#苏轼

Text

“How Often Does Such a Bright Moon Come Around?” (水調歌頭 · 明月幾時有) Translation

(Another year, another Mid-Autumn Festival, another poem translation. This particular poem is very famous because of the first and last lines, which are frequently referenced in popular culture. Happy Mid-Autumn Festival!)

How often does such a bright moon come around?

By Su Shi (Song dynasty, 1076 AD)

Mid-Autumn of the year Bingchen (2), drank all night in celebration, became heavily inebriated. Composed this poem to commemorate this occasion, and in dedication to Ziyou (3). (4)

How often does such a bright moon come around? With wine in hand, I ask the heavens.

Wondering what year it is for this day in heaven (5), in the palace high above.

Wishing to ascend on the wind, yet I cannot stand the chilly air around those lofty towers of jade.

Dancing and amused at my own crisp shadow, the frigid heavens surely cannot compare to the mortal realm below.

Rounding the vermilion building, hanging low near the intricate windows, the moon casts light over the sleepless (6).

The moon should not feel bitter jealousy, so why is it only full on parting?

Humans feel grief and joy, partings and reunions, just as the moon waxes and wanes.

For both of these heartening things (7) to happen together is very rare indeed.

May we be blessed with longevity, so that even when thousands of li (8) apart, we can still gaze upon this wonderful moon together.

—————————-

Notes:

This poem is in the Ci/词 format, and follows the rhyme scheme (Cipai/词牌) called Shuidiaogetou/水調歌頭/水调歌头.

Bingchen/丙辰 is a year in the Chinese Sexagenary Cycle, which is known in Chinese as Tiangandizhi/天干地支 ("Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches") or simply Ganzhi/干支 ("Stems and Branches"), and is used to record time. This system has been in use since at least the Shang dynasty around 3000 years ago (oracle bone artifact bearing inscriptions of ganzhi has been found at Yinxu/殷墟, the archaeological site of the ancient capital of Shang dynasty; however, during Shang dynasty the Ganzhi system was used to track days and not years, unlike how it has been used in later times). Because there are 60 years in one cycle, it is possible to trace back to specific years. In this case, Bingchen would be exactly 1076 AD.

Ziyou/子由 is the courtesy name of Su Shi's brother, Su Zhe/蘇轍.

This section is a short introduction to the poem, which begins after this section.

This may be a reference to the concept that "a day in heaven is a year on earth" ("天上一天,地上一年"; famously included in Journey to the West), which in turn is a reference to the ecliptic plane (called Huangdao/黄道 in Chinese), since for an observer on Earth, the Sun appears to move in an elliptical path throughout the year. This means that it takes a year (i.e. "a year on earth") for the Sun to "complete" one round in this elliptical path (i.e. "a day in heaven").

Here, "the sleepless" is a reference to the poet himself.

"Both of these heartening things" refers to reunion with family and/or friend, and the occurence of a full moon.

Li/里 is a traditional unit of distance. During Su Shi's time (Northern Song dynasty, 960 AD - 1279 AD), 1 Li ≈ 576 meters = 0.576 km or 0.36 miles (Note: link leads to pdf).

—————————-

Original Text (Traditional Chinese):

《 水調歌頭 (1) · 明月幾時有 》

[宋] 蘇軾

丙辰中秋,歡飲達旦,大醉,作此篇,兼懷子由。

明月幾時有?把酒問青天。不知天上宮闕,今夕是何年。

我欲乘風歸去,惟恐瓊樓玉宇,高處不勝寒。起舞弄清影,何似在人間。

轉朱閣,低綺戶,照無眠。不應有恨,何事長向別時圓?

人有悲歡離合,月有陰晴圓缺,此事古難全。但願人長久,千里共嬋娟。

#mid autumn festival#midautumnfestival#chinese poem#poetry#how often does such a bright moon come around#my translation#明月几时有#苏轼

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

《春宵》- 苏轼

A translation with pinyin of Su Shi's 春宵 Spring Night poem.

chūn xiāo – sū shì (宋 – sòng)

春宵一刻值千金,

华有清香月有阴。

歌管楼台声细细,

秋千院落夜沉沉。

PINYIN: Chūn xiāo yí kè zhí qiān jīn,

Huá yǒu qīng xiāng yuè yǒu yīn.

Gē guǎn lóu tái shēng xìxì,

Qiū qiān yuàn luò yè chén chén.

ENG: In a spring night, a short time is worth gold and riches,

Flowers emit a sweet fragrance as the moon clouds over.

In the high buildings, the sounds of music are soft,

And the courtyard with the…

View On WordPress

#chinese poem#chinese poetry#苏轼#诗词#诗歌#learn chinese poetry#night poetry#poems about spring#poetry#song dynasty#spring night#spring poetry#su shi#su shi poems#宋#宋诗#宋朝#宋代

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

su shi sushi

nom nom

#wangchuan fenghua lu#glorious records of wangchuan#elysium of legends#忘川风华录#忘川風華錄#<-traditional for lanca!#su shi#苏轼#蘇軾#su dongpo#苏东坡#蘇東坡#my art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

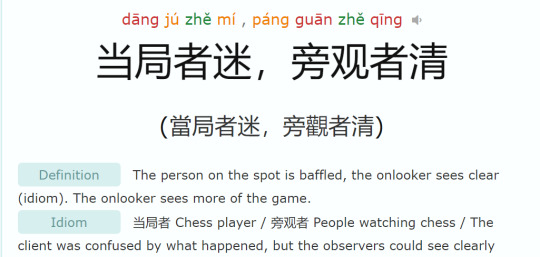

题西林壁 - Written On this Wall in Xilin

by 苏轼 (Su Shi, 1037 - 1101)

横看成岭侧成峰

héng kàn chéng lǐng cè chéng fēng

Across, look - it’s a mountain range, sideways, a towering summit;

远近高低各不同

yuǎnjìn gāodī gè bù tóng

from far to near, from high to low, every angle a world of its own.

不识庐山真面目

bù shí lúshān zhēn miànmù

One does not perceive the true face of Mt. Lu,

只缘身在此山中

zhǐ yuán shēn zài cǐ shān zhōng

only because they still stand amidst its valleys and peaks.

