#Adult ESOL Learners

Text

Empowering Success: Transformative Foundations of ESOL Teaching for Tertiary Educators in Aotearoa NZ – Part 1

xplore the foundations of ESOL teaching in this comprehensive course module. Learn about second language acquisition principles, cultural diversity, challenges, and integrating first languages. Enhance your teaching practice today.

I’m writing a series of modules on the foundations of teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL). This is long overdue as I was an ESOL teacher for many years, but it feels good to be looking at this content again with fresh eyes.

I have roughly six chunks planned which I will draft and post here like I normally do with new content:

Introduction to ESOL Teaching (this…

View On WordPress

#Adult ESOL Learners#Affective Filter Hypothesis#Challenges in ESOL Teaching#Classroom Dynamics#Classroom Integration#Critical Period Hypothesis#Cultural Diversity#Cultural Understanding#Culturally Responsive Teaching#ESOL Teaching#First Languages#Interlanguage Theory#Language Acquisition#Language Education#Language Teaching Methods#Linguistic Diversity#Opportunities in ESOL Teaching#Reflective Practice#Second Language Acquisition#teaching strategies#thisisgraeme

1 note

·

View note

Text

Guest post: "I'm a huge HUE visualiser fan" - Charlotte Godwin of Leeds City College

Charlotte Godwin, adult, community and #ESOL teacher from Leeds, is a huge HUE #visualiser fan. Here she tells us why she wouldn’t be without it. #numeracy #literacy

Written by Charlotte Godwin, Attendance and Beginners Program Manager (Adult, Community and ESOL) at Leeds City College, UK.

Pre-Entry students are basic literacy and numeracy learners – they are learning to count, add, tell the time, handle money, read and write.

The HUE HD Pro visualiser is extremely easy to use and intuitive, so I can very quickly pop something up on the smartboard to show…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

In a recent virtual classroom visit to an English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) class, Senior Museum Instructor Christina Marinelli asked students “What do you think the role of art should be today?”

“I think art plays a significant role in how we express our personal reality, beliefs and individuality. It's a form of expression that we all can appreciate even if we don't agree with each other's perspectives. It can also highlight how unique we are individually and how similar we are collectively,” said student Algenis Alcantra.

Since 2019, educators at the Brooklyn Museum have been building relationships with adult literacy providers at cultural institutions and community organizations to incorporate art in their classrooms. So far this year, the Museum has maintained ties with the Brooklyn Public Library, and created new partnerships with ESOL providers at Jacob Riis Settlement House, NYU Langone, YWCA (Flushing), and CUNY’s Language Immersion Program (CLIP).

The inclusion of the visual arts in the curriculum of English language learners has proven to be an extremely beneficial method for second language acquisition. Through the use of visual aids, students can build vocabulary through descriptive language, acquire visual literacy skills, and develop persuasive language through forming evidence-based opinions. Since art also frequently provokes an emotional reaction, students are able to activate prior knowledge and make personal connections that can allow for meaning-making and cross-cultural communication amongst participants. Several studies have shown that learning experiences that have an emotional component are more readily integrated and recalled later. Therefore, visual aids can help cement the concepts being taught, and can also be used to reinforce or supplement concepts introduced in literature, history and civics.

As educational institutions with extensive collections, museums are uniquely equipped to provide art programming that can aid the low and free cost classes that community organizations and educational institutions offer to the thousands of language learners around us. Current statistics indicate that the United States population will become increasingly more diverse with surges in immigration and shifting demographics; by engaging multilingual audiences, the Museum can effectively carry out its sentiments of inclusion and diversity and remain relevant to the communities around it through building authentic relationships.

The city’s linguistic diversity can be attributed to its large immigrant population, a longstanding NYC attribute. New York City is currently home to 3.1 million immigrants, the largest number in the city’s history. Since immigrants hail from a wide array of countries and regions, about 200 languages are spoken, with many foreign born residents turning to ESOL programs to obtain better employment opportunities, health care services, assist their children with schooling, or simply navigate the city.

According to the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, “approximately half of immigrants are Limited English Proficient (LEP), meaning that they speak English less than ‘very well.’ Nearly 61% of undocumented immigrants are LEP. Overall, 23% of all New Yorkers are LEP—regardless of status.” In addition to this, 2.2 million adults in NYC lack a high school diploma or equivalent, English language proficiency, or both.

Thus, the Brooklyn Museum aims to support adult literacy programs, students, and practitioners through engagement with original works of art to promote critical thinking and visual literacy, and to reinforce content studied by adult learners in literacy programs.

To increase language accessibility within the Museum, two new programs were launched this Spring: We Speak Art and Hablemos de Arte. The former is a program that enables English language learners to practice conversational English skills through a discussion inspired by a work of art in the collection and the latter is the Spanish language equivalent.

Instead of a lecture, participants discuss and analyze an artwork in an open forum to offer their own interpretations of the works of art in the collection. Offering programs for those of varying levels of proficiency in English and Spanish, is a way for the museum to acknowledge the cultural and linguistic diversity that is Brooklyn (and beyond). We are looking forward to continuing our work with adult literacy and ESOL providers and the many possibilities that lie ahead to advance our mission of being a community resource for all.

After closely viewing A Winter Scene in Brooklyn, students in Christina Bernardo’s ESOL class were asked to look outside their window or front door, sketch what they saw, and write a brief description. “I live near the interstate highway across the main street. This is the view outside my window every day,” wrote the student whose artwork is featured above.

Posted by Natalie Aguilar

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In #TheBrideTest, there's a fairly minor character who's an adult ESL teacher and there's a fairly minor scene where the international students have bubble tea together. It's barely a page or two in what's otherwise a Vietnamese-American romance novel, but that short scene really made me miss old times with adult English learners and think about what kind of teaching I like doing. Also pictured: my emoji fortunetelling class game, like all ESOL teachers have. #thebridetest #bridetestnovel #fiction #kissquotientseries #eslteacherlife #romancenovel #bookblogger #bookstagram #amreading #bookbloggersofinstagram #instaread #readersofinstagram #booklife https://www.instagram.com/p/CU8jZSKl5tq/?utm_medium=tumblr

#thebridetest#bridetestnovel#fiction#kissquotientseries#eslteacherlife#romancenovel#bookblogger#bookstagram#amreading#bookbloggersofinstagram#instaread#readersofinstagram#booklife

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wikispaces: Youth Services Librarianship - English Language Learners

[By the time you see this, Wikispaces will have shut down due to financial troubles. This transcription (July 2018) is my attempt to preserve professional knowledge for the youth library field, until such a time that a new, updated resource becomes available! c: ]

(Last revised: 2011-2013)

Introduction

Non-native speakers of English is a broad category that refers to a diverse group of youth services patrons. It describes youth and caregivers who are learning English, and as well as children of immigrants who speak English, but do not operate in it with the fluency of a native speaker. This latter group is sometimes labeled "Generation 1.5" because it is comprised of people who arrived to the U.S. as children, and therefore straddle a place between their first generation parents and second generation siblings. Although there are several terms to refer to non-native English speakers, this article will use ELL (English Language Learner).

Public libraries have a long history of serving ELL patrons. In addition to providing access to educational materials for English learning and citizenship exams, many also offer English classes. Though historically librarians sought to speed the "Americanization" of foreign-born patrons through education, recent efforts recognize the importance of embracing multiculturalism, and changing the library to reflect its community. These efforts include events and fairs that celebrate ELLs' cultures, bilingual storytimes, foreign language materials for children and adults, and circulation paperwork and signage translated into multiple languages.

