#Jenny Odell

Text

“Most living entities and systems on this planet obviously do not live by the Western human clock (though some, like the crows who memorize a city's daily garbage truck route, do of course adapt to the timing of human activities). To watch a brown creeper as it inches up and down, peering into crevices and extracting bugs with its little dentist beak, is thus a way of catching a ride out of the grid and toward a time sense so different that it is barely imaginable to us. In Jennifer Ackerman's book The Bird Way, I learned that the male black manakin, a South American songbird, can do somersaults so fast that a human can see them only in slowed-down video. Some birdsong contains notes that are sung too quickly or are too high-pitched for us to hear. Veeries, a species related to the American robin, can predict hurricanes months in advance and adjust their migration route accordingly, and no one currently knows how. Birds own bodies and their movements are an entanglement of time and space: If a loon is in the higher latitudes, it's summer, and the bird is mostly black with a striking pattern of white stripes. If the same loon is near my studio in Oakland, it's winter, and the bird is almost unrecognizably different, a dull grayish brown.”

Jenny Odell, Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock (emphasis mine)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

4/13/2024

Hung out at a local Serbian cafe and the coffee and food were delightful.

I’m chipping away bit by bit at residency onboarding requirements.

I’m currently reading How To Do Nothing by Jenny Odell which is excellent, so far I really recommend it!

#emgoesmed#studyblr#studyspo#med student#med school#med studyblr#productivity#coffee#weekend#books#reading#how to do nothing#jenny odell#I have so much on my to do list#but taking a break#to read and drink some good coffee#is very important

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poor people pay higher time tax

Doubtless you’ve heard that “we all get the same 24 hours in the day.” Of course it’s not true: rich people and poor people experience very different demands on their time. The richer you are, the more your time is your own — not only are many systems arranged with your convenience in mind, but you also command the social power to do something about systems that abuse your time.

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/10/my-time/#like-water-down-the-drain

For example: if you live in most American cities, public transit is slow, infrequent and overcrowded. Without a car, you lose hours every day to a commute spent standing on a lurching bus. And while a private car can substantially shorted that commute, people who can afford taxis or Ubers get even more time every day.

There’s a thick anthropological literature on the ways that cash-poverty translates into #TimePoverty. In David Graeber’s must-read essay “The Utopia of Rules,” he nails the way that capitalist societies generate Soviet-style bureaucracies, especially for poor people. Means-testing for benefits means that poor people spend endless hours filling in forms, waiting on hold, and lining up to see caseworkers to prove that they are among the “deserving poor” — not “mooches” who are defrauding the system:

https://memex.craphound.com/2015/02/02/david-graebers-the-utopia-of-rules-on-technology-stupidity-and-the-secret-joys-of-bureaucracy/

The social privilege gradient is also a time gradient: if you can afford a plane ticket, you can travel quickly across the country rather than losing days to the Greyhound or a road-trip. But if you’re even richer, you can pay for TSA Precheck and cut your airport security time from an hour to minutes. Go further up the privilege gradient and you’ll acquire airline status, shaving another hour off the check-in process.

This qualitative account of time poverty is well-developed, but it’s lacked a good, detailed quantitative counterpart, and our society often discounts qualitative work as mere anecdote and insists on having every story converted to numbers before it is taken seriously.

In “Examining inequality in the time cost of waiting,” published this month in Nature Human Behavior, public affairs researchers Steve Holt (SUNY) and Katie Vinopal (Ohio State) analyze data from the American Time Use Survey (AUTS) to produce a detailed, vibrant quantitative backstop to the qualitative narrative about time poverty:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-023-01524-w

(The paper is paywalled, but the authors made a mostly final preprint available)

https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/jbk3x/download

The AUTS “collects retrospective time diary data from a nationally representative subsample drawn from respondents to the Census Bureau’s Community Population Survey (CPS) each year.” These time-diary entries are sliced up in 15-minute chunks.

Here’s what they found: first, there are categories of basic services where high-income people avoid waiting altogether, and where low-income people experience substantial waits. A person from a low-income household “an hour more waiting for the same set of services than people from high-income household.” That’s 73 hours/year.

Some of that gap (5%) is attributable to proximity. Richer people don’t have to go as far to access the same services as poorer people. Travel itself accounts for 2% more — poorer people wait longer for buses and have otherwise worse travel options.

