Text

Brief list of Sēt-Typhōn epithets (from PGM IV. 154—285)

Σκηπτουχος— Scepter-bearing

θεὲ θεῶν — God of Gods

Γνοφεντινάκτα — Disturber of the Dark βρονταγωγέ — Bringer of Thunder Λαιλαφετης — Sender of Storms Νυκταράπτα — Lighting Flasher of the Night Ψυχροθερμοφύσησε — One Who Exhales the Cold and the Heat Πετρεντιυάκτα — Stone-shaker Τινακτως — Shaker, Trembler, Agitator, Disturber. Τειχοσεισμοποιέ — Wall/Earth-quaker Κοχλαζοκύμων — Boiler of the Waters βυθοταραξοκίνησε — One Who Stirs the Depths to Motion

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magical Gemstones: An Abridged Guide

Magical gemstones are a type of talisman made of semiprecious stones —such as hematite, carnelian or amethyst— that were worn set in rings or as pendants and their size ranges from 1.5 cm to 3 cm.These gemstones haven't magical, protective characteristics because of the nature of the gem itself but because the representations of Gods and holy names carved conceded them virtues through holy dynamis: This is, among other things, the inherent power of divine names and/or their representations.

These depictions are normally inverted (negative) This, together with the fact that some of the gems show a certain degree of worn indicates that they were manipulated in some way—probably rubbed or even licked, in order to increase their efficacy—proves that they were not conceived as seals but as amulets or talismans.

A magical gemstone, to be considered as such, should have one or more of the following elements:

An iconographic language generally belonging to syncretic Gods or that combines Gods from different origins.

Charakteres (magical signs. They can be planetary, protective, etc.)

Voces magicae (Words of power and phrases whose formulation and structure may hide secret, sacred names of Gods as well as prayers or incantations dedicated to them, sometimes with the intention of controlling their emanations and daimonēs) and logoi (magical names, permutation of magical names and vocals).

The practice and use of magical voices was transmitted orally across the eastern Mediterranean, but it wasn't until the early 1st century b.c.e. the practice began to be included in written form. The abundance of amulets and gems with magical names and signs are evidence of this change of paradigm.

In addition, elements are usually complemented by two structural features:

The gemstone is engraved on both the obverse and the reverse, sometimes even on the edge.

The inscription appears directly and not in mirror writing.

These magic gemstones, in addition, can be magical gemstones stricto sensu and amuletic gems. The latter differ from the former in:

That the iconographic patterns they contain are explicitly described as belonging to amulets in textual sources such as Posidippus's Lithika

They bear a prophylactic inscription, usually "diaphylasse" (protect me!), "sōzon" (save me!) or "Heis Theos" (One God).

Its production began during the late Hellenistic period, but it was not until the 2nd and 4th centuries c.e. that it reached its apogee. Magical gemstones' imagery demonstrates the diversity and plurality of Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Egyptian, Christian, Gnostic and Jewish representations and ideas from the Mediterranean from the Roman period, as well as the popularity and diversity of magical activities and practices.

These magic gemstones were rarely used for evil purposes, such as harming someone. Their most common use was to offer protection or solve personal health problems: those showing an ibis tied by an altar and including the command "pésse!" (digest) were used to heal indigestion and other stomach problems; others, depicting a uterus, offered represented a womb, offered protection during childbirth and guaranteed fertility.

Although most of these magic gemstones were used as jewelry, it is possible that they also had other uses, as part of a ritual to heal a patient or as a physical component for an incantation, such as those with depictions of Harpocrates seated on a lotus the nomina magica Bainchōōōch (Bainchōōōch, Ba of the Shadow, isn't only a vox magica/nomina magica but a God on their own right. PGM aside, Bainchōōōch appears in Pistis Sophia as a triple powered deity that descends onto Jesus, giving him his powers)

An interesting fact is that of the production of magical gemstones during the 17th and 18th centuries of our era. Although the production of these gems continued during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance —irregularly, of course— they reflected the magical and religious reflected the magical and religious practices of their historical context.

This, however, was not the case during the 17th and 18th centuries, where magical gemstones of great quality and sophistication were produced, which not only reproduced the iconographic motifs and logoi of the pre-existing graeco-egyptian magic gemstones, but also introduced new ones. An example of these gems are those with representations of Christ-Osiris or Jesus-Khepri

Sources:

Nagy, M. A., (2015) Engineering Ancient Amulets: Magical Gems of the Roman Imperial Period. in D. Boschung and J. Bremmer (eds), The Materiality of Magic (Morphomata 20). Paderborn, 205-240.

Faraone, C. (2018) The Transformation of Greek Amulets in Roman Imperial Times, Filadelfia; University of Pennsylvania Press.

Simone, M., (2005) (Re)Interpreting Magical Gems, Ancient and Modern en Shaked, S., Officina Magica: Essays on the Practice of Magic in Antiquity (IJS Studies in Judaica, vol. 4), Leiden; Brill, 141-170.

