#Akhmad Kadyrov

Text

Dear RAMZAN AKHMATOVICH! In the most difficult time, you trusted me to serve on the great Path of Akhmat-Khadzhi for the benefit of your people, the republic and the Fatherland! I am proud that I was lucky enough to stand next to Akhmad-Khadzhi and with you, and to take an active part in the fight against terrorism and the establishment of peace in the Chechen land! It was a long journey, on which all difficulties faded thanks to your support, BROTHERLY shoulder, hope that you inspired, no matter what.

I am proud that our BROTHERHOOD, hardened as steel, allowed me to contribute to the revival of the region, to become part of the legendary KADYROV Team. Everything that I have achieved over the years is solely your merit. For me, there is no higher honor than to serve next to you on the noble Path of Akhmat-Khadzhi, and the highest assessment for me is, of course, the assessment given by you!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The constant boom of artillery in the near distance is the defining feature of life in the Donbas today. As Russia presses its offensive to take the eastern part of Ukraine, the signs of conflict are everywhere: buildings smashed to ruins by cruise missiles, Ukrainian tanks and howitzers on the highway headed east. The Donbas region, encompassed by a front stretching hundreds of miles and currently the scene of the most extensive fighting in Europe since World War II, is in total war mode.

The Russian military machine, which has overwhelming superiority in artillery, is grinding forward slowly but surely, conquering an additional kilometer or two a day at immense cost to the defenders. Exhausted Ukrainian soldiers speak of weeks of fighting under relentless bombardment, heavily outgunned by an opposing force that has recovered from its initial blunders and is now fighting the sort of war it was designed for. Under Vladimir Putin’s leadership, Moscow is pushing on eastern Ukraine a fate much like the one it imposed on another unruly former vassal at the start of Putin’s reign: Chechnya.

The Russian plan for Ukraine is grimly apparent from that earlier template. In a years-long conflict, which began more than two decades ago, Putin destroyed a sovereign state and subjugated its people, creating in its place a land of ruin, chaos, and fear. For that same plan to proceed in Ukraine, a country with a population 40 times the size of Chechnya’s, would be exponentially more ruinous.

The plan unfolds in a few set phases. The first is pacification. This comes quickly where it can, and slowly, via obliteration, where it cannot. In Chechnya, the rapid part took place in most of the outlying areas, the towns and villages that dot the once-picturesque Terek River plain, where Russian forces rolled through in late 1999. In the case of Ukraine, the south was easily overrun; the open terrain and insufficient defenses offered little resistance to the Russian advance that swept through cities such as Melitopol and Kherson in the offensive’s first week.

In other areas, the more lightly armed defenders hold out en masse, especially when they are able to utilize the cover of major urban areas. This necessitates the other main Russian tactic. In the Chechen capital, Grozny—whose very name, chosen by a czarist general, means “terrible” in Russian—the level of bombardment rained down upon the defenders from late 1999 to early 2000 was so great as to gut nearly every building in the city. Its vacant shell was assessed by the United Nations as the “most destroyed city on Earth.” In Ukraine, this fate has been visited upon Mariupol: once a handsome and vibrant city reduced under three months of siege to a smoking ruin.

Occasionally, of course, the defenders must be reminded that their failure to submit unconditionally entails the most severe consequences—not just for the fighters but for their families too. In Chechnya, Russian troops habitually lined up entire civilian populations of villages or neighborhoods for massacre; in the town of Novye Aldy, for example, at least 60 civilians were summarily executed in February 2000. In the suburbs of Kyiv, such as Bucha, Irpin, and Borodyanka, Russian soldiers similarly demonstrated the price to be exacted for resistance.

Once the Russian conquest is complete, a suitable satrap must be found and empowered to rule the natives. Even the Chechens, a people whose spirit of near-unbreakable resistance inspired Russian writers from Tolstoy to Solzhenitsyn, offered up a few candidates. Chief among them was Akhmad Kadyrov, the former grand mufti of Ichkeria, as the independent republic was known. His rule was brief, ended by assassination in 2004, but his remarkably brutal son Ramzan, himself a former rebel, proved an effective substitute. In Ukraine, there have been candidates enough in the already occupied parts of Donetsk and Luhansk, and other, newly captured regions have put forward their own: a local thug who sees a chance for advancement under the new boss or a pliant councilwoman who is willing to provide an ersatz sense of normalcy while the occupiers go rooting out the holdouts.

