#Civil War | Army | RSF Paramilitary

Text

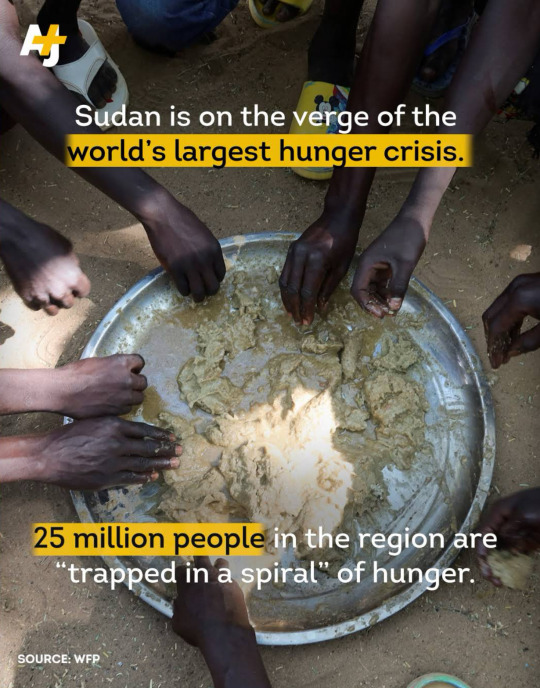

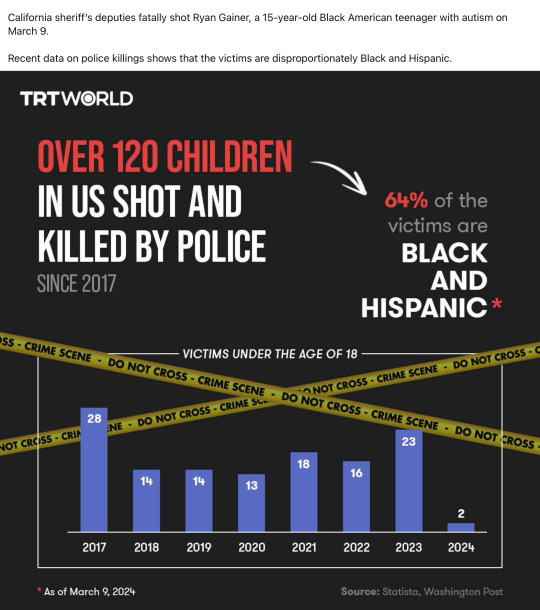

#Al- Jazeera English#TRT World 🌎#Sudan 🇸🇩 | South Sudan 🇸🇸 | Chad 🇹🇩#World’s Worst Hunger Crisis#Trapped in a Spiral 🌀#Civil War | Army | RSF Paramilitary#25 Million Displaced People 14 Million Children | Lifesaving Assistance#California Sheriff Deputies#15-Year-Old Black American | Autistic | Shot#Police Killing | Blacks & Hispanic | Disproportionately

0 notes

Text

Hundreds of families fled a northern suburb of Sudan's capital Khartoum on Saturday after fighting between the army and paramilitary forces intensified around a key military base.

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary on 4 September launched an attack on the Hattab base in Khartoum North, also known as Bahri, which had been under army control since the start of Sudan’s civil war in April 2023.

Artillery fire from the army targeted the southern area of the Hattab base while military aircraft flew overhead, a resident in the area told AFP.

RSF forces meanwhile attacked residential areas south of the base, killing and abducting civilians, the resident added, without specifying a number.

Hundreds of families fled on foot with their belongings towards the north.

The ongoing conflict between the army and the RSF has left tens of thousands dead and has displaced over 10 million people, with many seeking refuge in neighbouring countries, according to UN reports.

On Friday, UN experts called for the immediate deployment of an independent force to safeguard civilians amid the severe humanitarian crisis.

“Sudan's warring parties have committed an appalling range of harrowing human rights violations and international crimes, including many which may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity,” the UN's Independent International Fact-Finding Mission for Sudan said in its first report.

Those violations included indiscriminate air strikes and the shelling of schools, hospitals, communication networks and water and electricity supplies.

Both parties had targeted civilians in attacks, as well as through rape and other forms of sexual violence, arbitrary detention and torture.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

"SUDANESE MOTHER’S DESPAIR AFTER 9 MONTHS OF WAR"

"You can hear the hopelessness in the voice of Batoul, one of millions of displaced Sudanese as civil war rages in the Sahelian country. However, the mother says she still loves Sudan, and she hopes her children will have a better future than the reality to which she has resigned her generation."

"Wad Medani, where Batoul is currently located, emerged as a critical humanitarian hub in April, when fighting broke out between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). It hosts hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people escaping the conflict in the capital of Khartoum."

Now in its ninth month, the war has left half of Sudan’s 48 million people requiring aid. According to the United Nations, more than 7.3 million people have fled their homes. Sudan recently bypassed the Democratic Republic of the Congo to take the unfortunate distinction of having the biggest internal displacement crisis in the world."

"Meanwhile, hunger is rising. And, more than 13,000 people have been killed. Plus, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project reports a 56 per cent increase in explosions and remote violence in Khartoum in the weeks between 25 November and 5 January, compared to the six weeks prior. Young boys reportedly have been conscripted as child soldiers, while monitors on the ground say young girls have been forced into prostitution."

"Previous attempts to negotiate an end to fighting have failed. Most recently, Sudan’s government suspended ties with the East African regional bloc, Intergovernmental Authority on Development, because it invited RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as ‘Hemedti’) to a 18 January meeting in Uganda."

"As the two sides battle it out, innocent civilians like Batoul are sandwiched in the middle, paying the highest price."

