#pen and paper roleplaying

Text

youtube

Gamers of a certain vintage may have fond memories of Beam Software’s 1993 version of Shadowrun on the SNES, or to a lesser extent, the 1994 Sega Genesis/Mega Drive game created by BlueSky Software.

Significantly fewer are likely to remember Shadowrun’s Japanese Sega CD adaptation from 1996, which not only was one of the last games launched on Sega’s failed add-on, but has never seen a full translation - official or otherwise - into English.

Unlike the more action-oriented SNES and Genesis versions, Shadowrun on Sega CD sticks fairly close to its source material, going as far as to incorporate actual dice rolls into combat. That fidelity can be chalked up to the involvement of Group SNE, who at that point were managing the Shadowrun franchise in Japan. The game’s scenario, co-written by Group SNE member Akira Egawa (江川晃), takes place in Tokyo and follows the cast of Egawa’s Shadowrun replays The Fallen Magician and The Nightmare Mark as they make their way through a series of episodic adventures.

The game’s cast represents a broad cross-section of Shadowrun archetypes. From left to right: Decker D-Head, Former Company Man Shiun, Street Samurai Rokudo, Physical Adept Sha, and Shaman Mao.

Setting-wise, this title draws from Egawa's somewhat controversial Tokyo Sourcebook supplement, a Japan-exclusive release that liberally rewrites the Shadowrun setting to make it more palatable to a Japanese audience. In Shadowrun’s early editions, the Japanese Imperial State (JIS) was presented as a militant, xenophobic superpower that eventually winds up invading and occupying San Francisco. Egawa’s Tokyo Sourcebook replaces this with a dysfunctional nation in the process of being torn apart by open warfare between rival megacorporations - a tweak that apparently didn’t impress hardcore Japanese fans, as several of them went on to write up an alternate JIS sourcebook, arguing that a villainous Japan was ultimately more interesting than a weak one.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Environments by Maxime Desmettre

Check out Tabletop Gaming Resources for more art, tips, and tools for your game!

#Maxime Desmettre#urban#snow#winter#monster#knight#encounter#environment#tabletop rpg#rpg#tabletop gaming#pen & paper#roleplayer#roleplaying games#games#dnd#d&d#pathfinder#dungeons & dragons#dungeons and dragons#fantasy rpg#forest

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a bag for all of my stuff for our pen and paper roleplay now and I am exited! 🌈

It is orgiginally a bag out of our freestore with a very ugly print on it, but i added the patch and the embroidery and now I really like it😊

#Patch#patches#upcylced#upcycling#solarpunk#pen and paper#dsa#das schwarze auge#roleplay#tsageweihte#Visible mending

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

~Asenath Waite: Cult of Dagon~

Inspired by H.P. Lovecraft's work we tried to go for a Cthulhu cultist themed session.

Based on the only really remarkable (at least seemingly) female character by Lovecraft, Asenath Waite, I wanted to create a glamorous look with only one single detail that would seem rather offputing. To emphasize with the fish people theme, I dropped Asenath's huge, fishlike eyes and rather went for gills - except for the one picture where I tried to make my eyes pop as much as humanly possible... ^^°

_

Model+MuA: Mircalla Tepez

Foto+Edit: _soulcatcher_photography_

Neronomicon: Naruvien

#call of cthulhu#lovecraft#cthulhu#tabletop rpg#rpg#tabletop gaming#pen & paper#roleplayer#roleplaying games#games#inspiration.pen & paper games#dnd#d&d#pathfinder#dungeons & dragons#dungeons and dragons#fantasy rpg#horror rpg#encounter#cosplaygirl#asenath waite#the shadow over innsmouth#innsmouth#larp#larp costume#larp character#larp oc#dagon#horror photography#halloween aesthetic

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pen & Paper Mario?

I may or may not have been quietly working on a TTRPG campaign for my friends, but I'm a little bit stuck. I had the original idea for a Paper Mario-themed campaign YEARS ago, but was held up by my "never having played a table-top before".

Past couple years I finally started playing D&D 5e and love it, plus with the recent Thousand-Year Door remake I've gotten inspired to take another crack at the idea. But I'm torn: 5e is the system I know best and it's pretty flexible as far as setting, but I'm worried it doesn't "feel" like Paper Mario. And trying to translate PM mechanics 1-to-1 wouldn't work either (you can't really do action commands with pen and paper, after all).

