#Not claiming it is a utopia in those places for disabled people but they can speak for themselves

Text

I saw a post about someones plans for after the revolution, and I’m begging leftist to get serious for 5 minutes.

Y’all talk about and predict a revolution with the same reliability and trustworthiness as evangelicals talk about armageddon.

US Leftist can’t keep their shit together enough to wear masks and to help poor people get masks because they are expensive. But sure a revolution is going to happen any day now.

In the US many disabled people like myself are now homebound because we can’t safely go outside. Abled leftist admittedly refuse to do anything to change that. They are to busy posting quotes from long dead white men, about ideas those dead white men stole from indigenous peoples.

If US leftist can’t cope with something like covid, how the fuck do you expect to pull off a revolution?

#cripple punk#cripplepunk#us politics#us leftism#anarchist#socialism#ableism#disability rights#I'm centering the US because our health care system makes the response to covid different then countries were people just go to the doctor#when they are sick and have workers rights so they can stay home#Not claiming it is a utopia in those places for disabled people but they can speak for themselves#yeah my icon is kind of funny in context . . .hmm maybe should change it

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw someone earlier say that the popular millennial/early gen Z reaction to AI tech is very comparable to Gen X-ish's reactions to GMOs, and...I can no longer find that post but I can't help but feel that to be true on a lot of levels.

As stated in that post, both technologies have their very legitimate problems - with GMOs, it's Monsanto being fucking evil and trying to monopolize plants and food, or GMO herbicide resistance being used so that major corporate farms can saturate the land with said herbicides without any short-term financial damage to the companies as if it doesn't harm the environment; with AI, it's any form of automation always appealing to the most abusive of corporate greed - but both ended up whipped into a dogmatic fervor about something completely not only irrelevant but made-up and reactionary ("GMOs are all POISON, nature knows best ALWAYS!" - which led semi-directly to the antivaxx movement btw / "it doesn't matter how different it is from the input taking inspiration from existing works the WRONG way is PLAGIARISM, you're rewarding LAZINESS, and REAL ART vs. FAKE ART is totally an objective distinction that can be made and certainly not at all a fascist talking point, and I want art made by HUMANS, the humans running these programs to express something from their human brains don't count!"), completely ignoring that GMOs have reduced world hunger and given us valuable conservation tools, and AI is giving people - real people, not machines - more expressive capacity, serving as a valuable research tool into what kinds of things people tend to associate, justly or otherwise; and even being used to augment human judgment for things such as reviewing biopsy results, finding cancers that otherwise may have gone unnoticed for months or even years longer. In fact, many opponents will full on deny any of these benefits - "what good does reducing hunger do if we haven't eliminated it completely AND we're feeding people POISON? In fact, why should I even believe that really happened in the first place!? if you wanted laypeople to be able to read these studies you wouldn't have made them so complicated, you CLEARLY have something to hide!" the anti-GMO warrior asks; "I don't believe those people who are so severely disabled that they couldn't draw or write without AI REALLY exist, your meditation on the nature of data doesn't COUNT, I don't care how many hours you spent on that piece you're TOTALLY being lazy, and I refuse to believe anyone who points out that it's not a copy-paste machine because you CLEARLY have an AGENDA to lie" the anti-AI reactionary claims. Both hold to a belief that ignorance is a virtue, and even TRYING to understand the Bad Side is tantamount to shoving orphans into a wood chipper.

But I'd take it a step further and say that AI is serving a similar sociopolitical purpose in that it's drawing a line in the sand and asking progressives at a certain stage in life - mostly from the ages of 25-35 - "are you willing to acknowledge nuance around subjects that are new and scary to you, or are you going to give into that fear and treat ignorance as a virtue because there ARE undeniably bad things about this and therefore EVERY bad thing you can imagine about it must be true?" Both serve as, essentially, an acid test - will you declare that it's IMPOSSIBLE to be reckless with GMOs, that Monsanto DESERVES to have sole control over the world's food supply because ~they've done so much good~, or that all GMOs are EVIL POISON and GOING TO KILL US ALL and they're also TOTALLY the reason we're all FAT now which is THE WORST thing a person can be? Or are you going to acknowledge that Monsanto is fucking evil, but GMOs as a whole are a complex thing that can, indeed, be created and marketed in some pretty evil ways, but also have the potential to save countless lives? Will you declare that AI is True Sentient AI, the cyber-utopia becoming real; that everything ChatGPT says must be true and OpenAI is our best friend, or that REAL art by HUMANS is going to be destroyed forever and anyone who benefits from AI is inherently evil? Or will you acknowledge that AI, while it has its drawbacks in the form of corporate overpromising people and compromising information reliability by doing so, on top of the perennial labor issues that come with automation and other potential abuses, also has the capacity to dramatically improve and even potentially save lives? Will you work to save the good WHILE rejecting the bad, or will you insist it needs to be shoved in either the good box or the bad box - probably the bad box, if you're an adult?

The answer, I feel, says a lot about the ideological trajectory someone has chosen for their adulthood.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stop saying that “Miscarriage is just nature handling disabled babies.” THAT’S NOT HOW IT WORKS.

Yes, there are genetic factors that may contribute to the cause of a miscarriage. HOWEVER, miscarriage is NOT a function from “““nature”““ to kill off disabled babies for our abled-bodied utopia. I will go over the genetic factors later in this post, but I will also cover lesser known but still very common causes of miscarriage and other complications as well.

1. Hormonal imbalances. Two common causes of a hormonally imbalanced miscarriage include low progesterone and thyroid dysfunction. Progesterone is the hormone produced by the ovaries after ovulation, and it continues to be produced after the baby implants; after implantation, the growing placenta will help the ovaries in producing the high levels needed to maintain the pregnancy. If for whatever reason those levels are too low, it could cause a miscarriage or premature birth. Thyroid dysfunction is also a prominent cause, not only because such problems are already under-diagnosed in modern women, but also because the hormones it produces affects function in the reproductive system.

2. Pathological issues with organs. For example, the uterus may have too thin of a lining (made of tissue and blood, which needs to be thick enough to allow implantation to occur and be maintained), or the cervix may be “weak” and dilate far too early for the baby to survive labor. If there is a growth in the uterus, it could also cause growth restriction for the embryo or fetus. Some pathological problems are treatable through medical intervention.

3. Environmental factors. Drug abuse (including drinking and smoking), heavy pollution, exposure to dangerous chemicals, and other factors can all increase risk of miscarriage. Some women could lose their baby after starting up a new intense physical routine or becoming physically harmed through things like car accidents. These things can also cause dysfunction in the reproductive system for both men and women, which in turn can create problems should a pregnancy occur.

4. Chronic stress and/or systemic oppression. WOC are more likely to miscarry, experience stillbirth, and preterm birth than their white counterparts, due to inadequate care and medical neglect as caused by systemic racism. There is also a chronic stress they face every day for being a POC, that adds up with each consecutive baby. Similar things can be said for the disabled, LGBT, and other targeted groups. As a whole, women often find that their voices are not heard and respected by their care providers, which can result in them not getting the care they need in time or not getting any at all. Domestic abuse can also cause a miscarriage if the woman is physically abused; and while they are technically not a miscarriage in the traditional sense, domestic violence can also lead to forced abortions of wanted pregnancies.

5. And finally: Genetic problems. But not in the way that you think.

Before ovulation, egg cells in the ovaries must undergo a delicate process of cell division in order to ovulate, successfully conceive a new baby with a healthy sperm cell, and also grow and implant successfully for a full term pregnancy. If the cell divisions are not properly handled by either the sperm or the egg, then at conception you may end up with a zygote that can’t continue growing and dies; or with an embryo that can’t implant and dies; or with an embryo that is unable to grow after implantation and dies. These genetic malformations are enough of a problem to prevent cellular and bodily growth.

