#Bartolomé de las Casas

Text

«Pero este alarde de ortodoxia aristotélica es un recurso retórico y no una verdadera declaración de fidelidad. De hecho, Las Casas y Sepúlveda no hablan la misma lengua. Uno todavía vive en el cosmos, cuando para el otro en el universo ha dejado de haber elementos ontológicamente diferenciados. La naturaleza, según el apologista de la conquista, se fundamenta en el principio de desigualdad y reconoce rangos, grados, niveles jerárquicos y órdenes distintos. La misma ley, para el defensor de los indios, rige un espacio unificado y una realidad homogénea. En otras palabras, lo que parece inaceptable en la manera de ver y de pensar el mundo que es ya la de Las Casas es el concepto mismo de esclavo natural: la naturaleza es lo que une a los hombres, no lo que los separa. Shylock puede empezar a asomarse: en ningún lugar de la tierra existen seres humanos de los que se tenga derecho a afirmar que no son hombres o que requieren, por su misma naturaleza o en su propio interés, ser puestos bajo tutela.»

Alain Finkielkraut: La humanidad perdida. Editorial Anagrama, pág. 24. Barcelona, 1998

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

#alain finkielkraut#finkielkraut#la humanidad perdida#ensayo sobre el siglo xx#las casas#sepúlvedad#shylock#el mercader de venecia#shakespeare#juan ginés de sepúlveda#controversia#junta de valladoliz#bartolomé de las casas#las indias#esclavitud#esclavitud por naturaleza#esclavitud por convención#los indios#aristotelísmo#ortodoxia aristotélica#cosmos#jerarquía#jerarquización#naturaleza#esclavo natural#niveles jerárquicos#teo gómez otero

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

God is the one who always remembers those whom history has forgotten.

Bartolomé de las Casas

#Bartolomé de las Casas#quotelr#God# History#quotes#literature#life quotes#author quotes#prose#lit#spilled ink

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Depiction of Spanish atrocities committed in the conquest of Cuba in Las Casas's "Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias". The print was made by two Flemish artists who had fled the Southern Netherlands because of their Protestant faith: Joos van Winghe was the designer and Theodor de Bry the engraver.

The Natives of Cumaná attack the mission after Gonzalez de Ocampo's slaving raid. Colored copperplate by Theodor de Bry, published in the "Relación brevissima"

Massacre_of_Queen_Anacaona_and_her_subjects

Bartolomé de las Casas Fray_Bartolomé_de_las_Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas (📷listen); 11 November 1484[1] – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar and priest. He was appointed as the first resident Bishop of Chiapas, and the first officially appointed "Protector of the Indians". His extensive writings, the most famous being A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies and Historia de Las Indias, chronicle the first decades of colonization of the West Indies. He described the atrocities committed by the colonizers against the indigenous peoples.

Arriving as one of the first Spanish (and European) settlers in the Americas, Las Casas initially participated in, but eventually felt compelled to oppose, the abuses committed by colonists against the Native Americans. As a result, in 1515 he gave up his Indian slaves and encomienda, and advocated, before King Charles I of Spain, on behalf of rights for the natives. In his early writings, he advocated the use of African slaves instead of Natives in the West Indian colonies but did so without knowing that the Portuguese were carrying out "brutal and unjust wars in the name of spreading the faith".[4] Later in life, he retracted this position, as he regarded both forms of slavery as equally wrong. In 1522, he tried to launch a new kind of peaceful colonialism on the coast of Venezuela, but this venture failed. Las Casas entered the Dominican Order and became a friar, leaving public life for a decade. He traveled to Central America, acting as a missionary among the Maya of Guatemala and participating in debates among colonial churchmen about how best to bring the natives to the Christian faith.

Travelling back to Spain to recruit more missionaries, he continued lobbying for the abolition of the encomienda, gaining an important victory by the passage of the New Laws in 1542. He was appointed Bishop of Chiapas, but served only for a short time before he was forced to return to Spain because of resistance to the New Laws by the encomenderos, and conflicts with Spanish settlers because of his pro-Indian policies and activist religious stance. He served in the Spanish court for the remainder of his life; there he held great influence over Indies-related issues. In 1550, he participated in the Valladolid debate, in which Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda argued that the Indians were less than human, and required Spanish masters to become civilized. Las Casas maintained that they were fully human, and that forcefully subjugating them was unjustifiable.

