#Susa Iran

Text

Thrilling archaelogical dicoveries

TEHRAN—Archaeologists in western Iran have found over 1,000 clay seals (and fragments) along with other “important” relics estimated to date from the Elamite era (3200–539 BC).

“We unearthed arrays of important objects such as over 1,000 clay seals while conducting an urgent excavation on an archaeological hill in Kermanshah province,” IRNA quoted archaeologist Shokouh Khosravi as saying on Monday.

Moreover, a number of earthen animal figurines and counting objects belonging to the early Elamite culture have been discovered in these excavations, Khosravi, who leads the excavations said.

“Those objects are unique in their kind in western Iran,” she said.

The archaeologist said those findings mark the first archaeological materials of the Elamite period in the west of the central Zagros region

“The finding triggers fundamental changes in our understanding and knowledge about the situation of western Iran in the fourth millennium BC,” Khosravi stated.

During the excavation, which is authorized by the Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism, a large number of clay door locks, hundreds of pieces of container seals, and a cylinder seal were also found, which shows the site was an administrative center for organizing economic and exchange affairs in the early Elamite period, she explained.

“As the excavations continue, more information will be obtained about the nature and absolute history of settlement on the site.”

Experts say the Kermanshah region has had one million years of archaeological continuity, which is due to the geographical features such as a high number of springs and fertile soil.

Elam, or the Elamite kingdom, was one of the most impressive civilizations of the ancient world. Its territory was once in a region, which is now situated in the modern Iranian provinces of Ilam and Khuzestan.

However, according to sources, it was never a cohesive ethnic kingdom or polity but rather a federation of different tribes governed at various times by cities such as Susa, Anshan, and Shimashki until it was united during the Middle Elamite Period, briefly, as an empire.

The name Elam was given to the region by others– the Akkadians and Sumerians of Mesopotamia–– and is thought to be their version of what the Elamites called themselves– Haltami (or Haltamti)– meaning “those of the high country.” 'Elam', therefore, is usually translated to mean“highlands” or “high country” as it comprised settlements on the Iranian Plateau that stretched from the southern plains to the elevations of the Zagros Mountains.

Susa was formerly the capital of the Elamite Empire and later an administrative capital of the king of Achaemenian Darius I and his successors of 522 BC. Throughout the late prehistoric periods, Elam was closely tied culturally to Mesopotamia. Later, perhaps because of domination by the Akkadian dynasty (c. 2334–c. 2154 BC), Elamites adopted the Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform script.

Documents from the second period, which lasted from the 16th to the 8th century BC, are written in cuneiform; the stage of the language found in these documents is sometimes called Old Elamite. The last period of Elamite texts is that of the reign of the Achaemenian kings of Persia (6th to 4th century BC), who used Elamite, along with Akkadian and Old Persian, in their inscriptions. The language of this period, also written in the cuneiform script, is often called New Elamite.

Although all three stages of Elamite have not been completely deciphered, several grammatical features of the language are known to scholars. These include a plural formation using the suffix -p, the personal pronouns, and the endings of several verb forms.

Elamite language is an extinct language spoken by the Elamites in the ancient country of Elam, which included the region from the Mesopotamian plain to the Iranian Plateau. According to Britannica, Elamite documents from three historical periods have been found. The earliest Elamite writings are in a figurative or pictographic script and date from the middle of the 3rd millennium BC.

Just to notice how the name Elam was written, n the various languages of the ancient times: Liner Elamite:hatamti Cuneiform Elamite: 𒁹𒄬𒆷𒁶𒋾 ḫalatamti; Sumerian:𒉏𒈠 elam; Akkadian:𒉏𒈠𒆠 elamtu,hebrew:עֵילָם ʿēlām, Old persian:𐎢𐎺𐎩 hūja

Source: https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/489442/Amazing-archaeological-finds-dating-back-to-Elamite-era-unearthed

#Iran#ancient Persia#archaelogy#Kermanshah#Khuzestan province#Susa Iran#Elamite#Zagros mountain#archaeologist#TehranTimes#Travel Iran#ancient city#ایران#Tehrantimes

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dovetail joints in Achaemenid Palaces

Dovetail joints have been used in woodworking for thousands of years. About 2,500 years ago in ancient Iran (Persia) they were also used in the construction of Achaemenid palaces (such as Persepolis, Susa or Bardak Siah Palace in Bushehr province in the south of Iran). (550 to 330 BC). They were used to connect different stone parts of the structures.

