#Andy Merrifield

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Each of us is a traveler in the wilderness of the world."

— Andy Merrifield, The Wisdom of Donkeys

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonfiction Book Review: The Amateur by Andy Merrifield

Oh, hey. I do book reviews now. Here's a nonfiction book review of Andy Merrifield's "The Amateur," a book about loving the things you love to do without needing to monetize it or build social status from it.

“Ordinary citizens would do well to cast a critical eye over the doings of our professional democracy. One issue is how the proving amateur today needs to be a sophisticated forensic scientist, a skilled lawyer and an able accountant—if only to keep track of all those professionally negotiated contracts and secret equations, those abstruse labels and reams of legal small print.” —Andy…

View On WordPress

#andy merrifield#philosophy#political theory#politics#the amateur#the amateur Andy Merrifield#the amateur by Andy Merrifield

0 notes

Text

This week in baseball, Connie edition

April 20

~ Cody Bellinger's pants ripped.

~ Andy Pages scored his first run in his major league debut, thanks to Austin Barnes' RBI.

~ Ian Happ hit a grand slam.

~ Kyle Schwarber hit his 250th career home run.

~ Jack Leiter, pitcher for the Rangers, made his debut Thursday. Jack's father Al was a pitcher once upon a time, as was the father of Jack's cousin Mark Leiter Jr. (who currently pitches for the Cubs), making Al and Mark Sr. the first MLB brothers whose sons would also join the MLB.

~ Whit Merrifield hit his first homer as a player for the Phillies. And in the new City Connect uniform, no less! Good for him.

If I missed anything, feel free to let me know.

#cody bellinger#andy pages#austin barnes#ian happ#kyle schwarber#jack leiter#chicago cubs#los angeles dodgers#philadelphia phillies#texas rangers#whit merrifield#twib connie edition

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the practico-inert and you: an experiment in attention

I’ve been thinking a lot about place recently. It’s the beginning of the rainy spring in Mie; I fumble with my mask and glasses as I shake off the drizzle I underestimated on my bike ride to school. When it’s not too wet on my way home, I ride past my apartment to the small cherry blossom orchard next door to check on the blooms. They’re in varying stages of pink and white flowers, and they’re all wet. Mesh baggies of oyster shells hang around the lowest branch of each tree. I have yet to figure out why, but a friend floats the idea that the minerals from the shells might serve as fertilizer that runs down the trunk of the tree at exactly this time of year, when the rain is constant and the peak bloom is any day now. On days like recent ones, I watch the rain flow for a little bit, and think about the craggy surface of the shells, miles and miles from the ocean, feeling the water in their crevices. I think of how they might feed the tree, helping it push out every last flower, stretch open every pink bud. This, too, is place.

This porous, soft body has me somewhere in it, but I am just its occupant. I am made from place in every breath, every step, every night when I lay my head down. Henrik Karlsson described this in the broader sense as milieu¹, or the culture contained in your unique set of connections. It is an individual configuration of connections to flows of information, emotion, art. In this way, it is beyond the blanket term of ‘culture’, and hones in on individual relationships with all nodes of information. He names a few examples: your Twitter feed, your friend group. To me, milieu as a framework for understanding input attempts to put name to the Sankey diagram of an individual’s relationship to information: what comes in from where? How much of the whole does it make up? Where does this input go? Karlsson takes this term and uses it to the curation of taste, but I was compelled by the milieu as an environment, a physically and digitally mediated place where words become the substance of skin, music leaves behind spotted freckles on it, someone’s unkindness makes bones ache like incoming rain. Undoubtedly, place is just one element of a milieu, but recently, it seems to have been making itself the most clear to me. I live in a place, as do you, and that place lives in us, too.

A few years ago, I read Marxist Andy Merrifield’s formulations on the bounds, both physical and metaphorical, of urban space. Merrifield argues that the city is a practico-inert, a Sartrean concept described as a set of material conditions created by intentional human action towards a set of goals, ‘praxis’, with which new, continuing praxis must contend. This idea argues that the outcomes of action are not built on neutral foundations of naturally arising systems; rather, they are often in tension with the results of past action, even that of supposed social progression or development. In the contemporary era, an obvious example is climate change, the conditions under which processes of capital, industry, and production towards an ostensibly ‘better’ life have exponentially sped up the decline of the environment, turning its decay into the new arising social condition that the most urgent innovation and intervention must address. Whether intentionally created or not, these conditions frequently become the site that new, immediate intervention must attend to, usually working in contradiction both morally and practically to the initial set of goals or ideas. The site that most urgently demands action is the result of past action for change.

Like this, Merrifield says, the city no longer serves the needs of the people it was created for. Namely, the labor of the dead is dominant over living labor as manifested in the physical structures that govern urban spaces, like bricks and mortar, systems of transit, and what he describes as a ‘million-fold mass’ of people “such as never existed before, a flow of dynamic people who soon become passive vagrants, unemployed, sub-employed, and multi-employed attendants, trapped in shantytowns, cut off from the past yet somehow excluded from the future too, from the trappings of ‘modern’ urban life; instead, they’re deaded by the daily grind of hustling a living”.²

When I read this, I was finally able to understand what Sartre meant when he said that the practico-inert is necessarily physical. To people like my parents, the city and the practico-inert are fundamentally inseparable ideas of outdated labor, alienation, and dispossession, to which they responded with finding another built prison of potential action – moving to the suburbs. To young, socdem art-type people graduating debt-free from elite universities, the city is a place of infinite potential, a place to simultaneously revel in and revolt in the fact that thousands of others are attempting to experience the same jungle gym of guerilla living promised of early-twenties urbanism. This difference, which had previously always been a funny musing, transformed into a slightly unsettling realization that the way that the built structures of the city impose themselves on people are always totalizing and neutralizing, and the difference lies instead in the individual’s attempt to contend with some sort of urban future. In both cases, the city’s characteristic inaccessibility is so fundamental to its continued operation that they become the terms that most urgently need attending to: the housing crisis, landlordism, displacement, wealth disparity. In short, the city is practico-inert: a structure arising from human action towards a goal that is no longer attentive to the needs it was originally created to serve.

The city would then come to be a place I found myself thinking about a lot. After reading a little more about the practico-inert, I had originally set out to use it as a personal analytic with a focus on attentivity, the core of what makes the praxis active or inert. I began this exercise attempting to make a list of metaphorical structures that I’ve identified in my life that no longer serve me but I remain tied to, essentially aiming to strip the practico-inert of its economic foundations and just use it as a tool for a thought experiment. What are some values that I’ve worked to embody that no longer serve my needs? How do these values capture my attention in a way that is not useful?

The metric of ‘values’ worked easily on the personal level – I could already imagine discussing my former extroversion, my once-diehard belief in the project of diversity, my relationship to the Internet. But these felt flimsy, and easily dismissed as a thing of the past based on my own whim to decide whether or not I still ‘felt’ that way, a sentiment that could be assessed in a single moment and change from one to the next. Their effectual presence in my life was a yes or no. Any true structural prison – to Sartre, only then truly revealing the conditions in need of urgent praxis; to Karlsson, only then acknowledging the new relationship to place beyond merely people or things – would take more effort to reveal and would be much more threatening because they are not easily demolished, just as bricks and mortar, steel and I-beams, manhole covers and sewers.

I don’t currently live in a city, if taking the conventional definition, but I certainly used to. Merrifield’s analysis of the city as a prison of past action resonated more than I had anticipated. Power, capital, and governance in the city are already overwhelmingly powerful to the average person, but what about miles and miles of metal, stone, and steel? What about eons of highways, cables, and displaced space? Are these not equally as immovable and totalizing? From here, I turned towards the material analytic. The material condition demanded consideration just as much as the patterns, behaviors, and practices that came from it. Essentially, doing this project had to suck, otherwise it wouldn’t have really been done. I had to be mean.