However, sometimes these genetic abnormalities are not an issue concerning gestational growth and survival. Instead, they affect other bodily functions (such as a missing chromosome or an extra one), and while they do come with their own complications pre or post birth, they do not prevent the baby from otherwise developing past implantation. It is those babies that may make it to birth and have some chance of survival, depending on their access to proper medical or hospice care.

If it were true that miscarriage were Mother Nature’s way of handling disabled babies, she’s not only really bad at her job: she’s a raging ableist. While people may claim such a thing to ease the pain of loss, the truth is that it typically hurts the parents, and it also perpetrates negative stereotypes and attitudes about the disabled community. And even without genetic-caused disabilities, there are people who become disabled after birth due to illness or accidents. Nature doesn’t “take care of disabled babies” anymore than Nature “takes care of disabled adults.” People who aren’t assholes support each other, and this attitude has been practiced in many societies over the course of human history.

Disabled people will always exist in one form or another, and we should not sit here and pretend that they don’t have a place among the rest of humankind. Grieving parents of pregnancy loss will still end up miscarrying even if everything was perfect, because there is so much we are still learning about reproductive and prenatal health. It costs us nothing to accept both of these truths and share some compassion among those suffering from loss.

#miscarriage tw#pregnancy loss tw#stillbirth tw#preterm birth#pregnancy complications#ableism#racism#sexism

177 notes

·

View notes

Link

I think one of the major problems with the modern left is a focus on cultural analysis instead of economics. When I say culture I EXPLICITLY DON'T MEAN racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, and Indigenous rights/decolonization.

Stupidpol and their ilk are reactionaries and should be treated as such. What I'm talking about is the focus on things like analyzing TV shows or picking over the latest issues of the NYT op-ed column, the sort a caricatures you see on Chapo.

Zizek is emblematic of this syndrome. He's a theorist of ideology, a film critic, a Lacanian psychoanalyst and complete reactionary on gender and immigration issues, and he's widely considered to be one of preeminent Marxist scholars alive. And, and this is important, Zizek does fuck all actual economic material analysis. Mark Fisher, who was an excellent Marxist theorist, covers almost exactly the same ground from a different perspective, and you can repeat this across academia.

Inside academia the problem has gotten so bad that the best economic analysis is being carried out by the fucking post-humanists. Take, for example, Anna Tsing's excellent Supply Chains and the Human Condition. Tsing is a brilliant theorist but she spends most of her time writing about multi-species interactions between humans and mushrooms. Carbon Democracy, one of the best theories of the carbon economy ever written, is by a left-Foucaldian.

There are some exceptions to this, Andreas Malm's Carbon Capital is wonderful, Riot Strike Riot is great and I have to mention the group I call The Other Chicago School, Endnotes, whose infrequent analysis is a breath of fresh air. But Endnotes isn't particularly well read even inside the academy, which takes back outside the ivory tower in the dismal mess that is what passes for popular left "economics."

I want to go back to Occupy for a second because what happened there is indicative of the problem. Occupy, at least technically, actually had a theory of economics that went beyond "neoliberalism bad, welfare state good." And it's really not as bad as its critics have since accused it of being. Graeber's "the 1% meme" was supposed to be part of an MMT analysis of the ability of banks to create money out of nothing, see Richard A. Werner. The theory then goes with the ability to create money out of nothing the question becomes who should actually have that power. The 1% are the people who control that power and use that it to gain wealth and their wealth to gain power.

This is essentially what happened after 2008 and it relates to an entire analysis of the politics of debt and war that's captured really well in the last chapter of Debt, The First 5000 Years, drawing from Hudson's excellent Super Imperialism. Again, not bad, and not the disaster it became in Liberal hands. But note two things:

1, His work is intentionally detached from the production process- Graeber uses a value theory of labor about the social reproduction of human beings. That theory is really interesting and I'll leave a link to his It is Value that Brings Universes into Being here. But Graeber is an anthropologist, not an economist, and his recent work is mostly composed of a set of theories of bureaucracy.

And, don't get me wrong, I really like Utopia of Rules and Bullshit Jobs, and it's possible to build an economic theory out of them, but almost no one actually does. And this gets us back to my second point about Occupy and economics.

2, Not a single other person I have ever met, including people who were in Occupy, have ever actually heard the theory behind the 1%. Part of this has to do with Graeber’s rather admirable desire to not become an intellectual vanguardist. But, I cannot overemphasize how much of this is a result of the left's retreat into an analysis of consumerism instead of capitalism and its further insistence that the entire fucking global economy can be explained by chapters 1-3 of Capital and this just isn't a "read more theory" rant, it's not like reading the rest of Capital is going to help you here. But even that's better than what's actually happened, which is people reading Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism and the Communist Manifesto and trying to derive economic theory from that, or getting lost in a Gramscian or psychoanalytic miasma trying to explain why revolution didn't happen. But we can't keep fucking doing this.

If we do we're just going to keep getting stuck in endless fucking inane arguments, one of which is about which countries are Imperialist or not based on trying to read the minds of world leaders, and the other of which is a bunch of racists trying to argue that they're actually "class-first" Marxists and that if we don't say slurs and be mean to disabled people we're going to lose the "real working class," which is somehow composed only of construction workers banging steel bars.

So let's stop letting them do that. One of the reasons Supply Chains and the Human Condition is so great is that it describes how the performance of gender and racial roles creates the self super-exploitation at the heart of global capitalism. Race and gender cannot be ignored in favor of some kind of "class-first" faux-leftist bullshit. THEY ARE LITERALLY THE DRIVER OF CAPITAL ACCUMULATION.

Most of the global supply chain has been transformed into entrepreneurs and wannabe entrepreneurs (see the countless accounts of Chinese garment factory workers who dream of getting into the fashion industry and who attempt to supplement their meager income by setting up stalls in local marketplaces to sell watches and clothes).

The fact that global supply chains have reverted to the kind of small family firms that Marx and Engels thought would disappear is a MASSIVE problem for any kind of global workers movement, because it means that the normal wage relation that is supposed to form the basis of the proletariat isn't actually the governing social experience of a large swath of what should be the proletariat, either because they're the owners of small firms contracted by larger firms like Nike who would, in an older period of capitalism, have just been workers or because the people who work for those firms are incapable of actually demanding wage increases from the capitalists because they're separated by a layer from the firms who control real capital, and thus are essentially unable to make the kind of wage demands that would normally constitute class consciousness because the contractors they work for really don't have any money. These contractors are in no way independent.

Multinational corporations set everything from their buying prices to their labor conditions to what their workers say to lie to labor inspectors. The effect of replacing much of the proletariat with micro-entrepreneurs is devastating.

The class-for-itself that's supposed to serve as the basis of social revolution has decomposed entirely. Endnotes has a great analysis of how this happened covering more time, but the unified working class is dead. In its place have come a series of incoherent struggles: The Arab Spring, the Movement of the Squares, the current wave of revolutions and riots stretching from Sudan to Peru to Puerto Rico- all of them share an economic basis translated into demands on the state. We see housing struggles, anti-police riots, occupations, climate strikes, and a thousand other forms of struggle that don't seem to cohere into a traditional social revolution and WE HAVE NO ANSWER.

I don't have one either, but we're not going to get out of this mess by trying to read the tea leaves of the CCP or analyzing how Endgame is the ruling class inculcating us into accepting Malthusian Ecofascism.

I want to emphasize YOU DON'T NEED TO SHARE MY ECONOMIC ANALYSIS to develop one, I'm obviously wrong on a lot of things and so is everyone else. The point is that we need to start somewhere.

There are other benefits to reading economics stuff even if it can be boring sometimes, like being able to dunk on nerd shitlibs and reactionaries who do the "take Econ-101" meme by being able to prove that their entire discipline is bunk. Steve Keen's Debunking Economics is absolutely hilarious for this, he literally proves that perfect competition relies on the same math that you use to "prove" that the earth is flat.

