#For real though where does True Federal’s budget come from?

Text

There is a problem with looking at so many mobile suit designs in that you can wander quite far sometimes. Sometimes to odd places. For instance, I’ve been wanting to watch Gundam Narrative recently, but ended up watching Gundam Twilight Axis instead (they have a similar plot to me). Twilight Axis has the Tristan, a derivative of the Alex. Another derivative of the Alex would be the Full Armour Alex, which appears along with the Striker Custom in Mobile Suit Gundam Katana.

I’m gonna get two things out of the way first: I haven’t finished reading Gundam Katana, because I don’t like Gundam Katana.

Oh, the arts wonderful and I like a lot of the original mechanics, but I absolutely despise the protagonist (the plot’s not great but it’s essentially a blip compared to how much the main character bothers me).

I don’t want this to be just a rant post so I’ll be brief; The Protagonist of Gundam Katana, Ittou Tsurugi, is a prick. In that way that only a brat with a silver spoon in their mouth (on in this case, at their side) can be. He’s handed a super custom ms and a force of followers that follow him absolutely, despite the fact that he has no experience with command (and more to the point, no experience with failure). In addition, he’s also got those bad reader self-insert characteristics (always in the right, excels at everything he strives to do, knows things that he probably shouldn’t at that point in time). Two examples I just want to call out, the first being when he gets mugged at the docks by a group of five. The muggers attempt to justify their behaviour because of the ongoing economic depression and the claim that the Earth Federation spends more on its military than on other things. Ittou defeats them easily (fair enough), but then has the gall to turn around to them and say that they should work harder because of the recession. Ittou, a military brat, heir to his household and with a legion of followers to cater to his every need. The second example is that after fighting Zeon Remnants on the Moon (which is a whole other thing), Ittou has a chance encounter at the flight terminal with none other than Quattro Bajeena, who’s on the moon on business. Now, Quattro’s real identity in Zeta eventually became an open secret within the AEUG until Char’s Dakar Address. However, many members of the AEUG suspect Char’s real identity (Blex), fought against him in the OYW (Bright) or eventually hear enough rumours that they suspect anyway (everyone else). Ittou has never met Char, never seen Char so there is no reason as to why he should be able to recognise someone who fought with a mask throughout the entire One Year War. But he does, because he’s apparently just that good. (As an aside, the whole deification of Char post-OYW as this ace of aces bothers me a little, since he’s only really relevant to the White Base crew and there were plenty of other aces running around. It makes sense post-Dakar and post-Gryps, but prior he should be just another ace).

Anywho, the reason I wanted to talk about Katana is because I like quite a lot of it’s original mechanics. I say original, because it uses a lot of units that were originally from videogames, so I’m only going to be talking about the Striker Custom, Full Armour Striker Custom, Full Armour Alex and GM Striker Custom.

The Striker Custom is the main mobile suit of the series (and yes, I did choose that second picture to show off its weaponry). It’s probably my weakness for close-quarters suits talking, but I really like it. It is essentially a GM Striker with a Gundam Head and new backpack, but as custom units go I find that honestly quite charming. Despite the two pictures shown here it’s actually quite well-armed, starting with the standard Vulcan guns and twin beam sabers. Following this it has a further two beam sabres, snazzier ones with a longer blade, that can be combined into a beam naginata. It is also armed with a set of Knuckle Daggers, mounted on the backpack when not in use, which are essentially a sort of axe-shaped beam blade mounted in the hands (they can be seen in the second picture). It can also be armed with the Spark Knuckle (essentially an electrified, handheld brass knuckle, based on the electrical weaponry Zeon used) and the Burst Knuckle (punch to attach mine, punch again to detonate, because there’s totally no way for that to go wrong). It can also be armed with a 100mm machine gun (or as GBO2 is wont to, a GM II Beam Rifle), but typically isn’t, because Ittou’s a lousy shot. I really like the knuckle daggers - I don’t really think that they’d be more practical than a beam saber (longer reach and all), but they are cool as heck, giving the suit a boxing vibe that I quite enjoy. The Spark and Burst knuckles are typically used sparingly, which helps my opinion of them - the spark knuckle’s lovely, but there isn’t much defence against electric weaponry other than range, so it’s good it doesn’t get overused. The Burst Knuckle…. I don’t dislike it, it just seems horribly impractical. That said, I can only really recall it being used once, so it’s not like I typically remember it. The Striker Custom is also fitted with a “Demon Blade” AI System, a derivative of the EXAM system (*shot*), whiiiiich…… is fine? It’s probably the fact that I stopped reading before it became a major factor (I remember it being introduced, but little else) but I don’t really have a big opinion on it. It makes sense for a close-quarters suit to have it, especially as a trump card to pull out in dire situations. It’s more of the “can be mastered” system than the “WILL mess you up” one though (the original EXAM system was pretty harrowing, as I understand it and the HADES aren’t exactly a nice walk in the park either).

Form and armour wise, it’s pretty good. A large part of that is going to be inherited from the GM striker, yes, but the Striker Custom feels very agile, and light on its feet. It probably is the boxer influence (even the head looks like it’s got a head guard on), but I like it because it feels like a very straightforward design - get close and hit things. Specifically, I like how it feels like a “gundam-ified” version of the GM Striker in the same vein that the Gundam Marine Type “Gundiver” is to the Aqua GM. It really sets your mind going as to what other “upgraded GM’s” there could be (like a Gundam Night Seeker, or Gundam Guard Type). I’m fine with the colours - I typically dislike it if a protagonist suit is “just” white and blue, but in this case it’s actually got a purpose because the main rival suit, the Full Armour Alex, is Red, so it shows the contrasting personalities of their pilots (and it works pretty well with its pink beam weapons). I will admit that I’ve repainted it to Titans Colours in GBO2 though - it’s about the right time period for them to be around (some even show up in the early chapters) and honestly I like imagining the AEUG stealing one (plus, I think it looks really nice).

Now if only it had a better pilot.

It’s upgraded form is the Full Armour Striker Custom, build with spare parts from the Full Armour Alex. Cards on the table, I haven’t read up to the part in the manga where this shows up, so this is purely on the design and it’s weaponry (as seen in GB02). I do like the bulkier look (the original has a nice agility to the design, but I don’t mind the additional weight), however I do think that it’s overarmed. This is a common problem I have with Full Armour upgrades - they just cram a bunch of additional weaponry on for the sake of it. I like heavily armed suits, but just adding bulk to an existing design doesn’t work for me because the end result just ends up looking sluggish. Speaking of those armaments, let’s run down the list, shall we? The Vulcan Guns remain, as per usual. As do the twin beam sabers, though one of them has been moved to the front of the right shoulder. The Knuckle Daggers are now mounted in the…. What is a apparently supposed to be a shield, but looks to me more like a weapons rack on the left arm. There’s an EXAM unit 3-style double beam cannon as it’s primary ranged armament on the right arm - that’s essentially standard armament for FA (Full Armour) Units, so absolutely no issues there. It’s also got a back rocket cannon and chest missile bays, likely modelled after the regular FA Gundam, and rounding out the loadout is a set of missile pods on the legs. In addition to all this, it’s armed with a brand new sword weapon called Fukusaku - a long sword roughly three-fifths the size of the mobile suit itself. I find it to be a textbook case of a mobile suit being overarmed. I can see how - the striker custom brings its close quarters weaponry and the FA Gundam Brings its long-range weaponry, but it just seems to be fighting for space on the suit - the Beam Saber on the front armour (a very dangerous position, given what happens to beam sabers when they’re shot) and the “shield” that’s essentially mounting two especially large beam sabers on the left arm are just the most obvious examples. Fukusaku is odd, because it looks completely unique, and all the sources I can find state that it’s a cold saber - essentially an electric saber, typically used when stealth is required, such as on the Efreet Nacht. Thing is, it looks to be an mobile suit sized Katana, meaning it was forged, but it still has beam effects over the…… Hamon? Of the sword (that wavy bit on katanas that’s formed as the sword cools). Oddities aside, it makes sense that the main suit in “Mobile Suit Gundam Katana” would recieve a fancy katana, but it doesn’t exactly help with the suit having two other paired melee weapons already. I do like the bulk added by the additional armour to the Full Armour Striker Custom, it creates the sense of a slower, more methodical fighting style (“one strong cut” to the striker custom’s barrage of punches), but I think the weapons weigh it down too much, especially since I know it’s going to be used in space. Honestly, I feel like if you took off the Knuckle Daggers and Chest Missile Bays, maybe moved the saber mountings around, it’d look much better. I like the splash of purple added in the paint scheme, but I don’t notice it’s absence much in GBO2. The Full Armour Striker Custom’s design is busier (especially around the chest), so it doesn’t look quite as good in Titan’s colours, but there’s some lovely details on the back (like the leg thrusters) that really pop.

