#Project Prometheus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

YURI ART FOR TWO DISASTER GAYSSSS

GO READ PROJECT PROMETHUS OVER ON SV RRRAAAAAAHHHH

IT'S SUPER NICE AND YOU WON'T REGRET ITTTTTT

#Yuri#sufficient velocity#SV#Quest#Project Prometheus#Super Hero#Super heroes#Not my characters#GO READ THIS RAAAAAAH

1 note

·

View note

Text

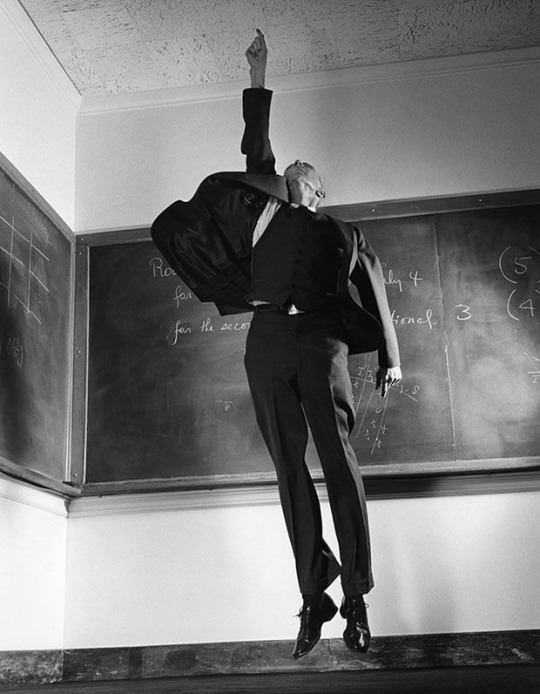

Today I discovered a mid-century photographer called Philippe Halsman who photographed the famous people of his era, from Richard Nixon to Marilyn Monroe. At the end of his sessions he would ask the person to jump into the air for a picture, believing that this would cause them to drop their pretenses and public persona, leaving him with a picture of the real person as they made their leap. He called this ‘jumpology’.

This is the photo he took of Robert Oppenheimer in 1958, possibly the most free and unreserved image of him that I’ve ever seen.

#oppenheimer#american prometheus#1950s#cillian murphy x reader#cillian murphy#oppenheimer x reader#christopher nolan#peaky blinders#tommy shelby#tommy shelby x reader#j robert oppenheimer#history#world war two#manhattan project#philippe halsman#photography

620 notes

·

View notes

Text

horizon forbidden west | patterns & effects 5/?

#horizon forbidden west#hfw#hfw patterns#found some circular things in The Folder and thought i'd throw them together for this “series” that i have#the first one is a scrounger doing one of their super annoying attacks#then a resonator target‚ the globe projection in burning shores‚ and a piece of some sons of prometheus gear in breached rock#i think

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

bele sanje

#joker out#joker out fanart#untitled joker out discography project#song rec#2024#the metaphors here got so out of hand i feel like a pretentious fuck#prometheus mentions make me go crazy always AND what if hold on hold on WHAT IF misery loves company#visions so incomprehensible i wanna forget how i got here#in my defence i listened to a lot of mgk lately <----- red flag#and btw only novi val (and okay sbj when i listen to it) left

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

#this is a part of a project I want to do#but I’m posting it so I won’t seem inactive#alien#alien fanart#prometheus#david 8#elizabeth shaw#David 8 fanart

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gemini, the sign of the twins is ruled by Mercury, the planet of all cerebral regions of the brain. Intellect, thought, logic, reasoning, communication, analysis. It is a planet associated with the divine Promethean man that brings great knowledge from Heaven for the sake of mankind out of his abjection at the gods' hoarding of it from mortals. This knowledge he brought was in the form of fire, which has a curious analogy in Vedic astrology with the right half of Gemini that is part of the Ardra nakshatra (constellation), which is ruled by the three-eyed god Rudra who wears a horned headdress. Its governing planet is Rahu, the head of an ancient serpent demon that is allied with the powers of Saturn in their eternal war against the sun god Surya and the other gods who hoarded knowledge from mortals.