#feminist#feminism#social justice#sudan#eyes on sudan#sudan crisis#sudan genocide#keep eyes on sudan#free sudan#khartoum#violence against women#human rights violations#sudanese#liberate sudan#rsf#genocide#human rights

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

"sudan has been at war for 200+ days. on april 15th 2023, conflict erupted between the sudanese army (SAF) and the rapid support forces (RSF) in khartoum. six months have passed, and there has been no ceasefire or any concrete plan to stop the violence. sudan is facing the world's worst displacement crisis with 7.1 million people driven out of their homes as a result of intense civil conflict. there is a genocide happening in darfur right now. "they want to ethnically cleanse us". more than 1,000 people have been killed this month in sudan's west darfur in an apparent "ethnic cleansing campaign" by the paramilitary rapid support forces. according to the united nations, 7 million sudanese have been displaced. 9000 have been killed. 4000+ are injured. 40/59 hospitals have been bombed. 19 million children are out of school. 10.4 k schools are shut down. 17.3 million lack access to clean water" — via antiracisteducation on instagram

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Children killed as bomb falls near Sudan hospital - MSF

Two children were killed and others were injured after a bomb fell near a paediatric hospital in the western Sudanese city of El Fasher, the medical charity MSF has said.

Clashes have recently intensified in the battle for control of the city.

It is the last major urban centre in the Darfur region that remains in the hands of the army.

It has been fighting the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) for more than a year, in a civil war that has killed thousands and forced millions from their homes.

The army has managed to hold on to El Fasher but tension has been mounting as the RSF has been besieging the city since the middle of last month and threatening an assault.

Since Friday, residents have witnessed intense clashes and the exchange of heavy mortar fire, a freelance journalist in the city told the BBC.

At some point overnight into Sunday a blast in front of the MSF-supported Babiker Nahar Paediatric Hospital in El Fasher "led to the collapse of the roof above the intensive care unit and the death of two children receiving treatment there, as well as some caregivers", the charity said in a brief statement sent to the BBC.

Patients were also injured and those who could make it sought safety in another hospital, which had already taken in 160 wounded people on Friday.

It is not clear who was responsible for the attack.

The southern part of the city, once considered safer and a refuge for displaced people, has been under fire.

Fear now pervades El Fasher as residents are unsure where to seek refuge.

The UN's humanitarian co-ordinator for Sudan said that "the violence threatens the lives of over 800,000 civilians".

"It is heartbreaking to see this nightmare unfolding... This must stop," Clementine Nkweta-Salami said.

Sudan’s brutal civil war began in April last year, after the country’s two leading military men who had staged a coup together – one the head of the armed forces, the other the head of the RSF – fell out over the future of the country.

International efforts to broker a ceasefire have repeatedly failed.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hajer Sulaiman, a 32-year-old communications specialist, was living in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, when a power struggle that had been simmering for months between the regular army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) burst into the open on 15 April last year.

“My mother was telling me she wanted to head to the market that morning,” Sulaiman said. “We could hear loud explosions, but we thought it was to do with protesters, not that the entire country had slipped into a civil war. It was just too overwhelming to process.”

She didn’t expect the fighting to last a long time, believing the country’s generals would be hauled around the table to thrash out a deal. But the sound of mortars, fighter jets and gunfire did not cease, and a few days later the family decided they had to leave.

Sulaiman, who now lives in Port Sudan, a small city on the Red Sea coast, is among millions of displaced Sudanese people whose lives have been upended by a brutal and seemingly intractable conflict that has killed at least 14,000 civilians, according to a conservative estimate by the nonprofit war monitor ACLED.

“I only took my laptop and phone because I thought we’d be back in a few weeks,” Sulaiman said. “That’s what hurts the most,” she added, “not being able to say goodbye and now it has been over a year.”

According to the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, there are about 10 million internally displaced people in Sudan, making it the country with “the largest internally displaced population ever reported”.

More than 7 million have been internally displaced since the war began, of whom about 4 million are children, according to Unicef. “Child displacement goes along with multiple other crises as a result of the war,” said Mandeep O’Brien, Unicef’s country representative for Sudan. “Children face disease, malnutrition and hunger and close to 8.9 million are acutely food insecure.”

continue reading

#sudan#sudan crisis#internally displaced people#record high#food insecurity#disease and malnutrition

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A genocide may have been committed in the West Darfur city of El Geneina in one of the worst atrocities of the year-long Sudanese civil war, according to a report released by Human Rights Watch (HRW).

It says ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity have been committed against ethnic Massalit and non-Arab communities in the city by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces and its Arab allies.

The report calls for sanctions against those responsible for the atrocities, including the RSF leader, Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemedti.

The UN says about 15,000 people are feared to have been killed in El Geneina last year.

Warning: This article contains details that some readers may find distressing

The HRW report documents evidence of a systematic campaign by the RSF and allied militias to remove Massalit residents from El Geneina.

Witnesses described how the RSF rounded up and shot men, women and children who attempted to escape the ethnic violence in the restive city.

At least "thousands of people" were killed and "hundreds of thousands" left as refugees between April and November 2023, the 218-page report said.

"The events are among the worst atrocities against civilians so far in the current conflict in Sudan," it added.

The US and the prosecutor for the International Criminal Court have talked about war crimes in Darfur but they have not specifically mentioned genocide.

The BBC has spoken to people from El Geneina who say they were victims of ethnic violence.

One man told us he had joined others who fled to a central gathering place after sites were attacked in different parts of the city. He said the RSF had a base nearby and eventually began bombing this area, Mudaris, with heavy guns.

“We buried all the dead people at night,” he said, “one day 186 people, another day 80, another day 50.”

The man, who asked not to be named, is now sheltering in neighbouring Chad.

He told the BBC that armed men raped his wife, using degrading language as they did so: “They said: 'Now we are your husband, your people have all have been killed. You can be the servants of our wives and clean our houses.'”

The HRW report says that RSF fighters and militias used derogatory racial slurs against Massalit and other racial groups, telling them that the land was not theirs and that that it would become "the land of the Arabs".