Like any good researcher, I began at the archive. I started by flipping through old journals, scrolling through old Tweets, finding fragments of thoughts in my Notes app, even combing my Google search history. I meditated. I read Trick Mirror. I went to White Stone. What I found by actually gathering some thoughts is that any pattern that I could identify was eerily iterative of the city’s role in my life, sub- and sub-sub-categories of my experiences in the city stemming from both time spent living in one and time spent in a stratified relationship to one in time and space. I ended up with a handful of spare-change reflections, none really satisfying without the context of the built environment(s) that raised them. It wasn’t possible to take on the analytic of the practico-inert as a metaphorical, abstract reflective project because I kept returning to the same handful of undeniably physical structures, all grounded in my relationship to urbanity: motions, places, things, a cruel version of all roads lead to Rome. The items on the list that I will attempt to articulate occupy both the purely economic, physical, built environment prison of past action, and the self-helpy, ‘bad habits’, abstracted trap of habit where all afflictions are deeply individual – a flagellating look both inward and outward. What places live under my skin? What do they do there? Are they welcome?

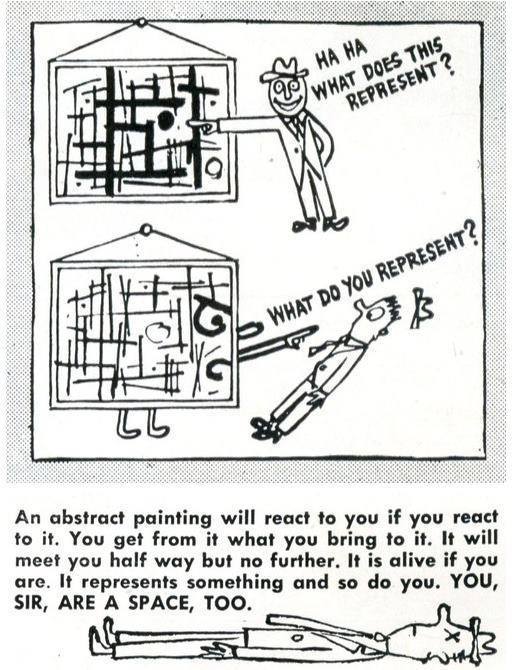

Ad Reinhardt, from 'How to Look at Art, Arts & Architecture', 1946

I identified these based on the criterion of physicality and attentivity, both important to the analytic of the practico-inert with the former being material conditions and the latter being the ability of those conditions to change and respond. In other terms, I forced myself to choose objects or practices that are a) strictly material, b) I spend a lot of time thinking about, either willingly or unwillingly, and in order to keep this grounded in some sort of personal reflection, c) I rely on for a non-essential project of identity, self, or general indulgence. This exercise in itself – listing, writing, reflecting – is an attempt to reorient the attentivity of these structures.

Karlsson, 2022 – First we shape our social graph, then it shapes us https://www.henrikkarlsson.xyz/p/first-we-shape-our-social-graph-then (thank you, P)

Merrifield 2011 – The right to the city and beyond: a Lefebvrian re-conceptualization

The city

I’ve already gone on about the city, but I make the most sense to myself when speaking in specific terms. My dad is a born and raised New Yorker. My mom was born in Singapore to immigrants from Southern China, who then immigrated again when she was sixteen to settle in the Bronx. I was born in Hong Kong. My family moved a lot as I grew up, and I spent a handful of years each in Guangzhou, northern Virginia, Bangkok, Beijing, and Seoul. I went to college in a medium-small city in central Virginia, and visited my parents in Tokyo once a year.

These are all facts, but like many truths, they contain sub-truths and technicalities in droves. In Bangkok, and Beijing, my family didn’t live in the city-city. My brother and I were still in school, and most of the large, expensive international schools were located in the outskirts of the urban core, where they could comfortably house sports fields, swimming pools, and big homes for rich expatriates. In Beijing, the school even housed a huge structure known aptly as ‘the Dome’, an enclosed, airtight mega-facility where students could play tennis or soccer, run laps, and use the gym without worrying about the cardiovascular threat of heightened air pollution levels thanks to a state-of-the-art mass air filtration system not yet even seen in hospitals. My parents elected to live out there so that we could be close to our school and participate in the expatriate community that came with it. They instead would make the commute into the city every morning and evening. Going ‘downtown’, as it was usually referred to, was a rare breach of the expatriate bubble that surrounded my international school and happened so infrequently it was in itself a vacation. There, the ‘evidence’ that we were not the West wasn’t limited to the selection at the local convenience store or the language spoken by the service economy attending to expat whims. It was everywhere – public transit, visual culture, attitudes towards each other, urban organization, fashion, etiquette, pop culture. Notably, it was not in us. A family of Chinese Americans in Asia took on an odd quality, one that was hazy at best in our expatriate bubble but sharp and unforgiving in the city. At this age, in these places, the city was supremely unfamiliar – we literally did not even breathe the same air.

The most recognizably urban experience I had in any city I grew up in was Seoul. In Seoul, we lived on the army base¹ in the middle of the city located right next to a bustling city center of shopping, restaurants, and cafes. My commute was almost an hour by private bus provided by the school to an equally bustling part of Seoul closer to its northern boundary. As I came into my independence as a late teenager, I came to know the city in two distinct pockets, categorized into ‘places near home’ and ‘places near school’. It was between these two frames that I started to negotiate the extent to which I was recognizable to myself – at home, I was among my family, my parent’s coworkers, and other expats, exchanging Americanisms, but at school, I was with friends and classmates, made up of mostly Korean Americans that tended much more to Korean than American. There was an invariably small overlap between these two groups, the residents of which I avoided desperately. I wore these two hats with a sense of urgency.

Everywhere else in Seoul, I was free to be no one, helped along by a growing allowance of independence and a determination to shoulder my way into becoming a real person. In the winters, I rode my longboard along the Han River to catch the early sunset over Dongjak Bridge, dodging old men on in-line skates and expensive bicycles, and be back home in time for dinner. In the warm spring, my friends and I would cut school early, make a Ghibli-esque trek across a wooded back-area of the school grounds, beg the guards who video-monitored the back gate to open it for us, and emerge onto the campus of Yonsei University to eat cold noodles, button-mash at arcade Tekken machines, and play pool. Unlike previous experiences of living in cities abroad, I felt like I could say that I really lived in Seoul, despite barely understanding any Korean, never working, and attending an English-speaking school. To this day, I remember Seoul so fondly it stings; in college, I called it my hometown for an embarrassing amount of time before realizing that most people took this to mean I was an international student, and dropped it.

My first time moving to a place that was both a non-city and a non-suburb-of-a-city was when I moved to the US to go to college. In my first year, I was less than 100 miles away from the place I had just finished spending eighteen years of my life telling people I was from, and had never been so homesick (and insecure about being homesick) in my life. That first fall, despite my desperation to enjoy college, I put a countdown timer on my phone that ticked away the days until my flight to Incheon and laid in my dorm room until it got to zero. At home, it was like nothing had changed. The unpleasant growing pains of first year were literally an ocean away; I drank, ate, and played pool with my friends like the last four months had been a glimmery hallucination. Despite seriously considering otherwise, I returned to college for the spring semester, and things shifted slightly into a more tolerable peace. In the summer before my second year, my parents moved to Tokyo, but the feeling remained that I was returning to something that was home, or a gossamer, refracted version of it. When I started to look forward to winter break, it was a desperation to get back to the city and reconnect to myself in a way that I was starting to rely on having regular access to – home was meditation. This, combined with the rare experience of being so near my parents again after a while, shaped these weeks and months into a time outside of time. When it was time to leave, the semesters that stretched in front of me felt measured in gaps between ‘now’, and ‘the last time it was now’. A few weeks of acclimation back in Charlottesville later, I wouldn’t have even known what you were talking about.

