#Epiros

Note

Hello, I hope you're well :D I have some questions related to Olympias.

Was she "de facto leader of Macedonia" as it says on wikipedia? She was also regent for her cousin Eacides, and for a few months also regent on behalf of Alexander IV?

I’ve actually written a fair number of entries on Olympias. But in most, I refer to THE leading authority on her life: Elizabeth D. Carney. The number of articles (and books) this woman has written is a just a little scary!

If you are interested in Olympias, ignore everything on the internet (even me) and go and buy Beth’s book: Olympias: Mother of Alexander the Great. It’s been out a while, so you can probably find it used at a fair price, or find it in a library, especially a university library. If you can’t find it or afford to buy it, ask the library to get it for you via “interlibrary loan.”

Bonus. She’s easy to read, has a very good narrative style (imo). And yes, when she gives lectures, she talks just like she writes. Ha. (Not all authors do.) When I’m reading Beth’s stuff, I can almost always “hear” her voice in my head, amusingly.

Anyway, just start there; she will answer every question you have, and some you never would have thought of. Very rarely can I give such a singular “Go read this” suggestion as with Beth’s book on Olympias. She has several other good ones, including on Macedonian women generally, and on Eurydike, Philip II’s mother (e.g., ATG’s grandmother).

Now, as for my own posts on Olympias, here are some. I mention her quite frequently (as a search of “asks” + “Olympias” will show), but these are some of the longer ones.

Olympias’s role in Macedonia was complicated, and she was not de facto leader except in some respects, especially as it involved religion. When it came to war, and politics, that was Antipatros. That may be one reason Olympias eventually retreated to Epiros later in Alexander’s campaign, where she had more influence. But again, Beth’s book is much better about explaining all of that.

How Old Was Olympias When She Married Philip? A general post on Olympias herself and her background, that should help contextualize where she came from and what expectations she may have had, for her role as Philip’s 4th or 5th wife.

Olympias’s Relationships with Philip’s Other Wives. This discusses dynamics in a polygamous household like Macedonia.

Did Philip and Alexander of Epiros Have an Affair? While this is more about Olympias’s younger brother, it addresses, again, family dynamics in Epiros and Olympias’s role at the court (both courts).

Finally, a pair of posts on Philip’s murder, and Alexander and Olympias’s (non-)role in it. IMO.

Who Killed Philip of Macedon?

Did Alexander and Hephaistion (and Olympias) Know about the Plot?

Hope all this helps!

#Elizabeth Carney#Olympias#Olympias's role at the Macedonian Court#Collection of links to my articles on Olympias#Eurydike#Macedonian Women#Classics#Women scholars in Classics#Ancient Macedonia#Ancient Epiros

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drakolimni (Dragon Lake)

on the AlpinebMountain of Tymfi, Epiros, North Western Mainland, Greece

836 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Tetradrachm of Lokroi Epizephyriori with head of Zeus, struck under Pyrrhos of Epiros.

Culture: Greek

Period: Early Hellenistic

Date: 280–277 B.C.

Medium: Silver

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient greek#greece#greek#ancient currency#coin#archaeology#tetradrachm#Lokroi Epizephyriori#Hellenistic#silver#280 b.c.#277 b.c.

547 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Beard of the Pasha

When Ali Pasha ruled Ioannina, St. Kosmas of Aitolia prophesied to him about all the territories he would conquer.

Ali Pasha was told by the saint, “You will become a great man, you will conquer all of Albania, you will subjugate Preveza, Parga, Souli, Delvino, Gardiki, and the very stronghold of Kurt Pasha. You will leave a great name in the world. Also, you will go to Constantinople... but with a red beard. This is the will of Divine Providence.”

Saint Kosmas was martyred in August 24, 1779 after he was accused of being a Russian agent against the Ottomans. Indeed, Ali Pasha went on to become the sole ruler of Epiros, subjugating all of Albania and parts of Greece.

In January 1822, Ali Pasha was beheaded by his adversaries and his head was paraded on a silver platter throughout the streets of Ioannina, before it was sent to Constantinople. Thus came the fulfillment of Saint Kosmas’s prophecy that Ali Pasha of Ioannina would enter Constantinople with a beard made crimson by his own blood.

#Saint Kosmas Aitolos#synaxarion#orthodox christianity#eastern orthodoxy#eastern orthodox#orthodoxy#orthodox#christianity

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabella of Villehardouin (1260/1263 – 23 January 1312) was reigning Princess of Achaea from 1289 to 1307. She was the elder daughter of Prince William II of Achaea and of his third wife, Anna Komnene Doukaina, the second daughter of Michael II Komnenos Doukas, the despot of Epiros.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ADIVINACIÓN EN DODONA

Efectivamente, el santuario de Dodona, situado en el Epiro, una región al noroeste de la Grecia continental, es el oráculo más antiguo del mundo griego, pues sus orígenes se retrotraen al Heládico Antiguo I (ca. 3000-2600 a.C.). El santuario estaba consagrado a Zeus Naios, que compartía el templo con su forma femenina, Dione Naia, y ambos aparecen representados en monedas de esta región. Además, se han conservado tablillas en distintos dialectos griegos que contienen las preguntas que se le hacían al oráculo y las respuestas que este daba, lo que refleja que acudían a Dodona personas procedentes de todo el mundo griego. Pero, ¿cómo se llevaba a cabo la adivinación oracular?

Homero, en la Ilíada (XVI, 233-249), hace referencia a Dodona y dice que está “lejos”, pues el Epiro era, en efecto, una zona periférica y alejada de las grandes polis griegas. Además, menciona a los “selos”, los intérpretes de Zeus Dodoneo, que “no se lavan los pies y duermen en el suelo”, lo cual se entiende teniendo en cuenta la importancia que se concede en estos ámbitos al contacto directo con la tierra, de donde brotan los poderes oraculares. Sin embargo, estos misteriosos sacerdotes masculinos desaparecen en época arcaica y ya a mediados del s. V a.C. el oráculo de Dodona está dirigido por tres sacerdotisas que eran llamadas “palomas”.Tradicionalmente, las respuestas oraculares se daban a través de la interpretación del sonido que producían las hojas de la encina sagrada cuando soplaba el viento, aunque estas respuestas también podían emanar de las palomas que estaban posadas en este árbol, como recoge Heródoto (II, 55). Otro procedimiento de adivinación documentado, que tenía también relación con la interpretación de sonidos, se hacía a partir de unos calderos de bronce que se colocaban en alto sobre unos trípodes y que chocaban entre sí produciendo distintas reverberaciones. Normalmente, como reflejan las tablillas mencionadas, las consultas las hacían particulares y el oráculo contestaba de manera simple con formulaciones de “sí” o “no”.