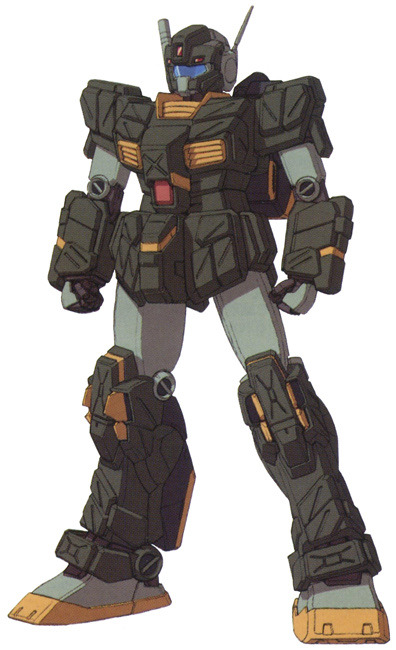

The GM Striker and GM Striker Kai are largely identical, save for the backpack. Indeed, the Striker Custom is essentially a modified GM Striker Kai (with perhaps a little of the blue destiny units sprinkled in). They are armed differently however, with the GM Striker Kai being armed with beam sabers like the ones the Striker Custom has, and the regular GM Striker being armed with a twin beam spear that can convert into a scythe. I like the regular GM Striker, I think it’s an excellent up-armoured version of the GM, with the twin beam spear being an appropriately imposing melee weapon for it. I very much like the colours as well, with a lovely green, yellow and blue-grey scheme. The blue visor also draws attention nicely to the head. The GM Striker Kai is the space-use version, having the backpack of the Striker Custom in addition to its weaponry. Overall, I think it’s a nice GM unit with the additional armour doing a lot to distinguish it from the pack.

Lastly, the Full Armour Alex. I found it quite difficult to find a decent picture of the Version seen in Gundam Katana. The Full Armour Alex is…. a little of an odd one for me, because though I know it’s just differing artist interpretations, I tend to consider the original (Green and White, right) and the version seen in Gundam Katana (Red, Left) as separate designs (for the most part). I’ll go over the one seen in Gundam Katana first. It’s piloted by Kotetsu, a cyber-Newtype of True Federal in the series (True Federal have a vested interest in having as many newtypes on their side as possible, but they don’t seem to be going for the inhuman experimentation that the Titans did.) who functions as an early, personal foe for Ittou, here to drop subtle hints about the organisation and provide an actual challenge. The Full Armour Alex is essentially a brute - it’s got the strength and power to easily match most anything else in one-on-one combat, and functions as True Federal’s one-man clean-up crew. I think it’s used well in the series - it’s a FA unit, with lots of weaponry that’s geared towards ranged combat - a natural counter to the Striker Custom, which focuses on close-quarters. It spends much of its initial appearance holding Ittou back by sheer volume of fire alone - he’s forced to do little else but dodge. But it’s meaty firepower never allows it to feel unthreatening.

Design-wise….. it’s just fine. I like the red colour scheme in the context of their pilots - Kotetsu’s far more emotion-driven than Ittou, so it makes sense for their contrasting personalities. But in the context of red mobile suits in Gundam….. it doesn’t work. Red is a signifier of Char, or something related to Char (or a char clone), but the Full Armour Alex is neither. I have been seeing some “regular” rivals using it as of late (see the Pixy (LA), but in those cases it just comes off as forced. It’s just red because it’s a rival and rivals are red. The form and body’s fine - it’s a good example of the artist’s style and the muted colours really mean your attention’s drawn to the knees, skirt, head and gun. As a full armour unit, it doesn’t get many dynamic melee shots, so it’s imposing and weighty stature helps it look imposing, particularly the back rocket cannon and it’s targeting camera.

However, I must confess I completely prefer the Original (Green and White) design, as featured in Mobile Suit Gundam 0080 MSV. It just feels so much sleeker and faster, selling that the NT-1 is an improvement over the original Gundam. The green and white colour scheme is still eye catching, clearly drawing a distinction between the original and its additional parts, while helping to sell just how protective the armour would be, since the parts of the original Alex peeking through help emphasise just how beefed-up it is. Furthermore, you can easily believe that there’s space in the armour for the chest missile bays, without significantly compromising its protection. It’s only got two other integrated weapons - the back rocket cannon and the twin beam cannon, but it feels like an appropriate amount of additional firepower. It feels significant, since they’re both clearly visible on the design and the grey plays off the rest of the colour scheme - there’s only a few other small details, like the collar and “ribs”. The Full Armour Alex does retain its built-in arm gatlings, but they cannot be used since the armour covers them. I think the fact that the armour doesn’t cover the leg thrusters, and has dedicated gaps for the AMBAC system are why it feels so much sleeker to me - the Full Armour Alex was intended to be a backup plan for the Chobham Armour, and looking at it it might have even been more agile. I also very much like the head - I assume it was just artist interpretation, or perhaps the NT-1’s design hadn’t been finalised when it was made, but the yellow eyes, red forehead jewel and sleeker face really appeal to me, while helping it have its own identity other than “just the Alex, but bigger”. It’s just really rather neat.

#gundam#ramblings#Mobile Suit Gundam Katana#Gundam Striker Custom#Full Armour Striker Custom#Full Armour Gundam#Full Armour Alex#Full Armour Gundam NT-1 Alex#GM Striker#GM Striker Kai#For real though where does True Federal’s budget come from?#Fancy ships and prototypes aren’t cheap and the eventually pull out the freaking GP02

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

last vote

This may be your last chance to vote in a real election.

Here is something that most people don’t know. According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), about 1.5% of all males are psychopaths and about 4% are sociopaths. A psychopath is defined as a person who is born with zero empathy, and thus sees all people as just objects to be used. Sociopaths on the other hand also have no empathy but are made that way growing up, and so do mostly petty crimes.

So if you combine the two we have 6 million Americans who have no empathy, but that gets worse because this is on a scale from the lowest empathy to the highest and there are another 10 million Americans who have little to no empathy or caring for others outside the people they know. They are antisociety.

This 16% of Americans, believe it or not, is fairly normal, but in the last 40 years the number of Americans who only care about their family and friends has grown to well over 100 million Americans, a third of America!!! They are now the Radical Right, Trump cult. If this doesn’t shock you then maybe you have become one of the 100 million who are antisociety.

Why is that, and why have we become so divided? The answer is simple; we have been divided on purpose.

One Australian study found that 1 in 5, 20%, of corporate CEOs and lawyers are psychopaths! Other studies now show that when most people become wealthy they lose their caring for anyone outside their circle, So today 75% of the wealthy have no feeling or caring for anyone outside their circle. Thus they are antisociety in general, and many, 20% to 50%, are psychopaths. In other words this group of rich people don’t care if you live or die, and most would kill you if you stood between them and their money.

There are around 600 billionaires in the US, and if just 20% are psychopaths or sociopaths, which is easily true, we are talking about at least 100+ billionaires who would love to take control of the US, and do not care who they hurt doing it. With their billions they could easily create a secret group which would have all the money they would ever need to pay for subversion, propaganda, or anything else they needed to divide us. Guess what, that is just what is happening.

A large group of sociopathic billionaires, which the New York Times thinks may be around 400 members, has started a secret group who’s major goal is to take as much control of America as they can, and turn it into an oligarchy, where only they can vote. Because they have kept what they are doing a secret, what is going on has only started to come to light in the last ten years.

We now know that the head of this subversive organization is Charles

Koch, CEO of Koch industries. He has an annual income of 110 billion, according to Forbes. His Father was cofounder of the John Birch Society, in the 1950s, and before starting the John Birch Society he wrote a 30 page anti communism booklet, which contained a way that the US could be taken over. It was poorly thought out, but his two sons are now using the writings of Vladimir Lenin to try and do it for real. The John Birch Society is the most radical right wing organizations in American history, and was condemned by the Republican Party at the time, but all of their radical ideology has now become main steam Republican ideology, through the uses of propaganda and subversion.

