#Sollertinsky

Text

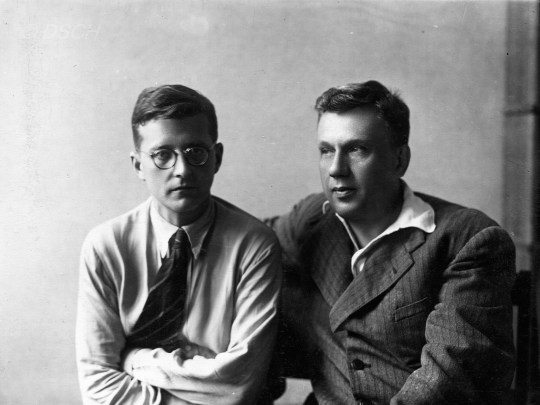

Pictured above is Dmitri Shostakovich with his best friend, Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky. The two of them met invariably in the years preceding, but struck up a friendship after hitting it off at a party of a mutual friend in 1927. The extroverted Sollertinsky paired well with the rather inward-facing Shostakovich. In particular, Shostakovich was taken by his witty, merry, and "entirely down-to-earth" personality. Sollertinsky was himself quite the scholar: he studied ballet, music, linguistics (he also spoke 26 languages), and philosophy, to name a few.

Sollertinsky, as well, was fiercely loyal to Shostakovich, as proven during the fallout in the wake of Muddle Instead of Music (an article published in January 1936 which dragged Shostakovich's opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk through the mud, resulting in much professional and personal turmoil for the composer). While many colleagues and indeed even friends were quick to jump on the Shostakovich-slandering bandwagon, Sollertinsky refused to do so, despite the harm it could have, and indeed did, cause his own career. Sollertinsky admired his friend so much that he broke a familial tradition of naming their firstborn sons "Ivan", and instead named his firstborn son "Dmitri".

The Second World War got in the way of their friendship, however. In June 1941, Nazi Germany broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact and invaded the otherwise neutral Soviet Union. The Wehrmacht set their sights on Leningrad very early on, and by August, had nearly fully encircled the city. Sollertinsky was evacuated with the staff of the Leningrad Philharmonia on August 22nd, and Shostakovich was at the train station to see him off. Sollertinsky was evacuated to Novosibirsk, while Shostakovich was evacuated to Kuibyshev later that year. The two kept up their communications via letter (as they had over the past seventeen years), and in 1944 were giddy at the possibility of both living in the same city again (Shostakovich had, at that point, been moved by the government from Kuibyshev to Moscow). However their excitement was short-lived, as soon after returning to Novosibirsk after visiting Moscow, Sollertinsky died of heart complications on February 11th, 1944.

His death left Shostakovich heartbroken, and one that he never truly got over. He would still talk fondly about his friend Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky to his friends, family, and colleagues well into the 1970s.

Photo courtesy of the DSCH Shostakovich Journal.

#dmitri shostakovich#shostakovich#classical music#history#soviet union#music#ussr#russia#second world war#ivan sollertinsky#sollertinsky

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

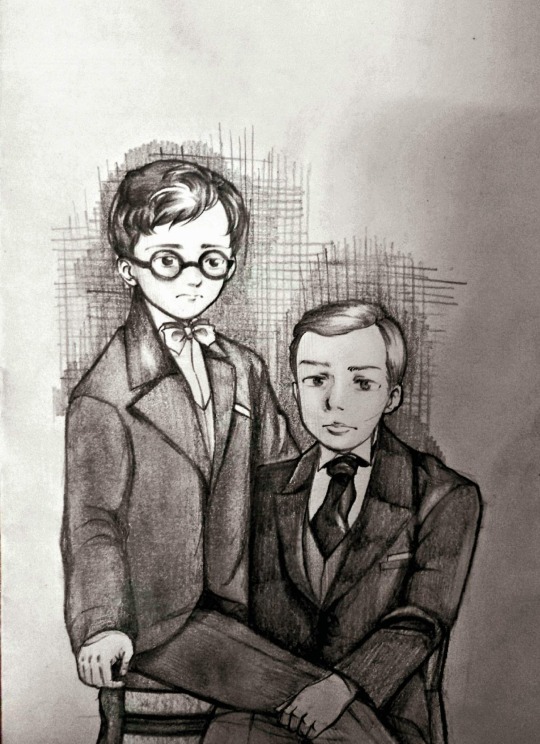

2021 vs 2023

#art#drawing#sketch#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical composer#classical music#music history#composer

