#London Charterhouse

Text

SAINTS OF THE DAY (May 4)

The Carthusian Martyrs of London were the monks of the London Charterhouse, the monastery of the Carthusian Order in the city of London who were put to death by the English state.

The method of execution was hanging, disembowelling while still alive, and quartering. Others were imprisoned and left to starve to death.

These 18 Carthusian monks were put to death in England under King Henry VIII between 1535-1540 for maintaining their allegiance to the Pope.

The Carthusians, founded by St. Bruno in 1054, are the strictest and most austere monastic order in the western Church.

They live an austere hermitic life, their ‘monastery’ actually being a number of hermitages built next to each other.

When Henry VIII issued his “Act of Supremacy” declaring that all who refused to take an oath recognizing him as head of the Church of England committed an act of high treason, these 18 Carthusians refused and were sentenced to death.

The first to die were the Carthusian prior of London, John Houghton, and two of his brothers, Robert Lawrence and Augustine Webster, who were hanged, drawn and quartered, on 4 May 1535.

The prior is said to have declared his fidelity to the Catholic Church and forgiven his executioners before dying.

The Carthusians were the first martyrs to die under the reign of Henry VIII.

Two more were killed on June 19 of that year. By 4 August 1540, all 18 had been tortured and killed for refusing to place their allegiance to the king before their allegiance to the Pope.

They were beatified by Pope Leo XIII on 29 December 1886.

John Houghton, Robert Lawrence, and Augustine Webster were canonized by Pope Paul VI on 25 October 1970.

#Saints of the Day#English Carthusian Martyrs#Carthusian Martyrs of London#London Charterhouse#Carthusian Order#Carthusians#St. Bruno#King Henry VIII#Act of Supremacy

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

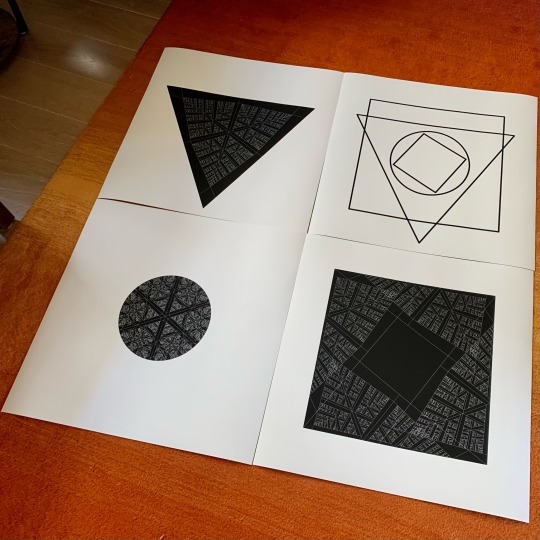

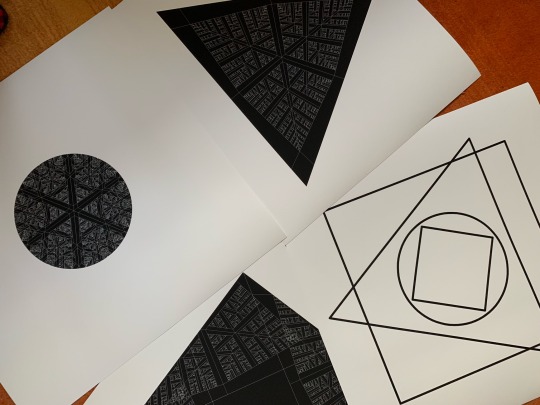

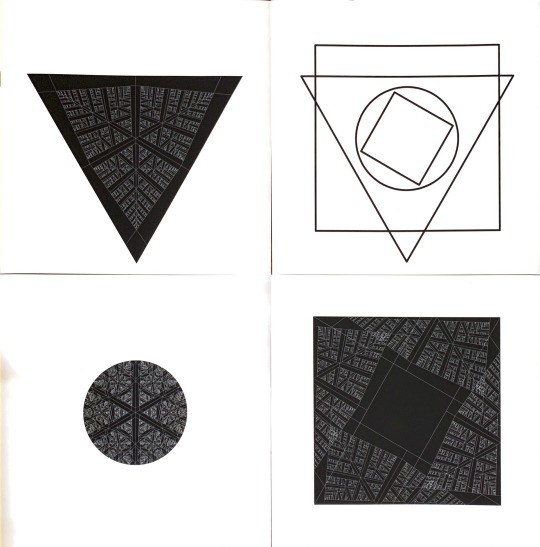

Prints arrived home today for the OCAS Biennial. Thank you @onlinereprographics; exquisite line work

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Roger Williams

Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE) was a Puritan separatist minister best known for his conflict with both the Plymouth Colony and Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1633-1635 CE, resulting in his banishment and founding of the colony of Providence, Rhode Island. Williams believed that the clergy of both Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay were corrupt in continuing to adhere to the concept of one's deeds as an important aspect of spiritual salvation rather than acknowledging the biblical precept that only God's grace grants salvation (Romans 8:32, Ephesians 2:8). Further, he claimed, these churches were still aligned with the basic policies of the Anglican Church they had supposedly rejected.

