#maui parrotbill

Photo

Hawai’ian monk selkie

#mermay#mermay 2023#mermaid#selkie#sea#monk seal#hawaiian monk seal#horses#birds#apapane#iiwi#maui parrotbill#akohekoe#hawaii amakihi#art#artblr

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Apapane (Himatione sanguinea)

The bright crimson ‘Apapane is part of a group of native Hawaiian birds, reminiscent of – but even more diverse than – the famed Galápagos finches. Known as the Hawaiian honeycreepers, these birds evolved into a varied group of dozens of species that originated from a few wayward ancestors. ‘Apapane feathers, along with those of other native birds, were prized by Native Hawaiians, who used them to adorn the capes, helmets, and feather leis of Hawaiian nobility. The bird's scientific name refers to a “blood-colored cloak.”

There were once more than 50 honeycreeper species found only in the Hawaiian Islands, but today just 17 remain, including the ‘I‘iwi and Kiwikiu, or Maui Parrotbill. The ‘Apapane is the most plentiful.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kiwikiu (Maui Parrotbill)

This honeycreeper has a uniquely shaped beak that allows it to remove bark and break open fruits to access insects living in the vegetation.

#Hawai'i#birds#hawai'ian birds#animals#wildlife#nature#ecology#habitat conservation#wildlife conservation

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Maui parrotbill is one of the most unique of all the Hawaiian honeycreepers. Named for its large, dramatically-hooked beak, the parrotbill uses this beak to peel bark, shred wood, and tear open fruits in search of grubs and insects. It is also critically endangered, with perhaps only 500 birds remaining in the wild.

#bird#birds#honeycreeper#honeycreepers#hawaiian honeycreeper#hawaiian honeycreepers#maui#maui parrotbill#maui parrotbills#animal#animals#hawaii#hawaiian#hawaiian animal#hawaiian animals#hawaiian bird#hawaiian birds#North America#north american#north american animal#north american animals#north american bird#north american birds#endangered#endangered species#critically endangered

468 notes

·

View notes

Link

Colleen Uechi for The Maui News:

The "remarkable" discovery of a rare Maui bird thought to have died 605 days ago has injected new life into the efforts to keep the species from extinction and validated years of forest restoration work.

A lone male kiwikiu, one of 14 released into the Nakula Natural Area Reserve in October 2019, was heard Wednesday by keen-eared conservationists who'd traveled up the leeward slopes of Haleakala to plant 700 native trees.

…

Two years ago, conservationists released a group of captive and wild kiwikiu, or Maui parrotbill, to reforested state land above the 5,000-foot-elevation level of leeward Haleakala in hopes that they would breed and expand across their new home. Nearly all of them fell victim to avian malaria, and the ones who couldn't be found were assumed to be dead.

…

[Hanna] Mounce said the best population estimate for the kiwikiu was 157 in 2019, and assuming they've declined since then, there's likely fewer than 150 left in the wild.

"sup" -- that bird

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

pacific parks maui parrotbill is a stellarian pride flag!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maui Forest Birds Critically Threatened

Maui Forest Birds Critically Threatened

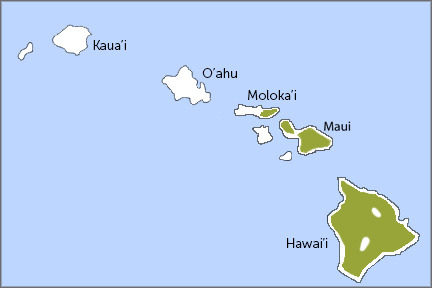

The kiwikiu, or Maui parrotbill, is only found in East Maui. There are less than 312 remaining in the wild

A new interagency monitoring report on Hawaiian forest birds indicates that remaining populations of at least two native endemic species of Maui forest birds are in rapid decline.

The surveys conducted in the report were the largest and most comprehensive interagency effort to research East…

View On WordPress

#akohekohe#crested honeycreeper#Haleakala National Park#Hanna L. Mounce#Hawaii Department of Forestry and Wildlife#Hawaii Department of Land Natural Resources Plant Extinction Prevention Program#Kahikinui Forest Reserve#KIWIKIU#Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project#Maui forest birds#Maui parrotbill#Nakula Forest Reserve#Natalie Gates#National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Pacific Island Network#Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit#Seth Judge#State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife#United States Geological Survey#University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo#USGS#weeklynews

0 notes

Photo

Hawaiian Honeycreeper

Hawaiian honeycreepers are small, passerine birds endemic to Hawaiʻi. They are closely related to the rosefinches in the genus Carpodacus. The group is divided into three tribes, but only very provisionally so. The wide range of bills in this group, from thick, finch-like bills to slender, downcurved bills for probing flowers have arisen through adaptive radiation, where an ancestral finch has evolved to fill a large number of ecological niches. Some 20 species of Hawaiian honeycreeper have become extinct in the recent past, and many more in earlier times, between the arrival of the Polynesians who introduced the first rats, chickens, pigs, and dogs, and hunted and converted habitat for agriculture.

