#EDO modification

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Columbia (OV-102) returned to KSC after its 2nd Orbiter Maintenance Down Period (OMDP) overhaul to prepare for its 12th mission (STS-50 USML-1) in June. Later in the OPF Columbia was fitted with the 1st Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) kit allowing for 14+ day missions."

Date: February 9, 1992

source

#STS-50#Space Shuttle#Space Shuttle Columbia#Columbia#OV-102#Orbiter#NASA#Space Shuttle Program#Extended Duration Orbiter Modification#EDO modification#EDO#modification#Kennedy Space Center#KSC#Florida#February#1992#my post

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

MadaTobi Kinktober Prompts 2024

Since I haven't seen anyone do this, I figured I might as well do it myself. (And if someone has already done it, I would very much appreciate the link!) The list is put together with the help of the lovely people on Discord (you know who you are!), and was created in a frenzy today, so if I have missed some double listings, please let me know.

Other than that, I have created a collection on AO3 (MadaTobi_Kinktober_Prompts_2024) where you can add your fic or art made from this prompt list if you want. It is currently unrevealed, but will be revealed on October 1st and I'll close it on December 1st, so that if you can't finish your work on the day, you can still add it to the collection later if you want.

The only rules I have for the collection is that fic needs to be at least 50 words (meaning drabbles are fine.), art needs to be checked that it loads properly from wherever you host it, and the main focus needs to be Madara and Tobirama. That means you can use as many of the prompts as you want, and write as many fics or draw as much art as you like for each day. Pick and choose which prompts you like, and what you have spoons for, and have fun!

List below the break! (Be aware that this is a kink list, so there might be things on it that you do not like, but I have chosen to be inclusive and not judge.)

MadaTobi Kinktober Prompts 2024

1. Tickling – Breath control play – Spit-roasting – Conditioning

2. Bondage – Massage – Loss of virginity – Objectification

3. Public but secret – Age difference – Prostate milking – Rimming

4. Necrophilia – Edging – Dirty talk – Cruising/dogging

5. Monsterfucking – Maid – Riding – Mutual masturbation

6. Sadism/masochism – Glove kink – Shower sex – ABO heat/rut

7. Lingerie – Temperature play – Facefucking – Agility kink

8. Heliophilia/selenophilia (sun/moon fetish) – Cockwarming – Service sub – Cumdump

9. Foot Fetish – Roleplay – Double/triple penetration – Over-the-knee spanking

10. Somnophilia/wet dream – Topping from the bottom – Forced orgasm – Oil

11. Size-difference – Sensory deprivation – Chakra kink/chakra play – Wall sex

12. Crossdressing – Biting – “Shh or they will hear you!” - Latex/Leather/Lace

13. Uniform – Kage Bunshin – Creampie – Discipline

14. Oviposition – Hand job – Feminization/sissification – Power imbalance

15. Master/slave – Mirror – Daddy – Sounding

16. Corsets – Breeding – Voice kink – Object penetration

17. Free use – Oral – Claiming/branding – Photography/recording

18. Pet play – Whips – Belly bulge/cum inflation – Figging

19. Shibari – Femdom – Body worship – Sugar daddy

20. Misuse of jutsu – Overstimulation – Hate sex – Wax play

21. Biker gear – Rape fantasy – Intercrural – Knife play

22. Glory hole – Praise kink – Fisting – Deep throating

23. Exhibitionism – Kama Sutra – Public sex – Gags

24. Trichophilia (hair fetish) – Body Modification – Furry – Doggy style

25. Clone gang bang – Collars – Desk sex - Gym kink/locker room cruising

26. Dacryphilia (aroused by tears) – Knotting – Chastity device – NTR/Cheating

27. BDSM club – Sex training – Degradation/humiliation – Erotic literature

28. Voyeurism – Tantra – Blood play – Hunting/capture

29. Consensual non-consent – Lactation Kink – Drugs/sex pollen – Incest

30. Paddling – Trampling – Begging – Cuckolding

31. Costume – Edo Tensei – Size kink – Safe, Sane, and Consensual

#kinktober#madatobi#mdtb#madara#tobirama#uchiha madara#senju tobirama#naruto founder event#naruto#fanfic#fanart

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (70): Rikyū Said, the Two Mat Room with a Mukō-ro is the Place Where the Sō-an Lives.

70) [Ri]kyū continuously declared, “the two-mat〚room〛with mukō-ro, this was the first place where the sō-an [草菴] took up its abode¹. When the [naka-]bashira was erected, and the ro was relocated onto a different mat to the right [of the utensil mat], this was regrettable².

“From that [early two-mat room] -- this was [done] so that the guests would not feel so constrained -- [the room] increased to three mats, and then four mats³. Year after year, month by month, we have gotten used to doing various things [that were previously unknown]⁴.

“Then, because the size of the room [beside] the daime-tatami could be [manipulated] freely, many kinds of [new] arrangements also became possible⁵. And once various sorts of utensils [that had never been used before in the sō-an] came to be brought out, the effort [to realize the chanoyu of the sō-an] became futile⁶.

“If only things had [remained] as they were in the beginning, with nothing but the mukō-ro! -- since, despite how wonderful [these various innovations and modifications] might seem to be, they never should have been allowed to come into being. 〚[And] if things had remained just as they were, with but a single way to use the mukō-ro, no matter how delightful we might think [the different ways of doing] things are, having a great number of ways to do [the same thing] is wrong⁷.”

〚Time and again, we must reflect on our errors [and strive to do better], so it has been asserted⁸. We have to recognize [Ri]kyū’s unrelenting care and attention to [the realization of] a tea focused on sincerity and truth⁹ -- [because] such conscientiousness has [actually] been the norm since the earliest days¹⁰. It is through words such as these that we also may come to an understanding [of such things]¹¹ -- because a truly considerate chajin is someone who is worthy of praise! How very unfortunate [that such chajin are so few and far between today]¹²!〛

_________________________

◎ Like many of the preceding entries, the toku-shu shahon and genpon versions include comments that are absent from the Enkaku-ji manuscript -- and in the same manner as we have seen heretofore: the first sentence features certain (relatively minor) additions, with several new sentences (in this case, those covered by footnotes 8 to 12) added to the end of the passage. While the existence of different versions suggests that we are probably dealing with a kernel of truth that dates from Nambō Sōkei’s day in this entry, the idiom used by the authors in the present versions of the text also agrees with what we have seen in the similar instances earlier in Book Seven where multiple versions are found that parallel this one, suggesting that all of these sections were written (or edited*) and added to the collection of documents cached in the Shū-un-an by the same person, at the same time.

In the same way that I structured the earlier translations, the additional material from the toku-shu shahon has been incorporated into the above translation (enclosed in doubled brackets, in order to distinguish the additions from the original text). Variations found in the genpon version of the text have been largely dealt with in the footnotes. ___________ *All of the sections that exhibit this same pattern of sequential modification (all of which are restricted to Book Seven) appear to be based on material that had been preserved by Nambō Sōkei. Nevertheless, these passages seem to have been edited (most likely, to bring them into conformity with the teachings of the Sen family -- which is suggested by the Edo idiom that was used by their author) before being returned to Sōkei’s archive.

¹Kyū tsune ni no tamau, ni-jō mukō-ro, kore sō-an dai-ichi no sumai naru-beshi [休常ニノ玉フ、二疊向爐、コレ草菴第一ノスマヰナルベシ].

Kyū tsune ni no tamau [休常にの給う] means (this was) Rikyū’s constant way of speaking*.

Ni-jō mukō-ro, kore sō-an dai-ichi no sumai naru-beshi [二疊向爐、これ草庵第一の住居なるべし]: ni-jō mukō-ro [二疊向爐] means a two mat room with mukō-ro; kore sō-an dai-ichi no sumai [これ草庵第一の住居] means this is the primary† place where the sō-an lives; naru-beshi [なるべし] means (it) should be (like this).

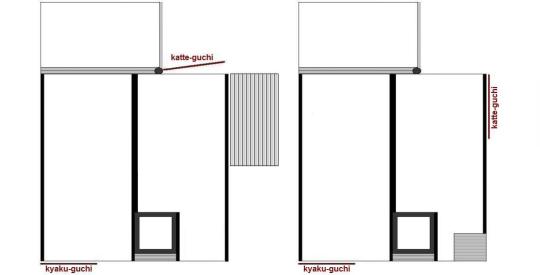

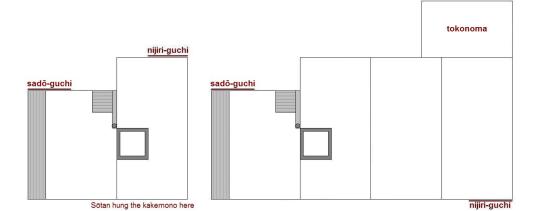

Two versions of Rikyū’s two-mat room with mukō-ro are shown below.

Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon has “Kyū tsune ni no tamau, ni-jō shiki kyaku-tsuke no mukō-ro, kore sō-an dai-ichi no sumai narubeshi“ [休常ニノ玉フ、二疊敷客附ノ向爐、是レ草菴第一ノ住居ナルベシ].

Ni-jō-shiki kyaku-tsuke no mukō-ro [二疊敷客附の向爐]: ni-jo-shiki [二疊敷] means a two-mat room‡; kyaku-tsuke no mukō-ro [客附の向爐] means the mukō-ro is cut on the side of the utensil mat closest to the guests. This is certainly more specific than what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, but the Enkaku-ji manuscript uses forms with which we are already perfectly familiar (after progressing this far in the Nampō Roku), so the lack of specificity is not an issue (and so unnecessary).

The genpon abbreviates the first phrase to “Kyu no iu” [休ノ云], which means (what follows) was (something) Rikyū said. The rest of the sentence is the same as what was said in the toku-shu shahon version. __________ *More literally, Rikyū constantly bestowed (or pronounced) this (teaching) on (everyone with whom he came into contact).

This is an intentional exaggeration, one that was intended to suggest to the reader that Rikyū made an effort to promote the idea that the two-mat room was the origin of the sō-an. This is because, if we look at the documented history of chanoyu in Japan, the first rooms smaller than 4.5-mats were built in the spring of 1555 -- both of which were ni-jō daime [二疊臺目] rooms. The 2-mat room with mukō-ro is not mentioned until years after Jōō’s death (which occurred at the end of 1555).

Apparently Rikyū was looking back to an earlier time -- referring to chanoyu and the concept of the sō-an as these had existed outside of Japan (and probably to alluding to ideas that he encountered during his prolonged stay on the continent) for his precedent.

†Dai-ichi [第一] could also mean foremost or principal here.

It could even be interpreted to literally mean the first (place) -- as in that the two-mat room was the first place where the (idea of the) sō-an took up its abode: that is, the idea of the sō-an began with the guests moving into the 2-mat anteroom where the o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚] was installed, and drinking their tea there (rather than waiting for it to be conveyed to them in the shoin).

‡Literally, ni-jō [二疊], which is what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, means two tatami-mats. However, it is correctly assumed that this is referring to a room of that size. In Shibayama’s text, however, this fact is specified literally.

²Hashira wo tate, migi no betsu-tatami ni ro wo naoshitaru-koto kō-kai nari [柱ヲ立、右ノ別タヽミニ爐ヲナヲシタルコト後悔也].

Hashira wo tate, migi no betsu-tatami ni ro wo naoshitaru-koto [柱を立て、右の別疊に爐を直したること]: hashira wo tate [柱を立て] is referring to erecting a naka-bashira [中柱]; migi no betsu-tatami ni ro wo naoshitaru [右の別疊に爐を直したる] means to decide to relocate the ro onto the mat to the right (of the utensil mat); and -koto [こと] means the case or situation where these things were done -- that is, this is referring to the creation of the 2-mat daime room.

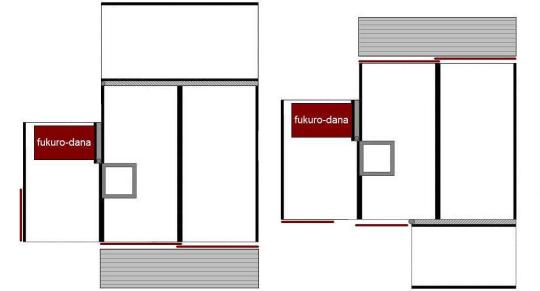

This sketch shows Jōō’s Yamazato-no-iori [山里ノ庵] (left) and Rikyū’s Jissō-an [實相庵] (right), the first two “small rooms” ever seen in Japan*, both of which were built in the spring of 1555. Note that in these rooms, while the fukuro-dana was still used (at least at first), it was completely hidden by the sode-kabe (which extended from floor to ceiling, making everything within the kamae invisible to the guests)

Kō-kai nari [後悔なり] means (the establishment of the 2-mat daime room) was regrettable. In other words, Rikyū is being quoted as having regretted, or been remorseful, that he and Jōō had decided (probably for the convenience of the guests†) to create the 2-mat daime room.

The other two versions agree with the text of this sentence. __________ *At least in so far as what we might call dedicated tearooms was concerned.

Shukō’s original Shukō-an [珠光庵] is said to have been a 2-mat room (with a walled-off, wood-floored recess -- originally a place to store things like bedding during the daytime -- that he used as if it were an o-chanoyu-dana when serving tea); but this was a monk’s residential cell, so its use for serving tea was occasional and temporary.

†Prior to that time, the only kind of room that had been used for wabi-chanoyu was the 4.5-mat room. If a group of guests had suddenly been invited into a two-mat room at that point in time, they would have been completely unprepared regarding where to sit and how to conduct themselves. The 2-mat daime room allows the guests to basically conduct themselves as usual, while reducing the overall space -- in particular, the space used by the host for the display and arrangement of the utensils.

³Sore-yori kyaku-seki no tsumanu-yō ni tote, san-jō ni nari, shi-jō ni nari [ソレヨリ客席ノツマラヌヤウニトテ、三疊ニ成、四疊ニ成].

Sore-yori kyaku-seki no tsumanu-yō ni tote [それより客席の詰まらぬようにとて] means from the early room, in order that the area used by the guests for their seats was not constrained (or useless)... -- that is, so that the guests did not feel boxed in.

San-jō ni nari, shi-jō ni nari [三疊になり、四疊になり] means (the room) became three-mats, four mats. This is referring to rooms of the following sorts.

Because the original two-mat room would seem to confine the guests to too small an area, the room was increased to three mats, and then four mats. The details of these expansions have been discussed elsewhere in the Nampō Roku (both in Book One, and again in Book Seven).

While Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon reproduces the sentence as given in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, Tanaka’s genpon changes the ending, so that it reads san-jō ni mo, shi-jō ni mo nari [三疊ニモ、四疊ニモナリ] meaning that (in addition to the two mat room), rooms of three mats also, and rooms of four mats also, came into being. The basic meaning -- that the size of the room was increased in relatively short order -- is the same. ___________ *The reader may refer to the following posts for further information:

○ Nampō Roku, Book 1 (16): Regarding the Boards that are Inserted at the Far End of the Utensil Mat.

http://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/175652104074/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-1-16-concerning-the-boards

○ Nampō Roku, Book 7 (40): the Deep Three-mat Room.

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/702653075106742272/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-40-the-deep-three-mat

○ Nampō Roku, Book 7 (41): the Naga-yojō [長四疊] Room.

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/703015465673441280/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-41-the-long-four-mat-room%C2%B9

○ Nampō Roku, Book 7 (42, 43, 44): the Sketches for Entries 39, 40, and 41.

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/703287276430655488/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-42-43-44-the-sketches-for

⁴Nen-nen tsuki-zuki iro-iro no koto ni nareri [年〻月〻色〻ノコトニナレリ].

Nen-nen [年々] means year after year.

Tsuki-zuki [月々] means monthly, every month, month by month.

Iro-iro no koto ni nareri [色々] means we get used to doing various things (that move farther and farther away from the tradition established by Rikyū).

In other words the push away from Rikyū’s chanoyu was insidious*; it overwhelmed every trace of what had been there before.

While this sentence is the same in Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon, it is completely missing from the genpon version of the text. __________ *While this statement is very true, we must remember that this is not really talking about Rikyū’s actual style of chanoyu (which had already been all but forgotten), but the machi-shū tea (derived from the teachings of Imai Sōkyū) that was being championed by the Sen family. The second half of the seventeenth century was when the opposition to the Sen family (ironically, by the daimyō whose ancestors had been trained personally by Rikyū, and whose movement was technically intent upon repudiating Sōtan’s changes and restoring Rikyū’s chanoyu) began to reach fever pitch.

