#przybyszewska

Text

A List of Relatable Things Stanisława Przybyszewska has done/written:

Studied philosophy at a university for one semester until "nervous exhaustion forced her to abandon her course"

Dated her letters by the French Revolutionary Calendar

Was known to often be humming La Marseillaise

Called Camille a twink in her play (okay, to be fair she used the word 'ephebe', but I'd argue that is as close to twink as you can get in the 1920s)

Worked at a leftist bookstore (and was subsequently arrested for it)

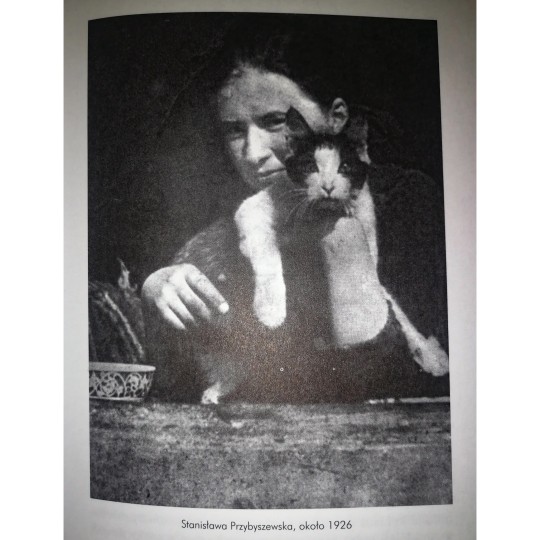

Took a stray cat from the street which at one point "was the only creature keeping her company"

Complained in at least two letters spanning over 3 paragraphs about a group of loud people playing football near her windows ("For the past forty-five minutes they have not been roaring, they have not been howling, they have been simply shrieking (...) like animals being slaughtered. Screams of that sort must be frightfully tiring for the vocal chords.")

When she wrote "I must write in order to be able to think. As a matter of fact, I am a remarkably unthinking person. Well, of course, that holds true too when I'm talking. But if I don't have either paper, or a human ear to listen to me, then I'm no more of a philosopher than a cat is."

1 + 8 - since I study philosophy at uni & am currently working on my thesis, these felt particularly relatable. I'm not more of a philosopher than a cat is definitely hits. Kind of want to put it in the preface.

2 + 3 are things I may have done myself before (okay, not letters but a diary, but it counts, right?)

7 - as someone who struggles with misophonia, I felt s e e n.

4- I'm sorry guys, I had to. But as someone who frequently asks herself "Are you really calling 30-somethings who have been dead for more than 200 hundred years twinks?", this felt like a vindication of sorts.

Also- I feel kind of conflicted about making this types of Tumblr posts about her since her work is really profound and serious and I have a sneaking suspicion she would have not appreciate them. At the same time, she has been living in my mind rent-free for the past week and this is a way to cope I guess?

SOURCES:

1. A LIFE OF SOLITUDE: STANISŁAWA PRZYBYSZEWSKA

Author(s): JADWIGA KOSICKA and DANIEL C. GEROULD

Source: The Polish Review , 1984, Vol. 29, No. 1/2 (1984), pp. 47-69

2. BBC Reith Lecture Three: Silence Grips the Town. Dame Hilary Mantel, 2017

3. Stanisława Przybyszewska: A Brilliant Playwright Preoccupied With Revolution. Alexis Angulo. Retrieved from: https://culture.pl/en/article/stanislawa-przybyszewska-a-brilliant-playwright-preoccupied-with-revolution

4. Przybyszewska, Stanisława. 1930. The Danton Case.

#french revolution#frev#frev community#stanisława przybyszewska#przybyszewska#the danton case#frev memes#history#literature#also go read the articles they are excellent#but obviously incredibly sad#camille desmoulins#20th century literature#misophonia#1700s#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#academia#it actually took effort not to put “daddy issues” on there#I guess it's now in the tags#oops#hall of fame

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippeaux is the real chad here.

