#David Benatar

Text

nobody is lucky enough not to be born, everybody is unlucky enough to have been born. (David benatar)

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

"But those who lay all (or almost all) of the blame for the ongoing conflict and the consequent statelessness of the Palestinians on Israel display either bad faith or naiveté. Lifting the blockade on Gaza and unilaterally withdrawing from the West Bank would amount to suicide for Israel’s Jews. The same is true of the suggestion that there could be a unified state of Jewish and Arab citizens from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. Those who propose such a state need to explain which country in the region this state would most resemble. Not a single state in the Middle East rates even remotely as well as Israel still does in terms of liberal and democratic freedoms. What reason do we have for thinking that a unified Palestine would be any different, especially with antisemitic rejectionists like Hamas in the polity."

#david benatar#ethics#israel#gaza#palestine#postcolonialism#hamas#a rare voice of reason in academia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In this blog post, I examine the anti-natalist theory of the Norwegian existentialist philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe (1899–1990). According to Zapffe, human nature is riddled with an inherent, irresolvable conflict, the result of which is that human lives are filled with too much suffering for procreation to be morally permissible. In contrast to the God of the Old Testament, who instructs us to “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth,” Zapffe instructs us, in his 1933 essay “The Last Messiah,” to “be infertile and let the earth be silent after ye.”

According to Peter Wessel Zapffe, human life is inescapably very bad, the central reason for which is that there is an irresolvable conflict inherent in our nature. What does this conflict consist of? On the one hand, Zapffe explains, we humans are biological beings that, due to the evolutionary forces that have shaped us, are constantly prompted to act in ways that promote our own survival and reproduction. Having become the dominant species on Earth, we have, in evolutionary terms, been successful. One of the central explanations of our success, Zapffe suggests, is our advanced cognitive capacities. While cheetahs gain an evolutionary advantage by being fast and bears by being strong, we humans gain an advantage by being smart: The human intellect enables us, among other things, to make tools and traps, to cook, to plan, to communicate effectively, and to adapt quickly to changing environments.

Zapffe suggests, however, that the human intellect comes with a very significant downside: It confronts us with our frailty, with the suffering and death that eventually awaits us, with the vastness of suffering on Earth, and with our own cosmic insignificance—and these insights, he writes, are apt to fill us with “world-angst and life-dread.” While “in the beast, suffering is self-confined, in man, it knocks holes into a fear of the world and a despair of life.” One reason for fear and despair is that we humans grasp not just what is right before us; due to our “creative imagination” and “inquisitive thought,” “graveyards wrung themselves before [our] gaze, the laments of sunken millennia wailed against [us] from the ghastly decaying shapes.” Another reason is that, as beings with an intellectual nature, we crave justification, and thus we are uniquely confronted with, and pained by, the meaninglessness and injustice of suffering. This, Zapffe holds, is a secular truth behind the myth that we humans have “eaten from the Tree of Knowledge and been expelled from Paradise.”

(…)

Zapffe concedes that his bleak outlook on life is likely to strike many as counterintuitive. This is so, he suggests, not because life is in fact tolerably good, but because we have developed elaborate strategies to prevent ourselves from seeing the horrors of life. He argues that such strategies, which he calls strategies of suppression, “proceed practically without interruption as long as we are awake and in action, and provide a background for social cohesion and what is popularly called a healthy and normal way of life.”

Echoing ideas from early psychoanalytic theory, Zapffe lists three central strategies of suppression: Isolation, anchoring, and distraction. Isolation is the process of isolating ourselves from unpleasant impressions by institutionalizing taboos and by ostracizing those who break them. This is most evident, he suggests, in how we protect children from the harsh realities of life: We tell them that, in the end, all will be fine and good, even though we know that, in the end, we will suffer and die, and, eventually, be forgotten. Anchoring is the process of entertaining fictions that tell us that we belong in a certain stable place, such as a family, a home, a church, a state, or a nation. “With the help of fictitious attitudes,” Zapffe writes, “humans are able to behave as if the outer or inner situation were different from what honest cognition tells us.” Finally, distraction is the process of filling our waking hours with tasks that distract us from existential dread. We keep our “attention within the critical limit by capturing it in a ceaseless bombardment of external input.”

