#Chan Master Sheng Yen

Text

Even monks and nuns can lose the energy of a deep experience, but it is much more difficult for lay people to retain it. In Chan there is a verse:

To hear the Buddha Dharma is not very difficult.

More difficult is it to practice.

To practice is not very difficult.

More difficult is it to realize the Path.

To realize the Path is not very difficult.

More difficult is it to not fall from the Path.

There is also a saying: "When you have gotten the Buddha-mind go to the woods, live by a stream and meditate; thus will you nourish your saintly embryo." When will this baby be born? You don't know.

But, like an expectant mother, you must nourish the saintly embryo.

-- Master Sheng Yen, Getting the Buddha Mind

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“When he sat, his stillness made his body resemble a block of dry wood. Hung Chih, calling his method “Silent Illumination,” describes it as follows: “Your body sits silently; your mind, quiescent, unmoving. Your mouth is so still that moss grows around it. Grass sprouts from your tongue. Do this without cease, cleansing the mind until it gains the clarity of an autumn pool, bright as the moon illuminating the evening sky.”

The Poetry of Enlightenment: Poems by Ancient Chan Masters

Chan Master Sheng Yen

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Steps to Magical Powers

Before you fully embark on the path of the bodhisattvas and buddhas, says Chan master Sheng Yen, you must first practice the four steps to magical powers. What are these steps and what are the magical powers you need?

The four steps to magical powers are also called by such names as the four steps to the power of ubiquity, the four steps to unlimited power, and the four kinds of samadhi. In…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#surefire#thyrm#spyderco#Beretta#iphone11maxpro#budhist#tibetan book of the dead#lenovo yoga#Chan practice#Chan Master Sheng Yen#S&J Inspection ServicesLLP

0 notes

Text

Why do Buddhist monks and nuns have to shave their heads?

youtube

Master Shèngyán 聖嚴.

Five Desires according to the Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism:

(1) The desires that arise from the contact of the five sense organs (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and body) with their respective objects (color and form, sound, smell, taste, and texture).

(2) The desires for wealth, sexual love, food and drink, fame, and sleep.

