#Big Sid Catlett

Text

youtube

#chu berry#roy eldridge#sittin in#chu berry & his little jazz ensemble#music#clyde hart#danny barker#artie shapiro#big sid catlett#jazz#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earl Bostic: The Jazz Virtuoso Who Redefined Music

Introduction:

Earl Bostic, born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, one hundred and eleven years ago today on April 25, 1913, was a musical prodigy who left an indelible mark on jazz. His innovative approach to music and electrifying performances continue to inspire musicians and listeners worldwide.

Early Life and Musical Beginnings:

In his youth, Earl Bostic honed his musical talents, playing the clarinet…

View On WordPress

#Arnett Cobb#Big Sid Catlett#Cab Calloway#Charlie Christian#Charlie Parker#Clyde Hart#Don Byas#Earl Bostic#Edgar Hayes#Fate Marable#Hot Lips Page#Jazz History#Jazz Saxophonists#Lionel Hampton#Lou Donaldson#Rex Stewart#Terence Holder#Thelonious Monk#Twelve Clouds of Joy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The only other musicians I know who have had the same kind of feel as Charlie does are the great jazz drummers like Dave Tough, Big Sid Catlett and Jo Jones," he said. "It’s all a matter of having a sense of time and Charlie Watts is one of the very, very few, if any, drummers in rock ‘n’ roll who really have that sense." Ahmet Ertegun.

I remember when the Stones were signing with Atlantic- the only label they should ever associate themselves with- and Charlie asked Ahmet about some rumored lost tapes of jazz and R&B artists from the label’s history. Ahmet enthusiastically confirmed the existence of the tapes and as Charlie smiled Mick waved a hand and said “we will need copies of all that” and smiled back at Charlie.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

ART BLAKEY, LE MESSAGER DU JAZZ

“Blakey proved to be the most important mentor in jazz, introducing one great jazz talent after another by way of his Jazz Messengers—players who would go on to enjoy giant careers themselves.’’

- Peter Erskine

Né le 11 octobre 1919 à Pittsburgh, en Pennsylvanie, Arthur William Blakey était probablement le fils d’une mère célibataire connue sous le nom de Marie Roddicker ou Roddericker qui est décédée environ six mois après sa naissance. Le père biologique de Blakey, Bertram Thomas Blakey, était un barbier originaire d’Ozark en Alabama, mais sa famille s’était installée à Pittsburgh entre 1900 et 1910. Le père de Blakey aurait abandonné sa mère et son fils peu après sa naissance.

L’oncle de Blakey, Rubi Blakey, était un populaire chanteur de Pittsburgh qui était également directeur de chorale et un professeur qui avait fréquenté l’Université de Fisk, à Nashville.

JEUNESSE ET ÉDUCATION

Après la mort de sa mère, Blakey avait été élevé avec ses frères et soeurs par des amis ou des parents de la famille qui avaient un peu servi de famille de substitution. C’est sa cousine Sarah Oliver Parran et sa famille élargie qui auraient élevé Blakey jusqu’à ce qu’il commence à travailler dans une des usines sidérurgiques de l’endroit. Les témoignages ne s’entendent pas sur la durée du séjour de Blakey chez les Parran, même s’il est clair qu’il y a passé une bonne partie de son enfance.

Même s’il était largement autodidacte, Blakey semble avoir reçu quelques leçons de piano à l’école. Selon certaines sources, Blakey aurait abandonné l’école après sa septième année pour travailler dans une usine sidérurgique et jouer de la musique le soir. C’est en jouant du piano que Blakey avait appris à diriger ses propres groupes. On raconte même qu’il dirigeait son propre groupe de danse à l’âge de quatorze ans.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

C’est un peu par accident que Blakey avait troqué le piano pour la batterie au début des années 1930. On raconte qu’un propriétaire de club avait obligé Blakey à passer à la batterie afin de permettre au pianiste Erroll Garner de prendre sa place au piano. Blakey expliquait: “So I just went up there and played the show [on drums],”How, I’ll never know, but I made it.”

C’est donc un peu ‘’sur le tas’’ que Blakey avait appris à jouer de la batterie. Il précisait:

“I used to play every night. It didn’t matter how much money I was making, I just had to play every night. When we’d get through playing at night, it was daybreak. Then we’d play the breakfast show. After that we’d have a jam session, which would go on until like 2:00 in the afternoon. So maybe by 3:00 I’d get to bed, and I’d be back in the club again at 8:30. So I never stopped. I was playing all the time, so I didn’t have to worry about practicing. But when I did, I’d usually just practice on a pillow. I’d never practice on a pad because a pillow would make me pick up my sticks instead of depending on the rebound of the pad.”

Blakey avait aussi reçu des conseils précieux d’autres batteurs de Pittsburgh. Il racontait: “There was Klook [Kenny Clarke], there was a drummer named Jimmy Peck, and then there was a guy named Sammy Carter. But the guy I learned the most from in Pittsburgh was a guy named Honeyboy. That’s the cat who taught me how to play shows.” Blakey avait aussi obtenu des conseils de Chick Webb.

À l’époque, Blakey avait adopté le style agressif de batteurs de swing comme Chick Webb, Big Sid Catlett, Kaiser Marshall et Ray Bauduc. Il avait aussi été influencé par Gene Krupa et Kenny Clarke. Le rythme endiablé de la musique africaine avait également influencé Blakey, plus particulièrement après son séjour en Afrique en 1947. Même s’il avait adopté certaines techniques de percussion africaines à la suite de son séjour, Blakey ne ressentait aucune filiation particulière avec l’Afrique, car il se considérait d’abord comme un citoyen du monde. Il expliquait: “Since so many of the great jazz musicians are black, they try to connect us to Africa. But I’m an American black man. We ain’t got no connection to Africa. I imagine some of my people come from Africa, but there are some Irish people in there, too. I’m a human being and it don’t make no difference where I come from.’’

Lorsqu’on reprochait à Blakey de jouer de façon un peu trop énergique, il répondait:

“I just wanted to hear something different—to experiment. I always liked to innovate with different sounds on the drums when I started to play, because I came out of that era when the drummer played for effects. I had to learn to play a show in almost a standing position. I had to keep the bass drum going, grab this and blow that, and do a roll. But that was fantastic because it helped me get where I wanted to go and helped me find out what it was I wanted to do.’’

De 1939 à 1944, Blakey avait accompagné sa compatriote de Pittsburgh, la pianiste Mary Lou Williams, dans un engagement au club Kelly’s Stables de New York. Il avait aussi fait une tournée avec l’orchestre de Fletcher Henderson. Même si la chronologie exacte des événements n’est pas toujours claire, la plupart des sources s’accordent pour affirmer que Blakey avait joué dans le big band de Williams en 1942 avant de se joindre à l’orchestre d’Henderson un an plus tard.

Pendant qu’il jouait avec l’orchestre d’Henderson, Blakey avait été attaqué sans la moindre provocation par un policier de Georgie. La violence de cette agression était telle que Blakey avait dû se faire installer une plaque d’acier sous le crâne. À la suite de cette intervention, Blakey avait été déclaré inapte à prendre part à la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Après cette altercation, Blakey avait dirigé son propre groupe au Tic Toc Club de Boston durant une courte période.

De 1944 à 1947, Blakey avait travaillé avec le big band de Billy Eckstine. C’est grâce à son association avec cette formation que Blakey avait commencé à s’associer au mouvement bebop et à ses principaux chefs de file: Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Fats Navarro, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, etc.

En 1947, Blakey avaiit participé à plusieurs enregistrements avec le pianiste Thelonious Monk. C’est lors de ces sessions qu’avaient été enregistrées les premières versions de certains classiques de Monk comme ‘’Round Midnight’’, ‘’Well, You Needn’t’’ et ‘’Ruby My Dear.’’ Il s’agissait des premières sessions d’enregistrement de Monk comme leader.

Monk avait pris Blakey sous son aile à son arrivée à New York et l’avait aidé à faire sa place dans le milieu tumultueux des clubs new-yorkais. Comme Blakey l’avait expliqué dans une entrevue accordée au magazine Down Beat, ‘’He was my best friend.... If it hadn't been for him, I'm not so sure I would have been me. I learned so much playing with him, being with him." Blakey avait également enregistré en 1971 deux albums en trio avec Monk intitulés ‘’Something in Blue’’ et ‘’The Man I Love.’’ Ces deux sessions d’enregistrement avaient d’ailleurs été les deux dernières de la carrière de Monk.

En 1947, après la dissolution du big band d’Eckstine, Blakey avait séjourné en Afrique de l’ouest durant un an afin d’explorer la culture et la religion de l’Islam. À l’époque, plusieurs Afro-Américains étaient influencés par le missionnaire musulman Kahili Ahmed Nasir. C’est à la suite de ce voyage que Blakey s’était converti à l’Islam et avait adopté le nom de Abdullag Ibu Buhaina. Il avait même dirigé un big band appelé les 17 Messengers dont tous les membres portaient le turban ! Plutôt précaire financièrement, le groupe avaient été démantelé quelque temps plus tard.

Blakey avait cependant cessé d’être un musulman pratiquant dans les années 1950. Il avait continué de jouer sous le nom d’Art Blakey durant le reste de sa carrière.