-from "The Danton Case" by Stanisława Przybyszewska

#the danton case#Stanisława Przybyszewska#Przybyszewska#frev#danton#philippeaux#desmoulins#l'affaire danton#french revolution

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

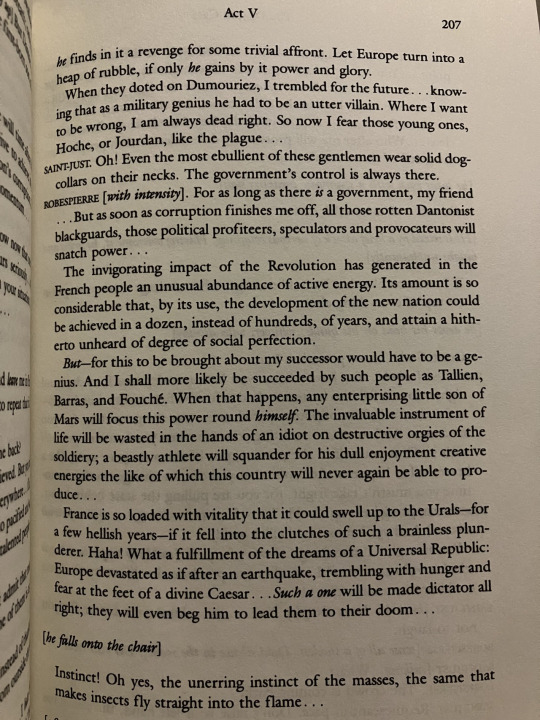

Reading The Danton Case and I'm so ??? at this scene

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Sir,

Mr Augustyński has kindly informed me that you have read my one-act play [93] and decided that staging it is impossible. I'd like to point out that if Mr Augustyński asked you to accept the play - as his letter seems to indicate - the idea certainly wasn't mine. I requested him to find out what had happened, not to promote the play.

I'm not at all surprised that you haven't sent back the script to me yet - I'm not surprised, but I won't tell you the thoughts I have about you as day after day I confront an empty mailbox.

Stanisława Przybyszewska, Letter to Leon Schiller, 7 Dec 1927

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

She reserved for herself the full right to her life

A small note at the beginning: the text below was what I presented during my first ever scientific conference this month. The main theme of this event was types of artistic methodology and research, and it was directed at people who knew exactly nothing about Przybyszewska, therefore the readers of this blog probably know all fo this already. I still feel like putting it out there, because I care about spreading awareness of Przybyszewska’s existence and uniqueness any chance I have.

Stanisława Przybyszewska remains to this day relatively unknown, as was the case for the majority of her life. She was painfully aware of it, especially since she has grown up by the side of her mother – Aniela Pająkówna, a celebrated Polish painter – as well as growing up in the shadow of her extremely popular father, Stanisław Przybyszewski, a writer whose fame only few could have matched back in the day. There is no surprise then, that little Stasia from very early on decided not to settle for anything less but to be celebrated as a genius she always felt she was.

Her life was marked by hard work since the very beginning. Given her mother’s unlucky circumstances, she was a witness to how a woman can – and must – survive on her own, with a small help from friends and family, but mostly making living through her own works. It was in a time and place where this much independence was not yet taken for granted for women, and it surely reflects in Stanisława’s later life. Her mother made sure Stasia was extremely well educated when it came down to artistic subjects, taking her to exhibitions (which in the 1910s in Paris were understandably on a very high level) and paying for private lessons in painting and violin; she also always encouraged her to write, and send the fruits of her labours to the distant, mysterious father. Because Aniela was dying from tuberculosis, she made precautions for Stanisława’s fate and secured mentors and guardians from among the family members and close friends, of whom she was sure they would continue pushing her daughter onto the path of greatness.

