I need a place for writing resources, and also posting things when NaNo starts. I'm doing it this year, yes.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Q&A: Fear is Instinct, Understanding is a Weapon

Anonymous said to howtofightwrite:

“If you fear your own sword you cannot fight” – this concept sometimes shows up. Is it real? If so, how are students/trainees/apprentices taught to work through it?

This one is actually real. If you’re afraid of your weapon, no matter what that weapon is (including your own body), you cannot wield it effectively. This is true for all weapons, including guns, swords, staves, hand to hand, everything. It doesn’t matter.

The reason why is it’s difficult to fight an opponent, but it’s even more difficult to fight yourself and your opponent at the same time. You split your concentration, you lean back, you break focus, you flinch, your stance is terrible, you’re tentative rather than cautious or you overcompensate. The same is true if you’re afraid of getting hit.

Respect your weapon, but don’t fear it.

If you don’t respect your weapon, the power it holds, and the destruction it can inflict, then you’re likely to misuse it. If you’re frightened of your weapon, it’ll get you killed.

A good way to understand this concept is to start with hand to hand. A lot of beginners are frightened of getting hit. You can probably grasp why without experiencing the actual event. Getting punched or kicked hurts. Punching someone else hurts too. Before we even move to the emotional or spiritual impact, let me make this clear: on a purely physical level, violence hurts you coming and going. If two people fight, no matter their skill level, both are going to get hurt. The question is, how much more will one person be hurt than the other? The one who gets hurt less is the winner.

Fear is a natural response to the expectation of experiencing pain. Fear is your body instinctively trying to defend you from harm. When you flinch, your eyes close, you tuck inward, your muscles (your body’s natural armor) tense up to take the hit. This is all a natural, instinctual attempt to limit the damage. You don’t want to get hurt, getting hurt sucks. It’s dangerous. If you get injured too badly, you could lose substantial elements of your life that you take for granted. Your mind is always making risk based assessments in dangerous situations. It will instruct your body to react in accordance with baseline instinct because that is what it knows how to do.

So, if you are afraid of your weapon, you will respond to that fear while trying to use the weapon.

Let me give you an example with a weapon that’s easier to understand without experience than a sword: the modern handgun.

Handguns are loud. They are noisy. They smell. When they fire, if they’re not properly controlled, they will snap back toward your face on the recoil. So, what does someone who is afraid of a gun do? They do what’s natural. They lean away from it. When you are afraid, you naturally want as much distance from the object causing that fear as you can get. The person holding the gun does so with one hand, their arm extends way out, their upper torso leans back out of balance with their lower body, their eyes narrow. When the gun fires, they flinch. Their eyes close, they lose sight of their target, the uncontrolled muzzle jerks upward and the bullet flies on a different path than the one they intended. The bullet is more likely to miss or, worse, hit a target they didn’t intend. Their fear cost them control and concentration.

The irony is this happens with all weapons when you’re afraid, including hand to hand combat. The physical reaction differs slightly, but the same baseline occurs — leaning back, flinching, squeezing the eyes shut, tensing up. In the worst case scenario, the individual will turn away or roll over in an instinctual attempt to defend the most important part of their body. The reason you get virtually the same reaction regardless of weapon type is because the human fear response is natural instinct.

If you just went, but, wait, Michi, isn’t violence natural instinct too?

No.

Aggression, yes, that’s natural. Society and media teach us that expressions of violence like punches and kicks are a natural part of the human condition, and that’s fantasy. Being exposed to violence from an early age, a lot of people will try to mimic what they see, but you can’t really fight effectively in accordance with modern understanding until you’re trained. Martial combat is science. Martial combat is unnatural. You’re trained to act in opposition to your natural instincts like your fear response or your response to anger.

You overcome fear with familiarity. You replace the unknown with understanding. You retrain your instincts through conditioning. With practice and repetition, you change everything. The way you think, the way you move, the way you observe your environment, the way you react physically, mentally, and emotionally to stress. A large portion of martial training is about getting you accustomed to physical discomfort. This is where the general misunderstanding about martial training and pain comes from. Learning to differentiate between physical discomfort and real damage is vital. You will be hurt while fighting, but understanding the difference between a bruise and a torn muscle can save your life. In the same way, understanding your body, knowing where to hit, how to hit, and what hurts when hit, allows you to better formulate strategies to defeat your opponent. As you become more effective, streamlining your physical movements and prioritizing targets allows you to conserve more energy meaning you can either fight longer or have enough gas left in the tank to escape.

Martial combat also teaches you to capitalize on and even induce this same fear response in someone else then use that reaction to your advantage. A basic example of that is: I flick my hand at your face to get you to flinch (you see an object flying toward your face, your eyes instinctively close to protect them) and punch you in the stomach instead. That’s not natural, that’s tactical.

The same principle applies to weapons. The difference is there’s more danger associated with weapons because weapons are designed to end lives. This is true even if you’re using your weapon for self-defense. In the process of defending your own life, you may take someone else’s. That’s not a judgement. That’s reality. Weapons are designed to kill people, it is natural to be afraid of them, coming to terms with that reality and respecting the damage your weapon can do (and the damage you can inflict with it) is part of wielding weapons effectively.

Again, you overcome fear through familiarity. This is what training is for. Those long hours practicing your stances and physical movements, learning about your weapon by learning to care for it. Endless repetition until those techniques, those movements from stacking mags to drawing your gun to aiming become a natural part of you. You train until your sword becomes an extension of your arm, so you know intuitively where it is at all times. You repeat the same action over and over and over again until the action is part of you so when the stimulus is applied you react without thinking.

The motions and training for these weapons, even weapons within an individual family or with some similarity, will be different. You can’t pick up a pistol and expect it to be the same as every other pistol. There are different makes, different models, different types, and the subtle differences between them can be a gamechanger. You can’t pick up a rapier and expect to wield it like a longsword. You can’t pick up a smallsword and expect to wield it exactly like a rapier. The saber and the epee are similar, with some crossover, but different weapons. The military saber used in Britain during the 1800s and 1900s is a different animal from the modern fencing saber. Training in one is not training for all and training in one style is not an automatic counter to every other.

The problem with familiarity, of course, is that the reverse is also true. After all, familiarity breeds contempt and it is just as dangerous to become too comfortable with your weapon. People who are too comfortable lose respect for their weapon’s power, forgetting the ever present danger both to themselves and to the people around them. They treat the weapon like a toy. Screwing around is how people get hurt.

A weapon is always dangerous, no matter who holds it. Weapons are never 100% safe. However, in the hands of someone who respects it and who understands it, the risks are reduced to the people around them.

You overcome fear of a weapon the way you overcome fear of anything else, through knowledge of what it is, how it works, what it can do and what it can’t do, through understanding, through practice, and eventually via familiarity. It is very difficult to be frightened of something you know and understand, especially when an object with no will of its own. At that point, you’re no longer frightened by the gun or sword when it’s in your hand. It could be a different story when it’s in someone else’s.

-Michi

This blog is supported through Patreon. If you enjoy our content, please consider becoming a Patron. Every contribution helps keep us online, and writing. If you already are a Patron, thank you.

Q&A: Fear is Instinct, Understanding is a Weapon was originally published on How to Fight Write.

468 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Techniques: Fight Scenes and Clarity

kerzoro said to howtofightwrite:

What would you say at the writing techniques to write a fight? I’ve received (what I feel is valid) criticism that my action scenes need to be punchier and feel too passive, but I’m not 100% what that means, or how to translate that to paper.

What your critique partners are telling you is that you’ve got issues with passive voice which is a common problem for new writers. Passive voice is an overuse of the subject acting on the verb rather than the verb being acted upon.

Passive Voice

She was chased.

Active Voice

He chased her.

Now, both passive and active voice have their uses in writing and can be applied to great effect under the right circumstances. Some writing advice will tell you to rid yourself of passive voice entirely, never use “was”, “were”, “felt”, “is”, etc. While the advice is useful in encouraging you to practice your active voice, it can result in your writing falling out of balance. Passive voice is excellent for framing within a scene while active voice is solid for action. Overuse of active voice can lead to reader fatigue. You want to find a balance between the two which creates a solid rhythm.