Bartolomé de las Casas spent 50 years of his life actively fighting slavery and the colonial abuse of indigenous peoples, especially by trying to convince the Spanish court to adopt a more humane policy of colonization. Unlike some other priests who sought to destroy the indigenous peoples' native books and writings, he strictly opposed this action. Although he did not completely succeed in changing Spanish views on colonization, his efforts did result in improvement of the legal status of the natives, and in an increased colonial focus on the ethics of colonialism.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartolom%C3%A9_de_las_Casas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: Territories of History

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our July pick:

Sarah H. Beckjord’s Territories of History explores the vigorous but largely unacknowledged spirit of reflection, debate, and experimentation present in foundational Spanish American writing. In historical works by writers such as Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Bartolomé de Las Casas, and Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Beckjord argues, the authors were not only informed by the spirit of inquiry present in the humanist tradition but also drew heavily from their encounters with New World peoples. More specifically, their attempts to distinguish superstition and magic from science and religion in the New World significantly influenced the aforementioned chroniclers, who increasingly directed their insights away from the description of native peoples and toward a reflection on the nature of truth, rhetoric, and fiction in writing history.

Due to a convergence of often contradictory information from a variety of sources—eyewitness accounts, historiography, imaginative literature, as well as broader philosophical and theological influences—categorizing historical texts from this period poses no easy task, but Beckjord sifts through the information in an effective, logical manner. At the heart of Beckjord’s study, though, is a fundamental philosophical problem: the slippery nature of truth—especially when dictated by stories. Territories of History engages both a body of emerging scholarship on early modern epistemology and empiricism and recent developments in narrative theory to illuminate the importance of these colonial authors’ critical insights. In highlighting the parallels between the sixteenth-century debates and poststructuralist approaches to the study of history, Beckjord uncovers an important legacy of the Hispanic intellectual tradition and updates the study of colonial historiography in view of recent discussions of narrative theory.

Read more and access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-03278-8.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

#Spanish American#History#European History#Literary Studies#American Literature#Literature#Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo#Bartolomé de Las Casas#Bernal Díaz del Castillo#Humanism#New World#Magic#Science#Religion#Rhetoric#Fiction#Philosophy#Epistomology#Empiricism#16th Century#PSU Press Unlocked#PSU Press

0 notes

Text

Palacio de San Telmo (Sevilla): Fachada Norte (y 2)

Vamos a continuar con el examen de los sevillanos ilustres que podemos encontrar en esta fachada, examen que empezamos ayer, después de haber examinado anteriormente la puerta principal.

Continue reading Palacio de San Telmo (Sevilla): Fachada Norte (y 2)

View On WordPress

#Antonio Suzillo#Arquitectura#Bartolomé de las Casas#Bartolomé Esteban Murillo#Benito Arias Montano#Escultura#Fernando Afán de Riberta y Téllez-Girón#Fernando de Herrera#Guerra de la Independencia#Luis Daoíz#Palacio de San Telmo (Sevilla)#Renacimiento#Sevilla#Siglo XIX#Siglo XVI#Siglo XVII

0 notes

Text

Contemplation in Community

Timestamps:

00:00:15 Introductions 00:01:40 Opening Prayer 00:04:35 What is Contemplation in Community? 00:06:25 St John Henry Newman on Contemplation – in the Midst of Ordinary Things 00:07:35 the Samaritan Woman at the Well 00:10:30 Sts. Augustine & Monica – Joint Contemplation 00:20:00 Jane Austen & Contemplation – Fanny Price & Edmund Bertram at the Window 00:31:20 Contemplating the Order in…

View On WordPress

#18th century satire#Academic#Aesthetics#African literature#Bartolomé de las Casas#Beautiful#Catholic#Catholic Conscience#Catholicism#Christian#Christianity and Literature#Contemplation#Dr Natasha Duquette#English#English Studies in Canada#Faith#Feminine Genius#Femininity#Good#Indigenous#Indigenous writers of North America#Jane Austen#Literary studies#Literature#Masculine Genius#Masculinity#Newman Centre#Newman Centre Toronto#Our Lady Seat of Wisdom College#Philosophy

0 notes

Text

the funniest thing about sixteenth century men's writings (particularly pamphlets/accounts) is that they wrote with all the passion and conviction of some tumblr blogger defending their favourite character from a kids' cartoon. you would not believe the levels of hyperbole those men reached

#🗡️#oh bartolomé de las casas we're really in it now#and simon fish he was particularly egregious for that

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You wouldn’t think anyone on Earth would praise Alonso de Hojeda and Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar yet Hugh Thomas did (he somehow also made Juan de la Cosa History’s villain).

