#IFFR2017

Photo

February 2017, Rotterdam Coffee @ CoffeeCompany during IFFR International FilmFestival Rotterdam

0 notes

Text

rEvolutions

In a post-2016 world, does the future look bright to you? How about the future of cinema? Just how much zeal for radical change a festival line-up can contain is examining our editor Yoana Pavlova – at International Film Festival Rotterdam, of course, where else...

Think pieces like this one are usually titled “The kids are all right,” or “The kids are not all right” – depending on the political sharpness honorable authors want to imbue their prose with. This is even more valid when the text is on cinema, young people in cinema, and/or millennials as protagonists.

One of those forever-young events that can serve as a fieldwork to research the next generation and its audiovisual tropes is International Film Festival Rotterdam. Albeit being 46-year-old, the Dutch festival had long figured out the recipe for eternal youth: #1 stay curious to fresh formats, media, and technologies #2 favor rebellious narratives #3 repeat. The easiest way to discover upcoming trends at IFFR is the Bright Future section, a showcase for “major new talents.” And judging from several titles in this year's line-up, all written and directed by upcoming authors in their late 20s or in their early 30s, kids are plotting a revolution, or at least something that looks like it.

With an international premiere plus web series and installation, Anaïs Volpé's HEIS was probably the most visible face of young French cinema in Rotterdam. Dubbed the “French Lena Dunham” in the catalogue was not precisely in her favor, as Lena Dunham's name has some very complex connotations outside of France, where she is wholeheartedly adored as an indie goddess with easygoing yet unlimited creative potential. Still and all, Volpé's HEIS tells a very important story about the young people in France, who, as the film claims, moved directly from feeding bottles to unemployment doles. As of 2016, it is believed that Bertrand Bonello has the patent to speak of social unrest and political catharsis in France, and as a matter of fact his NOCTURAMA (2016) was also shown at IFFR accompanied by a discussion. Nevertheless, HEIS is far more sincere than Bonello's film, and has the advantage of being produced by someone who has more or less the same age as NOCTURAMA's personages whose actual motivation to set Paris on fire remains an enigma up until the dramatic end.

In addition, Volpé stars in her own project, thus crafting HEIS' docufiction plot with bits and pieces of her own autobiography, as well as personal fantasies, cultural references, pop-culture clichés, key geopolitical topoi. From Claude Chabrol's THE GOOD TIME GIRLS / LES BONNES FEMMES (1960) to Mathieu Kassovitz's LA HAINE (1995), the storyline and the visuals play with allusions in the best traditions of XXI-century French cinema, yet it is not neo-Amélie that emerges on the screen but a frenchified Frances Ha, stranger in a familiar land. What is also interesting in HEIS is that unlike so many millennials narratives that are preoccupied with romance, Volpé explores her relationship with her twin-brother vis-à-vis their mother (and the invisible presence of their father), thus charting superposed triangles with an imaginary self. This is how HEIS suggests that rebellion should occur first and foremost within the family, and growing up in a certain way can be an act of revolution too. This self-conscious curatorial approach towards life may put off some viewers who are still hoping for the impromptu power of the French New Wave to be reborn, but it is very effective in displaying the mechanisms that move today's youth.

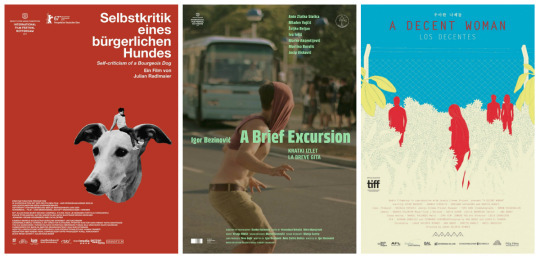

Another Bright Future film, whose director deliberately embedded himself in the spiel with several levels of irony, is SELF-CRITICISM OF A BOURGEOIS DOG / SELBSTKRITIK EINES BÜRGERLICHEN HUNDES (2017) by Julian Radlmaier. A film about shooting a film that makes Berlin hipsters mingle with the proletariat, Radlmaier's work is again a tribute to different directors, such as Werner Schroeter and Rosselini. Self-aware of its interactive scheme, as well as of its auteurish stance, SELF-CRITICISM OF A BOURGEOIS DOG fits the contemporary meme culture that urges many young people to adopt a slogan rhetoric they have no clear understanding of. With a well-articulated notion that solidarity differs from one generation to another, and from one culture to another, the ultra stylish revolution here is led by a mute, sneakers-wearing monk – an agent of Deus-ex-machina resolutions. At IFFR, it proved difficult to corner Radlmaier and obtain a clear statement about his political agenda, yet SELF-CRITICISM OF A BOURGEOIS DOG feels like it is friendly pulling the chain of the contemporary Left.

