#(due to concerns over race and class solidarity)

Text

everytime i rewatch black sails, i find myself like vane more and more ngl. the first season really tries hard to trick you into thinking he’s just unnecessarily, banally, and uncompellingly an asshole (in the overwhelmingly compelling asshole show), whose one redeeming feature is that he’s kinda pathetic too. but geez s2 really nails home everytime that hes the best and the coolest and the most honest (maybe even most compassionate) of the mcs up until this point, barring anne of course. and on top of that i actually kind of think he has the best pre-s3 speeches. like obvs s4 flint is yknow s4 flint. and s3 max is so insane i actually cant handle it. but oh my god charles vane’s letter and his fuck your legitimacy eleanor speech and his hanging speech are so good. and fuck what i said earlier isnt even true. bc his s1 speech while hes looking in the eyes of the little boy he used to be is actually like the bestest. like fuck ok. charles vane is the best actually. #1 anarchist boy. 10/10 would want him in my commune. hed point blank refuse to help with the dishes tho so 😬.

#black sails#charles vane#kaz queuekker#i know other people have said this before#but i always forget how much this dude rocks#his cheesy archetypal veneer#makes him so easy to overlook amongst all the brighter shinier characters#its genuinely such a crime they wasted him on a stupid blackbeard plotline#when we could have had him w/madi in the maroon plotline#or even touched on what they were even trying to so w/the white slave plotline#which makes zero sense to do in a show set in 1715#a whole charles vane lifetime (maybe) after bacon’s rebellion#and the shift away from indentured servitude#(due to concerns over race and class solidarity)#in favor of racialized heavily codified and lifelong inherited slavery#which while again is too early for the showz setting#wouldve at least been thematically relevant#a million times more than a lazy regurgitation#of the mythologizing blackbeard thing#in the deconstructing pirate myths show???#but i digress

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

title: half doomed and semi-sweet

word count: 5308

summary: Idia's bad luck comes back to haunt him again, being dragged into physically showing up to class and being assigned a group project involving a student from a different year, courtesy of Mr. Trein. His... "best friend", Kero Tricarenia, sees his distress in the situation, and swoops in to save him, though that might be what actually ends him instead of the project...

commissioned by @chibichibisha , available on ao3 here ! tysm for the commission, i hope you like it! you have no idea how excited i was to write kero asjkdfsf-

my guidelines for commissions are here, in case anyone else is interested !

Of course that in the day Idia is made to actually show up to class, something like this happens.

The fact that it’s Trein’s class just makes it somehow worse. Of course, it’s not all bad, he gets to see Lucius napping on the teacher’s desk—! ...but, he also gets to be pestered by Cater the second he’s walking in, and then the second he’s walking out, plus, just the presence of all these people… Idia shudders just thinking about it.

He pulls his hoodie closer to his face, trying to shield it in vain. He just wanted to go back to his room. Trein was the worst for making him actually show up. He’d been attending classes through the tablet for so long, what was the issue with today specifically? Why couldn’t he just do it the way he always does? He just doesn’t get it—

“Before class is dismissed,” Trein starts in that voice of his, commanding yet with a hint of a drawl that makes Idia want to delve into eternal slumber. “I have an announcement to make. Due to recent events, the headmaster has assigned the teachers the task of building… teamwork, and solidarity, between students, even the ones in different years, and I’ve been chosen to apply that, so your monthly History assignment will work somewhat differently this time.”

Great. Awesome. These were his favorite words in the whole world. As if today couldn’t get any worse.

“I’ll need you to gather a pair or trio with students from different years, to build a mockup representing a historical event of your choosing. You’re supposed to inform me of your groups until tomorrow's class, and the deadline will be held two weeks from now, on February 13th. You’ll be presenting your works the day after.”

Idia feels the clammy hands of dread on both his ankles, threatening to pull him under. Of course this would get worse somehow. He exhales a deep sigh, burying his face on his hands… he’d have to email Mr. Trein about doing the assignment by himself later. And it’d be such an unpleasant conversation, with how he insisted on having students follow all these traditional learning methods.

Really, why the hell were they getting group projects now, out of all things? They had one foot out of school, basically. Fourth year barely had any classes, most of the students’ times filled up with internships and research so what did they get out of trying to “develop teamwork skills” within their students? None of these people would be talking to each other by the time they graduate, anyways… they were wasting resources to max out a stat that didn’t matter.

He tugs the hood of his jacket over his face again as he walks out of the classroom, sneaking outside like he’s avoiding to get scolded — The blue glow of his hair insisting on sticking out, Idia feels his heart race and squeeze while he makes his way across the crowded hallways. He swears he hears Cater’s voice calling for him as he leaves, too… but maybe he’s just making it up, because of how especially cursed he feels today.

What an awful morning, really. At least locking himself up with that MMO he’s gotten hooked on recently would feel even more cathartic.

After the nerve-wracking walk, Trein’s words poking at him like imps with their tridents — Him trying to figure out how to convince that teacher to let him do everything by himself, no presentation included, without having to actually face the guy — Idia finally gets back to his dorm. Finally.

He releases a breath he didn’t know he was holding — Just like in the fanfics, geez — when he steps into the lounge, though even the mostly vacant blue and white space felt a little oppressive now. Sure, he cared about his dormmates, they were fine people, but they were still people, and what he really needed now, was…

“IDIA!”

...within one second of the click of his door being unlocked, Idia is reminded once again that he never will know peace.

“K-Kero!” He yelps, suddenly overwhelmed by a hug, arms around his entire body squeezing him tight, maybe too tight— It’s a second before he remembers this is in fact supposed to be his room. “W-Wait, what are you doing here? That’s my room!”

Unleashed from the mighty grip, red eyes meet Idia’s as Kero’s head tilts, a smile on his face flashing his sharp teeth.

“I know that! I was looking for you.” He just announces, following right behind with that skip on his step as Idia enters and locks the door behind them. He hadn’t seen Kero in… how long, now? It’d been a while, that much he knew. Idia had been busy lately, with… “You finished that tournament yesterday night, right? How did you do? I got you that cake from the cafeteria you like to celebrate!” His questions are rapid-fire, tail wagging as he rushes towards Idia’s unmade bed to pick up the little packaged treat he’d gotten.

“You don’t even know how it went yet, but you’re already getting your hopes up.” Idia grumbles, but the second the package is placed on his hands, he does gracefully accept it. “Well, my team did win, so…”

“Yes! I knew you would!” Kero cheers, grinning again as he sits on his bed. He’s… so full of energy it’s hard to watch, Idia would say.

But, well, that would kind of be a huge lie.

“Yeah, thanks for leaving me be for a bit so I could practice.” He mutters, moving to sit on his desk chair. The package makes a crinkling plastic noise while he messes with it, opening it to reveal a slice of strawberry shortcake — That has him glancing at Kero for a second, a fuzzy feeling taking over.

...because that’s just what his emotions do now.

It was stupid, Idia’s sighing tiredly just thinking about it — When it started was beyond him, but for some reason or another, something keeps pulling him towards Kero. It’s not exactly a big deal, some sort of soul-binding string of fate or something like that, but even when he’s not there physically, Kero lingers, flashes of sharp teeth and boisterous laughing in Idia’s mind. It’s not a big deal! But it’s like Kero had hanged around him so much he left a mark.

And Idia doesn’t really hate that. He stares at the cake in his hands, and thinks of Kero smiling as he got it for him, without any sort of request, just because he saw the cake and remembered that he liked it, and his mind stresses just how much he doesn’t hate that.

(...well, it was a sort of doomed thing, they would never move on from this strange affectionate friendship, because Idia isn’t going to… tell Kero he’s crushing on him, or anything like that. That’d just screw everything up. And what he has now isn’t actually bad at all. Really, it’s fine if Kero never understands. It’s fine. )

“Are you… good, though? Do you need anything?” Kero asks, snapping him out of the messy daydreams with another good natured tilt of his head — He’s a dog alright. “You… just look kinda gloomy and stuff.”

Idia snickers, shaking his head. “Yeah, like I ever look different.” He mumbles, and takes a bite of cake. It’s sweet, he thinks, making a surprised noise as he wonders when the last time he had it was… he licks some whipped cream off his fingers. “Mm, this time is different though. Something with a group project from Mr. Trein… tires me out just to think about it.” He sighs. But Kero’s ears perk up, pointing straight upwards.

