#Telfer Wall

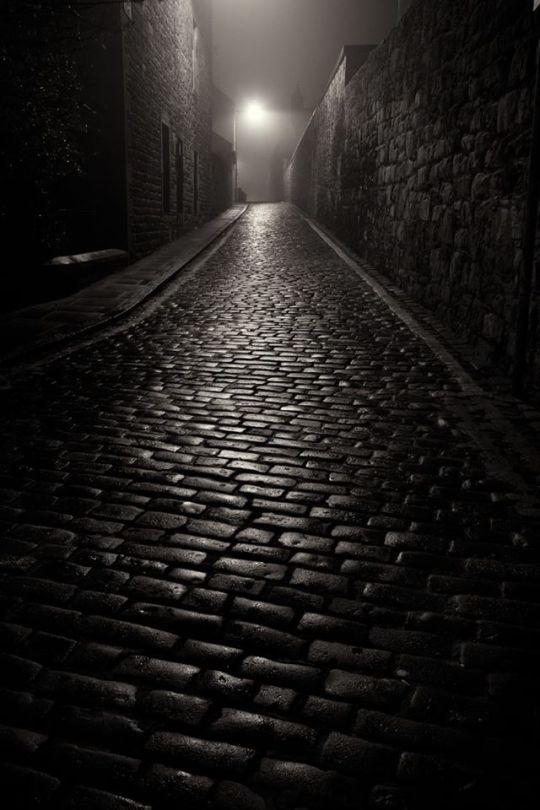

Photo

Castle from top of Vennel.

One of the most popular photo spots in the capital, but most people stop at the top of the steps leading from Grassmarket, this is a bit further up as you get to Keir street/Heriot Place, which lead up to Lauriston Place.

📸paul_watt_photography on Instagram

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

A comment on room design. I like the design for Uhura's room, which I assume is for the lowest ranking people on the ship.

The design of the sleeping pods feels in keeping with the overall design of the time. It has that clunky, thick feeling that gives it an air of 60's futurism, while also being clearly modern. The curved walls suggest the beds could be placed near the outer hull where the starship itself curves, which make it have the same kind of utilitarian feel as it would on an actual ship or submarine.

The use of enclosed pods also make more sense than the traditional bunk beds we see in Enterprise, since it gives you more privacy. Crewman Daniel's seemed to share his quarters with one other person.

Voyager also seemed to have more traditional bunk beds, as seen in Telfer's room in "Good Sheperd". Both Telfer and Tal had at least one roommate. We see very little of their rooms but we are shown they have separate beds with no privacy aside from covers.

In Undiscovered country they have rooms with at least 6 beds that look terrible to sleep in. Your pillow WILL fall out. You WILL hit your head on that pillar. Neither top or lower bunk are at a comfortable height. Atrocious design, 0/10.

The Strange New Worlds beds are more like a version of the Ds9 bunk beds, that have privacy screens. This is on the Defiant, so usually we see a lot of beds in a small space and even Sisko doesn't get a fancy room without the bunk beds. (From Past Tense).

This is clearly a reflection of cost, as much as intention in design. Telfer's and Daniel's rooms weren't going to be featured a lot, so they didn't create new set design pieces for those scenes. The cabins on the Defiant are featured a lot so they built those and I guess the same with Uhura's room.

This became an accidental deep dive into bed design for lower decks people so here you go I guess.

#Once again I get lost in Star Trek trivia#SNW#Ds9#Undiscovered Country#Voyager#ENT#Star Trek design#Star Trek aesthetic

449 notes

·

View notes

Link

The DAYS recap for Tuesday, December 27, 2022, backs up the theory that there’s really no such thing as coincidence. DAYS Recap Highlights In this episode, the walls close in and collap...

0 notes

Photo

Non-fiction titles about Serial Killers, for any murderino

The Kill Jar: Obsession, Descent, and a Hunt for Detroit's Most Notorious Serial Killer by J. Reuben Appelman

Four children were abducted and murdered outside of Detroit during the winters of 1976 and 1977, their bodies eventually dumped in snow banks around the city. J. Reuben Appelman was six years old at the time the murders began and had evaded an abduction attempt during that same period, fueling a lifelong obsession with what became known as the Oakland County Child Killings.

Autopsies showed the victims to have been fed while in captivity, reportedly held with care. And yet, with equal care, their bodies had allegedly been groomed post-mortem, scrubbed-free of evidence that might link to a killer. There were few credible leads, and equally few credible suspects. That’s what the cops had passed down to the press, and that’s what the city of Detroit, and J. Reuben Appelman, had come to believe.