It did pay off. Stanisława was a very well educated young woman, whose only fault at the time was that she was too interested in too many subjects at once and so she tried her hand at everything, unable to decide on a career path for longer than few months. In her defense, it has to be said that as a child she proved to be brilliant at everything she tried, from painting, through philosophy, to mathematics. Aged 13, she wrote this in a letter to her aunt: Luckily I'm not as bored as I used to be, I found two things to do: [one is] journaling, the second one is easy - [���] drawing [passers by]. It requires a lot of craftsmanship, which I would like to train myself to possess. Beside that, I'm studying anatomy for artists and would like to combine fine arts and science, namely electrotechnics and mechanics, but it's almost impossible. I do some sports with monsieur Geroges, namely running, gymnasticks and a bit of fencing. But that in itself isn't much, I don't know enough about fencing yet. Having received her education in various european countries, she spoke several languages and she thought about becoming a painter, a violinist and – naturally – a writer.

While this last choice seems to be heavily influenced by the mysterious on-and-off presence and absence of her father in her life, it was the best one she could have made. Not many of her drawings and paintings have survived, but those which did show off her creativity rather than enormous talent – the later lack of artistry could also be an effect of prolonged morphine usage. The epoch in which Stanisława was growing up was filled to the brim with brilliant painters of both genders (it was a golden age for female painters in Europe, who started gaining artistic and personal independence at a rate unmatched by any previous period in history), the competition was fierce and she surely would not have gained recognition for her visual works. In fact, she knew it herself, having dedicated the entirety of the year 1926 to painting only (setting writing aside, even writing for solely financial purposes as a feuilletonist to a newspaper), but to her dismay, she realised she had not had sufficient talent to lose herself in fine arts. And if she had chosen violin and became a musician, she would not be remembered for much longer after her death. The ephemeric nature of music, especially in times with limited recording technology, would not play in her favour. Thus, choosing literature and theater was the surest way to establish herself as a prodigy.

Due to the lack of family ties she inadverently gained independence at a fairly young age and had to make a living somehow. She tried working as a teacher, later as a secretary and a clerk in a bookshop, but all of these mundane tasks bored her to death. Aware of her exceptional talents, she felt she was wasting away the potential she could exhibit some other way. Luckily for her she did not care for the money – and even more luckily for her, her distant family cared about her and sent her small allowance, just enough to get by. This enabled her to fully immerse herself in the creative process of researching, writing and correcting the texts she wanted to publish.

What were the prevalent factors in making Przybyszewska a great author? In my opinion, a lot of this boils down to strict work ethics. When one takes a glance at her life, it’s clear she was not necesarily predestined to become great: born a bastard, orphaned in young age, betrayed by her father (who sexually abused her, emotionally manipulated her and introduced her to morphine, resulting in her lifelong addcition), widowed after only two years of marriage – none of this set her on an easy path. Were it not for her aunt Helena Barlińska, Przybyszewska would not have suffficient means to live, nor another person to confide in through letters. Because of her reclusivity and uncompromising way of being, she did not have many friends, and she usually managed to lose the ones she had made. It was as if she did not care at all about what others thought of her, or in what conditions she lived in (and these were abymsal), if only she was permitted to work.

After years of being a gifted child, a good student of various schools and private classes, she was well equipped to discipline herself into a literal working machine. This aligned perfectly with her views on humanity and personhood – she maintained a vision of them that was decidedly mechanical, or even robotical. She demanded of herself an inhumane amount of focus, regarding this as the only sure way to achieve greatness. Soon after her husband’s death in 1925 she cut almost all of the ties with the society and set on the path to become an impeccable author the only way she knew how: by putting herself through a regimen of hard work. I shall never be free, do you understand? Never. A succession of twenty-hour day of ever-heavier work until I die. [...] Today I have no personal life anymore. I cease to be a man: human sensibility, human feelings, desire – all these gradually wither and fall away in that hellish temperature of concentrated effort. I am becoming an impersonal, monstrously expanding, inflamed brain. Today I can see what is happening to me because I have time... and I feel strange. said she through words of Robespierre, her most famous character, but she was expressing her personal views on the matter in the same time.