I'm curious in other game systems, and thinking about cribbing various mechanics and frankensteining them into something that works. But that's a lot of research and work for someone without a huge amount of experience with the hobby. (If anyone has suggestions please chime in!)

I have definitely had thoughts that I'm strongly considering using, which I'll log here.

Action Dice (Panic at the Dojo)

Panic at the Dojo is a really cool game based on arcade fighting games, and I love the Action Dice system. Each character has a collection of dice they can roll at the start of a turn, and use the numbers as a resource for their abilities that round. It's a little like drawing a hand of cards to play for that turn. I think something like this could be used within a battle system to simulate Flower Points and Action Commands, and needing to use limited resources to figure the best series of moves for the battle in front of you feels very PM to me.

Split abilities between Species and Job/Class?

My general pitch for Pen & Paper Mario is the player characters are Mario-universe monsters, like Mario's partners in the games. So players would pick a species (like Goomba, Blooper, or Boo) and their abilities would in some way reflect that. One of my struggles is how best to balance that with team roles: Players would want to feel like they're playing as that type of creature they picked, but without being pigeonholed into a specific role.

Possible solutions:

-Simplify classes and split character abilities more evenly between the two choices?

-Skill trees for species? So players can pick a direction for their species abilities to go, based on how they want to play

-Something else? I'm a little lost on how to resolve this, I just know that I want creature choice to matter and for species abilities to grow with progression

Badges

Gotta have badges - these can mostly replace equipment/magical items and there's a lot of flexibility for what kinds of mechanics they can effect. I personally think badges are more central to Paper Mario's gamefeel than items.

#paper mario#ttrpg#ttyd#paper mario ttyd#dnd#d&d#dungeons and dragons#panic at the dojo#roleplaying games#ttrpg design#mario#nintendo#pen & paper mario

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

OKAY SO

Tomorrow, me, @atak-achrativ and @freshlybakedpigeons are going to stream Star-spawned, roleplay made by @prokopetz!

EDIT: time will be at 6:30 Central European Time!

twitch_live

This is a GMless roleplay. The core concept is that we are playing eldritch beings who were just born, therefore we have no idea about what our stats mean.

So, we are applying the scientific method to it. We are gonna make hypotheses and test them. We are very smart eldritch beings.

#roleplay#star-spawned#i am so very excited about this#the game system is really cool#the people are also very cool#also Prokopetz made me get back into programming. ...because this godDAMN SYSTEM OF FAILURES AND SUCCESSES#ill explain it on stream and the link takes you to the rulebook#but essentially it makes use of prime numbers for calculating successes and failures and also the highest or lowest rolls#which together with the ruin/glory system makes it possible to make to get a hypothesis refuted and get ineffable glory as a result#and i think glory gets more likely as you get more dice but proving the hypothesis gets less likely. I think.#anyways calculating this for two dice needed pen and paper. and at this amount of player we got four maximum dice.#so i am writing a program because i wanna know the god dang chances

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick portrait of my Star Wars OC.

Meet Twiwi Aanta, obviously a young Rodian and a Jedi Padawan. Her color scheme turned out so girly xD

She is very quiet and rather shy, but when she talks, she does it in a very nasal voice. Her most famous catchphrase is: "Oh no..!"

Hope you like her! :D

Add-on: Twiwi has a little cameo in Eden's short Ahsoka realises something

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's a lot I like about Masks: A New Generation, but if I had to pick one single favourite, if you absolutely twisted my arm, I'd probably say 'shifting labels.'

If you're not familiar, Masks is a roleplaying game about teen superheroes, telling stories in the vein of Young Justice, Teen Titans, or Runaways. It's got lots of potential for drama, angst, heroism, and climactic battles against giant robots.

Labels, in the game, determine your character's strengths and weaknesses – a character with high Saviour will be good at protecting innocent bystanders, while one with high Danger is better at beating the villains in a brawl, and so on. The thing is, unlike in a lot of other RPGs, your labels aren't some physical aspect of you, like strength or toughness or even intellect – they're more about how you see yourself. And naturally, that means they can change.

Now, like I said above, Masks is built around teen heroes, and that means one of the big themes of the game is that everyone has their own idea of who you are or who they want you to be, and boy oh boy, will they make that your problem. Villains will tell you they see great potential in you, friends and mentors will tell you all about who you really are inside, regular people in the street will yell at you because they think all superheroes are secret robots, and every time that happens, it can change how your character sees themselves.

Yes, even the 'secret robot' thing.