Comme Blakey le reconnaissait lui-même, "In 1947, after the Eckstine band broke up, we—took a trip to Africa. I was supposed to stay there three months and I stayed two years because I wanted to live among the people and find out just how they lived and—about the drums especially." Dans une entrevue accordée en 1979 au magazine Down Beat, Blakey avait tenu à préciser:

"I didn't go to Africa to study drums – somebody wrote that – I went to Africa because there wasn't anything else for me to do. I couldn't get any gigs, and I had to work my way over on a boat. I went over there to study religion and philosophy. I didn't bother with the drums, I wasn't after that. I went over there to see what I could do about religion. When I was growing up I had no choice, I was just thrown into a church and told this is what I was going to be. I didn't want to be their Christian. I didn't like it. You could study politics in this country, but I didn't have access to the religions of the world. That's why I went to Africa. When I got back people got the idea I went there to learn about music."

Au début des années 1950, Blakey avait accompagné des musiciens de jazz comme Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie et Thelonious Monk, dont il aurait été le batteur de prédilection. De 1951 à 1953, Blakey avait fait une tournée avec le clarinettiste Buddy DeFranco. Le groupe comprenait aussi le pianiste Kenny Drew.

LA FONDATION DES JAZZ MESSENGERS

Le 17 décembre 1947, Blakey avait dirigé sa première session pour Blue Note, dans le cadre d’un groupe connu sous l’appellation d’’’Art Blakey’s Messengers.’’ Publiés d’abord sous forme de 78 tours, les premiers enregistrements du groupe contenaient deux pièces qui avaient plus tard été rééditées sur une compilation intitulée ‘’New Sounds.’’ À l’époque, le groupe comprenait huit musiciens parmi lesquels on remarquait Kenny Dorham, Musa Shihab, Musa Kaleem et Walter Bishop Jr.

Le nom de ‘’Messengers’’ avait éventuellement fini par s’imposer dans le cadre d’un groupe co-dirigé par Blakey et le pianiste Horace Silver, même si le nom n’avait pas été utilisé dans les premiers albums de la formation.

Le nom de Jazz Messengers avait été utilisé pour la première fois sur une session d’enregistrement de 1954 officiellement dirigée par Silver et mettant en vedette Blakey, Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham et Doug Watkins. Le même quintet avait enregistré l’album ‘’The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia’’ l’année suivante. Après que Donald Byrd ait remplacé Dorham à la trompette, le groupe avait enregistré un album simplement intitulé ‘’The Jazz Messengers’’ pour les disques Columbia en 1956. Blakey avait repris le nom du groupe lorsque Silver avait quitté la formation après sa première année d’existence (Silver avait apporté Mobley et Watkins avec lui pour fonder son propre quintet). Éventuellement, le nom de Blakey avait été ajouté au nom du groupe, qui se fit désormais connaître sous le titre de ‘’Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers.’’ Blakey avait dirigé le groupe jusqu’à sa mort.

Avec le temps, les Jazz Messengers étaient devenus une sorte d’archétype des groupes de hard bop des années 1950. Le groupe jouait une version agressive de bop qui était profondément enracinée dans le blues. À la fin des années 1950, les saxophonistes Johnny Griffin et Benny Golson s’étaient brièvement joints au groupe. Golson, comme directeur musical de la formation, avait composé plusieurs classiques du jazz qui avaient été intégrés au répertoire du groupe, comme ‘’I Remember Clifford’’ (un hommage à Clifford Brown), ‘’Along Came Betty’’ et ‘’Blues March’’, et qui avaient souvent été réinterprétés par les éditions ultérieures des Jazz Messengers. Golson avait également composé les pièces ‘’Whisper Not’’ et ‘’Are You Real.’’

UNE PÉPINIÈRE DE NOUVEAUX TALENTS

De 1959 à 1961, les Jazz Messengers étaient composés de Wayne Shorter au saxophone ténor, de Lee Morgan à la trompette, de Bobby Timmons au piano et de Jymie Merritt à la contrebasse. Au cours de cette période, le groupe avait enregistré plusieurs albums pour Blue Note, dont ‘’The Big Beat’’ et ‘’A Night in Tunisia.’’ De 1961 à 1964, le groupe s’était transformé en sextet avec l’ajout du joueur de trombone Curtis Fuller. Quant à Morgan, Timmons et Merritt, ils avaient été remplacés par Freddie Hubbard, Cedar Walton et Reggie Workman.

Le groupe, qui était devenu une véritable pépinière pour les nouveaux talents, avait enregistré les albums ‘’Buhaina’s Delight’’, ‘’Caravan’’ et ‘’Free for All.’’ Même si des vétérans du jazz ressurgissaient périodiquement dans la formation, chaque nouvelle édition des Messengers comprenait un alignement de ‘’jeunes loups.’’ Un séjour chez les Messengers était souvent considéré comme un rite de passage obligé pour les jeunes recrues.

Dans les années 1960, les Jazz Messengers étaient devenus un incontournable du circuit des clubs de jazz. Le groupe avait aussi fait des tournées en Europe et dans le nord de l’Afrique. En 1960, le groupe était devenu la première formation de jazz américain à se produire au Japon. En tout et pour tout, le groupe s’était rendu au Japon à 47 reprises au cours de son histoire.

Plusieurs recrues des Messengers étaient devenus des vedettes du jazz après leur passage dans le groupe: Lee Morgan, Clifford Brown, Benny Golson, Wayne Shorter, Johnny Griffin, Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Timmons, Curtis Fuller, Hank Mobley, Ira Sullivan, Donald Byrd, Kenny Dorham, Wallace Roney, Robin Eubanks, Cedar Walton, Curtis Fuller, Slide Hampton, Jackie McLean, Chuck Mangione, Keith Jarrett, Joanne Brackeen, James Williams, Woody Shaw, Wynton Marsalis, Branford Marsalis, Gary Bartz, Jaki Byard, Lou Donaldson, Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, Bobby Watson, Mulgrew Miller et combien d’autres.

Blakey avait enregistré des dizaines d’albums avec les Messengers. Que le groupe ait survécu à autant de changements de personnel demeure tout un exploit. Quand on demandait à Blakey pourquoi il recourait à de jeunes pousses qui n’avaient pas encore fait leurs preuves plutôt que de miser sur la sécurité en faisant appel à des vedettes établies, il répondait simplement: "I'm gonna stay with the youngsters. When these get too old I'll get some younger ones. Keeps the mind active." Dans une entrevue accordée en 1984, Blakey avait donné une autre raison de sa persistance à engager de jeunes musiciens. Il expliquait:

‘’My current band is pretty good, but I’m going to switch up the guys pretty soon. There are so many young kids out there who need the opportunity. I don’t want nobody in my band too long, because when cats stay too long, they get complacent, get big heads, and then it’s time to get out, buddy, because there are no stars in this band: The band is the star. Besides, I like to hear different interpretations. About my favorite Jazz Messenger group was the one with Wayne [Shorter], Freddie [Hubbard], Curtis [Fuller], Jymie [Merritt], and Cedar [Walton]. Musicians like that don’t come along all the time, but if you keep combing the woods, one will turn up sooner or later. And when they get strong enough to be on their own, I let them know it—time to do your own thing. See, a lot of things that happen in my band I don’t agree with, but I want to give it a chance to develop because there are some heavy young people out there.’’

Même si la popularité des Messengers avait nettement décliné avec l’émergence du jazz-fusion dans les années 1970, Blakey avait continué de miser sur de jeunes recrues comme Terence Blanchard et Kenny Garrett. Partisan du jazz acoustique, Blakey avait toujours résisté avec tenacité à toute tentative visant à ‘’moderniser’’ le son du groupe. Il expliquait: ‘’Jazz is an art form, and you have to choose. The record company executives with an eye on trends said to me, ‘Well Blakey, if you update your music and change it, put a little rock in there, you’ll come along.’ I will not prostitute my art for that. It’s not worth it. Gain the world and lose your soul? It’s no good.”

En 1971-1972, Blakey avait quitté temporairement les Messengers pour partir en tournée avec les Giants of Jazz, un groupe tout-étoile composé de Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Sonny Stitt, Thelonious Monk et Al McKibbon. En 1974, il avait aussi participé à une légendaire bataille des batteurs avec Max Roach, Buddy Rich et Elvin Jones dans le cadre du Festival de jazz de Newport.

PROBLÈMES DE SANTÉ ET DÉCÈS

Blakey avait continué de jouer et de faire des tournées avec le groupe jusqu’à la fin des années 1980. Ralph Peterson Jr. s’était joint à la formation comme second batteur afin de suppléer à la santé défaillante de Blakey. Blakey avait joué avec tant de puissance et de furie au cours de sa carrière qu’il était pratiquement devenu sourd. Si Blakey avait pu poursuivre sa carrière, c’est qu’il jouait surtout par instinct en demeurant à l’écoute des vibrations qu’il ressentait autour de lui. Il précisait: “The only thing I can hear is music. I can hear vibrations. I take my hearing aid off when I’m on the bandstand, and I can hear better than the other musicians; I know when they’re out of tune.”

Blakey avait toujours refusé de porter des prothèses auditives sous prétexte que cela nuisait à son synchronisme.