Así pues, Dodona contó con un gran prestigio dentro del mundo griego, aunque su relativo aislamiento hizo que fuese eclipsado en gran medida por el santuario de Delfos. A pesar de esto, el santuario conservó su importancia y, durante el reinado de Pirro (s. IV-III a.C.), se convirtió en el centro religioso del reino constituyéndose la festividad de Naia.

¿Serías ahora capaz de responder estas preguntas? ¡Mira nuestra siguiente publicación a través de las etiquetas o del enlace en comentarios!

Bibliografía

-Parke, H. W. (2015). Dodona. Oxford Classical Dictionary. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.2264

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

La mirada de Alejandro Magno

Uno de los rasgos físicos de Alejandro Magno más llamativos, con más quórum entre sus biógrafos y más característicos es la heterocromía ocular que al parecer padeció, es decir, presentar ambos ojos de distinto color.

"La mirada es el reflejo del alma"

Se dice que el rey macedonio tenía el ojo izquierdo de color marrón y el derecho de color gris, aunque se desconoce si desde nacimiento o fue fruto de una lesión. Este tipo de color de los iris se relacionaba con una parte femenina y sobretodo con una parte psíquica, mágica incluso, considerándose en algunas culturas "ojos de fantasma" dado a que se creía que conferían a la persona que los poseyese la capacidad de ver tanto en el cielo como en la tierra, o que en el momento del nacimiento uno de los ojos del niño había sido cambiado con el de una bruja.

De Alejandro Magno se decía que su personalidad era una mezcla de la naturaleza temperamental y ocultista de su madre, Olimpia de Epiro, una gran seguidora del Dios Dionisio, y de su lado racional y diplomático, por parte de su padre, Filipo II de Macedonia. Es por ello que este rasgo podría, como en cualquier descripción de una persona de tal magnitud, contribuir al mito y a la leyenda de esta dualidad de su alma, tan bien reflejada a nivel físico.

¿Qué pudo causarle este rasgo?

La heterocromía es un rasgo muy poco frecuente en seres humanos y normalmente es de consideración benigna, aunque puede estar detrás de varios síndromes y causas. Por varias referencias, tiendo a considerar las causas más probables la heterocromía familiar (el traslado de un gen autosómico dominante por parte de uno de los progenitores), el síndrome de Waadenburg, el síndrome de Horner y sobretodo una posible lesión o traumatismo.

El síndrome de Waardenburg con frecuencia se hereda como un rasgo autosómico dominante. Esto significa que sólo uno de los padres tiene que transmitirle el gen defectuoso para que su hijo resulte afectado. Los múltiples tipos de este síndrome resultan de defectos en diferentes genes. La mayoría de las personas con esta enfermedad tiene uno de los padres que la padece, pero los síntomas en el padre pueden ser muy diferentes de los del hijo.

Los síntomas pueden abarcar labio leporino (de carácter infrecuente), estreñimiento, sordera, ojos azules extremadamente pálidos o heterocromía, piel y cabello claros, dificultad de enderezamiento total de las articulaciones y probable disminución leve de la capacidad intelectual.

En este caso la descripción física de Alejandro El Grande (se le consideraba un niño de tez clara, pelo castaño y ondulado y ojos heterocrómos) parece relacionada con este síndrome, aunque puede tratarse únicamente del cánon de belleza de la época (asociándose estos rasgos con las divinidades olímpicas). Así mismo, la dificultad de enderezamiento de las articulaciones (se sabe que tuvo algunos problemas, como Filipo II, aunque muchos expertos lo atribuyen a la gota), aunque el punto que haría tambalear más esta teoría es la disminución de la capacidad intelectual, puesto a que se le considera uno de los grandes estrategas y expansionistas de la historia, algo no apto para cualquiera.

En cuánto al síndrome de Horner, ese se basa en una diferencia muy visible del tamaño de las pupilas, dilatándose una mucho menos que la otra, siendo también distinta la posición de los párpados en el ojo afectado (el inferior es más alto y el superior más bajo, lo que hace el ojo más pequeño). Si el síndrome de Horner se desarrolla durante el primer año de vida, el iris del ojo afectado puede parecer más claro en comparación con el ojo normal (Heterocromía).

Este síndrome puede ser congénito o adquirido. El congénito resulta de un traumatismo en el cuello durante el parto, asociándose con una lesión llamada Parálisis de Klumpke (parálisis parcial de la extremidad superior, concretamente la mano y el antebrazo). Los adquiridos ocurren así mismo por un trauma en el cuello o una anormalidad en el tórax, cuello o espalda (posible causa en este caso).

Una lesión, la causa más probable

Finalmente la teoría de la lesión, la más posible. Según el Doctor Basilio A. Kotsias del Instituto de Investigaciones Médicas Alfredo Lanari,Alejandro Magno podía haber sufrido de síndrome de Brown (estrabismo en uno de los ojos al realizar la mirada patética, es decir, hacia abajo y hacia adentro) o una lesión en el cuarto par craneal, afectándose en ambos casos el músculo oblicuo menor de la cabeza. Éste actúa en la articulación atlanto-occipital, extendiendo y flexionando la cabeza hacia el mismo lado de la ubicación del músculo. Uno de los síntomas más claros de esta lesión es que la persona suele inclinar la cabeza hacia el lado donde se halla la lesión. Así se puede apreciar en algunos de los bustos y referencias que de él se han hecho, comentando Plutarco "la mirada enternecedora" o "la flexibilidad" de su mirada,e indicándose normalmente que esta tendencia era hacia la derecha.

