Text

Today marks the premier of #Pathfinder’s Triumph of the Tusk Adventure Path, so I’d like to take a moment to discuss a relevant topic near and dear to my heart.

ORCS!

While Tolkien was drawing on some linguistic antecedents, Orcs in fantasy originate from The Hobbit & Lord of the Rings, where they’re brutish soldiers of various forces of evil.

Initially lacking redeeming quality, Orcs have become a darling of pop culture, their thuggish nature explored from many angles across TTRPGs, video games, comics, novels, and more.

Now, when you picture an Orc, you no doubt imagine something akin to the Warcraft or Warhammer franchises: statuesque, green skinned humanoids with protruding underbites and looming tusks, often locked into a primitive, itinerant lifestyle, eschewing technology beyond what they pillage from other races.

Interestingly, none of this is in Tolkien.

In Tolkien, “Orc” was essentially another word for “Goblin,” or perhaps unusually large Goblins. Far from statuesque, Gollum (a (former?) Hobbit) could easily be confused for one. The Uruk-hai, a new, stronger Orcish offshoot were described as Orcish in appearance but only as tall as a Man, not taller.

Tolkien’s Orcs are described as deformed, but nothing as specific as green skin or tusks is specifically mentioned (Tolkien saved in-depth sensory detail for trees, and occasionally beards).

Far from being savages, Tolkien’s Orcs were–in his grand Romanticist narrative–stand-ins for industrialization. They were destroying the forests to build grand weapons of war, and soot-covered Mordor evoked the smokestacks of 19th century london.

In many ways the conflict of LotR can be interpreted as Tolkien pitting the noble myths and tales he studied up against his real experiences in WWI.

(the thought amuses me of a firmly medieval fantasy setting, except when we zoom in on the Orcish Badlands they’re all shelling each other from the trenches)

But while none of these traits are in Tolkien, there is a source where they are central.

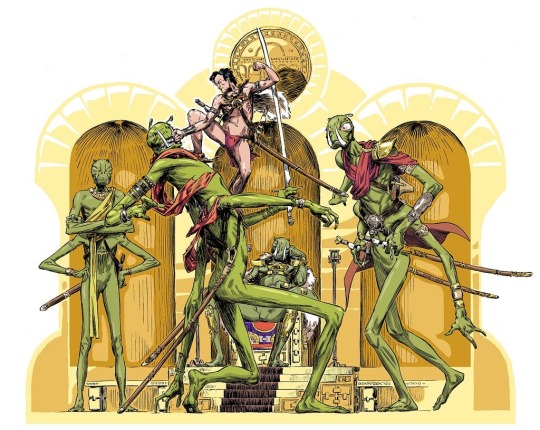

The Green Martians, or Tharks, first appeared in A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, published in All-Story Magazine from Feb-July 1912, well before any of the kids Tolkien decided to tell a fairy tale to were born.

The Tharks are described as 15 foot tall nomadic savages, favoring mighty beasts and weapons salvaged from the more civilized races of Barsoom. They have green skin and tusks, as well as six limbs (interestingly, the middle limbs are described as functional as either crude arms or secondary legs, but art always just depicts four arms)

Culturally, the Tharks are clearly meant as extensions of the Apache raiders encountered in the early chapters of the book set in Arizona; i.e. some California ranch-owner’s idea of wasteland savages. Nomadic, inhuman raiders redeemable only when breaching their primitive traditions.

The parallels are almost uncanny, and I’ll admit I’m honestly not sure where the crossover occurs. Early editions of D&D–another driver of fantasy trends–depict orcs as pig-people, which is probably how tusks became so iconic. They later added gray skin, which persisted officially until the current edition.

Somewhere between there in ‘74 and Warhammer in the early 80s is when the pseudo-Barsoom look took over in broader culture, and at this point there’s no getting around it. Even the more recent Tolkien film adaptations can’t entirely escape the expectation of modern Orcishness.

Turning back the clock a bit, Tolkien notably was never entirely sure where Orcs came from. His first idea was that they were molded from clay by Morgoth, a dark mirror to Adam, but being a Catholic at heart, he disliked the idea of Evil being a creative force.

