#Platformisation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Week 5: Gamified Citizenship – How Social Media Turns Political Engagement into a Digital Game

🎮 1. When Politics Becomes a Digital Game

In the digital age, citizenship is no longer just about voting or joining traditional political organizations—it has expanded to include online activism, viral hashtags, and digital protest content.

But here’s the catch: political engagement is being “gamified” through social media platforms.

📌 Research Question: How do social media platforms and gamification mechanics transform digital political behavior?

⏩ Key Theories:

Gamification Theory (Deterding et al., 2011)

Platformisation & Algorithmic Governance (Van Dijck et al., 2018)

Hashtag Publics & Digital Citizenship (Choi & Cristol, 2021; Bruns & Burgess, 2011)

Clicktivism & Slacktivism (Morozov, 2011; Vromen, 2017)

💡 Main Argument:

Social media platforms gamify political participation by rewarding engagement through likes, shares, badges, and streaks.

Platforms like TikTok, Twitter, and Facebook turn political movements into challenges and interactive games.

This has both positive and negative effects on digital citizenship.

🤖 2. Gamification of Politics: From Serious to Playful

Gamification Theory (Deterding et al., 2011) describes how game-like elements are applied to non-game contexts to motivate participation.

So what happens when gamification meets digital politics?

(a) Reward Systems & Digital Citizenship

Social platforms introduce incentives to encourage users to engage in activism:

🔥 Hashtag Streaks – Posting daily with the same hashtag to maintain a “streak” (e.g., #FreeBritney, #MeToo). 🏆 Badges & Achievements – Facebook used to award Top Fan badges to those who engaged the most in political discussions. 📈 Leaderboards & Trending Visibility – Viral political tweets get algorithmic boosts, making them visible to more users.

📌 Gamification of Digital Citizenship Model (Illustrating how platforms use gamification to shape political behavior.)

⏩ Supporting Research:

Choi & Cristol (2021) argue that digital citizens are motivated by social and personal incentives in hashtag campaigns.

Vromen (2017) found that younger generations engage less in traditional politics but are highly active in digital activism through hashtag publics.

(b) Hashtag Publics: When Politics Becomes a Trend

Bruns & Burgess (2011) describe “hashtag publics” as temporary digital communities that form around specific political moments.

But social media algorithms have gamified these movements by turning them into viral challenges:

🎥 #IceBucketChallenge (2014) → #TrashTag (2019) → #BlackoutTuesday (2020) 🏁 #ElectionChallenge on TikTok, where users film themselves voting to farm likes and views.

⏩ Supporting Research:

Van Dijck et al. (2018) argue that platforms like TikTok and Twitter use algorithmic governance to actively shape political trends.

Bruns & Burgess (2011) initially described hashtags as organic, but today they are algorithmically curated, turning politics into a crowdsourced game.

📌 Visual: "Hashtag Publics as Gamified Political Tools" (Diagram showing how hashtags become interactive challenges.)

🎭 3. Clicktivism vs. Real Activism: Is Politics Becoming a Meaningless Game?

🚨 The Problem with Gamified Citizenship:

Evgeny Morozov (2011) criticized Clicktivism and Slacktivism—when people engage in politics just by liking, sharing, or posting without real-world impact.

📌 Two Major Issues:

1️⃣ Politics Becomes Superficial

#BlackoutTuesday faced backlash because people posted black squares without taking real action for Black Lives Matter.

2️⃣ Platforms Commercialize Activism

Facebook was accused of promoting paid political campaigns by boosting certain trends, turning citizens into "players" in a corporate political game.

⏩ Supporting Research:

McCosker (2016): Platforms don’t just provide spaces for activism—they control and monetize it.

Theocharis et al. (2023): Many users believe their digital activism has major impact, when in reality, it often doesn’t lead to tangible change.

📌 Visual: "Clicktivism vs. Real Activism" (Diagram contrasting digital engagement with real-world activism.)

🔮 4. Conclusion: Gamified Citizenship – A Tool or a Trap?

✨ Key Takeaways: ✔️ Gamification makes political engagement more appealing to younger generations. ✔️ Social media algorithms prioritize viral challenges over serious debate. ✔️ Gamification can increase participation but also risks turning activism into empty gestures.

💡 The Future of Gamified Citizenship:

Will politics become even more of a game on social media?

Can gamification be used without trivializing activism?

Are we real digital citizens or just players in an algorithmic political system?

📌 What do you think? Is gamification good or bad for activism? Let’s discuss! 💬👇

🔗 References

Choi, M., & Cristol, D. (2021). Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education. Theory into Practice, 60(4), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification.” Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011). Hashtag Publics: The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks. ProtoView, 2(42).

Morozov, E. (2011). The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. PublicAffairs.

McCosker, A., Vivienne, S., & Johns, A. (2016). Negotiating Digital Citizenship: Control, Contest and Culture. Rowman & Littlefield.

Theocharis, Y., Boulianne, S., Koc-Michalska, K., & Bimber, B. (2023). Platform affordances and political participation: How social media reshape political engagement. West European Politics, 46(4), 788–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford University Press.

0 notes

Text

Week 5: Platformisation

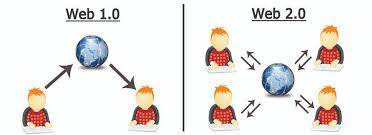

To give a short context. platformisation can be described the transformation of social network sites into social media platforms, which came into the rise of the platform as the dominant infrastructural and economic model of the social web and its consequences (Nieborg et al., 2020). People also considered platformisation as a method to describe many aspects of several digital platforms, which could be either business models, infrastructures or even algorithms,... In short, it is basically a change from Web 1.0 (which were one-way communication only) to Web 2.0 (the interactive interface).

In terms of people benefited from the platformisation, there were two main types of people affected. Normal media consumers can now have an easier time accessing the article online, and they had the ability to interact with the articles by expressing their opinion and have conversation with others about the content that are on the site at that time.

