#Easterlin Paradox

Text

The Rich, the Poor and Bulgaria! Money Really Can Buy You Happiness

— Published: December 16th, 2010 | Wednesday 16th August, 2023 | Christmas Specials | Comparing Countries

THE notion that money can't buy happiness is popular, especially among Europeans who believe that growth-oriented free-market economies have got it wrong. They drew comfort from the work of Richard Easterlin, Professor of Economics at the University of Southern California, who trawled through the data in the 1970s and observed only a loose correlation between money and happiness. Although income and well-being were closely correlated within countries, there seemed to be little relationship between the two when measured over time or between countries. This became known as the “Easterlin paradox”. Mr Easterlin suggested that well-being depended not on absolute, but on relative, income: people feel miserable not because they are poor, but because they are at the bottom of the particular pile in which they find themselves.

But more recent work—especially by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers of the University of Pennsylvania—suggests that while the evidence for a correlation between income and happiness over time remains weak, that for a correlation between countries is strong. According to Mr Wolfers, the correlation was unclear in the past because of a paucity of data. There is, he says, “a tendency to confuse absence of evidence for a proposition as evidence of its absence”.

There are now data on the effect of income on well-being almost everywhere in the world. In some countries (South Africa and Russia, for instance) the correlation is closer than in others (like Britain and Japan) but it is visible everywhere.

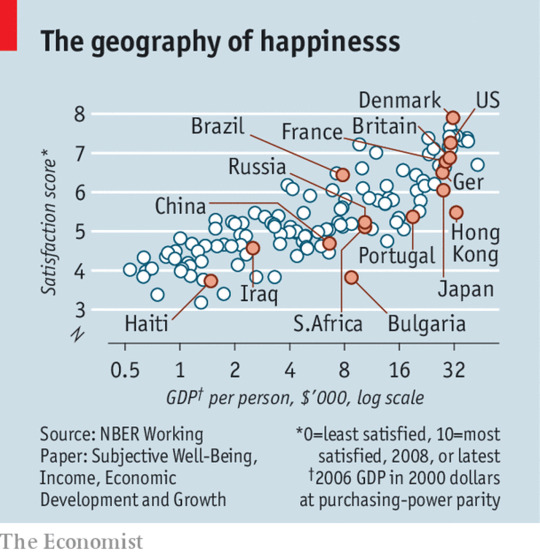

The variation in life satisfaction between countries is huge (see chart). Countries at the top of the league (all of them developed) score up to eight out of ten; countries at the bottom (mostly African, but with Haiti and Iraq putting in a sad, but not surprising, appearance) score as low as three.

Although richer countries are clearly happier, the correlation is not perfect, which suggests that other, presumably cultural, factors are at work. Western Europeans and North Americans bunch pretty closely together, though there are some anomalies, such as the surprisingly gloomy Portuguese. Asians tend to be somewhat less happy than their income would suggest, and Scandinavians a little more so. Hong Kong and Denmark, for instance, have similar income per person, at purchasing-power parity; but Hong Kong's average life satisfaction is 5.5 on a 10-point scale, and Denmark's is 8. Latin Americans are cheerful, the ex-Soviet Union spectacularly miserable, and the saddest place in the world, relative to its income per person, is Bulgaria.

— This article appeared in the Christmas Specials section of the print edition under the headline "The Rich, the Poor and Bulgaria"

#The Economist#The Rich | The Poor and Bulgaria#Money | Happiness#Europeans#Richard Easterlin#Professor of Economics | University of Southern California#Easterlin Paradox#Betsey Stevenson | Justin Wolfers | University of Pennsylvania#South Africa 🇿🇦 and Russia 🇷🇺#Britain 🇬🇧 | Japan 🇯🇵#Haiti 🇭🇹 Iraq 🇮🇶#Portugal 🇵🇹#Hong Kong 🇭🇰 | Denmark 🇩🇰#Ex-Soviet Union#Christmas Specials | Comparing Countries#Bulgaria 🇧🇬

1 note

·

View note

Text

When burdened by the tangible angst and unease around the future of our planet, a term like “climate anxiety” can seem insufficient. ... In reality, seeing the mounting global disasters and learning of evidence-based projections of our changing world comes with a heavy emotional gravity. ...

Perhaps the better question to ask is, “How can we transform dread into something more workable?” said Easterlin. “You’ll hear this over and over again: Action is one of the antidotes to dread.” Research seems to support this. A study published this month found that, among teenagers and young adults experiencing climate distress, those who reported making even small life changes or decisions for climate reasons—like reducing single-use plastic consumption, opting to commute via bike instead of car, or participating in political activism—still experienced anger and frustration but were also more likely to feel positive emotions like hope. ...

Participating in even small actions and thinking about where and how you can be effective can move dread into something positive and hopeful, said Easterlin. It can pull you out of that forward-looking dread and into the current moment, where you can see yourself acting capably and with impact. It takes you out of the role of a passive victim and into a position of agency and strength. ...

Like many emotions, dread is contagious, said Olsson. Whether we express it in person or online, it “catches” and amplifies—which can, paradoxically, help bring more attention and awareness to the issue at hand and possibly bring like-minded people together. This helps us all establish what we communally think is undesirable or should be avoided.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It is often said that money can't buy happiness, and there might be some truth in those words. Even though it is generally believed that wealthier nations are among the happiest on Earth, a recent survey found that low income individuals living in small-scale communities often report feeling just as happy, if not more so, than their high-income counterparts.

Notably, these findings go against the belief that it is often the richest countries on Earth that are the happiest. This could be explained partially by the Easterlin paradox, which explains that an increase in societal wealth does not always correspond to an increase in societal happiness over time. It is also possible that, historically, researchers have placed too much emphasis on the correlation between wealth and happiness, which has caused the two factors to appear more closely linked than they actually are.

In the end, there may be something even more valuable than money when it comes to gauging happiness, and that is the vital role that social relationships play in many people's lives.

“As deeply social animals, humans are tightly attuned to the security of their position within society, including the support they can count on from others,” writes Galbraith. “This primarily comes from the strength of interpersonal relationships and an assessment of one’s social standing. But social relations do not necessarily go together with wealth. What’s more, although the communities we studied have little money, they are not poor in the sense of lacking basic necessities, and many of the people in these societies spend their days in close contact with natural surroundings, something many studies suggest benefits well-being.”"

source: https://mymodernmet.com/low-income-societies-happier/?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Title: Understanding the Easterlin Paradox: The Limits of Income and Happiness

The Easterlin Paradox, named after economist Richard Easterlin, delves into the intricate relationship between income and happiness, challenging the conventional belief that higher income directly correlates with greater happiness. This paradox has sparked significant debate and research, shedding light on the complex nature of human well-being and satisfaction.

At its core, the Easterlin Paradox posits that while within a certain range, increased income is indeed associated with higher levels of happiness, beyond a certain threshold, additional income does not lead to a corresponding increase in happiness. This concept challenges the traditional economic assumption that more wealth equates to more happiness, highlighting the nuanced dynamics at play in subjective well-being.

One of the key reasons behind the Easterlin Paradox is the concept of adaptation or the hedonic treadmill. This phenomenon suggests that individuals tend to adapt to changes in their circumstances, including changes in income, relatively quickly. As a result, the initial boost in happiness from a salary raise, for example, may diminish over time as individuals adjust their expectations and aspirations to their new financial status.

