#Lepidodendron fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

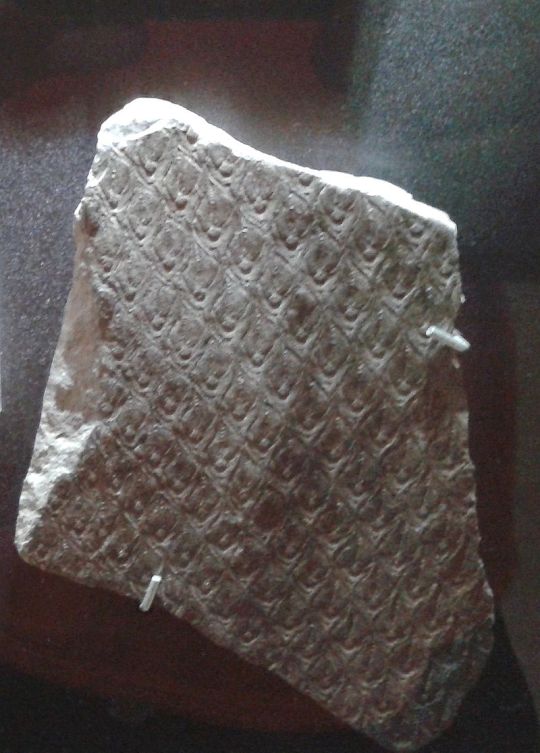

Lepidodendron Fossil Stem – Carboniferous Plant Fossil – Coal Measures – Radstock, Somerset, UK

Genuine Lepidodendron Stem Fossil – Carboniferous Period – Radstock, Somerset, UK

This is a fine example of a Lepidodendron stem fossil – a relic of an ancient lycopsid tree that once towered over Carboniferous swamplands. This piece was recovered from the classic Coal Measures of Radstock, Somerset, a region famous for its rich palaeobotanical heritage.

Fossil and Geological Information:

Species: Lepidodendron (exact species undetermined)

Family: Lepidodendraceae

Order: Lepidodendrales

Class: Lycopodiopsida

Geological Stage: Pennsylvanian Subsystem, Late Carboniferous (~310 million years ago)

Formation: British Upper Coal Measures

Location: Radstock, Somerset, UK

Depositional Environment: Equatorial deltaic swamps, ideal for forming peat-rich layers later turned into coal

Notable Morphological Features:

Distinctive diamond-shaped leaf scars arranged in spiral rows, left by fallen microphylls

Ribbed or bark-like surface textures indicative of its large, arborescent form

Rare preservation showing clear stem features of a major component of Carboniferous forests

Palaeontological Context:

Lepidodendron was a dominant genus in the Carboniferous forests and contributed significantly to coal formation. Known as a “scale tree,” it could grow over 30 meters high. This stem fossil captures the unique and unmistakable leaf scar patterns that define the genus.

Specimen Details:

Discovered by: UKGE team members Alister and Alison

Discovery Date: 06 March 2025

Prepared by: Alison

Scale Information: Scale cube shown = 1cm – see photo for precise dimensions

Photographic Guarantee: The item pictured is the exact specimen you will receive

Authenticity: Includes a signed Certificate of Authenticity. We guarantee all our fossils are 100% genuine and responsibly collected.

Why This Fossil is Important:

Lepidodendron was a cornerstone of prehistoric forest ecosystems during the Carboniferous period, influencing the development of today’s ecosystems and even contributing to modern fossil fuel deposits. This well-preserved specimen is not only ideal for collectors but also serves as an excellent educational piece demonstrating the structure and texture of ancient lycopsid trees.

An iconic and timeless addition to any fossil collection.

#Lepidodendron fossil#Carboniferous plant fossil#fossil stem impression#fossil lycopsid tree#Lepidodendron stem#Coal Measures fossil#Carboniferous flora#Radstock fossil plant#authentic fossil stem#lycopodiophyta#British fossil plant#prehistoric swamp forest#fossil bark impression

0 notes

Text

So, the bee nest is cool, but know what's even cooler?!

Possible Lepidodendron leaf fossil!!

Even better, it's in what I believe is Chert! I found it in my neighbor's rock landscaping. 🤩💕

Disclaimer: I have his permission to take stuff from both his yard and his rocks. 🫡

#random#nature#life#paleontology#paleoblr#paleomedia#fossils#fossil collection#Lepidodendron#dinosaurs#paleozoic era#rock#rocks and minerals#minerals

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louvre-Lens : il y a une expo : “Mondes souterrains : 20.000 Lieux sous la terre”. la suite et fin.