Consumers are not the only one benefited, as publishers and developers can also benefit from the platformization process. And the method of making any progress of that is to make their product able to reach out to new audiences and had a strong relationship with the customers (Spjeldnæs, 2022).

Of the example of platformisation, the most significant one may have been online news outlets, in which they intergrated some of the social network features into their outlets. By doing so, they let themselves open for everyone to interact and share the information in the web page on to their favourite social network site. Not only that, people can also discuss and communicate with others about the article, and thus can help people behind the article know the reaction of the consumer to the said article. This reaction would help publishers and writers to understand more about the audience that they are trying to reach out to.

REFERENCES USED:

Nieborg, D.B., Poell, T. and van Dijck, J., 2022. Platforms and platformization. The Sage handbook of the digital media economy, pp.29-49.

Spjeldnæs, K., 2022. Platformization and publishing: changes in literary publishing. Publishing Research Quarterly, 38(4), pp.782-794.

0 notes

Text

Week 5: What is Digital Citizenship? Hashtag Publics, Political Engagement and Activism

PLATFORM & PLATFORMIZATION

The term "platform" is multifaceted, encompassing diverse connotations across computational, political, and architectural spheres. In computational contexts, a platform serves as a foundation upon which further innovation and development can be built. Politically, it represents a space where individuals can voice their opinions and perspectives, serving as a platform for expression and discourse. Architecturally, platforms like YouTube are characterized by their open and inclusive nature, facilitating egalitarian expression rather than enforcing elitist gatekeeping practices. Gillespie (2010) emphasizes this aspect, highlighting YouTube's design as a welcoming facilitator of diverse voices, devoid of normative and technical constraints. Thus, the notion of a platform transcends mere technological infrastructure, resonating deeply within social, political, and cultural landscapes.

Platformisation represents a significant shift from viewing "platforms'' as “things” to an analysis of ‘platformisation’ as a process” (Poell, Nieborg, & van Dijck, 2019). It involves the evolution of social network sites into expansive social media platforms, signifying the rise of platforms as the primary framework for the social web's infrastructure and economy. This shift not only democratizes websites by enabling their customization through Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), thus facilitating integration with third-party services (Helmond, 2015), but also highlights the broader integration of digital platforms' business models, infrastructures, algorithms, and operational norms into various aspects of society (Chia et al., 2020). Consequently, platformisation serves as a lens through which to understand the far-reaching impact of digital platforms on contemporary socio-economic landscapes.

SHEIN CASE STUDY: IS SHOPPING PLATFORM A NEW TREND IN FASHION INDUSTRY?

SHEIN, standing as the global leader in fast-fashion and digital shopping, solidified its position by claiming nearly 28% of the U.S. fast-fashion market, surpassing even Amazon as the most downloaded shopping app, thereby presenting a formidable challenge to traditional giants like H&M and ZARA (Talenox, 2023). Unlike its counterparts, SHEIN prioritizes digital innovation over conventional brick-and-mortar strategies, significantly enhancing its digital prowess and operational efficiency.

Notably, SHEIN's adoption of cloud-based supply-chain management software has garnered acclaim from investors and suppliers alike, as it employs sophisticated algorithms to analyze consumer spending patterns and advise suppliers on optimal stocking levels, thus facilitating rapid and cost-effective production. This relentless commitment to digital transformation underscores SHEIN's forward-looking approach, facilitating automation and bolstering profitability.

Furthermore, SHEIN's ingenious incorporation of gamification elements borrowed from China's vibrant e-commerce market, notably pioneered by Taobao, has fostered an immersive and engaging platform. Through a nuanced points system incentivizing various interactions such as daily check-ins, purchases, and reviews, coupled with entertaining mini-games and live streams, SHEIN cultivates a loyal customer base and transforms the act of shopping into a delightful form of entertainment. Such strategic initiatives have not only augmented repeat purchase frequency but also propelled SHEIN to the forefront of an intensely competitive industry, characterized by fickle consumer preferences and dynamic market trends.

Jin and Shin (2020) elucidate three pivotal innovations within SHEIN's ultra-fast fashion business model, emphasizing its online-centric approach, seamless integration of AI and big data, and effective utilization of gamification strategies to enhance brand resonance and social media presence. By eschewing reliance on third-party platforms and establishing its proprietary website, SHEIN adeptly harnesses firsthand consumer insights to optimize its offerings and amplify revenue streams. This differentiated approach, coupled with SHEIN's distinctive Customer-to-Manufacturer business model, has empowered the brand to transcend traditional constraints, offering consumers unparalleled agility, affordability, and convenience (Uchańska-Bieniusiewicz & Obłój, 2023, pp. 52-53).

As a frontrunner in the cross-border e-commerce landscape, SHEIN continues to capitalize on emergent trends and technological advancements, leveraging its nimble positioning, robust data analytics, and astute market positioning to seize new opportunities and navigate evolving consumer preferences with aplomb (Yang, Li & Gong, 2023, p. 193). Looking ahead, the future of cross-border e-commerce heralds both opportunities and challenges, necessitating companies to embrace innovation, expand into new markets, fortify user experiences, and refine business models to sustain and enhance competitive edge in an ever-evolving landscape.

References

Chia et al., 2020. Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4), pp. 1-28.

Gillespie, T., 2010. The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media & Society, 12(3).

Helmond, A., 2015. The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready. Social Media + Society, 1(2).

Jin & Shin, 2020. Changing the game to compete: Innovations in the fashion retail industry from the disruptive business model. Business Horizons, 63(3), pp. 301-311.

Poell, Nieborg, & van Dijck, 2019. Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4).

Talenox, 2023. Inside SHEIN’s Strategy: Why H&M and ZARA are losing to the newcomer. [Online] Available at: https://blog.talenox.com/shein-business-strategy-hm-zara/ [Accessed 26th January 2024].

Uchańska-Bieniusiewicz & Obłój, 2023. Disrupting fast fashion: A case study of Shein’s innovative business model. International Entrepreneurship Review, 9(3), pp. 47-59.

