Text

Charlotte Robespierre basically having her own underground party made of her brother's ex-friends.

Rosalie Jullien casually inserting herself into government affairs by dining with the Robespierre siblings and the Barère brothers.

Éléonore Duplay and Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas basically serving as hosts for and connections between Babeuf, Buonarroti and others.

Albertine Marat and Simonne Évrard's entire lives of dedication to politics via Marat's memory.

God, I love those women.

#they're my next academic project#stay tuned#charlotte robespierre#rosalie jullien#élisabeth duplay lebas#éléonore duplay#albertine marat#simonne évrard#élisabeth duplay le bas

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

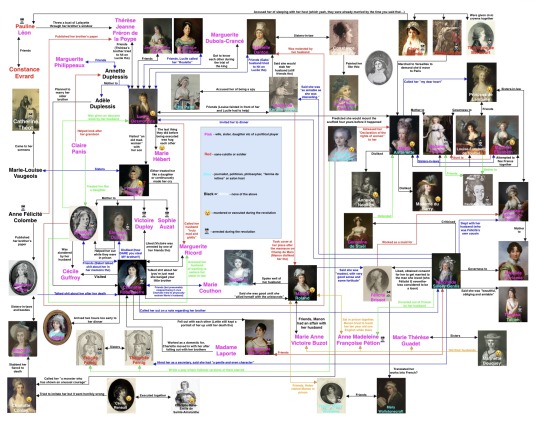

I decided to try this but for the girlies instead.

Are you sure want to click on ”keep reading”?

For Pauline Léon marrying Claire Lacombe’s host, see Liberty: the lives of six women in Revolutionary France (2006) by Lucy Moore, page 230

For Pauline Léon throwing a bust of Lafayette through Fréron’s window and being friends with Constance Evrard, see Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire (2006) by Claude Guillon.

For Françoise Duplay’s sister visiting Catherine Théot, see Points de vue sur l’affaire Catherine Théot (1969) by Michel Eude, page 627.

For Anne Félicité Colombe publishing the papers of Marat and Fréron, see The women of Paris and their French Revolution (1998) by Dominique Godineau, page 382-383.

For the relationship between Simonne Evrard and Albertine Marat, see this post.

For Albertine Marat dissing Charlotte Robespierre, see F.V Raspail chez Albertine Marat (1911) by Albert Mathiez, page 663.

For Lucile Desmoulins predicting Marie-Antoinette would mount the scaffold, see the former’s diary from 1789.

For Lucile being friends with madame Boyer, Brune, Dubois-Crancé, Robert and Danton, calling madame Ricord’s husband ”brusque, coarse, truly mad, giddy, insane,” visiting ”an old madwoman” with madame Duplay’s son and being hit on by Danton as well as Louise Robert saying she would stab Danton, see Lucile’s diary 1792-1793.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Marie Hébert, see this post.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Thérèse Jeanne Fréron de la Poype, and the one between Annette Duplessis and Marguerite Philippeaux, see letters cited in Camille Desmoulins and his wife: passages from the history of the dantonists (1876) page 463-464 and 464-469.

For Adèle Duplessis having been engaged to Robespierre, see this letter from Annette Duplessis to Robespierre, seemingly written April 13 1794.

For Claire Panis helping look after Horace Desmoulins, see Panis précepteur d’Horace Desmoulins (1912) by Charles Valley.

For Élisabeth Lebas being slandered by Guffroy, molested by Danton, treated like a daughter by Claire Panis, accusing Ricord of seducing her sister-in-law and being helped out in prison by Éléonore, see Le conventionnel Le Bas : d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve, page 108, 125-126, 139 and 140-142.

For Élisabeth Lebas being given an obscene book by Desmoulins, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre dissing Joséphine, Éléonore Duplay, madame Genlis, Roland and Ricord, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834), page 76-77, 90-91, 96-97, 109-116 and 128-129.

For Charlotte Robespierre arriving two hours early to Rosalie Jullien’s dinner, see Journal d’une Bourgeoise pendant la Révolution 1791–1793, page 345.

For Charlotte Robespierre physically restraining Couthon, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre and Françoise Duplay’s relationship, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 85-92 and Le conventional Le Bas: d’après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1902) page 104-105

For the relationship between Charlotte Robespierre and Victoire and Élisabeth Lebas, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre visiting madame Guffroy, moving in with madame Laporte and Victoire Duplay being arrested by one of Charlotte’s friends, see Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961)

For Louise de Kéralio calling Etta Palm a spy, see Appel aux Françoises sur la régénération des mœurs et nécessité de l’influence des femmes dans un gouvernement libre (1791) by the latter.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 198-207

For the relationship between Madame Pétion and Manon Roland, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 158 and 244-245 as well as Lettres de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 510.

For the relationship between Madame Roland and Madame Buzot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland (1793), volume 1, page 372, volume 2, page 167 as well as this letter from Manon to her husband dated September 9 1791. For the affair between Manon and Buzot, see this post.

For Manon Roland praising Condorcet, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 14-15.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 1, page 360.

For the relationship between Helen Maria Williams and Manon Roland, see Memoirs of the Reign of Robespierre (1795), written by the former.

