Associate Professor in the School of Computer Science, University of Nottingham, UK

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This blog has now moved to Medium

I decided to retire this blog a while back. All new posts will now be on my Medium page:

https://medium.com/@5tuartreeves

1 note

·

View note

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anonymising and subtitling video with VLC and ffmpeg

This post documents a process I have used for ‘anonymising’ video (FSVO ‘anonymous’).

Compatibility things: macOS Sierra, VLC 2.2.6, ffmpeg 3.4 (installed via homebrew, and compiled --with-libass flag)

1. Open your video in VLC.

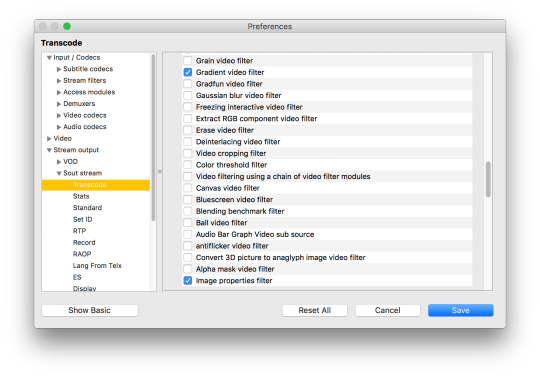

2. In VLC, Preferences menu option, Show All button, then go to Stream Output, Sout Stream, Transcode and select “Gradient video filter” checkbox, “Image properties filter” checkbox, then hit Save.

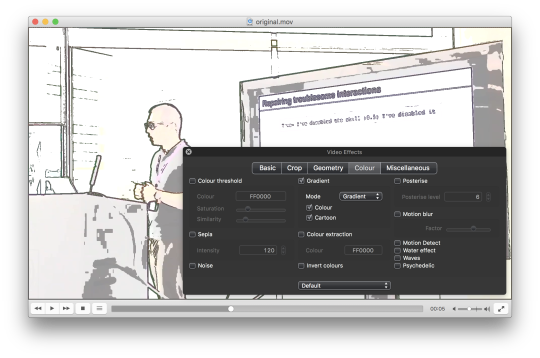

2. In VLC, Window menu option, select Video Effects. Hit the Colour tab, Gradient checkbox, select Mode “Gradient” and some combination of the Colour checkbox and Cartoon checkbox. Hit the Basic tab, Image Adjust checkbox and play with contrast and brightness sliders.

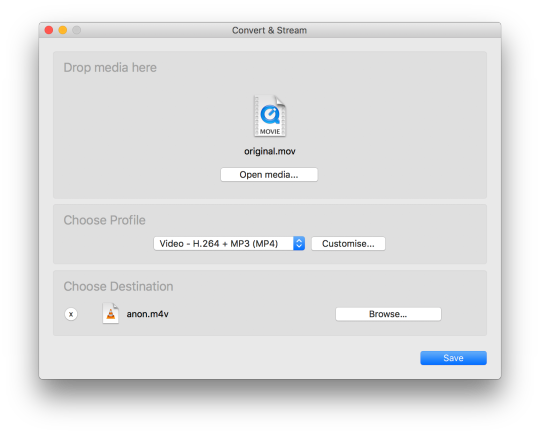

3. In VLC, File menu option, Convert / Stream. Drag the video file onto Open Media (yes, should be unnecessary!). Customise, then ensure “Keep original video track” is unchecked. Save as File (filename I’m using here is “anon.m4v”), then Save... and wait for the anonymised video to transcode to disk.

4a. (I found this step was necessary to ensure the anonymised video played correctly.) Open a terminal window and run

ffmpeg -i anon.m4v anon-fixed.m4v

4b. Alternatively, if you have subtitles to render (I use Aegisub), open a terminal window and run

ffmpeg -i anon.m4v -vf subtitles=subs.ass anon-subs.m4v

Example

Here’s an example, using a video of some fool doing a talk (I fully realise that I am mixing repair with correction in this video, but it was for a non-technical audience).

Before:

vimeo

After:

vimeo

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thoughts on the UK’s Teaching Excellence Framework

On 22nd of June 2017, the UK’s Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) results were released. While this immediately led to celebratory noises from the various ‘winners’, the prominent ‘losers’ tended to call into question the validity of the ranking as unreflective of actual teaching quality. I want to talk about this response and the context that surrounds TEF, and how my own thinking about it (and metrics in general) differs somewhat from this ‘accurate vs. inaccurate�� characterisation of TEF.

Firstly, TEF is of course complex. Wonkhe has a good summary of the TEF mechanism, but I’ll give a short version here. TEF is a UK government-run assessment scheme for rating the ‘quality’ of ‘teaching’ (I use both words advisedly). It requires UK universities submit justifying evidence alongside various metrics (e.g., National Student Survey results, student employment data, etc.). The TEF process then sorts participating universities into ‘Gold’, ‘Silver’ or ‘Bronze’ categories. These categories are then tied to fees that universities may charge students (although this mechanism is not in place yet). TEF is also conceptually connected to the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which is the UK’s national evaluation of research output conducted every 4–5 years (last time 2014). REF, being older, is far more involved than TEF, relying on a significant number of ‘peer review’ panels (using that term advisedly too) to inspect selected research output from all UK institutions in order to then rank them (which is then tied to core funding distribution).

Three points to note first:

1. I don’t think my observations below are particularly original or surprising.

2. I am no expert in politics or the history of government relationship to universities or in university governance.

3. It should go without saying but quite obviously I do indeed think universities should strive to be excellent in teaching. Just not in this way.

Trend and ideology

TEF is the latest way that successive governments in the UK have sought to introduce (or impose, depending on your point of view) market dynamics on the university sector. Broadly this reflects the advance of something that looks a bit like scientific management. I believe TEF is traceable to longer term trends of ‘new public management’ and managerialism that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s to reshape the public sector, particularly through the application of metricisation, performance monitoring, and introduction of competition mechanisms. Even more broadly, if could be said that TEF is reflective of the logic of neoliberalism that has been adopted (or at least tolerated) by all recent UK governments as a model for most shaping sectors of society: i.e., privatisation, financialisation, deregulation, etc. I say this more as a matter of fact than a suggestion of right or wrong. The core question is the relevance of that kind of model to higher education and universities as institutions.

The REF informed TEF; in fact Michael Barber says as much in his recent speech on the Office for Students. But the conditions for TEF’s appearance have been steadily establishing themselves for a long time. The older version of the REF, the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), started in the 1980s as the application of public management ideas gained traction. The introduction of university fees for students at the end of the 1990s accelerated this (it was a solution to widening participation and access). All of these incremental moves lead us towards the reconceptualisation of universities as corporations, students as customers, and the introduction of business processes to university management.

In a way this is key to understanding the logic of TEF and the form it takes, i.e., reliance on metrics. Some kind of metricisation is a key requirement for the introduction of market dynamics in that it provides the ‘signal’ for market mechanisms to operate. (Note that just because the Gold-Silver-Bronze categorisation system is adjectival does not mean it is no longer functioning as a metric.)

As I mentioned, the ideology of TEF seems to be based in the assumption that market dynamics are the way to improve almost anything. Since this is the essential model to be applied to all sectors of life, there clearly can be no suspension for universities.

This leads me to two big questions. Firstly, the sheer complexity and cost of TEF and REF is enormous. The desire is for TEF to become subject specific, thus incurring even more administrative burden. It is interesting to see that a cost-benefit argument is specifically not used with either TEF or REF in order to justify the expenditure. More on that in the next section.

The second big question here is about what I guess you could call the epistemology of TEF’s instigators. It needs examining. Do they believe metricisation throws into the light some hidden naturally occurring order of things embedded into universities but hitherto invisible? Or do they view it metricisation as a mechanic to manipulate and control the university sector? Again, there is very little forthcoming on this, perhaps because even suggesting such questions threatens to shed some light on the central assumptions of TEF.

Given the trends I think it possible (but not necessarily likely) that current and future governments will gradually attempt to move TEF towards an Ofsted-like approach to assessing higher education, i.e., greater oversight, greater powers, involving in-depth inspections (preferably by peers but there a few guarantees), and stronger sanctions. The use of ‘Teaching Excellence’ terminology rather than ‘Student Experience’ implies that indirect measures of teaching quality are only the beginning.

This leads to the following points on language and strategy.

