#Pytheas

Photo

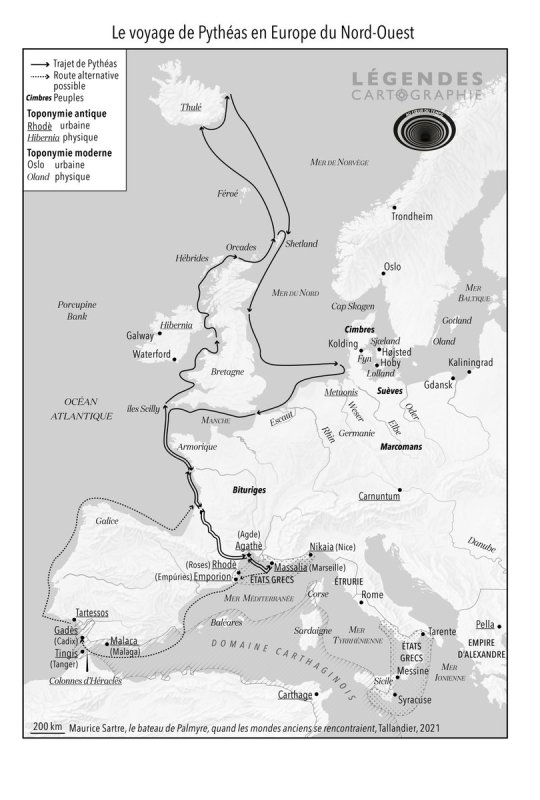

The voyage of Pytheas, 4th century BC.

by LegendesCarto

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Travel Question 17: The Library of Alexandria (Miscellaneous Edition)

I welcome your suggestions for both Library of Alexandria and other lost works of World Literature and History, as there will be future polls.

#Time Travel#Library of Alexandria#Euripides#The Twelve Tables#Ancient Egypt#The Sibylline Books#Stesichorus#Lycophron#Xenocles#Mark Antony#Pytheas#Ctesias#Tacitus

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Talking about stupid retcons that I will never accept, (I dont care that it has been over a decade at this point)

Sicarius name being changes to Captain Pythea in the book Consequences because he acts like a big bag of dicks and we cant have the big Hero™ do that.

Let the hero be a dick GW! Let McNeill write his enemies to lovers in peace you cowards!

(has this stopped me from buying models/books/merch or enjoying the hobby in any way? No. I fucking love this hobby, even when it wrongs me like this)

#40k#warhammer 40k#warhammer#ultramarines#space marines#stupid sexy space marines#graham mcneill you crazy bastard#uriel ventris#cato sicarius#retcons#pythea is just sicarius in a silly moustache

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

thirteen and yaz deserve to have an exchange like in fear her when ten puts his hand into a stranger's jam jar and rose is like no...

#lifeblogs#doctor who#actually i'm going to say something and i need like the two of you who will get it to appreciate it#a doctor/companion relationship is like simmea and pytheas just city#and it is like this because of autism but also the general vibe of one person doesn't know how to be human#thasmin

129 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fun fact please?

Alright friend I'm sorry it took me so long, but my computer was throwing a fit and I couldn't get to this as quickly as I wanted. I apologize.

So Today You Learned about Pytheas of Massalia.

Pytheas was a Greek geographer and explorer from the 300's BC. Okay, well sort of--Massalia was a Greek colony in what is now France (Marseille, in fact), but the man was a Greek. His accounts were widely known in his own times, but sadly, they haven't survived into the modern day. Like many ancient texts that were famous, we have excerpts, and we have other authors referring to the things he'd written, so we have an idea of what he saw and talked about.

Also, he discovered Britain.

I mean, kind of. There were already people living there, obviously, but they weren't really known to the Greek world. You have to understand that the Romans considered the British Isles, like, the furthest edge of the known world, so hundreds of years before that the Greeks didn't even think of that as a place, though they had legends about distant lands. But he went there, apparently talked to people there, and brought back descriptions as well as complained about the cold weather.

His first written reference to Scotland calls it 'Orcas', from which we get the name of the Orkney Islands off the northern coast of Scotland.

