#Gerald B. Greenberg

Text

Scarface (Brian De Palma, 1983).

#scarface#scarface (1983)#al pacino#brian de palma#f. murray abraham#oliver stone#paul shenar#John A. Alonzo#Gerald B. Greenberg#David Ray#patricia norris

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

That car is dirty, Cloudy. We're going to sit here all night if we have to.

The French Connection, William Friedkin (1971)

#William Friedkin#Ernest Tidyman#Gene Hackman#Fernando Rey#Roy Scheider#Tony Lo Bianco#Marcel Bozzuffi#Frédéric de Pasquale#Bill Hickman#Arlene Farber#Harold Gary#Patrick McDermott#Owen Roizman#Don Ellis#Gerald B. Greenberg#1971

0 notes

Photo

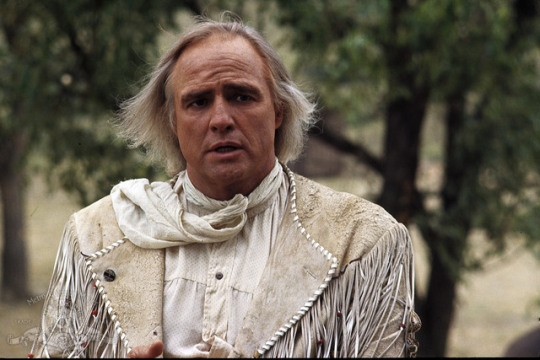

Heaven's Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980)

Cast: Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, John Hurt, Sam Waterston, Isabelle Huppert, Brad Dourif, Joseph Cotten, Jeff Bridges. Screenplay: Michael Cimino. Cinematography: Vilmos Zsigmond. Production design: Tambi Larsen. Film editing: Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, William Reynolds, Tom Rolf. Music: David Mansfield.

Heaven's Gate, for all its history as a calamitous flop, is not so much a bad movie as an inchoate one. You can see it go awry from the very beginning, when it tries to pass off the ornate architecture of Oxford University, where the scenes were filmed, for the spare red brick and granite of Harvard Yard. The film opens with a frenzied commencement for the Harvard class of 1870, which devolves into a swirling dance to the "Blue Danube" waltz. It's potentially an exhilarating opening, but it goes on and on and on, and serves almost no purpose in the rest of the film, except to introduce us to James Averill (Kris Kristofferson) and his friend William C. Irvine (John Hurt), members of the graduating class. Then the film jumps 20 years, to Wyoming, where Averill is marshal of Johnson County. We never learn why Averill, who is a wealthy man, winds up in this hard and thankless job, living in near-squalor and hooked up with Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert), the madam of a brothel. As for Irvine, with whom Averill reunites during a stopover in Casper on his way back to Johnson County, he has somehow become involved with the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, a group of cattlemen led by the sinister Frank Canton (Sam Waterston) who are trying to keep immigrants from settling on the land they want to graze. It's clear that director-screenwriter Michael Cimino at some point wanted Irvine, who is presented as an effete intellectual, to serve as a kind of chorus, commenting on the action, and as a foil to the more robust Averill, but Irvine keeps getting lost in the turns of the narrative and the excesses of Cimino's ideas. (The shooting took so long that Hurt was able to film David Lynch's The Elephant Man during his down time from Heaven's Gate.) In Casper we also meet Nathan Champion (Christopher Walken), who works as a kind of hit man for the cattlemen. But Champion is also a friend of Averill's and a rival of his for the attentions of Ella. There is the core of a more conventional Western in the relationships among these characters, but Cimino isn't interested in being conventional. What he is interested in are the elaborate set pieces like the waltz scene, a later scene with dozens of couples on roller skates, enormous throngs of extras milling through the streets of Casper, crowds of immigrants making their way to Johnson County, and battle scenes in which the citizens of the Johnson County settlement retaliate against the troops led by Canton that are determined to exterminate them. There are pauses in the hullabaloo for quieter scenes designed to work out the triangle formed by Averill, Champion, and Ella, but their characters are so lightly sketched in that we don't have much sense of the motives behind their sometimes enigmatic actions. And yet, it's a somehow maddeningly watchable film, thanks in large part to the often breathtaking cinematography of Vilmos Zsigmond, a committed performance by Huppert, the Oscar-nominated sets of Tambi Larsen and James L. Berkey, and yes, the sheer extravagance of what Cimino throws onto the screen. Without a plausible screenplay it could never have been a good film, but occasionally you can see how it might have been a great one.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skyy, also known as New York Skyy, was an American R&B/funk/disco band from New York City. They are best known for their 1981 hit "Call Me" and their 1989 hits "Start of a Romance" and "Real Love." Formed in Brooklyn in 1977, the original lineup included sisters Denise, Delores, and Bonny Dunning, along with guitarists Solomon Roberts and Anibal Anthony Sierra, keyboardist Larry Greenberg, bassist Gerald Lebon, and drummer Tommy McConnell.🖤💎🎼🎶

