#sprawa dantona

Text

Sometimes I go on tumblr just to look at that one dead fandom with 10 posts on its tag (I've seen all of them a hundred times) and I just kind of

Stare.

#ziemia obiecana#niebezpieczni dżentelmeni#wesele wyspiańskiego#błagam polskie fandomy odezwijcie się#sprawa dantona#to akurat nie jest aż tak martwe#fandom frev jest jednak cudowny#polishpost#sort of#whatever#not a jeeves and wooster post#definitely not that#the fandom is thriving#and I thank you for that

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrzej Wajda wanted Camille (Olgierd Łukaszewicz) to wear only a bathrobe and to open it during his conversation with Robespierre (Wojciech Pszoniak) in his staging of The Danton Case, but the actor didn't agree.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

ROBESPIERRE I need you everywhere... Oh, if only I could have fifteen of you, Saint-Just! You, who pacified and won over rebellious Alsace - without bloodshed!

Stanisława Przybyszewska, The Danton Case

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multirealities in Stanisława Przybyszewska’s plays

The most common critique of Przybyszewska I encounter everywhere is that she claimed her plays were a "historical chronicle" (an actual subtitle for The Danton Case), while being very obviously biased, belletrised, prejudiced etc., all in all not exactly the impartial retelling a chronicle is supposed to be. This critique permeats all that is written about her plays to the point when while I cannot exactly complain about the lack of resources focused on her (for such a niche personality she does have a dedicated group of scholars, fanalyzing her works and bringing to life all the forgotten bits from the Poznań archives), it seems to me way too much space is focused on these harsh views, and not enough left for enjoying what I consider to be a genius piece of literature.

When I say Przybyszewska was a genius, I don't only mean it in terms of brilliant literary prowess. She was actually a modern renaissance woman, talented in many fields, and if she constantly complained about not being good enough in any of them, it was only because she held herself to unbelievably high standards. Therefore it is simply stupid to assume she actually considered what she knew to be fictional - to be a chronicle. A title is one thing, believing it's true is another and I think the very least we could do in order to understand her and her works better, is to stop treating her like a child who did not pay attention in history clasess.

A small sidenote: Sandor Marai, my favourite Hungarian writer, has a knack for writing all love stories as if they were criminal cases, and the main character was conducting an investigation of sorts. Which makes it very fitting that in one of his most famous novels he introduces us to the concept of "reality versus truth". This seems counterintuitive, but I don't think it really is, and I also think this is something which should be more often applied to Przybyszewska. Too often she is being judged on the basis of having taken "too great a liberty" of assuming somebody's intentions and explanations. People act as if the very fact she wanted to give studying history a try already makes her a writer with an aspiration to be a historical writer. Now, I haven't read Albert Mathiez yet (but it's in my plans, as I don't think anybody can seriously discuss Przybyszewska without getting acquaintanced with Mathiez as well), but I doubt she wanted to write a history book, only better, only in form of a play, after studying Mathiez, much as she liked him.

All this points me to the direction of something I will call "A Prime Theory", and it's not very revolutionary, but it seems to be absolutely crucial to put it in place, because Przybyszewska is constantly being - unfairly - judged on the accordance and compatibility with the historical events, when it should not be the case. The foundation is this: the revolution Przybyszewska described is not The Great French Revolution, but The Great French Revolution'. According to mathematics for every Point, there is Point', identical to the first one but on a flipped side of the axis, so to say. I believe she has described something more akin to a parallel reality, with the general grasp on the events more or less the same that what we know from our history, but with occasional changes and differences. Therefore she did not describe the "reality" of the Revolution but the "truth" of it.

It is possible because the way Marai understood "truth" was that it was the essence, the gist of something much more than the actual chronology or honesty of a situation. The truth is much more personal and what we believe to be true, than what is factual and provable. The first and easier example would be the way she described Robespierre in regards to his physical traits. In every historical account I've read there is some thought dedicated to his fragile health and meagre posture, and Przybyszewska wholeheartedly disagrees, sprinkling small but firm descriptions that work to the contrary; any sign of illness or weakness is in her eyes onlyt emporal, besides, it's not really a weakness if it shows he has undergone (and proved succesful in the endeavour) such a multitude of obstacles any lesser man would have already given up. So even the "negative" traits she flips around so much they become "positive" in the end. They are literally being foils of their original meaning. The gnostic inspirations I have written about in the past have a lot to do with the general idea I'm describing now. The overall duality seems to be interwoven into the text, which is why I cannot treat it as if it were a singular thing. And I haven't even mentioned all the things she outright invents, like bragging about Robespierre's luscious hair (which are hidden under a wig anyway), or comparing him to a tiger or a cat or a dancer, or describing him with the help of a language which is highly metaphorical and imaginative. She is very visibly inventing Robespierre anew - why would she be accused of distorting a portrait of a historical figure, when it is clearly not THE historical figure she put on the stage?

It would also be unfair to judge her in terms of accuracy with history, because she was, after all, not a historian. I need people to understand (it seems funny to write about it, but it's been adressed so much by so many I think I really have to) she was not a bad historical writer, but a brilliant fictional writer. That her fiction resembles our reality so much is a point which still does not warrant reading her plays as historical plays in any way, shape or form. To be honest, I think any kind of factual reading of Przybyszewska's works is not a good idea, because she was so far removed from social and political life, she had so few friends or even just people she kept in contact with, I find it hard to believe she would even know how to describe actual, interpersonal relations, or political lobbies. This is more visible in her prose, but the relationships she's describing don't feel at all natural, and that is not because she was a bad writer - after all she a was a genius writer, with a talent few can match. She was innovative to the point of being incomprehensible by others, and the falsity and lack of natural feeling in the way she saw people is completely due to her lack of expierence of living in a society. This is what I find lacking in the discourse around Przybyszewska - not enough space is dedicated to underlining the fact her life was extraordinary in every aspect. Her life experience was something most people cannot even imagine, and especially this is not something we expect of a writer of her level.

I think I know where this dychotomy in perceiving her comes from: she used mechanical, detached language to describe the misery she lived in, and it seems to be a mascarade a lot of people still buys. It's the same things with the subtitle in TDC - we believe her at face value, completely disregarding the fact she was a writer, she was inventing fictional things all the time! It's like no one (not many people I've read anyway) is able to discern between what she put on display and what was really going on in her life or in her mind. I'm yet to see a good critical paper on her arguing that her perception of the world in all aspects must have been skewed because she was addicted to hard drugs. It's like no one notices it, nor the fact that she was allegedly sexually abused by her own father? There aren't that many more messed up situations than this one to find yourself in. The way she saw the world and described it in her works was surely affected by that, too. This is another argument in favour of truthfullness of these plays: she described what she felt was true, what she believed was true, what she imagined was true. It’s not a lie, if it doesn’t claim to be all encompassing turth, in short: it’s not a lie, because she said so (it only works in ficiton, but luckily for us, this is fiction!).

When I speak about "multi-realities" in her plays (a term I'm borrowing from Leon Chwistek, a painter and a mathematician living roughly in the same time as Przybyszewska, they had friends in common but I'm yet to discover if they knew each other personally) I mean, actually, that there is a multi-faceted way to look into her works. Yes, historical knowledge is good for analyzing the plays from one angle, but one mustn't stop at that. There are realities aplenty: reality of love, for one, is something she described very well. She also - mostly through Robespierre, partially through Billaud and Saint-Just - reaches out to the hypothetical future and describes possible, future realities. Her characters are not thethered to one spot, what she wrote encompasses more than what we see on the pages.

I think taking a step back when analyzing her works would go a long way. Not many people on here has read Ninety-Three, her short play, but this works as a good counterexample - in The Danton Case and Thermidor we get so hung up on the point that it surely must be reality, because all the characters are given the correct historical names etc. etc. we forget they are made up. In Ninety-Three, however, we don't encounter the same problem - I am positive there was never any princess Maud de la Meuge - and thus we are automatically able to read it as a piece of fiction.