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shostakovich-Sollertinsky letter translations- 1

Hello everyone!

so, some of you expressed interest in me sharing my translations of the letters from Dmitri Shostakovich to Ivan Sollertinsky, so I thought I’d start sharing them here! They range from 1927 to 1944 so I’m not going to Dracula Daily it and send them in real time lol, but I think I can do one a day. I’m not a native or fluent Russian speaker; just an intermediate-level learner, so while I’ve translated these to the best of my ability, I may miss out on some cultural and linguistic nuances. I researched and tried to translate idioms and cultural references as best as I could, but at the end of the day, please keep in mind my translations aren’t perfect. In addition to the published Russian letters, which my translations are based on, there’s a German-language translation that’s been published, so if you happen to speak German or Russian, I would highly recommend checking those out. I will also include footnotes as they appear in the published book when relevant, as well as some historical context from my own research when applicable. Because the first letter is very short, I will start today with the first two letters. These posts will be tagged #sollertinsky letters.

For context, Dmitri Shostakovich formally met Ivan Sollertinsky in 1927 at the home of the conductor Nikolai Malko. Sollertinsky would go on to be one of Shostakovich’s closest friends, until his untimely death in 1944 from heart complications. This first letter is undated:

"I have urgent business for you. Call me when you have 15-20 minutes to talk to me. D. Shostakovich."

Footnote- Written on the front side of the card- "Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, 9 Marat Street, apartment 7. Telephone 496-37." Obviously, the composer wrote the note without knowing where Sollertinsky's house was. As it is only addressed "to you" (translation note: the formal form of “you," вы, which is used mainly for acquaintances and superiors, rather than the informal “ты,” which is used for close friends), this was likely the first letter from Shostakovich to Sollertinsky.

Letter 2- 20th August 1927, Detskoe Selo

My dear Ivan Ivanovich, I was extremely happy to receive your postcard. In such a small space, you combine so many needed considerations and witticisms that I am amazed. I did not write to you because I was in a bad mood. The Muzsektor [Music Sector] sent me only 500 rubles the day before yesterday for my loyal sentiments. Due to this, my mood improved, and I decided to write to you. Tomorrow I'm going to Moscow. The Muzsektor sent me a telegram for a demonstration of my revolutionary music. On my return, I will write of my summer adventures in detail. I recently received a letter from Malko, in which he warns me of an imminent break with him and, like Chamberlain [1], accuses me of such a break. Progress is being made on "The Nose," as well as my German. In my next letter, probably by Wednesday, I will begin with the words "mein lieber Iwan Iwanowitsch." Your D. Shostakovich.

1- “Chamberlain” refers to Chamberlain Ostin, a British statesman. (Footnote)

Translation note- It’s unknown how much time passed between this letter and the last one, but here, Shostakovich uses the informal ты. Between this letter and the last one, he and Sollertinsky drank a Bruderschaft, a drinking ceremony performed to commemorate friendship and switching from the formal to informal address.

Context note for letter 2- at this point, Shostakovich briefly tried to teach Sollertinsky piano, and Sollertinsky- a polyglot who spoke over 20 languages- tried to teach him German. Neither learned much.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#composer#composers#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical music#history#music history#soviet history#sollertinsky letters#translation#russian history

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivan Sollertinsky (Research so far)

Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, born December 3rd 1902, Vitebsk, Belarus, was a Soviet Polymath. Sollertinsky was an expert in theatre and languages but he is best known for his musical accomplishments: work in music field as a critic and musicologist. He was a professor at the Leningrad Conservatory and the Artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. During these times he was an enthusiast and advocated Mahler’s music in the USSR. Sollertinsky had exceptional memory according to his coetaneous’; he was able to speak 32 languages, some of which were dialects.

After moving from Vitebsk to Leningrad, he graduated from Leningrad University with a degree in Romano-Germanic philology. In 1927, he became close friends with Shostakovich, and is known for introducing him to the works of Mahler that greatly impacted his style of composing and some of his compositions. Examples being his opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and his 4th symphony. Shostakovich wrote letters to Sollertinsky; letters date from early 1927- the 4 few days following Sollertinsky’s premature death in Novosibirsk.