Even if your library does not currently serve ELL patrons, it cannot hurt to be prepared, especially as demographics shift. Around 12% of the current American population is foreign-born, with over half hailing from Latin America and the Caribbean, followed by immigrants from Asia, Europe and Africa. In recent years, the foreign-born population has also become more widely disbursed; while over half of immigrants still mainly reside in 6 states (California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Texas, Florida), many more recent arrivals are settling in the Midwest and South. An ALA study of non-English speakers in public libraries revealed that most of the participating libraries were located in places with populations under 100,000. In 2006, the Department of Education reported that ELL children are the fastest growing student population, and projected that 1 in 4 students will be ELL students in 2025.

Youth services departments and school libraries can play a critical role in the education and cultural adjustment of young ELL patrons and their families. They are safe places, and offer opportunities to speak with friendly and interested English speaking adults. They have access to print and multimedia materials that will help them learn and practice English. Materials available in their language may encourage them to read to a child if they're an adult, or help them scaffold their learning if they're literate in that language. Foreign language materials, as well as items in the collection, library decoration, publicity, or events that reflect their culture will also make them feel more comfortable. These efforts will help them feel like the library is for them, and that they are true members of the community. Youth services staff have the opportunity to represent the core values of the profession by reaching out to people from different backgrounds: "we, as public library youth services managers, must lead the fight to uphold democracy here."

What's in a name?

There are many acronyms and terms associated with non-native English speakers. What term best fits your community?

ESL – English as a Second Language

Describes the type of program that enrolls non-native English speakers, rather than the speakers themselves. Also tends to be inaccurate, since many non-native English speakers know multiple languages, and English may be a third or fourth language.

ESOL – English for Speakers of Other Languages. Like ESL, this describes English language programs

ELL – English Language Learner. A term that has become more widely used in K-12

Gen. 1.5 – A group that arrived to the U.S. as children and grew up in it, but may not have the language and cultural fluency, or U.S. citizenship, of their second generation siblings A relatively new term to describe an old phenomenon.

Immigrant – A person who leaves his country and settles in another.

Refugee – A person who cannot return to his country due to persecution or a "well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, membership in a social group, political opinion, or national origin."

Although refugees are commonly lumped in to the broader classification of "immigrant," they do not have control over where they will resettle.

Asylee – A person who seeks refuge in another country to escape persecution. They must travel to and enter the U.S. before they can apply for asylum.

For more information, Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees has a comprehensive glossary of terms associated with U.S. immigration.

History

The history of library outreach to ELL patrons stretches back to beginning of American public libraries. The rise of public libraries coincided with the great influx of immigrants to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many librarians embraced services to immigrants to help ease their assimilation into American society. Libraries offered English classes, and promoted access to educational English and citizenship books, as well as foreign language materials.

Some libraries, like the Cleveland Public Library, established home libraries in neighborhoods that were far from library branches, which included many immigrant neighborhoods. Additional branch libraries were also added in factories, fire stations, and elementary schools. Some elementary school branch libraries also included adult materials in foreign languages so that ELL children could take home reading material for their parents. Multilingual story hours and youth clubs held in other languages also helped promote library service to immigrants.

Collaborations between libraries and and social service agencies were also common; librarians participated in citizenship classes to better understand naturalization requirements, and worked with social workers and instructors to identify immigrant communities and needs.

As early as 1916, the ALA discussed the possibility of creating a unit for librarians who worked with immigranta and ELLs. Within two years, in 1918, the ALA formed a committee: the Round Table on Work with the Foreign Born, which existed for thirty years.

Programming and Outreach

Librarians in the early 20th century recognized the importance of leaving the library and bringing services to the community. They proactively established home libraries in immigrant neighborhoods, and visited English and citizenship classes for insight into ELLs' needs. This outreach was important because immigrants were isolated, not only physically from the nearest library, but socially from the English speakers. Isolation is still very present in the lives of non-native English speakers. The state of isolation for today's American immigrants may be even stronger if they are illiterate, have no English experience, and settle in an area where no one else shares their culture or language. The 2008 ALA survey of ELL services in libraries notes: “Yet increasingly libraries...are more and more struggling to serve those linguistically isolated--a growing number that do not speak or understand English at a high enough level to understand the most elemental of communications.

Library programming and outreach can alleviate isolation by bringing the community together. Bilingual storytimes and family programs give both parents and children a social outlet and opportunity to form friendships. Some libraries have also used this time to introduce ELL families to the library with a tour and library card sign-up.

The Vancouver Public Library reported several success stories for how bilingual storytime changed its participants lives. A Chinese woman who was too shy and embarrassed about her English to visit the library, started attending regularly after she was approached and invited by a Chinese librarian. She later reported that the storytime helped her and her child became more sociable, and become friends with other families. A woman in a similar parent child group for Filipinos revealed that the friends she had made helped her become less dependent on her husband.

While the programs may help children develop literacy skills, parents also benefit through developing networks with other parents. Programs can also boost parents' confidence by encouraging them to participate and share their culture through traditional songs and rhymes.

Culture fairs are another great form of programming that can greatly benefit a neighborhood and improve relations between ELLs and native English speakers. Hilltop Library in Columbus, OH organized an event called "Latino Day" in order to promote library services to Latinos and promote Latino culture to the non-Latinos in the neighborhood. Over 270 people attended and the library collaborated with local restaurants and businesses to provide food and entertainment. Culture fairs are a fun way for the library to assert that ELLs belong to the library community, and that the library is a respectful and welcoming place.

Aarene Storms (2012) suggests creating a teen English discussion group to help teen ELL students practice their vernacular in a low pressure environment with other teens in ways that the more academic-centric school programs don’t allow time for. She provides a guide for starting your own that discusses the how to advertise and manage a teen talk group as well as the importance of flexible scheduling, teen leaders, and (of course) snacks.

Programming and outreach are also important because they can bridge the literacy divide. If ELLs do not come from a culture of recreational reading, and reading is the main activity they associate with the library, they're not likely to make a visit. Programming is an activity that can educate and entertain users from multiple cultural, linguistic, and educational backgrounds. This was one of the conclusions of the 2008 ALA report: “The emphasis on family programming, as well as targeting programming and collection to children, was powerful. This type of effort begins to overcome a major barrier that non-English speaking adults face ‘lack of reading and library habit,’ as well as ‘lack of knowledge about the library.’

School Libraries and ELLs

Nearly 5 million students in public schools across the country are ELLs. As the population of ELLs in schools continues to grow, school library media specialists must adapt in order to increase educational opportunities for their students who do not have native fluency in English. Students' linguistic backgrounds can affect not only their ability to comprehend what is happening in the classroom, but can also affect instructors' perceptions of students' abilities. Additionally, cultural backgrounds can also affect the way students approach school and learning. School library media specialists have the opportunity to act as advocates for students in multiple ways.

School libraries can push for incorporating multilingual and multicultural resources across the curriculum, not simply in language arts classes. School libraries can, for example, collect newspapers, music, or web resources from students’ countries of birth, based on in-depth knowledge of their communities. Using technology such as MP3 audio can be incredibly useful in supporting language instruction. If it’s feasible for your library, circulating MP3 players and downloading audiobook version of texts that students’ classes are reading can allow the student to both read and hear their assigned reading—or their personal reading as well.

If your district has dedicated ELL instruction, working with teachers to identify useful materials for instructional purposes can help support students in efficient ways. For example, the school librarian and ELL teachers at H.O. Wheeler Elementary School in Burlington, Vermont worked together to create visual aides for their students with limited to no English. These aides helped children convey their meal choices in the cafeteria, and understand the concept of a fire drill. The librarian also contacted a software company and explained the needs of their ELL students, and the company donated software, software licenses, and a computer in response.

Librarians can also act as a safe haven for ELL students in unfamiliar territory. School librarians have suggested the following techniques:

Learn ELL students’ names, welcome them personally, and recruit them as library volunteers.

Attempt to learn your users’ languages—greet students in their languages.

Display materials and posters for celebrations of diverse holidays, festivals, and heritage events.