Williams is also well-known as an advocate for the separation of church and state (claiming that politics poisoned religious practice and belief), complete religious freedom, the abolition of slavery in the colonies of North America, and respect for Native Americans. One of his criticisms of the colonies of New England was that they felt free to take land from the Native Americans without payment. When he founded Providence, he paid the Narragansett tribe a fair price for the land.

Providence became the first successful liberal colony in New England which was not informed by Puritan ideals and theology. Anyone of any religion or ethnicity was welcome to settle there as long as they recognized the fundamental human right of what Williams called the "liberty of conscience" – the freedom to express one's self - especially in religious matters, without fear of persecution or reprisal. Providence was scorned by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, especially, as populated by riffraff, lunatics, and heretics but became one of the fastest-growing settlements in the region under Williams' vision and guidance. In the modern day, parks, schools, and memorials around Rhode Island are named in his honor.

Early Life & Migration

Roger Williams was born, probably in London, England, in 1603 CE, the son of a merchant, James Williams, and wife Alice. Records of his early life were lost in the Great Fire of London in 1666 CE. As a young man, he was educated first at Charterhouse School and then Cambridge University's Pembroke College where he mastered a number of languages including Dutch, French, Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. He was intensely interested in religious matters from a young age and studied to become an Anglican cleric. At Cambridge, however, he was drawn to Puritan theology and practice which would later set him at odds with the Anglican Church.

The Anglican Church, although founded in opposition to Catholicism, still retained a number of Catholic aspects in its organization, worship service, and beliefs. The Puritans were Anglicans who objected to any Catholic influences or observances in the Church and wished to 'purify' it, bringing it in line with the simple practices and beliefs of the first Christian community as depicted in the biblical Book of Acts. The more radical Puritans were known as separatists – those who felt the Anglican Church was wholly corrupted by Catholic influences and separated themselves from it completely – and, in time, Williams aligned himself with this theology and belief.

During his years at Cambridge, Williams was apprenticed to the famous jurist Sir Edward Coke (l. 1552-1634 CE), an independent and courageous thinker whose insistence on the concept of equality before the law brought him into conflict with the monarchy. Coke's unwavering stand for justice, as well as his practice of regularly speaking out against policies or even laws he considered unjust or inequitable, significantly influenced Williams' outlook and later actions.

The Anglican Church had replaced the pope with the English monarch as its head and so any criticism of the Church was considered treason against the crown. Throughout the reign of James I of England (1603-1625 CE), Puritans who voiced dissent were persecuted, fined, and jailed, some even executed, and under Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649 CE), these persecutions continued. Recognizing that England was no longer safe for an outspoken Puritan separatist, Williams left with his wife Mary in 1630 CE.

Continue reading...

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

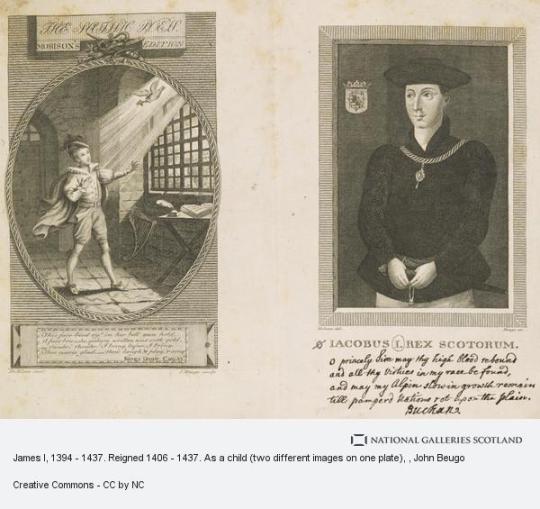

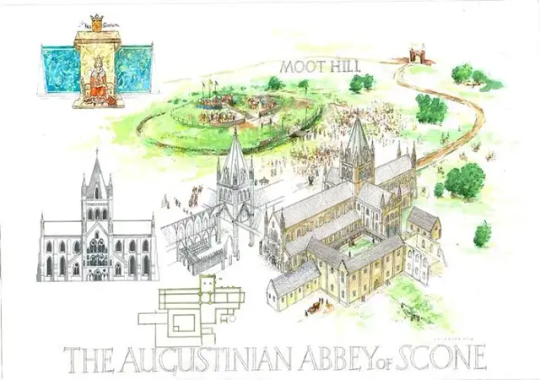

On 21st May 1424 James I was crowned King of Scots at Scone.

James I of Scotland was a complex and colourful king. He was a poet, a sportsman, a musician and a patron of architects.