So whenever someone does that to your character, there's a good chance they will be able to shift your labels, and twist you into a new version of yourself, making you better at some things and worse at others. Sometimes that’s a good thing. Maybe your mentor tells you to be more responsible, and you take that on board and get better at protecting your friends. Maybe a friend tells you how smart you are, and you use that cleverness to see through a villainous scheme.

But life isn’t simple, and sometimes the things your friends say to you can pull you in a different direction than the one you had in mind. You can try and resist, of course, but you might not want to risk it. Yelling at a good friend that they're wrong about you might be bad for the relationship, and as for standing up to a mentor...yikes. On the flipside, the villains probably don't have your best interests at heart, but that doesn't stop them from saying things that boost your ego, things you want to listen to. Do you accept a boost in power, knowing who it’s coming from?

By adding that amount of mechanical weight to these social interactions, Masks encourages some really interesting choices, and opens the door to triumphant moments where your hero throws off everyone else's influence and shouts to the world 'this is who I am!'

And I think that's pretty damn cool.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

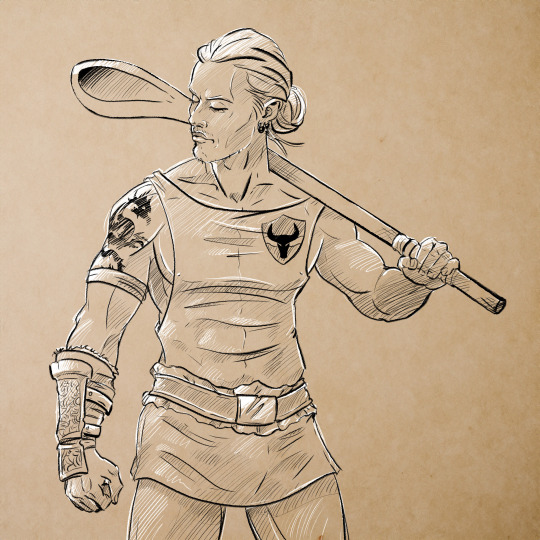

Something not Warhammer-related: Revro, the professional Imman-player.

In Germany, the role-playing game system DSA ("Das Schwarze Auge" - "The Black Eye"), now also forty years old, is more popular than D&D. It has much more complex rules (both blessing and curse) and is more geared towards building a character that fits into the incredibly detailed world and interacting with the creatures and circumstances there. The power level is lower and the characters rarely become overpowered heroes. On the other hand, there is the opportunity to explore all kinds of well-developed areas, cities and political contexts and you can easily be a travelling blacksmith, a cartographer or a wonderfully useless, incredibly nerdy mage. Or a trader, a mercenary who is actually a cook (or vice versa) or a tattoo-artist.

Of course, this also means that an average DSA adventure is not a dungeon crawl.

Which led to our game master "gifting" us an NPC who is a celebrated Imman player in Havena the not very mage-friendly town we are currently involuntarily staying in. Imman is a very popular team sport, distantly related to hurling. Revro, that's his name, plays for the Havena Bulls and has developed a crush on my clueless mage. Much to the continued amusement of the rest of our group.

Doesn't matter - my mage is happy. Finally, someone who is willing to listen to his elaborate explanations of old-puninian number magic!

And because I had so much fun with Revro, I sketched him and hope we can keep him.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started playing Baldur´s Gate 3 today. (Took some convincing from friends and my husband.)

After 3 hours of play, I´m already invested. The game developers did a fantastic job! Graphics are fabulous, mechanics - typical for Laria games like Divinity - could be better for someone with my preferences but is good, and the plot is captivating.

Chose to go into this adventure with a Half-Elf Paladin.

#baldrus gate 3#half-elf#paladin#dnd#game development#recommendation#fantasy#adventure#divinity#forgotten realms#gaming#video games#shadowheart#gale dekarios#elves#roleplay#pen and paper#tabletop games#original character#female original character#dungeons and dragons#baldurs gate

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Commission for my dear friend @/intro-verve on Twitter, showing Pettar Peddersen, one of his DSA characters :)

#dsa#dsa 5#Das Schwarze Auge#the dark eye#pen and paper#DSA5#Dungeons and Dragons#TDE#tabletop rpg#tabletop roleplaying#tabletop games#penandpaper#my-art#Fanart#artists on tumblr

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indie Roleplaying in Japan

Independent RPGs are a vital, vibrant part of the Japan's tabletop scene, both a movement in their own right and a talent incubator for publishers on the prowl for the next big thing. That said, this prominence is a relatively recent shift: during the boom years of Japanese roleplaying, indie titles existed on the margins of the market, produced by die-hards for die-hards. It would take the near-death and resurrection of the tabletop industry - and several decades of persistence - for these creators to finally get their due.

