Text

Btw. The way that Stanisława Przybyszewska's name predestines her to become what she has become... Her given name was of course a kind of a heritage after her father (and there is way too much already said about that), but it is also a Slavic name with a very clear meaning: it means the one who will be famous. Her family name, also a legacy her family fought hard for for her, means a newcomer. And her original family name (Pająkówna) means a spider.

Do you understand who significant, how ironic that is?? She is the newcomer who is destined to be famous. She literally brings forth within herself something new (her father was one of the last celebs of modernism, and she is decidedly cuting ties with him; she even remodeled some of his novels in her own works). She longs for recognition of her genius and talent. But she is also, at her very core, a spider - that is, the very curse of female literary work. Women's work only being recognized as far as it is domestic/utilitarian. Women's work not being recognized at all. Women's work linked strongly to weaving and sewing. This weight of being a spider - a woman - is an anvil due to which she drowns.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

She reserved for herself the full right to her life

A small note at the beginning: the text below was what I presented during my first ever scientific conference this month. The main theme of this event was types of artistic methodology and research, and it was directed at people who knew exactly nothing about Przybyszewska, therefore the readers of this blog probably know all fo this already. I still feel like putting it out there, because I care about spreading awareness of Przybyszewska’s existence and uniqueness any chance I have.

Stanisława Przybyszewska remains to this day relatively unknown, as was the case for the majority of her life. She was painfully aware of it, especially since she has grown up by the side of her mother – Aniela Pająkówna, a celebrated Polish painter – as well as growing up in the shadow of her extremely popular father, Stanisław Przybyszewski, a writer whose fame only few could have matched back in the day. There is no surprise then, that little Stasia from very early on decided not to settle for anything less but to be celebrated as a genius she always felt she was.

Her life was marked by hard work since the very beginning. Given her mother’s unlucky circumstances, she was a witness to how a woman can – and must – survive on her own, with a small help from friends and family, but mostly making living through her own works. It was in a time and place where this much independence was not yet taken for granted for women, and it surely reflects in Stanisława’s later life. Her mother made sure Stasia was extremely well educated when it came down to artistic subjects, taking her to exhibitions (which in the 1910s in Paris were understandably on a very high level) and paying for private lessons in painting and violin; she also always encouraged her to write, and send the fruits of her labours to the distant, mysterious father. Because Aniela was dying from tuberculosis, she made precautions for Stanisława’s fate and secured mentors and guardians from among the family members and close friends, of whom she was sure they would continue pushing her daughter onto the path of greatness.

It did pay off. Stanisława was a very well educated young woman, whose only fault at the time was that she was too interested in too many subjects at once and so she tried her hand at everything, unable to decide on a career path for longer than few months. In her defense, it has to be said that as a child she proved to be brilliant at everything she tried, from painting, through philosophy, to mathematics. Aged 13, she wrote this in a letter to her aunt: Luckily I'm not as bored as I used to be, I found two things to do: [one is] journaling, the second one is easy - […] drawing [passers by]. It requires a lot of craftsmanship, which I would like to train myself to possess. Beside that, I'm studying anatomy for artists and would like to combine fine arts and science, namely electrotechnics and mechanics, but it's almost impossible. I do some sports with monsieur Geroges, namely running, gymnasticks and a bit of fencing. But that in itself isn't much, I don't know enough about fencing yet. Having received her education in various european countries, she spoke several languages and she thought about becoming a painter, a violinist and – naturally – a writer.

While this last choice seems to be heavily influenced by the mysterious on-and-off presence and absence of her father in her life, it was the best one she could have made. Not many of her drawings and paintings have survived, but those which did show off her creativity rather than enormous talent – the later lack of artistry could also be an effect of prolonged morphine usage. The epoch in which Stanisława was growing up was filled to the brim with brilliant painters of both genders (it was a golden age for female painters in Europe, who started gaining artistic and personal independence at a rate unmatched by any previous period in history), the competition was fierce and she surely would not have gained recognition for her visual works. In fact, she knew it herself, having dedicated the entirety of the year 1926 to painting only (setting writing aside, even writing for solely financial purposes as a feuilletonist to a newspaper), but to her dismay, she realised she had not had sufficient talent to lose herself in fine arts. And if she had chosen violin and became a musician, she would not be remembered for much longer after her death. The ephemeric nature of music, especially in times with limited recording technology, would not play in her favour. Thus, choosing literature and theater was the surest way to establish herself as a prodigy.

Due to the lack of family ties she inadverently gained independence at a fairly young age and had to make a living somehow. She tried working as a teacher, later as a secretary and a clerk in a bookshop, but all of these mundane tasks bored her to death. Aware of her exceptional talents, she felt she was wasting away the potential she could exhibit some other way. Luckily for her she did not care for the money – and even more luckily for her, her distant family cared about her and sent her small allowance, just enough to get by. This enabled her to fully immerse herself in the creative process of researching, writing and correcting the texts she wanted to publish.

What were the prevalent factors in making Przybyszewska a great author? In my opinion, a lot of this boils down to strict work ethics. When one takes a glance at her life, it’s clear she was not necesarily predestined to become great: born a bastard, orphaned in young age, betrayed by her father (who sexually abused her, emotionally manipulated her and introduced her to morphine, resulting in her lifelong addcition), widowed after only two years of marriage – none of this set her on an easy path. Were it not for her aunt Helena Barlińska, Przybyszewska would not have suffficient means to live, nor another person to confide in through letters. Because of her reclusivity and uncompromising way of being, she did not have many friends, and she usually managed to lose the ones she had made. It was as if she did not care at all about what others thought of her, or in what conditions she lived in (and these were abymsal), if only she was permitted to work.

After years of being a gifted child, a good student of various schools and private classes, she was well equipped to discipline herself into a literal working machine. This aligned perfectly with her views on humanity and personhood – she maintained a vision of them that was decidedly mechanical, or even robotical. She demanded of herself an inhumane amount of focus, regarding this as the only sure way to achieve greatness. Soon after her husband’s death in 1925 she cut almost all of the ties with the society and set on the path to become an impeccable author the only way she knew how: by putting herself through a regimen of hard work. I shall never be free, do you understand? Never. A succession of twenty-hour day of ever-heavier work until I die. [...] Today I have no personal life anymore. I cease to be a man: human sensibility, human feelings, desire – all these gradually wither and fall away in that hellish temperature of concentrated effort. I am becoming an impersonal, monstrously expanding, inflamed brain. Today I can see what is happening to me because I have time... and I feel strange. said she through words of Robespierre, her most famous character, but she was expressing her personal views on the matter in the same time.