Now, when my friends talk about the city, they do so with a hint of reverence. Seattle is like this, the Upper East Side has that character, LA is so that, the Bay Area is this way. I’m guilty of this too². When a certain urban quality comes to precede a city, and the urban quality precedes the self, staring yourself in the face seems a lot less necessary³. Even a certain outfit set in different backdrops can say wildly different things about a person’s personal wealth, sense of self, educational background (think Dickies overalls, an hour south in Orange or in a boba shop in Annandale). The things that set cities apart from one another innately present some information about the gaze that is taken upon it, which in turn shines out of its residents in equal abundance. To know these differences and be able to talk about them in the weird sort of lingua franca of the well-traveled coastal elite is to learn an entirely different lexicon, and it’s one of money. These qualities have been intentionally scrubbed from the suburbs to create a uniform experience where everyone can be white, everyone can be American, and everyone can forget where they might have lived before. In contrast to urban character, suburban character seems more insidious. I don’t know anything about the history of the house, neighborhood, or county where my family lives. There’s no character to take on, no place to project identity, and no reason to. I cannot help but feel that this is intentional. Do the senators and politicians who live in my neighborhood and surrounding areas know the history of this place, as they govern districts and states miles and miles away?

Here is the point I am leading up to: in the aftermath of this pattern of visiting home, where I was neither really just ‘visiting’ nor ‘going home’, the city – any city – feels like pilgrimage. It is a grand return both to the place itself and the person that I am while there. In my winters in Tokyo, surrounded by the concrete jungle gym of a city that positioned itself supremely important, I felt, at times, like a torso. If I kept moving, didn’t become a regular anywhere, and didn’t make any huge social faux paus, being in the city let me feel like I could have no identity at all – if I kept my mouth shut, I wasn’t even a woman or an American. I revel in the feeling that I, too, could be absorbed into the fabric of an ever-changing urban entropy that had always been intimidating, and through this even become unfamiliar, new, enticing to myself. I was entranced by the idea of feeling or acting like I blended in, as if a certain urban character was as much a resident of me as I was of it, and it would shine out of me even when I left just as long as I absorbed enough of it, learned to take it on. At the same time, any wrong move would expose the ugly tourist living beneath my skin, the embarrassment of non-belonging, the disjointed transplant. Being from nowhere in particular is a familiarity with many places, but it’s also a deep disfamiliarity with every place, home or not. This is what I will call practico-inert: I crave the city for its anonymity, centrality, encounter; I am impassively estranged from the relationship that people have to place despite being desperate for it.

It’s wishful thinking to imagine that this is a unique feeling. And just as everything is embarrassing, I am embarrassed by how much I feel like myself in the city, and yet how self-absorbed my obsession with the ability to not be self-absorbed is! I’m more than aware how much I sound like the joke about the ‘returned from study abroad, or the ‘just moved to Manhattan undergrad’. But the truth remains that I like who I am more in the city, and the unrecognizable me(s) that still live there even after I have left. I can be an orbital cloud under balmy blue skies in Apgujeong or a vampire flitting around bookstores in Meguro, all in the same pair of sneakers. These people feel like reflections of my inner life, like I can start to match up the person that I’d like to feel like I am with the character that precedes a place. However, it’s also not lost on me that Korea and Japan are some of the most homogenous countries on Earth, and I happen to match the dominant look in either place, affording me a certain privilege and baseline ease that I don’t experience in America. In a roundabout way, the anonymity of the city is an escape from the exact type of narcissistic self-hate that I suffer from: I don’t have to stare down the barrel of everything I have decided that I am and am not if I can put on a hat and go for a walk and not be that person in public for an hour. It’s a respite from the project of identity.

That summer was the last time I will live in Tokyo for a while. I spent some of the hottest days of the year on park benches devouring words, steam-pressing images into the back of my eyelids, and downing conbini ice cream and canned beer. That month, I made three friends. I didn’t learn much Japanese. It felt like worship.

“Instead, centrality is always movable, always relative, never fixed, always in a state of constant mobilization and negotiation, within and without any movement. It’s a kind of centrality that is the nemesis of centralization with its totalizing mission of domination and control; it’s not so much about occupying a center as creating a node, a node that represents a fusion of people, and overlapping of encounters, a critical force inside that diffuses and radiates outwards; rain that creates its own tidal wave.” (Merrifield, 2012, p. 276)

This is an entirely distinct experience of neo-imperialist American shame that requires its own piece, and probably another few years of percolation.

I’ve always been amused by the difference in thought in regards to the city as exemplified by young people, for which the city can be a sandbox of art, food, fashion, and drinks after dinner, and my parents, one a born and raised Chinatown Manhattanite and the other a product of the Bronx, for which the ‘city’ represents the impoverished foundations upon which bootstraps-were-pulled-up-on to the suburbs of Northern Virginia. I reveled in this disparity in some part as self-soothing mental stimulation to erode the reality that I could not independently afford to live in New York City, even if I wanted to, for years, and that if I ever do move there I will be just another young privileged face in the wave of gentrification and displacement, another inconsequential neuron firing in the empty head.

I called C the other day, from the break room next to the teacher’s office at my school. I jotted grammar points in Japanese as we talked about our lives. When I tell her that the honeymoon period of Japan is starting to wane and I need to look for a new hobby, she laughs. She says that living somewhere new is just being annoying about that place for six months and then moving on. I feel seen.

In the car

Thanks to the great endeavor of my parents, I was never truly in charge of my own life or death in a meaningful way until I got my first car at 20 (not coincidentally, also thanks to my parents). My mom recalls that time as the most nervous she had ever been in the four years we lived across the world from each other. She told me she was often unable to sleep if she knew I was driving a long distance until I sent a text that I had arrived safely. My burgundy red Honda Civic and I would drive almost thirty thousand miles together in three years in a variety of settings, ranging from rush hour Manhattan to the one-light towns of central Virginia.

In that car, I experienced three traffic incidents (two at-fault and one not, only one requiring any repairs) and three tickets (two speeding, one parking). The traffic incident I remember the most took place in the early spring of third year, while I was making the long Sunday evening drive back to school from Fairfax. I had spent two hours either white knuckled behind the wheel in NoVA traffic or bored to tears on the long straightaways of 29. As I pulled onto JPA, a police car turned on its lights and started following closely behind me. Without a street space to pull into, I drove until I could pull off onto a side road and turned on my hazards with my hands on the wheel. The middle-aged white officer berated me for taking so long to pull over until I was crying silently (‘Do they teach you that in driving school? To keep going like nothing’s happening when you see police lights behind you?’), and then wrote me a ticket for $50 which I was too scared to go to court for. Over the next two years, JPA would prove itself to be a site serving many strange purposes (the resting place of a decaying skunk, the setting of a poorly executed hate crime, the open-air hallway of a never-ending house party), but it would always make me prickle with nerves when driving.

The car is a practico-inert in many senses. It’s an urgent site of intervention in climate justice, urban planning, civil engineering, the average American household. But I’ll add a personal analytic to this as well, and argue that the tyrannical rhythms of the car – both concept and object, on both the micro and macro – are engraved into wide highways and country roads in my skin, and I’m only just now polishing them out months after leaving my car behind in America.