Sin embargo, en el caso de que fuese el oblicuo mayor el afectado, el perjudicado tendería la cabeza al lado opuesto para compensar este tipo de visión, por lo que dependiendo del busto al que nos refiriéramos (por ejemplo, Lisipo, escultor personal, lo representaba con una inclinación a la izquierda) la lesión podría estar en un lado u otro de la cabeza. Esta lesión, a mi entender, podría conllevar siderosis o ciclitis. La primera se trata de depósitos de hierro sobre el iris que alteran su coloración normal. Generalmente ocurre como consecuencia de un traumatismo. La ciclitis, por otro lado, se trata de una inflamación de la cámara anterior del ojo y es una de las causas que con mayor frecuencia provoca heterocromía en el iris.

En resumen, a pesar de que la causa puede ser tanto una lesión en el oblicuo mayor o menor, derecho o izquierdo, la lesión en el músculo oblicuo menor derecho de la cabeza la más cercana, ya que podría provocarle, no únicamente la tendencia viciosa de inclinar la cabeza hacia la derecha, si no también el hecho de que ese ojo fuese el de color claro.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los Dolores de Nuestra Señora

Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Soledad, Sol, Marisol, Angustias). Santos: Nicomedes, Valeriano, Emila (Emiliano, Emilia) y Jeremías, Militina, Cirino, Serapión, Leoncio, Herculano, Máximo, Teódoto, Asclepiódoto, Nicetas, Porfirio, mártires; Silvano, Epiro, Leobino, obispos; Albino, Apro, confesores; Aicardo, abad; Rolando, ermitaño; Eutropia.

Siete son los dolores que tipifica la tradición…

0 notes

Text

Querida,

Himarë no es un destino turístico más en el mapa; es un lugar donde el tiempo se repliega y la historia se hace tangible en cada rincón, como si el pasado nunca hubiera dejado de latir bajo la superficie. Aquí, en la costa del Jónico, donde las montañas se precipitan hacia un mar que parece contener todos los secretos del mundo antiguo, uno se encuentra en un umbral, no solo entre la tierra y el agua, sino entre lo visible y lo invisible, entre lo que fue y lo que sigue siendo.

Este pequeño enclave ha sido testigo de siglos de historia, de invasiones y migraciones, de culturas que se superponen como las capas de sedimento en sus acantilados. Himarë, que una vez fue parte del dominio de la Epiro antigua, ha visto pasar a los romanos, los bizantinos, los otomanos, y cada uno de estos imperios ha dejado su huella, pero ninguno ha logrado borrar por completo el eco de las sirenas que, según se dice, aún cantan en estas aguas. En ellas no encuentro solo el peligro que advertían los mitos griegos, sino una invitación a escuchar lo que normalmente no se oye, a percibir lo que a menudo pasa desapercibido.

La hospitalidad aquí no es un mero formalismo; es un vestigio de una antigua ética, un compromiso con la apertura y el reconocimiento del otro, que ha perdurado a pesar de los cambios de poder y las fronteras fluctuantes. Me viene a la mente una reflexión sobre el poder subversivo de la hospitalidad, que en la antigüedad significaba más que un simple acto de generosidad: era una forma de establecer vínculos más allá de las jerarquías y las estructuras de poder. Acoger a un extraño era, en cierto modo, desafiar las leyes de la territorialidad y las sospechas del nacionalismo incipiente, un recordatorio de que la verdadera fuerza de un lugar reside en su capacidad para integrar, no para excluir.

En la quietud de Himarë, pienso en cómo los imperios que pasaron por aquí intentaron imponer su propia narrativa, su propio "canto de sirena", seduciendo con promesas de orden y prosperidad. Pero al final, lo que permanece no es el poder que intentaron ejercer, sino los pequeños gestos de quienes, lejos de los palacios y las murallas, mantuvieron vivo el arte de la hospitalidad, el valor de reconocer al otro como un igual, como alguien con quien se comparte una historia común.

Recuerdo una historia que escuché mientras recorría las calles estrechas de Himarë. Un pescador me contó sobre un naufragio en el que un joven marino fue arrastrado por las corrientes hasta estas costas. Herido y agotado, fue encontrado por los habitantes, quienes lo acogieron en sus hogares. No le preguntaron por su nacionalidad ni por su religión; solo vieron en él a alguien que necesitaba ayuda. En agradecimiento, antes de partir, el marinero les enseñó un antiguo canto que había aprendido en sus viajes, un canto que hablaba de la belleza oculta en los actos de bondad, de la resistencia silenciosa que teje una red invisible de humanidad a través del tiempo y el espacio.

Ese canto, me dijeron, aún se escucha en las noches cuando el viento sopla desde el mar. No es un canto que cualquiera pueda oír; solo aquellos que han aprendido a escuchar más allá de las palabras, que han descubierto el lenguaje secreto de las cosas, de las miradas compartidas, de los silencios que se llenan de sentido solo cuando dos personas han aprendido a sintonizarse con lo esencial, pueden percibirlo.

Himarë me enseña que la verdadera historia de un lugar no se encuentra en los libros ni en las crónicas oficiales, sino en estos gestos silenciosos, en la hospitalidad que se ofrece sin esperar nada a cambio, en la resistencia de lo pequeño frente a la grandilocuencia de los imperios. Aquí, lo que resuena no es el eco de las conquistas, sino el susurro de las sirenas que, a lo largo de los siglos, han aprendido a cantar en un tono más bajo, más sutil, para aquellos que están dispuestos a detenerse y escuchar.

0 notes

Video

SISIGAMBIS-ART-PINTURA-MADRE-REY-DARIO III-PERSIA-ACUARELAS-PERSONAJES-COLECCION-ALEJANDRO MAGNO-PINTOR-ERNEST DESCALS por Ernest Descals

Por Flickr:

SISIGAMBIS-ART-PINTURA-MADRE-REY-DARIO III-PERSIA-ACUARELAS-PERSONAJES-COLECCION-ALEJANDRO MAGNO-PINTOR-ERNEST DESCALS- La Reina Madre del Imperio Persa, su hijo el Rey DARIO III la abandonó en su campamento junto a las otras mujeres que formaban el Harén, ALEJANDROMAGNO la mantuvo bajo su protección personal y se estableció una relación familiar entre ambos, SISIGAMBIS acabó perdiendo a su hijo Dario asesinado por sus propios generales, Alejandro la tuvo como a su propia Madre en substitución de Olimpia que residía en Pella y más tarde en el Reino de Epiro. Cuando se produjo el desenlace de la muerte de Alejandro en Babilonia Sisigambis había perdido a sus dos hijos, el natural y el adoptado. Rostro con expresión de tristeza, el Destino golpeó dos veces. Pintura del artista pintor Ernest Descals con acuarelas sobre papel de 27 x 35 centímetros, Pintar el catálogo de personajes que rodearon al Rey de Macedonia en una amplia Colección de Arte histórico.