Finally, the establishment of the new order. Of necessity for a time, the locals will be held down by occupation forces, but they must come to obey their own, to be self-sufficient in their repression. A new apparatus of domination will be constructed, one that sees the vanquished take responsibility for crushing the remaining indigenous resistance. Token incentives will be provided: some Potemkin redevelopment in the style of Grozny’s garish neon skyscrapers or its enormous mosque (for a time the largest in Europe).

The traumatized citizens will be taught a new version of their own history, one in which their absorption into Russian vassaldom was entirely voluntary and, in fact, a salvation from “radicals” and “terrorists” who had sought to destroy them. Eventually, the new generation will be brought up with the idea of service to the Russian motherland as a sacrosanct obligation, under the guidance of a leader who renames the capital’s main avenue after the Russian president and regularly declares himself Putin’s “foot soldier.” Military service in the next round of Russia’s imperial conquests will be not only expected but enforced, with conscription drives hauling off young men from these new territories for whatever the next war is.

Perhaps the most ominous aspect of this plan is the Russian willingness to wait years, if necessary, to enact it fully—even if a seemingly durable truce delays progress toward that goal with a prolonged pause in military operations. The First Chechen War, in the mid-1990s, did not end in Russian victory. That came later, and only after a debacle that saw Russian troops suffer a humiliating defeat in the second Battle of Grozny in August 1996, when groups of well-coordinated Chechen insurgents infiltrated the city and cut off Russian units trapped inside. The blunders of the first month of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were strikingly similar to those of its initial two-year campaign in Chechnya. Back then, we saw the same absurd political expectations of no resistance—Russia’s then–defense minister, Pavel Grachev, famously claimed that he could take Grozny in two hours with a single airborne regiment—and the same phenomenon of confused, demoralized Russian soldiers deserting their vehicles.

The resulting cease-fire agreement, the Khasavyurt Accords, had Russian troops withdraw from most of the republic and even saw Moscow recognize Chechen sovereignty, in a seeming decisive victory for the separatist cause. But Moscow was patient, waiting and watching as the nascent but devastated Chechen state started to rend itself apart. With central authority destroyed by years of war, the republic’s president, Aslan Maskhadov, was unable to establish control over the various militias that had formed and grown in power throughout the war. In this atmosphere of chaos, poverty, and death, the secular nationalist forces that had provided the Ichkeria movement with its initial impetus were shoved aside by the growing influence of right-wing radicals—in this case, Salafist Islamist militants led by the infamous commander Shamil Basayev, as well as foreign ideologues such as the Saudi warlord Ibn al-Khattab.

In the meantime, Russia’s reconstituted army and government, under the direction of Prime Minister Putin, found a renewed casus belli: a series of bombings of Russian apartment buildings, atrocities widely suspected to have been conducted by Russia’s secret service, the FSB, in a cynical false-flag operation to justify a second invasion. This time, the Russian army used its overwhelming firepower to destroy any Chechen resistance before advancing into Grozny’s ruins.

In Chechnya today, the process is complete; the republic long ago reached the final stage of imperial integration. Behind this apparent settlement, a cosmetic, temporary peace reigns. Grozny’s seemingly prosperous streets and gaudy cafés front a republic of fear, in which militiamen and security officers, both plainclothes and uniformed, rule with impunity. The recent past can be discussed only in whispers: Even around a family dinner table, most Chechens will not risk the slightest criticism of Ramzan Kadyrov, for which they can be arrested, tortured, or worse.

Thirteen years after the declared end of the Second Chechen War and the insurgency that followed, the region continues to produce more refugees than anywhere else in Europe, as people flee the regime’s arbitrary repressions in numbers that have only lately been eclipsed by the movement of refugees from Ukraine. At the same time, a tangible anger bubbles beneath the surface everywhere, a burning hatred toward Kadyrov and his brutal ilk. Nearly all Chechens expect that a third war will one day erupt—with the implicit hope that, this time, Kadyrov will be dragged from his palace to meet a similar end to Muammar Gaddafi’s in Libya.