1 note

·

View note

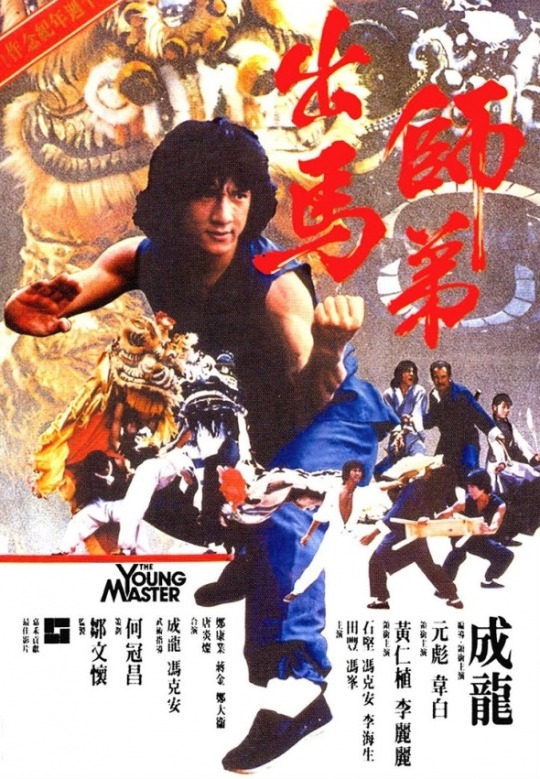

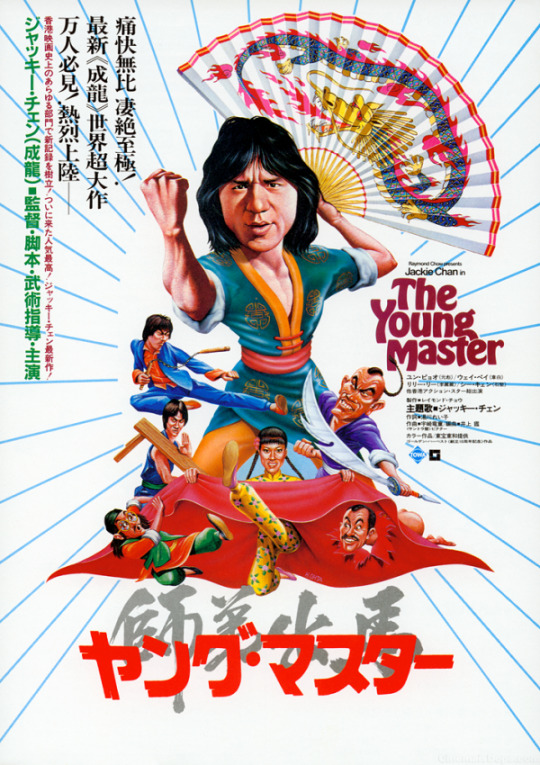

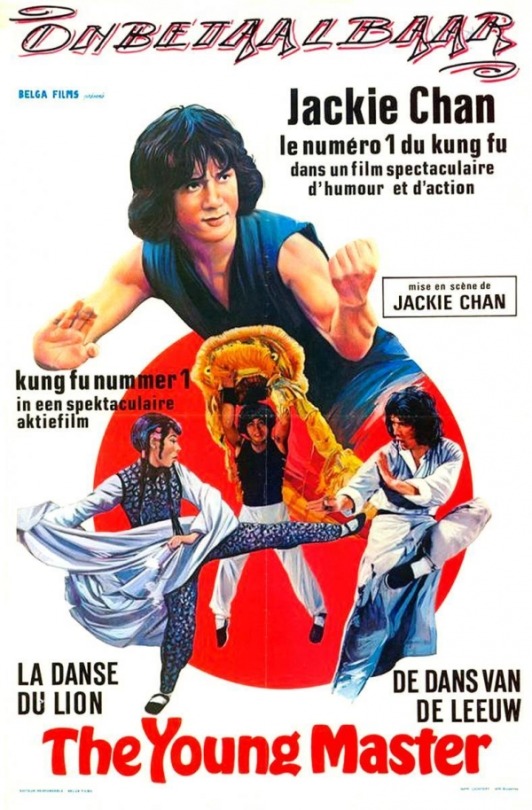

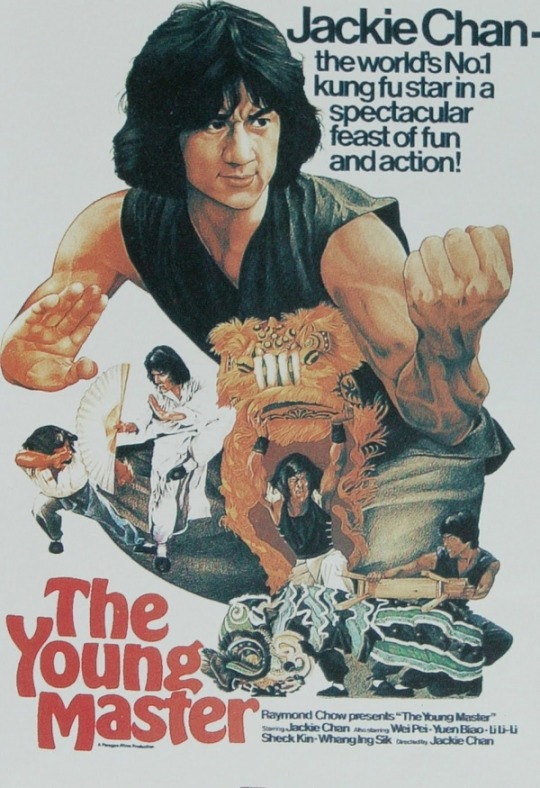

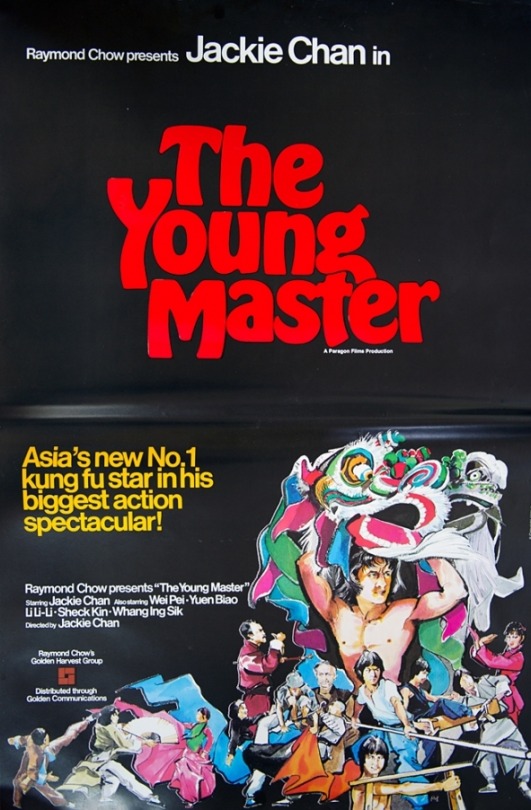

Photo

The Young Master 1980

#The Young Master#Jackie Chan#Biao Yuen#Pai Wei#Lily Li#Kien Shih#Ing-Sik Whang#Hark-On Fung#Hoi Sang Lee#Feng Tien#Fung Fung#Mei Sheng Fan#Yen Tsan Tang#Poster

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

When we say that Chan does not rely on words, we mean that Chan does not depend on what has been spoken or written in the past. If we recognize that there is no need to believe even the words of Sakyamuni Buddha, we can approach Chan unencumbered by what we have heard and what we have read. Other religions and schools of philosophy wrestle with considerable verbiage. Chan advocates throwing everything away. When you practice, leave the past behind—what you have read, heard and experienced.

- Master Sheng Yen

#buddhism#zen#buddhist#quotes#mindfulness#meditation#chan#enlightenment#buddha#bodhi#wisdom#nirvana#zazen#compassion#dharma#happiness#awakening#samsara#spiritual#peace#bodhisattva#buddha nature#Sheng yen

22 notes

·

View notes

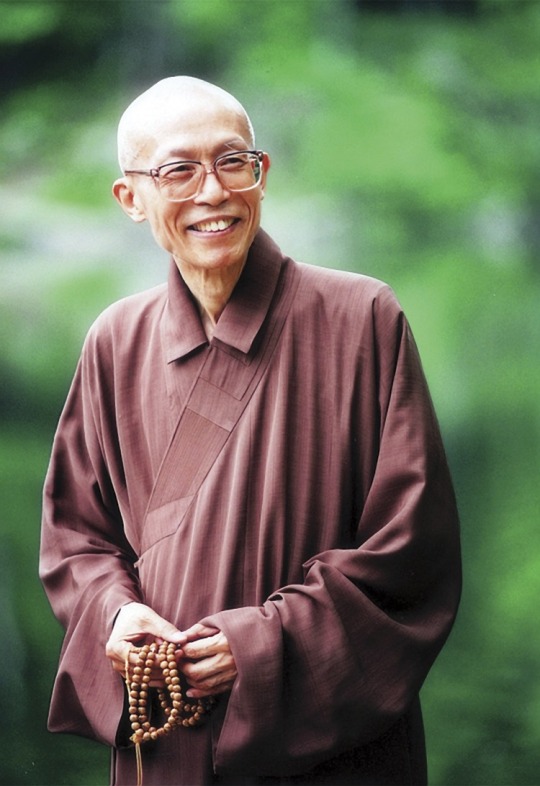

Photo

"Enlightenment is not something special — it is the natural freedom of this moment, here and now, unstained by our fabrications." You Are Already Enlightened Guo Gu, a longtime student of the late Master Sheng Yen, presents an experiential look at the Chan practice of silent illumination. read more

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buddhist heavens

In his book, Orthodox Chinese Buddhism, Chan Master Sheng Yen explains the various Buddhist heavens.