#SISIGAMBIS#MADRE#MOTHER#REY DE REYES#DINASTIA AQUEMENIDA#PERSIA#IMPERIO PERSA#SON#HIJO#HIJOS#CHILDREN#KING#REY#ALEJANDRO MAGNO#ALEXANDROS#MACEDONIO#MACEDONIA#MACEDONIAN#ALEXANDER THE GREAT#REINA MADRE#ADOPCION#MUERTE#DEATH#PERDIDAS#DESTINO#DESTINY#RELACION#PERSONAJES#CHARACTERS#MUJER

0 notes

Text

Conoce la vida de Amílcar Barca, el brillante padre de Aníbal

Nació en Cartago en el seno de una familia de Cirene que pertenecía a la aristocracia local. Fue el líder de los bárcidas y padre de Asdrúbal, Aníbal y Magón. Su nombre significa hermano de Melkart.

A sus 28 años mandó a las tropas cartaginesas durante la Primera Guerra Púnica entre el 247-241 a.C. Se le puso al mando de un reducido ejército de mercenarios a los que entrenó a la manera de las tropas de Alejandro Magno y Pirro de Epiro. Por entonces Cartago solo poseía dos ciudades en Sicilia. Amílcar fue capaz de mantener a raya a las tropas romanas e incluso les conquistó Érice en el 249 a.C.

La superioridad romana en el mar dejó a las tropas de Amílcar aisladas y con carencias de suministros. Cartago, debilitado, firmó la paz con Roma y el general volvió a África y se retiró de la vida pública.

Cartago quedó arruinado tras la guerra contra Roma y fue incapaz de pagar los sueldos atrasados de los mercenarios. El descontento social desembocó en la Guerra de los Mercenarios (241–238 a.C.), que asoló las tierras del Imperio cartaginés e incluso puso en riesgo la existencia del estado. El gobierno le dio a Amílcar el mando de las tropas para sofocar a los rebeldes, lo que hizo de forma exitosa.

La victoria le dio una gran fama y popularidad en Cartago. Amílcar decidió expandir el control cartaginés a Iberia para compensar las pérdidas económicas y territoriales que sufrió durante el conflicto con Roma. En el 236 a.C. desembarcó en la península Ibérica con un ejército bien entrenado.

Durante ocho años combatió, avasalló o se alió con los pueblos ibéricos y consolidó el control de Cartago sobre el territorio, beneficiándose de su abundancia de recursos. En el invierno del 229 a.C. cayó de su caballo y se ahogó, cuando perseguía a los rebeldes oretanos, después de derrotarlos, tenía 47 años. Su legado fueron sus hijos, a los que llamaba “cachorros de león, uno de los cuales, Aníbal, estaba destinado a convertirse en uno de los generales más importantes de la historia.

0 notes

Note

Hi Dr Reames!

Would you say that Macedon shared the same "political culture" with its Thracian and Illyrian neighbours, like how most Greeks shared the polis structure and the concept of citizenship?

I don't really know anything about Macedonian history before Philip II's time, but you've often brought up how the Macedonians shared some elements of elite culture (e.g. mound burials) with their Thracian neighbours, as well religious beliefs and practices.

I've only ever heard these people generically described as "a collection of tribes (that confederated into a kingdom)", which also seems to be the common description for nearby "Greek" polities like Thessaly and Epiros. So did these societies have a lot in common, structurally speaking, with Macedon? Or were they just completely different types of polities altogether?

First, in the interest of some good bibliography on the Thracians:

Z. H. Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Orpheus Unmasked. Oxford UP, 1998. (Too expensive outside libraries, but highly recommended if you can get it by interlibrary loan. Part of the exorbitant cost [almost $400, but used for less] owes to images, as it’s archaeology heavy. Archibald is also an expert on trade and economy in north Greece and the Black Sea region, and has edited several collections on the topic.

Alexander Fol, Valeria Fol. Thracians. Coronet Books, 2005. Also expensive, if not as bad, and meant for the general public. Fol’s 1977 Thrace and the Thracians, with Ivan Marazov, was a classic. Fol and Marazov are fathers of modern Thracian studies.

R. F. Hodinott, The Thracians. Thames and Hudson, 1981. Somewhat dated now but has pictures and can be found used for a decent price if you search around. But, yeah…dated.

For Illyria, John Wilkes’ The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, is a good place to start, but there’s even less about them in book form (or articles).

—————

Now, to the question.

BOTH the Thracians and Illyrians were made up of politically independent tribes bound by language and religion who, sometimes, also united behind a strong ruler (the Odrysians in Thrace for several generations, and Bardylis briefly in Illyria). One can probably make parallels to Germanic tribes, but it’s easier for me to point to American indigenous nations. The Odrysians might be compared to the Iroquois federation. The Illyrians to the Great Lakes people, united for a while behind Tecumseh, but not entirely, and disunified again after. These aren’t perfect, but you get the idea. For that matter, the Greeks themselves weren’t a nation, but a group of poleis bonded by language, culture, and religion. They fought as often as they cooperated. The Persian invasion forced cooperation, which then dissolved into the Peloponnesian War.

Beyond linguistic and religious parallels, sometimes we also have GEOGRAPHIC ones. So, let me divide the north into lowlands and highlands. It’s much more visible on the ground than from a map, but Epiros, Upper Macedonia, and Illyria are all more alike, landscape-wise, than Lower Macedonia and the Thracian valleys. South of all that, and different yet again, lay Thessaly, like a bridge between Southern Greece and these northern regions.