Another spiritual pilgrimage ushered by a Messiah-like figure unfolds in A BRIEF EXCURSION / KRATKI IZLET (2017) by Igor Bezinović. Narrated in retrospective by protagonist's voice-over, the film seems to tackle a generation of young people who are already adults (which is also to explain how come seven people can get lost in the woods, looking for an abandoned monastery). Nevertheless, the apparent lack of technology and the early-2000s clothes are just an excuse to look into a timeless cycle on the Balkans, in which youth comes to age in the context of the prevalent Dionysian culture, without a chance to analyze the world in a sober manner. Probably this is why A BRIEF EXCURSION is more engaged with literary works than cinema – based on the novel of the same title written by the Croatian Antun Šoljan in 1965, Igor Bezinović's film suits also the magic realism of Milorad Pavić and the quiet existentialism of Francis Scott Fitzgerald. The every-man-for-himself moral here is central, the revolution appears to be a matter of individual, spiritual salvation, and the collective – a utopia.

A slightly different type of Arcadia takes shape in A DECENT WOMAN / LOS DECENTES (2016) by Lukas Valenta Rinner. I attended the world premiere in Sarajevo, where the film was selected in the Official Competition and felt like a fresh breeze amidst the usual Balkan drabness. At first, the Austria / Argentina / South Korea production combo looked confusing in the context of Sarajevo, but then the deadpan humor à la the Greek New Wave turned out to be spot-on. In Latin American cinema, there is already a sub-genre about oppressed house help, yet it is the first time I see this narrative leading to an Epicurean Garden of sorts, only to destroy the paradise of equality and democracy with nihilistic gusto at the end. In Rotterdam, Lukas Valenta Rinner's film was in its natural habitat, but still, bitter jokes and dark fantasies aside, the question is – is a working-class revolution even imaginable nowadays?

If one needs a more realistic answer, maybe one has to look beyond IFFR's Bright Future programme. Some thoughts on two favorites of mine. PEOPLE POWER BOMBSHELL: THE DIARY OF VIETNAM ROSE (2016) by John Torres is a film about gestures, and a gesture per se. Examining the celluloid spirits trapped in the void of the post-colonial past, Torres is rather sceptic when it comes to re-writing history. On the most fragile medium he brings to life the underdeveloped shadows of Filipino cinema, with all political implications involved in this act of redemption, only to look with compassion and sadness at the result. The last feature of Jan Němec is a similar take on existential checks and balances that flows like a literary mystification. Released post-mortem, THE WOLF FROM ROYAL VINEYARD STREET / VLK Z KRÁLOVSKÝCH VINOHRAD (2016) gets even with the Czech New Wave, the French New Wave, festivals, the USA, Trump, and “the left-wing fools.” Footage of Jean-Luc Godard cutting the screen in Cannes in 1968 prompts for parallel with Mark Cousins smashing his DCP with an axe. The medium is no longer the message but the messenger to be shot in order to start a proper revolution. Enter Kafka and the counter-revolution.

If you are a film industry professional, you can watch titles from IFFR's Bright Future selection on Festival Scope

#IFF Rotterdam#IFFR2017#Bright Future#Sarajevo Film Festival#Cannes Film Festival#HEIS#Anaïs Volpé#Nocturama#Bertrand Bonello#Lena Dunham#Frances Ha#Self-Criticism of a Bourgeois Dog#Julian Radlmaier#Werner Schroeter#Roberto Rossellini#A Brief Excursion#Igor Bezinović#Antun Šoljan#Milorad Pavić#Francis Scott Fitzgerald#Los Decentes#Lukas Valenta Rinner#People Power Bombshell#John Torres#The Wolf from Royal Vineyard Street#Jan Němec#Jean-Luc Godard#Mark Cousins#festival report#Yoana Pavlova

0 notes

Photo

Diving into the IFFR 2017. It's fun! #iffr2017 #iffr (at International Film Festival Rotterdam - IFFR)

0 notes

Photo

We’re proud to unveil the poster for Super Dark Times, our first feature film, directed by Kevin Phillips, premiering this week in competition at International Film Festival Rotterdam.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#IFFR #IFFR2017 #PlanetIFFR (at Tyneside Cinema)

0 notes

Video

🔪🍏 Thought it would be nice to share the making off my @iffr apple. Music by @mariade.la.o #PlanetIFFR #IFFR #IFFR2017 #fruitdoodle