He flip-flopped for the rest of his life, whether Orcs were corrupted men/elves/hobbits, uplifted beasts, even (according to one post I saw) soulless bodies remotely piloted by demons. He could never quite square the need for unfailingly evil mooks with his own feelings on Good & Evil.

Personally, I find particular resonance in the parallel between what D&D used to call an “always chaotic evil” race and the very Catholic concept of Original Sin. Was Tolkien merely dancing around the idea that the Orcs only needed to be Saved?

I can’t say what Tolkien would think of modern Orcs, either their merging with an earlier, American space alien, or our attempts to humanize what was supposed to be fundamentally inhuman. But I think his insecurity speaks to the same source as our fascination.

Who among us hasn’t struggled with what it means to be good? Or to be evil? And if we are made to be evil, what does it mean to strive against that purpose or to surrender to it? Can we abandon the precepts of predestiny? Or do we reject that they were ever there?

Stare deeply into that Jungian shadow and tell me…

Is it green? And do you want it to be?

#orcs#orc#j r r tolkien#tolkien#pathfinder#pathfinder 2e#triumph of the tusk#adventure path#the hobbit#the lord of the rings#lord of the rings#world of warcraft#Warcraft#Warhammer#warhammer 40k#warhammer fantasy#orks#edgar rice burroughs#a princess of mars#barsoom#green martians#tharks

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

It feels odd that while Lovecraft's racism is often the first thing the mind jumps to when discussing him, the same isn't really true for other prominent pulp authors. Especially considering Edgar Rice Burroughs whole oeuvre is a celebration of white supremacy and eugenics. Tarzan boasts that he's a "killer of beasts and many black men." Utopias that have bred out crime through execution or sterilization of criminals' families are a repeated staple of his fiction. It wasn't just his fiction either; the man wrote a newspaper column calling for the killing of "moral imbeciles" and their families [source].

Its not like they were writing in wildly different times; the first Tarzan book came out only seven years before Lovecraft's Dagon. And they both were incredibly influential and celebrated figures in specific genre niches that still command wide attention. But while his racism isn't unknown, it doesn't seem to be attached to Burrough's public character in the same way it is for Lovecraft. Why doesn't he have multiple generations of pulp fans coming to terms with how the author they idolize is awful? Are there just not enough people reading A Princess of Mars these days?

#see also doc savage performing brain operations on criminals to make them docile#mals says#pulp fiction#eugenics#racism#hp lovecraft#edgar rice burroughs

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Clyde Caldwell, 'Barsoom', ''Heavy Metal'', September 1982 Source

#clyde caldwell#american artists#barsoom#edgar rice burroughs#heavy metal magazine#john carter#Dejah Thoris#scifi art#science fiction art#fantasy art#color illustration

285 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dana Gillespie - The People That Time Forgot (1977)

#dana gillespie gif#the people that time forgot gif#70s fantasy movies#amicus productions#edgar rice burroughs#kevin connor#ajor#70s movies#seventies#1977#gif#chronoscaph gif

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Showcasing art from some of my favourite artists, and those that have attracted my attention, in the field of visual arts, including vintage; pulp; pop culture; books and comics; concert posters; fantastical and imaginative realism; classical; contemporary; new contemporary; pop surrealism; conceptual and illustration.

The art of Richard Hescox.

#Art#Richard Hescox#Fantasy Art#Fantastical Art#Imaginative Realism#Books#Book Cover#Book Cover Art#Cover Art#Edgar Rice Burroughs#Game Of Thrones#ASOIAF#Swamp Thing#Tarzan#The Dark Crystal