Moreover, the pursuit of material wealth often comes with inherent trade-offs and stressors. The relentless quest for higher income may lead to increased work hours, job-related stress, and a focus on material possessions rather than intrinsic sources of happiness such as relationships, personal growth, and leisure time. This shift in priorities can contribute to a diminished sense of well-being despite financial success.

Another aspect contributing to the Easterlin Paradox is social comparison. As individuals climb the income ladder, they may engage in upward social comparisons, benchmarking their wealth and status against others in their social circles. This comparison can lead to feelings of inadequacy or a perpetual desire for more, undermining the potential happiness derived from increased income.

Additionally, research in psychology and behavioral economics has highlighted the importance of non-material factors in subjective well-being. Factors such as meaningful relationships, a sense of purpose, autonomy, and self-acceptance play significant roles in overall life satisfaction, often independent of financial wealth. Thus, the Easterlin Paradox underscores the limitations of equating happiness solely with economic indicators.

Furthermore, cultural and societal factors influence how individuals perceive and experience happiness. Cultural norms, values, and expectations shape individuals' definitions of a fulfilling life, with some cultures prioritizing collective well-being, social connections, and leisure over material wealth.

In conclusion, the Easterlin Paradox provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between income and happiness. While higher income can enhance well-being up to a certain point by meeting basic needs and providing security, beyond that threshold, other factors such as adaptation, social comparison, and non-material aspects of life become more significant determinants of happiness. Understanding these nuances is crucial for fostering holistic well-being and designing policies that promote genuine happiness and fulfillment in society.

0 notes

Text

Aquinas & the Market: Toward a Humane Economy

Aquinas & the Market: Toward a Humane Economy

View On WordPress

#Angelic doctor#Aquinas#Beatitude#Cardinal Virtues#Catholic Social Teaching#Catholic Social thought#Catholicism#Charity#Choice#Conservative#Contemplation#Control#Easterlin Paradox#Economics#Efficiency#Eudaimonia#Faith#Flourishing#Freedom#Gift#Giving#Grace#Happiness#Hope#Instrumental#Kirby Laing Centre#Liberal#Love#Mary Hirschfield#Nature

0 notes

Text

The Art of the Good Life by Rolf Dobelli; Quotes

Is it better to actively seek happiness or to avoid unhappiness?

Living a good life has a lot to do with interpreting facts in a constructive way.

That money can’t buy happiness is a truism, and I’d certainly advise you not to get worked into a lather over incremental differences in price. If a beer’s two dollars more expensive than usual or two dollars cheaper, it elicits no emotional response in me whatsoever. I save my energy rather than my money. After all, the value of my stock portfolio fluctuates every minute by significantly more than two dollars, and if the Dow Jones falls by a thousandth of a percent, that doesn’t faze me either. Try it for yourself. Come up with a similar number, a modest sum to which you’re completely indifferent—money you consider not so much money as white noise. You don’t lose anything by adopting that attitude, and certainly not your inner poise.

The most common misunderstanding I encounter is that the good life is a stable state or condition. Wrong. The good life is only achieved through constant readjustment.

As the American general—and later president—Dwight Eisenhower said, “Plans are nothing. Planning is everything.” It’s not about having a fixed plan, it’s about repeated re-planning—an ongoing process.

The truth is that you begin with one set-up and then constantly adjust it. The more complicated the world becomes, the less important your starting point is. So don’t invest all your resources into the perfect set-up—at work or in your personal life. Instead, practice the art of correction by revising the things that aren’t quite working—swiftly and without feeling guilty.

First: constantly having to make new decisions situation by situation saps your willpower. Decision fatigue is the technical term for this. A brain exhausted by decision-making will plump for the most convenient option, which more often than not is also the worst one. This is why pledges make so much sense. Once you’ve pledged something, you don’t then have to weigh up the pros and cons each and every time you’re faced with a decision. It’s already been made for you, saving you mental energy.

The second reason inflexibility is so valuable has to do with reputation. By being consistent on certain topics, you signal where you stand and establish the areas where there’s no room for negotiation. You communicate self-mastery, making yourself less vulnerable to attack.

So say good-bye to the cult of flexibility. Flexibility makes you unhappy and tired, and it distracts you from your goals. Chain yourself to your pledges. Uncompromisingly. It’s easier to stick to your pledges 100 percent of the time rather than 99 percent.

Very few people simply accept reality and analyze their own flight recorders. This requires precisely two things: a) radical acceptance and b) black box thinking. First one, then the other.

“Nothing is more fatiguing nor, in the long run, more exasperating than the daily effort to believe things which daily become more incredible. To be done with this effort is an indispensable condition of sure and lasting happiness,” wrote mathematician and Nobel Prize winner Bertrand Russell.

Accepting reality is easy when you like what you see, but you’ve got to accept it even when you don’t—especially when you don’t.

By themselves, radical acceptance and black box thinking are not enough. You’ve got to rectify your mistakes. Get future-proofing. As Warren Buffett’s business partner Charlie Munger has observed, “If you won’t attack a problem while it’s solvable and wait until it’s unfixable, you can argue that you’re so damn foolish that you deserve the problem.” Don’t wait for the consequences to unfold. “If you don’t deal with reality, then reality will deal with you,” warns author Alex Haley.

A basic rule of the good life is as follows: if it doesn’t genuinely contribute something, you can do without it. And that is doubly true for technology. Next time, try switching on your brain instead of reaching for the nearest gadget.

“There are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no bold old pilots.”

Pros win points; amateurs lose points. This means that if you’re playing against an amateur, your best option is to focus on not making any mistakes. Play conservatively, and keep the ball in play as long as possible. Unless your opponent is deliberately playing equally conservatively, he or she will make more mistakes than you do. In amateur tennis, matches aren’t won—they’re lost.

disease, disabilities, divorce. However, countless studies have shown that the impact of these factors dissipates more quickly than we imagine.

It’s not what you add that enriches your life—it’s what you omit.

Because our emotions are so unreliable, a good rule of thumb is to take them less seriously—especially the negative ones. The Greek philosophers called this ability to block things out ataraxia, a term meaning serenity, peace of mind, equanimity, composure or imperturbability. A master of ataraxia will maintain his or her poise despite the buffets of fate. One level higher is apatheia, the total eradication of feeling (also attempted by the ancient Greeks). Both—ataraxia and apatheia—are ideals virtually impossible to attain, but don’t worry: I’m not asking you to try. I do, however, believe we need to cultivate a new relationship with our inner voices, one distanced, skeptical and playful.

So take other people’s feelings very seriously, but not your own. Let them flit through you—they’ll come and go anyway, just as they please.

People are respected because they deliver on their promises, not because they let us eavesdrop on their inner monologs.

Two thousand years ago, the Roman philosopher Seneca wrote: “All those who summon you to themselves, turn you away from your own self.” So give the five-second no a trial run. It’s one of the best rules of thumb for a good life.

It’s called the focusing illusion. “Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it,” as Daniel Kahneman explains. The more narrowly we focus on a particular aspect of our lives, the greater its apparent influence.

Take the longest possible view of your life. Realize that the things that seemed so important in the moment have shrunk to the size of dots—dots that barely affect the overall picture. A good life is only attainable if you take the occasional peek through a wide-angle lens.

By focusing on trivialities, you’re wasting your good life.

As you can see, if it’s the good life you’re after then it’s advisable to show restraint about what you buy. That said, there is a class of “goods” whose enjoyment is not diminished by the focusing illusion: experiences.

Material progress was not reflected in increased life satisfaction. This revelation has been termed the Easterlin paradox: once basic needs have been met, incremental financial gain contributes nothing to happiness.