Le saxophoniste ténor Javon Jackson, qui avait fait partie des dernières éditions des Messengers, avait prétendu que Blakey avait exagéré la diminution de ses facultés auditives. Il expliquait: "In my opinion, his deafness was a little exaggerated, and it was exaggerated by him. He didn't hear well out of one ear, but he could hear just fine out the other one. He could hear you just fine when you played something badly and he was quick to say 'Hey, you missed that there.' But anything like 'I don't think I'll be available for the next gig', he'd say 'Huh? I can't hear you.'" Un autre musicien de la dernière heure, le pianiste Geoffrey Keezer, avait affirmé que la surdité de Blakey était simulée. Il précisait: ‘'He was selectively deaf. He'd go deaf when you asked him about money, but if it was real quiet and you talked to him one-on-one, then he could hear you just fine.'"

Art Blakey a présenté son dernier concert en juillet 1990. Il est mort le 16 octobre au St. Vincent’s Hospital de Manhattan. Il était mort d’un cancer du poumon, cinq jours après son 71e anniversaire de naissance. Blakey était en tournée au Japon lorsqu’il avait dû revenir aux États-Unis précipitamment, car il croyait avoir contracté une pneumonie.

Blakey laissait dans le deuil six filles (Gwendolyn, Evelyn, Jackie, Sakeena, Kadijah et Akira) et trois garçons (Takashi, Gamal et Kenji).

Lors des funérailles de Blakey célébrées le 22 octobre 1990 à l’église Abyssinian Baptist, plusieurs anciens membres des Messengers s’étaient réunis afin d’interpréter quelques-uns des plus grands succès du groupe. Parmi ces musiciens, on remarquait Brian Lynch, Javon Jackson, Geoffrey Keezer, Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Valery Ponomarev, Benny Golson, Donald Harrison, Essiet Okon Essiet et Kenny Washington. Au nombre des pièces interprétées, mentionnons ‘’Along Came Betty’’ de Benny Golson, ‘’Moanin’’’ de Bobby Timmons et ‘’One by One’’ de Wayne Shorter. Jackson, un membre des dernières éditions des Messengers, avait souligné à quel point ses expériences avec Blakey avaient changé sa vie. Il expliquait: "He taught me how to be a man. How to stand up and be accounted for". Jackie McLean, Ray Bryant, Dizzy Gillespie et Max Roach avaient aussi rendu hommage à Blakey lors des funérailles.

Blakey est considéré comme un des inventeurs du bebop avec Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Thelonious Monk, Kenny Clarke et Max Roach. Rendant hommage à Blakey après sa mort, Roach avait déclaré:

‘’Art was an original… He's the only drummer whose time I recognize immediately. And his signature style was amazing; we used to call him 'Thunder.' When I first met him on 52d Street in 1944, he already had the polyrhythmic thing down. Art was perhaps the best at maintaining independence with all four limbs. He was doing it before anybody was."

Dans les notes accompagnant la série de Ken Burns sur le jazz, on pouvait lire: "Blakey is a major figure in modern jazz and an important stylist in drums. From his earliest recording sessions with Eckstine, and particularly in his historic sessions with Monk in 1947, he exudes power and originality, creating a dark cymbal sound punctuated by frequent loud snare and bass drum accents in triplets or cross-rhythms." Burns avait ajouté:

‘’Although Blakey discourages comparison of his own music with African drumming, he adopted several African devices after his visit in 1948–9, including rapping on the side of the drum and using his elbow on the tom-tom to alter the pitch. Later he organized recording sessions with multiple drummers, including some African musicians and pieces. His much-imitated trademark, the forceful closing of the hi-hat on every second and fourth beat, has been part of his style since 1950–51… A loud and domineering drummer, Blakey also listens and responds to his soloists.’’

En digne héritier des Jazz Messengers, Blakey avait toujours su garder la flamme du jazz allumée. La batteuse Cindy Blackman avait déclaré après la mort de Blakey: "When jazz was in danger of dying out [during the 1970s], there was still a scene. Art kept it going." Blakey avait participé à plus de 470 enregistrements au cours de sa carrière.

Blakey a également influencé plusieurs batteurs, dont le batteur du groupe Weather Report, Peter Erskine. Ce dernier racontait:

“Art Blakey was the first drummer my drum teacher had me listen to, way back in 1959. His drumming was swinging, hard-driving, raw, unabashed, and unapologetic. Visceral—but what five-year-old kid knows the word ‘visceral’? Five-year-old-kids recognize honesty, however, and Blakey was as honest a drummer as the day was long. Art just played. As high-fidelity recording techniques got better and better, drums seemed to become more and more popular on LP albums, and Blakey’s name and sound were part of many multiple-drummer recordings including Gretsch Night at Birdland, Drum Suite, and The African Beat, all listening staples in our home. There was so much power coming out of Blakey’s drums that I imagined him to be a giant of a man. When my father took me to see Blakey at the Show Boat jazz club in Philadelphia at a Sunday matinee, I was amazed to see Art Blakey in person, standing on the sidewalk outside of the club. He was not eight-feet tall, as I had imagined! He was, instead, a very kind man, small in physical stature but huge in heart and power.’’

Erskine avait ajouté:

“Blakey proved to be the most important mentor in jazz, introducing one great jazz talent after another by way of his Jazz Messengers—players who would go on to enjoy giant careers themselves. Perhaps the most telling aspect of Blakey’s power as a bandleader and mentor was reflected in the relationship I had with Jazz Messenger alum Wayne Shorter during our four-year collaboration in the group Weather Report. Hardly a day would go by without Wayne telling some story or recounting an anecdote or life-story lesson that was about Art Blakey. In contrast, Wayne almost never brought up the name of his other boss, Miles Davis. It was always ‘Art this’ and ‘Art that’ with Wayne.’’

La batteuse Cindy Blackman a également été énormément influencée par Blakey. Dans une entrevue accordée au New York Times, elle avait déclaré: "[H]e adopted me like his daughter. He taught me a lot of things about drummers and music. But as important, he helped me when I was just starting out and not working too often. He'd ask me to sit in when he was playing, he helped me if I needed money. His influence on all us young musicians is incalculable."

Quant au saxophoniste Jackie McClean, il avait affirmé que Blakey ne lui avait pas seulement montré comment devenir un bon musicien, mais aussi comment devenir un homme et à devenir un citoyen responsable.

VIE PERSONNELLE

Bon vivant, Blakey aimait bien raconter des histoires. En plus d’être passionné de musique, il adorait les femmes, la nourriture et la boxe.

Art Blakey s’est marié quatre fois (il a aussi eu plusieurs maîtresses). Blakey avait d’abord épousé Clarice Stewart (qui avait seulement quatorze ans au moment de son mariage), avant de se remarier en 1956 avec Diana Bates. Après avoir épousé Atsuko Nakamura en 1968, Blakey avait finalement convolé en 1983 avec Anne Arnold. Blakey avait eu dix enfants de ses quatre mariages: six filles (Gwendolyn, Evelyn, Jackie, Kadijah, Sakeena et Akira) et quatre fils (Art Jr., Takashi, Kenji et Gamal). Sandy Warren, qui avait été la maîtresse de Blakey, a publié un livre de souvenirs relatant sa vie avec le batteur. L’ouvrage couvre la période s’étendant de la fin des années 1970 jusqu’au début des années 1980, à l’époque où Blakey vivait à Northfield au New Jersey avec Sandy et leur fils Takashi.

Comme plusieurs musiciens de jazz de son époque, Blakey avait rapidement développé une dépendance envers les narcotiques. Plusieurs musiciens comme le trompettiste Lee Morgan ont d’ailleurs affirmé que Blakey les avaient souvent entraînés dans sa dépendance.

Blakey était également reconnu pour sa consommation excessive d’alcool, même si un batteur comme Sid Catlett l’avait souvent incité à plus de modération. Le trompettiste Wynton Marsalis semble également avoir eu une influence positive sur Blakey en limitant sa consommation de drogues durant les concerts.

Art Blakey avait toujours été un grand fumeur. On le voit d’ailleurs derrière un épais nuage de fumée sur la pochette de l’album ‘’Buhaina’s Delight.’’

Blakey a remporté de nombreux honneurs au cours de sa carrière. Intronisé au Newport Jazz Festival Hall of Fame en 1976, il avait remporté le Reader’s Choice Award du magazine Down Beat en 1981. Blakey a été admis au Jazz Hall of Fame l’année suivante. En 1984, il avait remporté le prix Grammy décerné à la meilleure performance de jazz instrumentale pour son album ‘’New York Scene.’’ L’album ‘’Moanin’’ a été intronisé au Grammy Hall of Fame en 2001. En 2005, la carrière de Blakey avait été couronnée par la remise d’un Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, décerné à titre posthume. Art Blakey est également récipiendiaire d’un doctorat honorifique du Berklee College of Music (1987).