The date that marks a shift from her previous actions (when she still tried numerous „normal” jobs and hoped for a financial independence from her family) is beginning of 1929. It is then that Przybyszewska writes to her aunt for the first time after 3 years long period of silnce: I have decided on what my profession would be. Two years ago; rather early, isn’t it? – I could be a writer, or nothing at all. Because, aside from this, I am not fit to be anything else, not a cook, nor a stenographer. [...] All questions aside, I flirted with literature ever since I was seventeen, but until I was twenty five I had serious doubts. My own works were not trustworthy enough. Now I am certain and will act, not only feel, by it. It means that I reserve for myself the full right to my life – this means Liberty with a capital L – no matter the price. And it is quite steep. Firstly and foremostly, it’s my dignity. And comfort. And safety. [...] I know from experience that one has to have their full powers at their disposal, if one wants to work in a creative field. [...] Therefore I balance myself just above the surface of Hades by means of miraculous acrobatics and divine interventions in the eleventh hour. Ever since this day, she fully proclaimed artistic independence rather than any other – looking at it from another side, her deciding on becoming a writer as her sole occupation, meant becoming a parasite as well, passively preying on her benefactors.

There is no doubt, though, that she took her decision very seriosuly and turned out to be a relentlessly hard worker, which can be proved by her epistolography. She has left as her legacy only a handful of creative works, but it’s letters where her natural talent shone. Thanks to professor Stanisław Helsztyński they were all gathered and published some 30-40 years after her death and can now offer a glimpse into her everyday life. Her life – which consisted of little more than writing and rewriting her own works, or pondering over them; she wrote sometimes about everyday matters, especially political ones, but rarely with genuine interest. Her world was then small and narrow, but incredibly deep to plunge into, which created a perfect space for honing her craft.

It is from her letters that we know what her normal day of work looked like. Her American biographers, Jadwiga Kosicka and Daniel Gerould sum it up this way: The pattern of Przybyszewska’s daily existence was rigorous but dreary: eight to ten hours of serious work (her artistic ‘output’), done almost entirely by night, occasional trips to a nearby grocery store to buy essentials on credit [...] visits to her German doctor Paul Ehmke to ger prescriptions for morphine, without which she could not concentrate or write, ventures out to the tobacco shop to get cigarettes (another addiction), or to the newsstand to buy papers, which she despised but could not stop reading, and rarer outings to the movies (she [...] found film superior to theater [...]). It is worth noting that even if she spent ‘only’ ten hours on the physical act of writing, almsot all of the other actions she undertook during the day were aimed in one way or another at bettering herself as an artist; even morphine she considered absoltely necessary for writing, while she abandoned such ‘luxuries’ (which any other person would consider ‘necesities’ rather) as kerosene for her stove. And in fact, the life described sketches in just few lines how self-denying her existence was.

Another part of a work-oriented life is undeniably studying. In the case of Przybyszewska, whose works were based on a specific period in european history (the Great French Revolution), this aspect was even more important. She researched Robespierre in times when it was in fashion to demonize him in order to jusitify the Dantonists. She studied in depth Albert Mathiez’s history books, the only ones who at least partially spoke to her convictions. Out of all of numerous plays about either the fall of Danton or the fall of Robespierre that had been written up to that point, she was the first to present a thouroughly Robespierre-centric point of view. She felt so misunderstood and alone in this position, she was often frustrated with her studies, but nonetheless, she persisted and almost all of her works depict this period of history.

How was it that a person so completely focused on work alone has produced not much more than what we now know to be her texts? Only three dramas, only one of them celebrated and fully finished. It’s important to say, too, that despite their excellency, she faced refusal after refusal when she tried to show them on stage and during her life time it looked like she would never be able to do it (the only premiere she had she did not even go to, sensing that the director did not do justice to her vision, and the play was taken off stage in a record setting time). A handful of short stories, which were not published in fullness until few years ago. Even lesser amount of sketches and paintings, which were never exhibited at all, and are stored away in the national archives in Poznań, never to be seen. The regimen she put herself through was her final undoing. She kept losing herself in her work, literally going mad whenever her cheap, rusting typewriter was in need of repairs, but did not agree to any help, including medical (after refusing to go to a drug rehab, she lost the last source of income she had). Just like characters from her works, she finally lost the battle of intellect&spirit, and flesh – in this instance: weak, plundered by addiction and malnutrition flesh – finally gave in. She died of an unknown cause, of which the most probable was freezing to death in her own apartment.

#thank you for reading! I know it's not anything exciting for anybody who already knows and likes Przybyszewska#my next text I hope I will be able this month as well and it\sgonna be either about Mary Magdalene-ness of Eleonore#or about the role of grey eminence Saint-Just plays in both dramas#stanisława przbyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#przybyszewska#artistic research#reseraching this i also learned a bit about Stanisława's verious siblings and her elder brother seems FASCINATING fr fr

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transnationalism

One thing which I haven't seen being brought up before, is the issue of transnationalism in Przybyszewska's work. At first - while I usually try to have a less biography-oriented approach - I have to say this cannpot be discussed without knowing Przybyszewska's very peculiar personal standing in regards to belonging to a nation and a state (but I will try to keep it to a minimum).

She was born as an out-of-wedlock child in times when it was not regarded lightly. Though both her parents were artists, and her father extremely extravagant and with a reputation of a Don Juan (bad reputation, and entirely deserved) at that, it didn’t change much. Her mother, no matter how artsy and talented she was, was herself a protegee of an influential family, not to mention - a youg woman. Which means her pregnancy was not taken lightly, her protectors were disappointed in her, she had to move to Paris not only because it was one of very few places were women could potentially make it big as professional painters, but because she would not be received in her usual society at home. All of this jumpstarts Przybyszewska's life as a person uprooted and banished from her home - but it's not all, nor is the fact that despite knowing who her father was, she was not officially recognized as his daughter until her teen years.

When she was born, Poland was still partitioned, which made Przybyszewska a stateless person, a subject to Austria, but of course not regarded as a fully fledged citizen (and that's without even taking into account the first 12 years of her life, when she lived as an expat, mostly in France, with her mother). In fact, she lived in these conditions for the first 17 years of her life, which makes it exactly a half of it (she died at 34). And if this was not enough, when she lived in Poland, she spent the majority of her time in Gdańsk, which was a Free City, with two nationalities - Polish and German - flowing more or less freely (Polish on evidently becoming subdued as the war approached). Seeing as Przybyszewska wrote a good prtion of her works in German, and thought of it as a language far superior to Polish, and knowing her personal opinions on the state of Polish cultural life versus the cultural life in Europe, I'd wager to say she was never, ever someone who felt somewhere "at home".

Nationalities aside, she was also decidedly a gender non conforming person, which is its own issue (I attach a photo of her, and it should speak for itself). I'm not making any claim about her, it's just that everything in her life points to a. uprootedness, and thus b. being a foreigner in her own country/language/life/skin. (I think a bit more could also be said about Robespierre’s sexual orientation in the plays, and how it’s adding another layer of alienation, but I think I prefer to store it away for a post focused only on the love story. The most important part here is that he doesn;t even need this, something which may well have alientaed him in the real life, to be portrayed as a foreigner in his own country.)

This is interesting to me not only because it weaves itself seamlessly into what I was talking about previously, the multirealities. I think looking at her through lenses coloured with understanding just how much of a stranger she was everywhere and with everyone, we may begin to understand the way she portrayed Robespierre, most importantly in Thermidor.