Language and strategy

The language of TEF and indeed REF is positioned in ways that make it seem churlish to oppose. I suspect this is intentional, but I don’t know. The strategic move here has been to align TEF (aspirationally) with teaching rather than ‘reported student experience’ (which would be more accurate). But in line with what I noted above, this is a neat trick since TEF currently only uses indirect measures of teaching in order to map out institutions to the Gold-Silver-Bronze categorisation scheme — in other words there is no direct examination of teaching at all (e.g., via observation).

TEF is thus explicitly affiliated with categories of ‘teaching excellence’ and the rigour-inflected notion of ‘framework’. This means opposition to TEF then tends to affiliate with inversions of those things, because that’s how language generally works. No-one can be reasonably be against ‘teaching excellence’, therefore criticising the very idea of the TEF is met with astonishment (compare this with criticisms that merely seek to tweak its metrics to be ‘more accurate’ or ‘representative’ — i.e., that accept the very idea). To critique TEF in this fundamental way — essentially a critique of ways of knowing, i.e., epistemological — is thus readily taken to be against ‘teaching excellence’ as important (which everyone wants) and therefore ‘you are bad’. It would be good to see the discourse advance a bit here.

Institutionalisation

It also seems that, with the TEF and the REF, there is a gradual process of institutionalisation taking place for academics and those working in universities. Surely we should expect academics, as critically-minded people, to be very careful when engaging in metricisation of, say, natural or social phenomena? (It’s their job!)

It goes like this: At first there is outright skepticism. This then crumbles into skeptical participation (with a nudge and a wink indicating ‘what we all really think about it’). But when the prizes are awarded, the process of acclimatisation is complete, particularly for the winners.

Gold-award institutions in particular come to feel that the metric has been truthful and proven what they already knew: that their teaching is indeed excellent. While schemes as TEF ‘have their teething problems’ for some there no longer is much skepticism about the fundamentals of the exercise. The role of self-congratulation is important here. As Emilie Murphy states “by applauding TEF results we implicitly accept this framework and its methodologies”.

As the acclimatisation proceeds we see an institutionalisation process taking place. Internal, institutional systems are set up to replicate the TEF or REF in order to ensure that in the next round we are favoured / improve / whatever. After this, internal-TEFs or internal-REFs are then connected with performance assessment, progression, and promotion as part of the logic of managerialism. The end result is that externally-specified and mandated metricisation mechanisms come to significantly influence and shape the guts of academic life: how papers are written and published, which research ideas are pursued, how teaching is configured, how students are treated, etc. This is often glossed as ‘game playing’ but this overlooks the wider potentially deleterious effects that happen downstream as a result of that game playing.

Of course, it is unfair to paint this picture of acquiescence without noting that schemes like TEF (eventually) and REF (currently) wield huge sticks in order to get that level of compliance. If it was me in charge I accept I’d probably have to acquiesce too. For TEF the stick is student fee levels, while for REF it is core funding. The stakes are enormous for universities: and you have little choice but to play. Rather than blaming the people involved in the acquiescence or institutionalisation, perhaps it’s more like the frog-in-boiling-water parable.

The really sad thing about TEF and institutionalisation is that universities are already saturated with ways of assessing and improving teaching. Student evaluations of modules, surveys, peer observation and feedback, connecting PGCHE certification to promotion requirements, meetings and workshops on sharing best practice, institutional support (e.g., courses) for developing teaching skills and techniques, etc. There are many obvious ways to improve teaching from a national point of view that don’t involve logic of metricisation. While I’d like to be pleasantly surprised, I do doubt whether the TEF is really going to genuinely enhance teaching.

0 notes

Text

The interactional ‘work’ of video game play

There’s a significant and rich body of research on video games, spanning various disciplines. It addresses a wide range of aspects of video gaming, encompassing studies of video gaming cultures, the economics of video games, player motivations, creativity and video gaming, and many more things besides.

But little of this focusses on the fine-grained ‘details’ of actual play as-it-happens: in other words, the ‘messy stuff’. Some time ago (2007-2009) we sought to remedy this in some small way by taking an ethnomethodological approach to making sense of video gaming practices (“Experts at play: Understanding skilled expertise”).

Since then, more ethnomethodological and conversation analytic (EMCA) work has been done on video games. Our paper, “Video Gaming as Practical Accomplishment: Ethnomethodology, Conversation Analysis and Play” (published in Topics in Cognitive Science) attempts to bring together this literature. It also seeks to do some interdisciplinary work by introducing EMCA studies of video game play to a cognitive science audience, which has, historically, often been interested in the study of games as an approach to understanding cognition (e.g., chess, which also illustrates the overlapped concern with AI).

In our paper (PDF here) we look at a number of things:

- We present a short history of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis and (video) gaming, and a primer / intro to EMCA from this perspective.

- We present a practical ‘tutorial’ of sorts, in order to introduce EMCA studies of video games. To do this we use a series of fragments of (video) data drawn from different EMCA studies of gaming, we look at how gaming ‘gets done’ in public internet cafes, in the home, and online. By gradually ‘zooming’ into these settings we try to cover both the stuff that happens ‘around’ video gaming and what happens on screen too.

- We discuss a few analytic challenges to looking at video gaming in this way, and some ideas for future work.

0 notes

Text

Nine questions for HCI researchers in the making

My colleagues Susanne Bødker, Kasper Hornbæk, Antti Oulasvirta, and I together have penned a short article that asks nine reflective questions about the practice of HCI research. We think they will be particularly useful for HCI researchers who are new to the game. But they are also the kind of questions we think more experienced HCI researchers could be asking ourselves. In that sense they are thinking tools.

Here are the questions:

If you could address just one problem in 10 years, what would it be?

Are you using your unique situation and resources to the fullest?

What’s your HCI research genre?

In one sentence, what is the contribution of your research?

Is your approach right for your research topic?

Why is your research interesting?

Can you fail in trying to answer the research problem?

Will your work open new possibilities of research?

Why do you build/prototype?

And here are the answers: Nine Questions for HCI Researchers in the Making (ACM Interactions, Jul-Aug 2016).

0 notes

Text

Is interface design ‘just’ a search problem?

“Can you come up with a (concrete) design problem in interface design that can NOT be formulated as a search problem?”

This was a question posed to me recently by Antti Oulasvirta. It relates to his talk, “Can Computers Design?”, which he gave at the IXDA conference Interaction ‘16 (slides).

It’s a discussion that seems to have a long history in HCI. I tried to pick apart a little of it in a recent paper looking at the notion of (scientific) design spaces in HCI research (video).

For now, though, I think there are a number of ways to answer Antti’s question.

One way is a kind of naïve approach. We take the question ‘as read’, at face value, and simply try to answer it.

Answer 1: “NO, all design problems can be formulated as search problems.”

We can pick any bog-standard web design type problem to talk about this. For instance, a simple interface design issue might be the question posed to many designers by their clients of the form “where should I my place call-to-action button on this page to increase my sales?”. (This is, of course, assuming that the way I’m formulating a design problem fits with the sense in which it was meant in the original question! But more about that later.)

For instance, say a company is selling cars or some other high-value and quite configurable product online. They have a purchase page and a “Buy” button, but where do they put the button to maximise their sales? This design problem—the client’s question—can be conceptualised as search quite readily by the designer. Let’s do this. One way is to tackle the problem as a simple computational search matter by generating the space defined by all possible button positions to a certain level of resolution (which could be ‘pixels’). This is following what we might call a ‘zero knowledge’ model. We could make the search more dimensional through considering variables like colour of the button, the layout of other page elements that must move in accordance with our button, etc. We could then apply something like A/B type testing in order to solve this problem—i.e., treat it in a behaviourist manner. Of course this renders the search space absolutely enormous and intractable.

However, the ‘Oulasvirta Alternative’ as I’ll call it (see Antti’s slides) would be a lot more smart than this. Here we could use a more sophisticated approach—drawing on models of human performance, attention and cognition, perception and aesthetics, etc. in order to shape and therefore solve the design space in a quicker way. Along the way we would assist the shaping of the design space by selecting relevant design variables (button and page items positioning, button colour, sizes, alignments, etc.) for particular design objectives of interest that relate to increases in sales (clutter perception, motor performance, visual search performance, colour harmony, etc.). We get a result having traversed the design space and found the optimal location, colour, layout of the page, etc. We could then validate the result online via A/B testing and find we get more sales on average with the design solution we located.