Signed to Salsoul Records in 1978, they released their debut album the next year. They crossed over to the US pop charts with the 1981 album Skyy Line, featuring the hit "Call Me," which reached number 26 on the Billboard Hot 100 and was their first number 1 on the R&B charts. The album was certified Gold by the RIAA.

Skyy moved to Capitol Records in the mid-1980s, releasing the album From the Left Side in 1986, which included the top ten R&B single "Givin' It (to You)." In 1989, under Atlantic Records, they made a comeback with the album Start of a Romance, producing two number one R&B singles, "Start of a Romance" and "Real Love." "Real Love" also peaked at number 47 on the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1990. Their final studio album, Nearer to You, was released in 1992.

The Dunning sisters have continued to perform, including a notable 2007 attempt to set a Guinness World Record for the largest kazoo band at the Summerstage Concert Series in Harlem. They have also participated in the Salsoul Reunion Concert in New York City.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Ernest Tidyman wins the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for The French Connection (1971) – presented by Tennessee Williams; introduced by Jack Lemmon

Despite a brief problem with the teleprompter and his lack of experience reading off of one, playwright Tennessee Williams (A Streetcar Named Desire, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) was game to present Adapted Screenplay at the 44th Academy Awards.

That year’s winner would be Ernest Tidyman for the neo-noir film The French Connection, adapting Robin Moore’s 1969 non-fiction book of the same name. The film follows two New York Police Department (NYPD) detectives - Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle (Gene Hackman) and Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (Roy Scheider) - in pursuit of a French drug smuggler.

Also known for his screenplays to the blaxploitation film Shaft (1971) and the the sequel, Shaft’s Big Score (1972), Tidyman walked home with the Oscar on his only career nomination. In total, The French Connection was nominated for eight Academy Awards including Best Sound, Cinematography, and Supporting Actor (Scheider). The film won five times: Film Editing (Gerald B. Greenberg), Adapted Screenplay (Tidyman), Actor (Hackman), Director (William Friedkin), and Best Picture.

#The French Connection#Ernest Tidyman#Tennessee Williams#Jack Lemmon#44th Academy Awards#Oscars#31 Days of Oscar

0 notes

Photo

Movie #46 of 2020: Apocalypse Now

“The horror, the horror.”

#apocalypse now#1979#francis ford coppola#John Milius#michael herr#joseph conrad#carmine coppola#vittorio storaro#lisa fruchtman#gerald b. greenberg#walter murch#drama#mystery#war#english#french#vietnamese#16mm#35mm#anamorphic#todd-ao#technovision#46

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Apocalypse Now (1979)

“I watched a snail crawl along the edge of a straight razor.”