For the relationship between Mary Wollstonecraft and Helena Maria Williams, see Collected letters of Mary Wollstonecraft (1979), page 226.

For Constance Charpentier painting a portrait of Louise Sébastienne Danton, see Constance Charpentier: Peintre (1767-1849), page 74.

For Olympe de Gouges writing a play with fictional versions of the Fernig sisters, see L’Entrée de Dumourier à Bruxelles ou les Vivandiers (1793) page 94-97 and 105-110.

For Olympe de Gouges calling Charlotte Corday ”a monster who has shown an unusual courage,” see a letter from the former dated July 20 1793, cited on page 204 of Marie-Olympe de Gouges: une humaniste à la fin du XVIIIe siècle (2003) by Oliver Blanc.

For Olympe de Gouges adressing her declaration to Marie-Antoinette, see Les droits de la femme: à la reine (1791) written by the former.

For Germaine de Staël defending Marie-Antoinette, see Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine par une femme (1793) by the former.

For the friendship between Madame Royale and Pauline Tourzel, see Souvernirs de quarante ans: 1789-1830: récit d’une dame de Madame la Dauphine (1861) by the latter.

For Félicité Brissot possibly translating Mary Wollstonecraft, see Who translated into French and annotated Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman? (2022) by Isabelle Bour.

For Félicité Brissot working as a maid for Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis: sur le dix-huitième siècle et sur la révolution française, volume 4, page 106.

For Reine Audu, Claire Lacombe and Théroigne de Méricourt being given civic crowns together, see Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel, September 3, 1792.

For Reine Audu taking part in the women’s march on Versailles, see Reine Audu: les légendes des journées d’octobre (1917) by Marc de Villiers.

For Marie-Antoinette calling Lamballe ”my dear heart,” see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 197, 209 and 252.

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Madame du Barry, see https://plume-dhistoire.fr/marie-antoinette-contre-la-du-barry/

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Anne de Noailles, see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 30.

For Louise-Élisabeth Tourzel and Lamballe being friends, see Memoirs of the Duchess de Tourzel: Governess to the Children of France during the years 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 and 1795 volume 2, page 257-258

For Félicité de Genlis being the mistress of Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon’s husband, see La duchesse d’Orléans et Madame de Genlis (1913).

For Pétion escorting Madame Genlis out of France, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis…, volume 4, page 99.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume, page 352-354

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Germaine de Staël, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 2, page 316-317

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théophile Fernig, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 300-304

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 106-110, as well as this letter dated June 1783 from Félicité Brissot to Félicité Genlis.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théresa Cabarrus, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume (1857) page 391.

For Félicité de Genlis inviting Lucile to dinner, see this letter from Sillery to Desmoulins dated March 3 1791.

For Marinette Bouquey hiding the husbands of madame Buzot, Pétion and Guadet, see Romances of the French Revolution (1909) by G. Lenotre, volume 2, page 304-323

Hey, don’t say I didn’t warn you!

#french revolution#frev#marie antoinette#pauline léon#claire lacombe#théroigne méricourt#reine audu#charlotte robespierre#éléonore duplay#élisabeth duplay#élisabeth lebas#lucile desmoulins#louise de kéralio#félicité de genlis#félicité brissot#mary wollstonecraft#manon roland#madame royale#charlotte corday#albertine marat#simonne evrard#catherine théot#madame élisabeth#sophie condorcet#françoise duplay#cécile renault#gabrielle danton#louise sebastien danton#theresa tallien#theresa cabarrus

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letter from Rosalie Jullien to Marc-Antoine Jullien fils in 1797

"We are ruined, my dear friend. That is to say, the loss we are suffering due to the decree on annuitants, which deprives us of 2,100 livres in income (with little hope for the third that was promised), will, I believe, compel us to withdraw to our estates once the unrest in the South has subsided and once our affairs here are settled, which will inevitably keep us here this winter. We will bear this loss with the resignation of philosophy and with the generous feeling of not regretting it if it can contribute to the consolidation of the public cause. But we must prudently encourage our children to handle Fortune’s

I urge you to be very economical and to put something aside to face unforeseen events, for the various losses we have suffered with paper money have left us so depleted that we have nothing to fall back on and are living day to day. I take pride in our poverty when I reflect on the degradation and corruption that often accompany wealth. And, in urging you to honestly gather what you can, I would never advise you to chase

Instead, let it be clear that it is wise to gather enough to live independently, for neither of you has that ugly love of wealth that breeds all kinds of corruption; neither of you harbors the tastes and passions that foster such desires. You value honor and the respect that comes from virtue. You have adopted simple habits within the modesty you have always known in the parental home. Keep these habits to be wise and happy. Your brother is like you, and I hope our two children will always follow in the footsteps of their virtuous father".

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The issue of Robespierre's newspaper, in which he so skillfully takes all the tones to bring down Petion, made me really sad. If Robespierre had been my husband or my son, I would have put myself at his feet to obtain the sacrifice of this moment of revenge."