A larger determinant of the gap (25%) is working flexibility. Poor people work jobs where they have less freedom to take time off to receive services, so they are forced to take appointments during peak hours.

Specific categories show more stark difference. If a poor person and a wealthy person go to the doctor’s on the same day, the poor person waits 46.28m to receive care, while the wealthy person waits 28.75m. The underlying dynamic here isn’t hard to understand. Medical practices that serve rich people have more staff.

The same dynamic plays out in grocery stores: poor people wait an average of 24m waiting every time they go shopping. For rich people, it’s 15m. Poor people don’t just wait in longer lines — they also have to wait for understaffed stores to unlock the cases that basic necessities are locked behind (poor people also travel longer to get to the grocery store — and they travel by slower means).

A member of a poor household with a chronic condition that requires two clinic visits per month loses an additional five hours/year to waiting rooms when compared to a wealthy person. As the authors point out, this also translates to delayed care, missed appointments, and exacerbated health conditions. Time poverty leads to health poverty.

All of this is worse for people of color: “Low-income White and Black Americans are both more likely to wait when seeking services than their wealthier same-race peer” but “wealthier White people face an average wait time of 28 minutes while wealthier Black people face a 54 minute average wait time…wealthier Black people do not receive the same time-saving attention from service providers that wealthier non-Black people receive” (there’s a smaller gap for Latino people, and no observed gap for Asian Americans.)

The gender gap is more complicated: “Low-income women are 3 percentage points more likely than low-income men and high-income women are 6 percentage points more likely than high-income men to use common services” — it gets even worse for low-income mothers, who take on the time-burdens associated with their kids’ need to access services.

Surprisingly, men actually end up waiting longer than women to access services: “low-income men spend about 6 more minutes than low-income women waiting for service…high-income men spend about 12 more minutes waiting for services than high-income women.”

Given the important role that scheduling flexibility plays in the time gap, the authors propose that interventions like subsidized day-care and afterschool programming could help parents access services at off-peak hours. They also echo Graeber’s call for reduced paperwork burdens for receiving benefits and accessing public services.

They recommend changes to labor law to protect the right of low-waged workers to receive services during off-peak hours, in the manner of their high-earning peers (they reference research that shows that this also improves worker productivity and is thus a benefit to employers as well as workers).

Finally, they come to the obvious point: making people less cash-poor will alleviate their time-poverty. Higher minimum wages, larger earned income tax credits, investments in low-income neighborhoods and better public transit will all give poor people more time and more money with which to command better services.

This week (Feb 13–17), I’ll be in Australia, touring my book Chokepoint Capitalism with my co-author, Rebecca Giblin. We’re doing a remote event for NZ on Feb 13. Next are Melbourne (Feb 14), Sydney (Feb 15) and Canberra (Feb 16/17). More tickets just released for Sydney!

[Image ID: A waiting room, draped with cobwebs. A skeleton sits in one of the chairs. A digital display board reads 'Now serving 53332.' An ogrish, top-hatted figure standing at a podium, yanking a dollar-sign shaped lever looms into the frame from the right. He holds a clock aloft disdainfully, pinched between the thumb and fingers of one white-gloved hand.]

#pluralistic#scholarship#auts#american time use survey#time use#jenny odell#race#graeber#david graeber#how to do nothing#utopia of rules#inequality#gender#time poverty

797 notes

·

View notes

Quote

But beyond self-care and the ability to (really) listen, the practice of doing nothing has something broader to offer us: an antidote to the rhetoric of growth. In the context of health and ecology, things that grow unchecked are often considered parasitic or cancerous. Yet we inhabit a culture that privileges novelty and growth over the cyclical and the regenerative. Our very idea of productivity is premised on the idea of producing something new, whereas we do not tend to see maintenance and care as productive in the same way.