Yang, Li & Gong, 2023. A Study on the Differentiation Strategy of Cross-Border E-Commerce - Taking SHEIN as an Example. Advances in Economics Management and Political Sciences, 37(1), pp. 185-194.

0 notes

Text

DIGITAL CITIZENSHIP AND PLATFORMISATION

Digital citizenship

This refers to people using technology and digital media in responsible and appropriate ways, especially in public areas, online communities, and social media (Choi, Glassman & Cristol 2017). It includes ideas like digital rights, privacy, cybersecurity, digital literacy, and online etiquette. The concept of "digital citizenship" highlights the significance of being a constructive and helpful member of the online community while also being conscious of the risks and repercussions of one's actions. It urges people to act responsibly when using the internet and to respect the rights and privacy of others as they would offline.

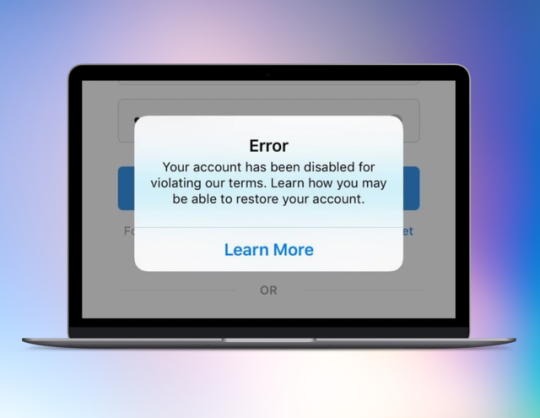

In light of current events, one example of the significance of digital citizenship is the rise in online harassment and cyberbullying. Cyberbullying has increased in frequency due to the growing use of social media and digital communication platforms. This has had detrimental effects, including mental health problems, social isolation, and extreme cases of self-harm or suicide. Many social media sites have responded to these problems by banning users from searching for certain racist, sexist, or destructive phrases in general. This is done to protect their impressionable, young audience.

Failure to abide by these digital citizenship guidelines may result in punishment from the platform the user is using (such as suspension or blocking from interacting), or, on a larger scale, leave a digital trail that could be linked to the individual in the event that they are the subject of necessary surveillance.

PLATFORMISATION

The process of converting conventional businesses or services into digital platforms that let people communicate with one another directly through networks or marketplaces mediated by technology is known as "platformization." Platformization has gained popularity in recent years as a result of the development of digital technology and the growing need for more practical and effective business methods. Successful platformization efforts include those found on sites like Upwork, which provides freelancing services, Shopee, which handles retail, and Uber, which handles transportation.

By facilitating more efficient and direct connections between buyers and sellers and eliminating the need for middlemen or intermediaries, platformization has the potential to upend established business structures (Fakieh & Happonen, 2023).

Platformization, however, also brings up questions regarding worker rights, data privacy, and competitiveness. It also may have a detrimental effect on established businesses and workers who stand to lose their jobs or become marginalised as a result of the growth of digital platforms. As a result, it's critical to weigh the possible advantages and disadvantages of platformization and to create legal and policy frameworks that uphold the rights of consumers, encourage fair competition, and assist platform economy workers.

Political engagement

It's a crucial component of digital citizenship since it gives people a platform to express their opinions on social and political concerns. People have greater opportunity to connect with like-minded people, engage with political content, and voice their thoughts because to the growing usage of digital technology and social media platforms.

Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have become powerful tools for individuals to express their political views, engage in discussions and debates, and mobilize support for various causes or candidates. Digital citizenship in the political realm involves not only being informed about current events and issues but also actively participating in discussions, debates, and advocacy efforts online. (Theocharis et al. 2022)

In politics, digital citizenship also includes the need to have courteous and civil conversations, to verify information before sharing it, and to be aware of any biases and false information in online content (Igwebuike & Chimuanya 2020). Through digital activism and involvement, people can advocate for positive social change, hold elected officials accountable, and contribute to a more informed and inclusive public discussion by engaging in good digital citizenship in politics.

REFERENCE LIST

Choi, M, Glassman, M & Cristol, D 2017, ‘What it means to be a citizen in the internet age: Development of a reliable and valid digital citizenship scale’, Computers & Education, vol. 107, pp. 100–112.

Fakieh, B & Happonen, A 2023, ‘Exploring the Social Trend Indications of Utilizing E-Commerce during and after COVID-19’s Hit’, Behavioral Sciences, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 5, viewed <https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/13/1/5>.

Igwebuike, EE & Chimuanya, L 2020, ‘Legitimating falsehood in social media: A discourse analysis of political fake news’, Discourse & Communication, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 175048132096165.

Theocharis, Y, Boulianne, S, Koc-Michalska, K & Bimber, B 2022, ‘Platform affordances and political participation: how social media reshape political engagement’, West European Politics, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 1–24.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 10: Gaming Communities, Social Gaming and Live Streaming - Twitch

I find it funny when individuals claim that gaming is only a pastime. Evidently, they have never been yelled at by a 12-year-old on Valorant or sobbed during a wholesome Twitch session. Communities for gamers are more than simply places to play; they are places where people go to live out their second lives.

Another good example is Twitch. It is more than just a streaming service; it is a things where community memes, parasocial connections, and chat expresses all come together in real time. In addition to being a performance, watching someone live-stream their Stardew Valley playthrough is more like a get-together. As T.L. Taylor (2018) puts it, we are all performing, responding, and connecting as "networked publics."

However, a lot is happening in the background. The "platformization" of game production, as defined by Chia et al. (2020), is reflected in the way Twitch moulds streamers' careers. Both independent developers and streamers must follow algorithmic guidelines: you must engage frequently, stream more frequently, and aim for recognition. It's comparable to speedrunning capitalism.

Keogh (2021) delves into Melbourne's indie dev culture, and it's amazing to see how these developers are putting ideals like community, experimentation, and oddity ahead of profit. Let's not forget about local pride for a moment. It is the complete opposite of what you would expect from a AAA studio. Simply for the feelings, it makes me want to learn Unity.

