#KIWIKIU

Text

i think of this image approximately every day of my life

Magellanic Penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) observation by kiwikiu

#inaturalist#naturalist#nature#ecology#zoology#biology#wildlife#birds#bird#birdblr#birding#orinthology#birdwatching#penguin#penguins#i cant believe this is one of masons obs and i didnt realize until now i think of this image CONSTANTLY#like every time i use the thumbs up emoji. which is a lot#thank you mason

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't get me started on how my view has been ruined since all these resorts came along. I try to leave some "presents" on Bezos' yacht whenever I can.

Maui Parrotbill (Pseudonestor xanthophrys) AKA kiwikiu

Maui, Hawai'i

Status: Critically Endangered

---

I love his grumpy face.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Apapane (Himatione sanguinea)

The bright crimson ‘Apapane is part of a group of native Hawaiian birds, reminiscent of – but even more diverse than – the famed Galápagos finches. Known as the Hawaiian honeycreepers, these birds evolved into a varied group of dozens of species that originated from a few wayward ancestors. ‘Apapane feathers, along with those of other native birds, were prized by Native Hawaiians, who used them to adorn the capes, helmets, and feather leis of Hawaiian nobility. The bird's scientific name refers to a “blood-colored cloak.”

There were once more than 50 honeycreeper species found only in the Hawaiian Islands, but today just 17 remain, including the ‘I‘iwi and Kiwikiu, or Maui Parrotbill. The ‘Apapane is the most plentiful.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata) by kiwikiu on iNaturalist

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breaking Ice, and Helicopter Drops: Winning Photos of Working Scientists

Nature’s Annual Photography Competition Attracted Stunning Images From Around the World, Including Two Very Different Shots Featuring the Polarstern Research Vessel.

— By Jack Leeming | 23 April 2024

Glaciologist Richard Jones captured the moment a crew member on RV Polarstern prepared to rescue a measuring device trapped in ice.

Nature’s Annual Photography Competition Showcases Stunning Images From Around the World. By Jack Leeming. This image, taken on top of the ice breaker research vessel Polarstern, shows the delicate process of retriev ing an instrument called a CTD (short for conductivity, temperature, depth) that had become trapped under sea ice off the coast of northeastern Greenland. CTDs, which are anchored to the sea floor, measure how ocean properties such as salin ity and temperature vary with depth. At some point, the sea ice had closed over the top of this one, forcing the Polarstern to skirt carefully around the equipment, breaking the ice to rescue it from the freezing ocean.

“You’re crashing into ice and breaking through it. So it wasn’t particularly calm sail ing for the majority of the trip,” remembers Richard Jones, who took the image in Septem ber 2017 and is the winner of Nature’s 2024 Working Scientist photography competition. His research aims to improve estimates of the rate at which ice is being lost from the world’s glacial ice sheets. Jones, a glaciologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, highlights the photo graphic contrast between icebreaker and ice that he’d become used to in his five weeks aboard the Polarstern. “All you really see is

blue and white. And sometimes that might feel pretty monotonous, but the colours from the CTD instrument and the orange of the crane contrast the scene and also complement it quite nicely.” We received more than 200 entries this year from researchers working around the world. The winner and the four runnersup (highlighted on the following pages) were selected by a jury of Nature staff, including three of the journal’s picture editors. All will receive a prize of £500 (US$620), in the form of Amazon vouchers or a donation to charity, as well as a year’s subscription to Nature.