Unfortunately, this fledgling back-to-Rikyū movement was damned to failure on account of the fact that Rikyū’s densho (which were the only bridge between Rikyū and the chajin of the second half of the seventeenth century) were always written for a specific person, to answer that individual’s specific questions; and his answers were always predicated on the understanding that his correspondent already possessed. Thus, when the bakufu finally permitted the daimyō to restore the Rikyū-derived traditions that had been passed down within their families, their basic approach to the practice of temae had already been irreparably corrupted by their having been forced to imitate the manner of Sen no Sōtan for two generations, as much as by the fact that Rikyū’s densho are notoriously incomplete when viewed individually. (It was only possible to collate and summarize Rikyū’s actual teachings only after Suzuki Keiichi published his Sen no Rikyū zen-shū [千利休全集] -- in 1941 -- because that was the first time that all of the densho had been collected together, allowing them to be compared, and the blanks in one filled in with information that had been disclosed in one of the others.) The result was that, though the original idea had been to restore Rikyu’s chanoyu, this concatenation of circumstances meant that every daimyō moved off on his own tangent, as a consequence of the coloring of their pre-existing Sōtan-style chanoyu with a patina of only those Rikyū-based teachings that had been imparted specifically to their ancestor (while remaining largely, or wholly, ignorant of everything that had not been communicated, in writing, to that person -- since only the written word remained, while everything that had already been known by their ancestor, and so not mentioned by Rikyū in the densho that he wrote for that person, was long forgotten, suffocated under the unprecedented weight of Sōtan’s machi-shū tea).

⁵Mata daime-datami hiroku jiyū naru-yue, shu-ju no oki-awase mo dekiru [又臺目ダヽミ廣ク自由ナルユヘ、種〻ノ置合モ出來].

Mata daime-datami hiroku jiyū naru-yue [又臺目疊廣く自由なるゆえ] means because the largeness (of the room) of the daime (setting) could be (manipulated) freely....

In other words, because the number of mats that could be added to the right of the daime was free and unrestricted*....

Shu-ju no oki-awase mo dekiru [種々の置き合わせも出來る] means various kinds of arrangements were possible.

The toku-shu shahon and genpon texts add the word kazari [飾 or カザリ] before oki-awase [置合]. Oki-awase means the arrangement (the way the objects are placed out together on the mat); kazari oki-awase [カザリ置合] means the arrangement of the kazari. This has no impact on the English meaning (since the fact that it is the kazari that is being “arranged” is already understood from the context). __________ *This experimentation began with Sōtan's original room, which had just one mat to the right of the daime. As a result, the original Fushin-an [不審庵] was not a sukiya [数奇屋] because it failed to give the guests an unobstructed mat for their own use.

This is why, once the family became the prominent force in the world of contemporary chanoyu, Sōtan's son Kōshin Sōsa [江岑宗左; 1613 ~ 1671] added not just one, but two additional mats beside the mat in which the ro had been cut, making it an early example of the three-mat daime room.

Jōō’s Yamazato-no-iori and Rikyū’s Jissō-an, the first two daime chaseki, were, of course, two-mat daime rooms. They are illustrated under footnote 2, above.

Later on, even larger numbers of mats were added next to a daime utensil mat -- sometimes making the daime utensil part of a shoin-style room. These rooms are part of the corrupt trend that was discussed in the previous two footnotes.

⁶Sama-zama no dōgu wo tori-dashi, mu-yaku no koto ni narinu [サマ〰ノ道具ヲモ取出シ、無益ノコトニナリヌ].

Sama-zama no dōgu wo tori-dashi [様々の道具をも取り出し] means various sorts of utensils* were brought out (in these expanded versions of the daime setting).

Mu-yaku no koto ni narinu [無益のことになりぬ] means these reckless (variations) will not be of any use.

The reason for this being futile or useless is that the goal was to realize the chanoyu of the sō-an, and the introduction of the utensils and arrangements that had been created for the daisu-shoin setting is counterproductive†.

The second phrase of Shibayama's version is mu-eki no koto nari [サマ〻〻ノ道具ヲモ取出シ、無益ノコトナリ]. This means (bringing out various utensils) is futile.

There is no real difference between what these two variants are trying to say.

This sentence is completely missing from the genpon version of the text. __________ *The implication is that these various utensil combinations were never sanctioned for use on the daime, and are only being attempted because the rest of the room has expanded to the point where it is now for all intents and purposes a shoin.

†As this was the direction that chanoyu had taken during the Edo period, this entry is, at least in part, a protest against this trend.

⁷Hajime no gotoku mukō-ro bakari naraba, ika-hodo mezurashiki-koto wo subeki to omotte mo, naru-bekarazu to iu-iu [始ノゴトク向爐バカリナラバ、イカホドメヅラシキコトヲスベキト思テモ、ナルベカラズト云〻].

Hajime no gotoku mukō-ro bakari naraba [始の如く向爐ばかりならば] means “if, as in the beginning, only the mukō-ro was being used....”

In other words, if none of the other variants (such as the daime) had ever been proposed -- if the sō-an had been strictly limited to rooms where tea was made with a mukō-ro*....

Ika-hodo mezurashiki-koto wo subeki to omotte mo [如何ほど珍しいことをすべきと思っても] means “no matter how wonderful (diverging from the tea of the mukō-ro) might be considered to be....”

Naru-bekarazu to iu-iu [なるべからずト云々] means “it should never have been done.”

This is the end of the passage, as it is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

The toku-shu shahon text, on the other hand, has hatsu no mama mukō-ro to hito-dōri naraba, ika-hodo mezurashiku-sen to omōte mo, amata no koto ha naru-majiki nari [初ノマヽ向爐一通ナラバ、イカ程珍ラシク��ント思フテモ、アマタノコトハナルマジキナリ].

Hatsu no mama [初のまま] means just as in the beginning.

Mukō-ro hito-dōri naraba [向爐一通りならば] means even if there had only been one way (to use) the mukō-ro....

Ika-hodo mezurashiku-sen to omote mo [如何程珍らしく爲んと思うても] means even if you think (the variations are) extremely wonderful to do....

Amata no koto ha [數多のことは] means a great number of ways to do (something)....

Naru-majiki nari [成る間敷きなり] means (this) should not be done.

In other words, “even if, just as in the beginning, the mukō-ro had (always) been used in only the one (original) way, even if (the variations) seem wonderful, having many options is not appropriate.”

The argument here is not that it is the deviations from the mukō-ro setting that were problematic, but that numerous variations on the way to do things (with the mukō-ro), the various forms of the mukō-ro temae (each with its own secret rules, connected with specific utensils), is what is uncalled for. Rather than trying to come up with different ways to do things in order to “spice up” the gathering (as is often the rationale behind the many modern variations), people should content themselves with using the mukō-ro as it was originally intended to be used† -- since the purpose of chanoyu in the sō-an is to prepare and share a good bowl of koicha, so the most expedient way of doing that is best.

For this reason, I decided to include this version at the end of the paragraph, even though it, to a large extent, repeats what has just been said in slightly different words (that produce a different meaning), with the text enclosed in doubled brackets.

The genpon text includes this version of the sentence. __________ *When the ro was first introduced (in the 4.5-mat room setting), Jōō’s intention was that it should have been used all year round.

The same idea appears to have been in the back of Rikyū’s mind, regarding the two-mat room with mukō-ro.

That is why rooms with a ro were considered sō-an -- because they did away with the elaborate trappings (the costly metal furo, or even one made of clay, and the various ways of arranging the room that this utensil demanded).

The first time a furo was used in the small room (in 1586) was when Rikyū created the Yamazato-dana [山里棚] for Hideyoshi to use when serving tea in his Yamazato-maru [山里丸] -- the two-mat room in the boathouse on the moat within Hideyoshi’s Ōsaka castle compound. The purpose was, like with the daisu, to have everything already ready in the room, so that Hideyoshi could enter, simply serve tea (without having to go back and forth from the temae-za to the katte bringing things out) while talking with his guests, and then leave with them (without having to empty the utensil mat afterward).

The first time a furo was used in the small room in a public setting (the guests visiting the Yamazato-maru were, of course, Hideyoshi’s intimates) was when Rikyū did so in the two-mat room he constructed within the tea village in the pine-barren that surrounded the Hakozaki-gū in 1587. That room featured a mukō-ro; but when Rikyū wanted to use the small unryū-gama in that setting (perhaps as a way to keep the heat to a minimum), he did so by placing the large Temmyō kimen-buro (that had been Nobunaga's treasure) on top of the closed lid of the mukō-ro -- causing the guests to comment that Rikyū had placed the furo directly on the floor. While Rikyū seems to have done this as a subtle way to reinforce the continuity between Nobunaga’s reign and that of Hideyoshi (a point that was still being doubted by some of the influential citizens of Hakata), both of these details were initially unnerving to the chain of that area, because they violated the recognized conventions. (Though, after thinking things through, they also opened up possibilities that had never been considered before -- and thus were imitated in quick order by the chajin of Hakata.)

†This accords with the criticism of the chanoyu of the capital mentioned at the end of the previous entry (in the genpon version of the text), that the chajin of the capital had become so caught up in the idea of doing things differently for the sake of making the gathering more interesting (and challenging -- since only the members of a small group would understand exactly what to do, while those who had studied with a different teacher might find themselves stymied) -- that they had completely lost touch with Rikyū’s (or, rather, the Sen family’s) teachings on the correct way to practice chanoyu.