#I'm used to people throwing shade at Bartolomé de Las Casas but Juan de la Cosa ???#hugh thomas#rivers of gold#bookblr#16th century#Spanish History

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My undergrad modern history class introduced me to a lot of really fascinating primary sources, many of which individually changed my perspective on the world in big ways. I don't remember all the sources we read, but the three that I've thought about most often since then (and which I really recommend people read) are:

In Defense of the Indians by Bartolomé de las Casas

Galeote Pereira's report on Ming China

The diary of Antera Duke

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Campesinos de Sacsahuamán, 1940. Photo by Horacio Ochoa. Cortesía de la Fototeca Andina, Centro Bartolomé de las Casas. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ckyx2t9NIHj/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

[D]omesticated attack dogs [...] hunted those who defied the profitable Caribbean sugar regimes and North America’s later Cotton Kingdom, [...] enforced plantation regimens [...], and closed off fugitive landscapes with acute adaptability to the varied [...] terrains of sugar, cotton, coffee or tobacco plantations that they patrolled. [...] [I]n the Age of Revolutions the Cuban bloodhound spread across imperial boundaries to protect white power and suppress black ambitions in Haiti and Jamaica. [...] [Then] dog violence in the Caribbean spurred planters in the American South to import and breed slave dogs [...].

---

Spanish landowners often used dogs to execute indigenous labourers simply for disobedience. [...] Bartolomé de las Casas [...] documented attacks against Taino populations, telling of Spaniards who ‘hunted them with their hounds [...]. These dogs shed much human blood’. Many later abolitionists made comparisons with these brutal [Spanish] precedents to criticize canine violence against slaves on these same Caribbean islands. [...] Spanish officials in Santo Domingo were licensing packs of dogs to comb the forests for [...] fugitives [...]. Dogs in Panama, for instance, tracked, attacked, captured and publicly executed maroons. [...] In the 1650s [...] [o]ne [English] observer noted, ‘There is nothing in [Barbados] so useful as … Liam Hounds, to find out these Thieves’. The term ‘liam’ likely came from the French limier, meaning ‘bloodhound’. [...] In 1659 English planters in Jamaica ‘procured some blood-hounds, and hunted these blacks like wild-beasts’ [...]. By the mid eighteenth century, French planters in Martinique were also relying upon dogs to hunt fugitive slaves. [...] In French Saint-Domingue [Haiti] dogs were used against the maroon Macandal [...] and he was burned alive in 1758. [...]

Although slave hounds existed throughout the Caribbean, it was common knowledge that Cuba bred and trained the best attack dogs, and when insurrections began to challenge plantocratic interests across the Americas, two rival empires, Britain and France, begged Spain to sell these notorious Cuban bloodhounds to suppress black ambitions and protect shared white power. [...] [I]n the 1790s and early 1800s [...] [i]n the Age of Revolutions a new canine breed gained widespread popularity in suppressing black populations across the Caribbean and eventually North America. Slave hounds were usually descended from more typical mastiffs or bloodhounds [...].

---

Spanish and Cuban slave hunters not only bred the Cuban bloodhound, but were midwives to an era of international anti-black co-ordination as the breed’s reputation spread rapidly among enslavers during the seven decades between the beginning of the Haitian Revolution in 1791 and the conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865. [...]

Despite the legends of Spanish cruelty, British officials bought Cuban bloodhounds when unrest erupted in Jamaica in 1795 after learning that Spanish officials in Cuba had recently sent dogs to hunt runaways and the indigenous Miskitos in Central America. [...] The island’s governor, Balcarres, later wrote that ‘Soon after the maroon rebellion broke out’ he had sent representatives ‘to Cuba in order to procure a number of large dogs of the bloodhound breed which are used to hunt down runaway negroes’ [...]. In 1803, during the final independence struggle of the Haitian Revolution, Cuban breeders again sold hundreds of hounds to the French to aid their fight against the black revolutionaries. [...] In 1819 Henri Christophe, a later leader of Haiti, told Tsar Alexander that hounds were a hallmark of French cruelty. [...]