Rosalie Jullien. Journal d'une bourgeoise pendant la Révolution, 1791-1793

16 notes

·

View notes

Link

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just want to reiterate how good these podcasts on the French Revolution are:

Épisode 1 : Olympe de Gouges, une femme du XXIe siècle

Épisode 2 : 1793 les exhumations de Saint Denis ou l’encombrant cadavre de la monarchie

Épisode 3 : Rosalie Jullien, une "écrivassière" engagée sous la Révolution française

Épisode 4 : La vie quotidienne sous la Révolution

Épisode 5 : Le bolivarisme et les indépendances hispano-américaines

#Honestly I didn't know much about the 1793 exhumations and the detailed descriptions are striking#Rosalie Jullien has such a fine writing I need to read her letters#Frev#Révolution française#French revolution#Français

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The famous “David” sketch: falsely attributed?

The new exhibition Marie-Antoinette, metamorphosis of an image is bringing to light something which has apparently been the subject of discussion in the art world for some time: the famous sketch of Marie Antoinette on her way to the guillotine, in a loose white gown, eyes downcast, face set in a frown; a sketch which has inspired a thousand bits of prose and contrasting opinions about the intention of the artist... may not have been done by David or drawn from life at all.

According to the exhibition, the famous drawing depicting Marie Antoinette on her way to the guillotine was not drawn by Jacques Louis-David, and possibly was never drawn from life. Multiple art experts (including an expert on David's work, Philippe Bordes and Xavier Salmon, art historian and curator at the Louvre) agree that the sketch does not correspond to David's work or style; there is also no outside evidence that the sketch was done by David aside from a single attribution.

The alleged mis-attribution dates back to the original owner of the drawing, Jean-Louis Soulavie, who penned the description underneath the original drawing: "Portrait of Marie Antoinette queen of France led to death, drawn in pen by David, spectator of the scene, and placed on the window of Citizen Jullien [Rosalie Ducrollay]; wife of representative Jullien, who told me this story.”

Xavier Salmon proposed that one possible artist was the famous Vivant Denon; several of Denon’s works have been falsely attributed to David in the past, so this would not be the first. Denon was a friend of David’s as well, and David helped him secure work in revolutionary Paris, though Denon frequently traveled throughout Europe during the revolution. Denon would have drawn the work from scratch as Denon was not back in Paris until mid-December 1793, and could not have been an eyewitness.

I have ordered the exhibition catalog, so I am hoping it has more information about the possible mis-attribution, and if it does I will definitely post an update!

#marie antoinette#french history#art history#18th century#french revolution#mah face rn#:O :O#if you look up some of denon's sketches from this period I can see similarities#moreso than david's sketches

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris, 10 février 1793.

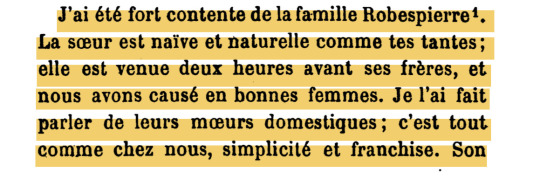

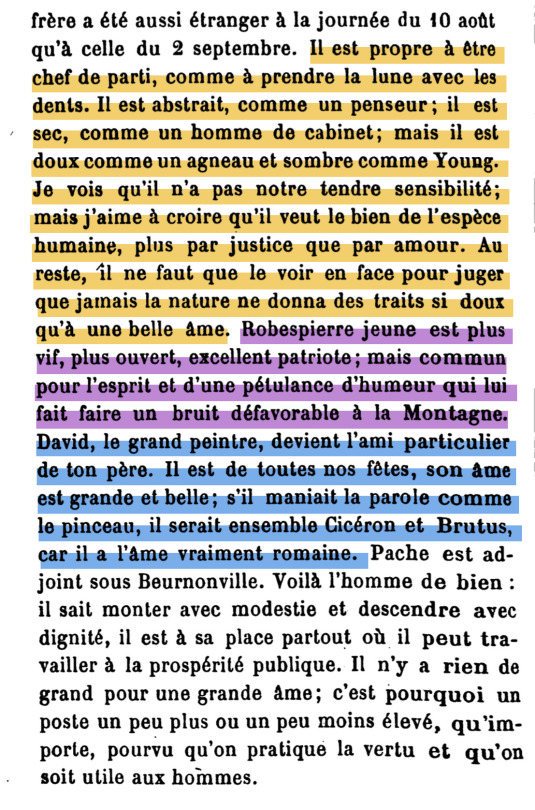

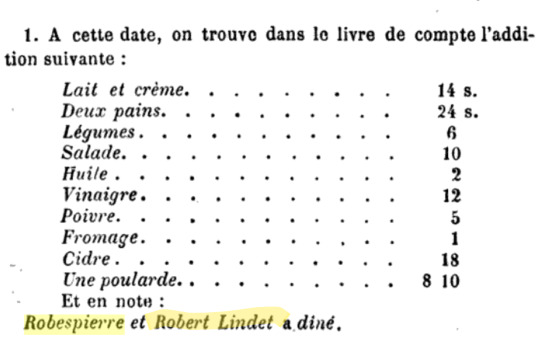

Rosalie Jullien dines with the Robespierre siblings and describes them in a letter.

