Text

RPG Magazine was one of several tabletop-focused monthlies launched at the height of Japan's RPG boom. Like most of its contemporaries, it acted as a sort of house organ for its publisher's product lines - in this case Hobby Japan, which had amassed a respectable portfolio of translated and original games by the time the magazine began hitting store shelves in 1990.

Originally spun out of the venerable wargaming publication Tactics, RPG ultimately soldiered on for nine years and 112 issues, making it the longest-lasting of Japan's original crop of tabletop magazines. That said, actual roleplaying coverage became steadily scarcer in later years as more and more pagecount was gobbled up by Hobby Japan's main cash cow: Magic: The Gathering. When the magazine finally shut down in July 1999, it was replaced with the purely CCG-focused Game Gather (ゲームぎゃざ).

Content-wise, RPG didn't stray too far from other publications of its ilk, consisting of a smattering of scenarios, session transcripts, how-to guides, and reader participation games. The magazine also featured the fantasy manga Ruin Explorers (秘境探検 ファム&イーリー RUIN・EXPLORER), which would eventually spawn its own roleplaying game and anime adaptation.

[IMAGES: Mandarake]

0 notes

Text

DIGRESSIONS: Of Elves and Ears

Originally conceived of as a way to introduce Dungeons & Dragons to computer gamers, the Record of Lodoss War franchise casts a reasonably long shadow over Japanese pop culture: it helped bring fantasy fiction in the mainstream, played a major role in popularizing Japan's now-ubiquitous "light novel" format, and turned a not-insignificant number of newcomers onto the wonders of roleplaying. In doing so, it also defined the aesthetic of Japanese Elves for an entire generation: the distinctive "bamboo ears" of its main heroine, Deedlit, have been copied countless times over, and still endure across a wide array of anime, manga, and game properties.

Almost 40 years later, “bamboo ears” are still a staple of Elven characters in Japanese media.

As it turns out, though, this particular flourish was mostly just a happy accident. When the first Lodoss campaign was serialized in Comptiq magazine, it was accompanied by illustrations from Yutaka Izubuchi (出渕 裕), an anime and manga artist who would later contribute mechanical design work to franchises like Gundam, Macross, and Mobile Police Patlabor. As the story goes, when Izubuchi got his spec for Deedlit, he was informed that the character sported "long, pointed ears," but didn't receive any visual references to work off of. Apparently unfamiliar with classic depictions of Elves, Izubuchi instead used one of his own favorites as inspiration, modelling Deedlit's most defining feature after the Gelfling characters from Jim Henson's 1982 movie The Dark Crystal.

Viewed side by side, the Henson influence is more than obvious.

The rest, as they say, is history.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Buy Japanese RPGs

A major goal of this blog is to pass on my own enthusiasm for the Japanese tabletop scene - and by doing so, encourage other folks to take the plunge and buy some of these games for themselves. Which of course begs the question: how exactly do you do that?

WHERE TO BUY

If you’re genuinely interested in getting your hands on Japanese roleplaying games, there’s a variety of online retailers to choose from. Be aware that not all of these sites have English-language navigation available, so you may want to make sure your browser has a translation extension set up before you dive in.

For Mainstream RPGs

Yellow Submarine, the iconic Japanese hobby store chain, maintains an online storefront for various analog gaming goods, including RPGs, accessories, and magazines.

The online shopping portal Rakuten includes a bevy of retailers that sell new and second-hand RPG products. That said, due to the large number of stores involved, browsing the listings can be a slog at times.

Mandarake is another expansive retailer, and has the added advantage of offering international shipping out of the box.

Like Mandarake, Amazon will ship internationally, though books here tend to sell at a bit of a premium compared to other retailers.

For Indie RPGs

Conos is probably the best-known independent RPG retailer in Japan, and stocks an impressive selection of both mainstream and doujin RPG products. Their site is generally easy to navigate, and purchases earn you points that you can redeem for discounts on future orders.

Cokage has a similarly broad selection, though site design is a bit on the clunky side and their stock tends to consist of older releases. However, they may have games in stock that Conos has sold through and vice versa, so if you’re looking for a particular title, it’s worth checking both.

Unlke Conos and Cokage, Melon Books is more of a general indie storefront, but their TRPG section contains some interesting odds and ends.

For Older Games

Trader’s Guild is dedicated to out-of-print RPG products and gamebooks. Stock rotates frequently and often sells at a premium, but outside of auction sites, this is one of the few places you’re going to find vintage titles.

Mandarake carries an eclectic selection of older titles, including magazines. As with Trader’s Guild, it’s a bit of a crap shoot as to what will be in stock at any given time, but you might find a few surprises lurking in there.

For Digital Games

Booth is a digital publishing storefront operated by popular Japanese art portal Pixiv, and actively used by indie circles of all sizes to sell their wares.

DLSite has seen more of a push from the Japanese RPG community in recent years, though its roleplaying content tends to get buried under a mountain of borderline-racy ASMR downloads.

Book Walker is best known for its manga and light novel downloads, but the Japanese storefront sells various RPG rulebooks, supplements, and tie-ins.

Conos, Cokage, and Amazon all offer RPG e-books.

GETTING IT TO YOU

You’ll quickly notice that many of these retailers, especially smaller ones, won’t deliver to addresses outside of Japan. The easiest way around this is to take advantage of so-called forwarding services, which provide you with a Japanese mailing address for orders and then ship your purchases onto you for an additional fee.

The majority of my own shipping is done through Tenso, and after three years I’ve yet to run into any major issues with them. While you do end up paying extra for handling and shipping can get spendy depending on the weight of the final package, it’s a blessedly hassle-free way to get games from A to B.

Rakuten Global Express offers a similar service that integrates with your Rakuten account, which may be convenient if you do a lot of shopping through there. It can also be used with non-Rakuten stores and is effectively identical to Tenso in scope. In my limited experience, they tended to push faster and more expensive shipping, but your mileage may vary.

--

Did I miss a site or service? Feel free to drop a comment accordingly. Otherwise, happy shopping!

1 note

·

View note

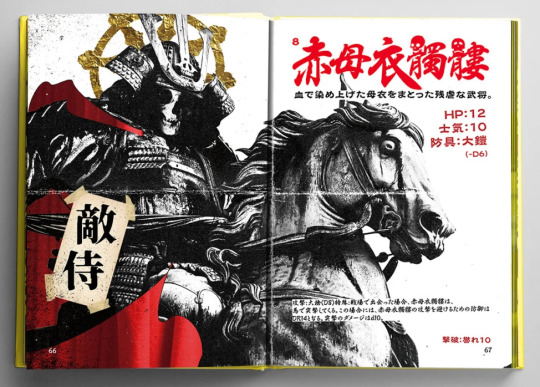

Photo

Crash World (墜落世界) seems to be one of Japan’s more sought-after indie RPG releases, as used copies of the game’s revised edition can command prices in excess of US$700. This idiosyncratic sci-fi title casts players as a crew of debt-crippled post-human weirdos on a distant, aggressively inhospitable planet where starships crash on a daily basis. Salvaging these wrecks is the only real option for ekeing out a living here - but doing so also means braving radiation, poison, various flavors of outlaw, and of course the downed ship’s remaining defenses and thoroughly insane surviving crew.