The role of policing almost feels too obvious to include here, but it’s the most logical place to start. The car, and the American place sitting in its driver’s seat, is the constant, slight yet looming, threat of police confrontation that is designed for the average driver to forget about. The traffic stop is the biggest initiator of all American contact with police¹, and is the start of one in three police shootings. In the car, I find myself uncharacteristically anxious over potentially interacting with police to the extent that it impacts my ability to drive safely, always keeping an eye out for speed traps on Google Maps or a squad car tucked into some trees on the highway. Outside of driving, I can’t even think of a close call to police interaction I’ve had in the last three years². Speeding on American roads is almost a granted, especially at just five to ten miles per hour over the limit, but it’s not lost that this makes it so that a police officer is constantly justified in pulling over any vehicle on basis of their own judgment, and any other risk beyond that an automatic double jeopardy.

Double jeopardy almost feels like the goal of highway policing. A litany of bad decisions make themselves available to me when I have access to a vehicle, including driving tired, driving while others are drinking in the car, driving through inclement weather, speeding if I’m late. A larger slice of the pie chart of possible decisions also become ‘bad ones’ when I am driving: using my phone, having a snack, getting distracted. It is so much easier to be irresponsible when operating a car than at any other time; it takes an even smaller slip of concentration, a much briefer lapse of judgment for things to go south. In shorter terms, I am never leaving more up to trust in my soft, weak body and squishy force of will than I am when I am operating a car. It’s terrifying. When I was driving regularly to commute or see friends, I started noticing how miserable it was making me because of how it primed my mood to be oriented towards complaining: there was never enough parking, I always missed a green light, traffic was always crazy. I was trying to shift from being acutely aware of every ounce of my mortality to being a relaxed, cool, fun person. This was becoming the entry point to my interactions with the world and started to take an actual toll on my attitude and footing in many socially demanding situations of both work and leisure. My car slowly filled up with junk from work, junk from eating shitty food, junk from overthinking.

I continue to be blown away at how casually friends, family, and often strangers drop their lives in my hands at the door when entering my vehicle. It’s a heavy feeling that I found hard to shake at first, and would last even after arriving at a destination safely. Part of my mind would stay outside, parked on the street, occupied with the trip home, or stuck on the things my car demanded to consume – time, attention, gasoline. Any trip on which I took my car was a trip on which I took with me the most expensive thing that I own and every subsequent liability from that. I’m a good car owner in that I’m very up to date on the maintenance and safety of my car, but I’m also aware how much of a task that is even as someone who considers themselves relatively organized. Often, it’s one that I simply can’t believe that the average person is up to all the time, making other people’s cars and driving sometimes more stressful than my own. It’s made me unnecessarily paranoid, strict, and anxious, not in a way that I think is unjustified given the reality of traffic mortality in the United States, but in a way that makes me hate myself.

In Japan, like a huge portion of the population here, I don’t own a car. There are clear outcomes to this: I’m in better shape without doing much at all, I chew through books and podcasts easily while commuting, I have not once thought for even a second about parking³. My average daily step count has more than doubled. I own a cute bicycle. It’s all very characteristic of any high-functioning train-based society, and I’ll sorely miss the clockwork of the transit systems here when I leave⁴. It’s the strongest system of public infrastructure that I have ever had the privilege of experiencing. On the other hand, I live in the prefecture of Japan that is home to the Suzuka circuit, Japan’s premiere F1 destination and a well-known attraction for car enthusiasts. The city I live in is known for its petrochemical industry and its subsequent pollution; the sidewalks are narrow and the streetlights are sparse. The auto industry in this area impacts life here down to our classrooms. Migrant workers are a strong community even in smaller towns, and many English teachers, especially in middle schools, have a handful of students who they are teaching English to at the same time as they learn Japanese by brute force immersion. Honda’s manufacturing presence in Mie and Toyota’s just a prefecture north in Aichi has made all of the Chubu region surprisingly mixed-race and multiethnic. While I may not drive one anymore, the presence and impact of cars is something that I feel every single day at work, while walking or cycling, when sleeping.

I’m not entirely sure what to do about the car. I’m certain I’ll never truly escape it. Rather than just complaining, however, there is a reason that I consider my car practico-inert, in the sense of a physical prison of past action. The material necessity of my car isn’t even something I would put up to question. Despite my overwhelming hatred for it, ten times out of ten, I would choose having a car over not having one.

In Virginia, I live in a typical American suburb where leaving my neighborhood is nearly impossible without a car. I was able to access pretty much everything that kept me sane through college and the year after through my car – my friends, work outside the home, food. I made a little money on the side during the quietest weeks of winter on Uber. I traveled up and down the East Coast with friends, alone, with family. A huge part of my job in public programming required having access to a vehicle that could haul huge pull-ups, posters, and tech equipment. My car probably saved my life ten times over when COVID shutdowns first began in Charlottesville and I was suddenly, curiously, without a place to sleep. Learning to drive the summer before and getting my car literally weeks before March 2020 saved me probably a lifetime’s worth of stress. My car made itself indispensable. It’s arguable that there’s always another direction to point fingers in – the built environment of the suburb and the lack of public infrastructure to respond to a health crisis come to mind – but I’d sooner find myself grateful for having had a car in a difficult situation than I would stick to my anti-car principles and have been totally fucked. In times where a car makes itself absolutely necessary, do you know what a little relief feels like? It feels like a lot⁵.

Yet, I still can’t quite characterize my relationship to my car as practico-inert for the reason that ‘I don’t really like it, but it’s handy!’. The truth remains that a lot of the time, I really enjoy driving. I have an emotional attachment to my car in the same way that children love stuffed toys for keeping them safe. I take pride in taking good care of my car and being a good driver. What is it exactly about the car that appeals to me so much? Why do I feel empowered by driving at speed, at operating a car smoothly, by the alone time spent driving? Why do the cultural imaginations of the great American road trip stir something in me, anxieties and dangers and headaches of the highway and all? This is what feels the most endemic about my infatuation with the car, the road, the act of driving. It’s the constant return to it and its needs, the inevitability of the car. I could accumulate hundreds of hours on foot and on bike, feel the effects on my health, environment, and attitude, and still find myself instinctually tending towards the car if the option was given to me.

At the same time, I have to ask what the next point of practice on this site might be. Does having moved somewhere with fantastic infrastructural support for non-drivers count as taking actionable steps towards escaping the totalitarian car? I would argue no, but I will add that escaping the car has not subtracted cars from my life, but instead opened up new ways of locomotion. I don’t blink at a thirty minute walk any more, know my neighborhood’s bus schedule like the back of my hand, developed an eerily familiar pseudo-social relationship with my bike (albeit a bit more wary of each other).

Not driving has brought a sense of attunement to the world that I hadn’t even been conscious of until I visited home for Christmas. Japanese people are known for their timeliness, reflected in both individual approaches to life and public transportation systems. but there’s also a more constant awareness of time that comes with living here. When the difference between getting home at 5 and at 8 is catching a bus that leaves once an hour, which is likely the first leg of several extremely on-time transports, time doesn’t slip away as easily as it would if deciding to leave was just that. There’s also always the faint threat of straying too far from home with no public transit to get home, like missing a bus that’ll get you a train that’ll get you the last train to the only station walkable to your house. While at times stressful, getting home is often as much as working backwards from a desired destination and a given time, and I’ve found myself surprisingly attuned to the spatial relationship between places, the time demanded of such movement, and the suddenly much larger consequences of losing track of time.

Attunement, in another sense, has also been to the world on the exterior of a car. Urban studies essayist Garnette Cadogan noted in an interview on the podcast The War on Cars that “[walking] was a place in which I continually meet people. I’m invited into worlds in which there is one pleasure or delight or discovery, or an encounter with another that just kept enlarging my sense of myself and the possibilities in the world. And I began thinking of walking as possibility. Because that’s what walking was—it was social possibility, it was emotional possibility, even spiritual possibility.⁶" I’ve found this, too, to be characteristic of my life on foot. Some of the things I’ve seen while walking in my neighborhood include a family of tanuki living in some bushes near an empty lot, a beautiful cherry blossom orchard with oyster shells scattered over the soil, and an outdoor tomatillo plant that I can get a decent harvest from if I can get to the fallen ones before the birds do. It’s gotten to the extent that I occasionally balk at even riding my bike, which can be too fast to catch onto the finer details of possibility⁷.