However, not every gaming environment is wholesome. There are negative aspects of internet gaming, such as toxic fandoms and chat room harassment. Particularly for marginalised gamers, found families flourish even in the midst of such chaos. According to Taylor (2018) and Ruberg (2019), livestreams featuring women of colour or queer producers provide safe environments where "GG" truly signifies more than "I won, lol."

Thus, it's true that gaming communities may be chaotic, endearing, messy, and brilliant—sometimes all at once. How about Twitch? It's more than a platform. One frame drop at a time, we get together there to grow, glitch, and connect.

References:

-Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/platformisation-game-development

-Keogh, B. (2021). The Melbourne indie game scenes: Value regimes in localized game development. In P. Ruffino (Ed.), Independent videogames: Cultures, networks, techniques and politics (pp. 209–222). Routledge. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/227028/

-Ruberg, B. (2019). Video games have always been queer. New York University Press. https://nyupress.org/9781479827985/video-games-have-always-been-queer/

-Taylor, T. L. (2018). Watch me play: Twitch and the rise of game live streaming. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691183558/watch-me-play

-Woodcock, J., & Johnson, M. R. (2018). Gamification: What it is, and how to fight it. The Sociological Review, 66(3), 542–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026117728620

1 note

·

View note

Text

Platformisation and the future of financial data

http://i.securitythinkingcap.com/TL9807

0 notes

Text

Plataformização: transformações institucionais e culturais na era digital

Vanessa Piasson

A plataformização representa um processo profundo e multifacetado que impacta significativamente diferentes setores da sociedade contemporânea. Muito além do conceito técnico de “plataforma”, os pesquisadores Thomas Poell, David Nieborg e José van Dijck propõem um olhar ampliado que considera infraestruturas digitais, dinâmicas econômicas, formas de governança e transformações culturais interligadas.

No artigo publicado na Revista Fronteiras – Estudos Midiáticos (2020), os autores definem plataformas como infraestruturas digitais (re)programáveis que moldam interações personalizadas entre usuários e “complementadores” (como anunciantes, desenvolvedores e produtores de conteúdo). Essas interações são organizadas por meio da coleta de dados, processamento algorítmico, monetização e circulação de informações.

O diferencial da abordagem está na análise da plataformização como processo, não como entidade isolada. Quatro perspectivas são apresentadas de maneira integrada:

Estudos de Software: exploram a dimensão computacional e a arquitetura das plataformas, revelando como a coleta e o uso de dados moldam as interações.

Estudos de Negócios: destacam a atuação das plataformas como mercados multilaterais, com estratégias para obter vantagem competitiva.

Economia Política Crítica: chama atenção para o poder concentrado, vigilância digital, exploração do trabalho e imperialismo das big techs.

Estudos Culturais: analisam como as práticas dos usuários reconfiguram culturalmente as plataformas, e vice-versa.

A interdependência entre infraestrutura, mercado, governança e cultura exige olhares interdisciplinares. Um exemplo prático é a loja de aplicativos, que sintetiza essas dimensões ao operar como infraestrutura tecnológica, ambiente de mercado, sistema de regras e mediadora de práticas culturais.

Como destacam os autores, compreender a plataformização é essencial para pensar a educação, a mídia, a política e a cultura na era digital. Trata-se de um desafio global: como integrar as plataformas digitais aos nossos sistemas sociais sem comprometer valores democráticos, justiça social e diversidade cultural?

REFERÊNCIA:

POELL, Thomas; NIEBORG, David; VAN DIJCK, José. Plataformização (Platformisation, 2019 – tradução: Rafael Grohmann). Revista Fronteiras – estudos midiáticos, v. 22, n. 1, janeiro/abril 2020. Disponível em: https:// revistas.unisinos.br/index.php/fronteiras/article/view/fem.2020.221.01 .

1 note

·

View note

Text

TUMBLR CASE STUDY WEEK 5

Digital Citizenship, Platformization, and Hashtag Activism: How We Shape Our Digital World

What does Digital Citizenship do?

Digital citizenship nowadays goes beyond simply being online; it involves how we engage, create, and connect within digital environments. While traditional citizenship focuses on rights and responsibilities within a country, digital citizenship emphasizes responsible and beneficial use of technology to support both personal growth and community well-being (Council of Europe, 2022). This encompasses activities like sharing content, online learning, defending human dignity, and fostering inclusion.

What is Platformization?

A crucial aspect of digital citizenship involves understanding the platforms we engage with. Social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok are not merely neutral environments; their algorithms and commercial structures influence our content exposure, interactions, and community development (Chia et al., 2020). This phenomenon, known as “platformization,” indicates that our online experiences are becoming more shaped by the design and policies of these platforms (Poell, Nieborg, & van Dijck, 2019).

A significant result of platformization is the emergence of hashtag activism. Hashtags such as #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, and #ClimateChange enable individuals to connect, share experiences, and mobilize around important issues (Theocharis et al., 2023). These temporary online communities, known as “hashtag publics,” can influence social and political change independently of conventional institutions (Bruns & Burgess, 2015).

Did politics participate in this?

Political participation has evolved as well. Rather than participating in traditional organizations like parties or unions, individuals now engage through online petitions, spreading news, or backing social movements via social media (Vromen, 2017). This modern approach to activism is more convenient and easier to access, but it also brings concerns regarding digital skills, equitable access, and the duties of users and online platforms.

In summary, digital citizenship today involves leveraging our voices and abilities to create a more inclusive, active, and accountable online environment amidst platform-driven interactions and hashtag activism.