Maxime is presented as someone who does not have much in common with his fellow people, and despite working, ultimately, to preserve/save the Republic, his methods seem so unorthodox he is more than once suspected of a treason, most notably in Thermidor as a whole, but also in The Danton Case, when he vehemently disagrees with arresting Danton. This last scene is important on more than one level, actually, because the suspiscion spreads to more than just having potentially erronous opinions, he is also alluded to be gay, which is a small thing (in the universum of these plays this is like the smallest thing of all one could be "charged" with), but still, it is something which deviates from the norm, putting Maxime - and anybody who follow him by proxy - outside the circle of what is considered normal and approvable.

And in Thermidor we see it on two different fronts, which are both very unlike each other, but they tend to the same goal. On the mental level, Maxime is a foreigner, because he is not even human (he's a "sterile god", as Billaud puts it), which I discussed more broadly HERE; and he was on few ocasions compared to plants, animals and objects, making him less humane as a result. He is also very far removed from his usual social circle, both in terms of mentality - his vision spans such a distance no one else can comprehend him - and physical space - he doesn't leave his rooms, when Barere relays the news, the whole Comsal is surprised to hear he has gone out to the streets. Everybody seems to perceive him as a stranger, a foreigner, an extraterrestrial being, an unwanted element not simply because his opinions are faulty (Billaud has similar ones, yes, but what is more important - Saint-Just has the very same ones, and yet the Comsal did not want to destroy him, they only wanted to destroy his friendship with Robespierre; this is very interesting to me and I will focus on this more next time). On the much more factual, physical level, though, Robespierre is a foreign element in his own Republic, because what he has undertaken is, in fact, treason:

Showing through Robespierre that the only way to move out of a stalemate is through cheating his compatriots, and without any remorse about doing so, Przybyszewska dots the is in regards to how she saw the world. Robespierre is such a singular being, that what is a treason objectively - in him is only a hidden mean to a good end. She (probably consciously; she was well aware of the grey zone she lived in and did not mind it all that much) put him outside of any ircle he might belong to, therefore all his choices are in the same time foreign and not maliscious. It's reassuring she at least showcased what happens whena being who is not foreign (Saint-Just) tries as he might to break the fence and either let the alien element in, or join it on a higher level of understanding. Of course, by showcasing it, she only underlined the point I made. This is expecially not-cliche, in my opinion, in plays focused on one of the greatest spurts of patriotism she could think of. Admiring revolutions on one hand, and admitting in the same breath they cannot be saved from within, only from without, only through means that are doubtful at best, is an interesting choice of action, not expected from someone who made it her whole life to proclaim revolution to others.

Making Robespierre become a traitor in the last, decisive stage of his life isn’t, in my opinion, an autobiographical commentary by Przybyszewska, I think it’s much more of a blind spot for her – I don’t think she thought what he has done was traitorous at all, just seen as such due to legal technicalities. It is also a bit like a disease, in that he literally contaminates Saint-Just with his thought:

Not all of them follow Maxime so easily, though, do they? (Also, a side note: in the original, Saint-Just does not speak „matter-of-factly”, he speaks „nearly with admiration”. It changes a lot, if not everything, in what he has just said.) Not all of them are as easily picked up by the wind of new ideas, because they are all too firmly rooten in th ground; Saint-Just I find to be someone on the edge between the two states, he’s way more grounded and at home in the world than Maxime, but not nearly as much as, say, Barere. Ha later admits to following Maxime „mostly” (so not in fullness), he also insists: „you are already burning in the blast furnace of your spirit. You alone.” (so he’s not sold on the idea completely, it’s more that he loves Robespierre and is ready to accept almost everything of his’ at face value). Besides – while I don’t necessarily think it should have been understood literally – there is this one small scene, laden with symbolism:

It is, of course, about death. It is also, equally, about pulling Maxime back to Earth by someone whose head is lost in the clouds a bit less often. Death fits the story all too well, because in this instant Robespierre is tempted to die, because what he has undertaken is too much, yes, but also because he miscalculated, his ideas were too lofty and otherworldy to become applicable (and! don’t even get me started! how his plan was not destroyed by someone hostile to him, but by Saint-Just, whose only crime is being too practical).

Przybyszewska’s writings are full of such creaturs, great minds who cannot 100% find their place in this world, and, more often than not, the end they meet is death. Her other French Revolution heroine, Maud de la Meuge, is the one who scarcely avoids it, by means of a concoluted (and, frankly, a little banal) plot, but the words from this play fit here very well:

Of course, no one would dare to talk to Robespierre down so, but the thought remains. And if Przybyszewska were ever able to finish Thermidor, he would have died, too, not because his story follows the original as closely as could be done in the circumstances, but because he’s doomed from the beggining by his overgrown genius.

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#Maximilien Robespierre#robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#literary analysis#frev#French Revolution#the danton case#sprawa dantona#thermidor#saint-just#antoine saint-just#ninety-three#dziewięćdziesiąty trzeci#rewolucja francuska#pollit

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Given the departure of Hilary Mantel today, I wanted to bring this up again. After listening to this lecture I was convinced (much more than I ever had been; convinced entirely) she was the perfect person to write Przybyszewska’s biography. She understood Przybyszewska, in a way few of her scholars did, she understood her outside of the enormous shade her life put on her. She understood her on the level of mentality not many (Ewa Graczyk for sure, but other than her maybe Maria Janion) grasped.

And I am just so very sad now she will never finish writing The Woman Who Died Of Robespierre.

Silence Grips the Town - The Reith Lectures for BBC by Hilary Mantel

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tuning in to say that I have gotten into a PhD school which will enable me to become an official Przybyszewska scholar!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multirealities in Stanisława Przybyszewska’s plays

The most common critique of Przybyszewska I encounter everywhere is that she claimed her plays were a "historical chronicle" (an actual subtitle for The Danton Case), while being very obviously biased, belletrised, prejudiced etc., all in all not exactly the impartial retelling a chronicle is supposed to be. This critique permeats all that is written about her plays to the point when while I cannot exactly complain about the lack of resources focused on her (for such a niche personality she does have a dedicated group of scholars, fanalyzing her works and bringing to life all the forgotten bits from the Poznań archives), it seems to me way too much space is focused on these harsh views, and not enough left for enjoying what I consider to be a genius piece of literature.

When I say Przybyszewska was a genius, I don't only mean it in terms of brilliant literary prowess. She was actually a modern renaissance woman, talented in many fields, and if she constantly complained about not being good enough in any of them, it was only because she held herself to unbelievably high standards. Therefore it is simply stupid to assume she actually considered what she knew to be fictional - to be a chronicle. A title is one thing, believing it's true is another and I think the very least we could do in order to understand her and her works better, is to stop treating her like a child who did not pay attention in history clasess.