Pytheas also described Thule, a place far to the north, which has been warped into being a lot of weird things by people over the ages. We're not clear what he meant. If this was Scotland, an island north of Scotland, Iceland, Scandanavia... unclear.

He also discovered the Baltic Sea for the Greco-Roman world, interacted with the Germanic peoples there as well. He went far enough north that he's the first recorded writer to mention the midnight sun and polar ice.

[Again, there were legends in Greece about frozen northern lands at this point, so presumably someone had been up there before him, but they were that--legends. Pytheas actually went and checked it out.]

Also! He made the connection between the tides and the phases of the Moon, the first scholar we know of to do so.

I don't know, maybe this sounds boring to you, and if it does, I'm sorry. But this blows my mind that in an ancient Greek colony, a time that we mostly think of as insular and not really interacting with the outside world, at least, not outside the Mediterranean, some guy hopped on a ship and started discovering different parts of the world, completely alien to his own home temperature and culture. And he hopped off the boats and talked to some of these people, trying to get a feel for what their lives were like. In the 300's B.C. And that these records were famous in their own day, but this isn't something that comes up in your history classes now (which isn't a complaint, I don't know how to work it into the curriculum).

And he's got this dope statue in Marseille:

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

i read information. then i remember this information for 5 minutes. then i forgot information.

is this how it's supposed to work?

#but i still remember everything about a character that was my interest in 7th grade. like. i can show you quotes about him in books...#i haven't read these books in 5 years but i can still show you the quotes with closed eyes...#it bothers me. IT FUCKING BOTHERS ME.#my brain is so fucked up oh#i finished reading a chapter about the arctic exploration in antiquity after pytheas#and like i literally made notes#BUT I DON'T REMEMBER ANYTHING#im really bad with scientific information i only remember things if they were told in most stupid way possible#like they goes a well written passage and me taking notes like: he had atlas with maps. they're the only ones that survive.#i hate my brain#even when i write essays i need to THINK because i hate writing serious things and like my brain is not capable of doing that#i am a silly little creature#like. i love science. i love history. i love literature. but it is so fucking hard to remember things...#i still remember the. whole plot of that young adult fantasy novel ive read 2 years ago#but I HAVE NO IDEA what was written in a historic book I've read 2 months ago#what's the fucking problem???

1 note

·

View note

Text

Le Voyage de Pythéas Hermès Carré GRAIL

View On WordPress

#Aline Honore#carre de paris#grail hermes scarf#Le Voyage de Pythéas Hermès Carré is a Special Issue#Le Voyage de Pytheas Hermes scarf

0 notes

Text

Legends and myths about trees

Forest myths, Estonian traditional beliefs (3)

The world of the Estonians’ ancestors – Kaali crater, the place where "The sun went to rest"

Kaali is a group of nine meteorite craters in the village of Kaali on the Estonian island of Saaremaa. It was created by an impact event. The largest crater is 110 m (360 ft) in diameter and forms a small lake named Lake Kaali.

The impact is thought to have happened in the Holocene period, around 3,500 years ago. The estimates of the age of the Kaali impact structure provided by different authors vary by as much as 6,000 years, ranging from ~6,400 to ~400 years before current era (BCE). According to the theory of more recent impact, Estonia at the time of impact was in the Nordic Bronze Age and the site was forested with a small human population. The impact energy of about 80 TJ (20 kilotons of TNT) is comparable with that of the Hiroshima bomb blast. It incinerated forests within a six km (3.7 mi) radius.

The event figured prominently in regional mythology. It was, and still is, considered a sacred lake. There is archaeological evidence that it may well have been a place of ritual sacrifice.

It is possible that Saaremaa was the legendary Thule island, first mentioned by ancient Greek geographer Pytheas, whereas the name "Thule" could have been connected to the Finnic word tule ("(of) fire") and the folklore of Estonia, which depicts the birth of the crater lake in Kaali. Kaali was considered the place where "The sun went to rest."