School libraries are also uniquely poised to engage parents in literacy initiatives to strengthen communities and support their students. According to some reports, one-third to one-half of ELL students’ parents have less than a high school education. Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento has a high population of Hmong refugees. In order to engage students with reading materials of their own choosing and to promote parent engagement in their children’s education. the school librarian created a webliography of “talking stories” to help develop English skills and provided take-home laptops for students to use with their parents. The “talking stories” then helped encourage students to select library materials based on topics of interest. Involving parents of ELL students can be beneficial because parent engagement can “support students by developing parent relationships, strengthening families, and helping families develop more English skills and self-confidence so they can feel more energized and capable of working to improve their local communities.”

Collection Development

Reading often and broadly is one of the best ways to acquire vocabulary and learn a language. As librarians, we can help ELL users through thoughtful collection development that encourages them to read and use the library as much as possible. This means incorporating multiple types of resources and formats into the collection. It also means striving to find materials in ELLs’ native languages, as well as materials that respectfully reflect their culture.

Belmont Public Library, English as a Second Language webpage

A good collection will contain resources that support multiple learning styles and build off prior knowledge. Reading materials are important, but ELLs also need reference sources, like dictionaries, pictures, and bilingual and native language materials. Visuals can provide context for vocabulary words, and effectively explain unfamiliar concepts, such as information literacy.

Electronic resources often have many benefits; for example, students can see a word, hear it, and practice technology skills simultaneously. Different resources allow the patron to connect to new vocabulary in multiple ways and contexts, which strengthens their understanding and transfer of knowledge.

Marie Kelsey suggests that in addition to fiction materials, youth nonfiction with clear and concise writing can help develop vocabulary and awareness of concepts. She particularly recommends photo essays, which use copious illustrations to complement ideas in the book and make them easier to follow. Developing a diverse collection of compelling photo essays is beneficial to libraries on multiple levels--including supporting their ELL patrons.

Multilingual and multicultural resources not only enable ELLs to build off their knowledge base, they also motivate them to read. ELL parents will be more likely to read to their child and interact with them if they have books in their language. Pre-readers can gain enormous benefit from these interactions with their parents, regardless of language, because they are still learning literacy skills like narration, print awareness, and print motivation. Older children and adolescents are more likely to read material with themes they connect to and characters with whom they identify. They may also feel more motivated to learn in general if their self-esteem and “sense of belonging” is strengthened through the inclusion of materials representing their culture.

The challenge of collecting materials from other languages and cultures may be intimidating for librarians who do not belong to those groups. How can one discern if the materials are authentic and high quality? Your community will be one of the best sources of advice about what to collect and where to find it. This community includes not only ELLs, but ELL instructors, who may supply you with specific suggestions about what resources could supplement their lessons. Patrons may also be a valuable source of advice about whether there are local booksellers that carry materials in lesser known languages, like Bengali or Tamil. In terms of judging quality, Information scholar Denise Agosto suggests examining a work with five standards in mind: accuracy, expertise, respect, purpose, and quality.

She also recommends keeping an eye on multicultural award winners, like the Pura Belpre Award.

Examples:

Muzzy is a language learning program developed by the BBC for children with several language options, including English. It includes many cheerful animations and a storyline about a royal family in a fictional land that runs through the lessons. It provides video examples of phrases and matching exercises, unfortunately instructions are given in English. This is not a complete class in language development, but could be a useful supplement to ESL classes for children. For libraries with sizable ELL populations that provide children’s computers with preloaded games, consider devoting a computer to this program.

Mango is another language learning program that is marketed towards adults, but would be appropriate for middle grade and teen users as well. In addition to language learning for English speakers, it has a variety of courses for ELLs that includes written and verbal instructions in their selected native language. It also allows a microphone component for recording speech. One advantage of a subscription to this service is that it can be useful for both English and non-English speaking patrons, however focus is on conversational skills, so it is not a substitute for formal language classes.

Advice:

Be clear about the concept of a bilingual library because it can be defined in two different ways and whichever way you choose to interpret it would affect collection development. A bilingual library can be either a library with two distinct collections, one collection in English and one collection of exclusively foreign language material, or it can be a library with an English language collection and a collection of material that is both in English and in a foreign language within the same book. You can, of course, have both kinds of materials, but you should be aware of the distinction.

Order resources for a variety of learning levels because students may have been places in a grade level based on their age, but their reading level in their native language may be different and you want to be able to accommodate as many patrons as possible.

Do your research when looking for reviews and ordering from vendors. Although it is easier to order from the same vendor that you have always used for materials in English, there are vendors that specialize in non-English language material, and some vendors, like Follett and Baker & Taylor that have special divisions for non-English language material. Also consider publishers that focus on multicultural material (e.g. Lee & Low Books) which often includes titles in languages other than English, and publishers that specialize in foreign language material (e.g. Lectorum) to make sure you are getting a full and complete collection to serve your population of English Language Learners.

Attend as many conferences and professional development sessions as you can. As noted above, contributions and suggestions from the community you are trying to serve can be invaluable, but engaging with other professionals who also serve non-native English speaking patrons is another great way to get new ideas for cultivating your own collection.

There are grants out there specifically designed to help meet the needs of English Language Learners, such as those provided by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation for educated kids and racial equity, and the ELL mini grants funded by the National Writing Project that are given annually. It is important to be prepared when these opportunities arise by doing an assessment to find out what is lacking in your own collection and what you might need to better serve your diverse patron base.

For more on multicultural collection development click here.

Technology

In an ever-increasingly digital world, it is necessary to make sure that ELLs are able to have access to library digital resources. Library patrons may be unintentionally excluded digitally by providing instructions for using technology solely in English. “The ability to teach and provide written instruction in the patron’s native language is often overlooked, but the patron rarely complains because of the lack of English-speaking skills or embarrassment.” Providing instructions for using computers, the Internet, and library digital resources in languages of need is one way to increase ELLs’ success in using your library. For example, the Brooklyn Public Library has an program called TELL—Technology Literacy for English Language Learners—that provides basic computer instruction for those whose limited proficiency in English makes other technological literacy classes unfeasible. Even just having translated versions of your website can promote access to your constituency: the Brooklyn Public Library’s website is accessible in French, Russian, Chinese, Spanish, and Hebrew, the most commonly spoken foreign languages in the borough.

Visual OPACs provide another option for increasing your library’s accessibility for ELLs. Visual OPACs offer the option to toggle between text and images for OPAC records. Visual OPACs display search results with images of book covers, as well as “excerpts from chapters, video clips, audio files, magazine articles, or web site addresses.” These tools also allow users to search the catalog by clicking on icons or using integrated word processing programs. Some visual OPACs are customizable, allowing librarians to create lists—such as those books that might be required by a class or a list of books of interest for a display—and add icons to the search interface. Using these kinds of tools are powerful for increasing the ability of ELLs, who may not have the language skills necessary to run a sophisticated library search, to access library materials on their own.

As has been noted with Muzzy and Mango, technological resources can also help as language-learning tools. Electronic resources can help meet demands for English as a second language teaching tools and classes in public—and possibly even school—libraries. Resources such as audiobooks designed to teach English, streaming video (like those offered by the Orange County Library System, which are designed by professional ESOL instructors), and computer-supported courses like Rosetta Stone and ELLIS can provide unique opportunities for ELLs. “In addition to offering ESOL teaching opportunities free to patrons, these resources allow the Library to offer alternatives that do not limit patrons to fixed schedules and do not require the Library to hire tutors.”