Now that I think of it, this is another reason why it's easier to analyze in regards to fictionality her plays as adaptations, and not as the raw text. It's because the directors do a lot of additional fictionalizing for us, adding even more realitites to the already full melting pot of them. We need this abundance to see for ourselves neither of these plays are historical and it’s easier to come to this conclusion when the characters are very obviously wearing costumes, or the anachronism of the stage situation becomes too apparent.

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#thermidor#ninety-three#dziewięćdziesiąty trzeci#literary analysis#leon chwistek#idk i said a lot of words while the idea is very simple

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Therapist: Chainsaw Robespierre isn’t real, he can’t hurt you.

Chainsaw Robespierre:

#mine#no there aren’t any high res images of chainsaw robespierre#sprawa dantona is something else#camille’s wig unnerves me too but chainsaw robespierre is cursed#somebody please link me to where I can watch the full version of this#preferably with subtitles. I don’t understand polish#sprawa dantona#jan klata#maximilien robespierre

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, so I've found yet another version of the "Danton's Case" play

Because I have a habit of searching random Przybyszewska related stuff on the Internet in the middle of a night. And oh boi.

Look, here's for example Danton fucking lifting a tiny Robespierre into the air + other moments of their confrontation

Dantom and Camille being super dramatic + Danton getting protective of him

A passed out Philipeaux

Louise and Lucile just being amazing and beautiful

+BONUS

Camille had to be literally carried out during the trial

#ok LISTEN THIS WAS SUCH A WILDE RIDE#even wilder aomethimes than the box version I must admit#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#camille desmoulis#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton's case#sprawa dantona#frev#french revolution

131 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis de Saint-Just ( Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, Antoine Louis Léon de Richebourg de Saint-Just, Saint-Just ) - jeden z czołowych przywódców rewolucji francuskiej, bliski współpracownik Maksymiliana Robespierre. Słynął z bezwzględnego terroru, stosowanego zarówno wobec przeciwników rewolucji, jak i innych rewolucjonistów (m.in. sporządził raport, który doprowadził do aresztowania, skazania i stracenia Dantona). Zwany z powodu tej bezwzględności i olśniewającej ponoć urody "Aniołem śmierci" lub "Archaniołem Terroru". Przez niektórych ludzi ze swej epoki był również nazywany "Świętym Janem - Mesjaszem Ludu", "Gwiazdą Rewolucji". Urodzony w zamożnej rodzinie. Po śmierci ojca, Louisa Jeana de Saint-Just de Richebourga (oficera kawalerii francuskiej odznaczonego Orderem św. Ludwika) w 1777 r., był wychowywany przez matkę - Marie-Anne Robinot. W wieku 19 lat, po nieudanym związku z Theresą Gelle, córką miejscowego bogacza, uciekł z domu do Paryża, gdzie został aresztowany. Podczas pobytu w ośrodku poprawczym napisał poemat pt.: L'Organt, w którym dosadnie krytykował zarówno monarchię jak i papiestwo. Poemat ów wydano następnie drukiem. Po wyjściu na wolność z zakładu w 1787 r. odbył studia prawnicze w Reims, a następnie został asystentem u prokuratora. Po wybuchu rewolucji aktywnie działał w swoim regionie, był oficerem Gwardii Narodowej, korespondował z Maksymilianem Robespierre i Kamilem Desmoulins. Jako przedstawiciel swojego regionu brał udział w eskorcie króla Ludwika XVI po jego nieudanej ucieczce.Należał do stronnictwa politycznego jakobinów. Najmłodszy deputowany do Konwentu Narodowego, zdobył sławę swoim przemówieniem w czasie procesu króla. Saint-Just wygłosił wówczas wielką mowę za egzekucją, uzasadniając, iż Ludwik XVI musi zginąć, gdyż jest tyranem z racji samego faktu bycia dynastycznym władcą państwa. Angażował się następnie w rewolucyjne projekty stworzenia nowego człowieka, pisząc m.in. książkę o modelu edukacji w państwie republikańskim i rozprawę L'esprit de la Revolution et de la Constitution de France (pol. Duch rewolucji i konstytucji francuskiej). Jego druga książka, zatytułowana Instytucje Republikańskie, nie została ukończona. Był członkiem Komitetu Ocalenia Publicznego i komisarzem Konwentu na prowincji. Działalność propagandową prowadził głównie w świeżo tworzonej rewolucyjnej armii francuskiej walczącej z Prusami. Wielokrotnie dawał żołnierzom przykład nie tylko osobistej odwagi, lecz także bezwzględności wobec dezerterów i chwiejnych politycznie.Poniekąd słusznie oskarżany o zainspirowanie wielkiego terroru (czerwiec – lipiec 1794 roku), został aresztowany 27 lipca ("przewrót 9 thermidora") i zgilotynowany wraz z Robespierre'em następnego dnia, w 114 dni po śmierci Dantona. Saint-Just jest jednym z bohaterów dramatów Stanisławy Przybyszewskiej: Sprawa Dantona oraz Thermidor. Pojawia się w mandze Riyoko Ikedy Lady Oscar, a także w nakręconym na jego podstawie anime. Louis znalazł się w komiksie Neila Gaimana Refleksje i Przypowieści z cyklu Sandman. W filmie Danton Andrzeja Wajdy w rolę Saint-Justa wcielił się Bogusław Linda.

0 notes

Text

Haiku dla Stanisławy Przybyszewskiej

Haiku dla Stanisławy Przybyszewskiej

Tomik poezji Haiku dla Stanisławy Przybyszewskiej / Haiku for Stanisława Przybyszewska powstał z mojej pasji do literatury Stanisławy Przybyszewskiej. Książka zawiera wprowadzenie, w którym odkrywam czytelnikom Stanisławę Przybyszewską, autorkę wybitnego dramatu pt. Sprawa Dantona, jako poetkę wierszy haiku, również piszę o jej wielkich literackich osiągnięciach. Forma haiku jest zwięzła,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Transnationalism

One thing which I haven't seen being brought up before, is the issue of transnationalism in Przybyszewska's work. At first - while I usually try to have a less biography-oriented approach - I have to say this cannpot be discussed without knowing Przybyszewska's very peculiar personal standing in regards to belonging to a nation and a state (but I will try to keep it to a minimum).

She was born as an out-of-wedlock child in times when it was not regarded lightly. Though both her parents were artists, and her father extremely extravagant and with a reputation of a Don Juan (bad reputation, and entirely deserved) at that, it didn’t change much. Her mother, no matter how artsy and talented she was, was herself a protegee of an influential family, not to mention - a youg woman. Which means her pregnancy was not taken lightly, her protectors were disappointed in her, she had to move to Paris not only because it was one of very few places were women could potentially make it big as professional painters, but because she would not be received in her usual society at home. All of this jumpstarts Przybyszewska's life as a person uprooted and banished from her home - but it's not all, nor is the fact that despite knowing who her father was, she was not officially recognized as his daughter until her teen years.

When she was born, Poland was still partitioned, which made Przybyszewska a stateless person, a subject to Austria, but of course not regarded as a fully fledged citizen (and that's without even taking into account the first 12 years of her life, when she lived as an expat, mostly in France, with her mother). In fact, she lived in these conditions for the first 17 years of her life, which makes it exactly a half of it (she died at 34). And if this was not enough, when she lived in Poland, she spent the majority of her time in Gdańsk, which was a Free City, with two nationalities - Polish and German - flowing more or less freely (Polish on evidently becoming subdued as the war approached). Seeing as Przybyszewska wrote a good prtion of her works in German, and thought of it as a language far superior to Polish, and knowing her personal opinions on the state of Polish cultural life versus the cultural life in Europe, I'd wager to say she was never, ever someone who felt somewhere "at home".

Nationalities aside, she was also decidedly a gender non conforming person, which is its own issue (I attach a photo of her, and it should speak for itself). I'm not making any claim about her, it's just that everything in her life points to a. uprootedness, and thus b. being a foreigner in her own country/language/life/skin. (I think a bit more could also be said about Robespierre’s sexual orientation in the plays, and how it’s adding another layer of alienation, but I think I prefer to store it away for a post focused only on the love story. The most important part here is that he doesn;t even need this, something which may well have alientaed him in the real life, to be portrayed as a foreigner in his own country.)