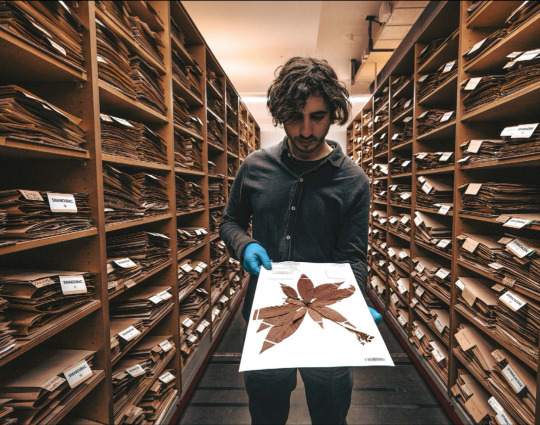

Work/Careers! Library Ofleaves! PhD student Kim Castro took this photo of her colleague, postdoctoral researcher Luiz Leonardo Saldanha, in a herbarium that they both work in regularly. It's shared between the University of Zurich and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich. Both Castro and Saldanha investigate the medicinal plants of the Amazon at the Department of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany at the University of Zurich, although the two have very different approaches: whereas Saldanha investigates their chemical diversity, Castro looks at how the plants are perceived by Indigenous communities in the Amazon, specializing in how the plants smell. A herbarium, Saldanha says, is "like a library - but instead of books, there are plants here". Saldanha posed with this particular sample (Palicourea corymbifera, collected in 1977) because it comes from his home country, Brazil, but is used by the Indigenous Desano people in Colombia as a medicinal herb. "So it creates a commonality between South American countries," he says.

“Only 130 of These Birds 🦅 Remain On Earth. A Single Mosquito Bite Can Kill a Kiwikiu." Reaching the beak Conservation biologist Ryan Wagner snapped this photo of field biologist Sonia Vallocchia feeding a recently caught kiwikiu (Pseudonestor xanthophrys), in January this year. It was taken on Haleakala volcano on the Hawaiian island of Maui. Wagner, a PhD student at Washington State University Vancouver, was on an expedition to the island as a science communicator, hoping to raise awareness of the plight of the endangered birds. "Only 130 of these birds remain on Earth," explains Wagner. "Their numbers have crashed due to avian malaria, which is spread by invasive mosquitoes. As climate change warms the island, mosquitoes have advanced upslope into the high-elevation refuges where native birds survive. A single mosquito bite can kill a kiwikiu." He hopes that ornithologists such as Vallocchia, who works for the Maui Forest Birds Recovery Project in Makawao, will help to save these birds by bringing some of them (by helicopter) to the Maui Bird Conservation Center, also in Makawao. There, they will be treated for malaria and join a captive breeding programme, he says.

Mountain Drop-off! In this dramatic image, taken from below the still-spinning, deafening blades of a military helicopter, scientists shelter with their equipment after being dropped off at the top of a remote mountain in northern Amazonia. They are taking part in a biodiversity-research expedition to Serra Imeri, an isolated mountain range that rises through the forest canopy near the border of Brazil and Venezuela, in November 2022. "A total of 14 scientists and dozens of military support personnel took part in the expedition, which lasted for 11 days and resulted in the discovery of several new species of amphibians, reptiles, birds and plants," says photographer Herton Escobar, a science journalist who works with the scientists pictured, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil.

Go With The Floe! Emiliano Cimoli, a remote-sensing scientist at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania, Australia, took the second photograph featuring the research vessel Polarstern in this year's collection of winning images. Here, Carolin Mehlmann and Thomas Richter, mathematicians at the University of Magdeburg, Germany, are measuring the depth of snow across a giant ice floe drifting in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. The image was taken during a two-month voyage organized by the Alfred Wegener Institute, based in Bremerhaven, Germany, in August 2023. The goal of the expedition was to evaluate interactions between the ice physics, biology, hydrography, biogeochemistry and biodiversity of the Arctic ecosystem, from the sea ice to the sea floor.

#Nature.Com#Nature’s Annual | Photography | Competition#Stunning Images | Around the World 🌎#Polarstern Research Vessel 🚢#Winning Photos#Working Scientists

0 notes

Text

Sign in

In 1886, after meeting the inventor Thomas Edison in New York, Hawaii’s King Kalakaua enthusiastically began electrifying the grounds of his new residence — and within a year, 325 incandescent lights had the Iolani Palace fully aglow.

The king wouldn’t be able to pull off the same feat these days on Maui. Much of the island’s outdoor illumination soon could violate a new ordinance intended to help the island’s winged population. Fines could reach $1,000 a day.