At minimum 75%+ of Republicans are now as radical right wing as they can get. They hate society, government, blacks, gays, Unions etc., and think they should have total free will, to hell with the other 320 million Americans.

Some of the first members of the Koch organization were Richard Mellon Scaife, heir to the Mellon Banking and Gulf Oil; Harry and Lynde Bradley, defense contracts; John M. Olin, chemical and munitions Companies; Coors brewing family, and the DeVos family of Amway marketing.

I call them the Oligarchy because that is what they are trying to do, become the Oligarchy over the US, where only the wealthy can vote, and the 4 keys to subversion they use are Fear, Intimidation, Distraction, and Division. It has worked. We now are more divided than ever, in the whole of our history.

The Oligarchy budgeted 800 million to buy the president in the 2016 campaign, and every republican presidential candidate, except Donald Trump, had signed on and pledged allegiance to the oligarchy. Yes, literally signed a contract. Donald Trump used his own money to get elected by creating a cult following, just like Adolf Hitler did in Germany, and Benito Mussolini did in Italy. The oligarchy denounced Trump during the campaign, but once he got elected they made a deal with him to use members of the oligarchy in his cabinet.

Trump keeps saying he will be president for 12 more years. Where is he getting that? The president is term limited to 8 years and he has already had 4. I speculate that it may be part of the deal. Once they take control of the US he gets to have 12 more years.

So, for the past 4 years the Koch oligarchy has been setting up the US from the inside of the government to take control of it. Including packing the courts with their Judges, all trained at the Federalists Society, which is an oligarchy sponsored foundation for Lawyers.

Between 2015 to 2017 Mitch McConnell refused to seat any of Obama’s 100+ federal judges, including Merrick Garland for the Supreme Court. Then when Trump was elected McConnell quickly filled all the seats with Federalist Society Judges.

Keep in mind that it was the Radical Right Bolshevik party that took over Russia in the 1920s, and made Vladimir Lenin their leader. It was the Radical Right fascist party that took over Italy in 1922, and made Benito Mussolini their leader. It was the Radical Right Nazi party that took over Germany in 1933, and made Adolf Hitler their leader, it was the Radical Right Red Guard

that took over China in 1966, and made Mao Zedong their leader, and the list goes on. It is always the Radical Right that takes over a country and turn the country into an authoritarian government, and that is now happening in the US. It looks like it is our turn; the US now has a Radical Right that would rival any of these.

The best-documented book on the Koch’s and their syndicate, and how secretive they are, comes from an investigative reporter of the New York Times, Jane Mayer. Her book is called “Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right.”

Another book that shows, beyond any doubt, what the Koch syndicate is trying to do comes from Nancy MacLean, a social historian, who stumbled across a large stash of secret documents left behind after the death of a member of the Koch syndicate. Her book, after going though these secret files, is called “Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America.”

If you want to know more about how Trump created a cult following read: “The Cult of Trump” by Steven Hassa. Dr. Hassa is a psychologist who studies cults. He got started because when he was a young man in college he got sucked into a Cult, and has first hand knowledge of how they work.

Too many Americans live in the illusion that it can’t happen here, but it absolutely can and is. If you refuse to believe that this is true you had better open your eyes, and do some research. Before you say this is hype you should at least read Nancy MacLean’s book. I can guarantee you that if they get control of the US your civil rights will be gone, and the first things they will do will be to ban all guns and get rid of anyone who is a threat to the government.

Today the Koch syndicate is well over 100 think tanks whose main goal is to take controls of America. Most of these foundations are charitable foundations on the surface, but in the basement is a large staff that does nothing but look for ways to subvert, radicalize, and divide American Democracy.

The more divided we become, the more control they have. They can use the Electoral College to their advantage, and that is how Trump got elected; this is why we are so divided, it is on purpose. The Oligarchy now literally owns just about every Republican in the House and Senate, who does just as they are told. Their only allegiance is to the Republican Party, and it is 100% controlled by the oligarchy.

If Trump gets reelected, and that is very likely because of the oligarchies use of voter suppression, and use of the Electoral College, it will be all over, the end of American Democracy. Because by the end of his next term they will have massed so much control working from inside the government that there will be no turning back, and I’m betting if this happens the US will split up because the blue states won’t cooperate with an authoritarian government, and the world’s longest standing constitution will melt away.

The reason Trump was able to con so many people is because they where set up before hand by the propaganda coming from the Koch syndicate, which, as I said, is a spin off of the John Birch Society, which had a surge of

membership in 2010. So, you better wake up as to what is really going on or the US will become an oligarchy where only the rich can vote.

Don’t think for a second that the Democratic Party leadership doesn’t know about this. A number of them have endorsements in the front of Nancy MacLean’s book, “Democracy in Chains.” But if they talk about it in public it will be turned into a political football. Joe Biden has said, “If Trump gets elected it may be the end of America as we know it.” So, this may be your last chance to vote in a real election.

1 note

·

View note

Text

alone, i fight these animals [alone, until i get home]: ii

I.... have no clue if this qualifies as a proper multichapter, but I discovered myself wanting to do a second part to this, so that is what I did. It was mostly an excuse to write some Frank/Madani and Frank/Matt frenemy BROTP, because I have a need for that.

If this turns into a real fic, I will post it on AO3. I have no idea at this point, and have not actually done something sensible like plotting it out, but yes.

The engine dies with a rumble, as Frank switches it off and leans back in the driver’s seat, watching the docklands with a wary eye. The car is an old beater of a Chevy, outwardly indistinguishable from any other low-slung growler that might be cruising around here, but he doesn’t go to meetings like this without enough horsepower to make a fast getaway. Frank modified it himself and keeps it in the garage with the battle van, which luckily he hasn’t had to bust out for a while, and it’s a little less eye-catching than that big black beast. Serves the same purpose, though. He tends to change up the paint job, add or remove accessories. Doesn’t want to get distinctive, identifiable.

He’s said that he’ll be here for ten minutes exactly and then he’ll leave, so Madani, if she’s coming, better be fuckin’ punctual. He doesn’t know that he trusts her to look like anything other than a federal agent rolling up to a clandestine meet with a confidential informant, but she must have climbed the ladder by not being an idiot. There’s still the chance that she’s going to spring handcuffs on him for that scene the other night, but Frank doesn’t think so. She needs his help with catching the rest of the ring, whether or not she’ll admit it. That’s the reason for this. Everything else is brass tacks and haggling.

It’s minute seven and forty-three seconds when Madani, having apparently decided that she doesn’t want to time their arrivals to coincide exactly, but conscious of the deadline, turns in. Frank can’t tell it’s her at first, which is a good sign, but does make him reach momentarily for his gun. Then the other car parks with a crunch of gravel, a slight figure in a jacket, hooded grey sweatshirt, and jeans gets out, and strolls across the icy pavement to his. He clicks the door to unlock it, and Madani ducks into the passenger seat, wrinkling her nose. “You ever heard of Febreze, Castle?”

“Don’t think you came here to complain that my shit stinks, huh?” Frank glances at her, trying to judge her temperament for being difficult. Her dark curls wave out of the hood, she probably has her badge clipped right under her sweatshirt, and he can just feel her longing to brandish it in his face. “Or if that’s your opening line, you already know you’re backed into a corner, and you need to act like you can throw your weight around before you ask for a favor.”

Madani gives him a searing look. “I have no idea why I came here.”

“You asked for it.” Frank leans back in the seat, hands behind his head. “And I think we’re past you pullin’ rank on me, acting all fuckin’ superior, aren’t we?”

Madani chews that over for several moments, which means she can’t dispute it. “Fine,” she says at last. “I still don’t necessarily think you’re a good man, Frank, but you don’t give a rat’s ass whether I think that or not, and in this job, you don’t get the luxury of working with Mother Teresa all the time. You were, admittedly, effective with breaking the pedophile ring. We did run some diagnostics on their computers, and we have more names.”

Frank snorts – breaking the pedophile ring is the most goddamn government-jargony way he has ever heard to say blew their fucking brains out, and he used to work for an actual black-ops hit squad. “You’re welcome,” he says, since she’d probably choke on it. “Told you.”