0 notes

Photo

And a shoutie outs to these two stunners' @neetjew @donjalon 📽🎬📼 #iffr2017

0 notes

Text

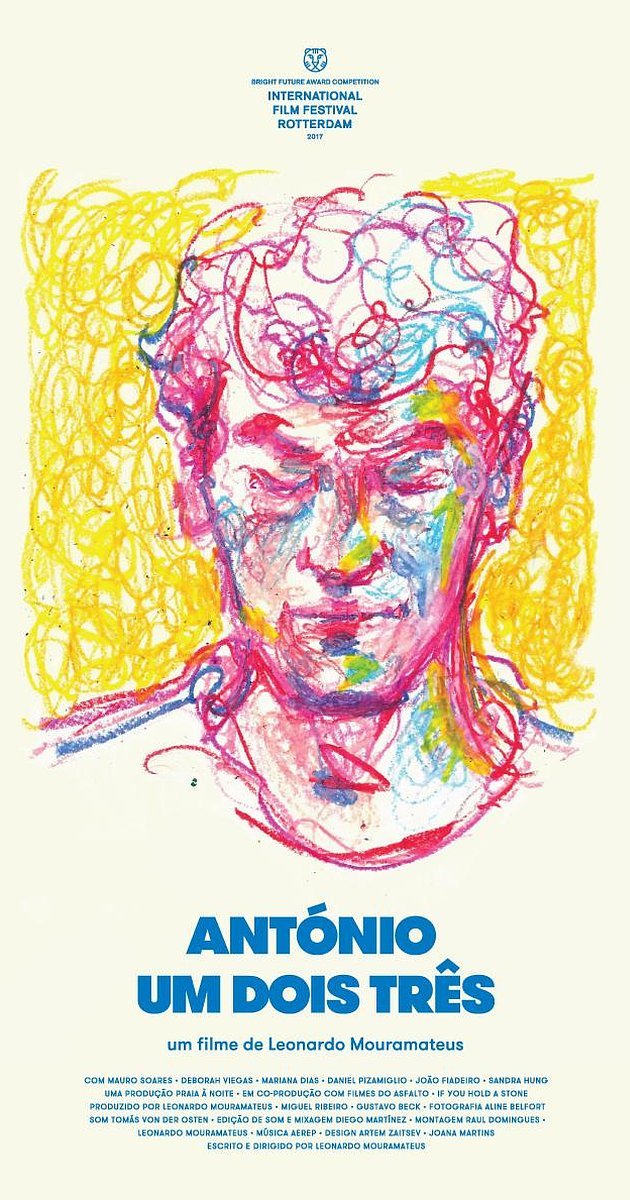

António's spell

When Lola was running on the streets of Berlin in 1998, it was the cyber-excitement for interactive storytelling that repositioned her again and again on the starting point, up until the happy end. In the Lisbon-set ANTÓNIO ONE TWO THREE / ANTÓNIO UM DOIS TRÊS (2017) by Leonardo Mouramateus (part fairy tale of a self-made man, part millennials romance, part austerity challenge), the eponymous protagonist seems to run towards a three-act change. Our new contributor Andreea Pătru met in Rotterdam the director of this charming feature debut and his film star Mauro Soares in order to deconstruct António's agenda. Three, two, one – start!

Leonardo Mouramateus is a young film director, already known for several highly acclaimed shorts. His MAURO IN CAYENNE / MAURO EM CAIENA (2013) and THE PARTY AND THE BARKING / A FESTA E OS CÃES (2015) both won the Best Short Film prize at Cinéma du Réel, and STORY OF A FEATHER / HISTÓRIA DE UMA PENA (2015) screened at Locarno Film Festival. Born in Brazil, Fortaleza, he shot his first feature ANTÓNIO ONE TWO THREE / ANTÓNIO UM DOIS TRÊS (2017) in Lisbon, where he currently resides.

I had a chance to speak with Leonardo Mouramateus, and Mauro Soares, who played António, was kind enough to translate and participate in our conversation at IFFR, where the film premiered in the Bright Future Competition. Working with the possibilities of multiple representations of its protagonist, the director parted the film in three segments that delicately influence and interact with each other. In this triptych, not only the protagonist’s personality changes, the surroundings and his peers are also given slightly different roles. The film reaches its full potential as a whole because of the strengthened interrelation between its units, giving sense to isolated sequences that fit better into the bigger picture.

António is a student who leaves university to follow his own path in Lisbon, hiding away from his father at his ex-girlfriend’s apartment, a place where he has been the most happy. Leonardo Mouramateus’ film moves away from the conventional and classical narrative forms, and dares to approach a fresh and subversive type of plot. He controls very well the dramatic shifts in his stories by mastering a cinematic grammar of his own, a unique approach for a debut. The film depicts the youthful feelings and connects the constant evolution of its characters with the instability of the millennials’ world.

Andreea Pătru: In the description of your film, you state that the movie is inspired by Dostoevsky’s short story White Nights. To what extent did that work influence yours?

Leonardo Mouramateus: The movie is not directly an adaptation of the work, it is influenced as much as it is from the work of other authors like the poem of Nicanor Parra, Roberto Bolaño, a novelist that I really enjoy. I could talk about the influence of not only writers, but also from music or other pieces of cinema, like Charlot, because my protagonist is a little bit like him, and Lubitsch.

Maybe Dostoevsky gained a little bit more attention because in the movie the director chose to adapt it for his theatre play too… and also because it was very fit for the things we wanted to talk about – youth, dreams…

AP: The main character plays various roles, but the majority are related to theatre. Why theatre, what is your relation with this art?

LM: Before cinema, I made theatre in Fortaleza, so for me it was the starting point to get used to a certain type of language, to work with a group and collaborate. Also, a lot of the people, with whom I work now, are related to theatre. I liked it because you can also express with your body, make jokes, the mise-en-scène, even if you are poor. Moreover, the theatre exerts a power over the imagination that interests me in cinema, its limitations are tools to explore my creativity.

One of the most important things was my contact with João Fiadeiro, the actor who plays the father in the film. He is also a great choreographer, I got in touch with his system through one of his workshops, and I learnt about realtime composition. Even if it is not that strict of a method, it made me think of the self-sufficiency, of composition, and construction without the author as the master. Everybody, all the parts of the crew are important. Also, theatre appears in my film for its capacity of reconstruction and also because of its lively creativity, you can watch how ideas are born, and I also liked to illustrate the process.

