sunday: drive 4 hours to Dallas to meet my sister (who was flying in from Georgia) and eat at the infamous Rainforest Cafe;

Monday: see the Great North American Total Solar Eclipse of 2024 before driving 8-9 hours to Carlsbad;

Tuesday: see The Caverns plus Ranger-Guided Tour;

Wednesday: drive my sister to El Paso (3ish hours) for her to fly home before returning myself to Carlsbad for

Thursday-Saturday: 3 days of hiking in the Guadalupe mountains; followed by

Sunday: drive 10-11 hours back to Houston in a single day in order to return the rental car (and return to work) on Monday morning.

Having accomplished the entire trip, I feel confident in saying that everything prior to the Mountains is my sister’s story. Should she decide to write about it in a public forum, I’ll point you to it.

This story is about the Mountains.

Keep reading

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

She won't look at me. She hasn't looked at me in weeks, not since her eyes first slid off me in the ruins of Gialos, ash and sapphire dust freckling her face.

"Morning, Liz," I say. "I made scones."

She glances at the tray and flinches like she's looked into the sun. My hands. I've washed them a thousand times, resorted even to magical scouring, but I think she still sees them as they were. Ash and sapphire dust.

I set the tray down and step away. I clasp my hands behind my back.

"Thank you," she says. "I didn't know you knew how to make scones."

"I learned," I say.

While you were gone, I don't say.

Because you used to make them, I don't say.

The dull echoes of the chamber add: Because you don't remember what she actually likes for breakfast.

Liz keeps looking at the scones. The morning light falls watery on her face, washing her out. Her eyes are red around the rims. Sometimes it takes her a long while to build up the momentum to eat.

It might be easier if we weren't holed up in the Tower of Dread, but honestly, where else could we go? Just because the mobs gave up on swarming the gates doesn't mean their component parts aren't still out there. They might not recognize Liz - the family resemblance isn't that strong - but they'd recognize me.

Everyone recognizes me. I'm the hero of Gialos.

I could send her away. That might fix it. This is the most defensible position in the kingdom, maybe the world, but it can't protect us from things that are already inside. She hates it here, although she's never voiced a complaint. I'm not a fan of it, either. There hasn't been much time to redecorate, to scrub the memories off the walls. I don't know if that would even work. If, like my hands, I'd always be able to see the places where the bloodstains aren't. If, like Liz, I'd watch the corridors disintegrate in my dreams.

Who am I kidding? I can't send her away.

"Where did the butter come from?" Liz asks abruptly.

I blink back into the moment. "What?"

"Scones need a lot of butter. Where did you get it from?"

"How do you know there's a butter shortage?" I blurt.

Liz gestures out the window, the jagged-rock city filled with ravens and vultures, the razed forests and salted fields outside the walls. The bloodstain spreading from this knife plunged into the heart of the world.

I look someplace else. My hands clench behind my back. I stopped wearing my sword because it made her nervous, the way I'd hold it with white knuckles at my hip. How could I explain it to her? That sword was my best friend.

Or at least, the only friend who survived the quest.

But it made her nervous. Gone are the days when all my problems could be solved with a sword. Crushed into sapphire dust and blown away with the ash.

"I did everything I could, Liz," I say.

"No you didn't," she says.

I can't look out the window. I haven't looked out the window in weeks. There's a fine, needle-sharp pain in my hands, a thousand glassy splinters buried just under the surface.

Liz picks up a scone and takes a bite. Crumbs spill onto her hand, get caught at the corner of her mouth. Her eyes stare through the tray. The way the sun catches in her hair, it fuzzes her outline. Motes of dust swirl in the light. Suddenly I can't breathe. There's a scream wedged like a stopper in my throat.

"Is there tea?" she asks, mouth half-full and dry.

I turn my back. I swallow the scream. "I'll make some."

My footsteps echo in the empty halls. The ravens and vultures squabble over the ruins. Down in the cellar, the Ash King's butter stores lie cold as a corpse, decaying, with nothing to replenish them. All the cows are dead. All the farmers were driven out. All the crops burned. The kingdom is starving and I made scones.

Liz didn't ask to come back.

I did everything I could, I tell myself.

No, the empty halls whisper back, you didn't.