In 1936, Shostakovich faced his first denunciation for the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. Pravda launched a series of attacks calling it “Muddle instead of Music.” Sollertinsky greatly supported the opera and even wrote that it was an “enormous contribution to Soviet musical culture” in 1934 for a review in “Workers and Theatres”. However, in Pravda, he was termed as “The troubadour of formalism”. After the denunciation, criticism grew on the opera which resulted in accumulating pressure on Sollertinsky to withdraw his previous statements. However, he did not do so until Shostakovich told him to, fearing for the safety of Sollertinsky.

Sollertinsky contracted diphtheria in 1938 which temporarily paralysed his arms, legs and jaw. During this time, he married his third wife Olga Pantaleimonovna. He fathered a son with her, whom he named Dmitri Ivanovich, after Shostakovich: this broke the generation-long tradition where the son would have their first name as Ivan. During the 4 months in which he was hospitalised, Sollertinsky studied Hungarian.

Soon after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Sollertinsky evacuated from Leningrad to Novosibirsk. In Novosibirsk, he engaged himself in a number of creative works, give lectures and speeches and to attend other cultural/artistic events. Even though him and Shostakovich didn’t see each other frequently during the war years, the Soviet composer, Vissarion Shebalin arranged for Sollertinsky to teach a course of music history at Moscow Conservatory. This was where Shostakovich was living at the time. Sollertinsky stayed in Moscow briefly to give a speech upon the death of Tchaikovsky in 1934. After, he moved back to Novosibirsk in the same year, there he gave a speech upon the premiere of Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony. This would be the last speech he would give before his death.

Doubts over the cause of Sollertinsky’s death persist to this day: according to a Wikipedia article, “On the night of February 10, 1944, Sollertinsky, feeling unwell, stayed at the house of the conductor A.P. Novikov. He died in his sleep at the age of 41”. The Russian newspapers say he died of a heart illness but rumours spoke of his having been murdered by the NKVD. Shostakovich expressed a heartfelt and touching message portraying his feelings for his dear friend:

“I cannot express in words all the grief I felt when I received the news of the death of Ivan Ivanovich. Ivan Ivanovich was my closest and dearest friend. I owe all my education to him. It will be unbelievably hard for me to live without him.”

Shostakovich dedicated his Second Piano Trio to the memory of Sollertinsky. He started this in 1943 and completed it within the following year in August. It was premiered on 14th November 1944. Sollertinsky’s death greatly impacted Shostakovich, he struggled with composing and fell into depression in the following months. One time the composer said that “It seems to me that I will never be able to compose another note again.” He was awarded the Stalin prize for the trio.

The relationship between Shostakovich and Sollertinsky was exceptional and heart warming. The two were inseparable and were always there for each other in times of need and to comfort one another. Sollertinsky was indeed an important and influential aspect of Shostakovich’s life.

-Sources: DCSH Journal, Wikipedia

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

i must admit that this insult about rachmaninoff's first symphony from cesar cui is alright

but like, no one holds a candle to ivan ivanovich sollertinsky

#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#rachmaninoff#cesar cui#cui#rare insults#insults#images sources: first is from wikipedia second is from a tchaikennugget video

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

From a picture of Shostakovich and Sollertinsky

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is your favorite picture of yourself?

and what is your favorite picture with others?

Hmmm, can't really choose.

Maybe these, I don't know why though.

With others...

Me and Sollertinsky. I miss him...

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

there are 19 fics tagged shostakovich/prokofiev on ao3, 18 of them were written by the same person, some of them are in vietnamese, and not a single one of them is in russian (russians ship shostakovich/sollertinsky which has more basis in, uh, canon). you've heard of bandom rpf now get ready for soviet composer rpf

#what was i doing at the devil's sacrament? well finding out what is the most popular classical music rpf ship of course#for the record it's chopin/liszt which was not surprising

1 note

·

View note

Text

On that Puss in Boots brainrot, so here’s a list nobody asked for that I can’t get out of my brain

Classical Music I think characters would appreciate for one reason or another, usually because of the story or impetus behind its writing or meaning, in an increasingly longer title

Disclosure: these are just my thoughts. Feel free to comment, reblog, add, discuss! I’m just some dude on the Internet talking about fictional characters, have fun with it!