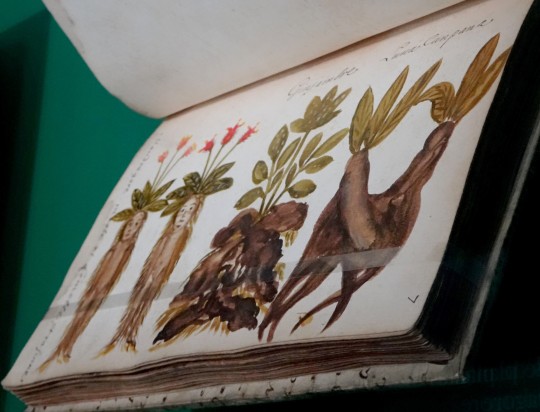

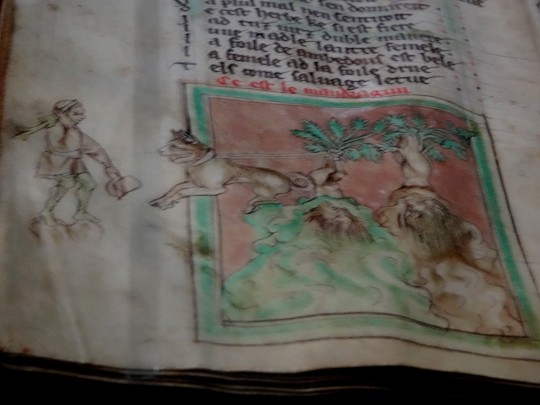

anonyme - recueil de figures de plantes - la Mandragore - XVIIe s.

Guillaume Le Clerc - "Bestiaire divin - Récolte de la Mandragore" - 1270 (pour info, il faut l'accrocher à la queue d'un chien pour la déterrer et se boucher les oreilles car elle hurle un cri pouvant tuer, en étant extirpée...Pas simple)

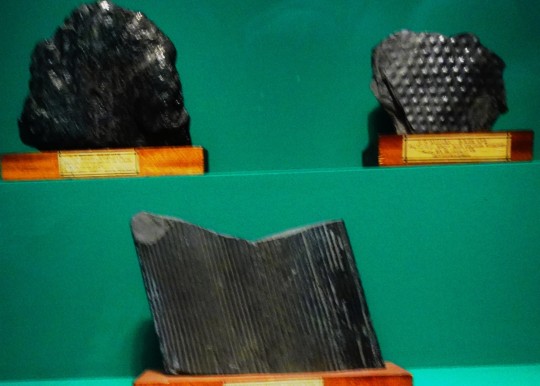

carottage de roches du Stéphanien (étage du Carbonifère, Paléozoïque) -390m, Vosges

gaillette de charbon (-1261m sous Maisnil); Lépidodendron (-930m sous Calonne); Neuroptéris (-1210m sous Ruitz)

#louvre-lens#expo#mondes souterrains#20.000 lieux sous la terre#géologie#botanique#mandragore#monstre#guillaume le clerc#bestiaire#carbonifère#stéphanien#vosges#fossile#charbon#maisnil#calonne#ruitz#ptéridophytes#neuropteris#lepidodendron#paléozoïque

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey plant man, I like your plant posts. Should give us a lil plant post to rotate in our brains if you have some time. Take this as permission to sling spaghetti at the wall for whatever Plant Stuff has been in ur head

(I also feel like i should tell you that I cannot for the life of me remember when I started following this blog but going through your lichen posts had me telling all my direct family members how much lichen now baffles me, so thank u for reminding me that Science Does Not Know All)

for years i've strongly envisioned a plant museum exhibit i would make if i ever became the guy who got to do that. imagine the biggest wall in the exhibit dedicated to showing how lepidodentrons became modern plants (and it would be utilized for that instead of some crowd pleaser dinosaur because of isoetes favoritism for me only, i would insist the space be used like that instead of something more cohesive. I would take the public and say LOOK AT IT). it starts at the left side with a life-sized lepidodendron silhouette and shows species getting smaller and smaller along the wall until the far right, where there's an aquairium with isoetes collected from the closest healthy isoetes population, preferably in the same area so people can be like 'whoa so close to us'.

version two of this exhibit would be to just have a tank of local isoetes beside a life-sized lepidodendron silhouette or replica so you could compare the sizes more directly. version three of this exhibit would be to put a tank of isoetes at that place in scotland that has the grove of fossilized lepidodendron stumps still upright in place from when their grove got flooded for the last time.

any of these would have merch in the gift shop too by the way.

