#Sumie Tanaka

Photo

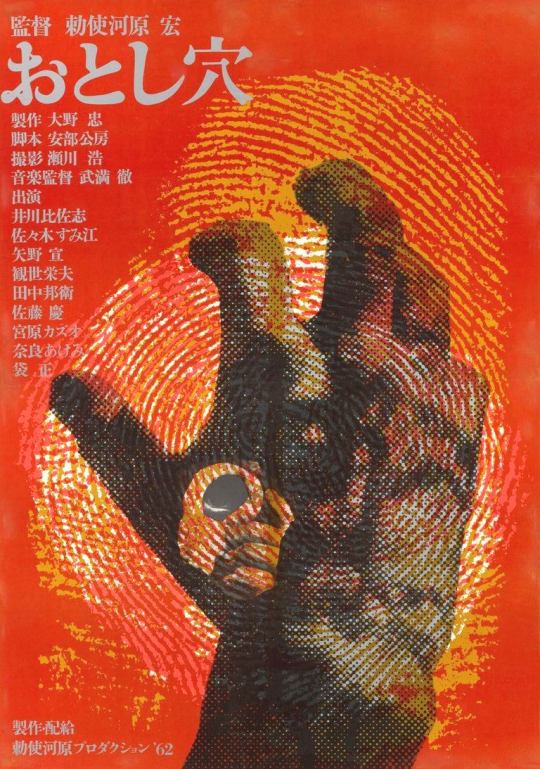

Pitfall / Otoshiana (1962, Hiroshi Teshigahara)

おとし穴 (勅使河原)

11/6/22

#Pitfall#Otoshiana#Hiroshi Teshigahara#Kobo Abe#Japanese#New Wave#Japanese New Wave#60s#Hisashi Igawa#Sumie Sasaki#Sen Yano#Hideo Kanze#Kunie Tanaka#Kei Sato#crime#fantasy#ghosts#afterlife#murder#mine#ghost town#mining#working class#union#power struggle#Toru Takemitsu#deserters#mistaken identity#doppelganger

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

since i can't find one and need to know who to aim for...

list of reverse: 1999 jp dub cast (updated for 1.4)

210 - hirose daisuke

37 - iguchi yuka

6 - nakamura yuuichi

a knight - hayami show

alien t - fukuhara anjou

an-an lee - sakura ayane

apple - hirakawa daisuke

arcana - koshimizu ami

baby blue - suzaki aya

balloon party - minase inori

bette - kanzaki maki

bkornblume - ueda reina

blonney - saito shuka

bunny bunny - ozawa ari

charlie - matsuda satsumi

centurion - ikuta teru

charlton - nomiya kazunori

click - uchiyama kouki

constantine - tanaka atsuko

cristallo - aimi

darley clatter - yada kouhei

diggers - tachibana shinnosuke

dikke - kawasumi ayako

door - shimizu sakuma

druvis iii - ishikawa yui

eagle - noguchi ruriko

enigma - umehara yuuichirou

erick - tanaka chiemi

eternity - fairouz ai

forget me not - suwabe junichi

horropedia - okitsu kazuyuki

isabella - kino hina

jessica - waki azumi

john titor - konishi mai

kaalaa baunaa - ootsubo yuka

kanjira - akasaki chinatsu

kumar - fujitou chika

la source - yuzuki kazuka

leilani - tachibana yuki

lilya - kitamura eri

lucy - suwa ayaka

matilda - itou ayasa

medicine pocket - hanae natsuki

melania - ueda kana

mesmer jr. - kudou haruka

mondlicht - tsumugi risa

ms. moissan - kohara riko

ms. new babel - uchida maaya

ms. radio - odashima kazami

necrologist - wakayama shion

nick bottom - satou fumiya

oliver fog - nagatsuka takuma

onion - horikawa kaede

pavia - nozu

pickles - saito soma

poltergeist - maekawa ryouko

rabies - takagaki katsuhisa & mugiho anna

regulus - yamamoto nozomi

ring - sakakihara yuki

satsuki - touyama nao

schneider - yuuki aoi

shamane - yasumoto hiroki

sonetto - uchida shu

sophia - kobayashi yuu

sotheby - itou miku

sputnik - toba yuuko

sweetheart - tanaka rie

tennant - takahashi chiaki

the fool - nitta kyousuke

tooth fairy - uesaka sumire

ttt - sumi tomomi jiena

twins sleep (lisa & louise) - kamitaka suzuka

vertin - takamori natsumi

voyager - hondo kaede

x - toki shunichi

z - liyuu

зима - totto

#reverse 1999#SUWABE. SUWABE WHY AREN'T YOU PLAYABLE.#this is like... so many characters#surely not all of them are available upon release??#i think i'm even missing some like i can't find cv info on voyager anywhere#(eta: have added voyager)#none of the 1.1 and beyond charas are here either#so these must really all be 1.0? wild#why does tennant have to be 5* anyway i want to main tennant :(#anyway it's 5 so far i think#5 hpmi cvs appear (doppo dice jakurai nemu ichijiku)#enough for me to give it a shot lol#crab files

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

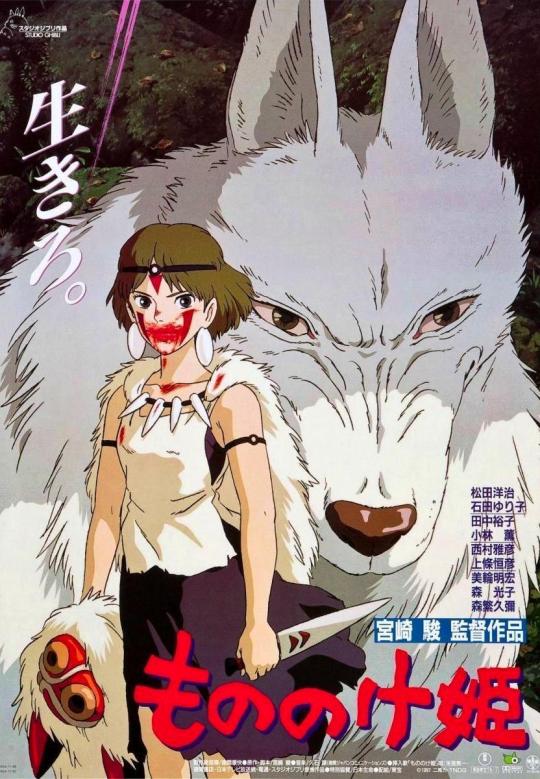

Title: Princess Mononoke

Rating: PG-13

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

Cast: Youji Matsuda, Yuriko Ishida, Yûko Tanaka, Kaoru Kobayashi, Masahiko Nishimura, Tsunehiko Kamijô, Akihiro Miwa, Mitsuko Mori, Hisaya Morishige, Sumi Shimamoto, Tetsu Watanabe, Makoto Satō, Akira Nagoya, Kei Iinuma, Tsuzuki Kayako, Kimihiro Reizei

Release year: 1997

Genres: fantasy, adventure, drama

Blurb: Ashitaka, a prince of the disappearing Earth people, is cursed by a demonised boar god, and must journey to the west to find a cure. Along the way, he encounters San, a young human woman fighting to protect the forest, and Lady Eboshi, who is trying to destroy it. Ashitaka must find a way to bring balance to this conflict.

#princess mononoke#pg13#hayao miyazaki#youji matsuda#yuriko ishida#yuko tanaka#yûko tanaka#kaoru kobayashi#masahiko nishimura#1997#fantasy#adventure#drama

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

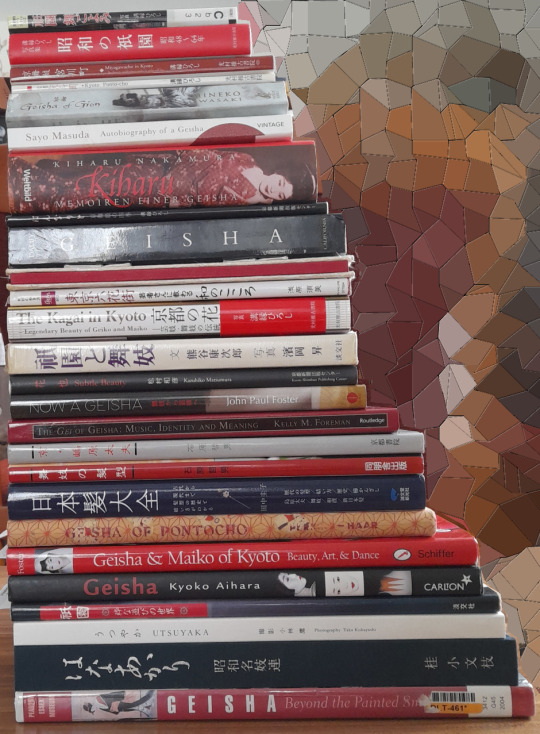

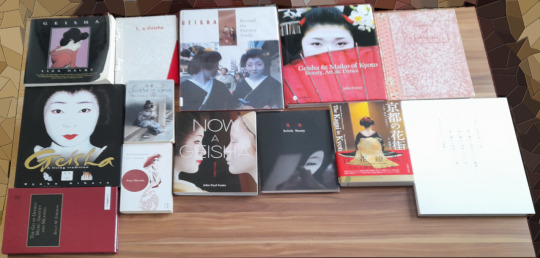

Karyukai Book collection, 2022 edition

It’s been a while since the last book feature on this blog. The collection has grown, maybe you are also interested in Gei-/Maiko related books and find this helpful.

Category 1: Japanese only or Japanese with only little English

…Hiroshi Mizobuchi - Showa no Gion: b&w photos depicting life in Gion Kobu in the 1970’s and 80’s. Captions are entirely in Japanese, but easy to translate, since they are mostly dates and names. At the end of the book, there are few pictures from the 1930’s and 40’s.

…Sumi Asahara - Tokyo Rokkagai: Interviews with Tokyo Geisha, history and map of the main six Tokyo Kagai, old and new photos. Books on the subject of Tokyo Geisha are fairly rare, so this is a good source of information.

…Hiroshi Mizobuchi - Hannari Kyo Maiko no Shiki: photos of the seasonal events and celebrations in the Kyoto Hanamachi, with Map and full Ochaya list.

…Keiko Tanaka - Nihongami taizen: despite featuring Maiko Fukuno on it’s cover, only a little part of it deals with Maiko Nihongami. It has a bit of Tayu/Sumo/new Nihongami as well, the largest part however is focusing on the various historical hairstyles displayed at the Kushi Matsuri.

…Kobunshi Katsura - Showa Meigiren: featuring portraits of 228 senior Geisha in the late Showa period. Some of them worked in Hanamachi that no longer exist, 31 of them are still active in 2022.