Country: United States

Directed by: Francis Ford Coppola

Written by: Coppola & John Milius

Narration by: Michael Herr

Based on the novella “Heart of Darkness” by: Joseph Conrad

Cinematography by: Vittorio Storaro

Edited by: Walter Murch, Gerald B. Greenberg & Lisa Fruchtman

Produced by: Coppola & Kim Aubry

Music by: Francis Ford & Carmine Coppola

Production Design by: Dean Tavoularis

#Apocalypse Now#Movie#United States#Francis Ford Coppola#John Milius#Michael Herr#Joseph Conrad#Heart of Darkness#Vittorio Stotaro#Walter Murch#Gerald B. Greenberg#Lisa Fruchtman#Kim Aubry#Carmine Coppola#Dean Tavoularis#United Artists#Paramount Home Video#Miramax#1970s#War#Antiwar#Drama#Adventure

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

AWAKENINGS (1990)

We do not know what we see when we look at Leonard. We think we see a human vegetable, a peculiar man who has been frozen in the same position for 30 years, who neither moves nor speaks. What goes on inside his mind? Is he thinking in there? Of course not, a neurologist says in Penny Marshall's new film "Awakenings." Why not? "Because the implications of that would be unthinkable." Ah, but the expert is wrong, and inside the immobile shell of his body, Leonard is still there. Still waiting.

Leonard is one of the patients in the "garden," a ward of a Bronx mental hospital that is so named by the staff because the patients are there simply to be fed and watered. It appears that nothing can be done for them. They were victims of the great "sleeping sickness" epidemic of the 1920s, and after a period of apparent recovery they regressed to their current states. It is 1969. They have many different symptoms, but essentially they all share the same problem: They cannot make their bodies do what their minds desire. Sometimes that blockage is manifested through bizarre physical behavior, sometimes through apparent paralysis.

One day a new doctor comes to work in the hospital. He has no experience in working with patients; indeed, his last project involved earthworms. Like those who have gone before him, he has no particular hope for these ghostly patients, who are there and yet not there. He talks without hope to one of the women, who looks blankly back at him, her head and body frozen. But then he turns away, and when he turns back she has changed her position — apparently trying to catch her eyeglasses as they fell. He tries an experiment. He holds her glasses in front of her, and then drops them. Her hand flashes out quickly and catches them.

Yet this woman cannot move through her own will. He tries another experiment, throwing a ball at one of the patients. She catches it. "She is borrowing the will of the ball," the doctor speculates. His colleagues will not listen to this theory, which sounds suspiciously metaphysical, but he thinks he's onto something. What if these patients are not actually "frozen" at all, but victims of a stage of Parkinson's Disease so advanced that their motor impulses are cancelling each other out—what if they cannot move because all of their muscles are trying to move at the same time, and they are powerless to choose one impulse over the other? Then the falling glasses or the tossed ball might be breaking the deadlock!

This is the great discovery in the opening scenes of "Awakenings," preparing the way for sequences of enormous joy and heartbreak, as the patients are "awakened" to a personal freedom they had lost all hope of ever again experiencing — only to find that their liberation comes with its own cruel set of conditions. The film, directed with intelligence and heart by Penny Marshall, is based on a famous 1972 book by Oliver Sacks, the British-born New York neurologist whose (ital) The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (unital) is a classic of medical literature. These were his patients, and the doctor in the film, named Malcolm Sayer and played by Robin Williams, is based on him.

What he discovered in the summer of 1969 was that L-DOPA, a new drug for the treatment of Parkinson's Disease, might in massive doses break the deadlock that had frozen his patients into a space-time lock for endless years. The film follows some 15 of those patients, particularly Leonard, who is played by Robert De Niro in a virtuoso performance. Because this movie is not a tearjerker but an intelligent examination of a bizarre human condition, it's up to De Niro to make Leonard not an object of sympathy, but a person who helps us wonder about our own tenuous grasp on the world around us.