Ensuring Equal Access

In her article, The Myth of Equal Access, Cary Meltzer Frostick argues that one of the biggest challenges facing libraries is providing equitable access information and education when serving a diverse collection of patrons. Providing patrons with the best possible assistance is always a bit challenging, but it can be especially difficult when those patrons speak a different language or have different cultural expectations. Being mindful of the obstacles posed by serving a diverse group of patrons, we have included a few important issues that may help guide your library’s policies and procedures to help ensure equality of access and the most effective service,

Literacy and Reading Habits

In the American Library Association’s 2007 report, “Serving non-English Speakers in U.S. Public Libraries,” literacy is described as one of the largest barriers for non-native English speaking patrons to using the library facilities and services. Non-native English speakers, just like other patrons who have limited or non-traditional literacy skills, or do not come from a familial environment where recreational reading is encouraged, may be less intrinsically motivated to visit the library, and would thus be unaware of the variety of helpful services that public libraries offer including literacy programs (one of the most common programs found in public libraries that serve non-native English speaking communities), technology and computer skills classes, and free and available internet access. The promotion of these services within the library and outside in the community could help alleviate this problem.

Library Facilities and Services

According to the “Serving Non-English Speakers” report, knowledge of the library and its role in the community is the second biggest barrier to ELLs using the library. Some families may have different perceptions about the function of a public “library.” For example, in several Latin American countries, libraries are not open for public browsing, but rather use a system of paging for materials and are often utilized solely by specialists and researchers. This is important to consider when trying marketing the library’s programs and services, like literacy programs, bilingual storytimes, and media classes, because those may seem very foreign to someone not familiar with a typical public library in the United States.

Once you get patrons into the library, there are other problems of access in the general administration of the library including the process of getting a library card, which may seem simple, but might actually be challenging for a non-native English speaker. To address this concern, try creating card applications that are more user friendly by adapting them to use the applicant’s native language, not asking for legal status, and allowing applicants to use an official photo ID from any country or a school ID as long as it is accompanied by postmarked mail from within the library’s service area.

Access to Collections

Providing a balanced collection of up-to-date materials, both fiction and nonfiction is the responsibility of a library that wants to provide an equitable level of service of all members of the community, but simply collecting the materials is not enough. Patrons should be able to access the materials easily and independently both in the catalog and the physical organization and display of the materials. The non-English language materials should be cataloged (as best as possible) in the original language or script so as to provide bibliographic access in English and the original language.

If the material is housed separately, make sure it is visible and accessible to the community with directional signage in the languages of the major linguistic groups that would be using that collection.

Other Possible Challenges

Challenges to bilingual education affect funding and support for non-English materials and teaching in languages other than English. It is important to prepare for backlash by those who think that resources spent on non-native English speakers takes away from money spent on native English speakers. Samuel Huntington's 2004 article "The Hispanic Challenge," presented a number of reasons that the author, a Harvard Political Scientist, warned that the recent influx of Mexican immigrants threatened "to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages." Huntington wrote, "the United States ignores this challenge at its peril." Many politicians and educators strongly disagree with Huntington, arguing that bilingualism is not a threat but an opportunity. An editorial in Rethinking Schools argues that bilingual education is both civil right, citing the 1974 Lau vs. Nichols court case, and a human right; they refer to the Convention on the Rights of a Child, adopted by the United Nations in 1989, which states that "the education of the child should be directed to ... the development of respect for the child's parents, his or her own cultural identity, language and values" (ctd in "Bilingual Education is a Human and a Civil Right”).

These arguments can be especially heated in communities where immigration is a divisive issue. Harrington (2012) suggests countering these arguments by collecting demographics to support the importance of these services, getting board members and staff agreement, and selling the library as a resource that helps parents adapt to cultural, language, and legal differences. Your programs and collections are also more defensible if they are unique to the community. If there are still concerns, remember that using politically motivated means to manipulate the library’s collection in order to alienate any particular group is a “marginalizing act” and goes against the intention of a public institution. Libraries should be providing free and open access to information that serves the needs of all members of the community. For helpful ideas and advice on how to enact this policy, please see Reforma’s Librarian’s Toolkit for Responding Effectively to Anti-Immigrant Sentiment.

Best Practices and Strategies

Collaboration

Collaboration both in and out of the library is one of the best ways libraries can effectively serve ELL patrons. Community agencies such as refugee resettlement agencies, Adult Education and ELL programs, advocacy groups, and--most of all--ethnic community groups, can pool resources with libraries to solve specific needs and offer more holistic assistance. In school libraries, librarians can work with ELL teachers to creatively overcome language barriers with students. Here are some examples of how librarians have solved problems through collaboration:

Library cards

The Utica Public Library worked with the Utica school district to issue every public school student a library card. Using the child’s school as proof of address eliminated a step and made it easier for ELL students to get cards. The school district also funded the translation of library card applications.

ELL classes and cultural programming

Columbus Library was able to offer free English classes in many of its branches by volunteering the use of its meeting rooms to the Columbus Literacy Council for classes several nights a week. The library also joined forces with several ethnic restaurants, stores, and the Friends of the Library to organize a cultural night to welcome the growing Latino population to the area and celebrate their culture.

Cultural miscommunication and behavioral disturbances

When a Columbus Library branch started having disciplinary problems with the local Somali teens, the branch manager contacted Somali community groups to seek advice from Somali elders. The elders suggested create and clearly display signs about behavior rules and translate them into Somali. The branch also began to offer homework tutoring after school.

Outreach

One way to deal with challenges of perception and access is to create a portable library. A Bookmobile well equipped with diverse language materials and ready to help with library card applications can be an initial welcome into the library and eliminate transportation problems found in low income communities. A cheerfully painted van or bus in a patron’s own neighborhood can be less intimidating than walking into a brick and mortar building. King and Shanks (2000) also advocate using a bus that can be equipped with internet terminals and audio-visual equipment as a way of demonstrating the various resources of a library and changing conceptions of those who come from cultures where libraries are formal, academic resources. An additional advantage of using the bus is that they can easily be brought to schools and ELL programs for convenient visits. Pairing these visits with bilingual story-times can be the perfect library introduction for young patrons.

Staff Training and Education

When there was an influx of Somali refugees to Columbus, OH, the Northern Lights Branch devoted a staff in-service to education about this new patron population. The branch manager invited leaders in the Somali community, and staff from the local refugee resettlement agency to share information for the staff about the Somalia's history and the present situation for refugees.

Re-evaluate Current Policies and Procedures

The Utica Public Library had to reconsider policies and procedures that didn't fit the realities of their ELL patrons. Some of these rule changes were allowing more than one child at a computer, issuing a warning rather than eviction for cursing, and removing children's limited borrowing privileges on DVDs.

Respect and Empathy

In her article, "Culturally Speaking," Sherry York provides some practical advice about treating ELL students with respect and empathy. She urges readers to avoid singling out students and embarrassing them, asking "simple questions that require only short answers," remembering what it's like to learn a new language and that one can always understand more than she can actually express (and speaking loudly to an ELL student doesn't help). She also points out that ELL students may have had to change their names upon coming to the U.S., and that the expectations of schools in other countries, and the student's culture, inform their behavior

Be an advocate!

Utica Public Library Youth Service Manager Cary Meltzer Frostick learned to be an advocate for her young ELL patrons and help change policies in their favor by collecting sympathetic stories and regularly relating them to the director, board members, and other important people in the community. This raised both the importance of the library in the public eye, and importance of extending equal access to ELLs in the community.

Resources

General

The American Dream Starts @ your library. – A toolkit of resources developed by the American Library Association to improve library service to foreign-born patrons.Thirty-four libraries contributed to extensive bibliographies, a history of libraries and immigrant outreach, and examples of best practices that have emerged through other libraries' experiences. Though some links no longer work, the bibliography and examples are still very valuable to any library serving ELLs.

**Arlington Public Library New Americans Page** – A libguide geared towards new foreign-born residents in Arlington, Virginia.

Library Service to Special Population Children and their Caregivers – A committee of (ALSC) Association for Library Service to Children that advocates for and works to improve library services to ELL children and their caregivers.

NCELA-National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition

Ohio Library Council Diversity Awareness and Resources Committee, Children's Services

REFORMA (The National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish Speaking) – ALA affiliate that represents the interests of Latino and Spanish speaking patrons through collection development, staff recruitment, and outreach efforts that educate libraries about Latino users and Latino users about libraries.