A small sidenote: Sandor Marai, my favourite Hungarian writer, has a knack for writing all love stories as if they were criminal cases, and the main character was conducting an investigation of sorts. Which makes it very fitting that in one of his most famous novels he introduces us to the concept of "reality versus truth". This seems counterintuitive, but I don't think it really is, and I also think this is something which should be more often applied to Przybyszewska. Too often she is being judged on the basis of having taken "too great a liberty" of assuming somebody's intentions and explanations. People act as if the very fact she wanted to give studying history a try already makes her a writer with an aspiration to be a historical writer. Now, I haven't read Albert Mathiez yet (but it's in my plans, as I don't think anybody can seriously discuss Przybyszewska without getting acquaintanced with Mathiez as well), but I doubt she wanted to write a history book, only better, only in form of a play, after studying Mathiez, much as she liked him.

All this points me to the direction of something I will call "A Prime Theory", and it's not very revolutionary, but it seems to be absolutely crucial to put it in place, because Przybyszewska is constantly being - unfairly - judged on the accordance and compatibility with the historical events, when it should not be the case. The foundation is this: the revolution Przybyszewska described is not The Great French Revolution, but The Great French Revolution'. According to mathematics for every Point, there is Point', identical to the first one but on a flipped side of the axis, so to say. I believe she has described something more akin to a parallel reality, with the general grasp on the events more or less the same that what we know from our history, but with occasional changes and differences. Therefore she did not describe the "reality" of the Revolution but the "truth" of it.

It is possible because the way Marai understood "truth" was that it was the essence, the gist of something much more than the actual chronology or honesty of a situation. The truth is much more personal and what we believe to be true, than what is factual and provable. The first and easier example would be the way she described Robespierre in regards to his physical traits. In every historical account I've read there is some thought dedicated to his fragile health and meagre posture, and Przybyszewska wholeheartedly disagrees, sprinkling small but firm descriptions that work to the contrary; any sign of illness or weakness is in her eyes onlyt emporal, besides, it's not really a weakness if it shows he has undergone (and proved succesful in the endeavour) such a multitude of obstacles any lesser man would have already given up. So even the "negative" traits she flips around so much they become "positive" in the end. They are literally being foils of their original meaning. The gnostic inspirations I have written about in the past have a lot to do with the general idea I'm describing now. The overall duality seems to be interwoven into the text, which is why I cannot treat it as if it were a singular thing. And I haven't even mentioned all the things she outright invents, like bragging about Robespierre's luscious hair (which are hidden under a wig anyway), or comparing him to a tiger or a cat or a dancer, or describing him with the help of a language which is highly metaphorical and imaginative. She is very visibly inventing Robespierre anew - why would she be accused of distorting a portrait of a historical figure, when it is clearly not THE historical figure she put on the stage?

It would also be unfair to judge her in terms of accuracy with history, because she was, after all, not a historian. I need people to understand (it seems funny to write about it, but it's been adressed so much by so many I think I really have to) she was not a bad historical writer, but a brilliant fictional writer. That her fiction resembles our reality so much is a point which still does not warrant reading her plays as historical plays in any way, shape or form. To be honest, I think any kind of factual reading of Przybyszewska's works is not a good idea, because she was so far removed from social and political life, she had so few friends or even just people she kept in contact with, I find it hard to believe she would even know how to describe actual, interpersonal relations, or political lobbies. This is more visible in her prose, but the relationships she's describing don't feel at all natural, and that is not because she was a bad writer - after all she a was a genius writer, with a talent few can match. She was innovative to the point of being incomprehensible by others, and the falsity and lack of natural feeling in the way she saw people is completely due to her lack of expierence of living in a society. This is what I find lacking in the discourse around Przybyszewska - not enough space is dedicated to underlining the fact her life was extraordinary in every aspect. Her life experience was something most people cannot even imagine, and especially this is not something we expect of a writer of her level.

I think I know where this dychotomy in perceiving her comes from: she used mechanical, detached language to describe the misery she lived in, and it seems to be a mascarade a lot of people still buys. It's the same things with the subtitle in TDC - we believe her at face value, completely disregarding the fact she was a writer, she was inventing fictional things all the time! It's like no one (not many people I've read anyway) is able to discern between what she put on display and what was really going on in her life or in her mind. I'm yet to see a good critical paper on her arguing that her perception of the world in all aspects must have been skewed because she was addicted to hard drugs. It's like no one notices it, nor the fact that she was allegedly sexually abused by her own father? There aren't that many more messed up situations than this one to find yourself in. The way she saw the world and described it in her works was surely affected by that, too. This is another argument in favour of truthfullness of these plays: she described what she felt was true, what she believed was true, what she imagined was true. It’s not a lie, if it doesn’t claim to be all encompassing turth, in short: it’s not a lie, because she said so (it only works in ficiton, but luckily for us, this is fiction!).

When I speak about "multi-realities" in her plays (a term I'm borrowing from Leon Chwistek, a painter and a mathematician living roughly in the same time as Przybyszewska, they had friends in common but I'm yet to discover if they knew each other personally) I mean, actually, that there is a multi-faceted way to look into her works. Yes, historical knowledge is good for analyzing the plays from one angle, but one mustn't stop at that. There are realities aplenty: reality of love, for one, is something she described very well. She also - mostly through Robespierre, partially through Billaud and Saint-Just - reaches out to the hypothetical future and describes possible, future realities. Her characters are not thethered to one spot, what she wrote encompasses more than what we see on the pages.

I think taking a step back when analyzing her works would go a long way. Not many people on here has read Ninety-Three, her short play, but this works as a good counterexample - in The Danton Case and Thermidor we get so hung up on the point that it surely must be reality, because all the characters are given the correct historical names etc. etc. we forget they are made up. In Ninety-Three, however, we don't encounter the same problem - I am positive there was never any princess Maud de la Meuge - and thus we are automatically able to read it as a piece of fiction.

Now that I think of it, this is another reason why it's easier to analyze in regards to fictionality her plays as adaptations, and not as the raw text. It's because the directors do a lot of additional fictionalizing for us, adding even more realitites to the already full melting pot of them. We need this abundance to see for ourselves neither of these plays are historical and it’s easier to come to this conclusion when the characters are very obviously wearing costumes, or the anachronism of the stage situation becomes too apparent.

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#thermidor#ninety-three#dziewięćdziesiąty trzeci#literary analysis#leon chwistek#idk i said a lot of words while the idea is very simple

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I completely forgot about it but if you speak Polish and like audiobooks, there is a Ostatnie noce ventose’a radio theater episode. You can safely download it or just listen to it on the site. From what I remember, it wasn’t half bad.

#ostatnie noce ventose'a#the last nights of ventose#stanislawa przybyszewska#Stanisława Przybyszewska

1 note

·

View note

Text

So I have recently read an article which included this funny phrase:

The Danton Case is a play in which the main character is not the main character at all. A great deal more of attention is focused on the prosecutor – Robespierre – than on the prosecuted dantonists.

And this is the kind of thing that makes my head spin.

Because one has to be an idiot to assume that simply because the title includes „Danton” in it, its main character must be Danton. I’d wager to say that that main character is judicial process, the case itself. Its importance, its difficulty, its inevitability, but never – its subject.