When the abductions mysteriously stopped, a task force operating on one of the largest manhunt budgets in history shut down without an arrest. Although no more murders occurred, Detroit and its environs remained haunted. The killer had, presumably, not been caught.

Eerily overlaid upon the author’s own decades-old history with violence, The Kill Jar tells the gripping story of J. Reuben Appelman’s ten-year investigation into buried leads, apparent police cover-ups of evidence, con-men, child pornography rings, and high-level corruption saturating Detroit’s most notorious serial killer case.

Death in the Air: The True Story of a Serial Killer, the Great London Smog, and the Strangling of a City by Kate Winkler Dawson

London was still recovering from the devastation of World War II when another disaster hit: for five long days in December 1952, a killer smog held the city firmly in its grip and refused to let go. Day became night, mass transit ground to a halt, criminals roamed the streets, and some 12,000 people died from the poisonous air. But in the chaotic aftermath, another killer was stalking the streets, using the fog as a cloak for his crimes.

All across London, women were going missing--poor women, forgotten women. Their disappearances caused little alarm, but each of them had one thing in common: they had the misfortune of meeting a quiet, unassuming man, John Reginald Christie, who invited them back to his decrepit Notting Hill flat during that dark winter. They never left.

The eventual arrest of the "Beast of Rillington Place" caused a media frenzy: were there more bodies buried in the walls, under the floorboards, in the back garden of this house of horrors? Was it the fog that had caused Christie to suddenly snap? And what role had he played in the notorious double murder that had happened in that same apartment building not three years before--a murder for which another, possibly innocent, man was sent to the gallows?

The Great Smog of 1952 remains the deadliest air pollution disaster in world history, and John Reginald Christie is still one of the most unfathomable serial killers of modern times. Journalist Kate Winkler Dawson braids these strands together into a taut, compulsively readable true crime thriller about a man who changed the fate of the death penalty in the UK, and an environmental catastrophe with implications that still echo today.

Hell's Princess: The Mystery of Belle Gunness, Butcher of Men by Harold Schechter

In the pantheon of serial killers, Belle Gunness stands alone. She was the rarest of female psychopaths, a woman who engaged in wholesale slaughter, partly out of greed but mostly for the sheer joy of it. Between 1902 and 1908, she lured a succession of unsuspecting victims to her Indiana “murder farm.” Some were hired hands. Others were well-to-do bachelors. All of them vanished without a trace. When their bodies were dug up, they hadn’t merely been poisoned, like victims of other female killers. They’d been butchered.

Hell’s Princess is a riveting account of one of the most sensational killing sprees in the annals of American crime: the shocking series of murders committed by the woman who came to be known as Lady Bluebeard. The only definitive book on this notorious case and the first to reveal previously unknown information about its subject, Harold Schechter’s gripping, suspenseful narrative has all the elements of a classic mystery—and all the gruesome twists of a nightmare.

Mad City: The True Story of the Campus Murders That America Forgot by Michael Arntfield

In fall 1967, friends Linda Tomaszewski and Christine Rothschild are freshmen at the University of Wisconsin. The students in the hippie college town of Madison are letting down their hair—and their guards. But amid the peace rallies lurks a killer.

When Christine’s body is found, her murder sends shockwaves across college campuses, and the Age of Aquarius gives way to a decade of terror.

Linda knows the killer, but when police ignore her pleas, he slips away. For the next forty years, Linda embarks on a cross-country quest to find him. When she discovers a book written by the murderer’s mother, she learns Christine was not his first victim—or his last. The slayings continue, and a single perpetrator emerges: the Capital City Killer. As police focus on this new lead, Linda receives a disturbing note from the madman himself. Can she stop him before he kills again?

Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History by Tori Telfer

When you think of serial killers throughout history, the names that come to mind are likely Jack the Ripper, John Wayne Gacy, and Ted Bundy. But what about Tillie Klimek, Moulay Hassan, and Kate Bender? The narrative we're comfortable with is one where women are the victims of violent crime-not the perpetrators. In fact, serial killers are thought to be so universally male that, in 1998, FBI profiler Roy Hazelwood infamously declared that There are no female serial killers. Inspired by Telfer's Jezebel column of the same name, Lady Killers disputes that claim and offers fourteen gruesome examples as evidence. Although largely forgotten by history, female serial killers rival their male counterparts in cunning, cruelty, and appetite. Each chapter explores the crimes and history of a different female serial killer and then proceeds to unpack her legacy and her portrayal in the media as well as the stereotypes and sexist cliches that inevitably surround her. When you think of serial killers throughout history, the names that come to mind are likely Jack the Ripper, John Wayne Gacy, and Ted Bundy. But what about Tillie Klimek, Moulay Hassan, and Kate Bender? The narrative we're comfortable with is one where women are the victims of violent crime-not the perpetrators. In fact, serial killers are thought to be so universally male that, in 1998, FBI profiler Roy Hazelwood infamously declared that There are no female serial killers. Inspired by Telfer's Jezebel column of the same name, Lady Killers disputes that claim and offers fourteen gruesome examples as evidence. Although largely forgotten by history, female serial killers rival their male counterparts in cunning, cruelty, and appetite. Each chapter explores the crimes and history of a different female serial killer and then proceeds to unpack her legacy and her portrayal in the media as well as the stereotypes and sexist cliches that inevitably surround her.

The Spider and the Fly: A Reporter, a Serial Killer, and the Meaning of Murder by Claudia Rowe

In September 1998, young reporter Claudia Rowe was working as a stringer for the New York Times in Poughkeepsie, New York, when local police discovered the bodies of eight women stashed in the attic and basement of the small colonial home that Kendall Francois, a painfully polite twenty-seven-year-old community college student, shared with his parents and sister.

Growing up amid the safe, bourgeois affluence of New York City, Rowe had always been secretly fascinated by the darkness, and soon became obsessed with the story and with Francois. She was consumed with the desire to understand just how a man could abduct and strangle eight women—and how a family could live for two years, seemingly unaware, in a house with the victims’ rotting corpses. She also hoped to uncover what humanity, if any, a murderer could maintain in the wake of such monstrous evil.

Reaching out after Francois was arrested, Rowe and the serial killer began a dizzying four-year conversation about cruelty, compassion, and control; an unusual and provocative relationship that would eventually lead her to the abyss, forcing her to clearly see herself and her own past—and why she was drawn to danger.

#true crime#non fiction#nonfiction#nonfiction books#true crime books#reading list#tbr#Reading Recs#Book Recommendations#reading recommendations#book recs#murderino#murderinos#library#public library#book list#booklr

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Laurence Winram Telfer Wall in Heriot Place in the Fog Edinburgh 2014

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

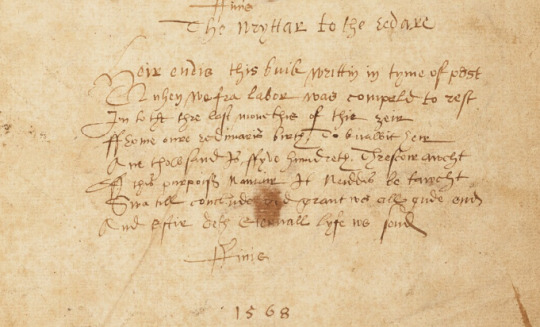

Plague Projects, 1568: George Bannatyne and His Books

“The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft agley” seems like a phrase which really sums up this past month, and also says something about my altered plans for this blog this year. After all, with the 700th anniversary of the Declaration of Arbroath coming up, I had hoped that the next time I’d be posting, it would be about nation-defining fourteenth century documents, not sixteenth century cultural treasures. Indeed, I should probably apologise to those of you particularly interested in earlier periods for publishing what I believe is my fourth or fifth lengthy sixteenth century post in a row- and it IS horrendously lengthy. But as many of us will be keeping to our homes for the foreseeable future, it seemed apt instead to consider taking a leaf out of George Bannatyne’s book.

In autumn and winter 1568, plague once again raged in Edinburgh. Confined to the family home “in tyme of pest, / Quhen we fra labor was compeld to rest”, 22-year old George Bannatyne whiled away the hours compiling a massive collection of Old Scots poetry. His book, containing works from such famous names as Chaucer, Dunbar, Henryson, Lindsay and others, is now known as the Bannatyne MS (or, to give it its less snappy title, Adv. MS. 1.1.6). It is widely acknowledged as one of the most significant books in the history of Old Scots literature, preserving some of the very best works of the age for later generations. So, since I have the time and the ink (metaphorically at least), I thought it might be a good opportunity to explore the history of this vital manuscript, the life of its author, and the circumstances in which it was created.