Spanish Language Literature - S.A.L.S.A. – This wiki provides strategies, professional development opportunities and resources in Spanish and in English about how to best serve the Latino community in school and public libraries. It includes book lists, collection development ideas, and publisher information as well as loads of other resources.

Serving Non-English Speakers in U.S Public Libraries – The 2008 ALA report about the state of public library services to non-English speakers.

Programming

Arlington County Bilingual Storytime Youtube Channel – This is the Youtube page of Cuentos y Mas, or Stories and More, a bilingual Spanish storytime filmed and featured on the Arlington Virginia Network. Includes about 20 episodes.

Dia – El día de los niños/ El día de los libros (Children's Day/Book Day) is an opportunity to recognize reading in the lives of children around the world. Founded by writer and poet Pat Mora, in collaboration with REFORMA, Dia is currently sponsored by ALSC and celebrated on April 30. Started in 1997, the event grows each year; over 300 libraries participated in 2011, its 15th anniversary. ALSC currently offers Webinars and educational resources for Dia on its website.

Multicultural Programs for Tweens and Teens,by Linda B. Alexander and Nahyun Kwon. American Library Association: 2010.

Windows on the World: Multicultural festivals for schools and libraries, by Alan Heath. Scarecrow Press: 1995.

Collection development

A,B,C's of Student Resources – a website provided by Champaign Schools containing helpful links that ESL patrons can use to learn English. Offers links to various topics such as idioms, games, flash cards and translation website etc.

Celebrating Cuentos: promoting Latino children’s literature and literacy in classrooms and libraries, ed. Jamie Campbell Naidoo. Libraries Unlimited: 2010 – Collection of articles and advice from Latino educators, librarians and authors. Includes comprehensive bibliography, historical overview, and programming ideas.

Colorín Colorado! – This is a free web-based service that provides information, activities and advice for educators and Spanish-speaking families of English language learners (ELLs).

ESL Kids Stuff – Features flash cards and educational activities for parents and ELL teachers to use with children. Great website to add to the collection.

Integrating Multicultural Literature in Libraries and Classrooms in Secondary Schools, by KaaVonia Hinton and Gail K. Dickinson. Linworth Publishing: 2007.

International Children's Digital Library – Digital library of foreign language books, available as e-books. The current collection is 4468 books in 55 languages.

Internet Public Library Pathfinder for Multicultural Literature for Children

Multicultural and Diverse Children's Literature LibGuide – LibGuide created by Michigan State University

Multicultural Review – A journal devoted to reviewing multicultural resources, including work published by small presses.

Reading is Fun-Reading Planet Book Zone – Interactive book site that users can create reviews read, recommend books, watch and listen to books.

Santillana Spotlight on English – Research and standards-based K-5 Program which helps ESL students develop English language proficiency and access grade-level content.

Starfall – a free public service to teach children to read with phonics.

Recommended Publishers and Review Sources

This list was adapted from a similar one given in "Bilingual Books: Promoting Literacy and Biliteracy in the Second-Language and Mainstream Classroom."

Arte Público Press – Its imprint for children and young adults, Piñata Books, is dedicated to the realistic and authentic portrayal of the themes, languages, characters, and customs of Hispanic culture in the United States.

Bilingual Books for Kids

China Sprout

China Sprout promotes learning of Chinese language and culture by providing Chinese and English books relating to Chinese language, Chinese test, Chinese food, Chinese zodiac, Chinese symbols, Chinese music, Chinese tea, Chinese calligraphy, Chinese New Year, Moon Festival, Spring Festival, Dragon Boat Festival and Chinese Arts.

Cinco Puntos Press – Publisher of adult and children's literature, and multicultural and bilingual books from Texas, the Mexican-American border, and Mexico.

Del Sol Books – Spanish, English, and Bilingual Children's Books and Music.

Hoopoe Books for Children – Stories from Central Asia and the Middle East available in a variety of languages.

Lectorum – One of the largest Spanish-language book distributors in the United States with a catalog of over 25,000 titles.

Lee & Low Books – An independent children's book publisher specializing in multicultural themes and authors and illustrators of color.

Mantra Lingua – This is a UK based publishing house, but offers dual language resources in over 50 languages, including less collected languages like Tamil and Yoruba, which means it could prove to be a very helpful resource.

Pan Asian Publications – It publishes bilingual picture books of Chinese folktales, stories, and legends to promote Chinese and other East Asian cultures.

Works Cited

Adams, Helen R. 2011. "Welcoming America's Newest Immigrants: Providing Access to Resources and Services for English Language Learners." School Library Monthly 27 (10), 50-51.

Agosto, Denise. 2007. "Building a Multicultural School Library: Issues and Challenges," Teacher Librarian, February, pp. 27-31

American Library Association. 2007. “Literature Review (2010)." Every Child Ready to Read @ Your Library.

American Library Association. 2010. "Public Libraries." The State of America's Libraries.

American Library Association. 2010. "School Libraries." The State of America's Libraries.

American Library Association Office for Research and Statistics. 2008."Serving Non-English Speakers: 2007 Analysis of Demographics, Services and Programs.

Asher, Curt. 2011. "The Progressive Past: How History Can Help Us Serve Generation 1.5." Reference and User Services Quarterly 51 (1): 43-48.

"Bilingual Education is a Human and a Civil Right.” Rethinking Schools Online. Winter 2002/2003. Web. 28 Nov 2011. www.rethinkingschools.org

Brisco, Shonda. 2006. "Visual OPACs." Library Media Connection 25 (3), 56-57.

The Cleveland Public Library. 1908.The Work of the Cleveland Public Library with Children.

Corona, Elena and Lauren Armour. 2007. "Providing Support for English Language Learner Services." Library Media Connection 25 (6).

DelGuidice, M. (2007). Cultivating a Spanish and Bilingual Collection: Ensuring the Information Literacy Connection. Library Media Connection, 26(3), 34-35.

Ernst-Slavit, G., & Mulhern, M. (2003). "Bilingual Books: Promoting Literacy and Biliteracy in the Second-Language and Mainstream Classroom." Reading Online, 7(2). Retrieved from http://www.readingonline.org/articles/art_index.asp?HREF=ernst-slavit/index.html.

Ferlazzo, Larry. "Family Literacy, English Language Learners, and Parent Engagement." Library Media Collection 28 (1), 20-21.

Frostick, Cary Meltzer. 2009. "The Myth of Equal Access: Bridging the Gap with Diverse Patrons." Children and Libraries 7 (3).

"Guidelines for the Development and Promotion of Multilingual Collections and Services." (2007). Reference & User Services Quarterly, 47(2), 198-200.

Harada, Violet H. and Sandra Hughes-Hassell. 2007. "Facing the Reform Challenge: Teacher-Librarians as Change Agents." Teacher Librarian 35 (2), 8-13.

Harrington, L. (2012) ELL programs in public libraries. Public Libraries, 51(5), 10-11.

Huntington, Samuel. “The Hispanic Challenge.” Foreign Policy. March/April 2004. Web. 26 Nov 2011. www.foreignpolicy.com.

Kelsey, Marie. 2011. "Compel Students to Read with Compelling Nonfiction." Knowledge Quest 39(4), 34-39.

King, B., & Shanks, T. (2000). This is not your father’s bookmobile. Library Journal, 125(10), 14.

MacCann, Donnarae. 1989. "Library Service to Immigrants and 'Minorities': A Study in Contrasts." In Social Responsibilities in Librarianship: Essays on Equality, ed. by Donnarae MacCann. Jefferson, NC: Metarland & Co: 97-116.

Mack-Harvin, Dionne. 2007. "Speaking the Language at the Brooklyn Public Library." Kirkus Reviews 75 (21), Special Section 1-3.