The reader will notice a certain continuity of idiom between that entry (in the genpon) and the present one (as found in the same source) that confirms this interpretation of the relationship between these two passages.

⁸Kaesu-gaesu ayamachi to koso oboyuru to mōsare-shi [返ス〻〻過チトコソ覺ユルト被申シ].

From this sentence on to the end of the entry, we are considering ideas* only found in the toku-shu shahon and genpon texts. All of this material is missing from the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

Kaesu-gaesu [返す返す] means repeatedly, time and time again, again and again, over and over.

Ayamachi to koso [過ちとこそ] means precisely those mistakes (that you have fallen into repeatedly).

Oboeru to mōsare-shi [覺えると申されし] means it is said that (it is just those mistakes) on which you should focus your efforts (to eliminate them from your practice).

Tanaka’s genpon text has kaesu-gaesu ayamachi to koso oboere to mosare-shi [カヘス〰アヤマチトコソ覺レト被申シ]. The change means “(you) are urged to remember (i.e., look into) the mistakes to which you return again and again.”

While the wording is slightly different, the essential meaning -- that one should actively criticize one’s own temae, and take whatever steps are necessary to correct one’s mistakes -- is the same. __________ *Perhaps “admonitions” would be a better word for these dicta. The pedantic neo-Confucian tone that became more and more a feature of chanoyu instruction in the late Edo period (and beyond -- including in the modern day) is increasingly apparent in these added sentences.

⁹Kyū no kokoro-ire ha kure-gure magokoro-makoto no cha wo omoi-torite [休ノ心入ハ呉〻眞心眞實ノ茶ヲ思ヒ取リテ].

Kyū no kokoro-ire [休の心入] means Rikyū’s care and attention (to every aspect of the practice of chanoyu).

Kure-gure [呉々] means repeatedly, again and again, over and over.

Magokoro-makoto no cha [眞心眞實の茶] means that Rikyū’s tea was truehearted (absolutely sincere) and genuine (revelatory of the truth).

Omoi-toru [思い取る] means to realize, to understand, to be considerate of (something), to decide (upon), to make up one’s mind.

In other words, Rikyū was always careful that chanoyu be always and deeply concerned with sincerity and truth*.

The identical sentence is found in Tanaka’s genpon text. __________ *These remarks can be considered part of what we might call the apotheosis of Rikyū -- turning him from a devoted and dedicated practitioner of chanoyu into a superhuman tea kami whose purpose was to guide the tea community toward truth and sincerity. The remainder of the entry is intended to glorify him in the eyes of the reader.

¹⁰Kokoro-zukai arishi-koto [心遣アリシコト].

Kokoro-zukai [心遣い] means things like consideration, thoughtfulness, attentiveness, solicitude (being solicitous toward some principal).

Arishi-koto [在りしこと] means (this attitude of attentiveness) has existed since the early days.

The criticism seems to be that the mindless and formalistic way of practicing chanoyu is a recent aberration.

Once again, the genpon text includes the same sentence.

¹¹Kayō no kotoba ni te mo shiraruru nari [ケ様ノ言ニテモ知ラルヽナリ].

Kayō no kotoba ni te mo [斯様の言葉にても] means (it is) also through words of that sort (i.e., the ideas discussed in the previous footnotes).

Shirareru [知られるなり] means (this concept) is made known.

In other words, a chajin’s greatness can be known not only through descriptions of his doings, but also by contrasting him with the usual ways of the world.

Here again, Tanaka’s genpon source agrees* with the toku-shu shahon text. __________ *That said, the kanji used in Tanaka’s version are less ambiguous: kayō no kotoba ni te mo shiraruru nari [カヤウノ辞ニテモシラルヽ也].

Kayō [カヤウ] is a phonetic representation of the expression, while kayō [ケ様] is one of those weird written mannerisms that were so popular around the middle of the Edo period.

Likewise, kotoba [辞], which means language, words, expressions, etc., is clearer than kotoba [言] -- which, as a kanji, is more commonly used to refer to speaking or speech. Today the classical kotoba [言葉] (“the leaves of speech”) is, of course, preferred over these other two.

¹²Shinsetsu kidoku no chajin oshimu-beshi oshimu-beshi [深切奇特ノ茶人可惜〻〻].

Shinsetsu kidoku no chajin [深切奇特の茶人]: shinsetsu [深切] means things like kind, gentle, considerate, generous, and so forth; kidoku* [奇特] means to be worthy of praise.

Thus, someone who embodies the virtues that we have been discussing in the past several footnotes is a chajin who is worthy of praise.

Oshimu-beshi oshimu-beshi [惜しむべし惜しむべし] is a lament (the repetition gives added emphasis) -- that chajin of this sort are all but unknown in the contemporary world of tea. It would be translated by expressions like “how sad,” “such a loss,” “how unfortunate,” “how regrettable,” and so on.

This can also be interpreted as a specific lament over the loss of Rikyū -- since he clearly has been drawn as the personification of the ideal chajin.

Though the genpon text spells out the second phrase (oshimu-beshi oshimu-beshi [惜ムベシ〰], as opposed to oshimu-beshi oshimu-beshi [可惜〻〻] as found in Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon), the sentences are actually identical. __________ *Today, kitoku [きとく = 奇特] seems to be the preferred pronunciation.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

XP Grind Begins: The Games That Will Dominate 2025

With the current generation PlayStation and Xbox systems well into their lives and Nintendo most likely launching the successor to the Nintendo Switch, 2025 is shaping up to be a very fascinating year for video games. Not to mention all the exclusives that will undoubtedly be available on PC and mobile devices.

You may find some parallels if you look at the list of titles scheduled for 2025 below. So far this year, virtually few release dates have been announced. Developers are reportedly waiting for GTA 6 to reveal its release date. Nobody wants to compete with the eagerly awaited blockbuster, just like with Wicked: For Good or an unexpected Beyoncé album. This also applies to when the recently revealed Nintendo Switch 2 is available for purchase.

Assassin’s Creed Shadows

Almost all AAA game companies started developing a game with a main character wielding a samurai sword after Sekiro's popularity. I am referring to video games such as Rise of the Rōnin and Ghost of Tsushima. Naturally, Ubisoft finally decided to put one of their yearly Assassin's Creed games in Japan during the Edo era.

Doom: The Dark Ages

Appealing to some of the niche player fanbase, Bethesda finally announced a new Doom game. Narratively, Doom: The Dark Ages is a predecessor to the 2016 relaunch of the new Doom series. With all-new firearms, a shield, and a variety of flail-type weapons for close combat, it's more of a fresh twist on the formula than a sequel. A mech is also present. A mech dragon, too.

In a nod to the original Doom games, Doom: The Dark Ages is stepping back from the fast-paced action of Doom Eternal and returning to horizontal battlegrounds. We are excited for everything that it means because it appears to be a totally fresh concept for the series.

Elden Ring Nightreign

Honestly, this felt more like a wild card entry. After suffering from tremendous success and creating a beautiful story, we were sure of no Elden Ring sequel. Nevertheless, Elden Ring: Nightreign, which is scheduled for release in 2025, will make the terrible ordeal of repeatedly dying for the same boss a common event. By the end of May, the multiplayer version of Elden Ring will be available.

Given that the cooperative spin-off appears less like a full-fledged sequel and more like FromSoft made everyone's illicit multiplayer modifications an official product, I suppose Miyazaki was partially telling the truth. In addition to having elements of rogue-like, Monster Hunter, and battle royale games, it is still fundamentally a Souls game.

Death Stranding 2

Video game creator Hideo Kojima is working diligently to complete the follow-up to the controversial Death Stranding video game from 2019. Players navigated a vast terrain to repair a damaged planet in the action game and package-delivery simulator, which starred Mads Mikkelsen and Norman Reedus. When Death Stranding started to resemble the Covid-19 outbreak, which began just weeks after the game's release, its popularity began to grow. Kojima is now preparing the follow-up for a 2025 release.

On this one, Kojima is giving it his all. George Miller, the director of Mad Max, makes brief appearances, and there are men playing electric guitars and little talking puppets.

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 3+4

This summer, a brand-new Tony Hawk Pro Skater game will be released. In technical terms, it is both a sequel and a remake of the excellent Pro Skater 1+2 remake. Just a few months before to its summer release date, the title was revealed.

This will be the first time that generations of players have played these old games on a contemporary system. Numerous enthusiasts believe that THPS 3 is the finest in the series specifically. It will be interesting to revisit Pro Skater 4 with a new look because it is the most neglected of the original tetralogy.

Borderlands 4

Compared to the 2019 release of Borderlands 3, the well-known looter-shooter game has a lot of competition. However, Gearbox Software, the game's creator, is optimistic that devoted fans will return for the upcoming release. After all, Borderlands 3 sold over $15 million, and the fan base is clearly eager for a sequel.