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

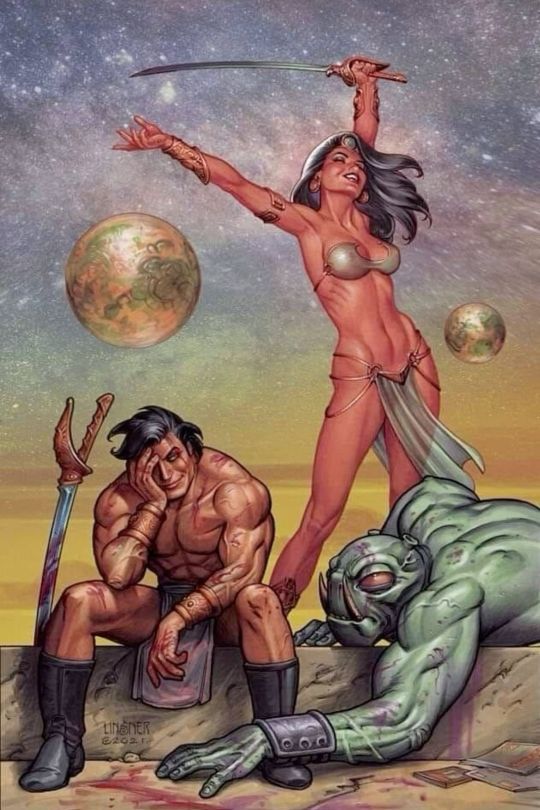

John Carter and Dejah Thoris by Joseph Linsner.

#John Carter of Mars#Dejah Thoris#John Carter#green man of Mars#Mars#Barsoom#Edgar Rice Burroughs#Joseph Linsner

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

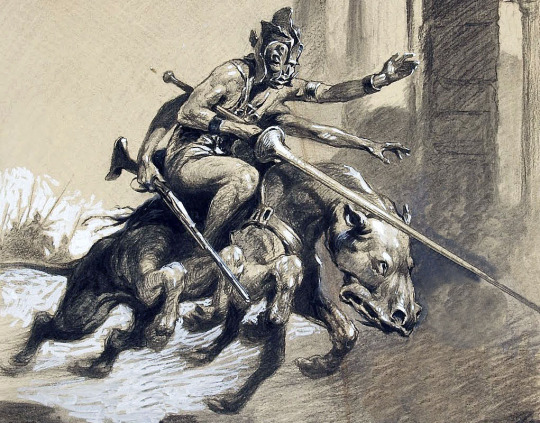

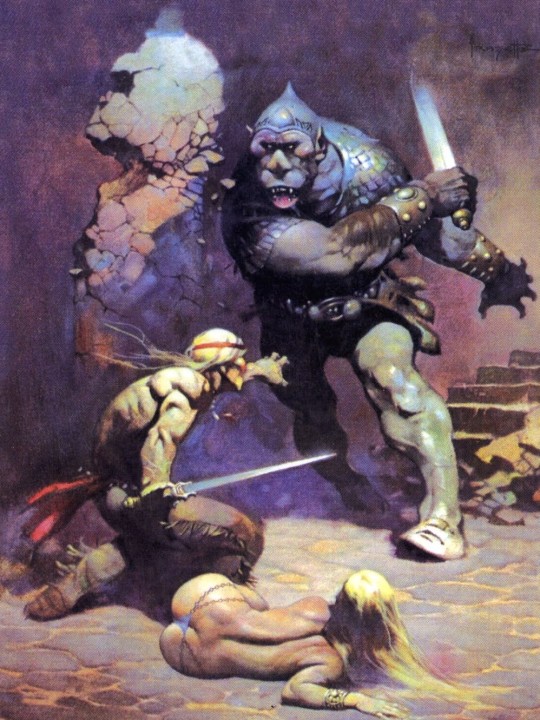

Tarzan And The Castaways

Art by Frank Frazetta

#Comics#Frank Frazetta#Tarzan#Jungle#Jungle Comics#Fantasy#Pulp#Pulp Art#Pulp Illustration#ERB#Edgar Rice Burroughs