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy

1K notes

·

View notes

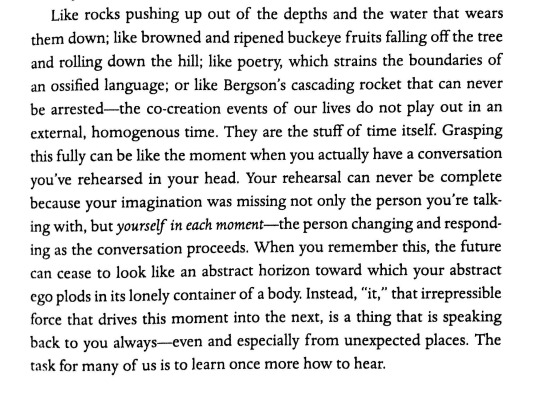

Text

Jenny Odell, from Saving Time

204 notes

·

View notes

Photo

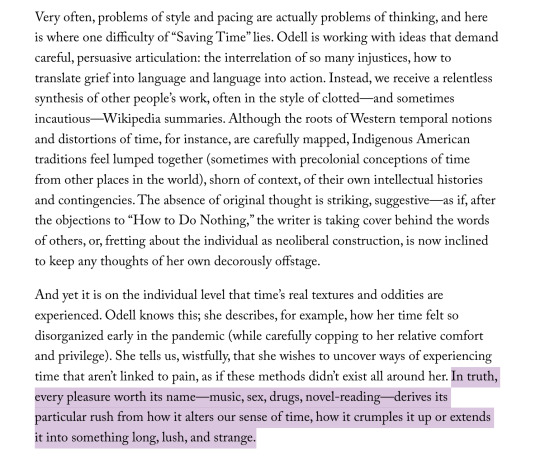

god, Parul’s review of the newest Jenny Odell is so good (even though I wanted the Odell to be so good) (x)

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Interestingly, my experience suggests that while it initially takes effort to notice something new, over time a change happens that is irreversible. Redwoods, oaks, and blackberry shrubs will never simply be “a bunch of green.” A towhee will never simply be “a bird” to me again, even if I wanted it to be. And it follows that this place can no longer be any place.”

how to do nothing // jenny odell

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

"[A]s the experience economy expands to include commodified notions of things like slowness, community, authenticity, and 'nature' -- all while income inequality yawns wider and the signs of climate change intensify -- I feel the panic of watching possible exits blocked. I keep wanting to do something instead of consume the experience of it. But seeking new ways of being, I find only new ways of spending."

-Jenny Odell-

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

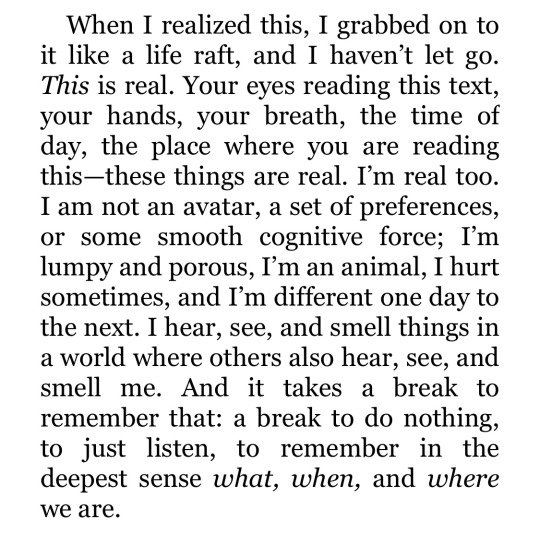

Jenny Odell, How to do nothing

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Just because a language is imposed, it doesn't mean it can be controlled; and just because it's spoken, it doesn't mean it's been internalized. Although Native reservations in the United States were overseen by white agents well into the twentieth century, with traditional dancing typically restricted, the Lakota figured out in the 1920s that they could hold extensive dances on the Fourth of July if they did it under the banner of patriotism. When this tactic worked, it spread throughout the northern and southern plains, with petitions for dances on New Year's Day, Washington's and Lincoln's birthdays, Memorial Day, Flag Day, and Veterans Day. In his book Indian Blues, John Troutman quotes Severt Young Bear: ‘The agents thought those weren't dangerous occasions, so we got to dance.’ These supposedly nationalist celebrations appeared dangerous, Troutman writes, only ‘when [agents] realized that they could not contain the symbolism of the holiday that they wished the Lakotas to observe.’

… “It has the element of an inside joke, meaningful only to the Lakota and not to those less-savvy agents who flattered themselves with the incredible idea that Indians would want to celebrate the Fourth of July. Under the temporal and spatial surveillance of Indian agents, the Lakota were able to find an interstitial hiding space within the vicissitudes of language.”