This is interesting to me not only because it weaves itself seamlessly into what I was talking about previously, the multirealities. I think looking at her through lenses coloured with understanding just how much of a stranger she was everywhere and with everyone, we may begin to understand the way she portrayed Robespierre, most importantly in Thermidor.

Maxime is presented as someone who does not have much in common with his fellow people, and despite working, ultimately, to preserve/save the Republic, his methods seem so unorthodox he is more than once suspected of a treason, most notably in Thermidor as a whole, but also in The Danton Case, when he vehemently disagrees with arresting Danton. This last scene is important on more than one level, actually, because the suspiscion spreads to more than just having potentially erronous opinions, he is also alluded to be gay, which is a small thing (in the universum of these plays this is like the smallest thing of all one could be "charged" with), but still, it is something which deviates from the norm, putting Maxime - and anybody who follow him by proxy - outside the circle of what is considered normal and approvable.

And in Thermidor we see it on two different fronts, which are both very unlike each other, but they tend to the same goal. On the mental level, Maxime is a foreigner, because he is not even human (he's a "sterile god", as Billaud puts it), which I discussed more broadly HERE; and he was on few ocasions compared to plants, animals and objects, making him less humane as a result. He is also very far removed from his usual social circle, both in terms of mentality - his vision spans such a distance no one else can comprehend him - and physical space - he doesn't leave his rooms, when Barere relays the news, the whole Comsal is surprised to hear he has gone out to the streets. Everybody seems to perceive him as a stranger, a foreigner, an extraterrestrial being, an unwanted element not simply because his opinions are faulty (Billaud has similar ones, yes, but what is more important - Saint-Just has the very same ones, and yet the Comsal did not want to destroy him, they only wanted to destroy his friendship with Robespierre; this is very interesting to me and I will focus on this more next time). On the much more factual, physical level, though, Robespierre is a foreign element in his own Republic, because what he has undertaken is, in fact, treason:

Showing through Robespierre that the only way to move out of a stalemate is through cheating his compatriots, and without any remorse about doing so, Przybyszewska dots the is in regards to how she saw the world. Robespierre is such a singular being, that what is a treason objectively - in him is only a hidden mean to a good end. She (probably consciously; she was well aware of the grey zone she lived in and did not mind it all that much) put him outside of any ircle he might belong to, therefore all his choices are in the same time foreign and not maliscious. It's reassuring she at least showcased what happens whena being who is not foreign (Saint-Just) tries as he might to break the fence and either let the alien element in, or join it on a higher level of understanding. Of course, by showcasing it, she only underlined the point I made. This is expecially not-cliche, in my opinion, in plays focused on one of the greatest spurts of patriotism she could think of. Admiring revolutions on one hand, and admitting in the same breath they cannot be saved from within, only from without, only through means that are doubtful at best, is an interesting choice of action, not expected from someone who made it her whole life to proclaim revolution to others.

Making Robespierre become a traitor in the last, decisive stage of his life isn’t, in my opinion, an autobiographical commentary by Przybyszewska, I think it’s much more of a blind spot for her – I don’t think she thought what he has done was traitorous at all, just seen as such due to legal technicalities. It is also a bit like a disease, in that he literally contaminates Saint-Just with his thought:

Not all of them follow Maxime so easily, though, do they? (Also, a side note: in the original, Saint-Just does not speak „matter-of-factly”, he speaks „nearly with admiration”. It changes a lot, if not everything, in what he has just said.) Not all of them are as easily picked up by the wind of new ideas, because they are all too firmly rooten in th ground; Saint-Just I find to be someone on the edge between the two states, he’s way more grounded and at home in the world than Maxime, but not nearly as much as, say, Barere. Ha later admits to following Maxime „mostly” (so not in fullness), he also insists: „you are already burning in the blast furnace of your spirit. You alone.” (so he’s not sold on the idea completely, it’s more that he loves Robespierre and is ready to accept almost everything of his’ at face value). Besides – while I don’t necessarily think it should have been understood literally – there is this one small scene, laden with symbolism:

It is, of course, about death. It is also, equally, about pulling Maxime back to Earth by someone whose head is lost in the clouds a bit less often. Death fits the story all too well, because in this instant Robespierre is tempted to die, because what he has undertaken is too much, yes, but also because he miscalculated, his ideas were too lofty and otherworldy to become applicable (and! don’t even get me started! how his plan was not destroyed by someone hostile to him, but by Saint-Just, whose only crime is being too practical).

Przybyszewska’s writings are full of such creaturs, great minds who cannot 100% find their place in this world, and, more often than not, the end they meet is death. Her other French Revolution heroine, Maud de la Meuge, is the one who scarcely avoids it, by means of a concoluted (and, frankly, a little banal) plot, but the words from this play fit here very well:

Of course, no one would dare to talk to Robespierre down so, but the thought remains. And if Przybyszewska were ever able to finish Thermidor, he would have died, too, not because his story follows the original as closely as could be done in the circumstances, but because he’s doomed from the beggining by his overgrown genius.

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#Maximilien Robespierre#robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#literary analysis#frev#French Revolution#the danton case#sprawa dantona#thermidor#saint-just#antoine saint-just#ninety-three#dziewięćdziesiąty trzeci#rewolucja francuska#pollit

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! In lieu of this blog becoming a bit more academic from now on, I feel the need to organize my posts in some way, so from this point onward please refer to this list, sepearting my posts thematically. I hope it will help you find what you need with greater ease.

Scene breakdowns:

Robespierre’s hypothetical suicide

Robespiere&Camille versus Robespierre&Antoine

“Camille, don’t be a bore”

Antoine has always loved Robespierre: evidence

Danton versus Robespierre

Fabre’s phrase about a jewel

“Everything allright?”

“I would like to dance”

Themes and motifs:

Creating characters on an axis

Ekphrasis

Gnostic inspirations

Przybyszewska and women

Religious references

Costumes in Thermidor tell a story of illness

Who is the main character od The Danton Case?

Multirealities in Stanisława Przybyszewska’s plays

Transnationalism

Theory of literature and critique:

Stanisława Przybyszewska literature masterpost (periodically updated)

A review of Kazimiera Ingdahl’s book

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#literary analysis#analiza literacka#academia#sprawa dantona#the danton case#thermidor#termidor

19 notes

·

View notes

Quote

SAINT-JUST (odchodzi od stołu, błąka się) A tyś mi złamał kręgosłup.

Stanisława Przybyszewska, Sprawa Dantona

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So the day has come and I will finally put my hands on one of the most beloved scenes from Thermidor.

I would like to dance scene first captures our attention by being a first clear instance of a respite after an over hour long, increasingly more intense monologuing by the Comsal. I would argue, that this is not the first one, but that one is hard to miss, as it’s soemthing which happens between the lines and more in the stage directions/actors’ expressions and is easy to miss or to not include in a staging altogether. This one is, however, refreshing and calming without any other drama going on between the phrases.

The first thing, which in my opinion makes it standout from other „nice” scenes from either The Danton Case or Thermidor is that it truly loses it grandiloquent tone. When in TDC Robespierre talks with Saint-Just or when he tries to reach out to Camille there is alway a lot at stake, and their is always some or other ulterior (not necessarily: bad) motive going on symultaneously. Here the issue had been resolved completely right before this scene – which makes it right, I think to call it a separate scene in its own right. Yes, Przybyszewska did nothing more than to divide the play in two Acts, but I think it’s mostly due to the play being unfinished; if she had sufficinet time to get back to it, I’m sure she’d put some other system in place (the room doesn’t change so perhpas she left it as a continous streams of „scenes” rather than divide it, as to not break the unity of place? Mayhaps, but I still think the division is visible and barely seamless).