…Tetsuo Ishihara - Maiko no kamigata: showing Maiko hairstyles, how to tie them, Kanzashi calendar, Pocchiri showcase, and a Maiko getting dressed

…Tetsuo Ishihara - Kyo Shimabara Tayu: similar to Maiko no Kamigata, but focusing on Tayu hairstyles. Contains a little overview about the then-current Tayû and some of their activities around the year.

…Hiroshi Mizobuchi - Gion, the world of stylish parties: Photos by HM (mostly Gei/Maiko, but also some Hanamachi architecture and food), Maiko illustrations, old (Taisho/early Showa) photos of Gion Kobu Gei-/Maiko and interviews with selected Gei/Maiko and Karyukai workers.

…Noboru Hamaoka - Gion to Maiko: mostly b/w photos, some colour photos featuring people who live in the Karyûkai: including Gei-/Maiko, dance teachers and hairdressers, Gion’s cityscape, Kanzashi and Okiya interior. More text than photos.

…Hiroshi Mizobuchi - Kyo Miyagawacho: Photo book, bit of history, events through the year. “History of Miyagawacho” by the then head of the Ochaya Union fully translated to English, otherwise the main content is in Japanese. Miyagawacho map and Ochaya list on the last pages.

…Hiroshi Mizobuchi - Kyo Pontocho: similar to Kyo Miyagawacho, but smaller format and less text

…Hiroshi Mizobuchi - Gion Mai Goyomi: HM photos on abysmal tiny pages. Can’t recommend. Heard there are two editions of this, that differ, so maybe the other one is bigger?

Category 2: English or Japanese with full English translation in the same book.

…Liza Dalby - Geisha: LD lived in Kyoto and worked with Pontocho Geiko in the 1970′s. In this book, you can read about her experiences

…Kikuya - I, a Geisha: written by an Akasaka Geisha, has infos about her profession, some infos about the history of selected Tokyo Hanamachi.

…various - Geisha: beyond the painted smile: lots of text but only little content. Few nice photos. Only worth buying if it’s really cheap.

…John Paul Foster - Geisha and Maiko of Kyoto: portraits of and interviews with several Gei/Maiko, studded with anecdotes of JPF’s experiences as photographer in Kyoto.

…Percival Perkins - Geisha of Pontocho: Experiences with Pontocho Geiko and Maiko in the 1950’s and short biographies of selected GeiMaiko.

…Kyoko Aihara - Geisha: good and basic book from the late 1990′s focusing on Hanamachi life in Kyoto. You can spot some familiar faces of Geiko who were Maiko then, or Geiko who just retired recently.

…Mineko Iwasaki - Geisha of Gion: autobiography of one of the most famous Kyoto Geiko, including anecdotes from her elders (for example, concering life in the Hanamachi during WWII)

…John Paul Foster - now a Geisha: while “Geisha and Maiko of Kyoto” offers a rather broad spectre of topics, this is focused on the change from Maiko to Geiko: Sakko and Erikae. JPF portrays three Maiko, then Geiko during this time of transition.

…Kazuhiko Matsumura - Subtle Beauty: originally a photo essay published in a newspaper. It’s about Maiko and Geiko from the five Kyoto Hanamachi in all stages of their carreers.

…Hiroshi Mizobuchi - the Kagai in Kyoto: probably the only HM book mostly translated to English. Apart from being an updated version of books like “Kyoto Gion, Kyoto Pontocho, Kyoto Miyagawacho”, an entire chapter is dedicated to Satsukis way from Shikomi to Geiko.

…Taka Kobayashi - Utsuyaka: full-page photos of Kosen (Gion Kobu) with only little text. The book itself is a pretty large format, so you can have a good look at her outfits.

…Kelly Foreman - the Gei of Geisha: densely packed with information on around 250 pages, concerning arts, economy and the social aspects of being a Geisha.

…Sayo Masuda - Autobiography of a Geisha: SM endured a lot of abuse from childhood on, was sold to an Okiya in Kamisuwa Onsen at the age of 12 and worked as a Geisha until she was “bought” by a patron around 1939.

Category 3: originally published in Japanese, available in lots of different languages, but not English.

…Kiharu Nakamura - Memoiren einer Geisha: KH worked as Geisha in Shinbashi for around 2 years in the early 1930′s. Only around 20% of the whole book deal with her time before retirement, so the title is a bit misleading. Nevertheless, it’s a nice source of information on pre-war Shinbashi.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinuyo Tanaka and Isuzu Yamada in Flowing (Mikio Naruse, 1956)

Cast: Kinuyo Tanaka, Isuzu Yamada, Hideko Takamine, Mariko Okada, Haruko Sugimura, Sumiko Kurishima, Chieko Nakakita, Natsuko Kahara, Seiji Miyaguchi, Daisuke Kato. Screenplay: Toshiro Ide, Aya Koda, Sumie Tanaka, based on a novel by Koda. Cinematography: Masao Tamai. Production design: Satoru Chuko. Film editing: Eiji Ooi. Music: Ichiro Saito.

Having been a college English teacher and a print journalist, I know something about what it's like to be in a dying profession. So I have some empathy with the women in the geisha house in Mikio Naruse's Flowing. Their story is told largely from the point of view of Rita Yamanaka (Kinuyo Tanaka), whose name the owner of the house, Otsuta (Isuzu Yamada), finds too difficult to pronounce, so she calls her Oharu, a name that will have resonance for anyone who has seen Kenji Mizoguchi's 1952 masterpiece, The Life of Oharu. But unlike Mizoguchi's heroine, this Oharu is a simple woman in a profession that will probably never vanish: a maid. Her quiet ubiquity in the house enables her to see and hear things that heighten her mistress's financial struggles and the household's eventual doom. Equally valuable is the role of Katsuya (Hideko Takamine), Otsuta's daughter, who was trained as a geisha but doesn't want to be one. She regards her mother's profession as a commodification of self. Unfortunately, Katsuya has no marketable skills and is struggling to find her way in a male-dominated world. Naruse's film is a poignant and searching commentary not only on the disappearing way of the geisha but also on the role of women in a society trying to redefine the relationship between the sexes. Tanaka, Yamada, and Takamine are three of the greatest Japanese actors; it's a treat to see them working together, and they're beautifully supported by the rest of the cast.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'art, les femmes et un supermarché japonais

Ces dernières semaines j'ai vu (et revu pour l'un) deux films que j'ai vraiment adoré, deux films qui parlent d'agentivité, du carcan dans lequel sont coincées les femmes dans la société, de comment faire cohabiter l'art, le désir et le couple dans une société hétéropatriarcale. Et puis j'ai aussi regardé un film sur un supermarché japonais, ça n'a aucun rapport but bear with me !

Maternité éternelle, Kinuyo Tanaka (1955)

Le premier était un rattrapage puisque j'avais raté la ressortie en salles des films de la cinéaste japonaise Kinuyo Tanaka (1909-1977) dont j'avais pourtant entendu beaucoup de bien. J'ai donc commencé par Maternité éternelle (dont je préfère largement le titre anglais Forever a woman), un film de 1955 qui s'inspire de l'histoire vraie de la poétesse Fumiko Nakajō, décédée à l'âge de 31 ans d'un cancer du sein — et qui est écrit par une femme, Sumie Tanaka. Comme vous vous en doutez, c'est un film d'une tristesse infinie. Quand le film commence, Fumiko est coincée entre un mari qui ne l'aime plus, deux enfants dont elle doit s'occuper et un cercle littéraire qui critique sa poésie dans son dos parce que ses sujets ne semblent pas assez nobles. Comprendre par là que ce sont des sujets "de femme".

Elle divorce de son mari et apprend qu'elle doit lui laisser son fils, tandis qu'elle a la garde de sa fille. Ses liens amicaux / secrètement amoureux avec son mentor Takashi Hori (l'un des rares à aimer et comprendre ses poèmes) s'achèvent quand ce dernier décède (oui ce film est vraiment triste, j'ai essayé de vous prévenir). Dans la foulée, elle est diagnostiquée d'un cancer du sein et est hospitalisée. Au même moment, Fumiko apprend la publication de quelques-unes de ses œuvres dans une revue de poésie, ce qui lance sa carrière au pire moment. Évidemment, elle soupçonne son état de santé d'influencer la popularité soudaine de ses écrits.

Elle accepte après de longues tergiversations de s'entretenir avec un journaliste — bien qu'elle sait qu'il ne vient là que pour chercher le récit racoleur de ses derniers jours — et entame avec lui une relation sentimentale et sexuelle. Je précise sexuelle parce qu'il y a des scènes assez incroyables dans ce film dans lesquelles Fumiko exprime son désir sans détours alors même qu'elle souffre de regarder son propre corps suite à sa mammectomie.

Tanaka joue sans cesse avec ce regard douloureux que Fumiko pose sur elle-même. Dans une scène vraiment sublime elle tourne le dos à son amant, qui s'apprête à retourner à Tokyo, et on la voit le regarder dans un miroir. Tout ce jeu de regards dit beaucoup sur le rapport au corps et à la séduction. Maternité éternelle raconte la difficulté pour Fumiko d'être dans un même mouvement une mère, une poétesse, une amante et une femme. Combiner tous ces rôles sans en sacrifier aucun est un vrai fardeau. Et c'est très beau de la voir écrire dans sa chambre d'hôpital (simplement parce que les images de femmes qui écrivent au cinéma me paraissent trop rares), rongée par la peur de n'être aimée que pour son histoire personnelle, de ne trouver personne pour embrasser toutes les facettes de sa personnalité. J'ai fini le film en larmes mais avec aussi l'impression d'avoir vu une œuvre rare sur des sujets peu souvent traités.

Les chaussons rouges (Powell et Pressburger, 1948)

Et puis la semaine dernière j'étais à Paris et j'en ai profité pour faire un tour au Champo et revoir Les chaussons rouges (de Powell et Pressburger, 1948). J'avais déjà vu ce film il y a dix ans, et le redécouvrir m'a une nouvelle fois permis de mesurer à quel point le temps change notre perception des histoires. J'avais surtout gardé dans ma mémoire le souvenir du ballet central, qui n'est pas comme on a l'habitude de voir dans la comédie musicale un dream ballet mais plutôt un ballet cauchemardesque qui raconte l'histoire d'une femme possédée par ses chaussons de danse rouges. Une fois qu'elle les enfile, elle ne peut plus les enlever, ni s'arrêter de danser, elle est complètement manipulée. Si j'ai gardé un souvenir aussi précis de cette séquence c'est parce qu'elle est impressionnante visuellement, pleine de trouvailles, d'effets de perspective et de transparence, parce qu'elle invente de nouvelles choses à chaque seconde. Et aussi parce que, comme je l'ai dit de nombreuses fois, j'adore les films en Technicolor. Et tout le film fait tellement bien usage de la saturation des couleurs, des chaussons d'un rouge vif aux cheveux roux de l'actrice Moira Shearer.