Let’s try the opposite answer now. Answer 2: “YES, there are design problems that cannot be formulated (solved) as search problems.”

But what if the formulation of the design problem as found in the client statement is actually problematic? For instance we might discover this via user research that we perform — hypothetically let’s say it involves showing prospective users a set of button-related prototypes. What we then (hypothetically) find is that, due to cars being high value and highly configurable items, users really want to be personally guided through a purchase via an online chat interface where they can ask critical questions about the purchase as they make it. In this case solving the original design problem statement involves respecifying the design problem entirely. Let’s now say that our solution (based on our — imaginary — research) is to pop up a ‘live chat’ window to start this dialogue with the customer as soon as they reach the purchase page. When we test this we find that the new solution offers a higher sales output compared to the button approach. So, although we might be able to increase sales via the Answer 1 / ‘NO’ approach above and validate this through A/B testing or other appropriate metric, it seems to be a ‘local minimum’.

The solution presented here was not possible to arrive at by formulating the design problem in the way that we did to start with (i.e., “where should I my place call-to-action button on this page to increase my sales?”) because that formulation required a particular and necessarily limiting form of specification with regard to the goal (increasing sales). We did this because we tackled the design problem as something that is not a formally-specifiable search problem—i.e., we folded user testing into the output of our initial prototype. Doing so meant we discovered that the design problem had to be reformulated as a matter of UI element modality rather than button attributes. So we then revise the design problem like this: “what UI element should I employ on this page to increase my sales?”. When we go back to the client with our solution they may or may not be happy with the ‘pivot’ we performed. They might be happy because we decided to read the design problem as one that was focussed on sales as a metric and re-scope the design problem accordingly. Or they might be unhappy because actually the technical limitations of their website architecture renders our solution impossible for some reason (they can only have buttons on this page for instance) and they really were tying the use of a button purposefully to the “increase sales” issue.

In Designerly Ways of Knowing (2007), Nigel Cross argues that design activities involve “abductive” forms of reasoning which, quoting March (in turn quoting Peirce) “merely suggests that something may be” (p. 37). It’s this kind of ‘talk back’ between problem and solution that is highlighted by Cross in a reference to Thomas and Carroll (1979), where he states that “a fundamental aspect [to design] is the nature of the approach taken to problems, rather than the nature of problems themselves”, and then quotes Thomas and Carroll: “Design is a type of problem solving in which the problem solver views the problem or acts as though there is some ill-definedness in the goals, initial conditions or allowable transformations”. Cross then quotes Schön, “[the designer] shapes the situation, in accordance with is initial appreciation of it; the situation ‘talks back’, and he responds to the back talk” (p. 38). It’s this that probably characterises the view of Answer 2 / ‘YES’ best.

Having said all this, I think there are problems with both answers. In both cases we must perform some ‘tricks’ in order to produce the right result. In the Answer 1 / ‘NO’ case we pretend that design problems can be atemporally specified—i.e., that we can formulate the design problem from the initial client’s question in its entirety without any role for any processual, iterative way of reaching design solutions, or taking into account the idea that this might then produce new, hitherto unknown factors that then may lead to design problem reformulation. On the other hand in the Answer 2 / ‘YES’ case we strategically insert some hitherto purposefully ‘hidden’ information (obtained via putting a prototype in front of prospective users—thus generating the information missing from the client’s question). Through this we construct the original design problem specified via the client’s question (“where should I place my…”) as deficient in some way.

Finally we might say that I myself have also performed a ‘trick’ in answering as I have done above because I have excluded the possibility of iteration where it suited me (that’s because I’m a Bad Person).

I think we can also unpack the problems of attempting to provide any kind of answer if we think about and unpack the language of Antti’s original question.

There is a whole set of things going on around the very idea of the formulation of design problems, such as what kind of formulation this might be, what is permissible within formulation activities (its scope) and so on. The formulation I adopted above (“where should I my place call-to-action button on this page to increase my sales?”) constructs the design solution in-and-through the process of formulation. For instance, concurrently with problem formulation we also specify a certain kind of inherent scope to the problem—i.e., an ontology that is concerned with buttons, pages, etc. as entities of the formulation. My ‘trick’ above then traded on exploiting the language problem via certain implied boundaries of design problem scoping (i.e., ruling out the more general notion of “UI elements”).

This reminds me of work on programmable user models, which seemed (to me) to have highlighted this matter in the past. For instance, Butterworth and Blandford (1997) indicate that cataloging “the knowledge necessary for a user to successfully interact with a device [has shown] that design decisions can be sensibly made without the need to actually run the model” (p. 13). In other words, the very work of attempting to formulate a design problem into some kind of formal / technical language itself results in possible design solutions (design decisions) emerging as a matter of that process.

This kind of issue around articulating what we mean when we talk about the formulation of design problems also extends to other concepts in the original question—such as ‘search’ and ‘solution’. What constitutes a ‘solution’ and by what criteria are we deciding that a solution has been reached? Depending upon how we answer this, we may resolve the type / form of ‘search’ that is meant when we say ‘search’ differently. Is the possibility of search dependent upon things that can be formally specifiable in models? Do we mean ‘search’ in a technical computational sense or some vernacular, ordinary sense (e.g., a ‘hunt’, a ‘discovering process’, etc.)? Mixing the two might be problematic, leading to confusions about the claims being made for computational design.

There is also a further question about what design even is and what might ‘count as’ design. Antti asks “can computers design?” but this presupposes particular senses in which we ascribe ‘design’ to certain sorts of activities. By this I mean if we look at how we might use ‘design’ in ordinary language, then ‘design’ is something that we might only properly say that people do (a bit like ‘interaction’). This sense of ‘design’ suggests human intentionality and all the attendant attributes that we might normally see as relevant (and talkable) topics in some way—e.g., that some person is considered legally responsible for a design, that they are socially accountable for it, and that they may be the subject of praise about a design done well. None of these things could properly be said of a ‘machine design’ if there were such a thing. In this ordinary sense of ‘design’ whatever aspects of design practices become automated simply no longer constitute ‘design’ because they are no longer things we would ordinarily say are ‘designed’.

Said in another way, the question might be “can machines support design?” to which the answer would be a strong “yes”.

0 notes

Text

Talking about ‘interaction’

(This piece was originally presented at a Microsoft Research and Mobile Life workshop hosted at MSR Cambridge by the Human Experience & Design group on the 9th of March 2016. The title of the workshop was “HCI after interaction”; it was organised in response to Alex Taylor’s ACM Interactions article “After interaction” and the subsequent discussions that ensued on Alex’s blog here: http://ast.io/back-to-interaction. I have adapted and expanded my talk slightly to work more clearly on this blog.)

Reading Alex Taylor’s ACM Interactions article “After interaction” along with some of the discussions online raised some immediate questions about the very idea of ‘interaction’ for me:

What drives calls to go “beyond interaction”, or consider what might be “after interaction”?

Does ‘interaction’ conceptually no longer articulate the right kinds of ideas when we talk about our (HCI) research?

Does it have enough expressive power for us as HCI researchers?

Do we as a community need a definition of ‘interaction’ to proceed coherently in doing HCI research together in future?

... Or is there just too much baggage to the concept of ‘interaction’ – has it had its day?

The idea of ‘interaction’ is an interesting thing to return to, I believe. But thinking about it made me quite confused. I ended up with a sketch of a discussion about it.

I thought: maybe we should return to ‘first principles’, by which I mean questions like these two: 1. What jobs has ‘interaction’ done for us in our HCI research communities? 2. What might we mean to say when we talk about ‘interaction’?

For nearly 40 years, ‘interaction’ has been used in HCI and beyond as a way of talking about the myriad forms of use that emerge between people and computer systems.

First I’ll recap some of what I think Alex’s “After interaction” article says. Alex argues that ‘interaction’ has often been articulated in HCI in terms of “human-machine interactions”. Alex also argues that ‘interaction’ and its sense has been tied to idea of ‘the interface’ – and this has maybe hindered HCI conceptually. In other words, he says that “interaction hinges on an outmoded notion of technology in use”.