George Bannatyne was neither the son of a great noble nor some powerful churchman, but he did come from a reasonably well-off family with an important network of acquaintances. Thanks to the survival of a ‘Memoriall Buik’ which he began compiling around 1582, we are able to trace some of his background with more ease than might otherwise be the case. In it, we find that George was the son of James Bannatyne of the Kirktoun of Newtyle (born 1512) and Katherine Taillefeir (or Telfer or any number of variant spellings; she seems to have been born c.1523). James Bannatyne belonged to the legal profession and played a not insignificant role in public life, acting as a Writer to the Signet and Deputy Justice Clerk among other things. He also had mercantile interests and, despite originally hailing from Angus (a region he would maintain links with for the rest of his life), he was admitted as a burgess and guild brother of Edinburgh in 1538. It may have been around the same time that he married Katherine, who appears to have hailed from a prominent Edinburgh merchant family herself, and their first child, Laurence, was born in September 1539. The couple would go onto have twenty-three children between 1539 and 1565, of whom eleven were still alive at the time of their mother’s death in 1570, and eight were still living in their father’s house, “unput to proffeit”.

George was the seventh child, born on 22nd December 1545, and his memorial book notes that his uncles, George Taillefeir and William Fisher* acted as his godfathers, and Mavis Fisher as his godmother. Not much is known about his early life, but he does appear to have attended the University of St Andrews for a time, being incorporated at St Mary’s College in 1558 (aged about twelve) and listed as ‘baccalaurei’ in 1561. Unlike some of his brothers, however, there isn’t much evidence that he followed his father into the legal profession and we can ascertain little about his early career (beyond the basic details) before the age of forty.

(Bannatyne house near Newtyle, Angus. This property was purchased by George’s father James Bannatyne and the house built by Thomas Bannatyne in the late sixteenth century. Despite their Angus roots however, the family’s main business was in Edinburgh. Not my picture.)

The year 1568, when he was 22 years of age, would later serve as a major landmark in the young George Bannatyne’s life. Indeed, it was to be an eventful year for the kingdom of Scotland as a whole. In May, the deposed queen Mary I had escaped from captivity in the Kinross-shire castle of Lochleven, and soon raised an army to challenge the men who governed Scotland in the name of her infant son James VI. Defeated by the forces of her half-brother, the Earl of Moray, at the Battle of Langside, she then fled across the border to England, seeking the help of their cousin Elizabeth I. With the plight of the ex-Queen of Scots now an international incident, the affair would rumble on throughout the autumn and winter of 1568 and the publication of the notorious Casket Letters did nothing to diminish the scandal. Back in Scotland, meanwhile, the events of 1568 precipitated a major civil war between the supporters of the exiled Mary and the ‘King’s Men’ who fought in the name of her son. Even in August, Edinburgh had a scare when it was rumoured that the lords of ”the south and north and west countries” might attack before the next parliament, and as a result the burgh’s defences were reinforced.

And then, just to make things worse, that same autumn a vicious bout of plague broke out in the merry town. The Diurnal of Occurrents claims that ‘the pest’ was initially brought to Edinburgh by a merchant named James Dalgleish on 8th September 1568. Whether or not this very precise account can be taken at face value, by the end of the month the situation was so concerning that, on 26th September, the Regent Moray wrote to the burgh council from Tantallon, requesting that the election of new magistrates be delayed. This was due to concern for “the publict ordour to be observit anent the plaige”, and in case the new officials, “throw laik of experience may omyt the maist necessar thingis that in sa strait ane tyme ar requisit to be done”. On 13th October the burgh council made further proclamations that nobody was to pass to the Burgh Muir (where the sick were quarantined in huts) without an official escort, and, a couple of days later, officers were appointed to clean the victims’ houses and take charge of burying the dead. Meanwhile it was ordained:

“that how sone any maner of persoun fallis seik within this burgh, in quhatsumeuir kynde of seiknes that ever it be, the awneris of the hous inclose thame selffis and cum nocht furth of thair houssis, nowther suffer ony to resort to thame unto the tyme thai aduertice the baillie of the quarter and ordour be taiken be him, under the pane of deid.”

[“that as soon as any manner of person falls sick within this burgh, whatever kind of sickness it may be, the owners of the house should enclose themselves and not come forth of their houses, nor suffer anyone to resort to them, until such time as they inform the baillie of the quarter and order is taken by him, under pain of death.”]