#isoetes#asks#plont asks#ive been rotating isoetes in my mind again since ive been applying for jobs. just thinking about them again#like dude theyre just so crazy. just absolutely baffling creature#paleobotany#science communication

862 notes

·

View notes

Text

My 25 years of palaeoart chronology...

In 2000 I received my first big commission. Manchester Museum paid me to create two large murals, 21 illustrations, and some themed 3D exhibits.

Here are the two murals, painted by hand on canvas, and in the foreground are some of the themed exhibits, which surrounded a Lepidodendron fossil and some marine reptiles.

#Art#Painting#PaleoArt#PalaeoArt#SciArt#SciComm#DigitalArt#Illustration#Dinosaurs#Birds#Reptiles#Palaeontology#Paleontology

461 notes

·

View notes

Text

March Madness Round 2 Bracket 2

Welcome back to another day of March Madness. Let's see who made it through to compete today! Our first competitor is Jaekelopterus the giant eurypterid! It crushed Arthropleura by 11 points. This arthropod is found in early Devonian rocks in Europe and North America.

It is up against the giant clubmoss relative Lepidodendron which beat out Araucaria by only two points! Lepidodendron fossils have been found across the globe in rocks dating to the Late Carboniferous all the way until the end Permian Extinction event.

#paleontology#fossils#science education#science#geology#march madness#science side of tumblr#vascular plants#arthropods

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Image, as well as much of my information, from Carboniferous Giants and Mass Extinction by George R. McGhee Jr.)

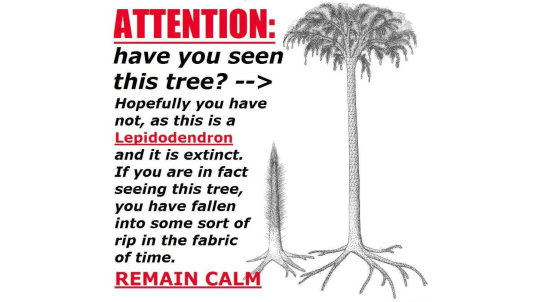

Take a look at this tree. On a scale of 1 to 10, how weird do you think it is?

You quite possibly just gave it a 3 or a 4 or something. Sure, it's a little odd, but does look vaguely normal, right? A friend of mine guessed it was some sort of baobab when I showed him the image.

This is, in fact Lepidodendron, an ancient tree from the Carboniferous, and by modern tree standards it is absolutely bizarre. Its closest surviving relatives, quillworts and clubmosses, only grow to a height of a few centimetres, yet Lepidodendron were giants that shot up to 50 metres tall... Briefly, before dispersing their spores and completely dying off.

(Lycopodium and Spinulum, modern relatives of Lepidodendron, photos by Bernd Haynold and Pete Pattavina)

You see, Lepidondron lived like a gigantic dandelion. For most of its life, it was a stumpy little thing that stuck close to the ground. Just an odd scaly green stump with some long leaves poking out. The green scales its bark consisted of were the place it conducted its photosynthesis, and thus basically did the work of leaves. The Lepidodendron would stay like this for a couple years, slowly expanding its roots and getting ready for the next step. But its roots would grow mostly horizontally, down not so much! And part of why is that even they had the scaly leaf-like photosynthetic bark. That's right, even their roots could - and to some extend needed to - photosynthesise!

(Fossil Lepidodendron bark in the National Museum of Brazil, photo by Dornicke; a fossilised relative of Lepidodendron with some of its roots visible, photo by Michael C. Rygel)

So why would you ever try to photosynthesise with your roots of all things as a plant? Surely it would make much more sense to just transport the sugars created in other parts there than to have your roots be so shallow that bits of them can catch a little light and make it in situ? Sure, if you're capable of that! This is what modern trees do, but they have two separate vascular tissues they use for transport: xylem, which moves water from the roots to the rest of the plant, and phloem, which moves sugars and other photosynthetic products from the leaves to the rest of the plant. Unfortunately for Lepidodendron, it only had xylem, no phloem, so its sugars were only ever going to move as far as they could diffuse, so every part of the tree needed to have at least a little photosynthesis happening, even the roots.