(Source)

This is a copy. Carved on a wall at the Xilin Temple of Mt. Lu and then moved to the Donglin Temple some time later, the original has been lost to time.

.........................................................................................................

Another homework poem! I should start tagging them xD

Did a quick translation with zero context while stuck in the washroom. It was very amusing! As was wolf whistling Mt Lulu with friends ~

Anyway, I also got the vibe that there was a story here somewhere and thought it would be fun to investigate as much as I am able to! When I’m done with these notes, I shall try for another translation which will be the face for this post xD But I’ll also keep the fun tl in at the end.

Notes

TRANSLATION

This is a very straightforward seven character quatrain with a rhymed second and fourth line. It was written in the Song Dynasty by the poet better known as Su Dongpo - yes I was surprised as well, such a famous line and from a Song Dynasty poem? They aren’t just known for their lyrics! I wonder which other everyday idiom has similar origins...

So the lines in this poem themselves don’t actually need clarification.

A visitor to the 庐山 Lu Mountain has covered quite a lot of ground, looking at it from end to end and seeing it as a mountain range. Then staring at it from one end, it looks like just one towering mountain. From when he approached he saw the range and the summit; when he was close, when he climbed up and then all along his descent, every vantage point rewarded him with a different, gorgeous view and field of vision. Puzzled though, he sat and wondered which is ‘real’? And then he realized, all of them and none of them at once. Because... I am still in the mountain.

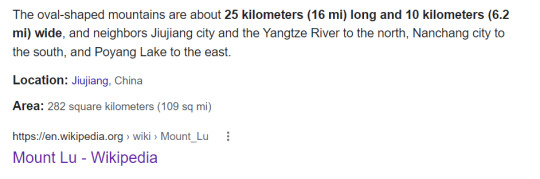

For anyone who is wondering Mt. Lu... where is this again?

Recognize this picture? (You might if you watch cdrama) Yup! This is one of the scenic sights within Mt Lu xD

(Source)

I felt a little let down after reading the poem initially.

不识庐山真面目 // one does not perceive the true face of Mt. Lu

Like oh, so you mean this?

So easy?

But the truth is HAH! The person who most needs a better view often doesn’t know how much they need it. (Me, I’m talking about ME)

In the process of looking up details of the ‘background section’, and how to better illustrate it, I came across many photos of Mt. Lu.

This is 望江亭 // Riverwatch Pavilion

This is the same 望江亭 // Riverwatch Pavilion

Stone carvings by 黄龙潭 // Yellow River Springs

This is 如琴湖 // Ruqin Lake

Again 如琴湖 // Ruqin Lake, different season, different POV.

Some branches... mmmm...

My favourite pavilion is the 观云亭 // Cloudwatch Pavilion

Less ethereal but still enticing! 观云亭 // Cloudwatch Pavilion!

(Source)

Truly magical! 观云亭 // Cloudwatch Pavilion again.

Do you want another angle of 观云亭 // Cloudwatch Pavilion?

(Source)

Maybe enough with the pavilions.

There’s tea!

Jiangxi Mt. Lu Green Tea Field

Snow at 含鄱口 // Hanpokou

Another location? No! 含鄱口 // Hanpokou again :)

Random bridge!

状元桥 // Top Scholar’s Bridge... I wonder who visits? xD

A Mt Lu sunset at 含鄱亭 // Hanpo Pavilion

At some point, I was like wait a minute, just how big is this mountain?

(As below)

Google map

(Source)

Ah.

I don’t know how Mt Lu looks like. Every view is different - suddenly, that sentence made a world of sense. No matter where I am, it’s going to be different. Like if I look at a pavilion from below and compare that with how it looks from a nearby peak, or when standing right in front of it. And that’s just one spot!

Yes dear. And you are confused because you’re right smack in the middle of it all, trying to describe 25km x 10km of mountain with what you see in in two 24mm eyes. That’s impossible to achieve.

Maybe take a step back and reframe your question?

HISTORY

Relegation was a very common method of punishment for officials who had been convicted of crimes. This was a distinct punishment from exile, in which the criminal is sent to distant backwaters, often with harsh conditions. Officials sentenced to relegations did not lose their positions as officials, they were demoted and posted to locations distant from the central government and court. Besides a demotion, how far away they were sent was an indication of the severity of the crime. They could not resign and just live as commoners, instead, they may be given a title with no actual power and be thus forced to serve out their sentence there. [x]

The period of relegation that got Su Shi, of Song Dynasty, his name of Su Dongpo began in the year 1080, when he was convicted of insulting the Emperor for a poem he wrote criticizing political reforms. With a nominal official’s title that did not confer any power on him except to tie him down to the area, off he was sent to Huangzhou!

(Notes for basis of passing through Guangzhou, Kuang in wade giles)

(Source)

The poem he wrote which very cleverly drags this situation made me smile. He was 45 at this time, and the faction that played a key role in his banishment was new. Do not doubt how big of a blow this relegation was. Hope for a pardon was so dim as to be almost nonexistent. And yet, he sees the humor in the situation and makes fun of it! (But also, my bro, I guess you never learnt to shut it, did you?)

His family came to him in the first year and they stayed together, living frugally. With the help of a poor scholar friend by the name of Ma Zhengqing, in the second year, he got a little plot of land, which was on an old army camp East of the city. We know this because he wrote some poems about his experiences on this Eastern Slope 东坡 (Dong Po) from which he got his nickname.

We remember Ma Zhengqing because of Su Dongpo. But maybe without Ma Zhengqing, there would not have been a Su Dongpo. Interesting how these things happen, isn’t it?

Fun fact: It was during this period that he wrote his Chibi poems!