Campbell-Bonner Magical Gems Database (http://cbd.mfab.hu)

#magical gemstones#gemstones#PGM#Set#Sutekh#Set-Typhon#Sēt-Typhon#magic#religious syncretism#polytheism#egyptian polytheism#hellenic polytheism#kemetic polytheism#greek magical papyri#Bainchoooch#Thoth#talismans#amulets#talismanic magic

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Seth is the god of blasphemous and scandalous curiosity. This is also the theme of a myth told by Ovid and several other ancient authors that provides an explanation of animal worship in ancient Egypt. The gods, it is revealed, so feared the reckless curiosity of Seth-Typhon that they decided to disguise themselves in the shapes of animals. Later they declared these animals sacred out of gratitude to them. Diodorus of Sicily, who calls the cult of the animals an aporrhêton dogma (unspeakable secret) replaces “Seth” with “humankind” in his rendering of the story, which is how he claims to have heard it in Egypt. It seems possible that this very strong and conspicuous condemnation of curiosity reflects an Egyptian reaction to the scientific and investigative mind of the Greeks, who subjected the Egyptians to a veritable program of “Egyptological” research. It strangely foreshadows Saint Augustine’s verdict on curiosity, which dominated the occidental attitude toward the world and nature until the end of the sixteenth century. Another work in which the theme of curiosity plays a central role is The Golden Ass, by Apuleius of Madauros. Lucius, the hero, dabbles in magic out of an insatiable curiosity and is punished by being transformed into an ass, the animal of Seth, whose principal vice he practiced."

Jan Assmann, Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

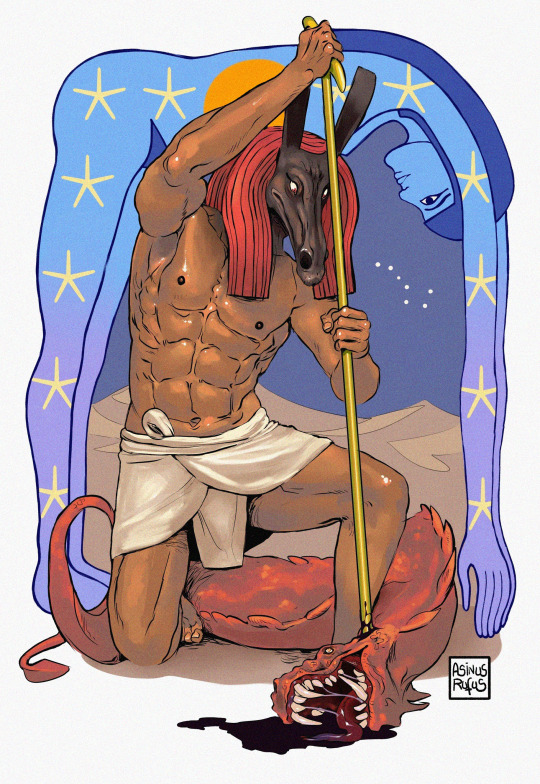

Planned to upgrade the former devotional icon on my altar, so designed a new one under my Lord's guiding.

Khaire Sēt-Typhōn, Skēptoûkhos, God of gods, you of the great dýnamis!

#my art#personal art#set#sutekh#sēt#sēt-typhon#devotional icon#devotional art#polytheism#graeco egyptian polytheism#occult#tw: nudity#netjer#netjeru#theoi

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some notes about the Typhonian Ink

An interesting detail about the use of calcium oxide (which generates heat on contact with water) and asbestos (a retardant) in the recipe for Typhonian Ink suggested on PGM XII. 96-106 is that these two ingredients apparently contribute nothing to the ink, but, why's that?

Ignoring these two ingredients, we just have an average red ink of organic origin: its sanguine red color —red is the setian/typhonian color par excellence— it's given by its pigments; red ochre (mainly composed by iron—Sēt's sacred metal—oxide), red poppy, and dried, grounded acacia seeds, all blended together with artichoke juice (which turns brown when oxidized) contribute to darken the characteristic red tone of the ink, giving it, as I mentioned before, that sanguineous appearance. Blood, by the way, is a polysemous term within the framework of PGM.

The mentions to the snake's blood, hawk's blood or ass' blood are references to inks of different composition, but that have in common the red color (blood) and its symbolic capacity to subdue and command spirits.

After this brief aside about blood, the binder mentioned in PGM XII. 96-106 is gum arabic, extracted from Acacia nilotica. Finally, the preservative used (all these inks share the next formula: [pigment + binder agent + preservative]) is wormwood. Besides its magical virtues, wormwood has insecticidal and antifungal properties, so it is not unreasonable to think that its purpose here is none other than to preserve both the ink and the surface to which it will be applied.

Thus, going back to the initial question, what do asbestos and calcium oxide contribute to the ink? Well, the use of asbestos, while retardant/fire-retardant, makes sense, considering that these inks need to be diluted for its use, that rainwater (which also has traditionally Ouranic properties; don't forget Sēt is a sky God) is another ingredient, and that calcium oxide, mixed in the ink, would cause the reed used for writing or the palette or recipient where the ink is stored to would catch fire without remedy.