First of all, I’d like to point out, that while all in all I do like Bolewsław Taborski’s translation of this scene (I have it memorized and it really flows from the tongue very well when spoken), there are few points in which I would have made small changes (marked red). This is becase sometimes the meaning of the whole phrase lies in either this or that word, and the difference is small in size, but absolutely crucial.

· You did lose your composure at last. vs In the end you did lose your composure.

Here it is more important that Robespierre’s tensions boiled in him, and that Saint-Just egged him on to the point of an outburst than the outburst had happened at the end of something. It shows us that these emotional turmoils do exists in Robespierre and torment him as much as they do any other man, but that he doesn’t let it show on his face, unless he’s being pressured by someone who knows what to say exactly and which buttons to press to achieve the goal. It also workes much better in conveying a supposedly smug expression on Saint-Just’s face, a tone which we can assume is triumphant, while Taborski’s phrase make it look more like a calm recounting. Here it begins to unfold in front of us that Saint-Just isn’t immovable, that he is in fact quite an easy going person when faced by no one else but the person who knows him most closely and intimately.

· A truly consolidating feeling. vs A truly refreshing feeling.

I admit that this one is mostly a personal choice, becasue in a dicctionary, pokrzepić is, in fact to refresh. But as a native speaker I just know that pokrzepić is less ethreal, it’s in a fact a very grounding, calm and solid word. It works as a contrast between the increasingly playful vocabulary Saint-Just presents and the still calm and more cautios about displaying emotions Robespierre. This is a tiny detail working as a characterisation.

· Hands folded one onto another vs crossed hands

This one, in turn, seems to me to be pivotal. Hands which are crossed send a message of denial, anger, refusal and so on. Hands folded onto one another are more about being calm and at ease, and about acceptance. This can still be resolved through proper stage movements, but I’ve yet to see it done properly (HERE I talk about why the hand folding and head leaning back is extremely important).

· I would have to feel ashamed. vs I would be ashamed.

The difference is small, but striking. You feel ashamed out of your own volition (even if it’s influenced by the environment), but if you have to feel ashamed, does it not mean that you don’t necessarily see the need for shame, but that your environment does and is forcing you into this emotion? That’s the way I see it and in my opinion it subtly kets us know that while Robespierre, for one, sees nothing wrong with the situation currently unflding between the two, he knows it would not be met with proper understanding from other people. I may be reading too much into it, but I would have to see the German original.

· I am too occupied with trying to win you back again. vs I am too occupied with trying to find you again.

So this allows us a glimpse into the untold life behind the curtain that Robespierre and Saint-Just have – and share. Zdobyć literally means to win, i’s something you could say about a prize. Finding (even finding agains) doesn’t have the same air of grandeur about it, finding may be accidental, winning, however – is something achieved through a sense of purpose. We now see in its entirety that Saint-Just isn’t taking any of this lightly, no matter his smile or his playful expressions. He has won Robespierre in the past, and then he’s lost him, and now he is adamant to win him back again. This is no small thing – this is his life purpose, his prize.

· Wait! Don’t disturb me, Maxime... vs But...! You mustn’t interrupt me, Maxime...

Here the difference is again pretty optional, but I like the personal feeling my version evokes, the familiarity/intimacy. By removing mustn’t we remove the tone of an order, something which is cold and distant. Yes, Saint-Just is disappointed in Robespierre’s reaction (even though, if you had read the post I had referenced, it is completely understandable), but that doesn’t mean it offends him in any way, therefore there is no need to assume a cold pose.

Now, with verbal details out of the way, I would like to focus on the tone of the scene as a whole.

When I talk about intimacy, I’m being very serious and straightforward. While I am the last person to make everything about sex and even rarely see things in a sexual context, here I had never any doubts that Maxime and Antoine spoke in code – if we can even say it was a code, for it was all so plain.

First of all, I’m not even talking about the „you would like to sleep” bit, because while it didn’t call for a separate bullet point on my list, the expression that was used in Polish was rather „to fall asleep”, without any sexual innuendos. This is the familiarity at work, not intimacy, it is a reference to Robespierre enormous tiredness, one of which Saint-Just was all too often a witness to. Antoine’s heart and mind ar at ease at the moment,s so he would like to extend this calmness to Maxime and offer him – even though he knows it will more than likely be refuted – some of this relaxation, too. What he doesn’t expect, I think, is that Maxime takes him up on that offer but with a twist, and turns a conversation which could have remained friendly into something from an another, flirty level.

I’m assuming that everyone and their mother already knows this, but la petite mort is an expression used in French to describe an orgasm/a feeling after an orgasm. I’m not saying that by saying that he would like to die now Maxime is making a direct request/offer, but he sure is making a clear enough reference – which is why I always imagined Saint-Just’s reply to be said with laughter rather than completely seriously. Not to mention, the rest of this exchange makes another dig at it: I will argue that „a sublime thing looking for means of escape” is another sex reference, or at the very least could be read that way. This is of course too much for Maxime, whose prudish nature in this regard was already explored at depth in The Last Nights of Ventose.

The last thing I would like to talk about is a small, internal reference which I think this scene is making:

When at the end Maxime complains about trying to get through the conversation with „a broken neck” I think it serves (even if inadverently) two purposes. One is, of course, to cut the conversation short and get to the bottom of the political intrigue, which is what is more pressing and interesting to him than any flirting could ever be. The second, however, brings to my memory the scene at the end of The Danton Case, where Saint-Just tells Robespierre that he has broken his spine.

ROBESPIERRE [His legs give way under him. He sits at the edge of his bed.] Oh, you have finished me, you know.

SAINT-JUST [leaves the table, walks aimlessly] And you have broken my back.

In the original he actually says: And you havebroken my spine. A spine is, of course, an extension of the neck in terms of anatomical built, and so I believe these two instances should be compared side by side. It is very telling (though I may not yet know what it is exactly they are saying) that Robespierre metaphorically breaks Saint-Just’s spine when they are fighting, but Antoine, in turn, (a bit less) metaphorically breaks his neck when they are makin up. Is this a foreshadowing, that no matter what they are doing and no matter the turn their conversation is taking, they are doomed?

#Christ has risen - indeed He has risen.#Happy Easter everybody!#frev#french revolution#the danton case#sprawa dantona#l'affaire danton#thermidor#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#antoine saint just#maximilien robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#rewolucja francuska

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is absolutely doubtless to me that Przybyszewska had a problem or two when creating and describing/explaining her heroines, problems, which do not seem to occur when men are concerned. I do think, however, that in The Danton Case (not to mention her prose) she managed to build female characters with distinct personalities, which is more than can be said of some other classics.

Going back to the way sexuality is being portrayed in The Danton Case, I honestly think that in order to be able to discuss it with good sense one needs to understand and respect asexuality. I am being somewhat in opposition to what Monika Świerkosz proposes in her article on the subject, I do not think that Przybyszewska's women "deny themselves any pleasure" when they choose ascetisim or politics, because one cannot deny themselves anything if one doesn't believe in the existence of such "pleasures". I feel that in this very personal aspect of a human life, Przybyszewska was drawing from her own experience more than on any other occasion: the pleasures of life was, to her understanding, ascetisim/celibacy and politics, and choosing them in no way indicates negating oneself. "It would appear then Przybyszewska realises that "a full lack of the element of desire" in regards to the world is a more radical violation of the norm than homosexuality or perverse sex; it is something for which there are no words". With this though, I agree in fullness. And so, all of Przybyszewska's heroines seem to share one quality, that is – they resemble ancient virginal goddesses of some sort, not exactly because there is an aura of divinity about them, but because they do not seem to be fully, wholly human. This "virginal" quality has little to do with their sex lives, and more with the desire for autonomy on all levels of being (physical and spiritual, not to mention – mental). I reserve for myself the singular right to my life was Przybyszewska's credo and arguably the strongest, firmest phrase she has ever coined. And this is the energy she breathed into all three women in The Danton Case (excluding, I must add, the few appearing in the very first scene; but most of the time no one reads it anyway); the level of intensity and the direction of this desire varies, but it is always present. I would like to present this in three parts, each relevant to one of the characters of the play.

