#1819 parry expedition

Text

so as some might know and some might not, JCR probably did not actually wear a dress for that antarctic New Year's ball.

the reference to him wearing a dress is afaik only in Palin's Erebus and was most likely based on Palin reading William Cunningham's diary, (EDIT: it is in fact John Davis' letter home! but do read WC's diary anyway; it's fun), where he refers to "Miss Ross" and Crozier opening the ball, and knowing that Ross had worn drag before during winter theatre performances with Parry, Palin thought Davis meant that Ross wore a dress to the ball. but Ross wearing a dress was not mentioned in any diaries from the expedition, and it feels like someone would have noted that. (there is also a drawing of the ball made by Davis where it's possible that Crozier and Ross are depicted, both in coats and top hats.)

so! while this isn't 100% conclusive: most likely, no drag at the party. BUT (to make up for it),

i feel like we should talk more about the fact that the occasions when Ross did don a dress are in fact somewhat documented in print -- and we even have a (admittedly humorous and likely embellished) description of him backstage being laced into his corset:

you see, we know that Ross played Corinna in The Citizen in Parry's theatre during the 1819 expedition. and an anonymous poet wrote a poem for the expedition's newspaper called The Green-Room, or a Peep Behind the Curtain about that production, which contains the following lines:

you're welcome :)

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

25th Wednesday

Fine. Christmas Day we had preserved Meat & vegetables issued extra: Spliced the Main brace. The Captain had all the officers to Dine with him and every thing went very pleasantly Considering a Ship at Sea. I forgot to mention Divine Service.

Campbell's Notes: Preserved meat, Chiefly furnished by John Gillon and Co., preserved according to Donkin's invention. Ross, Voyage, I., p. xix. Donkin, Hall and Gamble, had been supplying the Navy with preserved meat since trials of their method of preservation were carried out in 1813. They had been used by Ross, 1818 and Parry, 1818 and 1819–20 in the Arctic, both of whom reported favourably on them. Parry states ‘The ships were completely furnished with provisions and stores for a period of two years;in addition to which, a large supply of fresh meats and soups, preserved in tin cases, by Messrs. Donkin and Gamble … was put on board.’ James Clark Ross served as a Midshipman on both these expeditions. Parry. Journal. p.iv, and Laing, The Introduction of canned food into the Royal Navy 1811–52, Mariners Mirror, 50, 1964, pp. 146–8.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the fall of 1819, William Edward Parry and his crew prepared to spend the winter in the Canadian Arctic. For this team of British explorers, the unforgiving cold and round-the-clock darkness were obstacles to be overcome in their search for the Northwest Passage. Looking out across the flat, treeless expanse of ice and fog, the barren landscape must have seemed wholly inhospitable. “It was a novelty to us,” he later wrote in the account of the expedition, “to see any living animal in this desolate spot.”

From Parry’s accounts, and those of other travelers, scientists built a picture of the polar night as a period of Arctic dormancy, an extended slumber in the endless twilight—when all but the hardiest of life either fled for warmer climes, or hunkered down to wait for the Sun to return. But now, researchers are discovering that the explorers had it all wrong.

A pair of new papers describing the latest discoveries reveals that the Arctic night is far from desolate: it’s alive with activity. It’s a time when microbes and animals feed, grow, and reproduce in the polar ocean, with special adaptations allowing them to thrive in the dark.

Many Arctic creatures have evolved to make use of light that is invisible to the human eye. Meanwhile, “an astonishing number” have developed bioluminescence, says Jørgen Berge, lead author of both new studies. Others live by moonlight, or by the soft red and green glow of the aurora borealis.

Berge, a marine biologist with UiT The Arctic University of Norway, is no stranger to life above the Arctic Circle. Berge has spent 13 years studying zooplankton in Svalbard, a group of mountainous, ice-covered islands far off the northern coast of Norway. Yet while cruising around a fjord in January 2012, he leaned over the side of his small boat, peered into the water, and saw something new.

“I saw a fantastic cosmos of blue-green light in the middle of the fjord,” Berge says. “That’s when I decided we needed to study the polar night.”

Berge and his colleagues have since discovered algae that grow without normal sunlight, and zooplankton that maintain their circadian cycles even without the Sun’s cues. And with these minuscule organisms forming the base of the food chain, larger organisms have adapted to prey on them.

Berge found healthy seabirds in winter with stomachs full of krill and Calanus glacialis, a fat-rich copepod that he calls the “avocado of the ocean.” How the birds located their prey in the dark remains a mystery, but he suspects that they spot the planktons’ faint bioluminescence.

Iceland scallops, meanwhile, can detect enough ambient light from the weak glow of the sun over the horizon to swim and feed on a summer-like schedule. “For me, seeing the bivalves grow through the polar night was the most surprising,” says biologist William G. Ambrose, Jr., a coauthor of the Current Biology study.

Life in the polar night is “far more active than we ever thought,” says Carin Ashjian, an oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, who was not involved with the new papers. “This is a paradigm shift.”

Now, researchers are working to determine if the burgeoning life they see is common across the Arctic, or if it’s an abundance particular to Svalbard. Then, they’ll need to figure out the whys and hows. “It appears you can’t understand the system fully by just focusing on the period of time when the Sun is up,” Ambrose says wryly.

But the rapid onset of polar warming, driven by anthropogenic climate change, means that the time for discovery may be running out. “We need to first understand the processes currently occurring. We call this the baseline,” says Kim S. Last, who worked on both of the new papers. “Without a baseline we have no way of assessing change in the biological system.”

Like the old explorers, scientists still have much to learn about what goes on when the Sun goes down.

“We have lifted the curtain on the darkness,” Berge says, “and now we’re watching the active players on stage.”

#science#ecology#biology#marine biology#zoology#ornithology#meteorology#arctic circle#norway#svalbard#arctic ref

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

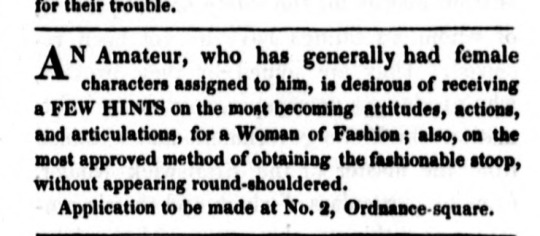

HMS Hecla in Baffin Bay, illustration from Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Performed in the Years, 1819-20 in His Majesty’s Ships Hecla and Griper, by Lieutenant Frederick William Beechey ( 1796-1856)

#naval art#hms hecla#beechey#captsin parry's first arctic expedition#looking for the northwest passage#1819-20#age of sail

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Terror Trivia: Episode 2

The second part of my series of “pop-up” trivia posts for first-time (and repeat) watchers of The Terror S1. Here’s your guide to “Gore” !

(I’m using the timestamps on my download, which may not line up to other versions online).

[00:57] Terror and Erebus were not originally built as steam-powered ships. They were retrofitted, per Admiralty orders, after they returned from Antarctica with engines that had been previously used to pull trains.

[01:54] The book that John Bridgens lends to Henry Peglar is the comedic novel The Vicar Of Wakefield—the only non-devotional book recovered from the remains of the expedition by searchers in the 1850s.

[03:19] Lieutenant Graham Gore had previously been to the Arctic on Captain George Back’s ill-fated expedition to Hudson Bay in 1836. Terror was severely damaged by ice and nearly sank on the way back to Britain.

[07:38] Sir John Franklin was known as a “blue-light” Captain. Such officers were forward with their religious beliefs, and were more common in the Navy from the Napoleonic wars onwards as evangelism rose in Britain as a whole.

[08:20] The seat of ease is the private toilet in a captain’s Great Cabin. The privy that the other crew members use is known as the “head.”

[11:38] “Seventeen years. Maybe it spooks them.” In 1830, 17 years previously, James Ross built this cairn during overland explorations conducted while the Victory was trapped in the ice.

[15:38] Sodomy was prohibited in the Royal Navy per the Articles of War, and theoretically was punishable by death. Lashing (whipping) was a common punishment that could be carried out on board ship.