However, this is basic advice you can get from any writing blog. Many blogs will tell you that the key to writing a good action scene is to use active voice, make your sentences shorter, raise the tempo of your sentences so the pace quickens and tension increases. These are all good techniques and well worth the effort to develop.

To really succeed at writing action sequences, you need to look beyond surface prose and dig deeper. This involves learning about both real world combat and action created for entertainment. Both have different purposes, but one informs the other by providing you with more options and ways to structure your scenes.

The major failures of most action sequences revolve around lack of clarity.

Clarity of Understanding.

Clarity of Visual Image.

Clarity Setting Reader Expectations

“How” and “Why” Create Worlds

If you don’t understand what’s happening in your narrative and why then you cannot write your story. Narratives are built on cause and effect. Actions happen and a result occurs, these actions large or small build your story. Fight scenes, down to individual actions, are the same way — action happens, result occurs.

If your critique partner is telling you that your fight scenes should be punchier, you’re not just lacking in sentence structure, your imagery and stakes are also suffering.

The problem for most writers when they sit down to write fight scenes is they don’t really understand the material they’re working with. Whether this involves the reasons and motivations for conflict (why does the bully start a fight with a male protagonist in a bar?), or the mechanics of violence itself (what happens when you punch someone?). Despite consuming violent media for most of your life, if you’ve never considered the mechanics of violence in depth, choreographing violence in your narrative is difficult.

Make no mistake. When you are crafting a fight scene in your narrative, you are choreographing a sequence like one would performance art. When a critic stresses the importance of realism, you shouldn’t chase the real world blindly. You failed to set appropriate expectations for your reader and abide by your own rules. No reader really cares about the real world, they care about suspension of disbelief. Learning how things work helps build suspension of disbelief.

For example: if your amazing military general understands nothing about troop movements, military structure, supplies lines, army bureaucracy, the role of spies, interaction with the ruling governing body, etc, then both your character and your world building will suffer. As a result, your suspension of disbelief also suffers.

The goal is not to mimic, duplicate, or import a real world individual or military wholesale, but rather to learn how and why different militaries throughout history (successful and unsuccessful) worked the way they did. From how and why, you can create. Your way doesn’t need to be the best way, the most perfect way, it can be the way that evolved because these individuals had access to these resources to create this culture.

If you’re wondering why I’m talking about world building on a post about writing techniques for fight scenes, the answer is: your character’s culture and the resources they have access to defines how they fight just as much as their personality. How they choose to fight defines their portion of your action sequence. Violence is an expression of identity.

The Parry, Parry, Thrust, Thrust Conundrum

Many fiction writers treat all swords as the same. In reality, less than half a centimeter of distance can be the difference between victory and defeat with bladed weapons.

Why is this piece of information important?

If your answer was: whoever has the longer weapon wins. Well, you’re wrong.

Understanding a weapon’s designated use, it’s strengths and limitations works as a means of setting reader expectations which builds your narrative’s stakes.

A character taking a scimitar into a narrow alley is going to be different from a character taking a rapier into the same narrow alley. In fact, a character with a rapier might choose to lure the character with the scimitar into a narrow alley because they feel choice of terrain benefits them.

This one choice transforms a character from passive into active. The character makes decisions based on the information they have available. They may make the wrong choice, but the choice itself creates an active participant. You cannot make educated choices without knowledge. The more knowledge you have, the more information you have, the smarter and more interesting your setting becomes.

Take these two characters discussing the use of a specialty weapon — a lasbow, which shoots psychically generated lasers bolts.

Suits you, Nathan’s warm thoughts filled her. You could’ve killed that spino with a carefully constructed shot.

Yes, she grit her teeth, but lasbows require more concentration, expend more energy, and bolts fly only so far as imagination and focus allow. A plaspistol just needs a charge.

Here, we see the character lay out the strengths and drawbacks of a lasbow before we see the weapon in combat. We know a lasbow is different from a regular bow. While a lasbow can strike a target at any distance with devastating effect, it is not fire and forget. The wielder must maintain the shot from start to finish. This is a significant weakness in frantic melee if the wielder is not shooting from a defensive position. If the difference between life and death is losing concentration, that might be a little worrying.

Now, let’s see the lasbow in action.

Together, the rexes lumbered into the canyon. Humans perched on saddles atop their massive heads. The rexes were armored in saurohide and plasteel pieces reconfigured from ancient dragon and carno armor.

Leah raised her bow. The rexes’ large nasal cavity allowed them to locate prey from across great distances. Some bonded raiders learned to utilize this sense to locate caravans and other enemies. Probably how they found us. A sharp whine filled her ears, the buzz of electricity. And riding reconditioned fly-bikes. Six humans rode two per vehicle. One driver, one gunner, bikes with built-in weaponswere difficult to come by without a technician. Surprise. Distract. Overwhelm. Simple tactics; terrify and distract with the tyrannosaurus while the bikes and raptors cut the enemy to pieces. Effective against the inexperienced.

Patterning the mental signature of the rex rider on the left, Leah generated her bolt by drawing two fingers through the air. The bolt burst to life in a crackling, snapping hiss of blazing yellow. She fired. The bolt shot through the trees, searing away fronds and leaves.

The rex rider sensed her touch. Their rifle raised, eyes scanning the canyon.

Female. She caged the woman’s mind. No alarms. The bolt pierced through the center of the rider’s helmeted forehead, sliced through the brain, and vanished.

The tyrannosaur’s rider slumped, corpse held in place by saddle straps.

The rex bellowed in agony.

Surprise shook the human minds. Too late. They were committed.

Leah smiled. Let’s go.

Multiple important details occur in this scene.

The enemy is defined and the main character, Leah, instructs the reader regarding the raiders’ intended tactics. This builds anticipation for the battle to come.

The preemptive strike with the lasbow is launched, but Leah also cages the mind of her target to keep them from psychically warning the others. Tactics.

Strategy is also at play, Leah waits until the raiders advancing force is in too deep and cannot retreat when they realize their enemy’s strength. She kills the rex’s rider rather than the rex to create a battlefield wild card, cutting off the only easy escape route.

Leah’s confidence at the end of the scene builds the reader’s sense of security for the coming battle.

A character’s actions can be multi-pronged while the effects of those actions have multiple outcomes. If the world you create is convincing and works off its own logic, you don’t have to worry about it matching reality. If you understand how different kinds of violence work, you can create clear images within your scene that are advanced beyond punches and kicks.

The reason why I generally suggest looking at films rather than novels for your action sequences is because films have the advantage of being choreographed by professionals. As a writer, you’ll never be able to really make use of the same visual spectacle, but the important point is a fight scene choreographer’s business is choreographing fight scenes for entertainment. Whether you’re watching Spiderman, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, or Heat, you’re given the opportunity to see a martial artist’s mind at work constructing action in the service of a greater narrative. As a creative who lacks similar experience, you can review a lot of good and bad fight scenes from the famous to the unknown. You can see what worked and what didn’t. You’ve been consuming film fight scenes non-critically for most of your life, now it’s time for you to start learning about the choreographers who created them, figuring out how they work and why.

I’m not suggesting you mindlessly copy, but carefully consider. Each action sequence is an expression of all your characters.

– Michi

This blog is supported through Patreon. If you enjoy our content, please consider becoming a Patron. Every contribution helps keep us online, and writing. If you already are a Patron, thank you.

Writing Techniques: Fight Scenes and Clarity was originally published on How to Fight Write.