AP: The three-part story you have chosen is an interesting tool for developing your plot. The stories merge into one another by repeating the characters, yet giving them different character development, to the point we do not know which story is the real one. Which was the first part you have developed?

LM: We shot the movie as it is presented, in the exact same order: one, two, three. After I shot the first part, we stopped for six months, and so on after each part. I do not know how would have looked if I changed the order, because I never experienced it. Maybe chronologically it wouldn’t be so visible, but the changes in the development of the character would be affected. There is something that changes and grows from the beginning to the end. For instance, in the first part we present the characters, in the second part there are other questions for António, and in the third one his issues from the previous parts are explored and get solved.

Mauro Soares: An observation, if I may: in a way, the character develops through the stories, since in the first one he has no perspectives whatsoever, then he goes from being a technician to the director of the theatre play.

LM: Yes, exactly. And somehow everything and nothing changes, because the only thing that changes is António. He crosses the three segments in an almost linear way, because we can assume he learnt something. He left school, but he knows enough to become a technician, and then because he lives in that basement and he is always there at the rehearsals, he also learnt something about acting, so that he can direct in the third part. So to me they are all linked in this way.

AP: Did any production limits restrict your intentions for António’s versions?

LM: Since I started making movies, the production and the writing were very well connected. To me the two come together and function together, they are not restricted to one another. To me, it is not important to put something crazy in the movie, like a whale or something. I am not attracted to far-away scientific experiences, I like to express what is important to me. I am attracted to words, funny little jokes, love stories, how people react when they are mad… and I have put that in my films.

AP: Talking about production and the formal structure of this story, how did the editing influence your previous intentions from the shooting?

LM: Since we had so much time in-between the shootings, we put the parts together so that we could follow the influences from the first part to the second one and so on. Even if sometimes things did not go as planned, one option was to change that, or even better, we thought of ways we could assume that and use those problems in our favor and put them in the film. Sometimes an error or an extra take were exactly what we needed. Because I could write after the previous part, I felt I can introduce something that did not feel well-fitted into the first one and make it work.

MS: For instance, I remember, when we were rehearsing, and we talked about the thing that António smiled when he ran away from his father, we thought the scene would be too heavy, and we did not want such drama. The intention was to have some youth to it, not like an inter-generational fight between father and son, so I proposed I could smile.

LM: Yeah, and I used this scene that otherwise looked intriguing as a discussion in the theatre group in the second part. These things inspire me, and I put them in the script accordingly. We were creating the film while it was creating us. I was an organically project that grew with us through the process.

AP: How would you describe the relation between reality and fiction for your own characters?

LM: There are no imaginary versions of António’s story, everything is reality. There is not one valid version and the other ones – dreams. The point is that, to me, the reality is not single-layered. Of course, maybe I can create an António four for five, but all these layers are as important to me as the first one. I intermingled António’s life with aspects from his play, because I had no desire to separate life from theatre. There is no lie or truth. To me, it is important to notice while watching it that everything is present.

MS: If there is a character that could be a little bit more aware of these different layers of reality, it is the neighbor, because she could cross all the stories. She is also passionate about tarot, maybe the cards can read the other dimensions, she can predict. [laughs]

LM: Yeah, because the same could be said about us as the creators of this film. There is also some kind of António plot that is also about us as filmmakers. The reality is composed through this metalinguistic declinations of the plot.

AP: Did you have in mind the same actor for all the three stories from the beginning?

LM: No. Firstly, because when I met Mauro I saw he has a tremendous talent in playing a variety of characters, and he was exactly what I needed, a comedy brunette guy. Another point is that there is only one António, even if he is present in three parts. It is the same character in different situations, reacting differently to the given environment and its changes. In some way, António is also a little bit like Johnnie, a guy who is heartbroken, and also Deborah in some way is like him, because she also left university. The most logical profile to me is that there is something of António in other characters, because he is not a single-sided character.

AP: Was it a challenge for you to re-direct these scenes in a different way?

LM: No, not actually. I had this idea of directing, and I knew some things would have to change from the first to the last part. But the things I wanted to change were very practical. Not only directing the actors, but also the mise-en-scène, the crew. For instance, in the first part António is more lonely, he does not interact that much, the relations are more closed. In the second part appears Johnny, that is like a mirror image of António, so I have to pull back the camera to fit these two people. The crew understood they have to mould, not only by my ideas but other factors, too. Aline Belfort, the photographer of the film, had to adapt too, because the parts were shot in different seasons, we started in winter, and the second part was shot in summer. She had to adapt to make all these changes in the way she was dealing with light, because of the materiality of what we were doing.

AP: How was for you the transition from short films to features?

LM: It came naturally, because my shorts were already lengthy, I have shot shorts of 30 minutes. In a way, you can think of my movie as a collection of three shorts, it is some kind of homage, although it is not a short film. Its rhythm, the approach is different. There is always this pressure for us, shorts filmmakers, when would we direct a feature. Like a grand transition should be expected. I was at this Mariano Llinás’ Anti-lab, and he was speaking exactly about young filmmakers that go through all sorts of workshops, mentoring, trainings, project development labs, and their scripts are destroyed by many experts. For me, it was important to start the project without this pressure and grow it organically.