[21:01] Sir William Edward Parry was a legendary polar explorer who lead four expeditions to the Arctic between 1819 and 1827. Crozier was on the second, third and fourth expeditions; Thomas Blanky was on the fourth; and James Clark Ross was on all four.

[30:48] The Royal Navy has a set of traditional toasts, one for each day of the week. For example, Thursday’s is “A bloody war or a sickly season,” Saturday’s is “Our wives and sweethearts,” and Wednesday’s is “Ourselves.”

[33:34] Crozier speaks Inuktitut thanks to his time spent on Parry’s second expedition wintering over at Igloolik, where the crew members were in close contact with nearby Inuit.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Terror, Géricault and a bit of Julian Barnes: a rant

Part One of ?

So you guys know how on episode 5, when Little comes back from Erebus, Captain Crozier receives him with:

"Ah, Edward! How fares the raft of the Medusa?"

(give this man a break)

And I tought:

"Oh Francis, you mean motherfucker."

And then I thought:

"Oh."

And after finishing the episode I picked up my favorite book and opened it on Chapter 5.

(It's easy to find because my copy's got an insert with a reproduction of The Raft of the Medusa, so the book sorta naturally opens right there)

Chapter 5 of A History of the world in 10 1/2 chapters, by English writer Julian Barnes, is titled "Shipwreck". The book is a collection of 10 independent stories, connected by ships. Ships as in, boats. There's also a half-chapter, which is titled "Parenthesis", but that's another story for another post. If you've read this far, you might like the book. It's like 300 pages and talks, amongst other subjects, about: human nature, reindeer, white people messing around in places where they had no business going in the first place, Chernobyl, God not caring much about mankind's plans, woodworm, and Nature not caring much about God's plans. And love.

Anyway, chapter 5 is titled "Shipwreck" and it is about the Raft of the Medusa.

Both about the shipwreck and the painting.

This one here.

I remember seeing it live for the first time and thinking: There's a surprising lack of blue in this nautical painting. The color palette is quite earthy, right? Not even the sea or the sky are a proper blue; more like... muted, greyish greens? It is beautiful. Mr Barnes tells us that the pigments used by Géricault started degrading right after the paint dried, especially the darker parts (he used bithumen for his blacks), and so the colors might have been different when it was first exhibited in Paris in 1819.

The painting was then in London from June to December 1820. So that's where Francis Crozier might have seen it, back when he was 24, a midshipman, about to embark on Parry's second Arctic expedition. It was a huge deal in London, this Scène de Naufrage, because the wreck of the Medusa had been a scandal in France. It would make sense for men of the Royal Navy to know about the case, and to visit the exhibition, maybe even to feel a bit giddy thinking something like that would never happen to one of His Majesty's ships.

The wreck of the Medusa was a huge fuck-up. We're talking Costa Concordia levels of incompetence and media attention. Two of the survivors, Savigny and Corréard (the ship's surgeon and engineer), after being denied compensation by the government, published an account of their ordeal that stirred the public opinion: Officer's incompetence, violence, mutiny, and finally cannibalism. Barnes tells us that "Corréard subsequently set up as a publisher and pamphleteer with a shop called At the Wreck of the Medusa; it became a meeting-place for political malcontents." We stan Corréard, honestly.

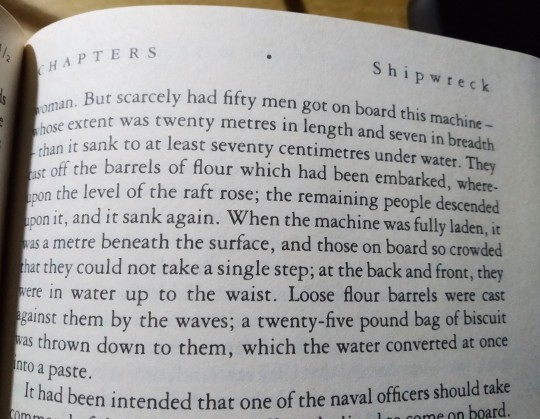

So yeah, calling Erebus (crowded at that time after most of the crew had volunteered to move there) the raft of the Medusa is very, very derogatory. Especially because the main problem of the raft, and Francis would have known it, was how overcrowded it was, at least in the beginning. Barnes tells us this:

Sailors are supertitious creatures even nowadays. During my first contract on board, I once suggested a Titanic-themed crew party for the end of an Atlantic crossing and received looks of horror in response. One of the older crew members took me aside later and explained that it was considered completely inappropriate (and a bit jinxed) to speak so lightly of a naval disaster, even 102 years (and two films) later. So yes, Francis is deliberately being an asshole, of course he's half drunk and hanging out with Blanky, the absolute king of gallows humor, but still. Edward Little (the historical one) was 5 years old when the Medusa sank off the coast of Senegal, but he'd probably known the story and got the reference. Seriously someone give Ned a hug. Anyway, Mr Hornby's dead.

(to be continued, maybe... probably)

yup! here’s part 2 and part 3

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

a primer on that handsome lad, james clark ross

here’s a bunch of stuff that i’ve learned the past year about the handomest man in the navy, sir james clark ross. we don’t know about him much, and from what we do know, it’s all in relation to the franklin expedition. so here’s a long list of trivia about the man who located the north magnetic pole, the “discoverer” of the antarctic, and francis crozier’s best friend.

feel free to use excessively (i.e. pls write him in fanfic tnx)

early life:

was born on 15th april 1800 to george and christian clark ross. his siblings were andrew clark, george clark, isabella, and marion, and two siblings who died in infancy.

his mother died in 1808 and the ross children were raised more by their uncles than their father.

career:

joined the navy at 11yo. his first ship was the hms briseis, with his uncle john ross as captain, was promoted to midshipman and master’s mate

moved with his uncle to hms actaeon then hms driver

joined john ross’s first and last navy-backed arctic expedition in 1818 (hms isabella)

joined three arctic expeditions under william edward parry (hms hecla, hms fury) from 1819 to 25, was promoted to lieutenant aged 22, then to commander aged 27. this was rather quick by navy standards. in comparison, fitzjames was dodgily promoted to commander at age 29.

joined parry’s 1827 attempt at the north pole as his second (hms hecla, endeavour)

joined john ross’s privately funded arctic expedition in 1829-33 (victory), then was promoted to captain at age 34. for reference, crozier was made captain at 44yo.

embarked on a magnetic survey of great britain from 1835 to 38

was briefly sent on a rescue mission in 1836 to save 11 trapped whalers in arctic waters (cove). he was offered a knighthood afterward but he declined.

led an exploratory voyage in 1839 to antarctica, which lasted four years (hms erebus and terror)

retired from active service at age 43 and was knighted the following year

was the first choice for the 1845 arctic expedition but declined

led an 1848 rescue attempt for the franklin expedition (hms enterprise and investigator), which was almost catastrophic and ended prematurely

was promoted to rear admiral of the red in 1856

physicality:

nearly had his spine crushed while hauling when a boat slipped and pinned him against an outcrop. jcr and the 1827 crew endured hauling boats through uneven ice, large floes, thin surfaces, slush, and rain.

broke two ribs during one of the many sledging trips he took during 1830 and still managed to walk for nine hours the following day

casually walked away from his group to survey an inlet. alone! in the arctic!!! and came back exhausted around midnight. he had travelled 50 miles that day.

spent twenty three days sledging in the area of boothia peninsula. jcr gazed out across the ice from cape felix and remarked on the heavy stream of pack ice (which will trap the franklin expedition years later).

he further sledged west and named his farthest point victory point. *dun dun*

jcr and crozier developed a hand tremour after a fierce gale hit the ships during their final retreat from the antarctic.

returned from the antarctica expedition exhausted mentally and physically

in his late 40s, jcr was described by francis mcclintock as “a very quick, penetrating old bird, very mild in appearance and rather flowery in his style. he is handsome still…and has the most piercing black eyes.”

travelled and hauled approximately 500 miles in 39 days and was in the sick list for 2-3 weeks thereafter. jcr returned from the failed rescue attempt even more exhausted.