Mais j'avais oublié que, comme Maternité éternelle, Les chaussons rouges raconte avant tout l'histoire d'une femme tiraillée entre les hommes et l'art dans un monde où l'art est contrôlé par les hommes. Elle est coincée entre celui qui l'a découverte, son "mentor" le tyrannique Lemontov, et celui dont elle est tombée amoureuse, le compositeur du ballet Julian Craster. L'un est machiavélique, l'autre se présente comme un homme bon, mais tous les deux empêchent Vicky, la danseuse, de laisser libre cours à sa créativité. L'un contrôle ses rôles, l'autre contrôle la musique sur laquelle elle danse. Tous les deux sont des marionnettistes.

Les chaussons rouges est une sorte de backstage musical, c'est à dire un film qui raconte les coulisses d'une production. Mais contrairement à ce qui est d'usage dans ce sous-genre de la comédie musicale, l'entertainement ne gagne pas à la fin. Le show ne fait pas tout oublier, il ne suffit pas à effacer les violences et les injustices. Au contraire, le divertissement et les hommes qui en tiennent les ficelles demandent un sacrifice. C'est un film très glaçant mais vraiment passionnant, que je vous conseille de rattraper si vous êtes à Paris !

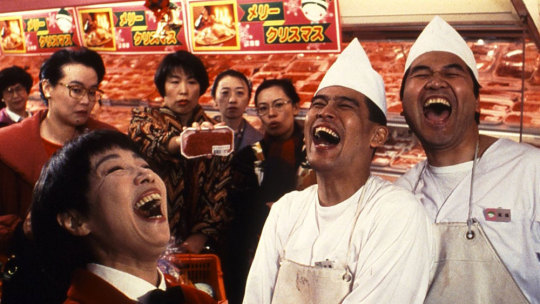

Supermarket woman, Jūzō Itami (1996)

Le dernier film n'a pas grand chose à voir mais j'avais quand même envie de l'archiver par ici. C'est un film qui parle de supermarchés, d'ambition, de capitalisme et de sororité. J'ai eu envie de regarder Supermarket woman de Jūzō Itami parce que j'avais adoré son Tampopo, un film qui donnait vraiment envie de manger des ramen. Bref, Supermarket woman met une nouvelle fois en scène l'irrésistible Nobuko Miyamoto et son énergie contagieuse dans un contexte culinaire.

Le scénario tient sur un post-it : une femme qui se pense la "ménagère" moyenne décide d'aider un ancien camarade de classe à sauver son supermarché de quartier. Ce dernier risque de couler à cause de la concurrence d'un supermarché concurrent qui casse les prix. Gros TW morceaux de viande en gros plan, poissons morts, moult fruits et légumes emballés dans du plastique (le film date de 1996). Le personnage de Nobuko Miyamoto, Hanako, infuse donc sa bonne énergie et ses bonnes idées dans ce temple capitaliste. Avec sa modestie, elle fait passer ses trouvailles pour du "bon sens" : écouter les clientes, privilégier les bons produits, s'allier avec les petites mains du supermarché et se rebeller contre la misogynie du boucher et du poissonnier qui font régner la terreur.

J'étais un peu circonspecte devant certains aspects du film — oui, ça reste la victoire d'un supermarché contre un autre, et donc du gentil-capitalisme sur un très-méchant-capitalisme plus agressif — mais je dois avouer que j'ai été happée par le ton léger et les nombreuses intrigues en coulisse. Il y a cette bizarrerie très plaisante qu'on trouvait déjà dans Tampopo. Et puis je me suis retrouvée comme bercée par le côté très familier du supermarché, ses allées, ses promos, ses néons blancs. J'aurais suivi Hanako et son sourire pendant plusieurs heures, ce qui prouve que la magie étrange de ce film opère.

Comme je n'irai jamais au Japon (même si ça a été l'un de mes rêves pendant longtemps), j'ai eu aussi l'impression de pouvoir faire ce que je préfère en voyage : zoner au supermarché et regarder les différents produits. Eh, la magie du cinéma ! Voilà si vous êtes un enfant des années 90 qui adorait aller faire les courses avec sa mère, peut-être que ce film est aussi un peu pour vous ?

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

HII KIRA KIRA looks at you :] persona names maybe... (feel free to choose from all games, but obviously 5 is the one I know :D)

yeye!! (nick)names from persona 5!!!

Aka, Akan, Akane, Aki, Akim, Akimi, Akimitsu, Akira, Al, Ali, Alice, Ang, Ango, An/Ann/Anne, Aoi, Ama, Amami, Amamiya, Ake, Akechi, Ara, Arai

Car, Caro, Carol, Caroli, Carolin/Carolyn, Caroline, Chi, Chiha, Chihay, Chihaya, Coach

Dem, Demi, Demiu, Demiur, Demiurge, Di, Dir/Dire, Director

En, Ena, Esc, Esca, Escar, Escargo/Escargot

Fu, Futa, Futaba, Fuji, Fujikawa

Go, Goro

Haru, Hi, Hif, Hifu, Hifumi, Has, Hase, Hasega, Hasegawa, Hi/Hii, Hiir, Hiira/Hira, Hiiragi, Hiraguchi, Hy, Hyo, Hyodo

Ichi, Ichiko, Ichiryu, Ichiryusa, Ichiryusai, Igo, Igor, Iss, Isshi, Isshiki, Ichino, Ichinose, Iwa, Iwai

Jo, Jose, Jun, Juny, Junya, Jyu, Jyun, Jul/Jule, Juli/Julie, Julia, Julian, Just, Justi, Justin, Justine

Kas, Kasu, Kasumi, Kaz, Kazu, Kazuya, Ko, Kob, Koba, Kobaya, Kobayaka, Kobayakawa, Koto, Kotone, Kumi, Kun, Kuni, Kunik, Kunika, Kunikaz, Kunikazu, Kuo, Kuon, Kiu, Kiuchi, Kita, Kitaga, Kitagawa, Kamo, Kamoshi, Kamoshida, Kawa, Kawakami, Konoe, Kage, Kageya, Kageyama, Kane, Kaneshi, Kaneshiro, Kat, Kata, Kataya, Katayama, Kabu, Kabura, Kaburagi

Lala

Mak, Mako, Makoto, Mari, Mariko, Masa, Masayo, Masayoshi, Mer, Mero, Merope, Mi, Mika, Miya, Miyako, Morg, Morga, Morgan, Morgana, Moto/Motoh, Motoha, Mune, Munehi, Munehis/Munehise, Munehisa, Mish, Mishi, Mishima, Maru, Maruki, Maki, Makigami, Mifu, Mifune, Mada, Madara, Madarame, Mon, Mont, Monta, Montag, Montagne

Nao, Naoya, Nat, Nats, Natsu/Natsuh, Natsuhi, Natsuhiko, Noge, Nii, Niiji, Niijima, Naka, Nakano, Nakanohara, Natsume

Od, Oda, Oku, Okumu, Okumura, Ohya, Owa, Owada

Pres, Presi, President

Ren, Ru, Rufe, Rufer, Ruferu, Rumi, Ry, Ryu, Ryuji

Sada, Sadayo, Sae, Sei, Seiji, Shadow, Shi, Shibu, Shibus, Shibusa, Shibusawa, Shiho, Shin, Shini, Shinichi, Shiny, Shinya, Shu, Shuz, Shuzo, Si, Siu, So, Soji, Sojiro, Soph, Sophi/Sophie/Sofi/Sofie, Sophia/Sofia, Sugi, Sugimura, Suguru, Sumi, Sumir, Sumire, Saku, Sakura, Su, Suz, Suzu, Suzui, Shira, Shirato, Shiratori, Saka, Sakamo, Sakamoto, Shido

Tae, Tak, Taku, Takuto, Tom, Tomoko, Tor, Tora, Torano, Toranosuke, Take, Takemi, Tan, Tana, Tanaka, Tsu, Tsuda, Taka, Takama, Takamaki, Togo

Ubu, Ubuka, Ubukata

Wakaba

Yu, Yuki/Yuuki, Yukimi, Yusu, Yusuke, Yuji/Yuuji, Yosh, Yoshi, Yoshida, Yoshiza, Yoshizawa

Zen, Zenki, Zenkichi

#names#nicknames#baby names#first names#persona 5#persona 5 characters#persona 5 names#name searching#name list#name blog#ask answered#character names#name help#name hoarder#names list#requested list#list of names#names from characters

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ProyeccionDeVida

🎬 “LA PRINCESA MONONOKE” [Mononoke-himea]

🔎 Género: Animación / Fantástico / Aventuras / Cine épico / Animales / Naturaleza

⌛️ Duración: 133 minutos

✍️ Guion: Hayao Miyazaki

🎵 Música: Joe Hisaishi

💥 Argumento: Con el fin de curar la herida que le ha causado un jabalí enloquecido, el joven Ashitaka sale en busca del dios Ciervo, pues sólo él puede liberarlo del sortilegio. A lo largo de su periplo descubre cómo los animales del bosque luchan contra hombres que están dispuestos a destruir la Naturaleza.

👥 Reparto en Voces: Ashitaka (Billy Crudup, Yōji Matsuda, Cédric Dumond), San (Yuriko Ishida), Moro (Gillian Anderson, Akihiro Miwa), Okkoto-nushi (Keith David, Hisaya Morishige), Lady Eboshi (Minnie Driver, Yūko Tanaka), Jiko-bō (Billy Bob Thornton, Kaoru Kobayashi), Gonza (Tsunehiko Kamijō), Toki (Jada Pinkett Smith, Sumi Shimamoto), Kaya (Yuriko Ishida), Kouroku (Masahiko Nishimura) y Nago (Makoto Satō)

📢 Dirección: Hayao Miyazaki

© Productoras: Studio Ghibli, Dentsu Inc, Nibariki, Nippon TV, TNDG & Tokuma Shoten

🌎 País: Japón

📅 Año: 1997

📽 PROYECCIÓN:

📆 Viernes 28 de Junio

🕗 8:00pm.