Or learning that the notion that markets distribute goods optimally is based on the assumption that what is basically a form of fucking state socialism exists, and that the supply demand curve is fucking bullshit. Here's a page from Debunking Economics looking at the socialism claim, it fucking rules, and it's the result of the fact that neo-classical economics and central planning were developed together. Kantorovich and Koopmans shared a Nobel Prize.

But wait, there's more! We can PROVE that THE MARKET PLACE OF IDEAS DOESN'T EXIST. Do you have any idea how hard you can own libs with facts and logic if you can demonstrate that THE MARKET PLACE OF IDEAS DOESN'T EXIST?

But seriously, if you go outside of the Marxist tradition there are all sorts of fun and useful things you can find in post-Keyensian circles and so on and so forth. I'm a huge fan of Karen Ho's Liquidated, an Ethnography of Wall Street/Liquidated_%20An%20Ethnography%20of%20Wall%20Street%20-%20Karen%20Ho.pdf) which looks at how the people at banks and investment firms actually behave and, oh boy, is it bad news (they're literally incapable of making long-term decisions which is wonderful in the face of climate change).

Oh, and also, all of the bankers are essentially indoctrinated into thinking they're the smartest people in the world, so that's fun.

This may sound like I'm shitting on Marxism, and I sort of am, but there's Marxist stuff coming out that I absolutely love! @chuangcn is a good example of what I think the benchmark for leftist economics and historical analysis should be.

Chuang responded to the call put out by Endnotes to cut "The Red Thread of History," or essentially to stop fucking arguing about 1917, 1936, 1968 and so forth and look at material conditions instead of trying to find our favorite faction and accuse literally everyone else of betraying the revolution, and then imagining what we would have done in their shoes. The present is different from the past and we need to organize for this economic and social reality, not 1917's.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EBvBIVhXYAYlVfj.png

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EBvBM3CXoAA7Qmx.jpg

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EBvBP0SWkAEl6OX.jpg

Chuang produced an incredibly statically and sociologically detailed account of the Chinese socialist period in issue 1 and the transition to capitalism in the soon to be put online issue 2 that focuses on shifts in production and investment and shifts in China's class-structure and how urban workers, peasants, factory mangers, technicians, and cadre members reacted to those movements and shaped each others decisions and mobilizations. They largely avoid discussions of factional battles of the upper level of the CCP, which dominate liberal and communist accounts of the period and produce, in supposed communists from David Harvey to Ajit Singh, a Great Man theory of history.

Instead, they trace how strikes and peasant protests shaped the CCP's decision making and how the choices of people like Mao and Deng Xiaoping were limited by material conditions, in this case by their production bottleneck.

What's great about Chuang is that their work is so rich in sociological detail that you don't need to agree with them at all about what communism is and so on for their account to be useful, and they force us to think about the world from the perspective of competing classes bound by economic reality, instead of the black-and-white "good state/bad state," "good ruler/bad ruler," discourse that dominates our understanding of both imperialism and the global economy.

I'm just going to end this with a TL;DR: Cut the read thread of history and stop fucking arguing about 1917, use economic theory to dunk on Stupidpol and shitlibs. When you talk about "material conditions" talk about the production process, supply chains, capital movements and so on, not which states are good and bad (the bourgeoisie is a global class friends), recognize that strategies need to be built around current economic and social conditions, WHICH ARE INSEPARABLE FROM RACE AND GENDER, climate change is more complicated than the 100 companies meme (I only touched on this but please read Fossil Capital and Carbon Democracy), and in general try to learn more about different schools of economics and social theory, I swear reading something that wasn't written in 1848 isn't going to kill you.

599 notes

·

View notes

Note

when you say a white writer has no business writing a POC, do you mean due to our world's inequality issues, or under absolutely any circumstances? e.g if there was a fiction AU world where there was no differences between the races whatsoever and never had been, would you apply it to that as well?

You know. I sat back and thought about this, and TL;DR my answer is those two reasons are inextricably linked. White creators have no business writing POC in stories because of our world’s inequality issues and because their liberty in doing so is won after centuries of international, settler-colonial genocide and abuse.

And I’m just gonna have this out in the open: one of my characters in my fiction is a Black woman. I do not talk about this with the presumption that I exist outside of this situation. I also know that we as fandom creators make characters of different races and ethnicities all day, every day. My critique here is with the industry, the flow of economic and social capitol that functions to privilege whiteness, neurotypicality, heternormativity, etc. I don’t get paid to write Naomi, and I don’t get industry clout for writing her in my fanfic as a character. I still try my best to consider how her world could be shaped and how her life happens with all facets of her identity configured, but I never ever claim nor want to claim that my writing her is an organic meditation on racism through a closed read.

CW: racism, settler-colonialism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia.

Here’s the thing – universes and worlds are places of endlesspossibility, right? But if we are talking worlds with societies, cultures, andother staples of anthrocentric environments, a utopia is inherently paradoxical.You cannot have a world of groups, societies, and governments without identitiescoalescing and diverging from one another in both interest and history. No matterwhat, whether it be on the basis of skin color, origins, traditions, norms,values, ambitions, social organization will manifest itself.

And here’s another thing: 99.99% of the time in games, movies, tvshows, utopian worlds where race, class, gender, and sexuality are “unimportant”is a half-assed narrative style. Why? Because we don’t know what that actually lookslike without getting our perspectives and experiences on them like muddyfingerprints. If we’re simply talking Dragon Age, and specifically Inquisition,we have one Codex entry – “Sexuality in Thedas” – that discusses sexualidentity in several different cultures as being more behavioral quirk than anything.And yet:

1. Dorian is threatenedwith blood magic as a form of identity conversion therapy,

2. Cassandra objects toromance with a F!Inquisitor due to her gender and her faithful morality, and

3. We see social stressorstake place wherein people who are LGBTQ+ are seen as philandering, sexuallypromiscuous, etc.

It is a similar botching when it comes to race, because eventhough skin color isn’t supposed to be theoretically consequential, Vivienne isfaced with misogynoir that gets violent from the Imperial Court, and Elves areoppressed by virtue of their race.

Creating fictional worlds where identities marked by skin color, anatomy,economic class, etc. is nice to think about because it removes the stress ofhaving to construct and reckon with the violences of inequality. And who doesthat most benefit? White people of Anglo-European descent. It is no surprisethat in media industries unjustly dominated by white, cisgender, heterosexualmen, utopianism is an uncritical broad-brush tool used in narrative to removeresponsibility for the creators to flesh out and consider alternative perspectivesoutside their positionalities.

These worlds, these narratives, come from us, and we are in thisworld. This planet, wherein colonial white supremacist genocide has wreaked havocglobally for centuries and continues to do so. I don’t care if Steve Stevenson fromGlendale, CA with his Prius and polo shirts can write his pants off for acharacter who “just happens” to be a person of color. The fact is and willalways be that he gets money deposited into his bank account for it that couldhave gone to a Creative of Color to write, construct, design, illustrate, etc.instead of him.

More often than not, Utopian AUs are the playgrounds of privilege.We dissect this in social theory and ethnic studies, how the concept of a “Utopia”presents itself as disconnected from past and futurity, suspended inegalitarian stasis. It proposes a place where generationally inherited anger, poverty,abuse, cultural erasure, etc. have no bearing on the community or the individuals’identities. Who has the most to benefit from that? Who has the most to benefitfrom subjugated identities not having reason nor evidence to thedisorientation, persecution, and estrangement they feel from the body politic?

So, no, I don’t think white creators have any business writingcharacters of color. I don’t think cishet creators have any business writing LGBTQ+characters. I don’t think able-bodied or neurotypical people have any businesswriting neurodivergent and/or disabled characters. But that’s the thing: theydon’t have the business, but they still do it, and get paid and awarded for it.Because societies do not exist without someone being more susceptible than theother, and more apt to be exploited and marginalized.