Photo Source

Joining two pieces of stone with a dovetail joint at Persepolis.

This method has also been used in Urartu, Median, Egyptian, and Greek civilizations.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

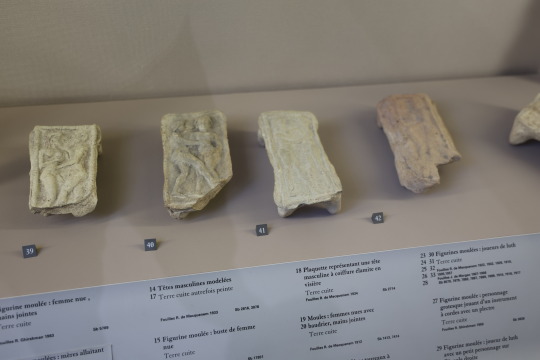

Terracottas from Susa, Iran

Middle Elamite period, 14th-12th centuries BCE

Musée du Louvre

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruins of Susa

#susa#ancient history#archaeology#antiquity#ruins#photography#landscape#ancient#history#ancient art#museum#archeology#iran#iranian

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A sphinx in Susa Shush, Khuzestan, IRAN

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bricks with a palmette motif

Achaemenid, ca. 6th–4th century BCE

Iran, Susa

Glazed ceramic

Collection Met Museum

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

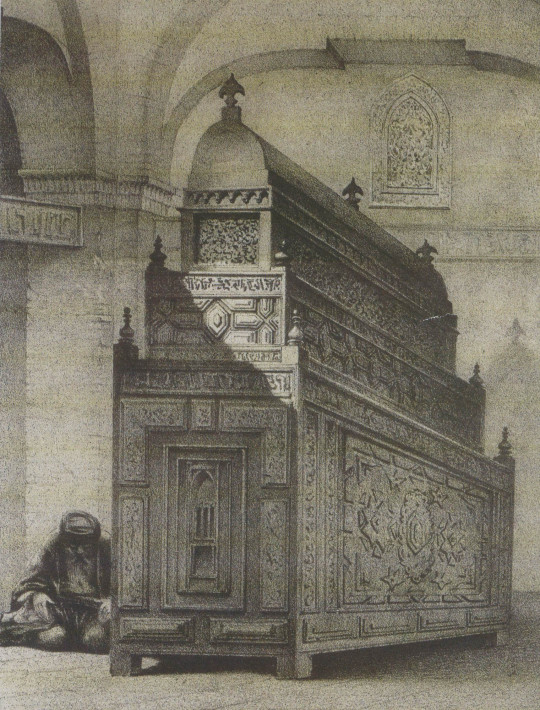

Esther, wife of the Persian king Ahasuerus, and her cousin Mordechai saved the lives of thousands of Jews in Susa from the intrigues of the king’s chief commander, Haman, as described in the biblical book of Esther, and is enacted every Purim in all the Jewish communities of the world. Ecbatana, the former capital of the Medes, and in our times Hamadan, was the summer residence of the Persian kings, to which Esther and Mordechai are said to have retired from the court after the death of Ahasuerus. Here they were buried in a common tomb, which is still the most important Jewish pilgrimage site in Iran.

We do not know how the original tomb looked. The modern building was constructed in 1602, in the time of Shah Abbas the Great. It follows with its double inner space, burial chamber, community room, and the dome crowning the tomb, the type of the Shiite pilgrimage sites erected for the emamzâdehs, the descendants of the holy Imams. As the first picture above shows, in the early 19th century it still stood outside of the city, but by the end of the century the local bazaar flowed around it. Thousands of Jews from Iran and other countries visited this place every year, covering a grueling trip to the desert surrounding Hamadan on foot or with caravan. According to contemporary travelogues, one could approach the tomb only with a local, through a maze of doorways and inner courtyards, with the way to the sarcophagi leading through a small rose garden and an ornate gate.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shirdal 'Lion-Eagle'