It says the attacks culminated in a large-scale massacre on 15 June last year, when the RSF and its allies opened fire on a convoy of civilians desperately trying to flee.

A 17-year-old boy described to HRW the killing of 12 children and 5 adults from several families: “Two RSF forces … grabb[ed] the children from their parents and, as the parents started screaming, two other RSF forces shot the parents, killing them. Then they piled up the children and shot them. They threw their bodies into the river and their belongings in after them.”

The current violence has erupted out of a long history of tensions over resources between non-Arab farming communities, including the Massalit, and Arab pastoralist communities.

Those tensions were harnessed by the former government of Omar al Bashir. It created Arab militias known as the Janjaweed to put down a Massalit rebellion in the 2000s, out of which the RSF was eventually formed. Many of the people who fled Janjaweed attacks 20 years ago found refuge in camps for internally displaced persons in El Geneina.

Sudan’s civil war has helped reignite the violence. It began as a power struggle between the leaders of the Sudanese army, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the paramilitary RSF, Gen Hemedti, but has since drawn in other ethnic militias.

Gen Hemedti has denied his fighters deliberately attacked civilians.

But HRW says he is among those with command responsibility over the forces which carried out the atrocities.

The HRW researchers interviewed more than 220 Sudanese refugees in Chad, Uganda, Kenya, and South Sudan, as well as remotely between June 2023 and April 2024.

They also reviewed and analysed over 120 photos and videos of the events, satellite imagery, and documents shared by humanitarian organisations to corroborate accounts of the abuses.

The rights body called for further investigations to find out if there was an intention to eliminate the Massalit community, which would indicate a genocide.

Last June, West Darfur Governor Khamis Abakar was killed hours after accusing RSF of committing genocide. He is the most senior official known to have been killed since the conflict began in April.

The RSF says it is not involved in what it describes as a "tribal conflict" in Darfur.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"She said many civilians were targeted based on their ethnicity in Sudan's besieged city of El Fasher, where fierce fighting has intensified in recent days.

More than 700 casualties have been reported in 10 days by a medical charity in the city.

El Fasher is the last major urban centre in the Darfur region that remains in the hands of Sudan's army.

The military has been fighting the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) for more than a year, in a civil war that has killed thousands and forced millions from their homes.

...

Similar fears of a possible genocide in Darfur were expressed by Human Rights Watch (HRW) recently.

A report from the campaign group said ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity had been committed against ethnic Massalit and non-Arab communities in the region by the paramilitary forces and its Arab allies.

It called for sanctions against those responsible for the atrocities, including the RSF leader, Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemedti.

The current violence has erupted out of a long history of tensions over resources between non-Arab farming communities, including the Massalit, and Arab pastoralist communities.

The internet has been cut making access to the city difficult, as soldiers from the RSF group continue to besiege the city.

The UN says about 15,000 people are feared to have been killed in the West Darfur city of El Geneina last year."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In late October 2021, a top U.S. envoy met with Sudanese military commanders and Sudan’s top civilian leader to shore up the country’s precarious transition toward democracy. The generals assured Jeffrey Feltman, then the U.S. special envoy for the Horn of Africa region, that they were committed to the transition and would not seize power. Feltman departed the Sudanese capital of Khartoum for Washington early on the morning of Oct. 25. En route, he received news from Sudan: Hours after he left, those military leaders had arrested the country’s top civilian leaders and carried out a coup.

For the next 18 months, Washington adopted a series of controversial policy measures to both maintain ties with the new military junta and try to push the East African nation back toward a democratic transition. Months of work led to a new political deal that offered, on paper at least, new hope, and some Biden administration officials felt they were tantalizingly close.

But the deal blew up in the eleventh hour as violence erupted across Khartoum last month between forces controlled by the rival generals, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who leads the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and Mohamed Hamdan “Hemeti” Dagalo, the head of the powerful Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group.

The collapse of Sudan’s democratic transition has led to anger and backlash in Washington among diplomats and aid officials, some of whom feel that the Biden administration’s policies empowered the two generals at the center of the crisis, exacerbated tensions between them as they pushed for a political deal, and shunted aside pro-democracy activists in the process.

“Maybe we couldn’t have prevented a conflict,” said one U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But it’s like we didn’t even try and beyond that just emboldened Hemeti and Burhan by making repeated empty threats and never following through.”

“And all the while,” the official added, “we let the real pro-democracy players just be cast to the side.”

The conflict between Burhan’s and Hemeti’s forces turned Khartoum overnight into a battle zone that put millions of citizens, as well as U.S. and foreign government personnel, in the crossfire of firefights, airstrikes, and mortar attacks. The fighting has pushed Sudan toward the brink of collapse and undermined, perhaps permanently, a Western-funded project to bring democracy to a country beset by autocracy and conflict for half a century.

People run and walk through the streets in front of an armored personnel carrier as fighting in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum continues between Sudan’s army and paramilitary forces on April 27. AFP via Getty Images

As successive rounds of cease-fires fail, Western officials and analysts increasingly fear that the fighting could lead to a full-scale civil war, bringing a new vacuum of instability and chaos to a region already suffering humanitarian crises and along the strategic Red Sea, through which 10 percent of global trade flows.

“The way things are going, Sudan begins to resemble a massive Somalia of the early 1990s on the Red Sea, a total state breakdown, if the fighting doesn’t stop,” said Alexander Rondos, a former European Union envoy for the Horn of Africa.

Interviews with about two dozen current and former Western officials and Sudanese activists close to the negotiations describe a deeply flawed U.S. policy process on brokering talks in Sudan in the run-up to the conflict, monopolized by a select few officials who shut the rest of the interagency team out of key deliberations and stamped out a growing chorus of dissent over the direction of U.S. Sudan policy.

“From the outset, there was a consistent and willful dismissal of views that questioned whether the U.N. talks would be a recipe for success or for failure,” said one former official familiar with the matter. “Those warnings were ignored, and instead the U.S. built a dream palace of a political process that has now crashed down on the people of Sudan.”