In the United States alone, Black families on average have afraction of saved wealth that white families do, due to hundreds of years ofunpaid labor. Their descendants have less inherited wealth to invest inhousing, education, healthcare, and travel. That means generations of Blackcreatives have had a starting line dozens of miles behind their typical White peer.Indigenous peoples in this country are the descendants of communities activelytargeted with genocide and are still enduring tactics of it in environmentaland land-grabbing public “policies.” Trans women of color’s average expectedlifespan is ~35 years.

There is absolutely no fucking reason why characters who look likethem, who come from experiences they have had, who are products of theimaginations in this world, should be coming from anywhere else but them. Thetalent and skill are out there, the content is out there, and they are workingtheir asses off in a system that does not serve them and in fact repressesthem.

But I think all in all, my statement should be more precise: Thereis absolutely no fucking reason why white cishet people should have theliberties they do in creative fields to write racism, racial sexism, colorism,misogynoir, that they do. The fact that a white person can make a movie, writea book, make a TV show about racism, or a cishet person can make content about homophobia/transphobia,and be paid for it, and take credit for the work those communities do, shouldtell you they have no business. And yet. People from those communities andgroups die in the streets, in detention centers, in prisons, etc. and yet theirexperiences don’t matter as much as the hot new story on the movie posters orin the game trailers. This is the social product of hundreds of years of imperialismtaking stories, taking cultures, and taking heritages, and claiming ownershipover them. Popular culture and media does not exist outside of theseideologies, and in fact they are blunt results of them.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sci-Fi Feminists

By Becky and Claire

Background

Science Fiction is all about imagining a different reality. Whether that be spaceships, laser beams, or rights for women.

A common misperception is that sci-fi has always been a genre dominated by men and male protagonists; however, this is not the case. There is some speculation in regards to when the science fiction genre was born, yet many consider the creator of the first sci-fi/horror novel to be Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who wrote Frankenstein in 1816, though even before this Margaret Cavendish wrote The Blazing World in 1666.

Although not necessarily the first sci-fi writer, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has experienced great acclaim for centuries–and for good reason. Shelley openly explored themes of death, isolation, and moral ambiguity. She has since inspired countless authors, including Ursula Le Guin–whose writing challenges the constrictive social norms of binary gender. Also, like those of her time and before, Octavia E. Butler has succeeded in using gender and race as a means of exploration as well as a call to action. These women’s lives influenced their writing in a multitude of ways, which is why many scholars throughout history have analyzed their personal journeys of growth, inspiration, and loss that led them to new and alternate realities.

Here is a good start to the timeline of major science-fiction authors, and here is a list of exclusively female writers.

Prominent Authors: Mary Shelley

When Mary Shelley began writing Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus in 1816, she wrote it in response to a challenge. Her father was the famous philosopher William Godwin and it was at a dinner party her father had hosted, with guests such as Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, where the challenge was posed for each esteemed writer to come up with the best ghost story. In the end, Mary Shelley (then known as Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin) won, as her early draft of Frankenstein captivated its first audience.

Yet for such a young woman–only eighteen at the time– the themes she wrote about were incredibly complex and macabre. Her life began tragically, as her famous feminist mother died only a month after her birth, a death she would mourn for the rest of her days. When she met and fell in love with the great poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, their romance was only accepted after the tragic suicide of his estranged wife. She continued to experience the loss of three of her four children as well as her half sister.

Plagued by death and grief, Shelley’s dark themes were a cathartic release; the juxtapositions of the living and the dead within her work, as well as the question of morality continue to spark debate to this day. The character of Frankenstein’s monster begs the question: what does it mean to be human, to be alive? Moreover, are humans fundamentally good beings? These questions appear again in Ursula Le Guin and Octavia Butler’s brilliant contributions to science fiction, where similarly complex topics are asked, such as: what are gender and race? Why do they exist? [Mary Shelley-Source] [Mary Shelley-Source 2]

Ursula Le Guin

Usula Le Guin wrote The Left Hand of Darkness in 1969 during the second wave feminist movement in the United States, where gender was a heated topic for almost everyone.

Facing her fair share of rejection of publishers refusing to take a woman seriously, let alone a woman writing in the genre of science fiction, LeGuin was determined to share her game-changing novels. As a daughter of a female writer herself, Le Guin knew the value of a good story, and had been inspired from a young age to create her own nonconventional worlds. The Left Hand of Darkness, in addition to the Earthsea Chronicles, are Ursula Le Guin’s best known works. The Left Hand of Darkness and other books in the Hainish Cycle take place in a solar system with many planets whose different environmental factors led to the androgyny and nonbinary nature of the race named the Gethenians.

Her mainstream challenging of social norms opened doors previously percieved as closed for other feminist and nonbinary authors to began grappling with questions of identity, morality, social hierarchy, and even religion. By the end of her life, Ursula LeGuin had written dozens of award-winning novels, poems, and children’s books that had changed the science fiction world forever. These issues brought alien distopias down to earth, as it were. [Ursula Le Guin-Source]

Octavia E. Butler

A facet of science-fiction is the exploration of dystopian worlds that provide insight into the future of our own–no author was more talented at predicting these all-too-real conditions than Octavia Butler. Before her death in 2006, Butler wrote over two dozen novels and short stories that illustrated many scenarios unsettlingly similar to our current political and social climate. From a young age, Butler was surrounded by books brought home from her mother who worked as a maid during the era of segregation in California–books that would transport her to worlds beyond what was possible, at least for now.

These books drove her to create stories of her own that imagined protagonists as empowered black women, as gender fluid shape-shifters, and so on. These works, though fantastical, were also rooted in the struggles of society during her lifetime, and provided essential insight into the Civil Rights Movement and second-wave feminism.

Of course, life was never easy for Butler, who had to balance many jobs at once, and was often underestimated due to her sex and race. Yet after the modest success of her 1975 novel Patternmaster, which envisioned a dystopian world that brought together themes of hierarchy and unity, she traveled across the country to Maryland, and found even more fame and recognition after she published her next work, Kindred.

Butler envisioned worlds that validated and brought to the forefront the struggles of everyday black people, while using fantastical backdrops to tell their complex stories. Today she is known for her afrofuristic themes, with many of her novels being read in university classes regarding queer theory, Black feminism, and disability studies. [Octavia E. Butler-Source 1] [Afrofuturism]

Use of Utopias and Dystopias

These women, and countless other authors, have used their writing to develop the idea of utopian and dystopian worlds. By imagining a world with true, universal human rights, or a society without gender and racism, these women strove to prove that anything was possible.

A utopian world is one that is perfect in every way–but in the process of creating those perfect worlds, dystopias are often born instead. For all the fantastical characters and settings they describe, they are ultimately commenting on our current world and it’s ugly realities hidden beneath the surface. They further present the question, is a utopian world possible? What makes our current world dystopic? As Ursula Le Guin says in her interview with “The Nation’’, “The future in science fiction is just a metaphor for now.” For More information on utopias, check out this TedEd video.

Sci-Fi in Politics

As women and authors, Shelley, LeGuin, and Butler along with countless more feminists work not just for entertainment, they write for the larger community of activism. Activism is a way to gain support for a cause but rarely is it done alone. Margaret Kick and Kathryn Sikkink elaborate in “Transnational Advocacy Networks in International Politics” (from Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics, 1998).

Authors in sci-fi are like the transnational networks that Keck and Sikkink discuss, in that they also use the four typologies of persuasion: 1) information politics, 2) symbolic politics, 3) leverage politics, 4) accountability politics. When authors like Shelley, Le Guin, and Butler present the issues most prominent in their lives, they present the information “where it will have the most impact” (p. 281). That space is the public who has the power to influence society.