You are the adventurer who went on an epic quest and defeated the evil king, all to gain the sacred amulet and use its one wish to revive your sister. Now everyone expects you to accept her death and use the wish to undo the damage instead. You refuse.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Recondite

Words: 7,029 Tags: Urban fantasy, horror Warnings: Gore, animal death, drug abuse, body horror, queerphobia

***

The city’s winter coat is brown and gray.

By January, every scrap of green has withered or sloughed off or been trampled into mud. Even the sky goes the color of dust on silver, piped out of the smokestacks that cluster like tube worms around the port. The Thing in the Gulf—storm god, old one, demon, fiend; whatever it is, it’s above my paygrade—lies in fitful hibernation, dreaming ravenous heat-sweat dreams of hauling its howling carcass ashore. It overwinters in the Sigsbee Deep.

We think. No one dumb enough to go looking has ever come back.

A low traffic rumble and the shriek-and-chatter of grackles cover my squelching footsteps as I make my way under the long arc of I-45, high halls, a concrete cathedral. Sparse graffiti mottles the great gray pillars. Brightly-colored trash outcrops in bare spots: green glass bottles, blue plastic tarps, fabric flowers, paper packages. Offerings, scattered.

Some people will pray to anything. Some people have no choice.

Something wretched is stirring in Third Ward.

Keep reading

#31 mar 2024#urban fantasy#horror#gore /#animal death /#drug abuse /#body horror /#queerphobia /#think 'dresden files' if harry dresden were 24 and trans and aware of white supremacy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

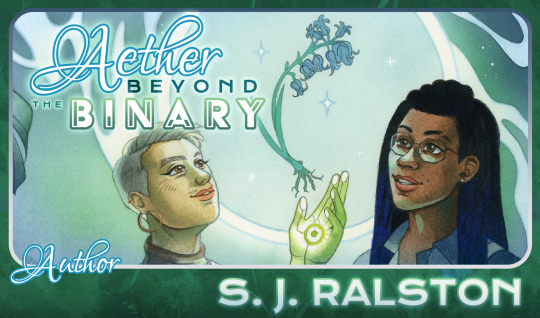

Meet Aether Beyond the Binary Contributor S. J. Ralston

We’re entering the final week of the Kickstarter campaign for Aether Beyond the Binary, an anthology of 17 aetherpunk stories starring characters outside the gender binary, and we’re still going strong! As I write this, we’re $3,700 shy of our goal – an amount we definitely can raise, but the more help we get spreading the words about this project, the more people will know it exists, and truly that’s the single biggest barrier to hitting our goals: effectively spread the words. So, if you believe in this project, whether you’re a backer or not, we’d really appreciate you taking a moment to share/reblog/retoot/reskeet our posts about it!

Bluesky

Facebook

LinkedIn

Mastodon

Pillowfort

Tumblr

Thanks for all your support! Now, let’s introduce another of our contributing authors…

About S. J.: S. J. grew up in a distinctly weird, distinctly southern hometown, then hied out West for grad school before landing in Texas, where they currently work as a planetary scientist. They’ve been writing original works and fanfiction since they could hold a pencil semi-correctly, and continue to write both whenever possible (as well as still holding a pencil only semi-correctly). In their clearly copious spare time, S. J. enjoys hiking, tabletop RPGs, jigsaw puzzles, and enthusiastically crappy sci-fi.

Link: Personal Website | Tumblr

This is S. J.’s first time writing with Duck Prints Press. You can read another example of their writing by visiting their website to check out Anglerfish, a horror sci-fi story.

An Interview with S. J. Ralston

How did you pick the name you create under?

It’s a line from the opening of the Aeneid that’s stuck with me ever since AP Latin in high school: “On account of the mindful wrath of cruel Juno.” It’s a synchesis, where the adjectives have been swapped from where you expect them to be; it’s Juno who is mindful and her wrath that is cruel, but rearranging them in such a way elegantly implies the relentless, vindictive onslaught that is to follow.

What do you consider to be your strengths as a creator?

Dialogue and dread.

What do the phrases “writer’s block” or “art block” mean to you?

The state of wanting to create but not having the intellectual raw materials to do it.

Are you a pantser, a planner, or a planster? What’s your process look like?