This truly gets ridiculous when the Lepidodendron decides after a few years of charging up that it's time to reproduce. That's when the weird green stump we have so far starts shooting up, up, up, very quickly, all the way until an enormous 40 or 50 metres in height. Now, modern trees grow this large by being supported by a sturdy wooden core, but that's not what Lepidodendron did. To hold up the entire tree, it relies entirely on its outer bark thickening as it grows. In mechanical terms, it was little more than a huge hollow pole, probably creaking and swaying terribly in the wind. Although I have not been able to confirm this in the literature so far, I suspect that between the shallow roots and the whole thing being held up by its bark, you could probably total a Lepidodendron with a good kick.

Now remember, all this growth is happening without phloem, so the entire length of that stem has to not just be sturdy enough to keep the tree standing, but it also has to keep doing photosynthesis to feed itself. When it reaches its full height, the top of the tree finally starts sprouting branches and small leaves, leaving it looking like the picture at the start. But those are not what it's all about for the tree: the cones that develop among them are. At a height of 50 metres, the spores produced by the cones can very easily be picked up by the wind and blown far, far away. Being spores, rather than seeds as modern trees have, they have no supplies built in whatsoever, so they need to get lucky to land in a spot that has immediate access to water. Luckily, there are a lot of those in the vast Carboniferous swamps, and with the trees doing so much work to spread the spores very widely, some of them are sure to find good spots. And then, with the spores dispersed, the tree is done for. The entire thing, which has just grown to the skies, dies off and soon comes crashing down.

So how weird is this tree? I'd call it a perfect 10.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life in the Carboniferous

(first row: Diplocaulus, Lepidodendron, Arthropleura; second row: Meganeura, Hylonomus, Walchia, Pulmonoscorpius; third row: Tullimonstrum, Calamites, Edestus; fourth row: Pederpes, Eryops, Stethacanthus)

Art by:

Pederpes - Ntvtiko

Lepidodendron - Richard Bizley

Calamites - Jonathan Hughes

Walchia - Dinoraul

Arthropleura - Vladislav Egorov

Meganeura - Walking with Monsters

Pulmonoscorpius - Plioart

Hylonomus - John Sibbeck

Diplocaulus - Sergey Krasovskiy

Eryops - mmuyano

Tullimonstrum - Nobu Tamura

Edestus - Julio Lacerda

Stethacanthus - Ja Chirinos

It‘s the age of giant bugs!

But before I get to talk about giant bugs, we have to take a moment and appreciate the real stars of the Carboniferous: The plants! The whole reason it is called Carboniferous (“coal-bearing“) is because of them. The forests of the time got flooded repeatedly, decayed, rotted and over the ages have turned into coal deposits that we use today. So whenever you hear people talk about fossil fuels coming from dinosaurs you can “well-actually“ them and talk about ancient plants instead.

During the Carboniferous earth was a warm, humid place with lots of tropical swamp forests. Some of the plants you would have seen there are roughly familiar to us today, like ferns. Similar looking were the seed ferns, which are extinct today. They reproduced by making seeds (shocking, I know), unlike “regular“ ferns, that reproduce via spores.

In some cases the plant groups are still around today, but they look nothing like their Carboniferous counterparts. Calamites for example was a horsetail that grew into more than 30 m high tree-like structures. Closely related to the small modern clubmosses were the Lepidodendrales (“scale trees“, named after their bark, which looked like scaly reptile skin). Lepidodendron could grow up to 50 m tall and would have spend most of its life as a single unbranched stem, which definitely added to the weird alien feel of Carboniferous forests. A more familiar sight were the earliest conifers, like Walchia, which lived during the late Carboniferous. Many other modern plants including grasses, flowers or hardwood trees, like maples or oaks, weren‘t around yet and wouldn‘t be for many millions of years.

Now that we have established that the forests of the time were strange and alien filled with plants of all kinds of weird shapes and unusual sizes, let‘s look at the bugs, which were also having all the wrong sizes:

Among many others there was the dragonfly cousin Meganeura with a wingspan of more than 70 cm, Pulmonoscorpius, an about 70 cm long scorpion and Arthropleura, a truly gigantic millipede, more than 2 m long. It was comparable in size to the biggest sea scorpions and one of the biggest arthropods that ever lived.

The questions is of course, why were insects and other arthropods this big? The main answer is oxygen. Insects have a very different breathing system than we do and it doesn‘t scale well with size. Because of that they have a size limit. At some point, they just can‘t get enough oxygen into their bodies (thankfully, because I don‘t need giant spiders or mosquitos or whatever). During the Carboniferous however, there was a lot more oxygen in the atmosphere than there is today, so the arthropods could grow much bigger than they do today.