James survived being kidnapped by pirates when he was just 12 years old - and the following 18 years he spent as a hostage to the Lancastrian kings of England.

In 1424, he made a triumphant return to Scotland and was crowned at Scone, but 13 years later he was brutally stabbed to death, his body dumped in the sewer below the Blackfriars monastery in Perth.

James Stewart was born in 1394, the third son of King Robert III and Annabella Drummond. By the time he was eight years old, he was their only surviving son. His brother Robert died in infancy and his other brother David, the Duke of Rothesay, died in suspicious circumstances at Falkland Castle while he was being detained by his uncle Robert, the Duke of Albany.

After David’s death, James was the heir to the Scottish throne, but he was also an impediment to the royal line being transferred to the Albany Stewarts. Fears grew for his safety and plans were made to send him to France.

In March 1406, he boarded a boat bound for France, but just days into the voyage, the vessel was intercepted in the English Channel by pirates who delivered him to Henry IV of England.

On 4th April 1406, Robert III died and the 12-year-old James was now the uncrowned King of Scots. But he was imprisoned in England and his uncle, the Duke of Albany, became regent in Scotland a position he had no intention of giving up.

James may have been a prisoner, but he was allowed to keep a small household and was treated well by Henry IV. This lasted until 1413 when Henry IV died, his son Henry V became king, and James was transferred to the Tower of London with other Scottish prisoners.

It took another seven years before James’ standing improved enough for him to be regarded more of a guest than a hostage - but it took a third change of monarch in England before James was finally allowed back to Scotland. Henry V died in 1422, and the regency council for the infant Henry VI were eager to organise his release as soon as possible.

Despite opposition from the Albany Stewarts, it was arranged for 1424 when he arrived triumphantly in Edinburgh on Palm Sunday, accompanied by his newly-wed English wife, Joan Beaufort.

Prominent members of the Albany Stewarts were found guilty of rebellion and executed, but a conspiracy against the King began to grow and he reigned for just 13 years before his death.

On 4th February 1437, the King and Queen were in their royal apartments at the Blackfriars monastery in Perth, when a group of about 30 people was let in by one of the conspirators against him. James was alerted and had enough time to hide in a sewer tunnel, but his exit was blocked and he was trapped and killed. He died in a pool of his own blood, stabbed dozens of times.

The assassin, Sir Robert Graham, is said to have screamed after his death: “I have thus slayne and delivered yow of so crewel a tyrant, the grettest enemye that Scottes or Scotland might have.”

James I was buried within the grounds of Perth Charterhouse, but the priory was destroyed in the reformation, now no-one is exactly sure where his grave is.

The last pic is a reconstruction of how the site at Scone may have looked.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

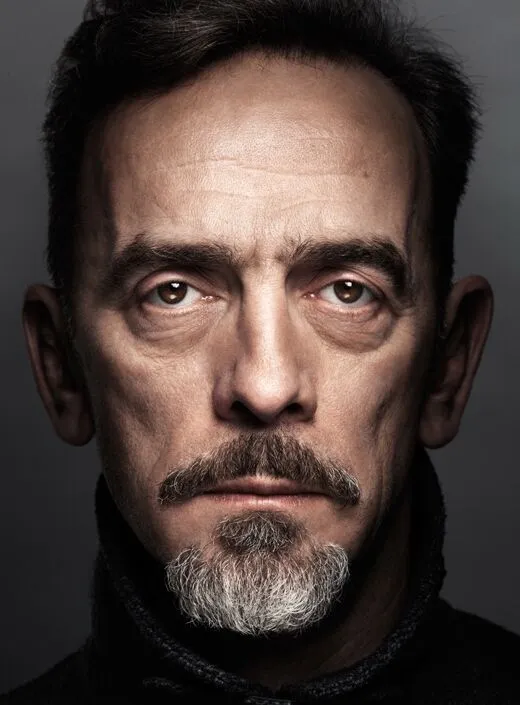

Towards the end of his life, the actor Adrian Schiller, who has died unexpectedly aged 60, found success and sudden fame in two blockbuster TV shows: The Last Kingdom (2018-22), on Netflix, in which he played the richest man in medieval Wessex, Aethelhelm; and ITV’s drama Victoria (2016-19), as Cornelius Penge, a footman in the royal household.

In both, a fleeting glance would suggest that here was a naturally authoritative actor, blessed with gravitas and style. This camouflaged the demonic comic spirit within, which had informed so many of his memorable stage performances since he first appeared in the German Expressionist Carl Sternheim’s 1911 play The Knickers at the Lyric, Hammersmith, in 1991. In a delicious comic performance, he played a weak-chested Wagner-loving barber thunderstruck by a flash of discarded lingerie as the Kaiser drove by, suggesting, said the Times critic, “a tousle-headed combination of Charlie Chaplin, Egon Schiele and Gollum, whose idea of romance is reading extracts from the Flying Dutchman”.