In keeping with its bleak setting, Crash World’s rules emphasize a high degree of lethality and unpredictability: PC groups who venture out have a 1-in-12 chance of being instantly annihilated by a falling spacecraft, and must survive a variety of other encounters and calamities before they can even set a single foot in the wreckage.

The game initially popped up as a modest black-and-white book in December of 2002 before getting a more elaborate edition a year later. A supplement, Frontal Crash (正面衝突) was released in 2004, followed by a wrestling mini-game set in the same world, Skull Crush (頭蓋粉砕).

Crash World’s designer, Takayoshi Saito (齋藤高吉), later joined Adventure Planning Service, where he contributed to the fourth edition of Satasupe and authored several successful - and comparably lethal - RPGs for the Saikoro Fiction line. Illustrator Toru Yoshii (吉井徹), whose distinctive artwork goes a long way to selling the appeals of the off-beat setting, also still pops up in game-related products from time to time.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Gamers of a certain vintage may have fond memories of Beam Software’s 1993 version of Shadowrun on the SNES, or to a lesser extent, the 1994 Sega Genesis/Mega Drive game created by BlueSky Software.

Significantly fewer are likely to remember Shadowrun’s Japanese Sega CD adaptation from 1996, which not only was one of the last games launched on Sega’s failed add-on, but has never seen a full translation - official or otherwise - into English.

Unlike the more action-oriented SNES and Genesis versions, Shadowrun on Sega CD sticks fairly close to its source material, going as far as to incorporate actual dice rolls into combat. That fidelity can be chalked up to the involvement of Group SNE, who at that point were managing the Shadowrun franchise in Japan. The game’s scenario, co-written by Group SNE member Akira Egawa (江川晃), takes place in Tokyo and follows the cast of Egawa’s Shadowrun replays The Fallen Magician and The Nightmare Mark as they make their way through a series of episodic adventures.

The game’s cast represents a broad cross-section of Shadowrun archetypes. From left to right: Decker D-Head, Former Company Man Shiun, Street Samurai Rokudo, Physical Adept Sha, and Shaman Mao.

Setting-wise, this title draws from Egawa's somewhat controversial Tokyo Sourcebook supplement, a Japan-exclusive release that liberally rewrites the Shadowrun setting to make it more palatable to a Japanese audience. In Shadowrun’s early editions, the Japanese Imperial State (JIS) was presented as a militant, xenophobic superpower that eventually winds up invading and occupying San Francisco. Egawa’s Tokyo Sourcebook replaces this with a dysfunctional nation in the process of being torn apart by open warfare between rival megacorporations - a tweak that apparently didn’t impress hardcore Japanese fans, as several of them went on to write up an alternate JIS sourcebook, arguing that a villainous Japan was ultimately more interesting than a weak one.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

As previously noted, unofficial Call of Cthulhu supplements and adventures have been a major force in the Japanese RPG market for over a decade - major enough, in fact, that Japan’s tabletop publishers ultimately wound up going against the country’s notoriously laissez-faire attitude towards unlicensed fanworks by instituting guidelines and royalty requirements for these types of products.

While some fan-made books do stick to the brooding, eldritch tone Western gamers have come to associate with the brand, there’s just as many using CoC as a jump-off for their own particular vsions - horrific or otherwise. That anything-goes ethos is reflected in this collection of covers, which underlines just how far Japanese fans have run with Chaosium’s ruleset over the years.

--

From top to bottom:

Goddess Kafka

Colorful Toy Box

Never Laugh... Cthulhu Mythos 24 Hours Series Part 3

Explorer’s Destruction Plan

Hakkyo Cthulympics

Panic Shuffle Party

Nasobame Paradise

Independence Day

Magic General Store 'Aoitori'

#call of cthulhu#coc#tabletop roleplaying#pen and paper roleplaying#trpg#roleplaying games#rpgs#japan

0 notes

Text

Indie Roleplaying in Japan

Independent RPGs are a vital, vibrant part of the Japan's tabletop scene, both a movement in their own right and a talent incubator for publishers on the prowl for the next big thing. That said, this prominence is a relatively recent shift: during the boom years of Japanese roleplaying, indie titles existed on the margins of the market, produced by die-hards for die-hards. It would take the near-death and resurrection of the tabletop industry - and several decades of persistence - for these creators to finally get their due.

The Fandom Factor

Like most independent RPG scenes, Japan’s indie output is split into original and derivative works. This in itself isn’t especially noteworthy: after all, a good chunk of the global small-press market is dominated by third-party releases for existing systems, ranging from mainstream juggernauts like Dungeons & Dragons to cult faves like Mörk Börg or Mothership.

Such as 2022′s Nobunaga's Black Castle, Japan’s first venture into the realms of black metal fantasy.

What is notewothy is how the Japanese RPG scene has dealt with derivative products - especially the unauthorized ones.

In the West, piggybacking on an established system or property has always been fraught with a certain amount of legal peril. The ‘80s and '90s in particular saw an assortment of dust-ups between big-name publishers like TSR and Palladium Books and smaller creators - particularly fansites - over both actual and imagined IP violations. Things shifted significantly with the introduction of the D&D Open Game License (OGL) in 2000, which allowed third parties to produce D&D-related content without having to pay fees or royalties. However, these products still had to adhere to an explicit set of guidelines - one that could force an incautious company to pulp an entire print run of books.

By contrast, Japan’s rights holders historically didn't fuss much over derivative works, even ones sold for money, unless the infringement was particularly egregious. This resulted in the creation of a massive gray market of for-profit fanworks that has grown to annual sales in the region of US$800M - a not-inconsiderable chunk of Japanese otaku spending. Semi-protected as “parodies” in the eyes of the Japanese law, these products take various popular or nostalgic IPs and spin them off into new directions - respectful, comedic, pornographic, and everything in between.