🎦 Cine Caleta (calle Aurelio de Souza 225 - Barranco)

🚶♀️🚶♂️ Ingreso libre

🙂 A tener en cuenta: Prohibido el ingreso de bebidas y comidas. 🌳💚🌻🌛

0 notes

Text

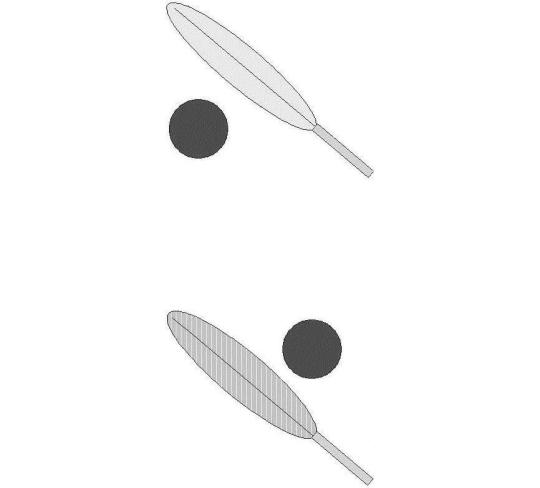

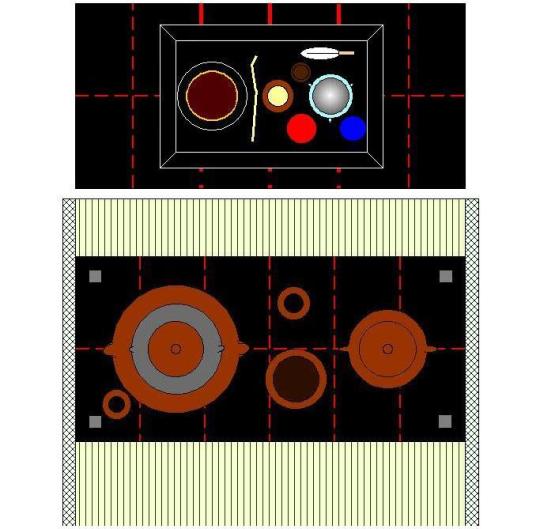

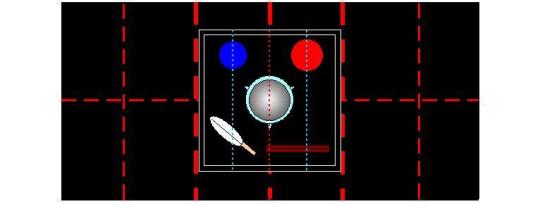

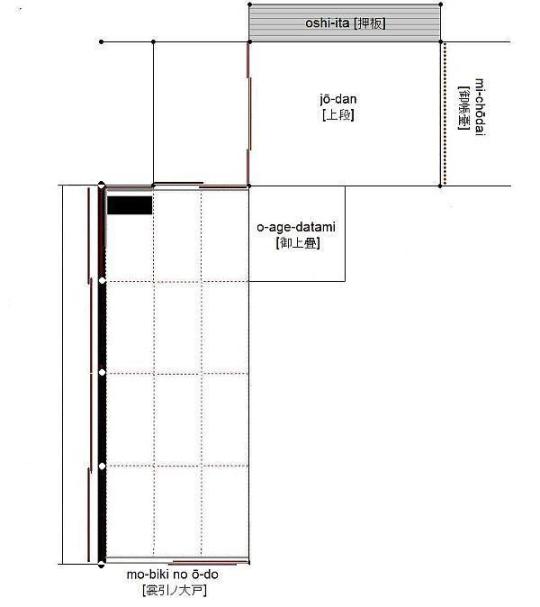

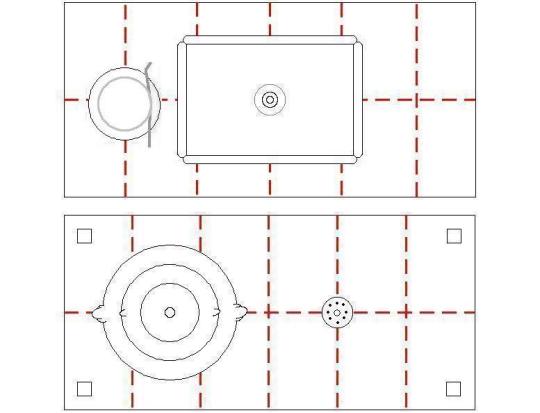

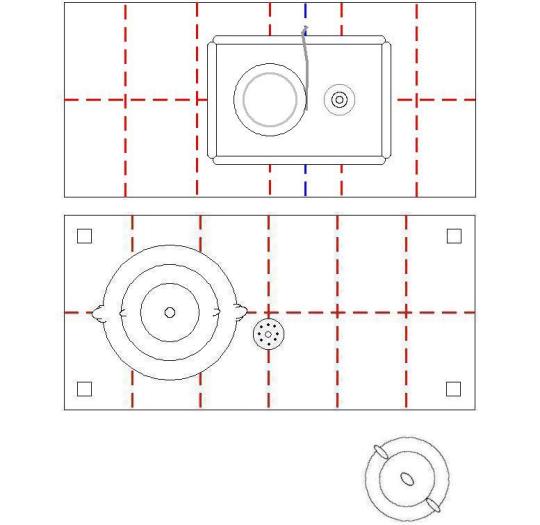

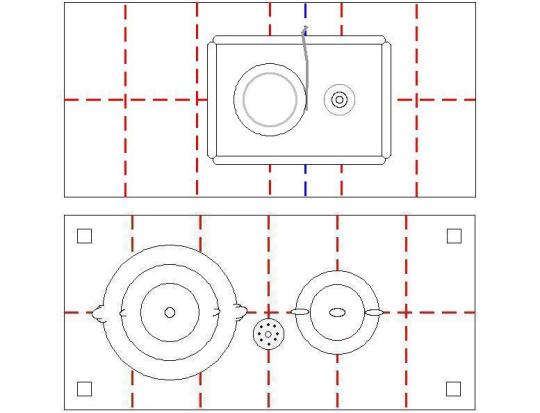

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (59f): Soe-oki [添え置], and Its Impact on Kane-wari (Tanaka Senshō’s Genpon [原本] Version of the Text).

The genpon [原本] edition of the Nampō Roku contains a text for entry 59 that is almost identical to the material translated in the previous post¹. However, rather than stopping there (or continuing on to a kaki-ire, like Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon text), that passage is followed by four drawings, and a short concluding section that discusses the drawings in relation to the idea of soe-oki [添え置き] (below)².

Just like this, the habōki and futaoki are, in the same way [as when the plectrum’s box was added to the biwa, and a drinking cup added to the tō-bin], added to the kōgō’s kane, [and] to the futaoki’s kane -- and so they are tied together [with the kōgō and futaoki] into a single unit³.

On the daisu, [in the case of] midare[-kazari] with the nagabon, among the various incense utensils the ko-habōki [小羽箒] and kō-bashi [香箸], when placed out -- whether they cross successive [kane], or whether they are [arranged] to accompany [something else] -- [the host] is free to count [them] as he likes⁴.

With respect to the maru-bon taikai, if the habōki is placed in front [of the taikai] oriented side-to-side, of if it is placed diagonally, the count is one⁵.

All of these are examples of the principal on which soe-oki is based⁶.

_________________________

◎ The first part of this entry is almost identical to what was published in the previous post, though it also adds the four sketches and an explanation at the end (this new material is what was translated above).

But what is more important (since variations of this text have already been considered several times), is Tanaka Senshō’s commentary.

He divides the entry into two sections, and with respect to the content of the first part, he defers to Shibayama Fugen’s analysis (occasionally quoting Shibayama in his own interpretations of the different phrases that he considered difficult to apprehend)*.

As a commentary on the passage that I have rendered above, however, Tanaka embarks on his own exposition of the ideas that are central to an understanding of the concept of soe-oki. I will translate those remarks in full:

“As you can see in the drawings, the habōki and kōgō, the hishaku and the futaoki are counted as one when placed in a straight line†. This is why it is called ‘the kane of the kōgō,’ and ‘the kane of the futaoki‘ in the text. In other words, the count becomes one when the two utensils are connected [to the same kane]. Having these numbers conform with the chō [調] or han [半] of the za‡ is an important part of chanoyu, and must be looked at carefully.

“Here we were given the examples of hishaku and futaoki, and the habōki and kōgō. But in the case of other sorts of utensils, if those two objects rest on the same line, to say they will also be counted as one is not necessarily the case. For example [on the daisu or naga-ita], the kensui [= koboshi] and futaoki** are in front of the shaku-tate. But when it comes to the daisu and naga-ita, rather than saying that they count as one, they actually number two [units]. [When we want to talk about the concept of soe-oki,] in the first place it is said that [the objects] must be in close proximity††; and besides that, there is the question of how this relates to tai [躰] and yō [用], with respect to the individual components of a set‡‡. Ichi-gu [一具] means that unless the two tools are related to each other, they should be [counted] separately. It is like unrelated people sharing the same house: irrespective of the fact that they rest on the same line, they will not be counted as one [unit] -- according to this way of thinking.

“This issue is addressed in the genpon:

“‘If a large fude-kake is placed on the far side of the suzuri, if it continues on from that kane, there will be no problem if it contacts the [endmost] yin. However, this is because the fude and sumi are part of the suzuri’s set [of writing implements].

“‘That being said, with respect to the arrangement on top of the daisu, the chaire, the chawan, the hishaku, and the habōki, because these things are all independent utensils, so they will never be associated with successive kane.

“‘But [here,] if the suzuri is removed, the fude will be useless; the sumi will be useless. Because all of these things are part of the suzuri’s set, it can never be excluded.

“‘This is of the same category [of arrangements] as when a box for the plectrum is [displayed together] with a biwa [琵琶] on the chigai-dana. Or when things like a drinking cup [is arranged] with a tōbin [湯甁]. In every case, these are things that are placed out to accompany [the other].

“‘Naturally, there is no case where [the accompanying object] is neither yin nor yang: they should never be placed in the space in between <15>, since they will then be disassociated from the kane***.’ And so forth.

“And then...in the above passage†††, the kōgō and habōki, the futaoki and hishaku, because these are examples of things that may be considered ichi-gu [一具], they are suitably [displayed] as soe-oki. Since they are resting on the same straight line, and are tied together by their placement, they are counted together [as one unit]. But if one of the utensils is placed in between the kane, it is natural that they will not be counted -- and the reason why should be obvious‡‡‡. According to this principal, with respect to the daisu temae, when [the utensils] are arranged on that shaku-nagabon (or maybe it is something like the large maru-bon), when the habōki or kō-bashi occupy successive kane, or when they cross a yin and yang [kane] so as to eradicate the yin****, doing different things like this is simply a way to bring the count into conformity with the desired chō [調] or han [半] value [required by the za], so this [count] can be achieved effortlessly.

“When the habōki is placed [horizontally] -- like the character “一” -- in front of the taikai, or when it is oriented on a diagonal [as when arranged with a kōgō], the count is one. These are examples of soe-oki. [Arranging things] like this is the very meaning of soe-oki, and this is the idea that is being discussed in the text††††.”

___________

*In his explanation of the passage, Tanaka also includes relevant sentences and phrases from entry 48 in the Sumibiki no uchinuki-gaki・tsuika [墨引之内拔書・追加], along with Shibayama’s insights into their significance to the present discussion.