This is absolutely precious.

Source: Journal d'une bourgeoise (1881), p. 345-346.

Also this note:

(She also often dines with Barère and his cousin too.)

#rosalie jullien#augustin robespierre#charlotte robespierre#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#robespierre siblings#famille robespierre#famille jullien

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did people in 18th century France see Robespierre as effeminate or “like a eunuch?” Or did that characterization completely come after his death as opposed to just being an exaggerated trait also precieved during his lifetime?

It’s a bit hard to know how people viewed Robespierre during his time alive, given the fact most written descriptions we have of him, sympathetic and hostile alike, are from after his death. But at least for the moment, I can’t come up with any descriptor pre-thermidor that linked Robespierre to such things as ”femininity” or ”unmanliness” (Dubois de Crancé (1792), John Moore (1792), Pétion (1792), Rosalie Jullien (1793).

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I just saw your reply to an ask and noticed this passage:

At the end of a century which had profaned love, Robespierre distinguished himself by the purity of his morals and by the delicacy of his procedures towards a sex, which the literature of the time regarded as born almost solely for pleasure. Above all, he respected the marital bed.

Do you know more about Robespierre and his views and relationships with marriage/women (I don't mean in the political sense)?

I've heard that he was meant to marry once but the lady ended up marrying someone else. And that he wrote a poem to a lady once, and that he enjoyed talking/singing/dancing with the ladies at the poets club he used to frequent (I can't remember the name of it atm). Overall, I get the idea that he loved/respected/admired women a lot and wanted to marry in the future. And also that he had conservative views on marriage and women. Am I correct? Are there any other examples I missed?

Thank you!

Yes, Robespierre overall seemed to have respected and gotten along well with women. He gets described in friendly terms by both his sister, Élisabeth Lebas and Rosalie Jullien, who all met him in private. The woman he sent poetry to was Charlotte Buissart, whose entire family was close to both him and his siblings (they would however fall out with each other during ”the terror”). In the 1780’s Robespierre also sent works of his to one mademoiselle Duhay (1, 2, 3) who in her turn gave him canaries and puppies, as well as to ”une dame”, to whom he wrote that ”the sweetest, the most glorious of all, is to be able to communicate these feelings to a kind and illustrious lady whose noble soul is made to share them.” The historian Ernest Hamel reportedly tracked down an old woman in Arras who told him her mother used to dance with Robespierre and found him a pleasant partner, and once Robespierre got into politics the amounts of female fans he had was noted by contemporaries. There evidently exists so much material regarding his relationship with women that the historian Hector Fleischmann in 1913 could release a whole book with the title Robespierre and the women he loved (original title Robespierre et les femmes).

For the moment I can only really remember one instance where Robespierre is reported to have acted in an inappropriate way towards a woman, and it was reported in Souvernirs d’un déporté (1802) by Paul Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary for a few months 1790-1791:

As for [Robespierre’s] continence, I only knew of a woman of about twenty-six years, whom he treated rather badly, and who idolized him. Very often he refused her at his door; he gave her a quarter of his fees; tre rest of it was split between me and a sister he had in Arras whom he loved very much.

Villiers’ work was declared apocryphal by the historian René Garmy in 1967. When Hervé Leuwers 47 years later wrote he still thought it authentic, he added that some parts of it still seemed like ”probable fabrication” and listed the mistress claim as an example, though without elaborating why he thought that was.

There are three women Robespierre is alleged to have been engaged to — mademoiselle Deshorties, Adélaïde Duplessis and Éléonore Duplay — though none of these allegations were ever confirmed by Robespierre or the women themselves. The lady you’re thinking of is the first of those listed — mademoiselle Deshorties (it’s often said her firstname was Anaïs, but I don’t know what the source for that is). She was Robespierre’s step-cousin and had, according to Charlotte Robespierre’s memoirs, been courting him for two to three years at the start of the revolution. Charlotte claims that it’s very likely the two would have married had things remained the way they were, however, with Maximilien away in Paris, mademoiselle Deshorties soon enough got engaged to someone else, and the two got married in 1792. When Robespierre found out about this after returning to Arras for a short stay, he was ”very grievously affected” according to Charlotte.

If Robespierre would have married had he lived if of course something we can’t know for sure. There does exist an anecdote where he, upon his friend’s Pétion’s insistence that they must find him a wife to lighten up his stiff behaviour, firmly responds: ”I will never marry!” If it is to be treated seriously or not is of course another story (and, if it happened, who knows if he changed his mind between this moment and his death).

As for if Robespierre held conservative views on marriage and women, for the first of these topics, I can only really find one place where he’s recorded to have mentioned it at all, and it’s when he on May 31 1790 argues for granting priests the right to marry, stating among other things that ”to unite priests with society, we must give them wives.” However, this of course has more to do with men’s relation to marriage and not women’s.