But why make everything so complicated, only for adding calcium oxide? Because of its magical and symbolic transcendence. As a sterile, corrosive that can cause certain surfaces to burn if it comes into contact with water.

Magicians might have seen in this a manifestation of Set's overwhelming, destructive power, which they intended to use to curse others, to conjure and threaten daimonês or protect themselves.

To use this ink would be, in a certain way, to write with the fires of Sēt-Typhon Himself.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The antagonism between Horus and Sēt draws a dividing line that is not merely geographical. The essential meaning of this conflict is the opposition between civilization and barbarism, or between law and brute force. The symbol for Horus is the eye, for Sēt the testicles. Aggressive force is thus associated with procreative energy.

Another typically Setian notion is ‘Strength,’ which – like force – has positive connotations. Sēt is not a Satan; rather, he embodies an indispensable feature of life – one that would be literally castrated in his absence, barbarism, just as life would be blind without the Horus power of the eye. The contrast between eye and testicles represents an opposition between light (reason) and sexuality"

Jan Assmann, "The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs"

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymn to Sēt-Typhōn

O Sēt-Typhōn you who created everything with your thunderous voice, you who did first control Gods' wrath, you who hold royal scepter over the heavens, you who are midpoint of the stars above, you who are the Power of Waters, Bringer of winds and storms, who flash through the night, you who shake the rocks, who makes the walls quake, you who did walk across unquenched, crackling fire Sēt-Typhōn, you are the dreaded sovereing over the firmament, you who are fearful, awesome, threatening, obscure and irresistable, hater of the wicked, Sēt-Typhōn, you of the great dýnamis who hold sovereingty over the Moirai, Great God, almighty one, praised be you who dwell in Ombos, generations after generations.

#sēt#sutekh#sēt-typhon#graeco egyptian polytheism#polytheism#hymns and prayers#set#setesh#theoi#netjeru#gods#syncretism#kemeticism#kemetic

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

"(...) There is no doubt whatever that Typhon-Set was commonly identified with the sun in the Graeco-Roman period, and not infrequently with Abraxas. Similarly, there are many occasions when Jewish god-names occur in invocations of Typhon-Set. Identification of both Typhon and Dionysus with the Jewish god is also a common theme in late antiquity. Despite assertions by respected reference works, I am not inclined to epitomise every instance of this as anti-Semitism, even though such traits certainly existed. Set had a newly acquired demiurgic and solar-pantheistic status that was evidently sincere, this was neither necessarily or still less inevitably connected to ethnic politics. Similarly, Dionysus was a hugely popular god; identification of him with Eastern deities is perfectly in character, even if controversial due to the status of one in particular (...) Similarly, magical use of Jewish god-names occasionally incurs accusations of cultural appropriation. Again, the fact is that these names have become traditional; it is however extremely significant that late pagan use of them predates similar Christian usage. While apparently counter-intuitive to modern sensibilities, for an ancient pagan it was perfectly feasible to accommodate figures from henotheist or monotheist cultures. In some cases, particularly in Asia Minor, such accommodation reflected a deep respect for and involvement with Jewish culture, which however stopped short of conversion. On the other hand, there is no necessity to retain wholesale usage of these names; the conceptions of deity involved are not the sole province of any particular theology, and slavish reliance on past forms is no indication of magical competence. Having disposed of this issue in short order, the more immediately reIevant fact here is that Typhon-Set bore the status mentioned. In doing so, he demonstrates the mutability of views of the gods from one epoch to the next, it is a simple fact that perceptions of the nature and attributes of any ancient deity was subject to change. Consequently, the favouritism of one modern pagan grouping or individual for one or other past expression does not render those of another wrong per se. That Typhon-Set preceded Jehovah as premier deity of ceremonial magicians, often invoked under exactly the same names, is both historically true and potentially significant to various modern practitioners, and that is what matters here."

Jake Stratton-Kent, Geosophia or The Argo of Magic, vol. II

#sēt#set#sutekh#sēt-typhon#ia��#syncretism#ceremonial magic#jake stratton-kent#polytheism#greek magical papyri#pgm

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

| The Slayer | Devotional art to my beloved Set 🌩️

#Pls dont steal#nor repost#sutekh#sēt#khaire set-typhon!#dua set!#my art#egyptian polytheism#kemetic art#set#setesh#nut#ntrw#netjer#netjeru#kemetic

759 notes

·

View notes

Text

For desire it's the fuel for Illumination. Upgrade of an upcoming devotional icon for Sēt-Typhon. Still a WiP but I'm liking it a lot so far

#sēt#sutekh#set#set-typhon#my art#personal art#devotional art#pagan art#wip#egyptian polytheism#kemetic

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sēt-Typhōn

#Sēt#Sēt-Typhōn#Sutekh#Set#polytheism#art#my art#devotional art#graeco egyptian polytheism#Typhon#typhonian#nsfw?

30 notes

·

View notes