The differentiation I’m making might be less readable in English, because „The Danton Case” underlines the importance of Danton moreso than of a case, but the article was wrtitten in Polish by, presumably, a Pole, and in Polish „Sprawa Dantona” makes it very, very clear that the case is way more important, and Danton comes second. The case is never presented as a decision to be taken lightly, neither by Robespierre nor by Danton (who has just as much a say in how this will all play out). Robespierre hesitates and stalls; Danton gives up and resigns. They approach the possibility of a final and decisive showdown with caution that would not be taking place if the process they are about to enagge in were not highly difficult to judge and immenesely important; I’d wager they both know this is something going beyond them both. Yes, even Danton – in a way, I want to say he loses (in the universum of the play) because he does know this, and nonetheless makes a decision to appropriate the situation that has arisen for himself. This is a final sign he has betrayed the Revolution and for this he must die (not by Robespierre;s decision, either! I’m talking about powers to be which exist in this fictional universum, this is something Robespierre wouldperhaps agree with, if he knew – but he doesn’t).

It’s not without a reason that the main axis of the play is a confrontation. The play is actually filled with confrontations to the brim, but the one which takes the stage (and is also convenniently situated somewhere in the middle of the text) is the one between Robespierre and Camille. This is a prelude to wearing down political and personal enemies, to wear down an idea against an idea. I absolutely love how this confrontation is very central, loud and pictoresque, becasue it both prepares the ground for what is about to come sooner, but also fulfills its role in advance, Because the main process is never shown, and barely audible, and actually not that much attention is being spared to it, this one has to serve as a stand-in. My theory is that Przybyszewska deprived Danton of flashy, roaring court scenes because it was a final blow to his vanity that she could have served: stripping him down of his powerful voice and mesmerazing charisma, limiting him to a hushed voice from behind a closed door; but while this is propbably tru, or so I like to think, this is also another indicator that Danton is not that important in the play, not by a long shot. We know everything about the porcess, because this is what is important; we don’t have to know a thing about Danton – and actually, we don’t know that much. We have but one scene where he is being honest before the trial, and another one after that. He is, I think more enigmatic than Robespierre for he is not even percieved honestly, truthfully by his acomplices, thay aren’t allowed into his private spehere either, while Robepsierre, who seems to be more ethereal and otherwordly, has satellistes who at times know him better than he knows himself (that fact that Louise serves as this kind of an enchated mirror to Danton is absolutely delightful and I wish Przybyszewska had done more with her).

In every adapation that I have seen, no one has ever focused their attention on Danton either. Even by the recipients of the play, he is not welcomed as the main character. In Wajda’s movie, guillotine and death play the main role; in a play by Malabar theater, the writing process of the play is most important; in Jan Klata’s version, the decay of the Revolution takes the stage. Danton is merely an afterthought. We therefore cannot say he is the main character. He is not even the main person on Robespierre’s mind – it’s Camille. He is not Robespierre’s main concern – it’s destryoing of the Revolution. He is proven to be powerless, though not unsignificant.

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#danton#georges danton#jerzy danton#andrzej wajda

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Silence Grips the Town - The Reith Lectures for BBC by Hilary Mantel

#if you know who drew the picture PLEASE let me know first of all i would love to credit them#second of all i would love to thank them personally it is so pretty#hilary mantel#stanislawa przybyszewska#Stanisława Przybyszewska

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! In lieu of this blog becoming a bit more academic from now on, I feel the need to organize my posts in some way, so from this point onward please refer to this list, sepearting my posts thematically. I hope it will help you find what you need with greater ease.

Scene breakdowns:

Robespierre’s hypothetical suicide

Robespiere&Camille versus Robespierre&Antoine

“Camille, don’t be a bore”

Antoine has always loved Robespierre: evidence

Danton versus Robespierre

Fabre’s phrase about a jewel

“Everything allright?”

“I would like to dance”

Themes and motifs:

Creating characters on an axis

Ekphrasis

Gnostic inspirations

Przybyszewska and women

Religious references

Costumes in Thermidor tell a story of illness

Who is the main character od The Danton Case?

Multirealities in Stanisława Przybyszewska’s plays

Transnationalism

Theory of literature and critique:

Stanisława Przybyszewska literature masterpost (periodically updated)

A review of Kazimiera Ingdahl’s book

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#literary analysis#analiza literacka#academia#sprawa dantona#the danton case#thermidor#termidor

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

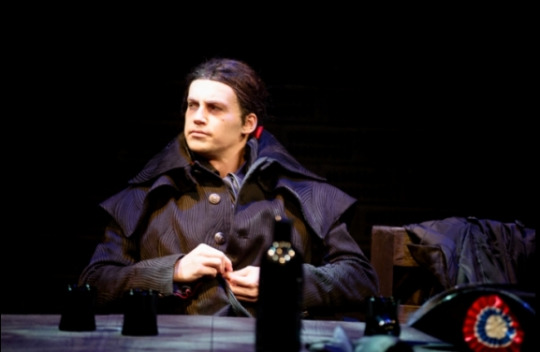

Recently I have defended an MA thesis, inspired in a large part by Przybyszewska and her creative works. The thesis’ main point was that it was a work about the destructiveness deriving from a revolution, and a large visual aspect of my work were stains of mould and rust, following Przybyszewsk’a remark in one of her letters that she had lived in conditions such as these that sometimes the only matter not covered in either of these substances was her own skin.

But her letter was a later foundling of mine, the idea that revolutions corrupt – and the she herself brought this fact to light, at times against her own views on the subject – has been on my mind since very long. While in her plays Przybyszewska tries as she mights to present the Revolution as an envigorating force, a force that can shed some life unto a corpse of a person that Robespierre in her works undoubtedly is, she seems to forget that the same Revolution was what stripped its leaders of their natural life powers in the first place. My mind is racing at once to this small, but oh-so-significant remark at the beggining of Act II in Thermidor when Saint-Just enters the scene:

And this is something in reagrds to Saint-Just of all people, the very one who in the same description is talked about as absolutely healthy. So what are we to think about Robespierre, whose fragile health is the source of so much of the universal misfortune in the universum of the plays?