For his view on these, his perhaps most feminist moment takes place in 1787, when the Arras Academy of which he since one year back was the director, accepted two well-read women as honorary members — Marie Le Masson Le Golft and Louise de Kéralio. Robespierre was not present when the two were elevated to membership, but he was the author behind the response to the discours de la réception written by de Kéralio (who ironically, would go on to voice much more sexist opinions compared to Robespierre). In the text, he regretted that there were so few women in the academies and advocated for letting more in, arguing that ”habit and perhaps the force of prejudice” had intimidated women from presenting themselves as candidates for open academy positions, but that ”their sex does not make them lose the rights that their merit has earned them. […] If we grant that women have intelligence and reason, can we refuse them the right of cultivating them?” This is however not to say he viewed men and women as being the same in essence, but rather that they had received different sets of talents from nature that complemented each other. Men and women, he argued, were not meant to study the same subjects, the former being more suited for ”the initricacies of the abstract sciences,” while the latter should not be forbidden to contribute to those fields that ”demand only sensibility and imagination,” such as litterature, history and morality. Another argument put forward is that women will be able to make the sessions more interesting for the men:

The mere presence of a lovable woman is enough to enjoy these cold pleasures. They give interest to nothing, they spread a secret charm over this insipid circle of monotonous amusements which usage brings back every day. Women make a conversation where nothing is said, an assembly where nothing is done, more than bearable. They share laughter and merriment around a game table. Beauty, when it is mute, even when it does not think, still interests; it animates everything around. It is Armide who changes the dreadful deserts into laughing groves, into delicious gardens. From this, let us form the idea of a society where we would see the most amiable and witty women conversing with enlightened men about the most pleasant and interesting objects that could occupy beings made to think and to feel. Ah! If those who have no other merit than the amiability of their sex can respond so gently about the business of life, what will it be like for those who, freed from the false shame of appearing educated, without blushing to be more amiable and more enlightened would boldly deploy in an interesting conversation the playfulness of a delicate mind and the graces of a laughing imagination and all the charms of a cultivated reason!

A year earlier, the lawyer Robespierre had also been given as client the Englishwoman Mary Sommerville, widow of Colonel George Mercer, Governor of South Carolina, who had been imprisoned for debt. In his defence of her, Robespierre first and foremost underlined the fact that the Ordonnance de Saint-Germain-en-Laye from 1667 expressly stated that women and girls couldn’t be kept imprisoned. But he also voiced his personal support of this differential treatment between the sexes:

When the legislators introduced this terrible right to throw a man into prison for the non-performance of a civil commitment, I observed that they made it their duty to soften its rigor by a large number of restrictions. One of the main ones was to exclude women; reason and humanity indicated this exception to them; its motives can be discovered by every man made to think and feel. The ease, the inexperience of this sex which would have led it to contract too lightly commitments fatal to its freedom; its weakness, its sensitivity which makes it more overwhelming for the shame and rigor of captivity; the terrible impressions that the apparatus of such constraint must have made on its timid nature; the fatal consequences that it can cause, especially during pregnancy; what will I at last say? The delicate honor of women, which the glare of a public and legal affront irreversibly degrades in the eyes of men, whose tenderness vanishes with the respect they inspire in them; the sacred interest of modesty injured by the violence which accompanies this rigorous path, and the facilities which it can provide to outrage it...

Once we get to the revolution, I have yet to find a place where Robespierre talks about women much at all. Searching for the term ”femmes” in the volumes of Oeuvres complètes de Robespierre covering this period, the most common phrase it shows up in is probably ”women and children,” as in, something good and precious that needs protection against counter-revolutionaries. The two instances I’ve found where he speaks a bit more on women as such are the following:

Women! this name recalls dear and sacred ideas. Wives! this name recalls very sweet feelings for all the friends of the society. But aren't the wives republican? And doesn’t this title impose duties? Should Republican women renounce their status as citoyennes to remember that they are wives? Robespierre at the Convention, December 20 1793, showing his hesitation towards a commission of women that has arrived to plead for mercy for their husbands.

You will be there, young citoyennes, to whom victory must soon bring back brothers and lovers worthy of you. You will be there, mothers of families, whose husbands and sons raise trophies for the Republic with the debris of the thrones. O French women, cherish the liberty purchased at the price of their blood; use your empire to extend that of republican virtue! O French women, you are worthy of the love and respect of the earth! What do you have to envy of the women of Sparta? Like them, you have given birth to heroes; like them, you devoted them, with sublime abandonment, to the Fatherland. Robespierre’s report on religious and moral ideas and republican principles, held on May 7 1794

Robespierre is not confirmed to have ever openly advocated for women being granted more political rights in general, like Condorcet and Guffroy in 1790 or Guyomar in 1793, or that married ones deserved to share the right to administration of property with their husbands, like Desmoulins, Danton, Lacroix and Couthon in 1793. However, this is not to say he ever openly spoke against these ideas either. In the third number of his journal Le défenseur de la constitution (1792) Robespierre does however warn about a girondin plot that includes a ”female triumvirate,” seemingly implying he thinks the concept of women in power needs to be side-eyed:

When following the thread of this plot, we arrive at a female triumvirate, at M. Narbonne who, then struck by an apparent disgrace, nonetheless named the ministers; at Mr. La Fayette, who arrived at this time from the army in Paris, and who attended secret meetings with the deputies of Gironde, what vast conjectures can we not indulge in?