Current and former U.S. officials, many of whom spoke on condition of anonymity, said internal warnings of roiling tensions in Khartoum and a possible conflict were dismissed or ignored in Washington, setting the stage for U.S. government personnel to be trapped amid the fighting in various parts of Khartoum with no advance preparations to move them to safety. In Khartoum, these officials and Sudanese analysts said, the policy was further hampered by an embassy that was for years understaffed and out of its depth, without even an ambassador for much of the crucial period.

A woman inside her house protects her face from tear gas in the Abbasiya neighborhood of Omdurman, Sudan, on Nov. 13, 2021. Organizations called for civil disobedience and a general strike during demonstrations against the military coup. Abdulmonam Eassa/Getty Images

“We seemed to have lost all institutional memory on Sudan,” said Cameron Hudson, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and former State Department official. “These generals have been lying to us for decades. Anybody who has worked on Sudan has seen this stuff play out time and time and time again.”

The U.S. State Department has sharply disputed these characterizations. “U.S. engagement after the October 2021 military takeover was centered on supporting Sudanese civilian actors in a Sudanese-led process to re-establish a civilian-led transitional government,” a State Department spokesperson said in response.

“The United States did not press for any specific deal but tried to build consensus and put pressure on the key actors to reach agreement on a civilian government to restore a democratic transition,” the spokesperson said and added that those efforts included “near constant diplomacy, often working closely with civilians, to defuse tensions between the SAF and RSF that arose multiple times and again emerged in the days before April 15, 2023,” when the fighting began.

Still, for an administration that has made promoting global democracy a centerpiece of its foreign policy, many government officials who spoke to Foreign Policy contended that Sudan could stand as one of the starkest foreign-policy failures, even in the wake of the successful evacuation of all U.S. government personnel and campaign to help U.S. citizens escape the country.

These officials also fear that the crisis could reverberate well beyond Sudan’s borders if the warring sides don’t agree to a viable cease-fire soon, with the risk of rival foreign powers exacerbating the conflict and transforming it into a proxy war.

Interviews with multiple Sudanese activists and civil society leaders, meanwhile, paint the picture of a pro-democracy movement that has completely lost faith in the United States as a beacon for democracy and supporter of Sudan’s own democratic aspirations. Many spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of their safety as fighting continued in Khartoum.

“Either the U.S. and West properly step up or they just need to fuck off because halfhearted steps and empty threats of sanctions, again and again and again, are doing more harm than good,” said one Sudanese person deeply familiar with the internal negotiations. “Our trust in the U.S. is entirely gone.”

Sudanese protesters cheer on arriving to the town of Atbara from Khartoum on Dec. 19, 2019, to celebrate the first anniversary of the uprising that toppled Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir. Ashraf Shazly/AFP via Getty Images

After a popular pro-democracy uprising ousted longtime dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019 and set the stage for Sudan to rejoin the international community after decades as an international pariah, the United States invested countless diplomatic resources and hundreds of millions of dollars in Sudan’s democratic transition.

Sudan seemed poised to be a success story. A popular uprising, led in many ways by Sudanese women, had ousted one of the world’s most notorious dictators. U.S. President Joe Biden in a major U.N. speech in September 2021 denounced the global rise of autocracy and touted Sudan as one of the most compelling contrasts to that trend worldwide after the 2019 revolution. In Sudan, he said, there was proof that “the democratic world is everywhere.”

Just a month later, Burhan and Hemeti orchestrated their coup. Afterward, the Biden administration froze some $700 million in U.S. funds to aid in the democratic transition and, over a year later, issued visa restrictions on “any current or former Sudanese officials or other individuals believed to be responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the democratic transition in Sudan.” The World Bank and International Monetary Fund also froze $6 billion in financial assistance.

But some U.S. diplomats felt that didn’t go far enough and none of those reprisals would directly affect Burhan or Hemeti. A fierce internal debate unfolded. Some officials argued that Washington needed to roll out punishing sanctions against Burhan and Hemeti to bring them to heel and show support for pro-democracy activists. Other officials, including Assistant Secretary of State Molly Phee—Biden’s top envoy for Africa—argued that sanctions wouldn’t be effective and might undermine U.S. influence with Burhan and Hemeti as they sought to bring them back to the negotiating table.

“There was the right thing to do, to show the Sudanese people we were all-in on democracy, to punish Hemeti and Burhan for this blatant coup, and then there was the wrong and slightly more expedient thing to do, [to] just keep working with them after some stern finger-wagging,” said one U.S. official involved in the process. “We chose door number two.”

Jeffrey Feltman, the U.S. special envoy for the Horn of Africa, leaves after meeting with Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok in Khartoum on Sept. 29, 2021. Ashraf Shazly/AFP via Getty Images

Feltman, the former U.S. envoy, said he advocated for sanctioning Burhan and Hemeti during his time in government but in hindsight wasn’t sure if it could have prevented the conflict. “Do I think sanctions ultimately would have prevented them from eventually taking 46 million people of Sudan hostage because of their personal lusts for power? No.”

There were other complicating issues as well. Senior Biden administration officials working on Africa policy were consumed by the war in neighboring Ethiopia, where an estimated 200,000 to 600,000 people died during a bloody conflict in the country’s northern Tigray region. And the U.S. Embassy in Khartoum was understaffed and unable to come to grips with the situation; a full-time U.S. ambassador wouldn’t arrive until three years after Bashir’s ouster. During this time, officials say, Phee took direct charge over U.S. policy on Sudan.

Phee worked closely with a U.S. Agency for International Development official detailed to the State Department, Danny Fullerton, in Khartoum to negotiate directly with Burhan and Hemeti and bring them to the table for a new political deal.