If language (and religion) are markers of shared culture, culture can also be shaped by ethnically distinct neighbors. Thracians and Macedonians weren’t ethnically related, yet certainly shared cultural features. Without falling into colonialist geographical/environmental determinism, geography does affect how early cultures develop because of what resources are available, difficulties of travel, weather, lay of the land itself, etc.

For instance, the Pindus Range, while not especially high, is rocky and made a formidable barrier to easy east-west travel. Until recently, sailing was always more efficient in Greece than travel by land (especially over mountain ranges).* Ergo, city-states/towns on the western coast tended to be western-facing for trade, and city-states/towns on the eastern side were, predictably, eastern-facing. This is why both Epiros and Ainai (Elimeia) did more trade with Corinth than Athens, and one reason Alexandros of Epiros went west to Italy while Alexander of Macedon looked east to Persia. It’s also why Corinth, Sparta, etc., in the Peloponnese colonized Sicily and S. Italy, while Athens, Euboia, etc., colonized the Asia Minor and Black Sea coasts. (It’s not an absolute, but one certainly sees trends.)

So, looking at their land, we can see why Macedonians and Thracians were both horse people with their wide valleys. They also practiced agriculture, had rich forests for logging, and significant metal (and mineral) deposits—including silver and gold—that made mining a source of wealth. They shared some burial customs but maintained acute differences. Both had lower status for women compared to Illyria/Epiros/Paionia. Yet that’s true only of some Thracian tribes, such as the Odrysians. Others had stronger roles for women. Thracians and Macedonians shared a few deities (The Rider/Zis, Dionysos/Zagreus, Bendis/Artemis/Earth Mother), although Macedonian religion maintained a Greek cast. We also shouldn’t underestimate the impact of Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast on inland Thrace, especially the Odrysians. Many an Athenian or Milesian (et al.) explorer/merchant/colonist married into the local Thracian elite.

Let’s look at burial customs, how they’re alike and different, for a concrete example of this shared regional culture.

First, while both Thracians and Macedonians had shrines, neither had temples on the Greek model until late, and then largely in Macedonia. Their money went into the ground with burials.

Temples represent a shit-ton of city/community money plowed into a building for public use/display. In southern Greece, they rise (pun intended) at the end of the Archaic Age as city-state sumptuary laws sought to eliminate personal display at funerals, weddings, etc. That never happened in Macedonia/much of the northern areas. So, temples were slow to creep up there until the Hellenistic period. Even then, gargantuan funerals and the Macedonian Tomb remained de rigueur for Macedonian elite. (The date of the arrival of the true Macedonian Tomb is debated, but I side with those who count it as a post-Alexander development.)

A “Macedonian Tomb” (above: Tomb of Judgement, photo mine) is a faux-shrine embedded in the ground. Elite families committed wealth to it in a huge potlatch to honor the dead. Earlier cyst tombs show the same proclivities, but without the accompanying shrine-like architecture. As early as 650 BCE at Archontiko (= ancient Pella), we find absurd amounts of wealth in burials (below: Archontiko burial goods, Pella Museum, photos mine). Same thing at Sindos, and Aigai, in roughly the same period. Also in a few places in Upper Macedonia, in the Archaic Age: Aiani, Achlada, Trebenište, etc.. This is just the tip of the iceberg. If Greece had more money for digs, I think we’d find additional sites.

Vivi Saripanidi has some great articles (conveniently in English) about these finds: “Constructing Necropoleis in the Archaic Period,” “Vases, Funerary Practices, and Political Power in the Macedonian Kingdom During the Classical Period Before the Rise of Philip II,” and “Constructing Continuities with a Heroic Past.” They’re long, but thorough. I recommend them.

What we observe here are “Princely Burials” across lingo-ethnic boundaries that reflect a larger, shared regional culture. But one big difference between elite tombs in Macedonia and Thrace is the presence of a BODY, and whether the tomb was new or repurposed.

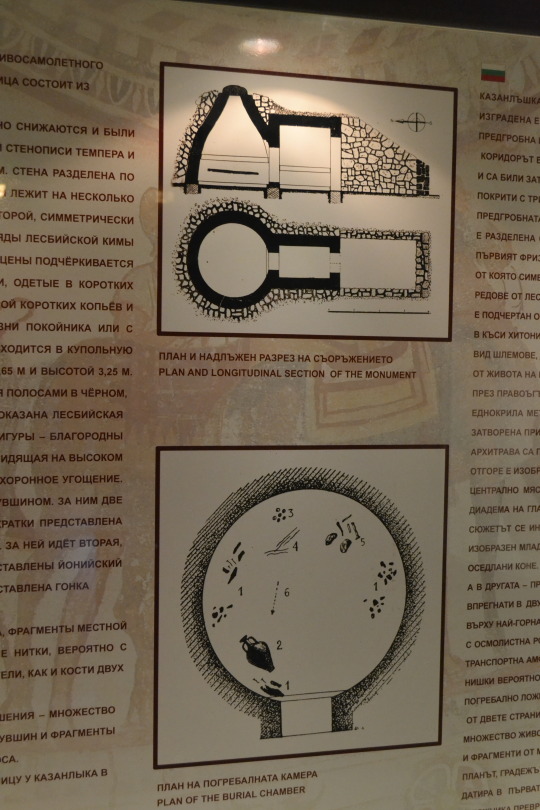

In Thrace, at least royal tombs are repurposed shrines (above: diagram and model of repurposed shrine-tombs). Macedonian Tombs were new construction meant to look like a shrine (faux-fronts, etc.). Also, Thracian kings’ bodies weren’t buried in their "tombs." Following the Dionysic/ Orphaic cult, the bodies were cut up into seven pieces and buried in unmarked spots. Ergo, their tombs are cenotaphs (below: Kosmatka Tomb/Tomb of Seuthes III, photos mine).

What they shared was putting absurd amounts of wealth into the ground in the way of grave goods, including some common/shared items such as armor, golden crowns, jewelry for women, etc. All this in place of community-reflective temples, as seen in the South. (Below: grave goods from Seuthes’ Tomb; grave goods from Royal Tomb II at Vergina, for comparison).

So, if some things are shared, others (connected to beliefs about the afterlife) are distinct, such as the repurposed shrine vs. new construction built like a shine, and the presence or absence of a body (below: tomb ceiling décor depicting Thracian deity Zalmoxis).