Jenny Odell, Saving Time

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I enjoyed this conversation, both in terms of its perspective on the internal drive to achieve more faster (that it pays to focus on experiencing great things instead of crossing a maximum number of items from the to-do list) as well as its perspective on climate dread and generally feeling like you're standing on the precipice of a catastrophe.

They discuss how it's actually not possible to know what comes next because we don't know yet how our own actions as well as those of others will shape the future. Yes, it's important to acknowledge and accept and grieve, but also to answer the question "and now what?"

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I WANT TO be clear that I’m not actually encouraging anyone to stop doing things completely. In fact, I think that “doing nothing”—in the sense of refusing productivity and stopping to listen—entails an active process of listening that seeks out the effects of racial, environmental, and economic injustice and brings about real change. I consider “doing nothing” both as a kind of deprogramming device and as sustenance for those feeling too disassembled to act meaningfully. On this level, the practice of doing nothing has several tools to offer us when it comes to resisting the attention economy.

The first tool has to do with repair. In such times as these, having recourse to periods of and spaces for “doing nothing” is of utmost importance, because without them we have no way to think, reflect, heal, and sustain ourselves—individually or collectively. There is a kind of nothing that’s necessary for, at the end of the day, doing something. When overstimulation has become a fact of life, I suggest that we reimagine #FOMO as #NOMO, the necessity of missing out, or if that bothers you, #NOSMO, the necessity of sometimes missing out.

That’s a strategic function of nothing, and in that sense, you could file what I’ve said so far under the heading of self-care. But if you do, make it “self-care” in the activist sense that Audre Lorde meant it in the 1980s, when she said that “[c]aring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

Jenny Odell. How to Do Nothing

50 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Consider two things in tandem. First, people in wealthier neighbourhoods almost always have more access to urban parks and to parkland, on top of the face that such neighbourhoods are often in the hills or by the water. [...]

Second, consider that while seemingly every kid in a restaurant is now watching bizarre, algorithmically determined children's content on YouTube, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs both severely limited their children's use of technology at home. As Paul Lewis reported for The Guardian, Justin Rosenstein, the Facebook engineer who created the "like" button, had a parental-control feature set up on his phone by an assistant, to keep him from downloading apps. Loren Brichter, the engineer who invested the "pull-to-refresh" feature of Twitter feeds, regards his invention with penitence: "Pull-to-refresh is addictive. Twitter is addictive. These are not good things. When I was working on them, it was not something I was mature enough to think about." [...]

In their own ways, both of these things suggest to me the frightening potential of something like gated communities of attention: privileged spaces where some (but not others) can enjoy the fruits of contemplation and the diversification of attention. One of the main points I've tried to make in this book - about how thought and dialogue rely on physical time and space - means that the politics of technology are stubbornly entangled with the politics of public space and of the environment. This knot will only come loose if we start thinking not only about the effects of the attention economy, but also about the ways in which these effects play out across other fields of inequality.

By the same token, there are many different places where manifest dismantling can begin to work. Wherever we are, and what ever privileges we may or may not enjoy, there is probably some thread we can afford to be pulling on. Sometimes boycotting the attention economy by withholding attention is the only action we can afford to take. Other times, we can actively look for ways to impact things like the addictive design of technology, but also environmental politics, labour rights, women's rights, indigenous rights, anti-racism initiatives, measures for parks and open spaces, and habitat restoration - understanding that pain comes not from one part of the body but from systemic imbalance. As in any ecology, the fruits of our efforts within any of these fields may well reach beyond to the others.

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

["... I am less interested in a mass exodus from Facebook and Twitter than I am in a mass movement of attention: what happens when people regain control over their attention and begin to direct it together, again.

Occupying the "third space" within the attention economy is important not just because, as I've argued, individual attention forms the basis for collective attention and this for meaningful refusal of all kinds. It is also important because in a time of shrinking margins, when not only students but everyone else has "put the pedal to the metal", and cannot afford other kinds of refusal, attention may be the last resource we have left to withdraw. In a cycle where both financially driven platforms and overall precarity close down the space of attention-the very attention needed to resist onslaught, which then pushes further- it may be only in space of our own minds that some of us can begin to pull apart the links."]