Schiller proceeded to leading roles with the Royal Shakespeare Company in the 1990s – his Porter in a disappointing 1996 Macbeth was the funniest I had ever seen, while his entertaining Touchstone in an awful 2000 designer knitwear production of As You Like It rescued another dud evening.

He was less prominent in some strange productions at the National – Peter Handke’s wordless The Hour We Knew Nothing of Each Other in 2008, as one of 27 actors playing 450 characters in a town square, coming and going with no interaction, and as a revolutionary tailor in a poor 2013 retread of Carl Zuckmayer’s 1931 Captain of Kopenick, in which Antony Sher did not eclipse memories of Paul Scofield in the NT’s 1971 production.

On the other hand, he was outstanding in Chekhov’s Three Sisters, superbly directed, and modernised, by Benedict Andrews at the Young Vic in 2012, playing Kulygin, a leather-jacketed schoolteacher tragically infatuated with his own disloyal wife; and he was a compelling, original, quietly spoken and sympathetic Shylock in The Merchant of Venice at the Wanamaker, the candle-lit indoor venue at Shakespeare’s Globe, in 2022. The Merchant rekindled the current noise around the play – is it antisemitic or about antisemitism?

In an interview with the Jewish Chronicle, Schiller tilted towards the second view. He averred that he was “a Jew, but not Jewish”.

Schiller was born in Oxford, the second of four children of Judith (nee Bennett), a teacher, and Klaus Schiller, a gastroenterologist whose family had emigrated from Austria to Britain in 1938. When Klaus was appointed a consultant at St Peter’s hospital, Chertsey, the Schillers moved to Surrey.

Adrian was educated at Kingston grammar school and Charterhouse, in Godalming, Surrey, where he pursued a busy life in stage productions. Instead of drama school, he took a good degree in philosophy (after switching from architecture) at University College London, although he always self-deprecatingly said that he majored in “plays and partying”.

His early television career encompassed series such as Prime Suspect, A Touch of Frost, Judge John Deed and much else, through to the first series of Endeavour in 2013. He also popped up in the Channel 4 series The Devil’s Whore (2008) set in the English civil war, and the Doctor Who story strand The Doctor’s Wife in 2011.

One of his most effective cameos on screen was as the barman in a striking government-sponsored advert in the anti-drink-driving campaign in 2007. He leaned deep into the camera with a series of non-equivocal questions to a bemused, unimpressed young glass-holding customer who may or may not have grasped the seriousness of the interrogation.

But he always returned to the theatre, seeking out the most demanding roles with companies who would accommodate him. He gave an almost ideal Cassius, wirily intellectual while bubbling passionately underneath, said Michael Billington, for David Farr’s 2005 RSC touring version of Julius Caesar. In the title role of Tartuffe at the Watermill, Newbury, in 2006, he was cool and venomous, as well as understated, and clearly the star of the show.

And for Stephen Unwin’s English Touring Theatre in 2007, he rebooted the remorseless villain, De Flores, in Middleton and Rowley’s Jacobean shocker, The Changeling. He was more than notable, too, opposite Sher’s Sigmund Freud, as a vividly hilarious Salvador Dalí, in their great encounter scene in Terry Johnson’s Hysteria at the Hampstead theatre, revived there in 2013, 20 years after its Royal Court premiere.

His feature film credits were not extensive, but in 2014 he was well cast as the sardonic high priest Caiaphas in Son of God, Christopher Spencer’s biblical epic. In Sarah Gavron’s Suffragette (2015), scripted by Abi Morgan, he was an imposing Lloyd George, coming round to the persuasion of the militant vote-seeking women led by Meryl Streep as Emmeline Pankhurst and Carey Mulligan as a fictional worker fuelled by the excitement of change and protest.

His last movie, yet to be released, is Red Sonja, in which he plays the king of Turan in a remake of the 1985 sword-and-sorcery Marvel Comics fantasy.

Back on stage in 2023, he returned to questions of Jewish identity and survival in three short new plays at the Soho theatre and a more substantial Holocaust drama, The White Factory by Dmitry Glukhovsky, at the sparky new Marylebone theatre (formerly the Steiner Hall), in which he was a powerful, wise presence in the story of a survivor of the Łódź ghetto in Poland, played by Mark Quartley, adapting to American life in the Brooklyn of the 60s.

At the time of his death, Schiller – who was also a skilled sculptor and guitarist – had just returned from Sydney and the triumphant international tour of The Lehman Trilogy, directed by Sam Mendes, and had been looking forward to the next leg of the tour in San Francisco.

He is survived by his partner, Milena Wlodkowska, a laboratory support technician, and their son, Gabriel, and by his sister, Ginny, and brothers, Nick and Ben.