The three women Robespierre is alluding to here have been identified as Manon Roland, Sophie Condorcet and Louise de Kéralio-Robert, the latter of which ironically being the same de Kéralio he had welcomed as an honorary member to the Arras academy five years earlier.

Finally, in a notebook he kept in the fall of 1793 regarding measures to be taken, Robespierre has written ”Dissolution of F.R.R” as in the society Femmes Républicaines Révolutionnaires, which would indeed be shut down by the Committee of General Security on October 30, alongside all other women’s clubs. This has however been accepted as part of a bigger pattern of the deputies cracking down on anything that may pose opposition to the government and not a move against women in particular, even if Jean Pierre André Amar, when announcing the dissolution to the Convention, did motivate it in sexist terms.

It’s however hard for me to say if all these factors added together makes Robespierre have an overall conservative or an overall radical view on women. This due to the fact I still haven’t fully discovered what the standard perspective on the topic was for the time for an educated, middle class man. Instead, the concept of women and what they are and are not capable of comes off as deeply controversial, look for example at the aforementioned debate on women’s right to the administration of property, where men with overall similar backgrounds and educations come to fully different conclusions, some arguing women are biologically incapable of handling such things and some that women are born with as much capacity as men and that not letting them enjoy this right would be akin to slavery. Someone could ask for women to more or less be granted the same rights as men only for someone else to suggest women shouldn’t even be taught to read a few years later. The article Robespierre: old regime feminist? (2010), while underlining Robespierre’s suggestion to let women into the academies was met with a lot of backlash (nine out of eleven correspondents disagreeing with his views), also makes sure to state he was nevertheless far from alone in pushing for this integration, and that those who were against it argued less for the notion that women were incapable of learning (the actual amount of well-read ones making it come off as weak) and more that ”they could but they shouldn’t” since they needed to take care of the home and children. All of this makes it hard to say exactly how normal/radical/conservative Robespierre’s views were for the time. I would conclude by saying he deserves a ribbon for neither ”Revolution’s number one feminist” nor ”World’s most raging misogynist.” In his private life, he does however appear to have gotten along well with women, at least we don’t really possess any serious testimony hinting at anything else.

#ok this ended up being about his political views on women anyways hope you don’t mind#but yeah that’s about all i know regarding the subject#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#frev#ask

32 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Robespierre qui était rentré à 4 heures du matin du Comité et qui jouissait dans les bras de Morphée de trop justes délassements a été réveillé en sursaut par un républicain qui lui crie : "Toulon est à nous". Il dit à moitié endormi : "Pitt est f. et la République est sauvée". Il se lève avec précipitation, et pour cette fois la joie imprime sur son visage austère tous les traits du vrai contentement.

Lettre de Rosalie Ducrollay Jullien à son fils Marc-Antoine Jullien, commissaire du CSP à Lorient. Paris, 4 nivôse an II (Annie Duprat, éd., “Les affaires d’État sont mes affaires de cœur”. Lettres de Rosalie Jullien, une femme dans la Révolution. 1775-1810, 2016, p. 278).

#Robespierre#Rosalie Jullien#Marc-Antoine Jullien#Révolution française#Maximilien Robespierre#4 nivôse an II#an II#reprise de Toulon

211 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[J'ai] vu, hier la femme d'Hector Barère et son joli poupon Brutus. Brutus – poupon, quel disparate ! Cependant, il y en a tant dans les langes grâce à l'empressement qu'on a de donner ce nom à nos enfants républicains. Il faudra bien que l'ombre de Brutus s'accommode de toutes nos grâces françaises et de toutes nos tendresses maternelles quand tous ces Brutus nouveaux seront arrivés à la maturité de l'homme.

Lettre de Rosalie Ducrollay Jullien à son fils Marc-Antoine Jullien, commissaire du CSP à Bordeaux. Paris, 24 germinal an II (Annie Duprat, éd., “Les affaires d’État sont mes affaires de cœur”. Lettres de Rosalie Jullien, une femme dans la Révolution. 1775-1810, 2016, p. 291).

Hector Barère, cousin du conventionnel, a été un temps commissaire du pouvoir exécutif dans les ports, où il a pu collaborer avec Marc-Antoine Jullien. Je ne sais malheureusement rien de sa femme ou de son fils.

#Rosalie Jullien#24 germinal an II#Révolution française#prénoms révolutionnaires#Hector Barère#Brutus Barère#Marc-Antoine Jullien#an II

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Voilà mon idée, c'est que les uns veulent une République pour eux et pour les riches, et les autres la veulent toute populaire et toute pour les pauvres, et c'est avec les passions humaines ce qui divise si scandaleusement notre Sénat.

Rosalie Jullien à son fils Marc-Antoine, 24 octobre 1792.

#Rosalie Jullien#Révolution française#Convention nationale#24 octobre 1792#Marc-Antoine Jullien#Jullien de Paris#1792

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

#Rosalie Jullien#Révolution française#on aurait peut-être dû nuancer un peu sur Jullien de Paris#il était bel et bien l'envoyé du CSP et non seulement de Robespierre#mais bon je ne veux pas trop chicaner sur ce qui est d'ailleurs une très bonne émission

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ribbons of Scarlet: A predictably terrible novel on the French Revolution (part 1)

Parts 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Q: Why is this post in English? Isn’t this blog usually in French?