The date that marks a shift from her previous actions (when she still tried numerous „normal” jobs and hoped for a financial independence from her family) is beginning of 1929. It is then that Przybyszewska writes to her aunt for the first time after 3 years long period of silnce: I have decided on what my profession would be. Two years ago; rather early, isn’t it? – I could be a writer, or nothing at all. Because, aside from this, I am not fit to be anything else, not a cook, nor a stenographer. [...] All questions aside, I flirted with literature ever since I was seventeen, but until I was twenty five I had serious doubts. My own works were not trustworthy enough. Now I am certain and will act, not only feel, by it. It means that I reserve for myself the full right to my life – this means Liberty with a capital L – no matter the price. And it is quite steep. Firstly and foremostly, it’s my dignity. And comfort. And safety. [...] I know from experience that one has to have their full powers at their disposal, if one wants to work in a creative field. [...] Therefore I balance myself just above the surface of Hades by means of miraculous acrobatics and divine interventions in the eleventh hour. Ever since this day, she fully proclaimed artistic independence rather than any other – looking at it from another side, her deciding on becoming a writer as her sole occupation, meant becoming a parasite as well, passively preying on her benefactors.

There is no doubt, though, that she took her decision very seriosuly and turned out to be a relentlessly hard worker, which can be proved by her epistolography. She has left as her legacy only a handful of creative works, but it’s letters where her natural talent shone. Thanks to professor Stanisław Helsztyński they were all gathered and published some 30-40 years after her death and can now offer a glimpse into her everyday life. Her life – which consisted of little more than writing and rewriting her own works, or pondering over them; she wrote sometimes about everyday matters, especially political ones, but rarely with genuine interest. Her world was then small and narrow, but incredibly deep to plunge into, which created a perfect space for honing her craft.

It is from her letters that we know what her normal day of work looked like. Her American biographers, Jadwiga Kosicka and Daniel Gerould sum it up this way: The pattern of Przybyszewska’s daily existence was rigorous but dreary: eight to ten hours of serious work (her artistic ‘output’), done almost entirely by night, occasional trips to a nearby grocery store to buy essentials on credit [...] visits to her German doctor Paul Ehmke to ger prescriptions for morphine, without which she could not concentrate or write, ventures out to the tobacco shop to get cigarettes (another addiction), or to the newsstand to buy papers, which she despised but could not stop reading, and rarer outings to the movies (she [...] found film superior to theater [...]). It is worth noting that even if she spent ‘only’ ten hours on the physical act of writing, almsot all of the other actions she undertook during the day were aimed in one way or another at bettering herself as an artist; even morphine she considered absoltely necessary for writing, while she abandoned such ‘luxuries’ (which any other person would consider ‘necesities’ rather) as kerosene for her stove. And in fact, the life described sketches in just few lines how self-denying her existence was.

Another part of a work-oriented life is undeniably studying. In the case of Przybyszewska, whose works were based on a specific period in european history (the Great French Revolution), this aspect was even more important. She researched Robespierre in times when it was in fashion to demonize him in order to jusitify the Dantonists. She studied in depth Albert Mathiez’s history books, the only ones who at least partially spoke to her convictions. Out of all of numerous plays about either the fall of Danton or the fall of Robespierre that had been written up to that point, she was the first to present a thouroughly Robespierre-centric point of view. She felt so misunderstood and alone in this position, she was often frustrated with her studies, but nonetheless, she persisted and almost all of her works depict this period of history.

How was it that a person so completely focused on work alone has produced not much more than what we now know to be her texts? Only three dramas, only one of them celebrated and fully finished. It’s important to say, too, that despite their excellency, she faced refusal after refusal when she tried to show them on stage and during her life time it looked like she would never be able to do it (the only premiere she had she did not even go to, sensing that the director did not do justice to her vision, and the play was taken off stage in a record setting time). A handful of short stories, which were not published in fullness until few years ago. Even lesser amount of sketches and paintings, which were never exhibited at all, and are stored away in the national archives in Poznań, never to be seen. The regimen she put herself through was her final undoing. She kept losing herself in her work, literally going mad whenever her cheap, rusting typewriter was in need of repairs, but did not agree to any help, including medical (after refusing to go to a drug rehab, she lost the last source of income she had). Just like characters from her works, she finally lost the battle of intellect&spirit, and flesh – in this instance: weak, plundered by addiction and malnutrition flesh – finally gave in. She died of an unknown cause, of which the most probable was freezing to death in her own apartment.