“Yeah, all right, fine.” Madani waves an irritated hand. “Anyway, there has been a lot of red tape in the office recently, bullshit with the budget, obsession with going after softer targets. You know this administration and the kind of people it thinks are a threat. So – ”

“And you, as Special Agent in Charge, don’t always agree with the strings they pull to make you dance?” Frank could gloat over this a little more, but there will be time for that later. “Going rogue? You want to talk to me because you know I get results, when those dickheads just sit there with their thumbs up their ass and do jackshit to actually help?”

“Something like that.” It’s clear that Madani has plenty of frustrations, whether or not she’s going to let on to him. “I still believe in our institutions, no matter who’s running them, but it’s true that things are taking a… turn right now, and I’m under a lot of scrutiny. If I can’t even push through an operation to take a bunch of child abusers off the street, then…” She trails off. “I still don’t know whether to thank you for that or not, by the way. They’re dead, but it looks like I blew it and once again, a vigilante had to wipe the U.S. government’s ass. They want an excuse to fire me, Frank. I’m asking you to help not give them one.”

Frank takes that in without answering, He can guess that Madani is too female and too ethnic to make the douchebags of record very comfortable; as the daughter of Iranian immigrants, even a thoroughly Americanized one, these chickenshits are constantly going to be looking for an excuse to pull the trigger, so to speak. And if Madani goes, whatever tenuous protection he has from DHS reopening his case goes as well. There are plenty of assholes jockeying to take over her chair, and all of them would love to make a big splash by catching the Punisher. Normally, Frank thinks, they bend over fuckin’ backwards to defend white men with guns, but not when he won’t play ball with you. That’s different.

“Fine,” he says. “And to save your ass, you’re the one here asking for more help from me. What do you think I’m going to do?”

“I can transmit the intelligence to you,” Madani says. “Names, aliases, assets, last known whereabouts, everything the analysts have managed to piece together. These guys are nasty, Frank, they aren’t just making kiddie videos on the Deep Web. They’ve got a lot of other interests, and all of them are equally bad. I need you to track them down.”

“And?” Frank stares at her, one eyebrow cocked. “What do you think I’m gonna do next? Give them fuckin’ milk and cookies?”

“Of course not.” Madani sounds exasperated. “You really think I don’t know what you do, Frank? But as it happens, yes, I’m asking you not to kill them. Track them down, capture them, hurt them if you have to, but don’t kill them. I need them, I need them physically to show the brass and to prove that I succeeded. After that, all the stuff they’re in, the prosecutors can probably push for the death penalty. They’ll die one way or another, if that’s what you want. But if I don’t get them alive, it all falls apart.”

“I’m not a goddamn bounty hunter,” Frank snaps. “I’m a killer. I don’t take prisoners, Madani. I’m supposed to – what, get on a plane with these assholes tied up in a line behind me? If you’re asking me to go outside the rules and get them, you want them dead.”

“It’s not like I’m defending them!” Madani barks back. “I know they’re terrible! But if they just die mysteriously, I have pretty much no shot at keeping my job, and then there are going to be people looking for you, Frank. Looking for you and Karen. How much do you want to risk that? It seems like you’re a little more settled these days. Have something to lose.”

“You threatening me?” Frank whirls on her. “You threatening me, huh?”

“No.” Madani, to her credit, keeps her composure, though her nostrils flare. “I’m warning you. If I’m not in charge of DHS, it’ll look for you. Whoever you’re with is going to come into the firing line too. I’m sure you don’t want anything to happen to her.”

Frank doesn’t answer, though his finger twitches so violently that his entire hand jumps on his thigh. Goddamn it, Madani. She has his balls in a fuckin’ vise, has him bent over a barrel, and the worst thing is that she probably knows it. He can’t play games with Karen’s safety, even if every one of his natural instincts is to just cap the bastards in the head and call it a day. Madani needs them alive for her little stage play, and Frank – whether or not he wants to admit it – needs Madani where she is right now. It’s at least in some part due to her that he can walk around New York as a free man, even one ostensibly called Pete Castiglione. That’s a flimsy alias, and any digging, or anyone even looking too long at his face and a newspaper front page, would be able to piece it together. If he wants to keep this life, whatever it is, he can’t just charge in, blow shit up, and charge out. He needs to be strategic about this. Long-term. Fuck.

“So what?” he growls at last. “You give me the intel, I track down these bastards, I give them to you for a Christmas present? You do Christmas?”

“Yeah.” Madani rubs under her eyes with both fingers. “My parents thought it was an important part of an American upbringing. Any other questions?”

“And after you show them to the bosses, you check whatever godforsaken boxes you have to check, you prove you’ve run the operation, they die.” Frank is willing to help her, if it contributes to keeping Karen safe, but he isn’t going to budge on that point. “They don’t get some cushy life in protected custody. You’re going to arrange it somehow that they die, and I don’t mean waiting ten years on death row. Got it?”

Madani’s cheeks flush a dull red. “I really don’t want to be an accomplice to extrajudicial murder, Frank. No matter how terrible they are.”

“Well, that’s what makes you and me different.” Frank grins mirthlessly. “Besides, you play your cards right, it doesn’t stick to you. You know you’re taking a hell of a chance here, don’t you? All these under-the-table arrangements with me come out, you’re finished one way or the other. But you think you can do it on your own, you’re welcome to run back to your department and sign all your paperwork and follow procedure. Have fun.”

The silence is briefly and overpoweringly enormous. Then Madani says, “Fuck you, Frank.”

“Take that as a no?” It’s starting to get chilly in the car, with the engine off and the temperature below freezing, and Frank blows on his hands. “No, you can’t do it alone?”

“I obviously would not be here if I thought things were going well on my end.” Madani sounds like she would prefer to have her fingernails ripped out rather than admit it, but she doesn’t have a lot to lose now. “Obviously, I’m sure I can trust you to total discretion. If you need money or something else, I can arrange it. Wouldn’t be the first time.”

“I can handle money.” They’re obviously not living on Karen’s newspaper/paralegal salary alone, and David gave him a nice chunk of change a while ago, which is kept in a bank in the Caymans. “But last time one of us sent the other some kind of sensitive information – when David sent you the Zubair video – we know what fuckin’ happened next. If anything, if any bit of this, catches up to Karen in any way, we’re done, Madani. We’re done. I will rip anyone who comes after her to fucking pieces, and I don’t give a shit if they’ve got a government badge or not. I’ll help you stay in DHS if DHS is going to mind its goddamn business. But if you get some other kind of conspiracy going, anything like Rollins, I’m warning you right now. I will kill all of you. I am not fucking joking.”

Madani takes that without answering, though her lips tighten. “I’m aware,” she says at last. “You’re a loose cannon, Frank, but we want the same things, the same people taken down. Let’s start there. You let me handle my end of the BS, I let you handle yours. Sound good?”

“Yeah,” Frank grumbles, even though he still has plenty of misgivings. Maybe he should leave, should move out and get his own place somewhere, even if he doesn’t want to move back into that goddamn basement with David again. It feels like it’s too unforgivably dangerous to keep living with Karen, but letting her alone is even worse. Jesus. “Send me the information and be careful with it. I’ll maybe talk to Lieberman, see if he wants to help, but he’s got his family back. I’m also telling you now, nothing happens to Sarah and those kids. They’ve been through enough. See to it.”

Madani pauses, then nods. They reach out, shake hard enough as if trying to break each other’s fingers, and then she jerks the door open and climbs out, striding back to her car. Frank scans to see if anyone’s parked on a rooftop or has been loitering too long by the underpass, but their meeting looks to have been unobserved. He swears again under his breath and switches back on the engine, firing up the heater, and waits until Madani’s car has vanished down the alley before he throws the Chevy into reverse and peels out in the other direction. Well, that was a whole bunch of shit, and he doesn’t even know how far he’s already dug himself into it. Maybe if he had just left it alone to start with and never went after the ring, but that’s more than he was prepared to countenance. Makes him see red every time he thinks about it. Frank doesn’t see himself as some kind of sainted protector of the city. Far from it. But he was born in Long Island, he grew up here, he left for the first time at age eighteen on his first deployment, and while he’s been plenty of places since, there’s still something about New York that has a hold on him, broken and blackened and painful as it’s become. He loves this place, even if it hates him. He wasn’t letting them live in it.