Zapffe suggests that these mechanisms of suppression are needed to keep us from being paralyzed by fear. He maintains that one of the crucial functions of any culture is to provide effective suppression, and that many psychiatric disorders should be understood as results of a breakdown of the mechanisms of suppression.

In addition to isolation, anchoring, and distraction, Zapffe lists a fourth strategy: sublimation. Sublimation is the process whereby the tragedy of human life is given aesthetic value. The production and appreciation of art, Zapffe writes, is perhaps more properly called a mechanism of “transformation rather than repression.”

The reason is that while isolation, anchoring, and distraction work by trying to push suffering out of sight, sublimation confronts suffering head-on and seeks to transform suffering into beauty.

(…)

Although art can give us consolation, however, it cannot save us from suffering, the reason for which is that the source of suffering is too deep. We suffer, Zapffe suggests, because of our very nature as humans. Insofar as we use our intellect, which, as humans, we must do in order to sustain ourselves, we are bound to suffer. Insofar as we suppress our intellectual capacities, we reject our humanity and undermine the faculty that is most crucial to our mode of survival. Humanity, therefore, is confronted with the grim fundamental alternative of having to choose either death or suffering.

This is a gravely pessimistic view of the world.

How, then, does Zapffe get from this argument for pessimism to the conclusion that procreation is immoral? One premise on the path to this further conclusion is that life is not just filled with suffering, but is filled with so much suffering, and with so little happiness, that human lives tend not to be worth living. Another premise is that nothing short of extinction can bring human suffering to an end. To appreciate why he holds this premise, notice that in Zapffe’s philosophy, there is no hope that social reform can solve the problem of suffering. Although social reform might perhaps alleviate some of the suffering, he takes the core problem to lie, not in the way in which society is organized, but in human nature. The problem, we might say, lies not in the rules of the game but in the internal nature of the game pieces, and therefore, we cannot expect to be able to solve the problem by changing the rules of the game. The third and last premise, which is implicitly assumed rather than explicitly stated by Zapffe, is that it is immoral to create lives that one cannot reasonably expect to be worth living. If we accept all three of these premises, we have reached the anti-natalist conclusion that it is immoral to procreate.”

#zapffe#peter wessel zapffe#pessimism#antinatalism#suffering#morality#benatar#david benatar#schopenhauer#norway

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

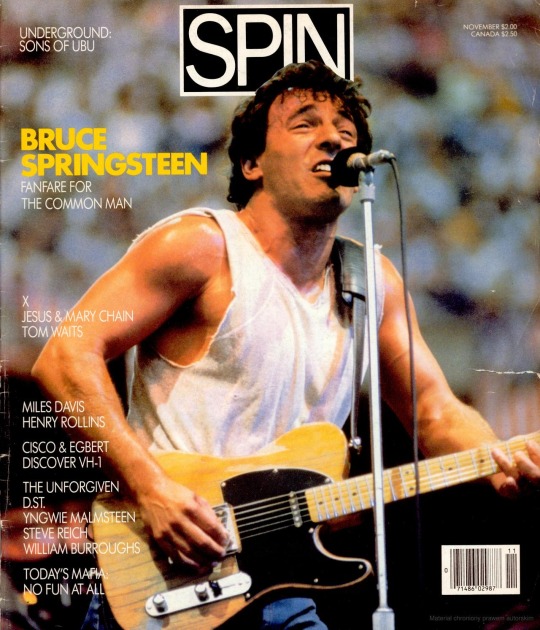

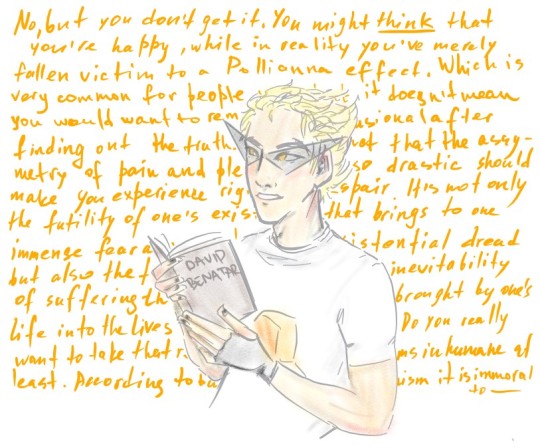

«¿Antinatalismo?»