The Fandom Factor

Like most independent RPG scenes, Japan’s indie output is split into original and derivative works. This in itself isn’t especially noteworthy: after all, a good chunk of the global small-press market is dominated by third-party releases for existing systems, ranging from mainstream juggernauts like Dungeons & Dragons to cult faves like Mörk Börg or Mothership.

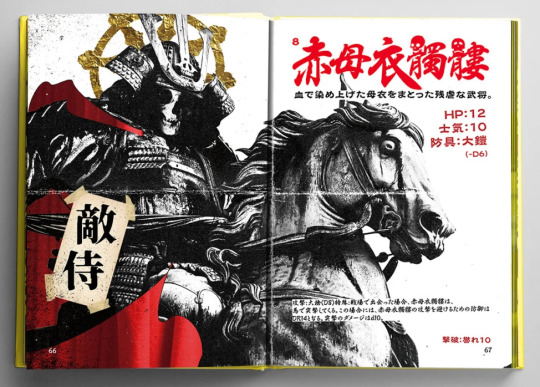

Such as 2022′s Nobunaga's Black Castle, Japan’s first venture into the realms of black metal fantasy.

What is notewothy is how the Japanese RPG scene has dealt with derivative products - especially the unauthorized ones.

In the West, piggybacking on an established system or property has always been fraught with a certain amount of legal peril. The ‘80s and '90s in particular saw an assortment of dust-ups between big-name publishers like TSR and Palladium Books and smaller creators - particularly fansites - over both actual and imagined IP violations. Things shifted significantly with the introduction of the D&D Open Game License (OGL) in 2000, which allowed third parties to produce D&D-related content without having to pay fees or royalties. However, these products still had to adhere to an explicit set of guidelines - one that could force an incautious company to pulp an entire print run of books.

By contrast, Japan’s rights holders historically didn't fuss much over derivative works, even ones sold for money, unless the infringement was particularly egregious. This resulted in the creation of a massive gray market of for-profit fanworks that has grown to annual sales in the region of US$800M - a not-inconsiderable chunk of Japanese otaku spending. Semi-protected as “parodies” in the eyes of the Japanese law, these products take various popular or nostalgic IPs and spin them off into new directions - respectful, comedic, pornographic, and everything in between.

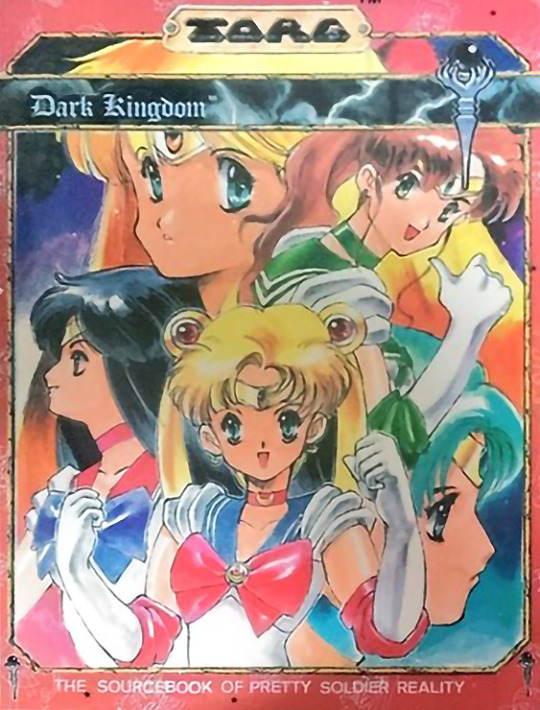

While the overwhelming majority of for-profit fanworks are comics or comic-adjacent material like artbooks, RPGs also carved out a niche in this market through unofficial supplements, adventures, and even entire roleplaying systems. Largely unconstrained by legal worries, Japanese tabletop fans could produce IP-infringing double whammies like 1993′s Dark Kingdom: a thoroughly unlicensed sourcebook that imports the cast of pop culture evergreen Sailor Moon into TORG, West End Games’ RPG of fractured realities.