(302 words)

References:

Digital Citizenship Education Handbook - Education - www.coe.int. (2025). Education. https://www.coe.int/en/web/education/-/digital-citizenship-education-handbook

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/platformisation-game-development

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425

Yilmaz, I., Akbarzadeh, S., Abbasov, N., & Bashirov, G. (2024). The Double-Edged Sword: Political Engagement on Social Media and Its Impact on Democracy Support in Authoritarian Regimes. Political Research Quarterly, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129241305035

Vromen, A. (n.d.). INTEREST GROUPS, ADVOCACY AND DEMOCRACY SERIES Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement The Challenge from Online Campaigning and Advocacy Organisations. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://content.e-bookshelf.de/media/reading/L-8377915-d076ab2bc9.pdf

0 notes

Text

Week 6: Are We the Same Online? The Ethics and Evolution of Digital Citizenship

"Hi everyone, welcome! I’m so happy you’re here. Today, we’re diving into Ethics and Evolution of Digital Citizenship, and I can’t wait to share my thoughts and experiences with you. Let’s get started! In this modern world, the rise of digital media and online platforms has introduced digital citizenship, a change in the traditional concept of citizenship, making it no longer restricted to physical borders or civic duties. As technology becomes a part of our everyday life, it is important for us to be responsible of the way we engage, communicate and behave online. According to Ribble (2015), digital citizenship refers to the principles of proper, responsible behaviour of individuals in relation to the technology used. Nonetheless, digital citizenship encompasses several digital literacies that are crucial for success in the digital age, some of which are more widely recognized (Bearden, 2016). Bearden (2016) also argued that some educators claim that we should remove the "digital" from digital citizenship and simply refer to it as "citizenship" as the principles of good citizenship (offline) is similar to online. However, the online world, has several context-specific issues that the offline world does not. For example, issues such as digital footprints, cyberbullying, online privacy, and the permanent online content are unique to digital environments.

Moreover, Öztürk (2021) explained that research on digital citizenship has expanded over time, suggesting that the importance of digital citizenship is increasing and play a crucial role in the future. Meaning that, the study on digital citizenship have increased over the years, highlighting its growing awareness and vital role in shaping future individuals. Bearden (2016) explained that technology leaders, parents, and educators are concerned about how individuals behave in digital societies, both within and outside of schools, and society as a whole. Therefore, the concept of digital citizenship must be taught and practiced in both education and other societal contexts as digital citizenship highlights not only the rights and freedoms but the responsibilities and accountabilities in the digital environment.

Additionally, platformisation acts as a catalyst in intensifying digital citizenship. Poell et al., (2019) refers platformization as how digital platforms infrastructures, economic processes, and governmental frameworks penetrate various economic sectors and areas of life, as well as how cultural practices and imaginations are reorganized around these platforms. For example, globally known platforms such as Facebook, Uber, Amazon, Coursera are becoming ever more integrated into both public and private life, changing important economic sectors and areas of life, such as journalism, transportation, entertainment, education, finance, and health care (Poell et al., 2019). As platformisation keep enhancing and becoming the new norm, digital citizenship plays a crucial role in shaping how individuals and society function. Hence, fostering ethical engagement and critical thinking is important to encourage responsible individuals in digital space. However, the question remains, is respectful behavior still valued online? And are we the same person online as we are offline?

References

Bearden, S. M. (2016). Digital citizenship: a community-based approach. Corwin, a SAGE Publishing Company.

Öztürk, G. (2021). Digital citizenship and its teaching: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 4(1), 31-.

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425

Ribble, M., & ProQuest issuing body. (2015). Digital citizenship in schools: nine elements all students should know (Third edition.). International Society for Technology in Education.

0 notes

Text

Week 6: What is Digital Citizenship? Hashtag Publics, Political Engagement and Activism

With the rapid creation of technology from smart hand-held devices to the digital world, it allows users to engage, discuss, and participate together, not to mention turning them into a digital citizen. Digital citizenship is defined as the public being able to participate in society online or use the internet regularly and effectively too (Mossberger et al., 2008). With digital citizen comes the platforms, where users go to engage their time with others online, or the rise of platformisation.

Platformisation is defined as the process by which more parts of economy, society and the web infrastructure are being penetrated to be designed well with digital platforms and how third parties are preparing their data to be easily used on these platforms (Poell et al., 2019). With one example of platformisation being app stores, where it is a centralised, software marketplace for downloading applications, instead of downloading applications from the official company websites (Poell et al., 2019). Another example can be seen with how newspapers were used by many last time, however, today newspaper and news in general has been increasingly turned into platform complementors, where users can access content through Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (Poell et al., 2019). With such platforms allowing users to socialise ties back to them being digital citizens online, and with that come connectivity between users when using said platforms.

An example of connectivity through platforms are hashtags, in which can bring about sharing experiences and allowing for socializing with one another like the #icebucketchallenge or to express attitudes like opinions and emotions with others (Laucuka, 2018). Hashtags can also bring about initiating movements that can inspire others, such as hashtags on #metoo, in which it helps to bring awareness of the issues of sexual harassment and to carry out repercussion with the Me-Too Bill (Laucuka, 2018). In all, digital citizens regularly use platforms that has been improved, allowing users a place to then socialise together online.

Laucuka, A. (2018). Communicative Functions of Hashtags. Economics and Culture, 15(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.2478/jec-2018-0006

Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C. J., & McNeal, R. S. (2008). Excerpts from Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007). First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v13i2.2131

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 9: Gaming Today: More Than Just Playing

Let’s get real—gaming isn’t just about playing anymore. It’s about watching others play, creating content, modding games, and even turning a hobby into a career. But in today’s digital age, indie developers, streamers, and gaming communities face serious challenges. They rely on massive platforms like Steam, Twitch, and YouTube, which dictate what gets seen, who succeeds, and how money moves. While gaming still thrives on creativity and community, the harsh reality is that big business is calling the shots.

Indie Developers: Creativity vs. Business Pressure

Indie developers are some of the most passionate creators in gaming, bringing innovative and experimental ideas to life (Keogh, 2021). Unlike large game studios that prioritize profits, indie devs tend to focus on artistic vision. But here’s the problem—no matter how creative they are, they still need to sell their games. And platforms like Steam and Epic Games highlight what’s already popular rather than taking risks on fresh, original content.

A prime example is Disco Elysium (2019), a critically acclaimed RPG praised for its deep storytelling and unique mechanics. The game became a huge success, but only because it won high-profile awards. Without that visibility, it could have been buried under thousands of other indie titles on Steam. The sad truth? Most indie games never even get noticed.