123 notes

·

View notes

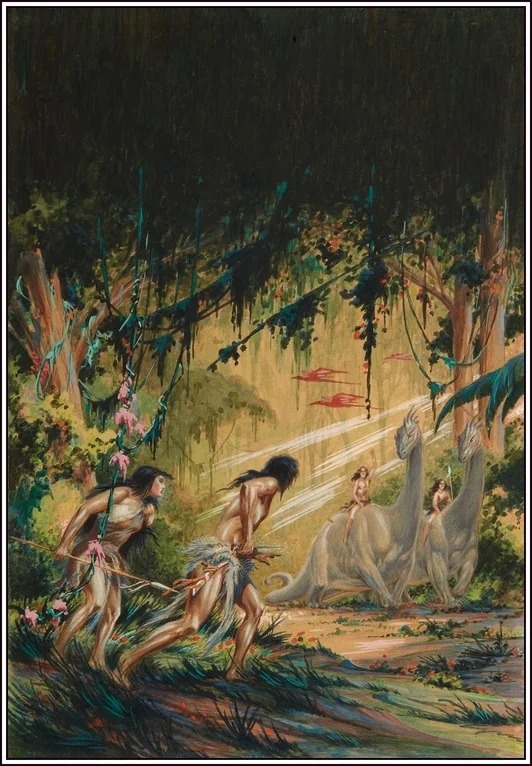

Photo

Roy Krenkel's 1962 cover to "At the Earth's Core," by Edgar Rice Burroughs

706 notes

·

View notes

Text

the Burroughs Artist Portfolio, by Roy G Krenkel

#the Burroughs Artist Portfolio#Portfolio#Edgar Rice Burroughs#Tarzan#RGK#Roy G Krenkel#Roy G. Krenkel#Master Class#Art#Comics#Illustration

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tarzan at the Earth's Core by Bill Stout.

#tarzan#edgar rice burroughs#bill stout#william stout#science fiction art#illustration#adventure#science fiction#dinosaurs

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

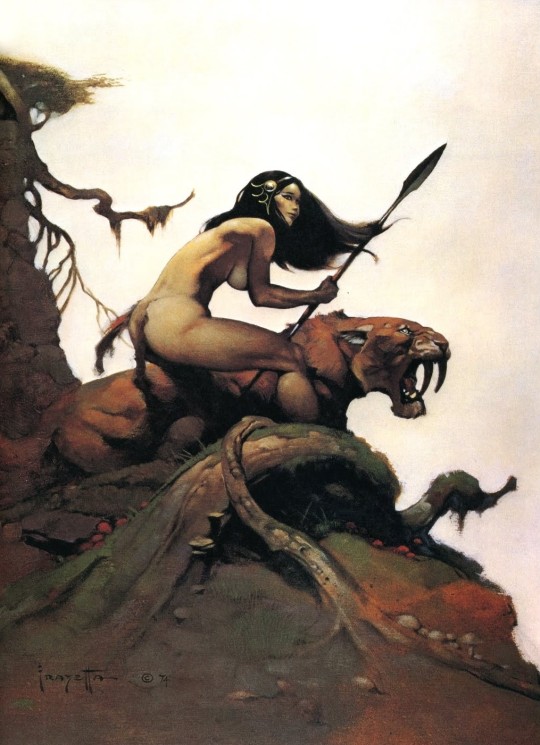

Illustrations by Frank Frazetta (1970's)

#frank frazetta#art#illustration#1970s#1970s art#vintage art#vintage illustration#vintage#american art#american artist#american illustrators#pulp illustration#books#book cover#edgar rice burroughs#fantasy#fantasy art#classic art

930 notes

·

View notes

Text

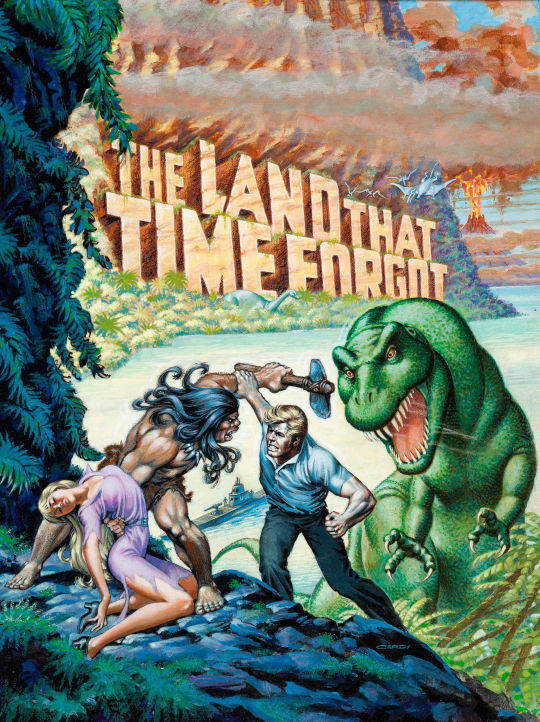

Nick Cardy's cover for Marvel's "Land That Time Forgot" Special, 1975.