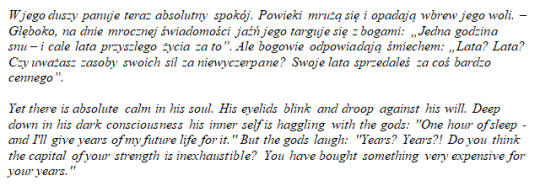

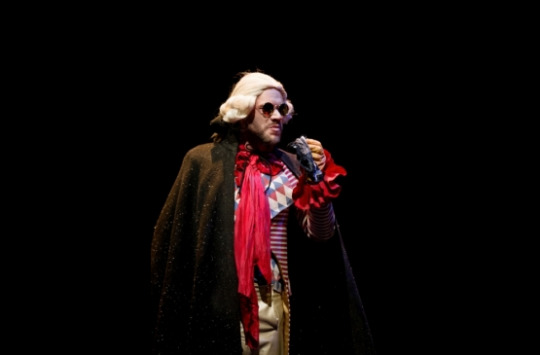

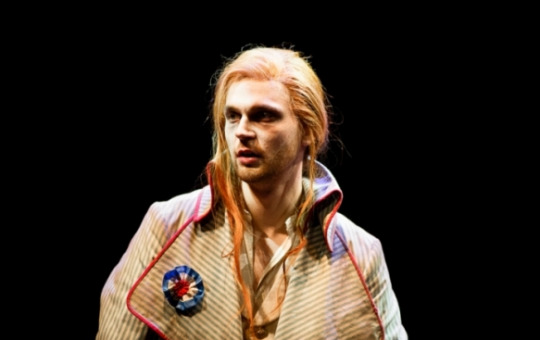

But I was also thinking about this staging of Thermidor. Everybody talks about its beautiful costumes, whose luxuriousness cuts itself away in a sharp line from he gloominess of the scenography. Everybody talks about the stage, which is supposed to look like a slaugtherhouse: the hooks hung from the ceiling and the constant, unnerving sounds of blood dripping onto the floor tell the whole stroy rather neatly in just a few brushstrokes, so to say. The first time I saw this one I didn’t catch it all immediately, because I was focused on some other changes and shortcuts the director has introduced to the text, but at some point it became evident to me: he too was creating a piece of art focused on malady. Execpt for Carnot, whose presence in the play is short and serves only to set the whole conflict up, every character in this play represents soe sort of an illness or disease.

Carnot is exempt, for few reasons. Not only he’s not a real character in the play, not a real entity with an agenda of his own, but he is portrayed as a truly just person. Someone good, even, if Przybyszewska was able to portray people other than Robespierre as good. Not only do we learn he was not responsible for the fatal order, but that had he carried out the order, the Revolution – the highest value of them all – would prevail. So he is a pawn, but not for lack of courage or wisdom (again, this is such a small, off-handed line from The Danton Case, but in Act V, Scene 2 Robespierre names Carnot as one of the only three other members of Comsal who are as intelligent as himself, something I will never tire of pointing out). And we know this for sure, because Przybyszewska really wasn’t subtle at all when creating her characters and she used malice as a clear indicator who is a bad, rotten apple and who is a paragone of virtue. So to see Carnot in midst of his fellowe Comsal company, but not actually participating in the more vile of their japes and talks is a sign that he really is not one of them, not in the mental and spiritual matters. He is the one who has the right to be at the meeting – unlike Fouche and Vilate – and yet he is the one who leaves – unlike Fouche and Vilate. He is also understandably upset with Saint-Just (upon further reflection, „upset” probably doesn’t even cover this), yet he is avaricoius in regards to insults. And while, yes, he is presented – like all of them – sanppish, it is justified and does not overcome the bouds of what is reasonable. Fouche may remark that Carnot’s hands shake, and that he seems feverish, he may grit his teeth, but this are all understandable physical reactions from somebody who is sure his head will fall the very next day. There is also the matter of his clothing – out of all of the characters, his is wearing the brightest colours, and his face looks healthier than the rest; I would say, he looks the least vampiric of them all, vampirism being, as we can guess, another word for describing something tethered neither to life nore death, something sick.

Then we have Fouche, whose behavior is the most ostensible of them all, save for perhaps Saint-Just’s. Fouche never parts with his handkerchief, and he keeps using it, as one does, to wipe his mouth, examining the fabric later on more than one occasion. This immediately brings forth connotation of tuberculosis, in oher words consumption. Fouche is indeed th one consumed the most with vengence and harsh justice, he is the one I would call the most vile of them all: in what he is saying one hears personal malice first, and only then a dedication to the state’s wellbeing. In visual terms, he’s the one who is the most stereotypically vampiric, I’d say, whose gothicness is amped up to the maximum.

I didn’t find any photos of it, so perhaps you’d have to take my word for it, but Collot’s prop of choice is also a handkerchief, but he is using it around his nose all the time. So mch so it become evident in like a minute or so, and right after that it becomes disgusting. He as a whole is not disgusting (actually hands down the second best acor in this play, and a very funny one on top of that), so it creates a dychotomy between him as a person and his actions, which of course leads to thinking his actions are artificial in some way. I think we can all agree a disease is also in a way artificial, something which we feel is not a human being’s natural state. Collot’s intrest in the contents of his nose elevates him in a small way onto some other, more naturalistic and thus less natural, plane of being. He also stops the nervous fidgeing with the handkerchief once he assumes the role with whihc he tries to break Saint-Just, which in my eyes is a sign he really is consumed wiht some sort of spiritual illness (understood very literally as some evil within him), so that he has to find an outlet to let it seep from him to the world – it’s either his nose or the words sliping from his mouth.

Then we have Billaud, who for the entirety of the play looks just as if he were undergoing some serious illness, and there is an evidence – of sort – in the pley’s text. His sullen behaviour, snappishness, taciturnity, the fact that he very, very clearly keeps some physical distance from the rest of the group almost all the time could easily be explained by what Callot calls it: a stomach upset or a toothache. A bit later, Collot again tries to bring Billaud’s behavior to order: „I implore you, Billaud, stick to the facts, or – with all due respect – shut your golden mouth.” What could be a sarcastic remark about the sudden and unnerving flows of speech Billaud presents, could very well also be a recall to the tothache: golden mouth – golden teeth in said mouth. While I myself would be the first one to agree this is a far-reaching association, it’s not entirely improbable.

Tallien is perhaps the easiest one to decipher in this adaptation’s universum. Cloaked from head to toe in a thick, warm cape, dressed in many layers, including gloves, as well wih a handkerchief and a pair of dark glasses – all this coupled with his behaviour and general mental assessment gives me an impression of someone with fever. He is quite literally a hot-headed person to begin with (very impulsive, to the point when his fellow conspirators are actually afraid he will do something stupid), so all of the other, visual signs check out. I don’t actually have a lot of thoughts about him, for somebody who takes up a lot of space in the text of the play he is pretty unremarkable, but the fever coding is something I truly appreciate.

Barrere is my favourite person in this adaptation, and the best actor, in my opinion. He is also not that easy to read, in terms of what I’m talking about in this analysis, because at first he seems to be a pretty well-adjusted person, given the circumstances of course. He reacts in a way one can expect him to react, and is actually relaxed so much (or has given up completely) that he can joke about the direness of the situation he’s found himself in. But all of this is a very good external shell, a mask of a joker he’s put on, and whener the intensity of the situation increases and he is overwhelmed by everything piling up around him, he just loses it. He’s the one who screams – very vividly – the most in this play. He is consumed by anxiety, he is, in fact, anxiety personified, and the fact hat he is the only one amog them to be shown smoking (an addiction commonly associated with anxiety) supports this claim.