This sense of joy, encounter, surprise is irreplicable by the logic of the car. It’s a mechanically necessary slow-down, a forced thoughtfulness, a proximity to mindfulness through an organic rhythm, the ultimate relationship to the earth. I grow gratitude for each step my body allows me, stem curling up from the ground into the sole of my shoe, through my spine, and blooming out of the top of my head to shelter me from the sun.

Henry Grabar in Slate, The American Addiction to Speeding https://slate.com/business/2021/12/speed-limit-americas-most-broken-law-history.html

In November, someone stole my bike from the train station in my neighborhood (punks!!! hooligans!!!). A nice detective drove me to the police station, put my groceries in the refrigerator while they took my statement, and then took me home. He asked if I liked Shohei Ohtani. The bike was back by the next week.

I went to Costco in Gifu with my coworker and her friends a few weeks ago. We forgot where we parked and wandered the lot eating hazelnut chocolate soft serve. The familiar will make itself clear, I guess.

In the heat of August last year, there was a typhoon in my prefecture. The principal instructed us all to stay home, so I sweated it out in the disgusting apartment I had been assigned to as the storm rattled my windows. I was surprised to find out upon coming back to work that I had been charged a day of PTO. When the Ishikawa earthquake caused a runway fire at Haneda Airport and I missed my flight from Tokyo to Nagoya, I spent an extra 24 hours playing tourist, shopping, and eating in my favorite city. I got the day off for free and received plenty of old-lady cooing over my misfortune for the transportation incident.

https://www.tumblr.com/jb-blunk/677813547138498560/in-this-terrifying-world-you-continuously-have-the

The War on Cars, Episode 83: The Pedestrian. https://thewaroncars.org/episode-83-the-pedestrian-final-web-transcript-2/

Like staring at the mountains and wishing I was hiking, or seeing a cute dog and wishing we were hiking together, or feeling a nice breeze and wishing I was feeling it on top of a mountain while on a hike

My relationship to East Asia

I’ve already talked about my not-like-other-girls tendencies, but perhaps this is where that strange feeling of extremely internal, quiet insanity of girlhood comes to light: I genuinely believe that I have one of the worst cases of carefully managed, suppressed NLOG-ism possible. I will push myself to be specific.

I sometimes relish the fact that other Asians are surprised to find out certain things about me. One such thing is that I am a fan of K-pop, another is that I was in an Asian sorority in college, one more is that I’m ChinAm. It makes me feel like I’ve done something right, like I’ve successfully dodged tropes and have emerged as uncategorizable and unrecognizable, the Best Asian, made up of vagueness and blurry cultural lines that I can keep in my pocket until it’s the right type to deploy them. I enjoy this feeling. It makes me feel important. In much ruder terms, I think I have a tendency to like to be right by means of other people being wrong, to derive some of my sense of self-worth from not being the person that people perceive me as. I joke with my friends that the worst part of being a K-pop fan is other fans, and there’s more than a grain of truth here: some of the most fun to be had in K-pop fandom is pointing and laughing at people who are crazier than you, including, sometimes, past versions of yourself. There is something so evilly satisfying about not being other people. These people, more often than not and including myself, are Asian Americans who for some reason I cannot help but judge for being Asian Americans in ways that are exactly predictable: in fandom, in social organizations, in friend groups, online. Terms like boba liberalism, all-Asian friend group, soft cultural power whiz through the ticker tape in my brain like the endless, hungry feed that it is, algorithm-ed and gameified to either like or hate, be or not be, participate in or reject.

If this entire tirade screams of internalized racism to you, fret not; the thought has occurred to me, too. I understand that tropes about types of Asians are meant to take them down and make them understandable, even ones that circulate internally to those groups. My distaste for parts of Asian America is a hatred of something that I see reflected at least partially in myself. However, instead of internalized racism, I’ll offer this indictment of myself that I believe is much more accurate, and to me, much more cruel: I have clung onto my relationship to East Asia for years past its expiration date.

Again, I will push myself to be specific. There is something shiny, brief, and shameful buried in the heart of the way that I think and talk about my experiences in East Asia. I am deeply, fondly attached to the years that I spent there as a teenager. Perhaps it is the red-cheeked shame of still feeling like I struggle to talk about privilege despite a plethora of examples and opportunities that would lend themselves to my case; perhaps it’s also the neocolonial conditions under which I’ve been able to gain intimate access to so much of East Asia. The fact remains that I can attribute so much of who I feel I am to the way that I was raised by these places, and I don’t know if I like that about myself. This sense of self feels very extractable; like it’s something that can be taken away if I were to settle down, or pursue something I find uninteresting, or let those times fall away in importance. I feel deeply, weirdly protective of the years and months that I spent in Korea and Japan. I don’t know if it’s the typical yearning for places that I once loved, or a specifically pathologizable dependency on that time as defining characteristics of my personality¹. Something about the times that I spent as a high schooler feels like the last time that I participated in something wholeheartedly, fully believed in something (the future, perhaps, or maybe myself), and wasn’t nonconsensually critical about my relationship to the world. I don’t know if this is more defined in contrast to a subconscious, post-COVID mourning, being a femme, or another casualty of being an NLOG, but I cannot tear my eyes away from these memories, experiences, and places as something that is possible; I find myself thinking of them in the same way that I used to let influencers, friends, and celebrities worm their way into my head on the pipeline to obsession. Sitting around and idealizing about that time is it’s own activity at this point². The thought makes me feel like my teeth are rotting. I think that this nostalgia is what feeds the flames of discomfort I feel about my place in Asian America.

My interests in pop culture coming out of East Asia are a big part of what I feel like my time growing up in Asia left me, along with a sloppy fistful of a few different languages. But, I’ll also acknowledge that these interests are entirely aligned with current Western media consumption fetishes focused on Korea and Japan. I’m a die-hard K-pop boy group stan who has been in it for so long that I’m stronger in Korean than I am Japanese several times over (and I only live in one of those places!). The time I spent living in Korea was on the occupied land of the American military, both representative of a history of imperialism and actively participating in it. I went to an expensive private school on the government’s dime where the vast majority of students were the anchor babies of eye-wateringly rich Korean American families who wanted their kids to have a better shot at entrance to American colleges. I’m currently a first year participant on the JET program, sending thousands of Westerners and English-speakers to different cities and towns across Japan to work in public and private schools in the name of soft power cultural exchange. It’s not an exaggeration to say that a vast majority of people on this program are people whose interest in and understanding of Japan began (and frequently, ended) with anime, video games, and other post-war mass cultural exports. I, myself, won’t try to pretend that having spent time here before makes me any better. For me, to have lived in Korea and Japan was to consume them, and the taste is unpleasantly reminiscent of the metallic, violent things that America and Japan have consumed too. In this way, too, my relationship with East Asia feels unsatisfying, but perhaps to wish otherwise is to wish for ignorance.

If I attempt to cut to the heart of what I feel, I think it is this: I have hung my laurels for so long on a specific, personally-and-politically fraught experience of living in Asia and the experiences that it has provided me that I’m not sure how to be a version of myself that I like without setting that person against others. I understand what a terrible thing this is to say, and at the same time, I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to meaningfully articulate how much I mean it.