C-2023-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast

#LISTEN TO THE AUDIO HERE: Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast

Jon's archive https://archive.org/details/louie-bellson-interview-with-jon-hammond-hammond-cast

Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast

by

Jon Hammond

Usage

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International

Topics

Louie Bellson, Jazz Drummer, Band Leader, Double Bass Drums, Johnny Hodges, Pearl Bailey, Educator, HammondCast, CBS Radio, KYOU, KYCY, Jon Hammond

Language

English

Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast on CBS KYOU / KYCY Radio - August 2003, he appeared at Jazz Club Nouveau in San Francisco with tenor saxophonist Don Menza -

Louie Bellson's Wiki:

Birth nameLuigi Paolino Alfredo Francesco Antonio BalassoniBornJuly 6, 1924Rock Falls, IllinoisDiedFebruary 14, 2009 (aged 84)Los Angeles, CaliforniaGenresJazz, big band, swingOccupation(s)Musician, composer, arranger, bandleaderInstrument(s)DrumsYears active1931–2009LabelsRoulette, Concord, Pablo, Musicmasters

Louie Bellson (born Luigi Paolino Alfredo Francesco Antonio Balassoni, July 6, 1924 – February 14, 2009), often seen in sources as Louis Bellson, although he himself preferred the spelling Louie, was an American jazz drummer. He was a composer, arranger, bandleader, and jazz educator, and is credited with pioneering the use of two bass drums.[1]

Bellson performed in most of the major capitals around the world. Bellson and his wife, actress and singer Pearl Bailey[2] (married from 1952 until Bailey's death in 1990), had the second highest number of appearances at the White House (only Bob Hope had more).

Bellson was a vice president at Remo, a drum company.[3] He was inducted into the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1985

Bellson was born in Rock Falls, Illinois, in 1924, where his father owned a music store. He started playing drums at three years of age. While still a young child, Bellson's father moved the family and music store to Moline, Illinois.[5] At 15, he pioneered using two bass drums at the same time, a technique he invented in his high school art class.[6] At age 17, he triumphed over 40,000 drummers to win the Slingerland National Gene Krupa contest.[7]

After graduating from Moline High School in 1942, he worked with big bands throughout the 1940s, with Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, and Duke Ellington. In 1952, he married jazz singer Pearl Bailey. During the 1950s, he played with the Dorsey Brothers, Jazz at the Philharmonic, acted as Bailey's music director, and recorded as a leader for Norgran Records and Verve Records.[8]

Over the years, his sidemen included Ray Brown, Pete and Conte Candoli, Chuck Findley, John Heard, Roger Ingram, Don Menza, Blue Mitchell, Larry Novak, Nat Pierce, Frank Rosolino, Bobby Shew, Clark Terry, and Snooky Young.

In an interview in 2005 with Jazz Connection magazine, he cited as influences Jo Jones, Sid Catlett, and Chick Webb. "I have to give just dues to two guys who really got me off on the drums – Big Sid Catlett and Jo Jones. They were my influences. All three of us realized what Jo Jones did and it influenced a lot of us. We all three looked to Jo as the 'Papa' who really did it. Gene helped bring the drums to the foreground as a solo instrument. Buddy was a great natural player. But we also have to look back at Chick Webb's contributions, too."[9]

During the 1960s, he returned to Ellington's orchestra for Emancipation Proclamation Centennial stage production, My People in and for A Concert of Sacred Music, which is sometimes called The First Sacred Concert. Ellington called these concerts "the most important thing I have ever done."[10]

Bellson's album The Sacred Music of Louie Bellson and the Jazz Ballet appeared in 2006. In May 2009, Francine Bellson told The Jazz Joy and Roy syndicated radio show, "I like to call (Sacred) 'how the Master used two maestros,'" adding, "When (Ellington) did his sacred concert back in 1965 with Louie on drums, he told Louie that the sacred concerts were based on 'in-the-beginning,' the first three words of the bible." She recalled how Ellington explained to Louie that "in the beginning there was lightning and thunder and that's you!" Ellington exclaimed, pointing out that Louie's drums were the thunder. Both Ellington and Louie, says Mrs. Bellson, were deeply religious. "Ellington told Louie, 'You ought to do a sacred concert of your own' and so it was," said Bellson, adding, "'The Sacred Music of Louie Bellson' combines symphony, big band and choir, while 'The Jazz Ballet' is based on the vows of Holy Matrimony..."

On December 5, 1971, he took part in a memorial concert at London's Queen Elizabeth Hall for drummer Frank King. This tribute show also featured Buddy Rich and British drummer Kenny Clare. The orchestra was led by Irish trombonist Bobby Lamb and American trombonist Raymond Premru. A few years later, Rich (often called the world's greatest drummer) paid Bellson a compliment by asking him to lead his band on tour while he (Rich) was temporarily disabled by a back injury. Bellson accepted.

As a prolific creator of music, both written and improvised, his compositions and arrangements (in the hundreds) embrace jazz, jazz/rock/fusion, romantic orchestral suites, symphonic works and a ballet. Bellson was also a poet and a lyricist. His only Broadway venture, Portofino (1958), was a resounding flop that closed after three performances.[13]

As an author, he published more than a dozen books on drums and percussion. He was at work with his biographer on a book chronicling his career and bearing the same name as one of his compositions, "Skin Deep". In addition, "The London Suite" (recorded on his album Louie in London) was performed at the Hollywood Pilgrimage Bowl before a record-breaking audience. The three-part work includes a choral section in which a 12-voice choir sings lyrics penned by Bellson. Part One is the band's rousing "Carnaby Street", a collaboration with Jack Hayes.[14]

In 1987, at the Percussive Arts Society convention in Washington, D.C., Bellson and Harold Farberman performed a major orchestral work titled "Concerto for Jazz Drummer and Full Orchestra", the first piece ever written specifically for jazz drummer and full symphony orchestra. This work was recorded by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in England, and was released by the Swedish label BIS.

Bellson was known throughout his career to conduct drum and band clinics at high schools, colleges and music stores.[16]

Bellson maintained a tight schedule of clinics and performances of both big bands and small bands in colleges, clubs and concert halls. In between, he continued to record and compose, resulting in more than 100 albums and more than 300 compositions. Bellson's Telarc debut recording, Louie Bellson And His Big Band: Live From New York, was released in June 1994. He also created new drum technology for Remo, of which he was vice-president.[17]

Bellson received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters in 1985 at Northern Illinois University. As of 2005, among other performing activities, Bellson had visited his home town of Rock Falls, Illinois, every July for Louie Bellson Heritage Days, a weekend in his honor close to his July 6 birthday, with receptions, music clinics and other performances by Bellson.[1] At the 2004 event celebrating his 80th birthday, Bellson said, "I'm not that old; I'm 40 in this leg, and 40 in the other leg."[18] He celebrated his birthday every year at the River Music Experience in Davenport, Iowa.

Bellson was voted into the Halls of Fame for Modern Drummer magazine, in 1985, and the Percussive Arts Society, in 1978. Yale University named him a Duke Ellington Fellow in 1977. He received an honorary Doctorate from Northern Illinois University in 1985. He performed his original concert – Tomus I, II, III – with the Washington Civic Symphony in historic Constitution Hall in 1993. A combination of full symphony orchestra, big-band ensemble and 80-voice choir, "Tomus" was a collaboration of music by Bellson and lyrics by his late wife, Pearl Bailey. Bellson was a nine-time Grammy Award nominee.[19]

In January 1994, Bellson received the NEA Jazz Masters Award from the National Endowment for the Arts.[20] As one of three recipients, he was lauded by NEA chair Jane Alexander, who said, "These colossal talents have helped write the history of jazz in America."

On November 19, 1952, Bellson married American actress and singer, Pearl Bailey, in London. Bellson and Bailey adopted a son, Tony, in the mid-1950s, and a daughter, Dee Dee (born April 20, 1960).[22] Tony Bellson died in 2004, and Dee Dee Bellson died on July 4, 2009, at age 49, within five months of her father. After Bailey's death in 1990, Bellson married Francine Wright in September 1992.[23]

Wright, who had trained as a physicist and engineer at MIT,[24] became his manager. The union lasted until his death in 2009.[25]

On February 14, 2009, Bellson died at age 84 from complications of a broken hip suffered in December 2008 and Parkinson's disease. He is buried next to his father in Riverside Cemetery, Moline, Illinois.

Discography[edit]

As leader[edit]

1952 Just Jazz All Stars (Capitol)

1954 Louis Bellson and His Drums (Norgran)

1955 Skin Deep (Norgran) compiles Belson's 10 inch LPs The Amazing Artistry of Louis Bellson and The Exciting Mr. Bellson

1954 The Exciting Mr. Bellson and His Big Band (Norgran)

1954 Louis Bellson with Wardell Gray (Norgran)

1954 Louis Bellson Quintet (Norgran) also released as Concerto for Drums by Louis Bellson

1954 Journey into Love (Norgan) also released as Two in Love

1955 The Driving Louis Bellson (Norgran)

1956 The Hawk Talks (Norgran)

1957 Drumorama! (Verve)

1959 Let's Call It Swing (Verve)

1959 Music, Romance and Especially Love (Verve)

1957 Louis Bellson at The Flamingo (Verve)

1959 Live in Stereo at the Flamingo Hotel, Vol. 1: June 28, 1959

1961 Drummer's Holiday (Verve)

1960 The Brilliant Bellson Sound (Verve)

1960 Louis Bellson Swings Jule Styne (Verve)

1961 Around the World in Percussion (Roulette)

1962 Big Band Jazz from the Summit (Roulette)

1962 Happy Sounds (Roulette) with Pearl Bailey

1962 The Mighty Two (Roulette) with Gene Krupa

1964 Explorations (Roulette) with Lalo Schifrin

1965 Are You Ready for This? (Roost) with Buddy Rich

1965 Thunderbird (Impulse!)

1967 Repercussion (Studio2Stereo)

1968 Breakthrough! (Project 3)

1970 Louie in London (DRG)

1972 Conversations (Vocalion)

1974 150 MPH (Concord)