Furthermore, they use symbols in their writing to make the point that utopias or dystopias really aren’t that different from where we are today. When using leverage politics in writing, authors tend to “call out” major actors such as state regimes, as Margaret Atwood does in her “Handmaid’s Tale”. This can be done explicitly as Atwood does or implicitly as seen in some of LeGuin’s work. Similarly for accountability politics, authors don’t have the power to hold states to their policies; however, they are able to conjure public support behind an issue. For example, if a government claims to have eliminated all racist and sexist language from its governing documents but has not, then an author may use that in a novel to push the government for change.

Sci-Fi for the Real World

When imagining a better world, a world where governments and organizations are held accountable for their actions towards people of color and female-identifying people, we can look to these feminist writers for inspiration. These women paved the way for visionaries from all walks of life to have hope for a better future. Science fiction is an instrument of societal rebuilding, and it can have enormous impact on the way people choose to engage in the world.

Science fiction also has the capacity to challenge racist, sexist, and heteronormative norms that hold our society back from unity and prosperity. In promoting feminism, authors like Le Guin and Butler normalize equality of the sexes, and even allow future generations to take the reins, as it were, and normalize gender fluidity, androgyny, and non-binary people.

As we grow in awareness and knowledge throughout our transformative years at college, we can harken back to these trailblazers and the messages they left in their books. These messages tell us we are powerful in our femininity, that humans are infinitely complex and changing, and that change is necessary for a better future. We can build many aspects of the better worlds laid out before us–and we can learn from the dystopias as well. Our story as humans is far from over, it is not too late for us to embark on a new chapter.

Links used above:

https://www.bl.uk/people/mary-shelley#

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/mary-wollstonecraft-shelley

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_vzSgkjBEI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6a6kbU88wu0

https://www.bbc.co.uk/teach/writing-the-future-a-timeline-of-science-fiction-literature/zjfv6v4

https://library.sdsu.edu/scua/new-notable/early-female-authors-science-fictionfantasy-0

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20200317-why-octavia-e-butlers-novels-are-so-relevant-today

https://haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/afrofuturism/

https://www.ursulakleguin.com/biography

Bibliography:

Keck, Margaret E., Sikkink, Katheryn. “Transnational Advocacy Networks in International Politics”, Activists Beyond Borders:Advocacy Networks in International Politics, 1998. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

#submission#publicscholarship#global sociology#art#activism#octaviabutler#feminism#racism#scifi#afrofuturism#ursula le guin#mary wollstonecraft#margaret atwood#queer

0 notes

Text

WisCon 43 panel Polyamory And Alternative Relationships In Fiction And In Real Life

Science fiction is rife with examples of how to love outside the box. From Le Guin to Jemisin to Steven Universe, speculative fiction allows us to create and experience relationships often shunned by mainstream society. What fiction do we resonate with, or wish was reality? What offers food for thought, or has helped us with our own complicated relationship styles? Who gets it "right"? This panel will explore titles showcasing polyamory, asexual relationships, relationship anarchy, & more.

Moderator: Rebecca Mongeon. Panelists: Emily Luebke aka Julian Greystoke, Rose Hill, Samantha Manaktola, Nisi Shawl

Disclaimers: These are only the notes I was personally able to jot down on paper during the panel. I absolutely did not get everything, and may even have some things wrong. Corrections by panelists or other audience members always welcome. I name the mod and panelists because they are publicly listed, but will remove/change names if asked. I do not name audience members unless specifically asked by them to be named. If I mix up a pronoun or name spelling or anything else, please tell me and I’ll fix it!

Notes:

Samantha introduced herself as queer and non-monoagmous with found family and networks of people in her life.

Emily introduced herself as an author, actor, and asexual married to a pansexual man.

Rose introduced herself as demi-pan and married to a straight man and dating an ace bi woman [I think I got that right but have a “?” in my notes so maybe I mixed something up]. She said she writes poly in her fiction.

Nisi said she was exposed to poly since when she was a hippie and then she later read a comic about it where it was named and realized “oh, that’s what I’m doing!” It features in her fiction and she is interested in non-romantic/non-sexual relationships as being the core of a story.

Rebecca started the discussion about found family.

Rose talked about intentional family and cited the Circle of Magic series by Tamora Pierce, which features a family of non-bio and non-romantic connections. They live together and begin to refer to one another as family over time. Those bonds last as they age. [I am currently reading this series and am enjoying this aspect of it.] Rose connects to created families.

Nisi said this is based on her lived experience in the black community. She views the entire black community as a found family and grew up calling neighbors aunts and uncles, etc. She talked about this being a silver lining of the results of the slave trade breaking families up. When people call one another brother and sister - it’s because they are. You don’t know if they are or aren’t, so you claim them. We decide that we are family. Nisi added that there is also the African idea of claiming your ancestors whether you know for sure if you’re related to them, for similar reasons.

Emily talked about being a theater kid and how the theater became her family.

Samantha talked about the shows Steven Universe and Leverage and how the message is that being the person you are makes the bonds with your people tighter, and the tighter those bonds are, the better you get at being yourself.

An audience member brought up the issue of combined bio and found families. People tend to respect the closeness of non-romantic ties if you are siblings, but friends are “just friends.”

Nisi told about how her mom adopted Eileen Gunn because she and Nisi became sisters, so her mom figured - that makes her my daughter, too.

Samantha talked about her mom and how she did not necessarily understand about ethical non-monogamy, but she tried. She tried to map it onto experiences of non-ethical non-monogamy, and ended up thinking she would still eventually choose one person. Her mom did understand the importance of her friendships, and said that her friends were therefore important to her, as well.

Emily talked about a friend that her dad decided was part of the family - whether her liked it or not.

An audience member asked the panelists to clarify their definitions of chosen vs. found family.

Samantha said it’s mostly interchangeable but there is some nuance. Chosen can be intentional, found family maybe you just fell into.

Rose agreed that it’s interchangeable.

Rebecca brought up the issue of ace representation.

Nisi said she wants people to talk to her about this [I believe the context was for her to better understand for writing inclusion purposes?].

Samantha said the answer to this is not very satisfying. It’s a lot harder to find ace representation that any other kind of non-traditional relationship style. She mentioned that Seanan McGuire has done it, and that Anne Leckie’s Ancillary Justice has some in it but it’s questionable because it’s not a human character.

Emily said it’s mostly aliens and robots that she found, especially when younger. She includes at least one ace character in all of her works now. One example of rep is Let’s Talk About Love which is an ace love story. McGuire’s Wayward Children had rep but she didn’t love it. Radio Silence has a demi-sexual character.

Rose added that explicit ace rep is rare. Often it’s just not said and she’s left wondering if she is just headcanoning it. The Perfect Assassin has an ace romance sub-plot. She is wondering if there is any ace poly rep?

Nisi brought up The Bicycle Repairman by Bruce Sterling - not really ace rep because the character removes all sexual feeling.

Rose said that her ace groups tend to talk about poly a lot as something that makes sense, but her poly groups don’t tend to do the same - and in some cases seem to think it is antithetical.

An audience member asked how an author can explicitly show that a character is ace without it being about their asexuality.

Rose said that romantic subplots are super common, so you could have one character flirting with another and the other character just says “oh sorry I’m not attracted to people in that way” and there you go - explicit ace rep.

Emily added that if you’re writing from the pov of an ace character, it can be very obvious that they’re just not interested.

Nisi talked about a character in three of her short stories and a novel [I think it was Brit Williams?] who likes the idea of having kids but is grossed out by what you have to do to make one. Also mentioned how in historical fiction it might be hard to talk about explicitly because there wouldn’t have been language for it - but a character can still be shown to be ace even if they aren’t using those words.

Emily added that when you’re ace, you just don’t think about that stuff much. The character might be surprised to find out how much other people are thinking about sex, for example.

An audience member asked if poly was on the same axis as queerness as an identity.

Rebecca said she wasn’t sure this was the right place for that discussion. [Fair. It’s a complex issue and not necessarily the scope of this particular panel imo.]