#bit of a detour from my tarot project#but this was a good write that ran itself through my mind#and I wanted to share#TROP#The Rings of Power#Rings of Power#LOTR#Lord of the Rings#The Lord of the Rings#Annatar#Mairon#Sauron#Charlie Vickers#mine#my edit#Prometheus#Gemini#Mercury

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

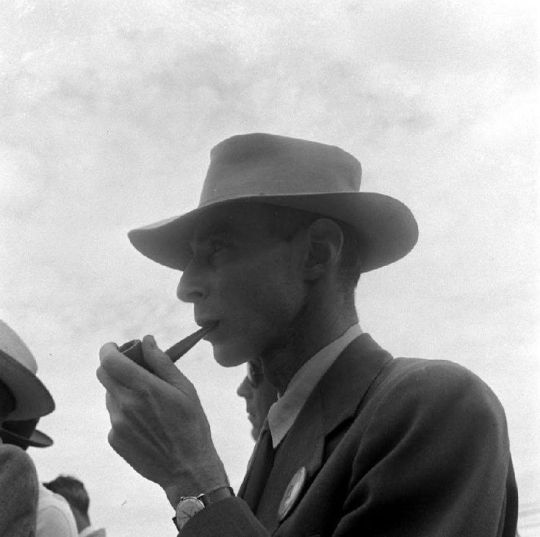

Happy birthday to Robert Oppenheimer who would be 120 today!

22/04/1904

#j robert oppenheimer#oppenheimer#oppie#robert oppenheimer#american prometheus#los alamos#manhattan project#history

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mass Effect - Legendary Edition

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just saw Oppenheimer and I was a bit disappointed with how they portrayed Truman. He came across pretty poorly IMO. It was only one scene but I wondered what you thought.

I understand your disappointment and it certainly wasn't a very in-depth portrayal of Truman, but according to the book that the movie was largely based on -- American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO) -- the meeting that Oppenheimer had with President Truman went down pretty much as depicted in the film.

As Bird and Sherwin write in American Prometheus:

(O)n October 25, 1945, Oppenheimer was ushered into the Oval Office. President Truman was naturally curious to meet the celebrated physicist, whom he knew by reputation to be an eloquent and charismatic figure. After being introduced by Secretary [of War Robert P.] Patterson, the only other individual in the room, the three men sat down. By one account, Truman opened the conversation by asking for Oppenheimer's help in getting Congress to pass the May-Johnson bill, giving the Army permanent control over atomic energy. "The first thing is to define the national problem," Truman said, "then the international." Oppenheimer let an uncomfortably long silence pass and then said, haltingly, "Perhaps it would be best first to define the international problem." He meant, of course, that the first imperative was to stop the spread of these weapons by placing international controls over all atomic technology. At one point in their conversation, Truman suddenly asked him to guess when the Russians would develop their own atomic bomb. When Oppie replied that he did not know, Truman confidently said he knew the answer: "Never." For Oppenheimer, such foolishness was proof of Truman's limitations. The "incomprehension it showed just knocked the heart out of him," recalled Willie Higinbotham. As for Truman, a man who compensated for his insecurities with calculated displays of decisiveness, Oppenheimer seemed maddeningly tentative, obscure -- and cheerless. Finally, sensing that the President was not comprehending the deadly urgency of his message, Oppenheimer nervously wrung his hands and uttered another of those regrettable remarks that he characteristically made under pressure. "Mr. President," he said quietly, "I feel I have blood on my hands." The comment angered Truman. He later informed David Lilienthal, "I told him the blood was on my hands -- to let me worry about that." But over the years, Truman embellished the story. By one account, he replied, "Never mind, it'll all come out in the wash." In yet another version, he pulled his handkerchief from his breast pocket and offered it to Oppenheimer, saying, "Well, here, would you like to wipe your hands?" An awkward silence followed this exchange, and then Truman stood up to signal that the meeting was over. The two men shook hands, and Truman reportedly said, "Don't worry, we're going to work something out, and you're going to help us." Afterwards, the President was heard to mutter, "Blood on his hands, dammit, he hasn't half as much blood on his hands as I have. You just don't go around bellyaching about it." He later told [Secretary of State] Dean Acheson, "I don't want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again." Even in May 1946, the encounter still vivid in his mind, he wrote Acheson and described Oppenheimer as a "cry-baby scientist" who had come to "my office some five or six months ago and spent most of his time wringing his hands and telling me they had blood on them because of the discovery of atomic energy."