1975 The Louis Bellson Explosion (Pablo)

1975 The Drum Session (Philips Records with Shelly Manne, Willie Bobo & Paul Humphrey)

1976 Louie Bellson's 7 (Concord Jazz)

1977 Ecue Ritmos Cubanos (Pablo) with Walfredo de los Reyes

1978 Raincheck (Concord)

1978 Note Smoking

1978 Louis Bellson Jam with Blue Mitchell (Pablo)

1978 Matterhorn: Louie Bellson Drum Explosion

1978 Sunshine Rock (Pablo)

1978 Prime Time (Concord Jazz)

1979 Dynamite (Concord Jazz)

1979 Side Track (Concord Jazz)

1979 Louis Bellson, With Bells On! (Vogue Jazz (UK))[27]

1980 London Scene (Concord Jazz)

1980 Live at Ronnie Scott's (DRG)

1982 Hi Percussion (Accord)

1982 Cool, Cool Blue (Pablo)

1982 The London Gig (Pablo)

1983 Loose Walk

1984 Don't Stop Now! (Capri)

1986 Farberman: Concerto for Jazz Drummer; Shchedrin: Carmen Suite(BIS)

1987 Intensive Care

1988 Hot (Nimbus)

1989 Jazz Giants (Musicmasters)

1989 East Side Suite (Musicmasters)

1990 Airmail Special: A Salute to the Big Band Masters (Musicmasters)

1992 Live at the Jazz Showcase (Concord Jazz)

1992 Peaceful Thunder (Musicmasters)

1994 Live from New York (Telarc)

1994 Black Brown & Beige (Musicmasters)

1994 Cool Cool Blue (Original Jazz Classics)

1994 Salute (Chiaroscuro)

1995 I'm Shooting High (Four Star)

1995 Explosion Band (Exhibit)

1995 Salute (Chiaroscuro)

1995 Live at Concord Summer Festival (Concord Jazz)

1996 Their Time Was the Greatest (Concord Jazz)

1997 Air Bellson (Concord Jazz)

1998 The Art of Chart (Concord Jazz)[28]

As sideman[edit]

With Count Basie

Back with Basie (Roulette, 1962)

Basie in Sweden (Roulette, 1962)

Pop Goes the Basie (Reprise, 1965)

Basie's in the Bag (Brunswick, 1967)

The Happiest Millionaire (Coliseum, 1967)

Count Basie Jam Session at the Montreux Jazz Festival 1975 (Pablo, 1975)

With Benny Carter

Benny Carter Plays Pretty (Norgran, 1954)

New Jazz Sounds (Norgran, 1954)

In the Mood for Swing (MusicMasters, 1988)

With Buddy Collette

Porgy & Bess (Interlude 1957 [1959])

With Duke Ellington

Ellington Uptown (Columbia, 1952)

My People (Contact, 1963)

A Concert of Sacred Music (RCA Victor, 1965)

Ella at Duke's Place (Verve, 1965)

With Dizzy Gillespie

Roy and Diz (Clef, 1954)

With Stephane Grappelli

Classic Sessions: Stephane Grappelli, with Phil Woods and Louie Bellson (1987)

With Johnny Hodges

The Blues (Norgran, 1952–54, [1955])

Used to Be Duke (Norgran, 1954)

Louie Bellson, Jazz Drummer, Band Leader, Double Bass Drums, Johnny Hodges, Pearl Bailey, Educator, HammondCast, CBS Radio, KYOU, KYCY, Jon Hammond

Louie Bellson, Jazz Drummer, Band Leader, Double Bass Drums, Johnny Hodges, Pearl Bailey, Educator, HammondCast, CBS Radio, KYOU, KYCY, Jon Hammond

#Louie Bellson#Jazz Drummer#Band Leader#Double Bass Drums#Johnny Hodges#Pearl Bailey#Educator#HammondCast#CBS Radio#kyouka izumi#KYCY#Jon Hammond

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Benny Goodman & Big Sid Catlett - Roll 'Em - Live 1941

0 notes

Photo

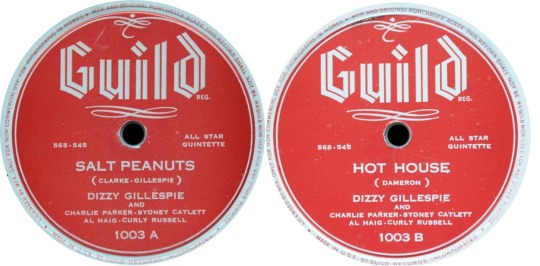

Dizzy Gillespie and His All Star Quintet

"Salt Peanuts" / "Hot House"

Be-Bop | Jazz

"Hot House became an anthem of the Be-Bop movement in American Jazz."

- Wikipedia

Dizzy Gillespie and His All Star Quintet - Salt Peanuts (1945)

Dizzy Gillespie / Kenny Clarke

from: "Salt Peanuts" / "Hot House"

JukehostUK

(left click = play)

(320kbps)

Personnel:

Dizzy Gillespie: Trumpet / Vocals

Charlie Parker: Alto Saxophone

Al Haig: Piano

Curley Russell: Bass

Sid Catlett: Drums

Recorded:

@ Unknown Recording Studio

on May 11, 1945

in New York City, New York USA

+++ +++ +++

Dizzy Gillespie and His All Star Quintet - Hot House (1945)

Tadd Dameron

from: "Salt Peanuts" / "Hot House"

JukehostUK

(left click = play)

(320kbps)

Personnel:

Dizzy Gillespie: Trumpet

Charlie Parker: Alto Saxophone

Al Haig: Piano

Curley Russell: Bass

"Big" Sid Catlett: Drums

Recorded:

@ Unknown Recording Studio

on May 11, 1945

in New York City, New York USA

#Jazz#Be-Bop#Hot House#Guild Records#Dizzy Gillespie#Post-War Jazz#Charlie Parker#Al Haig#Curley Russell#Sid Catlett#Big Sid Catlett#Salt Peanuts#1940's

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Big Sid Catlett: Five Clips

A couple of years ago at the Satchmo Summerfest, drummer Rich Noorigian, jazz historian and archivist Ricky Riccardi and I put together a tribute to unsung drummer Big Sid Catlett, who was comfortable in any setting from Armstrong to John Kirby to Charlie Parker. JazzWax sends a fine tribute our way with Big Sid as the headliner.

-Scott Wenzel

Watch and listen from JazzWax…

Follow: Mosaic Records Facebook Tumblr Twitter

#Big Sid Catlett#drummers#trad & big band#Louis Armstrong#Benny Goodman#Roy Eldridge#Duke Ellington#Dizzy Gillespie#Eddie Condon#Scott Wenzel

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musical Monday: Boy! What a Girl! (1947)

Musical Monday: Boy! What a Girl! (1947)

It’s no secret that the Hollywood Comet loves musicals.

In 2010, I revealed I had seen 400 movie musicals over the course of eight years. Now that number is over 600. To celebrate and share this musical love, here is my weekly feature about musicals.

This week’s musical:

Boy! What a Girl! (1947) – Musical #426

Studio:

Herald Pictures

Director:

Arthur H. Leonard

Starring:

Tim Moore, Elwood Smith,…

View On WordPress

#1940s musical#Ann Cornell#Big Sid Catlett#Deek Watson and the Brown Dots#Gene Krupa#Harlemaniacs#Jazz Music#Race films#Race musical#Sid Catlett Band#Slam Stewart Trio#Tim Moore

0 notes

Text

Art Blakey

Pittsburgh, PA ・October 11th, 1919

New York City, NY ・October 16, 1990

In the '60s, when John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman were defining the concept of a jazz avant-garde, few knowledgeable observers would have guessed that in another 30 years the music's mainstream would virtually bypass their innovations, in favor of the hard bop style that free jazz had apparently supplanted. As it turned out, many listeners who had come to love jazz as a sophisticated manifestation of popular music were unable to accept the extreme esotericism of the avant-garde; their tastes were rooted in the core elements of "swing" and "blues," characteristics found in abundance in the music of the Jazz Messengers, the quintessential hard bop ensemble led by drummer Art Blakey. In the '60s, '70s, and '80s, when artists on the cutting edge were attempting to transform the music, Blakey continued to play in more or less the same bag he had since the '40s, when his cohorts included the likes of Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Fats Navarro. By the '80s, the evolving mainstream consensus had reached a point of overwhelming approval in regard to hard bop: this is what jazz is, and Art Blakey -- as its longest-lived and most eloquent exponent -- was its master.

The Jazz Messengers had always been an incubator for young talent. A list of the band's alumni is a who's who of straight-ahead jazz from the '50s on -- Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Johnny Griffin, Jackie McLean, Donald Byrd, Bobby Timmons, Cedar Walton, Benny Golson, Joanne Brackeen, Billy Harper, Valery Ponomarev, Bill Pierce, Branford Marsalis, James Williams, Keith Jarrett, and Chuck Mangione, to name several of the most well-known. In the '80s, precocious graduates of Blakey's School for Swing would continue to number among jazz's movers and shakers, foremost among them being trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. Marsalis became the most visible symbol of the '80s jazz mainstream; through him, Blakey's conservative ideals came to dominate the public's perception of the music. At the time of his death in 1990, the Messenger aesthetic dominated jazz, and Blakey himself had arguably become the most influential jazz musician of the past 20 years.