†Itchoku-sen ue ni [一直線上に] means “arranged on top of a straight line” -- arranged in a straight line (which conforms with one of the kane).

Because this is a reference to the yang-kane that is contacted by both of the objects, the two utensils do not always appear to be one in front of the other: all that is required is that they both contact the yang-kane at some point along their lengths.

In this passage, Tanaka uses itchoku-sen (and its variants) to mean the kane.

‡According to Rikyū's poem

toko ha toko, zaseki ha zaseki, tana ha tana

ni chō ichi han ni han ichi chō

[床ハ床、座席ハ座席、棚ハ棚

二調一半二半一調]

“The toko is the toko, the room is the room, the tana is the tana: two [are] even, one [is] odd; two [are] odd, one [is] even.”

the kane-wari count for each of the za is based on a combination of the values for the three areas where objects are displayed: the tokonoma, the tana, and the utensil mat in front of the tana (= “the room”).

Furthermore, the two za must have different values: one za should be chō [調] (in other words, the grand total should be even), and the other han [半] (the total should be odd).

Originally, Rikyū connected these values for the za to the condition of the fire and hot water: at the beginning of the shoza they were both weak (which is yin, chō), and increased over the course of the za, thus the shoza was considered to be chō; at the beginning of the the goza, the fire and hot water are both strong (which is yang, han), though they decline over the course of the za, thus the goza was judged han.

During the daytime, the shoza is chō, and the goza is han; but after dark the shoza is han, and the goza is chō.

There, however, were special occasions (both happy and sad) that would impact on the way the za were ordered (the reasons for all of these are discussed elsewhere).

**Tanaka is thinking about the futaoki being placed inside the kensui (= koboshi), in the modern fashion.

††Traditionally no more than 2-sun should separate the two -- which is exceeded, on the daisu, by the distance between the koboshi and the shaku-tate.

‡‡Tai [躰] and yō [用] refer to the yang and yin kane, respectively; and ichi-gu [一具] means a set of logically connected objects -- such as the components of a writing set.

Here, however, it appears that Tanaka is using tai [躰] to refer to the hon-tai [本躰] -- the principal object (such as the futaoki or kōgō); and yō [用] to mean the soe-mono [添え物], the object that is added to the hon-tai (so, in these examples, the hishaku and habōki, respectively). This way of using these terms has not been indicated (in any of the commentaries) heretofore.

The shaku-tate and koboshi/futaoki in Tanaka’s example share no connection (since they are all independent objects, each used for its own unrelated purpose during the service of tea), so they are not part of an ichi-gu.

***The complete Japanese text of this quoted passage is as follows.

Dai-naru fude-kake, suzuri no mukō yori kakari-okeba, tsuzuki-mono ni te suzuri no kane ni shitagau-yue, in ni atarite mo kurushikarazu. Tadashi kore ha suzuri no ichi-gu no fude・sumi yue no koto nari, sate-koso daisu no ue no kazari ha, chaire mo, chawan mo, hishaku mo, habōki mo, hito-yaku hito-yaku no dōgu naru-yue, tonari no kane ni shitagau-koto nashi. Suzuri wo hanachi fude no yō nashi, sumi no yō nashi. Mina suzuri no ichi-gu ni shite, hanarezaru-yue nari. Chigae-dana no biwa ni bachi-bako no rui nari. Tō-bin ni hai-tō, izuremo soe-mono nari. Mochiron, in ni mo yō ni mo arazu, ma [h]e ha oku-bekarazu. Sore ha ka no hazushitaru kane nari.

[大なる筆架、硯の向よりかゝり置けば、ツヾキものにて硯のカネに従ふ故、陰に当りても不苦。 但是は硯の一具の筆・墨故の事也、扨こそ臺子の上の飾は、茶入も、茶碗も、柄杓も、羽箒も、一役々々の道具なる故、隣のカネに従ふ事なし。 硯を放ち筆の用なし、墨用なし。 皆硯の一具にして、離れざる故也。 違棚の琵琶に撥筥の類也。 湯甁に盃等、何れも添物也。 勿論、陰にも陽にもあらず、間へは置く可からず。 夫は彼の外づしたるカネ也。]

†††The text of the entry, not the passage quoted earlier in these comments.

‡‡‡In other words -- in case it is not obvious to the reader -- the habōki or hishaku can be considered synonymous with the ken-byō, or an elongated fude-kake, in that it will join neighboring kane together into a single unit, as has been explained in the various texts. But if the kōgō or futaoki is not placed on a kane, the connection between kane established by their having been crossed by the habōki or hishaku will be lost -- it is like an electrical current, which will flow along several separate wires so long as something connects them to the source of the current; but the current does not flow in the space in between the wires. This seems to be the point of this explanation.

****Tanaka uses the verb keshitari [消したり], which means to deaden, blunt, dampen, extinguish; in other words, the intention is to convert the yin into yang, to change the yin-kane into an extension of the yang-kane to which the ko-hane or kyōji joins it.

††††The text of Tanaka’s comments:

この図の通り、羽箒と香合、柄杓と蓋置の二品を、一直線上に置く時は、数を一箇として数える。これを本文の香合のカネ、蓋置のカネeにたよりて置きたる結びカネと云う。即ち結びて数が一つになる。この数の調半を合わすことは、茶の湯にては大切のことであるから、よく吟味せぬばならぬ。

ここには、ただ柄杓、蓋置、羽箒、香合の一例が出て居るが、然らば、他の何品でも、一直線上に二品あれば皆数一つかと云うに、決して然らず。例えば、柄杓立の前に建水や蓋置がある。台子、長板の時でも、数一つかと云うに、これは数二つである。第一、接近して添えると云うことと、その外に、体用の関係として一具でなければならぬ。一具とは、二品親類筋の道具でなくては、全くの他人の同居では、如何に一直線上にありても、数は一つにならぬ道理がある。

このことは原本にある通り。即ち、「大なる筆架、硯の向うより掛り置けば、続きものにて硯のカネに従ふゆえ、陰に当りても苦しからず。但これは硯の一具の筆・墨ゆえのことなり。扨こそ台子の上の飾は、茶入も、茶碗も、柄杓も、羽箒も、一役一役の道具なるゆえ、隣のカネに従うことなし。硯を放ち筆の用なし、墨用なし。皆硯の一具にして、離れざるゆえなり。違棚の琵琶に撥箱の類なり。湯瓶に盃など、何れも添え物なり。勿論、陰にも陽にもあらず、間へは置くべからず。それは彼の外づしたるカネなり。」云々。

と。右の文章で、香合と羽箒、蓋置と柄杓が、何れも一具の品たるゆえに添え置きに適当なることと、一直筋上に結びて置かれたるゆえ数に入り、間のカネに置けば、勿論、外れて数に入らぬ道理が判明するであらう。この道理に依って、台子の手前にも、彼の尺長盆、或は大丸盆などの飾に、羽箒や香箸で続けたり、或は陽と陽にて潜りて陰消したり、種々の働きをして居るのは、これ皆調半の数を自由にするためである。

大海茶入の前に羽箒を一文字や、筋違に置く時は、数が一つになる。これは添え置きの一例である。斯の如きことが添え置きの根本であると云う本文の意味であるが、尚、この添え置きについての一具で無いかと云うことの説明及び議論は「追加」の巻の硯屏の条で再び説くこととする。

¹The first sentence in this version, however, reads: roku-shaku san-sun no chigae-dana, mata tsukue-toko no kazari, go-yō no kane ni kazareba ma-dōi ni shite, suzuri wo kane ni atsure-domo fude-kake, fude, sumi kazari-gatashi [六尺三寸ノ違棚、又机床ノカザリ、五陽ノカネニカザレバ間遠いニシテ、硯ヲカネニアツレドモ<、>筆架、筆墨カザリガタシ].

Which means “if a six-shaku chigae-dana, or the display [installed] on a tsukue-toko [of the same size], is arranged according to the five yang-kane [only], [everything] will be too far apart. If the suzuri contacts [its] kane, it will be difficult to display the fude-kake, fude, and sumi.”

As can be seen, the words ma-dōi ni shite [間遠いニシテ] are not found in Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon version of the same text. Otherwise, the two versions are identical (aside from the use of more modern-style punctuation in Tanaka’s version).

²The four drawings, and the block of text that follows, are all based on things found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript (rather than sourced from the toku-shu shahon) -- implying that the editors of the “genpon” edition were not averse to borrowing from the earlier published editions of the Nampō Roku (albeit without ever citing that source) when that information was useful to their purposes.

³Kaku-no-gotoki kōgō no kane, futaoki no kane nita-yorite soetaru habōki, hishaku naru-yue, musubite-kazu hitotsu ni naru nari [如此香合ノカネ、蓋置ノカネニタヨリテ添タル羽箒、柄杓ナル故、ムスビテ數一ツニナル也].

Kōgō no kane, futaoki no kane [香合のカネ、蓋置のカネ] means that it is the kōgō, and the futaoki, that are associated with the kane. In other words, these two utensils are the principals, the hon-tai [本躰], in their respective cases.

Nita-yorite [似た 依りて ] means that the two (the kōgō and habōki, and the futaoki and hishaku) represent parallel cases.

Soetaru habōki, hishaku [添えたる羽箒、柄杓] means that it is the haboki and hishaku that are added to the other utensils -- that they are, in other words, the soe-mono [添え物].

Naru-yue, musubite-kazu hitotsu ni naru [成るゆえ、結びて數一つになる] means “for that reason (because the habōki and hishaku are added to the others), they are tied together into a single unit.”

In other words, the kōgō + habōki, and futaoki + hishaku, both are counted together as a single unit (for the purposes of kane-wari).

⁴Daisu, nagabon no midare ni, kō-gu shina-jina no uchi, ko-habōki, kō-bashi nado soe-oki ni shite arui ha kuguri, arui ha soete kazu wo jiyū-suru nari [臺子、長盆ノ亂レニ、香具品々ノ内、小羽箒、香箸ナド添置ニシテ或ハクヽリ、或ハソヘテ數ヲ自由スル也].

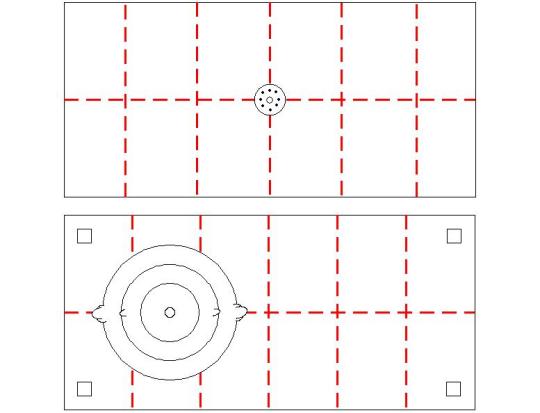

Nagabon no midare [長盆の亂れ] refers to the class of arrangements (generically known as midare-kazari [亂れ飾]) where both tea utensils and incense arrangements are mixed together on the same tray. While here a nagabon is specified (such as the shaku-nagabon [尺長盆] shown below), round trays (such as the naka maru-bon [中丸盆] and dai maru-bon [大丸盆]) were also used for midare-kazari.