Another audience member asked about world building when things are assumed that are different from our world - such as everyone in that world is poly.

Samantha answered that there are different ways to do poly as a social construct. Anne Leckie, for example, built a world without gender norms and everyone was “she.” [Didn’t catch the title] Another piece I didn’t catch was referenced in which two societies are put into contrast with one another where one has poly as the assumed family structure and one doesn’t. Basically, there are a lot of different ways to build this into a world.

Rose added that world building with poly and queerness tends to be static whereas in real life it can be very fluid or change over time. Societies built as commentary tend to be fixed systems.

Nisi had some recs along those lines - a short story, Otherwise; Candace Jane Dorsey’s Black Wine; The Devil in America.

An audience member rec’d Shadows of Aggar by Chris Anne Wolfe, which has poly world building.

Another audience member suggests Nalo Hopkin’s work, which is often about liberating sex, love, and desire, especially from perspectives of people with disabilities and from marginalized races.

Samantha spoke about living with chronic pain and how it helps to have a strong network of people to help care for her. Additionally, overcoming trauma around sex has been helped by polyamorous relationships. It’s been empowering and healing.

Samantha rec’d Ruthanna Emrys’ work - Winter Tide, Deep Roots, etc. about a group of researchers. One of them is Deaf and they all communicate in sign language. When they might have to disband, it’s difficult because they have become family but also they’re losing this capability of communication with one another and source of strength they’ve found with each other.

Nisi mentioned Five Books About Loving Everybody, I believe this post she wrote about books with poly: on tor.com - out of those, the only one she thought was liberating was N. K. Jemisin’s The Obelisk Gate. But Octavia Butler’s Fledgling was about nurturing.

An audience member suggested The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez

Nisi commented “I keep naming all of these black authors... hmmm.... I wonder why.”

Rebecca asked the panelists about poly utopias.

Nisi said Samuel Delany’s Tales of Neveryon is a reverse anthropology - not utopian, but it seemed as if the society was polygamous with one male and multiple females who were closely bonded. It might have been a man owning several women, but it ended up being a bunch of strong women who bring in one man.

Samantha said the most true-to-life stories are not utopias. There are less stories about opening up a relationship that’s already there than stories about people finding one another in the third act.

An audience member suggested Gentleman Jole and the Red Queen by Lois McMaster Bujold - it resonated with them, but they know others who react to it very differently.

Another audience member talked about what makes the characters feel more real to them, what draws them in more is not the world building but the character building.

Last audience rec that I got down was Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time.

[This was a fascinating panel with moments that meant a lot to me emotionally and cool stuff I learned more about and lots of recs to check out - thanks panelists!]

0 notes

Text

SUMMARY

Set in a post-nuclear war of the year 2024, the main character, Vic (Don Johnson) is an 18-year-old boy, born in and scavenging throughout the wasteland of the former southwestern United States. Vic is most concerned with food and sex; having lost both of his parents, he has no formal education and does not understand ethics or morality. He is accompanied by a well-read, misanthropic, telepathic dog named Blood who helps him locate women in return for food. Blood cannot forage for himself due to the same genetic engineering that granted him telepathy. The two steal for a living, evading bands of marauders, berserk androids, and mutants. Blood and Vic have an occasionally antagonistic relationship (Blood frequently annoys Vic by calling him “Albert” for reasons never made clear) though they realize they need each other. Blood wishes to find the legendary promised land of “Over the Hill” where above ground utopias are said to exist, though Vic believes that they must make the best of what they have.

Searching a bunker for a woman for Vic to rape, they find one, but she has already been severely mutilated and is on the verge of death. Vic displays no pity, and is merely angered by the “wastefulness” of such an act as well as disgusted by the thought of satisfying his urges with a woman in such a condition. They move on, only to find slavers excavating another bunker. Vic steals several cans of their food, later using them to barter for goods in a nearby shantytown settlement.

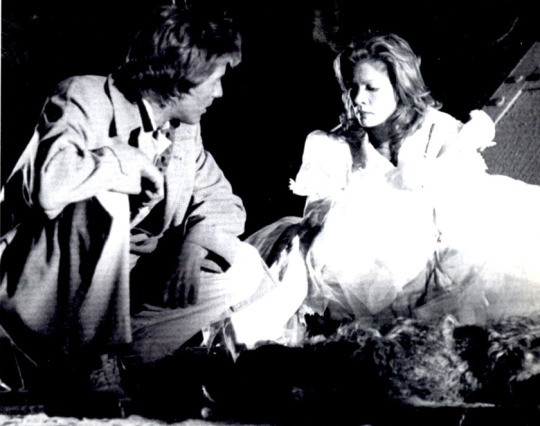

That evening, while watching old vintage stag films at a local outdoor movie house, Blood claims to smell a woman, and the pair track her to a large underground warehouse. There, they meet Quilla June Holmes (Susanne Benton), a scheming and seductive teenage girl from “Down under”, a society located in a large underground vault. Unknown to the pair, Quilla June’s father, Lou Craddock (Jason Robards), had sent her above ground to “recruit” surface dwellers. Blood takes an instant dislike to her, but Vic ignores him. After Vic saves Quilla June from raiders and mutants, they have repeated sex. Eventually, though, she takes off secretly to return to her underground society. Vic, enticed by the thought of women and sex, follows her, despite Blood’s warnings. Blood remains at the portal on the surface.

Down under has an artificial biosphere, complete with forests and an underground city, which is named Topeka, after the ruins of the city it lies beneath. The entire city is ruled by a triumvirate known as “The Committee”, who have shaped Topeka into a bizarre caricature of pre-nuclear war America, with all residents wearing whiteface and clothes that harkens back to the rural United States prior to WWII. Vic is told that he has been brought to Topeka to help fertilize the female population and is elated to learn of his value as a “stud.” Then he is told that Topeka meets its need for exogamous reproduction by electro ejaculation and artificial insemination, which will not allow him to feel the pleasure or release that he seeks. Anybody who refuses to comply or otherwise defies the Committee is sent off to “the farm” and never seen again. Vic is then told that when his sperm has been used to impregnate 35 women, he will be sent to “the farm.”

Quilla June helps Vic escape because she wants him to kill the Committee members and destroy their android enforcer, Michael (Hal Baylor), so that she can usurp power. Vic has no interest in politics or remaining underground, only wishing to return to Blood and the wasteland, where he feels at home. The rebellion is quashed by Michael, who crushes the heads of Quilla June’s two co-conspirators before Vic disables him. She proclaims her “love” for Vic and decides to escape to the surface with him, realizing her rebellion has been undone.

On the surface, Vic and Quilla June discover Blood is starving and near death. She pleads with him to abandon Blood, forcing Vic to face his feelings. Vic decides that his loyalties lie with Blood. This results, off-camera, in her being killed and her flesh cooked, so that they can eat and survive. Blood thanks Vic for the food, and they both comment on Quilla June, with Vic stating it was her fault to follow him, and Blood joking that she didn’t have bad ‘taste’. The film ends with the boy and his dog walking off into the wasteland together.

The production and making of this movie is related in several interviews (with L.Q.Jones and Harlan Ellison) and articles written over the years from various sources.

DEVELOPMENT

L.Q. Jones is a two-man film production company established by supporting actors L. Q. Jones and Alvy Moore as an outlet for creative energies often untapped in their all but countless film and television roles. Working out of two rooms of disorganized clutter which serve as office, cutting room and miscellaneous storage area, the pair have recently completed their fourth feature film, A BOY AND HIS DOG, based on the award winning novella by science fiction’s most celebrated prodigy, Harlan Ellison.