Money is relative. Not just in comparison to others, but in comparison to your past.

Buffett’s life motto: “Know your circle of competence, and stick within it. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.” Charlie Munger adds: “Each of you will have to figure out where your talent lies. And you’ll have to use your advantages. But if you try to succeed in what you’re worst at, you’re going to have a very lousy career. I can almost guarantee it.”

“Expect anything worthwhile to take a really long time”

What matters is that you’re far above average in at least one area—ideally, the best in the world. Once that’s sorted, you’ll have a solid basis for a good life. A single outstanding skill trumps a thousand mediocre ones. Every hour invested into your circle of competence is worth a thousand spent elsewhere.

“You don’t have to be brilliant,” as Charlie Munger says, “only a little bit wiser than the other guys, on average, for a long, long time.”

“One of the symptoms of approaching nervous break-down is the belief that one’s work is terribly important,” wrote Bertrand Russell. This is precisely the danger of a calling: that you take yourself and your work too seriously. If, like John Kennedy Toole, you pin everything on the fulfilment of your supposed vocation, you cannot live a good life. If Toole had viewed his writing not as his only possible calling but simply as a craft for which he happened to have a special knack, he would probably not have ended up as he did. You can pursue a craft with love, of course, and even with a touch of obsession, but your focus should always be on the activity, the work, the input—not on the success, the result, the output.

So, what to do? Don’t listen to your inner voice. A calling is nothing but a job you’d like to have. In the Romantic sense it doesn’t exist; there is only talent and preference. Build on the skills you actually have, not on some putative sense of vocation. Luckily, the skills we’ve mastered are often the things we enjoy doing. One important aside: other people have also got to value your talents. You’ve got to put food on the table somehow. As the English philosopher John Gray put it: “Few people are as unhappy as those with a talent no one cares about.”

So liberate yourself. Here’s three reasons why you should. First, you’ll be spared the emotional roller coaster. In the long run, you can’t manage your reputation perfectly anyway. Warren Buffett cites Gianni Agnelli, the former boss of Fiat: “When you get old, you have the reputation you deserve.” You can fool other people for a while, but not a lifetime. Second, concentrating on prestige and reputation distorts our perception of what makes us truly happy. And third, it stresses us out. It’s detrimental to the good life.

That’s why one of my golden rules for leading a good life is as follows: “Avoid situations in which you have to change other people.”

Without memory, the experience is perceived as entirely valueless. This is surprising, and it makes no sense. Surely it’s better to experience something wonderful than not—regardless of whether you remember it. After all, in the moment you’ll be having a fabulous time! And once we’re dead, you and I will forget everything anyway—because there’ll no longer be any “you” or any “I.” If death is going to erase your memories, how important is it to schlep them with you until your very final moment?

So don’t be surprised when somebody else judges you “incorrectly.” You do the same yourself. A realistic self-image can only be gleaned from someone who’s known you well for years and who’s not afraid to be honest—your partner or an old friend. Even better, keep a diary and dip back into it every now and again. You’ll be amazed at the things you used to write. Part of the good life is seeing yourself as realistically as possible—contradictions, shortcomings, dark sides and all. If you see yourself realistically, you’ve got a much better chance of becoming who you want to be.

I’m sure you recognize the sentiment: “When I’m on my deathbed, looking back on my life…” A magnificently lofty idea, but rather nonsensical in practice. For a start, almost no one is that lucid when they’re on their deathbed. The three main doors into the afterlife are heart attack, stroke and cancer. In the first two cases, you won’t have time for philosophical reflection. In most cases of cancer, you’ll be so stuffed to the gunnels with painkillers that you won’t be able to think straight. Nor do those afflicted with dementia or Alzheimer’s achieve any new insights on their deathbeds. And even if you do have the time and wherewithal in your final moments to reminisce, your memories won’t (as we saw in the previous three chapters) correspond fully to reality. Your remembering self produces systematic errors. It tells tall tales.

“If you find yourself in a hole, stop digging.”

Not getting bogged down in self-pity is a golden rule of mental health. Accept the fact that life isn’t perfect—yours or anyone else’s. As the Roman philosopher Seneca said, “Things will get thrown at you and things will hit you. Life’s no soft affair.” What point is there in “being unhappy, just because once you were unhappy”? If you can do something to mitigate the current problems in your life, then do it. If you can’t, then put up with the situation. Complaining is a waste of time, and self-pity is doubly counterproductive: first, you’re doing nothing to overcome your unhappiness; and two, you’re adding to your original unhappiness the further misery of being self-destructive. Or, to quote Charlie Munger’s “iron prescription”: “Whenever you think that some situation or some person is ruining your life, it is actually you who are ruining your life… Feeling like a victim is a perfectly disastrous way to go through life.”

Plato and Aristotle both believed that people should be as temperate, courageous, just and prudent as possible.

The circle of dignity draws together your individual pledges and protects them from three forms of attack: a) better arguments; b) mortal danger; and c) deals with the Devil.

Is it worth the price? That’s the wrong question. By definition, things that are invaluable have no price. “If an individual has not discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live,” said Martin Luther King. Certainly not to live the good life.

If you don’t make it clear on the outside what you believe deep down, you gradually turn into a puppet. Other people exploit you for their own purposes, and sooner or later, you give up. You don’t fight any more. You don’t hold up to stresses. Your willpower atrophies. If you break on the outside, at some point you’ll break on the inside too.

Your circle of dignity, the protective wall that surrounds your pledges, can only be tested under fire. You might lay claim to high ideals, noble principles and distinctive preferences, but it’s not until you come to defend them that you will “cry with happiness,” to paraphrase Stockdale.

Say you’re in a meeting and somebody starts going for you, really getting vitriolic. Ask them to repeat what they’ve said word for word. You’ll soon see that, most of the time, your attacker will fold.

For most people, the circle of dignity is not a matter of life and death but a battle to maintain the upper hand. Make it as hard as possible for your assailants. Keep the reins in your hand as long as possible when it comes to the things you hold sacred. If you have to give up, then do so in a way that makes your opponent pay the highest practicable price for your capitulation. There’s tremendous power in this commitment. It’s one of the keys to a good life.

One: fetch a notebook and title it My Big Book of Worries. Set aside a fixed time to dedicate to your anxieties. In practical terms, this means reserving ten minutes a day to jot down everything that’s worrying you—no matter how justified, idiotic or vague. Once you’ve done so, the rest of the day will be relatively worry-free. Your brain knows its concerns have been recorded and not simply ignored. Do this every day, turning to a fresh page each time. You’ll realize, incidentally, that it’s always the same dozen or so worries tormenting you. At the weekend, read through the week’s notes and follow the advice of Bertrand Russell: “When you find yourself inclined to brood on anything, no matter what, the best plan always is to think about it even more than you naturally would, until at last its morbid fascination is worn off.” In practical terms, this means imagining the worst possible consequences and forcing yourself to think beyond them. You’ll discover that most concerns are overblown. The rest are genuine dangers, and those must be confronted. Two: take out insurance. Insurance policies are a marvelous invention. They’re among the most elegant worry-killers. Their true value is not the monetary pay-out when there’s a problem but the reduced anxiety beforehand. Three: focused work is the best therapy against brooding. Focused, fulfilling work is better than meditation. It’s a better distraction than anything else. If you use these three strategies, you’ll have a real chance of living a carefree life—a good life. Then perhaps even in your younger years or, at least, in middle age, you’ll be able to chuckle over Mark Twain’s late-in-life insight: “I am an old man and have known a great many troubles, but most of them have never happened.”