738 notes

·

View notes

Text

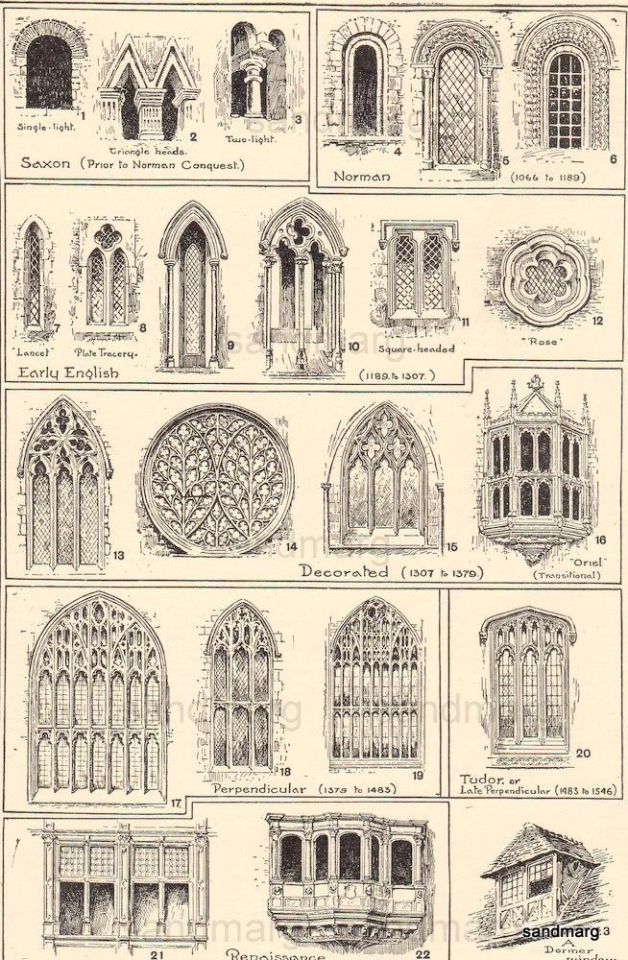

Fantasy Guide to Architecture

This post has been waiting on the back burner for weeks and during this time of quarantine, I have decided to tackle it. This is probably the longest post I have ever done. I is very tired and hope that I have covered everything from Ancient times to the 19th Century, that will help you guys with your worldbuilding.

Materials

What you build with can be determined by the project you intend, the terrain you build on and the availability of the material. It is one characteristic that we writers can take some some liberties with.

Granite: Granite is an stone formed of Igneous activity near a fissure of the earth or a volcano. Granites come in a wide range of colour, most commonly white, pink, or grey depending on the minerals present. Granite is hard and a durable material to build with. It can be built with without being smoothed but it looks bitchin' and shiny all polished up.

Marble: Probably everyone's go to materials for building grand palaces and temples. Marble is formed when great pressure is placed on limestone. Marble can be easily damaged over time by rain as the calcium in the rock dissolves with the chemicals found in rain. Marble comes in blue, white, green, black, white, red, gray and yellow. Marble is an expensive material to build with, highly sought after for the most important buildings. Marble is easy to carve and shape and polishes to a high gleam. Marble is found at converging plate boundaries.

Obsidian: Obsidian is probably one of the most popular stones mentioned in fantasy works. Obsidian is an igneous rock formed of lava cooling quickly on the earth's surfaces. Obsidian is a very brittle and shiny stone, easy to polish but not quite a good building material but a decorative one.

Limestone: Limestone is made of fragments of marine fossils. Limestone is one of the oldest building materials. Limestone is an easy material to shape but it is easily eroded by rain which leads most limestone monuments looking weathered.

Concrete: Concrete has been around since the Romans. Concrete is formed when aggregate (crushed limstone, gravel or granite mixed with fine dust and sand) is mixed with water. Concrete can be poured into the desired shape making it a cheap and easy building material.

Brick: Brick was one of history's most expensive materials because they took so long to make. Bricks were formed of clay, soil, sand, and lime or concrete and joined together with mortar. The facade of Hampton Court Palace is all of red brick, a statement of wealth in the times.

Glass: Glass is formed of sand heated until it hardens. Glass is an expensive material and for many years, glass could not be found in most buildings as having glass made was very expensive.

Plaster: Plaster is made from gypsum and lime mixed with water. It was used for decoration purposes and to seal walls. A little known fact, children. Castle walls were likely painted with plaster or white render on the interior.

Wattle and Daub: Wattle and daub is a building material formed of woven sticks cemented with a mixture of mud, one of the most common and popular materials throughout time.

Building terms

Arcade: An arcade is a row of arches, supported by columns.

Arch: An arch is a curved feature built to support weight often used for a window or doorway.

Mosaic: Mosaics are a design element that involves using pieces of coloured glass and fitted them together upon the floor or wall to form images.

Frescos: A design element of painting images upon wet plaster.

Buttress: A structure built to reinforce and support a wall.

Column: A column is a pillar of stone or wood built to support a ceiling. We will see more of columns later on.

Eave: Eaves are the edges of overhanging roofs built to allow eater to run off.

Vaulted Ceiling: The vaulted ceilings is a self-supporting arched ceiling, than spans over a chamber or a corridor.

Colonnade: A colonnade is a row of columns joined the entablature.

Entablature: a succession of bands laying atop the tops of columns.

Bay Window: The Bay Window is a window projecting outward from a building.

Courtyard/ Atrium/ Court: The courtyard is an open area surrounded by buildings on all sides

Dome: The dome resembles a hollow half of a sphere set atop walls as a ceiling.

Façade: the exterior side of a building

Gable: The gable is a triangular part of a roof when two intersecting roof slabs meet in the middle.

Hyphen: The hyphen is a smaller building connecting between two larger structures.

Now, let's look at some historical building styles and their characteristics of each Architectural movement.

Classical Style

The classical style of Architecture cannot be grouped into just one period. We have five: Doric (Greek), Ionic (Greek), Corinthian (Greek), Tuscan (Roman) and Composite (Mixed).

Doric: Doric is the oldest of the orders and some argue it is the simplest. The columns of this style are set close together, without bases and carved with concave curves called flutes. The capitals (the top of the column) are plain often built with a curve at the base called an echinus and are topped by a square at the apex called an abacus. The entablature is marked by frieze of vertical channels/triglyphs. In between the channels would be detail of carved marble. The Parthenon in Athens is your best example of Doric architecture.

Ionic: The Ionic style was used for smaller buildings and the interiors. The columns had twin volutes, scroll-like designs on its capital. Between these scrolls, there was a carved curve known as an egg and in this style the entablature is much narrower and the frieze is thick with carvings. The example of Ionic Architecture is the Temple to Athena Nike at the Athens Acropolis.

Corinthian: The Corinthian style has some similarities with the Ionic order, the bases, entablature and columns almost the same but the capital is more ornate its base, column, and entablature, but its capital is far more ornate, commonly carved with depictions of acanthus leaves. The style was more slender than the others on this list, used less for bearing weight but more for decoration. Corinthian style can be found along the top levels of the Colosseum in Rome.

Tuscan: The Tuscan order shares much with the Doric order, but the columns are un-fluted and smooth. The entablature is far simpler, formed without triglyphs or guttae. The columns are capped with round capitals.

Composite: This style is mixed. It features the volutes of the Ionic order and the capitals of the Corinthian order. The volutes are larger in these columns and often more ornate. The column's capital is rather plain. for the capital, with no consistent differences to that above or below the capital.

Islamic Architecture

Islamic architecture is the blanket term for the architectural styles of the buildings most associated with the eponymous faith. The style covers early Islamic times to the present day. Islamic Architecture has some influences from Mesopotamian, Roman, Byzantine, China and the Mongols.

Paradise garden: As gardens are an important symbol in Islam, they are very popular in most Islamic-style buildings. The paradise gardens are commonly symmetrical and often enclosed within walls. The most common style of garden is split into four rectangular with a pond or water feature at the very heart. Paradise gardens commonly have canals, fountains, ponds, pools and fruit trees as the presence of water and scent is essential to a paradise garden.

Sehan: The Sehan is a traditional courtyard. When built at a residence or any place not considered to be a religious site, the sehan is a private courtyard. The sehan will be full of flowering plants, water features snd likely surrounded by walls. The space offers shade, water and protection from summer heat. It was also an area where women might cast off their hijabs as the sehan was considered a private area and the hijab was not required. A sehan is also the term for a courtyard of a mosque. These courtyards would be surrounded by buildings on all sides, yet have no ceiling, leaving it open to the air. Sehans will feature a cleansing pool at the centre, set under a howz, a pavilion to protect the water. The courtyard is used for rituals but also a place of rest and gathering.