Aside from graves, we also find differences between highlands and lowlands in the roles of at least elite women. The highlands were tough areas to live, where herding (and raiding) dominated, and what agriculture there was required “all hands on deck” for survival. While that isn’t necessary for women to enjoy higher status (just look at Minoan Crete, Etruria, and even Egypt), it may have contributed to it in these circumstances.

Illyrian women fought. And not just with bows on horseback as Scythian women did. If we can believe Polyaenus, Philip’s daughter Kyanne (daughter of his Illyrian wife Audata) opposed an Illyrian queen on foot with spears—and won. Philip’s mother Eurydike involved herself in politics to keep her sons alive, but perhaps also as a result of cultural assumption: her mother was royal Lynkestian but her father was (perhaps) Illyrian. Epirote Olympias came to Pella expecting a certain amount of political influence that she, apparently, wasn’t given until Philip died. Alexander later observed that his mother had wisely traded places with Kleopatra, his sister, to rule in Epiros, because the Macedonians would never accept rule by a woman (implying the Epirotes would).

I’ve noted before that the political structure in northern Greece was more of a continuum: Thessaly had an oligarchic tetrarchy of four main clans, expunged by Jason in favor of tyranny, then restored by Philip. Epiros was ruled by a council who chose the “king” from the Aiakid clan until Alexandros I, Olympias’s brother, established a real monarchy. Last, we have Macedon, a true monarchy (apparently) from the beginning, but also centered on a clan (Argeads), with agreement/support from the elite Hetairoi class of kingmakers. Upper Macedonian cantons (formerly kingdoms) had similar clan rule, especially Lynkestis, Elimeia, and Orestis. Alas, we don’t know enough to say how absolute their monarchies were before Philip II absorbed them as new Macedonian districts, demoting their basileis (kings/princes) to mere governors.

I think continued highland resistance to that absorption is too often overlooked/minimized in modern histories of Philip’s reign, excepting a few like Ed Anson’s. In Dancing with the Lion: Rise, I touch on the possibility of highland rebellion bubbling up late in Philip’s reign but can’t say more without spoilers for the novel.

In antiquity, Thessaly was always considered Greek, as was (mostly) Epiros. But Macedonia’s Greek bona-fides were not universally accepted, resulting in the tale of Alexandros I’s entry into the Olympics—almost surely a fiction with no historical basis, fed to Herodotos after the Persian Wars. The tale’s goal, however, was to establish the Greekness of the ruling family, not of the Macedonian people, who were still considered barbaroi into the late Classical period. Recent linguistic studies suggest they did, indeed, speak a form of northern Greek, but the fact they were regarded as barbaroi in the ancient world is, I think instructive, even if not necessarily accurate.

It tells us they were different enough to be counted “not Greek” by some southern Greek poleis and politicians such as Demosthenes. Much of that was certainly opportunistic. But not all. The bias suggests Macedonian culture had enough overflow from their northern neighbors to appear sufficiently alien. Few Greek writers suggested the Thessalians or Epirotes weren’t Greek, but nobody argued the Thracians, Paiones, or Illyrians were. Macedonia occupied a liminal status.

We need to stop seeing these areas with hard borders and, instead, recognize permeable boundaries with the expected cultural overflow: out and in. Contra a lot of messaging in the late 1800s and early/mid-1900s, lifted from ancient narratives (and still visible today in ultra-national Greek narratives), the ancient Greeks did not go out to “civilize” their Eastern “Oriental” (and northern barbaroi) neighbors, exporting True Culture and Philosophy. (For more on these views, see my earlier post on “Alexander suffering from Conqueror’s Disease.”)

In fact, Greeks of the Late Iron Age (LIA)/Archaic Age absorbed a great deal of culture and ideas from those very “Oriental barbarians,” such as Lydia and Assyria. In art history, the LIA/Early Archaic Era is referred to as the “Orientalizing Period,” but it’s not just art. Take Greek medicine. It’s essentially Mesopotamian medicine with their religion buffed off. Greek philosophy developed on the islands along the Asia Minor coast, where Greeks regularly interacted with Lydians, Phoenicians, and eventually Persians; and also in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they were talking to Carthaginians and native Italic peoples, including Etruscans. Egypt also had an influence.

Philosophy and other cultural advances didn’t develop in the Greek heartland. The Greek COLONIES were the happenin’ places in the LIA/Archaic Era. Here we find the all-important ebb and flow of ideas with non-Greek peoples.

Artistic styles, foodstuffs, technology, even ideas and myths…all were shared (intentionally or not) via TRADE—especially at important emporia. Among the most significant of these LIA emporia was Methone, a Greek foundation on the Macedonian coast off the Thermaic Gulf (see map below). It provided contact between Phoenician/Euboian-Greek traders and the inland peoples, including what would have been the early Macedonian kingdom. Perhaps it was those very trade contacts that helped the Argeads expand their rule in the lowlands at the expense of Bottiaians, Almopes, Paionians, et al., who they ran out in order to subsume their lands.

My main point is that the northern Greek mainland/southern Balkans were neither isolated nor culturally stunted. Not when you look at all that gold and other fine craftwork coming out of the ground in Archaic burials in the region. We’ve simply got to rethink prior notions of “primitive” peoples and cultures up there—notions based on southern Greek narratives that were both political and culturally hidebound, but that have, for too long, been taken as gospel truth.

Ancient Macedon did not “rise” with Philip II and Alexander the Great. If anything, the 40 years between the murder of Archelaos (399) and the start of Philip’s reign (359/8) represents a 2-3 generation eclipse. Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos were extremely capable kings. Philip represented a return to that savvy rule.

(If you can read German, let me highly recommend Sabine Müller’s, Perdikkas II and Die Argeaden; she also has one on Alexander, but those two talk about earlier periods, and especially her take on Perdikkas shows how clever he was. For those who can’t read German, the Lexicon of Argead Macedonia’s entry on Perdikkas is a boiled-down summary, by Sabine, of the main points in her book.)

Anyway…I got away a bit from Thracian-Macedonian cultural parallels, but I needed to mount my soapbox about the cultural vitality of pre-Philip Macedonia, some of which came from Greek cultural imports, but also from Thrace, Illyria, etc.