Dark Kingdom was an early showcase for Jun'ichi Inoue (井上純一), who would later enjoy a fruitful career at FEAR creating notable titles like Tenra Bansho (天羅万象 ) and Alshard (アルシャード). [IMAGE: Dragoon_Shaytan via Twitter]

Over the years, other popular IPs inevitably also got the tabletop treatment, resulting in fan-made adaptations of everything from ’80s anime relic Dream Hunter Rem and classic shoot-’em-up R-Type to contemporary megahits like Fate/stay night and Bleach. Even today, it’s possible for a creator to knock out an RPG based on Dragon Quest - one of Japan’s largest and most prominent roleplaying franchises - and put it on a digital storefront for US$16 without immediate fear of a thermonuclear-level copyright strike.

However, until around 2010, these sorts of derivative works were more of a sideshow than anything else. That changed once Call of Cthulhu established itself as Japan’s best-selling RPG, buoyed by a series of popular - and irreverent - actual play videos and the Mythos-Goes-Harem antics of the Nyaruko: Crawling with Love media franchise. Suddenly, freshly-baked Cthulhu fans were appearing at gaming conventions in increasing numbers, resulting in a corresponding boom in fan-made CoC adventures and supplements.

As Call of Cthulhu grew to dominate the local tabletop industry, its fanworks cast an equally long shadow over the indie scene, eventually accounting for an estimated 80 to 90% of all derivative products on the market. This extreme popularity would have repercussions: in 2021, facing pressure from the game’s creators, Chaosium, CoC licensees Arclight joined forces with Japan’s most prominent RPG companies to create the Small Publisher Limited License (SPLL) program, which set content guidelines and royalty fee requirements for any third party publishing material for an established system. This was an unusual arrangement by Japanese standards, though one that also gave new legitimacy to derivative works within the roleplaying community.

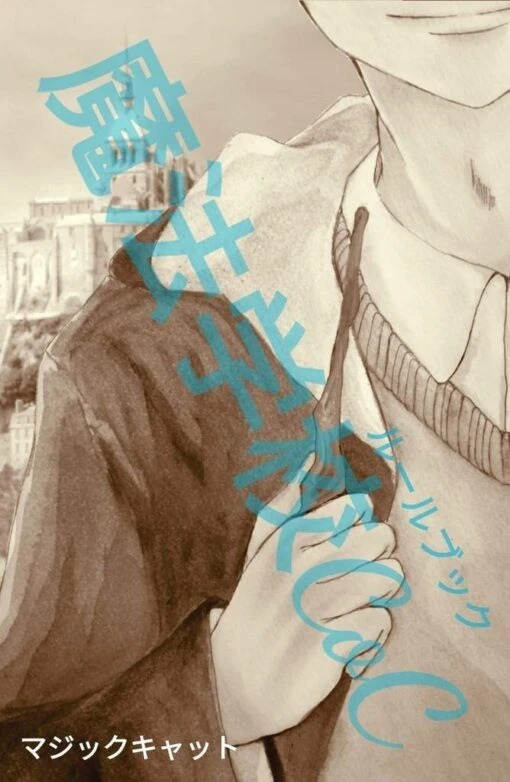

As was the case with D&D, Call of Cthulhu’s rules have been used as a springboard into other game styles and genres. For instance, the Magic Academy CoC (魔法学校CoC) series reworks Chaosium’s system to accommodate Harry Potter-ish adventures.

An Interlude on Doujin Culture

Derivative works are just one facet of Japan’s indie RPGs, but an important one to start with - in large part because the impact of the Japanese fanwork scene extends much further than just Sailor TORG.

Thus far, when I’ve used the word “fanwork,” it’s been to refer to what the Japanese would formally call “doujinshi.” In the West, that term is intimately associated with fan comics, especially pornographic ones, but the word simply refers to any independently created and published print product - more specifically, one put out by a doujin (同人) or “circle” of like-minded individuals.

The doujinshi concept dates back to the 19th century, but only truly gained traction in the 1980s - a point where more affordable, accessible printing options made it possible for enterprising hobbyists to produce and sell comics as a full-on side gig. As the number of indie creators grew, events emerged to give these artists and writers a venue to market their wares - chiefly Comic Market, which began as a modest volunteer-run show in 1975 but would eventually grow into the world’s largest comics event by a significant margin.

As the doujinshi market grew in size and scope, a new generation of printing companies emerged to serve this subculture through cheap, high-quality digital printing and low minimum order quantities. This further reduced barriers to entry, giving even amateur artists access to professionally bound products at an manageable price.