Keogh (2021) explains that indie developers operate within “value regimes,” meaning they must balance creativity with market demands. Even though they work independently, they still depend on big platforms to distribute their games. Chia et al. (2020) describe this as platformisation—where digital storefronts decide what gets seen and what doesn’t. The result? Indie developers aren’t as free as we’d like to think.

Live Streaming: Gaming for Fun or Performing to Survive?

Gaming isn’t just something you do—it’s something you watch. Platforms like Twitch, YouTube Gaming, and Facebook Live have transformed gaming into a full-blown entertainment industry (Taylor, 2018). Streamers can build communities, showcase their gameplay, and even make a living. But it’s not all fun and games.

Taylor (2018) explains that streamers are in a constant battle with Twitch’s algorithm, which favors big names and established creators. Smaller streamers struggle for years just to get noticed. For example, Twitch star Ninja became famous playing Fortnite, but thousands of smaller Fortnite streamers barely get any exposure. Many talented streamers grind for hours every day but never reach enough viewers to earn a sustainable income.

On top of that, trends like the “Hot Tub Meta” highlight how unpredictable platform rules can be—what’s allowed today might be banned tomorrow. Instead of simply gaming, streamers have to perform, adapt, and constantly grind just to survive.

Who’s Actually in Charge?

Chia et al. (2020) argue that platformisation has placed power firmly in the hands of major corporations. Here’s how it affects different groups:

Indie developers rely on Steam and Epic Games for sales, meaning their success is dictated by algorithms and shifting market trends.

Streamers are at the mercy of platforms like Twitch and YouTube, where engagement metrics control visibility and income.

Gamers face a world full of ads, microtransactions, and constantly changing policies designed to maximize corporate profits.

Even in an open-ended game like Minecraft, corporations still have the final say. Hjorth et al. (2021) explain that while players can mod, roleplay, and create their own worlds, Microsoft ultimately owns the servers and decides what’s allowed. A recent example is Minecraft’s ban on NFTs and crypto integration. While many players supported the move, it was a clear reminder that Microsoft—not the community—has the last word in shaping the game.

The Future of Gaming: Can We Take Back Control?

Gaming has always been about community, creativity, and connection. But today, it’s clear that those who control the platforms make the rules. Whether it’s indie developers struggling for visibility, streamers wrestling with the algorithm, or players navigating paywalls and microtransactions, one thing is certain:

Gaming isn’t just about fun anymore—it’s about survival in a corporate-controlled digital world.

So the big question is: Can gamers, developers, and streamers push back? Or are we forever stuck playing by the rules of corporations that care more about profits than players?

References

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., Davies, H., & Balmford, W. (2021). Exploring play. In Exploring Minecraft: Ethnographies of Play and Creativity (pp. 27–47). Palgrave Macmillan.

Keogh, B. (2021). The Melbourne indie game scenes: Value regimes in localized game development. In P. Ruffino (Ed.), Independent Videogames: Cultures, Networks, Techniques and Politics (pp. 209–222). Routledge.

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Broadcasting ourselves. In Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming (pp. 1–23). Princeton University Press.

0 notes

Text

🎮 Week 9: Gaming Communities, Social Gaming & Live Streaming – Where Play Meets Platform Power

Gaming isn’t just about play—it’s about communities, cultures, and platforms that shape how we interact and engage online. This week we explored how gaming spaces operate as social communities, how streaming platforms commercialize play, and how indie developers and modders navigate the growing platformisation of games.

🕹️ Key Themes: Communities, Platforms & Power

Keogh (2021) gives us a fascinating look at the Melbourne indie game scene, where local developers create games driven by community values and creative autonomy. Unlike AAA studios that chase profits, indie developers in localized scenes focus on authenticity and DIY ethics. However, Chia et al. (2020) caution that even indie creators are entangled in platformisation, relying on dominant platforms like Steam or itch.io, which control discoverability through algorithms. This raises a tough question: Can indie devs truly remain “independent” when gatekeepers like platforms influence who gets seen and who doesn’t?

Hardwick’s lecture also unpacked how gaming cultures often privilege white, male, and East Asian identities. Hjorth et al. (2021), through Minecraft ethnographies, show how even in open-ended creative spaces, exclusionary dynamics persist. Personally, I’ve seen how “gamer” identity is policed—players who don’t fit this narrow mold often have their skills or belonging questioned.

Taylor (2018) discusses how Twitch transformed from a niche platform into a massive entertainment and community hub, where streamers don’t just play games but also cultivate emotional and knowledge-based relationships with viewers. As someone who follows indie game streamers on Twitch, I can see how these spaces become “digital campfires,” where inside jokes, tips, and personal connections flourish—but always under the influence of platform monetization tools (subscriptions, donations, etc.).

GIF by geekedgamer

🎯 Independent Research: Cozy Gaming Communities on Twitch

Looking beyond the readings, I explored the rise of “cozy gaming” communities on Twitch. Streamers like Vixella and Kayla (lilsimsie) have built thriving audiences by focusing on wholesome games (e.g., The Sims, Stardew Valley) and fostering safe, inclusive spaces. Interestingly, these communities often resist toxic gamer culture, echoing Keogh’s and Hjorth’s points about creating alternative, more welcoming game spaces.

Yet, even cozy streams are shaped by platform capitalism. Twitch promotes channels based on viewership and interaction rates, so streamers still face the push-pull between community care and algorithmic demands (similar to Chia et al., 2020’s argument about platform dependency).

GIF by giffypudding

💭 Reflection: Tactical Participation or Platform Dependency?

What struck me most this week is how gaming communities are fluid—players flow between indie dev spaces, esports scenes, modding forums, and Twitch streams. Jenkins (2006) describes these as “knowledge communities”, where people share expertise and emotional labor. But there’s tension: while we gain community and creativity, platforms subtly steer participation toward commodification.

Personally, I’m left wondering: As digital citizens, how can we push for more autonomy in these spaces? Can we re-center community values over platform profits?