“Oh! That, yeah. He told 2-D about it today too.”

“Yeah. This sucks. I’m just gonna… find a way to work by myself.” Idia shakes his head, sinking on his chair a little further. He bites into the cake again. “You think Mr. Trein knows how to read emails?” He snickers, but the thought of having to meet him face-to-face makes his skin crawl. “...ugh, I d-don’t wanna have to talk to him during office hours…”

Kero hums in slightly concerned acknowledgement, plopping down on his bed with attentive eyes. Idia finds himself in a weird wondering of how it felt like to sit down when you were a beastman. Did it hurt his tail or something? It’s wagging against the mattress, though. His ears point to opposite sides while he looks up vaguely. Idia muses about what he might be thinking about.

“Well, you could always do it with me! They said to get one of your underclassmen, right.” Kero suggests, and… Idia swears he sees his tail wag a little harder, but that could very well just be a trick of the light. “I can do the presentation too, and I’m good with building things, so…” He grins. “Plus, you won’t have to… talk to Mr. Trein.”

Idia hums through a mouthful of cake. Well, doing the project with Kero would certainly be better than with someone he didn’t know. However, it’s…

His eyes linger on Kero’s expectant form on his bed, smiling so cheerfully. He’s very aware of the couple feet of distance between them right now, and even like this, Kero’s presence does things to his heart… that’s bad, so bad, he thinks, it’s hard to ignore how his heartbeat is just a tad faster now, summed with this different flavor of nervousness that just seemed to simmer in his blood now… yeah, it’s no good.

“I m-mean, I guess I wouldn’t mind that.” Is what he stutters out. Kero beams.

Stupid cute Kero. This isn’t helping Idia convince himself none of this is a big deal.

“Yeah! If you’re doin’ a project you might as well do it with your best friend, right?” He says. Here he is again with the best friend talk… oh, if only he knew. “We can have fun with it too. Actually, I can have fun with everything as long as I’m with you, heh.”

Idia feels heat creeping up his neck. Stupid cute Kero! “Ugh, you d-don’t gotta be embarrassing about it.” He mumbles, eyes averted. The cake finished with one last bite, Idia places the empty package on his desk, licking leftover cream off his fingers again. “We’re just putting some annoying mockup together. It’s not a big deal. If we add some simple machines to it to make it cooler it’ll already be higher-res than everyone else’s, it’s just an easy A. Everyone else’s just gonna use magic, I bet.”

“Yeah, obviously. I mean it doesn’t have to be annoying, though.” Kero comments. “We’ve gotta choose a historical event, right? Do you have any ideas?”

“Uhhh. The industrial revolution of the Isle of Lamentation? That’s… pretty much all I paid attention to this year, anyways.” He shrugs. Trein’s classes were boring, naturally. And they were so early in the morning, too… his tablet may have been there most of the time, but Idia himself was passed out on his bed.

“I think that works! We’ll have to make a bunch of stuff for the machines. But that’ll be fun.”

Idia hums. He’s thinking about these machines, actually, the miniature factories they could put together. The blueprints begin to write themselves up rather quickly. “We’d blow their little minds if we just had some… smoke coming out of the chimneys, some gears spinning around. Fuhihi, our mockup might be the best.” With his head in the clouds — Or the laboratory, rather — he finds himself grinning, waving a finger in the air. “Hey, Kero, what do you th… huh?”

And Kero isn’t on his bed anymore. He’s right there, in front of him.

Before Idia can say anything about this (Kero right in front of him, leaning in closer, he feels so cornered, his heart might stop!) Kero leans in even further, a big hand coming up to his face and (He’s going to die, definitely, he’ll die right here.) and he wipes off some whipped cream from near Idia’s lips.

“You had some on your face! Heheh.” He chuckles, licking it off his thumb. Idia feels like his blood pressure has just plummeted, or… or maybe it just did the opposite, how is he supposed to tell? His face feels so hot there’s no way his brain is getting the proper oxygen at all, he can barely think—!

“G-Give me a warning before you do something like this!” Idia wheezes, high pitched like a squeaky toy, and Kero just laughs again, grinning with this hint of mischief. “I didn’t even see you move!”

“Yeah, ‘cause you were distracted? I’m happy you’re excited about the project, though. I think it’s cute.” He says outright, and Idia… Idia just puts his hands on his face, averting his eyes with intent. Why does Kero have to be... so... much? “C’mon, you can sit with me on the bed. We can talk better like this.” A strong hand grabs at his wrist, easily looping around it as he pulls at Idia, making him squeak again as he’s dragged towards the bed.

“This doesn’t even make any sense!” Idia complains, but Kero tugs him towards the bed with no effort at all, and he just accepts his fate, huffing like it’d ease the warmth crawling all over his face. “Ugh, a-anyway, I was talking about the factories we’d put on the mockup… I thought of having some machines with exposed insides, with the spinning gears would be good, and conveyor belts that function…”

As he launches into explanation, Kero nods, making this unbreakable eye contact. Idia has to stop and take a deep breath every couple minutes, the situation somehow overwhelming. It feels like his condition just got a little worse every day, huh.

(Well, it’s fine. He could just avoid him if things got bad. Though… he doesn’t like thinking about this, recalling the week before the game tournament even. It’s kind of stupid, if he’s just making Idia nervous why does he have this need to keep him around? As expected, emotions make little to no sense...)

“...so, basically that’s what I thought.” Idia ends the explanation. Kero still has his attentive look on his face, almost like it froze there. “Did you pay attention?”

“Nah. I was just looking at you while you talked, ‘cause you looked so pretty.” Kero leans in with a smirk (Can he please stop trying to kill Idia, he’s just gotten down to a normal-ish heart rate again!) that then turns into one of his usual friendly smiles. “Kidding! I did, yeah. Do you wanna start it tomorrow?”

“You…! Uh, um, I don’t know. I wanna play my new game.” He stumbles with speaking, but it still comes out. At least. “We could probably finish that in, what, two days at most? If you don’t mind going to the lab late at night.”

“Roger that. For Idia, I’ll go to the ends of Twisted Wonderland!” He declares, fist thumping against his chest with a proud grin. “I’ll get us your snacks too. Can’t have you going hungry. But now I gotta go to track.”

Idia blinks. Already? He remembers that club meetings do in fact exist. He’d been skipping on his lately so he ended up kind of… forgetting them. Seeing Kero go, though, it’s…

“R-Right, I hope you, uh… enjoy yourself.” He stutters. Then he wants to hit himself on the face, really, what kind of stupid farewell was that? Just say bye and go back to your games, idiot. Luckily, Kero doesn’t seem to mind it.

“Yeah, yeah, I will!” He chimes, getting up from the bed — Leaning down a little, he puts a hand over Idia’s flaming hair, ruffling it to his surprise. “I’ll see you, okay? Literally. I’m coming over again later, ‘cause after all this time I’m not leaving my best friend alone!”

Idia feels frozen in place while Kero pets him, eyes zeroed in on that grin — Before he leaves, and he exhales. Again. That breath he didn’t know he had been holding.

He doesn’t play the game yet. Instead, he lays face down on the bed and screams into the pillow, whatever feelings had been simmering while Kero was around just exploding the second he leaves. Great Seven, he was so stupid. Both of them, actually.

Kero was stupid for not seeing how much this crush was clearly consuming him, and Idia… Idia was stupid for getting involved in any of this at all, in so many ways and for so many reasons, but he just can’t bring himself to stop now.

He swears it’s not that big of a deal. But it’s a lie, obviously. Clearly.

. . .

Once he’s back into his room after practice, Kero shuts his door behind him, and he laughs.

He feels the strain on his body from the running, sure, but every bit of it is somehow also filled with so much energy — With his hands on his face like how Idia does when he’s shy, he grins so much his cheeks hurt with the pulling. His heart won’t stop racing.

Who let him be so adorable!

He knew they’d end up doing this project together, of course. When Trein mentioned it’d involve students from different years, Idia was the first person Kero thought of! But the reality still makes him so giddy. To think he’d have a chance to do a project with him! He’s really been too lucky these days. Trein was… something else, to him, but with something like this, he might be willing to overlook the fact that the guy was absolutely terrifying.