It feels silly to say, but my parents leaving Asia to move back to Virginia last year left me with a pang of uneasiness. My own position as a diasporic subject has always been defined by space; when I was younger it was by living in Asia in places I both did and did not have a diasporic connection to, in college it was by visiting my parents frequently and the small but strong Asian American network I was building. I would always have my ties to the physical land of Asia as my leg-up experience, somehow always orienting me differently to the core of Asian American discussions and topics. It was a huge part of who I was. Since my parents moved back to Virginia, I find myself wrestling with the thinner, ground-floor terms of diaspora that I haven’t had to before. What once felt just like discourse is now the reality that my family is learning how to deal with – microaggressions, regular aggressions, language loss, access to traditions, aging relatives, changing family structures. It was easy to think of smelly Asian food in the cafeteria tropes as just that when they were only ever happening miles and miles away, in a culture that I knew was supposed to be very much like my own but was not. Now, I worry about my parents when they FaceTime me from their drives up to New York City Chinatown, I don’t laugh when my dad tries to tell me a funny story about a racist guy in Wawa. I feel like I’m experiencing a delayed puberty of the very basic ‘growing up Asian in America’ – my NLOG factor has evaporated, if you will, and I’m left to define what it means to be like exactly other Asian Americans when I so often (problematically) set my stance against them. I’m occupying the position that I so often intentionally misunderstood.

It feels cruel that my mind is so occupied with a place that I no longer have a neat, agreeable relationship to. My family belongs to the early end of Chinese immigration to the United States, pre-1965 and working class. We have no family or holdings left in China – the farthest extent of my family network now lives in Long Island. Since my parents moved back to the US in the summer of 2022, I’m struggling to renegotiate the new geographic, spatial, and familial terms on which my personal experience of diaspora rests. I find myself craving words from others who have tried to make sense of their relationship to homeland, which read differently than they used to as I flounder to find something that feels satisfactory. This is what I would come to identify as practico-inert: I developed so much of who I thought I would grow up to be off a relationship to East Asia and my experiences in those places that I’m no longer sure how to not fall back on the ideas of ‘space’ and ‘time’ to think about who I am, and by extension, how I relate to other people, especially now that that relationship is changing.

I wrote much of the above before I moved to a small industrial city in central Japan on the JET Program this past summer, which slowly helped hammer back many of my NLOG tendencies back into their comfortable, sun bleached spots, hiding that there was ever anything wrong to begin with³. I’ve enjoyed myself immensely during my time so far, but I still find myself drawn to the same questions of place. I don’t see myself living in my area long term, but also can’t fathom going back to the US anytime soon – there is still so much to do here. Japan is safe, convenient, and easy to live in. I enjoy the pop culture and have been given opportunities I couldn’t even imagine back in the US. In the same breath, I miss English speaking friends who I feel like I can match in every sense instead of just a few and a language, I miss my family. I want to make more money, I want to be in community with more queer people. I want to live five thousand different lives. In short, I have no idea how I’d like to sort my relationship between home and home, a refrain repeated over and over in the body of Asian American literature and media. I have a hard time treating my time in Japan as real, and the life that I am building here as an actual reflection of the way I will shape my twenties and beyond. This, too, is part of the escape of my relationship with living in EA that I have to contend with now that it is of my own choice and volition to do so, and now with the experience of the US under my belt.

As I transitioned out of working in Asian America in the referential sense and into what feels like working in Asian America in a literal sense, I’ve come to realize that to me, Asian America is much more interesting as a stance than as a subject matter. I’ve gone on a strange personal journey from finding Asian Americans cringe when first encountering them en masse at UVA to really staunchly standing by standing by them (to the extent of taking not one, not two, but four jobs in AAPI), to finally settling on a begrudging acceptance that the sometimes interesting, sometimes embarrassing fabric of being Asian American in public is just the way that things are. I’ve felt more moved by the kinship that being Asian American has allowed me, both here in Japan and in college, than I did in my year actually working in the field. Asian America can feel flimsy at times; my friends and family are perfect, robust, eternal. This, too, may be borne out of some unsettled place: I’m afraid that the subject matter approach will spend too much time trying to sift through the clumpy litter box of identity and come up with the slightly scary notion that the material of Asian America is, in truth, not much substance at all, a mosaic of borrowed difference that doesn’t reveal itself as nothing until the dust is blown off, and the tradition itself floats away with it.

The idea that I might have dedicated my life’s work to something that I’m not really sure if I really care for is both a reassuring and frightening thought. After having moved, I keep looking over my shoulder at Asian America, as if playing red light, green light. If I don’t look, will it change? Will I turn around one day and find myself staring back? Will Asian America catch up to us? On the other hand, my job now feels like the most derealized I have ever been from any concept of complex public identity: I am an American talkbox who has a mastery of the English language, and for that, this box must talk⁴.

“Remember: home is

not simply a house, village, or island; home is an archipelago of belonging.”

From Off-Island Chamorros, Craig Santos Perez

I’ll also recognize that I haven’t had quite the amount of years beyond them that I will have after I return from Japan for a second time, so it’s a bit hard to tell if I will romanticize these years specifically or just constantly yearn after my late teens and early twenties until I mold over.

See Liz, on yearning.

The NLOG factor, here, is one that I was raised in: it is being a foreigner who doesn’t look it in Asia, what I once saw termed as a ‘hidden immigrant’ (ew) in a book about third culture kids that seemingly was trying to give people a term to rally around.

I was asked to put together a presentation on fall activities in America, and found myself haphazardly Googling Virginia tourism websites. I ended up showing a historical reenactment video of a bunch of kids fake-dying from plastic rifle wounds in Jamestown, just because I thought it would make the kids laugh. It feels weird.

I am determined to deserve something

Recently, I was at an event that I considered myself exceedingly fortunate to be at – perhaps one of the only things I’ve ever participated in that I could truly consider a once-in-a-lifetime experience. The entire time, the two things that I felt were close to tears and why me? What could I possibly have done to bring me to this point? How did the spaghetti of life choices and decision trees have led me to this point? I’ve never thought of living this way.

I don’t not believe in cause-and-effect relationships, but there have been more than a few moments in the past year that have left me questioning if there is really such a relationship that can define two abstract items in time and space as a ‘cause’ and as an ‘effect’, in matrimony of opposition to each other. It feels vain to imagine that a mental connection that I might draw between two things could be anywhere near a reflection of a reality that often feels too complex to even participate in, let alone draw conclusions about. Attempting even more than two things feels like a farce. Infinitely many things are true at the same time, and these things are often in contradiction, in moral opposition, producing outcomes where it seems like none should occur and withholding them when they should be obvious. To leave the job of attaching red yarn between events to humans is a Sisyphean cosmic prank, frankly, and I’m sometimes left gawking at my own daring to even try.

I’m not sure where this instinct to believe in a logical world comes from, where karma functions like a machine, actions have direct consequences, and the idea of justice can be followed to a T. This has never really been true on the personal nor public scale. This ambiguity can be beautiful, and the gaps between truths are the spaces where poetry grows. Here, too, is where I’ve found meaning out of injustice, celebrated undefinability. But I can also identify that I am a type of person for which this ambiguity – where fault is shared, where forgiveness is granted with two hands – has made a faint sense of cloying guilt that I’ve received much more than I deserve, have been forgiven many more times that I should have, and have escaped the consequences of my failures in a way that has made me fat and happy, complicit in my own excuses as to why I live the way that I do.

This, of course, isn’t to say that I don’t want an environment where I feel as if I will be supported if I fail or allowed to make mistakes. It is, however, an inquiry into the perhaps more damning notion that I haven’t really ever truly deserved anything, whether ecstasy of the everyday, the opportunities I’ve had, the people that I can call my friends and family, the way I’ve been able to move through the world. Why do I have these things? Is it even possible to imagine a ‘cause’ large enough, pious enough, unquestionably virtuous enough that could result in this elation of my delight for my everyday life? I have received so, so much. My gratitude overwhelms me constantly, I feel like I am always failing to say thank you.