Another reason for the giant bugs might be, that they didn‘t really have a lot of competition. There was nothing to keep them in check, so evolution just went wild with them. You have to remember that, while insects were already taking to the skies, the proudest accomplishment of our tetrapod ancestors was crawling from one puddle to another. To say that arthropods had a head start would be an understatement. So for future references, remember that every time I mention a cool thing any vertebrate does, there probably was an insect that did the same thing millions of years earlier.

But speaking of the tetrapods: They were getting better at crawling between puddles. We get the first true amphibians like boomerang-headed Diplocaulus and the giant Eryops, one of the biggest land animals of the time (you know, roughly milliped-sized). Maybe even more exciting was that during this time we see the first amniots! That‘s right, there are animals that lay eggs now. Real, actual eggs, that can survive without water. These lizard-like creatures (they aren‘t actual lizards, those will take a lot longer to evolve) can finally leave the puddles and rivers their amphibian cousins have been bound to.

It‘s probably a good thing, that they can leave the water behind, because there was some very weird shit going on in the oceans. After the placoderms went extinct during the late Devonian mass extinction (rip), a lot of bizarre shark relatives showed up, like Stethacanthus with its anvil shaped dorsal fin or the absolute horror that is Edestus.

But the weirdest thing of the Carboniferous (maybe one of the weirdest things ever) has to be the Tully monster (btw, not really a monster, only about 35 cm long). I mean, just look at it. It has a mouth that is separated from the rest of its body by a proboscis. It has stalked eyes. It is weird as fuck. We also have absolutely no idea what it is. Science agrees that it is an animal, and that‘s about it. There are arguments for it being a vertebrate, an arthropod, a mollusc, a worm and pretty much anything else you could think of. Honestly I just love it because of how strange and fake it looks.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wish I knew how to make a creature collecting video game. Dinosaur themed creature games Have been done a lot but I want to do it too

#my art#i guess the thing id use to set this apart from other dinosaur things is including non-animal fossils#lepidodendron guy was a big hit in the groupchat i love him#the dunkle line is my personal fav so far... check out that dunklet

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rise and Fall of the Scale Trees

If I had a time machine, the first place I would visit would be the Carboniferous. Spanning from 358.9 to 298.9 million years ago, this was a strange time in Earth’s history. The continents were jumbled together into two great landmasses - Laurasia to the north and Gondwana to the south and the equatorial regions were dominated by humid, tropical swamps. To explore these swamps would be to explore one of the most alien landscapes this world has ever known.

The Carboniferous was the heyday for early land plants. Giant lycopods, ferns, and horsetails formed the backbone of terrestrial ecosystems. By far the most abundant plants during these times were a group of giant, tree-like lycopsids known as the scale trees. Scale trees collectively make up the extinct genus Lepidodendron and despite constantly being compared to modern day club mosses (Lycopodiopsida), experts believe they were more closely related to the quillworts (Isoetopsida).

It is hard to say for sure just how many species of scale tree there were. Early on, each fragmentary fossil was given its own unique taxonomic classification; a branch was considered to be one species while a root fragment was considered to be another and juvenile tree fossils were classified differently than adults. As more complete specimens were unearthed, a better picture of scale tree diversity started to emerge. Today I can find references to anywhere between 4 and 13 named species of scale tree and surely more await discovery. What we can say for sure is that scale tree biology was bizarre.

The name “scale tree” stems from the fossilized remains of their bark, which resembles reptile skin more than it does anything botanical. Fossilized trunk and stem casts are adorned with diamond shaped impressions arranged in rows of ascending spirals. These are not scales, of course, but rather they are leaf scars. In life, scale trees were adorned with long, needle-like leaves, each with a single vein for plumbing. Before the started branching, young trees would have resembled a bushy, green bottle brush.

As scale trees grew, it is likely that they shed their lower leaves, which left behind the characteristic diamond patterns that make their fossils so recognizable. How these plants achieved growth is rather fascinating. Scale tree cambium was unifacial, meaning it only produced cells towards its interior, not in both directions as we see in modern trees. As such, only secondary xylem was produced. Overall, scale trees would not have been very woody plants. Most of the interior of the trunk and stems was comprised of a spongy cortical meristem. Because of this, the structural integrity of the plant relied on the thick outer “bark.” Many paleobotanists believe that this anatomical quirk made scale trees vulnerable to high winds.