I think Alex’s use of ‘interaction’ itself might be trading on certain ways of working with the word – I found this interesting, particularly, his coupling of ‘interaction’ with ‘discrete’ as in “discrete interaction”. I take this to mean that ‘interaction’ has been lacking the kind of expressive power that might help us talk meaningfully, deeply about the embedded and fluid ways with which we are implicated in (or “entangled” with to use his terminology) technologies in our everyday lives. Alex also ties ‘interaction’ conceptually with the materiality of the user interface, arguing that ‘interaction’ as a concept has led us to “concentrate our attentions on the interface” to the exclusion of other things.

Finally, I noted that the call sent to “HCI after interaction” workshop participants argues that the concept of ‘interaction’ implies a long “assumed binary of ‘user-computer’”. So that’s another way of expressing similar problems with ‘interaction’.

Now, on to the first question where we ask “what jobs ‘interaction’ has done for us” – i.e., as a matter of our discourse, our academic talk, and so on.

Firstly we could say that ‘interaction’ has been and perhaps still is a usefully under-defined concept for HCI.

When we talk about ‘interaction’ in HCI communities we can and do use it to say a great many things – things that may conflict and be incompatible ways of saying ‘interaction’. We can say that someone tapping a touch screen is ‘interacting’, just as we can say that posting on social media is ‘interaction’, just as we can say that someone being tracked by their location is ‘interacting’ with a system, just as we can say ‘interactions’ are taking place with / around / through technologies embedded in the social life of the home, just as we can say someone hiring a Boris Bike is ‘interacting’ with a network of systems and data and other people and – even things like ‘political’ and ‘ethical worlds’.

I think the concept of ‘interaction’ also brokers relationships between a range of diverse research communities which dip into the HCI cauldron at some point or another (to mix some metaphors). For instance, one way of talking about ‘interaction’ in HCI is a kind of software engineering oriented way, which emphasises the parallel workings and misalignments of the user and the machine (makes me think of Suchman’s studies here). The engineering sense of ‘interaction’ is framed in terms of the computer’s technical needs of formatted input, output, events, interrupts, etc. This is a nice point I think Alex makes about Englebart and the Mother of All Demos – talking about ‘interaction’ like this is about bringing the machinic requirements to the foreground.

But, I think there are other disciplinary ways we talk about ‘interaction’ too. For instance, psychologists and sociologists of different flavours and persuasions have added their own alternative and sometimes incommensurate ways of talking about ‘interaction’ in HCI – and of course these then become ways of talking about ‘interaction’ into which technologies become enmeshed when they hit the HCI community. For example we might consider how ‘interaction’ can be a way of speaking of (on the one hand),

1. a model of stimulation and response between people,

which we might contrast with,

2. ‘interaction’ as an interpretive process performed by members of social groupings.

There are of course many more examples like these. The point is that there are many ways of talking about ‘interaction’ which can be ‘at play’ at any time in no distinctly differentiated way when we talk about it in HCI. ‘Interaction’, being a promiscuous concept in this way, is probably both good and bad: it fuels a vibrant HCI community but at the same time can submerge perspectival differences.

Next: the second question, about what we might even mean when we talk about ‘interaction’.

I think we have sometimes forgotten to keep in mind that ‘interaction’ is a metaphor that is doing some potentially interesting but confusing things for us by blurring the social and the technical.

I came to talk about this with Barry while doing empirical work together on how social media use is embedded into everyday life.

My point is that when we say technologies, systems, devices are ‘interactive’, we also must necessarily embed them within mundane social order – i.e., our social interactional world. In other words we leverage ordinary understandings of ‘interaction’ to talk about what people do with computational technologies at the selfsame time as we might ordinarily speak of what people do with one another.

This socio-technical blurring of ‘interaction’ – this drawing of the idea of interaction from our ordinary language – then suggests a relevant family of ‘interaction words’ like ‘response’, ‘react’, ‘alert’, ‘remind’, ‘interrupt’, etc. These are all things we might say machines also do.

But, we have to keep in mind these are ways of talking about machines. And these ways of talking about machines are grounded necessarily in ordinary language. This means that these ways of talking about machines, this family of ‘interaction words’, borrow from the everyday sense.

So, we might ask, what does it mean for a machine, a computer, a program, an app, a system, a bot, an agent, and so on, to ‘respond’? We say these things might ‘respond’ to us but is this a ‘response’ in the social, human interaction sense or some other sense? What does it mean for us to use the metaphor of interaction to talk about and ascribe things like ‘responses’ to technologies – things which ordinarily we might say are things that people do?

At this point we could think about this as a problem of language in use. For instance, I think Ryle talks about something similar when he speaks of philosophical confusions around ‘thinking words’ – so, how we talk about things like our ‘intentions’ or our ‘beliefs’ in ordinary language compared with philosophical programmes to formally locate or define ‘belief’ or ‘intention’. I’m left wondering whether ‘interaction’ and the way we talk about it is part of a wider set of troubles around how we talk about machines in general. Take for instance the idea of calling machines ‘intelligent’ and compare it with how we talk about ‘intelligence’ in an everyday sense. Do we want ‘interaction’ to be usefully ambiguous or will we get caught up, and confused about the difference between the family of ‘interaction words’ in ordinary language and their metaphoric application to things like machines?

Maybe we can try to sort through these language confusions: when we say a system ‘responds’ to us does this leverage the methods of ‘response’ that people employ in everyday social interactions? Are they the same? Are they different and how might they be? Maybe we should try to describe them? It suggests that we could take a closer look again at ‘interaction’ and the very idea. It feels like there is a lot of this ground that has been left unexamined with HCI’s expansion.

In closing, I think there might be value in rediscovering ‘interaction’ as a concept. Perhaps we might be a bit more cognisant of the multiplicity of ways in which ‘interaction’ – perhaps in an often confused way – lets us talk about what is a massively varied phenomenon. In this way I think many of the valid concerns expressed by Alex’s piece can be addressed in an inside-out, ‘interaction’-first way and not necessarily by doing away with it.

0 notes

Text

Work with Mixed Reality Lab! Fully-funded 3-year PhD in Internet of Things + UX design + ubicomp research

We are offering a fully-funded 3-year PhD studentship to investigate the intersection of established industrial User eXperience (UX) and design professions, with the increasing availability of consumer ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT) technologies for the workplace, the home, and beyond. As part of this the PhD will explore the relevance of 20+ years of ubiquitous computing research to this area.

Full details can be found here:

http://www.cs.nott.ac.uk/~str/files/iot-studentship-further-info.pdf

To apply, please use the following jobs website for University of Nottingham:

http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/jobs/currentvacancies/ref/SCI1516

Closing date: 30th June 2016 – Interviews: mid July 2016 – Start date: 1st Oct 2016

1 note

·

View note

Text

Things we learned about social media from recording people’s use of mobile phones

Research on social media is popular. What does not seem to be so popular is finding ways to closely examine people’s actual, real-time use of social media, or in other words, how they use it moment-by-moment. So this is precisely what we did (Barry Brown and myself, with data collection conducted by Moira McGregor and Barry).

But how could you investigate this real-time use of social media as-it-happens? One approach Barry and colleagues employed is to get research participants to screen-capture their smartphone during use while at the same time recording ambient audio via the microphone.

The result is a richly detailed set of data captured from everyday situations where you can see considerable detail of how people interact with their smartphones, browsing Facebook, Twitter or Instagram (to name just three social media systems). Since smartphones are pretty much always with us, you can also hear how participants chat with others as they use their phone. It enabled us to develop a detailed understanding of this interaction, supported by transcription of talk and the visibility of on-screen action.

Here’s a figure from our paper to illustrate:

I’ll return to this example in more detail next. Now, here’s three things we learned from looking at this data.

1. Social media use is expansive.

In the data we often find the use of social media being brought to bear as an interactional resource during the everyday moments. What this means is that social media use itself can move face to face conversations on, such as through jokes or introducing new topics to talk about. What does this look like? Here's a simple example where A and B are chatting about a Facebook post that B has just made. B posts “Whee!” as a status update which A then sees and then transforms into a question for B (“we?”, as illustrated in animated GIFs below!):

B is a bit confused by this:

B is still confused by A’s question, but A persists (“you said WE”); B essentially verbalises his status update with a high-pitched “oh, wheeee!”, producing a groan of acknowledgement from A (“oh my gawd!”):

So what? In essence this suggests an alternative account to the popularly-held view that the use of social media, and smartphones use in general, constitutes a unique distraction from normal 'morally desirable' forms of social interaction (a view espoused by Sherry Turkle). Such a view is simply not borne out in our data.