Eleonore is evidently Przybyszewska's favourite, if only because she's devouted to Robespierre – but I think she is also modeled a lot after Przybyszewska herself, not just in terms of this undying devotion, but hers is the type that is later reproduced in many short stories (which, unlike the plays, are filled with women of different kinds to the brim), which makes it obvious she was armed with qualities the author found appealing. That's why it's so strange that Przybyszewska has essentially created two very different Eleonores: one in the play, and one in The Last Nights of Ventose. The first one is definitely meant to be depictured as elder, she has an ironic sense of humour and is very decisive and firm, despite making allowances for Maxime and his rigid rules. The second one is definitely younger, has a hard time grasping at irony, is timid at times and yields to Maxime rather than moves not to be crushed by his wishes. For a reader – probably any reader – the first one is definitely more appealing, more fun to read – more complex even, and given a will of her own, which makes her stand out among the majority of the play's characters (for example: the other members of Comsal have less distinctive personalities than her).

There is a weakness in her, though, or at least the way I see it: she does not feel natural. I'd give anything to have a strong, believable female character in that play, but Eleonore is... not it. Her sense of humor, her quips, her behaviour when she's constantly being met with disappointement don't read real in my eyes, it reads as something "too cool to be true" – therefore, it probably isn't. She has some occasional moments ("You viper!" comes to mind) when naturality shines through her words, but it isn't 100% of the time.

How does Eleonore express her femininity, does she do it at all? Well, yes and no. She seemingly willingly puts herself in a position, which is stereotypically feminine, that is to say: but an accomplice to the man of her life, putting herself second and him first, occupying herself with stereotypically feminine tasks of housekeeping and taking care of others (it is worth noting that these are all traits that have potentially negative quality about them, they can easily be distorted into degradation). In the same time, she assumes the air of equality when talking with Robespierre, is deeply interested in politics and holds her own when Maxime tries to dismantle her attempts at reaching out to him. She is also decidedly "virginal", if we are to reach out to the terminology from before, taking a firm stand against motherhood, even expressing a certain amount of contempt for the idea; this is, however, where the virginity of hers ends, because she is otherwise a very sexual person. To be honest, the way in which she is being presented to the audience – literally sliding down Robespierre's torso and kneeling to him, gripping tightly at his knees and very visibly trying to give him a blowjob first thing she sees him well after weeks of illness – is rather disgusting, not necessarily because sex is (a disclaimer, which could probably be put at the beggining of this post, since it's a bit relevant: OP is asexual and has nothing positive to say about sex), but because this is how she imprints in the audience's minds. No feigned irony of hers, no clever remark will be taken as just that, all will be tainted with the image of this otherwise sensible woman degrading herself for a scrap of attention from someone who says bluntly that she is indifferent to him (and as I always underline, in the universum of this play, Robespierre only ever speaks the truth, at least in the spiritual/mental matters, so we know he means it).

For the reasons listed above, I see her as both womanly and manly, if we could call it that. Monika Świerkosz, a Przybyszewska scholar, said that "[...] in Przbyszewska's prose works womanhood and manhood stand in a binary oppsosition to one another, and neither is an enclave of happiness of identity." – I don't think it's strictly accurate. To my understanding, the phenomenon relies on Przybyszewska not relying on any kind of deeply rooted gender stereotypes in creating her characters. It's not like she's taking a steretypically understood masculinity and simply sprinkles it over her heroines! She is operating in the fields of transsexuality, demisexuality and nonbinarity (not exactly in the convential meanings of these words, but there is something to it). I find it hard to put in words, perhaps the thing I want to say is mostly that her characters as a whole don't fit a clearly defined niche and live their own lives at the outskirts of customarily understood gender instead of being solely mouthpieces for the author.

Going back to the concept of virginity, which is especially relevant in Eleonore's case (and especially the one from TLNoV), when it comes to the woman who is always in Robespierre's orbit, it is being contrasted with his own attitude and thoughts on the topic. She's the one begging him to reconsider his stance on the subject, she's the one trying to sneak up on him and shutter his defenses (which is, again, explored and explained in a more detailed way in the novel). It is worth mentioning, though, that while she is constructed as a somewhat sensual person, she is still babyfied about it, there are narrator's remarks about her naivete and innocence in this regard, despite some – very limited – sexual experience. For this reason I'm on the fence in deciding how exactly is this trait used in Eleonore's case. Is she meant to be seen as more mature because she's had experience, knows what she wants, and she's willing to do a lot to obtain it? Or is she meant to be seen as more silly and childlike, not understanding her own desires to the fullest? Are we to admire her or pity her?

Willingly or not, Eleonore becomes an embodiment of a very important characteristic which Przybyszewska uses extensively in her short prose works. If she, for whatever reason, cannot achieve the fullfilment of what she's striving towards, she then personifies ascetisim. And ascetisim is the clou of all of Przybyszewska's life. At the heart of matters, she doesn't care for either virginity or motherhood (in this making equal two things treated usually as polar opposites) as long as ascetisim remains in the world. It is for Przybyszewska a synonym of both "autonomy" and "agency", two ideals powering her life (though, might I add, there is a bit of falsity in this, for her own autonomy relied on being dependent on the financial help received from others and she gave up an almost full autonomy – which could be found in providing for herself – in exchange for the absolutely full autonomy in just one aspect of her life: writing).

I have mentioned before that Eleonore doesn't seem to be entirely natural in her behaviour. Przybyszewska was to a very large extent fascinated by futurism (for her the Revolution, as well as any potential revolution, was worth taking notice of because it brough in the new), and a big part of european futurism was its own fascination by machines. While I, personally, disagree with the notion that machines and robots become a synecdoche of a man, perhaps it really were so for the futurists. A machine ceased to be something completely external and foreign to the humans, it begun to be more of an external part of a perosn's body, a complement of sorts. I think this is why "female" robots, or in general any mesh-up of robots and women may seem more natural to us: they usually already have this one additional organ, and through it, they can produce more humans. And this is what ties back to the idea of Przybyszewska's female characters being sort of divinities, but in a cold, rigid (ascetic!) sense of the world.

For none of them is exactly warm. Moving from Eleonore onto Louise,we can see she's even colder, and not without a reason, there is a cause for why she is the way she is – standing as a contrast to the fleshy, "humane" Danton she couldn't be anything else. What I like particularly well about this portrayal is that it's never shown in a negative way (and not even because Danton is... I think Przybyszewska's own sad experience with sexual abuse played a part in that). For the reasons of the sexual abuse she underwent, Louise is also portrayed in a decidedly virignal light: the things that have happened to her do not define her. She is so in a very different way than Eleonore, she weaponizes this part of her life which is seen as stereotypically connected to womanhood, while being detached from sensuality: motherhood. Her pregnancy is the first respite from Danton she has and she clings onto it, not even in a desperate way, it's cold, calm and calculated. Her young age also serves the same purpose, it detaches her from the customarily understood femininity, it makes her less "womanly" and more "girlish". I don' think I speak only for myself when I say the audience would have a hard time imagining Louise actually becoming a mother; for her this is only a weapon, a means to an end and that is because she is not yet fully formed woman, in a sense.

There is a thing about her and her appearance in the novel and how it presents to us that begs a moment of distraction. In his movie, Wajda took care of presenting both Eleonore and Lucille in a visually masculine way, but he did nothing of the sort with Louise (he barely included her at all, but even so, she was over the top feminine in visual aspects). I don't think this was a good move on his part, in all honesty, it creates a division between her and the other two heroines, while there should be no such thing. I think all three serve a much more unanimous role than what he'd have us believe and this text is partially meant as an explanation why.