Desmontando a David Benatar

FILOSOFÍA&CO acaba de publicar un ensayo en el que combato las teorías antinatalistas del filósofo sudafricano David Benatar.

Entra en https://filco.es/david-benatar-antinatalismo/ para leerlo.

P. D. En mi web (https://luismartin.press/david-benatar-antinatalismo-1055/) puedes descargarte el ensayo completo en una versión (PDF) que contiene algunos enlaces que podrían ser de tu interés.

-@luis-martin

#Filosofía#Psicología#david benatar#antinatalismo#antinatalism#kierkegaard#miguel de unamuno#darwin#existencialismo#ensayo#libros

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

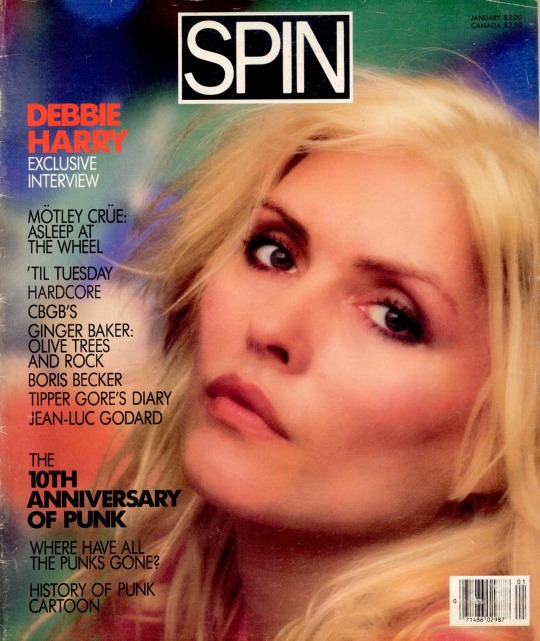

i have philosophy dirk brainrot

#homestuck#homestuck art#homestuck fanart#dirk strider#philosophy#antinatalism#david benatar#rose would definitely shove the second sexism right into his pseudo-intelligent face#because fuck that#why cant male philosophers also be decent fucking people#i relate so heavily to better never to have been#why david benatar why#myart

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

hayata, varolmayışın kutsal sükunetini bozan faydasız bir zaman dilimi olarak da bakabilirsiniz.

david benatar - keşke hiç olmasaydık

#david benatar#keşke hiç olmasaydık#arthur schopenhauer#arthur koestler#friedrich nietzsche#nietzsche ağladığında#blog#blogger#existentialism#varoluşçuluk#milan kundera#varolmanın dayanılmaz hafifliği#Soren Kierkegaard#korku ve titreme#bulantı#kayboluş#Jean Paul Sartre#albert camus#düşüş#yabancı#franz kafka#dönüşüm#charles bukowski#kitap#kitap kurdu#kitap blog#felsefe#Jorge Luis Borges#georges perec#uyuyan adam

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pro-death view should be of interest even to those who do not accept it. One of its valuable features is that it offers a unique challenge to those pro-lifers who reject a legal right to abortion. Whereas a legal pro-choice position does not require a pro-lifer to have an abortion—it allows a choice—a legal pro-life position does prevent a pro-choicer from having an abortion. Those who think that the law should embody the pro-life position might want to ask themselves what they would say about a lobby group that, contrary to my arguments in Chapter 4 but in accordance with pro-lifers’ commitment to the restriction of procreative freedom, recommended that the law become pro-death. A legal pro-death policy would require even pro-lifers to have abortions. Faced with this idea, legal pro-lifers might have a newfound interest in the value of choice.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#antinatalism#abortosim#childfrees antinatalism#antinatalism childfrees#childfreesacidas#maternidademata#childfrees#8 billhoes de fodido#childfreesatemorrer antinatalism#abortolegalseguro#familiaébasedaescravidao#DAVID BENATAR#nascemospramorrer#PROCRIAÇÃO MALEFICA#Youtube

0 notes

Text

David Benatar - The Human Predicament

0 notes

Text

I take a glance at David Benatar after finding him referenced and one thing I find immediately irksome about Benatar is that he talks about the destruction caused by the human species and says if it were any other species "we would rapidly recommend that new members of that species not be brought into existence". The problem there is that the only reason we say that is because we humans, in our civilizations, see ourselves as the proper and even "natural" overlords of the natural world - stewards, if you will, per Christian parlance - and, to that effect we employ eugenic practices of population control, sometimes nowadays under the justification that we are preserving our ecosystems and endangered species within them. So in this sense I find that Benatar's view of the ethical station of the human species ultimately couches itself in what is still eugenicist morality. It is thus by the standards of eugenics and population control that we are to judge our own existence to be so unethical that we might abjure the fact of being born.