Gods, live in the twenty-eight heavens. All of the good deities in the three realms who are rulers in the twenty-eight heavens) are believers in and protectors of Buddhism. Gods live happily in the heavens because of their good karma from previous lives. The heavens, according to Buddhism, are comprised of twenty-eight levels, which extend throughout the three realms.

Closest to the human realm are the six heavens in the realm of sense desire. This realm includes the lowest six heavens.

Pleasure of the Transformations of Others (tā huà zìzài tiān 他化自在天): A heaven where one can fulfill desires by one’s magical transformations and by others’ magical transformations. In addition, the god Māra lives here.

Pleasure of Transformations (huà lè tiān 化樂天): A heaven where one can fulfill desires by magical transformations.

Tusita (dōushuài tiān 兜率天): A heaven of contentment in regard to sense desires. A bodhisattva in her life prior to the one in which she attains Buddhahood dwells in this heaven.

Yāma (yèmó tiān 夜摩天): The “auspicious” heaven, where the gods are continually singing. This heaven and those above it are called aerial heavens, as they are located above ground. Layers of clouds support them from below.

Trāyastrimśa (dāolì tiān 忉利天): This where the god Śakra (also called Indra) rules, along with his thirty-two ministers, as well as their subjects. It is located on the square, flat summit of Mount Sumeru. Śakra lives in the Palace of Victory in the center of the city of Lovely View, and his thirty-two ministers live in separate palaces outside the city walls.

Four Divine Kings and their subjects (sì tiānwáng tiān 四天王天): This “heaven” actually comprises four different locations, and is sometimes divided into four different heavens. The highest of the four is that of the four divine kings; the lower three are for the servants of these kings. These heavens are located on terraces along the slopes of Mount Sumeru.

By merely performing good deeds, at most one can be reborn in the six heavens within the realm of sense desire. Beings in this realm are, to a greater or lesser degree, bound by desires of the five senses.

Above these are the eighteen heavens in the realm of form.

Fourth Dhyāna Heavens

Ultimate Form (sè jiūjìng tiān 色究竟天): The highest place for those domains in which material form is present.

Skillful Manifestation (shàn xiàn tiān 善現天): Deities here are supremely proficient at manifesting themselves as they wish.

Skillful Vision (shàn jiàn tiān 善見天): Obstacles to samādhi here are very weak, so one can see clearly and penetratingly.

No Heat (wú rè tiān 無熱天): There is no “heat” of misery and distress here.

No Affliction (wú fán tiān 無煩天): There are no afflictions here.

Extensive Fruits (guaˇng guoˇ tiān 廣果天): For those with extensive karmic rewards, the fruits of previous action.

Without Perception (wú xiaˇng tiān 無想天): Those born here are without the functioning of mental perception, the goal of some non-Buddhist ascetics. But after enjoying a stay here of five hundred kalpas, the inhabitants develop deviant views and descend into the hells.

Born of Blessings (fú shēng tiān 福生天): For those of superb blessings.

Cloudless (wú yún tiān 無雲天): This heaven is beyond (unsupported by) clouds. All the aerial heavens below this one are supported by clouds; this heaven and those above it rest on space alone.

Third Dhyāna Heavens

Universal Purity (piàn jìng tiān 遍淨天): Gods here commit no impure deeds.

Infinite Purity (wúliàng jìng tiān 無量淨天): Gods here are even greater in degree of purity than those in the preceding heaven.

Lesser Purity (shaˇo jìng tiān 少淨天): Purity in the sense of renouncing sense pleasures; “lesser” in contrast to the heaven above it.

Second Dhyāna Heavens

Light-Sound (guāng yīn tiān 光音天): In this heaven, words come out from the gods’ mouths not as sound but as light, through which they communicate.

Infinite Light (wúliàng guāng tiān 無量光天): Great light pervades this heaven.

Lesser Light (shaˇo guāng tiān 少光天): A lesser amount of light pervades this heaven.

First Dhyāna Heavens

Great Brahmās (dà fàn tiān 大梵天): The deities here are called great Brahmās; they act as rulers.

Brahmā-Ministers (fàn fuˇ tiān 梵輔天): The Brahmās here act as ministers to the great Brahmās.

Brahmā-Plebians (fàn zhòng tiān 梵䱾天): These Brahmās serve as the commoners among the hierarchy of Brahmās.

The highest five heavens in the realm of form are the pure abodes: these are the heavens in which the noble ones called anāgāmins (or “non-returners”), who have attained the third fruit of the Nikāya path to liberation and are destined to achieve arhatship, are reborn. Other than these five, the remaining heavens in the realms of form and formlessness are for those who attained high levels of concentration through meditation.

Further up are the four heavens in the realm of formlessness.

Neither Perception nor Non-Perception (fēi fēi xiaˇng chù 非非想處)

Nothingness (wú suoˇyoˇu chù 無所有處),

Infinite Consciousness (shì chù 識處)

Infinite Space (kōng chù 空處).