Mates, Barbara. 2004. "Who Aren't You Serving Digitally?." Library Technology Reports 40 (3), 6-9.

Melillo, Paolo. 2007. "Transforming ESOL-Learning Opportunities through Technology." Florida Libraries 50 (2), 11-13.

Orellana, Marjorie Faulstich, Lisa M. Dorner and Jennifer F. Reynolds.2006. “Children.” In Immigration in America Today: An Encyclopedia. Eidted by Larry J. Estrada, James Loucky, Jeannne Armstrong. Santa Barbara, Greenwood. http://ebooks.abc-clio.com.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/reader.aspx?isbn=9780313083099&id=GR1214-779.

Patton, J. (2008). You're Not Bilingual, So What?. Library Media Connection, 26(7), 22-25.

Prendergast, Tess. 2011.“Beyond Storytime: Children’s Librarians Collaborating in Communities." Children and Libraries 9 (1) Spring.

Quesada, Todd D. 2007. "Spanish Spoken Here." American Libraries 38 (10), 40-44.

Reforma. (2006). Librarian’s toolkit for responding effectively to anti-immigrant sentiment. Retrieved from http://www.reforma.org/content.asp?contentid=67

Riley, Bobby. 2008. "Immersing the Library in English Language Learning." Library Media Connection:

Shelley, Kristin. 2004. “The Faces of Change in Columbus.” Ohio Libraries Vol. 17, Iss. 2; p. 10

Storms, A. (2012). Talk Time for Teens, Alki, 28(2), 16-17.

Walters, Nathan P. and Edward N. Trevelyan. 2011. "The Newly Arrived Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 2010. " American Community Survey Briefs. U.S. Census Bureau.

York, Sherry. 2008. "Culturally Speaking: English Language Learners." Library Media Connection 26 (7).

[Tumblr transcriber: Camilla Y-B]

#library community#wikispaces#professional development#library#librarian#english language learners#english as a second language#Youth Library Services

1 note

·

View note

Text

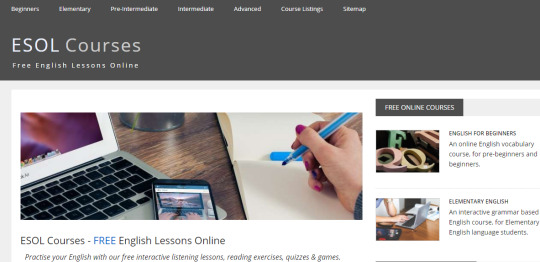

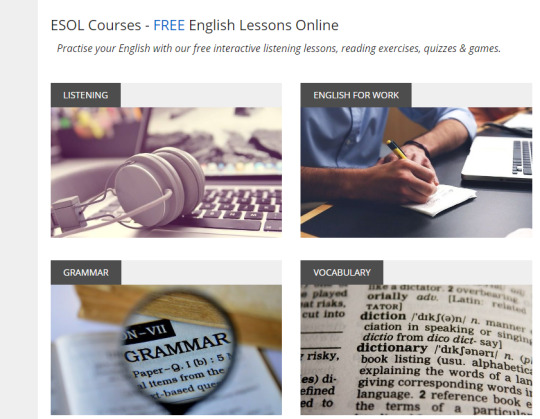

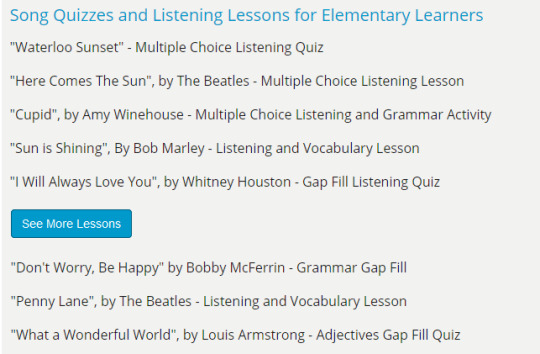

EVALUATION OF A WEBSITE:ESOL COURSES

Hi everyone!

Today, I am going to talk to you about the evaluation of an ELT website. I chose a website called ESOL Courses (Free English Lessons Online) to evaluate and share some information with you. Esolcourses is a free online teaching and learning platform. It publishes free online self-study lessons for English students, and classroom resources for English language teachers. Their lessons are free for their visitors to use. Registration is not required.

(You can see the website by clicking the here.)

The content of website is about three skills like reading listening and writing. It also has a lot of content for students to develop pronunciation, grammar and vocubulary. you can see the English levels at the top.You can choose your own level from there and practice them. It is more suitable for adult use, but you can find content in children. Of course the target audience is students, teachers, and English learners. There are many sections on this site. I chose the listening and vocabulary section from these sections at elementary level in order to evaluate.

THE LISTENING SECTION

In the listening section, the student can choose a song he/she want. Then he can watch the video on the song and answer the quiz questions. Students can watch to the video more than once. The student learns the pronunciation, the meaning of the word, and some common phrases used in English. If you wish, you can take a look at the quiz and exercises from this here

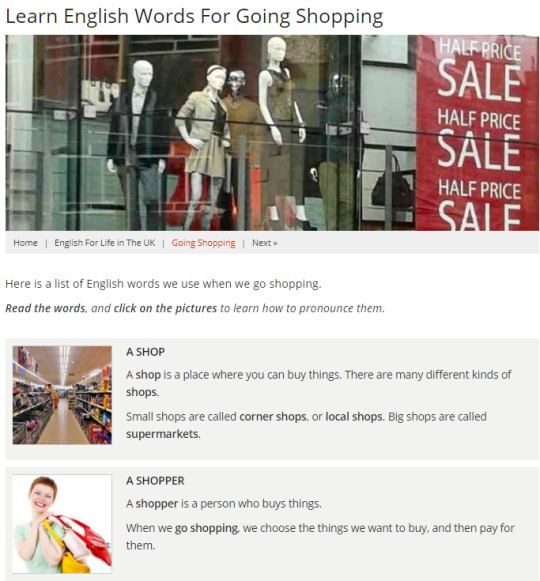

THE VOCABULARY SECTION

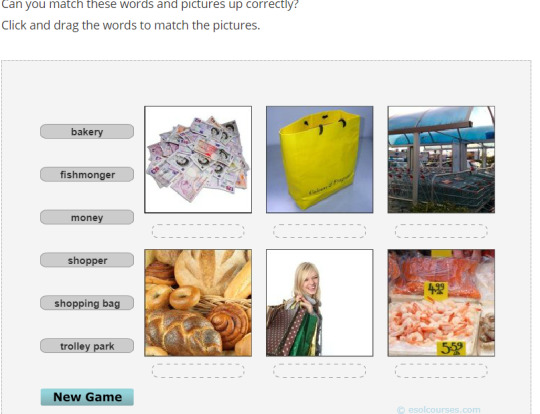

In this section, the student can see the word related to a topic he/she select. It is shown pictures about words and is made the definition of the word on this website. You can listen to the pronunciation of the word by clicking on the pictures. If you want to see the example, you can click the here

In addition, students can exercise or make a quiz and can play online games about these words like matching the word with the picture. You can see more sample here

there are some points I don't like on this site. One of them is that the design or interface is very ordinary. The other is that the content is very limited. The content could be varied by increasing the number of tasks such as various games and vocabulary and listening exercises.The interior design of the website could be made more vivid to attract students' attention.

You can use this and many sites like this for learning and teaching English. Students have the opportunity to improve their skills like listening, reading and writing thanks to the website. As a English Teacher:

1-) can use this website to enable their students to further enhance their English language skills. They can give homework for students to do practices on this website but it can be hard for students who don’t have access to the internet.

2-) can benefit from the practices on this website by using them during the lesson at school.

3-) a source for English teachers for listening, reading, grammar and writing activities.

Take care of yourself!! See you in the next post...