390 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Carter of Mars by Joe Jusko.

#joe jusko#john carter#pulp#horror#pulps#science fiction#pulp science fiction#pulp horror#pulp art#sci fi#edgar rice burroughs#erb#pulp sci fi

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

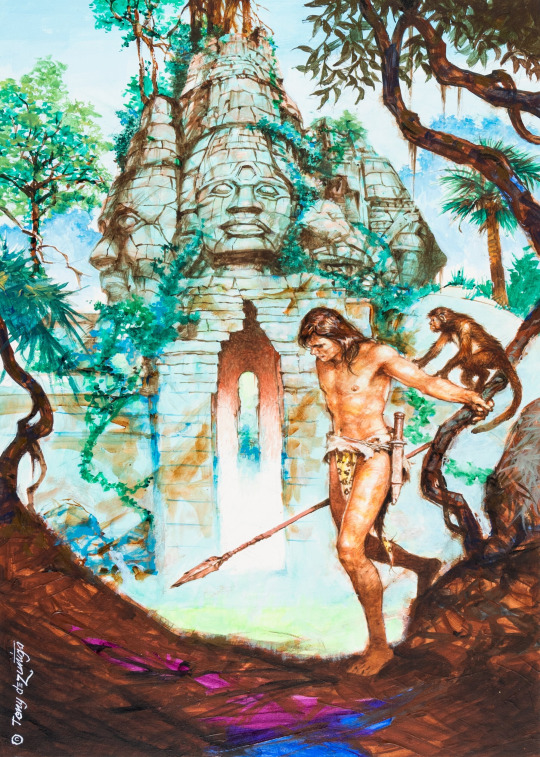

Tarzan and the Lost Outpost of Atlantis - art by Tony DeZuniga (c. 2010)

#tony dezuniga#tarzan and the lost outpost of atlantis#fantasy art#comic artist#edgar rice burroughs#jungle adventures#2010s#2010

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

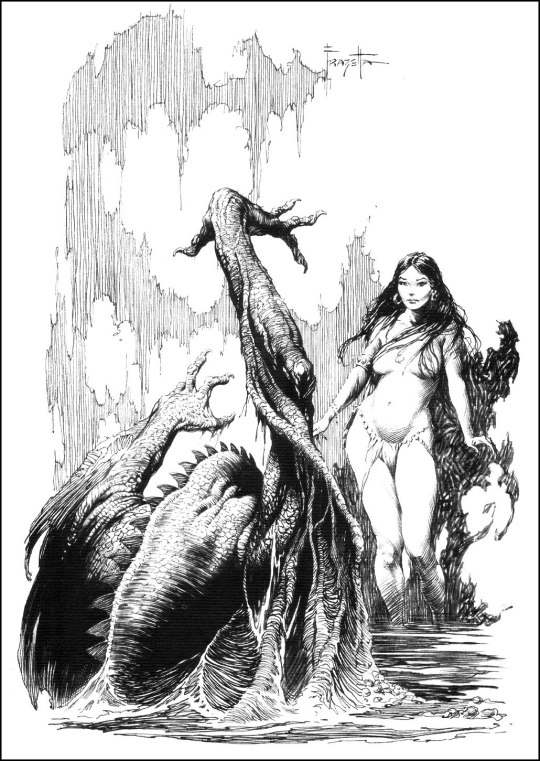

'In A Trance' by Frank Frazetta.

Interior illustration from the 1972 edition of the novel 'At The Earth's Core', Book 1 of the Pellucidar series by Edgar Rice Burroughs.

#Art Of The Day#Art#AOTD#Frank Frazetta#Frazetta#Frazetta Friday#At The Earth's Core#Edgar Rice Burroughs#Pellucidar#Illustration#Books#Book Illustration#Fantasy Art#Fantastical Art#Imaginative Realism

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

A signed Tarzan sketch by Hal Foster.

118 notes

·

View notes