Plague was hardly unknown in the capital and a particularly serious outbreak had ravaged much of Britain, including Edinburgh, as recently as 1563. The burgh was therefore used to the strict measures which had to be taken (even though this didn’t stop the unfortunate William Smith and his wife Black Meg from breaking the rules, an offence for which they paid dearly). Nevertheless the periodic recurrence of the the disease struck terror into the hearts of the people, and with good reason, since the 1568 outbreak alone is estimated to have decimated a fifth of Edinburgh’s population. There were major economic consequences too, not least because of the stoppage of trade, and the Diurnal of Occurrents claims that, due to the outbreak in the burghs of Edinburgh, Leith, and Canongate, there were severe shortages in the country over the course of the following year. Little wonder then that the earliest known medical treatise to be printed in Scotland- “Ane Breve Descriptioun of the Pest” by the Aberdonian physician Gilbert Skene- rolled off the press in this year.

[read more under cut]

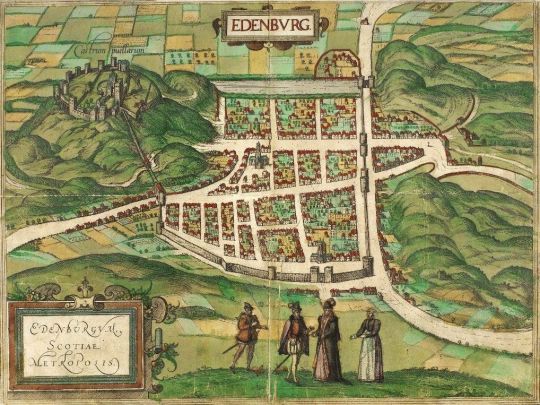

(Edinburgh in the late 16th and early 17th century, according to the ‘Civitates Orbis Terrarum’. Not my picture.)

This was the wider context in which George Bannatyne compiled his famous manuscript, in the last three months of the year (according to his own explicit). But the entire MS runs to almost 800 pages and shows signs of careful organisation and so some modern commentators have naturally raised doubts about the claim that such a large project was completed in only three months, no matter how much Bannatyne may have been climbing the walls during a time of isolation. We also have to account for the 54 pages which make up the so-called Draft or Duplicate MS- draft pages which do not form part of the main Bannatyne MS but have been tacked onto the front of the surviving copy. This draft MS, currently made up of at least two gatherings, may have been larger at some point, as leaves which seem to have been part of the Draft are to be found slotted in at various points of the Bannatyne MS proper (the two MS use different styles of page number, and it may be possible to identify some of the Draft MS leaves from their Roman foliation).

Meanwhile it was observed by J.T.T. Brown back in 1903 that one of the dates written into the manuscript as ‘1568′, on folio 290v., had originally been 1565, the last number having been altered at a later stage. Subsequently it was noticed that the year written as ‘1568′ on folio 298r. had initially been 1566, and it has been argued that the altered dates, as well as the obvious effort involved in organising and transcribing such a tome, suggest that the Bannatyne MS was the result of a much longer period of compilation than its author claimed. Not every commentator has been convinced by this- William, A. Ringler, for one, argued in 1980 that it was not impossible for George Bannatyne to have completed the work in three months, pointing out that he would only have had to spend about three hours a day on his project, and characterising the altered dates as mere slips of the pen. However most of the recent writers I’ve consulted seem to acknowledge that the MS was probably compiled in several stage, with the book only taking its final form in December 1568 after some months- possibly years- of intermittent work. The exact process of compilation is a matter of great interest to those attempting to establish a political and social context for the work. For example, Alastair A. MacDonald, asking the pertinent question of why Bannatyne might have wished to conceal an earlier start date (and assuming that the 1565 date was not a mistake), has argued that the Bannatyne MS could be seen as a Marian anthology. He has characterised it as a book which grew out of a collection of love poems associated with the poets of Mary I’s court (especially Alexander Scott), the nature of which had to be discreetly altered when the political winds changed. Whatever the case, the precise dating of the Bannatyne MS. and the manner in which it was compiled raises some fascinating possibilities and will probably continue to stimulate debate in the future.**