The Greek and Roman philosophers known as the Stoics recommended the following trick to sweep away worry: determine what you can influence and what you can’t. Address the former. Don’t let the latter prey on your mind.

Not always feeling like you need to have an opinion calms the mind and makes you more relaxed—an ingredient vital to a good life.

First: accept the existence of fate. In Boethius’s day, people liked to personify fate as Fortuna, a goddess who turned the Wheel of Fortune, in which highs and lows were endlessly rotated. Those who played along, hoping to catch the wheel as it rose, had to accept that eventually they would come down once more. So don’t be too concerned about whether you’re ascending or descending. It could all be turned on its head.

Second: everything you own, value and love is ephemeral—your health, your partner, your children, your friends, your house, your money, your homeland, your reputation, your status. Don’t set your heart on those things. Relax, be glad if fate grants them to you, but always be aware that they are fleeting, fragile and temporary. The best attitude to have is that all of them are on loan to you, and may be taken away at any time. By death, if nothing else.

Third: if you, like Boethius, have lost many things or even everything, remember that the positive has outweighed the negative in your life (or you wouldn’t be complaining) and that all sweet things are tinged with bitterness. Whining is misplaced.

Four: what can’t be taken from you are your thoughts, your mental tools, the way you interpret bad luck, loss and setbacks. You can call this space your mental fortress—a piece of freedom that can never be assailed.

Stop comparing yourself to other people and you’ll enjoy an envy-free existence. Steer well clear of all comparisons. That’s the golden rule.

So wisdom isn’t identical with the accumulation of knowledge. Wisdom is a practical ability. It’s a measure of the skill with which we navigate life. Once you’ve come to realize that virtually all difficulties are easier to avoid than to solve, the following simple definition will be self-evident: “Wisdom is prevention.”

The fact is, life is hard. Problems rain down on all sides. Fate opens pitfalls beneath your feet and throws up barriers to block your path. You can’t change that. But if you know where danger lurks, you can ward it off. You can evade all sorts of obstacles. Einstein put it this way: “A clever person solves a problem. A wise person avoids it.”

Wisdom is prevention. It’s invisible, so you can’t show it off—but preening isn’t conducive to a good life anyway. You know that already.

if you want to help reduce suffering on the planet, donate money. Just money. Not time. Money. Don’t travel to conflict zones unless you’re an emergency doctor, bomb-disposal expert or diplomat. Many people fall for the volunteer’s folly—they believe there’s a point to voluntary work. In reality, it’s a waste. Your time is more meaningfully invested in your circle of competence, because it’s there that you’ll generate the most value per day. If you’re installing water pumps in the Sahara, you’re doing work that local well-diggers could carry out for a fraction of the cost. Plus, you’re taking work away from them. Let’s say you could dig one well per day as a volunteer. If you spent that day working at your office and used the money you earned to pay local well-diggers, by the end of the day you’d have a hundred new wells. Sure, volunteering makes you feel good, but it shouldn’t be about that. And that warm Good Samaritan glow is based on a fallacy. The first-rate specialists on site (Médecins Sans Frontières, the Red Cross, UNICEF, etc.) will put your donations to more effective use than you could yourself. So work hard and put your money in the hands of professionals.

you’re not responsible for the state of the world. It sounds harsh and unsympathetic, but it’s the truth. Nobel Prize winner in physics Richard Feynman was told much the same thing by John von Neumann, the brilliant mathematician and “father of computing”: “[John] von Neumann gave me an interesting idea: that you don’t have to be responsible for the world that you’re in. So I have developed a very powerful sense of social irresponsibility as a result of von Neumann’s advice. It’s made me a very happy man ever since.” What Feynman means by “social irresponsibility” is this: don’t feel bad for concentrating on your work instead of building hospitals in Africa. There’s no reason to feel guilty that you happen to be better off than a bombing victim in Aleppo—your situations could easily be reversed. Lead an upright, productive life, and don’t be a monster. Follow that advice and you’ll already be contributing to a better world. The upshot? Find a strategy to help you cope with global atrocities. It doesn’t have to be one I’ve suggested here, but it is important to have a plan. Otherwise getting through life will be tough. You’ll be constantly torn between the things that still have to be done, you’ll feel guilty—and ultimately you’ll accomplish nothing with that burden.

Four: be aware that focus cannot be divided. It’s not like time and money. The attention you’re giving your Facebook stream on your mobile phone is attention you’re taking away from the person sitting opposite. Five: act from a position of strength, not weakness. When people bring things to your attention unasked, you’re automatically in a position of weakness. Why should an advertiser, a journalist or a Facebook friend decide where you direct your focus? That Porsche advert, article about the latest Trump tweet or video clip of hilariously adorable puppies is probably not something that’s going to make you happy or move you forwards. Even without an Instagram account, the philosopher Epictetus came to a similar conclusion two thousand years ago: ‘If a person gave your body to any stranger he met on his way, you would certainly be angry. And do you feel no shame in handing over your own mind to be confused and mystified by anyone who happens to verbally attack you?’

What does focus have to do with happiness? Everything. “Your happiness is determined by how you allocate your attention,” wrote Paul Dolan. The same life events (positive or negative) can influence your happiness strongly, weakly or not at all—depending on how much attention you give them. Essentially, you always live where your focus is directed, no matter where the atoms of your body are located. Each moment comes only once. If you deliberately focus your attention, you’ll get more out of life. Be critical, strict and careful when it comes to your intake of information—no less critical, strict and careful than you are with your food or medication.

Avoid ideologies and dogmas at all cost—especially if you’re sympathetic to them. Ideologies are guaranteed to be wrong. They narrow your worldview and prompt you to make appalling decisions.

When you meet someone showing signs of a dogmatic infection, ask them this question: “Tell me what specific facts you’d need in order to give up your worldview.” If they don’t have an answer, keep that person at arm’s length. You should ask yourself the same question, for that matter, if you suspect you’ve strayed too far into dogma territory.

imagine you’re on a TV talk show with five other guests, all of whom hold the opposite conviction from yours. Only when you can argue their views at least as eloquently as your own will you truly have earned your opinion.

think independently, don’t be too faithful to the party line, and above all give dogmas a wide berth. The quicker you understand that you don’t understand the world, the better you’ll understand the world.

In several studies, Dan Gilbert, Timothy Wilson and their research colleagues have shown that mental subtraction increases happiness significantly more markedly than simply focusing on the positives. The Stoics figured this out two thousand years ago: instead of thinking about all the things you don’t yet have, consider how much you’d miss the things you do have if you didn’t have them any longer.

Speculation is more agreeable than realization. As long as you’re still weighing up your options, the risk of failure is nil; once you take action, however, that risk is always greater than zero. This is why reflection and commentary are so popular. If you’re simply thinking something over, you’ll never bump up against reality, which means you can never fail. Act, however, and suddenly failure is back on the cards—but you’ll gain new experiences. “Experience is what you get when you didn’t get what you wanted,” as the saying goes.

the next time you’re about to make an important decision, mull it over carefully—but only to the point of maximum deliberation. You’ll be surprised how quickly you reach it. Once you’re there, flick off your torch and switch on your floodlight. It’s as useful in the workplace as it is in the home, whether you’re investing in your career or in your love life.