🔔 Adrian Townsend Schiller, actor, born 21 February 1964; died 3 April 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saint of the Day – 4 August – Blessed William Horne O.Cart. (Died 1540) Martyr, Carthusian Lay Brother of the Charterhouse in London. William was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn Tree, London, for treason for refusing to accept King Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the Church. Additional Memorial – 4 May as one of the Carthusian Martyrs of London.

(via Saint of the Day – 4 August – Blessed William Horne O.Cart. (Died 1540) Martyr – AnaStpaul)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

28 February 2017 | Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh greet Almshouse residents as they open a new development at The Charterhouse at Charterhouse Square in London, England. (c) Chris Jackson - WPA Pool/Getty Images

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sam Birds 'CV' on his website circa 2002.

2002: Well, I really thought this would be my year - I wanted to win the JICA British title and start some European racing. However, with the new regulations and the restrictor, which favours smaller, lighter boys, it was not to be. I had some silly problems in the first race, which left me trailing the championship at 17th . However, a good place in the second race put me up to 6th. Bad luck dogged me, with a black flag for "weaving" and a couple of dnfs, so I stayed in 6th place. Some fantastic drives, through the field, earning me good publicity for the first time in a long while.

Went to Garda for first ever ICA race - wow! I love this. Came 2nd and 4th in heats and 4th in final.

Parma - again great results in practice and heats, but developed fever for race and finished 10th. Mind you, there were some 90+ entrants and I was the youngest!

Portugal. Qualified fourth in group. Set fastest lap in 2 heats. Sadly, didn't finish race but did enough to qualify for finals in Angerville. One of only four Brits to get through!

Did practice race in Spa, just to test engines ready for the final. Highest non=Belgian finisher by 11 positions. Finished third, almost photo finish with Thonon who went on to win European Championship!

European Championship. One DNF (shunted off) plus technical problems in two heats where I had to "nurse" kart home meant very poor qualifying position and didn't make finals. Started 15th in Federation Cup, had great drive and reliable kart this time, overtook almost one kart per lap, came in 5th.

Future: Hope to concentrate on practice for ICA in Europe/UK. This will be my route for next year and after that ……………

2001: After Common Entrance, I won a place at Charterhouse, in Godalming. Fabulous school and here they recognise karting as a sport and not just a hobby. Am on the short list for a sports scholarship. During this year I joined Ricky Flynn Motorsport and have learned a lot. Many technical problems, but also some very good results - have had a 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th in various heats/races.

2000: Still having problems persuading the school that I should be allowed to race on weekends. Could NEVER do Friday practice and had problems on Saturdays, because I was in every team for football, rugby, cricket, athletics and cross country! However, in 2000 I was joint winner of Buckmore Park Series and 2nd in winter series.

1999: After such success in Formula 6, rather a shock to enter Formula Junior Yamaha which was a leap too far. Many technical problems, plus my prep. School was unsupportive. However, see pic on this site of me ahead of di Resta - it really did happen once!

1997/8: Persuaded my parents to buy me a kart for 10th birthday present, but only used it very briefly, as I raced in Formula 6, courtesy of Sandown Karting. Won trophy almost every race. Novice trophies in first, second and third races, after that, always on podium. Once I had finished being a novice, very often came in half a lap ahead of the rest of the field.

1996/7: Still too tiny to buy a kart, so went indoor racing at Playscape in London. Won most races, even against instructors. Thanks Mike for your encouragement.

1995: Aged 8, had first lessons at Silverstone. Far too small to reach pedals but thoroughly enjoyed experience and couldn't wait to get back into a kart.

#sam bird#formula e#fe#mclaren fe#i genuinely cried at how cute this is#still to tiny to buy a kart#sobbing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Jesu: what will you do with my heart?’

I have always loved the writings of the Carthusians and have found them to be be both beautiful and challenging. But recently I came across a homily given on the occasion of a jubilee celebration of a priest's ordination. The homily focuses on the love and commitment of Carthusians martyred under the reign of Henry VIII, in particular St. John Houghton. It speaks not only of the beauty of the priesthood and the sacraments but also what God can accomplish in hearts open to His love and grace. It speaks of the grace that is both needed and offered when we are faced with the difficult challenges and choices of life, no matter what our particular vocation may be. The following is a rather lengthy excerpt from the homily (one that I found deeply encouraging) and I hope you enjoy it:

“The story of the Carthusian martyrs is not as well known as it should be. No doubt this is because, in the great tale of the early English Reformation, the figures of Sts John Fisher and Thomas More tower over all others, for many and obvious good reasons. And yet nobody becomes a martyr without some extraordinary qualities—tenacity, faith, holiness—that make it possible to face all the consequences of simply doing the right thing when it is required. And yet how difficult that simple thing can be, even in small matters.