The measure restricts outdoor lighting in an effort to keep endangered birds — and Maui has some of the world’s rarest — from crashing into spotlighted buildings. But Bill 21, signed into law last week, is ruffling feathers because its provisions also could keep flagpoles, church steeples, swimming pools and even luaus in the dark.

“People have told me they’ve seen birds falling on the ground in town, up country, all over the place,” said the bill’s author, Kelly Takaya King, who chairs the Maui County Council’s Climate Action, Resilience and Environment Committee.

Maui is a veritable Eden for species such as the wedge-tailed shearwater, white-tailed tropicbird, brown booby, myna, kiwikiu and nene — the state bird and the world’s rarest goose.

The island also is home to some 170,000 people, however, and the new law is pitting the avian paradise against the human one. The ordinance imposes a near-total ban on upward-shining outdoor lighting and limits short-wavelength blue-light content. Similar laws are in effect in many jurisdictions nationwide to protect various local interests, including the night skies in Arizona and the wilderness in New Hampshire. Maui has a more complicated set of priorities.

The outdoor light restrictions effectively prohibit nighttime hula dances and luau performances — local cultural signatures. Indoor alternatives are impractical. “Customers do not want to be in a ballroom or enclosed facility — they can go to Detroit and do that,” wrote Debbie Weil-Manuma, the president of a local tourism company, in a letter of opposition.

At the same time, Maui is grappling with an invasive species arriving in flocks of up to 35,000 a day: tourists. Local officials are considering caps on hotel and vacation rentals.

Birds can be disoriented by artificial light, sometimes confusing it for moonlight, and end up slamming into a building’s windows or circling until exhausted. In a single night in May 2017, 398 migrating birds — including warblers, grosbeaks and ovenbirds — flew into the floodlights of an office tower in Galveston, Tex. Only three survived. This danger is why the Empire State Building in New York City, the former John Hancock Center in Chicago and other landmark skyscrapers now go dark overnight during peak bird migration periods.

One tall building. One dark and stormy night. 395 dead birds.

Yet, most mass bird fatalities occur in urban centers with tall buildings in high density. Maui is rural, and its kalana, or county office building, is only nine stories tall.

Jack Curran, a New Jersey lighting consultant who evaluated the science behind the bill, said the council “clearly didn’t do their homework.” The bill also requires that lighted surfaces be nonreflective, with a matte surface if painted. As the island is coated in compliant black paint, Curran joked, “Maui will wind up looking like Halloween.”

Even support for the regulation is fractured. “This bill does provide good benefits,” said Jordan Molina, Maui’s public works director, “but it doesn’t have to do so recklessly.” The new law, he added, will make his office the “blue-light police.”

Although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service did not oppose the bill, it recommended creating a habitat conservation plan unless the county could devise a foolproof lighting policy.

According to public records, the council relied on a single, non-peer-reviewed study funded by an Arizona company, C&W Energy Solutions, that lobbied for the bill. (The county’s attorneys issued a memorandum in July warning of the “potentially serious conflict of interest,” which the council ignored.

) And King’s efforts were propelled in part by conservation groups’ lawsuit alleging that a luxury resort’s lights disoriented at least 15 endangered petrels between 2008 and 2021, resulting in at least one petrel’s death. (By contrast, the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project has focused on the continuing “depredation by feral cats,” which number in the thousands on the island.)

Still at issue are the measure’s conflicting exemptions. For example, lights at public golf courses, tennis courts and schools’ athletics events are allowed, but not lights at hotel-owned golf courses or tennis courts. Conventional string lights are permitted for holidays and cultural festivals but must be “fully shielded” for all other uses, including weddings. The county fair is also exempt. So are emergency services and emergency road repairs.

The law will inhibit TV and film crews’ night lights, such as those used by “Hawaii Five-O,” “NCIS: Hawai‘i” and “The White Lotus.” The latter was honored in October by the Maui County Film Office for giving the island national and international recognition.

To guard migratory birds, Philadelphia plans to cut its artificial lighting that can fatally distract flocks

King told local media that compliant lights are widely available online. But when asked recently for online links to such bulbs, her office sent just one — for a bedside night light that can double as an outdoor bug light, although it was unclear whether the bulb meets all of the ordinance’s specifications.