Talon Abraxas

Ancient origins of the griffin

A legendary creature with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion, the head and wings of an eagle, and, sometimes, an eagle's talons as its front feet first appears in ancient Iranian and Egyptian art dating back to before 3000 BCE. In Egypt, a griffin-like animal can be seen on a cosmetic palette from Hierakonpolis, known as the "Two Dog Palette", dated to 3300–3100 BCE. The divine storm-bird, Anzu, half man and half bird, associated with the chief sky god Enlil was revered by the ancient Sumerians and Akkadians. The Lamassu, a similar hybrid deity depicted with the body of a bull or lion, eagle's wings, and a human head, was a common guardian figure in Assyrian palaces.

In Iranian mythology, the griffin is called Shirdal, which means "Lion-Eagle." Shirdals appeared on cylinder seals from Susa as early as 3000 BCE. Shirdals also are common motifs in the art of Luristan, the North and North West region of Iran in the Iron Age, and Achaemenid art. The 15th century BCE frescoes in the Throne Room of the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos are among the earliest depictions of the mythical creatures in ancient Greek art. In Central Asia, the griffin image was later included in Scythian "animal style" artifacts of the 6th–4th centuries BCE.

In his Histories, Herodotus relates travelers' reports of a land in the northeast where griffins guard gold and where the North Wind issues from a mountain cave. Scholars have speculated that this location may be referring to the Dzungarian Gate, a mountain pass between China and Central Asia. Some modern scholars including Adrienne Mayor have theorized that the legend of the griffin was derived from numerous fossilized remains of Protoceratops found in conjunction with gold mining in the mountains of Scythia, present day eastern Kazakhstan. Recent linguistic and archaeological studies confirm that Greek and Roman trade with Saka-Scythian nomads flourished in that region from the 7th century BCE, when the semi-legendary Greek poet Aristeas wrote of his travels in the far north, to about 300 CE when Aelian reported details about the griffin - exactly the period during which griffins were most prominently featured in Greco-Roman art and literature. Mayor argues that over-repeated retelling and drawing or recopying its bony neck frill (which is rather fragile and may have been frequently broken or entirely weathered away) may have been thought to be large mammal-type external ears, and its beak treated as evidence of a part-bird nature that lead to bird-type wings being added. Others argue fragments of the neck frill may have been mistook for remnants of wings.

Lucius Flavius Philostratus (170 – 247/250 CE), a Greek sophist who lived during the reign of the Roman emperor Philip the Arab, in his "Life of Apollonius of Tyana" also writes about griffins that quarried gold because of the strength of their beak. He describes them as having the strength to overcome lions, elephants, and even dragons, although he notes they had no great power of flying long distances because their wings were not attached the same way as birds. He also described their feet webbed with red membranes. Philostratus says the creatures were found in India and venerated there as sacred to the sun. He observed that griffins were often drawn by Indian artists as yoked four abreast to represent the sun.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

did i see something about tusken inspo 👀

To be fair, it's like Tatooine inspiration at large. But yes, much many ideas :D

Oh this is going to be long... *crack knuckles*

Okay so Tatooine is inspired by Tunisia which is not a secret (for the folks that don't know, the name comes from the town Tataouine and the scenes in the movies were filmed in three other Tunisian cities). Added to that is the fact that the Tuskens were inspired by the Bedouins, a nomad people of north Africa.

Now, there is an Umayyad (medieval Islamic dynasty, 661-750) farm in Jordan named Qusayr Amra :

Which gives massives Tatooine vibes.

The Umayyads (and the Abbasid dynasty right after) rules over a large territory, which extend as far as the Maghreb. So the comparison of a Jordan farm to the Tunisia cities used for star wars is understandable.

Now those geographical and chronological markers give me a well of material to get inspiration for Tatooine and the Tuskens. (I includ the Abbasids because they're in the lineage of the Umayyads and the aesthetic match what I think would suit nicely for the Tuskens.)

The ceramic cup in the middle is Umayyad. The decor comes from an antic (Roman Empire) aesthetic that is still very present in this dynasty's art. Now you could replace those vigns by something more space looking, like space oasis flora.