Under a cut cuz it’s long and there’s a lot of video links

My goal was to explore the music a bit more, get into the reasoning behind its existence, and how that story might play into why I think these characters would appreciate to it. (Sometimes, though, it’s a bit more simple than that)

Gotta start with our favorite, fearless Hero

Puss

“Heroic” Polonaise in Ab, Frederic Chopin

youtube

You’ve probably heard this one before, as it’s one of Chopin’s most popular works. Some research, however, I found that Chopin apparently didn’t like attaching descriptive titles to his work - “Heroic” was added by the modern listeners and music historians. The piece was written during the revolutions of 1842, and Chopin’s love at the time, Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil - known by her pen name George Sand - wrote that the piece had the energy and passion needed for the French Revolution. It seems their correspondence was a part of why it gained the name “Heroic” later in life.

While initially I chose this piece because “haha heroic for the hero,” I found I had a “wait a minute” moment reading about how the name was added later on. If having a title and being perceived a certain way doesn’t describe this cat (at least, for most of the film), then I watched the movie wrong. But the energy and vigor with which it clearly gets performed with, the emotional weight it can carry for so many people, during a time of political upheaval…I think Puss would resonate with that, being a Robin Hood himself.

Death

I have to talk about my boyfriend my boyfriend next, of course, being the reason for Puss’ journey in the first place.

Piano Trio No 2 in e, Dmitri Shostakovich

youtube

(This is likely the most difficult piece to listen to and talk about, tonally and emotionally. It’s incredibly dark. I’ve linked the fourth movement, because it beautifully synthesizes all the themes and ideas from the previous three, but if you have the time and spoons to spare I highly recommend listening to the entire composition start to finish.)

I’ve actually mentioned this piece specifically in this context on my blog before, but now I can elaborate a bit more. Shostakovich was heavily scrutinized by Stalin’s regime, and his works and performances were subject to the whims of the government for most of his life and beyond. He often had to write as carefully as he could so as to appear to be aligned with those in power, but often would write using themes and motifs counter to what the government would have liked.

The Piano Trio No 2 in e was part dedicated to Shostakovich’s friend and mentor, Ivan Sollertinsky - who passed away during the writing of the piece -, and part dedicated to the Jewish prisoners of war during WWII. Apparently, Shostakovich heard they were made to dig their own graves, and then dance on them. The fourth movement I linked makes the most clear use of a Yiddish-sounding theme in the violin, and the tormented nature of the composition is undeniable. As a character who clearly values life, I feel Death would appreciate the dedications and thought behind the piece, but also enjoy how beautifully macabre it sounds.

Kitty

Kitty was difficult for me, to be honest. Trying to find something that captures her arc is tricky, as I don’t personally know of much music that discusses trust, both in general, and the way she experiences it. But I do think she has a lot of pride in herself as a strong individual, and has pride in her work, which is why I went with

Danzon No 2, Arturo Marquez

youtube

The Danzon is a partner dance that developed from the Habanera, and is an active musical form in Mexico today. Marquez’s Danzon No 2 takes this to the next level, in a high energy and blistering work that will leave you humming it for hours. This piece is important as a modern work, as its popularity brought about not only greater respect for Mexican composers, but caused people (read: Western classical musicians) to explore and perform more Hispanic literature, especially Marquez’s. This is also the only piece on this list by a living composer, premiered in 1994.

Being of Hispanic descent, I felt Kitty would find pride in her nation’s music and dances becoming popular across the world due to the popularity of this piece. We also know this cat likes to dance, and it’s incredibly difficult to resist when listening to it.

Perrito

Nimrod, from Enigma Variations, Edward Elgar

youtube

The Enigma Variations are small vignettes written for Elgar’s friends. The most recognizable and known of the Variations, Nimrod is an absolutely gorgeous piece of music. The title “Nimrod” is a play on words - the friend in question’s name was Jaeger; Jaeger means “Hunter” in German; Nimrod was a biblical hunter of fame.

Jaeger was not only a friend, but Elgar’s publisher. He would offer advice and helped Elgar rework sections of music here and there. Jaeger’s presence as a confidant is shown in the slow moving lines, reflecting on years of support. If Perrito doesn’t embody dedicated friendship, support, and love in this way, then again - I must have watched the movie wrong. He learns to sit and listen through his time with Puss and Kitty, and this movement almost forces you to take a moment and really sit, listen, and appreciate what you’re hearing.

Goldi

Symphony No 1 in c, Johannes Brahms

youtube

I literally cannot think of a better “just right” story in music history than this piece. Brahms was known for destroying his manuscripts of works and sketches he didn’t approve of - he famously ached and pained over writing his first symphony, despite having already solidified himself as a successful composer. He was afraid of the looming shadow of Beethoven, who he had already been compared to by audiences and critics. Some records say it took 14 - others upwards of 21 - years for him to finish this first symphony, and even still he trialed it before publishing.