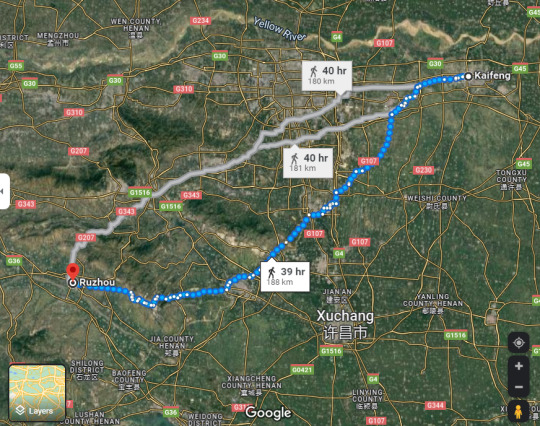

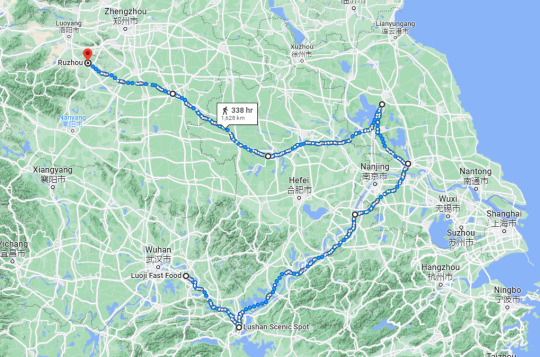

In the fourth month of 1084, Su Shi was recalled from Huangzhou. With a new emperor and new government, he was still under the relegation sentence, but his new location became Ruzhou.

Which… please see for yourself below. I mapped it out on google maps based on present day locations, though I also eyeballed the distance on other Chinese maps of the Song Dynasty to confirm. This is just needed to show the walking distance for impact.

NOW I’m quite tired from scrolling through google maps*flops on the floor*.

Here’s the entirely water based route he could have taken… just following the blue lines (waterways) on google maps and joining them together. However, this does not account for the direction of the river’s flow, nor for any construction or whatnot that has happened over nearly a thousand years.

(Good gods, this trip looks exhausting. How long did he take to complete it? A year???)

Here’s the link to the map I made with latitude and longitudes indicated with a * below. If for whatever reason, you also want to stalk blue lines across google maps, you’re welcome to reference the full list. And if you know anything about the actual route, please contact me! I really want to know.

https://goo.gl/maps/uFKGrxTFZPqToFBX7

Huangzhou - 30.433872962245427, 114.88129769733013*

Yangtze River - 30.377781819827735, 115.07101171640872

Lushan Maintain - 29.512493686853997, 115.97992335630641*

Jiujiang - 29.655519332862937, 115.95199503510239

Yangtze River - 31.52268831477707, 118.3835515008836*

joins - 32.25937931638017, 119.4709085685721

Jinghang Yunhe - 32.42372696795087, 119.48513109148513*

Jinghang Yunhe - 33.56999997351908, 118.97126706569289

Huaishu River - 33.45610953325041, 118.94490546438135*

Huaihe River - 32.54604115026407, 116.58836355764417*

joins - 32.500902310509126, 116.52398860951106

Yinghe River - 33.63248728287315, 114.61038506349661*

Shahe River - 33.69194084968913, 113.60587536388371

Ruhe River - 34.146226764936046, 112.8221271332927

Ruzhou - 34.16581654981741, 112.84447346106711*

Anyway, so this has all been to give a bit of background on how Su Shi found himself passing by Mt. Lu. From Huangzhou, he followed the Yangtze to Jiujiang, and from there he had the opportunity to visit Mt. Lu and went for it.

After the visit concluded, he enjoyed it so much that he eventually recorded it in 《东坡志林》 which can be read as Dongpo’s Forest of Records or Dongpo’s Records of Forests, both of which are very cute names for a travelogue.

The account can be found in Chapter 1 of the notes, under the name: 《记游·记游庐山》 , and the tone of it is so so charming!

(Source)

When he first got there, the scenery was fantastically beautiful. It was nothing like anything he had ever seen before, and overwhelmed by the beauty he had thought he would very likely not have the time for poetry. So he proceeded to declare he had no intention of writing any poetry.

(Like how we all say, no need to take photos, no photo can record the beauty that eyes can see xD but in much the same way, we all know what happens to that right?)

But afterwards, he met some monks who lived in the mountain who all exclaimed in excitement or surprise.

“Su Zizhan* has come!”

*子瞻, Su Shi’s courtesy name

And ‘involuntarily’, he composed a quatrain which he provided in his notes.

芒鞵青竹杖 | With rush shoes and green bamboo staff,

自挂百钱游 | upon it, a hundred coins hung, off I roam!

可怪深山里 | How very odd, deep in the mountains here

人人识故侯 | everyone recognizes some old official.

(Su Shi, probably: I’m popular! Hehe.)

And immediately, he smiled at the absurdity of his verse and wrote two more xD

(yjtc: bro, what happened to no poems today?)

青山若无素 | Green mountain, whom I have not met before,

偃蹇不相亲 | like a haughty stranger, not approachable at all.

要识庐山面 | Want to know Mt. Lu's face?

他年是故人 | Then become acquainted in the years to come.

自昔忆清赏 | From before, I recall admiring its grace in works,

神游杳蔼间 | in spirit, exploring amidst the moss and vine.

如今不是梦 | Now this is no dream,

真个是庐山 | it really is Mt Lu.

The next day, he was reading the book his friend Chen Lingju had handed to him, 《庐山记》 ~ Notes on Mt Lu as he walked. He saw poems from 李白 Li Bai and 徐凝 Xu Ning, and something about them amused him very much and he laughed. Later, his steps took him into Kaixian Temple where the monks requested a poem. For them, he wrote the following:

帝遣银河一派垂 | The Heavenly Emperor sends the Silver River [1] gushing down;

古来惟有谪仙辞 | in all of time, only one Immortal's [2] verse can be called thus.

飞流溅沫知多少 | The flying waters splash and foam, who knows how much?

不与徐凝洗恶诗 | It will not wash Xu Ning's terrible poem [3].

[1] Milky Way / Alludes to Li Bai's poem about Mt Lu's waterfall 《望庐山瀑布》,

[2] 谪仙 is an deity sent to the mortal realm. Li Bai was known as the 诗仙 / poetry immortal

[3] Xu Ning’s Mt. Lu waterfall poem《庐山瀑布》

He took about ten days or a little more to explore the Southern side of the mountain. Then concluded that there were too many gorgeous places to list and discuss, but of these, 漱玉亭 (Jade Pavilion) and 三峡桥 (Three Gorges Bridge) were the best to him. And thus he wrote two more poems about them, which you may read translated here.