Hypostyle Hall: The Hypostyle is a hall, open to the sky and supported by columns leading to a reception hall off the main hall to the right.

Muqarnas : Muqarnas is a type of ornamentation within a dome or a half domed, sometimes called a "honeycomb", or "stalactite" vaulted ceiling. This would be cast from stone, wood, brick or stucco, used to ornament the inside of a dome or cupola. Muqarnas are used to create transitions between spaces, offering a buffer between the spaces.

African Architecture

African Architecture is a very mixed bag and more structurally different and impressive than Hollywood would have you believe. Far beyond the common depictions of primitive buildings, the African nations were among the giants of their time in architecture, no style quite the same as the last but just as breathtaking.

Somali architecture: The Somali were probably had one of Africa's most diverse and impressive architectural styles. Somali Architecture relies heavy on masonry, carving stone to shape the numerous forts, temples, mosques, royal residences, aqueducts and towers. Islamic architecture was the main inspiration for some of the details of the buildings. The Somali used sun-dried bricks, limestone and many other materials to form their impressive buildings, for example the burial monuments called taalo

Ashanti Architecture: The Ashanti style can be found in present day Ghana. The style incorporates walls of plaster formed of mud and designed with bright paint and buildings with a courtyard at the heart, not unlike another examples on this post. The Ashanti also formed their buildings of the favourite method of wattle and daub.

Afrikaner Architecture: This is probably one of the oddest architectural styles to see. Inspired by Dutch settlers (squatters), the buildings of the colony (planters/squatters) of South Africa took on a distinctive Dutch look but with an Afrikaner twist to it making it seem both familiar and strange at the same time.

Rwandan Architecture: The Rwandans commonly built of hardened clay with thatched roofs of dried grass or reeds. Mats of woven reeds carpeted the floors of royal abodes. These residences folded about a large public area known as a karubanda and were often so large that they became almost like a maze, connecting different chambers/huts of all kinds of uses be they residential or for other purposes.

Aksumite Architecture: The Aksumite was an Empire in modern day Ethiopia. The Aksumites created buildings from stone, hewn into place. One only has to look at the example of Bete Medhane Alem to see how imposing it was.

Yoruba Architecture: Yoruba Architecture was made by earth cured until it hardened enough to form into walls, or they used wattle and daub, roofed by timbers slats coated in woven grass or leaves. Each unit divided up parts of the buildings from facilities to residences, all with multiple entrances, connected together.

Igbo Architecture: The Igbo style follows some patterns of the Yoruba architecture, excepting that there are no connected walls and the spacing is not so equal. The closer a unit was to the centre, the more important inhabitants were.

Hausa architecture: Hausa Architecture was formed of monolithic walls coated in plaster. The ceilings and roof of the buildings were in the shape of small domes and early vaulted ceilings of stripped timber and laterite. Hausa Architecture features a single entrance into the building and circular walls.

Nubian Architecture: Nubia, in modern day Ethiopia, was home to the Nubians who were one of the world's most impressive architects at the beginning of the architecture world and probably would be more talked about if it weren't for the Egyptians building monuments only up the road. The Nubians were famous for building the speos, tall tower-like spires carved of stone. The Nubians used a variety of materials and skills to build, for example wattle and daub and mudbrick. The Kingdom of Kush, the people who took over the Nubian Empire was a fan of Egyptian works even if they didn't like them very much. The Kushites began building pyramid-like structures such at the sight of Gebel Barkal

Egyptian Architecture: The Egyptians were the winners of most impressive buildings for s good while. Due to the fact that Egypt was short on wood, Ancient Egyptians returned to building with limestone, granite, mudbrick, sandstone which were commonly painted with bright murals of the gods along with some helpful directions to Anubis's crib. The Egyptians are of course famous for their pyramids but lets not just sit on that bandwagon. Egyptian Architecture sported all kinds of features such as columns, piers, obelisks and carving buildings out of cliff faces as we see at Karnak. The Egyptians are cool because they mapped out their buildings in such a way to adhere to astrological movements meaning on special days if the calendar the temple or monuments were in the right place always. The Egyptians also only build residences on the east bank of the Nile River, for the opposite bank was meant for the dead. The columns of Egyptian where thicker, more bulbous and often had capitals shaped like bundles of papyrus reeds.

Chinese Architecture

Chinese Architecture is probably one of the most recognisable styles in the world. The grandness of Chinese Architecture is imposing and beautiful, as classical today as it was hundreds of years ago.

The Presence of Wood: As China is in an area where earthquakes are common, most of the buildings are were build of wood as it was easy to come across and important as the Ancient Chinese wanted a connection to nature in their homes.

Overhanging Roofs: The most famous feature of the Chinese Architectural style are the tiled roofs, set with wide eaves and upturned corners. The roofs were always tiled with ceramic to protect wood from rotting. The eaves often overhung from the building providing shade.

Symmetrical Layouts: Chinese Architecture is symmetrical. Almost every feature is in perfect balance with its other half.

Fengshui: Fengshui are philosophical principles of how to layout buildings and towns according to harmony lain out in Taoism. This ensured that the occupants in the home where kept in health, happiness, wealth and luck.

One-story: As China is troubled by earthquakes and wood is not a great material for building multi-storied buildings, most Chinese buildings only rise a single floor. Richer families might afford a second floor but the single stories compounds were the norm.

Orientation: The Ancient Chinese believed that the North Star marked out Heaven. So when building their homes and palaces, the northern section was the most important part of the house and housed the heads of the household.

Courtyards: The courtyard was the most important area for the family within the home. The courtyard or siheyuan are often built open to the sky, surrounded by verandas on each side.

Japanese Architecture

Japanese Architecture is famous for its delicacy, smooth beauty and simplistic opulence. Japanese Architecture has been one of the world's most recognisable styles, spanning thousands of years.

Wood as a Common Material: As with the Chinese, the most popular material used by the Japanese is wood. Stone and other materials were not often used because of the presence of earthquakes. Unlike Chinese Architecture, the Japanese did not paint the wood, instead leaving it bare so show the grain.

Screens and sliding doors: The shoji and fusuma are the screens and sliding doors are used in Japanese buildings to divide chambers within the house. The screens were made of light wood and thin parchment, allowing light through the house. The screens and sliding doors were heavier when they where used to shutter off outside features.

Tatami: Tatami mats are used within Japanese households to blanket the floors. They were made of rice straw and rush straw, laid down to cushion the floor.

Verandas: It is a common feature in older Japanese buildings to see a veranda along the outside of the house. Sometimes called an engawa, it acted as an outdoor corridor, often used for resting in.

Genkan: The Genkan was a sunken space between the front door and the rest of the house. This area is meant to separate the home from the outside and is where shoes are discarded before entering.

Nature: As both the Shinto and Buddhist beliefs are great influences upon architecture, there is a strong presence of nature with the architecture. Wood is used for this reason and natural light is prevalent with in the home. The orientation is meant to reflect the best view of the world.

Indian Architecture

India is an architectural goldmine. There are dozens of styles of architecture in the country, some spanning back thousands of years, influenced by other cultures making a heady stew of different styles all as beautiful and striking as the last.

Mughal Architecture: The Mughal architecture blends influences from Islamic, Persian along with native Indian. It was popular between the 16th century -18th century when India was ruled by Mughal Emperors. The Taj Mahal is the best example of this.

Indo-Saracenic Revival Architecture: Indo Saracenic Revival mixes classical Indian architecture, Indo-Islamic architecture, neo-classical and Gothic revival of the 1800s.

Cave Architecture: The cave architecture is probably one of the oldest and most impressive styles of Indian architecture. In third century BC, monks carved temples and buildings into the rock of caves.

Rock-Cut Architecture: The Rock-cut is similar to the cave style, only that the rock cut is carved from a single hunk of natural rock, shaped into buildings and sprawling temples, all carved and set with statues.