Ancient Macedonia was a crossroads. It would continue to be so into Roman imperial, Byzantine, and later periods with the arrival of subsequent populations (Gauls, Romans, Slavs, etc.) into the region.

That fruit salad with Cool Whip, or Jello and marshmallows, or chopped up veggies and mayo, that populate many a family reunion or church potluck spread? One name for it is a “Macedonian Salad”—but not because it’s from Macedonia. It’s called that because it’s made up of many [very different] things. Also, because French macedoine means cut-up vegetables, but the reference to Macedonia as a cultural mishmash is embedded in that.

---------------

* I’ve seen this personally between my first trip to Greece in 1997, and the new modern highway. Instead of winding around mountains, the A2 just blasts through them with tunnels. The A1 (from Thessaloniki to Athens) was there in ’97, and parts of the A2 east, but the new highway west through the Pindus makes a huge difference. It takes less than half the time now to drive from the area around Thessaloniki/Pella out to Ioannina (near ancient Dodona) in Epiros. Having seen the landscape, I can imagine the difficulties of such a trip in antiquity with unpaved roads (albeit perhaps at least graded). Taking carts over those hills would be daunting. See images below.

#asks#ancient Macedonia#ancient Thrace#ancient Epiros#ancient Thessaly#Argead Macedonia#pre-Philip Macedonia#Late Iron Age Greece#Archaic Age Greece#Thracian tombs#Macedonian tombs#Classics#tagamemnon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#women in ancient Macedonia#ancient Illyria#women in Illyria#Macedonian-Thracian similarities#religion in ancient Thrace#religion in ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

¡Hola, buenos días, humanidad! 🌍 ¡Feliz miércoles! 💪🌟🚀🏆🌈📈🌱🌞🎯🌺 Hoy os dejo la foto de Parga, una pintoresca ciudad costera en la región de Epiro, Grecia, que cautiva con su belleza natural y su encanto histórico. Anidada entre colinas cubiertas de olivos y bañada por aguas cristalinas del mar Jónico, Parga ofrece una mezcla única de playas impresionantes y callejuelas empedradas llenas de boutiques y tabernas. El Castillo de Parga, coronando una colina sobre la ciudad, cuenta con una rica historia que abarca desde el Imperio Bizantino hasta la ocupación veneciana. Una curiosidad fascinante es que la isla de Panagia, frente a la costa de Parga, alberga una capilla pintoresca construida en la roca y accesible solo por barco. Esta ciudad griega logra fusionar su rica herencia con la serenidad del mar, creando un destino verdaderamente encantador.

Para tener en cuenta...

Un día te darás cuenta de que la felicidad nunca se trató de tu trabajo, tu título o estar en una relación. La felicidad nunca fue seguir los pasos de quienes vinieron antes que tú; nunca fue ser como los demás. Un día, lo verás: la felicidad siempre fue sobre el descubrimiento, la esperanza, escuchar a tu corazón y seguirlo a donde quisiera ir. Siempre se trató de ser amable contigo mismo; siempre fue abrazar a la persona que estabas llegando a ser. Un día entenderás que la felicidad siempre fue aprender a vivir contigo mismo, que tu felicidad nunca estuvo en manos de los demás. Siempre fue acerca de ti. Siempre fue…

1 note

·

View note

Text

Apara Apare Apari Aparo Aparu Apary Apera Apere Aperi Apero Aperu Apira Apire Apiri Apiro Apiru Apiry Apora Apore Apori Aporo Aporu Apory Apura Apure Apuri Apuro Apuru Apury Apyra Apyre Apyri Apyro Apyru Apyry Arapa Arape Arapi Arapo Arapu Arapy Arepa Arepe Arepi Arepo Arepu Arepy Aripa Aripe Aripi Aripo Aripu Aripy Aropa Arope Aropi Aropo Aropu Aropy Arupa Arupe Arupi Arupo Arupu Arupy Arypa Arype Arypi Arypo Arypu Arypy Epara Epare Epari Eparo Eparu Epary Epera Epere Eperi Epero Eperu Epery Epira Epire Epiri Epiro Epiru Epiry Epora Epore Epori Eporo Eporu Epory Epura Epure Epuri Epuro Epuru Epury Epyra Epyre Epyri Epyro Epyru Epyry Erapa Erape Erapi Erapo Erapu Erapy Erepa Erepe Erepi Erepo Erepu Erepy Eripa Eripe Eripi Eripo Eripu Eripy Eropa Erope Eropi Eropo Eropu Eropy Erupa Erupe Erupi Erupo Erupu Erupy Erypa Erype Erypi Erypo Erypu Erypy Ipara Ipare Ipari Iparo Iparu Ipary Ipera Ipere Iperi Ipero Iperu Ipery Ipira Ipire Ipiri Ipiro Ipiru Ipiry Ipora Ipore Ipori Iporo Iporu Ipory Ipura Ipure Ipuri Ipuro Ipuru Ipury Ipyra Ipyre Ipyri Ipyro Ipyru Ipyry Irapa Irape Irapi Irapo Irapu Irapy Irepa Irepe Irepi Irepo Irepu Irepy Iripa Iripe Iripi Iripo Iripu Iripy Iropa Irope Iropi Iropo Iropu Iropy Irupa Irupe Irupi Irupo Irupu Irupy Irypa Irype Irypi Irypo Irypu Irypy Opara Opare Opari Oparo Oparu Opary Opera Opere Operi Opero Operu Opery Opira Opire Opiri Opiro Opiru Opiry Opora Opore Opori Oporo Oporu Opory Opura Opure Opuri Opuro Opuru Opury Opyra Opyre Opyri Opyro Opyru Opyry Orapa Orape Orapi Orapo Orapu Orapy Orepa Orepe Orepi Orepo Orepu Orepy Oripa Oripe Oripi Oripo Oripu Oripy Oropa Orope Oropi Oropo Oropu Oropy Orupa Orupe Orupi Orupo Orupu Orupy Orypa Orype Orypi Orypo Orypu Orypy Ratas Rates Ratis Ratos Ratus Ratys Retas Retes Retis Retos Retus Retys Ritas Rites Ritis Ritos Ritus Ritys Rotas Rotes Rotis Rotos Rotus Rotys Rutas Rutes Rutis Rutos Rutus Rutys Rytas Rytes Rytis Rytos Rytus Rytys Satar Sater Satir Sator Satur Satyr Setar Seter Setir Setor Setur Setyr Sitar Siter Sitir Sitor Situr Sityr Sotar Soter Sotir Sotor Sotur Sotyr Sutar Suter Sutir Sutor Sutur Sutyr Sytar Syter Sytir Sytor Sytur Sytyr Tanat Tanet Tanit Tanot Tanut Tanyt Tenat Tenet Tenit Tenot Tenut Tenyt Tinat Tinet Tinit Tinot Tinut Tinyt Tonat Tonet Tonit Tonot Tonut Tonyt Tunat Tunet Tunit Tunot Tunut Tunyt Tynat Tynet Tynit Tynot Tynut Tynyt Upara Upare Upari Uparo Uparu Upary Upera Upere Uperi Upero Uperu Upery Upira Upire Upiri Upiro Upiru Upiry Upora Upore Upori Uporo Uporu Upory Upura Upure Upuri Upuro Upuru Upury Upyra Upyre Upyri Upyro Upyru Upyry Urapa Urape Urapi Urapo Urapu Urapy Urepa Urepe Urepi Urepo Urepu Urepy Uripa Uripe Uripi Uripo Uripu Uripy Uropa Urope Uropi Uropo Uropu Uropy Urupa Urupe Urupi Urupo Urupu Urupy Urypa Urype Urypi Urypo Urypu Urypy Ypara Ypare Ypari Yparo Yparu Ypary Ypera Ypere Yperi Ypero Yperu Ypery Ypira Ypire Ypiri Ypiro Ypiru Ypiry Ypora Ypore Ypori Yporo Yporu Ypory Ypura Ypure Ypuri Ypuro Ypuru Ypury Ypyra Ypyre Ypyri Ypyro Ypyru Ypyry Yrapa Yrape Yrapi Yrapo Yrapu Yrapy Yrepa Yrepe Yrepi Yrepo Yrepu Yrepy Yripa Yripe Yripi Yripo Yripu Yripy Yropa Yrope Yropi Yropo Yropu Yropy Yrupa Yrupe Yrupi Yrupo Yrupu Yrupy Yrypa Yrype Yrypi Yrypo Yrypu Yrypy