It seems things ended “just right” for this piece, after all. It was received positively, and spurred him on to compose his second symphony in about a year after the first. Music historians have pointed to this as a shift in the romantic symphonic style. While comparisons to Beethoven were still made (Brahms apparently being frustrated by this - not because of them, but because he felt it was obvious), Brahms had carved his own path of symphonic writing.

Okay I’m done here that’s as far as I got

If you made it down to here, congratulations! This idea came about because, uh, I thought it’d be fun! It gave me a chance to research a bit, and it was fun to try and think of music these characters that I can’t stop rotating in my head would appreciate.

Music is so universal, you could probably find a reason in any piece to give it to anyone, but that’s also what makes it so great. I am by no means an authority, and if you read all this way, feel free to let me know what you think!

Thanks for your time.

#puss in boots the last wish#puss in boots#kitty softpaws#perrito#puss in boots death#Goldilocks#music#profblogson#death puss in boots

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shostakovich 24 Preludes Op. 87 No. VIII (Noten, sheet music)

Shostakovich 24 Preludes Op. 87 No. VIII (Noten, sheet music)PreludeFugueShostakovichBest Sheet Music download from our Library.BiographyPlease, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!- His early years:- First complaint:- The war:- The last years of Stalin and the thaw:- Shostakovich connection to the party:Shostakovich last years:* His work:- Shostakovich character:- Orthodoxy and revisionism:

Shostakovich 24 Preludes Op. 87 No. VIII (Noten, sheet music)

Prelude

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YUjZ0_kE_hs

Fugue

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Btg4CX_TMl4

Shostakovich

Biography

Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich (Russian: Дми́трий Дми́триевич Шостако́вич) (Saint Petersburg, September 25, 1906 – August 9, 1975) was a Russian composer who lived during the Soviet period. He had difficult relations with the Communist Party of the USSR (CPSU), which publicly denounced his music in 1936 and 1948.

Publicly, however, he was loyal to the Soviet regime, accepting a CPSU card in 1960 and becoming a member. of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. His attitude toward the communist regime and the Soviet state has been the subject of bitter political and musical controversies, and it has been hotly debated whether Shostakovich was a clandestine dissident against the regime.

After an initial period of musical avant-garde, Shostakovich's style drifted towards a late musical romanticism in which the influence of Mahler is combined with that of the Russian musical tradition, with Mussorgsky and Stravinsky as important references.

Shostakovich integrated all these influences, creating a very personal style that even evolved towards atonality in some works. Shostakovich's music often includes sharp contrasts and grotesque elements, with a prominent rhythmic component. In his work, his cycles of fifteen symphonies and fifteen string quartets stand out; Furthermore, he composed a lot of chamber music, several operas, six concertos and film music.

Today Shostakovich is considered by many critics to be the most outstanding composer of the 20th century.

- His early years:

Born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Shostakovich was a child prodigy as a pianist and as a composer. From an intellectual family in which political influences were not lacking, in his teenage years he witnessed the 1917 revolutions and wrote some commemorative works for the victims of the revolution.

In 1922, he was admitted to the Petrograd Conservatory, where he was taught by Alexander Glazunov. There he suffered the consequences of his lack of interest in politics, and in 1926 he failed his test on Marxist methodology. The first musical work to achieve international fame was composed at the age of 19: Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1925), which he presented as a graduation work and which would win first prize for composition.

When the work was premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra on May 12 of the following year, jubilation seized the artistic circles of the young Soviet Republic. The success of the symphony in Europe and America corroborated the relief of a new talent and, what was even more decisive, of the first great composer of the "new Russia".

Upon graduation, he embarked on a dual career as a composer and pianist, but his cold playing style was not widely appreciated. He would soon limit his performances basically to those in which he presented his own works. In 1927 he composed his second symphony (called Dedication to October).

While composing this symphony, he began writing his satirical opera The Nose, based on a short story by Nikolai Gogol. In 1929, his opera was branded “formalist” by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians, one of the musicians' associations in the USSR.

In 1927 he also began his relationship with Iván Sollertinsky, who would be his best friend until his death in 1944. Sollertinsky introduced Shostakovich to the work of Gustav Mahler, who was to have a great influence on his music starting with his Fourth Symphony.

Towards the end of the 1920s Shostakovich collaborated with the TRAM, a proletarian youth theater in Leningrad.