Scale trees were anchored into their peaty substrate by rather peculiar roots. Originally described as a separate species, the roots of these trees still retain their species name. Paleobotanists refer to them as “stigmaria” and they were unlike most roots we encounter today. Stigmaria were large, limb-like structures that branched dichotomously in the soil. Each main branch was covered in tiny spots that were also arranged in rows of ascending spirals. At each spot, a rootlet would have grown outward, likely partnering with mycorrhizal fungi in search of water and nutrients.

Eventually scale trees would reach a height in which branching began. Their tree-like canopy was also the result of dichotomous branching of each new stem. Amazingly, the scale tree canopy reached staggering heights. Some specimens have been found that were an estimated 100 ft (30 m) tall! It was once thought that scale trees reached these lofty heights in as little as 10 to 15 years, which is absolutely bonkers to think about. However, more recent estimates have cast doubt on these numbers. The authors of one paper suggest that there is no biological mechanism available that could explain such rapid growth rates, concluding that the life span of a typical scale tree was more likely measured in centuries rather than years.

Regardless of how long it took them to reach such heights, they nonetheless would have been impressive sites. Remarkably, enough of these trees have been preserved in situ that we can actually get a sense for how these swampy habitats would have been structured. Whenever preserved stumps have been found, paleobotanists remark on the density of their stems. Scale trees did not seem to suffer much from overcrowding.

The fact that they spent most of their life as a single, unbranched stem may have allowed for more success in such dense situations. In fact, those that have been lucky enough to explore these fossilized forests often comment on how similar their structure seems compared to modern day cypress swamps. It appears that warm, water-logged conditions present similar selection pressures today as they did 350+ million years ago.

Like all living things, scale trees eventually had to reproduce. From the tips of their dichotomosly branching stems emerged spore-bearing cones. The fact that they emerge from the growing tips of the branches suggests that each scale tree only got one shot at reproduction. Again, analyses of some fossilized scale tree forests suggests that these plants were monocarpic, meaning each plant died after a single reproductive event. In fact, fossilized remains of a scale tree forest in Illinois suggests that mass reproductive events may have been the standard for at least some species. Scale trees would all have established at around the same time, grown up together, and then reproduced and died en masse. Their death would have cleared the way for their developing offspring. What an experience that must have been for any insect flying around these ancient swamps.

Compared to modern day angiosperms, the habits of the various scale trees may seem a bit inefficient. Nonetheless, this was an extremely successful lineage of plants. Scale trees were the dominant players of the warm, humid, equatorial swamps. However, their dominance on the landscape may have actually been their downfall. In fact, scale trees may have helped bring about an ice age that marked the end of the Carboniferous.

You see, while plants were busy experimenting with building ever taller, more complex anatomies using compounds such as cellulose and lignin, the fungal communities of that time had not yet figured out how to digest them. As these trees grew into 100 ft monsters and died, more and more carbon was being tied up in plant tissues that simply weren’t decomposing. This lack of decomposition is why we humans have had so much Carboniferous coal available to us. It also meant that tons of CO2, a potent greenhouse gas, were being pulled out of the atmosphere millennia after millennia.

As atmospheric CO2 levels plummeted and continents continued to shift, the climate was growing more and more seasonal. This was bad news for the scale trees. All evidence suggests that they were not capable of keeping up with the changes that they themselves had a big part in bringing about. By the end of the Carboniferous, Earth had dipped into an ice age. Earth’s new climate regime appeared to be too much for the scale trees to handle and they were driven to extinction. The world they left behind was primed and ready for new players. The Permian would see a whole new set of plants take over the land and would set the stage for even more terrestrial life to explode onto the scene.

It is amazing to think that we owe much of our industrialized society to scale trees whose leaves captured CO2 and turned it into usable carbon so many millions of years ago. It seems oddly fitting that, thanks to us, scale trees are once again changing Earth’s climate. As we continue to pump Carboniferous CO2 into our atmosphere, one must stop to ask themselves which dominant organisms are most at risk from all of this recent climate change?