Vilate is someone I might have had a problem pinning down in regards to being eaten at by something, had I not known the original text. But he too is possessed by an illness, this time it’s simply less physical than the rest of them: Vilate is whitering away by the cause of a heartbreak. Jealous to he core, being only too painfully aware he will never find favour in Robespierre’s eyes, knowing how badly he presents himself in comparison with Saint-Just, he becomes a mean, skinny ferret of a person. Altough ”whitering” might have been a wrong impression, because he does have a lot of agenda, he actively goes out of his way to either underline the special bond he feels he has, or wishes he had, with Robespierre, and to make a mark in the latter’s life. But all is in vain, for after all he is a weak, miserable person (his constant weeping is another thing that points me into the direction of a heartbreak; now that I think of it, he is the only one portrayed with very slim figure and long hair, thus making him a little bit more stereotypically effeminate; something done in regards to Saint-Just as well, and Antoine is Robespierre’s love interest) and despairing, and all that he is left with is a broken heart.

Saint-Just is an interesting specimen, because his malady is something completely added by the staging’s creators and yet it makes a perfect sense. It is also way more, shall we say, external than the rest of the aforementioned men. I couldn’t find a photo showing what I’m about to describe, but... at the beggining of Act II, Saint-Justs feign indifference to all the is being said around him, and he does so by powdering his face. This of course has a symbolical meaning, it is putting up a facade no one can see through or quite literally assuming a second face. He does spend a lot of time powdering his forehead though, and when I saw this, I was immediately struck by the connotation with the mark of Cain. Why would he be Cain in this situation? Because in Przybyszewska’s version of history, Saint-Just and his fatal decision to disobey the military order is a far-fetching, but pretty direct cause of the fall of the Revolution. He is an inadverent murdere of the whole of the nation he was sworn to protect. He is also not ill in any way (once again, the quote: One thing, however, seems improbable: that he should be healthy. And yet, he is.), but he is the furthest away from being well.

The last, and most important one, is of course Robespierre. Because Robespierre is not ill. Robespierre is dead.

He has been described as a watchman over a corpse, of course, but he seems to be well present and alive – if barely so – in the lives of his enemies. This life, however, seems to be a life from another side, a different, more spiritual and mental form of life, nothing that would resemble a healthy, robust liveness. And this adaptation captures this so well: he is a ghost, haunting the entirety of Act I, and half of Act II, and when he appears, his deathly pallor, his blind eyes (the dark circles of his glasses, which he doesn’t take off for a very long time, resemble stones put on the eyes of the dead in ancient times), his carefully cultivated fashion choices (in many cultures people are never as well dressed, as when they are being dressed for the burial), his cane with a skull on top – all of this evokes death in the audiences’ minds. He is death personified. By not letting Saint-Just in on the secret about why the military failure is a necessity, he inadverently brought the same vapor of death unto the nation he knows is in his care. He gambled with their lives, for he has none himself, not anymore.

There are other things that could be said in regards to life, health and death in the play’s universum, but I think they are all well known to anybody who has read the text. Especially in regards to Robespierre, all that is ever talked about is his health, and everything that matters is somehow connected to his wellbeing on all levels. But I wanted to only focus on the more visual aspects, native to this one particular adaptation and I hope I have managed to bring to your attention how closely connected to illness and death all of the characters are.

#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#thermidor#the danton case#sprawa dantona#antoine saint just#saint just#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#billaud#collot#fouche#barere#vilate#tallien#literary analysis#analiza literacka#theatre analysis#analiza teatralna#death#illness#disease#frev#french revolution#the french revolution#la revolution francaise

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[x]

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#i actually love these#and a 'mathematical literarian' describes her So. Very. WELL.#pollit#polish literature#literatura polska#I did translate them to english in the description just click on the photo

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anka Leśniak, Zastrzegam sobie wyłączne posiadanie swego życia, 2016 [x]

So far the only artwork so directly inspired by Przybyszewska that I know of. Named after Przybyszewska’s credo: I reserve for myself the full right to my life. Coincidentally, also an installation focused on degenerated urban tissue and decay (there is simply no other way to understand Przybyszewska as a person and as a writer).

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yes I do!

And I have a more or less pinned post with links to various books about the plays/the author, in English as well, and among them: the link to the majority of the plays in English. Enjoy :)

where did you get an english translation of the danton case?

Bołeslaw Taborski did a translation for Northwestern University Press! And here on tumblr @sprawa-przybyszewskiej posts translations and research

4 notes

·

View notes

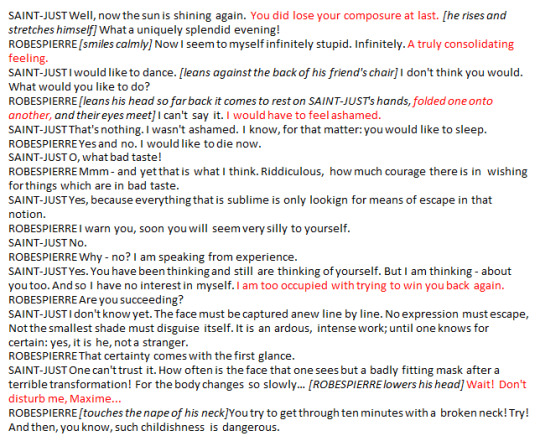

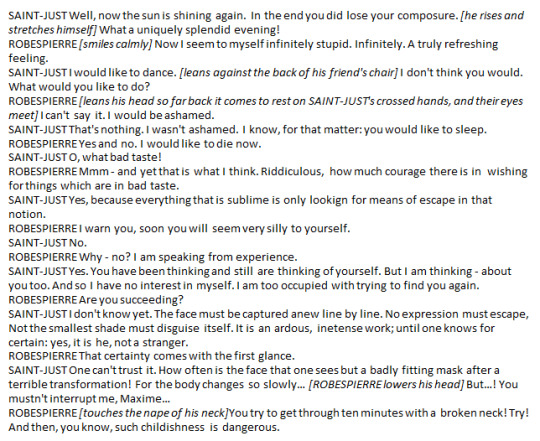

Photo

So the day has come and I will finally put my hands on one of the most beloved scenes from Thermidor.

I would like to dance scene first captures our attention by being a first clear instance of a respite after an over hour long, increasingly more intense monologuing by the Comsal. I would argue, that this is not the first one, but that one is hard to miss, as it’s soemthing which happens between the lines and more in the stage directions/actors’ expressions and is easy to miss or to not include in a staging altogether. This one is, however, refreshing and calming without any other drama going on between the phrases.

The first thing, which in my opinion makes it standout from other „nice” scenes from either The Danton Case or Thermidor is that it truly loses it grandiloquent tone. When in TDC Robespierre talks with Saint-Just or when he tries to reach out to Camille there is alway a lot at stake, and their is always some or other ulterior (not necessarily: bad) motive going on symultaneously. Here the issue had been resolved completely right before this scene – which makes it right, I think to call it a separate scene in its own right. Yes, Przybyszewska did nothing more than to divide the play in two Acts, but I think it’s mostly due to the play being unfinished; if she had sufficinet time to get back to it, I’m sure she’d put some other system in place (the room doesn’t change so perhpas she left it as a continous streams of „scenes” rather than divide it, as to not break the unity of place? Mayhaps, but I still think the division is visible and barely seamless).

First of all, I’d like to point out, that while all in all I do like Bolewsław Taborski’s translation of this scene (I have it memorized and it really flows from the tongue very well when spoken), there are few points in which I would have made small changes (marked red). This is becase sometimes the meaning of the whole phrase lies in either this or that word, and the difference is small in size, but absolutely crucial.