#Oppenheimer#History#Oppenheimer Film#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Harry S. Truman#President Truman#Truman Administration#Atomic Bomb#Manhattan Project#Trinity Test#Oppenheimer Movie#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#Gary Oldman#American Prometheus#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Nuclear Weapons#World War II

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started the famous J. Robert Oppenheimer biography yesterday, the one that took thirty years to write and won the Pulitzer Prize. Here’s a few discoveries so far:

• His absolute favourite book as an adolescent was, impressively i think, George Eliot’s Middlemarch

• His father met his mother at an art gallery in New York and he fell instantly in love with her; we’re given a sample of their love letters and I must admit … (sniff). So that’s nice; though it’s curious to think how one of the fundamental precursors of The Manhattan Project has a direct common ancestry to fine art.

• He grew up with an unbelievable collection of artwork around him at his home, including a Rembrandt sketch, several Van Goghs and Cézannes.

• At twelve years old he corresponded regularly with leading geologists in the States; after a time, not knowing his age, several of them nominated his membership into the Geological Society and invited him to give the traditional inaugural lecture. When he arrived everyone rolled about with laughter (at their own foolishness, it seems) and amazement at his precocity. They found a box for him to stand on at the dais and little Oppenheimer gave, to all accounts, a fine lecture.

#j robert oppenheimer#middlemarch#george eliot#van gogh#rembrandt#paul cezzane#oppenheimer#american prometheus#personal notes#fine art#the manhattan project#n.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

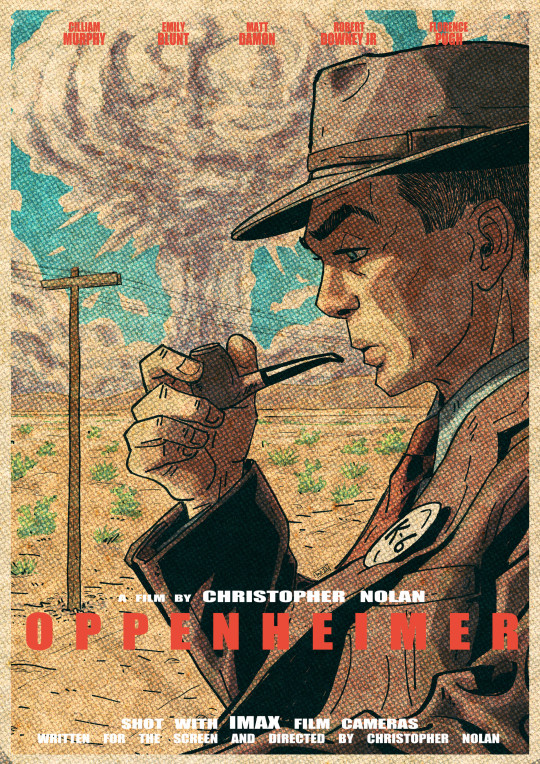

Pop art-like Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer. Thanks for Wagner Diesel on Artstation.