This ecosystem of affordable production and dedicated sales events created a vital foundation for Japan’s indie roleplaying groups - and a sorely needed one, as up until the mid-‘90s, the cost and complication of producing RPG products kept independent releases relatively scarce. As a result, early offerings like Bläde & Wörd (ブレード アンド ワード), ITHA WEN Ua ( イサー・ウェン=アー), and Small Still Voice (スモール・スティル・ボイス) played it safe by skewing toward orthodox Western-style fantasy - and largely sank in the market with scarcely a ripple.

Thanks to its multifaceted magic system, 1991′s Bläde & Wörd enjoyed somewhat more longevity than its fellows, eventually spawning a second edition under the somewhat unlikely title of “Acoustic Leaf“ (ブレード アンド ワード) in 1995.

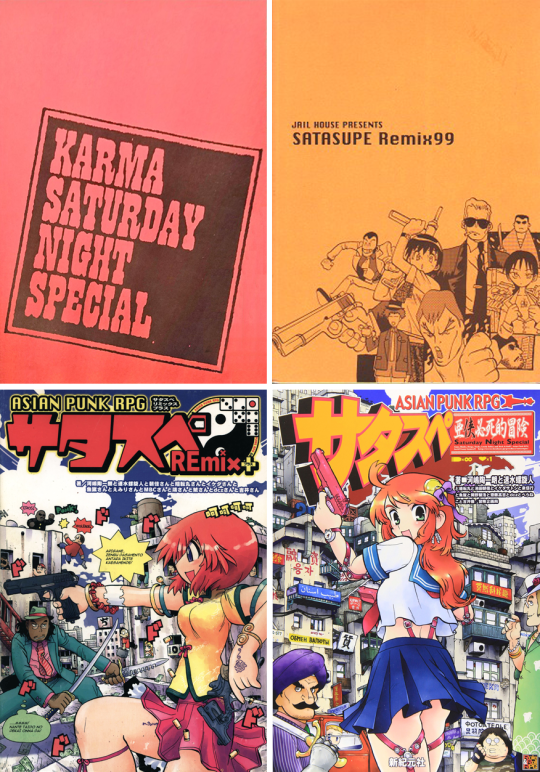

The ability to source cheaper, better-looking books at lower order quantities arguably helped RPG creators shake loose some of this conservatism - perhaps best exemplified by 1996′s Karma Saturday Night Special, later known by the shorter, punchier alias “Satasupe” (サタスペ). Set in an alternate history where the United States did not enter World War II and a nuke-ravaged Japan found itself divvied up by various superpowers, this gangster RPG dunks its players into a gonzo stew of Soviet narcotics farmers, voodoo practitioners, Japanophile mercenaries, biking Crusaders, criminal animal handlers, UFO cultists, and more besides.

Satasupe’s creators, “Jail House,” started off as a loose-knit collective with almost a dozen credited members, building up their audience and reputation over several years before striking paydirt with 1999′s SATASUPE Remix99 (サタスペ・リミックス99). Remix99 would prove popular enough to attract attention from the wider industry, and in 2003, a revised and expanded version called Satasupe REmix+ ( サタスペ・リミックス+) earned a release through Hobby Base, the publishing arm of the game store chain Yellow Submarine.

To clean the game up for its commercial debut, Jail House partnered with Adventure Planning Service, one of Japan’s oldest RPG design companies. The collaboration proved so fruitful that Jail House was effectively absorbed by APS, and Satasupe’s lead designer, Toichiro Kawashima (河嶋陶一朗), would quickly become one of the company’s most important creators, spearheading future hits like Labyrinth Kingdom (迷宮キングダム) and the now-ubiquitous Saikoro Fiction line.

The evolution - and professionalization - of Satasupe’s rulebooks doubles as a mini-history of Japanese indie roleplaying as a whole.

A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats

On the whole, the early 2000s were a transformative time for independent roleplaying. In the West, the third edition of Dungeons & Dragons made its debut alongside the Open Game License, which unleashed a new generation of hobbyists and small publishers eager to capitalize on the excitement generated by D&D’s first major new edition in 11 years. Around the same time, independent RPG creators also began establishing their own distinctive culture and philosophy, driven by influential online discussion forums like The Forge. And behind the scenes, indie creators of all stripes benefitted from the growing availability of sophisticated desktop publishing software, which continuously narrowed the aesthetic quality gap between “amateur” and “professional” games.