“The embassy was just very beleaguered, with a real shortage of skilled or enough political officers, and both the chargés d’affaires and later the ambassador when he got there were very frustrated with a lack of support from Washington,” said one American familiar with internal embassy dynamics. “It was a group that was out of its depth, overly busy, and, frankly, not as well connected as it should’ve been with the right people in Sudan’s pro-democracy communities.”

This official said severe embassy staffing shortages, detailed in a State Department watchdog report on the embassy published in March, and leadership issues contributed to difficulties in hashing out negotiations with Burhan and Hemeti. But other current and former officials dispute that, insisting that the State Department can still make deals with high-level involvement from officials in Washington, even with an understaffed embassy.

Five current and former U.S. officials and two Sudanese activists familiar with the negotiations said that before the U.S. ambassador came to Khartoum in late 2022, U.S. officials involved in the negotiations with Hemeti and Burhan didn’t do enough to incorporate Sudan’s pro-democracy resistance committees into deliberations on a new political deal with the two generals, nor did they heed warnings about the inherent risks and flaws in a new deal.

A Sudanese woman chants slogans and waves a national flag during a demonstration demanding a civilian body to lead the transition to democracy outside the army headquarters in Khartoum on April 12, 2019. Ashraf Shazly/AFP via Getty Images

These officials said there was mounting dissent in Washington over the trajectory of U.S. policy but that Phee dismissed other policy options, including threatening Hemeti or Burhan with sanctions or other forms of pressure or incorporating Sudan’s pro-democracy groups into the political negotiations. The State Department watchdog report also noted that the deputy chief of mission in Khartoum “at times remained focused on her predetermined course of action and did not consider alternatives offered by staff”—though the report did not address whether this had any affect on U.S. policy.

The State Department spokesperson, however, sharply disputed these characterizations: “While we cannot comment on internal policy deliberations, State Department leaders carefully considered policy proposals and different opinions on our policy on Sudan and did not dismiss or stamp out any dissent.”

All the while, Burhan and Hemeti sought to expand their own power and influence across Sudan, currying favor with foreign powers and setting the stage for a growing rivalry that would later ignite a deadly conflict. Burhan found backers in neighboring Egypt. Hemeti courted the United Arab Emirates and Russia and began deepening ties between the RSF and the Wagner Group, a shadowy Russian mercenary outfit widely reported to be responsible for war crimes in other parts of Africa and in Ukraine. Hemeti, implicated in widespread atrocities in Sudan’s Darfur conflict that broke out in 2003, launched a coordinated public relations campaign to try to transform himself into a statesman on the world stage in what was seen as a political charm offensive and challenge to Burhan’s rule.

Hemeti visited Moscow on Feb. 23, 2022, on the eve of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, to discuss the possible opening of a Russian port on Sudan’s coast along the strategic trade routes in the Red Sea. Some U.S. officials who had been pushing for sanctioning Hemeti believed his brazen visit to Moscow would finally convince top decision-makers to finally pull the trigger on a major new tranche of sanctions. The sanctions never came.

Around that time, at least one memo was written and circulated within the State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs warning of the risks of current U.S. policy on Sudan and listing potential scenarios that could emerge from the rivalry between Burhan and Hemeti, including those tensions erupting into a full-scale conflict. The memo, described in broad terms by several congressional aides and former officials familiar with it, was meant to go to U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s desk, but the draft was heavily edited, watered down, and never passed out of the bureau, those people said. “Still, the State Department leaders can’t say they weren’t warned,” one former official said.

Human rights advocates have also criticized the Biden administration’s approach to Sudan in the months leading up to the eruption of violence in April. “By repeatedly failing to hold abusive leaders accountable or making clear, through concrete measures, that abusive behavior would not be condoned, Sudan’s Western partners sent these generals the signal that they can continue holding the country at a gunpoint with almost no consequences,” said Mohamed Osman, an expert on the region at Human Rights Watch.

During this time, Sudanese activists became increasingly disenchanted with the U.S. approach to Sudan. “There was no meaningful commitment that we’d ever seen from either [Burhan or Hemeti], and that was all put aside and sacrificed effectively at the altar of a political process and a political agreement that was never going to hold and that had very little popular support,” said Kholood Khair, a Sudanese political analyst who followed the negotiations closely.

John Godfrey, the U.S. ambassador to Sudan, delivers a speech in Port Sudan amid the delivery of tons of corn as part of U.S. humanitarian support for the country on Nov. 20, 2022. AFP via Getty Images

In September 2022, John Godfrey, a career U.S. diplomat with experience in the Middle East and North Africa and a background in counterterrorism, landed in Khartoum as the first U.S. ambassador to Sudan in a quarter century. Godfrey, officials said, immediately began trying to make inroads with so-called resistance committees and other civil society organizations that had been the driving force in Sudan’s push for democracy.

“He was beset with the cards that were dealt to him,” the American familiar with the embassy’s internal dynamics said. “He was burning the candle at both ends trying to make this deal happen, even if people back in Washington, outside of Phee and the [Bureau of African Affairs], weren’t giving Sudan much attention or thought.”

Even as Russia’s war in Ukraine and the ongoing conflict in Ethiopia distracted most in Washington, Phee and Godfrey—alongside counterparts including senior diplomats from the United Kingdom, United Nations, African Union, and a regional bloc called the Intergovernmental Authority on Development—pushed to restart Sudan’s transition to civilian rule. An apparent breakthrough came last December, when Sudan’s military leaders and some factions of the country’s pro-democracy forces agreed to a new civilian-led transitional government in a matter of months.

But the Western negotiators acceded to demands by Hemeti and Burhan to cut civil society and pro-democracy activists out of the negotiations, giving the military junta an early win over the weaker civilian groups, officials said. The December agreement also left unresolved one major issue that would soon become an explosive one: plans to incorporate the RSF into the SAF to create one unified military force for the country.