#thank you for reading! I know it's not anything exciting for anybody who already knows and likes Przybyszewska#my next text I hope I will be able this month as well and it\sgonna be either about Mary Magdalene-ness of Eleonore#or about the role of grey eminence Saint-Just plays in both dramas#stanisława przbyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#przybyszewska#artistic research#reseraching this i also learned a bit about Stanisława's verious siblings and her elder brother seems FASCINATING fr fr

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

My HERO. You, whom I know as God, only through your miracles Przybyszewska translations 🙏🏽🙏🏽🙏🏽🙏🏽

After saying that, there is no other way for us but a friendship ceremony 🤭

#the pleaslure is mine#i'm glad my girl is getting the attention#przybyszewska#last nights of ventôse#stanisława przybyszewska

18 notes

·

View notes

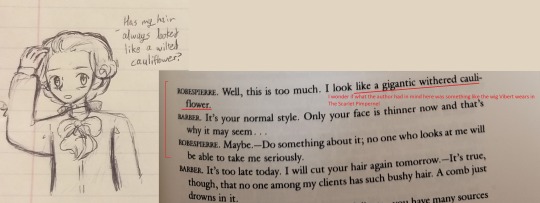

Photo

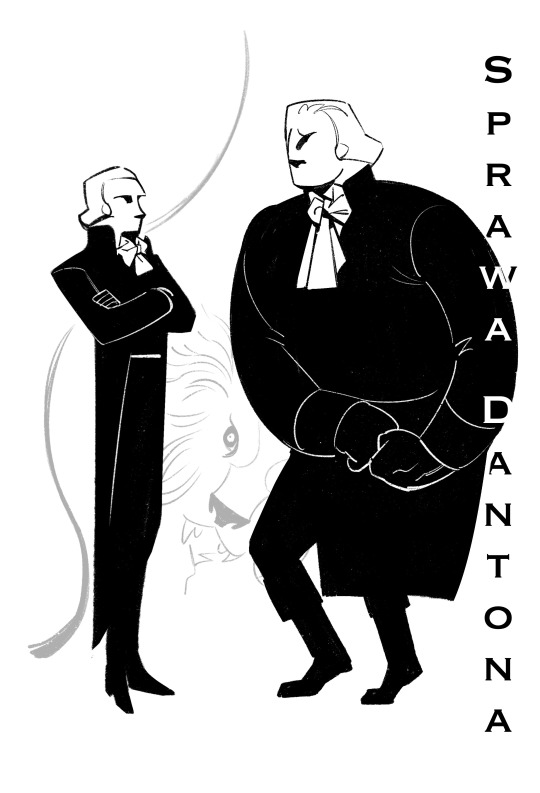

I was reading The Danton Case and wanna play with the steel-like (razor) shape concept a bit

end product

#The Danton Case#stanisława przybyszewska#french revolution#frev#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#art#my art

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

#yes the indulgents were actually to his right. but.#the danton case#stanisława przybyszewska#french revolution#graphic design is my passion.#op#clearing the drafts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

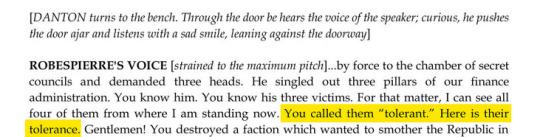

i cannot hold myself together anymore, friends, i have been living in the future that is controlled by the late danton.

(also saint-just really had to hear his prophet of a boyfriend tell him how difficult it will be without the two of them did he...)