How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, Jenny Odell

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hungry. That was the word that hooked me. That’s how my brain felt to me, too. Hungry. Needy. Itchy.

So when I came across Nicholas Carr’s book in 2020 (The Shallows: What Internet is Doing to Our Brains), I was ready to read it. And what I found in it was a key — not just to a theory but to a whole map of 20th-century media theorists...who saw what was coming and tried to warn us. Carr’s argument began with an observation, one that felt familiar:

The very way my brain worked seemed to be changing. It was then that I began worrying about my inability to pay attention to one thing for more than a couple of minutes. At first I’d figured that the problem was a symptom of middle-age mind rot. But my brain, I realized, wasn’t just drifting. It was hungry. It was demanding to be fed the way the Net fed it — and the more it was fed, the hungrier it became. Even when I was away from my computer, I yearned to check email, click links, do some Googling. I wanted to be connected.

Hungry. That was the word that hooked me. That’s how my brain felt to me, too. Hungry. Needy. Itchy. Once it wanted information. But then it was distraction. And then, with social media, validation. A drumbeat of: You exist. You are seen...

These are industries I know well, and I do not think it has changed them, or the people in them (myself included), for the better.

But what would? I’ve found myself going back to a wise, indescribable book that Jenny Odell, a visual artist, published in 2019. In “How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy,” Odell suggests that any theory of media must first start with a theory of attention. “One thing I have learned about attention is that certain forms of it are contagious,” she writes.

When you spend enough time with someone who pays close attention to something (if you were hanging out with me, it would be birds), you inevitably start to pay attention to some of the same things. I’ve also learned that patterns of attention — what we choose to notice and what we do not — are how we render reality for ourselves, and thus have a direct bearing on what we feel is possible at any given time. These aspects, taken together, suggest to me the revolutionary potential of taking back our attention.

I think Odell frames both the question and the stakes correctly. Attention is contagious. What forms of it, as individuals and as a society, do we want to cultivate? What kinds of mediums would that cultivation require?

This is anything but an argument against technology, were such a thing even coherent. It’s an argument for taking technology as seriously as it deserves to be taken, for recognizing, as McLuhan’s friend and colleague John M. Culkin put it, “we shape our tools, and thereafter, they shape us.”

There is an optimism in that, a reminder of our own agency. And there are questions posed, ones we should spend much more time and energy trying to answer: How do we want to be shaped? Who do we want to become?

— Ezra Klein, from “I Didn’t Want It to Be True, but the Medium Really Is the Message” (NY Times, August 7, 2022)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I think I know everything that I want and like, and I also think I know where and how I'll find it-imagining all of this stretching endlessly into the future without any threats to my identity or the bounds of what I call my self-I would argue that I no longer have a reason to keep living

- Jenny Odell - How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy

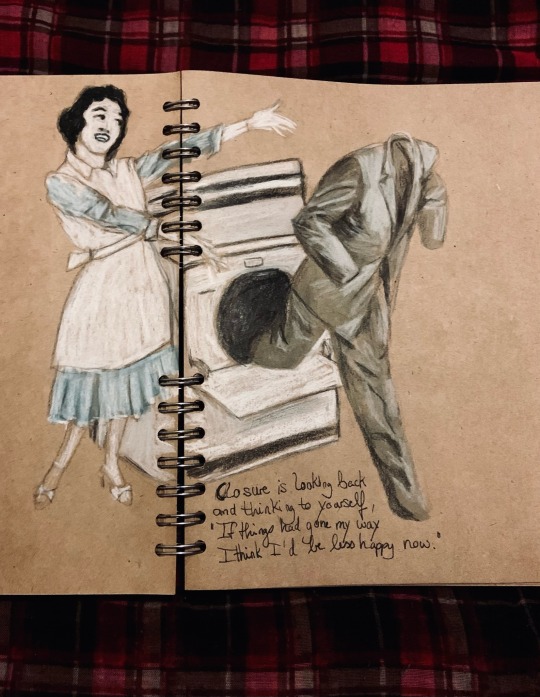

#artists on tumblr#artist's studio#drawing#sketchoftheday#illustration#sketchbook#watercolor#jenny odell#art quotes

4 notes

·

View notes