Frank guns it down the service road back to the main thoroughfare, turns out, and drives back to the out-of-the-way garage where he keeps this car and the battle van. He pulls in, unlocks the chain link fence, rolls through, and parks, then can’t help searching for any signs of intrusion or forced entry. He has no idea who he would expect to be here, if anyone, but that long-ingrained urge to look over your shoulder, to check your six, that never goes away. Madani said the pedos had plenty more nasty friends. Could be any one of them.

Everything, however, looks ordinary. Frank makes a note to ask David for some more cameras, keep more of an eye on this place from afar, and wonders if he can really ask him to strap back on and wade into the shit again. David isn’t a soldier, and he got involved in this to start with to clear his name and be reunited with his family. He got that. Not much incentive to risk them all over again, much as he might personally want to help Frank out or feel indebted to him. Frank has some tech know-how, but he’s probably overall comparable to David trying to fire an AK-47. In other words, totally fucked.

Frank thinks that the lack of a partner has never bothered him before, the fewer people he can involve in this low-level shitstorm the better, and he’ll work out what he needs to. Having finished his sweep, he locks up, battens down, and catches a bus into midtown, briefly tempted to stop by Nelson, Murdock, and Page just to make Foggy choke on his tongue. Stroll in and bring Karen lunch, just because. But now, he wants to be cautious about going straight from a meetup with Madani to the office. He hasn’t told Karen about this new wrinkle yet, and he still doesn’t know whether he should. Probably. They just had a fight about it, and he can’t just disappear for days or weeks without an explanation. It’s always easier to do this work when you have no one to account yourself to, but he can’t lose her.

Still coming up with no apparent solution to his dilemma, Frank buys a hot dog from a sidewalk cart and sits on a park bench to eat it, scattering the remains of his bun to a flock of ravenous pigeons when he’s done. It’s cold but clear, New York running around and getting ready for Christmas, and he once more feels that impulse, that wish that he could kick back and enjoy it. But who knows. Who fuckin’ knows.

Frank sits there a moment more, then growls, “Shit.” This doesn’t do anything, it doesn’t even really make him feel better, but it’s an acceptable reaction to what he has to do. David is a glib son of a bitch who’s great with a keyboard – and has admittedly saved Frank’s ass a couple times – but if this is going to come down to brass-knuckle diplomacy, which it almost assuredly will, Frank needs someone who can fight, who is just as annoyingly dedicated to getting bad guys off the street and out of New York, and is equally insane enough to keep running full speed into punches. Yeah, they have some pretty major philosophical oppositions, but still. This looks like a two-vigilante job, at fuckin’ least, and besides. Maybe they should be, you know. Friends. For Karen’s sake.

Frank swears again, then pulls out his phone, scrolls through it to “R,” and hits the number. He swiped it from Karen’s, and the recipient doesn’t know he has it, so this is going to be a surprise, and could of course horribly backfire. But he waits a few more moments until it’s answered. “Murdock.”

“Uh.” Frank blows out a breath. “Hey, Red.”

There is a very long silence on the other end, as Frank realizes that they’ve never had an actual conversation where he’s made it clear he knows the deal. But come on. He ain’t fuckin’ stupid. (Plenty of people would disagree, but nearly all of them are dead.) He sat up there on that rooftop with Red yammering at him, then he sat in court with Murdock going on just as annoyingly, he put two and two together. He’s always acted like he didn’t know, just because Red has a bug up his ass about the secret identity shit, and besides, Karen knows, Karen told him anyway. Not that Frank would say that, because he figured it out himself, and he’s not gonna throw her under the bus if Murdock gets pissy. Well, this is already fun.

“Frank,” Matt says at last, sounding… well, let’s just say, not goddamn thrilled. “Why are you calling me?”

This is a fair question, and Frank hunts for some kind of explanation that won’t immediately make him hang up. “Karen’s fine, Karen’s fine,” he says, in case that’s what Matt thinks would be the only reason to make him get in touch. “Not any of that. I actually had a suggestion. For some work. If you were interested.”

“Work?” Matt sounds leery. “What the hell kind of work, exactly?”

“The kind you and me both do, Red. Take some bad people off the streets.”

“I didn’t realize you – ” Matt starts, then stops. “I didn’t know you… knew.”

“Yeah, well, we already established you were a dense motherfucker.” Frank switches the phone to the other shoulder, even as it belatedly occurs to him that maybe he shouldn’t be insulting the guy whose help he is, regrettably, asking for. “You were my goddamn lawyer, think I don’t know how you talk?”

There is another mulish silence as he can hear Matt chewing over that, wanting to ask how long he’s known, if he’s told anyone else, all that. Murdock might be tangentially aware that Frank and Karen are knocking boots, but does not want to have to actually refer to it in any capacity, and Frank is tempted to make a smart remark on that topic, just cuz. But he’s not going to be a dick to Karen, even in absentia, to score a couple cheap macho asshole points on a blind lawyer in a Halloween costume. Instead he says, “You want to know more or not?”

“Does this involve murdering the bad people? Because if so, you know I can’t agree to that.”

“Jesus, Red. They’re about as bad as you can get, even you don’t want to hand-hold these bastards and take them to Sunday school. I can send you the details once I get ‘em, but either way, they need to be stopped. Doing some fucked-up shit, a lot of fucked-up shit, actually. So?”

“Fine,” Matt growls, as Frank figured he eventually would. “Let me know the intel whenever you get it.”

“You need some Braille shit or something?” Frank asks. “Or you have something that reads your email for you?”

“I got through Columbia Law, you know I’m not actually an idiot. Just send it, I’ll work on it from there.” Matt pauses. “You told Karen about this?”

Frank feels like Matt Murdock is the least qualified individual to give anyone advice on this subject whatsoever, especially about this woman, and it’s only with difficulty that he bites himself back from something designed to cut. “No,” he says. “Not yet.”

It’s hard to tell what Matt thinks of that, especially over the phone. Then he says, “Obviously, I think the one thing we can agree on is that we don’t want this to spill over onto her. So whatever we’re chasing here, we need to keep her safe.”

Frank knows that wanting to keep Karen out of this has worked exactly like jackshit in the past, and he knows too that she’s strong and capable and no wilting hothouse flower, would probably shoot some of the dicks herself if she had half a chance. But he understands what Matt’s saying, given that he just outright threatened Madani to be sure none of this touched Karen, and doesn’t want to torpedo their alliance at this preliminary stage. “Yeah,” he grunts. “She stays out of it, much as we can. That’s not a problem. Anything else?”

“Yeah,” Matt says. “You’re still a total asshole.”

“Get that a lot.” It is not, Frank feels, entirely inaccurate, even as he rolls his eyes, because Christ, it’s rich coming from this prick. “Talk to you later, Red.”

With that, feeling as if it’s better to get out of there before things go any more south, he hangs up and stares at the phone, not sure he feels a whole lot better. He’ll go to the safe house tonight, where David still keeps his computers and surveillance setups, since that’s where Madani will be transmitting the information, and Frank likes to periodically check for signs of interference anyway. He gets up, chucks the hot dog paper tray away, and heads out. Takes a different route than he did in. Gets off a stop too early, and doubles back a few times. Once he’s finally satisfied that nobody followed him, he reaches the safe house, unlocks the chains, and heads inside. They’re not actually living in this shithole anymore, thank God, but it still gives him a momentary shudder.

Frank switches on the monitors, scans his retina, and waits until everything has booted up. There are about five passwords he has to enter before he can access the message that there’s a new file waiting for him, and he approves; Micro doesn’t fuck around with cyber security, especially given that there’s gotta be a lot of fishing for this. It’s a plaintext ASCII file, scrubbed of all identifiable electronic traces, and Frank pauses, then clicks to open it. It’s a list of names, social security numbers, addresses, email and phone numbers, known aliases and associations, everything that DHS has pulled from the servers on the remaining members of the pedophile ring. A separate file contains any mugshots on record, grainy jpegs, or driver’s license photos or anything else on public record.

Frank plugs in an encrypted flash drive, types more passwords to unlock it, and transfers everything onto it. He considers sending some kind of acknowledgement back to Madani that he got the information, but she can probably fuckin’ guess, and he doesn’t want to leave too many digital fingerprints. He checks that the files have copied over correctly and haven’t glitched, then deletes all the originals and clears every kind of cache he can think of. Obviously, he doesn’t think anyone is going to be in here working over these machines, and good luck getting through David’s firewalls, but better safe than sorry.