Although he developed little activity, the position protected him from ideological attacks. During this time he devoted himself intensely to composing his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which premiered in 1934 and was immediately successful, although it was later banned in his country for twenty-six years.

In 1932, he married his first wife, Nina Varzar. Although early difficulties led to their divorce in 1935, the couple reconciled shortly thereafter.

- First complaint:

In 1936 Shostakovich's bliss ended when Pravda published a series of attacks on his music. In a famous article entitled Chaos Instead of Music, which has been attributed to Stalin, Lady Macbeth was condemned in drastic terms, accusing her of anti-popular snobbery, pornophony and formalism.

The performances of the opera, which were taking place simultaneously in several theaters, were suspended and the composer saw his income and his prestige plummet, in a context in which political repression was wreaking havoc. It was the time of the great purges, in which friends and acquaintances of the composer were sent to prison or executed. The only consolation for him in this period was the birth of his daughter Galina in 1936; His son Maxim was born two years later.

After some rehearsals in December 1936, Shostakovich withdrew his Fourth Symphony, without actually premiering it, probably for fear of the reaction it might provoke. The symphony, one of Shostakovich's most tragic, could have fallen like a bomb in the climate of terror that the Soviet authorities sought to cover up with bright and optimistic works of art. Requiring a huge orchestra, the work was not premiered until 1961 and sadly remains to this day one of Shostakovich's lesser-known symphonies.

His Fifth Symphony, premiered in 1937, is musically conservative. In it the tragic emotion of the slow movements is combined with an electrifying dynamism. The final apotheosis of the work has been interpreted as optimistic by some, as a mockery of a forced joy by others.

Fortunately for Shostakovich, the regime understood the former and praised the play, which was a great success in his country. Although it received appalling reviews in the West, Symphony No. 5 remains one of the most popular symphonies of the 20th century. It was at this time that Shostakovich began writing string quartets. His chamber work allowed him to experiment and express ideas that would have been unacceptable in his more popular symphonic pieces.

In September 1937, he began teaching composition at the conservatory, which brought him some financial stability but also interfered with his own creative work.

- The war:

When Germany attacked Russia in 1941, Shostakovich initially remained in Leningrad during the siege and began his Seventh Symphony, known precisely as Leningrad. In October 1941, the composer and his family were evacuated to Kuybyshev (now Samara), where he finished his work, which was adopted as a symbol of Russian resistance both in the USSR and in the West.

In the spring of 1943 the whole family moved to Moscow. From that time is the Eighth Symphony, an extensive and obscure work that was not approved by the authorities. The work was rarely interpreted, despite its exceptional quality in the opinion of much of today's critics.

From the Ninth Symphony (1945) the authorities expected music appropriate to the historical resonances of the symphonic number 9 and the victorious march of the war against Germany.

Those expectations were frustrated by the composer with a strange symphony, with allusions to Rossini and moments that seem pure circus music. In 1948 Shostakovich and other composers were convicted of Zhdanovian formalism, their compositions were banned, and the privileges enjoyed by the composer's family were withdrawn. Only in 1958, after Stalin's death, did the CPSU find the criticism unfair and lift the bans on the compositions condemned in the 1948 resolutions.

- The last years of Stalin and the thaw:

In the years following his 1948 conviction, Shostakovich composed official papers to secure his official vindication, while also working on serious "desk drawer" work. Among these were the Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, dedicated to David Óistrakh and which would not be released until seven years after it was written, and the song cycle From Jewish popular poetry (Op. 79), a work that has caused controversy. for its undoubted political connotations.

Some have seen in this song cycle a heroic act of critical affirmation against Russian anti-Semitism, then promoted by the Soviet authorities. Laurel Fay says instead that Shostakovich was trying to conform to official policy by taking popular song as his inspirational theme. The last three songs of the cycle, in which the situation of the Jews "in the new Russia" is glorified, seem to abound in Fay's interpretation.

The restrictions placed on Shostakovich's music and his living conditions improved in 1949, when Shostakovich was sent with a delegation of Soviet personalities to the United States. That same year, he wrote his cantata Song of the Woods, which praised Stalin as the "Great Gardener." In 1951 the composer became a deputy of the Supreme Soviet.

Stalin's death in 1953 was followed by the Tenth Symphony, one of his most popular compositions, often described as an optimistic tragedy. The symphony contains the famous "Shostakovich theme", which derives from the initials of the composer's first and last name, transliterated into German, that is, "D. Sch.".