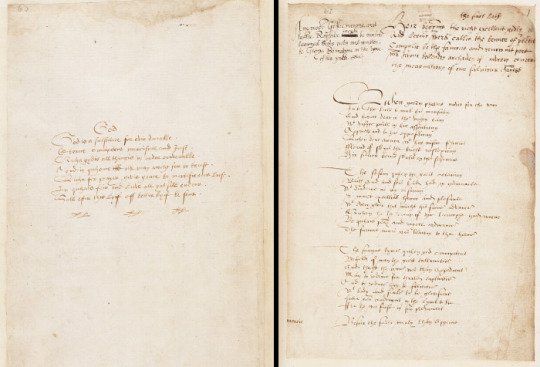

(A reproduction of a page from George Bannatyne’s ‘Memoriall Buik’. Not my picture, digitisation by internet archive)

The Bannatyne manuscript itself is an impressive piece of work and Evelyn S. Newlyn is certainly justified in describing its author as, “neither a mere collector nor a passive scribe”. On top of copying out around 400 poems and other literary works (some of them quite lengthy), it is clear that George Bannatyne put thought into the organisation of the MS and its overarching purpose and literary nature. The results of his endeavours hugely impressed some later readers, not least Sir Walter Scott, but modern scholars have rightly cautioned against viewing the MS as the product solely of one young man’s ‘genius’. Bannatyne’s broad social and family networks were likely crucial to the success of his project. Several other members of his immediate family had literary and scholarly interests- his father James and possibly also his brother Thomas owned (and in the latter case compiled) notable legal collections, while a copy of the “Regiam Majestatam” owned by George’s grandfather John Bannatyne has poems copied into its pages. George’s father James was probably also the figure of that name who was referred to in Robert Sempill’s “Defence of Crissel Sandelandis” in the line, “Auld James Bannatyne wes anis a man of skill”, and another lawyer Bannatyne, Patrick, appears elsewhere in the poem. On his mother’s side, George seems to have been related to Laurence Taillefeir, treasurer of Dunkeld, and proud owner of printed copies of Pleny and Seneca, who was also godfather to George’s eldest brother Laurence Bannatyne in 1539. Serving as the other godfather on that occasion was Henry Balnaves of Halhill, then a senator of the College of Justice, and perhaps already holding the strong Protestant views which would shape much of his career; he may be the ‘Balnevis’ listed as the author of a poem in the Bannatyne MS (“O Gallandis all, I cry and call”).

These details regarding the godparents of the numerous Bannatyne siblings may be found in George’s “Memoriall Buik” and among the other family acquaintances listed there we also find John Bellenden of Auchnoule and his father Master Thomas Bellenden. Bellenden of Auchnoule was justice clerk (and James Bannatyne served under him for a time as deputy) but even more interest are their connections as nephew and brother respectively to John Bellenden, archdeacon of Moray. That John Bellenden was a poet at the court of James V and translator of the prose Scots version of Hector Boece’s ‘Historia Gentis Scotorum’, and the close social (and perhaps family) relationship between the Bellendens and Bannatynes may explain the prominent position given to his work in the Bannatyne MS. Meanwhile, if Balnaves of Halhill and others provided the Bannatynes with Protestant connections, there were also members of the Catholic clergy to match them, such as George Clapperton, provost of Trinity Collegiate Church, and a member of the Chapel Royal at the same time as the poet Alexander Scott (who features prominently among the love poets featured in the MS). The court connections of the above men may have proved a major asset to George Bannatyne during the compilation of his MS, although it may be going too far to describe the book, as some writers have, as a direct record of Stewart court culture. The Bannatynes also had connections to Henry Foulis of Colinton and his father James, the notable neo-Latin poet, as well as to the poet William Stewart through the Foulis family (it is also worth noting that George Bannatyne’s daughter would later marry Henry Foulis’ grandson).

From documentary sources other than the memorial book, scholars have further traced the Bannatynes’ links to notable figures in Edinburgh’s printing trade, including King’s printer Thomas Davidson (who undertook work for the government in James Bannatyne’s company), and one of the city’s first printers Walter Chepman (both Walter and James were public notaries who witnessed some of the same transactions, and it might have been Chepman’s widow who stood godmother to George’s brother Thomas). The Bannatyne family’s connections to these notable individuals- and indeed many others whose histories we unfortunately don’t have space to trace- formed a hugely important social network of prominent lawyers, clergy, lairds, merchants, and courtiers, which must have proved immensely useful to George Bannatyne when he was gathering pieces for his MS.