The monks of the London Charterhouse (who provided most of today’s saints) were renowned for their holiness of life in the early sixteenth century. It had become fashionable to grumble about monks at that time, but nobody grumbled about them. Thomas More, who could be rather scathing about monks who were no holier than they should be, actually lived with the London Carthusians for several years, and contemplated joining them. Carthusian monks, following a somewhat different and stricter form of the Benedictine life, have as their proud boast that they have never needed reform. Theirs is, and always has been, a very silent and recollected life: The London community in the sixteenth century was led by Prior John Houghton, a relatively young man, already with a reputation for sanctity. You will understand, then, why Henry VIII was particularly keen to get him and his community on side. Being widely respected, they would lend authority to the King’s claims to the headship of the Church in England.

When presented with the King’s demands that the London Carthusians recognize his claim to the headship of the Church in England, the community took three days to pray about it, on the last of which they celebrated a Mass of the Holy Spirit. During Mass, at the elevation, the whole community actually had an experience together that they unanimously identified as the Holy Spirit breathing in the chapel, and which gave them courage for what was to come—courage they would sorely need.

John Houghton, together with two other priors from the North, went to speak to Thomas Cromwell, the King’s strong arm man in religious matters. We can be sure that with his lawyer’s training, St John tried everything to make it possible to take the oath of allegiance to the King, without, however, compromising principle. Nothing availed, however, and all three were arrested, the charge being that —and I quote — ‘John Houghton says that he cannot take the King, our Sovereign Lord to be Supreme Head of the Church of England afore the apostles of Christ’s Church’, which rather makes it sound as if the apostles had also usurped what was the King’s rightful position.

In any event, he was condemned, of course—Cromwell had had to threaten the jury with treason charges themselves in order to achieve it, and the three priors together with a Bridgettine priest and a secular priest were all dragged to execution together. St Thomas More, by now in the Tower of London, watched them from the window of his cell setting off, and commented to his daughter who was visiting that they looked just like bridegrooms going to their wedding, a comparison that St John Fisher was also to use on the morning of his own death.

King Henry was insistent that the priests should be executed in their religious habits, to teach other religious a lesson, one presumes. This meant that after St John was cut down from the gallows, still alive, to be butchered, the thick hairshirt he wore under his heavy habit had to be cut through by the executioner, who had to stab down hard with the knife. And then, finally, as the executioner drew out St John’s still beating heart before his face, he spoke his last words: ‘Good Jesu’ he said, ‘what will you do with my heart?’

‘Good Jesu, what will you do with my heart?’ These are words that can speak to us at any stage, indeed in any moment in life, because we are daily confronted with choices between good and evil, or even simply between good and better. These words place the element of choice firmly in the Lord’s loving providence, praying for his grace to help us make the right decision.

When it comes to lifetime choices, however, St John Houghton’s words become more eloquent. There are any number of ways one can give ones life for the Lord—martyrdom is only one, albeit just about the best. One can also give ones living life for Him, by living in the married state, by working in any number of vocations in the world, and, of course, by spending ones life in consecrated religious life and/or the Priesthood. I think that the key element that identifies when a job becomes a vocation is when there is an element of self-giving to it—or in other words, when there is at least an element of martyrdom.

I have always been very struck by the story of Blessed Noel Pinot, a martyr of the French Revolution, who, having been arrested when about to celebrate Mass, ascended the scaffold to the guillotine dressed in the same Mass vestments, reciting to himself the same words we said today ‘Introibo ad altare Dei’. The mother of St John Bosco said to him on his ordination day; ‘remember, son, that beginning to say Mass means beginning to suffer’. These words come home to me and strike at my conscience, but I increasingly think that I can never really be worthy of my priesthood until I pour myself more entirely into it. There is nothing worth having that does not carry its price label, and the price label for following the Lord is imitating him in all things or, as He said Himself, taking up our cross daily. The question is not what do I want (the answer to that is straightforward: I’ll have an easy life, please, involving some nice dinners in agreeable company) but what does He want. In fact, ‘Good Jesu, what will you do with my heart?’ Because whereas my little wants are rather petty and contemptible, his are wonderful beyond comprehension. And very often beyond my comprehension, anyway.

Thanks be to God that the priesthood of God’s Church does not belong to me but to Christ, that I do not exercise it, but he exercises it through me. Thanks be to God that the sacraments we offer do not depend on our worthiness but on His.

What a wonder it is that the Lord loves us at all! And yet he does, and is happy with the feeble struggle and great labour we make of bearing his sweet and gentle yoke, he rejoices as a parent does when guiding the first steps of a child or when speaking his first words. Caused by grace, these shallow twitches in our lives towards doing the Lord’s will and setting aside our own desires are no matters of mere jubilees and quarter centuries, they are the stuff of eternity leaking into time. These things are signs of the Kingdom of God, where, in eternity, eye has not seen nor ear heard what good things God prepares for those who love him. Which is why we pray with St John Houghton: ‘Good Jesu: what will you do with my heart?’”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research trip to Mount Grace Priory

An old interest in monks has resurfaced. I studied Carthusians once upon a time (their manuscripts, really). The interest flares up now and again. This meant that a visit I'd long put off was back on the cards. Drove down to Northallerton in North Yorkshire on Sunday to see the ruin of Mount Grace Priory.