Well, what matters is that he gets some more time with Idia — Even better, they’d be alone together! — The tournament week sucked, straight up. Kero ran some errands for him but it just wasn’t the same! Though he didn’t mind this sort of caretaking either, Idia barely took breaks. He didn’t even tell him much about the game he was playing, actually. Kero was basically crawling up the walls with how bored he’d gotten.

But that’s irrelevant now.

Still grinning and laughing to himself with all that burst of energy running through his skin, Kero hops over to his desk — With how he was, Idia would probably have some blueprints for the machines ready soon, but this was a nice chance to impress. He gathers some parts and tools, and gets to work.

...work that takes longer to complete than it usually does for him, but as expected, through the following days, Idia texts him vague guidelines on what their mockup should be like, ideas and half-baked blueprints that they discuss both through the phone and when he shows up at Idia’s place, and when the fated day of getting together at Ignihyde’s laboratory arrives, he has all those trinkets on his desk. He’s so ready.

ill see you there at 2, Idia’s text reads, bring the stuff i told u to make

Yes, yes, right away! Kero smiles bright as he gathers the miniature machines into a shoe box he’d gotten for them. He can feel his tail wag with excitement even as he carries it through the gloomy late-night corridors.

The door opened with a bang — Oops, he definitely handled it too roughly — Kero chimes as soon as he sets foot into the lab. “Idia!” He calls when he arrives. “I’m here!”

“Eek!” Idia, who was already leaned over the table, spreading scratchy blueprints and machine parts on it, is startled in a jolt. “D-Don’t sneak up on me like this! Geez…”

“Heheh, sorry, sorry.” Kero laughs, setting the box near the other items on the table, which Idia eagerly turns to inspect, complaints or not. Well, if that was the case, he’d inspect Idia for a bit too. He was looking unusual today, after all! Without that heavy jacket of his, wearing his lab wear and striped shirt. Kero’s heart leaps. “You’re looking good today, huh! ‘s unusual to see you looking like this, like… one of these R cards from your gacha games, or something.”

Kero feels proud of himself for the comment — Hey, Idia, look at me, I pay attention to your rambling! But Idia makes an offended noise instead.

“T...The R cards are the common ones, stupid.” He scoffs, giving him a narrow eyed look, but there’s still a soft flush of pink over his cheeks. “Ugh, I can’t believe I let you spend time with me when you don’t know that.”

Well. Kero tried, all he can do is laugh about it. At least he didn’t miss the compliment entirely! “Ehh, you do it ‘cause we’re best friends and you love me!” He says. “C’mon, we should get started on this already.”

“...y-yeah, yeah, whatever.” Idia shakes his head, but when he turns his face towards the table to look at their work in progress, there’s a slight smile on his blue lips that Kero couldn’t possibly miss. “Did you make the conveyor belts? I think I forgot to send you anything on these, couldn’t decide what material would be better for them…”

Moments like these are just so… so everything. Kero can’t find the words to describe how happy he is to be around Idia and be able to say things like that! Though, he feels it’s not exactly enough… even if all of this does feel nice, and he’s grateful for it.

(Well, he has a crush on Idia, that much he knows, so he guesses that’s something to be expected, in a way? He’s heard his classmates talking about the being unable to get enough related to someone so it was just part of it, probably. What they have now is good, straight out of his dreams even! Just… feelings are weird, aren’t they? He keeps wanting more, though he doesn’t know exactly what would sate this hunger.)

“Oh, I did rubber on the top and some of that light metal for the parts. I thought it’d be better if we don’t make it too heavy!” Kero replies, digging around for his own lab gear he’d brought. They might have to do some welding today, so it was always good to be careful.

(Plus, they got to match outftits!)

Idia nods, focused gaze on a miniature engine. “Ohh… huh. That’s good, actually. I think this might be easier than I thought.” He mutters. “We have all the parts to build the interior of the factory… I guess we could put that together tonight, and tomorrow we can get the rest? For the outside, I guess. If we just focus on the factory instead of the, uh, social repercussions or something like that, Trein might deduct points.”

He feels his ears deflate just a little at the teacher’s mention. “Tell me about it.” Idia passes him the engine, a silent command for him to get to work linking it with the other right parts. “Do you want me to get the stuff for the scenery from the store?”

“Yeah, sure. Would be helpful.”

Kero smiles at him, and for a single silent moment they’re putting the machine parts together. Engines and gears and a seemingly endless stretch of conveyor belts, wires and such hidden on the inferior part of the styrofoam slab the mockup was being built on.

“...hey, is that the battery?”

“Yup! Just gotta charge with magic whenever you wanna see it working.”

Idia turns it around on his hands, looking at it from every angle, making a humming noise to himself…

Huh, Kero is suddenly very aware that they’re all alone in that laboratory.

Maybe it’s because of how Idia looks at the small object, or how he touches it with this utmost care one wouldn’t think he has. It’s weirdly easy for other people to assume Idia was lazy, Kero recalls, and it was something he never really understood. He was such a diligent person, actually, but people couldn’t see it right because he didn’t put effort into things people commonly worked hard in. That makes him feel sort of bitter inside, he thinks, but also proud in a way.

He’s the only one who knows Idia this closely, it comes into Kero’s mind, and a smile sprawls across his face.

“...w-what? Why are you looking at me like that?” Of course, Idia notices. The pinkish glow on his face before turns into something more like strawberry red, and… agh, what the hell, Kero’s smile gets bigger.

“It’s ‘cause you’re so cute, of course!” He says without missing a beat. How many times has he called Idia cute now? Far too many to count. But he can’t stop, and it never feels like enough to show just how god damn adorable Idia was to him. It was such a crazy feeling, really.

“Gh… and you’re e-embarrassing, as always.” Idia responds as he averts his eyes. “We’ve gotta finish this as soon as possible, y’know, now’s not the time for...t-this.”

“What do you mean with this?” Kero asks amidst a laugh. Idia looks at him with this cranky sort of expression and his heart feels like it’s about to take off and fly, wow. “You asked me a question and I answered it!”

“Yeah, you answered it while being a jerk.” Idia mumbles, getting back to unscrewing something. Kero doesn’t get what he mean with it exactly but, well, he always says stuff like this.

“I mean it, though! I think you’re really cute.” He says, it’s so easy to say things like that, they end up just coming out on their own, even when he’s trying to put his brain cells back into work like Idia wants him to. “I tell you that all the time! D’you not think you’re cute?”

Idia glances at him with wide eyes. “I...n-no? What in the Lord of the Underworld makes you think I’m c-cute?” He asks, voice almost an octave higher.

Something about this strucks Kero differently. Is that a rhetorical question? It doesn’t matter. He wants to answer.

“Well, do you want me to tell you?” He suggests, and his heart is racing. It takes just a little bit of effort to ask something like this, it’s not quite having to hype himself up for it, but… well. What’s with this mood anyways? Idia’s hands are on his flushed cheeks, gloved fingers ready to cover up his eyes, like he usually does when he’s flustered — And here’s something to add to the list already, wow.

“I-I, um.”

“If you don’t say no I’m gonna tell you.” He looks straight into Idia’s eyes… such a nice shade of yellow, an amber-gold. Kero doesn’t always mean to tease, but now he does. He has a strong impulse to do it, a determination like he’s rushing towards the finish line in track — What sort of face would Idia show him if he told him everything? “Three, two, one…you lost your chance to say no! I’m gonna tell you.”

Idia squeaks like he got jumpscared, but he doesn’t object to any of it. Kero’s excited — He takes a step closer, and takes it upon himself to touch Idia’s hair again, because he absolutely couldn’t get enough of how it didn’t burn him.

“First of all, I know you hate it since it sticks out so much, but your hair is really cute.” He says, tucking a lock of hair behind Idia’s ear, feeling him shrink and tense under the light touch — Would he do that if Kero touched him more? If he wrapped his arms around Idia’s waist and held him close? “It’s so bright and pretty, and the bangs look so nice on you, they’re kinda messy and long but in a way that’s adorable.”

Indulging himself a little further, he lets his hand ghost over Idia’s bangs, brushing them to the side and watching them fall back into place. Idia’s face is fully red now. The hair doesn’t feel like much to the touch since it’s fire, actually, but, something about it…

“Second! You have a cute smile!” Kero chimes. He’s supposed to retract his hand now, but — It just stays on Idia’s cheek. And he finds that he really doesn’t want to take it off there. “When you talk about the things you like, and you get all excited about them and start grinning… it’s really cute, actually. I like it when I see you all full of energy.”