So Louise, for obvious reasons, is rather disgusted by all matters pertaining to sex (and that is seen not only in her interactions with Danton, but also with Legendre, that's why we can safely assume so at large). She is shown as strong, strong-willed and intelligent, which is another thing pointing us in the direction of her mentality of an "ancient virign" (I use some terms liberally, but I hope I convey the meaning behind them well enough). She was stripped of all of this in the movie, and this time it was sadly yet another rung on the ladder meant to elevate Danton. In order to powder his face to make him presentable, Wajda had to exclude Louise from the movie and make her a prop rather than a person. I dare say he, as a man, saw Louise as a "anti-woman" because of her attitude and his artistic choice was the nearest antidote; but he was wrong. Przybyszewska's heroines aren't fully human, yes, and aren't fully womanly – but they aren't "antiwomen", they are "superwomen" (in the same sense of the word as "superlunary", for example). They are beyond femininity in many aspects and the only reason why we are even discussin them in any terms pertaining to gender and womanhood is becuase a. I have no other language to do it and b. these things exist in the same reality, I need to underline the fact these heroines are "superwomen" only because they, too, have an idea of what "a woman" should be and exist as a some kind of response to it. Louise, for example, has no need for it, because the root of her problems lies in the lense of femininity through which Danton sees her and if it weren't for his demise, he would continue to threaten her in a sexually abusive way, tied closely to her "role as a woman" (one of the last things he says to her is an accusation of sexual nature regarding her).

Lucille's response seems to be a lot less firm (if not: less aggressive) because her environement didn't condition her to be so fully womanly in the first place. A sfar as husbands go, Camille was a much better one than Danton: just as childish, but treating Lucille not only as a beloved, but also as an equal. This allows her for space to grow as her own peson, and if this person includes affirming her femininity (for example through being a partner to her husband, in being a tender mother, in caring for Camille when he needed her most, in loving him to the point of madness) we can rest assured it is her own choice and part of her agenda. She is not weaker than Eleonore nor Louise, she just has more space to breathe. And like Eleonore, she is deeply interested in politics, and not only that, but has a better graps of it than Camille does, connecting the dots quicker than he would. I can't say if this is a part of characterisation of the women in the play, to show them as autonomous beings capable of political thought, or if it was simply a way of gentle reminder every now and then to the audience that politics permeated the universum of the play so thoroughly everybody in it knows their way about it (it is worth noting that Louise also understands the then political troubles, but unlike the other two, she consciously cuts ties with it, for this is yet another thing which belogns to the realm of Danton, and she doesn't want to be further tainted by him).

I like the fact that Przybyszewska included a scene between Lucille and Louise, especially because it was not strictly necessary for her to do so. It is another facet of her craftiness and intention regarding the way women are being portrayed in the play, because while it exists on the structre lied down by the political plot, the most important things that an audience can draw from the scene are: while Lucille loves Camille greatly and will do anything to save him, it is not necessary for the plots/the overall theme of the play for her to act so (as proven by the indifferent Louise, who is in no way villified in her choice) and Louise is not evil as a character, because she doesn't shrink her responsibilities as a decent human being: she doesn't want to help Danton, specifically, but she provides Lucille wih a logical and pretty good way to attempt what she wants to do. Perhaps this is too little to call it a sisterhood between them, but I find this portrayal contrasting attitudes reassuring.

#hello hello i haven't been here in a LONG while but it's my birthday and I'm giving the rest of you a gift#stanislawa przybyszewska#stanisława przybyszewska#eleonore duplay#lucille desmoullins#louise danton#the danton case#sprawa dantona#literary analysis#frev#french revolution#analiza literacka#women#female sexuality#asexuality#womanhood

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Generally speaking, there is no (good?) classic piece of literature, where one cannot spot, or at the very least attempt to prove that it is possible to spot, a biblical reference. And it is no different with Przybyszewska.

First of all, I want to underline that with her it is not a mere coincidence, but a very much conscious decision. She was not religious, but obviously grew up in a culture permeated with christianity, and for a period of time even lived through the help of Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education; it doesn't mean that she was chosen for her great impact on religious affairs, but that for the people of the Second Republic the knot between enlightment and religion was closely tied. And Przybyszewska, while a visionary in her own field, was very much a person of her times.

I also want to preface the post with saying I will be using the King James translation of the English Bible and Biblia Tysiąclecia of the Polish one when necessary. It is also in no way my intention to draw any religious conclusions or to dwelve in any way onto religion – which by the way I hold sacred, so please treat this with respect.

The most prominent – if not the only one fo – groups of biblical references in the two plays is having Robespierre depicted in such a way it is impossible not to think of a Christ immediately. His deification is something even more than a part of the text, it's Przybyszewska's innermost feelings and thoughts influencing her works in the most visible way. That's way there's so much of it, and why it's so consisntent.

First of all, there is the thing – discussed at length mostly in Thermidor - that Robespierre is percieved by everybody coming into contact with him to be omnipresent and omnipotent. He is not a mere human, but some timeless being, all-knowing and all-powerful. This is tackled on two fronts: positive and negative, positive being done mostly by Saint-Just, who has the unwavering faiht in Maxime, and whom Maxime even calls an Apostle on one occasion (that is: the forefront followerr); Camille dabbles in having "faith" in Robespierre as well, though I'd say this is mostly depicted in The Last Nights of Ventose(more about that later, because oh boy), while Eleonore, strangely, perceives him mostly through the humane lenses? His political opponents, on the other hand, jump of fright every time someone mentions his name, or even every time a door opens when they are conspiring against him, and what they think about him is equally interesting, for they all agree, more or less emphatically, that he truly is irroproachable. They perceive him in a way one would percieve a suparnatural creature. Vilate sums it up quite nicely, albeit his personal opinion was slightly augmented in comparison with the rest of his colleagues (because of his past as a priest, perhaps? He even says at one point that he deified Robespierre and prayed to him):

And the talk about him at the beggining of Thermidor is not deprived of some vocabulary, slipped here and there, that is connected directly with christian rituals: rising altars and comparing an altar to a throne. Billaud (who understands Robespierre far batter than any other character of the play, with an excpetion perhaps being made to Saint-Just) makes a curios analogy – he says that Robespierre is a creator, but a sterile one, whose creations lack life. While the trademark of God is that He breathed life into humans, thus gifting them with living and all its implications.

Robespierre is thus called a faulty God, something more than a human, but not quite God; and even as a seraph he is not without imperfections. The explanation as to why is that is twofold: either because he is too human (as Fouché tries to paint him out to be, talking excessively about his weak health, his supposed tuberculosis and prideful timidity) or because what he reigns over is not quite Heaven and Earth – but Hell (as Billaud puts it without beating around the bush).

There is also quite a more frank and obvious allusion to Robespierre's adoptive divinity. Billaud in his famous rant says that Robespierre has ventured into the land of self-deification, and that he considers himself to be a holy monstrance – for those of you not familiar, a monstrace is a richly decorated, usually gold liturgic vessel, used to exhibit the holy Host. There could be no clearer way of saying that Robespierre considers himself to be a God and is acting accordingly. That Saint-Just is in one breath called a "hot-headed youth", who desires to conquer the world for the one whom he loves (the Polish translation is in this regard so much more beautiful than the English one, which is quite frankly a lackluster) is just a further proof, as God's existence secured the existence of martyrs and saints, spiritually conquering the world for His love. Another thing is how Robespierre affects those around him, then, and here Billaud uses a great word in Polish, which English "thunderstruck" does no justice: Lecz jesteśmy porażeni. But we are paralyzed, only "paralyzed" expressed in a highly biblical language, a word which means something more spiritual in origina than mere physical paralysis. For example Jacob became "porażony" when he was struck by God, but I could find various other expamles as well.

In The Danton Case there is – obviously – fewer references like that, but Lucile makes one very good when she talks with Maxime face to face.