#oppenheimer#art#atomic bomb#fanart#history of science#manhattan project#oppenheimer fanart#physics#us history#digital art#retro aesthetic#pop art#vintage postcards#film poster#cillian murphy#christopher nolan#american prometheus#fandom#character design#christmas

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

the thing about prometheus's Little Situationship with yi ha-neul is that they're a lot more like a Greek Tragedy kind of thing. If you could call them that. But also Weird

#yi ha-neul keeping all of the records about them to himself and vowing to no longer allowing anyone to talk about them in bad faith#for they are His memory to keep.#prometheus when they are no longer something recognizable nor they can communicate with that other person#so they have replaced him with someone else. And project his image onto that person.#so whenever this “replacement” acts out of place or something not ha-neul would do. they'd correct him. Until he Does.#jesus christ y'all two are Fucked Up abour each other actually.#yomo ocs?!#oc: ephai#oc: yi ha-neul

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Possibly my favourite photograph of Oppie that I have found to date, at home with his son and taken for an edition of Life Magazine in 1949 by Alfred Eisenstaedt, of which he was on the front cover. He just seems so normal here, interacting with his son like any father would, it’s very humanising. Pictures like this are what remind us that historical figures were real people, not just mystical figures of the past that we find in textbooks.

#1950s#oppenheimer#american prometheus#cillian murphy#oppenheimer x reader#christopher nolan#cillian murphy x reader#life magazine#alfred eisenstaedt#photography#j robert oppenheimer#j robert oppenheimer x reader#family life#world war two#atomic bomb#manhattan project

191 notes

·

View notes

Note

Incorrect Quotes for the TFA X Poppy Playtime Crossover

(Fanzone and the others are squatting off against Meltdown)

Fanzone: What do you even want from this place Black!

Meltdown: What was owed to me all those years ago, when I was stuck as a lowly intern for this company.

Fanzone: You...worked here?

Meltdown: Yes, but unlike you I wasn't some no name worker but a member that worked hand and hand to innovate this company and eventually the future of mankind! The Bigger Body Initiative would have changed the world!

Fanzone: Wait! You knew about the experiments?!😨

Meltdown: I worked closely with the former Dr. Harely Sawyer. Truly a pioneer of his time, someone I could admire. But fir all his brilliance he selfishly kept the secret of his procedures to himself! Not even sharing them with his most loyal coworkers! 😤

Fanzone: You Sick Freak! THOSE WERE CHILDREN YOU WERE WORKING ON!😡

Meltdown: They were orphans, abandoned by the world already. They were useless to society. But our work gave them the chance to be part of a cure. To be of use. That is science😈

Oh trust me when I say Fanzone wanted to punch him if he could. This made the mission even more personal knowing he had a hand in this nightmare. Fanzone wasn't going to let Meltdown get away no matter what.

#sonicasura#sonicasura answers#asks#cf8wrk4u us#maccadam#transformers#transformers series#transformers animated#tf#tf series#tfa#carmine fanzone#captain fanzone#prometheus black#tfa meltdown#meltdown#poppy playtime#ppt#project playtime

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The key word in Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is “compartmentalization.” It’s a security strategy, introduced and repeatedly enforced by Col. Leslie R. Groves (Matt Damon) in his capacity as director of the Manhattan Project, which is racing to build a weapon mighty enough to bring World War II to an end. In Groves’ mind, keeping his various teams walled off from one another will help ensure the strictest secrecy. But J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the brilliant theoretical physicist he’s hired to run the project laboratory in Los Alamos, N.M., knows that compartmentalization has its limits. The success of their mission will hinge not on isolation but on an extraordinary collaborative synthesis — of physics and chemistry, theory and practice, science and the military, the professional and the personal.

In the weeks since “Oppenheimer” opened to much critical acclaim and commercial success, Groves’ key word has taken on an unsettling new meaning. Compartmentalization, after all, is a pretty good synonym for rationalization, the act of setting aside, or even tucking away, whatever we find morally troubling. And for its toughest critics, many of them interviewed for a recent Times piece by Emily Zemler, “Oppenheimer” compartmentalizes to an outrageous degree: In not depicting the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they argue, the movie submits to a historical blindness that it risks passing on to its audience. Nolan, known for crafting fastidiously well-organized narratives in which nothing appears by accident, has been taken to task for what he chooses not to show.