Idia’s eyes dart around. Are his hands shaking? Kero eyes at them briefly, before taking one into his — Unable to stop himself again — and the latex of his glove meets Idia’s, watched by wide amber eyes as he laces their fingers together. Shaking, indeed, but he was able to steady them.

“Third… related to that, how your hands move when you’re rambling. I stare at them a lot. That’s how much I love to see you all excited about stuff.”

His voice had fallen softer. The coldness of the laboratory seems to just fade. Kero’s heart feels…

“Fourth...” He starts, but no words come to him. He just stares at Idia’s face, his eyes, the blue tint of his lips. There’s more to say, obviously, but he can’t think of it, and he— “...can I kiss you?”

Somehow there’s no recoil time, no surprised noise on Idia’s part, and though he loves his shyness and how it shows through, he finds that he loves it even more when he’s expecting something like this, when he wants it. The shaky, uncertain nod is all he needs to give a name to that hunger he’d been feeling.

Ah, he was in love, everything be damned.

Kero doesn’t hesitate. One hand on his cheek and the other holding his, his lips meet Idia’s, his heart now soaring completely. If he looked back on it now he’d probably find it sort of awkward, Idia’s lips are chapped and the sharp teeth felt strange against each other, but none of this matters when he feels so euphoric, when Idia just melts into his kiss, eyes fluttering shut.

He doesn’t know how long it lasts. The brief pauses to breathe aren’t enough to actually do so, but neither of them seem to mind. The held hands unlace, Idia’s coming up to Kero’s neck to urge him closer, Kero’s on Idia’s waist like he’s dreamed.

When they pull away, both breathless, Kero is grinning, and Idia looks dazed, his eyes glossy, at least for a moment before he seems to realize what they’ve just done.

“O-Oh my...we.” He squeaks, freezing in Kero’s embrace. “W-We, we just…”

“Hey, it’s cool!” Kero assures, and he pulls him a bit closer, now causing a small shriek. “I love you, you know.”

“Y-You…” Idia stutters. How long would it be until he was able to string sentences together again? Kero doesn’t have an exact estimate, but, well, this was fine too. Especially as his tension drops, and he hides his warm face on Kero’s shoulder. “...you’re the worst? You’re so embarrassing I could die.”

“That’s a quick recovery, huh.”

“S-Shut up!” Idia whines, but he stays. He stays, and Kero holds him so close that his happiness feels like it’s overflowing, and the cravings from before are just slowly satisfied. “I… I, um.”

“Tell me.” A hand on the side of Idia’s face, he pulls his face upwards, making him look into his eyes again — Would he ever get enough of this, though? They’re so close. “Do you love me too, Idia?”

Idia hesitates, an embarrassed noise leaving him.

“I… I do.” He mutters — And he smiles. “You idiot.”

Kero smiles, his feelings actually overflowing in how he hugs Idia even tighter, and he laughs.

The project could be finished tomorrow, anyways.

#twst#twisted wonderland#disney twst#disney twisted wonderland#twst x oc#twst oc#idia shroud#lis writing#commissions tag

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

guide for attempting to transform ableist/oppressive language

I’ve been doing my best to avoid using language that unintentionally suggests that certain abilities are normal and universal for all people -- this language can mistakenly make people’s presence feel isolated or unacknowledged, which isn’t my intention.

I believe it is important for all people to feel as if their abilities aren’t hinderances to their personhood, only features unique to their experience. to this end I'll be doing my best to try to catch when I use language that normalizes ableism and I encourage you to do the same if you have the same concerns, not out of a sense of political correctness, but out of respect for a community of people who have historically been pushed aside as lesser individuals unworthy of our time, love and consideration.

this is not a comprehensive list. I am still unlearning my ableist habits and may still make errors, despite my best intentions. Feel free to add on or provide even more alternatives. This list is a living document.

“I stand for/with xyz.” ...can be replaced with: “I believe in/am in solidarity with xyz.”

why?

not everyone is able to “stand”. colloquially, people might be able to understand what you mean when you say this, as it often doesn’t entail actually “standing”, but it might come off as insensitive for people who can’t relate to this action but would still otherwise align with an idea or action

“I saw/see/heard/hear you/xyz” ...can be replaced with: “I understand you/xyz”

why?

this one also might be tricky. it has to do with the habit of making “hearing” and “seeing” analogous to understanding some thing or someone.

not everyone has the same ability to processes audio and visual phenomena, but they may still understand information if it is presented in another format, such as sign language or dictation or kinetics.

there are nearly infinite ways to “understand” information, but less ways to “hear” or “see” it, specifically. unless it has to do with the literal act of hearing or seeing something, and if it makes sense to substitute with “understanding”, I will avoid using it for this purpose.

[dilligence in omitting words that stigmatize people experiencing chronic mental disorders]

why?

there is no shortage of phrases used to describe people who act outside of the expected behaviors of “normal” society -- and this includes people with various mental faculties. most of the connotations for these words are overwhelmingly negative.

given how difficult it can be for people who have any number of such conditions to access certain spaces and care, the continued use of these words have historically been used to separate people into less advantaged social classes from the rest of their communities, sometimes leading to unavoidably tragic ends.

rather than stigmatize people based off these conditions, we can be more specific about the actions they’re performing or how they make us feel without employing language that has been used as a justification to harm, torture and kill others.

instead of suggesting that someone is “crazy” (for a very mild example), we can focus on what actions they’re doing and what impact they have without making assumptions about their mental state, usually with limited information and no close relationship with the individual.

we might ask: is what they are doing actually harmful to me or anyone else? is it reasonable to ignore them, if we can? what information about them do we have access to? do they need help? can I, or are there any others that could help them? what would de-escalate the situation?

[diligence in omitting any slurs or insults regarding intelligence]

why?

“intelligence” as defined by scientists, the state, private organizations and institutions under capitalism is not exempt from influence. how we come to understand and acknowledge the intelligence of other beings is absolutely affected by politics and immoral hierarchies of race, gender, skin tone, anatomical features, physical and mental ability and species. given this history, to insult someone based of their assumed relationships to knowledge often aren’t fair criticisms to lobby against someone.

what we may really mean when we call someone any of these insults directed at their intelligence, is instead that they are bigots, ignorant, inconsistent, boring, selfish, liars, rude, violent, racist, ableist, transphobic, hateful, obnoxious, unwelcome, or simply awkward.

we must take care not to associate “low intelligence” with any or all of these qualities, even accidentally. people with mental disabilities might share with you their experiences of having their disabilities used as leverage against them in their social relationships, or used as a way to deny the aid they need. we should judge people’s actions that they choose to perform, not attack qualities about themselves that they have no control over.

[omitting speciesist language]

why?

oddly, this might be the more controversial point, given that non-human animals are often omitted from discourse about liberation and respect for marginalized individuals, which is precisely the point. humans have consistently not taken the lives of non-human animals seriously, and it has resulted in mass extinctions that threaten our ecosystem in irreversible ways, due in part to speciesism and anthropocentrism, which shows up in the language we use daily.

when we use language that suggests that non-human animals are inherently inferior, evil, unimportant, and lesser-than their human counterparts, it directly encourages animal abuse and the bigoted belief that animals are here specifically for human use as products to buy and sell under capitalism, rather than being unique individuals with their own values, bodies and communities worthy of respect and admiration, and contributors to the environment we all share.

this language is even common among people along the “left” end of the assumed political spectrum, who might call cops “pigs”, compare snitches to “rats”, cowards to “chickens” and depict their enemies as being similar to infestations of roaches, locusts, or other such insects and “pests”.

this is concerning. these words function to dehumanize the targets of their insults, transforming them into “beasts”, therefore making their lives forfeit, and justifying any violence directed at them. it also implies that the problems that they cause are not of human origin, placing the blame of failing systems and relationships on “less human” elements, as if non-humans are the ones who are responsible for the atrocities that other humans created.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Are Progressives So Illiberal?

By Victor Davis Hanson January 31, 2021

Progressives adopted identity politics and rejected class considerations because solidarity with elite minorities excuses them from concern for, or experience with, the middle classes of all races.