In this logical version of the world, my sense of thankfulness is nourished by work in all senses. My attunement to the karmic flow of the world manifests in my personal life, and I am able to reciprocate my joy by an inner sense of extended satisfaction and openness to work, effort, commitment. Work comes easily and naturally, and feels like an equivalent reciprocation to the universe for its gifts. Instead, I don’t feel satisfied by work at all. I think that fulfillment in life isn’t constructed off of work is true for most people. But again, perhaps more insidiously, I don’t find myself satisfied by hardly any work at all – in the capitalist definition, but also in the personal and descriptive. Even the things that are supposed to feel the most actionable, personal, self-serving – working out, taking care of my home, reading, writing – feel like work. How can I even begin to think about a real, genuine gratitude for the life I’ve been allowed to live when living well, even for just my own sake, feels like work? Is it possible to feel satisfied with anything I accomplish when that accomplishment feels unnatural and uncharacteristic? Is there such a thing as the feeling that I believe that I deserve a result that I actually get? Is it vanity to think that my joy is something I could have possibly endeavored to deserve?

As I, like many young adults, slowly realize that my work will never be a true reflection of what I am passionate about or interested in, I’ve struggled to look towards new hobbies to fill up my time. It’s not often that I understand the satisfaction of something well done, but when I do, it’s like the machinations of a world that I’ve felt like I was wired wrong for are suddenly, overwhelmingly obvious. The times I catch glimpses of that satisfaction are magical, like taking the first bite of a really good meal that I perfected, the view from the top of a difficult hike. I learned that the term for this is called complex leisure, and it’s defined by its scalable nature. Complex leisure differs from passive leisure by way of being something that one can improve at, participate in in different measures, and invest variable amounts of money in. Most adult hobbies are complex leisure, like climbing, recreational sports, cooking. The idea that sustains this type of leisure is that continual and self-implemented challenges lead to the same type of effort-result gratification relationship that is usually structured by school, traditional jobs, and capitalist institutions. This type of satisfaction is deeper, more meaningful, and leads to tangible outcomes for the practitioner.

I’ve always considered myself someone with a rich inner life. I’m grateful for it – I can spend time by myself well, entertain myself, make myself laugh. And yet, I don’t know why complex leisure evades me. I can’t quite bring myself to understand the type of sustained pleasure that complex leisure over a long period is supposed to bring. I’m afraid that deep down, I’ve never really worked towards anything in my life, and the ends of my pleasure receptors have been fried off permanently, not even from short-form content or the Internet which both definitely play a part, but from years of instant gratification, overlove, and community. I have been given so much and have done shockingly little to deserve it. I take, and take.

I think my indulgence in quick-fix dopamine – friends, the Internet, music – is actively preventing me from the revelation of gratitude, actual embodied gratitude that shines out from my chest without trying. Is it really possible to develop a dopamine response to real life, complex leisure, and work that can match the ecstasies of sugar, the Internet, sex? Even beyond that, what about my friends, nature, or music, my appreciation for which I have done absolutely nothing to cultivate? These things may not be given, per say, but my enjoyment derived from them is something I again have done nothing to deserve. I think there do exist people who have gotten close to perfect on their regulation of joy milieu, but I also think there are people who cosplay complex leisure in order to mine satisfaction from the Internet and sex, which brings me to my next thought, which is just how superficial attempting to understand all of this is. Trying to draw circles around things like satisfaction, joy, rhythms, feels like implementing a slow feeding schedule for an overenthusiastic dog, who will eat and eat until they throw up. I am both owner and dog, and when the hand and the mouth belong to the same beast it is quite, quite easy to fall into patterns of excessive stimulation. Perhaps the answer, just as it is to the dog, is a Kong filled with peanut butter¹, a slow drip of emotion controlled just enough to tame envy and ugly, jealous thoughts.

Some on the Internet call one such response to an overloaded brain a dopamine fast, where a break from social media and interactive technology is taken to reset the receptors of dopamine from instant gratification and addictive behaviors. This approach imagines the experience of instant feedback dopamine addiction to stem from the cyclical algorithms of the internet as much as the content itself. However, I was surprised to learn that the original concept of a ‘dopamine fast’ included fasting from things beyond the digital age: social interaction was one of them, another was eating for purposes other than basic sustenance². The aim of this practice was to abstain from not just quick dopamine fixes, but any at all. After a period of dormancy, brain receptors are supposed to recalibrate to the joys of daily life. Beyond dopamine, I think the necessary fast extends to other people. The cause and effect logic that I want to attempt should belong to my own body, start and end with me, remain something close. Maybe quick-release dopamine is avoidable, as are imaginary audiences with enough time and distance. But is it possible to abstain from place, even just for a little while? Can I extract these things – the city, the car, East Asia, beyond – from under my skin? I’m not sure it’s possible.

In a way, I’d like to do a system reset of sorts, one that brings the solution to this ennui down to eye level, like inputting ‘hello, world’ into a supercomputer. I’m trying to rediscover the clean boundaries of an effort and an outcome, like maybe the sharp edges will shoulder some logic back into me. In the face of absurdities in droves and joy so easily reveled in, there’s something sacred about an action and a consequence, praxis and its outcomes, a push and a fall. In short, I am determined to deserve something, to create the perfectly weighted outcome from the ultimate infallible action. Perhaps this an effort to assuage the guilt of my joy, as if by demonstrating that I am capable of working without immediate gratification, or that if I am able to say with my whole chest that I deserve an outcome, just one, that all the other ecstasies of my life are things that I can have also deserved, even if by less direct measures. I’m looking for proof of concept.

As I reflect on place, the practico-inert, and what no longer serves me, I think this guilt of incessant ungratefulness may one day take its place in these ranks. Guilt, too, is a node on my milieu, and I fear it will spread to eat at more of my being. I’m infinitely thankful for what the places I’ve explored in this project have given me, and it has taken a great deal of guilt to say that they no longer provide the joy, solace, and comfort they once did. As much as I would like to be the sole progenitor of my logical reset, these places will push their way into my blindspots, both material and emotional. They are a part of me.

As I challenge my place(s) to be more attentive to my needs, I, too, must think about how I curate it. I soak up the rays of my desk neighbor, my brother on Facetime, the blue of my water bottle. I am relentlessly tiraded upon by the fat clouds that hang over the parking lot of my school, the yellow flowers that bloom in the sidewalk cracks. They take their places in my soft body, and I carry the tastiest ones like a secret stash of snacks. I’ll break one in half. Perhaps this, too, can be gratitude. I hope you’d like to share.

See also: frozen grapes, the last few pearls at the bottom of a cup of boba, anything describable as a ‘team-building exercise’, trying to book-club something with friends online

Lol this is just called going to work

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Aside from your urbanism book in your blog description, what are some of your favorite authors?

I'm currently reading through murray bookchin's bibliography so recommend him. As well, Jane Jacob's The Life and Death of Great American cities is a classic, though I probably wouldn't consider her a favourite cause I have some beef with The Economy of Cities.

As well, I enjoy Petr Kropotkin's writings as they're the basis of modern anarchism. I'll also recommend Engin Isin's cities without citizens as an excellent look at Canadian cities, though I've not read his other works. Another author who I can only speak to a singular book of is Andy Merrifield and his work Metromarxism.