science acumen:

natural history

collected birds, mammals, marine life, and plants during his early expeditions. jcr shot down and stuffed a gull (ross’s gull - rodostethia rosea) and later on a penguin. he also discovered a new species of bird (white-billed diver).

provided the the zoological and natural history appendices for the 1824 and 1829 voyages.

assisted joseph hooker in collecting and laying out sea plant specimens for hooker to draw

had a plethora of animals/pets onboard the ships in the antarctica expedition, including goats, rabbits, chickens, and cats.

jcr himself was “an indefatigable collector of marine animals” that he intended to analyze and describe himself. jcr spent hours up to his knees in water and elsewhere dredging.

due to the stress of later years, jcr never got to analyze his collection. it was found as rubbish in his backyard after his death. the loss is considered to have held back oceanography for thirty years or so.

magnetic observations

was allowed to take lunar observations while he was still a midshipman, something that only the most experienced officers carried out

also tested the thickness of saltwater ice, recorded temperatures, checked longitudes, and went on land excursions

!!! located the north fricking magnetic pole !!! on 1st june 1831. he wrote a paper about it titled on the position of the north magnetic pole and read it to the royal society. the paper was eventually printed.

from 1835 to 39, together with edward sabine, jcr conducted the first systematic magnetic survey of great britain. he would also assist in the 1861 ordnance survey.

chaired a committee examining the accuracy of the magnetic compasses supplied to the navy

along with crozier, was lauded as the finest scientific navigators of the age. scholars say that by 1845, crozier was second only to jcr in seamanship and magnetic observations.

scientific involvement

served as “chief scientist” in the antarctic expedition. together with his captain’s duties, this was considered arduous work.

in kerguelen islands, jcr took personal charge of the observatories with crozier, living ashore, and going back to the ships on sundays for inspection and divine service.

was criticized by hooker for not encouraging scientific learning among his officers. jcr said that he and crozier were suitably qualified to handle tasks such as magnetic calculations, water samples and astronomical readings.

he just really wanted to *clenches fist* hoard all the science.

despite that, hooker did positively remark that jcr was uncommonly involved in the scientific activities of the expedition.

recognitions

was elected to many societies; including the linnaean society, royal society, royal astronomical society, and royal geographical society

received a medal from the royal geographical society and its counterpart in paris

received an honorary doctorate of common law from oxford university

finally published his book “a voyage of discovery and research in the southern and antarctic regions during the years 1839-43″ in 1847. the four years it took was a sign of jcr’s mental sluggishness.

although the expedition itself was groundbeaking, the book fell short, and it is of the scientific community’s opinion that jcr didn’t do himself justice.

was chair of the geographical section of the british association for the advancement of science. by god’s own hand probably, jcr was present when the association received a telegram on sept 1859 with the news of the discovery of the victory point note.

seamanship and other skill sets:

arts and languages

was often cast in the female roles in parry’s arctic theatre. 👀 he played corinna in the citizen, mrs. bruin in the mayor of garrett, poll in a musical entertainment called the north-west passage; or the voyage finished, and colonel tivy in bon ton; or high life above stairs.

contributed poetry to the north georgia gazette winter chronicle, a ship’s publication during the first parry expedition in 1819. one poem attributed to him was about the beauty of the aurora.

picked up enough of the inuit language from igloolik and was able to converse with the inuit they met in boothia

like many explorers, dabbled in art and painted sceneries from his voyages

hunting

shot a polar bear which made his crew very ill, either because of overeating or the bear’s poisonous liver

also shot a musk-ox at a range of 15 yards. it didn’t die and jcr had to shoot it again from five yards away. the moment is captured in one of john ross's sketches.

was given the chance to kill a 46ft whale, which his uncle found a distasteful sight. john ross didn’t mind the supply of blubber though.

led fishing expeditions and during one haul baited 3,378 salmon in a single net. he was really out there performing jesus miracles in the arctic.

sledging

readily picked up dog sledging from the inuit, with packs and equipment being pulled by a dog team of 12 while travelers walked. he ended up overworking the dogs and killing all but two of twelve. D:

in some of these sledge journeys, he was accompanied by thomas blanky.

he did pass on the rudiments of sledging to his protege mcclintock, who would perfect the technique and revolutionize british arctic sledging.

was able to sledge and chart peel sound and most of north somerset. he opined that franklin’s ships couldn’t have passed through peel sound because of the heavy ice. but that was exactly what they did.

seamanship

with jcr’s guidance and with the ships’ reinforced hulls, erebus and terror repeatedly rammed against pack ice so they could penetrate into the antarctic circle. they were the first ships to do so.

had an uncanny knack for spotting icebergs

spotted pack ice ahead of their ships and turned erebus away sharply, ramming directly to terror. the two ships were entangled then separated, with erebus's bowsprit, foretopmast, and other spars ripped away.

with the ship in bad condition, jcr executed a complicated manoeuvre to cross a narrow gap between icebergs. the move is like a car going in reverse, braking, and then drifting so the front swings right through an alley. the gap was “not twice the breadth of the ship”.

command:

charisma

was more popular than his uncle in the 1829 expedition, and often received the crew’s complaints

an officer in cove wrote of him: “the captain is, without exception, the finest officer i have met with, the most persevering indefatigable man you can imagine. he is perfectly idolized by everyone.”

quelled a mutiny twice in his career--first in 1829, then in 1836. in 1836, the cove seamen refused to sail after they were hit by a fierce storm, but were convinced when jcr addressed them in the quarterdeck.

had a sort of falling out with the falklands’ governor richard moody. hooker described it as: “they quarrelled most grievously, so that i was often unpleasantly situated.”

administration

was considered parry’s right-hand man though still a middie. as a lieutenant, jcr was was increasingly delegated scientific and other administrative duties that were meant for the captain.

left most of erebus and terror’s fitting out and recruitment to crozier while he finished with the 1839 magnetic survey.

wanted james fitzjames as his gunnery lieutenant for the antarctica expedition but was denied by the admiralty

just can’t do the damn grocery for some reason??? in hobart, van diemen’s land, crozier was “always starved” when it was jcr’s turn to purvey for the table, so crozier always had to eat his fill at franklin’s.

was prone to secrecy. the antarctic crew often had no idea where they were headed until they got there.

lashed out at his officers over minor issues following their second failed attempt at the south pole. robert mccormick wrote: “so strong were his prejudices, and... so difficult to reason with.” one wonders how he and crozier got on during this time.

while jcr did write to his superiors to report on the antarctica expedition, he did not publish a report in the papers. this would be a misstep as the expedition had lost public interest by the time they returned.

decision-making

like crozier, jcr didn’t trust steam engines and even gave it as a half-hearted reason for him to not command the 1845 expedition.

during the franklin expedition, crozier missed jcr’s captainship and expertise. he wrote of his misgivings and said: “james, i wish you were here, i would then have no doubt as to our pursuing the proper course.”

while the enterprise and investigator were stuck in port leopold, jcr ordered that foxes be trapped and fitted with collars carrying details of the relief expedition. they were entirely in the wrong island ofc.

reputation:

in society

described by michael smith as “a charismatic, popular figure with a flair that made him one of the greatest polar explorers of all time--something that more than compensated for his streak of vanity (five portraits), arrogance and occasional sharp tongue... displayed a breezy self-assurance and a strong sense of destiny”.

described by fergus fleming as “politically astute and had the knack of making himself popular”.

was initiated as a freemason, possibly on the recommendation of felix booth

a play was staged in the shady part of hobart about jcr and crozier's first venture in the antarctic. they did not attend. the play was reviewed as “better written than acted”.

hobart liked to throw jcr and crozier parties. one in 1840 displayed flags with jcr and crozier’s heraldry, with mottos written by jane franklin.

jcr’s read: “that flag so nobly won, shall wave once more / waved by thy hand, on th’ antarctic shore”.

in return, jcr threw a huge fricking party with erebus and terror strapped together and used as dance hall and dinner area. the place was decked with mirrors, flowers, swords, and candles.