Most of those decisions, of course, flow directly from his source material, “American Prometheus,” Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s authoritative 2005 Oppenheimer biography. With the exception of one key narrative thread, everything onscreen is framed, per biopic convention, through its subject’s eyes. And so you see Oppenheimer as an excitable young physics student, and you behold his eerie, captivating visions of the subatomic world. You see him become one of America’s leading physicists, take a major role in the secret race to the A-bomb and, together with his recruits, devise and build the world’s first nuclear weapons. You see his shock and awe when the Trinity test proves successful, lighting up the desert sky and landscape with a blinding flash of white and a 40,000-foot pillar of fire and smoke.

What you don’t see — because Oppenheimer doesn’t see them either — are the bomb’s first victims: the thousands of New Mexicans, most of them Native American and Hispanic, who dwell within a 50-mile radius of the Trinity test site and whose exposure to radiation will have deadly health consequences for generations. You don’t see the bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; you don’t see the lethal conflagrations and ash-covered rubble, and you don’t see the bodies of Japanese victims burned beyond recognition, or hear the screams and wails of survivors. (Estimates place the eventual death toll at close to 200,000.)

In refusing to visualize these horrors, is Nolan showing admirable dramatic restraint or committing unforgivable sins of omission? Is he merely sticking to his subject’s perspective or conveniently dodging the kind of imagery that would trouble Oppenheimer’s conscience?

As it happens, the scientist does in fact see that imagery, and his conscience is duly troubled. In one key scene, the camera studies Oppenheimer and his colleagues as they watch disturbing footage of the bombings’ aftermath. An offscreen speaker describes how thousands of Japanese civilians were incinerated in an instant, while thousands more died excruciating deaths from radiation poisoning. You see Oppenheimer recoil, even if what he recoils from is left pointedly out of frame.

These are not the only images of WWII that the movie withholds. It’s a measure of the formal and structural rigor of “Oppenheimer” that we see nothing of the Pacific theater conflict, and nothing of the European theater conflict, either — not even when Oppenheimer fears that the Nazis might be building a nuclear weapon of their own. Nolan, who always trusts us to keep up with his elaborately constructed puzzle-box narratives, also trusts us to know a thing or two about history. And crucially, he wants to open up a different perspective on the war, to show how some of its most crucial tactics and maneuvers played out not on battlefields but in classrooms and laboratories — and, finally, in the theater of Oppenheimer’s mind.

We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure.

It’s a brilliant mind, to say the least. It’s also ill prepared for the terrifying, world-altering reality that it ushers into being. Oppenheimer may see footage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but images are a poor substitute for reality; he will never walk among the ruins, witness the despair of the survivors or behold the devastation up close. Nolan knows that we can’t either. What’s more, he clearly believes that we shouldn’t be able to.

Seen in this light, the director’s refusal to thrust his camera onto Japanese soil, far from being an act of historical vagueness or obliviousness, instead represents a carefully thought-out, rigorously executed solution to the problem of how to represent history. And his solution speaks not to his insensitivity but his integrity, his refusal to exploit or trivialize Japanese suffering by re-enacting it for the camera. Nolan lays the groundwork in one of his most revealing scenes, shortly before the decision is made to target Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As Oppenheimer looks on, U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (James Remar) removes Kyoto from the list of potential targets, citing the city’s cultural and historical significance and fondly recalling that he and his wife honeymooned there years earlier.

Before the bombings have even taken place, Nolan, in this one scene, indicts the arbitrary callousness of a U.S. war machine that cloaks its destructive intentions in cultural high-mindedness and rank sentimentality. It’s an appalling moment, and Stimson unambiguously solicits Oppenheimer’s contempt as well as the viewer’s; watch that scene in a packed house and you’ll hear the audience scoff as one. You might also begin to suspect, if you haven’t already, that Nolan isn’t going to dramatize the bombings in straightforward fashion, if he means to dramatize them at all.