Blakey's first musical education came in the form of piano lessons; he was playing professionally as a seventh grader, leading his own commercial band. He switched to drums shortly thereafter, learning to play in the hard-swinging style of Chick Webb and Sid Catlett. In 1942, he played with pianist Mary Lou Williams in New York. He toured the South with Fletcher Henderson's band in 1943-1944. From there, he briefly led a Boston-based big band before joining Billy Eckstine's new group, with which he would remain from 1944-1947. Eckstine's big band was the famous "cradle of modern jazz," and included (at different times) such major figures of the forthcoming bebop revolution as Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Charlie Parker. When Eckstine's group disbanded, Blakey started a rehearsal ensemble called the Seventeen Messengers. He also recorded with an octet, the first of his bands to be called the Jazz Messengers. In the early '50s, Blakey began an association with Horace Silver, a particularly likeminded pianist with whom he recorded several times. In 1955, they formed a group with Hank Mobley and Kenny Dorham, calling themselves "Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers." The Messengers typified the growing hard bop movement -- hard, funky, and bluesy, the band emphasized the music's primal rhythmic and harmonic essence. A year later, Silver left the band, and Blakey became its leader. From that point, the Messengers were Blakey's primary vehicle, though he would continue to freelance in various contexts. Notable was A Jazz Message, a 1963 Impulse record date with McCoy Tyner, Sonny Stitt, and Art Davis; a 1971-1972 world tour with "the Giants of Jazz," an all-star venture with Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt, and Al McKibbon; and an epochal drum battle with Max Roach, Elvin Jones, and Buddy Rich at the 1964 Newport Jazz Festival. Blakey also frequently recorded as a sideman under the leadership of ex-Messengers.

Blakey's influence as a bandleader could not have been nearly so great had he not been such a skilled instrumentalist. No drummer ever drove a band harder; none could generate more sheer momentum in the course of a tune; and probably no drummer had a lower boiling point -- Blakey started every performance full-bore and went from there. His accompaniment style was relentless, and woe to the young saxophonist who couldn't keep up, for Blakey would run him over like a fullback. Blakey differed from other bop drummers in that his style was almost wholly about the music's physical attributes. Where his contemporary Max Roach dealt extensively with the drummer's relationship to melody and timbre, for example, Blakey showed little interest in such matters. To him, jazz percussion wasn't about tone color; it was about rhythm -- first, last, and in between. Blakey's drum set was the engine that propelled the music. To the extent that he exhibited little conceptual development over the course of his long career, either as a player or as a bandleader, Blakey was limited. He was no visionary by any means. But Blakey did one thing exceedingly well, and he did it with genius, spirit, and generosity until the very end of his life.

— Chris Kelsey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

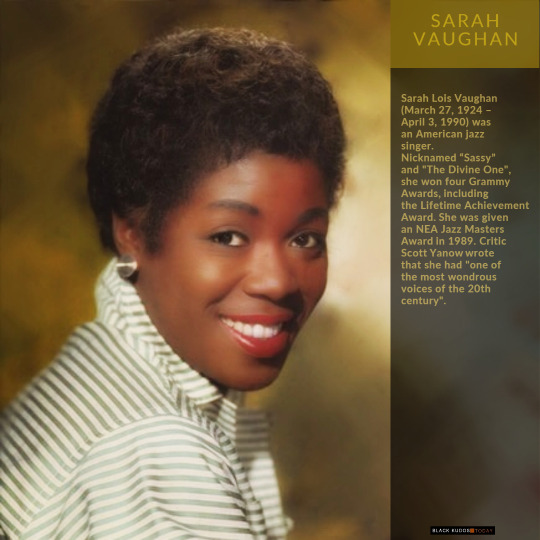

Sarah Vaughan

Sarah Lois Vaughan (March 27, 1924 – April 3, 1990) was an American jazz singer.

Nicknamed "Sassy" and "The Divine One", she won four Grammy Awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award. She was given an NEA Jazz Masters Award in 1989. Critic Scott Yanow wrote that she had "one of the most wondrous voices of the 20th century".

Early life

Vaughan's father, Asbury "Jake" Vaughan, was a carpenter by trade and played guitar and piano. Her mother, Ada Vaughan, was a laundress who sang in the church choir. The Vaughans lived in a house on Brunswick Street in Newark for Vaughan's entire childhood. Jake was deeply religious. The family was active in New Mount Zion Baptist Church at 186 Thomas Street. Vaughan began piano lessons at the age of seven, sang in the church choir, and played piano for rehearsals and services.

She developed an early love for popular music on records and the radio. In the 1930s, she frequently saw local and touring bands at the Montgomery Street Skating Rink. By her mid-teens, she began venturing illegally into Newark's night clubs and performing as a pianist and singer at the Piccadilly Club and the Newark Airport.

Vaughan attended East Side High School, then transferred to Newark Arts High School, which opened in 1931. As her nocturnal adventures as a performer overwhelmed her academic pursuits, she dropped out of high school during her junior year to concentrate on music.

Career

1942–43: Early career

Vaughan was frequently accompanied by a friend, Doris Robinson, on her trips into New York City. In the fall of 1942, by which time she was 18 years old, Vaughan suggested that Robinson enter the Apollo Theater Amateur Night contest. Vaughan played piano accompaniment for Robinson, who won second prize. Vaughan later decided to go back and compete as a singer herself. She sang "Body and Soul", and won—although the date of this victorious performance is uncertain. The prize, as Vaughan recalled to Marian McPartland, was $10 and the promise of a week's engagement at the Apollo. On November 20, 1942, she returned to the Apollo to open for Ella Fitzgerald.

During her week of performances at the Apollo, Vaughan was introduced to bandleader and pianist Earl Hines, although the details of that introduction are disputed. Billy Eckstine, Hines' singer at the time, has been credited by Vaughan and others with hearing her at the Apollo and recommending her to Hines. Hines claimed later to have discovered her himself and offered her a job on the spot. After a brief tryout at the Apollo, Hines replaced his female singer with Vaughan on April 4, 1943.

1943–44: Earl Hines and Billy Eckstine

Vaughan spent the remainder of 1943 and part of 1944 touring the country with the Earl Hines big band, which featured Billy Eckstine. She was hired as a pianist so Hines could hire her under the jurisdiction of the musicians' union (American Federation of Musicians) rather than the singers union (American Guild of Variety Artists). But after Cliff Smalls joined the band as a trombonist and pianist, her duties were limited to singing. The Earl Hines band in this period is remembered as an incubator of bebop, as it included trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, saxophonist Charlie Parker (playing tenor saxophone rather than alto), and trombonist Bennie Green. Gillespie arranged for the band, although the contemporary recording ban by the musicians' union meant that no commercial recordings exist.

Eckstine quit the Hines band in late 1943 and formed a big band with Gillespie, leaving Hines to become the band's musical director. Parker joined Eckstine, and over the next few years the band included Gene Ammons, Art Blakey, Miles Davis, Kenny Dorham, Dexter Gordon, and Lucky Thompson. Vaughan accepted Eckstine's invitation to join his band in 1944, giving her the opportunity to record for the first time on December 5, 1944, on the song. "I'll Wait and Pray" for De Luxe. Critic and producer Leonard Feather asked her to record later that month for Continental with a septet that included Dizzy Gillespie and Georgie Auld. She left the Eckstine band in late 1944 to pursue a solo career, although she remained close to Eckstine and recorded with him frequently.

Pianist John Malachi is credited with giving Vaughan the moniker "Sassy", a nickname that matched her personality. She liked it, and the name and its shortened variant "Sass" stuck with colleagues and the press. In written communications, Vaughan often spelled it "Sassie".

1945–48: Early solo career

Vaughan began her solo career in 1945 by freelancing on 52nd Street in New York City at the Three Deuces, the Famous Door, the Downbeat, and the Onyx Club. She spent time at Braddock Grill next to the Apollo Theater in Harlem. On May 11, 1945, she recorded "Lover Man" for Guild with a quintet featuring Gillespie and Parker with Al Haig on piano, Curly Russell on double bass, and Sid Catlett on drums. Later that month, she went into the studio with a slightly different and larger Gillespie/Parker aggregation and recorded three more sides.

After being invited by violinist Stuff Smith to record the song "Time and Again" in October 1945, Vaughan was offered a contract to record for Musicraft by owner Albert Marx, although she would not begin recording as a leader for Musicraft until May 7, 1946. In the intervening time, she recorded for Crown and Gotham and began performing regularly at Café Society Downtown, an integrated club in New York's Sheridan Square.

While at Café Society, Vaughan became friends with trumpeter George Treadwell, who became her manager. She delegated to him most of the musical director responsibilities for her recording sessions, allowing her to concentrate on singing. Over the next few years, Treadwell made changes in Vaughan's stage appearance. Aside from a new wardrobe and hair style, she had her teeth capped, eliminating a gap between her two front teeth.

Her recordings for Musicraft included "If You Could See Me Now" (written and arranged by Tadd Dameron), "Don't Blame Me", "I've Got a Crush on You", "Everything I Have Is Yours" and "Body and Soul". With Vaughan and Treadwell's professional relationship on solid footing, the couple married on September 16, 1946.

In 1947, Vaughan performed at the third Cavalcade of Jazz concert held at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles which was produced by Leon Hefflin, Sr. on September 7, 1947. The Valdez Orchestra, The Blenders, T-Bone Walker, Slim Gaillard, The Honeydrippers, Johnny Otis and his Orchestra, Woody Herman, and the Three Blazers also performed that same day.