was bestowed the title of handsomest man in the navy by jane franklin. jcr remained close friends with jane and acted as her advisor following the disappearance of the franklin expedition.

became a kind of recluse in 1844, writing: “my extreme abhorrence of public dinners, of which i have seen so much, has occasioned me to entirely give up attending them”.

became more of a recluse (an alcoholic recluse, sound familiar?) when his wife died

self-worth

in his expeditions to furthest north and south, jcr carried a little red book from his sister titled the economy of human life.

was the typical entitled british explorer afaict. jcr’s reaction to france and america pursuing antarctica can be summed up as: “how dare they? antarctica belongs to britain”.

when jcr received a well-meaning letter from charles wilkes enclosed with a map of the antarctic coastline he managed to chart, jcr decidedly didn’t take the route that his rivals had taken.

later on, he would reply to wilkes and tell him that the chain of mountains he named wilkes land was a mirage and did not exist. jcr is that petty bastard and he wants you to know it.

wilkes land did absolutely exist though, just not in the precise location that wilkes charted it. what did not exist--the mountains beyond the ross ice shelf that jcr named parry mountains. he was not beyond error.

tried to plant the union jack flag on a flat site in possession island, which turned out to be a massive bed of penguin guano. jcr is said to have sworn a blue streak.

cursed roundly at his publisher when he asked why jcr’s book was so delayed and that he would have to sell at a sale-or-return arrangement

influence

recommended john franklin as the commander of the 1845 expedition, but only after crozier told him that he felt he wouldn’t be up to it. several polar veterans tried to sway jcr but he stuck to his recommendation.

was generally optimistic even when the the franklin expedition hadn’t been heard of for almost two years. his opinion was highly valued may well have influenced the admiralty’s decision to stall a rescue effort.

disagreed with richard king’s recommendation to send a small party to back’s fish river since the small party wouldn’t be able to support 100+ survivors. we now know the survivors did make for the river.

was publicly criticised by king and his uncle on his management of the 1848 franklin search. historians are divided on this.

encouraged mcclintock to accept jane franklin's offer for him to lead the fox expedition. the fox expedition would end up finding the victory point note.

personal life:

courting and marriage

met his future wife while visiting isabella and her husband. ann coulman’s parents did not approve of jcr because of their age difference (16 yrs), jcr’s profession, and jcr’s “very uncertain and hazardous views”.

jcr was undeterred and wrote to a friend that “if ann can love me sufficiently to cheer with her smile the hour of difficulty tho’ a host were to rise up against us, in the name of cupid we would destroy them.”

docked a boat opposite ann’s house and met her in secret. the stuff of novels, i tell you.

brought scientific instruments to ann’s house and taught her how to measure terrestrial magnetism

supposedly rebuffed sophia cracroft’s advances in hobart. at this time, he was already engaged to ann.

named geographical features in antarctica after his fiance (cape ann) and his future father-in-law (coulman island)

settling down

with crozier as his best man, jcr married ann shortly after he returned from antarctica in 1843, and then promised to retire from active service. they settled in eliot place, blackheath, london.

crozier stayed with them in blackheath before he left for the franklin expedition in 1845. he described blackheath as “comfortless” and “scorching” and was very glad that the rosses moved to the country.

retreated to a country estate in buckinghamshire in 1845

jcr welcomed his first child james in the autumn of 1844, his second child ann in 1846, third child thomas in 1850, and last child andrew in 1854

the rosses’ married life were described as “a more perfect state of married felicity could not be imagined…if ever an observer could affirm there were two human sympathies concentrated in one, it might have been affirmed of sir james and lady ross....”

duty calls

was offered a baronetcy, a pension, and a year’s postponement if he would agree to lead the 1845 expedition. he turned it down to honour his promise to never sail again.

he probably also turned it down because he hadn’t recovered from four years in the antarctic and had taken to drinking to cope. the drinking probably hastened his death.

athough jcr had promised that he would no longer sail, ann gave jcr her blessing to lead a rescue attempt in 1848 and find their “dear frank”. in! this! house! crozier! was! loved!!

last years

ann died in jan 1857 of pneumonia, and jcr would never recover from the loss.

after his wife’s death, jcr rewrote his will and named edward bird and charles beverley as executors to look after the children. jcr knew bird since 1821 and beverley since 1818. bird, jcr, and crozier were middies together in 1821. ToT

the will was never legally executed and jcr’s sister marion became guardian of his four children.

burned his papers before he died. this one haunts me... why did you do that, james? what did you not want found?

jcr died on 3rd april 1862 and was buried beside his wife. he was 61yo.

after the stress of antarctica, of the franklin searches and public criticism, of the deaths of parry, ann, and most likely crozier and franklin, friends said that jcr died of a broken heart.

strained relations:

testified in a panel that sabine had done more of the 1818 expedition’s magnetic readings than his uncle, calling into question his uncle’s competency, thereby cooling their relations

frequently fought with his uncle regarding the running of the 1829 expedition. one of their arguments was likened by william light/robert huish to lavas bursting from a volcano. take with a grain of salt.

jostled with his uncle for recognition for locating the north magnetic pole and commanding the expedition. the whole affair was m e s s y and the admiralty opted to let it alone and let the family settle their own squabble.

hinted that he would not allow his uncle's account of the expedition to be published if his contribution to the book would be in any way altered (some places jcr named had been rennamed, removed, or added to).

supposedly placed a public advertisement telling the public that the appendix of his uncle’s book was written by jcr but he was not being paid for it

claimed that he was even offered money to publish his own account of the expedition but refused as he didn’t want to interfere with his uncle’s intentions

was accused by his uncle of giving up too soon in 1848 and using the franklin search as a pretense to find the passage. historians have defended jcr as his crew was hit with an early onset of “debility”.

scientists would later theorize that this debility was lead poisoning. six men died during jcr’s 15-month voyage. by contrast, he only lost three men in the four years he sailed with crozier to antarctica.

while their relationship was not entirely strained, jcr’s father george ross is an enterprising character, and would probably be a cause for embarrassment. george ross applied for bankruptcy thrice in his life.

george ross was secretary of the committe to collect donations for the 1829 expedition’s rescue. george back was to attempt an overland rescue, and george ross proposed himself to lead an attempt by sea. he had no sea experience whatsoever.

bestest friend in the whole wide world:

parry days

in 1821, jcr met and became firm friends with francis rawdon moira crozier and their friendship would last the rest of (one of) their lives. jcr was one of the few people who were allowed to call crozier “frank”.

when jcr married, this privilege extended to his wife. crozier often inquired after ann in his letters away, calling her “kind dear ‘thot’”.

franklin describes them as “it is truly interesting seeing them together. the same spirit animates each.” jcr and crozier were also described as “like brothers, so attached by their mutual tastes and dangers shared together.”

found several notes from crozier in supply caches in 1827. one of these charmingly read: “i cannot explain the mingled sensations i experienced the day i parted with you at walden isle. i did not think i was so soft...god bless you my boy and send you all back safe and sound by the appointed time is the constant prayer of your old messmate.”

another note read: “we think of you sometimes, always at dinner time. how much we would give just to know whereabouts you are....”

golden years

jcr’s first command was a rescue effort to save 11 whalers trapped in the arctic circle. many arctic veterans volunteered, but he enlisted crozier as his second in cove.

cove was supposed to be escorted by two bomb class ships in case they overwintered, but plans changed and they were not sent out. the ships were jcr and crozier’s future ships--hms erebus and hms terror.

although he declined the first offer of knighthood, jcr urged for his homie’s promotion to commander. he wrote: “the zealous and efficient manner in which he has fulfilled his trying and difficult duties makes me anxious that an officer of such high reputation and who has given so many instances of distinguished merit should receive that promotion which it has been the invariable practice of the admiralty to bestow...”

endearingly referred to in hobart as “the two captains”. eleanor franklin wrote of them as “very nice people”. bless

at the hobart temporary headquarters, jcr strung his sleeping hammock right next to crozier’s (ToT)

became “comically serious and meditative” when he thought that crozier was considering leaving the antarctic expedition and staying in hobart.

named a headland in ross island as cape crozier.

celebrated new year’s day of 1842 by throwing a party in an improvised ballroom in a nearby iceberg. a throne was chiselled from the ice for jcr and crozier.