The patients depicted in this film have suffered a fate more horrible than the one in Poe's famous story about premature burial. If we were locked in a coffin while still alive, at least we would soon suffocate. But to be locked inside a body that cannot move or speak — to look out mutely as even our loved ones talk about us as if we were an uncomprehending piece of furniture! It is this fate that is lifted, that summer of 1969, when the doctor gives the experimental new drug to his patients, and in a miraculous rebirth their bodies thaw and they begin to move and talk once again, some of them after 30 years of self-captivity.

The movie follows Leonard through the stages of his rebirth. He was (as we saw in a prologue) a bright, likeable kid, until the disease took its toll. He has been on hold for three decades. Now, in his late 1940s, he is filled with wonder and gratitude to be able to move around freely and express himself. He cooperates with the doctors studying his case. And he finds himself attracted to a the daughter (Penelope Ann Miller) of another patient. Love and lust stir within him for the first time.

Dr. Sayer, played by Williams, is at the center of almost every scene, and his personality becomes one of the touchstones of the movie. He is shut off, too: by shyness and inexperience, and even the way he holds his arms, close to his sides, shows a man wary of contact. He really was happier working with those earthworms. This is one of Robin Williams' best performances, pure and uncluttered, without the ebullient distractions he sometimes adds — the schtick where none is called for. He is a lovable man here, who experiences the extraordinary professional joy of seeing chronic, hopeless patients once again sing and dance and greet their loved ones.

But it is not as simple as that, not after the first weeks. The disease is not an open-and-shut case. And as the movie unfolds, we are invited to meditate on the strangeness and wonder of the human personality. Who are we, anyway? How much of the self we treasure so much is simply a matter of good luck, of being spared in a minefield of neurological chance? If one has no hope, which is better: To remain hopeless, or to be given hope and then lose it again? Oliver Sacks' original book, which has been reissued, is as much a work of philosophy as of medicine. After seeing "Awakenings," I read it, to know more about what happened in that Bronx hospital. What both the movie and the book convey is the immense courage of the patients and the profound experience of their doctors, as in a small way they reexperienced what it means to be born, to open your eyes and discover to your astonishment that "you" are alive.

— Rober Ebert

CAST: Robert De Niro as Leonard Lowe; Robin Williams as Dr. Malcolm Sayer; Julie Kavner as Eleanor Costello; Ruth Nelson as Mrs. Lowe; John Heard as Dr. Kaufman; Penelope Ann Miller as Paula and Alice Drummond as Lucy.

Drama | Rated PG-13 | 121 minutes | December 20, 1990.

DIRECTED BY: Penny Marshall

WRITER (BOOK): Oliver Sacks

WRITER: Steven Zaillian

CINEMATOGRAPHER: Miroslav Ondricek

EDITOR: Battle Davis and Gerald B. Greenberg

COMPOSER: Randy Newman

#awakenings#robert de niro#robin williams#julie kavner#ruth nelson#john heard#penelope ann miller#alice drummond#penny marshall#oliver sacks#steven zaillian#miroslav ondricek#battle davis#gerald b. greenberg#randy newman#rober ebert#movie review#film review

0 notes

Photo

Editor Gerald B. Greenberg longtime collaborator of director Brian De Palma cut with editor Bill Pankow one of the finest best films of 1987.

The Untouchables is a story of a Police Taskforce during the prohibition era, the mission is to take down Al Capone, with outstanding performances by Kevin Coster, Sean Connery, and Al Pacino, the film offers a showcase of technical achievements.

One of my favorite moments in the editing of this movie is a scene when one of Al Capone’s helper is been transported by the police to a safe house, using an elevator. Greenberg and Pankow introduce juxtaposition where Oscar Wallace it’s been executed by Nitti, Al Capone’s hitman. The moment last literary 4 seconds, then cut to the heroes reaction after the audience hear the shots.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979).

#apocalypse now (1979)#francis ford coppola#walter murch#vittorio storaro#gerald b. greenberg#lisa fruchtman#dean tavoularis#angelo p. graham#apocalypse now

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

He personified the American West in the days of its rowdy youth.