[Image below: the crater as viewed from near the rim]

森の神話・エストニアの民間伝承 (2)

エストニア人の祖先の世界 〜 "太陽が休息する場所 "、カーリー・クレーター

カーリ・クレーターは、エストニアのサーレマー島にある9個の隕石クレーター群である。このクレーター (噴火口) は衝突現象によって形成されたものでである。最も大きいクレーターは直径110mでカーリ湖という名の小さな湖になっている。

この衝突は完新世、およそ3,500年前に起こったと考えられている。カーリ衝突構造の推定年代は、著者によって6,000年も異なっており、現在の時代 (紀元前) より6,400年前から400年前までである。より最近の衝突説によれば、衝突当時のエストニアは北欧青銅器時代で、この地は森林に覆われ、小規模な人間しか住んでいなかった。約80TJ (TNT20キロトン)という衝撃エネルギーは、広島原爆の爆風に匹敵する。半径6km (3.7マイル) の森林を焼却した。

この出来事は、この地域の神話において重要な位置を占めている。昔も今も、この湖は神聖な湖と考えられている。儀式の生贄の場所であった可能性を示す考古学的証拠もある。

サーレマー島は古代ギリシャの地理学者ピュテアスが最初に言及した伝説上のトゥーレ島であった可能性があり、一方、「トゥーレ」という名前はバルト・フィン諸語のトゥーレ (“火の”の意) や、カーリにある火口湖の誕生を描いたエストニアの民間伝承と結びついている可能性がある。カーリは "太陽が休息する場所 "と考えられていた。

#trees#tree legend#tree myth#kaali#saaremaa#estonia#estonian mythology#kaali crater#impact event#tule#nature#art#mythology#legend#folklore

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

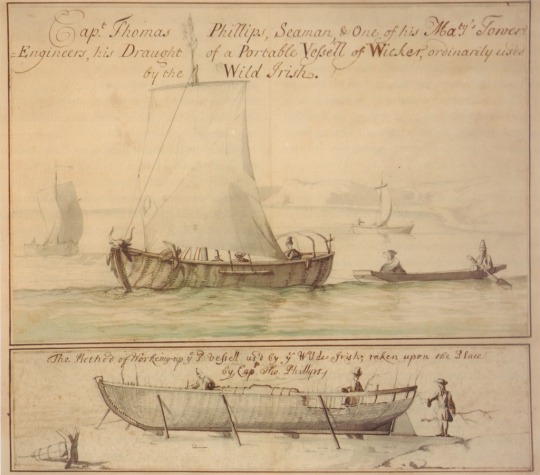

The Irish Currach

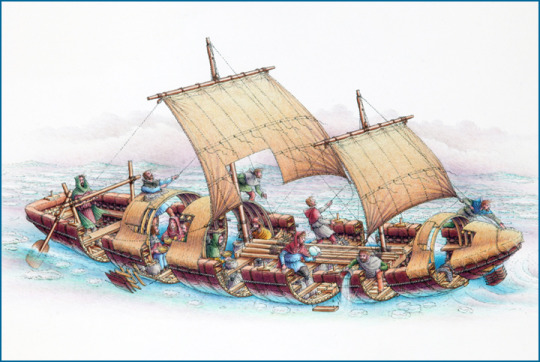

The currach is a traditional Irish boat built from a light wooden frame covered with tarred leather or canvas. They were usually 4.80 to 5.50 m long and slightly less than 1 m wide. Depending on the purpose for which they were built and where they were built, they could be seaworthy with a keel and sail or flat as a river or coastal vessel. It is not known exactly when they first appeared on the coasts of Ireland, but they seem to have been around since the Neolithic period.

A modern Kerry currach

Used for fishing or transport, they could also be used for other purposes. Pytheas of Massalia is said to have used one around 340 BC during his exploration of north-western Europe. Whether he actually did so is questionable, since his account of the voyage has been lost and other ancient authors like to portray him as a liar and label his observations as fictitious. Today's researchers, however, believe him to a large extent.