The two paired together in 1963, and with the slimmest of shoestring budgets, produced THE DEVIL’S BEDROOM, a melodramatic tale of a simple-minded youth accused of murder and hounded by an enraged posse. Jones, who wrote, directed, and acted in the film, admits that technically THE DEVIL’S BEDROOM is probably the worst picture ever, but over a period of time it earned enough to enable them to produce THE WITCHMAKER, a more polished horror shocker involving witchcraft in the Louisiana bayous and parapsychologist Alvy Moore’s attempts to unravel a series of bizarre murders. Then came THE BROTHERHOOD OF SATAN, a film of critical as well as box office, success, in which both Jones and Moore played supporting roles to Strother Martin’s murderous warlock who masquerades as a genial country doctor.

Why did you and Alvy Moore decide to form the LQ/JAF production company?

LQ: I got tired of doing the crap that we did. No, that’s not true. I enjoyed doing it, but if you want to be creative, you have to do it yourself. And so Alvy Moore and I, we’d been friends for a hundred years it seemed like, so we formed our own company. And whenever things got bad and hideous from doing all those crappy lines you had to do, we’d go out and write some crappy lines of our own and make a picture. So we ended up doing four pictures totally on our own, and that’s why I got very lucky. Because you can work your fanny off, do a marvelous job, and on a scale of 1 to 100 you’ve accomplished about a minus three. Because you have to turn it over to the distributing arm, and it’s completely out of your hands from that point on. But I said, “To hell with that.” And when I was first making my pictures, I started going with them. I was one of the few people in our business that not only made pictures, but sold them. Even people like William Wyler didn’t do that. He made them for someone else. Of course, he had talent and a lot of money. But we’d make ours and then take them out. And we made four pictures, and it’s hard to say this — all four of them ended up on ’10 best films of the year’ lists. It’s amazing. One was The Witchmaker. One was The Devil’s Bedroom, which they booked it into houses where everybody wore raincoats. They thought it was gonna be a sexy to-do. But that was the name of a cave, and the story was about a man who loved the outdoors. And his brother didn’t care for him that much. The father had found oil on his property, and made some money. And when he died, he left it to the two sons. The one that John Lupton played just enjoyed hunting and the land for the land’s sake, and took care of it that way. His brother, played by Dick Jones, wanted the money. And so he and his wife connived and put John in the insane asylum, so that they could control the estate. And John escaped, and the brother and his wife are both killed under suspicious circumstances. John is blamed for it, hunted down and killed, burned alive in the cave. And then they found out a year or so later that he hadn’t killed them at all. He was just loose, and something happened to them. And The Devil’s Bedroom was what they had called the cave for years. It’s a true story. In Texas, there was that very funny thing of the law where if two people in a family swear up a deposition, you can be arrested for insanity. And I think it’s still on the books. They did it to protect something. I forgot what it was. Well, it backfired. And that’s what happened here. Dick Jones has John Lupton committed for lunacy, so he can sell and develop the oil on the land. The place nearby there was “The Devil’s Bedroom,” and that’s where he ends up being killed. And it’s one of the worst pictures God ever made, but I found out people liked it because they thought it was real. Their theory was, “No one can make this bad a picture that wasn’t real.” I mean, there had to be somebody who just went out with a camera and shot it. And so, they thought somebody was making real life. That is pure crap. But it was on a bunch of 10-bests of the year, and it was hideous. And then we made The Witchmaker, Come In, Children, and A Boy and his Dog.

LQ/JAF stands for “L.Q. Jones And Friends.” And we did it a lot to have fun. We just got lucky and things made money. And then it got to where, after doing A Boy and his Dog, I had a whole bunch of offers to direct, and more money than it cost to make the picture for chrissakes. But I couldn’t see working all that time and all that effort to make that. So I just kept saying, “No,” and I finally just said, “To hell with it,” and just stopped and went on with the acting. Because by then, I could pretty well pick and choose what I wanted to do. So, it was fun. It’s always been fun. But it was really fun for me, and the [company] was getting in the way. Although, we’re still distributing A Boy and his Dog 30 some-odd years after the fact. It played in a lot of places a long time. We played in one theater in Seattle for a year, which I thought was pretty good. But we really played in Paris, France in one theater for eight years. So, it’s a fun picture. It’s not made for everybody. I tell people, “I hope you like it when you see it. Because if you don’t, you’re gonna be hag-ridden. Because you can’t forget it. Every time you see a dog, it’ll kind of bring it up.” And so I said, “I really hope that you enjoy it when you see it. Otherwise, you’re gonna hate me.”

STORY/SCRIPT DEVELOPMENT

HE: I can often tell you how a story I wrote came into being. This is one I can’t. I’ll be damned if I can remember how or why I did this story. I think the whole thing came from the title. I really wanted to parody an Albert Payson Terhune dog story, and so I called it “A Boy and His Dog,” which is, you know, the gentlest kind of title possible. Actually, I was doing it mostly for my dog, Ahbhu: I used to read this story to him. That dog had an enormous influence on me. He was really the closest friend I’ve ever had, and his passing wiped me out for months. This story, I guess, was kind of my way of sharing something with him.

After the story won the Nebula, it got taken for a lot of college textbooks, and it was in the air, people knew it existed. The first call I got was from Warner Bros. and a producer there, whose name I can’t remember, offered me a lot of money. But then he let slip, he said: “Well, explain to me how we’re going to animate the mouth of the dog.” And I just reared back and realized that anybody who would even say that, who even thought of the story in that way, would just …I would have nothing but endless hours of aggravation I’d have to rewrite the script forty two times: eventually they’d bring in another writer on the thing: I’d be screwed out of my own production; and I said, “Thank you, anyhow,” and I motored. The next bid was about six months later, from Universal. And I don’t know who it was over there, either, but it was somebody up in the Tower. And he liked the story, but he wanted me to change the down-under section so that it was not so anti-middle class, patriotic, white America as it was: and I said no, I didn’t think I’d care to do that. But we had a number of meetings and we talked about it, and then he, too, said: “How are we going to do the dog?” I mean, he just didn’t understand about telepathy, at all. Then there was a French company, and they were talking about Antonioni to do it — which really excited me, except that the money was too low and they just seemed like they didn’t know what the hell they were doing. And there were a bunch of independents who wanted it off and on. This went on for about four years. Finally, one day I get a call from this dude, says: “Hi, there. My name is L. Q. Jones.” I recognized the name because I’m a movie buff and he was always the crazed redneck in some movie or other. He said: “You’ve got this story, ‘A Boy and His Dog,’ and I’d like to talk to you about doing it.”

First published in Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds.

LQ: We had just finished THE BROTHERHOOD OF SATAN, and were looking for another. Normally, when I’m trying to find a property I’ll read twenty-five, thirty, forty scripts a week, if I can get them. But I couldn’t find anything that I liked. Of course, when you don’t have all the money in the world, that precludes, in a lot of cases, doing the thing you want. One day, my cameraman, Johnny Morrill, brought in “A Boy and His Dog” and gave it to Sheila, the secretary, and said: “I think L.Q. might like this. Have him read it. “I read it and I loved it. It was one of those things that by the time I was halfway through, I was holding my breath, because I knew the ass was going to fall off of it, it was too good. But it didn’t. Right down to the last stroke, it was right. But then I began to have negative feelings about it, because I was envisioning it as an X picture, and I didn’t want to do an X picture. “You don’t realize how dumb you are,” my secretary told me. She had read it before handing it over to me. “Go back and read it again,” she said. “It’s a love story, but a true love story having nothing to do with sex.” With that in mind, I read it again, and she was dead right. So we called Harlan.