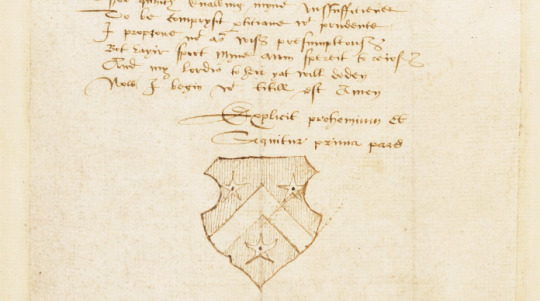

(The arms of the Bannatynes of Corehouse in the Bannatyne MS, set beneath part of the story of Cokelbie’s Sow. Not my picture, property of N.L.S.)

The manuscript itself reflects this background and, although Bannatyne complained that he had to draw on sources preserved in “copeis awld, mankit, and mutillait”, he also seems to have used printed sources. Equally the high number of poems that Bannatyne was able to pull together does seem to indicate that the situation wasn’t always so dire and, as Sebestian Verweij points out:

“Bannatyne’s access to enormous numbers of manuscript and print exemplars is the best available testament to the extremely rich literary and scribal cultures in the Scottish capital.”

The list of authors whose works appear in the MS is a long one, but the most important should be singled out, if only to further demonstrate the scale of the work. The works of some of Scotland’s greatest writers before Burns are included, including pieces by William Dunbar (including the “The Thistle and Rose”, “The Golden Targe”, “The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy, “The Lament for the Makars”, and many more); Robert Henryson (especially worth noting are his “Morall Fabillis” and the apposite “Ane Prayer for the Pest”); Gavin Douglas (including several prologues from his “Eneados”), and Sir David Lindsay (of particular interest is an abbreviated early copy of his play “Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis”). As already mentioned the works of John Bellenden, Alexander Scott and William Stewart are well represented, while other authors include Richard Holland, John Rowll, Robert Sempill, and Richard Maitland of Lethington (who also compiled major literary collections contemporary to the Bannatyne MS). “The noble Chaucer, of makaris flour”, is also named ias the author of eight poems in the MS, though seven of these are inaccurately attributed (the other is the ‘Song of Troilus’ from “Troilus and Criseyde”). George Bannatyne seems to have included several poems of his own composition in his MS, although Theo van Heijnsbergen has suggested that two of the poems attributed to a Bannatyne which appear “more competent” than the others, might have been written by one of George’s family members instead. Numerous anonymous poems feature in the MS (and some have been given authors in annotations made by later hands), including some well-known titles such as “The Friars of Berwick, “Christ’s Kirk on the Green”, “Kynd Kittock”, and “Cokelbie’s Sow”. Bannatyne’s collection thus opens a window onto an impressive body of late mediaeval and sixteenth century Scots literature- and his achievement is all the more impressive in that around half of the 400 poems included in the MS are not known from any other source and would otherwise have been lost to us.

Bannatyne also put a good deal of thought into the construction of the MS, beyond simply copying out as many poems as he could find. The main part of the book is divided into five parts: firstly, poems about “Godis gloir and ouir saluation” and other Christian religious subjects; secondly, poems with serious moral or philosophical content; thirdly, ‘mirry’ and comic works (some verging on bawdy), including political and social satire; fourth supposedly poems about love, but also including works criticising love and poems against the evils of both men and women (but mostly women); and lastly tales that have some kind of allegorical significance, from Robert Henryson’s animal fables to dream allegories like “The Golden Targe”. This level of editorial awareness has been said to demonstrate Bannatyne’s care and attention in compiling the MS. But some of his editing choices have been less popular with modern scholars, not least his discreet censorship of some the more obviously Catholic aspects of the pre-Reformation poetry, to suit contemporary political circumstances. His decision to include a hefty number of overtly misogynistic poems at a late stage in the compilation of the MS has also been seen as indicative of both the wider political context and also his own personal views. Most interesting though is the evidence that Bannatyne modernised- or perhaps a more exact term would be ‘anglicised- much of the spelling in the poems he transcribed, giving them a more ‘neutral’ language that might have been meant to render the work more accessible to readers of his own day in both Scotland and England. Despite these (sometimes quite major) alterations to the texts of some of the most famous works of Old Scots literature, Bannatyne’s versions of the poems of Dunbar, Henryson, and others have often been used as the basis of modern scholarly editions even sometimes when better alternatives might have been available. Regardless of accuracy, a lot of energy was clearly spent on the organisation and editing of the MS, and many authors have argued that Bannatyne intended that the book should be printed and published. As Alastair A. MacDonald wrote:

“It nonetheless remains that the only credible explanation for the care lavished on the MS and in particular for the concern with the formal appearance of the collection, is that Bannatyne had indeed entertained the hope of seeing the volume in print. It was doubtless with this purpose in mind that he made all the subtle accommodations to Protestant feelings which have been detected in manuscript.”