---

The most extensively documented deployment of slave hounds [...] occurred in the antebellum American South and built upon Caribbean foundations. [...] The use of dogs increased during that decade [1830s], especially with the Second Seminole War in Florida (1835–42). The first recorded sale of Cuban dogs into the United States came with this conflict, when the US military apparently purchased three such dogs for $151.72 each [...]. [F]ierce bloodhounds reputed to be from Cuba appeared in the Mississippi valley as early as 1841 [...].

The importation of these dogs changed the business of slave catching in the region, as their deployment and reputation grew rapidly throughout the 1840s and, as in Cuba, specialized dog handlers became professionalized. Newspapers advertised slave hunters who claimed to possess the ‘Finest dogs for catching negroes’ [...]. [S]lave hunting intensified [from the 1840s until the Civil War] [...]. Indeed, tactics in the American South closely mirrored those of their Cuban predecessors as local slave catchers became suppliers of biopower indispensable to slavery’s profitability. [...] [P]rice [...] was left largely to the discretion of slave hunters, who, ‘Charging by the day and mile [...] could earn what was for them a sizeable amount - ten to fifty dollars [...]'. William Craft added that the ‘business’ of slave catching was ‘openly carried on, assisted by advertisements’. [...] The Louisiana slave owner [B.B.] portrayed his own pursuits as if he were hunting wild game [...]. The relationship between trackers and slaves became intricately systematized [...]. The short-lived republic of Texas (1836–46) even enacted specific compensation and laws for slave trackers, provisions that persisted after annexation by the United States.

---

All text above by: Tyler D. Parry and Charlton W. Yingling. "Slave Hounds and Abolition in the Americas". Past & Present, Volume 246, Issue 1, February 2020, pages 69-108. Published February 2020. At: doi dot org/10.1093/pastj/gtz020. February 2020. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#abolition#its first of february#while already extensive doumentation of dogs in american south in 1840s to 60s#a nice aspect of this article is focuses on two things#one being significance of shared crossborder collaboartion cooperation of the major empires and states#as in imperial divisions set aside by spain britain france and us and extent to which they#collectively helped each other crush black resistance#and then two the authors also focus on agency and significance of black resistance#not really reflected in these excerpts but article goes in depth on black collaboration#in newspapers and fugitive assistance and public discourse in mexico haiti us canada#good references to transcripts and articles at the time where exslaves and abolitionists#used the brutality of dog attacks to turn public perception in their favor#another thing is article includes direct quotes from government and colonial officials casually ordering attacks#which emphasizes clearly that they knew exactly what they were doing#ecology#indigenous#multispecies#borders#imperial#colonial#tidalectics#caribbean#carceral geography#archipelagic thinking

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“[Bartolomé de] Las Casas, whose doctrine appears to have been profoundly influenced by the professors of Salamanca, shared Vitoria's position on the rationality of the natives: If a sizable portion of the human race were without reason, we should be forced to speak of a defect in the order of creation. If so considerable a portion of mankind lacked the very faculty that distinguished man from the brutes and by which he could call upon and love God, God's intention to call all men to Himself would have failed. For the Christian, such a conclusion was simply unthinkable. This was Las Casas's reply to those who would argue that the natives constituted an example of what Aristotle had described as "slaves by nature"-there were far too many of them, and in any case they did not exhibit the level of debasement that Aristotle's conception appeared to call for. Ultimately, though, Las Casas was prepared to reject Aristotle on this point. He suggested that the natives "be attracted gently, in accordance with Christ's doctrine," and proposed that Aristotle's views on natural slavery be abandoned, since "we have in our favor Christ's mandate: love your neighbor as yourself...although he [Aristotle] was a great philosopher, study alone did not make him worthy of reaching God.”1”

- Thomas E. Woods Jr., Ph.D., “The Origins of International Law” How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization

—

1. Eduardo Andújar, "Bartolomé de Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda: Moral Theology versus Political Philosophy," in White, ed., Hispanic Philosophy, 76-78.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