The Missouri Breaks, Arthur Penn (1976)

#Arthur Penn#Thomas McGuane#Marlon Brando#Jack Nicholson#Randy Quaid#Kathleen Lloyd#Frederic Forrest#Harry Dean Stanton#John McLiam#John P. Ryan#Sam Gilman#Steve Franken#Richard Bradford#Michael C. Butler#John Williams#Dede Allen#Gerald B. Greenberg#Stephen A. Rotter#1976

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Al Pacino in Scarface (Brian De Palma, 1983)

Cast: Al Pacino, Steven Bauer, Michelle Pfeiffer, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Robert Loggia, Miriam Colon, F. Murray Abraham, Paul Shenar, Harris Yulin. Screenplay: Oliver Stone, based on a screenplay by Ben Hecht, Seton I. Miller, John Lee Mahin, W.R. Burnett adapted from a novel by Armitage Trail. Cinematography: John A. Alonzo. Art direction: Edward Richardson. Film editing: Gerald B. Greenberg, David Ray. Music: Giorgio Moroder.

Brian De Palma's Scarface ends with a dedication of the film to Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht, the director and the author of the story for the 1932 Scarface. As well it might, for De Palma's film and Oliver Stone's screenplay follow the outlined action and many of the characters of the earlier film far more closely than many remakes do. Most of the major characters have counterparts in the 1932 film: the Italian Tony Camonte becomes the Cuban Tony Montana; the first Tony's best friend, Guino Rinaldo, becomes Manny Ribera; Tony's sister, Cesca, becomes Gina; his boss Johnny Lovo's mistress, Poppy, becomes Tony Montana's boss Frank Lopez's mistress, Elvira. Both Mama Camonte and Mama Montana are sternly disapproving presences, and the appropriate characters are bumped off in more or less the same sequence and circumstances as in the earlier film. Because of the relaxation of censorship, there's a little heightening of some subtext from the first film: Gina (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) taunts Tony Montana (Al Pacino) with having incestuous feelings for her more explicitly than Cesca ever dares with Tony Camonte. And although the earlier film was thought to be excessively violent, the remake goes boldly where it didn't dare, starting with a chainsaw murder and ending with a veritable orgy of gunfire, including that of Tony's "little friend," a grenade launcher. The violence of De Palma's film first earned it an X rating, which was bargained down to an R after some suggested cuts -- although De Palma has claimed that he actually released the film without the cuts, and no one noticed. The remake's violence also turned off many of the critics, although it received a strong thumbs up from Roger Ebert. Since then, of course, the movie has become a cult classic, and more people have seen the remake than have ever seen the original. Which is a shame, because the original, despite some occasional slack pacing and the inevitable antique feeling that lingers in even pre-Production Code movies, is a genuine classic, while De Palma's version feels like a rather studied attempt to go over the top. Screenwriter Stone was never noted for subtlety, and while Al Pacino is one of the great movie actors, De Palma lets him venture into self-caricature, especially with what might be called his Cubanoid accent. On the other hand, Steven Bauer -- who was born in Cuba and sounds nothing like Pacino's Tony -- is a more appealing sidekick than George Raft was, and Michelle Pfeiffer, in one of her first major film roles, makes a good deal more of Elvira than Karen Morley did of Poppy, even though Pfeiffer is asked to do little more than look beautifully sullen and bored throughout the film. Scarface is at best a trash classic, a movie whose impact is stronger than one wants it to be.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Link

A Letter on Justice and Open Debate

July 7, 2020

The below letter will be appearing in the Letters section of the magazine’s October issue. We welcome responses at [email protected]

“Our cultural institutions are facing a moment of trial. Powerful protests for racial and social justice are leading to overdue demands for police reform, along with wider calls for greater equality and inclusion across our society, not least in higher education, journalism, philanthropy, and the arts. But this needed reckoning has also intensified a new set of moral attitudes and political commitments that tend to weaken our norms of open debate and toleration of differences in favor of ideological conformity. As we applaud the first development, we also raise our voices against the second. The forces of illiberalism are gaining strength throughout the world and have a powerful ally in Donald Trump, who represents a real threat to democracy. But resistance must not be allowed to harden into its own brand of dogma or coercion—which right-wing demagogues are already exploiting. The democratic inclusion we want can be achieved only if we speak out against the intolerant climate that has set in on all sides.