In German music notation, the series D–Es–C–H represents the sounds D natural, E flat, C natural, B natural. In the third movement of his Tenth Symphony, Shostakovich uses that DSCH motif together with another representing the name "Elmira", in homage to his student Elmira Nazirova. Centuries before, Johann Sebastian Bach had used the same resource with the letters B–A–C–H which, also in German notation, represent the sounds B flat, A natural, C natural, B natural.

During the forties and fifties, Shostakóvich had a very close relationship with two of his students: Galina Ustvólskaya and the aforementioned Elmira Nazirova. Ustvolskaya was a student of the composer from 1937 to 1947.

The nature of their relationship is unclear: while Rostropovich describes her as "tender," Ustvolskaya said in a 1995 interview that she had declined a marriage proposal from him in the 1950s. The relationship with Nazirova seems to have been one-sided, according to the letters he wrote to her, and can be dated between 1953 and 1956. In the background was Shostakovich's open marriage to Nina Varzar, who died in 1954. Shostakovich married his second wife Margarita Kainova in 1956; three years later they divorced.

The Eleventh Symphony of 1956-1957 is titled 1905 in explicit reference to the revolutionary events that occurred that year in Russia Russian Revolution of 1905. Some have also wanted to see in this work a reference to the Hungarian Revolution.

- Shostakovich connection to the party:

The year 1960 marked another turning point in Shostakovich's life: he joined the Communist Party. This event has been interpreted as a show of compromise or cowardice, or as a result of pressure.

In this period he was also affected by poliomyelitis that he began to suffer in 1958.

Shostakovich's musical response to these personal crises was his Eighth String Quartet, which like his Tenth Symphony incorporates various codes and quotations.

In 1962, the composer married for the third time. The bride, Irina Supinskaya, was only 27 years old. That same year Shostakovich returned to the theme of anti-Semitism in his Symphony No. 13, Babi Yar.

The symphony is a choral work based on poems by Yevgeny Evtushenko, the first of which commemorates a massacre of Jews during World War II. There are conflicting opinions regarding the risk assumed by the composer when premiering this work. Evtushenko's poem had been published and had not been censored, although it was controversial. After the symphony's premiere, Evtushenko was pressured to add a stanza to his poem saying that Russians and Ukrainians had died alongside the Jews at Babi Yar.

Shostakovich last years:

In the last years of his life, Shostakovich suffered from a chronic illness: his meliitis continued to worsen, and he began to suffer from heart problems in the mid-1960s. Most of his later work—his Fourteenth and Fifteenth Symphonies, and later quartets—are dark and introspective. They attracted much favorable criticism from the West, as they did not have the performance problems that his earlier works, which were more public pieces, had.

Shostakovich, who had been a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer on August 9, 1975. He was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, Russia. His son, the pianist and conductor Maxim Shostakovich, was the dedicatee and first performer of several of his works.

* His work:

Among his best-known works are the Fifth and Tenth symphonies, and the Eighth and Fifteenth quartets. His music shows the influence of several of the composers he most admired: Johann Sebastian Bach in his fugues and his passacaglias; Beethoven in his last quartets; Gustav Mahler in his and Berg's symphonies in the use of musical codes and quotations.

His works are largely tonal in the Romantic tradition, but with elements of atonality, polytonality, and chromaticism. In some of his later works (for example the Twelfth Quartet) he used twelve-tone series. Many commentators have noted a differentiation between his work before the 1936 criticism and the more conservative subsequent work.

Volkov commented that Shostakovich took on the role of the yurodivy, or enlightened one. The yurodivy plays an important role in Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov, which Shostakovich admired and for which he produced a new orchestration.

- Shostakovich character:

Shostakovich was in many ways an obsessive man: according to his daughter, he was “obsessed with cleanliness” (Árdov p. 139); he synchronized the clocks in his apartment; he regularly sent letters to himself to test how well the postal service was doing.

In Wilson's book Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, 26 references to his nervousness are listed. Yuri Lyubimov comments that "the fact that he was more vulnerable and receptive than other people was undoubtedly an important component of his genius" (Wilson p. 183). In the last years of his life, Krzysztof Meyer recalled, "his face was a bag of tics and gestures" (Wilson p. 462).

When he was in a good mood, sport was one of his main distractions, although he preferred to stay as a spectator or referee to participate (he was a qualified soccer referee). He also liked card games, particularly solitaire, and chess.