0 notes

Text

A different way to improve your English: Read/Write Poetry

A different way to improve your English: Read/Write Poetry

Learn English through poetry! Open the poetry sites below to read and/or contribute your own poems. Poems By Heart uses brain-training techniques to make remembering poetry easy and fun—in a fast and responsive game. Each poem features two new and exclusive dramatic readings, and all-new original art. Improve your English by practicing with poem activities. Poetry Foundation With the Poetry…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Pre-Intermediate English - The Hippo That Lives in a House

See on Scoop.it - Education 2.0 & 3.0

A multiple choice listening and vocabulary lesson about a hippo that lives in a house, for adult pre-Intermediate ESOL learners and English language students. Watch a short news report about an unusual pet, learn some new vocabulary, and complete a multiple choice quiz. Includes mobile friendly online activities and a printable dictionary skills worksheet. Suitable for self study or classroom use.

0 notes

Text

Blog #5: A Guide for Collecting Qualitative Data

Before reading these chapters, my goal for collecting data had primarily been to conduct semi-structured interviews throughout the study. After reading Merriam and Tisdell (2015), I understood the importance of combining observations with interviews. Hatch (2002) provided additional insight into why more formal observations would help to "capture more verbatim classroom conversations and more explicit descriptions of classroom interactions" (p. 75). The readings were beneficial for me as a novice researcher because I began to envision the specifics of the type of research study I want to conduct based on my theoretical framework. I am still pondering the level of involvement I want to have with my study participants. I do not want to be completely unknown to the participants; however, I do not want to be a complete participant either. I know I will be at least moderately involved in my observational work. This is something I will continue to consider as I create my proposal for my qualitative study.

In regard to my observations, the setting will be outside or in an informal environment where participants can sit together and converse (i.e. picnic benches or couches in a lobby area). There will be a small group of participants (9-14 adult ESOL students) and two native English speaking proctors who will guide the conversations and activities of the session(s). I will be observing interactions between participants and between participants and the class leaders. I intend for my role as the researcher to be minimally participant. While I will be present for the session(s), I will not be interacting with the students or the native English speakers. I know that my presence will change the way the students interact with each other and the leaders. However, I want to try as much as possible to bring little to no attention to myself so that the interactions in the session(s) can occur naturally. The purpose of the session(s) will be to get the participants (adult ESOL students) to speak as much as possible in the target language, English. I already decided after reading about recording observations in Merriam and Tisdell (2015) that I will not be video-recording the sessions. I think bringing in camera equipment will have a negative effect on the way the participants interact with each other and the leaders of the session. Because my study is focused on participants who are learning to develop their speaking abilities in a second (or more) language, a camera could definitely inhibit students from feeling comfortable using the target language. The concept of making a mistake in a new language while being recorded can be devastating for language learners (I can empathize with this feeling as a second language learner as well). Therefore, I was able to make a clear decision in regard to recording observations, and it is that it will be detrimental to the data. While Hatch (2002) states that researchers can build time for participants to get used to being videotaped, I think due to the sensitivity of speaking in a second (or more) language, video-recording will present too many problems for the study design.

The readings for this class have been exceptionally helpful in creating a road-map of how to set up a qualitative research study. In my time as a doctoral student, I have read through many qualitative studies and used them as examples for methods I could use in the future. However, Merriam and Tisdell (2015) and Hatch (2002) thoroughly prepare the reader for significant considerations that I would not have contemplated on my own by solely examining qualitative examples.

References:

Hatch, J. A. (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons.

0 notes

Link

HOLYOKE — Easthampton resident Keith Hazel, a 39-year-old high-school dropout, will be the keynote speaker at “College for a Day,” a Holyoke Community College (HCC) event that brings hundreds of adult learners to campus each year to get a brief taste of college life. The Thursday, March 15 event runs from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. on the main campus at 303 Homestead Ave., Holyoke.

Students and teachers from dozens of adult basic education and ESOL programs in Hampshire and Hampden counties are expected to attend College for a Day to sample classes taught by HCC faculty and staff in the areas of sustainability, math, careers, computers, conflict resolution, stress management, health, money management, STEM (science, engineering, technology, and math), and life and literature.

Before that, beginning at 9 a.m. in the Leslie Phillips Theater, Hazel will talk about his life and educational journey, from high-school dropout to HCC liberal arts major. Hazel earned his high-school equivalency in 2016 through the Literacy Project in Northampton and completed HCC’s Transition to College and Careers program in 2017 before enrolling as a degree-seeking student last fall.

College for a Day is organized by HCC’s Adult Basic Education and Transition to College and Careers programs, the HCC Admissions office, and the Holyoke-based Community Education Project. Since 1999, nearly 2,000 adult learners have participated in College for a Day.

The post Adult Learners to Explore College for a Day at HCC on March 15 appeared first on BusinessWest.

0 notes

Text

adult learning center nashua

English as a second or foreign language is the use of English by speakers with different native languages. Instruction for English-language learners may be known as English as a second language (ESL), English as a foreign language (EFL), English as an additional language (EAL), or English for speakers of other languages (ESOL). English as a foreign language (EFL) is used for non-native English…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Empowering speech, challenges on ‘correctness’ and some questions for sociolinguists.

A couple of years ago I wrote a post called ‘Modelling good speech: Let’s talk properly‘ and, on a whim, I recycled it very recently. It’s very much a ‘from the hip’ kind of blog but, nonetheless, most of the responses I get are positive, including from English teachers. However, there has always been some heavy – even angry – criticism including most recently from various people including sociolinguists like Rob Drummond and commentators like Oliver Kamm from The Times. I have just found this article that pretty much rips my blog apart on a blog for English Language A level students – it captures some of the negative responses: http://ift.tt/2hbIFDR. I tend to filter out the outrage but it’s impossible to be criticised so robustly and not take notice. So, as promised in my twitter exchange with Rob, Oliver and James Durran, here is a follow-up. I have genuine questions.

The context for my original post was working in a very mixed school where the range of speech modes was huge and where the issues of disadvantage and empowerment were evident daily. One example I often think of was hearing a successful academic student with a key leadership role giving a report in assembly after a very special school trip. This was, without question, an occasion for formal speech where a formal speech code would have been appropriate, not least because he was a significant role-model. Through-out his speech he used ‘done’: “We done a trek; we done a trip to the market; we done a presentation”. He was an EAL student having arrived from another country some 10 years before but my instinct was that, since he had been in that school for six years, we should have done a better job in teaching him the formal speech code that would have led him to say ‘we went on a trek; we gave a presentation’ and so on.

My sense is that, without that fluency and self-awareness, this student will be undermined and undeservedly disempowered in the real world where formal speech carries significant value. Is that wrong? It was also my strong feeling that a major reason this student had not yet fully mastered appropriate formal speech was that, throughout his time in the school, teachers had been reluctant to address the issue on a day to day basis for fear of being insensitive or denigrating his default speech mode. I discussed it with him explicitly – because he had interviews to prepare for. He saw it as a failing of his education that he hadn’t been taught to ‘speak well’ – as he put it – even when he wanted to and he was concerned that the habits were now hard to break.

Another context is that the Speaking and Listening component of English GCSE, while it remained, had yielded startlingly good results, catapulting the school into the top 5% of value-adding schools for English GCSE overall. Did this match their actual confidence with speaking in general or their underlying skills with English language? No. It was an illusion generated by intensive scripted rehearsal with serious consequences – because there had been no emphasis on building authentic confidence with formal speech.

In response, we introduced a wide-reaching oracy programme to address the issue with structured speech activities across the curriculum. Project Soapbox – giving every KS3 child an opportunity to make a public speech – and poetry recitations were becoming a feature of school life alongside more regular opportunities for debates, presentations and student-led teaching episodes. More simply, we were trying to develop a culture were students gave more extended verbal answers in class and, yes, where certain common ungrammatical phrases were challenged/redirected/corrected.