One common theme in the abject madness and tragedies of the past 12 months is that progressive ideology now permeates almost all of our major institutions—even as the majority of Americans resist the leftist agenda. Its reach resembles the manner in which the pre-Renaissance church had absorbed the economic, cultural, social, artistic, and political life of Europe, or perhaps how Islamic doctrine was the foundation for all public and private life under the Ottoman Sultanate—or even how all Russian institutions of the 1930s exuded tenets of Soviet Marxism.

Pan-progressivism

To be a Silicon Valley executive, a prominent Wall Street player, the head of a prestigious publishing house, a university president, a network or PBS anchor, a major Hollywood actress, a retired general or admiral on a corporate board, or a NBA superstar requires either progressive fides or careful suppression of all political affinities.

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, 98 percent of Big Tech political donations went to Democrats in 2020. Censorship and deplatforming on Twitter, Facebook, and other social media companies is decidedly one-way. When Mark Zuckerberg and others in Silicon Valley donate $500 million to help officials “get out the vote” in particular precincts, it is not to help candidates of both parties.

Google calibrates the order of its search results with a progressive, not a conservative, bent. Grandees from the Clinton or Obama Administration find sinecures in Silicon Valley, not Republicans or conservatives.

The $4-5 trillion market-capitalized Big Tech cartels, run by self-described progressives, aimed to extinguish conservative brands like Parler. Ironically, they now apply ideological force multipliers to the very strategies and tactics of 19th-century robber-baron trusts and monopolies. Poor Jack Dorsey has never been able to explain why Twitter deplatforms and cancels conservatives for the same supposed uncouthness that leftists routinely employ.

Silicon Valley apparently does not believe in either the letter or the spirit of the First Amendment. It exercises a monopoly over the public airwaves, and resists regulations and antitrust legislation of the sort that liberals once championed to break up trusts in the late 19th and early 20th century. As payback, it assumes that Democrats don’t see Big Tech in the same manner that they claim to see Big Pharma in their rants against it.

Wall Street donated markedly in favor of Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Joe Biden in their respective presidential races. Whereas conservative administrations and congressional majorities are seen as natural supporters of free-market capitalism, their Democratic opponents, not long ago, were not—and thus drew special investor attention and support from Wall Street realists.

The insurrectionist GameStop stock debacle revealed how “liberals” on Wall Street reacted when a less connected group of investors sought to do what Wall Street grandees routinely do to others: ambush and swarm a vulnerable company’s stock in unison either to buy or sell it en masse and thus to profit from predictable, artificially huge fluctuations in the price.

When small investors at Reddit drove the pedestrian GameStop price up to well over a hundred times its worth, forcing big Wall Street investment companies to lose billions of dollars, progressives on Wall Street and the business media cried foul. They compared the Reddit buyers to the mob that stormed the Capitol on January 6.

One subtext was: Why would nobodies dare question the mega-profit making monopolies of the Wall Street establishments? The point that neither the Reddit day-traders nor the hedge-fund connivers were necessarily healthy for investment was completely lost.

Surveys of “diverse” university faculty show overwhelming left-wing support, reified by asymmetrical contributions of 95-1 to Democratic candidates. The dream of Martin Luther King, Jr. to make race incidental to our characters no longer exists on campuses. Appearance is now essential. More ironic, class considerations are mostly ignored in favor of identity politics. “Equity” applies to race not class. The general education curricula is one-sided and mostly focused on deductive -studies courses, and in particular race/class/gender zealotry that is anti-Enlightenment in the sense that predetermined conclusions are established and selected evidence is assembled to prove them.

We are also currently witnessing the greatest assault on free speech and expression, and due process, in the last 70 years. And the challenges to the First and Fifth Amendments are centered on college campuses, where non-progressive speakers are disinvited, shouted down, and occasionally roughed up for their supposedly reactionary views—and by those who have little fear of punishment.

Students charged with “sexual harassment” or “assault” are routinely denied the right to face their accusers, cross examine witnesses, or bring in counterevidence. They usually find redress for their suspensions or expulsions only in the courts. What was thematic in the Duke Lacrosse fiasco and the University of Virginia sorority rape hoax was the absence of any real individual punishment for those who promulgated the myths.

Indeed in these cases many argued that false allegations in effect were not so important in comparison to bringing attention to supposedly systemic racism and sexism. In Jussie Smollett fashion, what did not happen at least drew attention to what could have happened and thus was valuable. It was as if those who did not commit any actual crime had still committed a thought crime.

Almost all media surveys of the last four years reflect a clear journalistic bias against conservatives in general. Harvard’s liberal Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy famously reported slanted coverage against Trump and his supporters among major television and news outlets at near astronomical rates, in some cases exhibiting over 90 percent negative bias during Trump’s first few months in office. Liberal editors can now be routinely fired or forced to retire from major progressives newspapers if they are not seen as sufficiently woke.

No major journalist or reporter has been reprimanded for promoting the fictional “Russian collusion” hoax—and certainly not in the manner the media has called for punishment, backlisting, and deplatforming for any who championed “stop the steal” protests over the November 2020 elections. The CNN Newsroom put their hands up and chanted “hands up, don’t shoot”—a myth surrounding the Michael Brown Ferguson shooting that was thoroughly refuted. Infamous now is the CNN reporter’s characterization of arsonist flames shooting up in the background of a BLM/Antifa riot as a “largely peaceful” demonstration. BLM, of course, has been nominated for a Nobel “Peace” Prize. After the summer rioting, one could better cite Tacitus’s Calgacus, “Where they make a desert, they call it peace”.

A George W. Bush or Donald Trump press conference was often a free-for-all, blood-in-the-water feeding frenzy. A Barack Obama or Joe Biden version devolves into banalities about pets, fashion, and food. The fusion media credo is why embarrass a progressive government and thus put millions and the planet itself at risk?

Andrew Cuomo’s policies of sending COVID-19 patients into rest homes led to thousands of unnecessary deaths. Still, the media gave him an Emmy award for his self-inflated and bombastic press conferences, many of which were little more than unhinged rants against the Trump Administration. Anthony Fauci’s initial pronouncements about the origins of the COVID-19 virus, its risks and severity, travel bans, masks, herd immunity, vaccination rollout dates—and almost everything about the pandemic—were wildly off. Yet he was canonized by the media due to his wink-and-nod assurances that he was the medical adult in the Trump Administration room.

It would be difficult for a prominently conservative actor or actress to win an Oscar these days, or to produce a major conservative-themed film. Bankable actors/directors/producers like Clint Eastwood or Mel Gibson operate as mavericks, whose films’ huge profits win them some exemption. But they came into prominence and power 30 years ago during a different age. And they will likely have no immediate successors.

Ars gratis doctrinae is the new Hollywood and it will continue until it bottoms out in financial nihilism. When such ideological spasms contort a society, the second-rate emerge most prominently as the loudest accusers of the Salem Witches—as if correct zeal can reboot careers stalled in mediocrity. Hollywood’s mediocre celebrities from Alec Baldwin to Noah Cyrus have sought attention for their careers by voicing sensational racist, homophobic, and misogynist slurs—on the correct assumption their attention-grabbing left-wing fides prevents career cancellation.

Hollywood, we learn, has been selecting some actors on the basis of lighter skin color to accommodate racist Beijing’s demands to distribute widely their films in the enormous Chinese market. Yet note well that Hollywood has recently created racial quotas for particular Oscar categories, even as it reverses its racial obsessions to punish rather than empower people of color on the prompt of Chinese paymasters.

Ditto the political warping in professional sports. Endorsements, media face time, and cultural resonance often hinge on athletes either being woke—or entirely politically somnolent. A few stars may exist as known conservatives, but again they are the rare exceptions. For most athletes, it is wisest to keep mum and either support, condone, or ignore the Black Lives Matter rituals of taking a knee, not standing for the flag, or ritually denouncing conservative politicians. Those who are offended and turn the channel can be replaced by far more new viewers in China, who appreciate such criticism directed at the proper target.

Again, what is common to all the tentacles of this progressive octopus is illiberalism. Of course, progressivism, dating back to late 19th-century advocacy for “updating” the Constitution, always smiled upon authoritarianism. It promoted the “science” of eugenics and forced race-based sterilization, and the messianic idea that enlightened elites can use the increased powers of government to manage better the personal lives of its subjects (enslaved to religious dogma or mired in ignorance), according to supposed pure reason and humanistic intent.