Mountgrace was founded in 1398 by Thomas de Holand, a nephew of Richard II. Carthusians and their brand of piety was super-fashionable at the time (due to the strictness of their Rule and a general post-Black Death rethink) but having a founder connected to Richard II became a problem. In 1415, it was re-founded by Thomas Beaufort. Mountgrace only lasted until 1539, when the Suppression of the monasteries kicked in.

I was keen to look at the reconstructed monk's cell.

I took lots of photos.

Lots.

Here's a few.

View of the church and bell tower

Entering the monk's cell

Laybrothers cooked the food, were responsible for upkeep and general day-to-day activities under the watch of the Procurator. (Laybrothering was a prestigious position. A few bishops retired to take up the job.) Among lots of other jobs, they would deliver food into hatches like this so the monks wouldn't have to interact.

Straight ahead is the living quarters. The fireplace in this cell is smaller than the one found in the sacrist's cell.

Desk by the windows. Lots of natural light.

A place to rest yourself and your reading materials

A place to rest yourself (the Carthusian schedule is brutal).

If you turn left, there's a nice glazed, private cloister looking out onto the cell garden.

If you turn right at the entrance, a covered walkway leads to the garden, freshwater drinking pipe and latrine (both plumbed in. Monastery plumbing was something else. I've seen the plans for London Charterhouse).

More garden! Small fruit tree and exterior view of the glazed private cloister.

Exterior view of the cell from the garden.

Let's go back inside and go upstairs! (These stairs really are steep. Believe the sign next to the fireplace. You have to come down backwards.)

Upstairs, we find the workshop! Spinning, weaving, copying books, woodwork, lots of useful activity.

Once that bell rings, you've got to go to church. A huge covered cloister once connected all those doorways and led to the church.

Can't remember if this is the church or chapter house I'm standing in.

Would've been a lovely window here, I bet.

The guest house was in better condition, mainly because Sir Lowthian Bell decided to restore it (and reconstruct the monk's cell). Here it is from the gardens.

There's still some original red plasterwork from the 14th century.

There's a decent museum in the guest house too. If you're into the Arts and Crafts movement, there's some Morris and Co. wallpaper and furniture, plus a couple of restored rooms. I liked this 14th century stone window looking into an Arts and Crafts lounge.

A pretty good day's research! Definitely recommend the place. Absolutely worth the trip.

#research#carthusians#mount grace priory#mountgrace charterhouse#carthusian#14th century#ruins#old ruins#late medieval#monks#arts and crafts#history#reformation#dissolution of the monasteries#charterhouse

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cherry blossoms in Charterhouse Square, London

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morbid little fact added into Chapter 15 while doing some more work on it.

Francis Osman observed all this with visceral wonderment. He had arrived at Crossrail and passed through Barbican market to collect his own newspaper before heading north to the square just outside London's walls where the old monastery turned hospital reside in its old, archaic arches. What how Charterhouse got its name when the Carthusian monasteries was an Anglicisation of *La Grande Chartreuse*, whose order founded the monastery and was converted to the boy's school now endowed hospital in 1677.

Yet much more dark history was here surrounding London's mecca of homicide, death and disease, what ironically formed a place now meant to heal and educate healing. It was something Francis didn't miss the irony of as he crossed over the freshly manicured greenery of the courtyard knowing what held below his feet as he paused to scan the grounds. Just barely covered by earth, like Hieronymus Bosch's damned cast into hell, was a burial pit what's mouth covered the two acres with tangled bodies packed to capacity from disease due to the notorious black death epidemic that wiped out almost all of Europe in the 1300s.

Now, the square was filled with life as people go about their day oblivious in their repetition, enjoying the sunshine and small green spaces dotted all about as the bells of nearby St. Bartholomew's toll over the city like a haunting echo. It was like a reminder that despite its industrialization and means of advancement, London was still a treacherous place baroque of death and disease for multifarious reasons. All just barely hidden below the veneer surface of a modern civilization...

#of course Francis would know this#please don't tell Ebenezer about this while standing over it.#there's over 50 thousand bodies packed below your feet rn like a morbid sistine chapel#“Why tell me this. I want to go home now...”#scroogeposting#scrooge fanfiction#oc francis osman

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINTS SEPTEMBER 20 "There is only one tragedy in this life, not to have been a saint."- Leon Bloy

Bl. Thomas Johnson, 1537 A.D. English Carthusian Martyr. A priest and member of the London Charterhouse, he was arrested with fellow monks for opposing the claim by King Henry VIII of spiritual supremacy over the English Church. Imprisoned at Newgate, Thomas was starved to death.