1 note

·

View note

Text

#uae#dubai#abudhabi#mydubai#dubailife#dxb#sharjah#kuwait#usa#bahrain#oman#qatar#ksa#emirates#fashion#love#dubaimall#saudiarabia#ajman#burjkhalifa#travel#photography#dubaifashion#india#uk#alain#instagram#expo#instagood#dubaimarina

0 notes

Text

NU ARTS AND COMMUNITY 2023: IRRINUNCIABILI PIACERI AUTUNNALI

La maratona di “Nu Arts and Community” festival di arti visive, danza, musica e molto altro che si tiene a Novara nel mese di settembre, è iniziata in una uggiosa sera uggiosa alla Galleria Giannoni, nel cui ingresso si era riunita una decina, o poco più, di anziani (pensandoci bene anche chi vi scrive è anagraficamente “un anziano”) in attesa di essere introdotti nelle sale della Galleria. Ad attenderli una giovane donna stesa a terra con il volto coperto da una sfera di acciaio. Intorno a lei, cosparsi sul parquet di diverse sale alcuni amplificatori che trasmettevano una trasmissione radiofonica con interviste a birdwatchers e naturalisti, intenti a raccontare “di nidificazioni e migrazioni dei volatili delle zone umide”. Beh, devo ammettere che, detto così, tutto possa sembrare molto surreale, ed in effetti lo era e lo è diventato molto di più quando il corpo di Marta Bellu del Collettivo Trifoglio/Iride ha ripreso vita e ha cominciato a muoversi sinuosamente in una danza liberamente ispirata ai suoni e ai movimenti della natura, se così possiamo semplificare. Il corpo, in dialettico rapporto con le sfere e le semisfere di acciaio disseminate nelle sale, si contorce lentissimamente, si avviluppa su sé stesso, rotea, striscia, si modella su stipiti e pareti, come un’alga su una roccia, si flette e si piega come una una chioma al vento. Ha un aspetto multiforme e poetico la natura che passa “attraverso” il corpo della incredibile Marta Bellu. Il silenzio delle sale ove sono esposte tele di marine e paesaggi ottocenteschi, è rotto solo dal fruscio del corpo della danzatrice e dai sommessi rumori elettronici di fondo di Donato Epiro, illuminato dalla luci di Andrea Sanson. Il pubblico anziano e un po’ meno anziano, sembra ipnotizzato e rapito, il pubblico giovane (ovviamente) non c’è. La performance termina con Marta in piedi, appoggiata accanto allo scalone della Galleria in un momento di meditazione profonda e di defaticamento. Gli applausi scrosciano e Marta interroga i più anziani che si rivelano essere pubblico attento e curioso. Fa parte della meraviglia di questo festival, unico nel suo genere, il saper coinvolgere “fette di città”, spesso lontane da questi eventi. Seconda parte della serata al Conservatorio “Cantelli” per la musica elettronica soft di Vittorio Montalti e “Blow Up Percussion” per “The Smell of Electricity”. Giochi di luce un po’ sacrificati a causa della serata piovosa e della location di emergenza all’interno del Conservatorio. L’elettronica di Vittorio Montalti è di quelle con cui si può stringere un patto di non belligeranza, poiché non è invasiva, potremmo azzardare quasi quasi un “dolce”, pur se con qualche bella citazione della rumoristica industriale alla Einsturzende Neubauten. Magnifico l’apporto delle percussioni elettroniche, gong, piatti ed oggettistica di Flavio Tanzi che sulla parte sinistra della scena divide idealmente il palco con la parte destra occupata dalle diavolerie elettroniche di Vittorio Montalti. Una piacevole cavalcata in una elettronica quasi vellutata, ricca di tante suggestioni ma non opprimente ed eccessivamente “noise”. Restate connessi…

0 notes