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]

Further Reading: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]

#Isoetopsida#monocarpic#stigmaria#Lepidodendron#coal#greenhouse gas#scale tree#carboniferous#climate change#fossils#Lycopodiopsida#coal swamp#paleobotany#plant fossils

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stigmaria Fossil Stem Carboniferous Coal Measures Scotland UK | Musselburgh Plant Fossil with Certificate

This listing is for a beautifully preserved Stigmaria fossil stem, originating from the Carboniferous Period, specifically the Coal Measures of Musselburgh, near Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. This is a genuine piece of ancient plant life from approximately 310–300 million years ago, dating to the late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) sub-period.

The fossil shown in the photos is the exact specimen you will receive. It has been carefully selected for its distinct features and natural history significance, making it ideal for collectors, educators, and anyone interested in palaeobotany.

Geological & Palaeontological Details:

Fossil Type: Root/stem structure (rhizomorph) of an ancient lycopsid plant

Genus: Stigmaria (likely belonging to the root system of Lepidodendron or Sigillaria)

Order: Lepidodendrales

Geological Period: Carboniferous

Stage: Pennsylvanian (Westphalian)

Stratigraphy: Coal Measures (part of the Scottish Coal Measures Group)

Location: Musselburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

Depositional Environment: Low-lying equatorial swamp and floodplain environments where dense lycopod forests flourished. These environments formed the organic-rich layers that eventually transformed into coal seams.

Morphology & Features:

Stigmaria is characterised by a cylindrical, branching root structure with spirally arranged rootlet scars, forming the distinctive pitted pattern seen on the fossil’s surface

The preserved features show clear detail of the rootlet attachment points that supported anchorage in soft, waterlogged substrates

Typically preserved in grey shale or siltstone, reflecting anoxic burial conditions ideal for fossilisation

Provides key insights into the rooting systems of Carboniferous lycopod trees, the dominant flora of ancient coal-forming forests

Notability: Stigmaria fossils are among the most iconic plant fossils of the Carboniferous. Their distinct morphology and association with Lepidodendron and Sigillaria make them critical to understanding the ecology and evolution of the Earth’s earliest forested ecosystems. This specimen, from the historically significant coalfields near Musselburgh, represents a rare and regionally important find.

Additional Details:

All our fossils are 100% genuine specimens

Includes a Certificate of Authenticity

Photo shows the exact fossil for sale

Scale cube = 1cm – please refer to photos for precise sizing

Whether for education, research, or private display, this specimen offers a tangible connection to the lush primeval landscapes that once covered prehistoric Scotland. A perfect addition to any fossil or palaeobotanical collection.

#Stigmaria#plant fossil#Carboniferous fossil#Coal Measures#fossil stem#root fossil#Lepidodendron root#Musselburgh fossil#Edinburgh fossil#Scottish fossil#UK plant fossil#genuine fossil#fossil with certificate#fossil roots#Carboniferous flora#Stigmaria fossil stem#ancient plant fossil#fossilised roots#fossil collector specimen#Stigmaria rhizome

0 notes

Photo

Fossil Grove

Lurking in a building in Glasgow's Victoria Park is a memory of a different, tropical Scotland, unafflicted by snow, wind, or bitterly cold driving rain. Freshly joined to its new home of Avalonia to form the nascent land of Britain during the Caledonian Orogeny, the area was a swampy and steamy place back in the Carboniferous, in which peat accumulated in large forested river deltasinto the coal that would much later fuel an industrial revolution. The surrounding tropical seas were filled with coral reefs. The sea level oscillated, leaving a variety of shallow marine, coastal and terrestrial sediments that were later transformed into rock (a complex process known as diagenesis).

A rainforest of 'trees' (actually giant mosses called Lepidodendron) grew where Glasgow is now, and in 1877, eleven stumps of these 330 million year old trees were uncovered from the surrounding sandstone and shale during the transformation of an abandoned quarry into the park as the newly industrial city expanded.

Loz

Image credit: Visit Scotland http://www.museumsgalleriesscotland.org.uk/member/fossil-grove http://www.snh.gov.uk/about-scotlands-nature/rocks-soils-and-landforms/rocks-and-minerals/rocks-formed-after/carboniferous/

#Lepidodendron#tree#fossil#forest#geology#fossils#fossilfriday#limestoen#glasgow#scotland#victoria park#caledonian#carboniferous#the earth story

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

lepidodendron fossils (root impressions,, the holes are vertical roots and the long shallow textured trough is a horizontal root)

There are lots of lycopods nearby, many herbariums have lycopod samples that go back centuries, with DNA that can be used in next gen sequencing …

I like to think the lycopods and the fossils are sitting there together like when you go to a graveyard and wonder if anyone there is a distant distant ancestor of yours

Basalt of an old volcano chamber and the conduit extending out of it. Similar to columnar basalt hexagon time but radial due to the round chamber !