Both dark and light sides of his personality were made evident by his fondness for satirical writers such as Gogol, Chekhov, and Mikhail Zoshchenko (Wilson p. 41). The influence of the former can be seen in his letters, in which he makes perverse parodies of Soviet officials.

Shostakovich was shy by nature: Flora Litvinova said that he "was incapable of saying 'no' to anyone" (Wilson p. 162). This meant that he was easily persuaded to sign official statements, including a public denunciation of Andrei Sakharov in 1973.

- Orthodoxy and revisionism:

Shostakovich's response to official criticism is debatable. It is clear that he was apparently part of the State. He made speeches, or at least read them, and signed articles expressing the government's line of thought. It is also generally accepted that he disliked the regime, a view confirmed by his family, his letters to Isaak Glikman, and the satirical cantata "Rayok," which ridicules the anti-formalist campaign and was kept hidden even after death. of the.

What is uncertain is the extent to which Shostakovich was trying to show his opposition to the regime through his other music. The revisionist point of view was expounded by Solomon Volkov in the book Testimony of him in 1979, which Volkov presented as if they were Shostakovich's memoirs. The book argues that several of the composer's works have coded anti-government messages.

That Shostakovich incorporated quotes and allusions into his work is evident, as is his musical signature DSCH. His longtime collaborator, Yevgeny Mravinsky, said that "Shostakovich frequently explained his intentions with images and connotations" (Wilson p. 139). The revisionist perspective has been supported by the composer's children, Maxim and Galina, and by several Russian musicians. Widow Irina generally supports this thesis, but claims that Testimony is a forgery by Volkov.

A prominent revisionist was the late Ian MacDonald, an expert on The Beatles and Shostakovich. His book The New Shostakovich interprets Shostakovich's music in a conspiratorial key, almost every eighth note having a meaning. Anti-revisionists deny the authenticity of Testimony and allege that Volkov compiled various articles, gossip, and possibly some information obtained directly from the composer.

More generally, they argue that Shostakovich's significance lies more in his music than in his life, and that seeking political messages does not enhance but rather detract from the artistic value of the composer's music. Among the anti-revisionists stand out Laurel Fay and Richard Taruskin.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

ngl schostakovich and sollertinsky look very cute together

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite its cuddly appearance

beneath those fluffy feathers, the Shostakovich is what we call

a bird of prey

#shostakovich#sollertinsky#classical music#shosty#dmitri dmitrievich shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#dsch go home you’re drunk#dsch posts again#russian composers

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been preparing to contact the Shostakovich archives and just realized as I was re-reading about their holdings that the letters to Sollertinsky aren’t in the state archives, but still in the personal possession of Sollertinsky’s son. My work just got exponentially more difficult. Like, I can’t just go visit him on a summer-long research grant. Can I get Harvard to fund me moving to St. Petersburg for 2-3 years so I can build trust and friendship with Dmitri Sollertinsky? I’d do it.

#seriously what do you do in this situation#how do you scholar this#really in a drop everything and move to st. petersburg mood already#if it didn't mean abandoning my partner and our lease i would heavily look into getting a job there#it's been my dream for 6 years anyway#ah#well#russia#research#scholarship#my work#shostakovich#sollertinsky

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s them it’s my favorite guys

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical music#composer#classical composer#composers#music history#art#drawing#sketch

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francis and Alan’s relationship is a bit like Shostakovich and Sollertinsky…

Close friends? Yes. Are always there for each other? Yep. Can’t bare to live without one another? Definitely. Has one person who likes literature? Certainly.

I low-key ship Francis and Alan😳

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Reposted from @orrestofw ORRESTO 003/2019 Сделано вручную в Санкт-Петербурге, Россия. Handbuilt in Saint-Peterburg, Russia. @columbus_official @sramroad @fulcrum_wheels @sollertinsky @rossimas_d #orresto_fw #steelisreal #influxwetrust #roadbicycle #road #framebuilding #cyclocross #шоссе #сделановроссии #сделановсанктпетербурге #сделановручную #madebyhand #sramroad #fulcrumwheels #ritcheylogic #continentaltyres https://www.instagram.com/p/Ch82_ofu_am/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#orresto_fw#steelisreal#influxwetrust#roadbicycle#road#framebuilding#cyclocross#шоссе#сделановроссии#сделановсанктпетербурге#сделановручную#madebyhand#sramroad#fulcrumwheels#ritcheylogic#continentaltyres

23 notes

·

View notes