Russia’s plan for Ukraine, in the south and the east, is still at an early stage. In the Kherson oblast, captured by Russia in May, plans for a referendum that will either establish a sham independence or join the region to Russia outright are afoot. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians who have been conquered or carted off into Russia are now being fed the same revisionist history lessons that students in Chechnya have received for two decades already. In another parallel, an insurgency is taking root against the occupiers in the country’s south.

For now, Ukraine’s fate remains in the balance. The nation is much larger than Chechnya, and its people are committed to the struggle. The flow of military aid to Kyiv from the West far outstrips anything the beleaguered rebels of the North Caucasus could count on. Yet the logic of attritional conflict is now on Russia’s side, and Putin’s strategic patience is based on sound precedent. Moscow knows what it wants the outcome of the war in eastern Ukraine to look like, because it will look like Chechnya. Should the West abandon a ravaged Ukraine to a similar fate—a flawed cease-fire leading to a failing state that is prey to a refocused Russian assault—this will be the scenario.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

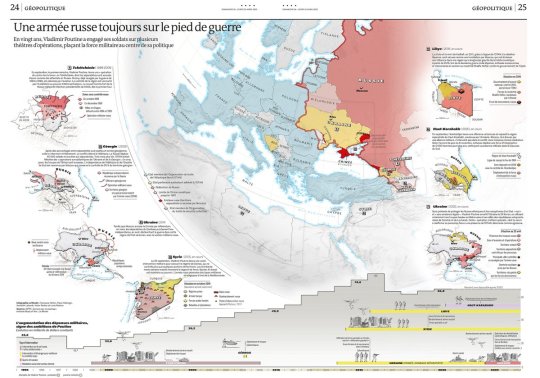

Russian military operations abroad in the past decades.

by @XemartinLaborde

In twenty years, Vladimir Putin has committed his soldiers to several theaters of operations, placing military force at the center of his policy

Chechnya, 1999-2009: In September, the Prime Minister, Vladimir Putin, launches a “counter-terrorism operation” in Chechnya, whose separatists are accused of having committed attacks in Russia. Grozny, already devastated by the war from 1994 to 1996, was pounded by the air force. Control of the region is locked by the installation in power of Akhmad Kadyrov. Russia's new strongman won the 2000 presidential election in the first round.

Georgia, 2008: After clashes between South Ossetian separatists and the Georgian army, the latter started a military intervention. The conflict spreads to Abkhazia. Russia is deploying 40,000 troops in support of the separatists. Three months earlier NATO had welcomed “the Euro-Atlantic aspirations of Ukraine and Georgia; In five days, the troops of Tbilisi are crushed. The independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is recognized by Moscow, which retains control of 20% of Georgian territory.

Ukraine, 2014: Annexation of Crimea, and war in Donbas with the military support of Russia

Libya, 2016, in progress: The fall and death of Gaddafi in 2011, thanks to NATO's support for the Libyan rebellion, are experienced as a humiliation by Moscow, which sees its influence diminishing in a region that has long gravity in the Soviet orbit. From 2016, during the second Libyan civil war, Russia sent arms and mercenaries in support of Marshal Khalife Haftar, against the government of Tripoli.

Syria, 2015, in progress: On September 30, Vladimir Putin launched a vast military intervention to rescue the regime in Damascus, which now controls only a small portions of the territory. The massive aerial bombings reversed the balance of power. Bashar Al-Assad is kept in power. The Russian army maintains strategic military bases east of the Mediterranean.

Nagorno-Karabakh, 2020, in progress: At the end of September, Azerbaijan launched a victorious offensive and recaptured the separatist region of Nagorno-Karabakh, supported by Armenia. Moscow, linked to Yerevan by a military alliance, does not intervene in the conflict, but imposes itself as a mediator. According to the November 9 peace agreement, Russia deploys a peacekeeping force of 2,000 men for five years, reinforcing its military presence in the South Caucasus.

Ukraine, 2022, ongoing: Under the guise of protecting ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers from a "nazi" state and “without legal existence", Vladimir Putin invades Ukraine on February 24, using in particular his troops based in Belarus and his allies from the self-proclaimed republics in the cities of Donetsk and Luhansk. This "special military operation" must serve to reaffirm its power in the face of a NATO presence, denounced as aggressive.

81 notes

·

View notes

Note

Different Anon but how did Kadyrov become the leader of Chechnya if he is so ineffective militarily? Is Chechnya/their military/fighters a paper tiger because apparently they have a reputation for being fearsome fighters. Was that just because they were fighting Russia or is something else going on?