In Japan, the OGL attracted significantly less direct interest, though it would eventually inspire comparable “open-source” systems like FEAR’s Standard RPG System (SRS) and Adventure Planning Bureau’s Saikoro Fiction. A more notable development was the introduction of FEAR’s Game Field Awards in 2000, which allowed aspiring designers to submit board, card, and roleplaying games to the company for potential commercial publication. This proved to be an important new outlet for independent creators, and helped birth notable titles like 2005′s TORG-inspired Chaos Flare (異界戦記カオスフレア) and 2001′s Double Cross (ダブルクロス), which is credited with helping to establish the more systematized approach used by modern Japanese RPGs.

2000 also saw the debut of Game Market - or “Gema” for short - a twice-a-year event that positioned itself as a Comic Market equivalent for analog hobbies. Though Gema’s foot traffic was only a fraction of its role model’s, the show would gradually establish itself as a go-to for unveiling new RPGs, especially once stewardship of the event passed to Call of Cthulhu licensee Arclight in 2010.

2010, in fact, seems to be generally regarded as the true starting point for Japan’s modern indie RPG scene - thanks again to the CoC craze, which not only produced a mountain of derivative products, but dramatically changed the size and demographics of Japan’s roleplaying fandom by drawing in both younger gamers and female players. This expanded audience appears to have to encouraged a greater diversity in game design and themes - less anime-inspired power fantasy, more high-concept exercises like “what if the players were actors in a movie production scrambling to finish shooting with no script and no budget before the whole project implodes?”

2012′s Reading! Manga Lord (爆走!まんが道) and 2013′s Idol Box! (どるばこ!) exemplify the indie scene’s broader swing towards less traditional RPG topics after 2010.

Surprisingly, some of this mindset even spilled over to Japan’s two biggest RPG publishers, Kadokawa and Shinkigensha - as evidenced by the fact that Satasupe received a mass-market release through the latter in 2008, eventually followed by other oddballs like the youth band RPG Strato Shout (ストラトシャウト) and Mofumofu Stream (もふもふストリーム), a game about YouTubers fighting crime with their psychic pets.

A final notable development in the indie scene was the emergence of online storefronts for independent RPG releases. While digital publishing has slowly become more prominent in the Japanese tabletop market, physical copies still dominate the indie space and groups invariably end their events with unsold game stock that needs to be offloaded elsewhere. The launch of Cokage in 2014, followed by Conos in 2016, provided an important outlet for excess copies and doubled as a means of making small-press games accessible to fans in rural areas who wouldn’t normally be able to attend a sales event.

Notable Creators

There’s an enormous quantity of indie circles currently active in the tabletop space, with more joining the fray on a monthly basis. A comprehensive list of every group is a bit beyond the scope of this post, but let’s take a quick look at a few of the longer-running ones:

Draconian: Originally a partnership between system designer Fuyu Takisato (瀧里フユ) and worldbuilder Shio Botan (潮牡丹, AKA Darya Tide), Draconian began publishing in 2014, gradually taking on more members to become a five-person operation capable of releasing multiple games per year. In 2018, the group officially crossed over into mainstream publishing with Silver Sword: Stellar Knights (銀剣のステラナイツ), a two-player RPG distributed by Kadokawa. Since then, the circle has put out several more titles through both Kadokawa and Shinkigensha while continuing to self-publish its more experimental work.

Draconian’s titles tend to focus on questions of identity, reality, and relationships with others, typically in fantastical or post-apocalyptic settings. Its more combat-intensive games share a battle system known as Diaclock, which was made openly available for use by other creators in 2020.

youtube

In recent years, Kadokawa have begun experimenting with promotional trailers for their RPG releases - in this case for Stellar Knights.

Phantasm Space: Founded in 2014, Phantasm Space is responsible for the steampunk aerial exploration game Skynauts (歯車の塔の探空士<スカイノーツ>), the Porco Rosso-inspired Il Paradiso Celeste dei Cacciatori Extro (チェレステ色のパラディーゾ), pastoral fantasy title Floria: The Verdant Way (翠緑のフローリア), and the comedic Villain’s Quest (ヴィランズクエスト). All four games have a lighter tone and showcase unusual ideas and mechanics; Villain’s Quest, for instance, throws its anti-heroes into pitched strategy meetings where participants use cards to advance various proposals; eventually, things climax in an analog tower defense game as the players scramble to protect their evil master from being slain once more.