The Kufic inscription would be out of place for the Tuskens. Except if we look into a Kufic calligraphy that appears a bit later which is composed with little characters adorning the letters. What I propose is that the Tuskens could have a sort of writing system composed of pictograms representing their signs. They could carve those pictograms on the cliffs as well as their ceramics or weapons...

This cup is not from north Africa I give you that (like the two next objects, it's from Susa in Iran. That site is way too rich and big....), but with it being Umayyad it doesn't betray the original inspiration for Tatooine. Plus it would look really cool and that's the most important.

(The vase on the left could also look really cool in a tusken hut I think)

All of those are Abbasids. I took the left picture for the bol in the centre but that green one looks great too (I think it's jadeite or nephritis but I'm not sure).

I just think they would look super cool as Tuskens ceramics. The jug on the right is a lil favorite of mine. It's a very luxurious object (both are really) because of the glaze. The blue is obtained with cobalt from Afghanistan (if I'm not wrong, I need to check) which was not an easy thing to get (we're at the 9/10th century here). But the technique itself and the forms are still simple enough that I think it'll mix well with a space nomad tribe culture in a desert.

Now we could look into other dynasties productions and I should look back at my notes on Middle and Near East Antiquity, because there most likely has more things to dive into there.

I don't think Tuskens would use much metal or if they do, it'll be forging with scraps bought from the Jawas. To cut and grave little pendants and ornaments, spikes, that kind of things. But I sort of think the only way to forge for them would be by using their ceramic kilns (if they have any and not just tempory holes dig specially for it), that's why I didn't look into Islamic metal production. I just don't think they'll have forges with them being nomad like that. But it's still a possibility of course.

Anyway, that was a little look into the ideas I've been munching on lately.

#heh not as long as i thought#(that's because i don't have access to my notes right now but that's just a detail)#sw#sw art and culture#tusken raiders#tusken#history#art history#hi tumblr void#tatooine

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royal Bodyguard. Persian glazed frieze from the Palace of Darius I in Susa, Iran, 521-486 BC. Pergamon Museum, Berlin

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polychrome glazed brick panel with sphinxes —emblem of the god Ahura Mazdā— from the palace of the Persian king Darius I at Susa (Babylonian: Šušim; now Shush, Iran) ~ ca.510 BC Louvre Museum

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terracotta figurine of a woman wearing a two-stranded necklace, anklets, and a sash

Old Elamite period, ca. 2112-1900 BCE

Susa (Iran, Khuzestan)

Musée du Louvre, Sb 2796

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persian Archers; dressed in richly decorative excavated from the Palace of the Darius (510 BC), Susa, Iran.

Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BC)

Pergamon Museum, Berlin

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stylized rendition of a woman (Goddess? Ereshkigal?) with two serpents and a bull-headdress.

Original cylinder seal c. 2400-2200 B.C (Old Akkadian period)

Found in Susa (Shush, Khuzestan Province, Iran)

Contained in Mohsen Froughi collection.

Cataloged in "The Art of Ancient Iran" by Edith Porada (1965)

#ereshkigal#allatu#arsay#goddess#egypt#egyptian gods#canaan#canaanite gods#phoenicia#phoenician gods#aram#aramean gods#syria#syrian gods#levantine gods#mesopotamia#mesopotamian gods#pagan gods#polytheism#archeology#magic#witchcraft#witchblr#paganblr#occult#elam#elamite gods#iran#ancient iran

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Legend of Queen Esther

For this week's culture blog, I read a scholarly article about whether or not Queen Esther and Mordechai were actually buried in Hamadan. This past weekend was the Jewish holiday of Purim, a celebration of Queen Esther, the Jewish wife of a Persian king who revealed her religious identity when one of the King's advisors announced his plan to exterminate the Jewish people in the kingdom. Esther is celebrated as she revealed to the King that she too was Jewish and encouraged him to stop the advisor, Haman's, evil plot and thus saved the Jewish people in the kingdom.