Members of Psittirostrini, known as "Hawaiian finches", are granivorous with thick finch-like bills, and songs like those of cardueline finches. The group once covered the islands. Finch-billed drepanids include the Laysan finch, the Nihoa finch, the Maui parrotbill and the palila, which may be the last remaining species left alive in this group.

Hemignathini includes the Hawaiʻi creeper and its allies, such as the nukupuʻu. These are generally green-plumaged birds with thin bills, and feed on nectar and insects. Members of this group usually have green, yellow, orange, red, and gray feathers.

Species in the tribe Drepanidini are nectarivorous, and their songs contain nasal squeaks and whistles. Members of this group often have red black, yellow, white and orange plumage. It includes the ʻiʻiwi. Many species of this subfamily have been noted to have a plumage odor that has been termed the "Drepanidine odor", and is suspected to have a role in making the bird distasteful to predators.

#animal abc's#H#Hawaiian honeycreeper#i'iwi#scarlet honeycreeper#crested honeycreeper#palila#'amakihi#hawaiian finches#hawaiian animals#source: google

330 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

From **American Bird Conservancy Bird of the Week;

July 28, 2017**:

Hawai‘i 'Amakihi

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Chlorodrepanis virens

POPULATION: Approximately 800,000–900,000

TREND: Stable

HABITAT: Forests and shrubland at a wide range of elevations

One of the most common and adaptable of Hawaiian honeycreepers, the Hawai‘i 'Amakihi is found in all types of habitat, from sea level to 9,500 feet. Its presence at lower elevations seems to indicate that this species is evolving a tolerance to avian malaria, a disease spread by non-native mosquitoes that has driven species such as the ‘I‘iwi, a spectacular red honeycreeper, to higher elevations.

Although Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi populations appear stable, the birds are susceptible to the same threats facing other Hawaiian birds, including habitat loss and predation by introduced mammals such as rats and free-roaming cats.

A Separate Species

The Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi is currently found on three Hawaiian Islands: the Big Island, Maui, and Molokaʻi. It formerly occurred on the island of Lanaʻi but has not been seen there since 1976.

Genetic studies continue to fine-tune the evolutionary history of Hawaiian forest birds. For example, the Hawai‘i, Kaua‘i, and O‘ahu ‘Amakihi were once considered subspecies under the larger classification of Common ‘Amakihi. Recent research led to the classification of the Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, and Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi as three separate species.

Flexible Feeders

Hawai‘i ‘Amakihis finds food in a variety of ways, successfully foraging even in altered or degraded habitats. They glean tree bark and foliage for spiders and insects with their decurved bills, drink tree sap, and sip nectar from native flowers, including ‘ohi‘a and mamane, with tubular tongues.

These flexible feeders also eat fruit pulp and juice, and readily drink the nectar of non-native flowers and trees.

Productive Parents

Females of this species build an open-cup nest of grasses, twigs, and leaves lined with softer material such as lichen, rootlets, and animal hair. Males participate in the chick-rearing process by bringing food to the nest for the female and chicks. Even after fledging, young ‘Amakihi remain dependent on their parents for several weeks.

Hawaiian 'Amakihi feeding. Photo by Robby Kohley

This productive species usually raises two broods in a season, with the male taking over feeding duties for the first brood as the female begins the second. Hawai'i ‘Amakihi pairs remain together for successive breeding seasons.

Help Keep 'Amakihi Afloat

Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi have benefited from conservation work for other birds, including rare species such as Palila and Maui Parrotbill. ABC has collaborated with in-country partners on this work, which includes fencing habitat to keep it free of predators; controlling invasive species; and restoring forests.

We recently joined with several partner groups to ask Congress to support that would provide increased funding for endangered endemic birds.

Together with our partners, we're undertaking many conservation projects in Hawai‘i—but much remains to be done. You can help by supporting our Hawaiian Birds campaign before August 8!