Vaughan's recording success for Musicraft continued through 1947 and 1948. Her recording of "Tenderly"—she was proud to be the first to have recorded that jazz standard—became an unexpected pop hit in late 1947. Her December 27, 1947, recording of "It's Magic" (from the Doris Day film Romance on the High Seas) found chart success in early 1948. Her recording of "Nature Boy" from April 8, 1948, became a hit around the time the popular Nat King Cole version was released. Because of a second recording ban by the musicians' union, "Nature Boy" was recorded with an a cappella choir.

1948–53: Stardom and the Columbia years

The musicians' union ban pushed Musicraft to the brink of bankruptcy. Vaughan used the missed royalty payments as an opportunity to sign with the larger Columbia record label. After the settling of legal issues, her chart successes continued with "Black Coffee" in the summer of 1949. While at Columbia through 1953, she was steered almost exclusively to commercial pop ballads, several with success on the charts: "That Lucky Old Sun", "Make Believe (You Are Glad When You're Sorry)", "I'm Crazy to Love You", "Our Very Own", "I Love the Guy", "Thinking of You" (with pianist Bud Powell), "I Cried for You", "These Things I Offer You", "Vanity", "I Ran All the Way Home", "Saint or Sinner", "My Tormented Heart", and "Time".

She won Esquire magazine's New Star Award for 1947, awards from Down Beat magazine from 1947 to 1952, and from Metronome magazine from 1948 to 1953. Recording and critical success led to performing opportunities, with Vaughan singing to large crowds in clubs around the country during the late 1940s and early 1950s. In the summer of 1949, she made her first appearance with a symphony orchestra in a benefit for the Philadelphia Orchestra entitled "100 Men and a Girl." Around this time, Chicago disk jockey Dave Garroway coined a second nickname for her, "The Divine One", that would follow her throughout her career. One of her early television appearances was on DuMont's variety show Stars on Parade (1953–54) in which she sang "My Funny Valentine" and "Linger Awhile".

In 1949, with their finances improving, Vaughan and Treadwell bought a three-story house on 21 Avon Avenue in Newark, occupying the top floor during their increasingly rare off-hours at home and moving Vaughan's parents to the lower two floors. However, business pressures and personality conflicts led to a cooling in Treadwell and Vaughan's relationship. Treadwell hired a road manager to handle her touring needs and opened a management office in Manhattan so he could work with other clients.

Vaughan's relationship with Columbia soured as she became dissatisfied with the commercial material and its lackluster financial success. She made some small-group recordings in 1950 with Miles Davis and Bennie Green, but they were atypical of what she recorded for Columbia.

Radio

In 1949, Vaughan had a radio program, Songs by Sarah Vaughan, on WMGM in New York City. The 15-minute shows were broadcast in the evenings on Wednesday through Sunday from The Clique Club, described as "rendezvous of the bebop crowd." She was accompanied by George Shearing on piano, Oscar Pettiford on double bass, and Kenny Clarke on drums.

1954–59: Mercury years

In 1953, Treadwell negotiated a contract for Vaughan with Mercury in which she would record commercial material for Mercury and jazz-oriented material for its subsidiary, EmArcy. She was paired with producer Bob Shad, and their working relationship yielded commercial and artistic success. Her debut recording session at Mercury took place in February 1954. She remained with Mercury through 1959. After recording for Roulette from 1960 to 1963, she returned to Mercury from 1964 to 1967.

Her commercial success at Mercury began with the 1954 hit "Make Yourself Comfortable", recorded in the fall of 1954, and continued with "How Important Can It Be" (with Count Basie), "Whatever Lola Wants", "The Banana Boat Song", "You Ought to Have a Wife", and "Misty". Her commercial success peaked in 1959 with "Broken Hearted Melody", a song she considered "corny" which nevertheless became her first gold record, and a regular part of her concert repertoire for years to come. Vaughan was reunited with Billy Eckstine for a series of duet recordings in 1957 that yielded the hit "Passing Strangers". Her commercial recordings were handled by a number of arrangers and conductors, primarily Hugo Peretti and Hal Mooney.

The jazz "track" of her recording career proceeded apace, backed either by her working trio or combinations of jazz musicians. One of her favorite albums was a 1954 sextet date that included Clifford Brown.

In the latter half of the 1950s she followed a schedule of almost non-stop touring. She was featured at the first Newport Jazz Festival in the summer of 1954 and starred in subsequent editions of that festival at Newport and in New York City for the remainder of her life. In the fall of 1954, she performed at Carnegie Hall with the Count Basie Orchestra on a bill that also included Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Lester Young and the Modern Jazz Quartet. That fall, she again toured Europe before embarking on a "Big Show" U.S. tour, a succession of performances that included Count Basie, George Shearing, Erroll Garner and Jimmy Rushing. At the 1955 New York Jazz Festival on Randalls Island, Vaughan shared the bill with the Dave Brubeck quartet, Horace Silver, Jimmy Smith, and the Johnny Richards Orchestra.

Although the professional relationship between Vaughan and Treadwell was quite successful through the 1950s, their personal relationship finally reached a breaking point and she filed for a divorce in 1958. Vaughan had entirely delegated financial matters to Treadwell, and despite significant income figures reported through the 1950s, at the settlement Treadwell said that only $16,000 remained. The couple evenly divided the amount and their personal assets, terminating their business relationship.

1959–69: Atkins and Roulette

The exit of Treadwell from Vaughan's life was precipitated by the entry of Clyde "C.B." Atkins, a man of uncertain background whom she had met in Chicago and married on September 4, 1959. Although Atkins had no experience in artist management or music, Vaughan wished to have a mixed professional and personal relationship like the one she had with Treadwell. She made Atkins her manager, although she was still feeling the sting of the problems she had with Treadwell and initially kept a closer eye on Atkins. Vaughan and Atkins moved into a house in Englewood, New Jersey.

When Vaughan's contract with Mercury ended in late 1959, she signed on with Roulette, a small label owned by Morris Levy, who was one of the backers of Birdland, where she frequently appeared. She began recording for Roulette in April 1960, making a string of large ensemble albums arranged or conducted by Billy May, Jimmy Jones, Joe Reisman, Quincy Jones, Benny Carter, Lalo Schifrin, and Gerald Wilson. She had pop chart success in 1960 with "Serenata" on Roulette and "Eternally" and "You're My Baby", a couple of residual tracks from her Mercury contract. She recorded After Hours (1961) with guitarist Mundell Lowe and double bassist George Duvivier and Sarah + 2 (1962) with guitarist Barney Kessel and double bassist Joe Comfort.

In 1961 Vaughan and Atkins adopted a daughter, Deborah Lois Atkins, known professionally as Paris Vaughan. However, the relationship with Atkins proved difficult and violent. After several incidents, she filed for divorce in November 1963. She turned to two friends to help sort out the financial affairs of the marriage. Club owner John "Preacher" Wells, a childhood acquaintance, and Clyde "Pumpkin" Golden Jr. discovered that Atkins' gambling and spending had put Vaughan around $150,000 in debt. The Englewood house was seized by the IRS for nonpayment of taxes. Vaughan retained custody of their child and Golden took Atkins' place as Vaughan's manager and lover for the remainder of the decade.

When her contract with Roulette ended in 1963, Vaughan returned to the more familiar confines of Mercury. In the summer of 1963, she went to Denmark with producer Quincy Jones to record Sassy Swings the Tivoli, an album of live performances with her trio. During the next year, she made her first appearance at White House for President Lyndon Johnson. The Tivoli recording would be the brightest moment of her second stint with Mercury. Changing demographics and tastes in the 1960s left jazz musicians with shrinking audiences and inappropriate material. Although she retained a following large and loyal enough to maintain her career, the quality and quantity of her recorded output dwindled as her voice darkened and her skill remained undiminished. At the conclusion of her Mercury deal in 1967, she lacked a recording contract for the remainder of the decade.

1970–82: Fisher and Mainstream

In 1971, at the Tropicana in Las Vegas, Marshall Fisher was a concession stand employee and fan when he was introduced to Sarah Vaughan. They were attracted to each other immediately. Fisher moved in with her in Los Angeles. Although he was white and seven years older, he got along with her friends and family. Although he had no experience in the music business, he became her road manager, then personal manager. But unlike other men and managers, Fisher was devoted to her and meticulously managed her career and treated her well. He wrote love poems to her.

In 1971, Bob Shad, who had worked with her as producer at Mercury, asked her to record for his label, Mainstream, which he had founded after leaving Mercury. Breaking a four-year hiatus, Vaughan signed a contract with Mainstream and returned to the studio for A Time in My Life, a step away from jazz into pop music with songs by Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and Marvin Gaye arranged by Ernie Wilkins. She didn't complain about this eclectic change in direction, but she chose the material for her next album after admiring the work of Michel Legrand. He conducted an orchestra of over one hundred musicians for Sarah Vaughan with Michel Legrand, an album of compositions by Legrand with lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman. The songs brought some of the musicians to tears during the sessions. But Shad wanted a hit, and the album yielded none. She sang a version of the pop hit "Rainy Days and Mondays" by the Carpenters for Feelin' Good. This was followed by Live in Japan, her first live album since 1963. Sarah Vaughan and the Jimmy Rowles Quintet (1974) was more experimental, containing free improvisation and some unconventional scatting.