In Hamadan, Esther and Mordechai are allegedly buried in a set of modest tombs and its location is recognized as the only holy place for Jews in Persia. In 1067, Jewish Persian source Sahin describes Esther and Mordechai's dreams before dying inside the synagogue that their tombs are now in front of. There aren't any other sources on their place of burial until the 1850s, when Israel Ben Joseph visited Hamadan and explained how the Persian Jews came to the tombs once a month to pray and said that there was a community of about 500 Jews in Hamadan and three synagogues. Yehiel Fischel Castelman, a Galician Jew, and Jakob Pollak, Naser Al Din Shah's physician, both described the tombs as magnificent and of great importance to the Jewish people.

In spite of all of these accounts and the traditions of the Jews of Persia, the archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld and the lack of sources outside of Persia that say Esther and Mordechai were buried in Hamadan argue that these tombs are not the burial place of Esther and Mordechai. Herzfeld instead says they were buried in Susa and that Susandokt, the daughter of the Jewish Exilarch actually resides in the tomb.

I found these stories really interesting because my grandfather was from Hamadan and I'd never heard of him mentioning any Jewish holy sites there. I also did further research and found out that the Iranian regime actually added the tomb to its national heritage list in 2008. It was really surprising to read about the actual location where an iconic biblical figure, Esther, is supposedly buried and to discover that it was in Hamadan. Growing up, my family always celebrated Purim because there are not many Jewish holidays that detail the stories of Persian Jews, and it was really cool to read that there is an actual tomb in Iran that is protected because of this story and the religious traditions of Iranian Jews and Christians.

https://www.ou.org/life/history/where_is_the_tomb_of_mordechai_and_esther/

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/esther-and-mordechai

tomb of esther and mordechai in hamadan

لورن

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

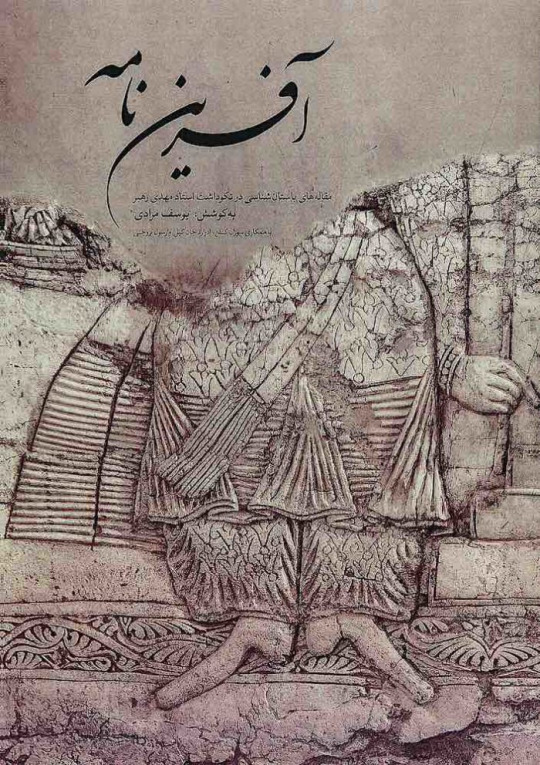

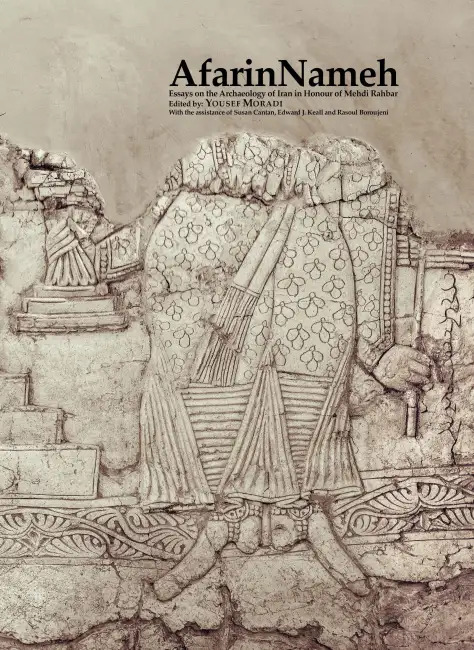

Afarin Nameh: Essays on the archaeology of Iran in Honour of Mehdi Rahbar; Āfrīnʹnāmah