I would consider myself a plantser. Typically I start with an IDEA, writ large, center of the page. Then some key scenes will populate around it–dramatic moments, fun bits of dialogue, cool setpieces. At that point I get out my corkboard and red string and start trying to piece everything together, and if I’m lucky, the shape of the story will reveal itself to me. Sometimes it’s the classic parabola of rising and falling action, other times it’s been a ring, a tri-fold posterboard, a descending spiral, or a series of concentric circles. Then I fill in until the structure is complete and hope like hell that I can stick the landing.

What are your favorite tropes?

Found Family, Robots With Feelings, Enemies To Lovers, Destructive Romance, Kirk Summation/The Man In The Room

What are your favorite character archetypes?

Brooding Loner Secretly Just Lonely, Lying For Fun And Profit, Badass With An Obvious Dump Stat, Too Old For This Shit, Taciturn But Bizarre, Himbo

Do you like having background noise when you create? What do you listen to? Does it vary depending on the project, and if so, how?

I make a playlist for almost everything I write that’s longer than a few thousand words. Sometimes it’s for listening to while I’m creating (in that case, it has to be primarily instrumentals or I’ll get distracted), and sometimes it’s just for daydreaming to (in which case, the vibes must be correct, so I can construct AMV’s in my head).

Share five of your favorite books. (You can include why, if you want!)

Feet of Clay by Terry Pratchett – Eerie, funny, and poignant in equal measure; a police procedural done right.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke – Lush with joy, curiosity, and love, yet still remarkably dark, with an ending that will nestle in your brain forever.

Artemis Fowl: The Opal Deception by Eoin Colfer – Fourth in the series and the absolute pinnacle thereof. A master-class in shit hitting the fan.

Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu – Everyone, down to the most momentary background character, behaves more like *people* than any I’ve ever read before and it’s *disastrous* and I *love* it.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson – The classic of classics. The horror of horrors. The transgenderism of it all.

What are your goals as a creator?

(1) To write something that’s better on the second read-through than it was on the first, and (2) To write something that stays with the reader.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

When you finish a first draft and you *know* you’ve got something really good, put it down. For a month, six months, a year; until the glow fades, or you’ve fallen in love with whatever you’re writing next. Then come back and re-read that first draft. Take extensive notes, diagram the plot, profile the characters. Notice the holes, redundancies, missed opportunities, and inconsistencies. Then open up a blank document and *start over.*

S. J.’s Contribution to Aether Beyond the Binary

Title: Razzmatazz

Tags: bipoc, body horror, butch, character injury (non-graphic descriptions), classism, dehumanization, eye horror, horror, humans are the villains, mechanic, minor character death, misogyny, murder (accidental), non-binary, non-human character, past tense, sentient construct (magical), third person limited pov

Excerpt:

The thing was damn near unrecognizable, not just as Marilyn Monroe, but as human. People had tweaked the proportions through the years—amateur artists who couldn’t put down the paintbrush. That kind of thing was bad enough on paper, but seeing it in person made Skipper’s butthole clench.

The dress and the curls were Monroe. The rest was something else.

“Shit my ass off,” Skipper said under his breath.

“Yeah,” said Charlie.

“This gets up and walks around?”

“She does.”

“Shit my ass off.”

Maybe it was a trick of the light, a too-heavy head on a too-thin neck, but the Monroe wasn’t staring across the aisle like the others. It seemed to be looking down at Skipper. It put out waves of dare-you-to-start-some-shit energy.

“Is it because they messed with the proportions?”

“Huh?” said Skipper, pulling out of the Monroe’s tractor beam.

“The reason she moves around so much. Could it be because of…” Charlie gestured to its whole body.

“Hell, maybe,” said Skipper.

The Monroe loomed like a landslide, just waiting for the rain. Skipper had a hammer on his belt. He felt like the Monroe was staring at it. If he broke the case, what then?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

COVER REVEAL: Aether Beyond the Binary!

Duck Prints Press is over the moon to announce that the crowdfunding campaign for our next anthology, Aether Beyond the Binary, will be launching on Kickstarter on December 26th, 2023. This awesome collection includes 17 stories about characters outside the gender binary – be they non-binary, agender, genderfluid, bigender, or elsewise – exploring, learning, growing, teaching, helping themselves or helping the world in settings like the modern world, but with magical aether powering the technology!