AP: The iconic song I Put a Spell on You is a key diegetic piece in each of these parts of your film. Why did you choose to make the character sing it, and was its purpose within the work?

MS: Leonardo wanted to see me in the theatre, and he heard me sing a song from Jaques Brel – Ces Gens-Là. It was a very romantic moment, appropriate for the feeling of his film, so he wanted me to sing it in the movie. I did not want to repeat myself, since I was already working on the same piece for the play, so we chose Nina Simone’s I Put a Spell on You. [cover of Screamin' Jay Hawkins’ original]

LM: And also it was maybe the most important element to connect the parts. The song crosses over. It was not thought of before since I did not have the script for the second segment, yet it naturally stand out as an element to link. At our second screening here, a music teacher from Amsterdam came and said that to him the film has the structure of music. I liked this comparison, I do not create films with the structure of a song in mind, but I like to use the structure of a song to help me deliver my film. The electronic music that accompanies the images was also very specifically placed, the beat having to come in a specific moment and taking into account these details.

AP: Could you please expand a little about the relationship between Johnny and António? Is it symbolic, like putting Brazil and Portugal in comparison, since like the character, you also emigrated?

LM: Not really, but the Brazilians and the Portuguese will always have their differences. My personal experience inspired me to put this into film.

MS: It is interesting, because Johnny is also a Brazilian director who goes to Lisbon to direct his first big thing. He wanted somehow not to prove himself, but to produce something that is significant. He is his alter ego, in a way… [laughs]

AP: Yes, but to me, all the characters oscillate between Portugal and Brazil. They all seem to go or return from somewhere. António seems to be the only stable element, why did you choose that?

LM: I never thought about it that way, but António has no problems with going or staying in. It is Johnny’s and Deborah’s issue. That is not a question for António. He just wanted to be independent in Lisbon, living without his father’s support, without money, without even a home… in a way, he does an extreme gesture.

AP: You were commenting about his social condition and him not having money, and there are these screwball comedy elements in your movie. Do you feel that this style, which goes back to the Big Depression, is still actual to comment on the social conditions nowadays?

LM: The point of these comedies was not documentary, although it was meant to comment about the United States at that moment, and how money controls our lives and the way we think our relationships… Like in the comedies of Lubitsch, a comedy like NINOTCHKA (1939) is absolutely amazing and very actual. It is not only a satirical critique of communism but also comments on capitalism, and all of this while it is a dialogical film about love, love as a great principle, a political one also. I think that considering nowadays’ situation this is radical.

AP: Does the Portuguese or Brazilian cinema inspire you?

LM: I have always been moved by filmmakers like Eduardo Coutinho, or Pedro Costa, or Ernst Lubitsch, you know. Chaplin is also important to me. But before filming, we watched two important shorts. One was João César Monteiro’s WHO WAITS FOR THE DECEASED’S SHOES DIES BAREFOOT / QUEM ESPERA POR SAPATOS DE DEFUNTO MORRE DESCALÇO (1970), a film that also has a poor protagonist, wandering around in Lisbon, also heartbroken, like António… And it was also this other one about two guys who don’t have money to go to the cinema in Sao Paulo, so they do not enter, they just read the list of films, inspect the posters. I liked the feeling of these stories, it was very similar in a way with the plot that I was developing for ANTÓNIO ONE TWO THREE.

AP: I wanted to ask you if you have seen the films of Hong Sang-soo? He is also interested in these slightly different changes of plot. Do you want to pursue something as intransigent?

LM: Yes, I admire his work, and I think RIGHT NOW, WRONG THEN / JIGEUMEUN MATGO GEUTTAENEUN TEULLIDA (2015) is an amazing film, but there are other directors that followed this path also, like Alain Resnais. I think that my influences are more from the literature, that is why I have chosen an adaptation as an excuse to explore different narratives. I have heard Hong Sang-soo showed what he filmed to the actors. In a way I avoided that at the beginning, because I was a little bit skeptical about it, I did not want the actors to close the character’s development. But in a way it was good because everybody contributed to the story. Even the photographer, Aline Belfort, she is Brazilian, but she went to Russia to study photography, and she returned to Lisbon to shoot our film. So her personal story coincides with Deborah’s.

If you are a film industry professional, you can watch ANTÓNIO ONE TWO THREE on Festival Scope

#IFF Rotterdam#IFFR2017#Cinéma du Réel#Locarno FF#Pardo#Bright Future#Ibero-American cinema#Brazil#Lisbon#António One Two Three#Leonardo Mouramateus#Mauro Soares#Right Now Wrong Then#Hong Sang-soo#Nicanor Parra#Roberto Bolaño#Fyodor Dostoyevsky#Charlie Chaplin#Ernst Lubitsch#Aline Belfort#João Fiadeiro#Mariano Llinás#João César Monteiro#I Put a Spell on You#interview#Andreea Pătru

0 notes

Photo

Thursday, January 26, 2017

MimiCof AV show with Kaliber16 @ Sound + Vision program of the Rotterdam Filmfestival.