The free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted. While we have come to expect this on the radical right, censoriousness is also spreading more widely in our culture: an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty. We uphold the value of robust and even caustic counter-speech from all quarters. But it is now all too common to hear calls for swift and severe retribution in response to perceived transgressions of speech and thought. More troubling still, institutional leaders, in a spirit of panicked damage control, are delivering hasty and disproportionate punishments instead of considered reforms. Editors are fired for running controversial pieces; books are withdrawn for alleged inauthenticity; journalists are barred from writing on certain topics; professors are investigated for quoting works of literature in class; a researcher is fired for circulating a peer-reviewed academic study; and the heads of organizations are ousted for what are sometimes just clumsy mistakes. Whatever the arguments around each particular incident, the result has been to steadily narrow the boundaries of what can be said without the threat of reprisal. We are already paying the price in greater risk aversion among writers, artists, and journalists who fear for their livelihoods if they depart from the consensus, or even lack sufficient zeal in agreement.

This stifling atmosphere will ultimately harm the most vital causes of our time. The restriction of debate, whether by a repressive government or an intolerant society, invariably hurts those who lack power and makes everyone less capable of democratic participation. The way to defeat bad ideas is by exposure, argument, and persuasion, not by trying to silence or wish them away. We refuse any false choice between justice and freedom, which cannot exist without each other. As writers we need a culture that leaves us room for experimentation, risk taking, and even mistakes. We need to preserve the possibility of good-faith disagreement without dire professional consequences. If we won’t defend the very thing on which our work depends, we shouldn’t expect the public or the state to defend it for us.”

Elliot Ackerman

Saladin Ambar, Rutgers University

Martin Amis

Anne Applebaum

Marie Arana, author

Margaret Atwood

John Banville

Mia Bay, historian

Louis Begley, writer

Roger Berkowitz, Bard College

Paul Berman, writer

Sheri Berman, Barnard College

Reginald Dwayne Betts, poet

Neil Blair, agent

David W. Blight, Yale University

Jennifer Finney Boylan, author

David Bromwich

David Brooks, columnist

Ian Buruma, Bard College

Lea Carpenter

Noam Chomsky, MIT (emeritus)

Nicholas A. Christakis, Yale University

Roger Cohen, writer

Ambassador Frances D. Cook, ret.