HE: And I said: “Well, I’m not really interested in selling it, I’ll be very honest.” By that time I was sick and tired of going to moron meetings and being jerked around by a bunch of clowns. And he says: “Well, come on down. I’ll buy you lunch.” As it turned out, I bought the goddamned lunch. That was my first meeting with L.Q. and Alvy. And I liked them immediately. I mean, really, they are so crazed and they are so unlike people in the industry. See, I’ve been out here since ’62, and I’ve done real well, I make a lot of bread. But there are people I won’t work for. I mean, there’s not enough money in the universe that they could offer to get me to work for them because they fucked me over, they lied to me, or they butchered something I wrote. And so I avoid, pretty much, the whole industry. I don’t hang out with producers and I don’t go to clubs, and do that number. And these guys were just like that. But I wasn’t about to give them any damned movie until L.Q. said: “Well, come on, we’ll show you one of our films.” And he showed me COME IN, CHILDREN which came out as THE BROTHERHOOD OF SATAN. I was really impressed by the film. Some amazingly interesting stuff. It opens with a kid’s wind-up toy tank going across the grass and over a bunch of cars, and it turns into a real tank crushing real cars. It has nothing to do with the picture, but it’s a staggering image! And there was just a load of really good stuff in it. And they said, we want you to do the script, and I asked L.Q.: “How do you plan on doing the dog?” And he said, “We’re just going to do it with a voice-over.” And I smiled. I could have hugged him, because of course that’s the way you do it. And I knew that even if they didn’t bring it off, at least they would try it the right way.

Available @ AMAZON

Vic and Blood: Stories Paperback by Harlan Ellison

LQ: And so we made the deal. Harlan was to write it, and he said he could write it in three weeks because it was his favorite story and he’d written it a hundred times in his head. I was going to be gone for three weeks on a picture, so I figured after about ten days I’d have half the script sent to me and I could read it while I was working on the other film. When I didn’t get anything after about two weeks, I called Alvy and asked him why he wasn’t sending me the script, and he said he wasn’t sending it to me because it didn’t exist. When I got back, Harlan still didn’t have an inch written. Three months later we still hadn’t gotten any script. Four months- same thing. Finally, I called him up, and I said: ‘I’ve got the ultimate threat, Harlan, if you don’t do the fucking script, I’m going to write it!” Well, that spurred him into unbelievable action, and I’II bet it wasn’t three days and he showed up with eighteen pages. And then we waited around another two months or so. Finally, I wrote the script. Whipped it out in only a year.

HE: I had been writing for something like 15 years without a vacation. I’d never had a day off, and I’d written every day of that fifteen years. And what I did not know was that I was just coming to a point where the machine was starting to freeze up. It was going to seize up on me, and there wasn’t anything I could do about it. I started to write the script, and I got about fourteen pages into it, and I couldn’t get any further. I couldn’t write another word. I couldn’t write anything! I was going crazy. It’s a terrifying thing, man. I write, that’s what I do. No matter what I’m doing, getting laid, going to a movie, having dinner. I know that where I should be is behind that typewriter. It’s a terrible cross, man. It’s like being doomed. If you go away on vacation, you can take off and go. I can’t go without a typewriter. I carry a portable with me everywhere I go. And to one day realize that you can’t write is really crushing. I love writing. It’s hard, there’s nothing easy about it. You know, that self-indulgent thing: “It’s a lonely, proud life to be a writer,” it’s true: it really is. You’re there absolutely all by yourself in front of a machine, and you’re locked inside your own head. And after a while, the people you’re writing about start to be more real to you than the people you hang out with: and the people that you meet are always so much shallower and less interesting than the people you’ve dreamed up: and you say, “What do I want to hang out with these people for when I can go back and be with those?” It’s a very strange life to be a writer or maybe it’s just me. Maybe I’m weird.

Well, you know, L.Q. has a budget operation. Mine was the only project he was working on, and I was running the poor son of a bitch into the poorhouse, because all of the money that should have been going into getting the production started he was wasting, waiting for me to get off my ass. And I messed him around for almost six or eight months. Which was terrible! And I kept telling him: “I’m doing it, I’m doing it,” lied left and right. And I was getting more and more frantic because I didn’t know what was happening. Finally, when I was able to admit to myself that I just could not write for a while, everything started to ease up. But it took me almost a year to get back to writing. It was the only block I’ve ever had, the only period in twenty years of writing when I couldn’t do any work. Well, L.Q. went ahead and did the script. You can imagine my horror. But he did a good script. He took it literally and directly right out of the book. The dialog is the same, almost virtually line for line; and the situations are the same, altered only in the respect that certain things were too expensive to film. And the ways in which he altered them are staggeringly, incredibly intelligent I mean, they really were. He’s a consummate filmmaker.

LQ: I love to write, but God, it’s brutal. If I wasn’t doing a picture or something else, I’d start working at 10 o’clock in the morning and I’d finish the next morning at 2 or 3 o’clock. Just hanging over a typewriter and banging it out. I rewrote the entire script maybe thirty-five or forty times; and I read his story maybe twenty five times a day. Even now, if I’ve got forty-five minutes, I’ll pull it off the shelf and read it again. To begin with, it’s a fascinating story, and gorgeously written, not a wasted word in it. And I find that each time I read it again, there’s one word which I’ve missed in context and it’ll shed light on what he tried to say about the other things. The picture is a picture of sensation.

What’s it like to be really dirty? What’s it like to be really lonely? You’ve got to learn to hate, and you’ve got to learn to love a little bit, and you’ve got to learn to fight all this is built into it. It’s the way he wrote it. Harlan writes more visually than he does with words. So what I was trying to do was find out what he meant, or what he saw, and then translate it into something. That’s why it took me a year to write it. I’d like to go back and work another year on it. The story is really brilliant. I wish I could say it was mine. But there are a number of things I found dead wrong in the book. His whole down under is wrong. And Harlan will now admit it to a few people, not many. He’ll even admit it to me every now and then. Now, mine could have been better, but I’m closer to the truth than he is. For example, there’s no way they’re going to bring Vic down under, with the lack of regard they have for him, and put him in with their girls. It’d be like taking the Methodist preacher’s daughter and putting her in a cage with an ape. It’s the same thing, Vic’s an animal. So they’re not going to allow that. The second thing is the green metal robot sentry, which of course, in the film, is Michael. Here are people who are agrarian. They would not tolerate a machine that was superior to them that looked like a machine. Small thing, but I think they would not allow it. Third, he tells me in the book that a boy who has barely managed to stay alive and free, and who gets laid once every six months, is put in the midst of all these females and all this food, and at the end of a week, he’s bored? You might tell me he’s wrung out, but you’re not going to tell me he’s bored. But that’s what he put forth in his story and I didn’t believe that. The big, big flaw in it, besides the thing about putting him in with the girls is… do you realize that once he goes below, he never thinks of Blood once? Now, that’s dead wrong. No matter what. Because it is a love story, even from Harlan’s point of view. You do not ignore that goddamned dog and that’s what he did, because he is never mentioned down below. Nor referred to. And that’s wrong. Then I thought it was wrong the way he had people chasing them. That society wouldn’t do that. They didn’t care. You know, “Let Michael take care of them, or let the green metal box take care of them we don’t do it! “I changed those things just slightly, and Harlan tends to agree and disagree.

PRE-PRODUCTION

Though early treatments of Jones’ screenplay retained the bombed out urban locale of Ellison’s novella, a switch was made as production options jelled. With limited funds at their disposal, LQ/Jaf was in no position to construct such a setting. Pacific Ocean Park, a condemned amusement park in the process of being torn down, captured something of the feeling they sought, with the only other prospect being some urban ruins in Yugoslavia, unrestored since World War II. However, in poring over research theses and reports on atomic warfare, Jones came across theoretical indications that a massive and simultaneous discharge of nuclear firepower could literally halt the rotation of the earth on its axis for a fraction of a second, but long enough for momentum to sweep the oceans of the planet over the great land masses, engulfing everything in mountains of mud. Jones decided to pursue this option and as scripted, the bulk of the film takes place over the post-holocaust remains of Phoenix, Arizona. Art director Ray Boyle designed a section of old Phoenix as it would appear from the surface if buried under twenty feet of mud. Then he and Alvy Moore drove out to a dry lake bed twenty miles outside Barstow, California, and staked out the streets and locations for the buildings.