Our spectacular cover, which we are thrilled to reveal today, features art by non-binary artist Mar Spragge. The lead editor, Nina Waters, is agender. Many of our contributors are also trans and/or non-binary. You can see the full list of contributors here.

The crowdfunding campaign for this book will include options to buy the anthology as an e-book, trade paperback, or hard cover, and we’ve also got some gorgeous merchandise, with an enamel pin by Atomic Pixies, a bookmark by Pippin Peacock, a sticker of the back of the book cover (because the book cover is FULL WRAP-AROUND, wut?!), and of course a sticker of our latest Dux, created by Alessa Riel.

The campaign goes live on December 26th, 2023. To get all the details and make sure you don’t miss a thing, follow our Kickstarter Pre-Launch Page NOW!

Signal boosts are extremely appreciated on this post. This is a super cool project and we want to get the word out about it. And I mean, look at the lovely artwork. You know you need that lovely artwork on your blog/page/feed/whatnot. 😀

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anglerfish

Words: 13,750 Tags: Horror, Sci-Fi Warnings: Gore, panic attacks, suffocation, POV character losing their grip on reality

***

We’re about a hundred light years out from Vega, four days into a 33-day long-haul, zipping along at our peak-efficiency speed of Warp Five and just bored enough to start exiting our skulls, when the computer flags something up on my screen.

Possible Signal Detected!

I yawn as I click through. The computer thinks it’s soooo good at detecting signals. What it’s really good at detecting are pulsars and Cepheids and all those other celestial objects that honk like cosmic foghorns, uncrewed. I’ll listen anyway because there’s literally nothing better to do, and sometimes it’s nice to hear a friendly foghorn in the distance.

Except this time, the computer gives me nothing. It’s just the random pops and clicks of deep space, the antenna reading the stars like sheet music. That’s never happened before. I stuff a finger in my non-earpiece-ear to hear better, and still, nothing. Nada. I crank the volume up.

Then I do hear it, and break out in goosebumps all over.

So faint it’s barely there, just a whisper on the antenna, three chirps, three beeps, three chirps. Then a pause. Then it repeats.

I start a frequency sweep, low to high, and it’s always faint but it’s always there. Dit-dit-dit-daa-daa-daa-dit-dit-dit. Broadcast in radio white noise, which you are never, ever supposed to do.

With one exception.

Keep reading

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I read your story Powered a long time ago, but never finished it. I've been trying to find it again, but it's not on ao3 anymore. I was wondering what happened, and if possible, re-read it? It's fine if not, just wanted to ask.

Ah, so "Powered" was taken down... quite some time ago, to be rewritten as a fully original story. At this point, the rewriting is done and I'm currently shopping it around to agents. If I don't get any bites by the end of the year, I'm planning to go self-pub with it.

So sooner or later, the story will return! Not in the same form (it's about half as long, for one), but with the same soul.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ISSUE #6 IS HERE!

What a joy putting together this issue was. From daddy kinks to trans vampires to an alcohol that gets you drunk before you drink it, this issue touches on the wacky, wild, and wonderful that we at OFIC love to see.

PURCHASE ISSUE #6 HERE.

Issue #6’s cover, “Statues by the Stream,” was created by Idan.

WAYS TO ENGAGE WITH OFIC:

Become a patron (the best way!)

Leave us your comments! If a piece spoke to you and you’d like us (and the author) to know, fill out this form.

Share your excitement on social media using the hashtag #OFICMag6!

Check out our store for cool merch & backstock!

THANK YOU ALL SO MUCH FOR YOUR SUPPORT. HAPPY READING!

site | subscribe | submit | faq

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The sequence always goes the same:

Detect radio transmissions from a far-distant world; surefire signs of intelligent life. Pony up, but don’t get too excited.

Triangulate. Hyperdrive. Pop back out occasionally to make sure you’re still getting the signal. Work on translation.

Reach the Silent Front. The point where all the radio transmissions go quiet. Sometimes thousands of lightyears out, sometimes as few as ten.

Brace yourself.

Reach the planet. Send messages into the ever-expanding bubble of silence all around you. Land, search. Find only ruins. Move on.

Miguel and I have been SETI runners for about ten years. In that time, I’d guess we’ve found a couple hundred dead worlds. I stopped keeping count in the early twenties. Miguel might know the exact number.