✨ Let’s discuss! Do you think gaming communities today are still grassroots and player-driven, or are they increasingly shaped by the logic of platforms? Share your thoughts! 💬👇

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., Davies, H., & Balmford, W. (2021). Exploring play. In Exploring Minecraft: Ethnographies of Play and Creativity (pp. 27–47). Palgrave Macmillan.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York University Press.

Keogh, B. (2021). The Melbourne indie game scenes: Value regimes in localized game development. In P. Ruffino (Ed.), Independent Videogames: Cultures, Networks, Techniques and Politics (pp. 209–222). Routledge.

Sotamaa, O. (2010). When the game is not enough: Motivations and practices among computer game modding culture. Games and Culture, 5(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009359765

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Broadcasting ourselves. In Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming (pp. 1–23). Princeton University Press.

0 notes

Text

Week 9 – Gaming Communities: More Than Just Button Mashing

════════════════════════════════════ ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ︶⊹︶︶୨୧︶︶⊹︶︶⊹︶︶୨୧︶︶⊹︶︶⊹︶︶୨୧︶︶⊹︶︶⊹

Let’s be real, gaming isn’t just about playing anymore. It’s about streaming, modding, socializing, and maybe even turning a hobby into a full-blown career. But how do indie developers, live streamers, and gaming communities navigate the digital landscape?

The Indie Scene: Passion or Profit?

Melbourne’s indie gaming community is a hotspot for creativity (Keogh, 2021). But here’s the catch: small studios often struggle with the "value regimes" that shape the industry. Meaning indie devs love making unique, experimental games, but the market (and platforms like Steam and Epic) often push them toward what sells, not what’s innovative.

Live Streaming: A New Way to Game (or Perform?)

Gaming isn’t just playing, it’s also watching others play. Twitch, YouTube Gaming, and Facebook Live have turned gaming into a spectator sport (Taylor, 2018). This builds gaming communities, allowing creators to earn money. However, it can be toxic, algorithm-driven, and exhausting for streamers trying to keep up.

And let’s not forget the Twitch "Hot Tub Meta" or the constant struggle of smaller streamers trying to get noticed. The platform isn’t always fair: big streamers thrive, while newcomers grind for years.

Platformisation & Who Holds the Power

Chia et al. (2020) explain how platformisation has changed game development. 🔹 Devs now rely on major platforms (Steam, Epic, Twitch, etc.) to distribute and market their games. 🔹 Platforms dictate who gets seen and who doesn’t.🔹 Players? We’re at the mercy of ever-changing monetization models, microtransactions, and corporate control.

Even in sandbox games like Minecraft, platform control affects creativity. Hjorth et al. (2021) explore how players make their own meaning through modding, roleplay, and shared experiences but at the end of the day, Microsoft still owns the server.

Community, Creativity, and Corporate Control

Gaming thrives on community, but the platforms controlling it hold the real power. Whether it’s indie devs trying to break through, streamers battling the algorithm, or players fighting for fairer microtransactions, one thing is clear: Gaming isn’t just about playing anymore, it’s about surviving the digital ecosystem.

════════════════════════════════════ ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ⁺ . ✦ . ︶⊹︶︶୨୧︶︶⊹︶︶⊹︶︶୨୧︶︶⊹︶︶⊹︶︶୨୧︶︶⊹︶︶⊹

Reference List

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., Davies, H., & Balmford, W. (2021). Exploring play. In Exploring Minecraft: Ethnographies of Play and Creativity (pp. 27-47). Palgrave Macmillan.

Keogh, B. (2021). The Melbourne indie game scenes: Value regimes in localized game development. In P. Ruffino (Ed.), Independent Videogames: Cultures, Networks, Techniques and Politics (pp. 209-222). Routledge.

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Broadcasting ourselves. In Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming (pp. 1-23). Princeton University Press.

0 notes

Text

The Evolving Tapestry of Digital Gaming Communities: Weaving Play, Platforms, and Place

Let me tell you about the time I joined a Minecraft server run by a 16-year-old in Oslo. Within hours, we’d built a pixelated homage to our hometowns—mine in Lagos, theirs in Norway. This isn’t just gaming; it’s alchemy, turning code into culture. Today’s gaming communities are ecosystems where play spills into politics, platforms shape power, and local quirks fuel global creativity. Let’s untangle how these threads intertwine.

1. Ambient Play: When Life Levels Up

Gaming isn’t confined to screens—it’s the soundtrack to our lives. Hjorth and Richardson call this “ambient play,” where games seep into “digital, material, and social environments” (Hjorth et al., 2020). Think of Pokémon GO players turning parks into collaborative battlegrounds, or Twitch’s 2.2 million monthly broadcasters forging parasocial bonds through shared triumphs (Hjorth et al., 2020). These interactions aren’t escapism; they’re reimagined rituals, blurring the line between leisure and life. But none of this exists in a vacuum—enter the platforms that host them.

2. Platform Power: Architects of Digital Worlds

If ambient play is the heartbeat, platforms are the circulatory system. Tools like Unity and Twine don’t just build games—they democratize storytelling (Chia et al., 2020). Unity’s claim to “democratize game development” isn’t hyperbole: it powers over half of modern games, while Twine empowers marginalized creators to share narratives too raw for mainstream studios (Hardwick, 2023). Hardwick observes that these platforms create “assemblages of smaller communities that players flow between,” fostering rich networks of interaction based on “skill, expertise, and knowledge” (Hardwick, 2023). Yet platforms aren’t neutral. Discord moderators draft community constitutions; Roblox developers negotiate profit-sharing models. Every algorithm and API shapes who gets heard—a tension as old as gaming itself. But here’s the twist: even global platforms can’t stamp out local flavor.

3. Local Scenes: The Soul Beneath the Code

Melbourne’s indie devs gathering in punk venues. Seoul’s League of Legends cafes buzzing with tactical debates. Keogh (2020) argues these “local scenes” thrive on “overproduction of value”—passion so intense it spills into zines, meetups, and DIY tournaments. These communities orbit “visible events, locations, or software” (Keogh, 2020), yet they’re anything but insular. A modder in São Paulo collaborates with a cosplayer in Jakarta, blending cultural motifs into a Skyrim mod. Local isn’t the opposite of global—it’s the spice in the stew.