“captain crozier and miss ross” sang and danced a quadrille, and when they made their way back to the ships, they were pelted with snowballs by the crew.

it’s all downhill from here

after antarctica, a depressed crozier left london without saying farewell to jcr and ann. he wrote to them while in france: “it has caused me much pain, but the truth is i could not make up my mind to visit london now.”

recommended crozier or edward bird as franklin’s second. when the admiralty asked for his opinion on crozier’s fitness, jcr eagerly supported his friend’s appointment.

crozier reaaaallly missed jcr while he was out on the franklin expedition. in his last letter to jcr ever, crozier wrote: “how i do miss you. i cannot bear going on board erebus. sir john is very kind and would have me dining there every day if i would go... all goes smoothly but, james dear, i am sadly alone, not a soul have i in either ship that i can go and talk to... i am sadly lonely & when i look back to the last voyage i can see the cause and therefore no prospect of having a more joyous feeling.”

while the rescue ships were being fitted, jcr sent an advanced note to crozier via hms plover. he wrote: “we are settled very quietly in the country and it will be a great happiness to us to see you again at our fireside... the command of the expedition is to be in my hands & with old bird as my second i feel satisfied that we shall not be found wanting....”

ann ross also sent a note, displaying the friendship that developed in their brief acquaintance. both letters were returned undelivered.

legacy:

jcr’s coat of arms includes a dipping needle pointing north and the union jack flag flying above it with the date 1st june 1831. his heraldry also includes a fox’s head.

when the entirety of the antarctic expedition’s validated findings were finally published in 1868, six years after jcr’s death, there was little public fanfare, but it’s worth was well-known in the scientific community.

some errors in jcr’s scientific recordings were eventually found, but scientists say that considering his basic, sometimes faulty, equipment, it was a wonder he didn’t have more.

other wildlife named after jcr are flowers, a seal, and a squid.

helped esther blanky and ann reid get their widow’s pensions by testifying that ice masters were indispensable in expeditions. blanky and reid were not technically in the navy. jcr said that not granting the pensions would be “an act of injustice”.

hooker remembers jcr as “really the greatest by far of all our scientific navigators, both in point of length of service and span of the globe. justice has never been done to him.”

robert falcon scott said about jcr’s antarctic achievements: “it might be said that it was james cook who defined the antarctic region, and james ross who discovered it.”

and there it is!!! sir james clark ross is undoubtedly brilliant--even his uncle can’t contest that--but he is also far from perfect. he was a complicated man and certainly had his share of mistakes and character failings. of his grave mistakes, i can say that they were born out of lack of information, and none at all of malice or ambition like many of his contemporaries.

-- -- -- -- --

this is messy and is all in good fun so if there are any mistakes, please let me know. if you want specifics for a certain thing hmu, but i can’t promise i’ll remember the source for all of them.

in general though, i got these from: fergus fleming, michael smith, m.j. ross, owen beattie & john geiger, and of course from several posts and links provided by @tttack @indifferent-century @ltwilliammowett @handfuloftime @skazka @hangingfire

402 notes

·

View notes

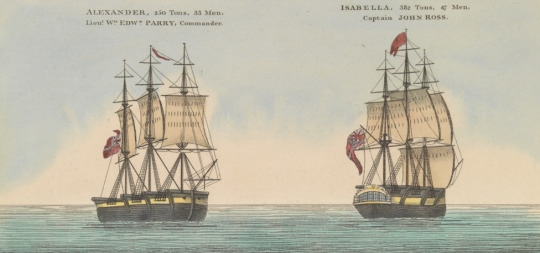

Photo

James Clark Ross’s ships

HMS Isabella (midshipman, 1818), HMS Hecla (midshipman, 1819-20; lieutenant, 1827), HMS Fury (midshipman, 1821-23; lieutenant, 1824-25), Victory (second-in-command, 1829-32), HMS Victory (supernumerary commander, 1833-34), HMS Erebus (captain, 1839-43), HMS Enterprise (captain, 1848-49)

Not pictured: HMS Briseis (first-class volunteer, midshipman, 1812-14), HMS Acteon (midshipman, 1814-15), HMS Driver (midshipman, 1815-17), HMS Cove (captain, 1835-36)

Artist information and a few notes below:

I wasn’t able to find images of Briseis, Acteon, Driver, or Cove. Though the ship plans for Driver are here and here if anyone’s interested.

Although Ross’s name was on HMS Victory’s books from 1833-34 to give him the necessary service time to be promoted to post-captain, he was on leave the entire time to assist with his uncle’s narrative of the 1829-33 Victory expedition.

Images:

James Whittle and Richard Holmes Laurie. Portrait of the Vessels on the Polar Exploration of 1818. 1818. Colored etching. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Detail. (x)

George Lyon. “The Last Appearance of the Sun for 42 Days”, in The Private Journal of Captain G.F. Lyon of HMS Hecla During the Recent Voyage of Discovery Under Captain Parry. London: John Murray, 1824.

Henry Parkyns Hoppner. Situation of H.M. Ship Fury August 25th 1825. 1826. Tinted engraving. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (x)

John Ross. “The Victory Under Sail for the Last Time”, in Narrative of a Second Journey in Search of a North-West Passage and of a Residence in the Arctic Regions During the Years 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833. London: A.W. Webster, 1835.

Edward William Cooke, H.M.S. Victory First Rate 104 Guns. Portsmouth Harbour. The Flagship of the Late Lord Nelson. On board of which he was killed off Trafalgar Oct 21st 1805. c. 1828-30. Colored etching. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (x)

Richard Brydges Beechey, HMS ���Erebus’ Passing Through the Chain of Bergs, 1842. 1860. Oil on canvas. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (x)

W.H. Brown. The Devil’s Thumb, Ships Boring and Warping in the Pack. 1850. (x)

Sources:

O’Byrne, William Richard. A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray, 1849.

House of Commons. “Report from Select Committee on the Expedition to the Arctic Seas”. London: s.n., 1834.

Ross, M.J. Polar Pioneers: John Ross and James Clark Ross. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994.

128 notes

·

View notes

Photo

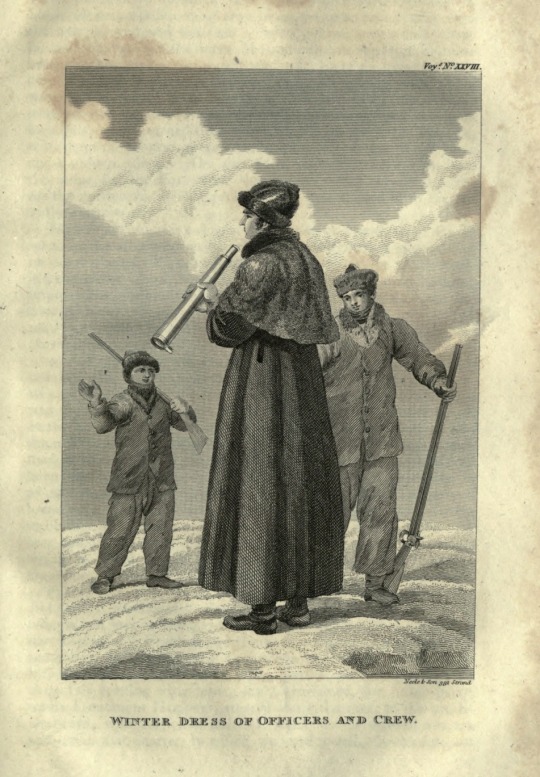

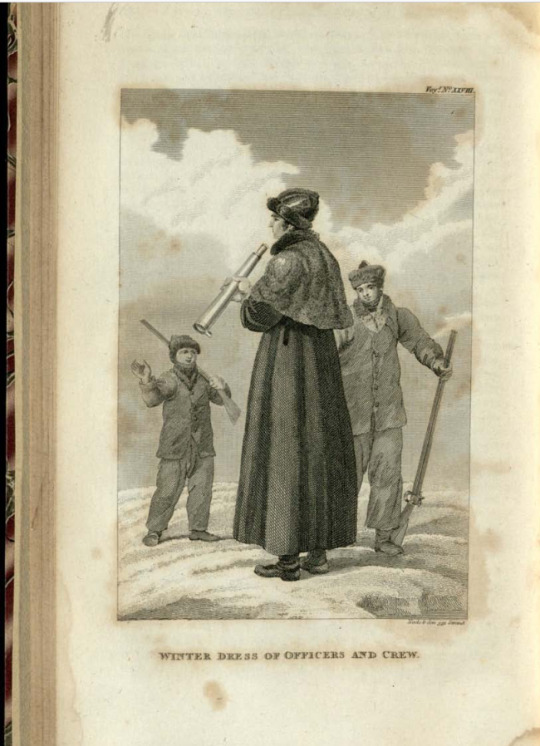

“Winter Dress of the Officers and Crew” of William Parry’s first expedition in search of a Northwest Passage, 1819-20.