Although I am unable to comment on the current situation of that terrible-looking Borderlands film, I can attest that Borderlands 4 is a much-anticipated video game that doesn't require any prior knowledge of the film. The firearms appear ill, too. After four tries, it appears like this follow-up is finally fulfilling the original Borderlands' promise.

The Witcher 4

The Witcher 4 intends to move away from Geralt and follow Ciri, his adoptive daughter. At the 2024 Game Awards, a cinematic teaser was unveiled, promising an expanded narrative that will expand on The Witcher's renowned lore.

The teaser included some of the most intriguing content from the Game Awards, but there isn't an official release date yet. Even if it wasn't gameplay, players will enjoy any updates made to The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt.

2025 seems to be packed with great titles and even greater hype for all of them. From GTA 6 to Days Gone Remastered, everything seems to be chaotic. The wallets are definitely going to take a hit this year, but if the game is good, its money well spent.

0 notes

Text

Le 16 août

Le Obon

La fête des fantômes, qui dure 3 jours, en 2022 la fête se terminait le 16 août. Note historique! La fête des fantômes, origine de Chine, mais remise au goût japonais, au début c’était une fête religieuse fixée le 15ème jour du septième mois selon le calendrier lunaire traditionnelle, mais à l’ère Meiji il y eut une modification du calendrier pour s’harmoniser avec le calendrier Grégorien, donc de ce jour la fête du Obon ne se fête pas à la même date partout au Japon.

De fête religieuse à réunion familiale

Obon fête rituelle bouddhique, cette courte période est une période de vacances nationales où les japonais se rencontrent en famille pour rendre hommage à leurs proches décédés et leurs ancêtres sur sept générations. Car durant le mois des fantômes, les âmes négligées se vengent en tracassant leurs descendants ingrats.

À Kyoto, à la fin de l’Obon, le 16 août au soir à 20 hrs on fête le feu du Daimonji. Sur les montagnes de Kyoto 6 immenses kanji sur 5 montagnes sont enflammés.

Gozan no Okuribi, la fête des feux pour célébrer la fin du Obon. La forme des kanjis sont permanentes sur les montagnes, mais pour les faire flamber la nuit venue, toute la journée des bénévole installent des plaquettes de bois où le nom du défunt que l’on veut honorer est inscrit.

Le rituel commence à 19h, avec la lecture de sutra au pavillon d’argent puis les kanjis sont enflammés à tour de rôle dans un ordre précis. Les plaquettes avec les noms des défunts brûlent et indiquent au défunt qu’il est temps de retourner dans l'autre monde.

Pour la soirée, il était prévu de se rendre sur place pour vivre l’expérience des feux en personne. Le moment venu, on sort de l’hôtel et on se dirige vers l’endroit que l’on avait choisi à une distance de 20 à 30 minutes à pied mais il pleuvait, et de plus en plus fort, à tel point que je n’avais jamais vu une telle pluie. On a été obligés de rebrousser chemin et de regarder les feux à la télé, car l'événement a une couverture télévisuelle.

On verra plus loin les incidents causés par la pluie, mais je vais pour illustrer ce chapitre prendre des photos d’archive.

Plus tôt en début d’après-midi on a été à un temple bouddhiste japonais de tradition Shingon fondé en 823, Tō-ji (temple de l’est), sous le règne de l’empereur Kenmu en période Edo. Sur le site se trouve une pagode inscrite au patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO. La pagode fait 55 mètres sur 5 étages érigée en 1643, reconstruction, car la pagode d’origine du 9eme siècle fut détruite et reconstruite quatre fois. Le temple comprend un domaine, un jardinet et un étang.

次-suivant

0 notes

Photo

Star Wars AU ~~ Dark Jedi Tobirama

Once an avid student of the Jedi Temple and a powerful Jedi Master, personal tragedy and dissatisfaction with what the light side of the Force had to offer had Tobirama turn to the dark side of the Force, to gain its power and to understand and explore it. He does not shy away from its crueler aspects, but rather finds himself revelling in the power it offers him.

He does not follow the Sith, because he deems their approach to the Force as much too esoteric and emotional, and has no desires of building an empire for himself - he merely follows his own agenda of protecting his last remaining brother - no matter the cost or the sacrifice.

What intrigues him the most, though, are the rumors of a Sith lord, who could undo death with the power of the Force. If he learned this technique, would he be able to bring his lost brothers back?

While Tobirama tries to regain the brothers he has lost, Hashirama tries to keep the brother he still has left.

#tobirama senju#naruto#naruto fanart#naruto au#star wars au#dark jedi#btw: regarding tobirama's looks I wanted him to look kinda washed out and haggard because using the dark side def comes at a price#obviously tobirama is being pretty hypocritical here because his own desire to use the dark side of the force is rooted in deep emotions as#but he'd never admit it#hashirama is kinda like qui gon jinn#not 100% by the rules + the living force but still a jedi#he is alsy very much not excited that his last brother fell to the dark side#and he definitely has an affair with mito#but he handles it better than ehhh certain skywalkers#edo tensei is the ninja version of#the tragedy of darth plagueis the wise#also tobirama didn't so much fall to the dark side he more like jumped#character sheet#sorta#also tobi's got like the major sith design options: facial modification of any sort and red eyes#digital art#fanart

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashion in Uroboros

A brief overview of the different styles of fashion within the IF's setting! It was going to be much longer than it is now, since I initially explained the reasoning I chose these... but I'll resist!

Note that the fashion is not aiming to be authentic. In fact, I've highlighted some of the different ways I've attempted to make these extremely different styles take influence from one another, and even modified them to make more sense thematically for the story.

The fashion is merely inspired, not necessarily accurate to the fashion they're inspired from. Realism isn't the goal, but I still want them to be somewhat convincing, and also cool-looking! I'll also add more thoughts towards the end on this note.

༺═──────────────

Southwestern Galaio - Takes inspiration from Rococo fashion, in part because its climate is similar to western Europe (oceanic climate). Extravagant and blindingly opulent, though I envision it as incorporating more naturalistic elements, such as birds and flowers into their design. However, their design also tend to be asymmetrical and large-scaled.

Portrait of Anastasia Ushakova by Ivan Kusjmitsch Makarov; painting by Lucius Rossi; and "The proposition" by Arturo Ricci

Western Galaio - Takes inspiration from Song Dynasty China, as it also has a humid subtropical climate. A time of prosperity as well, but I chose it over the Tang Dynasty because the designs are more simplistic. I wanted this region to be more muted, but still elegant in fashion compared to other regions. Not as flashy, and much less concerned about extravagant wealth. Though it's in Song style, I enlisted the help of an article to help me incorporate some western elements to it, such as lace and fans.

Lexie from Hanfu Story; Bleu from Hanfu Story; and Butterfly Dream from NewMoonDance!

Central Galaio (Part 1) - Humid continental climate. Closer to the southwest, their fashion reflects much of Rococo style as well, but with some modifications (no train for dresses, etc.). This is in reference to Catherine the Great's time, in which Russia had oriented itself towards European fashion (specifically, the Rococo style), but Catherine the Great dictated the fashion to be more Russian and instill national pride.

Catherine the Great by Fedor Rokotov, 1763

Central Galaio (Part 2) - Farther from the southwest and more towards the north, their fashion is much closer to Western Galaio. They still have elements of the southwest, but they have a strong emphasis on functionality and practicality, which the southwest appears to be fundamentally against.

hanfu by 瞳莞汉服 (left and center); photography by 松果sir and model @白川鹅 (right)

Central Galaio (Part 3) - There's a distinct region that is a cold desert. Here is inspired by Mongolian deel. It's thicker and has several layers to withstand the cold, compared to Western Galaio's clothing, which in contrast have lighter fabrics.

13th century Mongolian deel from Mongulai, founded by Telmen Luvsandorj

Eastern Galaio - Also a wealthy coastal region of Galaio. Mediterranean climate. They take inspiration from the extravagance of the southwest, but fashion is looser, free, and light. The colors are also more natural, like white, brown, blue, etc. rather than the entire spectrum of colors that the southwest and west enjoy.

Deities - Inspired by Edo period Japan, another period of flourishing economic growth. The fashion of the deities likely came from the fashion of a past time, rather than a reflection of current human fashion. Western and Central Galaio's clothing look similar to the kosode gods wear, perhaps because these regions are more rooted in tradition compared to Southwestern and Eastern Galaio. The major modification I made for the fashion of deities, however, is making it more unisex and more relaxed.

From Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Mary Griggs Burke Collection; and from asianhistory.tumblr.com

Additional Notes

I had tormented myself a lot over authenticity, but I realized the fashion can remain merely inspired, not directly referenced. I'm not actually trying to make a Walmart version of France or any of these cultures. However, I do hope that the admiration I have for these cultures shine through!

A lot of these come from periods of prosperity, the "golden ages". Galaio is beautiful and prosperous, but it obscures a deep ugliness within.

These may be subject to change, and won't be super prominent in the story itself. They merely gave me a general idea or silhouette of the kind of clothes people may wear. I think the most reference I'll give them within the IF is a general aesthetic of the clothes rather than specific details. Hence why they're merely inspired.

Thanks for reading thus far! :)

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tessen

Fighting fan

Mid Edo Period (1615 - 1867)

Iron, paper with pigments and bamboo.

Menhari-gata (opening fan), sensu-gata (traditional shape)

Lenght: 33.5 cm

The folding fan, which was usually carried in one's hands or tucked into one's obi (sash), was an important part of Japanese etiquette during the Edo period, especially on formal occasions, and was never out of a samurai's possession. Perhaps because it was regarded as such a commonplace item, it could be easily adapted as a suitable side arm with only minor modifications. These tessen weapons, which literally mean "iron fan," were made of either an actual folding fan with metal ribs or a non-folding solid bar of iron or wood shaped like a folded fan. During the Edo Period, the tessen was a popular self-defense weapon for impromptu situations. There were numerous situations in which a samurai would be unable to use his sword. For example, when visiting another person's home, particularly that of a superior, a warrior was generally required to leave one or both swords with an attendant at the door. To prevent violence, obvious weapons like swords, daggers, and spears were strictly forbidden within the small confines of Edo's pleasure districts like Yoshiwara. A tessen, on the other hand, was acceptable in any situation, leaving the samurai with at least one pretty efficient defensive weapon at all times.

The rising sun, symbol of Japan, decorates both sides, painted in red on a silver background, left natural on one side and yellowed on the other.

The outer iron slats are decorated in silver nunome zogan in geometric patterns and include the aoi-type kamon (family crest) used by the Tokugawa family, depicted in variations with different colorations.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

yesssss i have long held the notion that tobirama is most likely to go body modification, given the types of experiments necessary for his jutsu. it's either graverobbing or pulling his whole soul through space-time for funsies. dude would find a way, i believe he was tragically killed before he could finish all his projects ... which would then mean that shisui's cursed on both lines?

The idea of Tobirama dying before finishing all his projects will forever be a beloved hc of mine, especially since we know for a fact that his Edo Tensei technique was incomplete and Orochimaru found it and perfected it so it's possible that he had many other projects in the making

(For example, I hc that the experiment that eventually created Yamato also came from Tobirama)

And now I'm thinking of an AU where Shisui is actually TobiKaga's biological kid, but Tobirama dies before he can finish the experiment and Kagami knows next to nothing about it because Tobirama wanted it to be a surprise, and years later with all the shit that goes down with Orochimaru the half-finished experiment for Shisui gets found in an old lab that Tobirama used when still alive and gets finished

Orochimaru then decides to create Yamato by trying to remake Tobirama's experiment but he's not successful (in fact Yamato was the only survivor out of Idk how many children, and Orochimaru didn't even realize until much later when he meets Yamato with Team Kakashi) and eventually gets chased out of the village

Shisui is already a couple years older and Hiruzen found him when he went to face off Orochimaru and found all the notes Tobirama left behind + some Orochimaru himself added and decides to use Shisui as a political pawn to try and get the Uchiha back on the Village's good side + guilttrip Tsunade into coming back since technically Shisui would be her relative (Tsunade is Hashirama's granddaughter and Shisui would be Tobirama's son... That would make Shisui her cousin... I think) and Hiruzen knows that Tsunade would never abandon her family

Oooh that'd be an amazing AU. Shisui and Yamato experiment buddies. Maybe Tsunade also adopts Yamato when she finds out about him. Shisui, Yamato and Shizune growing up as siblings would be just as amazing as it would be chaotic

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlantis (OV-104) at Rockwell International's (now Boeing's) Plant 42, in Palmdale, California for modification.

"On November 5, 1997, Atlantis again arrived at Palmdale for her second Orbiter Maintenance Down Period (OMDP-2) which was completed on September 24, 1998. The 130 modifications carried out during OMDP-2 included glass cockpit displays, replacement of TACAN navigation with GPS and ISS airlock and docking installation. Several weight reduction modifications were performed on the orbiter including replacement of Advanced Flexible Reusable Surface Insulation (AFRSI) insulation blankets on upper surfaces with FRSI. Lightweight crew seats were installed and the Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) package installed on OMDP-1 was removed to lighten Atlantis to better serve its prime mission of servicing the ISS."

Information from Wikipedia: link

NASA Photo by Tom Tschida

Date: August 14, 1998

Uploaded to Flickr by Cliff Steenhoff

NASA DFRC: EC98-44703-01, EC98-44703-08

#Space Shuttle#Space Shuttle Atlantis#Atlantis#OV-104#Orbiter#NASA#Space Shuttle Program#OMDP-2#Orbiter Maintenance Down Period#August#1998#Palmdale#California#my post

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've returned from my short hiatus away from the XA Discord, and it's given me a chance to change my perspective on how I conduct myself and approach my music.

I went through some older projects last night, and I was reminded of how beautiful 24edo can be. As much as I wanted to avoid 12edo's diatonic scale, it can often be unbeatable. I tried retuning the relevant passages any way I new how, even resurrecting my knowledge of 39edo for the sound intermediate between 12 and 27edo. But nothing surpassed 12edo's perfect stability in those cases, borne from a pure unaltered diatonic scale with a near-just 3/2, and the thirds being a mix of meantone concordance and neogothic darkness, the latter of which produces a melodically favorable scale. At that point, I decided that I'm done experimenting with retuning for some time. The quasi-aeolian pental lattice with septimal modifications is my main framework, and I already have most of what I need in my five most tested diatonic edos. It's time to perfect my praxis.

27edo: Darkness with an unmistakable glint. Chord progressions sound remarkably natural here, and the 89-cent 16/15 is uniquely practical. Pental blackdye is conveniently a subset of superpyth[12] and 5:6:7 is very well approximated.

29edo: A neogothic diatonic that can be considered microtempered for my purposes, close enough to Pythagorean tuning to truly bring out the beauty of the pipe organ. Primes from 5 to 13 have large but bizarrely similar errors, which cancel out in ratios due to all being in the same direction. The furthest from a full septimal tuning system that I will use for diatonic-based music.

24edo: The middle of everything, and the safest bet for transcribing the melodies in my head. The 11/8 is very aesthetically fitting for its diatonic scale, and the septimal intervals becoming interseptimal is unexpectedly appropriate as well. It's a sound I didn't know I missed. 12edo diatonic is the mediant between 27 and 33, or 29 and 31, and its superset of 24 is the only edo on this list to break the 27 + 2n pattern. I could have chosen 36 as my multiple of 12, but I simply have no interest; in some ways, 24edo feels like the perfect tuning. Quarter tones cannot be done better, and I believe that this is what semiquartal is meant to sound like. Before I started xen composition in earnest three years ago, I decided that 24edo was my favorite tuning. It may be a coincidence, or perhaps I haven't given enough credit to knowledge without wisdom. 9:12:16:19 and 16:19:22 are very well approximated.

31edo: I haven't been using this one nearly as much as I used to. It's capable of some remarkable sweetness with the right instrumentation due to the excellence of septimal meantone; like 29edo, it currently has a precise use case for me. It does septimal diasem in a very practical and straightforward way, and its 8/7 is a useful theoretical generator.

33edo: An old interest turned anew. Similarly to 32edo, its unusual tempering of the pental lattice requires use of the second best prime 3 for full expression, but this time replacing the focus on the grave fifth with the grave fourth, which is a good generator for 33edo's theoretical framework as 33 is the first edo to really approach 53edo's buzzard temperament. Capable of profound darkness with the 13/11 and flat 3/2, much like pentagoth temperament, as well as the 14/9. Unfortunately lacking such strong consonance as the other tunings on this list. 5:3:1 diasem and 5:2:1 diamech are the best scales to begin understanding this tuning, but varying adjustments should be made and mastery requires a level of intuition that I don't yet possess.

I should now be able to think of a melody, decide which tuning is most appropriate, and leave it be as I move on to writing the rest of the song. The better and more fully that a passage is written, the harder it is to retune, and the less I have to gain from doing so. I have bigger plans for my music now and I need to be more efficient.

Ramadan starts tonight. It only makes sense to stop indulging my monomaniacal obsession with finding the perfect way to tune my lattice. My tuning experimentation should be limited to xenofifth edos, far enough abstracted from this to be considered a different category, and still lacking in appropriate musical representation.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part III: Poem 68.