The above example also illustrates the next point well.

2. Interaction with social media is finely and intricately interwoven with the proceedings of everyday life.

In the previous example, what A posts on Facebook occasions a brief humorous verbal interaction with B. If you look carefully, how B scrolls around his news feed fits in with their conversation. In short, it’s interwoven.

There’s a clearer example we can draw on. Here we join three people (a different A, B and C) while C is browsing Facebook on his smartphone. C is taking part in a conversation with A and B. What we draw attention to is just how finely and sensitively coordinated C’s talk is to this conversation and his use of Facebook.

C is scrolling through photos on Facebook. A and B are having a conversation about science fiction and fantasy books. Just as B finishes talking (“don’t they just have like sci-fi and fantasy books”), C takes advantage of the fact that there is a pause in the photos loading to interject. He breathes in and talks (“there no there’s...”) just as A also starts talking (A: “but- that’s the thing is that...”):

The point here is that C is not just ‘browsing Facebook’ but doing so in a way that is synchronised with the ongoing conversation he seems to be part of. He takes advantage of the slowness of Facebook to jump into the conversation at an opportune moment.

That interweaving takes place in some sense is ‘obvious’, but it actually has really significant implications. It suggests that we must rethink where meaning of social media is ‘located’ when we seek to study its use. Meaning is not necessarily to be found ‘in’ social media at all, but rather in the interactional process of ‘gearing in’ the use of social media with the mundane, deeply practical contingencies of everyday life.

In this way our research suggests that the picture gathered from either large-scale aggregations of social media data or post-hoc interviews of users may be missing something. But more about that later.

3. There’s a great similarity in the methods people use to interact on social media and those we use in everyday verbal talk.

By ‘methods’ we mean the familiar ones we all employ on a daily basis, e.g.: taking turns to speak, repairing one another’s utterances, selecting who to speak next, and employing common patterns of adjacent pairs of things (e.g., question/answer, summons/response, greetings, etc.). These normal methods are ‘tweaked’ to fit the design features of social media. So, for instance, social media users employ the ‘@’ feature to address others, but in ways that are /a bit different/ to how we preface an utterance with someone's name when we select them as the ‘next speaker’. For instance, a lot of ‘@’ use also is used to sort out who is ‘in play’ and whether they are considered to be a relevant ‘next speaker’ at all.

The wider significance of this is that it means a whole gamut of concepts and findings from ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (or ‘EMCA’--which has extensively studied naturally occurring talk) can usefully be applied to help make sense of the complex interactions people perform on social media.

Question 1: But isn’t there lots of social media research already?

But where does this all fit into existing social media research, of which there is plenty?

When we looked at what research was out there on social media, we found that most of it seems to fit into a couple of two overlapping categories. We called these ‘actor-focussed’ and ‘aggregate’ perspectives in our paper:

‘Actor-focussed’ perspectives are mainly about eliciting users’ post-hoc accounts of their behaviour on social media. So, interview studies, surveys (e.g., questionnaires) and so on.

‘Aggregate’ perspectives are probably more popular, and involve scraping data from social media itself. So, Twitter postings, friend network mapping, etc.

Yet productive as these approaches have been, what ends up being absent from them is an examination of how social media concretely features in the mundane ‘everyday world’ of its users; this is the kind of approach we have taken in the points made above.

Our inspiration for this different approach is ethnomethodology and conversation analysis. You can read more about this particular perspective in the paper. Suffice to say here that it relentlessly prioritises close inspection of the details of how human action (e.g, with technology) is organised.

Question 2: Does this kind of research into social media tell you what to design?

The simple answer is no, not directly.

But what we do find is that looking at moment-by-moment use throws into relief some of the design choices that have been made. Take commenting on social media for example. Most systems hide what it is you are typing until you hit ‘post’. This means that there are many ‘conversational’ things that cannot be done, such as someone repairing what you are saying as you say it, or enabling someone else to quickly respond to what you are saying as you say it. In other words, online chat becomes less collaborative and slower.

You can read our CSCW paper here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recording of my talk on “Human-computer interaction as science”

Thanks to Lone Koefoed Hansen, I’m able to post a recording of my talk on “Human-computer interaction as science” that I delivered at the Aarhus Decennial conference (Critical Alternatives 2015).

vimeo

0 notes

Text

New publication: “Human-computer interaction as science”

My paper “Human-computer interaction as science” (PDF) is in the proceedings of Critical Alternatives 2015, which is the 5th Decennial Aarhus Conference.

The paper attempts to unpack the role of ‘science’ in HCI research, both in the discourse / language of HCI and in its practices. In the paper I examine the development of (cognitivist) scientific approaches and the notion of ‘design spaces’ in HCI, tracing this from early work on input devices.

The conclusion I reach is to argue that HCI research should largely stop worrying about ‘science’ and also stop worrying about ‘disciplinarity’. The reason for this is that these have proven to be very troublesome concerns which (I feel) draw attention away from the more important work of determining appropriate rigour in HCI, and engaging rigorously with HCI’s inherent interdisciplinarity. (Also see my Interactions article “Locating the ‘Big Hole’ in HCI”.)

I feel that this paper is still midway through developing and in several places elides important things, misses some historical subtleties or doesn’t offer a clear line of argument---in that sense a work-in-progress. So I welcome any comment, criticism, or suggestion.

0 notes

Photo

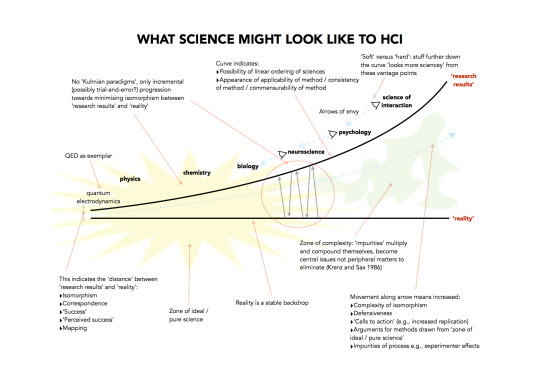

I made this ironic depiction (PDF) of how some in HCI research might view ‘science’, particularly as part of a broader ordering of knowledge. It was initially a reaction, taking the idea of CHI 2014’s ‘Interaction Science’ Spotlight (PDF) quite literally as best I could. This led to some interesting places as I attempted to (temporarily) inhabit that perspective and work out what the world might look like from standpoint of that intellectual place—specifically, for instance, considering how one might view ‘scientific knowledge’ and the corresponding knowledge productions of a ‘science of interaction’.

Personally I’m interested in bracketing this discussion. It is part of a broader set of questions in HCI around disciplinarity and often about a scientific disciplinarity of HCI. I have attempted to do this bracketing and address these issues in some other writings:

Locating the ‘Big Hole’ in HCI Research (ACM Interactions, 2015)

Human-Computer Interaction as Science (Critical Alternatives, 2015)

Is Replication Important for HCI? (RepliCHI Workshop, CHI 2013)

0 notes

Text

New publication: “Locating the ‘Big Hole’ in HCI Research” in ACM Interactions mag

Based on my earlier blog post, ACM Interactions magazine has published “Locating the ‘Big Hole’ in HCI Research” in its July / August 2015 issue.

I’ve made a draft copy of the article available as a PDF.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Four things we found out about live video streaming in public from Blast Theory’s game “I’D HIDE YOU”

With the recent interest in live mobile video streaming services like Periscope and Meerkat, I thought I��d give a brief summary of some relevant findings from our study of Blast Theory’s game I’d Hide You. (Full paper here.)

1. Learning how to simultaneously manage your body and the behaviour of the camera you are broadcasting with is critical to producing ‘good’ video (i.e., interesting, compelling, watchable video). We found a bunch of methods that are used to do this that go beyond standard shot composition and framing etc. (More in the paper...)

2. On the street all actions have a 'double duty' to them. So, pointing the camera at something in the street (a person, an object) is both 'showing' this to the online viewer, and also making that thing interesting to those physically around you. In other words, your video broadcast will always have a dual orientation: to the street and to the online audience.

3. There will be tensions between the demands of the environment you are filming in and making the broadcast interesting for online viewers. And the immediacy of things happening in the street environment will fight with the priority you have for online viewers' attentions.