Meditators who successfully cultivate one of the four formless absorptions are reborn in one of these four heavens. The name of each heaven describes the object of perception of the inhabitants. The gods dwelling in these realms are devoid of bodies, and these heavens are not physical places.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"The Masters by Manuel J. Iniesta Los cuatro grandes maestros de las artes marciales. -Bruce Lee, nacido en San Francisco, criado en Hong Kong maestro de artes marciales, actor, cineasta, filósofo y escritor estadounidense de origen chino, reconocido en el mundo entero por ser el renovador y exponente de las artes marciales dedicando su vida a dicha disciplina, buscando la perfección y la verdad, llegando a crear su propio método de combate y filosofía de vida, el Jun Fan Gung-Fu, que tiempo después y sumado a su concepto filosófico se llamaría, el Jeet Kune Do (el camino del puño interceptor) -Jackie Chan, es un artista marcial, comediante, cantante, actor, acróbata, doble de acción, coordinador de dobles de acción, director, guionista, productor y actor de voz chino. Nacido en Hong Kong donde le pusieron por nombre «Gang Sheng», el cual significa «Nacido en Hong Kong», aunque en China se le conoce mucho más por su nombre cantonés: «Sheng Lon». Su familia es de Yantai, una ciudad que se caracteriza por haber sido cuna de grandes luchadores. -Jet Li, artista marcial, actor y productor chino, nacionalizado singapurense en 2009. Después de retirarse a la edad de 17 años del wushu, disciplina en la que ganó 15 medallas de oro y se retiró invicto, debutó como actor en la película El templo de Shaolin. Estrella del cine internacional, protagonizó muchas películas de artes marciales aclamadas por la crítica, entre ellas la saga de Wong Fei Hung. -Donnie Yen, artista marcial, actor y coreógrafo chino. Considerado por muchos como la mayor estrella del cine de acción de Hong Kong y uno de los actores más rentables de Asia. Antiguo medallista olímpico de wushu. En contraste con otros actores asiáticos de artes marciales, Yen destaca en la gran pantalla por su estilo violento y técnico a la par, protagonizando coreografías de gran intensidad. #arte #art #draw #drawing #jetli #donnieyen #brucelee #jackiechan #artesmarciales #martialarts #manueljiniesta (en Málaga, Spain) https://www.instagram.com/p/BzzkV4_CyO2/?igshid=tgfot0gyljr0

#arte#art#draw#drawing#jetli#donnieyen#brucelee#jackiechan#artesmarciales#martialarts#manueljiniesta

2 notes

·

View notes

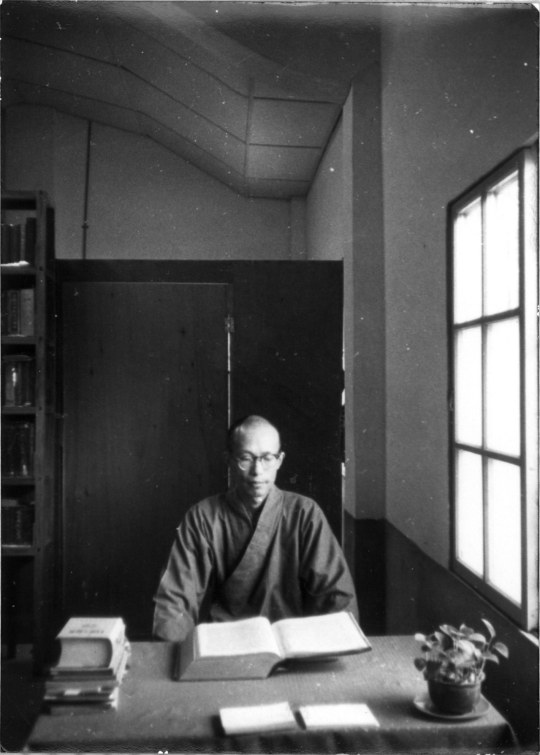

Photo

【#聖嚴法師~#心靈環保法語】 踏實的體驗生命, 就是禪修。 To wholly experience life is to practice Chan. ---聖嚴法師 Master Sheng Yen https://www.instagram.com/p/B1lsMm6nFUw/?igshid=x842diq9uod5

0 notes

Text

Meditative Methods in Different Schools

Through the spread of Buddhism to various cultures, different schools of Buddhism have appeared, with each of them developing its own form of meditation. For instance, Yogacara, the mind-only school founded by Asanga, stresses a meditative concentration as the way of accessing reality (Duoer, 10 July 2019). This school holds the view that cognition is not passively produced by sensing the world; instead, it is constructed by consciousness, in order words, the mind itself (Duoer, 10 July 2019). This problem of consciousness can be solved only through continuous meditation, which helps complete enlightenment.

youtube

Meditation in Daoism

(Get this video from www.youtube.com/watch?v=yG1tPj4baVE, published on Jan 23, 2018 by George Thompson.)

Other schools in different cultures also use meditation as a means of practice. Some even incorporates their own tradition with the arrival of Buddhism to create new forms of meditation. For instance, in China, it was the combination of Daoism with Buddhism that gave rise to the uniqueness of its meditation form (Shaw, 193). Created by Laozi, Daoism is a self-conscious tradition that stresses respect for the power of nature (Shaw, 191). At the time Daoism appeared, Buddhism entered China, with its emphasis on spiritual life and meditation (Shaw, 190). Taoists practice alchemy and explore the breath and energy circulation that is related to the life force (qi), which attracted Buddhists, whose meditative methods also emphasized breath and concentration (Shaw, 191). Although Buddhism is in a religious system, and Daoism belongs to traditions in a country, they all stress the control of breath. Thus, these two are strongly related to each other. Moreover, as Buddhism, Daoism also welcomed monasticism, constructing its own temple with Laozi been regarded as a similar figure of the Buddha (Shaw, 191). The combination of Daoism views toward Buddhism developed in China, especially its meditative method, unique among other forms. However, due to the new arrival, difficulties emerged as people studied meditative terminology from India since they could not figure out how to translate them (Shaw, 192). As a result, people set out to search for the best way to decipher terms associated with meditative states. Over the course of exploration, Buddhism also developed, leading to the appearance of four major schools of Chinese Buddhism: Tiantai, Huayan, Chan, and Pure Land (Shaw, 193). Based on the whole Chinese meditative practice, each of them created its own form of meditation.

youtube

Chan Meditation

(Get this video from www.youtube.com/watch?v=k0bGu_hTEpQ, published on Apr 5, 2012, by Master Sheng Yen)

youtube

Meditation in Pure Land school

(Get this video from www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ig8p87Y6OKI, published on Feb 8, 2008, by InvisibleSatsang)