Vesara Architecture: Vesara style prevalent in medieval period in India. It is a mixture of the Dravida and the Nagara styles. The tiers of the Vesara style are shorter than the other styles.

Dravidian Architecture: The Dravidian is the southern temple architectural style. The Kovils are an example of prime Dravidian architecture. These monuments are of carved stone, set up in a step like towers like with statues of deities and other important figures adorning them.

Kalinga Architecture: The Kalinga style is the dominant style in the eastern Indian provinces. The Kalinga style is famous for architectural stipulations, iconography and connotations and heavy depictions of legends and myths.

Sikh Architecture: Sikh architecture is probably the most intricate and popular of the styles here. Sikh architecture is famous for its soft lines and details.

Romanesque (6th -11th century/12th)

Romanesque Architecture is a span between the end of Roman Empire to the Gothic style. Taking inspiration from the Roman and Byzantine Empires, the Romanesque period incorporates many of the styles.

Rounded arches: It is here that we see the last of the rounded arches famous in the classical Roman style until the Renaissance. The rounded arches are very popular in this period especially in churches and cathedrals. The rounded arches were often set alongside each other in continuous rows with columns in between.

Details: The most common details are carved floral and foliage symbols with the stonework of the Romanesque buildings. Cable mouldings or twisted rope-like carvings would have framed doorways.

Pillars: The Romanesque columns is commonly plainer than the classical columns, with ornate captials and plain bases. Most columns from this time are rather thick and plain.

Barrel Vaults: A barrel vaulted ceiling is formed when a curved ceiling or a pair of curves (in a pointed ceiling). The ceiling looks rather like half a tunnel, completely smooth and free of ribs, stone channels to strengthen the weight of the ceiling.

Arcading: An arcade is a row of arches in a continual row, supported by columns in a colonnade. Exterior arcades acted as a sheltered passage whilst inside arcades or blind arcades, are set against the wall the arches bricked, the columns and arches protruding from the wall.

Gothic Architecture (12th Century - 16th Century)

The Gothic Architectural style is probably one of the beautiful of the styles on this list and one of most recognisable. The Gothic style is a dramatic, opposing sight and one of the easiest to describe.

Pointed arch: The Gothic style incorporates pointed arches, in the windows and doorways. The arches were likely inspired by pre-Islamic architecture in the east.

Ribbed vault: The ribbed vault of the Gothic age was constructed of pointed arches. The trick with the ribbed vaulted ceiling, is that the pointed arches and channels to bear the weight of the ceiling.

Buttresses: The flying buttress is designed to support the walls. They are similar to arches and are connected to counter-supports fixed outside the walls.

Stained-Glass Window: This is probably one of the most recognisable and beautiful of the Gothic features. They can be set in round rose windows or in the pointed arches.

Renaissance Architecture (15th Century- 17th Century)

Renaissance architecture was inspired by Ancient Roman and Greek Architecture. Renaissance Architecture is Classical on steroids but has its own flare. The Renaissance was a time for colour and grandeur.

Columns and pilasters: Roman and Greek columns were probably the greatest remix of the Renaissance period. The architecture of this period incorporated the five orders of columns are used: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite. The columns were used to hold up a structure, support ceilings and adorn facades. Pilasters were columns within a chamber, lining the walls for pure decoration purposes.

Arches: Arches are rounded in this period, having a more natural semi-circular shape at its apex. Arches were a favourite feature of the style, used in windows, arcades or atop columns.

Cupola: Is a small dome-like tower atop a bigger dome or a rooftop meant to allow light and air into the chamber beneath.

Vaulted Ceiling/Barrel Vault: Renaissance vaulted ceilings do not have ribs. Instead they are semi-circular in shape, resting upon a square plain rather than the Gothic preference of rectangular. The barrel vault held by its own weight and would likely be coated in plaster and painted.

Domes: The dome is the architectural feature of the Renaissance. The ceiling curves inwards as it rises, forming a bowl like shape over the chamber below. The dome's revival can be attributed to Brunelleschi and the Herculean feat of placing a dome on the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore. The idea was later copied by Bramante who built St. Peter's Basilica.

Frescos: To decorate the insides of Renaissance buildings, frescos (the art of applying wet paint to plaster as it dries) were used to coat the walls and ceilings of the buildings. The finest frescos belong to Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel.

Baroque (1625–1750)

Baroque incorporates some key features of Renaissance architecture, such as those nice columns and domes we saw earlier on. But Baroque takes that to the next level. Everything is higher, bigger, shinier, brighter and more opulent. Some key features of Baroque palaces and buildings would be:

Domes: These domes were a common feature, left over from the Renaissance period. Why throw out a perfectly good bubble roof, I ask you? But Baroque domes were of course, grander. Their interiors were were nearly always painted or gilded, so it drew the eye upwards which is basically the entire trick with Baroque buildings. Domes were not always round in this building style and Eastern European buildings in Poland and Ukraine for example sport pear-shaped domes.

Solomonic columns: Though the idea of columns have been about for years but the solomonic columns but their own twist on it. These columns spiral from beginning to end, often in a s-curved pattern.

Quadratura: Quadratura was the practice of painting the ceilings and walls of a Baroque building with trompe-l'oeil. Most real life versions of this depict angels and gods in the nude. Again this is to draw the eye up.

Mirrors: Mirrors came into popularity during this period as they were a cool way to create depth and light in a chamber. When windows faced the mirrors on the wall, it creates natural light and generally looks bitchin'. Your famous example is the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.

Grand stairways: The grand sweeping staircases became popular in this era, often acting as the centre piece in a hall. The Baroque staircase would be large and opulent, meant for ceremonies and to smoother guests in grandeur.

Cartouche: The cartouche is a design that is created to add some 3D effect to the wall, usually oval in shape with a convex surface and edged with scrollwork. It is used commonly to outline mirrors on the wall or crest doorways just to give a little extra opulence.

Neoclassical (1750s-19th century)

The Neoclassical Period involved grand buildings inspired by the Greek orders, the most popular being the Doric. The main features of Neoclassical architecture involve the simple geometric lines, columns, smooth walls, detailing and flat planed surfaces. The bas-reliefs of the Neoclassical style are smoother and set within tablets, panels and friezes. St. Petersburg is famous for the Neoclassical styles brought in under the reign of Catherine the Great.

Greek Revival (late 18th and early 19th century)

As travel to other nations became easier in this time period, they became to get really into the Ancient Greek aesthetic. During this architectural movement they brought back the gabled roof, the columns and the entablature. The Greek Revival was more prevalent in the US after the Civil War and in Northern Europe.

Hope this helps somewhat @marril96

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

Building Narrative Tension: How to Keep Your Fight Scenes Interesting

Let me start by saying that violence by itself is actually rather dull.

I’m talking, of course, about fictional violence. Fictional violence is meaningless until given meaning by it’s creator.

Have you ever asked yourself, why violence is terrifying? If you haven’t, ask yourself that question. Why is violence so frightening?

Answer that question for yourself, in detail. Now, don’t just settle for one answer or a broad answer. Keep digging until you get specific, until you get personal.

One of the major problems writers face when writing violence is the assumption that the violence or the act of violence is going to do the work for them. The truth is, it won’t. You’re going to need to put in the effort to move your characters from stick figures slapping each other to people with meaningful goals and stakes. Action means nothing without emotions to hook into, without costs and consequences.

So, again, why is violence scary?

Think about your favorite fight scenes either in written fiction, comics, or in film. Consider why it works for you. Why were you invested? Why did you care?

You’ll probably have different answers depending on the scene you chose, but behind each one, you’ll find a host of them. Those which are overarching in terms of plot, those which are personal on the character level. Goals. Desires. Stakes.