He was the son of Akhmad Kadyrov, who switched sides and delivering Chechnya to the Russians. Frankly, Kadyrov these days largely is more of a marketer than a fighter, and he is a sycophant to Putin so they take every chance to show how strong he is, to inspire loyalty and fear (because they use Chechnyans for blocking detachments).

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Popasnaya // Luhansk People’s Republic

#2022 Russo-Ukrainian War#russo-ukrainian crisis#russo-ukrainian war#russian invasion of ukraine#invasion of ukraine#invasion#Popasnaya#Popasna#Ukraine#Luhansk#Luhansk People's Republic#Luhansk Oblast#Kadyrovites#PPSM-2#Kadyrov Regiment#Akhmad Kadyrov#Chechens#Second Road Patrol Regiment of the Police#Kalashnikov#AK-74#AK-74M#PKP#PKP Pecheneg#PKM#SVD#SVD Dragunov#Dragunov#GP25#rifle#carbine

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Graduation Day

The two-week accelerated tactical and weapons training courses for the latest group of volunteers at the Russian Special Forces University @ruspetsnaz in Gudermes have ended.

The soldiers, who are from various regions of Russia, are full of determination and ready to join the battle for truth and justice on the territory of Donbass and Ukraine.

One more flight headed for the site of the special…

View On WordPress

#Abuzaid Vismuradov#Akhmad Kadyrov#Apty Alaudinov#Chechnya#Magomed Daudov#Ramzan Kadyrov#Russian invasion of Ukraine#Russian Special Forces

0 notes

Photo

A man cleans inside the Heart of Chechnya - Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque, one of the largest mosques in Russia, in central Grozny on July 26, 2017.

Kirill KUDRYAVTSEV / AFP

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

#Abu Derwish Mosque (Jordan)#islam#islamic wallpapers#Abuja National Mosque (Nigeria)#Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam Mosque (Suriname)#Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque#Al-Azhar Mosque (Egypt)#Al Fateh Grand Mosque (Bahrain)#Al Nida Mosque (Iraq)#Badshahi Mosque (LahorePakistan)#Baitun Noor (Canada)#Blue Mosque (Armenia)#mosque in world

1 note

·

View note

Note

Aren't ichkerians (chechens) the ones killing gay people..

Hi Anon!

Thank you for raising this question, I feel like it's very important to clear this topic.

But also disclaimer: I'm obviously not a chechen, so i don't feel like it's my place to speak for people of Chechnya, but i really, really want to defend them against these accusations. If any chechen person will read this and wants to correct me on anything, please do not hesitate.

So the short answer to your question is no, it's not chechens who are killing gay people, it's Kadyrovtsy. 'Kadyrovtsy' is special paramilitary organization named after Akhmad Kadyrov. Akhmad Kadyrov used to be a revolutionary who fought against russians during First Chechen War for independence of Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. But when the Second Chechen War started he switched sides and started to work for russian government and killing his own people. If you know anything about Chechen Wars, anon, you know they were inhumanly brutal. And sadly chechens lost in this war and a lot of civilians and chechen warriors were killed.

Now let's get back to Kadyrovtsy - they were men who followed Akhmad Kadyrov after his betrayal and they were the ones that terrorised chechen people into submission after the war was lost and Akhmad Kadyrov was appointed President of Chechnya.

Nowadays, Kadyrovtsy is basically private army of Ramzan Kadyrov (Akhmad's son), who now kidnaps, tortures and murders anyone Putin's lap dog points at.

Chechens consider Kadyrovtsy traitors of their nation, but are still subjected to live under their terror that russia finances.

It pains me deeply, that people see kadyrovtsy and chechens as one, because that's so far from true. Chechens are in fact brave, honourable people who to this day keep fighting russians in any way they can ( a lot of chechens are fighting in our war too on ukrainian side since 2014) and still hoping that one day free Ichkeria will rise again.

I believe in it too.

P.S. Anon if you are interested read about Johar Dudaev, he was first elected president of Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, killed by russians because he was a true leader of his people. Don't think about Kadyrov when you hear 'chechen', think about Johar Dudaev.