People gather to protest the framework agreement signed by Sudan’s military and civilian leaders, which aims to resolve the country’s governance crisis, in Khartoum on April 6. Mahmoud Hjaj/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

That question fueled more tensions between Burhan and Hemeti in the coming months. Analysts in Khartoum began sounding alarm bells about the roiling tensions that would set the stage for an eruption of violence. The push for the agreement may have exacerbated it.

“There was this absolute desperation to push the final deal over the line to the point of succumbing false hope,” said another person involved in the negotiations.

In Washington, however, plans were underway to celebrate the new transitional government the second the agreement was signed. The embassy continued arranging meetings with Hemeti and Burhan and conducting routine embassy business; an American rock band played a festival in March as part of a State Department public diplomacy tour.

The business-as-usual approach belied the tensions in Khartoum. A signing ceremony for the deal was delayed and then delayed again. Burhan and Hemeti were amassing forces around Khartoum. Some low-level U.S. diplomats and Sudanese civilian negotiators began more explicitly warning their friends and colleagues back in Washington through informal back channels that a conflict seemed imminent.

“People were calling around, saying, ‘You’ve got to pass up these messages to everyone you know in D.C. that there could really be a war, it doesn’t feel like the international community is taking us seriously’” said the American familiar with internal embassy dynamics.

Activists demonstrate in front of the White House in Washington on April 29, calling on the United States to intervene to stop the fighting in Sudan. Daniel Slim/AFP via Getty Images

Top officials in Washington either downplayed or misinterpreted these warning signs, according to six officials and congressional aides familiar with the matter. It wasn’t the first time that Burhan and Hemeti had amassed forces around Khartoum, nor the first time that U.S. interlocutors had to step in to help calm the tensions.

Godfrey and his counterpart from London, Giles Lever, who played key roles in shepherding the December deal to the finish line, left the country on separate vacations by early April, a sign that Washington felt the deal was all but done. Back in Washington, after Burhan and Hemeti signed the agreement, the State Department sent word to Congress that it wanted to ready $330 million in funds to aid Sudan’s democratic transition, according to three congressional aides and officials familiar with the matter. Those officials said the department was drafting a carrot-and-stick plan for Sudan, with the millions of dollars of funding the carrot and new sanctions authorizations a hefty stick.

The State Department had a long-standing Level 4 travel advisory for Sudan, recommending that U.S. citizens “do not travel” there, and sent out one additional security alert, on April 13, advising citizens to avoid Karima in northern Sudan, and barring U.S. government personnel from leaving Khartoum, in light of the “increased presence of security forces.” The United States didn’t issue a broad travel warning urging citizens to leave via commercial air travel, consolidate U.S. government personnel inside Khartoum in the event of a crisis, or order a departure of nonessential personnel as tensions between Burhan and Hemeti reached a boiling point.

“We’re all really questioning why we didn’t do more to prepare for the worst-case scenario,” a third U.S. official said.

Drone footage shows clouds of black smoke over Bahri, also known as Khartoum North, outside Sudan’s capital, in a May 1 video obtained by Reuters.Third-party video via Reuters

On April 15, the tensions between Hemeti and Burhan finally boiled over. The RSF launched what appeared to be a coordinated series of attacks on SAF bases and hammered Khartoum International Airport with gunfire and missiles—effectively cutting off the only viable means of escape in a densely populated city that is hundreds of miles from the coast or nearest border.

At once, the city of some 5 million people became a battle zone. The U.S. Embassy began working frantically to consolidate all its personnel and their families in several key locations. Godfrey, the U.S. ambassador, had rushed back to Khartoum, cutting his vacation short, just before the fighting erupted. RSF fighters carried out wholesale looting and assaults, and SAF troops began bombing sites around Khartoum. RSF fighters assaulted the EU’s ambassador in Khartoum, Aidan O’Hara, and in various other instances reportedly fired on, briefly kidnapped, or sexually assaulted U.N. and international organization workers, according to internal U.N. security reports obtained by Foreign Policy.

The White House, State Department, and Defense Department leaped into crisis mode, working around the clock to draft up embassy evacuation plans. On April 22, a contingent of U.S. troops took off from a U.S. base in Djibouti on three Chinook helicopters and, after refueling in Ethiopia, landed in Khartoum to safely evacuate all U.S. government staff and their families. All the while, top U.S. diplomats worked to arrange temporary cease-fires between Burhan and Hemeti to aid civilians and assist those trying to escape.

“None of the foreign diplomatic missions in Khartoum changed their security posture or staffing levels before the outbreak in fighting, and the U.S. embassy was very focused and effective in consolidating its personnel immediately after the war started,” the State Department spokesperson said.

An estimated 16,000 U.S. citizens remained trapped in the city, including many dual U.S.-Sudanese citizens and a smaller number of NGO and aid workers who worked on U.S.-funded humanitarian and development programs. U.S. lawmakers became infuriated that the Biden administration wasn’t doing more to aid in the evacuation of U.S. citizens after the initial outbreak of the conflict, comparing the fiasco to the ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan.

The Saudi-flagged ferry passenger ship Amanah carrying evacuated civilians fleeing violence in Sudan arrives at King Faisal Naval Base in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on April 26. Amer Hilabi/AFP via Getty Images

One resident who stayed in Khartoum was Bushra Ibnauf, a dual U.S.-Sudanese citizen and doctor who had moved back to Khartoum from Iowa. “He had a passion for doing good. I remember him saying, ‘I can be replaced in Iowa, but I can’t be replaced in Sudan,’” said Yasir Elamin, the president of the Sudanese American Physicians Association and a close friend and colleague of Ibnauf. Ibnauf and other doctors ventured out amid gunfights and explosions to provide aid to wounded civilians as the conflict dragged on.

Other Sudanese citizens began trying to make their way out of Khartoum, either by fleeing north to the Egyptian border or on a precarious overland journey to the coast at Port Sudan. “It was hell on earth,” recalled one Sudanese activist who escaped Khartoum. “We only left through the city and all the firefights because we were running out of water. Our choice was either definitely die of thirst or maybe get hit by bullets. It was no choice at all.”