In I'd Hide You, this is something where the artistic director (and creative design) works with the video broadcasters. It's also important for the artistic director, together with a support team that watches the stream of each broadcaster who is out on the street, to monitor this tension during the performance. This is to make sure that video broadcasters do not get 'too involved' with the street.

4. As with every performance, there is a load of 'backstage work' that is deliberately hidden from view. Video broadcasters in public need to maintain 'backstage zones' that are somehow hidden from the online viewer.

These are not necessarily just physical spaces, but also preparatory procedures (e.g., developing a palette of talkable topics, and establishing locations where it is okay to film). Or they might be about developing 'backstage' methods for doing stuff with people outside (but alongside) the live broadcast stream (e.g., checking it's okay for someone to be filmed by you).

0 notes

Text

Locating “The Big Hole in HCI Research”

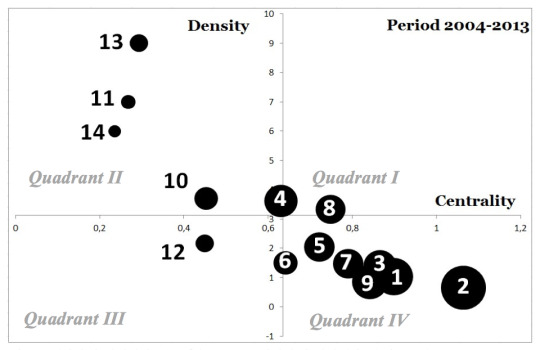

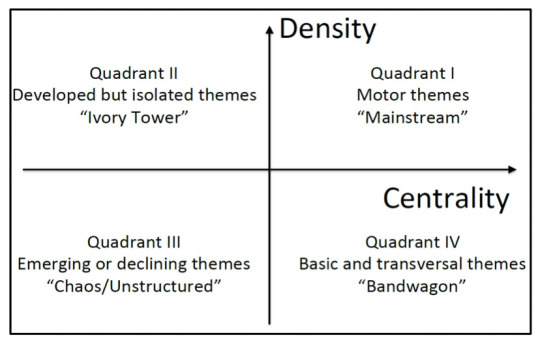

At CHI 2014 a paper was presented (Liu et al., 2014) which sought to demonstrate, through an analysis of keywords specified in a large tranche of CHI papers (from the last 20 years), that HCI research is lacking in “motor themes”. According to the paper, a motor theme is a commonly addressed topic in a given academic discipline that defines the research “mainstream”. Motor themes themselves are in turn made from keyword clusters that emerge during a co-word analysis process performed on the collection of keywords, and are found to have particular values of centrality and density. (Note that co-word analysis was initially popularised by Michel Callon and other STS researchers for the study of scientific disciplines, based upon a conceptual backdrop of actor-network theory.) Keyword clusters would be things like “collaboration” and “handheld devices” amongst many others (see Liu et al. (2014) for the full list), while centrality and density metrics rate “how ‘central’ a theme is to the whole field” and “the internal cohesion of the theme” (Kostakos, 2015).

I attended the conference talk—delivered with panache by Vassilis Kostakos—and the paper received a curiously noisy reception; this was unusual for the normally serene audience at CHI, so I felt it must have touched a nerve for people, resonating with existing concerns some researchers were already occupied by in some way. There were audible gasps when Kostakos produced the punchline of the talk: a graph plotting the apparent absence of keyword clusters in the coveted “Quadrant I”, i.e., the motor theme zone (see image below). This graph was set in opposition to some published co-word analyses of other research areas (e.g., stem cell research, psychology, etc.), which provided more ‘healthy’ plots.

The tenor of the talk and the response it received have to be considered alongside other activities appearing at CHI in recent years—for instance, the "Interaction Science" SIG of 2014 along with the emergence of yearly events at CHI around ‘replication’ from 2011 onwards. It was this chain of events that made me start to wonder whether a somewhat-dormant cultural undercurrent at CHI (and in HCI more broadly) had been surfaced.

Before I continue I should strongly emphasise that it is extremely important Kostakos and others (e.g., Howes et al. (2014), Wilson et al. (2011), etc.) are discussing the ‘state of the field’. We should applaud them for bringing up this difficult conversation when it is far easier to continue with ‘business as usual’ and to shy away from mulling over what can be contentious arguments (which HCI and CHI in particular seems to prefer to avoid—often confusing challenges to research with attacks on researchers). While I have very different views on the topic, the emergence of a debate about the very idea of HCI, what it is and its seeming contradictions, seems like a valuable activity for us and probably long overdue. In many ways this reflects some of the preoccupations of early HCI manifest in the exchanges between Carroll and Campbell (1985), Newell and Card (1985), and others.

What follows below is a list of my objections, highlights of what I perceive as confusions, as well as agreements (in a strange way) with Liu et al.’s paper and Kostakos’s corresponding ACM interactions magazine piece, “The Big Hole in HCI Research” . There comes with this an implication that the discussion is also applicable to the broader cultural movement that I felt it represents in HCI.

Low-hanging fruit: On method

The easiest line of attack in academic work is usually ‘going for the methods’. Often this is a proxy for other problems that a peer reviewer can’t necessarily articulate. It’s also a strategy reviewers may employ when they have fundamental perspectival differences with the approach taken by the authors of the paper but are perhaps unable to step outside their own perspective for a moment (I would be the first to admit having done this in the past). However, in Liu et al.’s paper, understanding problems with method help us unpack what I see as deeper confusions around disciplinarity and the status of HCI in its relation to ‘science’ (which I shall relentlessly retain in quotation marks within this post, sorry!). So this is where I start: at the low-hanging fruit.

In principle co-word analysis (of academic papers) clearly has value in providing surveys of particular attributes of publication corpora. Yet we should also exercise some caution here: the claims made off the back of the co-word analysis must have attention paid to them, and therefore the basis upon which such claims are being made. First we should remind ourselves of these claims. The subsequent summary of the original CHI paper (Kostakos, 2015) states that the co-word analysis “considers the keywords of papers, how keywords appear together on papers, and how these relationships change over time”. Doing a co-word analysis, it is argued, therefore “can map the ‘knowledge’ of a scientific field by considering how concepts are linked”. To clarify, this is indeed a significant claim: firstly that co-word analysis of paper keywords is an adequate method for ‘mapping knowledge’ for a given discipline, and secondly that it can also be used to demonstrate ‘gaps’ in a knowledge space.

My problem with this methodologically is that there is no obvious sense in which co-word analysis of the keywords of papers can provide an adequate overview of “the ‘knowledge’ of a scientific field” (Kostakos, 2015) because it does not follow that keywords are being deployed by authors in order to provide some set of indices to some known-in-common ‘map’ of disciplinary knowledge in the first place. Instead one must subscribe to the idea that authors’ deployments of keywords are driven by some ‘hidden order’ which only becomes visible through the application of the method of co-word analysis. I want to question that claim.

In order to unravel why I might question this, I should explain that I think that some confusions are being made about just what is being ‘done’ in the writing of keywords for academic papers. These confusions touch on more fundamental misunderstandings about language. Firstly we have to consider how keywords are encountered in the situation in which CHI papers are read (i.e., consider the visual practices of paper-reading CHI-formatted research): they are placed on the first page of the paper, they are prominent under the abstract (where we might start reading) and they have their own headed section. (We don’t ‘read’ keywords, we ‘look at them’; I think there is a distinction.) The point is that their visual organisation sets them up to do particular kinds of work for the reader of the paper only as it is read, i.e., they cannot be easily removed from their situational relevance to the surrounding text and the manner by which we as readers encounter them.

For instance, authors may deploy keywords according to myriad of possible reasons, many of which may or may not pertain to some ‘hidden order’—i.e., the ‘knowledge map’ that is discoverable through co-word analysis. Here are some examples. Keywords may get deployed as terms for ACM Digital Library search optimisation. Keywords may be ‘signals’ for allying oneself to some sub-community of researchers or ‘sending a message’ to another. Keywords can be used as discriminators of novelty perhaps via the creation of new terms (and thus claiming prospective research spaces). Keywords can be referents to established corpuses of work, framing judgements on the work through the lens of an an existing tradition in order to tell reviewers that “this is one-of-those-papers, so judge it on those terms”. And, of course still possible, keywords may be indices or intellectual coordinates to some agreed-upon ‘map’ of HCI knowledge (although one might ask by which textbook those coordinates are even constructed). The point is that the practical purposes of keyword deployment get lost in the co-word analysis because all keywords are treated in the same way.