Taken from “Letters Written During the Late Voyage of Discovery in the Western Arctic Sea,” by “An Officer of the Expedition” (likely Alexander Skene or William Griffith, both midshipmen on HMS Griper), 1821.

#William Edward Parry#I promised I wouldn't compare who this officer looks like...#Arctic Exploration

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (1/26/17)

Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774-1840)

The Sea of Ice [aka "The Wreck of Hope"](1824)

Oil on canvas, 96.7 x 126.9 cm.

Kunsthalle, Hamburg

This painting may be understood as a sort of programmatic statement and resume of Friedrich's aims and intentions. A source of inspiration for the painting was the polar expedition mounted by William Edward Parry from 1819 to 1820 in search of the North-west Passage. The painting's icy palette corresponds to the Arctic setting. It is undoubtedly one of the artist's masterpieces, yet the radical nature of its composition and subject was greeted in its own day with incomprehension and rejection. The picture remained unsold right up to Friedrich's death in 1840.

In the painting, now often called The Wreck of the Hope, the painter imbued the subject with unsurpassable dramatic intensity. The particular feature of this work is that the drama has already happened. The huge towering pinnacles are the slowly moving icebergs that have long become fixed here. The bold attempt by man to burst the bounds of his allotted sphere ends in death.

When the artist was 13, an accident occurred, that, perhaps subconsciously, formed part of the shadow that seemed to darken his temperament throughout his life. While ice skating he was saved from drowning by his younger brother Christoph, but Christoph himself drowned in the icy water before his eyes. It not too far-fetched to surmise that Friedrich's various "sea of ice" paintings can be seen in relation to this traumatic experience.

For more of Friedrich's work be sure to check out this MWW exhibit/gallery:

* Caspar David Friedrich & German Romanticism

0 notes

Photo

Model of a 1803 Rifle Harpers Ferry, made at the United States Armory

Most notably, the patch box on the stock is inscribed: “Taken from the Maintop of the U.S.S. PRESIDENT after her capture by H.M.S. ENDYMION, 15th January 1815 by W.N. Griffiths. Midshipman H.M.S. TENEDOS.”

Museums Catalogue entry below

USS President was the fastest of the six original American frigates. In January of 1815, USS President, commanded by Captain Stephen Decatur, encountered a British blockade while attempting to sail from New York. The British squadron, comprised of HMS Majestic, HMS Endymion, HMS Pomone, and HMS Tenedos, gave chase to the American ship. HMS Endymion, a warship specifically designed and outfitted to fight the large American frigates, engaged President first. Both ships received significant damage in the ensuing fight. Decatur, seeing that Endymion was immobilized by the exchange, chose to flee, but his ship was slowed by damage and overtaken by Pomone and Tenedos. After taking fire from Pomone, President surrendered and was taken back to England as a prize. She was too badly damaged to be refitted and was later broken up at Portsmouth, England.

William Nelson Griffiths, Esq., a midshipman in the British Royal Navy aboard Tenedos, was directly involved in the capture of President and would have been permitted to take this rifle as a personal souvenir. After retrieving the badly damaged gun, Griffiths later had it repaired with a new stock and converted it from flintlock ignition to percussion cap. George Dyer, whose name appears on the lock plate of the gun, was a gunsmith working out of Bristol, England during the early to mid-1800s. Dyer probably repaired and converted the rifle in the second quarter of the 19th century. Every part of the gun, except the stock and parts of the lock, are original 1803 Harpers Ferry. The back of the barrel was cut off to accommodate the new firing mechanism and with it went most of the Harpers Ferry markings, though the rifle still bears the armory serial number: “447”. The gun appears heavily used but well handled; the hammer, however, is cracked.

Griffiths served on a number of ships throughout his Royal Navy career. In 1815 he served on HMS Tenedos under Captain Hyde Parker as part of the British blockade of New York. He later went on to serve under Captain William Edward Parry on multiple polar expeditions between 1819 and 1823. He rose to the rank of lieutenant on November 13, 1823, and eventually reached the rank of commander before his retirement from the Navy in 1864. He died at the age of 78 in 1878.

#naval weapons#naval artifacts#war of 1812#uss president#hms tenedos#1815#captured#rifle#age of sail

141 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I finally found the picture for the question about warm winter clothing. Unfortunately, I can't find the question again. But in this picture, which comes from a stack of letters, you can see that the men were not really prepared for the Arctic. And that they had learned nothing from the encounter of John Ross and the Inuit, because they are still dressed in wool and shod with hard leather.

- Letters Written during the Late Voyage of Discovery in the Western Arctic Sea, by an Officer on HMS Griper during William Edward Parry’s successful voyage of 1819-20 , published in London by Sir Richard Phillips and Co., 1821.

Those who would like to read them can do so here - https://library.alaska.gov/hist/hist_docs/docs/asl_G_650_1819_P176.pdf

However, I would like to point out straight away that these are possibly forged letters which the editor could have written on the basis of Parry's expedition report.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Terror, Géricault and a bit of Julian Barnes: a rant

Part 2 /?

Hello, it's me again! With more random data about a certain 19th century nautical tragedy! Come for the trivia, stay for the cannibalism!

I dunno, man, I just dig these stories. Which is weird, having worked and lived at sea, but whatever. The Terror connects to a very primal part of my brain, the same part that buzzes when I read about the wreck of the Essex, the Donner Party, Scott's final expedition or the Edmund Fitzgerald. There's a theme going on here. So back to the wreck it is!

On the first part of Chapter 5 of A History of the world in 10 1/2 chapters, Julian Barnes gives us a summary of the ordeal on board the Medusa. To summarize even more:

- French frigate Medusa struck a reef off the coast of Senegal in 1816.

- Not everyone could fit into the boats, so a raft was built. 17 people decided to stay on board the half-sunk frigate, rather than brave the ocean on that construction.

- The raft was so overcrowded that it was actually underwater in the beginning. To lighten the load so it wouldn't sink completely, they had to discard most of the food brought on board, and all of their water, leaving only wine to drink. Most of their food (mainly flour and biscuits) was at some point submerged and thus ruined by the saltwater. .

So all our supplies are either spoiled or will make us prone to delirium?

- The raft was expected to be towed by the boats, but during the first day, "one by one, whether for reason or self-interest, incompetence, misfortune or seeming necessitty, all the tow-lines were cast aside", and so the raft was left adrift.

- On the second day, three men gave up and, "convinced that there was no escape from death, bade farewell to their companions and willingly embraced the sea".

- On the second night, there was not one but two mutinies on the raft. After the struggle, 60 remained on board.

- On the third day, they started eating some of the dead.

- After the third night, 12 more people had died. 11 of them were cast into the sea, but one body was kept on board, "reserved against their hunger".

- On the fourth night, yet another mutiny. After all the violence, a total of 30 survivors remained on the raft.

- On the seventh day, two soldiers were caught stealing wine from one of the remaining caskets. They were executed by throwing them to the sea.