For Tiantai school, its meditative method is based on the Mahayana idea of emptiness (Shaw, 193). In other words, it explores the border of being something and not being something (Duoer, 17 July 2019). Practitioners should contemplate the relationship between upaya (skillful means) and the ultimate truth to attain the state which is between delusion and wisdom (Duoer, 17 July 2019). In Chan Buddhism, in order to become a buddha, sentient beings need to practice meditation (Duoer, 18 July 2019). Chan meditation places an emphasis on Tantian, the area below the navel (Shaw, 202). This emphasis is associated with alchemical practice in Daoism since Daoist uses meditation to accomplish alchemical practice, which aims at immortality (Shaw, 203). In Huayan school, buddhas have strong meditative power to create infinite forms to be compassionate (Duoer, 16 July 2019). In Pure Land school, in which an easy way of attaining enlightenment exist, practitioners meditate on the Amitabha Buddha by continuing saying Namo Amitabha Buddha (Duoer, 15 July 2019).

As is shown above, no matter how many schools are derived from Buddhism or how each school differs from one another, the practice of meditation exists everywhere, with emphasis placed on different meditative methods. In Buddhism, this practice method serves as a significant means for practitioners to reach the goal of nirvana, the state of enlightenment, and to control the mind, even though there is diversity of the specific patterns of manifestation.

0 notes

Text

Varieties of Enlightenment

Back in the mid-seventies I was in the Air Force, and was stationed on Pope Air Force Base near Fort Bragg, a huge army base covering over 200 square miles of central North Carolina. I was 18 years old and bored out of my mind. The military had thoroughly corrupted the nearby town of Fayetteville and my only reprieve from boredom was to drive to the coast on Friday evening and spend the weekend on the beaches of Cape Hatteras and Okracoke Island. Laying on the beach at night listening to the ocean waves lulled my mind to a restful state just at the cusp of sleep. Even though I never seemed to fully fall asleep, I always seemed to rise with the first sunlight coming over the flat, watery horizon feeling refreshed. I felt very awake, aware, and alive. This feeling seemed to last throughout the day and even into the first day or two of the work week. By Friday, the effect had worn off and I was ready for another trip to the Outer Banks.

After I got out of the Air Force in May of ‘76, I moved out to Colorado Springs where my sister was living to look for a job. I wasn’t able to find a job but did go on some great back-packing trips with my brother-in-law. Up in the Rockies as you climb the trails, the wind blowing through the aspens and conifers sings enchanting songs, calming and pacifying the mind. There is no desire to think of anything but the sound of rustling leaves high above, whispers through fir needles, the scent of pine and loamy soil, and the slow, rhythmic pace of footsteps and breathing. It was effortless to be deeply settled in the present moment and more fully aware of self and environment. Running streams chanted in a thousand tongues all singing praise to each fleeting moment. I found these backpacking trips as necessary as sleeping and eating. They were healing, nature itself the doctor. They addressed a deep longing that I didn’t even know that I had and all I knew was that I wanted more of this sweet contentment that the mountains offered.

I briefly moved back to my home town in Illinois and found a job in a machine shop. I was a terrible mill operator and was soon let go, but while I was living there I went into the Karmel Korn shop I used to visit as a kid and saw a book called The TM Book. I was fascinated by the name, “Transcendental Meditation”. What does it mean? What would it be like to “transcend” thought? A few weeks later, I had returned to my pre-Air Force employer in Springfield, Illinois and as I was walking down the street, I saw a poster with Maharish Mahesh Yogi’s portrait on it and the words “Transcendental Meditation - Public Lecture”. It was that very evening. I attended the two introductory lectures and on Saturday morning found myself witnessing a puja to Guru Dev, Maharishi’s master, and was given a one syllable mantra to repeat to myself in a small room as I was sitting on a chair. Soon my hands folded on my lap seemed to be far below me and I could hear sounds from the neighborhood with fascinating clarity. The mantra seemed to be repeating in my mind automatically with no effort on my part and I felt completely serene, paralyzed. The teacher then asked how I was doing and I told him, “Fine.” He said, “This is how we meditate”. I continued to meditate using the mantra I was given for many years.

I missed Colorado and soon moved back. While there I took a “Science of Creative Intelligence” class at the Colorado Springs TM center. The people were unlike any I had ever met before and I felt so comfortable with them all -- a retired colonel, the wife of a surgeon, a college student, another retired couple, and couple that were TM teachers, along with Ron Carpenter, the head of the center. I saw a Maharishi International University catalog at the center and knew I had to go there.

In January of 1978, I started my freshman year at MIU (later renamed to Maharishi University of Management). In the summer of ‘79, I went on an extended retreat to learn the TM Siddhi program and soon found myself meditating twice a day with about a thousand other “siddhas” in the “Golden Dome”, a huge meditation hall (or flying hall as we called it). After doing a quick set of yoga asanas and pranayama in my dorm room, I would walk with all the other meditators to the dome and practice TM and the Siddhis. I remember mornings and afternoons in the dome when I felt that there was nothing more I need do in this life so great was the feeling of contentment during meditation.

While at MIU (MUM), I listened to hundreds of hours of Maharishi videos as part of “Forest Academy” retreats that were part of the curriculum. Maharishi delineated seven states of consciousness in some of the lectures:

Waking

Dreaming

Sleeping

Pure Consciousness - A state of “restful alertness” experienced during the practice of meditation when thoughts and mantra subside and consciousness is simply self-aware.

Cosmic Consciousness (CC) - A state when Pure Consciousness becomes infused into the waking state giving the rise to “unbounded awareness”. This is a state when the awareness of the Self is maintained during normal activity. It is called “cosmic” because it includes the awareness of the subject and object of perception, i.e., the experiencer is never “overshadowed” by perception and even dynamic activity.