Drucilla Cornell, Founder, uBuntu Project

Kamel Daoud

Meghan Daum, writer

Gerald Early, Washington University-St. Louis

Jeffrey Eugenides, writer

Dexter Filkins

Federico Finchelstein, The New School

Caitlin Flanagan

Richard T. Ford, Stanford Law School

Kmele Foster

David Frum, journalist

Francis Fukuyama, Stanford University

Atul Gawande, Harvard University

Todd Gitlin, Columbia University

Kim Ghattas

Malcolm Gladwell

Michelle Goldberg, columnist

Rebecca Goldstein, writer

Anthony Grafton, Princeton University

David Greenberg, Rutgers University

Linda Greenhouse

Rinne B. Groff, playwright

Sarah Haider, activist

Jonathan Haidt, NYU-Stern

Roya Hakakian, writer

Shadi Hamid, Brookings Institution

Jeet Heer, The Nation

Katie Herzog, podcast host

Susannah Heschel, Dartmouth College

Adam Hochschild, author

Arlie Russell Hochschild, author

Eva Hoffman, writer

Coleman Hughes, writer/Manhattan Institute

Hussein Ibish, Arab Gulf States Institute

Michael Ignatieff

Zaid Jilani, journalist

Bill T. Jones, New York Live Arts

Wendy Kaminer, writer

Matthew Karp, Princeton University

Garry Kasparov, Renew Democracy Initiative

Daniel Kehlmann, writer

Randall Kennedy

Khaled Khalifa, writer

Parag Khanna, author

Laura Kipnis, Northwestern University

Frances Kissling, Center for Health, Ethics, Social Policy

Enrique Krauze, historian

Anthony Kronman, Yale University

Joy Ladin, Yeshiva University

Nicholas Lemann, Columbia University

Mark Lilla, Columbia University

Susie Linfield, New York University

Damon Linker, writer

Dahlia Lithwick, Slate

Steven Lukes, New York University

John R. MacArthur, publisher, writer

Susan Madrak, writer

Phoebe Maltz Bovy, writer

Greil Marcus

Wynton Marsalis, Jazz at Lincoln Center

Kati Marton, author

Debra Mashek, scholar

Deirdre McCloskey, University of Illinois at Chicago

John McWhorter, Columbia University

Uday Mehta, City University of New York

Andrew Moravcsik, Princeton University

Yascha Mounk, Persuasion

Samuel Moyn, Yale University

Meera Nanda, writer and teacher

Cary Nelson, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Olivia Nuzzi, New York Magazine

Mark Oppenheimer, Yale University

Dael Orlandersmith, writer/performer

George Packer

Nell Irvin Painter, Princeton University (emerita)

Greg Pardlo, Rutgers University – Camden

Orlando Patterson, Harvard University

Steven Pinker, Harvard University

Letty Cottin Pogrebin

Katha Pollitt, writer

Claire Bond Potter, The New School

Taufiq Rahim

Zia Haider Rahman, writer

Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, University of Wisconsin

Jonathan Rauch, Brookings Institution/The Atlantic

Neil Roberts, political theorist

Melvin Rogers, Brown University

Kat Rosenfield, writer

Loretta J. Ross, Smith College

J.K. Rowling

Salman Rushdie, New York University

Karim Sadjadpour, Carnegie Endowment

Daryl Michael Scott, Howard University

Diana Senechal, teacher and writer

Jennifer Senior, columnist

Judith Shulevitz, writer

Jesse Singal, journalist

Anne-Marie Slaughter

Andrew Solomon, writer

Deborah Solomon, critic and biographer

Allison Stanger, Middlebury College

Paul Starr, American Prospect/Princeton University

Wendell Steavenson, writer

Gloria Steinem, writer and activist

Nadine Strossen, New York Law School

Ronald S. Sullivan Jr., Harvard Law School

Kian Tajbakhsh, Columbia University

Zephyr Teachout, Fordham University

Cynthia Tucker, University of South Alabama

Adaner Usmani, Harvard University

Chloe Valdary

Helen Vendler, Harvard University

Judy B. Walzer

Michael Walzer

Eric K. Washington, historian

Caroline Weber, historian

Randi Weingarten, American Federation of Teachers

Bari Weiss

Sean Wilentz, Princeton University

Garry Wills

Thomas Chatterton Williams, writer

Robert F. Worth, journalist and author

Molly Worthen, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Matthew Yglesias

Emily Yoffe, journalist

Cathy Young, journalist

Fareed Zakaria

0 notes

Photo

GERALD.B.GREENBERG (1922-Died December 22nd 2017.at 81).American film editor who worked on films such as Apocalypse Now,Scarface and his Academy & BAFTA award winning work on The French Connection.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_B._Greenberg

0 notes

Text

Anonymous Artists Boycott American University

On 3 January, 2017, American University proved that it is incapable of handling art to the standard of any competent arts institution. According to the school, neither they nor the Department of Homeland Security, whose national headquarters overlook the campus plaza where a statue of Leonard Peltier was officially welcomed to American University on December 9, 2016, could adequately protect this piece from... American University.