Having finished the retrieval, Frank figures the best way to hand the information over to Matt is probably in person – maybe he can drop by tonight after dark, see if Red wants to slap on that stupid fuckin’ horned helmet and they can go right away. Some of these bastards still have to be in town, right? They can’t all have made it out of New York. They’ll have guessed it’s too dangerous to travel under their real names, with an APB out for them, and fake identities take at least a little time to process, even if they have a good hookup. Try to stay hidden and wait for the smoke to blow over, feel like moving’s more dangerous. Frank’s counting on that, anyway, but if they’re backed into a corner, this won’t be pretty.

Frank pauses, then ejects the flash drive, puts it into a zippered pocket on his jacket, and powers everything down. He locks up, leaves everything as he found it, and heads out. It’s getting on in the afternoon by now, the day short and chill, and he wonders if Karen’s heading back to the Liebermans’ place tonight. At least it will keep her distracted from wondering where he is, but it admittedly feels a little like cheating. He should tell her, right? They’re trying to do that now. Not everything, maybe, but more.

Dusk is falling over the city by the time Frank makes it back to central Manhattan, a few stops more on the subway, and steps out into Hell’s Kitchen, which looks beautiful at this hour, all the lights coming on and Christmas trees glowing in windows and people hurrying by eager to be somewhere warm. Frank’s breath steams in the chill as he walks up to the apartment, lets himself in, and heads upstairs. Karen should be home by now. He’ll do it, he promises, he will maybe even ask her help. She’s a goddamn good journalist, she’s like a dog with a fuckin’ bone. She’ll gnaw and gnaw until she finds out whatever she needs to. But if he does that, he makes her a legitimate target, and when he’s promised himself this is the last one, the last mission, before he really settles down and tries to make a new life with her, he can’t quite shake the fear. Everyone knows what happens to the cop who takes this one last job before he’s supposed to retire, or whatever. He always gets killed.

The apartment, however, is dark and quiet, and it doesn’t look like Karen’s there. Frank wonders if he should call, just in case, but he doesn’t want to act like her goddamn babysitter; she’s a grown woman, she can look out for herself. Still, the ever-present prickle of anxiety whenever he doesn’t 100% know that she’s safe is difficult to dispel, he has often had reason to pay attention to this instinct, and he groans, pulls out his phone, and hits her number. Just pick up, Karen, Jesus Christ. Don’t give me a fuckin’ heart attack.

She doesn’t; it goes over to voicemail. Frank hangs up, reminds himself there are plenty of non-nefarious reasons for this, and struggles not to immediately jump to the conclusion that she’s been kidnapped by a lot of angry perverts and they’re holding her for ransom – or worse – against the death of their fellows. He rubs both hands over his face. It’s not that far to Red’s place from here. Ten-minute walk, less if he runs.

Frank gets together a decent selection of guns, throws them into his bag with extra boxes of ammo, straps a nine-millimeter to his ankle holster, and shoves his Ka-Bar into its sheath at his hip. Then, with a final look around, and wondering if he should just get David to install a tracking device on Karen’s phone (he did once tell David that Sarah would cut his nuts off if she discovered the Lieberman house spy cameras, but still), he heads back out. He jogs down the stairwell, and emerges into the chilly evening, glancing around once more just in case the subway was late or something and Karen’s getting home now. Jesus, this relationship shit is stressful. Can’t deal with his heart always walking around somewhere else again. Especially when that heart is as feisty and independent and fuckin’ reckless as Karen. He isn’t the right man to tell anyone to take a goddamn chill pill, but jeez.

It’s eight minutes later when Frank reaches Matt’s street, turns in, and leaps up the steps two or three at a time, reaching the hallway and banging on the door of his apartment. He better be in, or Frank’s really gonna have a problem, and indeed, Matt jerks it open a moment later. “Frank? What the hell? I thought you were going to send an email.”

“Plans changed.” Frank shifts tensely from foot to foot. “Look, throw on your pajamas and your fuckin’ hat with the horns, huh, Red? Let’s go, yeah?”

Matt raises both eyebrows. After a moment he says, “Your heart rate’s off the charts. What’s wrong? Are you sure Karen’s okay? Frank, Jesus, you know I don’t like this, whatever it is, with you two, but if you can’t even look after her – ”

“Yeah, because what we really needed was your goddamn opinion.” Frank clenches both fists, reminds himself that he has no solid evidence that anything is awry at all, and takes a deep breath, trying to steady himself. A soldier who runs into the middle of a fight frantic and haywire and not focused usually gets shot in the first few seconds, and he’s definitely not letting Matt see (or whatever, echolocate, he doesn’t know exactly how all that works) him at less than his best. “We can probably get to some of these assholes tonight, that’s all. Checked the addresses, a dozen of ‘em live in a ten-block radius in Queens. I take one half, you take the other, we could close the book. You up for it or no?”

Matt hesitates. It’s clear that his first instinct is also to rush in and take on the baddies, even if he is leery about doing it with Frank. At last he says, “If you’re putting Karen in danger, you know the right thing to do would be to walk away.”

Frank starts to say something, then stops. It’s worse that he’s had that idea himself, that he keeps having the impulse to bail out and disappear and never be seen again, but if that’s what Matt thinks he should do, well, it’s clearly wrong. Same guy who lied to Karen for months and months, keeps dropping out of her life and then reappearing and expecting that things will just be the goddamn same between them, jerking her around and causing her heartache and worry and still too unable to realize that there’s a cost to living this way, there’s a cost. Frank isn’t gonna judge Matt on the vigilante thing, though for goddamn sure he judges him on a lot of others. He knows that compulsion to do what you know is right, no matter if anyone else understands it that way or not. But he’s never been under any illusions that it’s compatible with a normal life, with keeping people in it, with thinking they’ll see it the same way and you can just split into two halves, two halves that will always stay separate from the other. He called Matt on it before. Was it you that did those things, or was it the mask?

“Yeah,” Frank says. “I didn’t come here for your bullshit romantic advice, Red. You can help me or not, but either way, I’m going.”

Matt once more starts to respond, then stops. “Still not sure when you worked out it was me.”

“Come on. First thing I ever said to you, when you walked into my hospital room, was that I knew who you were. You think I only meant your shitty fuckin’ law firm?”

Matt chews over that, and (wisely) decides not to rebut. Finally he says, “Meet me in the alley. Five minutes.”

Frank rolls his eyes, guesses that there’s some mystique that has to be preserved, can’t see Murdock shimmying bare ass into his fancy long johns or whatever, and takes his leave. Five minutes later, he’s in the back alley as instructed, when Red leaps down in full devil glory and jerks his head. “Let’s go.”

They wend their way through the shadows, across some rooftops, then get a cab part of the way. Frank imagines that even this is not the weirdest thing the driver has seen in his life, waiting at a red light like everything’s normal with goddamn Daredevil and the Punisher sitting side by side in the backseat and determinedly not looking at each other, but it’s probably close. He does keep trying not to steal glances at them in the rearview mirror, though. Finally says, “You boys out for the evening?”

“Just drive,” Frank orders him. “Yeah?”

Wisely, the guy does so, reaches Queens in another fifteen minutes, and as they get out of the cab, Frank shucks out a big tip and hands it over with the fare. “Don’t need to tell you that you saw nothin’,” he reminds him. “So you keep your trap shut.”

“Yes, sir. Got it.” The driver takes the money and nods awkwardly. “Have a – good night.”

With that, he lays rubber getting out of there, Frank watches him go with a sardonic expression, and then hefts his bag of guns with a clunk. “This way,” he informs Matt. “Stay sharp. One of them had a .38 last time, and I’m guessing they’re waiting for someone to turn up and try to sic ‘em. Feds or otherwise.”

He can feel Matt wanting to say something about the guns, wanting to ask how they’re going to deal with this, exactly, or maybe sensing that if they’re going to split this half and half and make any success of it, they’re just going to have to turn a blind eye (literally) to what the other’s doing. Frank snaps the stock on his carbine into place, and glances ahead. There’s a light on, in the first floor of the somewhat seedy office park. That matches the intel, where they had another meet-up spot. If the pedos are in there now, Red better not get in his way.