Rough timeline:

Volcano is probably Devonian, most igneous rock here is,

Equatorial swamp in Carboniferous -> lepidodendron and extensive coal veins. Cool sedimentary rock too, with visible effects of tidal deposition,

From then on drift to higher latitudes. And other new places.

#miaow#palaeo#paleontology#palaeontology#Carboniferous#lepidodendron#lycopod#lycophyte#lycopodiopsida#Devonian#volcano#geology

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

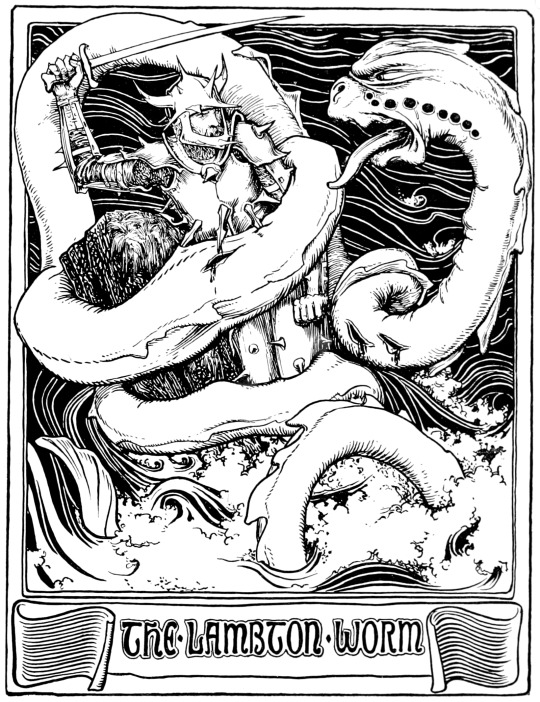

Illustration of the Lambton Worm by C. E. Brock from English Fairy and Other Folk Tales.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot since reading Poli and Stoneman’s 2020 paper about the link between fossil club mosses from ancient coal swamps and dragon lore.

Looking deeper into a few tales reveals their relationships to the plant fossils’ appearance as well as their locations. Ac- cording to lore, John Lambton yanks the Lambton worm from the Wear River on the end of a fishing line and flings it into a well, where it reaches enormous size [38]. Years later, pieces of the worm are hacked off in an effort to kill it, but it regenerates these parts and lives on. Lambton’s worm grows so large that it can wrap itself around a hill seven times, a feat that causes a (still-visible) circular indentation around Worm Hill, located near a documented fossil site. Eventu- ally, Lambton hacks the worm to pieces, which float down the Wear before the worm is finally torn completely apart, having impaled itself on Lambton’s armor. Note that Lamb- ton’s estate sits at the site of lead, coal and limestone mines that have operated for centuries. Interestingly, up until the seventeenth century, coal was believed to be a living thing with “special seeds for its reproduction and growth under the ground” [39]. Could the pieces of the Lambton worm that washed down the Wear River have been the coal-black, scaly fossils of Lepidodendron?

https://direct.mit.edu/leon/article/53/1/50/46847/Drawing-New-Boundaries-Finding-the-Origins-of

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Fossil Grove

When I visited Victoria Park here in Glasgow the main reason was to see the Fossil Grove, a group of eleven fossilised stumps of Lepidodendron trees dating back to the Carboniferous, when amphibians were the dominant vertebrates, and discovered in 1887 while the park was being built. Really an impressive experience to imagine these primitive trees alive, standing exactly where they still are and towering over a completely different landscape.

At the site I also met an elderly lady who introduced herself as an amateur geologist and we had a really interesting chat about the story of these trees. Unfortunately she also pointed out the lack of funding in keeping Glasgow’s most ancient attraction in good order -you can see the white deposit on the rocky soil caused by water infiltration- which is really a shame when you think the city owes its industrialisation to coal provided by ancient rainforests of these and other trees and plants, like Sigillaria and Neuropteris, some small fossils of which are on display there too. That’s why the geological era they where extant in is called Carbonifererus, which in Latin means ‘carbon-bearing’,

#fossil grove#victoria park#lepidodendron#fossil#fossil trees#carboniferous#archaeobotany#archeology#paleobotany#geology#botany#plantblr#plants#glasgow#scotland#trees

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Once In A Lifetime…

3 notes

·

View notes