No matter how extraordinary your accomplishments might be, the truth is that they would have happened without you. Your personal impact on the world is minute. It doesn’t matter how brilliant you are—as a businessperson, an academic, a CEO, a general or a president; in the great scheme of things you’re insignificant, unnecessary and interchangeable. The only place where you can really make a difference is in your own life. Focus on your own surroundings. You’ll soon see that getting to grips with that is ambitious enough. Why take it upon yourself to change the world? Spare yourself the disappointment.

Not believing too much in your own self-importance is one of the most valuable strategies for a good life.

The upshot? There is no just plan for the world. Part of the good life is to radically accept that. Focus on your garden—on your own everyday life—and you’ll find enough weeds to keep you busy. The things that happen to you across the course of your life, especially the more serious blows of fate, have little to do with whether you’re a good or a bad person. So accept unhappiness and misfortune with stoicism and calm. Treat incredible success and strokes of luck exactly the same.

“There’s an infinite number of winners,” Kevin Kelly has said, “as long as you’re not trying to win somebody else’s race.”

The upshot? Try to escape the arms race dynamic. It’s difficult to recognize, because each individual step seems reasonable when considered on its own. So retreat every so often from the field of battle and observe it from above. Don’t fall victim to the madness. An arms race is a succession of Pyrrhic victories, and your best bet is to steer clear. You’ll only find the good life where people aren’t fighting over it.

As Warren Buffett says, “It’s better to be approximately right than precisely wrong.”

Constantly distinguish between “I have to have it,” “I want to have it” and “I expect it.” The first phrase represents a necessity, the second a desire (a preference, a goal) and the third an expectation.

Seeing desires as musts will only make you a grumpy, unpleasant person to be around. And no matter how intelligent you are, it will make you act like an idiot. The sooner you can erase supposed necessities from your repertoire, the better.

A life without goals is a wasted life. Yet we mustn’t be shackled to them. Be aware that not all your desires will be satisfied, because so much lies beyond your control.

The Greek philosophers had a wonderful expression for the things we want: preferred indifferents (indifferent here in the sense of insignificant). So I might have a preference (e.g., I’d prefer a Porsche to a VW Golf), but ultimately it’s insignificant to my happiness.

Bearing Sturgeon’s law in mind will improve your life. It’s an excellent mental tool because it “allows” you to pass over most of what you see, hear or read without feeling guilty. The world is full of empty words, but you don’t need to listen. That said, don’t try to cleanse the world of nonsense. You won’t succeed. The world can stay irrational longer than you can stay sane. So concentrate on being selective, on the few valuable things, and leave everything else aside.

Recognize bullshit for what it is. Oh, and one other rule, which in my experience has proved well founded: if you’re not sure whether something is bullshit, it’s bullshit.

One: self-importance requires energy. If you think overly highly of yourself, you have to operate a transmitter and a radar simultaneously. On the one hand, you’re broadcasting your self-image out into the world; on the other, you’re permanently registering how your environment responds. Save yourself the effort. Switch off your transmitter and your radar, and focus on your work. In concrete terms, this means don’t be vain, don’t name-drop, and don’t brag about your amazing successes.

the more self-important you are, the more speedily you’ll fall for the self-serving bias. You’ll start doing things not to achieve a specific goal but to make yourself look good. You often see the self-serving bias among investors. They buy stocks in glamorous hotels or sexy tech companies—not because they’re solid investments but because they want to enhance their own image. On top of this, people who think highly of themselves tend to systematically overestimate their knowledge and abilities (this is termed overconfidence), leading to grave errors in decision-making.

If you stress your own importance, you do so at the expense of other people’s, because otherwise it would devalue your relative position. Once you’re successful, if not before, other people who are equally full of themselves will shit on you. Not a good life.

As you can see, your ego is more antagonist than friend.

Stay modest. You’ll improve your life by several orders of magnitude. Self-esteem is so easy that anyone can do it; modesty, on the other hand, may be tough, but at least it’s more compatible with reality. And it calms your emotional wave pool. Self-importance has developed into a malady of civilization. We’ve got our teeth into our egos like a dog into an old shoe. Let the shoe go. It has no nutritional value, and it’ll soon taste rotten.

definitions of success are products of their time.

Once you’ve attained ataraxia—tranquility of the soul—you’ll be able to maintain your equanimity despite the slings and arrows of fate. To put it another way, to be successful is to be imperturbable, regardless of whether you’re flying high or crash landing. How can we achieve inner success? By focusing exclusively on the things we can influence and resolutely blocking out everything else. Input, not output. Our input we can control; our output we can’t, because chance keeps sticking its oar in.

“Success is peace of mind, which is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to do your best to become the best that you are capable of becoming.”

Whichever way you look at it, the truth is that people desire external gain because it nets them internal gain. The question that suggests itself is obvious: why take the long way round? Just take the direct route.

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.” (Munger, Charlie: Wesco Annual Report 1989.)

authors Minkyung Koo, Sara B. Algoe, Timothy D. Wilson and Daniel T. Gilbert write: “Having a wonderful spouse, watching one’s team win the World Series, or getting an article accepted in a top journal are all positive events, and reflecting on them may well bring a smile; but that smile is likely to be slighter and more fleeting with each passing day, because as wonderful as these events may be, they quickly become familiar—and they become more familiar each time one reflects on them. Indeed, research shows that thinking about an event increases the extent to which it seems familiar and explainable.”

“Charlie realizes that it is difficult to find something that is really good. So, if you say ‘No’ ninety percent of the time, you’re not missing much in the world.” (Otis Booth on Charlie Munger, In: Munger, Charlie: Poor Charlie’s Almanack, Donning, 2008, p. 99).

“You’ll do better if you have passion for something in which you have aptitude. If Warren had gone into ballet, no one would have heard of him.”

They were all things that were simply a matter of deciding whether you were going to be that kind of person or not… Always hang around people better than you and you’ll float up a little bit. Hang around with the other kind and you start sliding down the pole.” (Warren Buffett quoted in: Lowe, Janet: Warren Buffett Speaks: Wit and Wisdom from the World’s Greatest Investor, John Wiley & Sons, 2007, p. 36).

“If you want to guarantee yourself a life of misery, marry somebody with the idea of changing them.”

Buffett: “We don’t try to change people. It doesn’t work well… We accept people the way they are.”

If social change is your mission, you’ll end up tangling with thousands of people and institutions who are doing everything they can to uphold the status quo. Ideally, you want to keep your mission narrowly focused. You can’t rebel against all aspects of the dominant order. Society is stronger than you are. You can only achieve personal victories in clearly defined moral niches.

“‘Don’t worry, be happy’ bromides are of no use; notice that people who are told to ‘relax’ rarely do.”

Mark Twain: “I am an old man and have known a great many troubles, but most of them have never happened.”

Howard Marks: “I tell my father’s story of the gambler who lost regularly. One day he heard about a race with only one horse in it, so he bet the rent money. Halfway around the track, the horse jumped over the fence and ran away. Invariably things can get worse than people expect. Maybe ‘worst-case’ means ‘the worst we’ve seen in the past.’ But that doesn’t mean things can’t be worse in the future.”

“Then at dinner, Bill Gates Sr. posed the question to the table: What factor did people feel was the most important in getting to where they’d gotten in life? And I said, ‘Focus.’ And Bill said the same thing. It is unclear how many people at the table understood ‘focus’ as Buffett lived that word. This kind of innate focus couldn’t be emulated. It meant the intensity that is the price of excellence. It meant the discipline and passionate perfectionism that made Thomas Edison the quintessential American inventor, Walt Disney the king of family entertainment, and James Brown the Godfather of Soul. It meant single-minded obsession with an ideal.”