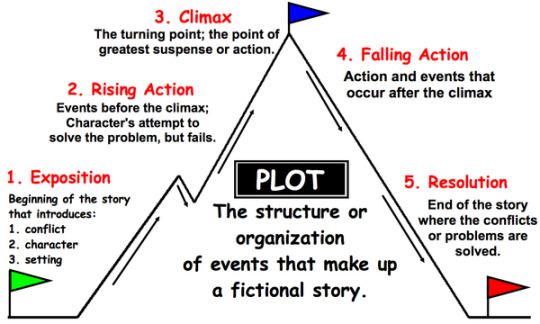

Part of the reason why it is so hard to provide good examples of fight scenes, (just like every other fictional scene, really) is that the real impact isn’t actually in act of the violence itself. In fiction, a fight scene is actually a climax, a culmination, and release of the tension built up in prior scenes. You might immediately think of a climactic battle at the end of a narrative like the Battle of Gondor, but it can be as small as two people arguing in a bar until one of them hits the other across the face with a glass mug.

A is standing at the bar, chatting with their friends. They’re a little tipsy, they’ve been drinking, but they’re not so drunk as to have lost all cognitive or motor function.

Enter B, at a nearby table with their companions. B is a mercenary from a unit garrisoned just outside of town. B gets up from the table and goes to the bar. B elbows A’s friend, a member of the local militia aside to order from the bartender.

A’s friend stumbles.

A grabs B by the shoulder and pushes him back.

B glares at A, demanding to know why he’s in the way.

A insists B apologize.

B refuses, insults the state of the local militia.

A’s friend tries to break in, stating they’re fine. They think everyone should calm down.

A takes a breath, relaxes.

B spits in A’s face.

A grabs their glass mug off the bar, clocks B across the face.

B stumbles backwards.

Pause.

Let me break this down:

A hitting B with the glass is actually the moment where the scene ends, the tension releases, even though the action continues into a new scene with B’s reaction. We’ve got our setup, our dilemma, our decision, and then action. On the action, the tension releases, and you start all over again.

An example is the scene from The Princess Bride where Wesley is climbing cliff and Inigo offers to throw him the rope. This sequence is a separate scene from the following duel, but works as establishment for the characters and the kind of men they are. The scene climaxes when Wesley tells Inigo to throw him the rope and enters it’s denouement as he finishes making his way to the top.

This sequence is crucial to the duel. We begin to really care about Inigo, feel a sense of camaraderie. This camaraderie is now in conflict with our desire to see Wesley save Buttercup and, as a result, we worry over Inigo’s future. He’s no longer just a mook, but a compelling character in his own right.

If you wanted the true underlying tension of The Princess Bride’s duel, it’s this conflict and not the duelist’s skill level.

The equal skill provides additional tension against the goal of saving Buttercup, but, due to Princess Bride’s fairy tale structure, we know Wesley is going to win. What keeps the duel itself interesting is, how will Wesley win and will he defeat Inigo before Buttercup is killed by Vizini?

The same question is asked in the following duel with Fezzik with a similar structure. Then, we see the same structure play out again with Vizzini. Wesley matches their skills against his in a fair fight, and, ultimately, defeats them.

There are, however, multiple fight scenes within Wesley and Inigo duel. You can see those breaks when they stop fighting, to give the audience a breather and breaking the fight up to ensure the scene doesn’t become monotonous. With action sequences, monotony is, ironically, a real danger. Putting in breaks allows you to extend the action without losing audience attention, and let’s their brain rest.

These breaks are just as important in writing as they are in film. You want to make sure you keep ratcheting up and releasing that tension, along with audience expectation.

(If you’d like an interesting breakdown of how historical fencing compares to The Princess Bride, Skallagrim’s got a good one. The Princess Bride itself is a love letter to the likes of Zorro and swashbuckling films from the Golden Age of Hollywood, digging into it’s influences can help you if that’s a genre you want to chase.)

You should start thinking of every fight sequence in your novel as not one scene, but many little scenes broken up around character action and dialogue. Build up, up, up, then release, and start over.

Setup: This is the moment before your characters engage, where you establish the stakes and potential consequences. The surrounding pieces at play, A is drinking with their friends, B is a mercenary, A’s friend is in the militia, and there might be some bad blood between them.

You start establishing your tension here, your pieces stressed against each other before we start ratcheting up.

Rising Action: This is where the tension really starts to build. Depending on the type of scene you’re structuring, your character’s violent actions could actually fit in here. Most likely, initially, prolonged violence will be part of the second scene.

Climax: Your tension dissipates on the opening strike. Then, the characters must decide if they’ll escalate. Any violence in the following scene can end here.

The climax of the example is A hitting B.

Denouement: I like to call this “The Decision”, the fallout, the realization, where characters decide if they’re going to back out. This can be the retreat, where they try to get away before being forced back into a fight, the dialogue where characters try to buy themselves time, realizations of injuries, or just their breather between bouts.

The denouement of the scene is B stumbling.

Escalate: The violence in the next section escalates, which means the situation becomes more serious, more intense, more violent. Basically, things get worse.

The escalation of the scene? If A continues to attack B, or if B’s mercenary friends join the fray.

The consequences of violent actions are, usually, events escalate into more violence.

Remember, violence is about problem solving. It’s a tool in the box of conflict resolution, one which often acts as a short term solution but ultimately makes the situation worse in the long run. If your character has chosen to resolve a conflict this way then they have limited their options to resolve the conflict differently. This is true whether you’re looking at widespread warfare or an interpersonal dispute. Violence closes off alternative routes for resolution, and builds expectations for audience over what will happen next.

When you build your world, your characters, and your narrative, you are making promises to your reader. A large part of the tension which comes from violent actions by your characters, or fight scenes, will be consequences resulting from them. If you promise, say, that violent actions by your MC will result in swift, harsh consequences which could cost them their life, then you better deliver. The character doesn’t need to die, but something should happen. Showing up to work the next day like nothing went down, especially if someone else in a position of authority saw it? Now, you’ve not only undercut your narrative tension but devalued your world and broken the reader’s trust. You promised consequences. You didn’t deliver. At that point, there’s no reason to take any other threat presented to your characters seriously.

Suspension of Disbelief is not built on realism, it’s built on your compact with the reader, the rules you’ve set for your narrative and their expectations, the narrative you’ve promised to deliver. You need rules because they create a framework for your story, for your scenes, and, especially, for you fight scenes.

Your fight scenes are only a part of your story, but they’re important. They provide an opportunity to expand your character and also create disruptive inciting incidents around which action occurs.

If people complain your characters aren’t realistic, you shouldn’t immediately jump to make events and characters more like the “real” world. Rather, you should step back, look at your worldbuilding and the expectations you set in the early pages. Did you do the prep work?

You can’t win ’em all, but, often, the criticism you’ll get won’t be helpful until you realize what it means. Everything is permissible, so long as you put in the work to set it up first.

A bar brawl at the beginning of your novel could be the foundation of the entire story with all the spiraling consequences falling like dominoes from that one action. And that, my friend? That is tension.

Tension is uncertainty. It’s in the question, what will happen next? What will happen to these characters I care about? Will they be okay?

Turning heel, Leah raced toward the window at the cavern’s opposing end.

Soldiers struggled to stand, clamoring off the benches. Some of the beta-kings drew their lasabres and laspikes, while the pteroriders yanked out pistols and force-blades.

Leah dodged past a soldier reaching for her, jumped onto the table, and flung herself forward with a telekinetic thrust. She landed hard, half-way free, lasabre springing to life in her hand. An orange flash sliced through a long wooden table hurled at her head. The pieces fractured cleanly and broke apart into two flat planes. Thrusting them behind her, she didn’t wait for the crash but heard the screams.

Overhead, footmen moved to the edges of the balconies, rifles ringing the room. They took aim as a unit, and fired into the crowd.

Dancing between the bolts, Leah dove through fleeing petitioners. Three strong presences flashed through her.

A knight in silver lunged into view, a turquoise blade ignited in his hand. His armor shone, his identity hidden by his mask.

Another, familiar, presence closed in from behind.

Nathan, Leah thought. Cor!

They were going to cut her off, pile on like raptors in the diplohouse.

Leah’s jaw tightened. She needed to get out. That meant reaching the cavern’s overlook. Her eyes moved to the left-side balcony. There!

Orlya thrummed with approval.

Leah spun, diving into the crowd.