This has nothing to do with dialects or accents. I used to work in Wigan where accents were so localised that, even as a Southerner, after three years I could tell if someone came from Leigh, Wigan, Skelmersdale or St Helens. It was part of everyday chatter that accents and phrases were discussed. My own use of English was a constant source of banter with students. Some students would use phrases like ‘ave for t’ go for t’ get bus’ (affott go fott get bus). That’s the kind of linguist diversity that we should all embrace. But those students could also say ‘I have to catch a bus’ if they needed to; if they chose to. My use of ‘properly’ is only meant in reference to that context when students simply make mistakes in relation to a formal code that they themselves are seeking to use.

However, as a result of this debate, I understand that it is important to be very clear about context and terminology and I regret the rather flippant approach taken in my original post. It was meant as a provocation but that now seems inappropriate and certainly open to misinterpretation of the intentions. If there is a bit of an us/them element, the ‘us’ is anyone who is fluent in using formal English appropriate to any formal setting whenever they wish; the ‘them’ is anyone disempowered by not having full access to that code. My intentions are good – despite the dismay and disapproval my post generated for some.

I am keen to understand how we can move forward with this vitally important agenda whilst also taking account of sociolinguistic factors.

I wonder if we could all agree on some things:

Language is constantly changing so any sense of ‘correctness’ could only ever be temporary in a very specific context and, as such, is problematic.

There are multiple forms of language that make up what we call English, each of which has value; the relative value placed on any one code is arbitrary and driven by social factors, snobbishness and so on.

The speech of those in positions of power should not, on principle, dictate what is correct or proper for everyone in their everyday speech. ‘Correct’ and ‘proper’ have no value at all as terms for language in general.

At any given time, de facto, there is a widely accepted formal speech code that can be defined through common grammatical rules and vocabulary albeit with wide- ranging, constantly evolving alternatives. This code is aligned to written Standard English and the common speech mode of those in powerful privileged positions and, as such, is, de facto, empowering, whether we like it or not. It is important for children and adults to have access to this speech code and to be able to use it in the appropriate context – or at least have the capacity to choose to use it.

We are never talking about or privileging certain accents: formal speech, however it is defined, can be and is spoken in any accent.

In order to have a discussion about speech amongst a group of educators or with our students, it is useful to have some terminology we can use to describe a situation where one form of speech might not be appropriate – i.e. where, as a teacher, you might suggest that your student says something in a different way. I find it hard not to say ‘incorrect’ – but I understand why people might object. Do we ever say speech is inaccurate, incorrect, ungrammatical, inappropriate? Is language really that fluid? Do we always have to add the tagline, ‘in this particular context’. Can we not agree that, if we are talking specifically about teaching students to use the prevailing formal speech code, then some structures are ‘correct’ in the context of that code – or is ‘ungrammatical’ better as I’ve seen Oliver suggest? Or is ‘inappropriate’ always the best term?

Let’s use some specifics – avoiding my flippant pet-peeves, which, I readily acknowledge, simply reveal my prejudices and snobberies. I’m also avoiding phrases that might be associated with friends chatting. I’ve never said anything to suggest that we’re trying to mandate how people speak to each other outside a formal speech context. These are all things I’ve heard said in school/classroom context:

We done an experiment.

We was writing a story.

How much people was there?

What was you saying about it?

She done excellent in that performance.

Is nothing in speech ever wrong? Is it never wrong in a school classroom context? Or is it simply inappropriate? Do I, as a teacher, have the right to determine that, in my classroom, we use formal speech codes and set some parameters for appropriateness? Or, does a school – supported by a Headteacher or school policy – have the right to assert that, in all our educational interactions, we use formal speech codes? If so, what do we do and say when students use other codes – or simply make mistakes when trying to use the formal code, assuming we can tell the difference?

If we agree that we want to empower all our students with the ability to use formal speech when they choose to, isn’t it much harder to achieve in practice if we are often inhibited by the need to be sensitive to and give value to linguistic variations at the same time? Isn’t it easier to say that, at school, this is how we all speak? Why? Because, in life, it will empower you and we need to give you as much practice as possible.

This is especially difficult to manage when we have learners of different kinds to cater for:

First language English speakers simply improving their vocabulary and fluency but living in a world dominated by formal spoken English

First language English speakers who routinely use a different code in their home life and peer group associated with their family/social origins

First language English speakers who switch codes routinely between home and school and peer group but predominantly use a local speech code with wide ranging alternative uses of grammar and vocabulary, independent of social background

ESOL/EAL speakers who are new to the country and want to learn formal English or to match the form of language they use in their native language.

2nd generation EAL speakers who predominantly speak in English learned from other EAL speakers in their peer group and at home.

If I’m learning to speak more fluently, simply as a first language speaker, I’d hope my teachers would give me appropriate direction. However, what if they find it hard to challenge my ‘errors’ (if that’s what they are?) but not those of other members in the class where they are not short-term errors but routine parts of their everyday speech? Or is this just down to my parents and off-limits to teachers unless, very literally, I am giving a speech?

If I learn French, I don’t want to learn the equivalent of ‘we done an experiment’ or ‘she done excellent’. I don’t want to be told that is fine – except in a formal context. I want to learn a grammatically accurate form I can use anywhere. This was the point of me citing the David Sedaris story from ‘Me talk pretty some day’ in my blog. ‘He nice, the Jesus‘ is funny. It makes light of the challenge of language learning – it’s good comic material. There’s always a sense that learning a language is aimed at a particular form of it in the main, especially at the early stages. That’s sensible enough isn’t it? If that is right for me learning French, why isn’t it right for an EAL student? For them, isn’t it more helpful if, at all times during the school day, they are being directed towards a certain speech code if they simply want to learn to speak formal English as well as they can?

If my son said something like ‘I’m going shops now, innit’, as his parent, I would challenge him on that. Is that not my responsibility as a parent to guide my child’s speech? Is there a line between ‘teaching to speak’ and ‘teaching to speak well’? Would any of the sociolinguists I’ve angered handle this differently? Is there a line where language becomes slang or falls below a standard that is appropriate even at home? Who decides? And is it right that I have a different set of rules for my children compared to my students – if we share the goal that all of them must conquer the challenge of using formal spoken English with fluency and confidence? I worry a lot that we’re simply fuelling a divide here. Formal language for some but not for all? I’m ok, my kids are ok but you don’t need what we have? To me, that really is patronising and disempowering.

If your answer is but of course we also teach formal language my questions are about the practicalities. It’s quite a subtle message to give consistently that ‘it’s not wrong, it’s just inappropriate’ and I can imagine that slipping quite often even if the intent is there amongst teachers working with the best intentions. Surely that’s less of a problem than saying nothing and accepting any form of speech you hear – even when your instinct is that it’s inappropriate for the context?

My overriding sense is that, given the complexities of teaching a diverse group of students, it is legitimate and pragmatic to assert that, whilst recognising diversity in all manner of ways, we want all students to learn to use formal speech codes and that, therefore, a school needs to focus on it and reinforce it in every in-school context. I accept that calling this ‘speaking properly’ is unhelpful if the wider diversity message isn’t also strong. However, we have to be realistic about the pace of social change. It might be important to challenge the power structures around dominant language codes and to champion greater diversity and confidence with multiple speech codes – but that’s the long game. An academic debate about sociolinguistics and the injustice of language snobbery is no use to a student wrestling with formal English if, as a result of institutionalised awkwardness, they never master it – and meanwhile, the students down the road are walking tall because they can switch codes with ease with all the advantages that brings.

I hope that’s a helpful contribution. More questions than answers.

Empowering speech, challenges on ‘correctness’ and some questions for sociolinguists. published first on http://ift.tt/2uVElOo

0 notes

Text

TEFL/TESOL Franchise Opportunity

*Join An Established Network! Become Westminster College London Franchise

*TEFL teaching and training is a massive global industry that continues to grow year upon year.