The first one wasn’t honestly the worst. It was a shock, sure, but it’s the kind of thing that should be shocking. And we knew it was coming, to some extent. The Silent Front was six hundred lightyears out. We knew well before we got there that we’d missed them, that whatever civilization had been there would be long gone by the time we arrived. I think we joked about Krypton, or about them packing up and leaving. Our translators weren’t as good back then, so we’d only gotten a few words out of the radio noise.

And when we got there, everyone was dead. It had been six hundred years, so things were pretty thoroughly decayed. We figured they must have been soft-bodied, whatever they were, because we never found any skeletons.

A damn shame, but the Universe was bigger in those days. We took notes, scavenged what supplies we could, and moved on.

The second one wasn’t the worst, either, although it was a hell of a gut-punch. We picked up the signals way far out, thousands of lightyears, long enough to get a good head-start on the translations. Miguel’s a wizard with that kind of stuff--me, I just run the engines, mostly--but whenever we had down-time, he’d tell me about the place we were going, like a bedtime story. All I remember about it now is that they had sports. We couldn’t make head or tail of them, but they were a big deal.

Early on, at least.

The games trailed off as we got closer. The major international tournaments got canceled. The way we hopped in and out of hyperdrive, we were skipping a few dozen years of broadcasts at a time, so we didn’t get to know any people, but we got to know nations. Plucky little nations and big bully nations, snooty nations and friendly nations, rich nations and poor nations. We noticed when certain ones stopped showing up.

We hit the Silent Front fifty-eight lightyears out, and it took the wind out of both of us. We kept hoping for another transmission, a ham station, an SOS, anything.

When we got there, it took us a while to figure out what had happened. The atmosphere was full of CO2, but everything under it was charcoal. We had to get a scientist on the line--tough job--to ask: how do you burn anything without oxygen?

And the answer was: you don’t. Turned out the atmosphere had been about sixty-forty methane and oxygen--before. The aliens never even got around to using their worst weapons of war because they incinerated their whole fucking atmosphere with the first test-fire. So we took notes, scavenged, moved on. It still wasn’t the worst.

No, I think the worst was Number Five.

Because we were hoping, right? We were hoping. Four dead worlds in a row was a bad streak to be on, but we knew by then how common inhabited worlds were out in the Universe. We kept stumbling on them. They were all over the place. Four in a row wasn’t bad odds.

Miguel had started drinking, but it wasn’t bad yet.

Number Five. We picked them up a few hundred lightyears out, so they were pretty new to Stage 2 tech. Miguel asked me to take it slow on the hyperdrive hops, take our time, give him a lot to work with for the translators. Usually we could do a few hundred lightyears in a week, but getting to Number Five, we took almost a month. Getting more and more excited every time we popped down and heard more radio signal.

“Chatty one,” I’d comment to Miguel, while music and talk shows and all kinds of pings and zwips gabbled out of his receiver.

“They have a lot to say,” he’d tell me.

“Let’s hope so,” I’d say.

Fifty lightyears out, we were still getting signal. Ten lightyears out, we were still getting signal. One lightyear out, and we were still getting signal. On the last hyperdrive leg, Miguel started teaching me some of the words--hard to put together with a human mouth, but we figured they’d appreciate us trying, in addition to the computerized translators that would do the heavy lifting for us.

I think we danced on the bridge that night. I don’t think we slept at all. How could we?

And we came out in silence.

Less than a year, we missed them by. We don’t know what happened. At a guess, it was some kind of bioweapon, because all the buildings were intact.

Filled with rotting corpses, but intact.

After that was when the numbness set in. It had to. It was that or quit, and I think there’s some brittle-iron part of both of us that’s determined to see it through. We agreed without ever agreeing: we do this until we find a live one, or until we keel over.

Miguel still puts in some work on translation when we pick transmissions up, but not too much. It’s mostly to pass the time these days. He also drinks like a fish, and I don’t blame him. You do whatever it takes to survive.

But I’ve been thinking, you know, maybe we should take a trip back to Earth. Maybe we should go drop off our latest batch of findings to SETI in person.

Maybe it would do us both some good to come home, to the one place in the Universe where we know there’s no silence.

When humanity enters the galactic stage we find that our history of violence is quite unusual, but not because we wreaked unimaginable death and destruction upon each other, but rather because we stopped eventually.