U.S. officials have made brokering a sustainable cease-fire their top priority, but so far no cease-fire has held. Both Burhan and Hemeti have sent negotiators to peace talks in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, coordinated with Washington and Riyadh, but many officials and analysts doubt the talks will lead anywhere after multiple ceasefire attempts failed. On May 4, Biden announced a new executive order granting new legal authorities to impose sanctions on those involved in the violence in Sudan. Some Sudanese analysts doubt sanctions will work.

“The point of sanctions is that it is used as a threat during normal times to prevent bad actors from doing bad things,” said Amgad Fareid Eltayeb, a former assistant chief of staff to Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok before he was ousted from power. “I think right now it’s too little, too late—it’s already a war situation.”

The situation in Khartoum remains dire. “I don’t think so-called safe areas right now are going to be safe for much longer because the aim of the game from both sides seems to be total control of the country,” said Khair, the Sudanese political analyst.

A Sudanese person paints graffiti on a wall during a demonstration in Khartoum on April 14, 2019. Omer Erdem/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

U.S. lawmakers are pressing for new envoys to enter the fray. Rep. Michael McCaul, the Republican chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and his Democratic counterpart, Rep. Gregory Meeks, issued a joint appeal to Biden and the U.N. to appoint new U.S. and U.N. special envoys to Sudan, saying that “[d]irect, sustained, high-level leadership from the United States and United Nations is necessary to stop the fighting from dragging the country into a full-blown civil war and state collapse.”

Many Western officials fear that Sudan could plunge into civil war if the fighting isn’t stopped soon, but it’s also unclear what a viable cease-fire would mean for any hopes of reviving the moribund democratic transition in Sudan. “This is not yet a full-scale civil war, à la Syria, à la Libya,” said Feltman, the former U.S. envoy. “It’s still a fight between two rival forces. Now is the time to arrest it, to stop it before it spirals.”

All the while, the fighting in Khartoum continues. Some U.S. citizens have found additional ways to evacuate, either with the direct assistance of the U.S. government or of other countries.

Others weren’t so lucky. Ibnauf, the Sudanese American doctor who stayed in Khartoum to provide succor to civilians amid the fighting, was stabbed to death by suspected looters in front of his family on April 25.

#Sudan#east africa#khartoum#us fighting#colonialism 2023#emergency evacuations#Sudan Crisis: U.S. Missteps Fumbled Hopes for Democracy#failed us policy#Africa

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sudan paramilitaries shell besieged Darfur city, killing 23: activists

New Post has been published on https://sa7ab.info/2024/08/06/sudan-paramilitaries-shell-besieged-darfur-city-killing-23-activists/

Sudan paramilitaries shell besieged Darfur city, killing 23: activists

Shelling by Sudanese paramilitaries killed at least 23 people on Saturday in the besieged Darfur city of El-Fasher, activists said.

The capital of North Darfur state is the largest city in the vast western region not yet under the control of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), who have been battling the regular army for more than a year and have laid siege to El-Fasher since May.

The El-Fasher Resistance Committee said in a statement published on its Facebook page that “deliberate bombing” by the paramilitary forces resulted in “23 martyrs”, all civilians, and 60 wounded.

RSF shelling of El-Fasher last week killed at least 65 people, said the committee, one of hundreds across Sudan that used to organise pro-democracy protests and have coordinated frontline aid since the war began in April last year.

Medical charity Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has said that by late June, at least 260 people had been killed in the fighting in El-Fasher.

The war, which pits the RSF, led by Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, against the army headed by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, has killed tens of thousands of people with some estimates as high as 150,000, according to United States envoy Tom Perriello.

The United Nations says Sudan faces the world’s largest internal displacement crisis, with more than 10 million forced to flee internally or abroad.

The conflict has ravaged the country’s infrastructure, put more than three-quarters of health facilities out of service and sparked warnings of famine.

A UN-backed assessment published Thursday found that “famine is ongoing” in Zamzam, a displacement camp outside El-Fasher that hosts hundreds of thousands of people.

UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, urged international donors to step up support for Sudan, where civil war has raged since April 2023 and left tens of thousands dead according to the UN.

“The warning signs were there for months,” said Mamadou Dian Balde, UNHCR’s regional refugee coordinator for the Sudan situation.

“Displaced women, children and men are dying of hunger, malnutrition and disease,” he said.

“With appalling human rights atrocities, the forced displacement of over 10 million people since the start of the war last year, and the lack of the most basic services for a large percentage of the population, the world’s most pressing humanitarian catastrophe is growing and deepening every day, threatening to engulf the whole region.”

Balde is also UNHCR’s East and Horn of Africa and Great Lakes regional director.

He said the volume of refugees and internally displaced people was stretching host communities to a breaking point.

“Urgent action is vital to avert even more death and suffering.”

Both sides have been accused of war crimes including deliberately targeting civilians.

0 notes

Text

Sudan’s Army Faces Scrutiny After Major City Falls to Rival Forces

The capture by paramilitary forces of Wad Madani, a strategic city in the country’s agricultural region, marks a watershed in the civil war that has upended life in the northeast African nation.

source https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/20/world/africa/sudan-army-rsf-wad-madani.html

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Sudan civil war: Darfur's Jem rebels join army fight against RSF

A rebel leader tells the BBC his forces will fight a paramilitary group accused of ethnic cleansing.

from BBC News – World https://ift.tt/oZzq4NJ

via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

‘Corpses on streets’: Sudan’s RSF kills 1,300 in Darfur, monitors say

Al Jazeera

By mat Nashed

November 10, 2023

Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) besieged a camp for displaced people on November 2 after attacking a nearby army base in West Darfur. Over the next three days, the paramilitary group committed what may amount to the single largest mass killing since the civil war erupted in April.