Two knights gave chase.

A third followed, but at an easy pace. Petitioners screaming as his telekinesis seized and hurled them from his path.

Switching off her sword, Leah catapulted high into the air, over the soldiers at the balcony railing, and landed hard. Shoulder and back aching, she rolled to her feet.

Several men stared at her.

Leah smiled.

A soldier lifted his rifle.

With raised hands, she stepped backwards.

Roaring, Hector Darenian dropped in from above — a raging ball of sapphire blue. He crashed into the gathered soldiers, plowing through them, blade shearing through their bodies. Hot blood cascading across the stone, Hector slammed headlong through the opposing wall.

Leaping over the fallen, Leah landed neatly on the balcony’s railing and stepped off. She hit the cavern floor. Another quick dash carried her to the overlook.

“Stop!”

We can sit here and talk about tension, but tension is all about the pieces you pressure against each other. External factors pressure internal goals and desires, external consequences cut off alternate paths. You can switch up with more techniques, add new odds like more enemies or more dangerous enemies, change the rules like switching from the left hand to the right, pull out new pieces of information, but there also needs to be the promise the event is going to lead somewhere, that it will affect something, that this furthers our story.

Some writers, especially new writers, have a habit of writing their story like it’s modular. The scenes are individual rather than interlinked. The hot boy gets into a bar fight to show how cool and dangerous he is, but that’s the only narrative purpose the scene has. However, you can add tension to this scene and the MC’s relationship with said boy if the police show up at their house a day later to ask questions about the brawl. Now, interacting with him could have real consequences for their own goals, their future, how good an idea is this? And, suddenly, we’ve got stakes.

If your violence serves no purpose, it has no purpose. In the world of fiction, your fight scene is what you make it. You can’t expect real world expectations or fears or the concept of violence itself to do the work for you. You’ve got to latch the actions into both your characters and your world.

How does a bar brawl between two factions affect the relationship of the town militia and the mercenaries camped outside? How does a bar brawl affect A and B’s relationship with the other locals in the bar? With the bartender? With their friends? How do the injuries sustained change the severity of what happens? What if someone dies?

Your inciting incidents are what you make of them. Your fight scene can be a workhorse building up your narrative, or it can be meaningless fluff with stick figures clashing together on the page.

-Michi

This blog is supported through Patreon. If you enjoy our content, please consider becoming a Patron. Every contribution helps keep us online, and writing. If you already are a Patron, thank you.

Building Narrative Tension: How to Keep Your Fight Scenes Interesting was originally published on How to Fight Write.

944 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's something I don't see writers practicing enough: how big things can permanently change your character.

I see people putting their characters through war, abusive relationships, health disorders, and intense grief. Since popular writers often fail here, I hope you guys are also considering how these things will affect your character in the long run. I don't mean "Oh, they have bad dreams now and are jerks to everyone, but only for a little while." I mean has their entire outlook on life changed dramatically, and if so how? Does it show? Do they try to hide it and move on, or do they accept that this is who they are now? Does it take them a long time or a short time to realize things can never again be the way they were? How does that affect them? Do they choose to keep this new personality, or do they try to change it?

Not everyone wants to acknowledge this type of development in a character because it gets in the way of their plans or disrupts plot. Also, some characters are made of stern stuff or are just flexible enough to survive with their personality intact. Yet, major events in a story should leave a noticeable impact on a character, the more personal the event generally the bigger the personality change.

Just think about it if you haven't already, y'know?

19K notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m wondering, how do I come up with good ideas to write a sub-plot that actually fits into the story and won’t make the reader lose the connection with the main plot?

How to Write A Sub Plot

If you look back on every single bestselling book ever printed, the chances are that most, if not all of them, contain sub-plots.

A sub-plot is part of a book that develops separately from the main story, and it can serve as a tool that extends the word count and adds interest and depth into the narrative.

Sub-plots are key to making your novel a success, and, although they aren’t necessary for shorter works, are an essential aspect of story writing in general.

However, sub-plots can be difficult to weave into the main plot, so here are a few tips on how to incorporate sub-plots into your writing.

1. Know Your Kinds of Sub-Plots and Figure Out Which is Best For Your Story

Sub-plots are more common than you think, and not all of them extend for many chapters at a time.

A sub-plot doesn’t have to be one of the side characters completely venturing off from the main group to struggle with their own demons or a side quest that takes up a quarter of the book. Small things can make a big difference, and there are many of these small things that exist in literature that we completely skip over when it comes to searching for sub-plots.

Character Arcs

Character arcs are the most common sub-plot.

They show a change in a dynamic character’s physical, mental, emotional, social, or spiritual outlook, and this evolution is a subtle thing that should definitely be incorporated so that the readers can watch their favorite characters grow and develop as people.

For example, let’s say that this guy named Bob doesn’t like his partner Jerry, but the two of them had to team up to defeat the big bad.

While the main plot involves the two of them brainstorming and executing their plans to take the big bad down, the sub-plot could involve the two getting to know each other and becoming friends, perhaps even something more than that.

This brings me to the second most common sub-plot:

Romance

Romance can bolster the reader’s interest; not only do they want to know if the hero beats the big bad guy, they also want to know if she ends up with her love interest in the end or if the warfare and strife will keep them apart.

How to Write Falling in Love

How to Write a Healthy Relationship

How to Write a Romance

Like character arcs, romance occurs simultaneously with the main plot and sometimes even influences it.

Side-Quests

There are two types of side-quest sub-plots, the hurtles and the detours.

Hurdle Sub-Plots

Hurdle sub-plots are usually complex and can take a few chapters to resolve. Their main purpose is to put a barrier, or hurdle, between the hero and the resolution of the main plot. They boost word count, so be careful when using hurdle sub-plots in excess.

Think of it like a video game.

You have to get into the tower of a fortress to defeat the boss monster.

However, there’s no direct way to get there; the main door is locked and needs to have three power sources to open it, so you have to travel through a monster-infested maze and complete all of these puzzles to get each power source and unlock the main door.

Only, when you open the main door, you realize that the bridge is up and you have to find a way to lower it down and so forth.

Detour Sub-Plot

Detour sub-plots are a complete break away from the main plot. They involve characters steering away from their main goal to do something else, and they, too, boost word count, so be careful not too use these too much.

Taking the video game example again.

You have to get to that previously mentioned fortress and are on your way when you realize there is an old woman who has lost her cattle and doesn’t know what to do.

Deciding the fortress can wait, you spend harrowing hours rounding up all of the cows and steering them back into their pen for the woman.

Overjoyed, the woman reveals herself to be a witch and gives you a magical potion that will help you win the fight against the big bad later.

**ONLY USE DETOUR SUB-PLOTS IF THE OUTCOME HELPS AID THE PROTAGONISTS IN THE MAIN PLOT**

If they’d just herded all of the cows for no reason and nothing in return, sure it would be nice of them but it would be a complete waste of their and the readers’ time!

2. Make Sure Not to Introduce or Resolve Your Sub-Plots Too Abruptly

This goes for all sub-plots. Just like main plots, they can’t be introduced and resolved with a snap of your fingers; they’re a tool that can easily be misused if placed into inexperienced hands.

Each sub-plot needs their own arc and should be outlined just like how you outlined your main plot.

How to Outline Your Plot

You could use my methods suggested in the linked post, or you could use the classic witch’s hat model if you feel that’s easier for something that’s less important than your main storyline.

3. Don’t Push It

If you don’t think your story needs a sub-plot, don’t add a sub-plot! Unneeded sub-plots can clutter up your narrative and make it unnecessarily winding and long.

You don’t have to take what I’m saying to heart ever!

It’s your story, you write it how you think it should be written, and no one can tell you otherwise!

Hope this Helped!