“Our happiness is sometimes not very salient, and we need to do what we can to make it more so. Imagine playing a piano and not being able to hear what it sounds like. Many activities in life are like playing a piano that you do not hear…” (Dolan, Paul: Happiness by Design, Penguin, 2015, E-Book Location 1781.)

Should you find yourself in a chronically-leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is likely to be more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.” (Greenwald, Bruce C. N.; Kahn, Judd; Sonkin, Paul D.; van Biema,

As you age, change your modus operandi: become highly selective. There’s a lovely anecdote from Marshall Weinberg about going to lunch with Warren Buffett that’s worth repeating here. “He had an exceptional ham-and-cheese sandwich. A few days later, we were going out again. He said, ‘Let’s go back to that restaurant.’ I said, ‘But we were just there.’ He said, ‘Precisely. Why take a risk with another place? We know exactly what we’re going to get.’ That is what Warren looks for in stocks, too. He only invests in companies where the odds are great that they will not disappoint.”

Even the notorious U curve of life satisfaction is connected to false expectations. Young people are happy because they believe things can only ever improve—higher income, more power, greater opportunity. In middle age, between forty and fifty-five, they reach a low point. They’re forced to accept that the high-flying aspirations of their youth cannot be realized. On top of that they have children, a career, income pressures—all unexpected dampers on happiness. In old age, people are reasonably happy once more, because they’ve exceeded those unrealistically low expectations.

John Wooden: “Success is peace of mind, which is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to do your best to become the best that you are capable of becoming.”

from Epictetus, the Stoic: “A life that flows gently and easily.”

“Why, my dear friend, do you do it all? If I had all your millions, I’d spend my time doing nothing but reading, thinking and writing.” It wasn’t until I was on the way home that I realized, oddly startled, that that’s exactly what I do. So that would be a definition of the good life: somebody hands you a few million, and you don’t change anything at all.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why earning more doesn’t make you happier

This is known as Easterlin’s Paradox. It was discovered that during the period of the highest economic growth rates of the US, no significant upward change in happiness, or in academic terms Subjective well-being (SWB), were found; this was according to collected data. Why is that? Shouldn’t increased purchasing power improve your ability to find pleasure? That’s the justification of neoclassical economics’ requirement of constant growth hinges on; for economists to justify the need for a positive growth rate, happiness needs to increase with wage increases.

But because of this paradox, the justification is only socioeconomically justified. There are at least two reasons for this paradox:

Reason One: Neoclassical economics is wrong, buying more of good or service x or y doesn’t increase utility (that’s economic speak for happiness). This seems unintuitive, right? But think about it, buying two pianos instead of one just because you can afford it doesn’t make you happier. There are some goods where increasing your consumption of it may improve your happiness. E.g. At low absolute levels of purchasing power (if you’re poor), earning more affords you to buy more necessities. But if you make ends meet more of everything is just wasteful. If you buy more food than you’re used to eating, you’ll throw more food away than you usually do.

Reason Two: There is more to life than the consumption of goods and services. Think of the time it takes to create something like artwork or playing a musical piece. That time doesn’t come back and to some provides pleasure in crafting and in consuming. There’s an increase in utility by using up time in a non-economically maximizing way. That is, utility shouldn’t be measured with money constraints but time constraints. Seeking money shouldn’t be the end, it should just be a means to a more elusive end—that is enjoyment, happiness, utility, subjective well-being, whatever term you like.

Now it’s possible that you think that purchasing power does increase utility because if I have more money I can have a superior lifestyle. But what does that lifestyle entail? What kind of money and what kind of sacrifice will that entail? Isn’t being a celebrity a sacrificing of your time and privacy? In the end, time is the motivation. Spending your time the way you want, having the time to live the way you want is in the spirit of true happiness. Even though there’s the saying time equals money, money does not necessarily equal time. The side of the equation matters. You can’t buy more life with money, at least not yet. Time equals money is just referring to time spent laboring is equal to some economic endowment.

Because of these reasons the growth of the economy doesn’t seem to have such local importance at all in your life. The growth of wages doesn’t seem to improve happiness meaningfully at all, it just seems to stave off disutility. Whatever the reason, however, it just means that you should take your monetary expectations outside of your happiness expectations given you can make your ends meet. You should prioritize spending your life with your passions instead of endlessly seeking a means to them (money).

1 note

·

View note

Text

August 1, 2021

My weekly roundup of things I am up to. Topics include a case for growth, the mortality cost of carbon, and GMOs in Mexico.

A Case for Growth

A few weeks ago I lamented how I could write something called “A Case for Growth”, but because I lack institutional heft, such a piece would have little impact. Here it is anyway.

In considering the moral weight of economic growth, there are two main forces. The first, most often cited in cases against, is related to the Easterlin paradox, which holds that human well-being ceases to improve when an economy passes a certain level of wealth, a point which at least the wealthy nations of the world have now surpassed. There are many reasons why I think the paradox is wrong, at least in the form that Easterlin stated it, but I am willing to accept a weaker version that there are diminishing returns of growth to well-being, though the returns don’t reach zero. “Growth” here should be understood in monetary terms.

The second force is the decoupling force. In its strong form, (eco-economic) decoupling is a situation where the aggregate environmental impact of a society decreases while wealth increases. It doesn’t seem to me that absolute decoupling occurs, but again I am willing to accept a weaker form, that the ratio of the size of GDP to environmental impacts generally goes up in the size of GDP. There is strong evidence to support this.

We can abstract out GDP then and look at the ratio of environmental impacts to well-being. If the decoupling force is stronger than the Easterlin force, then this ratio should go down over time, and we have a strong argument for pro-growth policies. If the Easterlin force is stronger than the decoupling force, then the ratio should go up, and so that would be an argument for policies to limit growth.

It is not clear how we would answer the question of whether the impact/well-being ratio generally increases or decreases with wealth. Both the numerator and denominator are highly complex quantities whose measurement will entail a wide range of philosophic and empirical debates. It is also not clear whether there should be a general answer to this question, or if the answer will be highly contingent on circumstances. I also don’t claim that the impact/well-being ratio is the only factor that would answer the growth question, only a major factor.

Caveats side, I think there is a case that the impact/well-being ratio does in fact go down with increasing wealth, and the ratio should continue to decrease for any level of wealth that could be obtained in the foreseeable future.

Mortality Cost of Carbon

A new paper this week estimates the death toll that results from CO2 emissions. The focus is on deaths relating specifically to heat.

They estimate that there will be 83 million temperature related deaths around the world from 2020-2100 in the DICE baseline scenario (a model of future emissions), while the death toll would be 9 million under an optimal emissions scenario. This works out to about 1 million deaths per year, I presume more heavily concentrated later in the century, which would make climate change comparable to, or a bit less than, other mortality risks, such as air pollution, automobile accidents, etc.

The paper also translates these figures into 1 excess death for the average lifetime emissions of 3.5 Americans, a figure that got a lot of attention in the press. In monetary terms, the paper estimates that consideration of mortality risks raises the social cost of carbon from $37/ton to $258/ton, a difference that would have an enormous effect on the range of CO2 mitigation strategies that are economically viable.

In 2014, the World Health Organization estimated that climate change would be responsible for 250,000 deaths per year from 2030-2050. These numbers are less than the recent paper, but they focus on an earlier time frame, so at least they seem to be compatible. However, the WHO only has ~38K deaths from heat exposure, as well as ~48K from diarrhea, ~60K from the expansion of tropical diseases, and ~95K from nutrition. In understanding the latter, climate change will have a negative impact on crop yields on net (though a positive impact in some places like Russia and Canada).