Many progressives professed early admiration for the supposed efficiency of Benito Mussolini’s public works programs spurred on by his Depression-era fascism, and his enlistment of a self-described expert class to implement by fiat what was necessary for “progress.”

Even contemporary progressives have voiced admiration for the communist Chinese ability to override “obstructionists” to create mass transit, high-density urban living, and solar power. Early on in the pandemic Bill Gates defended China’s conduct surrounding the COVID-19 disaster. Suggesting the virus did not originate in a “wet” market was “conspiratorial”; travel bans were “racist” and “xenophobic.” In contrast, had SARS-CoV-2 possibly escaped by accident from a Russian lab, in our hysterias we might have been on the brink of war.

So it is understandable that progressivism can end up as an enemy of the First Amendment and intellectual diversity to bulldoze impediments to needed progress. To save us, sometimes leftists must become advocates of monopolies and cartels, of censorship, or of the militarization of our capital.

The new Left sorts, rewards, and punishes people by their race. And some progressives are the most likely appeasers of a racist and authoritarian Chinese government and advocates of Trotskyizing our past through iconoclasm, erasing, renaming, and cancelling out. San Francisco’s school board recently voted to rename over 40 schools, largely due to the pressure of a few poorly educated teachers who claimed on the basis of half-baked Wikipedia research that icons such as Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Washington were unfit for such recognition.

Absolute Power for Absolute Good

There are various explanations for unprogressive progressivism. None are necessarily mutually exclusive. Much of the latest totalitarianism is simple hula-hoop groupthink, a fad, or even a wise career move. Loud progressivism has become for some professionals, an insurance policy—or perhaps a deterrent high wall to ensure the mob bypasses one for easier prey elsewhere. Were Hunter Biden and his family grifting cartel not loud liberals and connected to Joe Biden, they all might have ended up like Jack Abramoff.

More commonly, progressivism offers the elite, the rich, and the well-connected Medieval penance, a vicarious way to alleviate their transitory guilt over privilege such as a $20,000 ice cream freezer or a carbon-spewing Gulfstream by abstract self-indictment of the very system that they have mastered so well.

Progressives also believe in natural hierarchies. They see themselves as an elite certified by their degrees, their resumes, and their correct ideologies, our version of Platonic Guardians, practitioners of the “noble lie” to do us good. In its condescending modern form, the creed is devoted to expanding the administrative state, and the expert class that runs it, and revolves in and out from its government hierarchies to privileged counterparts in the corporate and academic world.

Progressivism patronizes the poor and champions them at a distance, but despises the middle class, the traditionally hated bourgeoise without the romance of the distant impoverished or the taste and culture of the rich. The venom explains the wide array of epithets that Obama, Clinton, and Biden have so casually employed—clingers, deplorables, irredeemables, dregs, ugly folk, chumps, and so on. “Occupy Wall Street” was prepped by the media as a romance. The Tea Party was derided as Klan-like. The rioters who stormed the Capitol were rightly dubbed lawbreakers; those who besieged and torched a Minneapolis federal courthouse were romanticized or contextualized.

Abstract humanitarian progressives assume that their superior intelligence and training properly should exempt them from the bothersome ramifications of their own ideologies. They promote high taxes and mock material indulgences. But some have made a science out of tax evasion and embrace the tasteful good life and its material attractions. They prefer private schooling and Ivy League education for their offspring, while opposing charter schools for others.

There is no dichotomy in insisting on more race-based admissions and yet calling a dean or provost to help leverage a now tougher admission for one’s gifted daughter. Sometimes the liberal Hollywood celebrity effort to get offspring stamped with the proper university credentials becomes felonious. Walls are retrograde but can be tastefully integrated into a gated estate. They like static class differences and likely resent the middle class for its supposedly grasping effort to become rich—like themselves.

The working classes can always make solar panels, the billionaire John Kerry tells those thousands whom his boss had just thrown out of work by the cancellation of the Keystone XL Pipeline. It is as if the Yale man was back to the old days when the multimillionaire and promoter of higher taxes moved his yacht to avoid sales and excise taxes and lectured JC students, “You study hard, you do your homework and you make an effort to be smart, you can do well. If you don’t, you get stuck in Iraq.”

There is no such thing as “dark” money or the pernicious role of cash in warping politics when Michael Bloomberg, George Soros, and Mark Zuckerberg, both through direct donations and through various PACs and foundations—channeled nearly $1 billion to left-wing candidates, activists, and political groups throughout the 2020 campaign year.

In sum, the new tribal progressivism is the career ideology foremost of the wealthy and elite—a truth that many skeptical poor and middle-class minorities are now so often pilloried for pointing out. Progressives have adopted identity politics and rejected class considerations, largely because solidarity with elite minorities of similar tastes and politics excuses them from any concrete concern for, or experience with, the middle classes of all races. The Left finally proved right in its boilerplate warning that the “plutocracy” and the “special interests” run America: “If you can’t beat them, outdo them.”

Self-righteous progressives believe they put up with and suffer on behalf of us—and thus their irrational fury and hate for the irredeemables and conservative minorities springs from being utterly unappreciated by clueless serfs who should properly worship their betters.

https://amgreatness.com/2021/01/31/why-are-progressives-so-illiberal/

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Class and Climate Struggle: Decolonising XR

So XR Scotland just did a surprisingly awesome thing, publishing the statement On Class and Climate Struggle: Decolonising XR. I’m gonna copy paste the whole thing because it is so good that this is happening and to be honest, I would not be at all surprised if someone else at XR tried to make it disappear.

Oct 19th 2019

In the last week, two widely-shared images have summed up deep-rooted problems at the heart of the Extinction Rebellion movement. One, a white man wearing a suit jacket being pulled off the top of a Tube train by people needing to get to work. In Canning Town, a mostly working class area of London that has been hit by years of austerity.

The other, a card and a bunch of flowers sent to police officers by an XR arrestee, thanking them for their ‘professionalism’. Brixton police station, where black men have died in custody.

These scenes have shown nothing new—XR has long been criticised for failing to connect with marginalised communities. But they have shown how urgently XR needs to openly address these issues.

A core message of XR has been ‘we are all in this together’. That climate catastrophe is coming for everyone, whatever class, race or creed, we can all be united by a common cause in the face of a shared threat.

BUT:

– People in the Global South are already experiencing floods, drought, famine and unbearable heat that won’t affect the North in same way.

– They have been robbed of the resources to be resilient to climate change by the economic system that benefits the richest 1%.

– People living in poverty, in both the Global South and North, due to structural injustice (often people of colour and disabled people) are and will be adversely affected in ways the rich are protected from.

– Migration caused by impacts of climate and ecological emergency is met by hostile border policies that leave people to drown and keeps them in indefinite detention.

Yes, the crisis will come for everyone. But there are massively unjust ways this is damaging some people more than others. And when we erase that, when we ignore the voices of those on the frontlines and who have the most at stake, when we focus only on ‘our children’ and not the people who are dying now, we risk leaving space for eco-fascism. By refusing to name the causes of both the climate crisis and other social injustices–colonialism and capitalism—XR will continue to alienate the people who are already living at the sharp end of the system that is ultimately killing us all.

In the run-up to the October International Rebellion, members of XR Scotland chose to highlight these issues, and to respond to the concerns of women of colour in our group being dismissed by key figures in XR UK, by creating banners reading ‘DECOLONISE XR’ and ‘CLIMATE STRUGGLE = CLASS STRUGGLE’. Many people, and other groups in XR such as Extinction Rebellion Youth, Global Justice Rebellion and XR Internationalist Solidarity Network, applauded these banners. Others in XR UK questioned this ‘messaging’.

At last week’s roadblock action targeted at the Government Oil and Gas conference, protestors from groups other than XR Scotland began singing the chant ‘police, we love you, we’re doing this for your children too’.

A woman who was with the XR protest started to shout: ‘Say that to Stephen Lawrence and Mark Duggan’s family; say you love the police to the people of Tottenham. Say that to my friends whose lives are ruined by this system. Listen, if the people on that road were all people of colour they would be getting charged at with riot gear. My black and brown friends get stopped and searched EVERY DAY’. Other XR members told her off for raising her voice and talking about something that was ‘unrelated’.