God Consciousness (GC) - As one becomes established in Cosmic Consciousness, the senses continue to refine giving rise to greater and greater appreciation of subtler and subtler levels of perception. This eventually brings about the perception of the celestial or divine aspects present in the phenomenal world and causes the heart to expand in love for the divine.

Unity Consciousness (UC) - With the rise of God Consciousness, the separation between the subject and object, the knower and the known, eventually dissolves. One perceives the world without duality and feels one with the surroundings. As this state unfolds, one feels one with the entire universe and realizes the mahavakya “Aham Brahmasmi” -- I am Brahman. This realization is also know as Brahman Consciousness (BC).

Of course, we at MIU had no doubt that Maharishi and his teacher, Guru Dev (Swami Brahmananda Saraswati) were in Brahman Consciousness and took everything that Maharishi said as being unquestionably true. How could an enlightened being say something that was not true?

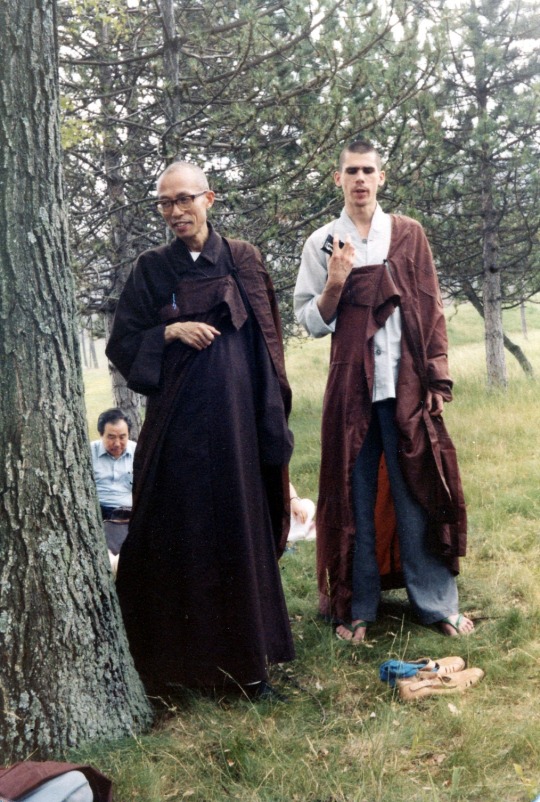

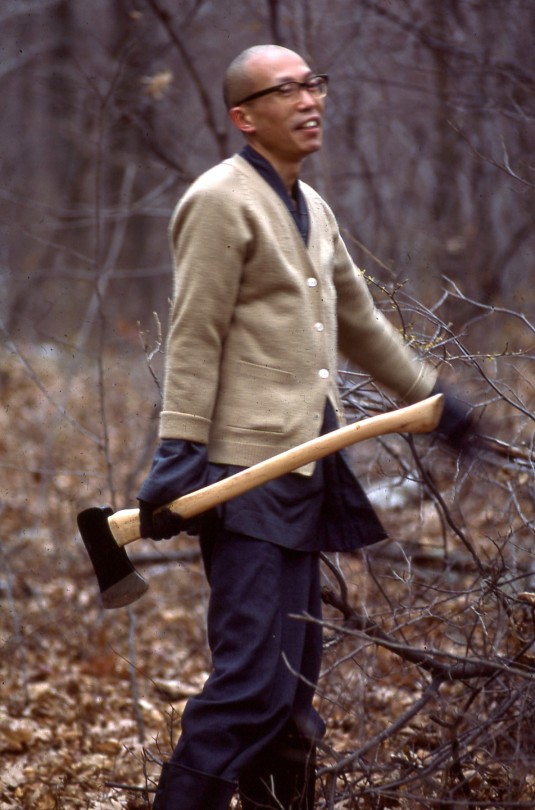

After graduating from MIU, I moved to Taiwan to learn Chinese and taught English for a living. While there, I met a Chinese monk, Venerable Master Sheng-yen, who had received dharma transmission from two different Chan lineages, the Caodong (Soto) and the Linjii (Rinzai) traditions of Chan (Chinese Zen) Buddhism, that is, his masters verified that he had the correct and authentic experience of self-nature and was qualified to teach others. I began attending his Sunday lectures and soon found myself on a seven day Chan retreat in New York City while I had briefly returned to the US. At first I was reluctant to give up the practice of TM and the Siddhis but became aware that I had become very attached to the practice. A nun reasoned with me, “If you can pick something up, you can also put it down -- and you can pick it up again.” I was reluctant. On the second day of the retreat, Master Sheng-yen (Shifu), asked me to just meditate by following my breath. I agreed, thinking that after 9 years of practicing TM, it would be easy. It wasn’t. Pain in my legs at times was unbearable and I was beginning to think that Chan Buddhists were masochists. But, something about Shifu made me fully trust him and I persisted with this practice for several years.

It was during this time that I experience inner conflict regarding seemingly opposing religious traditions I had been exposed to. I had grown up as a Catholic, pretty much became a Vedantic yogi while at MIU, and suddenly found myself very seriously desiring to become a Buddhist monk out of shear trust of my Shifu, Master Sheng-yen. Shifu was an incredible man. When he lectured, you always thought he was talking to you personally. And when he was talking to you, he seemed completely and genuinely interested in you, in your well-being without concern for himself. While I deeply admired this selfless quality, it ran contrary to my education from Maharishi. While the Maharishi proclaimed, “All love is directed toward the self”, the Buddha proclaimed that there is no independently existing person, self, or soul. All the Chan and Zen literature seemed to point to this as fact. My own Shifu seemed to be completely selfless and full of compassion for others. What would it be like to experience “no self”? I was intrigued and apprehensive at the same time. And how could Maharishi say that the ultimate reality was Brahman when the Buddha and my Shifu proclaimed that there is no such thing? How could there be no Creator? It was so obvious that there was intelligence of a supreme order in the universe. These questions gnawed at me for quite some time.