I don’t know how reliable any of these numbers are. Hopefully advances in medical care, agronomy, and other fields will have benefits that dwarf the negative impacts of climate change.

GMOs in Mexico

Mexico’s president announced a ban on GMO corn and glyphosphate in the country.

It was pointed out to me on Twitter that it is unclear whether this policy would apply to animal feed or just corn for human consumption. In the case of the latter, there is not much imported or GMO corn for humans, so the impact of the policy would be largely symbolic. In the case of the former, the impact could be substantial, both in terms of food security and the ecological impact of the expansion of land for corn production.

After reaching a peak around 2013 or 2014, public interest in genetic modification has been waning. Opponents of GMOs have been losing credibility as well. I thought this recent piece from the New York Times was instructive; I don’t think that five years ago, the NYT would have been willing to risk the fallout of writing such a piece.

Still, political movements seldom go away completely. Like the embers from a campfire beneath the ash, they can smolder for a long time, ready to reignite at a future time when conditions are again opportune. And even in its present diminished state, a core of anti-GMO activists can still exercise influence when the right politicians for them are in the right place.

The linked article itself comes from an anti-GMO source, and it repeats many of the misleading tropes that characterize the movement. You would never know from reading it, for instance, that credible scientific organizations such as the National Academy of Sciences have found no evidence of harm from GMOs per se. The FUD tactics in the article are reminiscent of the anti-vaccine movement more than anything else, which shouldn’t be a great surprise given the nexus between the two.

0 notes

Text

En 1974, Richard Easterlin publie une étude empirique montrant que le PIB par habitant, au-delà d'un certain seuil de richesse, n'a pas d'effet sur le niveau de satisfaction des individus. Ce paradoxe est connu dans la littérature économique sous le nom de « paradoxe d'Easterlin »53.

Il a été remis en cause en 2008 par l'étude de Justin Wolfers et Betsey Stevenson, montrant à l'aide de données individuelles collectées dans un grand nombre de pays qu'il existe bien un lien entre le PIB par habitant et le degré de satisfaction des individus54.

Une étude plus approfondie, publiée en 2013 par la revue PLOS ONE, confirme les conclusions d'Easterlin : la satisfaction de vivre s’accroît fortement avec le PIB dans les pays à faible revenu, mais la relation devient beaucoup moins pentue au-delà d’un PIB de 10 000 $, puis elle s’aplatit avec un PIB au-delà de 15 000 $, et tend même à décliner avec le PIB dans les pays les plus riches, suggérant l’existence d’un « point de béatitude » qui se situe dans l’intervalle entre 26 000 et 30 000 US $ en parité de pouvoir d’achat

0 notes

Text

Title: Money Buys Freedom, Not Happiness

Money is often seen as a means to achieve happiness, but it is crucial to recognize that while money can buy freedom and comfort, it does not guarantee genuine happiness. This essay delves into the relationship between money, freedom, and happiness, highlighting that while financial stability provides opportunities and choices, true happiness stems from deeper sources.

To begin with, money undoubtedly provides a sense of freedom. Financial stability allows individuals to make choices that align with their preferences and aspirations. It grants access to education, healthcare, travel, and experiences that enhance quality of life. Moreover, financial independence can alleviate stress and anxiety related to basic needs, offering a sense of security and peace of mind.

However, the misconception arises when money is equated with happiness. Numerous studies have shown that beyond a certain threshold of income where basic needs are met, additional wealth has diminishing returns in terms of happiness. This phenomenon, known as the Easterlin Paradox, suggests that while income growth may initially correlate with increased happiness, it plateaus once basic necessities are fulfilled.

Furthermore, the pursuit of wealth can lead to detrimental consequences for mental well-being. The relentless pursuit of material wealth and societal status often results in a constant desire for more, leading to a cycle of dissatisfaction and never feeling "enough." This materialistic mindset can erode meaningful relationships, diminish empathy, and contribute to a sense of emptiness despite material abundance.

On the contrary, happiness is deeply rooted in factors such as fulfilling relationships, a sense of purpose, personal growth, and overall well-being. These aspects of life often transcend monetary considerations. For instance, spending quality time with loved ones, engaging in meaningful work, pursuing hobbies, contributing to community, and practicing gratitude are all elements that contribute significantly to happiness, regardless of financial status.

Moreover, research in positive psychology emphasizes the importance of intrinsic factors in happiness, such as self-acceptance, autonomy, mastery, and a sense of belonging. These elements of psychological well-being are not contingent on external wealth but rather on internal attitudes and perspectives.

In essence, while money can provide freedom and opportunities, it is not the sole determinant of happiness. True happiness stems from a holistic approach to life that encompasses fulfilling relationships, personal growth, meaningful experiences, and a sense of purpose. By prioritizing these intrinsic aspects of well-being alongside financial stability, individuals can cultivate a more balanced and fulfilling life.

In conclusion, money buys freedom in terms of choices and opportunities, but it does not inherently buy happiness. Happiness is a multifaceted construct that transcends material wealth, rooted in fulfilling relationships, personal growth, purposeful living, and psychological well-being. Striking a balance between financial stability and intrinsic sources of happiness is essential for a fulfilling and meaningful life journey.

0 notes

Photo

Above a certain GDP level, increasing GDP does not generate greater development on the selected SDGs. Approx. USD 12,000 annual income per capita. AN example of The 'Easterlin Paradox, which states that at a point in time happiness varies directly with income both among and within nations, but over time happiness does not trend upward as income continues to grow

0 notes

Text

Money really can buy happiness and recessions can take it away

Blessed are the rich in spirit

Money really can buy happiness and recessions can take it away

Polls from 145 countries show that citizens of wealthier ones are more satisfied and secure

GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT (GDP), the most common gauge of national prosperity, has taken a lot of flak in recent years. Critics say that counting a country’s spending on goods, services and investment misses the full value that citizens get from products such as Google and Facebook. They also note that GDP ignores other aspects of development, including personal health, leisure time and happiness.

These criticisms probably exaggerate GDP’s failure to capture the wealth of nations. Gallup, a pollster, has asked people in 145 countries about various aspects of well-being. Many of these correlate strongly with GDP per person. To take an obvious example, nearly all residents in the top 10% of countries by spending say they have enough money for food, compared with just two-fifths of those in the bottom 10%.

Strikingly, many non-financial indicators also track GDP per person closely. Residents in the top 10% of countries score their life situation as seven out of ten, compared with just four for those in the bottom 10%. They are also more likely to feel supported by their families, safe in their neighbourhoods and be trusting of their politicians—though they complain nearly as much as people in poor countries do about a lack of rest and affordable housing.

Scholars disagree over the extent to which national wealth itself causes contentment. Some countries’ citizens have remained glum even as GDP per person has risen, a paradox noted by Richard Easterlin, an American economist. But one way of testing if money buys happiness is to analyse what happens when it goes away.

Studies of the previous global recession in 2009 suggest that economic hardship does indeed lead to emotional woe. Academics found dips in life satisfaction and other measures of well-being in the United States and several European countries, though the effects were mainly limited to people who lost their jobs. Adam Mayer of Colorado State University found that among Europeans of similar wealth and education, those who had recently become unemployed and struggled to buy staple foods had the worst outlook on life.