· You did lose your composure at last. vs In the end you did lose your composure.

Here it is more important that Robespierre’s tensions boiled in him, and that Saint-Just egged him on to the point of an outburst than the outburst had happened at the end of something. It shows us that these emotional turmoils do exists in Robespierre and torment him as much as they do any other man, but that he doesn’t let it show on his face, unless he’s being pressured by someone who knows what to say exactly and which buttons to press to achieve the goal. It also workes much better in conveying a supposedly smug expression on Saint-Just’s face, a tone which we can assume is triumphant, while Taborski’s phrase make it look more like a calm recounting. Here it begins to unfold in front of us that Saint-Just isn’t immovable, that he is in fact quite an easy going person when faced by no one else but the person who knows him most closely and intimately.

· A truly consolidating feeling. vs A truly refreshing feeling.

I admit that this one is mostly a personal choice, becasue in a dicctionary, pokrzepić is, in fact to refresh. But as a native speaker I just know that pokrzepić is less ethreal, it’s in a fact a very grounding, calm and solid word. It works as a contrast between the increasingly playful vocabulary Saint-Just presents and the still calm and more cautios about displaying emotions Robespierre. This is a tiny detail working as a characterisation.

· Hands folded one onto another vs crossed hands

This one, in turn, seems to me to be pivotal. Hands which are crossed send a message of denial, anger, refusal and so on. Hands folded onto one another are more about being calm and at ease, and about acceptance. This can still be resolved through proper stage movements, but I’ve yet to see it done properly (HERE I talk about why the hand folding and head leaning back is extremely important).

· I would have to feel ashamed. vs I would be ashamed.

The difference is small, but striking. You feel ashamed out of your own volition (even if it’s influenced by the environment), but if you have to feel ashamed, does it not mean that you don’t necessarily see the need for shame, but that your environment does and is forcing you into this emotion? That’s the way I see it and in my opinion it subtly kets us know that while Robespierre, for one, sees nothing wrong with the situation currently unflding between the two, he knows it would not be met with proper understanding from other people. I may be reading too much into it, but I would have to see the German original.

· I am too occupied with trying to win you back again. vs I am too occupied with trying to find you again.

So this allows us a glimpse into the untold life behind the curtain that Robespierre and Saint-Just have – and share. Zdobyć literally means to win, i’s something you could say about a prize. Finding (even finding agains) doesn’t have the same air of grandeur about it, finding may be accidental, winning, however – is something achieved through a sense of purpose. We now see in its entirety that Saint-Just isn’t taking any of this lightly, no matter his smile or his playful expressions. He has won Robespierre in the past, and then he’s lost him, and now he is adamant to win him back again. This is no small thing – this is his life purpose, his prize.

· Wait! Don’t disturb me, Maxime... vs But...! You mustn’t interrupt me, Maxime...

Here the difference is again pretty optional, but I like the personal feeling my version evokes, the familiarity/intimacy. By removing mustn’t we remove the tone of an order, something which is cold and distant. Yes, Saint-Just is disappointed in Robespierre’s reaction (even though, if you had read the post I had referenced, it is completely understandable), but that doesn’t mean it offends him in any way, therefore there is no need to assume a cold pose.

Now, with verbal details out of the way, I would like to focus on the tone of the scene as a whole.

When I talk about intimacy, I’m being very serious and straightforward. While I am the last person to make everything about sex and even rarely see things in a sexual context, here I had never any doubts that Maxime and Antoine spoke in code – if we can even say it was a code, for it was all so plain.

First of all, I’m not even talking about the „you would like to sleep” bit, because while it didn’t call for a separate bullet point on my list, the expression that was used in Polish was rather „to fall asleep”, without any sexual innuendos. This is the familiarity at work, not intimacy, it is a reference to Robespierre enormous tiredness, one of which Saint-Just was all too often a witness to. Antoine’s heart and mind ar at ease at the moment,s so he would like to extend this calmness to Maxime and offer him – even though he knows it will more than likely be refuted – some of this relaxation, too. What he doesn’t expect, I think, is that Maxime takes him up on that offer but with a twist, and turns a conversation which could have remained friendly into something from an another, flirty level.

I’m assuming that everyone and their mother already knows this, but la petite mort is an expression used in French to describe an orgasm/a feeling after an orgasm. I’m not saying that by saying that he would like to die now Maxime is making a direct request/offer, but he sure is making a clear enough reference – which is why I always imagined Saint-Just’s reply to be said with laughter rather than completely seriously. Not to mention, the rest of this exchange makes another dig at it: I will argue that „a sublime thing looking for means of escape” is another sex reference, or at the very least could be read that way. This is of course too much for Maxime, whose prudish nature in this regard was already explored at depth in The Last Nights of Ventose.

The last thing I would like to talk about is a small, internal reference which I think this scene is making:

When at the end Maxime complains about trying to get through the conversation with „a broken neck” I think it serves (even if inadverently) two purposes. One is, of course, to cut the conversation short and get to the bottom of the political intrigue, which is what is more pressing and interesting to him than any flirting could ever be. The second, however, brings to my memory the scene at the end of The Danton Case, where Saint-Just tells Robespierre that he has broken his spine.

ROBESPIERRE [His legs give way under him. He sits at the edge of his bed.] Oh, you have finished me, you know.

SAINT-JUST [leaves the table, walks aimlessly] And you have broken my back.

In the original he actually says: And you havebroken my spine. A spine is, of course, an extension of the neck in terms of anatomical built, and so I believe these two instances should be compared side by side. It is very telling (though I may not yet know what it is exactly they are saying) that Robespierre metaphorically breaks Saint-Just’s spine when they are fighting, but Antoine, in turn, (a bit less) metaphorically breaks his neck when they are makin up. Is this a foreshadowing, that no matter what they are doing and no matter the turn their conversation is taking, they are doomed?

#Christ has risen - indeed He has risen.#Happy Easter everybody!#frev#french revolution#the danton case#sprawa dantona#l'affaire danton#thermidor#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#antoine saint just#maximilien robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#rewolucja francuska

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pssst! The I would like to dance! analysis is coming out today :) Happy Easter!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I promise everybody this blog isn't dead, I simply have a lot of work to do.

But, having Easter break in mind, which of the following ideas would you be most interested in reading?

The first part of Noli me tangere!, which is about Robespierre's relationship with others. The "other" in question is still debatable, but I had Eleonore in mind.

An analysis of the ending of Robespierre's and Camille's fall out ("not one word too many").

An analysis of the "I would like to dance" scene.

A comparison between Saint-Just's and Robespierre's argument in The Danton Case and their making up again in Thermidor.

#if you speak out your mind on this it will sway me in the direction because i truly have so little time now but the ideas are still there#frev#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#l'affaire danton#antoine saint just#maksymilian robespierre#maximilien robespierre#probably deleting this once I post but for now i'm tentatively looking for a place to start

11 notes

·

View notes