He glances sidelong at his – for the moment – ally. Matt raises a hand, listens, then – whatever he hears, Frank can’t tell, but he’s deciding to trust it – nods once.

Time to go.

#mcu#netflix punisher#the punisher#kastle#kastle ff#(though it's mostly frank talking about karen with other people in this installment)#frank x madani#frank x matt

32 notes

·

View notes

Link

This has been going on for over 5 years, funded by the Koch brothers, to take State Legislatures, turn them Republican, and use ALEC to draft Agreements for passage in those states to Agree on an Article V Constitutional Convention. They have secured 28 out of the necessary 34 States needed for approval. - Phroyd

Mark Levin's bestselling book, The Liberty Amendments, contains some radical notions about a complete overhaul of the US constitution, but to debate the specifics of their merits is to ignore the larger insanity of the project.

He proposes 11 amendments, intended to be affixed more or less immediately (well, as soon as can be achieved), and the number alone is – ahem – audaciously hopeful. Remember, since 1789, the constitution has only been amended 27 times; ten of those amendments were accomplished when passed as a group with the adoption of the bill of rights. There have been over 11,000 proposed amendments. A simple assessment of odds puts any one amendment at about a 0.2% chance of getting passed. The chances of all 11 getting passed is beyond my limited recall of high school mathematics. Then again, in the fantasy world where one of Levin's amendments gets ratified, all of them have 100% chance.

In the real world, almost no one believes conservatives could accomplish what Levin has put forward. He begins the book with a blustery denouncement of the current administration familiar to anyone who's surfed over the AM radio spectrum in recent years. And give Levin credit: his rhetorical style has the ornate filigree of a 19th century lawyer – all embedded clauses and rat-a-tat 50-cent words:

Social engineering and central planning are imposed without end, since the governing masterminds, drunk with their own conceit and pomposity, have wild imaginations and infinite ideas for reshaping society and molding man's nature in search of the ever-elusive utopian paradise.

Levin channels his silken outrage into a generous read of the constitution's article V, which he describes as a mechanism for "restoring self-government and averting societal catastrophe (or, in the case of societal collapse, resurrecting the civil society)". The parenthetical aside is telling: he means to impress upon readers – ahem, again – "the fierce urgency of now". With the alarm bells ringing so loudly, we hardly notice the improbability of actuallyusing article V, which theoretically allows state legislatures to directly propose constitutional amendments – amendments that would not be filtered through Congress. (Congress is part of the problem, of course: it "operates not as the framers intended, but in the shadows.")

State legislatures, as Levin fully knows, have become increasingly conservative over recent years – due to the older, whiter, smaller electorate that turns out in off-year contests. If any layer of our government is likely to approve of the amendments Levin puts forward, it's them. Indeed, as he points out, many states already have adopted, for instance, terms limits and balanced budget provisions in their constitutions.

Levin's complaints and his ideas about how to solve them have the perfect structure of a luminous Mobius strip: if you believe his indictments, then you'll believe his solutions. But once you leave his twilit logic, the structure crumbles. Phyllis Schlafly, who plays on the same ideological team as Levin, wrote a response to his article V plan that could be summed up as "LOL": Levin and his supporters are "fooling themselves" if they believe an article V convention can achieve their goals. They can "hope and predict, but they cannot assure us that any of their plans will come true …The whole process is a prescription for political chaos, controversy and confrontation."

It's no wonder that many conservatives have chosen to believe anyway. Levin's fantasy world is elaborate and specific: he presents his amendments as necessary to recapture the intent of the founders, even as the very proposal of so many "reforms" goes against the founders' explicit design of a constitution that is very difficultchange. The meat of his proposals would be, I think, just as unpalatable to their view of the constitution as a broad outline for governance, one more inclined to negative than positive prescriptions. One fellow conservative noted that Levin seems less interested in reforming a corroded document than "tinkering" with it.

Indeed, the specificity of his recommendations – he includes an amendment that would set an upper limit to government spending as "17.5% of the nation's gross domestic product for the previous calendar year" (the number seems to be drawn out of thin air) – suggests that Levin is working less to save the constitution from "Statists" (capital S, always) than just backwards-engineering his personal ideal.

Indeed, there's no arguing that his recommendations are not largely (if not solely) designed to reshape the country as conservatives desire and to disenfranchise or otherwise disempower anyone who might disagree with those objectives. Levin may be able to muster Federalist Paper-footnoted arguments for term limits for supreme court justices, a national voter ID law, and the strengthening of states' ability to override federal law and supreme court decisions, but the real-world impact of such amendments would be to turn America back toward the Federalist era in terms of civil rights as well.

Levin's ideas are not conservative in political philosophy at all, at least in the sense of "standing athwart history and yelling 'stop'". He is liberal to the extreme when it comes to using the tools of the founders beyond what they intended. He seems to confuse his admiration for the logic and writing of our early leaders with ahistorical alignment with them. The Liberty Amendments is heavily larded with passages lifted from their correspondence as well as the Federalist Papers. And by "heavily larded", I mean give-Paula-Deen-pause "larded". Heart attack-inducing larded. You could fry Levin's book and serve it at a state fair.

But it does not come fried, only half-baked. The passages from the founders are not invigorating (or tasty), but dry coughs of rationalization. Yet, it is their frequency that makes Levin's book curiously impressive: it debuted at the top of the New York Times bestseller list. And it is as boring as a phone book – or a recitation of the Affordable Care Act.

Though sprinkled throughout with the ranty denouncement of "soft tyranny" that energizes likeminded listeners to his radio show, the odd genius of The Liberty Amendments isn't that he has riled up his base with fiery rhetoric, but that he seems to have riled it up without it. Given the ludicrousness of his specific "fixes" and the near-impossibility of achieving them, Levin has produced something I have to concede I admire – as a literary trope, if nothing else – speculative fiction disguised as documentary. I admit I liked it better in World War Z.

It is true that Levin's amendments are dead on arrival, but his are zombie ideas that may yet attack. Levin has been mentioned as a possible moderator for the Republican national committee's 2016 primary debates. The committee intends them to be more substantive and less theatrical than the clown-car contests of 2012.

The notion that Levin would lend gravitas, via his originalist fixations, to the events has understandable appeal. But gravitas only comes from plans that are grounded, and Levin's are just wishes, conjured out of thin air.

Phroyd

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Best Movies of 2021 (So Far)

https://ift.tt/3iTu7sI

Can you ever really go home? Millions of cinephiles are likely asking themselves this as summer 2021 winds down with doubt again lingering over their favorite movie houses. For a time, theaters were once again open for big business in the U.S. and UK, and remain so in at least one of those venues. But box office reports paint an ambiguous future, and many casual moviegoers clearly remain reluctant about returning to the cinema.

Nonetheless, it’s still good to be back in those old familiar places, as well as to have an ever expanding list of options to discover on streaming. Compared to last year, 2021 feels like a sunny balm, particularly now that the heaviest hitters and biggest surprises of July and the dog days of summer have landed.

It’s why we typically save our “mid-year” ranking for that deep breath between the end of summer escapism and the awards season push that begins in September. There have been some real treats on the 2021 calendar, so whether you’ve seen the entire list below or are looking for something you missed, sit back and enjoy a collection of the best movies of 2021. So far.

10. Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar

Kristen Wiig and Annie Mumolo wrote and star in this bizarre, brightly colored, and utterly joyful comedy that defies expectations throughout. The two are middle-aged best friends who take their very first vacation to Florida together to visit the idyllic Vista del Mar.

But it’s not all cocktails and banana boats. Behind the scenes, super villain Sharon Fisherman (also played by Wiig) has an evil plan for the resort. With shades of the best of Austin Powers (though far more sincere) Barb and Star is a good natured friendship comedy through a surrealist lens, which could scratch an itch for anyone missing a bit of beach time this year.

9. Psycho Goreman

Unexpected gem of the year surely goes to this utterly bonkers grue-filled cosmic horror B-movie which is also really funny and kind of sweet at the same time. It follows annoying little shit Mimi (Nita-Josee Hanna) who bullies her brother Luke (Owen Myre) mercilessly. After defeating him in a game of “crazy ball,” Luke’s punishment is to dig his own grave (!) but instead the pair discover an artifact which turns out to be the key to controlling a universal evil imprisoned on earth for trying to destroy the galaxy.