漱玉亭 // Jade Wash Pavilion

(Source)

(Source)

三峡桥 // Three Gorges Bridge

(Source)

And here we have a Ming Dynasty illustration of the same place.

(Source)

Finally, finally, he paired up with a friend he calls Old Zong (this bears a little more research), to explore the West Forest together. During this time, he wrote his final Mt Lu poem, which is also his most well known one.

横看成岭侧成峰 | Across, look - it’s a mountain range, sideways, a towering summit,

远近高低各不同 | from far to near, from high to low, every angle a world of its own.

不识庐山真面目 | One does not perceive the true face of Mt. Lu.

只缘身在此山中 | because they still stand amidst its valleys and peaks.

And I feel like, having had this experience of trekking through the mountain, all the interesting encounters, reading about other people's thoughts, he also took the time to reflect on his own feelings and reactions. Maybe this philosophical view of the world was something he already was nursing, and this metaphor with Mt. Lu was a good way to express it. Maybe he didn't have the voice, and the little holiday inspired him?

Who knows!

But having had the tinest of peeks into some of the events that happened leading to and also on this trip, knowing that this was the closing of a paragraph in his life, no wonder it got famous!

.......................... —ฅ/ᐠ. ̫ .ᐟ\ฅ —..........................

cross section see as long, side become tall

far near high low each got something more

don't know lu mountain true face how to see

only fate cos your body in mountain be

Your thoughts, your beliefs and even your questions limit you from seeing the true nature of things.

#题西林壁#苏轼#Su Dongpo#my favourite song has a line that goes#who knows which line will be sung and passed on forevermore#谁知道哪一句会千古吟传#it's so TRUE#objectively simple but my brain sure tied itself in knots#it's not leaving the mountain physically to get a better look at it#it's the knowing of where you are and understanding the context#and then asking the right question#but to do that you have to take a step back and see your situation for what it is#Maybe where you stand does limit what you perceive...#but if you think that is a Problem then you have not seen Mt Lu's true face#commentary#poems

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

苏轼诗词赏析

水调歌头•明月几时有

丙辰中秋,欢饮达旦,大醉,作此篇,兼怀子由。

明月几时有?把酒问青天。不知天上宫阙,今夕是何年。我欲乘风归去,又恐琼楼玉宇,高处不胜寒。起舞弄清影,何似在人间?转朱阁,低绮户,照无眠。不应有恨,何事长向别时圆?人有悲欢离合,月有阴晴圆缺,此事古难全。但愿人长久,千里共婵娟。

译文:明月从什么时候开始有的呢?我拿着酒杯遥问苍天。不知道天上的宫殿,今晚是哪一年。我想凭借着风力回到天上去看一看,又担心美玉砌成的楼宇,太高了我经受不住寒冷。起身舞蹈玩赏着月光下自己清朗的影子,月宫哪里比得上在人间。月儿转过朱红色的楼阁,低低地挂在窗户上,照着没有睡意的自己。明月不应该对人们有什么怨恨吧,可又为什么总是在人们离别之时才圆呢?人有悲欢离合的变迁,月有阴晴圆缺的转换,这事儿自古以来就很难周全。希望人们可以长长久久地在一起,即使相隔千里也能一起欣赏这美好的月亮。

赏析: …

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

hope everyone's been enjoying the full moon! here is a poem by Su Dongpo about the Mid-Autumn Festival. rough draft translation below:

Su Shi - To the tune "Prelude to Water Melody"

At Mid-Autumn of the Bingchen year [1076 AD], I celebrated and drank until dawn. Very drunk, I composed these verses while thinking of Ziyou.

Moon, what time is it? Do you know?

I raise my cup and ask the blue skies.

I wonder - in the palace above

It is Mid-Autumn, but which year?

I want to ride the wind and return home up there

Yet the jade palaces and houses make me fear;

The high places are too cold to bear.

I rise and dance, creating a shadow so sharp

He might be real on Earth.

You turn about the scarlet pavilions

And dip under the painted doors

Sleeplessly shining.

I suppose you don't hate us:

Why else are you full when it is time to depart?

We sorrow, rejoice, part, and meet again.

You darken, shine, wax and wane.

This world's ancient troubles seem absolute

But I hope that we, for ages to come,

Reunite from however far under your beauty.

--

水调歌头·明月几时有

苏轼

丙辰中秋,欢饮达旦,大醉,作此篇,兼怀子由。

明月几时有?

把酒问青天。

不知天上宫阙,

今夕是何年。

我欲乘风归去,

又恐琼楼玉宇,

高处不胜寒。

起舞弄清影,

何似在人间。

转朱阁,

低绮户,

照无眠。

不应有恨,

何事长向别时圆?

人有悲欢离合,

月有阴晴圆缺,

此事古难全。

但愿人长久,

千里共婵娟。

--

really curious how people interpret the first line! "几时有" reads to me like it's the reverse of normal grammar, and so... i don't know! initially i put down something very equivocal like "how much time do you hold?" in the hopes of Capturing All Possible Meanings, and i hated it, so at the last minute switched it out for something with a very definite interpretive stance.

English translation by Qian Jia in the Global Medieval Sourcebook

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

poetry lines befitting MCS and XJY

These are mostly chinese tang shi and song ci poetry quotes, with a great biased amount from Su Shi because OP doesn't know better. Crude, 5-minute english translations below. There are lines I semi-made up or adapted from fandom/cpop songs (that is, most of Xiao Jingyan's lines), ngl OP is rather embarrassed of them because they aren't good at all looking back now but we'll just leave them here or else XJY would end up with zero quotes.