A number of different examples of midare-kazari are introduced in Book Five (as well as elsewhere); many of these arrangements were created by Shino Sō-on [志野宗温; 1477 ~ 1557]*.

By the end of the eighteenth century (when the genpon text was created), “midare” (rather than midare-kazari), as a term describing various arrangements where the utensils were distributed in unexpected ways across the surface of a tray, had become rather fashionable among the followers of the Sen family schools (meaning that this usage also helps us to pinpoint the date when this text was compiled).

Ko-habōki, kō-bashi nado soe-oki ni shite [小羽箒、香箸など添え置きにして]: the ko-habōki [小羽箒], which was also referred to as the ko-hane [小羽], was a miniature habōki used to clean the rim of the incense burner after arranging the ashes; and kō-bashi [香箸] is the name primarily used in chanoyu (increasingly, as the Edo period progressed, when the original terminology was being suppressed) for the kyōji [香筋], the special chopsticks‡ used to handle the pieces of incense wood. These objects were often included in the midare-kazari (though they would not have to be). Therefore, they were considered soe-mono.

Arui ha kuguri, arui ha soete [或は潜り或は添えて] is referring to the two possible orientations of elongated objects such as the ko-hane and kyōji.

In the above sketch, the chashaku and the ko-hane are soe-mono of this sort. The orientation of the ko-hane illustrates what is meant by kuguri**, while that of the chashaku illustrates objects arranged on successive kane (which this sentence confusingly calls soete [添えて], soete means “added to,” “accompanying,” or “ancillary to”)††.

___________

*It was Shino Sō-on’s version of the kō-kai that Jōō used as the basis for his own gatherings (in consequence of which Sō-on is commonly regarded to have been Jōō’s teacher); and it was from those incense gatherings (at which tea was also served) that his chakai eventually evolved.

†This was done deliberately -- as the word “suppressed” was intended to convey -- to keep the different arts “pure.”

Where there was this kind of overlap between two of them, the terminology was usually changed in the art in which the other was only occasionally seen, to keep it separate from the original form of the practice.

‡They are generally made of ebony today, though in earlier times ivory was also a popular choice.

**Kuguru [潜る] means to pass or extend across. This is the case where something like a habōki is oriented horizontally, so that it contacts both a yin and a yang kane. It joins the two together (so that the objects arranged on them are counted as a single unit), while also “converting” the yin-kane into yang.

††Tsuzuku [続く] means to follow in sequence. That is, objects are arranged on successive kane.

Shibayama’s “special continuance” refers to the case where objects are arranged on successive kane, but because an elongated object links the yang-kane to the yin-kane that adjoins it, the yin-kane is changed into yang, and so viewed as a continuance or extension of the yang-kane (as if the objects arranged on it were arranged on the yang-kane itself).

Because the idea of kuguri-kane is essential to this idea, the two are easily confused.

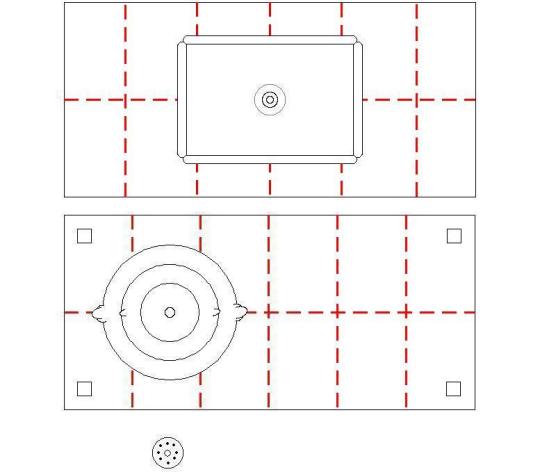

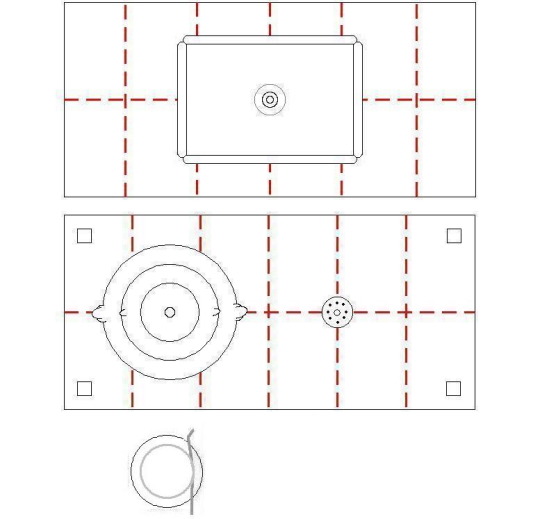

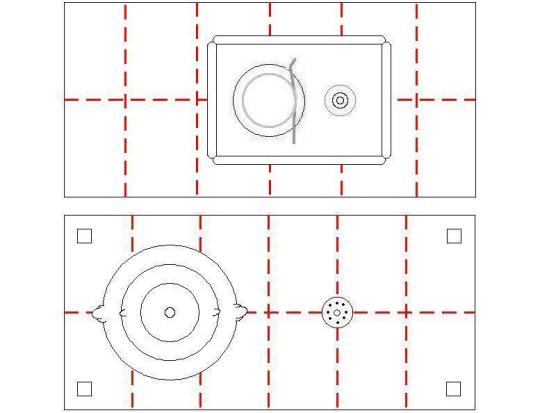

⁵Maru-bon taikai ni, takai no mae ni habōki wo yoko-sama, mata ha sujikai ni okaba, kazu hitotsu ni naru [丸盆大海ニ、大海ノ前ニ羽箒ヲ横サマ、又ハ筋違ニ置ハ、數一ツニナル].

Taikai no mae ni haboki wo yoko-sama [大海の前に羽箒を横さま] describes what is shown below.

The habōki is placed side-to-side (horizontally) in front of the taikai. On account of the prohibition that Shibayama raised in his commentary*, there is some question whether there would be issues if the habōki came into contact with the yin-kane (the habōki should be centered on the tray in front of the taikai, meaning if it contacted one yin-kane, it would contact both).

Mata ha sujikai ni okaba [又は筋違に置かば] means or else if (the habōki) is oriented on a diagonal....

This arrangement is not mentioned in the Nampō Roku, at least with respect to the maru-bon taikai†. However, two of the midare-kazari arrangements in Book Five do show the habōki oriented in that way:

The first is described as tsune no nagabon cha・kō kazari, tadashi temmoku betsu no dai nari [常長盆茶・香飾、但天目別臺也], which means the arrangement of both incense and tea utensils on an ordinary nagabon (however the temmoku is arranged on a non-meibutsu temmoku-dai)‡:

In this case, the idea seems to be to tie the kōro together with the jū-kōgō [重香合] through the habōki. This is appropriate because all three objects are members of the same set (ichi-gu [一具]).

And in the second, a meibutsu kōro (together with some of the other incense utensils) is arranged on the naka hō-bon [中方盆]

Here, the kōro is tied together with the kōgō by means of the kyōji (kō-bashi), while the habōki and taki-gara-ire are a separate unit. The logic behind the two groupings should be apparent with a little thought.

Both of these arrangements were connected with the machi-shū practitioners of both incense and tea (rather than the orthodox tradition that stretched back to Nōami and Yoshimasa), and so likely derived from the teachings of Shino Sōshin.

Kazu hitotsu naru [數一つになる]: the meaning is that, when the habōki is oriented horizontally or diagonally, it gathers any associated utensils into a single unit.

___________

*Shibayama raises that objection in the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 7 (59c): Shibayama Fugen’s Complete Commentary on Entry 48 from the Sumibiki no uchinuki-gaki・tsuika [墨引之内拔書・追加] (Part 1).

The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/717873369459130368/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-59c-shibayama-fugens

Shibayama’s argument (he was repeating things that were explained to him by the Enkaku-ji scholar who presented to him the copy of the toku-shu shahon) is that when an object crosses two yin-kane (with a yang-kane in between), the two yin-kane will “dilute” the yang-nature of the yang-kane.

This seems to conflict with Rikyū’s understanding of the matter, as envisioned in the classical arrangements for the daisu. (This, of course, would not be the first instance where the machi-shū teachings contradicted the classical teachings.)

†The only other orientation of the habōki that is mentioned in the Nampō Roku is when the habōki is placed to one side of the taikai, as shown below.

Here the habōki is not counted together with the taikai (since they are associated with different kane).

Given the nature of this arrangement, I cannot understand why the need to orient the habōki on a diagonal would ever arise.

‡Cf. the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 5 (46): an Arrangement of Tea and Incense on the Ordinary Nagabon; However, the Temmoku is [Displayed] on a Non-meibutsu Dai. The URL for this post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/630356623295234048/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-46-an-arrangement-of-tea

The face of the tsune no nagabon [常の長盆], “ordinary” nagabon, measured 1-shaku 3-sun by 8-sun 2-bu, and 1-shaku 5-sun 2-bu by 1-shaku 4-bu when measured across the rims.

**See the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 5 (48): the Display of a Meibutsu Kōro, the URL for which is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/630990876073721856/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-48-the-display-of-a

⁶Mina kore soe-oki no konpon nari [皆これ添え置きの根本なり].

Mina kore [皆これ] means “all of these examples....”

Soe-oki no konpon nari [添え置きの根本なり] means “(these examples illustrate) the fundamental idea of soe-oki.”

==============================================

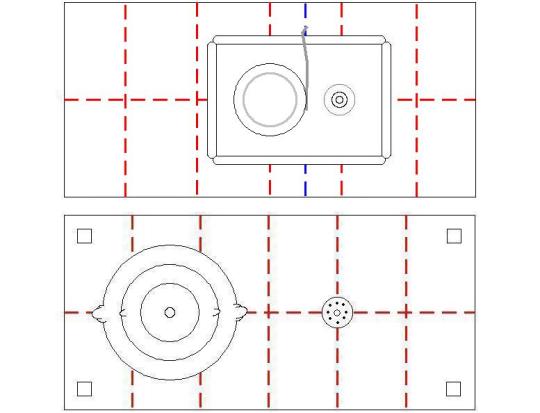

❖ Appendix: How the Daisu was Arranged by Akamatsu Sadamura.