Local monitors told Al Jazeera that about 1,300 people were killed,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

KHARTOUM, May 2 (Reuters) - Sudan's warring military factions agreed to a new and longer seven-day ceasefire from Thursday, neighbour and mediator South Sudan said, even as more air strikes and shooting in the Khartoum capital region undercut their latest supposed truce.

Previous ceasefire pledges have ranged from 24 to 72 hours but there have been constant truce violations in the conflict that erupted in mid-April between the army and a paramilitary force.

South Sudan's foreign ministry said in a statement on Tuesday that mediation championed by its president, Salva Kiir, had led both sides to agree a weeklong truce from Thursday to May 11 and to name envoys for peace talks. The current ceasefire was due to expire on Wednesday.

It was unclear, however, how army chief General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and paramilitary Rapid Support forces (RSF) leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo would proceed.

On Tuesday, witnesses reported more air strikes in the cities of Omdurman and in Bahri, both on the opposite bank of the Nile River from Khartoum.

Al Jazeera television said Sudanese army warplanes were targeting RSF positions, and anti-aircraft fire could be heard from Khartoum.

India's embassy in Khartoum was stormed and looted, Sudan's army said in a statement, citing a report from the ambassador. Saudi Arabia's foreign ministry said early on Wednesday that the building in Khartoum that houses its cultural mission was similarly vandalised and looted by an armed group. No casualties were reported.

Army jets have been bombing RSF units dug into residential districts of the capital region. Conflict has also spread to Sudan's western Darfur region where the RSF emerged from tribal militias that fought alongside government forces to crush rebels in a brutal civil war dating back 20 years.

The commanders of the army and RSF, who had shared power as part of an internationally backed transition towards free elections and civilian government, have shown no sign of backing down, yet neither seems able to secure a quick victory.

REGION AT RISK

Prolonged conflict could draw in outside powers.

Fighting now in its third week has engulfed Khartoum - one of Africa's largest cities - and killed hundreds of people. Sudan's Health Ministry reported on Tuesday that 550 people have died and 4,926 injured.

Foreign governments were winding down evacuation operations that sent thousands of their citizens home. Britain said its last flight would depart Port Sudan on the Red Sea on Wednesday and urged any remaining Britons wanting to leave to make their way there.

The conflict has also created a humanitarian crisis, with around 100,000 people forced to flee with little food or water to neighbouring countries, the United Nations said.

Aid deliveries have been held up in a nation where about one-third of people already relied on humanitarian assistance. A broader disaster could be in the making as Sudan's impoverished neighbours grapple with a refugee influx.

"The entire region could be affected," Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi said in a Japanese newspaper interview on Tuesday as a Burhan envoy met Egyptian officials in Cairo.

The U.N. World Food Programme said on Monday it was resuming work in the safer parts of Sudan after a pause earlier in the conflict, in which some of its staff were killed.

'THE SITUATION IS A CALAMITY'

Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) said it had delivered some aid to the capital from Port Sudan, a road journey of about 800 km (500 miles).

Some 330,000 Sudanese have also been displaced inside Sudan's borders by the war, the U.N. migration agency said.

"The situation is a calamity," Hassan Mohamed Ali, a 55-year-old state employee, said during a stopover in Atbara, 350 km (220 miles) northeast of Khartoum, en route to the Egyptian frontier.

"We suffer from power and water cuts, our children have stopped school. What's happening in Khartoum is hell."

Displaced Sudanese families have also made their way, sometimes on foot under scorching desert sun, hundreds of kilometres (miles) to Chad and South Sudan.

About 800,000 people could eventually leave, according to the U.N.

More than 40,000 people have crossed the border into Egypt over the past two weeks but only after days of delays. Most migrants have had to pay hundreds of dollars to make the 1,000-km (620-mile) journey north from Khartoum.

It took Aisha Ibrahim Dawood and her relatives five days in a rented car to get from Khartoum to the northern town of Wadi Halfa, where the women and children crammed into a back of a truck that brought them to a queue at the Egyptian border.

"Our suffering is unprecedented," she said.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sudan former PM warns of civil war that would be ‘nightmare for the world’

Abdalla Hamdok, who resigned in January last year, says conflict could spiral into bigger crisis than Syria, Yemen or Libya

Sudan’s former prime minister Abdalla Hamdok has warned that the conflict in the turbulent African nation could deteriorate to one of the world’s worst civil wars if it is not stopped early.

More than 500 people have been killed since battles erupted on 15 April between the forces of army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his number two Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, commonly known as Hemedti, who commands the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Continue reading... https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/30/sudan-former-pm-warns-of-civil-war-that-would-be-nightmare-for-the-world?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

‘Can’t trust the Janjaweed’: Sudan’s capital ravaged by RSF rule

After nine months of war, Khartoum under RSF control has turned into a lawless and violent capital.

Nine months of civil war between the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese army have turned Sudan’s capital Khartoum into a plundered, lawless and bloodied shell of its historic self, according to current and former residents.

For months now, the RSF has controlled most of the city, looting markets, homes, warehouses and vehicles. It has also set up hundreds of checkpoints and contributed to reducing entire neighbourhoods to rubble by embedding its fighters in residential areas, which are then indiscriminately shelled and bombed by the army.

“[The checkpoints] have led to a general state of fear and most people are afraid to leave their houses. There’s also a curfew that starts right after sunset,” said Mabrooka Fatma*, a Sudanese activist in the city.

In the weeks after a bitter political dispute between the RSF and the army erupted into war in April 2023, hundreds of thousands of people fled the capital to nearby cities under the latter’s control, but not everybody followed. Some were too poor to leave, while others feared that the RSF would confiscate and loot their homes if they fled. Dozens of activists also stayed behind to help communities affected by the war.

Most people later deemed it too dangerous to leave, even if they wanted to.

21 notes

·

View notes