The Big Picture: Gaming as Participatory Revolution

What stitches ambient play, platform power, and local scenes together? A seismic shift from consumption to co-creation. Gaming is no longer a “thing we do” but a language we speak—a way to protest (see Fortnite’s #BlackLivesMatter skins), grieve (memorial builds in Animal Crossing), or build utopias (decentralized game DAOs). This isn’t just play; it’s sociality reimagined.

Final Thought: Next time you queue up for a Valorant match or mod a Sims character, ask yourself: What world am I weaving?

References:

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515

Hardwick, T. (2023). Gaming Communities, Social Gaming and Live Streaming MDA20009 Digital Communities Week 8 2023.

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., Davies, H., & Balmford, W. (2020). Exploring Play. Exploring Minecraft, 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59908-9_2

Keogh, B. (2020). The Melbourne indie game scenes. Routledge EBooks, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367336219-18

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Rise of “Streamer Games”

Games like Among Us, Only Up!, and Goose Goose Duck have become popular not just for playing, but also for streaming. This raises a crucial question:

Are developers designing games for players or for views?

Watchability and Popularity

Indie developers now create content that must be seen to succeed. Success is no longer just about word-of-mouth or reviews; watchability has become key. A single Twitch streamer can make or break a game overnight. Brendan Keogh (2021) notes that capturing an audience through streaming has become a new form of value in game development.

Taylor (2018, pp. 1–23) expands on this idea, arguing that streaming transforms gaming into a performance, players are no longer just playing for themselves, but for an audience. Successful streamers don’t just play games; they entertain, engage with viewers, and shape trends. This means developers aren’t just thinking about mechanics and storytelling anymore, they’re considering how their games will look, sound, and feel when streamed.

Impact on Creativity

Game development is becoming more platformized (Chia et al., 2020), with games designed to fit platforms like Twitch and YouTube.

This leads to:

Hype-driven multiplayer games that quickly rise and fall.

Less focus on deep single-player experiences due to their lack of shareable content.

Games emphasizing shock value and meme potential over innovative gameplay.

While some of these games are genuinely fun, others may be overlooked because they don't fit Twitch's algorithm. This raises concerns about the potential for slower, more experimental games being ignored.

Balancing Player and Viewer Experience

The rise of streamer-friendly games isn't killing creativity; it's reshaping it. Developers must balance what makes a game fun to play with what makes it fun to watch. This isn't just about game design; it's about how we discover and engage with games. If platforms like Twitch and YouTube dictate what’s popular, then players, streamers, and algorithms all have a hand in shaping the industry.

Ultimately, the question isn't whether games are made for views or players, it's whether both can coexist. The success of Among Us proves that sometimes, the most watchable games are also the most fun to play. This balance is crucial for the future of game development, ensuring that creativity and innovation continue to thrive alongside the growing influence of streaming platforms.

References

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515

Keogh, B. (2021). The Melbourne indie game scenes: Value regimes in localized game development. In P. Ruffino (Ed.), Independent videogames: Cultures, networks, techniques and politics (pp. 209-222). Routledge.

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming. In JSTOR (pp. 1–23). Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc77jqw.4

0 notes

Text

Indie Games and the Age of Platforms: Who Controls Creativity?

Indie games were once a symbol of creativity and freedom, an escape from the control of large corporations in the gaming industry. However, the difference between indie and AAA games has become increasingly narrow over time. Do indie games still have the spirit of "independence", or are they gradually being swept into the wheel of the industry they once wanted to oppose?

🎮 Indie vs. AAA: When Independence Becomes a Flexible Concept

Indie games are traditionally understood as games developed without funding from large companies, while AAA games are products with huge budgets and large development teams, and are published by corporations like EA or Ubisoft.

However, indie games today are no longer operating in isolation as before. Keogh (2021) points out that the Melbourne indie community has not completely separated itself from the big industry, but instead has partnered with funding funds, distribution platforms, and even new business models. This raises the question: as indie games adapt to the market, will they still retain their original creative spirit?

🔗 When Platforms Shape Indie Games

Thanks to the development of platforms such as Steam, Epic Games Store, and Xbox Game Pass, indie games can reach millions of players. But with that comes the dependence on the algorithms and policies of these platforms.

According to Chia et al. (2020), platformisation not only helps indie games reach the market, but also creates invisible constraints – where the distribution algorithms and rules of the platform determine which games will be noticed. If a game does not fit the way the platform operates, it can be forgotten regardless of its quality.

📺 Streamers: Opportunity or Pressure for Indie Games?

In the past, indie games were known only to small communities. Now, if just one famous streamer tries a game, it can become a phenomenon - or fall into oblivion soon after.

According to Taylor (2018), streamers can create a huge success for an indie game but can also turn it into a fleeting trend, where sales depend on rapidly changing tastes rather than the core value of the game. This causes many developers to adjust their games to follow trends instead of pursuing the original creative vision.

🔍 Indie Games: Still Retaining Their Identity or Already Blending Into the Market Flow?

Indie games are still a creative space, but they are no longer a separate world from the gaming industry. It has grown stronger, reaching more people, but at the same time it has faced pressures from distribution platforms, algorithms and market trends.

However, what matters is not whether indie games are still "pure", but whether they continue to innovate and challenge old industry norms.

🚀 Do you think indie games still retain their creative spirit, or have they become part of the system they once rebelled against? Share your thoughts below! ⬇️

References

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515

Keogh, B. (2021). The Melbourne indie game scenes: Value regimes in localized game development (Chapter 13). In P. Ruffino (Ed.), Independent videogames: Cultures, networks, techniques and politics (pp. 209–222). Routledge.

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Broadcasting ourselves (Chapter 1). In Watch me play: Twitch and the rise of game live streaming (pp. 1–23). Princeton University Press.

0 notes