So of course Mimi names him Psycho Goreman and forces him to hang out with her family and friends despite his insistence that he will bathe in their blood the moment he is freed. From Steven Kostanski, the director of 2016’s The Void, Psycho Goreman is a spot-on blend of brutal slaying and hardcore gore, a cosmic plotline involving an alien council and a wholesome family comedy. An unexpected delight.

8. Cruella

Emma Stone is a punk rock designer in the mold of Vivienne Westwood in this vibrant London-set comedy, which is on paper a prequel to 101 Dalmatians. But in reality, take it as a standalone and you’ll have way more fun.

Up and coming fashionista Estella manages to impress one of the leading designers The Baroness (Emma Thompson) and secures a coveted job at her world famous fashion house. But when Estella discovers a dark secret relating to her own past, she takes on the outrageous alter-ego Cruella to destroy The Baroness by out-fashioning her at every opportunity.

Packed with banging tunes and great dresses, Cruella is a high energy spectacle but it’s the sparring of the two Emmas that brings the real electricity. Forget any future she might have as a puppy killer, in her own film, Cruella is a legend.

7. In the Heights

The sunniest film to hit theaters this season, Jon M. Chu’s In the Heights was as sugary sweet as the frozen Piragua Lin-Manuel Miranda hocks around this movie’s block. Based on the Hamilton composer’s earlier Tony winning musical, the picture was the rare thing: a Broadway adaptation that actually soars as high as its stage production and (rarer still) the first Hollywood blockbuster with an all-Latinx cast.

Read more

Movies

How Cruella Got That Crazy Expensive Soundtrack

By Don Kaye

Movies

In the Heights: You Need to Stay for Post-Credits Scene

By David Crow

The film came under fair criticism on social media for not being as inclusive as it could be, but that shouldn’t be the last word on such a big-hearted achievement. From the buoyant performances which have already opened doors for Anthony Ramos and Leslie Grace’s immense charisma, to the Latin, salsa, and hip-hop infused melodies which celebrate a culture long left out of the Hollywood image of American life, In the Heights is a jubilant celebration. There really hasn’t been a giddier time at the multiplex this year. Plus, those “96,000” and “Carnaval del Barrio” sequences really are fire.

6. Zola

Based on a “true” story which was told via a series of tweets posted back in 2015 (and the subsequent Rolling Stone article that brought the tale to prominence), Zola is a stranger-than-fiction saga seen through the lens of social media. An ultra contemporary, experimental, low budget comedy-thriller with a backdrop of abuse and sex trafficking, the film is as willfully uncomfortable to watch as it is massively entertaining.

From the jump, Zola (Taylour Paige) is a Detroit waitress and part time exotic dancer who meets a customer named Stefani (Riley Keough) and agrees to take a trip with her to Florida to hit up strip clubs where Stefani promises they’ll make a lot of money. With them are Stefani’s feckless boyfriend (Succession’s Nicholas Braun) and her obviously dodgy roommate. Sometimes told through spoken tweets with switches in perspective, this marks director Janicza Bravo as a compelling new voice, and her cast of leads as nothing short of captivating.

How much of what you’re watching actually happened? Well, that’s the elusive quality of social media…

5. Judas and the Black Messiah

Fred Hampton was murdered with the consent and planning of law enforcement at both federal and local jurisdiction levels. That Judas and the Black Messiah made this common knowledge would be reason enough for consideration. Yet that director Shaka King tells Hampton’s story so thrillingly here elevates his film into one of the most compelling crime dramas in years—only with the FBI’s illegal COINTELPRO program being the primary criminal element.

Told from the perspective of the man who spied on the Black Panthers and eventually facilitated the raid that took Hampton’s life, Judas radiates a despairing quality which somehow can still feel electrifying whenever Daniel Kaluuya’s powerhouse performance takes center stage. Which is pretty much any time the Black Panther chairman takes the microphone. Kaluuya deserved his Oscar, but LaKeith Stanfield’s paranoid turn as Bill O’Neal, the poor bastard coerced into being a snitch while still a kid, is what gets under your skin and walks beside you after the credits roll.

4. Pig

Are there really folks out there who wandered into a screening of Pig and assumed they’d get the Nicolas Cage knockoff of John Wick? I like to think so, just as I love to imagine what they said to each other afterward. To be sure, Michael Sarnoski’s Pig sounds on paper like something in that ballpark: Cage plays a hermit living in self-exile from his past life when ruffians steal his beloved… truffle pig. In response, he comes down from the mountain, ready to reengage with the old ways.

Read more

Movies

Judas and the Black Messiah Remembers Fred Hampton Was a Man of His Words

By Tony Sokol

Movies

The Suicide Squad Character Guide, Easter Eggs, and DCEU References

By Mike Cecchini

Yet when you realize those old ways involve being the greatest chef in his state—and reengagement means partaking in a fight club that’s far more pitiful than it sounds and simply cooking gourmet meals—the more apparent it is that this is a sophisticated, nuanced allegory about grief and self-identity. Anchored by Cage’s best performance in a long, long time, Pig is a gentle and revelatory experience that slowly unpacks its brilliance piece by piece, vignette by vignette. For those coming in wanting fast food, this probably will be a disappointment. For all others, it’s a resplendent five course meal.

3. The Suicide Squad

For once the marketing wasn’t kidding. Writer-director James Gunn does have a horribly beautiful mind, and we at last get to see it fully unleashed on a superhero property. Yes, the filmmaker made many cry over a CGI tree and talking raccoon in the Guardians of the Galaxy films, but perhaps not since Logan has a storyteller seen such free rein over valuable studio IP. Gunn didn’t waste it.

The Suicide Squad plays very much like the men and women on a mission ‘60s capers its director grew up on, but that structure is channelled here through a filthy and deranged sensibility. How else can you describe a picture that makes you want to cuddle a land shark who just swallowed a bystander whole? The Suicide Squad does that and more while providing a showcase for sure things like Margot Robbie’s irresistible Harley Quinn, as well as the dregs and rejects of DC Comics who ultimately steal the movie: David Dastmalchian’s Polka-Dot Man and Daniela Melchior’s Ratcatcher 2, namely. Box office be damned, this is one of the best superhero films ever made and will be a classic in the years to come.

2. The Green Knight

When you hear the name “King Arthur,” certain elements spring to mind. It’s one of those classic properties which have been adapted, exploited, and parodied with killer rabbits ad nauseam. Even so, it’s safe to say you’ve never seen the lore become as foreboding and startling as this. Reimagined through the gaze of writer-director David Lowery, the 14th century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight at last takes on a trippy and witchy connotation. An interpretation that pulls as much from medieval paganism as it does obsessions with chivalry and Christian virtue, The Green Knight successfully reinvents its Arthurian quest into a journey toward certain doom.

Read more

Movies

The Green Knight: Why David Lowery and Dev Patel Reimagined Arthurian Legend

By David Crow

Movies

The Green Knight Ending Explained

By David Crow

As the central figure on that mission, Dev Patel reveals superstar charisma and the ability to completely command the screen. His version of Gawain, the wayward nephew of King Arthur (Sean Harris), is vain, cowardly, selfish, and somehow wholly sympathetic as he searches for Ralph Ineson’s Green Knight: a godlike creature who has promised to behead Gawain when they meet again. Through it all, Lowery and company craft a sumptuous world that in every shot looks like the most transportive Dungeons and Dragons cover you’ve ever seen. The atmosphere is oppressively brooding, and it will not appeal to everyone. Yet like the very best films released by indie distributor A24, there is a touch of mad genius at work here that demands to be seen and then seen again.

1. Inside

As arguably the best piece of art to come out of 2020’s torments, Bo Burnham’s Inside was not marketed or even conceived of as a film. Nevertheless, it slowly transformed into one throughout its months-long production process, which forewent mere sketch humor to reveal an undeniably cinematic, experimental, and ultimately bleak heart. In other words, it’s a perfect distillation of how all mediums are blurring into that loathsome word: content.

Through heavily edited, conceived, and revised set-pieces, the film’s director, star, writer, and composer lays his insecurities and vanities bare. Filmed inside Burnham’s home studio space, Inside is the result of the young filmmaker behind Eighth Grade becoming acutely aware he’s regressed to his early resources as a teenage YouTube star: a camera, a music keyboard, some synth programs, and hours of idle boredom.