4K notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pirra

Words: 2,762 Warnings: Child abuse, body horror, self-harm

...

When they speak of her at all, they say she was a girl, once. They say she had a mother and a father (and sometimes a brother and a sister), a name, a face that was not ash and furnace-glow. They say she lived in a village much like this one, a long, long time ago.

They say: it was a hard winter, and her family was very poor.

Snow covered everything deeper than a horse’s knees, all slush and slipping mud in the roads. The pines creaked all day long, and at night they cracked like gunfire. The wells froze solid. The sun, when it pierced the hard gray clouds, shone down knives.

Her name was Pirra, they say, but they do not speak her name too loudly.

Her name was Pirra, and she was always hungry.

Pirra’s father was a lean man, a whipcord man, toughened leather. Her mother was a flint knife. Her brother and sister (in the stories where she had a brother and sister) were bow and arrow, string and harp. Pirra was a girl, they say, once. They kept a small plot of crops, a small pen of chickens, a small cottage in the village—long gone now, of course.

In Pirra’s ninth year, the winter crashed down early, icy bones falling across the land before the light of the harvest moon. The late-ripening grain rotted in the field. The chickens would not lay. Some families had deep stores of turnip and yam, potato and beans. Pirra’s family had less than half their usual harvest, and even the usual was never quite enough. By the time the deep of winter set in, they had eaten through their stores and even their chickens. They were all thin and cold and hungry—but thinnest and coldest and hungriest was Pirra, who was also the youngest and the smallest and could work the least.

Still, “I’m hungry,” she would say.

“Don’t work, don’t eat,” her father liked to say, for it was what his father had told him, and what all the men in the village said to each other.

“There isn’t enough food for everyone,” her brother (when she had a brother) told her quietly. “If you starve, we might not.”

“Mother and Father can make a new baby once there’s more food,” her sister (when she had a sister) added.

“There is nothing here,” her mother said. “If you are hungry, go away and find something to eat.”

So Pirra put on her sheepskin boots and her thick coat and went out into the cutting cold.

First she went to the family who grew turnips, for their home was near hers and there was smoke rising from their chimney. She knocked on their door, although the cold wood blistered her knuckles through her threadbare mittens.

The Turnip Father answered the door, though he opened it so little that only a spun thread of warmth fluttered out from inside.

“Little Pirra,” he said, “what do you want?”

“I am cold and hungry,” Pirra said. “Will you give me a turnip to eat?”

The Turnip Father said, “What will you pay me for my turnip?”

“I can’t pay you,” Pirra said. “The winter has been long and we have nothing to sell, so we have no money. My father said you have many turnips; can’t you spare one?”

“If I give away one turnip for free, soon everyone will want free turnips,” the Turnip Father said. “Then I will have no food and no money, just like you. Go away, little Pirra. I cannot help you.”

He shut the door in her face, cutting the thread of warmth.

Next, Pirra went to the schoolhouse where she and the other village children learned to stay out of their parents’ way until they were old enough to help in the home or the fields. The schoolhouse was far, and her boots filled with sharp bits of ice. There were no children inside, but the teacher was there, with a feast of red meat laid on her desk before her. Pirra tapped on the window and tapped and tapped until the teacher came to the glass.

“What do you want, little Pirra?” Teacher asked.

“I am cold and hungry,” Pirra said. “Will you give me some of your meat to eat?”

Teacher frowned. “This meat is the horse I was given for teaching in this village. It is the only horse I had. Why should I share any with you? I have seen many children much colder and hungrier than you.”

“But I am cold,” Pirra said. “And I am hungry. My family has no food and no money, so we have no logs for the fire and no food for our bellies. If you don’t help me, I will only get colder and hungrier.”

“When you are as cold and hungry as the other children were, then I will share what I have with you,” Teacher said. “Go away, little Pirra. I cannot help you.”

So Pirra walked through the village, her feet freezing in her boots. The sky was iron gray. Her stomach was a hard knot of pain. Her hands were all the way numb.

A breath of warmth touched her face. She followed it with eyes closed until she came out of the deep snow. She had found the blacksmith, his forge glowing hot. Pirra did not come right in, for the blacksmith was cruel, and did not like little children. When she didn’t see him out in his shop, she crept close, into the heat spilling from the forge. The ice in her hair and in her boots and on her hands melted. She watched the red light dance on the coals and chewed her tongue.