While some Scottish rebels went around asking people individually not to sing that chant, another XRS rebel—a young woman of colour—took the megaphone to ask ‘please don’t sing that—it’s really alienating to people from marginalised communities’. A middle-aged white woman then took the megaphone away from her, to say that she does love the police, that she is doing this for their children, and her own children. A woman of colour’s critique was very literally silenced by the concerns of the white woman.

Narrating this incident is not to individually blame that white woman—her actions were a symptom of something systemic in both XR and wider society. But what it reminds the white, middle-class people that dominate our movement is to stop taking the megaphone. To be quiet, and listen.

After listening, what comes next is more difficult. How can XR use its resources in genuine solidarity? How do we shift from being an overwhelmingly white and middle-class movement to centring those who have been excluded? And without tokenism, or requiring disabled, working class and people of colour to do the work that those with more privilege should have done long ago? But taking the time to listen, absorb, and reflect, is the essential first step.

Recommended recent critiques of XR:

– Athian Akec, ‘When I look at Extinction Rebellion, all I see is white faces. That has to change’ https://www.huckmag.com/…/you-cant-have-true-climate-justi…/

– Minnie Rahman, ‘You can’t have climate justice without migrant justice’ https://www.theguardian.com/…/extinction-rebellion-white-fa…

– James Poulter ‘Extinction Rebellion’s Tube Protest Isn’t the Last of Its Problems’ (including interview with XR Scotland’s Mikaela Loach) https://www.vice.com/…/extinction-rebellion-tube-disruption…

– May Fraser, ‘The Police Line’, https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2019/10/16/the-police-line/

– Kevin Blowe, ‘It’s Not Just a Bunch of Flowers’ https://medium.com/…/it-is-not-just-a-bunch-of-flowers-bc50…

– Hannah Dines, ‘The climate revolution must be accessible – this fight belongs to disabled people too’ https://www.theguardian.com/…/climate-revolution-disabled-p…

– Kuba Shand-Baptiste, ‘Extinction Rebellion’s hapless stance on class and race is a depressing block to its climate goal’ https://www.independent.co.uk/…/extinction-rebellion-climat…

– Bae Sharam ‘What are you doing to dismantle your middle class white privilege when participating in XR protests? https://medium.com/…/what-are-you-doing-to-dismantle-your-m…

– Karen Bell, ‘A working-class green movement is out there but not getting the credit it deserves’ https://www.theguardian.com/…/a-working-class-green-movemen…

– Sharlene Gandhi, ‘Extinction Rebellion need to focus on the fact that climate displacement will largely impact communities of colour’ http://gal-dem.com/extinction-rebellion-need-to-focus-on-t…/

– Aranyo Aarjan, ‘It’s time to add global justice to XR’s demands’ https://www.redpepper.org.uk/xr-global-justice/

– Damien Gayle, ‘Does Extinction Rebellion Have a Race Problem?’ https://www.theguardian.com/…/extinction-rebellion-race-cli…

– Wretched of the Earth Collective, ‘Our House Has Been on Fire for Over 500 Years’ https://worldat1c.org/our-house-has-been-on-fire-for-over-5…

210 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eve’s Bayou (1997), dir. Kasi Lemmons

The 1990’s saw a transition in African American filmmaking when Black Female Directors started to emerge in the industry. One Director in particular, Kasi Lemmons, rose to critical acclaim with her directorial debut Eve’s Bayou (1997) which met to extremely positive reviews and remains an important and influential text concerning themes of race and black feminist ideologies.

When examining feminist texts within African American Cinema, it is crucial to study the representations of Black Womanhood throughout the history of Black filmmaking, especially texts derived from female directors. Early representations portray the black female through the use of stereotypes (discussed previously) in the form of the Mammy, the Mulatto, the Jezebel or Sapphire. The black female identity is often linked to the body, presented as exotically intriguing or erotic; she is hyper-sexualised which contrasts the more passive white female character. Kasi Lemmons’s Eve’s Bayou manages to connect these ideologies of Black Womanhood, while simultaneously subverting them to approach such concepts on a feminist level, discussing the mistreatment and misrepresentations of Black Womanhood on the big screen.

Born February 24, 1961 in St. Louis, Missouri US, Kasi Lemmons made her acting debut in television movie 11th victim (1979). She went on to star in Hollywood hits such as Spike Lee’s School Daze (1988) and Academy Award winning The Silence of the Lambs(1991). In 1997, she emerged in the industry when she wrote and directed her first feature length film Eve’s Bayou, starring renowned actor Samuel L. Jackson and upcoming actresses Jurnee Smollett-Bell and Meagan Good. Eve’s Bayou centralised on Black family life, narrated through the main character Eve, the youngest daughter of the Batiste family. Bayou delivers themes of adultery, sensual eroticism, supernaturalism and witch craft, all of which are tied together in black ancestry and history; depicting the more social and family oriented problems faced by middle class Blacks, situated in 1960’s Louisiana.

Eve’s Bayou

Lemmons’s opening party scene immediately sets up an idealised Black middle class life and emphasises the centrality of Bayou’s female led cast. Matty Mereaux is dancing with her husband Lenny Mereaux, close up shots of him groping her buttocks are shown; her body parts are immediately fetishized. Moments later she dances seductively with Roz’s husband Louis Batiste; she pulls up her dress to reveal her stockings and places her head around Louis’s groin area. This sultry depiction of Matty’s character becomes problematic when applying Laura Mulvey’s work: Visual and Other Pleasures of ‘The Male Gaze’ to the text. Here, Matty is seemingly objectified by the male viewer to be offered as none other than a placement of sexual desire for the male viewer. However, Bell hooks, a pioneer of her work on Black spectatorship, in particular Black female spectatorship, challenges and attempts to deconstruct Mulvey’s theory of ‘the gaze’ stating Black audiences can “both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see”. Black female spectators have thus since been able to adopt anoppositional gaze, placing white womanhood in the eye of the phallocentric gaze, enabling them to not “identify with either the victim or the perpetrator” (hooks, 1992)

Not only does this opening scene construct themes of erotica and woman as objectified beings. Lemmons’s overall set up, choreography and mise-en-scene is a huge movement away from previous African American depictions, seen in early 20th century texts. Here, the Batiste family, are portrayed as a well-mannered, well-spoken middle class family, with lavish clothing and a large country home. A huge contrast to the savage and uncivilised representations of tribal African Americans portrayed in early Black Cinema. As the majority of the cast is formed of Black actors and actresses, this idyllic family unit provides the ability for white audiences to identify more closely with Lemmons’s characters.

“the representation of the more perfect, more complete, more powerful ideal ego of the male hero stands in stark opposition to the distorted image of the passive and powerless female character”

Laura Mulvey, 1975/1989, p. 354

Mulvey theorises that male characters play a dominant, powerful role within the narration, while the female characters must submit to a more passive, powerless position in cinema. Mulvey argues that the audience adopt ‘the gaze’ as we constantly view texts through the dominated male lens of the industry, although “the power of the gaze is not invested in all men, but in White men, and the object of the gaze is not all women, but White women” (Hollinger, 2012, p. 194).

Roz comforts her three children after Mozelle’s vision of a child being hit

One way Lemmons subverts this idea is to centralise her female characters. Eve, the youngest daughter of the Batiste family and her adolescent sister Cicely play a vital role in the progression of the narrative and it is they who hold the power over there adulterous Father Louis. Alongside their Mother Roz and Aunt Mozelle, together provide a primary example of female solidarity. Mother Roz is shown to empower the family unit, unlike Louis, whose Fatherly absence only heightens Roz’s empowered status. hooks states that “once black folk had gained greater access to jobs, revolutionary feminism was dismissed by mainstream reformist feminism when women, primarily well-educated white women with class privilege, began to achieve equal access to class power with their male counterparts” (2000, p. 101). Black women and black feminist ideologies were pushed aside once White females started to benefit from feminist movements – “working class white females were more visible than black females of all class in feminist movement”. However Black women were the voice of experience, “they knew what it was like to move from the bottom up” (hooks, 2000, pp. 103-104).