〽 Koicha ni ha temae wo sutete hitosuji ni fuku-no-kagen to iki wo chirasu na

[濃茶には手前を捨て一筋に 服の加減と息を散らすな].

“When making koicha, throw away the temae, and proceed straightforwardly: don’t allow worries over the results to disturb your breathing.”

According to Rikyū, in the small room, the focus of the gathering should be wholly on the tea -- on the bowl of koicha¹. So this poem directs the beginner’s attention toward the act of preparing that bowl of tea. The kami-no-ku [上の句] tells the host how he should proceed, while the shimo-no-ku [下の句] cautions him to avoid falling into doubt over his competency -- since such thoughts, at this time, will only distract his attention, and invariably result in a less than satisfying experience for all.

Temae wo sutete [手前を捨てて] means that the temae should be cast off or thrown away. In other words, the host’s focus should not be on the perfect execution of each move. Rather, he should concentrate exclusively on preparing a delicious bowl of koicha -- which, as we have been told before², means the resulting tea will be hot, and without either foam or lumps³.

Hitosuji ni [一筋に] means to do something straightforwardly, with a singleness of purpose; approach it wholeheartedly (and without allowing any superfluous concerns to distract one from one’s purpose).

Fuku-no-kagen [服の加減] means (a desire to) adjust the portion (in other words, thinking about things like adding more water because, after blending, the host feels that the tea is too thick; or stressing out because the tea seems too thin).

Iki [息] means one’s breath (which was considered to either control, or be a manifestation of, one’s mental state -- the host’s breathing rate underpins the tempo of his temae).

...Wo chirasu na [を散らすな] means (these things) should not be allowed to break or disturb (one’s train of thought or action),

In other words, the shimo-no-ku warns us to guard against allowing our apprehensions (as a beginner) to impact our actions (so the host breaks his tempo, and his temae looses its balance).

Jōō’s original version, as preserved in the Matsu-ya manuscript, replaces chirasu na [散らすな] (not become dissipated or distracted) with the stronger verb korosu na [殺すな] (not become stifled or smothered). Ultimately, however, the meaning is very similar. The evidence from the block-printed version (which was purportedly based on a Rikyū manuscript dated Tenshō 8, mōshun [天正八年、孟春], “in the early spring” of 1580) suggests that this change in wording might possibly be ascribed to Rikyū⁴.

The Sekishū version of the poem (which Katagiri Sadamasa is supposed to have discovered during his decade-long research into Jōō’s original teachings⁵), is somewhat more problematic.

〽 koicha ni ha temae wo sutete hitosuji ni fuku-no-kagen to kokoro chirasu na

[濃茶には手前をすてゝ一筋に 服の加減とこころ散らすな].

“When making koicha, throw away the temae, and proceed straightforwardly: don’t allow worries over the results to disturb your mind.”

In addition to the change of the final verb from korosu [殺す] to the gentler chirasu [散らす], this version also replaces iki [息], breath or breathing, with kokoro [こころ = 心], mind. While this latter modification is certainly interesting (and, indeed, most valid), it seems to reflect the Edo period’s focus on the philosophical aspect of chanoyu. Coupled with the other modification (which is otherwise known only from Rikyū-related manuscripts, not Jōō’s), and the fact that Sadamasa did not reveal his source(s) for Jōō’s teachings⁶, it is possible to entertain doubts about the correctness of the attribution to Jōō.

_________________________

¹This in contrast to the idea of the larger rooms, where the utensils also become important. In the wabi setting -- which is the setting that these poems were intended to address -- all of the utensils should be dispensable and easily replaced, and so the only concern that the host and guests should have is over their functionality, their suitability to their purpose.

²Cf., Poem 54:

〽 Koicha ni ha yu kagen atsuku fuku ha nao awa naki-yō ni katamari mo naku

[濃茶には湯加減熱く服は尙 泡無き樣にカタマリも無く].

“With respect to koicha, the water should be hot, and the portion free of foam; and also there should be no katamari.”

The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/766705175959388160/the-chanoyu-hyaku-shu-%E8%8C%B6%E6%B9%AF%E7%99%BE%E9%A6%96-part-iii-poem-54

³The host has less control over the actual taste of the matcha, since this is what it is. However, a subtle difference can be achieved by adjusting the amount of water added to the tea: some blends taste better when made thicker, some when a little thinner. This is why it is important for the host to cultivate a taste and liking for koicha (something that many people today never really gain, to the detriment of their gatherings*).

When preparing tea -- both koicha and usucha -- Jōō added water twice†. Rikyū, however, believed that it was critical for the time between the matcha being put into the chawan and the chawan being lifted to the guest’s lips be kept to the absolute minimum. Thus he added water to the chawan only once.

Adding water twice seems “easier” to the beginner (because it gives him a second chance to get the amount of water just right). But with a little practice, it is not really any more difficult to follow Rikyū’s way‡. ___________ *It is unfortunate that, in the present day, many people have come to consider koicha a “necessary evil” that must be endured so that everyone can enjoy the delicious food, and sweets, congeniality, and the appreciation of fine and costly antique utensils that (they feel) are the real raison d'être for the chakai. But, honestly, if someone hates the taste of koicha that much, then it might be best for them to spend their time and energy (and money) on some other activity -- and it is the realization of this that is, at least in part, responsible for the decline in chanoyu in Japan today. If you don’t like koicha, there are countless other, and more satisfying, ways to enjoy life!

†Whether he was serving koicha or usucha, Jōō’s procedure was to close the kama during the chasen-tōshi, and so add fully boiling water to the tea at first. Then, after blending the tea for a few moments, he would open the mizusashi, add a hishaku of cold water to the kama, and then add a little more hot water to the chawan. After finishing the blending or whisking of the tea (Jōō only whisked the usucha during this second stage), the bowl was presented to the guest. Imai Sōkyū followed this way of doing things, which is how Jōō’s method for preparing koicha made its way into the modern temae (Sen no Shōan and his son Sōtan having been disciples of Sōkyū).

But whether he was serving koicha or usucha, Jōō always prepared the tea in individual portions (so, at a gathering for 5 people he prepared a total of up to 15 bowls of tea -- which is why he preferred to use an extremely large mizu-koboshi). Sōkyū, however, preferred serving koicha as suicha [吸い茶] -- meaning one large bowl of tea was shared by everyone -- as a way to reduce the amount of waste water that accumulated over the course of the goza (meaning that smaller koboshi cold be used).

‡While Jōō served individual bowls of both koicha and usucha to every guest (which was fine enough when the guest list consisted of wealthy merchants who could put their affairs off for the several hours that such a chakai would demand -- this is why the most usual time for tea was evening, after the end of the business day, followed by mid-morning, when the master was not expected to arrive at the office until around noon), Rikyū served the shōkyaku an individual bowl of koicha, while doubling up on the other guests, so as to reduce the amount of time needed (after 1582, Rikyū’s most frequent guests were members of Hideyoshi’s court, all extremely busy men whose work-day did not enjoy the regularity of a merchant’s).

Nevertheless, there is a world of difference between knowing how to make one or two portions of koicha, versus knowing how to make a triple, or quintuple (or even larger) portion. If the host cannot prepare the koicha confidently, this almost guarantees that it will not be its most delicious, so it becomes a vicious cycle of poorly-made tea resulting in an increasing dislike for koicha.

⁴The version of the poem in the block-printed edition is identical to that found in Hosokawa Sansai’s Kyūshū manuscript. But whether the significance of this is that Sansai simply replicated Rikyū’s version (as might be expected), or because the editors of the block-printed edition used Sansai’s version as their reference source, is less than clear.

⁵Given the confusion between the teachings of the Sen family (who stressed that they were Rikyū’s legitimate heirs -- despite the fact that they represented the machi-shū style that derived from the teachings of Imai Sōkyū*) and the counter-assertions of those daimyō who possessed densho written by Rikyū (which not infrequently contradicted the Sen family’s teachings), Sekishū decided that, since Rikyū was supposed to have been Jōō’s principal disciple (according to Kanamori Sōwa’s largely self-invented writings on the “history” of chanoyu in Japan†), the best way to clarify matters was to return to the original source -- in other words, to “rediscover” the teachings of Jōō‡.

On this project Katagiri Sadamasa spent the last decade or so of his life**. ___________ *And, to a lesser extent, those teachings as they were interpreted by Fufura Sōshitsu.

Oribe seems to have made something of a practice of answering questions from the host and other guests during the usucha section of gatherings that he attended in the years after Rikyū’s (and Imai Sōkyū’s) death; but it appears (from transcripts of these chakai) that he did not voluntarily divulge any of Rikyū’s teachings, only responding specifically to matters that were asked about by his interlocutors. The result was that this modified version of Sōkyū’s approach to chanoyu ultimately became the foundation of the Sen family’s “machi-shū chanoyu.”