The circle’s leader, Lord Phantasm, went pro in 2020 by joining Adventure Planning Service under the pen name Eisuke Nanashi (中西詠介). In 2021, Nanashi and APS published a revised version of Skynauts through Kadokawa. That same year, Floria also received an English-language translation courtesy of Silver Vine Publishing.

youtube

Another Kadokawa trailer, this time for the 2021 edition of Skynauts.

Rommel Games: Though Rommel Games began publishing RPGs in 2013, the group’s big breakthrough would come the following year with Galaco and the Tower of the Broken World (ガラコと破界の塔), a mecha dungeon crawler set on a distant planet. The game’s slick, commercial-level production values made an immediate splash in the RPG scene, and a number of indie creators readily credit Galaco as an influence on their own work.

In 2017, Kadokawa picked up the circle’s fast-paced superhero title Deadline Heroes (デッドラインヒーローズ), which was followed by a villain-focused version entitled Black Jacket (ブラックジャケット) in 2019. The line’s success may be attributed in part to the buzzy My Hero Academia franchise, which made its anime debut in 2016 and continues to enjoy a dedicated following in Japan.

--

New Game Plus: This collective of young game designers has maintained a healthy and eclectic output since first appearing on the scene in 2018, with titles that include Night Butterfly ( ナイトバタフライ ), an RPG about male nightclub hosts, and the aforementioned Mofumofu Stream.

Calling NGP an indie circle may be a bit of a stretch - the majority of its titles have in fact been released through Shinkigensha - but the group does put out the occasional doujin game. Sadly, its founder, former Group SNE associate Rikizo (力造), passed away from pancreatic cancer in 2020.

--

Shiawase Training Ground: Formed by systems engineer Go Yamauchi (山内剛), Shiawase Training Ground has been actively releasing material since 2014, producing offbeat titles like the medieval peasant survival sim Hoshikuzu Village Story (ホシクズ村々物語) and restaurant-focused A La Cuisine (アーレ・キュイジーヌ). Yamauchi’s upcoming “travel and escape” RPG We Will Happiness! (ウィーウィル・ハピネス!) has reportedly ended up with Adventure Planning Service, suggesting his mainstream breakthrough may be just around the corner.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

spirit of the forest by Alex Tarakanov

Check out Tabletop Gaming Resources for more art, tips, and tools for your game!

#Alex Tarakanov#npc#animal companion#druid#female caster#warlock#bird#tabletop rpg#rpg#tabletop gaming#pen & paper#roleplayer#roleplaying games#games#dnd#d&d#pathfinder#dungeons & dragons#dungeons and dragons#fantasy rpg#inspiration#mask

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

man i haven't written in earnest in years & years but the quality of.. most of these fics.... is making me desire to write what I want to read so it exists. hmm

#i think if i did write fics id post them under a totally different username LOL#id be way too shy to share#hm.#my current writing style is very intrispective but with the fics ive been reading it drives me crazy#when there are just like several paragraphs every couple convo sentences that add nothing to the story#i just scroll until i see more quotation marks and pick bsck up and i havent missed anything yet!#it works for what i use it for (roleplaying with my hubby lol) but it would NOT be good for this#there is someone whos fic has such a unique writing style it makes me want to get a pen and paper and study it#maybe i will?

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's ttrpgs?

I just stared at my screen like this

#i. don't know how to explain them when people actually ask but they're basically pen and paper roleplaying games where you make up a#character and you write down their info on a sheet of paper and then (most of the time) you use dice to determine how their actions go but#that's just in most of the campaigns I have ever played in#oh yeah !!! so campaigns are like long running versions of the adventures you play in as these characters and one shots are one off#adventures !!! the most notable ones are in the fantasy genre (like D&D and Pathfinder) but they can exist for any genre (modern fantasy)#and sci fi#within existing fictional universes with examples such as the Star Wars TTRPGs and the Alien RPG which are#less known :( the actual acronym stands for Table-Top Roleplaying Games ! I probably should have told you that at the beginning hehehehhe#my personal favorites are D&D#you also use 6 polyhedral dice for the games#sorry i started yapping so much im autistic and this is one of my special interests so I'm really passionate about this#if this still doesn't make sense please tell me so i can explain it more cohesively

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

So.

NASA made something amazing

ALSO

It has a nonbinary npc.

Need I say more?

10 notes

·

View notes