Eventually, my recourse was to look back at my own Christian tradition for answers. I went through a period where I read meditative and contemplative works by Thomas Merton, Fr. Basil Pennington, Thomas Keating, Catherine Doherty and others for answers. I eventually became interested in meditative tradition of Eastern Orthodox Christianity and even enrolled in a three year program to become a deacon. After the first semester, I faced quiet a crisis. I had read so many books that were required reading on the history of the church and its doctrines and while on vacation at Lake Tahoe, I suddenly realized that I simply didn’t believe in most of the Christian dogma. It was like a balloon was popped and Christianity just vanished before my eyes.

I began studying Buddhist and Indian literature much more seriously to find out how so many obviously enlightened masters could experience a different enlightenment than what Maharishi had laid out. How could there be multiple enlightenments? How can one person experience enlightenment and proclaim that it is Brahman and another experience enlightenment and say that it is void of Self? As I read more about the different schools of Buddhism, I found that even they didn’t agree on what the experience of Nirvana was. The Theravada Buddhist present Nirvana one way and the Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist present it other ways. So how can the experience of Nirvana be different?

I decided that the only way I would know the truth was to experience it myself. In 2005, I rededicated myself to practicing meditation and started attending Chan retreats at Dharma Drum Retreat Center in Pine Bush, New York. After several retreats, my experience and confidence in the Chan Buddhist tradition deepened significantly. I also went to Vipassina retreats held at the Chanmyay Satipatthana Vihara in Springfield, Illinois, which I felt were extremely helpful in understanding the experience of no self and loosing the fear of this experience. The last retreat I went on was in December of 2009, and this retreat brought about an experience that has made my faith in Buddhism unshakable.

So why am I on a traditional yoga teacher training course? After practicing meditation for many years, I reached a point where I could no longer bear to not help others learn to meditate. There is so much confusion and suffering in the world that is so unnecessary. Through meditation and adapting a lifestyle conducive to its practice, confusion and suffering begin to fall away. At the request of the former abbot of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center (DDRC), Ven. Guo Jun, I began leading a meditation group in Fort Wayne, Indiana (and now in Elk Grove, California). People get together and practice meditation together once every couple weeks or so. Meanwhile, I started practicing yoga again in Elk Grove after joining a fitness club to address health concerns and rediscovered that it was a great way to practice mindfulness and settle down before meditation. Yoga was incorporated into the Chan retreats at DDRC for this reason. The people that attend the meditation sessions I host have a lot of trouble with restlessness and I thought it would be great to incorporate yoga into our meditation practice. Then, I got laid off and was given a Borders Books gift card for my birthday. It was then that I found Srivatsa Ramaswami’s book, The Complete Book of Vinyasa Yoga, and then found his website and the 200 Hour Yoga Teacher Training course offered at LMU. So, hear I am!

Being on this course, I’ve run into a whole new set of philosophies to reconcile. In Ramaswami’s Yoga Sutras class, it became apparent that the Yoga of Patanjali was not the yoga I had learned from Maharishi years ago. Patanjali is said to have written the Yoga Sutras to clarify what had become a morass of conflicting yogic philosophies in India. It was also a reaction to challenges to “orthodox” Indian philosophy from Jain and Buddhist sources. But, in clarifying yoga, Patanjali actually set it apart from Vedantic Brahmanism while introducing a devotional path for those so inclined as well as a purely meditative path for those that do not accept the notion of a Creator God. Patanjali’s Yoga reaches its culmination in the realization of the individual self (atman) as separate from the universal Self. According to Patanjali, enlightenment is a state of duality in which the individual Self is separate from all other phenomena, including the universal Self. The Vedantic tradition sees this duality as the last vestige of ignorance and seeks to remove it. Circling back to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s teaching, the dualism of Patanjali is equivalent to the state of Cosmic Consciousness. It is a state of liberation, but not a fully enlightened state of Unity (or Brahman) Consciousness.

From the Chan Buddhist perspective, the experience of Unity Consciousness is also recognized as a state of liberation and a highly enlightened state. In fact, meditators on Chan retreats that I have attended have had clear experiences of Unity Consciousness, experiencing oneness with the environment. Yet this is not seen as the goal of Chan enlightenment. When meditators go to the retreat master with experiences of oneness with the environment or even the universe, they are told to go back and work harder.

There comes a time when even this oneness falls away and any attachment to the notion of self (individual or universal) evaporates. The Chan retreats use a meditation technique that is sometimes referred to as “The Method of No Method” (refer to my Shifu’s book of this name) or Silent Illumination (Chinese: Muo Zhao). This method requires that the meditator already be able to stay with the object of meditation without problem, i.e., Dhyana, from which the Chinese word Chan is derived. After following the breath and attaining what is referred to as “unifed mind”, the practitioner changes the object of meditation to the entire body and sits with full awareness of the body “just sitting”. As the meditator continues this practice, the distinction of where the body ends and where the environment begins becomes blurred and begins to evaporate completely. During this second stage, the meditator feels as though the body is the entire room. As sounds come from beyond the room, the distinction again falls away and what is beyond the room also is perceived to be all within ones own awareness. This continues until there is a feeling of complete oneness with the environment. Even as the meditator walks to the dining hall, washes the dishes, or lays down to rest, this feeling of oneness with the objects of perception can persist, even extending to the sun, moon, stars, and universe.

To move beyond this experience of unity with the phenomenal world, some retreat masters will use a technique known as “Direct Contemplation” and have the practitioners focus on an object in the natural world with bare awareness. When the meditator is ripe for such a technique, even the unified subject/object relationship begins to melt. It’s as if perception pivots on itself and looses the need of a perceiver. The subject of perception fades and only the object remains. The phenomenal world becomes fully illumined by silence and all of nature comes alive, all things infinitely correlated with all other things, all speaking to all other with perfect fluidity. A cosmic orchestra of mutually supporting, ever changing phenomena penetrated by silence. It is a state of absolute perfection and contentment devoid of any attachment to self or any object of perception. In Chan literature, it is said to be beyond words, yet there are some very beautiful poems by Chan masters that beautifully give glimpses of this state.