Nolan has never been turned on by spectacles of violence. Even “Dunkirk,” a harrowing if ultimately optimistic World War II bookend of sorts to “Oppenheimer’s” apocalyptic despair, is a combat picture far more driven by ideas than by carnage. Violence certainly plays its part in Nolan’s movies, but seldom is it an end in itself. Reviewing “Oppenheimer” in the New York Times, Manohla Dargis noted, “There are no documentary images of the dead or panoramas of cities in ashes, decisions that read as [Nolan’s] ethical absolutes.” And in a recent Decider essay, the critic Glenn Kenny shrewdly examined “Oppenheimer” alongside Alain Resnais’ elliptical 1959 masterpiece, “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” itself a powerful commentary on the futility of trying to represent the unrepresentable. “Had Nolan chosen to somehow ‘recreate’ the bombing of Hiroshima,” Kenny writes, “we, the viewers, would really see nothing.”

Japanese filmmakers, of course, have been powerfully evoking and re-creating the bombings for decades: Kaneto Shindo’s “Children of Hiroshima” (1952) and especially Shohei Imamura’s devastating “Black Rain” (1989) are just two well-known examples. Over the past few weeks, social media users have circulated clips of Mori Masaki’s 1983 anime “Barefoot Gen,” an adaptation of Keiji Nakazawa’s manga series of the same title. It contains what is surely one of the cinema’s most upsetting, unsparingly graphic depictions of the atomic blast and its casualties. It’s one of several animated films, including Renzo and Sayoko Kinoshita’s 1978 short “Pica-don” and Sunao Katabuchi’s “In This Corner of the World” (2016), that have confronted the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with a boldness and artistry that live-action cinema can be hard-pressed to match.

Much of this evidence has been marshaled in Nolan’s defense: Surely this is Japan’s story to tell, not his. I’m reluctant to embrace that particular stay-in-your-lane logic, which is ultimately deadening to the cause of art and empathy. As Clint Eastwood demonstrated in “Letters From Iwo Jima,” it is not beyond a white Hollywood filmmaker’s ability to enter persuasively and movingly into the mindset of a wartime enemy. Even so, that clearly isn’t the story Nolan is telling. And with such a wealth and variety of Japanese fiction and nonfiction filmmaking on the atomic bombings already, why should “Oppenheimer” bear the responsibility of representing events and experiences that fall outside its subject’s perspective?

Some would rebut that “Oppenheimer,” being a Hollywood blockbuster with serious global reach (whether it will play Japanese theaters remains uncertain), will be many audiences’ only exposure to the events in question and thus might “create a limit on public consciousness and concern,” as the poet, writer and professor Brandon Shimoda told The Times. A corollary of this argument: The crimes committed against the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were so unspeakable, so outsized in their impact, that Oppenheimer’s perspective does and should dwindle into insignificance by comparison. For Nolan to focus so exclusively on an American physicist’s story, some insist, ultimately diminishes history and humanity, even as it reinforces the Hollywood hegemony of the great-man biopic and of white men’s narratives in general.

I get those complaints. I also think they betray an inherent disrespect for the audience’s intelligence and curiosity, as well as a fundamental misunderstanding of how movies operate. It’s telling that few of these criticisms of perspective were leveled at “American Prometheus” when it was published in 2005, that no one begrudged Bird and Sherwin for offering a meticulously researched, morally ambivalent portrait of their subject’s life and consigning the destruction of two Japanese cities to a few pages. That’s because books are books, the argument goes, and movies are movies — and this perceived difference, it must be said, reveals a pernicious double standard.

Because they seldom achieve the narrative penetration and richness of detail of, say, a 700-page biography, movies, especially those about history, often are hailed as achievements of breadth over depth, emotion over intellect. They are assumed to be fundamentally shallow experiences, distillations of real life rather than sharply angled explorations of it, propelled by broad brushstrokes and easy expository shortcuts, and beholden to the audience’s presumably voracious appetite for thrilling, traumatizing spectacle. And because movies offer a visual immediacy and narrative immersion that books don’t, they are expected to be sweeping if not omniscient in their narrative scope, to reach for a comprehensive, even definitive vantage.