The several descriptions of the steps of the process of arranging the utensils on the daisu for the san-shu gokushin-temae [三種極眞手前] that are found in Book Five, Book Six, and Book Seven are not entirely clear, in so far as the actual timeline is concerned, with several of the commentators suggesting that some of these things were done during the shoza, and others during the goza. However, the dichotomy of shoza and goza did not exist at that time -- indeed, the whole concept of the chakai did not appear until the 1530s, when Jōō undertook to modify Shino Sō-on’s kō-kai [香會] into a gathering that became more and more focused on chanoyu (excluding everything but the building of the fire, the service of a simple meal and kashi, and finally the preparation of koicha followed by usucha).

The basic story is that on a certain occasion when the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshinori [足利義教; 1394 ~ 1441] became seriously indisposed (to the point where the court began to fear for his life), the Emperor sent him a gift of matcha, tied in a nasu-chaire (the Kamakura-nasu [鎌倉茄子]), along with a yōhen-temmoku chawan [窯變天目茶碗] (called the Kazan-temmoku [花山天目]), and a lidded celadon jar with a design of clouds and snake-like dragons in bas relief on the front and back, as well as inside (the seiji unryū-mizusashi [青磁雲龍水指]). Apparently the Emperor’s idea was that the matcha might help to cure Yoshinori’s illness⁷. We are told that the temae was performed by Akamatsu Sadamura [赤松貞村; 1393 ~ 1447?], who was a comely youth of 17 or 18 years, and, on account of his intimate relationship with the shōgun (they were lovers), Sadamura undertook to modify the arrangement of the daisu after Yoshinori had finished his inspection of the display, to reflect that relationship.

A casual review of the dates, however, indicates that at least something must be wrong with this story -- because Yoshinori was shōgun from 1429 to 1441, while Sadamura would have been “17 or 18” years old circa 1412⁸. Furthermore, the various steps that are described in the Nampō Roku seem to be closer to the procedures employed during the sixteenth century, than at the beginning of the fifteenth.

Such considerations aside, the service of tea to which this episode refers took place not while Yoshinori was sick, but after he had convalesced -- during a banquet that the household staged to celebrate his return to health. And the tea was prepared at a daisu that had been erected in the 12-mat anteroom (hisashi [庇]⁹) that adjoined Yoshinori’s shoin (the way the mats are oriented is based on contemporaneous documents).

In that period, there was no such thing as a sumi-temae, as has been mentioned previously. The furo was brought out from the preparation area with the charcoal fire already burning; and a kama that had been boiled in the mizuya was brought out and rested on the furo. This was probably done during a brief interval while the zen [膳] (individual meal tables) were being cleared away after the banquet -- since it was customary for tea to be served after that time.

The exits and entrances were made through the mo-biki no ō-do [裳引の大戸], which is indicated in the above sketch. When the shōgun was present on his o-age-datami, these comings and goings would have been preceded, and followed, by elaborate bows.

After the furo and kama had been arranged on the daisu, the hoya was brought out and placed on the ten-ita.

Then the Gassan-nagabon, with the chaire resting on it, was brought out and placed on the mat in front of the daisu, as shown below.

Then the hoya was moved onto the mat in front of the furo.

After first cleaning the ten-ita with the habōki¹⁰, the nagabon was lifted up to the ten-ita...

...and finally, after wiping the ji-ita with the towel (that was kept in the futokoro of his kimono), the hoya was also cleaned with the towel, and then moved onto the ji-ita, so that it rested on the tattoi-no-kane [貴のカネ]¹¹.

Next, the dai-temmoku, with the chashaku resting across its hane, was brought out and rested on the mat in front of the furo.

The dai-temmoku was then lifted up onto the ten-ita, and stood to the left of the tray, as shown.

Then the chaire was moved toward the right...

...and the dai-temmoku was lifted onto the tray.

And then the tray was moved toward the right, so that the dai-temmoku was now in the very center of the ten-ita.

Next, the chashaku was lowered to the tray (and arranged so that it rested squarely on the yin-kane, as shown), completing the first stage of the kazari.

Then Sadamura brought out the seiji unryū-mizusashi, and placed it on the mat temporarily in front of the daisu.

Next, the hoya was moved to the central kane, next to the furo.

Then the seiji unryū-mizusashi was lifted onto the ji-ita, and positioned so that it rested squarely on the tattoi-no-kane.

Sadamura then brought out a lacquered mizu-tsugi¹², and added water to the mizusashi. After wiping the mizusashi, ji-ita, and hoya with his towel, the hoya was again placed on the central kane, but this time 2-sun back from the front edge of the ji-ita.

Then, after returning the mizu-tsugi to the preparation area, he brought out the hishaku and arranged it on the ten-ita -- so that it was situated to the right of the leftmost kane (in between that and the neighboring yin-kane -- so the hishaku was not associated with any kane)¹³.

This completed the second stage of the kazari, and it was at this point that the shōgun Yoshinori came forward to inspect the arrangement of the daisu.

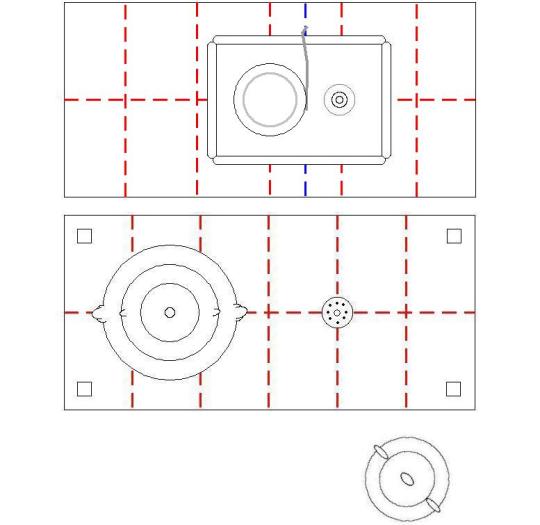

After the shōgun had taken his seat on his o-age-datami [御上疊], the temporary seat of estate (an elevated two-mat platform located across the room from the daisu), Sadamura approached the daisu.

First he reached up and moved the chashaku slightly toward the left, displacing it from its kane¹⁴.

And then, to compensate for dissociating the chashaku from its kane, he lifted the hishaku onto the endmost yin-kane, thereby restoring the balance that had been disrupted when he moved the chashaku.

After bringing out the kae-chawan and koboshi from the preparation area, Sadamura would have begun the actual preparation and service of tea.

The arrangement of the utensils during the temae would have been as follows:

__________________________

⁷In which case Yoshinori would be moved to send the Imperial Court a generous thank-gift (of money).

⁸Yoshinori was approximately 1 year younger than Sadamura, so while there may well have been a physical attraction between the two, this could hardly be considered a typical case of shudō [衆道], where the active partner was usually a fully mature man, while the passive partner was in his early teens. Furthermore, homosexual relationships between more or less equals (as would have been the case here) was, at the very least, frowned upon.

⁹The hisashi [庇] is a room erected under the eves of a building, which leads from the carriage entrance (mo-biki no ō-do [裳引の大戸] -- the name of this doorway refers to the fact that a person would have to adjust their garments in the proximity of this door after alighting from an ox-drawn carriage or palanquin) to the inner suite of private rooms, along the side of the hall (which was usually divided into three stepped rooms named according to their relative proximity to the nobleman’s jō-dan [上段]).

¹⁰According to some accounts, the habōki was placed on the ten-ita, in the spot that would later be occupied by the hishaku.

According to other sources, however, the habōki was placed on the go-sun-ita (that was located between the mats and the sill for the shōji that formed the wall on that side of the room.

Afterward, the habōki was either placed on the go-sun-ita, or taken back to the preparation area the next time Sadamura returned there.

¹¹The tattoi-no-kane [貴のカネ] is the name of the kane to the left and to the right of the central kane in the five-kane system. Tattoi [貴い] means noble, august, revered -- and it is on this kane that treasured utensils were preferentially arranged.

¹²When the seiji unryū-mizusashi was carried into the room, it had been filled to approximately 70% of its volume. After it was lifted onto the ji-ita of the daisu, Sadamura would have returned to the preparation area and brought out a mizu-tsugi, from which he would have added water to the mizusashi until it was 90% full.

¹³As mentioned above, in this period there was no such thing as a sumi-temae. Because the furo and kama had been arranged on the daisu from the beginning, the ten-ita above the furo would have become warm. Since the heat could cause the hishaku to dry out (so it might leak), the hishaku was not brought out until the last possible moment -- immediately before the shōgun would approach to inspect the daisu.

¹⁴This technically was not a part of the actual gokushin-temae (even though at least some of the machi-shū assumed it to be). Rather, it was done only because the chashaku had been carved by the shōgun, and because the tea that Sadamura was going prepare would be served to the shōgun*.

If the chashaku was left on its kane, then the hishaku would not be moved either.

If these things were not done, then after the host had brought out the kae-chawan and koboshi, the dai-temmoku would be lifted off of the tray, and stood on the ten-ita to its left. Then the chashaku would be picked up and moved to the rim of the kae-chawan. After which the dai-temmoku would be lowered to the mat (in front of the furo), and so on and so forth.

___________

*When performed strictly, the gokushin-temae produces only one bowl of koicha, which was technically supposed to be offered to the Buddha; but which, in practice, was offered to the “guest of honor” -- who, on this occasion, was naturally the shōgun (since the banquet had been organized to celebrate his recovery from his illness).

0 notes

Note

🍙🌸👔 for the ask game!!!

Thank you for the ask!

🍙 - Who's your favorite supporting character?

It's a tie between Tanaka and Manami for me. Both of them are amazing and sweet <3

🌸 - Which character grew on you the most?

Sumi, because from the beginning he seemed like he was up to something when he became friends with Misaki. However, it does seem like he values their friendship.

👔 - Whose wardrobe would you raid?

I love cute and girly clothes, so An's wardrobe would be perfect for me. She's very stylish.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Girls of the Dark (Onna bakari no yoru), Kinuyo Tanaka (1961)

#Kinuyo Tanaka#Sumie Tanaka#Hisako Hara#Akemi Kita#Chieko Seki#Masumi Harukawa#Sadako Sawamura#Chikage Awashima#Fumiko Okamura#Chieko Nakakita#Yôsuke Natsuki#Asakazu Nakai#Hikaru Hayashi#1961#woman director

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

˗ˏˋ ꒰ rules ꒱ ˎˊ˗

. . . no : ✧࿐

cheating / infidelity / pregnancy / specific illnesses + conditions (not very comfy writing for these ^^; / comfort is ok but i just won't write explicitly for the above)

nsfw / dc !! (no yandere, pedophilia, incest, abuse, etc)

i do not normally take requests, except for events! otherwise, only suggestions or my own ideas. i also do not usually do matchups, except for events or small games.

character x oc, character x character.