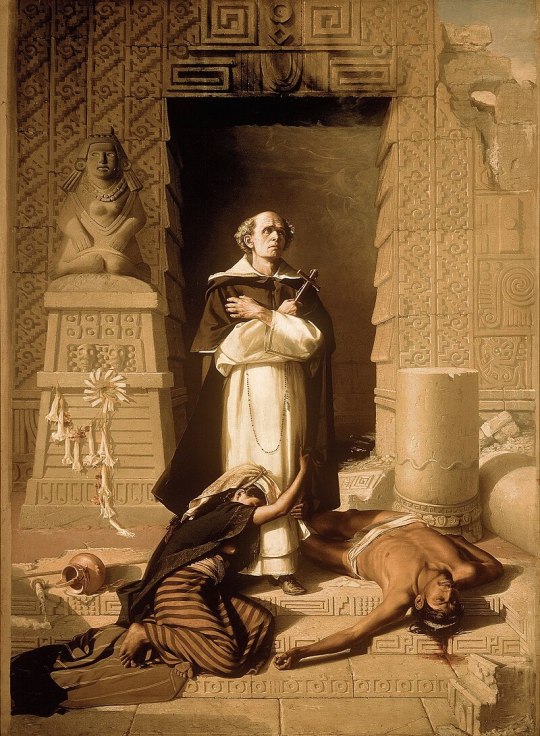

Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, by Felix Parra, 1875.

The saints are the true interpreters of Holy Scripture. The meaning of a given passage of the Bible becomes most intelligible in those human beings who have been totally transfixed by it and have lived it out. Interpretation of Scripture can never be a purely academic affair, and it cannot be relegated to the purely historical. Scripture is full of potential for the future, a potential that can only be opened up when someone "lives through" and "suffers through" the sacred text.

Pope Benedict XVI (Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, page 78). Bolded emphases added.

Bartolomé de las Casas was born in Seville, Spain, in 1484. At age eighteen, he came to the newly "discovered" lands, and five years later he was ordained as a priest in Rome. As an encomendero, he owned indigenous people who worked for him in the gold mines. Although he claims he treated them kindly and fed them, he acknowledged that he neglected teaching them the Christian faith. He was also a horrified eyewitness to a massacre of Cuban natives by invading Spaniards. [… But t]he text that was at the center of Bartolomé de las Casas' "conversion" is Sirach 34. In April 1514 he read this text in preparation to preach to the Spaniards who came to the new world to establish new villages. The passage immediately challenged his current privileges as an encomendero.

By his own admission, he read these verses in light of the situation of the indigenous people working for him in the Indies and realized that he was living in darkness; he was blind to the fact that he had become a tyrant who treated people unfairly. Thus, Bartolomé de las Casas embraced the mission of "preaching against injustice in order to bring light to those dominated by the darkness of ignorance" [History of the Indies]. His audience comprised people unable to realize the injustice behind their actions against the indigenous people, "such was and still is their blindness." He then proceeded to preach sermons against the oppression of indigenous people and to highlight their deplorable condition. His words were later followed by his decision to give up his "right" to possess slaves. His fellow Spaniards were in shock: "Everyone was surprised, even astonished, to hear this, and some walked away remorseful while others thought they had been dreaming — the idea of sinning because one used Indians was as incredible as saying man could not use domestic animals."

[… In 1543] he was named bishop of Chiapas. The authority attached to this position allowed him to engage in official debates with those defending the use of violence in the evangelization of indigenous people, such as Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda (1551). After a fruitful life defending indigenous people in Spain and in the new world with his pen and his preaching, de las Casas died in Madrid at age eighty-two.

Carlos Raúl Sosa Siliezar ("Scripture's Impact on Bartolomé de las Casas' Theology: Lessons for the Interpretation of Key Johannine Themes"). Bolded emphases added.

Ill-gotten goods offered in sacrifice are tainted.

Presents from the lawless do not win God's favor.

The Most High is not pleased with the gifts of the godless,

nor for their many sacrifices does He forgive their sins.

[As] One who slays a son in his father's presence —

[so is] whoever offers sacrifice from the holdings of the poor.

The bread of charity is life itself to the needy;

whoever withholds it is a murderer.