Movies that attempt something different, that recognize that less can indeed be more, are thus easily taken to task. “It’s so subjective!” and “It omits a crucial P.O.V.!” are assumed to be substantive criticisms rather than essentially value-neutral statements. We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure. But because viewers of course cannot be trusted to know any history or muster any empathy on their own — and if anything unites those who criticize “Oppenheimer” on representational grounds, it’s their reflexive assumption of the audience’s stupidity — anything that isn’t explicitly shown onscreen is denigrated as a dodge or an oversight, rather than a carefully considered decision.

A film like “Oppenheimer” offers a welcome challenge to these assumptions. Like nearly all Nolan’s movies, from “Memento” to “Dunkirk,” it’s a crafty exercise in radical subjectivity and narrative misdirection, in which the most significant subjects — lost memories, lost time, lost loves — often are invisible and all the more powerful for it. We can certainly imagine a version of “Oppenheimer” that tossed in a few startling but desultory minutes of Japanese destruction footage. Such a version might have flirted with kitsch, but it might well have satisfied the representational completists in the audience. It also would have reduced Hiroshima and Nagasaki to a piddling afterthought; Nolan treats them instead as a profound absence, an indictment by silence.

That’s true even in one of the movie’s most powerful and contested sequences. Not long after news of Hiroshima’s destruction arrives, Oppenheimer gives a would-be-triumphant speech to a euphoric Los Alamos crowd, only for his words to turn to dust in his mouth. For a moment, Nolan abandons realism altogether — but not, crucially, Oppenheimer’s perspective — to embrace a hallucinatory horror-movie expressionism. A piercing scream erupts in the crowd; a woman’s face crumples and flutters, like a paper mask about to disintegrate. The crowd is there and then suddenly, with much sonic rumbling, image blurring and an obliterating flash of white light, it is not.

For “Oppenheimer’s” detractors, this sequence constitutes its most grievous act of erasure: Even in the movie’s one evocation of nuclear disaster, the true victims have been obscured and whitewashed. The absence of Japanese faces and bodies in these visions is indeed striking. It’s also consistent with Nolan’s strict representational parameters, and it produces a tension, even a contradiction, that the movie wants us to recognize and wrestle with. Is Oppenheimer trying (and failing) to imagine the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians murdered by the weapon he devised? Or is he envisioning some hypothetical doomsday scenario still to come?

I think the answer is a blur of both, and also something more: In this moment, one of the movie’s most abstract, Nolan advances a longer view of his protagonist’s history and his future. Oppenheimer’s blindness to Japanese victims and survivors foreshadows his own stubborn inability to confront the consequences of his actions in years to come. He will speak out against nuclear weaponry, but he will never apologize for the atomic bombings of Japan — not even when he visits Tokyo and Osaka in 1960 and is questioned by a reporter about his perspective now. “I do not think coming to Japan changed my sense of anguish about my part in this whole piece of history,” he will respond. “Nor has it fully made me regret my responsibility for the technical success of the enterprise.”

Talk about compartmentalization. That episode, by the way, doesn’t find its way into “Oppenheimer,” which knows better than to offer itself up as the last word on anything. To the end, Nolan trusts us to seek out and think about history for ourselves. If we elect not to, that’s on us.'

#Christopher Nolan#Oppenheimer#Leslie Groves#Matt Damon#Cillian Murphy#Los Alamos#The Manhattan Project#Hiroshima#Nagasaki#American Prometheus#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Hiroshima Mon Amour#Dunkirk#Letters from Iwo Jima#Clint Eastwood

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mythology character sheets,Euridyce,Orpheus and Prometheus,working on a render,a portrait,a flat model and some emotions

#myart#my design#character sheet#greek mythology#prometheus#orpheus and euridyce#doing it while working was hard as hell#last moment project but done

29 notes

·

View notes