#american bird conservancy#long post#bird calls#nature#wildlife#birds#finch#hawaiian honeycreeper#'amakihi#amakihi#Hawai'i 'Amakihi#Hawaii Amakihi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Addressing Challenges to Forests in the Hawaiian Islands

April 4th, 2017|Tags: forest threats, Wildlands for Wildlife, Wildlands for Wildlife—Hawaii|0 Comments

.fusion-fullwidth-1 { padding-left: px !important; padding-right: px !important; }

By Eric Sprague, American Forests

For tens of millions of years, the Hawaiian Islands have been isolated from the rest of the world by vast stretches of Pacific Ocean, with the nearest continent 2,000 miles away. Because of this isolation, the Hawaiian Islands developed unique forest ecosystems that resulted in an incredible amount of biodiversity. With 90 percent of land-based plants and animals occurring nowhere else, the Islands have the highest percentage of endemic species in the world.

The signature tree of the Hawaiian Islands is a great example of Hawaiʻi’s diversity. The early ancestor of the ʻōhiʻa lehua tree quickly adapted to the varied habitats present on the Islands. Today, the ʻōhiʻa lehua can be found at sea level as one of the first colonizers on new lava flows and at the limit where trees can survive at over 8,000 feet above sea level. It can also be found in poor soils at the edges of bogs and in the wettest rainforests in the world. In these various environments, the tree can occur as a shrub or a 100-foot-tall tree. The ʻōhiʻa lehua has adapted so well that it is the most abundant and widespread tree making up 80 percent of Hawaiʻi’s forests.

The ‘i’iwi, or scarlet honeycreeper, has seen the steepest decline of any honeycreeper in recent decades. Credit: Caleb Slemmons

The nectar-producing flowers of the ʻōhiʻa lehua are favored by many species among the spectacularly diverse Hawaiian honeycreepers. The ancestors of these birds were likely from a single species that, like the ʻōhiʻa lehua, quickly adapted to exploit different habitats, which produced great diversity in bill size, bill shape and color. For example, the Maui parrotbill (kiwikiu) uses its parrot-like bill to strip bark and break branches to search for insect larvae and the scarlet honeycreeper (ʻiʻiwi) uses its long decurved bill to feed on nectar.

Yet, this spectacularly unique and diverse flora and fauna is under threat. Within the last few hundred years, the loss of habitat and widespread distribution of nonnative plants and animals have wreaked havoc on Hawaiian forests and the wildlife that call them home, making Hawaiʻi the “extinction capital of the world.” While comprising less than one percent of the Unites States’ land mass, 40 percent of all plant and animals listed as threatened or endangered in the U.S. are found in Hawaiʻi.

The status of Hawaiian honeycreepers and the ʻōhiʻa lehua are tied to these trends. Today, less than half of the 51 formerly known honeycreepers are still found in Hawaiian forests. There are only around 500 Maui parrotbills remaining and the scarlet honeycreeper has seen the steepest decline of any honeycreeper in recent decades. Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death is a new fungal disease that can kill trees within days. The loss of this tree will transform Hawaiian forests.

Hawaiian forests, host to a variety of endemic plant and animal species, face multiple threats. Credit: Bernard Spragg

Restoration efforts through our Wildlands for Wildlife initiative are aimed to help these evolutionary wonders recover and thrive in Hawaiian forests once again. This year, American Forests is partnering with the Hawaiian Forest Institute to restore native forest by removing invasive weeds and planting native plants at the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center’s Discovery Forest. The Center and Discovery Forest are part of a restoration and education project, which seeks to engage young people in forest stewardship learning opportunities and forge connections between science and native Hawaiian culture. The connection between forests and people will be critical to maintaining support for restoration.

The post Addressing Challenges to Forests in the Hawaiian Islands appeared first on American Forests.

from American Forests http://www.americanforests.org/blog/addressing-challenges-forests-hawaiian-islands/

0 notes

Text

Go read this story about why it’s time to scrap racist bird names

An illustration of a Maui parrotbill perched on a branch. | Photo by Brown Bear/Windmill Books/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Some 150 birds named for people tied to slavery and white supremacy could eventually get new monikers as part of an ongoing reckoning with racism within the world of birding. That includes Jameson’s firefinch, named for a British naturalist who bought a young girl…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Kiwikiu Birdbeast by Ciameth

I love Hawaiian birds, so I doodled a Kiwikiu, aka Maui Parrotbill (Pseudonestor xanthophrys) for DailyBirdBeast's invitation for guest birdbeasts.

http://dailybirdbeast.tumblr.com/

97 notes

·

View notes