#frev#french revolution#stanisława przybyszewska#the danton case#(;~;)#i should not have been rereading this on danton death day

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

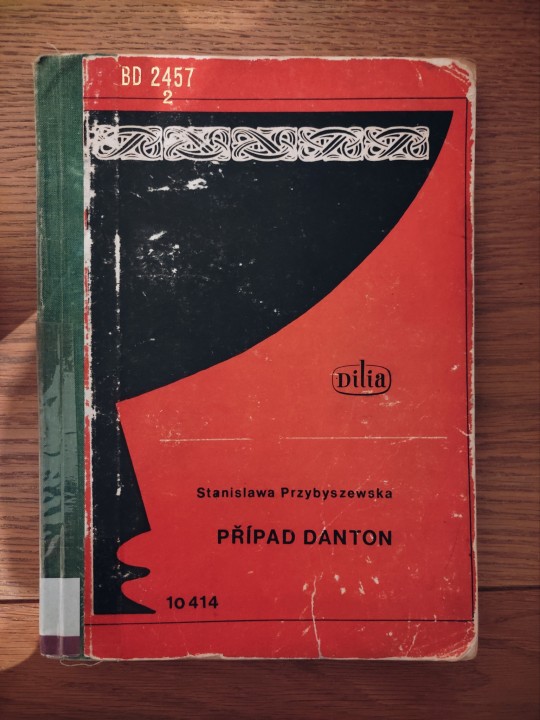

Managed to get my hands on a copy of Przybyszewska's play The Danton Case from Prague's central library!

Literally so thrilled. Started reading it today and I have a lot of thoughts already. I'll probably try to write down stuff relating to the actual content in a later post, but so far:

The fact that it's a copy from the 70s written on a typewriter somehow already makes it feel so special. Really wonder how many people had borrowed this copy before me

It's written in Czech, obviously. Can't say how good the translation is, but if the original is in Polish it couldn't have been that hard to translate I think, since both languages are quite similar?

The only slightly odd thing is that the revolutionaries keep calling each other "soudruzi" (comrade in Czech) which to me as a Czech feels kind of anachronistic? Like the word has a pretty strong connotation in our language given our history. Would love to know how it is in the Polish original

Definitely need to find more info on how and why it got translated into Czech

I know I said I won't address the content in this post but the first scene with Robespierre and Eleanor really was something else. I mean I wasn't sure what to expect, but it wasn't... that. Nightmare fuel for sure.

But yeah it's excellent so far

#stanisława przybyszewska#history#frev#french revolution#literature#danton#the danton case#maximilien robespierre#saint just#Przybyszewska#theatre#historical fiction#incoming rant