In collusion with a group identifying themselves only as a self-organized anonymous group of FBI employees, American University merely stated that the statue was the target of some conspiracy and destroyed it. They did not hunt down evildoers or file charges. They did not analyze the threat and take steps to prevent it. They merely trotted out the Vietnam War era dictum “we had to destroy it in order to save it.”

The DHS did not reveal a plot against it or announce the indictment of the villains who are rumored to have wished to do it harm. In fact, no evidence was presented whatsoever.

It isn't like no one has ever uninstalled a sculpture before; there are ways of doing it. But the college did not contact the artist, Rigo 23, to make arrangements for another space. They did not put it into storage where, presumably, it might have been safe from the sensitive eyes of unnamed people who issue nebulous threats on the say-so of a group devoid of legal authority. They did not employ curators experienced in the safe handling and transport of artwork, though there is an art museum on campus and the university offers full art studio and history programs through the PhD.

No, instead they beheaded and dismembered a figurative work of art and threw the pieces in the garbage. A chainsaw could save art, while the Department of Homeland Security could not, despite having a building full of their top brass across the street.

And yet, apparently, the act isn't motivated by the school wanting to censor the subject, because American University had a symposium on Leonard Peltier not a month previously; it was not canceled or disrupted by either poison-pen correspondents or the campus authorities. So, it would seem, it is not a matter of the politics of the artwork. That leaves only one alternative: they deliberately chose to destroy art because it is art.

This makes it fraught for an artist to install a piece in any location in the United States, given that they would presumably be even more difficult for our security state to protect than right outside their front door. It is a caution for the students, faculty and other visitors to any American college that they are so vulnerable that the only way to prevent violence is to commit exactly the same violence, just do it before some moustache-twirling villain does. It is daunting to consider the career prospects of a student who attains an advanced degree in art history from an institution that has demonstrated such ignorance of the basic handling of artwork.

As artists, we are obligated to protect what we create to the extent we can. American University has proven that it is not a trustworthy custodian of art, so we cannot in good conscience allow ours to fall into such unscrupulous hands. We will not sell, donate, loan or otherwise allow our work to be exposed to all manner of hazards by American University's ethical and moral degeneracy. We will not attend events or exhibits at Katzen Arts Center, Greenberg Theater or any other affiliate of the institution. We have no confidence that Neil Kerwin, Janice Menke Abraham, Gina Adams and the other trustees of the college listed below hold art in any higher regard than a piece of litter to be speared at the end of a pointy stick, so they are no longer eligible buyers of our work personally or at the other institutions where they hold positions.

Art is stronger than any one person or institution, and such cowardly acts bring shame upon you. You may think destroying is powerful, but you are wrong. Any idiot with a chainsaw can destroy. Creation is powerful, and only artists can do that.

You can chop up a thousand pieces of art, but as long as there are humans, there will always be number 1,001. Like a candle in the darkness, art exposes the bankruptcy of mindless destruction like yours because it is the light of humanity.

We choose anonymity. Not because we cannot produce evidence to back up specious lies, like the FBI agents who make up excuses for their mindless need to destroy, but to protect ourselves from the most powerful security state on the planet in the employ of mindless destruction. You will never know who all of us are, but we know who you are. And you will not get our art.

Board of Trustees of American University

Janice Menke Abraham

Gary M. Abramson

Gina F. Adams

Stephanie M. Bennett-Smith

Gary D. Cohn

Pamela M. Deese

Hani M.S. Farsi

Thomas A. Gottschalk

Gisela B. Huberman

Margery Kraus

Gerald Bruce Lee

Ross B. Levinsohn

Fernando Lewis Navarro

Charles H. Lydecker

Betsy A. Mangone

Alan L. Meltzer

Arthur J. Rothkopf

Peter L. Scher

Jeffrey A. Sine

David Trone

Kim Cape

LaTrelle Easterling

Cornelius M. Kerwin

We do not forgive. We do not forget.

2 notes

·

View notes