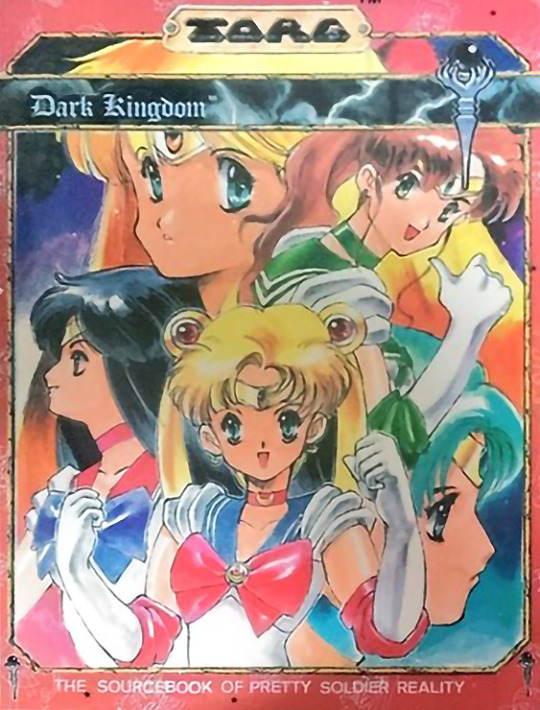

While the overwhelming majority of for-profit fanworks are comics or comic-adjacent material like artbooks, RPGs also carved out a niche in this market through unofficial supplements, adventures, and even entire roleplaying systems. Largely unconstrained by legal worries, Japanese tabletop fans could produce IP-infringing double whammies like 1993′s Dark Kingdom: a thoroughly unlicensed sourcebook that imports the cast of pop culture evergreen Sailor Moon into TORG, West End Games’ RPG of fractured realities.

Dark Kingdom was an early showcase for Jun'ichi Inoue (井上純一), who would later enjoy a fruitful career at FEAR creating notable titles like Tenra Bansho (天羅万象 ) and Alshard (アルシャード). [IMAGE: Dragoon_Shaytan via Twitter]

Over the years, other popular IPs inevitably also got the tabletop treatment, resulting in fan-made adaptations of everything from ’80s anime relic Dream Hunter Rem and classic shoot-’em-up R-Type to contemporary megahits like Fate/stay night and Bleach. Even today, it’s possible for a creator to knock out an RPG based on Dragon Quest - one of Japan’s largest and most prominent roleplaying franchises - and put it on a digital storefront for US$16 without immediate fear of a thermonuclear-level copyright strike.

However, until around 2010, these sorts of derivative works were more of a sideshow than anything else. That changed once Call of Cthulhu established itself as Japan’s best-selling RPG, buoyed by a series of popular - and irreverent - actual play videos and the Mythos-Goes-Harem antics of the Nyaruko: Crawling with Love media franchise. Suddenly, freshly-baked Cthulhu fans were appearing at gaming conventions in increasing numbers, resulting in a corresponding boom in fan-made CoC adventures and supplements.

As Call of Cthulhu grew to dominate the local tabletop industry, its fanworks cast an equally long shadow over the indie scene, eventually accounting for an estimated 80 to 90% of all derivative products on the market. This extreme popularity would have repercussions: in 2021, facing pressure from the game’s creators, Chaosium, CoC licensees Arclight joined forces with Japan’s most prominent RPG companies to create the Small Publisher Limited License (SPLL) program, which set content guidelines and royalty fee requirements for any third party publishing material for an established system. This was an unusual arrangement by Japanese standards, though one that also gave new legitimacy to derivative works within the roleplaying community.

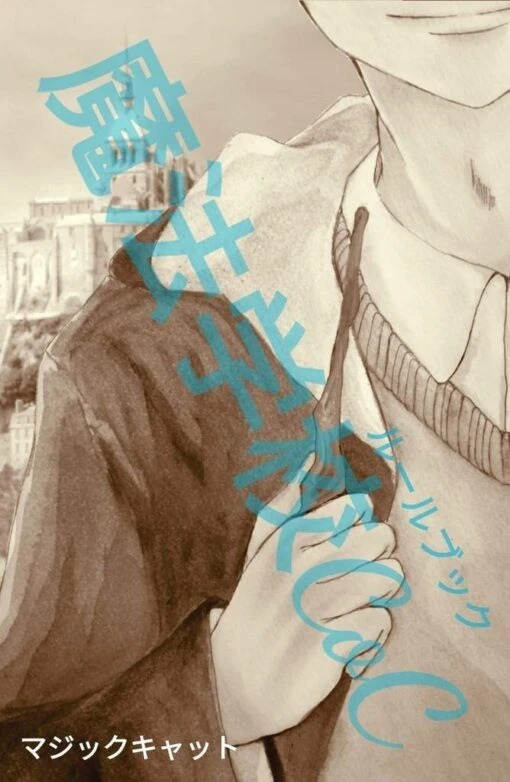

As was the case with D&D, Call of Cthulhu’s rules have been used as a springboard into other game styles and genres. For instance, the Magic Academy CoC (魔法学校CoC) series reworks Chaosium’s system to accommodate Harry Potter-ish adventures.

An Interlude on Doujin Culture

Derivative works are just one facet of Japan’s indie RPGs, but an important one to start with - in large part because the impact of the Japanese fanwork scene extends much further than just Sailor TORG.

Thus far, when I’ve used the word “fanwork,” it’s been to refer to what the Japanese would formally call “doujinshi.” In the West, that term is intimately associated with fan comics, especially pornographic ones, but the word simply refers to any independently created and published print product - more specifically, one put out by a doujin (同人) or “circle” of like-minded individuals.

The doujinshi concept dates back to the 19th century, but only truly gained traction in the 1980s - a point where more affordable, accessible printing options made it possible for enterprising hobbyists to produce and sell comics as a full-on side gig. As the number of indie creators grew, events emerged to give these artists and writers a venue to market their wares - chiefly Comic Market, which began as a modest volunteer-run show in 1975 but would eventually grow into the world’s largest comics event by a significant margin.

As the doujinshi market grew in size and scope, a new generation of printing companies emerged to serve this subculture through cheap, high-quality digital printing and low minimum order quantities. This further reduced barriers to entry, giving even amateur artists access to professionally bound products at an manageable price.

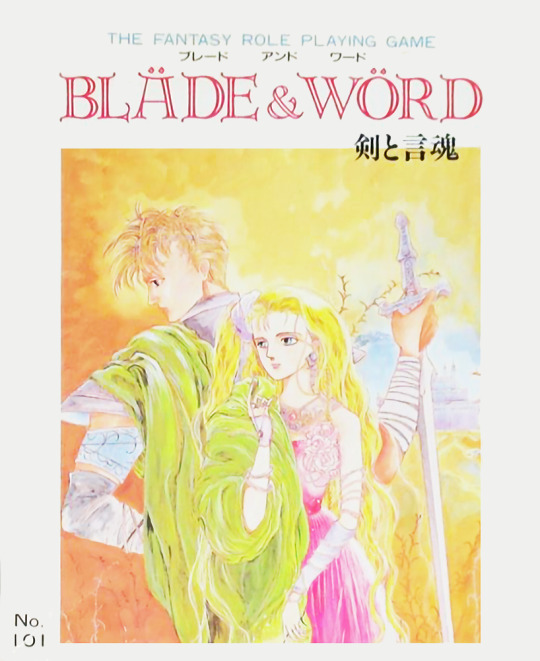

This ecosystem of affordable production and dedicated sales events created a vital foundation for Japan’s indie roleplaying groups - and a sorely needed one, as up until the mid-‘90s, the cost and complication of producing RPG products kept independent releases relatively scarce. As a result, early offerings like Bläde & Wörd (ブレード アンド ワード), ITHA WEN Ua ( イサー・ウェン=アー), and Small Still Voice (スモール・スティル・ボイス) played it safe by skewing toward orthodox Western-style fantasy - and largely sank in the market with scarcely a ripple.