A: Yes, but I can’t bypass the chance, however small, that someone in the book’s target audience might see and benefit from what I’m about to say.

Q: Why did you even read this book? Don’t you usually avoid bad French Revolution media?

A: My aunt left the book with me when she came for my defense last November. I could already tell it would be pretty awful and might not have read it except that I needed something that didn’t require too much concentration at the height of the Covid haze and I — like most people who insisted on finishing their doctorate despite the abysmal academic job market — have a problem with the sunk cost fallacy, so once I got started I figured I might as well find out just how bad it got.

Q: Don’t you have papers to grade?

A: … Next question.

Q: Aren’t you stepping out of your lane as an historian by reviewing historical fiction? You understand that it wasn’t intended for you, right?

A: First of all, this is my blog, such as it is, and I do what I want. Even to the point of self-indulgence. Why else have a blog? Also, I did receive encouragement. XD;

Second, while a lot of historians I respect consider that anything goes as long as it’s fiction and some even seem to think it’s beneath their dignity to acknowledge its existence, given the influence fiction has on people’s worldview I think they’re mistaken. Besides, this is the internet and no one here has any dignity to lose.

Finally, this is not so much a review in the classic sense as a case study and a critical analysis of what went wrong here that a specialist is uniquely qualified to make, not because historians are the target audience, but because the target audience might get the impression that it’s not very good without being able to articulate why. To quote an old Lindsay Ellis video, “It’s not bad because it’s wrong, it’s bad because it sucks. But it sucks because it’s wrong.” Or, if you prefer, relying on lazy clichés and adopting or embellishing every lurid anecdote you come across is bound to come across as artificial, amateurish and unconvincing.

This is especially offensive when you make grandiose claims about your novel’s feminist message and the “time and care” you supposedly put into your research.

I also admit to having something of a morbid fascination with liberals creating reactionary media without realizing it, which this is also a textbook example of (if someone were to write a textbook on the subject, which they probably should).

With that out of the way, what even is this book?

The Basics

It’s a collaboration between six historical novelists attempting to recount the French Revolution from the point of view of seven of its female participants. One of these novelists is in fact an historian herself, which is a little bit distressing, given that like her co-authors, she seems to consider people like G. Lenotre reliable sources. But then, she’s an Americanist and I’ve seen Americanists publish all kinds of laughable things about the French Revolution in actual serious works of non-fiction without getting called out because their work is only ever reviewed by other Americanists. So.

Anyway, if you’re familiar with Marge Piercy’s (far superior, though not without its flaws) City of Darkness, City of Light, you might think, “ok, so it’s that with more women.” And you might think that that’s not so bad of an idea; Marge Piercy maybe didn’t go all the way with her feminist concept by making half the point of view characters men (though I’d argue that the way she frames how they view women was part of the point). It’s even conceivable that if Piercy had wanted to make all the protagonists women her publisher would have said no on the grounds of there not being a general audience for that. It was the 1990s, after all.

Except the conceit this time is they’re all by different authors, we have some counterrevolutionaries in the mix, and instead of the POV chapters interweaving, each character gets her own chunk of the novel, generally about 70-80 pages worth, although there are a couple of notable exceptions. We’ll get to those.

It’s accordingly divided as follows:

· Part I. The Philosopher, by Stephanie Dray, from the point of view of salonnière, translator, miniaturist and wife of Condorcet, Sophie de Grouchy, “Spring 1786” to “Spring 1789”; Sophie de Grouchy also gets an epilogue, set in 1804

· Part II. The Revolutionary, by Heather Webb, from the point of view of Reine Audu, Parisian fruit seller who participated in the march on Versailles and the storming of the Tuileries, 27 June-5 October 1789

· Part III. The Princess, by Sophie Perinot, from the point of view of Louis XVI’s sister Élisabeth, May 1791-20 June 1792

· Part IV. The Politician, by Kate Quinn, from the point of view of Manon Roland, wife of the Brissotin Minister of the Interior known for writing her husband’s speeches and for her own memoirs, August 1792-(Fall 1793 — no date is given, but it ends with her still in prison)

· Part V. The Assassin, by E. Knight, which is split between the POV of Charlotte Corday, the eponymous assassin of Marat, and that of Pauline Léon, chocolate seller and leader of the Société des Républicaines révolutionnaires, 7 July-8 November 1793

· Part VI. The Beauty, by Laura Kamoie, from the point of view of Émilie de Sainte-Amaranthe, a young aristocrat who ran a gambling den and who got mixed up in the “red shirt” affair and was executed in Prarial Year II, “March 1794”-“17 June 1794”

An *Interesting* Choice of Characters…

Now, there are some obvious red flags in the line-up. I’m not sure, if you were to ask me to come up with a list of women of the French Revolution I would come up with one where 4/7 of the characters are nobles/royals — a highly underrepresented POV, as I’m sure you’re all aware — but fine. Sophie de Grouchy is an interesting perspective to include and Mme Élisabeth at least makes a change from Antoinette? And though the execution is among the worst (no pun intended) Charlotte Corday’s inclusion makes sense as she is famous for doing one of the only things a lay audience has unfortunately heard of in association with the Revolution.