What she says I see as a clear refernece to Jesus Christ. Miraculously sent by God to help, has undergone a change which strips him of one part of his identity(the all-powerful Robespierre – Christ – has replaced humane Maximilien – Jesus), leaving only the second one, as a lot of people thinks that when Jesus resurrected, He came back only as a God, forgetting He came back as a man too; it's a common mistake – not to mention Robespierre corrects her, therefore: he did retain both his identities, though one seems to be overshadowed by the other. Why, oh why the French translation decided to go into an entirely different direction here? (We of course know why, to ground it further into historical reality, by making the readers aware of the fact that Robespierre was physically short; Roland Barthes would have something to say on the topic and maybe i will, too, one day.) It completely erases the religious connection she drew, in my opinion. It's still there, to an extent, thanks to the "God Himself must have sent you...", but this is just an everyday biblical reference, so to speak.

There are numerous, numerous things tying Robespierre to Jesus, one of which is his betrayal by friends. Have you noticed he never, never referes to his colleagues by anything more impersonal than "a collaegue"? And most of the time he calls them "friends", which holds a certain dose of affection even if it's used in a sarcastic way. He never calls them his enemies. So his "friends" betray him, much like Judas was one of Jesus's chosen few, someone from his close circle.

Another thing is perhaps more subtle on the textual level, but very telling in subtext. In his anti-capitalist rant in Thermidor, Robespierre slips in more or less visibly a ton of terms and references to the Bible, which the English transaltion ommitted (that is to say, translated in sucha way they lost their religious heritage): that capital is the new god, and the Republic is its Betlehem, and there will be people from all walks of life (shpeherds and kings) devouting their lives to it. That it's not simply a false god, "bożek", but a "bożyszcze" – a deity, but in a negative and artificial way. That it is a Moloch, a foreign deity mentioned in the Book of Leviticus, which was famously offered child sacrifices. And that it will have its own martyrs. The whole of his speech, too, has an apocalyptic ring to it, a calling for repentance of turning from the evil way they're standing on of sorts. Robespierre is a prophet, if he's not a god. (It is worth mentioning that in one of her prose works Przybyszewska's first person narrator straiht up calls Robespierre "the saint Paul of the Revolution" – a saint and a zealot who didn't experience Christ personally, but was not less devouted because of it).

Not everybody has read The Last Nights of Ventose, but there is a small scene in there, where Robespierre, trying to win Camille over, tells him he may kiss him, if he likes, if all that he needs to come over his senses is to kiss Maxime senseless, he may as well do it and be done with it.

(The sculpture is Corpus by Bernini.)

So I have the feeling I might be exaggerating this, but this one phrase always brought forth in my mind the Passion imagery, Christ on a Cross (or at the very, very least, it should remind us of the spiritual ecstasy imagery – look up The Ecstasy of Saint Therese by the same artist), and it's not only about the image, it's about the mentality behind it as well. Robespierre doesn't do it, because he is secretly in love with Camille or anything like it, he is firmly opposed to the concept of physical love – but he's fine with sacrificing his celibacy if that's what it takes to save Camille. For me it's a mirroring of the greatest sacrifice for humankind.

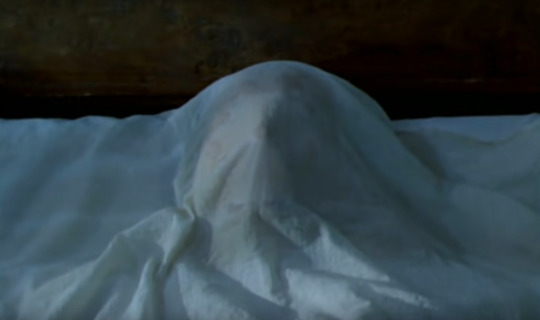

When he's not being deified, Robespierre is being fashioned into a martyr, and there are several clues for that. At the end of The Danton Case, for example, in Act IV, Scene 4 it is revealed he was abstaining from food and drink; albeit unconsciously, it nonetheless leaves a trace of a holy fast in the readers. He is going through his greatest trial, and his body prepares accordingly. What he tells Eleonore lets us know that he also feels responsible – for everything and everybody. That is more still than being a martyr conceals, for me that is in the territory of being a god. And I'd like to reach over to Wajda's Danton and use the imagery he used, in a similar moment, when Maxime is at his lowest. He is depicted as something even less than a dying man, but a corpse already, completely enshrouded – a corpse coming back to life once Saint-Just (the Archangel of Terror) brings him the good news about the trial and execution. And I don't have to remind you, Whose most famous trait is the resurrection.

The last thing I'd like to talk about is the scene I had already devouted a lot of thought in this post, namely the quasi-confrontation scene between Danton and Robespierre (but I have to prafec it by saying I, sadly, wasn't the one who first made the connection I am about to make, but Kazimiera Ingdahl beat me to it). If we establish that Robespierre is a stand-in for God in these plays, we also can safely assume that his negative double, Danton, is a stand-in for the opposite being: Satan. And there is an uncanny parallel between the scene in Act II, Scene 3 and the Gospel according to Matthew, Chapter 4, versets 1-11.

This cannot be a one-to-one analogy, for obvious reasons, but there is this similarity between offering an everything, which isn't yours, to a being infinitely higher than yourself, whom you both fear and perceive as someone to be adored. In tempting Robespierre, Danton also (altough probably without realisng it) tries to persuade him into giving up on life, because for Maxime to betray the Republic equals death. Please notice as well how Danton seems to honestly adress Robespierre here as someone who is not fully human: you have no human feelings, you don't even know what human feelings are (taht;s what he says in Polish; in French, for some unfathomable reason, Daniel Beauvois watered it down to "ignoring" the feelings, that is: having them, but paying them no attention, thus humanizing Robespierre even in Danton's eyes).

This now concludes my analysis. I feel sorry that it was more of an enumaration of references I spotted than a deep dive into them, but upon looking closer at them I came to a conclusion they are all focused on the one element: Robespierre's deification. There isn't that much to be said about it, then, the topic is easy (Przybyszewska accepts no contradictions to her feelings, she wants us all to see Robespierre through her admiration tinted glasses). But I hope it encourages everybody to look for references such as these in their own favourite texts. And, as always, I would just love to hear others' thoughts about it!

#I honestly think I hyped this post too much because it turns out I wasn't able to present this#(undoubtedly very inetresting topic)#in a very inetersting way :/#also please: if you have anything to say about Bible or christianity make sure it's respectful. PLEASE.#stanislawa przybyszewska#stanisława przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#maximilien robespierre#literary analysis#l'affaire danton#maksymilian robespierre#frev#jerzy danton#georges danton#Bible#christianity#biblical references

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I promise everybody this blog isn't dead, I simply have a lot of work to do.

But, having Easter break in mind, which of the following ideas would you be most interested in reading?

The first part of Noli me tangere!, which is about Robespierre's relationship with others. The "other" in question is still debatable, but I had Eleonore in mind.

An analysis of the ending of Robespierre's and Camille's fall out ("not one word too many").

An analysis of the "I would like to dance" scene.

A comparison between Saint-Just's and Robespierre's argument in The Danton Case and their making up again in Thermidor.

#if you speak out your mind on this it will sway me in the direction because i truly have so little time now but the ideas are still there#frev#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#l'affaire danton#antoine saint just#maksymilian robespierre#maximilien robespierre#probably deleting this once I post but for now i'm tentatively looking for a place to start

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ekphrasis in The Danton Case, Thermidor, and their adaptations

Ekphrasis is invoking a piece of visual media into a literary piece. It can be done for a variety of reasons, from entirely pragmatic (mostly grounding the literature in reality - if the invoked piece is a real piece of art, one you could find in a museum, for example) or more poetic (drawing some symbolic meaning between the piece of art and the idea behind the text).

In Przybyszewska's plays ekphrasis is nonexistent, at least on the foreground. I don't recall any clearly established visual, given to the readers by the original author. It's not weird in any way - how many pieces of medai do you recall which refrain from its sophisticated and additional piece of subtext and iformation? Hundreds, probably. The only other artistic thing that she has weaved into her plays is La Marseillaise, which is invoked twice in The Danton Case. There are also three book references to Othello, Orlando furioso and this one book Robespierre summarizes to Saint-Just when he's talking about hatred (but of which I have no idea if it's a real one - it probably is - or not). Other than that - nothing, plus the books count only a little, forekpfrasis should be, as I said, visual in nature.