St. Fausta and Evilasius, Martyrs at Cyzicum, in Pontus. Fausta, a girl of thirteen, was tortured by her judge, Evilasius. Her courage converted him, and he died with her. Sept. 20

St. Eustace, Roman Catholic Martyr with Theophistes, Agapitus, and Theophistus. Eustace was a Roman military officer called Placida, When he refused to take part in the pagan ceremony and they were roasted to death. Sept. 20

St. John Charles Cornay, Martyr of Vietnam. He was born in Loudon, Poitiers, France. and joined the Paris Society of Foreign Missions. Sent to Vietnam he worked there until his arrest after being denounced as a Christian by a bandit. He was kept in a cage for months and subjected to hideous cruelties before being beheaded. Feastday Sept 20

St. Eusebia, Roman Catholic Benedictine abbess and Martyrs, slain with her community by the Muslim Saracens at Saint-Cyr, France. Forty nuns died with Eusebia. Feastday Sept. 20

St. Lawrence Imbert, Bishop and martyr of Korea. Lawrence was born in France and was a member of the Paris Society of Missions. He was tortured to death with Sts. Peter Maubant, James Chastan, and companions. Sept. 20

STS. ANDREW KIM TAEGO˘N, PAUL CHÔNG HASANG AND COMPANIONS, KOREAN MARTYRS Martyrs of Korea, The men and women who were slain because they refused to deny Christ in the nation of Korea. At least 8,000 adherents to the faith were killed during this period.

St. Agapitus I, Pope from 535-536 and apologist, the son of a priest named Gordianus slain during the reign of Pope Symmachus. He was elected pope on May 13, 535, and was already of an advanced age as he started healing the rifts in the Church by regulating affairs. Sept. 20

0 notes

Text

The Weight of Tradition: Moving Stones at Charterhouse

In retrospect this seems to be an architectural tradition of Gownboys.

The School moved to Godalming in 1872, bringing traditional Charterhouse names, traditions and memorabilia from the London Charterhouse. The pupils of Gownboys House loved the historic entrance to the old Gownboys so much that they dismantled it, stone by stone, and reconstructed it in Godalming, built into a wall that leads nowhere. You will find the archway in ‘The Temple of the Four Winds’ (6) in the South-East corner of Founder’s Court.

#Charterhouse #BoardingSchool #ArchitecturalTradition #SchoolPunishments #Gownboys #Godalming #HistoricalLegacy #SchoolTraditions #Education #BritishSchools #Granite #Lutyens #Memories #StudentLife #FoundersCourt

0 notes

Text

On 15th July 1445 Joan Beaufort, queen consort of King James I died.

Joan Beaufort was the daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Sommerset (and grandson tof King Edward III of England) and Margaret Holland (daughter of Thomas Holland, 2nd Earl of Kent who's mother was also the mother of King Richard II of England). Joan was also half-niece of King Henry IV of England. Royal credentials aplenty, and the ideal candidate to put forward for a marriage to a future King, except unlike most Royal marriages of medieval era, Joan and James was a real bona fide love affair.

James met Joan while he was a prisoner in England and knew her from at least 1420, he wrote a poem, allegedly inspired as he saw Joan through the window while Joan was in the garden; the poem was called "The Kingis Quair".

Although James may have been taken with Joan, their wedding was at least partially politically motivated as their union would strengthen relations between Scotland and England, rather than allow a stronger alliance between the Scots and French.

On February 12, 1424, King James and Joan were wed at St. Mary Overie Church in Southwark, London. Joan returned to Scotland with her new husband and after 18 years being held at the English court, he had scores to settle, it is said that Joan, as Queen, often pleaded with the King on behalf of those to be executed.

The King and Queen had 8 children together, all but one lived into their adulthood, a remarkable achievement for the times.

On February 21, 1437, King James I was assassinated in Perth by Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl. Joan, who was with her husband at the time, had also been targetted for assassination but she managed to escape with injuries. Although Joan identified the Earl of Atholl as the assassin, and successfully encouraged her supporters to attack him, she had to give up power 3 months later due to the unpopularity of Joan being English, and the Scots did not want an Englishwoman as ruler. Subsequently the Earl of Douglas was appointed to power although Joan maintained control of her son, James II, the King of Scotland.

In late July, 1439, Joan married James Stewart, The Black Knight of Lorn who was an ally of the latest Earl of Douglas, and plotted with him to overthrow Alexander Livingston, governor of Stirling Castle, during the minority of James II.

Livingston arrested Joan in August 1439 and forced her to relinquish custody of the young king. In 1445, the conflict between the Douglas/Livingston faction and the queen's supporters resumed, and she was under siege at Dunbar Castle by the Earl of Douglas when she died on 15 July 1445. She was buried in the Carthusian Priory at Perth,called the Charterhouse, it has completely disappeared, there were articles in February 2017 about a search for the graves of the King and Queen, I have not heard if it is continuing.

18 notes

·

View notes