None of the above necessarily diminishes Kostakos’s notion of “The Big Hole in HCI” but it certainly exposes some problematic methods by which the claim is substantiated in the first place. Nevertheless, in order to provide a grounding for such a claim, Liu et al. must also conceptualise HCI as a discipline, which is what I turn to next.

On disciplines and disciplinarity

Both Liu et al.’s CHI paper and Kostakos’s interactions article refer to HCI on a number of occasions as a discipline. The main argument refers to a ‘lifecycle’ for motor themes and their role in disciplines. Disciplinary architecture here is described by various quadrants (see image below), tracking themes as they are born (“Quadrant III: Emerging or declining themes”), begin to stabilise (“Quadrant IV: Basic and transversal themes”), go mainstream (“Quadrant I: Motor themes”) and then die off (back to Quadrant III) or perhaps decline (“Quadrant II: Developed but isolated themes”). Themes may never reach Quadrant I or may go straight to Quadrant II, or perhaps get stuck in Quadrant IV or never make it past Quadrant III. But the basic idea is of the lifecycle and notions of a healthy movement of themes across the graph.

This description, of course, assumes HCI’s classification as a discipline and offers remedial advice for establishing its stability (see the discussion on implications for design below). Largely this assertion passes without comment; in fact this reference to HCI as a discipline is necessary in order to make sure it becomes comparable with other disciplinary objects that Liu et al. hold as reference points based on results of other researchers’ co-word analyses. (The comparison disciplines used in Liu et al. are psychology, consumer behaviour, software engineering and stem cell research.) These reference points can then be used to show the absence of “Quadrant I” keyword clusters in HCI compared to other disciplines and thus the disciplinary deficiencies of HCI.

Even if we take HCI as a discipline, the corresponding implication of Liu et al. that disciplines are somehow ‘comparable’ is itself contentious, I would argue. For instance, it is hard to see how, say, the activities of stem cell researchers have any bearing on the activities of HCI researchers, and it is not clear whether it is reasonable to assume their paper-writing practices, let alone their everyday research work practices, are similar. Or, perhaps, those of psychologists and software engineers. Instead I would suggest that each works with phenomena particular to them, and have methods of reasoning and research practices particular to them. What counts as relevant research questions in one has nothing necessarily to do with what counts in another. Further, it is also unclear with this disciplinary assumption in place why it might be that specialisms like stem cell research should be compared with all of psychology—a broad church to say the least—why not social psychology or cognitive psychology? Instead, co-word analysis may be just analysing how keywords (of whatever extraction method) get used, and it may be just that HCI’s use of keywords is different rather than deficient.

The very idea that HCI is a discipline at all is also itself certainly contentious. I think Yvonne Rogers is correct when she suggests that HCI is an “interdiscipline”. The implication (intended or not by her use of this term, I don’t know) is that in being an interdiscipline, HCI should indeed have “The Big Hole” Kostakos identifies, because the very nature of an interdiscipline would be an absence of a disciplinary core. If there were some essential disciplinary core to HCI it would struggle in its role as broker between disciplines (as pointed out by Alan Blackwell recently (Blackwell, 2015)). Even the earliest moments of HCI commenced as a meeting place between cognitive psychologists, software engineers and, to some extent, designers. In other words ‘we have never have been disciplinary’.

At its most basic the notion of a discipline is an attempt at finding a way of ordering knowledge (Weingart, 2010). It is not a ‘natural fact’ and we cannot treat ‘the discipline’ as transcendent features of a ‘hidden order’. ‘A discipline’ is (I’d argue) an epiphenomenon of the particular community of research practice. And it’s precisely because of this that the arguments made about the application of concepts borrowed from (broad brush) ‘science’ become difficult to handle. Onto which topic I turn next.

Accumulation, replication, generalisation: On ‘science’ and ‘the scientific’ in HCI

One of the key assertions in the interactions article is that “a lack of motor themes should be a very worrying prospect for a scientific community”. Kostakos suggests that remedies should be pursued “[if] we want to claim that CHI is a scientific conference”. I interpret this to mean that HCI has the potential for a scientific disciplinarity that may be established through the development of motor themes. Accordingly, a set of signature scientific procedures or ‘scientific qualities’, as I’ll label them, are described by Kostakos so as to achieve this; these are mentioned as 1. accumulation (science’s work is that of cumulative progress), 2. replication (science’s work gains rigour from replicability), and 3. generalisation (science’s cumulative work involves expansivity). Kostakos describes how “new initiatives have sprung up our field to make it more scientific in the sense of repeating studies, incremental research, and reusable findings”, which I take as reference to the replication (Wilson et al., 2011) and “interaction science” (Howes et al., 2014) agendas I describe above.

Yet making HCI “more scientific” is not really a new drive in HCI. HCI’s initial development was oriented strongly by many self-described scientists (going by Liu et al.’s scheme of labelling sciences) from psychology and cognitive science, both of which have often been at pains to demonstrate their scientific credentials through adherence methods presumed to be drawn from the natural sciences. So one could argue that the cultural foundations for HCI’s desire to be ‘scientific’ have always been present. In addition, attempts to reorder HCI back into accord with the ‘scientific qualities’ outlined by Kostakos have also been suggested before, such as notions from Whittaker et al. (2000) to develop standardised “reference tasks” in order to establish generalisation, and therefore ‘scientific’ legitimacy. These attempts have faltered, however.

The problem, I think, is firstly that can be very problematic to engage in deployments of ‘science’ as a concept. Secondly I think it is mistaken at least to imply (or not guard against an implication even if unintended) that these qualities are properties of ‘science itself’.

On the first point, ‘science’ is a linguistic chimera for HCI because the term is so diversely and nebulously applied, not only in Liu et al. and by Kostakos, but also in discourse within HCI more broadly. It is unhelpful for us because ‘science’ is often used to do very different things that we may well wish to avoid. For instance, this may be in establishing a kind of epistemic and / or moral authority, or an attempt to gain peer esteem for a research community in poor academic standing, or internally as a method for legitimising certain kinds of work and delegitimising others’ (i.e., categorisation between ‘science’ and ‘not science’) in the course of cultural wars. ‘Science’ then becomes problematic because such (rhetorical) uses can tend to be deployed in place of adequate assessments of research rigour on its own terms (what ‘own terms’ might mean is explored below).

This leads to my second point, the idea of the accumulation, replication and generalisation of findings as being intrinsic properties of ‘science’ rather than methodical practices conducted by a community of researchers (see Crabtree et al. (2013) and also Rooksby (2014) on this point). This latter view suggests that the standards of ‘what counts’ as a generalisation, ‘what is’ a relevant process of accumulation (which I take as the establishing within researchers’ discourse of particular motor themes), and ‘what motivates’ the conduct of replications, should be decided upon as a matter of agreement between researchers. It cannot be determined through adherence to an external and nebulous set of ‘scientific standards’ that are adopted from a notion of ‘science in general’ (e.g., what we might call ‘textbook’ understandings developed from formal descriptions of the natural sciences)—for no such thing really exists. Instead, if by ‘science’ we mean ‘demonstrating a rigour agreed upon by practitioners of the relevant and particular genre of reasoning the work pertains to’ then I might consider it a useful term. But it seems unlikely this is what is being meant (it’s definitely very unwieldy!).

This all said, I have a great deal of sympathy for the desire of Liu et al., Kostakos, Wilson et al., Howes et al., and others who seek to increase the rigour of the HCI community—such a motivation for the critique can only be encouraged. Yet, to reiterate, this cannot come at the expense of specifying singular-yet-nebulous approaches like making HCI ‘more scientific’, particularly when the model of ‘more scientific’ is based on classic tropes of what a mythical ‘science’ is said to be, rather than as a matter of how researchers engage in the various shared practices to establish agreement and disagreement over findings.