“Appropriate lighting is not available,” King then conceded. “We’re hoping it will be in the next few years. When you pass a lot of these environmental laws, you kind of have to go in steps to get them passed.”

As passed, the bill explicitly removed exemptions for field harvesting, security lighting at beaches run by hotels or condominiums, safety lighting for water features, motion-sensor lighting, and lighting on state or federal property — including Maui’s harbors and even the runway lights at its airports.

Council member Shane Sinenci supported the ultimate provisions. “Our unique biodiversity is what makes us appealing to both visitors and to residents alike,” the Maui News quoted him as saying before the final vote. “We are often underestimating the value of a healthy ecosystem and all the benefits that comes with it.”

The law takes effect in July for new lighting and requires existing lighting to be in compliance by 2026.

Sign up for the latest news about climate change, energy and the environment, delivered every Thursday

source

0 notes

Text

Kiwikiu (Maui Parrotbill)

This honeycreeper has a uniquely shaped beak that allows it to remove bark and break open fruits to access insects living in the vegetation.

#Hawai'i#birds#hawai'ian birds#animals#wildlife#nature#ecology#habitat conservation#wildlife conservation

79 notes

·

View notes

Link

Colleen Uechi for The Maui News:

The "remarkable" discovery of a rare Maui bird thought to have died 605 days ago has injected new life into the efforts to keep the species from extinction and validated years of forest restoration work.

A lone male kiwikiu, one of 14 released into the Nakula Natural Area Reserve in October 2019, was heard Wednesday by keen-eared conservationists who'd traveled up the leeward slopes of Haleakala to plant 700 native trees.

…

Two years ago, conservationists released a group of captive and wild kiwikiu, or Maui parrotbill, to reforested state land above the 5,000-foot-elevation level of leeward Haleakala in hopes that they would breed and expand across their new home. Nearly all of them fell victim to avian malaria, and the ones who couldn't be found were assumed to be dead.

…

[Hanna] Mounce said the best population estimate for the kiwikiu was 157 in 2019, and assuming they've declined since then, there's likely fewer than 150 left in the wild.

"sup" -- that bird

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maui Forest Birds Critically Threatened

Maui Forest Birds Critically Threatened

The kiwikiu, or Maui parrotbill, is only found in East Maui. There are less than 312 remaining in the wild

A new interagency monitoring report on Hawaiian forest birds indicates that remaining populations of at least two native endemic species of Maui forest birds are in rapid decline.

The surveys conducted in the report were the largest and most comprehensive interagency effort to research East…

View On WordPress

#akohekohe#crested honeycreeper#Haleakala National Park#Hanna L. Mounce#Hawaii Department of Forestry and Wildlife#Hawaii Department of Land Natural Resources Plant Extinction Prevention Program#Kahikinui Forest Reserve#KIWIKIU#Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project#Maui forest birds#Maui parrotbill#Nakula Forest Reserve#Natalie Gates#National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Pacific Island Network#Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit#Seth Judge#State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife#United States Geological Survey#University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo#USGS#weeklynews

0 notes

Text

submission from @telepathic–heart

Hey, check out these cool endemic birds from Haleakala Forest Reserve, Maui, Hawaii!

Kiwikiu

Kiwikiu live up to 16 years, and produce offspring every one or two years on average. They form monogamous pairs and defend a territory up to 20 acres. There are only about 500 known birds left in the world.

‘Apapane

‘Apapane are most well known for their songs, which can be pretty and methodical or harsh and mechanical-sounding. In most cases, the male who is the most aggressive and sings the loudest is the one who gets the female’s attention. About 1,080,000 of these birds exist in Hawaii’s protected mountain forests.

I'iwi

I'iwi have deeply curved bills to collect nectar from flowers, and have a haunting call which has been described as “A child playing a rusty harmonica in the woods.” They’ve experienced the greatest decline in population of any Hawaiian honeycreeper. There are about 350,000 of these birds left.