-That left 27 survivors, only 15 of them healthy enough to survive more than a few days. Their resources were extremely limited, with less than a cask of wine for drinking, and only human flesh for food. "To put the sick on half allowance was but to kill them by degrees. And thus, after a debate in which the most dreadful despair presided, it was agreed among the fifteen healthy persons that their sick comrades must, for the common good of those who might yet survive, be cast into the sea", Barnes tells us. "The healthy were separated from the unhealthy like the clean from the unclean".

There’s been a vote, Edward

- After that, the survivors decided to cast all their arms into the sea, except one sabre, "lest some rope or wood might need cutting". Fun fact: the equipment of modern lifeboats includes not only food, water and a first aid kit, but also 1 (one) boat axe. And the reason for this is exactly the same: just in case some rope or plastic/fiberglass might need cutting .

(My face during that particular safety training)

- And then

wait for it

a white butterfly showed up.

Now of course, that would be a good sign, right? Not because it works great as a symbol on an artistic level (looking at you, Peter Jackson), but in this case it does work on a logical level: How far away can a freaking butterfly fly? It must mean that land is near, right? Just like, dunno, same way that an arctic bird, preying mainly on fish, wouldn't stray too far away from open water, so it must mean there are leads relatively nearby, right?

Right? :____(

The survivors of the Medusa did not spot land anywhere. And our Cold Boys didn't find any leads. Life is a bitch like that sometimes. Géricault could have chosen to depict this moment in his painting, but he didn't. "First, it wouldn't look like a true event, even though it was," says Barnes. As viewers, we know this. We are ready to accept a white butterfly showing up somewhere in the Misty Mountains over Khazad-dûm to save our favorite wizard, but on a real story, a real tragedy, it wouldn't work, it would be too on-the-nose. And so the butterfly and the bird both fly away, and nothing changes, and the tragedy goes on.

- On day 10, eight of the survivors of the Medusa, convinced that land must be within reach, built another, smaller raft, from pieces of the first one, upon which to escape. But as soon as they tried it, they realised it was too frail, and gave up on the plan.

- On day 13, they sighted the Argus. This is the moment that Géricault depicts, when they first spot a ship on the horizon.

See it there? Just look where all the guys are looking (well, not all of them, but more on that later)

Yep, that's a ship, that tiny little thing on the horizon, against the rosy sky (is it dawn, or dusk, by the way? What do you guys think?), not bigger than a butterfly. Pretty impressive to have the whole composition of this massive painting, and the attention of everyone depicted, gravitate away from the viewer. Literally no one in this painting gives a flying fuck about the viewer because their eyes are fixated on their only hope, a ship that looks like it might just disappear at any moment...

Which is exactly what it did.

My dudes, this painting, and the story behind it, is peak Romanticism. The drama.

The Argus was visible for about a half hour. It gave no sign of having spotted the raft. And then it disappeared.

Ok but wait a minute, so didn't they get rescued?

Well yes they did. That's how we know what happened.

The survivors watched the ship disappear, fell into despair and decided, like many of us do on one of those days, that a nap might help. So they "rigged a piece of cloth as a shelter from the sun, and lay down beneath it"

And then a couple hour later, one of them went to the front of the raft, out of the canvas, and saw the Argus half a league away (that's less than 3 km), "carrying a full press of sail, and bearing down upon them".

If this wasn’t real, we’d call it lazy writing. I mean, typical cliffhanger, our hero is gonna die, all hope is lost, finish episode there. And then next week, boom, of course the hero is saved within the first five minutes. Ugh. But life is badly written like that sometimes.

And so they were saved. Well, five of them died in the days after their rescue. Which leaves us with a total of 10 survivors from the Raft.

Géricault read the account from Savigny and Corréard sometime in the winter 1817-1818. The painting was finished in July 1819. And sometime in 1820, Captain Crozier saw it in London, while he was on leave before joining Parry on an Arctic expedition in 1821.

And this is getting long, so I'm gonna leave it here for now. Next part will be about the parallels I see between the actual painting and the show. If you made it all the way here: Thanks for reading!

(here’s part 1 and part 3 )

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

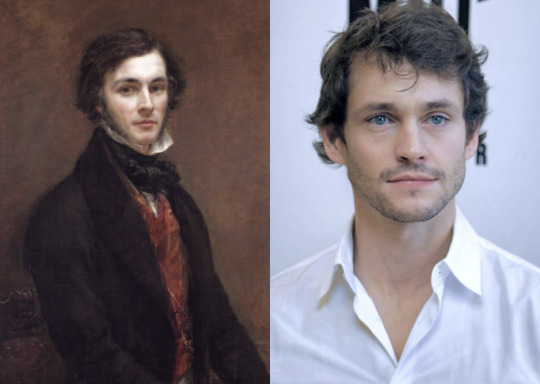

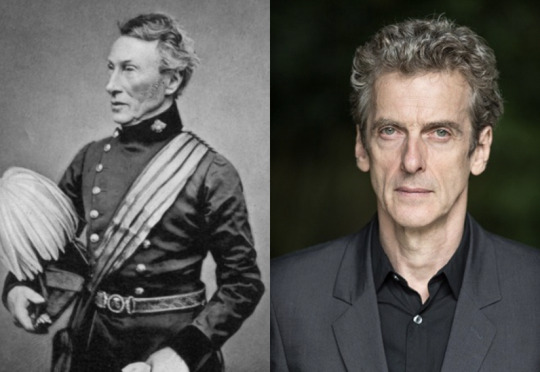

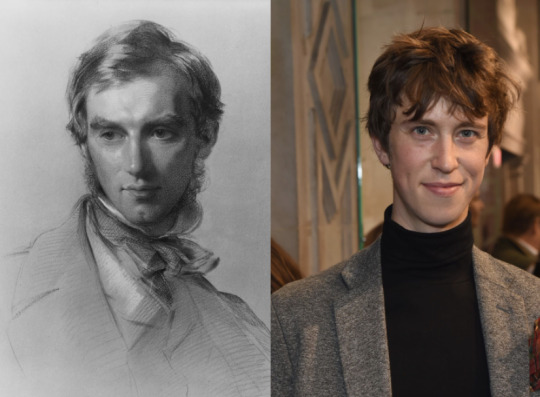

i present to you my expanded Terror Cinematic Universe (TCU) Casting

please feel free to fight me on any of these if you have better suggestions i am just a humble user of imdb dot com and longtime watcher of british television and theatre. without further ado:

Oliver Chris as Edward Charlewood, JFJ’s BFF

Hugh Dancy as Will Coningham, JFJ’s adopted brother

Aneurin Barnard as Captain William Parry (c. 1819-20 expedition)

Peter Capaldi as Captain Francis Rawdon Chesney, aka WORST BOSS EVER

Angus Imrie as Dr. Joseph Dalton Hooker

Thomasin McKenzie as Eleanor Franklin

Matthew Rhys as Dr. Robert McCormick, resident bird murderer

Simon Merrells as Lieutenant Edward Bird, aka McCormick’s arch-enemy

Eddie Marsan as Dr. John Rae, Franklin searcher who got personally #cancelled by Charles Dickens & Lady Jane

#i still need castings for philips and davis but listen i got tired someone else do it#THANKS#the terror#discovery service

211 notes

·

View notes

Photo

every day of my life i think about this letter in the parry 1819-20 expedition newspaper which is probably from james clark ross, AKA “sweet-faced midshipman who played a girl in almost every single theatrical that winter”