梅长苏 Mei Changsu

想那日束髪从军,想那日霜角辕门,想那日挟剑惊风,想那日横槊凌云。 ——夏完淳

Think to the day I tied back my hair and enlisted. Think to the day the horn rang at the frostbitten tents, think to the day I danced my sword making the sound that deafens the wind. Think to the day I took to the lance, and it pierced through the skies, rising higher than the clouds. — Xia Wanchun

将士百战身名裂。 向河梁、回头万里,故人长绝。 易水萧萧西风冷,满座衣冠似雪,正壮士、悲歌未彻。 ——辛弃疾

The warrior fights a hundred battles, yet what remains is his severed reputation. He looks to the bridge over the river, thousands of miles back, past acquaintances forever gone. In another life, over the howling of the west wind and the cold Yi rivers, the banquet sits, clothes adorned in snowlike white. The courageous man strides through the blizzard, the song of lament never ceasing. — Xin Qiji

零落成泥碾作尘,只有香如故。 ——陆游

The plum blossoms wither and drift to the ground, crushed into earthly soil and dust. The prevailing fragrance is what remains. — Lu You

亦余心之所善兮,虽九死其犹未悔。 ——屈原

So long as this is what my heart longs for and treasures, though I die nine deaths, my heart does not regret. — Qu Yuan

君臣一梦,今古空名。 ——苏轼

Lords and lieges ebb into nothing but a dream; in the river of time transcending present and past vain titles remain, cast into the void. — Su Shi

无波真古井,有节是秋筠。 ——苏轼

The heart is at peace like the ancient well that does not start ripples; the integrity is as the autumn bamboos, steadfast and unfaltering. — Su Shi

舳舻千里,旌旗蔽空,酾酒临江,横槊赋诗。 ——苏轼

The battleship moves a thousand miles, ensigns enshrouding the sky. He pours out wine by the riverside, holds out his lance, and writes verses as he speaks. — Su Shi

对一张琴,一杯酒,一溪云。 ——苏轼

Facing but a guqin, a glass of wine, a stream of cloud. — Su Shi

江山如画,是我心言。 ——风起时

The rivers and mountains of the kingdom outstretched before me as moving as in art: this is my heart’s will. — from the song “Feng Qi Shi”, when the wind blows

战骨碎尽志不休,冰心未改血犹殷。 ——改自《赤血长殷》、王昌龄

Bones completely crushed from the battle, yet aspirations unwavering. The heart has not changed, and the blood flows red still. — adapted from the song “Chi Xue Chang Yan”, the noble blood flows red, and poet Wang Changling

袖手妙计权倾变,敛眸笑谈意了然。 ——改自《赤血长殷》

With folded arms, he devises labyrinthine strategies, and the sceptre of power sways and shifts. He shrouds his gaze modestly and in conversations of small smiles, he perceives astutely the intention of men. — adapted from the song “Chi Xue Chang Yan”, the noble blood flows red

萧㬌琰 Xiao Jingyan

潜龙一朝御风翔,长歌挽弓射天狼。 ——《长喑》

The submerged dragon rises one day to ride the winds. Singing high and long; the bow is drawn pointed to the invading Sirius. — from the song “Chang Yin”, the Long Darkness found here

挑灯殿阙思悄然,闻钤行宫寝无眠。 ——改自白居易

Washed in the raised lamps of the imperial palace, thoughts whisper in grievance. The bell rings at the Jiu’an grounds, and he lies abed sleepless. — adapted from The Song of Everlasting Sorrow by Bai Juyi

驰骋沙场繁华梦,谈笑鸿儒君臣纲。 ——改自《致陛下书》、刘禹锡

Dreams fly to the flurry of gallops in the battlefield, flourishing dreams of splendour and joy. In pleasant dialogue with the scholars, civility forces polite smiles back into the etiquette between lords and lieges. — adapted from the song “Zhi Bi Xia Shu”, a letter to Your Majesty, and Liu Yuxi

铁马并辔封疆,几回魂梦游;更鼓落夜未央,笔下兴亡断。 ——取自《长喑》、《赤血长殷》

Armoured horses riding in parallel at the borderlands — how many times has the soul wandered to such dreams of the past. The hourly drums sound ceaseless through the long night; under the emperor's brush writes the fate of prosperity and declination. — adapted from the song “Chang Yin”, the Long Darkness found here, and “Chi Xue Chang Yan”, the noble blood flows red

揽尽山河只手倾,昂冕袖手瞰苍生。 ——改自《长喑》

The future of his kingdom sweeps into a tilt of his hand. With crown upheld, he folds his arms in his sleeves awatching humanity. — adapted from the song “Chang Yin”, the Long Darkness found here

咫尺抚眉峰,万丈叠远峰;梦底枕笑纹,惊风掀水纹。 ——《致陛下书》

Up close the furrowed brows are smoothed. The ten thousands of feet stretch before the kingdom, converging as mountains at a distance. In the deepest dreams the markings of a smile lie; he disturbs the wind, which marks and rips tides in the tumultuous waters. — adapted from the song “Zhi Bi Xia Shu”, a letter to Your Majesty

Two (three) things to note:

My dying obsession with Su Shi, sorry I can’t help it that perhaps over half of the all the poetry I know is from him;

To be really fair, my favourite description of Mei Changsu is 运筹帷幄之中,决胜千里之外, used in describing Zhang Liang in Si Maqian's Records of the Grand Historian. He plots strategies in the tent of the army; he determines the victory of the battle thousands of miles from the front of the battlefield.

As for my favourite depiction of Lin Shu, it is definitely Su Shi’s description of Cao Cao: 舳舻千里,旌旗蔽空,酾酒临江,横槊赋诗。 The battleship moves a thousand miles, ensigns enshrouding the sky. He pours out wine by the riverside, holds out his lance, and writes verses as he speaks. Xin Qiji’s verse above just fits the entire story of Mei Changsu so much, it deserves a mention.

I was assembling/making these lines up for something back then and so just listed whatever came to mind (for reasons I know not I kept on listing stuff for MCS, but maybe XJY was the typical good emperor kind of person so wasn't as inspiring coming up with quotes for him).

If there are lines of poetry you find really befitting the two characters, we're more than interested starting a thread here just for that purpose.