Pytheas on his voyage to Thule in 340 BC, by Stephen Biesty 2011

In chapter 4 of the Navigatio Sancti Brendani, the author describes how St Brendan and his monks built a curragh for the planned sea voyage in 565 and 573 AD across the open sea to the "Isle of the Blessed". The material is described in detail: resin-soaked ox hides tanned in oak tan for the covering, ash wood for the frames and oak wood for gunwale, oars, oars and mast, all made waterproof with (sheep) fat. Then a hull was constructed from longitudinal and transverse frames joined with leather strips, the skins pulled over them and sewn together with flax fibre threads. Oars, mast, leather straps (for the shrouds and sheets), leather sails, as well as spare skins, woods and grease completed the equipment.

Book illustration Manuscriptum translationis germanicae Cod. Pal. Germ. 60, fol. 179v (University Library of Heidelberg, Germany), written around 1460 AD. St. Brendan in a currach.

A similarly constructed boat is described in the mythical tales Immram Curaig Maíle Dúin ("The Voyage of the Boat of Máel Dúin") from the 10th century and Immram Brain ("Bran's Voyage") from the 8th century.

The currach survives to this day and caused quite a stir in the 17th century when an attempt was made to recreate a seagoing one. Captain Thomas Phillips, described and drew it as follows: "A portable vessel made of wicker, commonly used by the wild Irish". The ocean-going vessel is about 6m long, has a keel and rudder, a ribbed hull and a mast in the middle of the vessel. Because of the keel, the ship is built from the bottom up. A fairing (probably made of animal skins) was added, with the sides supported by poles in the gaps.

The mast is supported by stays and double shrouds on each side, the latter sloping down to an outer plank which serves as a chain stay. The forestay runs over a small fork above the yard, which carries a square sail: a branch is tied to the top of the mast. The stern is topped by double half-rings which could support a cover.

Captain Thomas Phillips - Currach, 17th century

Phillips' sketches suggest that such a vessel was by all means common in his time and probably in use earlier. The keel would improve the handling of the boat, but the hull would remain flexible.

A modern Donegal Sea Currach

Today's currachs are sturdy, light and versatile vessels. Their framework consists of a truss formed by frames and stringers and surmounted by a gunwale. There is a stem and stern post, but no keel. For this it is rowed but can also have a mast and sail, but with a minimum of rigging. The outside of the hull is covered with tarred canvas or calico, a substitute for animal skin. They are used for, recreation, fishing, ferries and for transporting goods and livestock, including sheep and cattle.

#naval history#ship types#currach#irish vessel#boat type#ancient seafaring#age of sail#age of steam#modern

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

really loved the the sargasso sea bits in that seaweed book

"Earlier in history, sailors had already reported extensive, unmanageable amounts of Sargassum and similar entanglements. In twelfth-century scholarly texts written by Western Europeans, frequent mention was made of the dangerous lever zee, also referred to as the mare coagulatum or ‘curdled sea’. Finding oneself in the curdled sea was one of the greatest fears of seafarers in the Middle Ages. Algae would wrap themselves around the rudder, rendering ships unsteerable and uncontrollably adrift. Most captains avoided the sea even though they did not know its exact location.

The Greek geographer and historian Strabo (c. 63 BC–c. AD 24) quotes Pytheas of Marseilles, who allegedly said:

In the northern area is neither land, nor water, nor air, but a mixture of these, similar to a marine lung in which land and sea and all things are suspended, and this mixture is as if it were a fetter of the whole existing in a form impassable by foot or ship: an immobile sea.

In his fourth-century poem Ora Maritima, Rufius Festus Avienus describes a congealed sea in which the Carthaginian explorer Himilco gets stuck, around 525 BC, on a journey through the Atlantic Ocean. It took Himilco four months to get out again:

No breezes propel a craft, the sluggish liquid of the lazy sea is so at a standstill. He also adds this: A lot of seaweed floats in the water and often after the manner of a thicket holds the prow back. He says that here nonetheless the depth of the water does not extend much and the bottom is barely covered over with a little water. They always meet here and there monsters of the deep and beasts swim amid the slow and sluggishly crawling ships. Mist envelops sky and the surface of the sea like a cloak and the clouds are motionless in the thick sky."