. . . yes : ✧࿐

sfw !! fluff, angst, comfort, etc ... <3

character x reader, romantic / platonic / familial (only platonic / familial for those that are kids or look like kids)

gender neutral !! regardless of your gender, you are free to read any of my works (save for those specifically for transgender writings)

i'm fine writing for some specifics, mostly with things like gender/sexuality or details like height/wearing glasses/having a sibling/etc.

. . . note : ✧࿐

i am only human. i have a life & an irregular sched - i might take a while w stuff depending on my motivation / workload. be patient & kind. don't be mean.

. . . fandoms / characters : ✧࿐

HAIKYUU. sugawara nishinoya tanaka kageyama hinata tsukishima yamaguchi kuroo kenma lev oikawa iwaizumi bokuto akaashi atsumu osamu suna — ( only until the anime, but vague post-timeskip is ok )

JUJUTSU KAISEN. satoru gojo yuji itadori megumi fushiguro nobara kugisaki toge inumaki kento nanami suguru geto (hs only) — ( only until manga : gojo's past arc )

KIMETSU NO YAIBA. tanjiro zenitsu inosuke kyojuro rengoku giyu shinobu — ( only until the anime )

GENSHIN IMPACT. albedo diluc kaeya childe venti xiao thoma zhongli kazuha yoimiya amber jean chongyun bennett xingqiu hu tao ayaka beidou fischl barbara scaramouche eula keqing ningguang beidou lisa aether lumine ayato ei yae miko — ( updated w/ mostly everything, but not well knowledgeable on character stories? )

TEARS OF THEMIS. luke artem vyn marius — ( no spoilers for character episodes )

FIRE EMBLEM THREE HOUSES. dimitri felix sylvain dedue ingrid annette mercedes claude hilda lysithea edelgard // PLATONIC / FAMILIAL ONLY : jeralt // — ( not complete list yet ? // all routes, but not complete w/ black eagles / ashen wolves )

FINAL FANTASY VII. aerith cloud tifa sephiroth zack reno rufus // PLATONIC / FAMILIAL ONLY : barret marlene angeal // — ( not complete list yet ? // original & remake okay, but not finished with original )

FINAL FANTASY XIV. g'raha alisaie alphinaud hythlodaeus emet-selch elidibus magnai y'shtola thancred urianger moenbryda lyse cirina sadu lyna ryne gaia lue-reeq — ( NOT COMPLETE LIST YET ? // endgame & mostly all side quests )

FINAL FANTASY XV. prompto noctis // PLATONIC / FAMILIAL ONLY : gladiolus ignis lunafreya iris // — ( not complete list yet ? // base game + dlcs, but not very knowledgeable on dlcs as i haven’t played yet )

FINAL FANTASY TYPE-0. to be updated

GRANBLUE FANTASY. link to the list ( on my gbf sb! )

PERSONA 5. akira/ren/joker ryuji ann yusuke makoto futaba haru akechi sumi mishima sae tae // PLATONIC / FAMILIAL ONLY : sojiro justine caroline // — ( not complete list yet ? // royal )

OBEY ME. lucifer mammon leviathan satan asmodeus beelzebub belphegor solomon barbatos — ( not complete list yet ? // )

TWISTED WONDERLAND. to be updated [ soon ]

ENSEMBLE STARS. to be updated [ soon ]

PROJECT SEKAI. to be updated [ soon ]

TOKYO REVENGERS. to be updated [ soon ]

CHAINSAW MAN. to be updated

SPY X FAMILY!. loid yor // PLATONIC / FAMILIAL ONLY : anya [ soon ]

PERSONA 3. to be updated

PERSONA 4. to be updated

. . . + possibly for others too ! feel free to inquire ? ^^

#⤹ ✰ — navigating the starry sky !!#please follow these rules before suggesting / requesting <3 tysm !!#you can check out my rentry for other medias i'm into ^^

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Akiko Tamura and Akira Ishihama in Boyhood (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1951)

Cast: Akira Ishihama, Akiko Tamura, Chishu Ryu, Renaro Mikuni, Toshiko Kobayashi, Mutsuko Sakura, Takeshi Sakamoto, Ryuji Kita. Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita, Sumie Tanaka, based on a novel by Isoko Hatano. Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda. Art direction: Tatsuo Hamada. Music: Chuji Kinoshita.

It's easy to see why Keisuke Kinoshita was one of Japan's most popular directors: He had that audience-pleasing ability to create identifiable characters and familiar situations, along with a sincere desire to make a statement about ordinary people caught up in the sweep of history. Like his Twenty-Four Eyes (1954), Boyhood is about people in wartime but not where the conflict rages most fiercely -- the conflicts in Boyhood are interpersonal and internal, not international. Ichiro (Akira Ishihama) is a 15-year-old boy, too young to fight in the war. When his family -- mother, father, two younger brothers -- relocates to the country during the war, Ichiro chooses to stay behind in Tokyo so he can continue his studies. But the first air raid finds him on a train to see his family, and when he returns to school he finds that he has fallen behind the other students and is stigmatized for his flight. So he joins his family in the country and starts at a new school, where he is an outcast, in part because the rural people treat the refugees from the city with scorn. He also feels at odds with his father (Chishu Ryu), an intellectual who tacitly disapproves of the war, and is disturbed by the fact that his mother (Akiko Tamura) does most of the work to keep the family fed and housed, while his father continues with his studies. Ichiro is regarded as a weakling by his fellow students, and the teachers, most of whom preach the militaristic virtues of strength and self-sacrifice, do little to help. When the lake freezes over in winter, for example, Ichiro finds that he is incapable of learning to skate, and though he makes a determined effort, he's mocked for his failure. Not as wrenchingly sentimental as Twenty-Four Eyes, Boyhood still elicits strong feeling because Kinoshita sticks with Ichiro's point of view -- his desire to fit in, his closeness to his mother, and his confusion about his father's distance from the reality of what is happening around them. At the conclusion of the film there's a measure of triumph in the defeat of militarism at the war's end, but there's also a feeling of a lack of resolution to Ichiro's story.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nozomi Tanaka, Tama, 2017, paint on hempcloth, Gofun (chalk), Mud Pigment, mineral pigment, sumi, foil, 220 x 273 mm #nozomitanaka

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TropicaRouge Pretty Cure casts:

Manatsu Natsumi/Cure Summer: Ai Farouz (Alice Peperoncino - Kiratto PriChan)

Sango Suzumura/Cure Coral: Yumiri Hanamori (Gin Minowa - Yuki Yuna wa Yuusha de Aru: Washio Sumi no Shou)

Minori Ichinose/Cure Papaya: Yui Ishikawa (Hinaki Shinjou - Aikatsu!)

Asuka Takizawa/Cure Flamingo: Asami Seto (Wilbell voll Erslied - Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk)

Laura: Rina Hidaka (Prelati - Senki Zesshou Symphogear AXZ)

Pururun: Aimi Tanaka (Umi Katou - Summer Pockets)

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

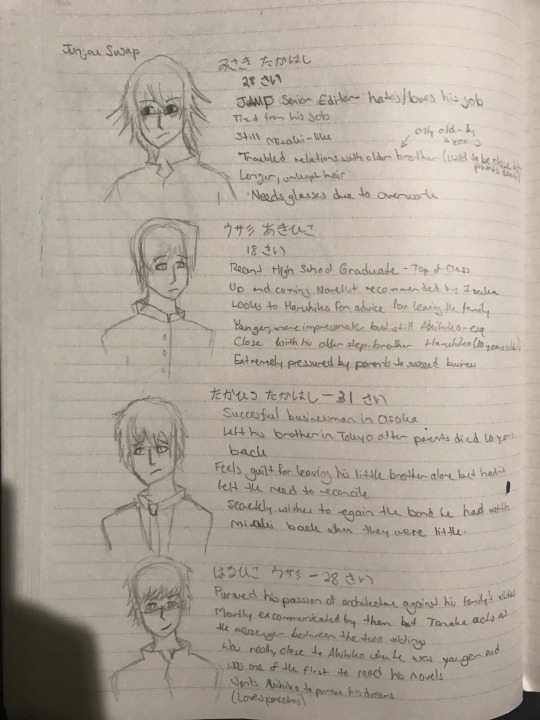

Everyone it’s Junjou Swap!

The basic deal is that everyone swapped positions from their significant other with some traits still holding. Most of the characters personalities stay pretty consistent with a few exceptions.

Young Akihiko Usami has always had a passion for writing novels and his big chance is finally received once Asahina, son of the lead of Marukawa publishing, directs him to a young novelist competition. However many things block his path with the consistent pressure from his parents to succeed the family business once his older half-brother Haruhiko got ex-communicated from them due to pursuing his dreams of becoming an architect. Thankfully, Usami butler Tanaka acts as their secret messenger between the close brothers as Haruhiko keeps encouraging to follow his heart away from the family business.

Misaki Takahashi is a 28 year old young man who has had a relatively normal life after the death of his parents at the age of 18. Unfortunately, he isn’t exactly satisfied with his current situation as a permeating sense of isolation confounds his lifestyle. Once his parents died, his older brother Takahiro ,age 31, and him never really spoke again. There seems to be some shared resentment between the two brothers yet an undeniable feeling of reconciliation that they want to attain if only one would reach out to the other. Being that he was never raised by his brother, this Misaki isn’t as confounded by not causing other people problems but still is more thoughtful than the rest due to living up on his own after high school and having to deal with the harsh realities of adulthood without any affluent novelist at his side.

At least, not until now.....

Aside from the cheesy character intros I would think that Misaki and Akihiko first meet after Misaki stays late at work one night and sees Akihiko hesitating to turn in his manuscript. He snuck out from his family home against his parents wishes and doesn’t want to go back therefore Misaki reluctantly offers him shelter. From there their relationship grows and yeah, they kiss and fall in love.

Some other interesting additions I’d like to add is Misaki’s coworkers at Japun, Sumi and Todo with chief editor Yokozawa leading the group (dream time amiright). Misaki and Todo are big fans of the up and coming mangaka Ijuuin sensei with his newest series ‘The Kan’. Sumi is kind of like Tsumori, but less of an asshole, and playflirts with Misaki making Akihiko jealous.

Aikawa is also a newly-hired literature editor who is starry-eyes with passion to make her new novelist Usami Akihiko a big hit. She’s very passionate and is full of energy.

Isaka is Asahina’s flirty secretary who always seems to cause him more trouble and people always wonder why he hasn’t been fired yet but most of the executives know why if you catch my drift.

I would say this AU focuses mainly on Romantica but feel free to add any other characters or bits of information. I want to make this into a fanfic but I’d also be happy to see any collaborative efforts! This AU was super fun to think about ❤️

21 notes

·

View notes