0 notes

Text

Planet youth

From left to right: Ngọc Nick M, Aswathy Gopalakrishnan, Adham Youssef, Petra Meterc; photo: courtesy of IFF Rotterdam

As every year, International Film Festival Rotterdam invites a bunch of young talents from all over the world to represent the new generation of journalists and critics, and Yoana Pavlova is there to interview them. Only this time Festivalists was officially part of the education process, and be it because of the zeitgeist, or because of the 2017 trainee selection, the conversation revolved around the existing politics of cinema and festivals' Realpolitik, as well as around the audiovisual future of criticism.

In a festival like Rotterdam that grew and grew until it became Planet IFFR, projects that focus on young film critics might look like small asteroids. This makes the contact even more valuable and heartening. Take each one of these trainees, though, and you would discover a whole universe, an accomplished professional with different background, interests, taste.

Ngọc Nick M wrote on the controversial Vietnamese horror KFC. Aswathy Gopalakrishnan interviewed filmmakers like Rahmatou Keïta and Julian Rosefeldt, weighting also on the Hivos Tiger Award winner SEXY DURGA. Adham Youssef talked to the creative duo behind CAIRO JAZZMAN. Petra Meterc reported on the Jan Němec's retrospective launch and met the hope of German cinema Julian Radlmaier.

Still and all, the four have one thing in common – their capacity and drive to capitalize on the IFFR experience.

Yoana Pavlova: My first question is related to your decision to take part in the IFFR Trainee Project for Young Film Critics – were you familiar with the festival before applying, or it was the information about the project that caught your attention in the first place?

Ngọc Nick M: Before Rotterdam, I had participated in Tokyo International Film Festival in Japan three times and some local festivals in my country (Vietnam) as a journalist. This is my first experience at an European film festival. To me, IFFR is one of the most important events in the film industry. Numerous Vietnamese filmmakers wish to submit their features or shorts to Rotterdam. At the end of October last year, I was made aware of the IFFR Trainee Project for Young Film Critics through a new friend who works for IFFR as a programmer. I immediately applied, because it would have been a great opportunity to explore IFFR and improve my writing skills. Furthermore, I will be 30 in October this year, so IFFR Trainee Project for Young Critics 2017 was my last chance for this program.

Aswathy Gopalakrishnan: Yes, I had heard of IFFR before, since the Hivos Tiger Competition section is quite well-known in the filmmaking / film journalism circles in India. A few years ago, THE IMAGE THREADS / CHITRA SUTRAM (2010), a film by the young Indian director Vipin Vijay, had been screened at the festival. The name of the fest is what caught my interest initially.

Adham Youssef: I was familiar with the project IFFR had for young film critics, but I did not know the actual details. I knew from the start that IFFR was a festival with a rather informal mechanism which welcomes young people and talents, especially in the filmmaking area, and gives them the opportunity to experience and learn. This really encouraged me to apply and to be part of this year’s selection.

Petra Meterc: I heard a lot of interesting things about the Rotterdam festival, and this autumn I realized they also organize the IFFR Trainee Project for Young Critics, so it was the combination of wanted to experience both.

YP: To what degree this festival edition, including the Trainee Project, met your expectations?

NNM: I am greatly satisfied with my experience at this year’s IFFR. I watched more than 10 films that would be difficult to find in cineplexes in Vietnam, such as NOCTURAMA (2016), YOURSELF AND YOURS / DANGSINJASINGWA DANGSINUI GEOT (2016), AMERICAN HONEY (2016), and MOONLIGHT (2016). Moreover, director Barry Jenkins’ masterclass and two expert meetings with experienced film critics Jay Weissberg and Clarence Tsui have inspired me tremendously. As an IFFR Trainee, with my three new friends from Slovenia, India, and Egypt I acted as a member of the FIPRESCI jury for the Bright Future section. It was my first time as a jury member, and it was quite a terrific moment debating and picking the winner.

AG: Regarding the trainee project, I had not much idea how the programme would be, when I arrived in Rotterdam. This was my first such experience ever. I was just glad to be a part of it.

This project helped me mitigate the doubts I had as a film critic, at least to a large extent. The discussions and mentor sessions with people like Jay Weissberg were really insightful. The festival had a warm, amiable ambience that would make any cinephile feel at home.

AY: For this edition, I was very satisfied with the film selection, which was very rich and diverse. The programming as well as the ability to capture several themes and merge them into the large scope of the festival’s objective were really fascinating. The same goes for the organization of the festival and the dedication of the staff. Personally, from an artistic and logistical points of view, IFFR is one of the international festivals that really stands out, and which will continue to inspire more people in the field of film.