Thanks to its multifaceted magic system, 1991′s Bläde & Wörd enjoyed somewhat more longevity than its fellows, eventually spawning a second edition under the somewhat unlikely title of “Acoustic Leaf“ (ブレード アンド ワード) in 1995.

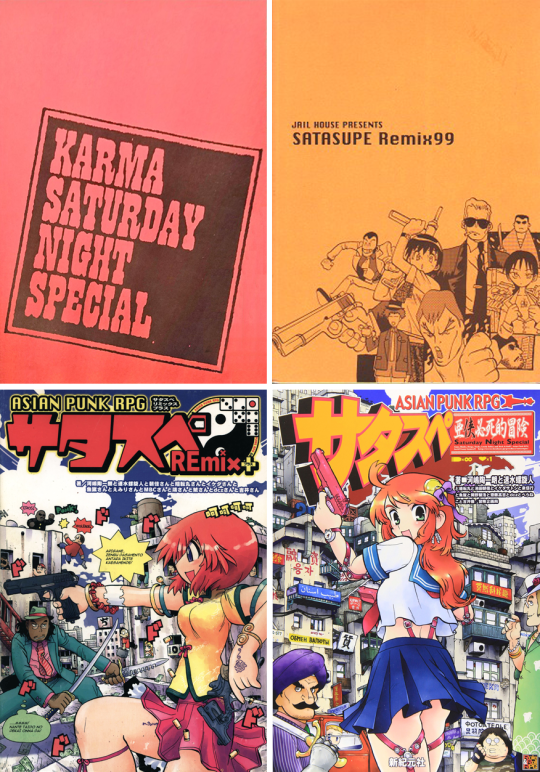

The ability to source cheaper, better-looking books at lower order quantities arguably helped RPG creators shake loose some of this conservatism - perhaps best exemplified by 1996′s Karma Saturday Night Special, later known by the shorter, punchier alias “Satasupe” (サタスペ). Set in an alternate history where the United States did not enter World War II and a nuke-ravaged Japan found itself divvied up by various superpowers, this gangster RPG dunks its players into a gonzo stew of Soviet narcotics farmers, voodoo practitioners, Japanophile mercenaries, biking Crusaders, criminal animal handlers, UFO cultists, and more besides.

Satasupe’s creators, “Jail House,” started off as a loose-knit collective with almost a dozen credited members, building up their audience and reputation over several years before striking paydirt with 1999′s SATASUPE Remix99 (サタスペ・リミックス99). Remix99 would prove popular enough to attract attention from the wider industry, and in 2003, a revised and expanded version called Satasupe REmix+ ( サタスペ・リミックス+) earned a release through Hobby Base, the publishing arm of the game store chain Yellow Submarine.

To clean the game up for its commercial debut, Jail House partnered with Adventure Planning Service, one of Japan’s oldest RPG design companies. The collaboration proved so fruitful that Jail House was effectively absorbed by APS, and Satasupe’s lead designer, Toichiro Kawashima (河嶋陶一朗), would quickly become one of the company’s most important creators, spearheading future hits like Labyrinth Kingdom (迷宮キングダム) and the now-ubiquitous Saikoro Fiction line.

The evolution - and professionalization - of Satasupe’s rulebooks doubles as a mini-history of Japanese indie roleplaying as a whole.

A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats

On the whole, the early 2000s were a transformative time for independent roleplaying. In the West, the third edition of Dungeons & Dragons made its debut alongside the Open Game License, which unleashed a new generation of hobbyists and small publishers eager to capitalize on the excitement generated by D&D’s first major new edition in 11 years. Around the same time, independent RPG creators also began establishing their own distinctive culture and philosophy, driven by influential online discussion forums like The Forge. And behind the scenes, indie creators of all stripes benefitted from the growing availability of sophisticated desktop publishing software, which continuously narrowed the aesthetic quality gap between “amateur” and “professional” games.

In Japan, the OGL attracted significantly less direct interest, though it would eventually inspire comparable “open-source” systems like FEAR’s Standard RPG System (SRS) and Adventure Planning Bureau’s Saikoro Fiction. A more notable development was the introduction of FEAR’s Game Field Awards in 2000, which allowed aspiring designers to submit board, card, and roleplaying games to the company for potential commercial publication. This proved to be an important new outlet for independent creators, and helped birth notable titles like 2005′s TORG-inspired Chaos Flare (異界戦記カオスフレア) and 2001′s Double Cross (ダブルクロス), which is credited with helping to establish the more systematized approach used by modern Japanese RPGs.

2000 also saw the debut of Game Market - or “Gema” for short - a twice-a-year event that positioned itself as a Comic Market equivalent for analog hobbies. Though Gema’s foot traffic was only a fraction of its role model’s, the show would gradually establish itself as a go-to for unveiling new RPGs, especially once stewardship of the event passed to Call of Cthulhu licensee Arclight in 2010.

2010, in fact, seems to be generally regarded as the true starting point for Japan’s modern indie RPG scene - thanks again to the CoC craze, which not only produced a mountain of derivative products, but dramatically changed the size and demographics of Japan’s roleplaying fandom by drawing in both younger gamers and female players. This expanded audience appears to have to encouraged a greater diversity in game design and themes - less anime-inspired power fantasy, more high-concept exercises like “what if the players were actors in a movie production scrambling to finish shooting with no script and no budget before the whole project implodes?”

2012′s Reading! Manga Lord (爆走!まんが道) and 2013′s Idol Box! (どるばこ!) exemplify the indie scene’s broader swing towards less traditional RPG topics after 2010.

Surprisingly, some of this mindset even spilled over to Japan’s two biggest RPG publishers, Kadokawa and Shinkigensha - as evidenced by the fact that Satasupe received a mass-market release through the latter in 2008, eventually followed by other oddballs like the youth band RPG Strato Shout (ストラトシャウト) and Mofumofu Stream (もふもふストリーム), a game about YouTubers fighting crime with their psychic pets.

A final notable development in the indie scene was the emergence of online storefronts for independent RPG releases. While digital publishing has slowly become more prominent in the Japanese tabletop market, physical copies still dominate the indie space and groups invariably end their events with unsold game stock that needs to be offloaded elsewhere. The launch of Cokage in 2014, followed by Conos in 2016, provided an important outlet for excess copies and doubled as a means of making small-press games accessible to fans in rural areas who wouldn’t normally be able to attend a sales event.