sluggish sea and thick sky!! they make it sound like an entire landscape submerged in jelly. enchanting.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The voyage of Pytheas

by LegendesCarto

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

from my bookshelf

Pytheas of Massalia was a Greek geographer, explorer and astronomer from the ancient Greek colony of Massalia — modern-day Marseille, France. In the late 4th century BC, he voyaged from there to northwestern Europe, but his detailed account of it, On The Ocean, survives only in fragments, quoted — and disputed — by later authors such as Strabo, Pliny and Diodorus of Sicily. The Extraordinary Voyage Of Pytheas the Greek by the noted British historian of ancient maritime Europe, Barry Cunliffe, attempts to draw out the reality of what was an extraordinary sea journey, from the Western Mediterranean north along the Atlantic coast of Europe to the British Isles, then even further north, to the near-mythic land of Thule. Cunliffe makes a strong case for Pytheas being “the first European explorer”, while identifying the most likely locations of Thule, sought so avidly by 19th and early 20th century adventurers and artists.

James Hamilton-Paterson’s Seven-Tenths: The Sea And Its Thresholds, published in 1992, more than two thousand years after Pytheas’s On The Ocean, is an ambitious, expressive exploration of the vast aqueous wilderness that covers three-quarters of our planet by a writer of remarkable literary accomplishment (he was one of Martin Amis’s professors at Oxford). Plumbing humanity’s complex, multi-faceted relationship with the sea, Hamilton-Paterson writes vivid, meditative passages about, well, everything — fishing, piracy, oceanography, cartography, exploration, ecology, the ritual of a burials at sea, poetry, and even his own experiences living for extended periods on a small island in the Philippines.

Tom Neale’s autobiography, An Island To Oneself: Six Years On A Desert Island, describes an altogether smaller, more solitary world: the island of Anchorage, part of the Suwarrow Atoll in the South Pacific. Born in New Zealand in 1902, Neale spent most of his life in Oceania: after leaving the Royal New Zealand Navy, he worked for decades aboard inter-island trading vessels and in various temporary jobs ashore before his first glimpse of his desert island home. He moved to Anchorage in 1952 and over three different periods, lived in hermitic solitude for 16 years, with rare visits from yachtsmen, island traders, and journalists. Among the last was Noel Barber, a close friend of my late father: he gave my father a copy of Neale’s book, in Rome, shortly after it was published in 1966 (I still have it). Neale was taken off his beloved island in 1977 and died not long after of stomach cancer.

The Starship And The Canoe by Kenneth Brower, published in 1978, is an unlikely dual biography of a father and son that draws intriguing parallels between the ambitious ideas of renowned British theoretical physicist and mathematician Freeman Dyson — who, in the early 1970s explored concepts for interstellar travel, settlements on comets, and nuclear rockets that might propel mankind to the outer reaches of the universe — and his wayward son, George, who lived in a self-built tree house 30 metres up a Douglas fir overlooking the Strait Of Georgia, in British Columbia and devised large canoes based on Aleut baidarkas in which to paddle north to the wild, uninhabited littoral of southern Alaska. Brower’s descriptions of long passages with the younger Dyson in the cold, sometimes fierce tidal waters between Vancouver Island and the Canadian mainland are gripping and I have read them again and again. It is, unarguably, my favourite book.

The late, New Zealand-born doctor and sailor, David Lewis, is not as widely known as he was half a century ago, even by avid readers of sea stories, but from his earliest memoirs in the 1960s — of his participation in the first-ever singlehanded trans-Atlantic race (The Ship That would Not Sail Due West), and of incident-prone voyages to far-flung coasts with his young family (Dreamers of the Day, Daughters of the Wind, and Children Of Three Oceans) — to his practical, first-hand studies of instrument-less ocean navigation among South Pacific islanders, (We, The Navigators and The Voyaging Stars) in the 1970s, Dr. Lewis was not only the late 20th century’s most remarkable and intelligent writer on the sea and small-boat voyaging but also one of its most adventurous. My favourite of his several books: Ice Bird, published in 1972, an account of a gruelling, almost fatal voyage from Sydney, Australia, in an ill-prepared, steel, 32-foot yacht to achieve the first singlehanded circumnavigation of Antarctica.