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Children study chemistry at a school named after former Chechen leader Akhmad Kadyrov in Grozny.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque, Grozny, Chechnya

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A view of the new mosque that opened in Shali, Russia, and is believed to be Europe’s largest, on Aug. 22, 2019. The newly-built mosque is dedicated to Chechnya’s first president, Akhmad Kadyrov, father of the region’s current leader Ramzan Kadyrov. (AP Photo/Musa Sadulayev)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Issues To understand Right before Going to Chechnya

Chechnya is currently one of the safest places in Russia. But be cautious, you still really have to brush up with your expertise in Chechen culture and traditions ahead of browsing there. If you want to go to North Caucasus or other special international locations, you'll be able to visit our web site. You may also join our Somaliland Tours.

Could it be safe and sound to visit Chechnya? Indeed, but keep in mind this is actually a conservative location by using a Muslim populace. You cannot act like you're on an island getaway - fights and pleasure usually are not in the slightest degree tolerable. Community police officers will always be polite for you, however they will never hesitate to show your arms driving your again and handcuff in case you cross the road. In Chechnya, the police are armed with AKs and pistols and they know how to use them: for several years the territory was destroyed by a war among terrorists as well as the Russian governing administration. So, to become safe you shouldn't get drunk. Liquor can be prohibited in Chechnya.

There are two tips on how to get there. You can consider direct flights from Moscow to Grozny from Vnukovo Airport, and planes fly back again and forth twice a day. Otherwise you can refuel the vehicle and start a highway trip. Grozny is one,850 km south of Moscow and in contrast to most other strains during the place, the route works by using new streets. This journey will consider you thru towns like Voronezh and Rostov-on-Don, so you will also see the Russian province with all its splendor.

To be a region with a dominant Islamic populace, Chechnya has some special procedures for apparel. A girl ought to not demonstrate her henchmen brazenly. For men, remember another thing: Don't don shorts or fancy shirts.

You won't come across liquor, cannabis, even cigarettes and things such as that in Chechnya. Things like that cannot be discovered even in luxury inns and restaurants - yet again, as a consequence of Muslim tradition. Getting no other decision, locals tend to reside a balanced way of life and revel in sports activities, lifestyle, weapons collections and touring.

Should you like cultural situations, check out the Central Theater as well as the most important mosque within the location: the Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque, or maybe the official Serdtse Chechni ("Chechen Heart"). Each are located in Grozny.

You will adore Chechnya in the event you like weapons. Chechen chief Ramzan Kadyrov personally monitored the development of Russia's Spetsnaz University, that is devoted to teaching unique forces. It can be situated 33 km outdoors Grozny, around the town of Gudermes.

Components of the university heart are under design even so the taking pictures range is open towards the community. You are able to shoot everything you wish, from pistols to significant device guns and grenade launchers. Just after building is finished in 2020, you may be able to shoot underwater as well as tame mines (should you are desperate).

In addition to capturing and blowing up matters, we advise you go mountaineering. For those who like camping, going for walks by way of the forest, and climbing mountains, Chechnya will be the ideal area. Start at Grozny and journey in any path you prefer.

1 note

·

View note

Text

جدید طرز تعمیر کی شاہکار دنیا کی بڑی مساجد

#World#Sheikh Zaid Mosque#Prophet Mosque#Muslim#Masjid al-Haram#Islam#Biggest Mosques in the World#Beautiful Mosque#Al-Aqsa Mosque#Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque

0 notes

Text

Main mosque of the Chechen Republic

A man rides a bicycle during a snowfall, as the main Mosque is illuminated for New Year celebrations in downtown Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, Russia.

0 notes

Text

9 Mei 2004: Pembunuhan Presiden Chechnya Akhmad Kadyrov dengan Bom Ranjau

9 Mei 2004: Pembunuhan Presiden Chechnya Akhmad Kadyrov dengan Bom Ranjau

9 Mei 2004: Pembunuhan Presiden Chechnya Akhmad Kadyrov dengan Bom Ranjau

Akhmad Kadyrov (kiri), dan putranya Ramzan Kadyrof (kanan)

Presiden Chechnya Akhmad Kadyrov yang menjabat sejak 5 Oktober 2003 terbunuh pada 9 Mei 2004, 18 tahun yang lalu, dalam sebuah serangan bom ranjau. Serangan terjadi saat ia sedang melakukan parade Hari Kemenangan Soviet pada pertengahan pagi di ibu kota…

View On WordPress

0 notes