Notable Creators

There’s an enormous quantity of indie circles currently active in the tabletop space, with more joining the fray on a monthly basis. A comprehensive list of every group is a bit beyond the scope of this post, but let’s take a quick look at a few of the longer-running ones:

Draconian: Originally a partnership between system designer Fuyu Takisato (瀧里フユ) and worldbuilder Shio Botan (潮牡丹, AKA Darya Tide), Draconian began publishing in 2014, gradually taking on more members to become a five-person operation capable of releasing multiple games per year. In 2018, the group officially crossed over into mainstream publishing with Silver Sword: Stellar Knights (銀剣のステラナイツ), a two-player RPG distributed by Kadokawa. Since then, the circle has put out several more titles through both Kadokawa and Shinkigensha while continuing to self-publish its more experimental work.

Draconian’s titles tend to focus on questions of identity, reality, and relationships with others, typically in fantastical or post-apocalyptic settings. Its more combat-intensive games share a battle system known as Diaclock, which was made openly available for use by other creators in 2020.

youtube

In recent years, Kadokawa have begun experimenting with promotional trailers for their RPG releases - in this case for Stellar Knights.

Phantasm Space: Founded in 2014, Phantasm Space is responsible for the steampunk aerial exploration game Skynauts (歯車の塔の探空士<スカイノーツ>), the Porco Rosso-inspired Il Paradiso Celeste dei Cacciatori Extro (チェレステ色のパラディーゾ), pastoral fantasy title Floria: The Verdant Way (翠緑のフローリア), and the comedic Villain’s Quest (ヴィランズクエスト). All four games have a lighter tone and showcase unusual ideas and mechanics; Villain’s Quest, for instance, throws its anti-heroes into pitched strategy meetings where participants use cards to advance various proposals; eventually, things climax in an analog tower defense game as the players scramble to protect their evil master from being slain once more.

The circle’s leader, Lord Phantasm, went pro in 2020 by joining Adventure Planning Service under the pen name Eisuke Nanashi (中西詠介). In 2021, Nanashi and APS published a revised version of Skynauts through Kadokawa. That same year, Floria also received an English-language translation courtesy of Silver Vine Publishing.

youtube

Another Kadokawa trailer, this time for the 2021 edition of Skynauts.

Rommel Games: Though Rommel Games began publishing RPGs in 2013, the group’s big breakthrough would come the following year with Galaco and the Tower of the Broken World (ガラコと破界の塔), a mecha dungeon crawler set on a distant planet. The game’s slick, commercial-level production values made an immediate splash in the RPG scene, and a number of indie creators readily credit Galaco as an influence on their own work.

In 2017, Kadokawa picked up the circle’s fast-paced superhero title Deadline Heroes (デッドラインヒーローズ), which was followed by a villain-focused version entitled Black Jacket (ブラックジャケット) in 2019. The line’s success may be attributed in part to the buzzy My Hero Academia franchise, which made its anime debut in 2016 and continues to enjoy a dedicated following in Japan.

--

New Game Plus: This collective of young game designers has maintained a healthy and eclectic output since first appearing on the scene in 2018, with titles that include Night Butterfly ( ナイトバタフライ ), an RPG about male nightclub hosts, and the aforementioned Mofumofu Stream.

Calling NGP an indie circle may be a bit of a stretch - the majority of its titles have in fact been released through Shinkigensha - but the group does put out the occasional doujin game. Sadly, its founder, former Group SNE associate Rikizo (力造), passed away from pancreatic cancer in 2020.

--

Shiawase Training Ground: Formed by systems engineer Go Yamauchi (山内剛), Shiawase Training Ground has been actively releasing material since 2014, producing offbeat titles like the medieval peasant survival sim Hoshikuzu Village Story (ホシクズ村々物語) and restaurant-focused A La Cuisine (アーレ・キュイジーヌ). Yamauchi’s upcoming “travel and escape” RPG We Will Happiness! (ウィーウィル・ハピネス!) has reportedly ended up with Adventure Planning Service, suggesting his mainstream breakthrough may be just around the corner.

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

A long-ish playthrough of 1993′s Sword World SFC, a comparatively faithful adaptation of Group SNE’s 1989 fantasy RPG.

Sword World SFC is a cut-down reworking of the previous year’s Sword World PC, which reportedly spent a whopping three years in development and effectively bankrupted its original developer, XTAL SOFT. T&E Soft, creators of the seminal action RPG Hydlide, swooped in at the last minute to rescue the project, and would go on to release Sword World SFC2: Legend of the Ancient Titan in July 1994.

1 note

·

View note

Text

DIGRESSIONS: What's In a Name?

In creating this blog, I've attempted to skew its content towards Western RPG fans, steering away from more specific Japanese terminology in the interests of keeping things accessible. For instance, I use "indie RPG" rather than the more correct "doujin RPG," as the former requires less explanation to a first-time reader.

The biggest of these concessions, though, is the blog's core topic: in Japan, a pen-and-paper RPG isn't an RPG at all, but a TRPG. The "T" in this case is generally accepted to stand not for "Tabletop", but "Table Talk" - where that divergence came from isn't exactly clear, but it's likely a mistranslation that just happened to stick. Game designer Koji Kondo (近藤功司) has taken credit for creating the term and claimed it gained wider adoption after he started using it in the pages of Warlock magazine back in the late ‘80s, where it was promptly picked up by the magazine's supervisor, well-known RPG evangelist Hitoshi Yasuda (安田均).

This begs the obvious question: why the need to coin a separate term in the first place? In the end, it's a matter of timing: in the West, tabletop RPGs predated their electronic counterparts by a number of years, and directly influenced their development. In fact, many early computer RPGs were the direct product of enterprising roleplaying fans trying to translate their hobby into digital format, sometimes literally so; Richard Garriott's Akalabeth, which laid the groundwork for the legendary Ultima series, started off as a project named "D&D".

In Japan, American computer and tabletop RPGs arrived around the same general time, but computer RPGs broke into the mainstream first; by the time the Dungeons & Dragons Red Box made its Japanese-language debut in 1985, dungeon crawlers were already something of a known quantity, and the word "RPG" was more likely to conjure up image of titles like Wizardry or The Black Onyx than visions of hex maps and 20-siders.

Given the subsequent dominance of the RPG genre in Japan's video gaming scene, it's not surprising to note that pen-and-paper roleplaying has never quite managed to reclaim the word even four decades later.

0 notes

Text

Who’s Who In Japanese Roleplaying?

Having now looked at some of the distinguishing characteristics of Japanese tabletop RPGs, let’s dive a bit further into the scene’s movers and shakers.