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

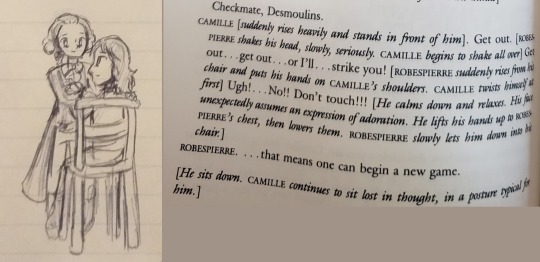

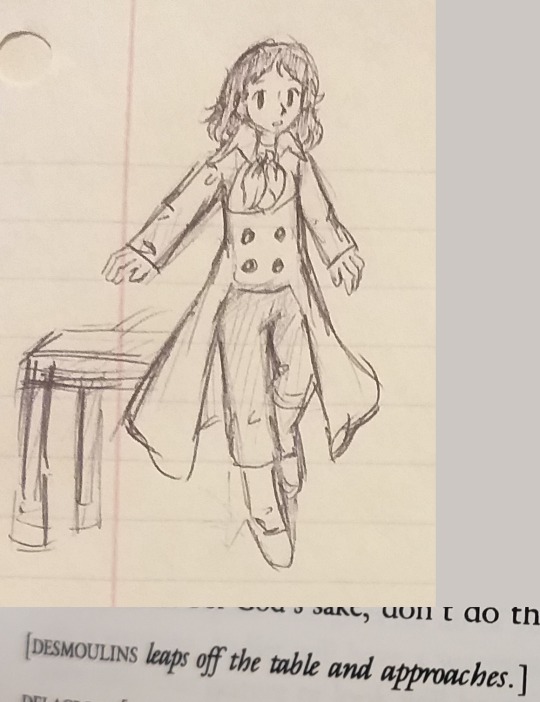

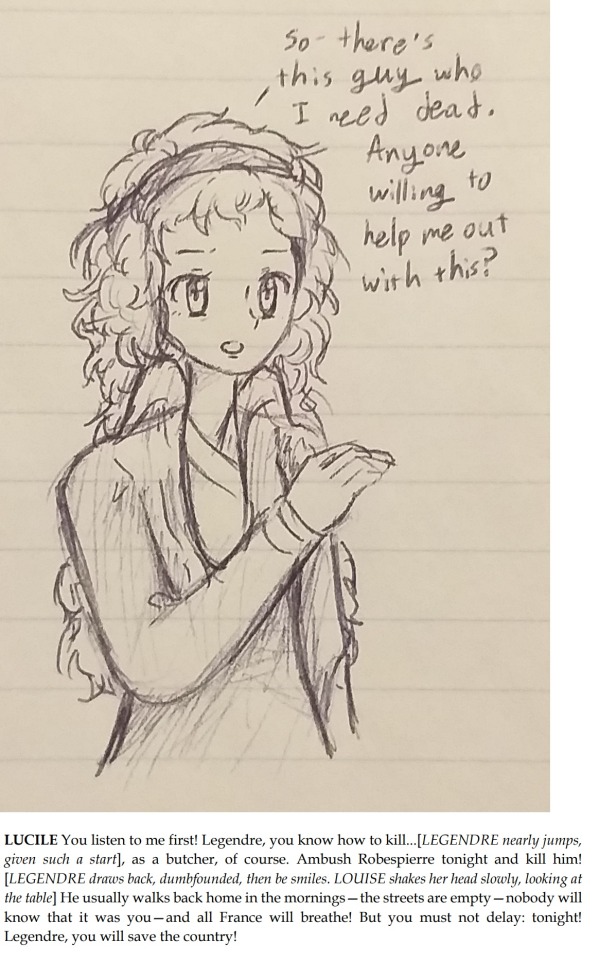

I illustrated some of my favorite scenes from the Danton Case (+ one from Thermidor, which I just started reading). Reading the play was a wild ride, and it was really enjoyable. It made me somehow feel even sadder than I already did for people who have been dead for more than 200 years. Also, I was surprised to find out that this was what the 1983 Danton movie was based off of, given how different the two are.

Along with that does anyone happen to know if there exists an English translation of the Last Nights of Ventose, or just any other of Przybyszewska's works?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ninety-three, Stanisława Przybyszewska, tr.@hhorror-vacuii | The Possessed: At Tikhon's, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, tr. S.S.Koteliansky & V. Woolf

#Josse contemplating ascetisim is not a virtue because it would be a crime to lead a sterile life like this. HELLO#Hello. HELLO!#virginia woolf translating dostoyevsky! a dream come true#the possessed#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#fyodor dostoyevsky#fyodor dostoevsky#demons#the devils#biesy

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stanisława Przybyszewska with a cat, 1926

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Glares Irishly]

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

Finally got my copy of the Danton Case and Thermidor and already ordered A Life of Solitude. I wish I could read everything she wrote.

Przybyszewska's writing is incredible! I am so happy to hear about people interested in her works, they are totally worth it!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

He never let us kiss his hand. And to be so familiar with him as to kiss his cheek – was altogether unimaginable. Besides, I doubt I would have ever dared to touch him. But I did manage to steal a pair of gloves, which retained the creases of his fingers and even a mysterious smell of perfumes. At night I sneaked out of bed and I buried myself in these gloves, reveling in this dying echo of an aroma, I couldn’t separate my lips off of them – night after night I would spend hours praying like this.

Ninety-Three, Stanisława Przybyszewska (transl. by @hhorror-vacuii)

My true God was my father. At communion it was my father I received, and not God. I closed my eyes and swallowed the white bread with blissful tremors. I embraced my father in holy communion. My exaltation fused into a semblance of holiness. I aspired to saintliness in order to conceal the secret love which I guarded so jealously in my diary. The voluptuous tears at night when I prayed to God, the joy without name when I stood in his presence, the inexplicable bliss at communion, because then I talked with my father and I kissed him.

Winter of Artifice, Anaïs Nin

15 notes

·

View notes