It’s said that spending time anywhere with Lorenzo Ricciardi, late ex-husband of Italian photographer Mirella Ricciardi, was an adventure. A film-maker and former senior advertising executive, once described by a British writer as “a penniless Neapolitan count”, he gambled at roulette to raise enough money to buy an Arab dhow, which, in the 1970s, with little seafaring experience and plenty of mishaps, he sailed from Dubai to the Arabian Gulf, and from there down the Arabian to coast of Africa, where the dhow was shipwrecked among the Comoros Islands. The Voyage Of The Mir El Ah is Lorenzo’s picaresque account (illustrated by Mirella’s photographs). Astoundingly, several years later, Lorenzo and Mirella Ricciardi completed an even more dangerous, 6,000-kilometre voyage across Equatorial Africa in an open boat — and another book, African Rainbow: Across Africa By Boat.

Italian madmen aside, it used to be that you could rely on surfers for poor impulse control and reckless adventures, on the water and off. Back in the late 1990s, Allan Weisbecker sold his home, loaded his dog and a quiver of surfboards onto a truck, and drove south from the Mexican border into Central America to figure out what had happened to an old surfing buddy — in between checking out a few breaks along the way. In Search Of Captain Zero: A Surfer's Road Trip Beyond The End Of The Road is a memoir of a two-year road-trip that reads like a dope-fuelled fiction but feels more real than William Finnegan’s somewhat high-brow (and more successful) Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life.

Which brings me to Dana and Ginger Lamb. In 1933, these newly-weds would certainly have been looked at askance by most of their middle-American peers when they announced that they weren’t ready yet to settle down and instead built a 16-foot hybrid canoe-sailboat and set of on what would turn out to be a 16,000-mile, three year journey down the Pacific coasts of Mexico, Guatemala, Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica to the Panama Canal. Dana’s 415-page book, Enchanted Vagabonds, published in 1938, was an unexpected New York Times best-seller and today is more exciting to read than the ungainly, yawn-inducing books produced by so many, more commercially-minded, 21st century adventurers.

First published in Sirene, No. 17, Italy, 2023.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who doesn’t love to travel, but what about to destinations unknown? From Pytheas reaching the coasts of northern Europe to Magellan navigating the globe, the call of the unknown has pushed humans to explore, adventure and adapt to a new world. Some ancient voyages have truly changed the world.

#voyage#expedition#discovery#explorer#adventurer#Americas#Vikings#seafarers#Atlantic#ancient#history#ancient origins

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sorry but what? The reason Sicarius got overlooked for Captain of the 8th was that he got promoted to 5th instead. That is literally the plot to Blades of Damocles.

The person who wrote this entire article has zero clue about Ultramarine lore or what makes them cool. The cool thing about Ultras is the fact that they are actual space Romans, politicians first, warriors second.

Why destroy 20+ years of interconnected plots and intrigue for this? (am I surprised? Not really, not after them just killing off almost all of the captains off screan without an explanation or fanfare. But Im still allowed to be upset)

Also this is so fucking stupid. Sicarius had been captain for less then 3 years when the first Tyrannic war happened. Why would he feel overlooked? He is very happy to be with the 5th. Perhaps Ideaus or Ardias would have felt overlooked, but this new guy? No 😂

And the complete assassination of Marneus Calgar here is shocking. I know at least two short stories where he outright executes Inquisitors that as much as slanders Ultramar.

If you wanted to add Titus to the lore in a fateful way, either put him before Agemman, but if that fucks too much with the timeline, put Titus before/after Captain Pythea.

We know Sicarius took a sabbatical from his captaincy during/right before Uriel Ventris exile. We have never gotten an explanation why, would this not have been an excellent spot to place him?

This retcon is just plain lazy. I thought the Pythea retcon was stupid, but at least that one was plausable, this is just stupid.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Ancient Greeks in the Arctic --- The Voyage of Pytheas

from Invicta

37 notes

·

View notes