“Little girl!�� a great voice boomed. “What are you doing here?”

Pirra turned in fear. The blacksmith stood in his leather apron, his body and arms streaked with soot, his great hammer in his great hand.

“I am c-cold and h-hungry,” Pirra said, shaking with fear more than cold.

“Cold and hungry?” said Blacksmith. “That is a terrible thing. Little girls should not be cold and hungry.”

“My family has no food and no money,” Pirra said. “No one in the village will help me.”

“Poor thing,” said Blacksmith. “Then I will help you.”

“You will?” said Pirra, tears gathering in her eyes.

“If you are cold and hungry, why, then eat the coals from my fire!”

And he laughed and laughed.

Pirra clenched her teeth. Tears slid down her cheeks and froze on her chin. She turned her face to the fire to melt them. Red light danced on the hot coals. Pirra reached out her hand and plucked one up. Her mitten singed and smoked, but her hand was all the way numb. She put the hot coal in her mouth and it burned her tongue bright red. She crunched it up and it burned her teeth black. She swallowed and it stained her throat with pain, sizzled in her stomach.

But Pirra was still hungry.

She reached out her other hand and picked up another coal, crunched it up and swallowed it. This one burned worse than the first, but it was warmer than the first, too. She ate a third and a fourth and smoke came out her nose and her mittens smoldered away. Blacksmith grabbed her by the back of her coat and threw her away from his forge.

“Stupid girl!” he snarled. “Go away from here, go home, or I will strike you with my hammer!”

The hot coals burned in Pirra’s belly. She crawled away from Blacksmith and his great hammer, though the cold snow bit her hands and knees. Somehow she was even hungrier than before.

Everyone had already turned her away or pretended she wasn’t there, so, like Blacksmith told her, she went home.

Pirra’s brother (if she had a brother) was outside when she got there, chopping up a thin, wet log for firewood. He stopped when he saw Pirra coming down the road.

“What are you doing back?” he demanded.

Pirra came closer. His breath sparkled icy in the cold air. His warmest coat couldn’t keep all the heat of his body inside. The coals in Pirra’s stomach were dimming, dimming.

“I’m hungry,” she said. She came closer, and closer still.

“You were supposed to go away and freeze to death,” Pirra’s brother (if she had a brother) said. The warmth of his breath touched her face. “We will only survive if there’s fewer mouths to feed.”

So Pirra caught her brother (if she ever had a brother) by the throat, and she ate him. All his hot blood and warm breath filled her belly and fed the four hot coals from Blacksmith’s forge. She spat out his coat and his sheepskin boots and his furry hat and left them lying in the deep, deep snow. She wrapped her arms around her swollen stomach while the coals burned inside.

But Pirra was still hungry.

Still holding her belly, she shuffled inside. There was no fire, just her father and her mother and her sister (if she had a sister).

“I told you to go find something to eat,” her mother said. “Did you find something?”

“Yes,” Pirra said. It was cold in the house, perhaps colder than outside.

“Where?” her sister (if she had a sister) snapped. “What did you find? And why didn’t you bring any for us?”

“It wasn’t enough,” Pirra said. “I’m still hungry.”

“Greedy, useless, stupid! Where is my brother? We’ll beat you to death if you don’t have the decency to die on your own!”

“Outside,” Pirra said.

Pirra’s sister (if she had a sister) stormed past her, without bothering to put on a thick coat or a hat. She went around the house to where the log still lay unchopped, where her brother’s coat and boots and hat lay in the deep deep snow. Pirra came, too, following the spilling-out warmth from her sister’s body—if she had a sister.

“Where did he go?” Sister demanded. “Where is my brother?”

She turned and saw only Pirra, with her burned hands and her coal-black teeth, with her swollen belly and no brother. Pirra’s sister stood too still in the sharp-cold air and froze solid, an arrow without a bow, an unstrung harp. Pirra ate her whole, but spat out her boots and her mittens and her long hair. The coals in her belly glowed hot and bright and painful, filling up her veins with fire that only made the rest of her feel colder. Her belly was so swollen that it felt like it would burst, so Pirra grew larger to make room. But the growing burned up her brother and her sister (if she had a brother and a sister), and there were only the coals, and a much bigger and so much emptier stomach inside. Even though she’d eaten more today than ever before, Pirra was still hungry.