This year’s Trainee Project had more of a free-for-all agenda, when approaching the interns and their work. The coordinators, fortunately, trusted the trainees to set their own schedules and plan their own interviews. I really liked the approach, compared with the experiences of former trainees whom I met, who mentioned that there was a rather pyramid-like structure when it came to assignments and mentoring, which was accompanied by deadline pressure and stress, something I am glad I did no experience on my first festival abroad. The coordinators also highlighted for us certain events or figures that needed attention, or which they needed to have the spotlight on. I do not mind getting assignments. I think it is part of the experience, to be challenged to go outside of your comfort zone, maybe with topics or artists you are not very aware of. The mentorship sessions, despite several logistical difficulties, were successful, in my opinion. All the trainees this year had previous publishing experiences, but the mentoring sessions were effective in showing how editors usually look and evaluate articles. Also receiving live feedback in a group session is always, for me at least, a good experience, to get challenged and remain critical of your work and hoping for more improvement.

I would have hoped, however, for more coordinated sessions with experts, like for example editors, video essayists, or broadcast show hosts, mainly individuals who would share experiences that do not necessarily have to do with film journalism. Another issue that I would have liked was to coordinate more with the people from the daily printed newsletter. I think to have a review or a report published would have been for the trainees an achievement in the whole experience of the festival.

PM: The festival edition met my expectations regarding the programme and the general atmosphere there, however I did not know what to expect from the Trainee Project. I think the project gave me a lot of valuable experience, especially by meeting experts from the same field of work and, of course, by having the chance to meet other young critics from all over the world and the possibility to discuss film, work, and so much more with them.

YP: What would you change from your festival stay, if you could go back in time?

NNM: I wish we could have met you from the very first day. At the beginning, I was a bit confused about what to do during my stay, so I just went to selected screenings. After our meetings with you, I had a clearer direction of what to achieve throughout the festival.

AG: Maybe I would try to pick films to watch more carefully. This time, I chose films randomly, and later I realized that I missed out a few must-watch films.

But in general, I am happy with what I experienced at the festival. I wish I could go back in time, not to change anything, but just be there and watch many more films.

AY: I would have changed two things. Having a more organized schedule is the first. Being a rookie at a mega festival like Rotterdam that includes dozens of exciting daily screenings and events left me at times confused and being unable to organize. I managed to watch as many films as I could, whether in theatrеs or in the video library, but nevertheless I think I needed more discipline when organizing my festival plan.

Another thing I would have intensified was expanding my networking skills more and more. I think I did enough this year, again for a first-timer. In the future, I guess I need to further develop this skill, which I now know is crucial in this field.

PM: I would probably wish for some additional meetings with various experts who would advise us on our writing, on work opportunities, and work conditions. I would also wish to collaborate a bit more with the IFFR blog team.

YP: Could you please tell me a little bit more about this year's Trainee Project, the way you experienced it, what was the most useful thing you learned?

NNM: IFFR Trainee Project has given me a valuable learning experience on the independent and experimental cinema. As a journalist, I obtained an overview of how the festival is run, from the screenings to the parties and the audience contribution, how to network, how to use the catalogue, and how to distribute my time during the festival. I personally love the atmosphere of IFFR the most. Each screening was full with excited audience, even for those aspiring directors from different corners of the world. I could feel a strong sense of diversity here. As a FIPRESCI jury member, I learned how to judge the competition and improve my debating skills. As a young film critic, I tried to watch and review films I had seen. And you helped enthusiastically with editing my reviews.

AG: I learned that it is important – very, very important – to be honest. It is important to not get carried away by the popular opinions, and express our own views freely and clearly. That kind of courage and honesty will definitely make the review read many times better.

AY: I think I answered the main part of this question above. However, concerning the part of what I learned, I would like to say a couple of things:

The first is that the very vague and problematic term “independent cinema” was deconstructed for me in my experience at this festival. Ultimate freedom to make a film is a type of freedom that artists are not yet granted. As an individual coming from the so called “developing” part of this world, I concluded that filmmakers, even at the very prestigious festivals, are still restricted. Of course, not by censorship or by banning, like what happens in many cases, but by being tempted, for funding purposes, to present narratives that appeal to the other part of the world, the “developed” countries. Narratives that get easily digested in Europe and the US.

But I must say that my argument is still not fully ripe. I am very encouraged to investigate this topic more and more, especially given that it is very critical to individuals and institutions who very much value the idea of “independent art,” and take it for granted, without reading between the lines of its politics and economics. I think I should also start to speak to more filmmakers to understand the aspects of funding, because it is very important.

Second, out of honesty, I have to say that I have outgrown ideas that writing about film is an activity that makes me happy and pleased. My experience in the festival opened my horizons into the “industry” side of the film criticism. Also, it opened my eyes to the politics and agenda that can surround this activity.

Finally, regardless of these last two critical points, I can safely say that despite all of the horrors that we see in this world, cinema remains a tool for human beings to express, question, and challenge, and propagate ideas. This sounds like a cliche, but it has to be said. The amount of talent, passion, and effort I saw in the films I watched, made me further believe in the medium of film.

PM: The Trainee Project enabled us to fully experience the festival; we did some writing for the IFFR blog as well as for our home affiliations, we had a few expert meetings, and joined the FIPRESCI jury with their decision-making on the FIPRESCI award. Probably the most useful thing that I had the chance to experience is how to write a review immediately after attending a film screening. I believe it is a special skill to be prepared to write right after watching a film and to do that as fast as possible.