Instead, I think if we take the ‘interdiscipline’ challenge seriously we should be looking for two things of particular HCI contributions. Firstly, we should expect a rigour commensurate with the research’s own disciplinary wellsprings, whether this is (cognitive, social, etc.) psychology, anthropology, software engineering or, more recently, the designerly disciplines. Rare examples of such ‘internal rigour’ being taken to task is found in the ‘damaged merchandise’ (Gray and Salzman, 1998), ‘usability evaluation considered harmful’ (Greenberg and Buxton, 2008) or ‘ethnography considered harmful’ (Crabtree et al., 2009) debates (although in HCI they feel like more like ‘scandals’—which perhaps says something about the level of debate in HCI more than anything else). What this means is that the adoption of materials, approaches, perspectives, etc. from disciplines ‘external’ to HCI (and remember in this view, there is only ‘the external’) should not result in lax implementations of such imported concepts, approaches, etc. within the HCI community. The ‘magpie-ism’ of HCI research is a double-edged sword: increasing vigour and research creativity, yet often resulting in violence being done to the origins of imported approaches, concepts, etc. And without specialist attention, weak strains are sustained / incubated within HCI; the controversies outlined above are manifestations of this problem. Secondly, we should expect a rigour in the HCI research contribution’s engagement with the notion of being an ‘interdiscipline’. This is what ‘implications for design’ is all about (albeit quite a deficient form as pointed out by Kostakos and others); that is, an attempt to meet others at the interface of disciplines. But more on this next.

The curse of the interdiscipline: Implications for design

The interactions article builds upon Liu et al. by arguing that “the reason our discipline lacks mainstream themes, overarching or competing theories, and accumulated knowledge is the culprit known as implications for design”. The absence of HCI’s engagement with proper ‘scientific qualities’ like generalisation and accumulation is thus pinned to the perceived need to write “implications for design” sections in CHI papers in order to get them past peer review even when the rest of a paper is presenting a high quality of research work. Moreover, within the interdisciplinary community of HCI, it really can never be enough, as Kostakos rightly points out, just to vaguely target ‘relevant practitioners’.

While I have sympathy for this argument, I also think a reassessment has to be made as to why the ‘implications for design’ discussion has emerged in the first place, which I have hinted at above. We can use similar questions to those posed over keywords: what is ‘being done’ in the writing of ‘implications for design’? (Helpfully, Sas et al. (2014) have recently published a categorisation of the different kinds of uses ‘implications of design’ is put to.)

I would argue that ‘implications for design’ can be read as a gesture towards being an ‘interdiscipline’. They are typically an effort to answer the question “why should I (the reader) care about this work?”, a question that is in no way unique to HCI. It would be a mistake to assume that we need not be accountable to the ‘interdisciplinary other’ in HCI. And yes, often the gesture is poorly performed and poorly labelled.

Instead we should perhaps start considering ‘implications for HCI’ rather than ‘implications for design’ as a better sign of taking work at the interface of disciplines seriously.

Update (22/04/15)

Erik Stolterman has expressed similar concerns about HCI’s ‘core’, see his blog post.

Jeff Bardzell has responded to this in a blog post, arguing that it may be better to conceptualise HCI as a set of relations (i.e., it has a relational identity) rather than having a core.

References

Blackwell, A. F. (2015). HCI as an inter-discipline. To appear in Proc. CHI 2015 (alt.chi).

Carroll, J. M. and Campbell, R. L. (1986). Softening up Hard Science: reply to Newell and Card. Human–Computer Interaction, 2(3):227-249, Taylor and Francis, 1986.

Crabtree, A., Rodden, T., Tolmie, P., and Button, G. (2009). Ethnography considered harmful. In Proc. CHI 2009.

Crabtree, A., Tolmie, P. and Rouncefield, M. (2013). ‘How many bloody examples do you want?’ - fieldwork and generalisation. In Proc ECSCW 2013.

Gray, W. D. and Salzman, M. C. (1998). Damaged merchandise? a review of experiments that compare usability evaluation methods. Hum.-Comput. Interact., 13, 3 (September 1998), 203-261.

Greenberg, S. and Buxton, W. (2008). Usability evaluation considered harmful (some of the time). In Proc. CHI 2008.

Howes, A., Cowan, B. R., Payne, S. J., Cairns, P., Janssen, C. P., Cox, A. L., Hornof, A. J., and Pirolli, P. (2014). Interaction Science Spotlight. CHI 2014.

Kostakos, V. (2015). The big hole in HCI research. interactions 22, 2 (February 2015), pp. 48-51.

Liu, Y., Goncalves, J., Ferreira, D., Xiao, B., et al. (2014). CHI 1994–2013: Mapping two decades of intellectual progress through co-word analysis. In Proc. CHI 2014.

Newell, A. and Card, S. K. (1985). The prospects for psychological science in human-computer interaction. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1, 3 (September 1985), pp. 209-242.

Rogers, Y. (2012). HCI Theory: Classical, Modern, and Contemporary. Morgan & Claypool, May 2012.

Rooksby, J. (2014). Can Plans and Situated Actions Be Replicated? In Proc. CSCW 2014.

Sas, C., Whittaker, S., Dow, S., Forlizzi, J., and Zimmerman, J. (2014). Generating implications for design through design research. In Proc. CHI 2014.

Weingart, P. (2010). A short history of knowledge formations. In Thompson, J. Klein and Mitcham, C. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity. OUP Oxford, pp. 3-14.

Whittaker, S., Terveen, L., and Nardi, B. A. (2000). Let’s stop pushing the envelope and start addressing it: a reference task agenda for HCI. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 15, 2 (September 2000), pp. 75-106.

Wilson, M. L., Mackay, W. E., Chi, E. H., Bernstein, M. S., Russell, D., Thimbleby, H. W. (2011). RepliCHI—CHI should be replicating and validating results more: discuss. CHI Extended Abstracts 2011: pp. 463-466.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Implications of the UX-HCI survey: Some clarifications for HCI academics

Having seen some academic responses to the UX-HCI survey I performed, I thought a number of clarifications might help to unpack the assumptions and purposes of the survey that I had while constructing it, or have realised afterwards.

Doing a survey as a reflective tool

My research practices don't involve doing surveys. Surveys are one of the most abused research instruments; they entail an enormous range of dangers. As such, I'm not really interested in the survey-as-a-survey for the purposes of traditional modes of 'data collection'. For me the purpose of the UX-HCI survey was about making some attempt at an initial engagement with UX professionals (via social media, etc.) in ways that were very low cost.

The way the survey was written was naturally oriented towards what I thought their attitudes might be. Of course, the survey is read by some in UX professionals terms of a set of easily-discerned 'academic' attitudes: that it would produce such a response is useful for reflecting upon how I oriented to 'what UX professionals are like'.

The survey necessarily glosses lots of pertinent issues: What is a 'practitioner'? What 'counts' as 'academic'? The survey necessarily sets up a particular and very much assumed relationship between the nature of academic work and the work of professionals. It also pragmatically creates a division between these worlds.

Hence, the work of setting up a survey and conducting it therefore becomes a revealing activity in and of itself: its work is about making things practically visible for us as academics (particularly in deconstructing my own ignorance). This practical 'visibility' is achieved (for me) through doing the 'routine' work of survey construction and administration. By reflecting on this I can then better understand what the various glosses, assumptions and elisons might even be.

At the same time, academics HCI researchers themselves responding to the survey and its provocations also make certain topics about this area visible for me. These might be reflections on how HCI itself has been configured (e.g., with its promises to practice and practitioners), or how HCI researchers themselves conceptualise their work's relationship to the Fellowship's topics (e.g., being challenged by it or defining their work as 'doing something else').

Why assume academia should serve industry?

It is interesting and notable that the very idea of investigating relations between UX (and allied practices) and HCI would suggest to some a position of instrumental reasoning being applied to that relationship. In other words, the idea of the survey can provoke the question: Why assume academia should serve industry?

The answer to this is that this is about taking HCI rhetoric at its word. Personally I'm not really interested in the 'should' of the question; I'm more interested in how HCI has already been configured. At the moment it seems that there is a lot of talk at academic HCI venues like CHI around 'the practitioners' and offering things for them. 'The practitioners' as they are conceived are a bit like 'the users' of times before HCI existed: they are present in our discussions but we don't give weight to considering the relevance of their perspectives. Thus the obvious investigation to do is start filling out that picture of 'the practitioners' with real people and real practices. We might find that actually 'the practitioners' as we mythologise them are not the people HCI is actually interested in serving and uncover very good reasons why not (and therefore what HCI 'should' be doing). Or we might find we are indeed 'serving' them but in ways we didn't understand. And so on...

0 notes