She went back inside her cold, dark house. She ate her father first, then her mother, a whipcord and a knife-edge. Their screams were barely warmer than the air inside her house, and their thin, cold bodies did not nourish the coals in her belly. Her mother’s sharp edges cut her mouth and throat and her father’s toughness refused to be digested. Pirra spat out her father’s skin and her mother’s bones and the blood they’d drawn on the way down.

She was still hungry.

She broke her father’s rocking chair into pieces and ate it, though the splinters stuck in her throat. She smashed her mother’s spinning wheel and ate it, spokes and all. She devoured the beds and the stools, the table and the chairs. She swallowed the unlit stove and its cold iron almost snuffed out the coals in her belly. She pulled down the curtains and tore up the floorboards, smashed out the windows and ripped off the roof, chewed it all to splinters and matchsticks in her burned and bloody mouth. Her stomach bulged and distended, full of jagged pieces, so she grew larger again. Her clothes tore apart as she moved, leaving her skin to blister in the knife-cold air. The wood was wet and didn’t burn well. Smoke poured out her mouth and her nose and her ears.

Smoke came from the Turnip Father’s house, too, and a breath of its warmth brushed her face. She crossed the street and struck his door with her fist. The wood came apart against her blistered knuckles. She ate it so it wouldn’t go to waste. The Turnip Father screamed and shouted at her, so she ate him, too. She reached into the house and grabbed their hot burning stove, crushed the iron between her teeth and let the warmth scald her throat. But the stove couldn’t stay warm outside, and soon the iron was a cold hard knot in her belly.

And she was still hungry.

The Turnip Mother and the Turnip Children all fled towards the middle of the village in their socks, without their hats or coat. Pirra followed the bright-spark warmth of their bodies through the cold snow, under the cold sky. She caught the Turnip Mother banging on a closed door and ate her. The Turnip Children ran into the schoolhouse, but Pirra could feel them all huddled warm inside, and she smashed the window to pull them out. She had to stretch out her arms longer to reach all of them, had to grow her fingers into claws to pry them out of their hiding places. It hurt so much, but they were so warm and she was so cold. She was hungry enough to eat Teacher, too, and all of Teacher’s horse. She had to grow a third time to make room for all of them, even though she’d just stretched out her arms.

Nothing she ate made her less hungry, and all the bodies turned cold as soon as they were in her belly. Only the coals were still hot in her. She lumbered down the street to Blacksmith’s shop, where the forge burned bright and red. She scooped up coals by the handful and stuffed them in her mouth, crunching the pain between her teeth, covering her face in ash.

Blacksmith ran out with his hammer and hit her hands and arms. She stuffed him into his forge to warm him up before she ate him. She spat out the hammer on the ground. She ate all the hot coals and all the warm stones they’d laid on.

But she was still hungry, even hungrier than she’d been before with all those hot coals burning up everything she ate. She wanted to ask for help, but her mouth was so burned that she couldn’t make words anymore. She was too big to fit in anyone’s home. Even the warm forge was gone, gone, gone, leaving her all alone with the cold outside.

She shouted her misery into the sky. She shouted so loud that the iron clouds cracked and the sun shone through. Its warmth touched her face, melted the tears on her cheeks. She looked up into it and its knife-light blinded her. She reached for it, reached and reached, stood on her toes and stretched out her arms and legs and grew taller and taller and taller until her clawed hand finally closed around it and she could pull it down.

The snow all melted. The village all caught fire. All her skin burned off and all her hair burned off and even her name burned off. But that sun was so warm and bright in her hand, and she was so cold and hungry. She opened up her mouth of coal-black teeth and swallowed it whole. Outside, everything turned blacker than the deepest night, but inside her, that sun kept burning. Its juices dripped from her chin and its glow lit up her eyes. The village burned, and the people all ran into the dark, and she chased the bright-spark warmth of their bodies.

That sun was just another hot coal, and the more it burned, the more it wanted to be fed.

They say something still moves in the endless dark. They say she had a name, and a face that was more than ash and furnace-glow. They say she had a mother, and a father (and in some stories, a brother and a sister). They say she has none of that, now.

But she is still hungry.

27 notes

·

View notes

Link

4 notes

·

View notes