†Which completely ignored any sort of Korean influence on, or relationship with, chanoyu, positing some sort of direct connection with China, while simultaneously declaring that chanoyu was a wholly Japanese cultural creation. (This became the foundational argument behind the Tokugawa bakufu’s insistence that chanoyu, of an appropriate level of formality, become part of every official interaction between representatives of the bakufu and the daimyō and leading merchants -- on the theory that money spent on tea utensils was money that could not be spent on weapons and insurrection).

‡Because an understanding of gokushin tea had been lost due to the overwhelming reach of the machi-shū approach, and because Jōō’s association with the Shino family (and the important influence of their kō-kai [香會] on Jōō’s early cha-kai [茶會]) had been downplayed (or overlooked entirely -- this was the Edo period, after all, when each of the arts was compartmentalized, and any blurring of the lines that separated them from each other was denounced and ignored), Sekishū and his contemporaries had been lead to understand a simplistic form of chanoyu evolution that, in fact, never existed. Yet they based their conclusions on that understanding.

**Though what he uncovered seems to have been an amalgam of authentic Jōō material mixed with things that are often so outrageous that it is difficult to believe that they are authentic -- or, conversely, that (if they are authentic) Jōō had any place in the evolution of chanoyu at all. At least some of this can be blamed on Sekishū’s method of acquiring Jōō’s writings (since it seems that he rewarded people who contributed documents to his archive liberally, so his reliance on a system of commissioners and agents to initiate inquiries within a community that was not only inherently antagonistic to the daimyō and what they represented, but also focused on the accumulation of wealth, meant the process itself encouraged corruption and fraud...sometimes even resulting in fabricated machi-shū manuscripts occasionally being passed off as Jōō’s authentic writings, and so making their way into Sekishū’s archive).

⁶Using his “influence” as one of the most powerful daimyō of his day, Katagiri Sadamasa “compelled” certain -- albeit unnamed (in his reference notes*) -- machi-shū chajin to send their Jōō manuscripts to his mansion in Edo for his inspection and review. Possibly fearing that they would not get them back, it is likely that at least some of the documents submitted to Sekishū’s office were recopied (with the facsimile copies sent to Edo -- we must recall that copies, in that period, were made not only to reproduce the text, but also replicate the handwriting of the original, often so carefully that the copy was virtually indistinguishable from the original), so it is possible that modifications made their way in based on contemporary versions of the poems (to, for example, restore sections that were rendered unreadable because of poor preservation of the original). ___________ *Perhaps Sadamasa considered these townsmen to be insignificant as individuals, and so unworthy of being named as a source. But his lack of documentation prevents us from being unable to compare his version with an original source (thus both hiding the identity of that source, and preventing later scholars from knowing where they might look for additional archived collections of Jōō‘s writings). Even today, manuscripts of this sort occasionally come to light among the sheaths of old papers found in abandoned buildings that are being torn down so the land can be used for modern construction projects. There are still several shops in the Teramachi shijō-agaru area that sell documents (mostly of unknown provenance, to be sure) -- some even dating back to the Heian period -- that were recovered in this way.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator.

To contribute, please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

0 notes

Photo

Kirawus: Hanabi(fireworks)~

In those modifications Noda does to volumes, aside from Kadokura being a Koya pilgrim on stilts, Ushiyama&Toni's Komusos and Ogata’s terrifying father-son puppet show…Kirawus-nispa is now made a peddler too as a firework salesman in Sapporo.

The signs on his table read Fireworks[花火, hanabi written RtoL] and Tamaya Fireworks[玊や花火]

Theres this practice of shouting Tamaya and Kagiya when launching fireworks. Its an old custom that was derived from names of two fireworks makers of Edo era. Some fireworks brands do use these in the names

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

“I’m curious about the modifications you made to edo tensei.” Because of course, he’s trying to figure out what made him immortal.

@uchiha-madara

He smiles slyly at them, as he holds a single black piece that is supposed to represent Madara between his thumb and index finger, "You really want to hear the long boring medical procedure to make you as you are? I don't mean to sound arrogant, but are you well read of the medical arts? I'm not going to say that it was easy since it did have it's challenges."

"You asking about my modifications, I presume that you and the Second Hokage weren't close enough to even consider sharing such possible medical information?"

1 note

·

View note

Text

History and Facts of Sushi

What is Sushi?

Sushi is a meal that claimed the appreciation of many people across the world. It is a Japanese recipe which is made of vinegared rice and is topped with other ingredients like vegetables, fruits, sugar, salt, sea food etc. This recipe falls into the category of both appetizer as well as main dish. It tastes good when served cold.

History of sushi

Before we put all our sushi onto a sushi platter, we must fish learn the history of the dish. The simple dish has got an interesting tale of evolution. The word sushi is derived from antiquated grammatical form and its literal meaning is “sour-tasting”. The dish has got an overall sour taste and hence the name follows. This dish has originated from South East Asia in the eighth century. The sea food is the staple food of Japan. Today it is called by the name Narezushi which means salted fish.

The salted fish is stored in fermented rice for a span of few months. The fish is prevented from getting spoiled by the process named lacto-fermentation of rice. Lactic acid bacilli would be released during the fermentation process of cooked rice. Salted fish when placed in fermented rice, it would be preserved by pickling process. Prior to the fish consumption, the rice would be discarded. The Japanese used to treat this early recipe of sushi as the primary source of protein. Narezushi, as of now, exists as a regional specialty as funa-zushi in Shiga Prefecture.

During the period of 14th to 16th century, the Muromachi period, the addition of vinegar to the preparation of Narezushi has started. The purpose of adding vinegar is to improve the taste in terms of sourness of rice and for a high degree of preservation by significantly increasing the longevity of the dish. This also resulted in shortened and gradually minimal or zero fermentation process making the dish ready to eat instantly.

The early sushi dish saw more popularity in Osaka. Over centuries, it transformed into hako-zushi or oshi-zushi. The modification in this recipe is that both rice and seafood were pressed together into typical bamboo molds during the preparation.

The Origins of Sushi

During the period of 17th to 19th century i.e. Edo period, another drastic change has occurred in the recipe. It initiated the serving of fresh fish over nori and vinegared rice (the sea weed which is collected with bamboo nets that are submerged), which is the current style of serving this dish. Today’s Nigirizushi style was prevalent in Edo (present Tokyo) during 1820s. Usage of vinegar made the dish to be eaten immediately without any need to wait for months.

The origin of Nigirizushi is a story related to the chef of Ryogoku, Tokyo. The chef named Hanaya Yohei (1799 – 1858) has devised the perfect technique of preparation of this dish at his shop in 1824. This dish was named as Edomae zushi. This preparation used the freshly caught fish from the Tokyo Bay. Even today, Edomae nigirizushi is the term used to represent quality sushi irrespective of the ingredients origin.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Tattooing is the most misunderstood art form in Japan today. Looked down upon for centuries and rarely discussed in social circles, people with tattoos are outcasts in this country, banned from most public spaces such as beaches, bathhouses, and even gyms.

Tattoos have an extensive history in Japan, and to truly understand the stigma behind them it is essential to be aware of their significance. The first records of tattoos were found in 5000 B.C., during the Jomon period, on clay figurines depicting designs on the face and body. The first written record of tattoos in Japan was from 300 A.D., found in the text History of the Chinese Dynasties. In this text, Japanese men would tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with tattoos which became a normal part of their society; however, a shift began in the Kofun period between 300 and 600 A.D where tattoos took on a more negative light.

In this period criminals began to be marked with tattoos, similar to the Roman Empire where slaves were marked with descriptive phrases of the crime they had committed. This stigma towards body modification only worsened: by the 8th century Japanese rulers had adopted many of the Chinese attitudes and cultures. As tattoos fell into decline, the first record of them being used explicitly as a punishment was 720 A.D., where criminals were tattooed on the forehead so people could see that they had committed a crime. These markings were reserved for only the most serious crimes. People bearing tattoos were ostracized from their families and were rejected by society as a whole. Whereafter tattoos experienced somewhat of popularization in the Edo period through the Chinese novel Suikoden, which depicted heroic scenes with bodies decorated with tattoos.

This novel became so popular, people began to get these tattoos as physical rendering in the form of paintings. This practice eventually evolved into what we know today as irezumior Japanese tattooing. This practice would have a monumental impact, with many woodblock artists converting their woodblock printing tools to begin creating art on the skin. Tattoos became a status symbol during this time; it is said that wealthy merchants were prohibited from wearing and displaying their wealth through jewelry, so instead they decorated their entire bodies with tattoos to show their riches.

0 notes