#chinese language#chinese poetry#su shi#nif#nirvana in fire#classical chinese poetry#langya bang#lang ya bang#mei changsu#xiao jingyan#jingsu#fate creates#fate translates

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

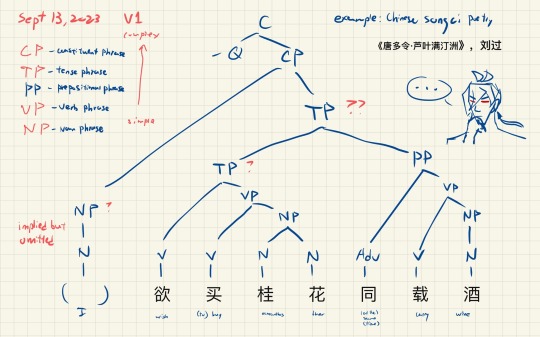

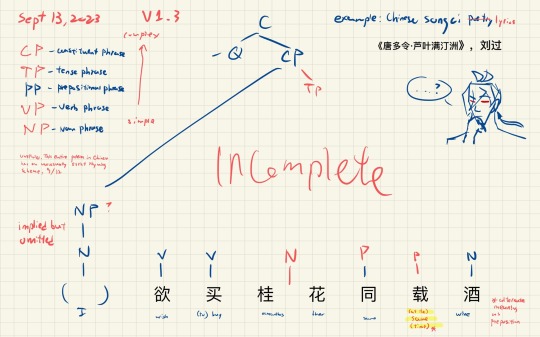

“欲买桂花同载酒” / Zhongli’s osmanthus wine idle line

(Disclaimer: I don’t know that much about syntax, so I apologize for the wildly inaccurate syntax trees. I made the mistake of warming up with something that’s not English prose haha… I’ll be focusing on the meaning of the line and its hanzi characters, so the syntax is only there to help me explain some things.)

.

“欲买桂花同载酒”…

.

This line is from the Chinese songci (宋词, a form of traditional Chinese poetry) 《唐多令·芦叶满汀洲》,by 刘过 (Liu Guo). It’s the one referenced in Zhongli’s osmanthus wine idle line in Chinese. (By the way, it does not directly mean “Osmanthus wine tastes the same as I remember”, but more on that later.)

载 (zai3) as a verb could have the meaning of “to carry (something)(with a vehicle)”. For example, “这车可载三箱酒。” = “This car can carry three crates of wine.”

And since the rest of the songci talks about a harbour scene with boats, 载 could indeed be seen as a verb in the poem’s context, and the vehicle is implied to be a boat. So in the context of the songci, this line could be understood in English prose as “[I] wish to buy some osmanthus and ride [a boat] along with some wine.”

.

However, despite the songci’s context, none of these hanzi characters in the line itself directly mean “boat”. While looking at it closer today, the syntactic structure felt a little strange to me even though I’m not familiar with Chinese songci syntax.

It turns out 载 has multiple meanings. 载, pronounced with the fourth tone (zai4), as a preposition used in pairs (in modern Chinese), could mean “simultaneously” or “at the same time”. For example, 载笑载哭 should probably mean “laughing at crying at the same time” or “laughing while crying”…

Also, the original songci doesn’t follow the osmanthus line with a section about old friends, but instead the idea of old friends is actually mentioned two lines prior. For the bolded sections, I’m doing a modern English translation, referencing the modern Chinese translation from the Gushiwen website here, but note that the original songci uses the poetic Chinese wenyan (文言) syntax.

.

“黄鹤断矶头,故人今在否?旧江山浑是新愁。欲买桂花同载酒,终不似,少年游。”

“故人今在否?” = “Are [my] old friends still alive in this moment?”

“欲买桂花同载酒” = “[I] wish to buy some osmanthus and ride [a boat] along with some wine.”

.

It’s pretty cool that Genshin Impact alluded to the friends idea present in the poem too. Also, both Liu Guo’s songci poem and Zhongli’s line use the term 故人 (gu4ren2) to mean “old friend(s)”.

.

Meaning, Zhongli’s poetic-sounding Chinese idle line “欲买桂花同载酒…只可惜故人,何日再见呢?” is closer to “I wish to buy some osmanthus and also some wine… But as for those old friends, when would I meet them again?” in modern English with the game’s context (without taking into account that the real poem alluded to here is about boating). (This is a rough translation that follows the overall sentence structure in Chinese a little closer.)

Thus Genshin Impact’s English localization of “Osmanthus wine tastes the same as I remember… But where are those who share the memory?” might actually be okay in terms of meaning even if it lacks the nuance from the poetic reference. Well, I would’ve liked the first part (the songci) to be localized in Shakespearean English, and the second part to be in modern English, since the difference in syntax and tone still stands out a lot in Chinese… In an English localization, if a character who usually speaks in English prose suddenly quotes something in Shakespearean English, it’s easier to pick up on the fact that it might be a line of poetry ‘cause of the contrast, I believe.

.

Somewhat unrelated, but in terms of poetic structure, it seems the entire poem in Chinese has an usually strict rhyming scheme, rhyming nine out of the twelve ending sounds together (roughly speaking. Not gonna go into the phonology of it haha)

Usually Chinese songci have a more diverse (?) rhyming scheme. E.g. “水调歌头•明月几时有” by 苏轼 (Su Shi), which miiight be the base inspiration for Liyue’s general storyline and cast

.

In the end… Zhongli quotes a line of songci with seven hanzi/syllables. It’s a wild guess but maybe it refers to the original Seven Archons?

欲买桂花同载酒…只可惜故人,何日再见呢…

#dusk analysis#Genshin translation#zhongli#songci#Chinese poetry#osmanthus wine#Genshin analysis#钟离#宋词#原神#欲买桂花同载酒#translation#syntax#linguistics#Liyue#genshin impact#Chinese#game translation

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

♪ 白酒分你一半

大张伟:月亮弯弯,绵绵绵绵缠缠。果汁分你一半 爱相互分担。

李白:月亮弯弯,绵绵绵绵缠缠 。白酒分你一半,忧愁互分担。

苏轼:雨途慢慢,料料峭峭寒寒。白酒分你一半,竹杖来扶搀。

#baijiu drinkers anonymous#not really#today's shitposting#chinese poetry#ponz.txt#hahahahaha#i watch that 我们的歌 clip way too much haha#*wait - baijiu drinkers and moonfuckers anonymous#our poetry club is nonsens

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Episode transcript here.]