To take away a neighbor's living is to commit murder;

to deny a laborer wages is to shed blood.

the Book of Sirach (34:21-27)

#Christianity#Catholicism#Dominican#saints#Bartolome de las Casas#Scripture#Pope Benedict#Ben Sirach#slavery#abolition#colonization#imperialism

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Actually enslaving people is wrong because it’s a fucked up thing to do, and for centuries Christian’s didn’t get the memo on that one so realizing it’s a fucked up and horrible thing to do doesn’t come from ‘Christian ethics’

Also your blog is a complete eyesore

Slavery is f*cked up? That would have been news to the Greco-Roman world, many African societies throughout history, the Chinese well into the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire and most other Muslim societies, India in many periods of its history, the Norse, many Native American peoples and quite a few people today.

Slavery is so abhorrent to us that we don't realise that the correct question isn't "why does a given society have slavery"? Having slavery is the default for societies. Rather, we should ask why we don't have it.

Christianity, in large part.

Gregory of Nyssa, 4th century bishop and theologian, was the first known person to propose the abolition of slavery. While the other Church Fathers saw that as a pipe dream due to how pervasive it was, they almost all thought that slavery was a symptom of a fallen world and would disappear in the New Creation (and it largely did in the Byzantine Empire, the heartland of eastern Christianity). Whereas to the Greeks and Romans it was just an inherent and indisputable fact of life.

Over in the West, the Norse slave trade was primarily opposed by Christian clergy, and mainly on the religious grounds that it was immoral to treat fellow Christians like this (keep in mind that in their ideal world, everyone would be Christian). When slavery was revived by the Spanish, it was consistently opposed by a Dominican friar, Bartolomé de las Casas, using arguments based on the image of God and the works of Thomas Aquinas. When the Spanish crown agreed to a debate on slavery between him and fellow clergyman Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, Casas stuck to his arguments from the Christian tradition and Sepúlveda primarily argued from Aristotle.

With the transatlantic slave trade most people are familiar with, the opposition primarily came from Quakers and Evangelicals using arguments based on the image of God in all people. And they eventually succeeded, and Britain hence used its naval muscle to suppress slavery in the colonies and coerce the Ottomans into abolishing it; the sense this created of an Islamic institution being uprooted by foreign infidels led to the rise of Islamic fundamentalism (as such, it's hardly surprising that Islamic State have reinstituted it).

Whenever I have not provided a link, it came from one of the following three books, chiefly the first of them - Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind by Tom Holland (the classicist, not the actor), A Brief History of Life in the Middle Ages by Martyn Whittock and The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele.

I agree my blog could probably do with more of a visual component. If anyone has any suggestions please let me know.

#answered asks#history#christianity#seriously#every adult should read “dominion”#regardless of what you believe#this book will make you think

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"No podemos hacer como si la violencia no existiera" - El texto se extrae de la bandera que pintamos para la marcha del "orgullo" de Buenos Aires 2021 y del fanzine "Capítulo XXX: Una serpiente que devora a otra"// SECUELAS.

La frase remite a la normalización de un estado de violencia, a la internalización y naturalización que hacemos de las opresiones que históricamente aceptamos haciendo que forme parte de nuestra propia cultura, y a una re-apropiación de la misma.

----

Van a poder adquirir el bucito en la tienda virtual https://areyouacoporwhat.empretienda.com.ar/

Los detalles del bucito los van a encontrar en la tienda, se piden hasta el 6/julio y se empiezan a enviar el 10/julio :)

----

Las fotos fueron sacadas en el Monumento a España, de la Costanera Sur, diferentes esculturas que fueron empalmadas para rendir homenaje a España. El monumento es tan siniestro y en su momento gozó de tal impunidad que en una de sus partes se puede ver a Sebastián Gaboto, Bartolomé de Las Casas junto a una aborigen desnuda de arrodilla a sus pies, Juan de Garay y Pedro de Mendoza: el arte como legitimador de estructuras de poder, de normalizar la invasión, conquista y la colonización, la doctrina institucional naturaliza la llegada de España a estos territorios haciéndonos creer que antes de eso no existía comunidad, comunidades y cultura anterior. Y siguen haciéndonos creer que es así anulando las voces y luchas de los pueblos originarios y de las disidencias.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reimu Fumo also meets Bartolomé de las Casas!

12 notes

·

View notes