Reine Audu is actually an excellent choice, both pertinent and original. Credit where credit is due. Manon Roland and Pauline Léon are not bad choices either in theory, but given the overlap with Marge Piercy’s book, if you’re going to do a worse job, why bother? The inclusion of Sophie de Grouchy, while, again, not a bad choice, also kind of makes this comparison inevitable, as another of Piercy’s POV characters was Condorcet.

But Émilie de Sainte-Amaranthe? I’m not saying you couldn’t write an historically grounded and plausible text from her point of view, but her inclusion was an early tip-off that this was going to be a book that makes lurid and probably apocryphal anecdotes its bread and butter.

The absolute worst choice was to make Pauline Léon only exist — at best — as a foil to Charlotte Corday. (It turns out to be worse than that, actually. She’s less of a foil than a faire-valoir.)

Still, why does no one write a novel about Simone and Catherine Évrard (poor Simone is reduced to “Marat’s mistress” here, not just by Charlotte Corday, which is understandable, but also by Pauline Léon) or Louise Kéralio or the Fernig sisters or Nanine Vallain or Rosalie Jullien or Jeanne Odo or hell, why not one of the dozens of less famous women who voted on the constitution of 1793 or joined the army or petitioned the Convention or taught in the new public schools. Many of them aren’t as well-documented, but isn’t that what fiction is for?

Let’s try to be nice for a minute

There are things that work about this book and while the result is pretty bad, I think the authors’ intentions were good. Like, who could object to the dedication, in the abstract?

This novel is dedicated to the women who fight, to the women who stand on principle. It is an homage to the women who refuse to back down even in the face of repression, slander, and death. History is replete with you, even if we are not taught that, and the present moment is full of you—brave, determined, and laudable.

It’s how they go about trying to illustrate it that’s the problem, and we’ll get to that.

For now, let me reiterate that while I’m not a fan of the “all perspectives are equally valid” school of history or fiction — or its variant, “all *women*’s perspectives are equally valid” — and there are other characters I would have chosen first, it absolutely would have been possible to write something good with this cast of characters (minus making Charlotte Corday and Pauline Léon share a section).

The parts where the characters deal with their interpersonal relationships and grapple with misogyny are mostly fine — I say mostly, because as we’ll see, the political slant given to that misogyny is not without its problems. These are the parts that are obviously based on the authors’ personal experience and as such they ring true, if not always to an 18th century mentality, at least to that lived experience.

Finally, there are occasionally notes that are hit just fine from an historical perspective as well. The author of the section on Mme Élisabeth doesn’t shy away from making her a persistent advocate of violently repressing the Revolution. Manon Roland corresponds pretty well to the picture that emerges from her memoirs even if the author of her section does seem to agree with her that she was the voice of reason to the point of giving her “reasonable” opinions she didn’t actually hold.

I should also note that while the literary quality is not great, it’s not trying to be great literature and in any case, on that point at least, I’m not sure I could do better.

Ok, that’s enough being nice. Tune in next time for all the things that don’t work.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

C’est très décevant d’entendre Annie Duprat raconter que Robespierre (tout seul, bien entendu...) a envoyé Marc Antoine Jullien fils dans les départements essentiellement pour faire guillotiner les gens. Je la croyais meilleure historienne. C’est particulièrement irresponsable de véhiculer ce genre de récit pour le grand public (il s’agit d’un entretien sur France Culture) quand on devrait toujours en profiter pour encourager à la remise en cause des clichés et non contribuer à les renforcer.

Déjà, Jullien était l’agent du CSP, non du seul Robespierre — il a travaillé avec Prieur de la Marne et Jeanbon Saint-André (entre autres représentants en mission) et il entretenait une correspondance avec le CSP pris collectivement en plus de sa correspondance particulière avec Robespierre et Barère. Ensuite, il est vrai qu’il a poursuivi un groupe de Brissotins fugitifs, dont Pétion, et je ne m’attends pas à ce qu’on le taise, mais réduire son activité à ce seul point est une déformation inexcusable, surtout quand le public a déjà l’habitude d’entendre que la Révolution n’a été que violence.

(D’ailleurs, l’explication que donne Annie Duprat, qui veut que Rosalie Jullien ait changé d’avis sur Pétion uniquement par peur ou par esprit de parti me semble assez faible, mais cela me posait déjà problème dans son livre.)

#je sais que j'écoute cette émission quelques mois en retard#et du coup je devrais peut-être m'abstenir de la commenter#mais cet exemple est hélas symptomatique#d'un phénomène que l'on rencontre tout le temps#Révolution française#Marc Antoine Jullien#Marc Antoine Jullien fils#Jullien de Paris#Prieur de la Marne#Robespierre#Barère#Maximilien Robespierre#Bertrand Barère#Annie Duprat

9 notes

·

View notes