苏轼 Su Shi (Su Dongpo)

江城子·乙卯正月二十日夜记梦 Dream, 20/1/1075

十年生死两茫茫,

不思量,自难忘。

千里孤坟,

无处话凄凉。

纵使相逢应不识,

尘满面,鬓如霜。

夜来幽梦忽还乡,

小轩窗,正梳妆。

相顾无言,

惟有泪千行。

料得年年肠断处,

明月夜,短松冈。

ten years -- the haze of distance between the living and the dead

one doesn't think on it much

one never forgets it

a thousand miles of lonely graves

nowhere for my living voice to speak misery

even if we meet again, you would hardly know me

a face full of dust

white in my hair

with a strange dream at night i am suddenly back home

that little window

where you are getting ready

we look at each other, but words don't come

only a thousand lines of tears

i will be waiting every year at the place of my heartbreak

the bright moon at night

a mound of short pines

Further reading:

#gushiwensday translation by garden-ghoul

Notes by Nina Du, Runqi Zhang, and Dante Zhu; translation by Quan Jia (Global Medieval Sourcebook)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Three Poems for the End of the Year” (歲晚三首) Translation

(Happy Spring Festival/Lunar New Year/Chinese New Year to all! I thought this series of poems was a good introduction for certain traditions and customs surrounding the festival, so here they are, please enjoy!)

Three Poems for the End of the Year

By Su Shi (Song dynasty, 1062 AD, 11th century)

Exchanging gifts at the end of the year is called “gifting the year” (1); inviting others to feast together is called “sending off the year” (2); keeping vigil through the night of the eve is called “watching over the year” (3). Such are the customs in Shu (4) (5). Since I am now a government official in Qixia (6) and cannot return home at the end of the year, I am writing these three poems here for Ziyou (7).

Gifting the Year (1)

Each household’s harvest is now done, which will aid in the yearly event (8).

Worried about missing out on the festivities, people exchange presents freely.

The contents vary according to their place of origin, the poor gives little while the rich gives plenty.

An enormous carp lays across the plate, within the cage rests a pair of rabbits.

The wealthy displays extravagance, their embroidered silks glowing in lustrous hues.

The poor cannot afford the luxury, and opted for small gifts of pastries.

The official residence doesn’t have familiar faces, while the celebrations continued in the alleys.

I wish to celebrate with the customs of my hometown, yet there's nobody who will join me.

Sending Off the Year (2)

Faraway lives my old friend, reluctantly do we part.

Though people can return to visit, the years never will.

Where have the years gone? To the ends of the earth.

Off chasing the east-flowing waters (9), and into the timeless seas.

The neighbor to the east has the well-aged wine, and the neighbor to the west owns the fattened pig.

All for a day’s festivity, to compensate for the melancholy of the ending old year.

But never be consumed while mourning this loss, lest you forgo the fresh new year.

If one looks back while moving forward, old age and infirmity shall catch up.

Watching Over the Year (3)

The year shall soon end, a long snake swimming towards the gloomy depths.

Its slender scales already half out of view, who can hide its intention to leave?

And if one wishes to tie up its tail, though diligent this is still in vain.

Trying their best to fight off sleep, children play merrily into the night.

Wishing the morning rooster won’t crow, my anxiety grows amid the urging of the geng drums (10) (11).

Sitting through the night whilst petals of ash drifts from the lamp (12), the Big Dipper already askew when I stand up.

Will the New Year be absent next year? I fear what’s on my mind will be delayed again.

The youth who can cherish this singular night, their will and spirit are praiseworthy indeed.

—————————-

Notes:

“Gifting the Year”/饋歲/馈岁: refers to the custom of exchanging gifts at the end of the year.

“Sending Off the Year”/別歲/别岁: refers to the custom of feasting on the 29th day of the Twelfth month in order to “bid farewell to the old year”.

“Watching Over the Year”/守歲/守岁: refers to the custom of staying up through the entire night of the eve and the early hours of the first day of the new year; lamps and candles are also kept on or lit through the night so the light can rid the residence of all evil, pestilence, and illness in preparation for the new year.

Shu/蜀: name of a region; the archaic name of the region known today as Sichuan/四川.

The first two sentences in Su Shi’s introduction here are a direct reference to the records of New Year’s customs from the Jin dynasty (266 - 420 AD) book 《風土記》 by Zhou Chu/周處/周处. In fact, Su Shi’s description here is a paraphrase of the same information in 《風土記》: ”蜀之風俗,晚歲相與餽問,謂之餽歲。酒食相邀為別歲。至除夕,達旦不眠,謂之守歲”.

Qixia/岐下: refers to the foot of the Qishan/岐山 mountain in Shaanxi province/陕西省 today.

Ziyou/子由: courtesy name of Su Shi’s younger brother Su Zhe/蘇轍, the recipient of this letter.

Yearly event/歲事: implies the New Year’s festival, colloquially called “passing the year” (Guonian/過年/过年 or Dusui/度歲/度岁) or “yearly festival” (Nianjie/年節/年节), now known more widely as “Spring Festival”/春节 (this name came about in 1914 from an official document), “Lunar New Year”/农历新年, or “Chinese New Year”.

East-flowing waters: a common Chinese literary motif that refers to the passage of time; this is because both Yangzi River and Yellow River flow eastwards.

Geng drum: a drum carried by night watchers, called Gengfu/更夫; gengfu will sound the drum every Shichen/時辰/时辰 (1 shichen = 2 hours) during the night while he is patrolling the streets and on the look out for potential dangers like fires or robbers.

It should be noted that in the old times, age is calculated as “1 year old” at birth, and increases by 1 every New Year’s festival (the resulting age number from this traditional age calculation method is now called Xusui/虛歲/虚岁). This is reflected in the character sui/歲/岁, which means both “age” and “year”. This also means that in the old times, everyone has a birthdate, but there are no annual “birthdays”. Now we can understand Su Shi’s anxiety while waiting for the old year to end: he will be considered “1 year older” after the eve ends, which reminds him that he’s aging.