Since the Japanese roleplaying industry has a fairly clear divide between game developers and game publishers, I’ve decided to look at these separately. There is, of course, another important group in the RPG space not covered here: independent developers, who I’ll be exploring in a later post.

PUBLISHERS

Kadokawa

A true media juggernaut, Kadokawa’s businesses include books, magazines, movies, music, games, and even the popular video-sharing portal Niconico - Japan’s answer to YouTube.

The conglomerate initially entered the roleplaying space in the mid-’80s trying to capitalize on the success of Dungeons & Dragons - first by licensing TSR’s D&D novels and gamebooks, later via pushing RPG coverage into its electronic gaming magazine Comptiq. That gamble paid off when Comptiq’s monthly Dungeons & Dragons campaign, Record of Lodoss War - originally pitched as a way to teach newcomers the basics of D&D - became a breakout transmedia hit.

Over the course of the ‘80s and ‘90s, Kadokawa and its subsidiary Fujimi Shobo published a steady stream of original, licensed, and translated games, often based on Kadokawa’s own IP. Its most ambitious project of the era, MAGIUS, was a beginner-oriented universal RPG supported by 30-odd standalone releases covering franchises from Tenchi Muyo! to Neon Genesis Evangelion. However, the line’s sales fell short of expectations; this, coupled with an overall decline in RPG sales, saw Kadokawa effectively withdraw from the market in the late ‘90s.

After the release of D&D’s Third Edition in 2000, Kadokawa became notably more active in the tabletop space again, both directly and indirectly: in 2004, the conglomerate acquired the parent company of fellow publisher Enterbrain, who had been pushing out notable works like FEAR’s popular Night Wizard and the 6th Edition of Call of Cthulhu. Kadokawa would continue to release dozens of RPGs through Enterbrain and Fujimi Shobo until 2013; following an extensive restructuring, the company’s RPG output is now published directly under the Kadokawa name.

Kadokawa’s clout and aggressive media mix strategy created additional mainstream visibility for RPGs and RPG-adjacent properties like Record of Lodoss War during the hobby’s boom years.

Shinkigensha

The other heavyweight in the industry, Shinkigensha was founded in 1940 but only formally incorporated in 1982. At that time, the company was best known as a publisher of computer guides, but soon diversified into fantasy and military reference books as well a small number of RPG products.

Following the gradual revival of the roleplaying market in the early 2000s, Shinkigensha significantly stepped up its activities in the space, investing in translations of high-profile titles like White Wolf’s New World of Darkness line and the 4th Edition of Shadowrun alongside a variety of homegrown releases. In 2003, Shinkigensha also launched Role & Roll - at that time Japan’s first new roleplaying-focused magazine in almost a decade - in collaboration with gaming company Arclight. “Roll and Roll RPG” would subsequently become the publisher’s dedicated imprint for tabletop releases.

Like Kadokawa, Shinkigensha maintains a sizeable portfolio of original and translated games, the undisputed crown jewel of which is Call of Cthulhu - currently Japan’s most popular RPG by a significant margin. The publisher also has cultivated a fruitful relationship with the developer Adventure Planning Service, whose Saikoro Fiction line has become a staple in Shinkigensha’s Role & Roll RPG output over the past decade.

--

Hobby Japan

Hobby Japan is the epitome of “from humble beginnings.” The company started off as an import shop selling foreign-made die-cast cars, but grew dramatically in the ‘70s and ‘80s by expanding into areas like model kits and wargaming. In 1984, Hobby Japan released Japan’s first translated RPG, Traveller, marking the beginning of a four-decade-long relationship with the roleplaying market.

While the company is probably best known for its localized games, Hobby Japan’s output during the boom era included several notable originals, including Metal Head - Japan’s first cyberpunk RPG - the sci-fantasy mech saga Wares Blade, and the first edition of FEAR’s Tenra Bansho. Hobby Japan’s Tactics magazine - later retooled as RPG Magazine - also served as an important early voice for the industry, creating greater awareness for the hobby among the Japanese public.

Unlike Kadokawa and Shinkigensha, Hobby Japan trades almost exclusively in translated titles these days. For nearly twenty years, they were WotC’s official D&D licensee in Japan, overseeing localization of the game’s Third, Fourth, and Fifth Editions before WotC semi-abruptly revoked their publishing rights in late 2022. The company currently handles the Japanese editions of Cyberpunk RED, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, and the D&D 5E-compatible Sandy Petersen's Cthulhu Mythos.

--

Tsukuda Hobby

An off-shoot of one of Japan’s more notable toy manufacturers, Tsukuda Hobby was also a pivotal force in the embryonic tabletop scene, publishing the country’s first homegrown RPG, Enterprise, its first fantasy RPG, Roads to Lord, and its first generic ruleset, WARPS. Despite this, the company never seemed to achieve the kind of success its competitors saw and left the tabletop market in 1993, ultimately going bust just a decade later.

--

Shinwa

Formerly an importer of American wargames, Shinwa struck it big when it secured the D&D license, but was unable to sustain its momentum once Group SNE’s Sword World entered the market in 1989. After its localization of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Second Edition failed to find an audience, Shinwa abandoned the roleplaying industry, sliding into obscurity and bankruptcy soon after.

Shinwa during its heyday in 1989. [IMAGE: Meyjuka/MESGamer]

DEVELOPERS

Group SNE

Formally incorporated by sci-fi translator turned gaming evangelist Hitoshi Yasuda in 1987, Group SNE could arguably be seen as Japan’s answer to TSR. Thanks to the one-two punch of its phenomenally popular Record of Lodoss War campaign series and the blockbuster RPG it eventually spawned, Sword World, this small company dominated the early years of the roleplaying industry. Beyond its own creations, Group SNE also oversaw the localization of many major Western properties, including Shadowrun, Mechwarrior, GURPS, Tunnels & Trolls, Earthdawn, and the D&D Rules Cyclopedia.

Following the release of Magic: The Gathering, Group SNE pivoted to collectible card games with 1997′s popular Monster Collection, one of the Japan’s first homegrown CCGs. Unfortunately, subsequent titles proved significantly less popular, and by the mid-2000s, the company renewed its focus on the tabletop space with Sword World 2.0 in 2008, which was followed by Sword World 2.5 in 2018.

Group SNE’s more recent output has included localizations of Kenneth Hite’s Trail of Cthulhu and the anthropomorphic fantasy RPG Pugmire, licensed RPGs based on the Dark Souls, Elden Ring, and Goblin Slayer franchises, and a number of original board and card games. The company also produces the quarterly magazine GM Warlock, which covers a variety of analog hobbies.