YP: What was your personal highlight of the festival (film, special event, person)?

NNM: My personal highlight of the festival was the chance to meet Adham, Aswathy, and Petra. It was our first time at IFFR, and we had a great time. I remember the days we woke up at 8 am to catch the tram #7 to De Doelen. After breakfast, we explored IFFR in our own way. Some spent their time in the video library, some joined meetings, and others went for interviews. I would like to say thanks to the IFFR Trainee Project for connecting us. Everything was so fresh, and I cherished every second at IFFR. I will always remember the moment we unanimously selected German film SELF-CRITICISM OF A BOURGEOIS DOG / SELBSTKRITIK EINES BÜRGERLICHEN HUNDES (2017) as our favorite from the Bright Future section, and the debate with the FIPRESCI Award jury. Additionally, the MOONLIGHT screening and Barry Jenkins’ masterclass were also the high points of IFFR.

AG: The meeting with the FIPRESCI jury was a great experience. So were the sessions with Jay Weissberg and Clarence Tsui.

Even more interesting were the discussions and negotiations in which we, the four young trainees, had to choose the one film to vote for. We have different tastes in films, so it was not easy to arrive at a conclusion. We would watch the films, make (long) notes on why we liked / disliked a certain aspect of the film, and put forth our view when the team would meet for a coffee afterwards. I had never had a more meticulous and interesting movie-watching experience.

AY: I cannot say I have a single highlight. However, an event that I really appreciated was getting to see Hungarian film director Béla Tarr, in the flesh. Although I did not get the opportunity to attend his masterclass, I managed to meet him in a very informal and quick manner afterwards, unfortunately without getting to ask questions or even probably introduce myself. Nevertheless, it was mind-blowing to see a living legend, whose work defined different schools of filmmaking.

Other meetings that I really enjoyed, where I got to ask questions and talk about my experience, were those with film critics like Jay Weissberg and Clarence Tsui. I think those meetings were beneficial, as both critics really addressed different aspects of the film criticism business. I am glad they did not limit to discussion of the platonic image of film criticism, being a romantic job, but stressed on many challenges, such as meeting deadlines, being limited to a certain editorial policy, or even pros and cons of attending festivals, etc. Also the fact that both are not just big names in the industry, but also academics who wrote longer film analysis, was really interested to me as my approach to film criticism usually tackles sociopolitical aspects in the film and not just the aesthetics.

PM: Although I liked the Trainee Project and of course the films that we got to see at the festival, I must say that the personal highlight was the three other young critics that were in the project with me. I learned a lot from them and really enjoyed being in their company. One of the most interesting and valuable part of the programme for me was probably the Black Rebels panel – it was amazing !

YP: Now with this Trainee Project in your CV, how do you see your future in the filed of film journalism and criticism? Is there a certain aspect of the profession you feel like you need to master?

NNM: I will continue to develop my journalist and critic's career by writing more articles and reviews, doing more interviews. However, I will try to write more in English in order to reach more readers. Also, I want to promote the IFFR Trainee Project to young Vietnamese who want to work in the field of film journalism and criticism, so they could apply in the coming years. With my new connections from IFFR, I hope to create a network for Vietnamese filmmakers to help introduce their works to international film festivals like Rotterdam.

AG: Now there are vlogs and video essays which are becoming more popular. There are interesting ways to use social media in film criticism. While it is important to not lose sight of the true essence of film criticism, it is also important to update oneself constantly and make our voice be heard.

Nowadays, anyone who has some time to spare and a little flair for writing thinks he can be a film critic. There is a surge in the number of such amateurs. It is important to learn about films more – look at it as an academic discipline. That will make our writings stand out of the pile.

AY: Personally, whenever I attend a film workshop or hangout with a group of film critics, or directors, or individuals from the industry in general, I keep a notebook to write the amount of names of directors, films, movements I do not know of. My experience in Rotterdam left me with dozens of names I need to explore and learn about.

The experience also left me eager to further practice different kinds of criticism, and not to limit myself to a single genre, all under the title of a film critic. However, the type that I would like to further develop my skills in is longer essays that focus more on using films and movements as a tool to deconstruct and understand society and politics.

PM: I think my next step should be trying to publish my writing in foreign or international outlets. I would also like to attend and report from more international festivals and keep on learning while doing that.

#IFF Rotterdam#IFFR2017#Trainee Project for Young Film Critics#FIPRESCI#Hivos Tiger Award#Bright Future#Black Rebels#Planet IFFR#Jay Weissberg#Clarence Tsui#Barry Jenkins#Béla Tarr#Jan Němec#Self-criticism of a Bourgeois Dog#Julian Radlmaier#festival life#Ngọc Nick M#Aswathy Gopalakrishnan#Adham Youssef#Petra Meterc#interview#Yoana Pavlova

0 notes

Photo

The International Film Festival Rotterdam @iffr has started again. Looking forward to seeing 'Le serpent aux mille coupures' tomorrow and 'Paterson' from Jim Jarmusch with Adam Driver later. And planning to see more. #PlanetIFFR #IFFR #IFFR2017 #fruitdoodle (bij Rotterdam, Netherlands)

0 notes