Of course, the historical aspect of her works is what grounds them in our reality, and so cleverly, too (seeing as they're not really historical plays in any way or form, but manage to fool most anybody). And thanks to her extensive stage directions, we have no need of any additional element helping us visualize the scenes, for she does it perfectly enough on her own.

However, seein as these are plays calls for a mirror ekpfrastic effect and thus theatrical and cinematographical adapations are born. And they, on the other hand, have a potential to be filled to the brim with visual refernces. Here I would like to have a look at a few, which are taken from one of the most well known staging and the famous Wajda movie (plus some). In no particular order, there goes:

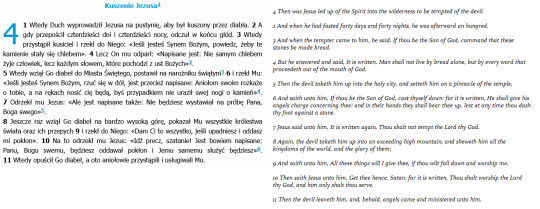

This is the very first scene of a controversial theatre adaptation of The Danton Case. Instead on portraying Robespierre as a firm leader, who only in the very end collapsed temporarily under the huge responsibility he now had to bear, the director decided to portray him as someone physically weak, not in the sense Danton meant when he called him a weakling, but in the sense of somebody who already bears so much responsibility, pain, physical ailments, doubts and whatnot. Just: everything, everythin a human could possible deal with, he deals with, and has to do so in a way that doesn't make people suspiscious about his "shortcomings". There is a interesting parallel between him and Saint-Just, whose upright and unbreakeable character is symbolised by a neck braces, something which people wear after a spine endangering accidents - and incidentally, wasn't it Saint-Just who accused Robespierre of "breaking his spine"? But not in this adaptation, oh no - here their very last scene is cut extremely short and they recite the last few sentences along with some Thermidor lines as two floating heads, a vision into the future which awaits them.

Enough about Saint-Just, though, let's focus on Robespierre and Marat. I must admit I know next to nothing about him, only what some passage here and there in this or that historical study might tell me, but I know, as does everybody, that he was known as L'ami du Peuple, which is why of the reasons, I think, why the director took this image and transposed it onto Robespierre: to make him even more likeable, to show for the umpteenth time that it is Robespierre whom we should cheer on and whom we should feel sorry for. This might also be a parallel between their both's tarnished health, their premature deaths and - last but not least - the role of an icon of the Rvolution both of them play in nowadays' audience's minds. You don't have to study history to knowwho Robespierre was, you don't have to study art to know this painting. Even if you don't agree with some more in-depth explanation of linking this person to this painting, it is a good opening image. It captures our attention in a good way.

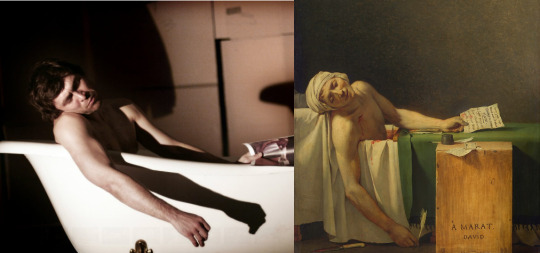

I had mention Saint-Just and there he is, in the background of the picture, symbolically assisting Danton and his clique in their last moments. Instead of shwoign them in torn shirts, the director went into another direction altogether and enshrouded them in white sheets from heads to toes, making them all look like very stereotypical ghosts, whom they will all become in just a couple of moments.

In Polish culture, the first thing that comes to mind when talking about ghosts is Dziady, an old slavic tradition that is now replaced with the Catholic All Souls Eve. Dziady is no longer, apart from perhaps some small minorities who still practice old pagan faiths, but as a ritual, they are immortalised in a play by Adam Mickiewicz, undoubtedly the greatest Polish poet ever. Everybody know this play, some scens - by heart, and they were and are being staged pretty much constantly from one point on. Needless to say, they inspire a lot of art, and I decided to show this very fmous poster by the most famous Polish poster designer, Franciszek Starowieyski…

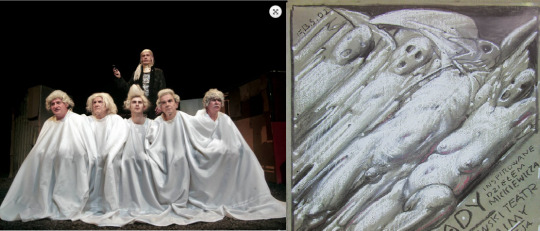

…who is important in this case, because he played David in Wajda's movie.

Not many people know - because his other carreer overshadowed by a lot his first one - that Wajda was a painter. Who actually hated his art, some of his pieces are in the national museum of contemporary art in Łódź alongside stars such as Władysław Strzemiński (the hero of Wajda's very last movie), which is a fact he absolutely detested. I dont know, nor do I care, why was that, because what matters is his previous education as an artist at the very least helped him not only to envision the visuals of the movie, but also acquainted him with great works of art. On which he could model this or that setup. I think it's a nice little detail he catsed Starowieyski as David, a real painter acting as another real painter, it adds a layer of reality onto the movie, and presumably makes for a more natural acting in the few scenes he was in his studio (I also think they look alike).

Speaking of David's studio, I once stumbled upon a lecture which drew parallels between some scenes in the movie and some paitings, which was mostly focused on character and costume design, and truth be told didn't contribute much to the overall watching experience of Danton. However, I must admit the lecturer had a very good eye in this one particular case, in which he pointed out that this quick shot in David's studio pretty obviously invokes the Fussli's The Artist's Despair Before The Grandeur Of Ancient Ruins. I don't think it's a coincidence (or at the very least, would be funny if it were) this shot is shown during the scene where Robespierre starts to grasp at desperate measures to save the country/save his own face in the trial. It is an artist's despair, only artist of a different kind. And it is a despair when being faced with a (possible) ruin of something great, even if its greatness is not yet formed, as opposed to the greatness passed.

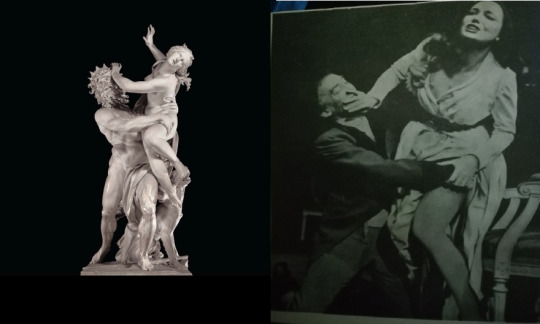

The very last example I was able to think of was this photo I found of The Danton Case from 1975. It is one of those old, very classical (I presume) adaptations, which are mostly filled to the brim with riddiculosly attractive people and very often deliberately drew from other sources of artistry, like the one pictured above. No matter what the real relationship between Louise Danton and her husband was, in the play it is portrayed as something atrocious, and I cringe whenever directors try to make it something else without good reasons for doing so, so I am very glad in the past at least they stuck with classicaly depicted acts of violation against women, not because it is a violation, but because in the classical stories (like the myth of Persephone shown in the sculpture above) the woman will usually get her revenge. Just like Przybyszewska's Louison did.

Thank you for bearing with me until the end, and if you have any other examples of this come to your mind, I compel you to share them with me!

List of pieces of art in the order of their appearance:

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat

Franciszek Starowieyski, Dziady

Jacques-Louis David, Self-portrait

Heinrich Fussli, The Artist's Despair Before The Grandeur Of Ancient Ruins

Gianlorenzo Bernini, The Rape Of Persephone

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#andrzej wajda#the danton case#sprawa dantona#thermidor#jan klata#jerzy krassowski#jacques louis david#heinrich fussli#gianlorenzo bernini#art#ekphrasis#franciszek starowieyski#painting#sculpture#ekfraza#rzeźba#sztuka#Ekphrasis is my current hobby so I had to pull this together

38 notes

·

View notes