Key Works: Record of Lodoss War, Sword World, Crystania, Demon Parasite

--

Far East Amusement Research

More popularly known as “FEAR,” Far East Amusement Research represents the second generation of Japanese RPG talent, coming to prominence just as the country’s roleplaying market started collapsing in the mid-’90s. Born from a collective of experienced writers and designers, FEAR played a major role in the hobby’s transition to a more narrative type of play and was instrumental in popularizing the use of structured, scene-based game sessions.

In its earliest years, the company struggled to get its titles to market as more and more publishers withdrew from the roleplaying space, ultimately opting to establish its own publishing and distribution arm, Game Field, alongside a monthly magazine called Gamers Field. As a result, from 1998 to 1999, FEAR was virtually the only significant source of new RPGs in the Japanese market.

Unlike its competitors, the company has never ventured too far outside of the tabletop genre. The one notable exception is its work in the video game industry: since the mid-’90s, FEAR’s staff have provided story and world-building support for a number of titles, including Square Enix’s Octopath Traveler and Bravely Default II.

Key Works: Tokyo N◎VA, Tenra Bansho, Seven = Fortress, Double Cross, Night Wizard, Alshard, Arianrhod

--

Arclight

Technically no longer an independent developer - the business has been wholly owned by Shinkigensha since 2020 - but bears mentioning all the same. Arclight started out in the play-by-mail market as a branch office of the company You-En-Tai before going independent in 1998. After a brief stint in electronic gaming, the company refocused its operations around the analog scene, and now develops and publishes a broad slate of board, card, and roleplaying titles. Its most prominent property by far is the Japanese edition of Call of Cthulhu, which Arclight has overseen since launching its 6th Edition back in 2003; in addition, the company currently handles Japanese localization for Pathfinder and Shadowrun.

CoC aside, Arclight is arguably more notable for its general business activities than its game releases: the company operates dozens of specialty retail outlets in addition to providing editorial oversight for the monthly RPG magazine Role & Roll and organizing Game Market, one of Japan’s most significant analog gaming events.

Key Works: Call of Cthulhu (6E/7E), Pathfinder (1E), Shadowrun (5E)

The now-defunct Akihabara branch of Arclight’s Role & Roll Station, one of the company’s three retail chains.

--

Adventure Planning Service

Formed in 1987 by designer Koji Kondo (近藤功司) - not to be confused with the legendary Nintendo composer - APS has had three distinct incarnations over the years. During the RPG boom, the group’s claim to fame was its generic rule system Apple Basic, which underpinned most of its early releases, including 1991′s Kiki’s Delivery Service-indebted cult classic Witch Quest. By the early ‘90s, however, Kondo and his colleagues shifted their attention to the electronic gaming market, providing production, planning, and story support for various titles across six console generations in addition to penning an assortment of strategy guides and fanbooks.

The company’s return to roleplaying in the late 2000s was driven by the arrival of developer Toichiro Kawashima (河嶋陶一朗), whose Saikoro Fiction system now powers a majority of APS’s releases. To date, there have been over a dozen Saikoro Fiction titles, most notably multi-genre horror RPG Insane, modern-day wizarding game Magicalogia, and contemporary ninja drama Shinobigami.

Key Works: Witch Quest, Satsupe, Labyrinth Kingdom, Shinobigami, Insane, Magicalogia

--

ORG

Though effectively inactive in the tabletop space now, ORG was one of the very first RPG development groups to go professional. Its founder, Masayuki Onuki (大貫 昌幸), earned his spurs translating the original D&D and would subsequently author WARPS, an anime-inspired universal system emphasizing high power levels and flashy action, which released soon after ORG’s establishment in 1987.

Whlie the company developed a number of original and licensed roleplaying games in the ‘90s, it is perhaps most fondly remembered for Legend of Double Moon (ダブルムーン伝説), a play-by-mail “reader participation” RPG featured in the gaming magazines Marukatsu Famicom and Marukatsu Super Famicom from 1989 to 1993. Following Onuki’s death in 1993, ORG largely refocused its activities on the CCG market, helming tie-ins like the Digimon and Monster Hunter card games.

Key Works: WARPS, Legend of Double Moon

0 notes

Text

What Makes Japanese Tabletop RPGs Different?

In my introduction, I made the argument that Japanese pen-and-paper games can almost be treated as a separate line of development from Western RPGs, one that’s evolved in unique, sometimes unexpected ways thanks to a combination of various factors.

But what does that actually mean in practice? What exactly is it that sets Japan’s tabletop titles apart from their peers?

They’re the product of a publisher-driven industry.

In the Western roleplaying market of the ‘80s and ‘90s, companies like TSR, GDW, and White Wolf were masters of their own destiny - they designed, laid out, and produced their own books, and ultimately decided which projects they wanted to embark on.

Meanwhile, Japanese RPGs of the era were produced in partnerships between small, independent groups of designers and major book and magazine publishing houses like media giant Kadokawa. The publishers shouldered the responsibility of printing, distributing, and marketing the games, which meant they also called the shots: if a publisher wasn’t interested, an RPG simply wouldn’t see the light of day.

This dynamic left Japan’s first generation of tabletop designers bouncing between original projects, translations of Western titles, and licensed tie-ins of wildly varying quality - in short, whatever they could secure publishing contracts for. It also meant that once publishers started losing interest in the RPG market in the mid-'90s, game output slowed to a trickle, sparking Japanese roleplaying's so-called - and thankfully temporary - "Winter Era."

The peak of the '90s boom saw a wave of oddball licensed products, such as 1992′s kid-focused Dinosaur Sentai Zyuranger RPG and its rock-paper-scissors resolution mechanics. [IMAGE: Mandarake.com]

The balance of power has shifted a bit over time thanks to digital distribution and a stronger indie scene, but publishers are still the biggest driving force in Japan's RPG industry and continue to shepherd its best-known titles.

The books are more spartan - and more diverse in format.

If anything underlines the difference between the Japanese tabletop culture and its Western counterpart, it’s this: America’s most popular fantasy RPG, Dungeons & Dragons, comes packaged as a glossy full-color hardback with an MSRP of US$49.95. Japan's most popular fantasy RPG, Sword World (ソード・ワールド), is a modest pocket-sized paperback retailing at ¥990, or US$7.71 at the time of writing.

Sword World’s budget-priced format dates back to the game’s original release in 1989. [IMAGE: Mercari.com]

Today’s typical Japanese roleplaying game is presented in a softcover book with a black and white interior, and can range in size from the aforementioned ultra-compact A6 paperbacks to larger B5 volumes that clock in at around 78% the size of a Western 8.5 x 11" rulebook. These no-frills formats are designed to be produced at scale and are sold comparatively inexpensively - at least when stacked up against slicker Western competitors like D&D and Call of Cthulhu.

An unintended side effect of this more restrained style of presentation is that the gap between “professional” and “indie” titles can be relatively narrow: the amount an independent group has to spend to punch at the weight class of an RPG from big-name publishers like Kadokawa and Shinkigensha is much lower than their Western counterparts would have to fork out to get up to Wizards of the Coast levels.