Covid-19 will allow economists to probe this pattern further. The IMF’s latest forecast points to a fall in global GDP, weighted by purchasing-power parity, of 4.9% this year. If past recessions are any guide, the severe shock will have long-lasting effects. Economies will eventually grow larger than they were before the pandemic, but will be less rich than they would have been otherwise. The virus’s human toll is therefore vast in terms of deaths and dollars. But given the correlation between GDP per person and Gallup’s measures of well-being, it may have an enduring impact on the world’s quality of life too. ■

Sources: Gallup; World Bank; World Happiness Report

This article appeared in the Graphic detail section of the print edition under the headline "Blessed are the rich in spirit"

https://ift.tt/2W1srl0

0 notes

Text

GDP doesn’t make people happy- Is it time for a new approach to measure economies?

by Tommaso Rocchi

Our economic systems are often analyzed to understand what is going bad or good and to compare them with other countries’ economies. In order to do this, common indicators are needed. In recent years there has been a lot of talking on the necessity of production growth in particular in the Euro area. Production growth is measured through GDP: the amount of finished goods and services produced in one year in a country. As it is reported in an article by The Economist, many economists wonder whether it is right and appropriate to continue using GDP as an indicator of an economy.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, IMF head Christine Lagarde and MIT professor Erik Brynjolfsson, among others, criticize that. Joseph Stiglitz supports the thesis according to which GDP is neither a good measure of economic performance nor a good measure of well-being. However, this indicator is used in most countries around the world.

Two considerations should be made on whether GDP is a good indicator of well-being and of economic performance. Regarding the first consideration, one problem is to understand whether a higher level of GDP corresponds to a higher level of well-being. That is, is there a correlation between wellness and GDP? We have a correlation when two variables are strictly dependent on one another: that is to say, for example, that if we have two variables, x and y, and they change together over time, there is a high level of correlation. It means, in short, that the two things are moving together.

Just as language is not only a way to communicate with other people, but it also conditions a person’s thoughts, variables used in economics or math will be the cause of how politicians and economists will reason to solve certain problems. It turns out that if the indexes considered are the wrong ones, then the policies adopted will also be so.

We can see that the GDP does not adequately take into account the damage that production causes to the environment, nor the quality of the relationships between people, instead considering for example the medicines sold. GDP does not take into account the increase in diseases due to depression and anxiety in developed countries or dependencies on drugs or eating disorders such as obesity or even anorexia. To overcome these shortcomings, Butan invented a different system, the Gross National Happiness (GNH). This is the opposite of the previous considerations, but the right thing would be to find a halfway point. Moreover, another fact that is not considered in GDP’s calculations is the unpaid care work or so called “home production”, by both men or women, which would boost GDP significantly. Furthermore, GDP does not include the submerged economy. The many hours of volunteering activity are also not included, whereas the revenues from the sale of drugs or paid sex are included, for the latter case as occurs in Britain, where this is included in calculations.

Considering economic production now, the issue from which to start is to understand whether GDP is a good production index, if it performs well the basic task for which it was invented. The context must first be considered. The Gross Domestic Product as a production index had been introduced from the period between the two world wars. At that time and for many years to follow, most of the production was characterized by manufacturing. It was probably soon to think of the radical changes that would have occurred over the next decades and exponentially from the 90’s to the present. The fact is that GDP, like other indices, is extremely difficult to calculate. The future is more and more technological and this creates and has created the need to keep up with the times. The change made by technology has made it necessary to take account of new services. There are many services, for example, that are given for free to users that were instead paid at the time, and advertising is what companies mainly pay now. It is sufficient to think of services such as Facebook, Youtube or Spotify. All this makes calculations even harder.

GDP does not take into account the inequalities that exist within a country, because it is an average of that country. In addition, as the Easterlin paradox notes, an increase in a poor person’s income can easily improve his happiness and well-being: eating, improving quality of spending, education, healthcare, enjoyment of leisure time, holidays. However, an increase in the income of a wealthy person does not have the same effect: they do not become happier the more they gain, but only to a certain extent, and this is the same also for a developed country. To conclude, in a speech at the University of Kansas, Robert Kennedy claimed that there is a risk in considering GDP as a central aim, that is not considering that there may be a crisis of values that may not be included. In his words, GDP “measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile”, considering also that it includes the production of weapons of mass destruction and not for example the intelligence of our public debate.

So it may be time to think of a fresher and more inclusive approach to measure economies. It is interesting to note that there is increasingly wider concern about the human feelings and their impact on the economy, and the so called behavioral economics. Just as an example, some economists consider that there are important variables that should be included in the calculations of an economy, as it is shared in the World Happiness Report. Among the other variables, is someone to count on, generosity and absence of corruption. Other approaches look at quality of life and education, recognition of rights and so on. However, one conclusion that some economists may share is that money (and GDP) don’t make people happy, but they can help.

1 note

·

View note

Link

It’s the question that has baffled economists for generations. Why doesn’t economic growth make us happier? This used to be known as “Easterlin’s Paradox” after economist Richard Easterlin. He pointed out way back in the 1970s that the industrialized world’s miraculous leaps in per capita GDP were not being matched by much, if any, gains in average life satisfaction. via Snapzu : Business & Economy

0 notes

Text

Examining Easterlin’s Paradox in Post-Reform China

Had a great time writing this piece for The International Academic Forum‘s interdisciplinary academic platform, Think, designed for both the academic community and general readership.

How far is money related to levels of satisfaction with life? Dr Matthew J. Monnot of the University of San Francisco, United States, discusses the contrast between decades of GDP growth in China and stagnant levels of individual life and job satisfaction, questioning whether monetary incentives can fill evolved psychological needs and examining the relationship between material aspirations and individual well-being.

Click over to give it a read at The Goods Life: China’s Wealth and Happiness Paradox

Note: Full citations for references were not provided in the article. They are listed here:

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Seidlitz, L., & Diener, M. (1993). The relationship between income and subjective well-being: Relative or absolute? Social Indicators Research, 28, 195–223.

Gu, F. G., & Hung, K. (2009). Materialism among adolescents in China: A historical generation perspective. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 3(2), 56–64.

Easterlin (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.). Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz. New York: Academic Press, Inc.

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990-2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (25), 9775-9780.

Kahneman, D., & Deton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 (38), 16489-16493.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65 (2), 410-422.

Monnot, M. J. (2015). Marginal utility and economic development: Intrinsic verses extrinsic aspirations and subjective well-being among Chinese employees. Social Indicators Research. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1080/14697017.2016.1237534

Steele, L. G. & Lynch, S. M. (2013). The pursuit of happiness in China: Individualsm, collectivism, and subjective well-being China’s economic and social transformation. Social Indicators Research, 114 (2), 441-451.

Van den Broeck, Al., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C-H., Rosen, C. C. (2016). A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management, 42 (5), 1195-1229.

from Examining Easterlin’s Paradox in Post-Reform China

0 notes

Text

052 Jonathan Clements

http://www.alainguillot.com/jonathan-clements/

Jonathan Clements has spent the last 33 years writing and thinking about money out of which he spent almost 20 years at The Wall Street Journal, where he was the newspaper’s personal finance columnist.

He's the founder of the website HumbleDollar.com, he has written a novel and eight personal finance books, and also contributed to five others.

We spoke about

His latest book is From Here to Financial Happiness and How to Think About Money.

Easterlin paradox: Easterlin argued that life satisfaction does rise with average incomes but only up to a point. Beyond that, the marginal gain in happiness declines.

Tips from Jonathan

Don't put yourself in a situation where you are at a comparative disadvantage with other people. Comparing yourself with people who have more will make you unhappy.

Invest in experiences, not on things.

Check out this episode!

0 notes