Outside urbanism and political theory though, I love Ray Bradbury. I have a complete collection of his short stories which I think are criminally underappreciated compared to Fahrenheit 451.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. Giovanni La Varra. “Post-it City: Los otros espacios públicos de la ciudad europea”. AAVV. Mutaciones. Actar/ ac en rêve centre d’architecture. Barcelona,2001. pp 426- 431. 2.Para reconstruir la perspectiva con la que hemos interpretado el concepto pueden consultarse los textos introductorios de www.ciutatsocasionals.net ; así como los artículos: M.Peran. “Ciutats Ocasionals”.Butlletí n.12. CASM. Barcelona, 2005 (también en SPAM_arq 4. Santiago de Chile,2006 .pp.61-62) y M.Peran.”Divergencias Latinoamericanas” summa+93. Buenos Aires, 2008.p128. 3.Kevin Lynch. La buena forma de la ciudad. Gustavo Gili. Barcelona, 1980. 4.M.Davis. City of Quartz. Vintage Books. New York, 1992. 5.Véase al respecto de este proceso histórico Hannah Arendt. La condición humana. Paidós. Barcelona,1983. especialmente pp-50-52. 6. Richard Sennett. La conciencia del ojo. Versal. Barcelona,1991. 7.Richard Sennett. Vida urbana e identidad personal. Peninsula. Barcelona,2001. especialmente pp 67-ss. 8.Richard Sennett. Idem. p.162. 9.Véase Arqueología Post-it City en http://www.ciutatsocasionals.net/archivocastellano/arqueopostit/arch_postit.htm 10.El mismo año de la publicación de La Sociedad del espectáculo (1967)de G.Debord, Rauol Vaneigem editaba su Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations. 11. Richard Sennett. Idem. p.241 y p.269. 12.Félix Guattari/ Suely Rolnik. Micropolítica. Cartografias del deseo. Tinta Limón/Traficantes de sueños. Buenos Aires,2005. p.189 13Paolo Cottino. La ciudad imprevista. Ed.Bellaterra.Barcelona,2005; Andy Merrifield. Dialectical Urbanism. Monthly Review Press.New York, 2002; Jean Paul Dollé. Fureurs de ville. Ed Bernard Grasset.Pris,1991; Manuel Delgado. El animal público. Anagrama.Barcelona,1999. 14. La naviere, c’est l’hetérotopie par excellence. Dans les civilisations sans bateaux les rêves se tarissent, l’espionage y remplace l’aventure, et la police, les corsaires. Michel Foucault. “Des espaces autres. Hétérotopies”. Dits et écrits.I.1954-1975. Gallimard.Paris,1984. 15. Henri Lefebvre. Espacio y política: El derecho a la ciudad. Peninsula. Barcelona,1976. 16. Para reconstruir este proceso, véanse los trabajos de David Harvey, en especial: La condición de la posmodernidad. Investigación sobre los orígenes del cambio cultural. Amorrortu ed. Buenos Aires,1998. 17.Manuel Delgado ha expuesto esta cuestión con especial clarividencia en el contexto de Barcelona (Elogi del vianant. Del “model Barcelona” a la Barcelona real. Edicions de 1984.Barcelona,2005; “Barcelona y la diversidad”,AAVV. Quórum. Institut de Cultura. Barcelona,2005.pp 253-257)

0 notes

Text

Andy Merrifield, Roses for Gramsci - Monthly Review Press, April 2025

Andy Merrifield, Roses for Gramsci – Monthly Review Press, April 2025 A remarkable personal journey through the life and writings of the great Sardinian Marxist, Antonio GramsciIn June 2023, author Andy Merrifield and his partner and their daughter moved from the UK to Rome, she to take a new job, he to get his creative juices flowing again, and both to begin a new life. A short time later, he…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Aprendizajes de la Revolución urbana y La Comuna de París de Henri Lefebvre

‘Lefebvre en la era del COVID’ por Andy Merrifield

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

Meğerse ne delilikmiş! Olmadığım bir şeyi olmak istemek, benim olmayan, başkasına ait bir oyunu oynamak ne delilikmiş.

Eşeklerin Bilgeliği - Andy Merrifield

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kimi zaman, güneş alan küçük bir alana girdiğinizde, bir anlığına da olsa, çarpılırsınız: özgür olduğunuzu, istediğinizi yapabileceğinizi, istediğiniz yere gidebileceğinizi ve hiç kimseye hesap vermek zorunda olmadığınızı hissedersiniz.

Eşeklerin Bilgeliği, Andy Merrifield

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marx grasped the difficulty of struggling against an economic process of producing capital. Kafka, however, intuited that this process would one day necessitate vast administrative management, beyond the massively complex divisions of labour: it would also involve aven more massive bureaucratic organisations, ordained by unaccountable, anonymous technocrats and bureaucrats. Kafka imagined how modern conflict is an us-against-a-world transformed into an immense, and invariably abstract, total administration. Such a vast administration sucks everything into a singular and unified spiralling force, into a seamless organisational web that has effectively collapsed and amalgamated different layers and boundaries. Erstwhile distinctions between the political and the economic, between conflict and consent, between politics and technocracy, between administration and self-administration, have lost their specific gravity and their clarity of meaning; each realm now simply elides into the other, and it's up to ordinary people to find their way out.

andy merrifield

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Each of us is a traveler in the wilderness of the world." — Andy Merrifield, The Wisdom of Donkeys

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonfiction Book Review: The Amateur by Andy Merrifield

What is an “amateur,” and what distinguishes it from what we think of as an “expert,” a “professional,” a master of one’s craft; someone who deserves

View On WordPress

#book review#nonfiction#nonfiction book review#philosophy#philosophy book review#the amateur#the amateur by Andy Merrifield

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“A travers la rêverie, nous dit Bachelard, nous devenons tous poètes, nous connaissons tous des moments de lucidité poétique. Pour lui la rêverie “est bien plutôt le don d’une heure qui connaît la plénitude de l’âme”.

A Celles, j’ai eu mon heure...

#Lectures#Bachelard#Andy Merrifield#Photos personnelles#Rêveries#Jardins#Celles#Fêtes des plantes#La Belgique#Les saisons#Le printemps

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks to @persistent-wallflower for tagging me 💌

Last song:

Revisiting this whole album lately specifically bc this song came on shuffle and I was like “god this is the best soundtrack to my intrusive thoughts to burn my whole life down”

Last movie: a Finnish film called Dogs Don’t Wear Pants about a man who becomes completely detached from his real life after meeting a dominatrix that chokes tf out of him. It was actually a really good story ;-; (and the ending was NOT anti-kink which I was happy with)

Last show: Currently watching: current season of drag race and a playthrough of Wo Long: Fallen Dynasty on YouTube :)

Currently reading: a collection of short stories called Evil Roots: Killer Tales of the Botanical Gothic 🪴🖤 and another called The Amateur by Andy Merrifield that is pro doing things for the love of it and not to be good or marketable at it

Current obsession: idk I’m not really being gorilla gripped by anything rn…. I’m definitely in a constantly cleaning phase rn though so imma say that lol

Tagging: @kirbyandthenerveofthisbitch, @library-of-leaves, @represent-asian, and @ccrustacian (only if y’all want :3)

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

One could perhaps ask, then, as Berlinsky did in the 1870s: if Dostoevsky’s Christ should ever appear, would he join the socialist movement and become its head? Dostoevsky’s last novel, The Brothers Karamazov (1880), sheds some light on this question. There he suggests that atheist socialists are the most religious people of our time. And just prior to his own death in 1881, he spoke of the sequel to Karamazov. Now Alyosha, the young contemplative monk, is a mature man who has left the monastery to “search for truth”. “In his quest,” Dostoevsky admits, he “would have naturally become a revolutionary.”

Andy Merrifield, “Notes on Suffering and Freedom: A Marxian and Dostoevskian Encounter”, in “Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture, and Society”, Vol. 11, No. 1, Spring 1999, p. 84.

15 notes

·

View notes