So who is to say that the experience of Brahman is any different? Does the person that experiences the mahavakya, “Aham Brahmasmi”, experience anything differently that the Chan practitioner of the highest calibre? Does he still identify with a universal Self? Is there still attachment or clinging to Self? I leave this for you to ponder, or better yet to penetrate.

While there are different paths to enlightenment and different levels of enlightenment, ultimately at the highest level they cannot be different. Experiencing silence between waves at the sea shore or feeling a vague oneness with the wind and trees in the mountains could be called a dawning of awakening. Experiencing mind totally content to stay with the object of meditation is a level of enlightenment. Effortlessly maintaining constant awareness of oneself during activity is another level and loosing awareness of that self is yet another, higher level. When one has no more to do for oneself but can only think of helping others out of suffering, this is higher still. Realizing there is no suffering is still higher.

There cannot be different ultimate truths. I believe all spiritual paths may ultimately lead to one truth. As we say in the Mid-West, some paths may be “taking the long way around the barn”, but they all lead to the other side. My own path around the barn has been a long and winding one. May your path to the supreme truth be as direct and sweet as possible!

1 note

·

View note

Text

World Chan conference.

World Chan conference.

I have been doing some study on-line with a teacher from the Chan linage of Sheng Yen. Beishi Guohan is the head teacher and founder in the Cosmos Chan Community. A few months ago Guohan Shifu mentioned that he was coming to Kyoto to see some Zen temples. I offered to help him get to Kyoto. This week he arrived, I was contacted and asked if he could met any Zen Masters or monks. I said I only know of a couple and only one in my area. Even though I have some issues with him as a Zen Master, he still has the credentials, even if not the heart. In my opinion.

Moving on...

Although pretty much last minute, the arrangements were made. Guohan Shifu, his wife, and myself would go over to the Marina and meet with Aoki "Shacho" (company president).

I was somewhat fretful the night before, I am not big on meeting new people. What will we talk about? Ok well Chan, but meeting with a master, am I suppose to ask some deep questions or something? Slowly slowly slowly I let it go, and just did what I needed to do, rolled with it.

I arrived at the agreed place but the Shifu was not there. He had arrived very early, him and his wife were out and about, looking at stuff. I messaged them and we hooked up. It was comfortable meeting him. He is sort of quiet, so I felt somewhat pressed to speak. I asked the general stuff and the three of us chatted comfortably. I really liked his wife, she reminded me of my Kung Fu auntie in Oakland.

When she found out I could speak some Chinese she helped me with a few things. At the end of the day she gave me a Jade, necklace for my wife.

One of the things I wanted to ask The shifu, well really the only thing. "What is the meaning of life"?

I had seen this questions posted by a Buddhist Meetup group. I had seen this posted in another form by a Muslim, I recall this from my Christian days. Christians say "to bring glory to God", Muslim: "To know God" ( something like that), my teacher's answer was," to know truth". To me this could all be the same thing. It was not the mind blowing answer, I hoping for, but not a surprising answer.

We made our way over to the Aoki boat yard, where we were greeted and offered tea. There we chat a little before heading out to lunch. It was decided that we would go to the Indian Restaurant we go to was nearby and we could get veggie foods for Shifu and myself. Once there my friend the manager, made both myself and Shifu some thing special. It is good to have a connection.

So the world Chan conference began. China, Japan and American representatives :-) We had a nice chat about this and that, reasons for starting Chan, temples, masters, etc. At one point Aoki Shacho had to leave there were things to do back at the Boat yard. I found out later there was an interview. Anyway it was fine. I sat with the Shifu and his wife a while longer. Then we left.

We walked to the train station and I rode with them to the airport, where they made the connection to return to Kyoto where they were staying. I was invited to come visit them in Taipei. I liked them both. They were both approachable and down to earth. I will be continuing to study with Shifu Gouhan. Perhaps I have found my true Chan teacher...when the student is ready kind of thing.

As for going to Taiwan, that could be a very cool thing and affordable for at least one visit. I can visit both my Chan shifus, I can stay at one of the temples for sure and people from the Heart Chan group will take me/us around as family. Also I have I believe a Kung Fu Uncle there who I could visit maybe train a bit with him. I am pretty sure Ling Sisuk sometimes goes to Taiwan for training, he could get me a hookup. I was told there are more and more vegetarians there in Tawain now so a lot of places to eat. I could get a lot of bang for a few days of low spending. Hmmm something to think about. LZ is up for a visit. I would need at least 4 days. One day for Kung Fu training , two days for the Chan temples, sight seeing one day, hmmmm. Ok maybe a week. Maybe we could go together and I can stay a couple of days extra for training. Something to think about anyway.

Anyway as far as Chan study, it is good to have a teacher again, someone I respect, I can grow now, I told my Abbott I would continue to train. My Heart Chan Shifu, Wujue Miaotian from Tawain does not speak English and I am not really in touch with the Ca group, it is hard to connect via on-line teachings, with the time factor. I am still connected but my path is different, I am not feeling somethings about that path. The group of Hsu Yun, my teacher there passed away. The group seems to have stalled, I see no future for me with them further. It is as Gouhan Shifu would say, a Karmic connection that has connected me with his group. (PS: Anyone interested in dharma classes free on-line drop me a note). I find it interesting that part of the training that I wanted to do in Japan was Zen, but my training is coming still from the Chinese path, even being in Japan.

0 notes

Text

Persons traveling the path to Buddhahood must cultivate the great wisdom and compassion that sees all beings as one body with themselves. This is not just wishful thinking or philosophical speculation, but a sincere motivation that inspires our actions and compels us to live humanely in the world.

- Chan Master Sheng Yen

35 notes

·

View notes