Send in the Clowns was another attempt to increase sales by breaking into the pop music market. Vaughan disliked the songs and hated the album cover depicting a clown with an afro. She filed a lawsuit against Shad in 1975 on the belief that the cover was inconsistent with the formal, sophisticated image she projected on stage. She also contended that the album Sarah Vaughan: Live at the Holiday Inn Lesotho had an incorrect title and that Shad had been harming her career. Although she disliked the album, she liked the song "Send in the Clowns" written by Steven Sondheim for the musical A Little Night Music. She learned it on piano, made many changes with the help of pianist Carl Schroeder, and it became her signature song.

In 1974, she performed music by George Gershwin at the Hollywood Bowl with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The orchestra was conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas, who was a fan of Vaughan and invited her to perform. Thomas and Vaughan repeated the performance with Thomas' home orchestra in Buffalo, New York, followed by appearances in 1975 and 1976 with other symphony orchestras in the United States.

After leaving Mainstream, she signed with Atlantic and worked on an album of songs by John Lennon and Paul McCartney that were arranged by Marty Paich and his son, David Paich of the rock band Toto. She was enthusiastic to be more involved in the making of an album, but Atlantic rejected it on the claim that it contained no hits. "I don't know how they can recognize hits in advance", she said. Atlantic canceled her contract. She said, "I don't give a damn about record companies any more".

Rio and Norman Granz

In 1977, filmmaker Thomas Guy followed Vaughan on tour to film the documentary Listen to the Sun. She traveled throughout South America: Argentina, Columbia, Chile, Ecuador, and Peru. She was enamored of Brazil, as this was her third tour of Brazil in six years. In the documentary she called the city of Rio "the greatest place I think I've ever been on earth". Audiences were so enthusiastic that she said, "I don't believe they like me that much." After rejection by Atlantic, she wanted to try producing her own album of Brazilian music. She asked Aloísio de Oliveira to run the sessions and recorded I Love Brazil! with Milton Nascimento, Jose Roberto Bertrami, Dorival Caymmi, and Antonio Carlos Jobim.

She had an album but no label to release it, so she signed to Pablo run by Norman Granz. She had known Granz since 1948 when she performed on one of his Jazz at the Philharmonic tours. He was the record producer and manager for Ella Fitzgerald and the owner of Verve. After selling Verve, he started Pablo. He was dedicated to acoustic, mainstream jazz and had recorded Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Clark Terry. In 1978 he recorded Vaughan's How Long Has This Been Going On?, a set of jazz standards with veteran jazz musicians Oscar Peterson, Joe Pass, Ray Brown, and Louis Bellson. The album was nominated for a Grammy Award. Pablo released I Love Brazil! and it, too, was nominated for a Grammy.

1982–89: Late career

In the summer of 1980 she received a plaque on 52nd Street outside the CBS Building (Black Rock) commemorating the jazz clubs she had once frequented on "Swing Street" and which had long since been replaced with office buildings. A performance of her symphonic Gershwin program with the New Jersey Symphony in 1980 was broadcast on PBS and won her an Emmy Award the next year for Individual Achievement, Special Class. She was reunited in 1982 with Tilson Thomas for a modified version of the Gershwin program, played again by the Los Angeles Philharmonic but this time in its home hall, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion; the CBS recording of the concert Gershwin Live! won a Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Performance, Female.

After the end of her contract with Pablo in 1982, she committed to a limited number of studio recordings. She made a guest appearance in 1984 on Barry Manilow's 2:00 AM Paradise Cafe, an album of pastiche compositions with established jazz musicians. In 1984, she participated in The Planet is Alive, Let It Live a symphonic piece composed by Tito Fontana and Sante Palumbo on Italian translations of Polish poems by Karol Wojtyla, better known as Pope John Paul II. The recording was made in Germany with an English translation by writer Gene Lees and was released by Lees on his private label after the recording was rejected by the major labels.

In 1985 Vaughan reconnected with her longstanding, continually growing European audience during a celebratory concert at the Chatelet Theater in Paris. Released posthumously on the Justin Time label, In the City of Lights is a two-disc recording of the concert, which covers the highlights of Vaughan's career while capturing a beloved singer at the height of her powers. Thanks in part to the hard-swinging telepathic support of pianist Frank Collett (who answers each of her challenges then coaxes the same from her), Sarah reprises Tad Dameron's "If You Could See Me Now" with uncommon power, her breathstream effecting a seamless connection between chorus and bridge. For the Gershwin Medley, drummer Harold Jones swaps his brushes for sticks to match energy and forcefulness that does not let up until the last of many encores.

In 1986, Vaughan sang "Happy Talk" and "Bali Ha'i" in the role of Bloody Mary on a studio recording by Kiri Te Kanawa and José Carreras of the score of the Broadway musical South Pacific, while sitting on the studio floor. Vaughan's final album was Brazilian Romance, produced by Sérgio Mendes with songs by Milton Nascimento and Dori Caymmi. It was recorded primarily in the early part of 1987 in New York and Detroit. In 1988, she contributed vocals to an album of Christmas carols recorded by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir with the Utah Symphony Orchestra and sold in Hallmark Cards stores. In 1989, Quincy Jones' album Back on the Block included Vaughan in a brief scatting duet with Ella Fitzgerald. This was her final studio recording. It was her only studio recording with Fitzgerald in a career that had begun 46 years earlier opening for Fitzgerald at the Apollo.

The video Sarah Vaughan Live from Monterey was taped in 1983 or 1984 with her trio and guest soloists. Sass and Brass was taped in 1986 in New Orleans with guests Dizzy Gillespie and Maynard Ferguson. Sarah Vaughan: The Divine One was part of the American Masters series on PBS. Also in 1986, on Independence Day in a program nationally televised on PBS she performed with the National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Mstislav Rostropovich, in a medley of songs composed by George Gershwin.

Death

In 1989, Vaughan's health began to decline, although she rarely revealed any hints of this in her performances. She canceled a series of engagements in Europe in 1989, citing the need to seek treatment for arthritis of the hand, although she was able to complete a series of performances in Japan. During a run at New York's Blue Note Jazz Club in 1989, she was diagnosed with lung cancer and was too ill to finish the last day of what would turn out to be her final series of public performances.

Vaughan returned to her home in California to begin chemotherapy and spent her final months alternating stays in the hospital and at home. She grew weary of the struggle and demanded to be taken home, where at the age of 66 she died on the evening of April 3, 1990, while watching a television movie featuring her daughter.

Her funeral was held at Mount Zion Baptist Church, 208 Broadway in Newark, New Jersey. Following the ceremony, a horse-drawn carriage transported her body to Glendale Cemetery, Bloomfield in New Jersey.

Comments about her voice

Parallels have been drawn between Vaughan's voice and that of opera singers. Jazz singer Betty Carter said that with training Vaughan could have "...gone as far as Leontyne Price." Bob James, Vaughan's musical director in the 1960s said that "...the instrument was there. But the knowledge, the legitimacy of that whole world were not for her ... But if the aria were in Sarah's range she could bring something to it that a classically trained singer could not."

In a chapter devoted to Vaughan in his book Visions of Jazz (2000), critic Gary Giddins described her as the "...ageless voice of modern jazz – of giddy postwar virtuosity, biting wit and fearless caprice". He concluded by saying that "No matter how closely we dissect the particulars of her talent ... we must inevitably end up contemplating in silent awe the most phenomenal of her attributes, the one she was handed at birth, the voice that happens once in a lifetime, perhaps once in several lifetimes."

Her obituary in The New York Times described her as a "singer who brought an operatic splendor to her performances of popular standards and jazz." Jazz singer Mel Tormé said that she had "...the single best vocal instrument of any singer working in the popular field." Her ability was envied by Frank Sinatra who said, "Sassy is so good now that when I listen to her I want to cut my wrists with a dull razor." New York Times critic John S. Wilson said in 1957 that she possessed "what may well be the finest voice ever applied to jazz." It was close to its peak until shortly before her death at the age of 66. Late in life she retained a "youthful suppleness and remarkably luscious timbre" and was capable of the projection of coloratura passages described as "delicate and ringingly high".

Vaughan had a large vocal range of soprano through a female baritone, exceptional body, volume, a variety of vocal textures, and superb and highly personal vocal control. Her ear and sense of pitch were almost perfect, and there were no difficult intervals.

In her later years her voice was described as a "burnished contralto" and as her voice deepened with age her lower register was described as having "shades from a gruff baritone into a rich, juicy contralto". Her use of her contralto register was likened to "dipping into a deep, mysterious well to scoop up a trove of buried riches." Musicologist Henry Pleasants noted, "Vaughan who sings easily down to a contralto low D, ascends to a pure and accurate [soprano] high C."

Vaughan's vibrato was described as "an ornament of uniquely flexible size, shape and duration," a vibrato described as "voluptuous" and "heavy" Vaughan was accomplished in her ability to "fray" or "bend" notes at the extremities of her vocal range. It was noted in a 1972 performance of Leslie Bricusse and Lionel Bart's "Where Is Love?" that "In mid-tune she began twisting the song, swinging from the incredible cello tones of her bottom register, skyrocketing to the wispy pianissimos of her top."

She held a microphone in live performance, using its placement as part of her performance. Her placings of the microphone allowed her to complement her volume and vocal texture, often holding the microphone at arm's length and moving it to alter her volume.