A growing number of small-format paperbacks, including Kadokawa’s Dark Souls TRPG, print play aids like character sheets on the outside covers under the dust jacket for easier copying.

They place a greater emphasis on player education.

Easing newcomers into the fold has always been a challenge for the roleplaying industry, but Japan arguably takes the topic more seriously than any other market: over the decades, an entire ecosystem of how-to comics, magazine columns, and guidebooks with titles like RPGs Are Not Scary! and Even Girls Want to Play RPGs! has grown up around the hobby.

This handy belly band from Kadokawa’s Skynauts has a short explanation of roleplaying games and lists requirements for play as well as the RPG’s major themes.

The Japanese industry’s most popular educational tool, however, is the replay - an extended session transcript that tells a story while illustrating how various game rules shake out in practice. This format first cropped up in the pioneering wargaming publication Tactics in 1982, but didn’t grow truly ubiquitous until 1986, the year the D&D campaign Record of Lodoss War made its debut as a monthly feature in the computer gaming magazine Comptiq. Lodoss - effectively Critical Role three decades before the fact - unexpectedly spawned both a media empire and a full-blown replay craze. By the early ‘90s, such transcripts were a fixture in roleplaying magazines and had even found an enthusiastic audience in paperback form.

Most major titles inevitably spawned their own series of published replays during the RPG boom, and Western properties like Shadowrun and Mechwarrior were no exception. [IMAGE: Mandarake.com]

Having effectively become a self-contained form of entertainment, replay culture managed to survive the industry's late '90s doldrums mostly unharmed, and remains a staple of the Japanese tabletop scene. Over the years, the format has also become increasingly integrated into RPG rulebooks, which often begin with an extended replay section before moving onto mechanics and other specifics. This approach gives readers a feel for the tone and cadence of a game right off the bat, and creates added context for the actual rule sections further on.

A play example from Shinkigensha's vampire road trip RPG Dark Days Drive. A good 132 of the book's 256 pages are devoted to the replay section.

They’re written for a culture with more hurdles for play.

In the US and elsewhere, gaming sessions tend to happen at private homes, usually around a dinner or living room table, and take up the best part of the day if participants are able and willing. Japan, where space in large cities is at a premium, sees a lot more roleplaying in public venues like school and university rooms, community centers, or even karaoke booths.

This arguably encourages Japanese designers to approach their work in a more time-conscious and structured fashion: if your audience only has access to a gaming space for a few hours and might even be paying for the privilege, the last thing they need is 50 minutes of people arguing their way through the ins and outs of character generation before play can even start. This manifests itself in design choices like:

Roll or Choice (ROC): This concept has become so prevalent in Japanese RPGs that it’s acquired its own shorthand along the way. ROC presents players with a table of options and allows them to either generate a random result or just pick the one they like best. This is often used to take a lot of the deliberation out of things like character backgrounds, replacing long-winded PC biographies with a simple roll of the dice. ROC can also be used as a GM aid, allowing events and adventures to be cooked up on the fly during the session.

An example of an ROC table from 2022′s Octopath Traveler TRPG, in this case used to determine a character’s origins.

Sequenced Play: It’s not uncommon to see Japanese RPGs divide sessions into a sequence of phases or steps akin to a board game. On the most basic level, this breaks play down into "opening," "main," and "ending" phases, providing players with clear guidance as to what actions and activities are performed at each point. Of course, some games get even more granular than this: indie sci-fi title Wyvern Element, for instance, carves up its action into Briefing, Training, Mutation, Day-to-Day, Combat, and Debriefing Phases. While this approach might seem restrictive at first glance, it also provides a clear narrative structure for the session and helps keep a group on track.

Lower Player Requirements: Recent years have seen a proliferation of two- and three-player RPGs such as Circle Draconian’s well-regarded Silver Sword: Stellar Knight (銀剣のステラナイツ) . These small-group games - often refered to as “buddy action RPGs” - allow for more intimate narratives, but also minimize the stress of assembling enough players and finding the requisite space for them.

Compressed Sessions: Where mainstream Western RPGs tend to take a long-term view and assume the PCs’ tale will be told over a larger number of sessions, Japanese titles often aim to tell a complete story with a clear climax and resolution in the space of one session. A few designers have taken this approach to its logical extreme by trying to cram a full-fledged adventure into the span of an hour or less, as seen in indie RPGs like 30-Minute Hero ( ��0分勇者), Trek & Treasures ( トレックアンドトレジャーズ), and Dungeon Seconds (ダンジョンおかわり).

--

This obviously isn’t a comprehensive rundown of everything particular to Japanese RPGs, but hopefully helps paint a bit of a better picture of some of their quirks and philosophies. Future posts may re-visit some of these points in more detail if the material and demand is there.

0 notes

Text

Why Japanese Tabletop RPGs?

This blog is arguably the end point of a decade-plus-long fascination with the Japanese tabletop scene, which was first sparked by the work of Andy Kitowski at the dawn of the 2010s and finally gained real momentum after a visit to Tokyo in 2020.

As somebody who’s roleplayed on and off since the early ‘90s and even managed a game store for a brief span of time, I’ve always harbored an interest in RPGs as both an art form and a business. From this standpoint, Japan makes for a particularly fascinating case study: it’s clearly a product of the Western roleplaying movement, but in terms of design, distribution, culture, and impact, it also often stands very much on its own.

What is it exactly that makes the Japanese tabletop industry so interesting?

It’s one of the most active RPG ecosystems outside of the English-speaking community. Japan’s roleplaying scene officially kicked off in the early ‘80s, and despite a few bumps in the road, it’s continued to thrive in the intervening decades. Between the independent creators and established publishers, dozens of new titles see release each year, including some genuinely wild and wooly concepts.

It’s almost unknown outside of Japan. Since the ‘80s, just about every aspect of Japanese pop culture has found a home on the global stage. Japanese tabletop games represent one of the few notable exceptions - aside from a tiniest handful of translated titles, Japan’s RPG output has never seriously crossed over into international markets, and is largely undocumented in English-language circles.

It represents a parallel evolution of the roleplaying hobby. While strong, active RPG industries have emerged in various countries since the ‘70s, they tend to fall in line with the design philosophies and business models seen in the US or UK. Japan is one of the notable exceptions: thanks to a confluence of cultural and economic factors, the Japanese RPG canon has taken some strange turns over the years, and is likely to keep forging its own path for the foreseeable future.

The Rolling Sun blog will be an irregular outlet for various explorations into the Japanese tabletop scene, including deeper research into its history, culture, and of course the games themselves. Where there’s opportunity to do, I’ll also be spotlighting other English-language voices working and writing in the space. If this seems like your idea of a good time too, why not follow along?

0 notes