12K notes

·

View notes

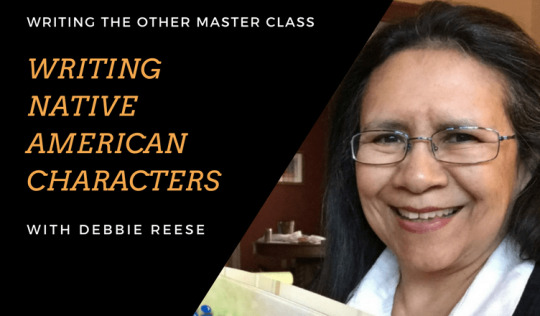

Photo

Writing Native American Characters: How Not To Do A Rowling | On Demand Master Class

J. K. Rowling drew negative attention from Native people for what she did in her work Magic in North America. The mistakes she made were common–very common–and also easily avoidable. In this seminar, Native scholar and activist Debbie Reese talks about the missteps Rowling and many other authors have made, why they are a problem, and offers writers strategies for avoiding them and doing better.

Topics Include:

Native Nationhood and Sovereignty

History

Representation and Impact

Cultural Appropriation

Language and Naming

Spiritual Traditions

Stereotypes and Tropes to Avoid

Researching Native Americans for Fiction

Worldbuilding for Speculative Fiction

Price: $50

Download now

The class includes both the video recording of the live seminar plus supplemental resources and reading recommendations. All class materials are online, and a download link will be emailed to you after you complete your purchase.

youtube

Accessibility: The class video is closed captioned and a transcript of the video is available to everyone who purchases the seminar.

[SuperheroesInColor faceb / instag / twitter / tumblr / pinterest / support ]

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

That's Not How This Works

As a general rule, I don’t like to do this. We do get follow ups sometimes, and if it’s something I’d just tear into, normally, I’d let it slide.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I do enjoy tearing a part a poor argument; less so when it was offered with innocent intent.

Hi. Regarding the anon who asked about daggers vs sword. I have some thoughts on the matter that might help. Daggers can go up against bigger weapons. The key is to understand the pros and cons of each weapon and the strengths and weaknesses of each wielder and use that to level the playing field. Plus no one said you have to fight fair. The sword has reach, but any opponent will have trouble fending off attacks from two directions… (part 1)

(Part 2) … With swords it’s about momentum and power, with daggers it’s speed. So, the swordsman will need better footing and more space. If the dagger wielder is smart, he/she can create a reasonable chance of winning. If your opponent is stronger, you have to be smarter and faster. If your opponents outnumber you, seperate them or increase your number. Everyone has weaknesses, exploit those while maximising your strenghts. It will still be a stiff fight but it gives you better odds at least

There are so many things wrong here. So, give me a second, and I will recount the ways:

Hi. Regarding the anon who asked about daggers vs sword. I have some thoughts on the matter that might help.

You are correct, you have “some thoughts.”

Daggers can go up against bigger weapons. The key is to understand the pros and cons of each weapon…

If you just stop here, it’s fine.

…and the strengths and weaknesses of each wielder and use that to level the playing field.

And there we go.

No.

The entire purpose to a knife is that you do not want a level playing field. In combat, you never want a level playing field. When you are fighting to kill someone, and someone else is fighting to kill you, you do not want them to succeed. The safest way to ensure you win is by seeing that your opponent doesn’t even have a chance to fight.

A level playing field is just an invitation to getting yourself killed. For, somewhat obvious reasons, you do not want this.

Incidentally, yes, understanding the strengths and weaknesses of your opponent a very important thing. You want to engineer a situation where you’re at your strongest, and they’re at their weakest.

Plus no one said you have to fight fair.

We, literally, have a tag called, “the only unfair fight,” referencing the longer phrase, “the only unfair fight is the one you lose.”

More than that, Michi specifically referenced the use of the dagger as an ambush weapon. Those are also, ironically, some of the first words out of her mouth whenever we get a question on daggers.

The sword has reach, but any opponent will have trouble fending off attacks from two directions…

I realize this may sound novel, but you can’t flank someone by dual wielding. Your arms aren’t that long. You are attacking someone from one direction. If you want to attack them from two directions simultaneously, you need an accomplice. Amusingly, that’s a time when a dagger will shine. Your friend, with their sword, ties up the fighter while you slip in and shank them a couple dozen times in the kidney.

Ironically, again, this is what the parrying dagger in conjunction with the sword is for. You lock up the opponent’s blade and then stab them. The difference here is you don’t have a long blade to reach your opponent. Even if the dagger could lock the sword up (see the original post for why it can’t), they’re still left with the original problem of getting close enough to their target to hit them.

Blocking with swords isn’t the same as it is with hand to hand martial arts or blunt weapons, because your goal is to maintain the blade’s edge. Swords don’t clang together, they slide around each other in an under/up or over/under fashion. Your goal is to use your blade to get your opponent’s blade off vector to miss you while creating opportunity for counter attack. You angle your blade so the opponent’s slides off the sharpened edge. However, with deflections you aren’t actually stopping the blade’s force which means if you don’t redirect it far enough then it can still connect and you run the risk of moving directly into it on your counter attack.

Daggers needs to be able to redirect their opponent’s blade long enough that they can move three feet forward past the kill zone to strike their opponent with one or both of their daggers. You’re talking a three to five seconds difference to the fraction of seconds it takes for the swordsman to adjust their grip and counter attack off the redirection. That’s if the sword didn’t hit another vital place, like Daggers adjusted the sword off center and the blade still pierced their ribs or their thigh.

This is the point you’re missing, they don’t have to retract the blade (they can, and cut Daggers up the side), a small change in grip and stance is all they need to change a thrust to a hewing strike. It came forward, went down, and now it’s switched to an upward diagonal that’s caught Daggers in their side as they’ve moved forward. That hew has cut between their ribs and punctured their left lung. The fight is now over, and Daggers will most likely die. That’s if the swordsman stops with the hew, instead of hewing up, drawing back (cutting more tissue on his way out), and thrusting again with the blade point in single action to pierce another body part like the central chest or the heart.

Again, they never have to move their feet forward or back to do this. All it takes is a slight adjustment in grip, arms, and foot position. A swordsman can thrust from a stable position without stepping forward if the opponent comes within range, they only need to move their feet if the opponent is outside the blade’s reach.

Reach translates to: how far do I need to move from my centralized stance to strike my opponent. This is the true power of weapon length. Two blades of equal length will translate to a single step forward for both parties from starting position. Daggers will require two to three because they are hand to hand range weapons, while the sword requires one or none depending on whether they are the aggressor or defender.

While hand to hand combat will always naturally move inward, swordsmen and most individuals who use weapons are trained to maintain distance between their opponent which is advantageous to them. They will move no closer than necessary in order to maintain their weapon’s effective range. While knights did practice grappling techniques with swords, if you don’t also possess one, the swordsman will never come close enough to you in a way you can utilize.

With swords it’s about momentum and power…

No, that’s an axe. A sword is a shockingly agile weapon.

…with daggers it’s speed.

Partial credit here, but it’s incomplete. The other major strengths of the dagger are how easy it is to conceal, and how small it is. The amazing thing about a dagger isn’t how fast it is, it’s that you can easily pull one in close quarters and shank them with a weapon they didn’t see coming.

Speed only means, once you’re there you can poke a lot of times in quick succession. The irony is that an individual knife wound isn’t likely to be that dangerous. It’s all the immediately following successive strikes that seal the deal.

Somewhat obviously, if you can’t get close enough to stab someone, you also can’t get close enough to stab them a couple dozen times.

The swordsman will need better footing and more space.

The footing part is backwards, in the original scenario, the dagger user would need vastly better footing. A sword user does need more strength, it’s true, but the sword remains an effective deterrent against getting to close even in extremely cramped environments. This is less true of some specific weapons, like the katana, and even more true of some other blades, like the epee, rapier, or estoc, which can be used in a tight hallway.

On footing, to borrow an old quote, “I do not think that word means what you think it does.” Footing is your ability to remain standing. If you think a sword has so much momentum that it will try to drag off balance, no. Just, no.

When you’re reading or watching a training sequence, and the instructor is telling the student they’re off-balance, or over-extending themselves, that’s a fault of the student, not the weapon. It’s a natural thing, a student will try to press their attack using their upper body and not simply advance. It’s simple, it’s a mistake, and it’s one that can be easily corrected.