آفریننامه: مقالههای باستانشناسی در نکوداشت استاد مهدی رهبر

Editors: Yousef Moradi, with the assistance of Susan Cantan, Edward J. Keall and Rasoul Boroujeni

Publisher: The Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism (RICHT), Tehran, 2019

Table of contents of English section

Antigoni Zournatzi: “Travels in the East with Herodotus and the Persians: Herodotus (4.36.2-45) on the Geography of Asia”

Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis: “From Mithradat I (c. 171-138 BCE) to Mithradat II (c. 122/1-91 BCE): the Formation of Arsacid Parthian Iconography”

D.T. Potts and R.P. Adams: “The Elymaean bratus: A Contribution to the Phytohistory of Arsacid Iran”

Vito Messina and Jafar Mehr Kian: “Anthrosol Detection in the Plain of Izeh”

Rémy Boucharlat: “Some Remarks on the Monumental Parthian Tombs of Gelālak and Susa”

Edward J. Keall: “Power Fluctuations in Parthian Government: Some Case Examples”

Bruno Genito: “Hellenistic Impact on the Iranian and Central Asian Cultures: The Historical Contribution and the Archaeological Evidence.”

Pierfrancesco Callieri: “A Fountain of Sasanian Age from Ardashir Khwarrah”

Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi: “The Gravity of New City Formations: Change in Settlement Patterns Caused by the Foundation of Gondishapur and Eyvan-e Karkheh”

St John Simpson: “The Land behind Rishahr: Sasanian Funerary Practices on the Bushehr Peninsula”

Barbara Kaim: “Playing in the Temple: A Board Game Found at Mele Hairam, Turkmenistan”

Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Jebrael Nokandeh and Davit Naskidashvili: “The Great Walls of the Gorgan Plain Explored via Drone Photography”

Jens Kröger: “The Berlin Bottle with Water Birds and Palmette Trees”

Carlo G. Cereti: “Once more on the Bandiān Inscriptions”

Gabriele Puschnigg: “East and West: Some Remarks on Intersections in the Ceramic Repertoires of Central Asia and Western Iran”

Matteo Compareti: ““Persian Textiles” in the Biography of He Chou: Iranian Exotica in Sui-Tang China”

Ritvik Balvally, Virag Sontakke, Shantanu Vaidya and Shrikant Ganvir: “Sasanian Contacts with the Vakatakas’ Realm with Special Reference to Nagardhan”

Antonio Panaino: “The Ritual Drama of the High Priest Kirdēr”

Touraj Daryaee: “Khusrow Parwēz and Alexander the Great: An Episode of imitatio Alexandri by a Sasanian King”

Maria Vittoria Fontana: “Do You Not Consider How Allāh … Made the Sun a Burning Lamp?”

Jonathan Kemp and John Hughes: “Analysis of Two Mortar Samples from the Ruined Site of a Sasanian Palace and Il-Khānid Caravanserai, Bisotun, Iran”

I found on the net the following abstract of the contribution of Antigoni Zournatzi to this volume, having as subject the Persian sources of Herodotus concerning the geography of Asia, although unfortunately for the moment I don't have access to the paper itself and more generally to this very interesting volume:

This paper considers a description of Asia in the work of Herodotus—a description that quite evidently further had implications for the manner in which this Greek historian perceived the shape and order of magnitude of the territories of Europe and Asia, as well as the overall form of the ‘inhabited’ world (oikoumenē). It supports the idea of a close affinity of Herodotus’ views in this instance with ancient Persian ways of looking at the world. Indications that Herodotus’ picture of Asia—and hence, his views about the form of the ‘inhabited’ world that are based upon this picture—must emanate from official Persian definitions of their realm derive, on the one hand, from the general coincidence of Herodotus’ Asia with Persian territorial realities, and on the other hand, from significant convergences that can be traced between Herodotus’ representation of the Asiatic continent and the Persians’ own perceptions and representations of their imperial domain.

Mehdi Rahbar is leading Iranian archaeologist.

4 notes

·

View notes