Petals of ash: refers to the ash left by the burning candle wick.

—————————-

Original Text (Traditional Chinese):

《 歲晚三首 》

[宋] 蘇軾

歲晚相與餽問為“餽歲”;酒食相邀呼為“別歲”;至除夜達旦不眠為“守歲”。蜀之風俗如是。餘官於岐下,歲暮思歸而不可得,故為此三詩以寄子由。

《 饋歲 》

農功各已收,歲事得相佐。

為歡恐無及,假物不論貨。

山川隨出產,貧富稱小大。

置盤巨鯉橫,發籠雙兔卧。

富人事華靡,彩繡光翻座。

貧者愧不能,微摯出舂磨。

官居故人少,里巷佳節過。

亦欲舉鄉風,獨唱無人和。

《 別歲 》

故人適千里,臨別尚遲遲。

人行猶可復,歲行那可追。

問歲安所之?遠在天一涯。

已逐東流水,赴海歸無時。

東鄰酒初熟,西舍彘亦肥。

且為一日歡,慰此窮年悲。

勿嗟舊歲別,行與新歲辭。

去去勿回顧,還君老與衰。

《 守歲 》

欲知垂盡歲,有似赴壑蛇。

修鱗半已沒,去意誰能遮。

況欲系其尾,雖勤知奈何。

兒童強不睡,相守夜歡譁。

晨雞且勿鳴,更鼓畏添撾。

坐久燈燼落,起看北斗斜。

明年豈無年,心事恐蹉跎。

努力盡今夕,少年猶可誇。

#my translation#chinese poem#poetry#chinese new year#lunar new year#spring festival#year of the rabbit#three poems for the end of the year#岁晚三首#苏轼

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

20231019#Robe#South Australia #20240109#

人生如逆旅,我亦是行人。

宋代苏轼《临江仙·送钱穆父》

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

定风波·莫听穿林打叶声 - Still the Wind and Waves • heed not the sound of rain in the forest

by 苏轼 (Su Shi, 1037 - 1101)

三月七日,沙湖道中遇雨。雨具先去,同行皆狼狈,余独不觉,已而遂晴,故作此词。

On the seventh day of the third month, midway on Sandylake Road, we met with rain. Those bearing rain gear went on ahead. My traveling companions were all miserable and disheveled, only I did not feel discomfited. Now that the sky has cleared, I pen these words.

莫听穿林打叶声,

mò tīng chuān lín dǎ yè shēng

Heed not the sound cutting through the forest, battering leaves.

何妨吟啸且徐行。

héfáng yín xiào qiě xú xíng.

Why not sing and whistle along as you tread?

竹杖芒鞋轻胜马,

zhúzhàng mángxié qīng shèng mǎ,

On bamboo staff and wicker sandals light and swift, better suited than a steed,

谁怕?一蓑烟雨任平生。

sheí pà? yī suō yānyǔ rèn píngshēng.

who is afraid? Straw-cape draped, weathering a lifetime's unchecked misty rain.

料峭春风吹酒醒,

liàoqiào chūnfēng chuī jiǔ xǐng,

A sharp Spring breeze dissipates my drunken haze.

微冷,山头斜照却相迎。

wēi lěng, shān tóu xiézhào què xiāngyíng

It is chilly. Yet on the mountaintop, the slanting rays of the setting sun are welcoming.

回首向来萧瑟处,

huí shǒu xiàng lái xiāosè chù,

I look toward the way we came where leaves rustled in the cold -

归去,也无风雨也无晴。

guī qù, yě wú fēngyǔ yě wú qíng

on the return journey, there was neither a storm nor a cloudless sky.

......................................................................................

I’ve been curious about something for a while, and thought this poem particularly suitable for a little experiment.

Usually, when I translate a song or poem, if its not for a story or drama that I already know, then I like to go into it with as little knowledge of the context as possible. It’s interesting to see what changes in the interpretation before and after finding out more.

I get especially confused for the works of poets whom I’m not already familiar with! And sure, the confusion is fun and sometimes the results are funny - but it also makes me want to know how these things sound like after translation to English with zero background information.

So, if you don’t mind, feel free to leave a sentence or two anywhere - tags, comments, asks, messages etc. - on what comes to mind as you read this poem, or what you think it’s about.

(Meanwhile, I shall continue doing the same on my google docs xD)

#定风波·莫听穿林打叶声#苏轼#定风波#poems#su shi#i first heard of this poem through a zhou shen song for brotherhood of blades ii#honestly#back then i didn't understand it at all#now i feel like that understanding is juuuuuust a little out of reach#in that i can't really shift myself into those emotions and that perspective#(yj is just a lazy cat who loves stories)#curious about how everyone interprets this!#esp the line about the straw cape and also the last line#also fine i admit this is a 光亮 thing#i can't believe after like 4 years we've circled back to zhou shen

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Excerpt from 石蒼舒醉墨堂 "Hall of Drunken Ink" (1080) by Su Shi (苏轼)

人生識字憂患始,姓名粗記可以休。

何用草書誇神速,開卷惝怳令人愁。

我嘗好之每自笑,君有此病何年瘳。

自言其中有至樂,適意無異逍遙遊。

"All worry and woe in life begins from learning to read and write,

be able to roughly mark your name and then you should call it quits.

What point is there in cursive draft that flaunts the spirit's speed?

the blur in my eyes when I open a scroll makes me ill at ease.

Yes, I too have been fond of it, but always I laugh at myself;

how can we cure this affliction as it shows itself in you?"

(translation is by stephen owen, i think)

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Muse, Hello dear Ribbon what are your favourite words in English and also in your Native Language and letters?

Off the top of my head it's wondrous, sky, flower, forest, warmth, oceanic and radiance.

In my native language (Chinese) it's a poem by 苏轼 —

“人有悲欢离合,月有阴晴圆缺,此事古难全。但愿人长久,千里共婵娟。”

A translation:

"People have sorrows and joys, partings and reunions, even the moon has times when it's bright and dim, waxing or waning, such things have never been perfect since the olden days. We wish everyone a long life so we can share the beauty of the moonlight, even if miles apart."

Thanks for asking!

6 notes

·

View notes