White women primarily benefited economically from the reformist feminist gains in the workforce, “it simply reaffirmed that feminism was a white woman thing”

bell hooks, 2000, p. 107

Although she is subject to notions of patriarchy, (she stays home while Louis works to keep their home) this is quickly dismissed by the audience due to Louis’s controversial actions of adultery against his wife. His affair with Matty (stereotyped as the Jezebel) interwoven in the plot, highlights mistreated stereotypes of Black Woman.

Cicely is slapped by her Father after she attempt to kiss him

Although these women initially appear empowered in Bayou,it is needless to say that Lemmons still intersects themes and ideas already imposed on black women in film. Firstly Eve adopts the role of the maid, who does the family chores and cleans the house; several of her costumes reflect this and she is even seen with a feather duster cleaning. Alongside this, Matty is presented as the whore, who endeavours in a relationship with Louis. Despite the period setting, for such a contemporary text, these representations still manage to surface in contemporary Black Cinema as a constant reminder of the painful history of Black colonisation and slavery in early 20th century America. Another character devise that Lemmons utilises to explore Black history and the mistreatment of female slaves is through character Cicely, who we believe is abused by her Father. It is not until the end of the film that we are told it is her who instigated an incestuous relationship with her Father. “The elusive qualities of truth are given attention in the film… Lemmons provides two sequences of the same event, each bearing the narration by a different character… both Eve and the audience have to deal with two versions of a truth that each character professes” (Donalson, 2003, p. 190) From her actions, she is muted throughout the film; powerless and unable to reveal what really happened. Cicely’s powerless state can be seen as symbolic of the mass rape that occurred on plantations to multiple slaves across America. In narrative form, this becomes complex due to Cicely’s initial confession and the film’s final twist. Either way, the audience is still partial to the implied rape of an adolescent by her Father. The final shot we see of her as she leaves the Batiste family home is her signalling to Eve to keep quiet. This can be seen to parallel the voiceless African American Slaves, especially the abused woman who could not fight for their rights as slaves, let alone their civil rights amongst a prominent patriarchal society.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

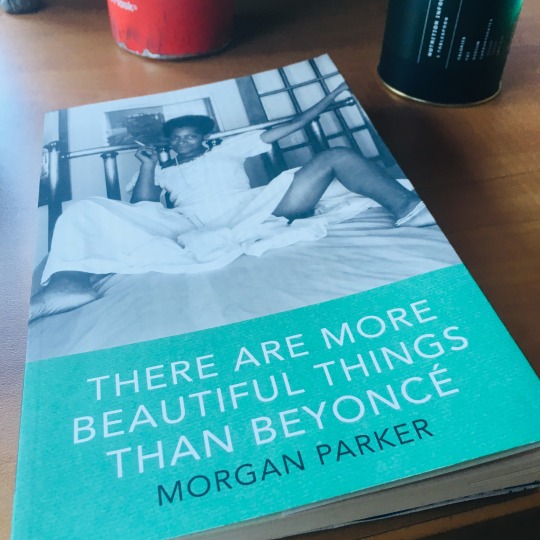

“There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé” by Morgan Parker

This book had been years coming in my collection. Its name rang out inside me when I felt its titular sentiment — that the popular worship of Beyoncé is overblown — and whenever I thought of it, I felt a spark of solidarity.

Of course, this is not a book about Beyoncé — and in fact, this is not even a book that is very critical of Beyoncé. Instead, Beyoncé acts as a literary device throughout — a mouthpiece, an amulet, a proto-idea that shapeshifts to meet Parker’s endless need to talk, sing and moan about race, class, democracy, depression, music and drugs. It’s a brilliant move.

I’d like to start more broadly by commenting on Morgan Parker, because she strikes me as an outsider among insiders. In my head, Parker is of the generation of contemporary poets that includes Danez Smith, Franny Choi, Ocean Vuong etc. … she’s decorated with a Pushcart, she co-curates a reading series, she performs with Angel Nafis as part of The Other Black Girl Collective. Her poetic career is bedazzlingly active — so why don’t we talk about her more?

By which I mean: there seems to be a kind of halo around young poets like Ocean Vuong, who — and I say this with admittedly limited experience of his work — turn the harrowing vine-tangle of identity into a kind of rhapsodic experience: a thing worth looking at because it is beautiful. (Here is an example, from Vuong’s “Tell Me Something Good”:

Snow on your lips like a salted

cut, you leap between your deaths, black as a god’s

periods. Your arms cleaving little wounds

in the wind. You are something made… )

There’s no arguing that Vuong’s poem is beautiful; my issue is with how the beauty is used. Vuong’s poem here seems an extension of the (frankly depressing and oppressive) idea that “foreigners” can make their stories worthy through pathos, pity and craft — i.e., hard work and relatability. If the sentiment sounds familiar, just tune into the way mainstream conservatives these days talk about immigrants: I don’t have a problem with immigrants writ large, I just prefer immigrants who work hard, keep their heads down, are pleasant to my children, are generally agreeable…

Anyway, it’s not fair for me to pass such a blanket judgement over Ocean Vuong’s work, and that’s for another review. But insofar as Morgan Parker is concerned, she parses the work and space of otherness in an entirely different manner. Similar to Claudia Rankine of Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, her argument is this: I won’t “fix” myself for you. I won’t try to make myself beautiful. I will tell the (magical, insatiable) truth as it is, and you will have to try to keep up. Because I am too tired to bow down, to construct something for you, to micro-manage. Parker’s poems are for haters of micro-management; they offer big gestures in small bottles.

Consider the opening lines of the opening poem, “All They Want Is My Money My Pussy My Blood”:

I am free with the following conditions.

Give it up gimme gimme.

Okay so I’m Black in America right and I walk into a bar.

With this bold opening, Parker’s commitments are clear: she will demand things of the reader (“give it up gimme gimme”) and she will clearly demarcate what commands her attention and respect (“I’m Black in America right”). And with this begins what I can only describe as a chimeric collection, more warm-blooded fantasy animal than diorama; more occult message written in glitter than typeset monolith. She scrounges from jazz, RnB and pop to fill her pauses. She is unrelentingly new instead of subtle. I like it:

I am a dreamer

with empty hands and

I like the chill.

I will not be attending the party

tonight, because I am

microwaving multiple Lean Cuisines

and watching Wife Swap…

(“Another Another Autumn in New York”)

—and the sincerity of her materials shine through. (To continue this silly dogfight I’ve set up, compare the above with Vuong: “Air of whiskey and crushed / Oreos.” Parker’s allusion to pop culture delights; Vuong’s seems like an add-on, a sprinkling of something inappropriate on top).

But wherefore is the source of all this magic? I would say in what Sun Ra called “liquidity.” For example: Parker was best when R and I read her aloud on a grassy slope on Belle Isle in Detroit. There we were, in a historically Black city, in what I can only describe as a “public paradise.” Ducks waddled by and folks of all stripes strolled in front of us beside a small man-made lake. As we read Parker aloud, we laughed with her and from within her work — as though her words gave us the ability to access our inner performers, delivering punchlines (“I don’t know / when I got so punk rock”) and casting personal spells (“I breathe / dried honeysuckle / and hope”). We felt for her. And we wanted to continue feeling for her. All things told I had a moment of genuine orality with her work — a glimpse of what poetry must have felt like when it was shared, sung and social by default. This is a book that radiates the energy of the collective, that asks you to recognize it — and does not over-demonstrate.

So, in this false dichotomy, one might pose:

LIQUIDITY: ORALITY, SOCIALITY, LONG STANZAS SHORT LINES

against

SOLIDITY: WRITTEN, INWARDNESS, SMALL FORMAL STANZAS LONG LINES

In the former, you have the world of most popular songs, particularly jazz; in the latter, you have sculpture and “high art.” Perhaps this is why Ocean Vuong’s work has garnered him endless praise and attention, and most of us look askance at Morgan Parker’s messiness, silliness and genuine emotional bravery. She rambles, yes, but her rambling challenges the very idea of boundaries — of “discipline” as a set of limits, of borders we set for ourselves, however beautiful.

Finally, I will say this, as it’s becoming a theme in my reviews. Parker’s poetry feels affectively liberated. She is funny as well as ashamed. Take, for instance, this amazing section of “RoboBeyoncé”:

The reason I was built

is to outlast some terribly

feminine sickness

that is delivered

to the blood through kale

salad and pity and men

with straight-haired girlfriends

[…]

Nothing aches in here

It’s a quiet, calculated shame