To me, however, all that says is that life, in order to persist, ought best to cast off the pitiable morality of justification, and especially the morality that our systems of social domination have conditioned upon us.

1 note

·

View note

Text

David Benatar – İnsanın Çaresizliği (2022)

David Benatar – İnsanın Çaresizliği (2022)

Hayatımızın sahiden bir anlamı var mı yoksa –dostlar arasındaki avutucu söz ve küçük yaşam bilgeliklerini saymazsak– tamamen anlamdan mahrum bir sürecin içinde miyiz?

Çaresizliğimizin ne kadar farkındayız?

Ölüm denilen kaçınılmaz son bizim için kötü bir şey midir?

Ölümsüzlük hayalleri insanlık adına bir ilerleme sayılabilir mi?

Her türlü içinden çıkılmaz durum göz önüne getirildiğinde, ölümleri…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

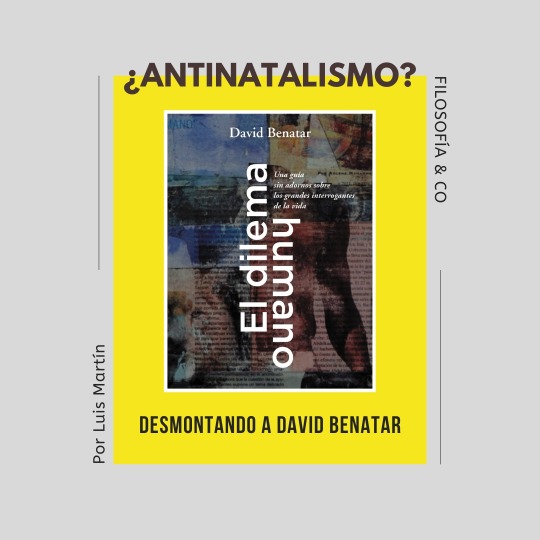

MTV promos

#i want my mtv#mtv#david bowie#billy idol#cyndi lauper#boy george#madonna#hall and oates#pat benatar#1980s#1980s music

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rust Cohle has become infected by women. Women are only watching True Detective to stare at Matthew McConaughey because they don’t understand Pessimist philosophy. Schopenhauer was right.

#PrayForRustCohle #StopTheObjectificationOfRustinCohle #JusticeForRustCohle

#this is funny people#I do believe 95% of Female watchers of True Detective are not familiar with the works of Emil Cioran (they know him probably only because#his work is aesthetically pleasing) or Arthur Schopenhauer / Thomas Ligotti / Peter Wessel Zapffe / David Benatar / Olga Plümacher#the show gets so much more better if you do#any Television series that inspires Academic papers is worth watching!#this is just a joke! you do you and enjoy whatever you like how you like. I do encourage the readings the show was inspired by#that’s my only point. It is a masterful and brilliant show. the allure of Rust is in his morality and his defiance of his philosophy despit#looking as if he is abiding by it

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

“That coming into existence is a harm is a hard conclusion for most people to swallow. Most people do not regret their very existence. Many are happy to have come into being because they enjoy their lives. But these appraisals are mistaken for precisely the reasons I have outlined. The fact that one enjoys one's life does not make one's existence better than non-existence, because if one had not come into existence there would have been nobody to have missed the joy of leading that life and thus the absence of joy would not be bad. Notice, by contrast, that it makes sense to regret having come into existence if one does not enjoy one's life. In this case, if one had not come into existence then no being would have suffered the life one leads. That is good, even though there would be nobody who would have enjoyed that good.” - David Benatar, ‘Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence’ (2006) [page 58]

13 notes

·

View notes