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

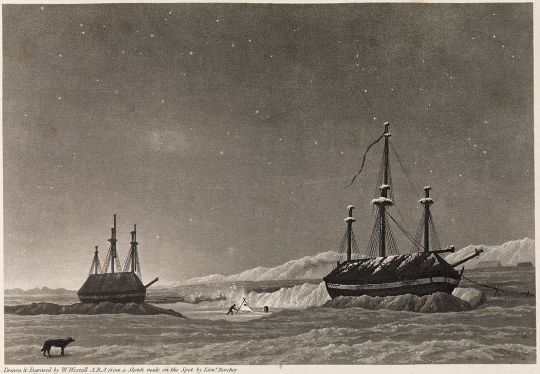

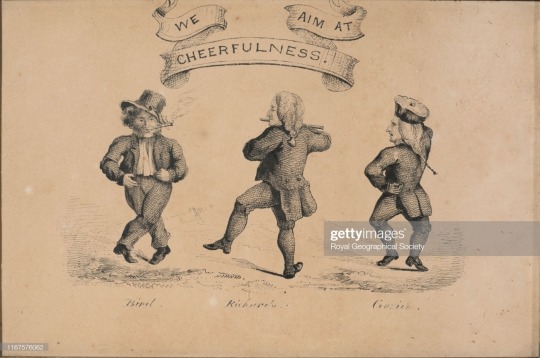

‘We aim at Cheerfulness’: Masquerades on Parry’s Third Arctic Voyage

William Edward Parry’s first two voyages in search of a Northwest Passage—with HMS Hecla and HMS Griper in 1819-20, and HMS Fury and HMS Hecla in 1821-23—confronted the question of how to occupy the long stretches of time the ships spent frozen in the Arctic ice, which could last from September or October of one year to July or August of the next. As Parry put it in his narrative of the first expedition, the “circumstances of leisure and inactivity,” especially during the long polar night, necessitated finding “some amusement for the men during this long and tedious interval”. His solution was amateur theatricals, which the expedition’s officers staged for the crew at two-week intervals. Drawing on an established naval tradition of shipboard theatricals, the plays kept the men busy constructing and disassembling the theatre, and kept morale high. A rather haphazard affair on the first expedition—the actors made costumes out of curtains and bedsheets and soon exhausted the few plays in the ships’ libraries, leading the expedition’s officers to write one themselves—became more formalized on the second, with the officers seeking out scripts and setting up a subscription for costumes before they sailed.

Overwintering in the Arctic: HMS Hecla and HMS Griper in 1819.

By the time of Parry’s ill-fated third expedition (HMS Hecla and HMS Fury, 1824-25), however, the plays’ charm had begun to wear off. While Parry likely intended to continue the tradition—Hecla sailed with a few trunks of cast-off women’s clothing, presumably intended for costumes—he noted in his official narrative that “our former amusements” were “almost worn threadbare,” and that it would require “some ingenuity to devise any plan that should possess the charm of novelty to recommend it”.

Henry Parkyns Hoppner, Fury’s captain and Parry’s second-in-command, rose to the challenge, proposing that the ships hold masquerade balls in which all members of the expedition could participate if they chose. Parry took to the idea at once; he later declared that nothing could have been “more happy, or more exactly suited to our situation”. William Mogg, Fury’s clerk, praised the idea of allowing everyone to participate, regardless of rank—in contrast to the theatricals, where the cast members were drawn solely from the expedition’s officers. The first ball—though not a masquerade—took place on Fury on October 13th 1824; Mogg described it as “numerously attended and kept up until a late hour”.

While this first ball was a success, the first masquerade ball, which was held a little over two weeks later, outshone it by far. Mogg devoted a considerable amount of space in his journal to both the ball itself and the preparations beforehand, recording the bargaining and swapping that went on as people tried to assemble their costumes:

Every one was in motion with the constant buz[z] of ‘can you oblige me with the loan of a bonnet, cap, petticoat, stays, false fronts, wigs, artificial flowers,’ with several other articles that would exhaust the catalogue of a lady’s wardrobe. Emissaries were dispatched in every direction, offering rewards for the hire of the several articles of apparel they were individually in quest of.

While the clothing intended for the abandoned plays proved to be a useful stock of costumes, Mogg speculated that many of the crew would turn to millinery over the course of the winter. Despite the limited resources, the masquerade saw a spectacular variety of costumes: “farmers, Highland Chiefs, Dandies, Jews and Infidels, Bricklayers, a recruiting Captain and party, a company of ‘jolly tars’ in tropical costume. Heroes of Trafalgar with the ‘Temeraire’ in their hats, vendors of Dutch clocks, matches, street sweepers, etc.”. Some shipmates collaborated on a set of characters: Lieutenant Sherer and two seamen from Hecla dressed up as a ballad singer and her husband and daughter, while Parry and Fury’s purser appeared as a Waterloo veteran and his wife, playing a violin and a tambourine. Mogg noted admiringly how well many of the people succeeded at staying in character throughout the evening. Dancing and singing provided most of the ball’s entertainment, with Parry and some of the other officers serving as the band. Mogg recorded in his journal that “the hilarity, harmony and the amusements went off to our great gratification with astonishing eclat”.

The announcement of the first masquerade ball, as reproduced in a printed extract of Mogg’s journal.

From November 1824 to February 1825, masquerades took place once a month, with the two ships trading off as hosts. A set of undertakers enlivened the ball on Hecla on January 3rd by spending the evening pursuing “a small ghostly figure in white robes and mask,” much to the company’s amusement. According to Mogg, “Many and repeated attempts were made to take the measure of Mr Ghost for his coffin. At length, with little ceremony they seized their sepulchral victim and conveyed him to a grave in a heap of sand on deck”. The ghost turned out to be Captain Hoppner, who took his burial in good humor and swapped out his sandy costume for that of a country squire. The ball on Fury in February, which coincided with the sun’s first appearance of the year, featured several paintings as decorations, including one of a rising sun and a polar bear with the words:

We aim at cheerfulness

While here we wait

But when released

We aim at Bear in Straits (Bhering Straits)

Mogg’s journal does not mention any masquerades after February: the end of the Arctic night meant that the crews could resume some of their other occupations.

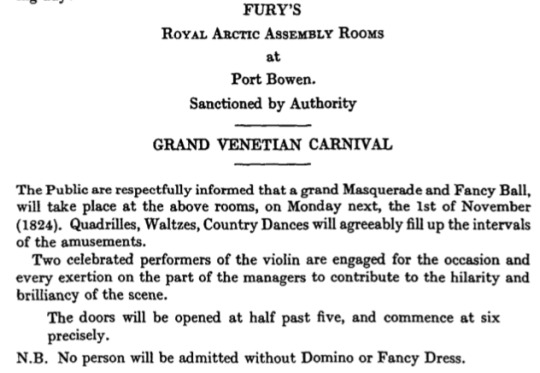

‘We aim at cheerfulness’: Midshipmen Edward Bird, Charles Richards, and F.R.M. Crozier in costume.

Looking back on New Year’s Eve at the winter months that had passed so far, Mogg concluded that the balls had been one of the winter’s most amusing sources of entertainment. Parry also praised the masquerades in his official narrative, though he spared them only a paragraph and took care to note that the men put as much effort into—and benefitted more from—the ship’s schools. With an eye to 18th-century masquerades’ reputation for degeneracy, he assured his readers that “ours were masquerades without licentiousness—carnivals without excess”. The winter of 1824-25 proved to be the expedition’s only opportunity for masquerades—the wreck of Fury in August 1825 forced the expedition to return to England without spending another winter in the Arctic—but, much like the theatricals, they would find imitators on later Arctic expeditions.

Sources:

William Mogg. “The Arctic Wintering of HMS Hecla and Fury in Prince Regent Inlet, 1824-25”. Polar Record 12, no. 76 (1964): 11-28.

Patrick B. O’Neill. “Theatre in the North: Staging Practices of the British Navy in the Canadian Arctic”. The Dalhousie Review 74, no. 3 (1994/5): 356-84.

William Edward Parry. Journal of a Third Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific. London: John Murray, 1826.

Mike Pearson. “‘No Joke in Petticoats’: British Polar Expeditions and Their Theatrical Presentations”. TDR 48, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 44-59.

Images:

William Westall, after Frederick William Beechey. H.M. Ships Hecla & Griper in Winter Harbour. 1821. Engraving. National Library of Norway.

C. Staub. “Caricature of Edward Bird, FRM Crozier and GH [sic] Richards as midshipmen on HMS Fury”. 1824-25. Ink on paper. Royal Geographical Society.

49 notes

·

View notes