‘Akohekohe

'Akohekohe are often characterized by their white crest on their foreheads, and their volcanic pallet. They live only in a 50 square kilometer space on Haleakala volcano, and they have a population of about 3700.

Po'ouli

Po'ouli are the rarest birds in the world, and as of 2004 there were only two in existence. Their behaviors are largely undocumented due to their rarity. These birds haven’t been seen since the study in 2004, and are possibly extinct.

#avianpostgenerator#submission#this is incredibly well researched n cool to read#id feel bad if i did not give more credit#birds

72 notes

·

View notes

Link

09/30/19-KIWIKIU TRANSLOCATION HOLDS PROMISE FOR ONE OF THE WORLD’S RAREST BIRDS #HawaiiFishing https://ifi.sh/qxa

0 notes

Text

New Day. New Year.

For years now I have somehow managed to escape the holiday madness by hiding on the residue of a volcanic hiccup in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The days here, like those back home, pass differently, though predictably.

The sun rises to the cool morning trills of Amakihi and Kiwikiu birds, surely nature’s perfect alarm clock. As morning warms to afternoon, the whirl of the globe sends the Pacific waves crashing along the shore. Bodies lie strewn across the glittering sand, toasting brown, then browner, under the island sun. Occasional clouds provide a welcome shower and shadowy respite from the blaze, soon followed by the end of day marked by everyone’s rush seaside.

Sunset in Hawaii.

Despite the moniker, those drawn to the water’s edge invariably witness not the sun going down, but the islands turning their back on it’s tangerine glow. Tick by tick, we watch quietly as the minutes pass effortlessly from our grasp — no clutch strong enough to hold them. The fireball disappears before our very eyes, leaving in its wake only amber and lavender clouds.

Another day gone, we turn our thoughts to what lies ahead for the next. The plans we’ve made. The thing’s we’ve yet to accomplish. Tomorrow I will do what I did not do today — pay bills, go to the grocery store, and finally mail that (now belated) birthday gift that has sat on my entryway table for two weeks. We make our promises. We set our resolve.

The earth’s yearly passage around the orange orb is not quite so stark as its daily revolution, but it evokes much of the same. Promises of a better us in the days and weeks to come. Better eating habits, better exercise plan, finishing some long-awaited project or finding a new job. In addition, coming full circle around the sun often tempts us to resurrect all that has transpired in the last twelve months — some of it glorious, some of it less so. We have experienced both boundless joy and seemingly insurmountable challenges. Yet we have all made it to here. Together.

And now?

Now we press onward as before, knowing that nothing behind us can ever be changed, and nothing before us is ever certain. We will resolve to do better, for ourselves and for each other. And we will keep our promises, in whole or in part. But the coming year needs no more than our pledge to welcome each dawn as another chance to become our truest and best selves. Each pass of the sun across our landscape, wherever we are, gives us the chance to bring life in close — nurturing and tending our garden of family and friends as never before. Each new day gifts us as well with another chance to make our voices heard across our collective communities, from our school boards to Pennsylvania Avenue. We can, by our efforts together, bring about the change we want to see in ourselves, and in the world.

So as we resolve to cut back on our carbs and get to the gym more often, let us also resolve, together, to #Resist #Persist and #StayInvolved.

Welcome, New Year.

We’re ready.

0 notes

Photo

Kiwikiu Birdbeast by Ciameth

I love Hawaiian birds, so I doodled a Kiwikiu, aka Maui Parrotbill (Pseudonestor xanthophrys) for DailyBirdBeast's invitation for guest birdbeasts.

http://dailybirdbeast.tumblr.com/

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project plans to save our rare birds

How Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project plans to save our rare birds

Dr. Hanna Mounce has a lot riding on her shoulders. As the Coordinator for Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project (MFBRP), she’s in charge of the strategy of how to save Maui’s remaining six forest birds.

“I love working in Hawaii because we can really make an on the ground difference for these species one at a time,” says Mounce. “Hawaii species are faced with so many challenges and not nearly the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

04/10/19-NEW RELOCATION PROJECT AIMS TO INCREASE HABITAT FOR THE KIWIKIU #HawaiiFishing https://ifi.sh/p75

0 notes