There is some debate over this however and others have suggested that the work could instead have been intended for circulation in manuscript form among Bannatyne’s social network. Whatever the case the result of George Bannatyne’s labours is a very impressive collection of great significance for the history of Scottish literature- and certainly worth the three months or more he is supposed to have spent working on it.

On 22nd December 1568- George Bannatyne’s 23rd birthday- the burgh council of Edinburgh noted with some relief that it finally seemed as if “God of his mercye and gudnes hes metigait the raige of the pest within this toun”. So the officers who had been appointed to keep the regulations enacted during the time of the plaque were discharged. Unfortunately, their relief was somewhat premature: the disease would return by late spring 1569 and continued to menace the city for much of the year. We have little further indication of how the Bannatyne family coped during this difficult time, but we do know that our protagonist survived and would live to a good age. Strangely though, other than his memorial book (which he began compiling around 1582), we have no evidence of any further literary activity on George Bannatyne’s part. Instead we must follow the rest of his career in his role as a prominent merchant active in family life.

(The grave of George Foulis of Ravelston and Janet Bannatyne in Greyfriars Kirkyard. Picture from wikimedia commons.)

Until the death of James Bannatyne in 1583, aged 71, George was closely associated with his father’s activities. He was granted his first piece of property- a tenement in Leith- in 1572, and acquired others over the years. He also developed his career as a merchant (though we do not know what he dealt in) and was admitted to the merchants guild of Edinburgh in 1587, being described as a “merchand burgess of Edinburgh” the following year. Some time before this he had married Isobel Mawchan, the widow of an Edinburgh baillie, and the couple would go on to have three children- Janet, who was born on 3rd May 1587 (sharing her birthday with her late grandfather James), James who died aged eight in 1597, and a stillborn daughter. George was also stepfather to two children from his wife’s first marriage, Edward (b.1571) and Isobel Nisbet. George’s only surviving child Janet Bannatyne later married George Foulis, laird of Ravelston near Colinton (both now suburbs of Edinburgh) and later Master of the King’s Mint in Scotland- their gravestone can still be seen in Greyfriars kirkyard. Isobel Mawchan died in 1603, and her husband wrote of her that she “levit ane godly, honorable, and vertewis lyf all hir dayis. Scho wes ane wyis, honest, and trew matrone.” In his twilight years, George Bannatyne appears to have spent some time residing with his daughter and son-in-law at Dreghorn. We do not know the exact date of his death, although it has been determined that he must have died before December 1608. The last entry in his memorial book is for 24th August 1606, when he recorded another visitation of the plague:

“George Foulis, Jonet Bannatyne, his spous, my dochter, and I, George Bannatyne, thair fader, being dwelland in Dreghorne, besyde Colingtoun, the nureise infectit in the pest, being upoun ane Sounday and the secound day of the change of the mone, and Sanct Bartilmo his day; and scho deceissit upoun the Tysday nixt thaireftir, the 26 day of the same moneth. And efter ane clenging na forder truble come to our houshold, blissit be the Almichty God, off his Majesteis miracouluse and mercifull deliuerance.”

[“George Fowlis, Janet Bannatyne, his spouse [and] my daughter, and I, George Bannatyne, their father, being then resident in Dreghorn, beside Colinton, the nurse [was] infected of the plague, being upon a Sunday and the second day of the change of the moon, and St Bartholomew’s Day; and she died upon the Tuesday next thereafter, the 26th day of the same month. And after one cleansing no further trouble came to our household, blessed be the Almighty God, of his Majesty’s miraculous and merciful deliverance.”]

George Bannatyne’s two books survived their author, and both passed into the hands of his Foulis descendants. The Bannatyne MS remained in the hands of that family until 1712 (and several members of the family signed their names on the spare leaves of the book) and was donated to the Advocates Library in 1772. Over the centuries several notable figures have come into contact with the MS, not least Thomas Percy, Bishop of Dromore (author of ‘Reliques of Ancient English Poetry’) and Allan Ramsay (who used some of the contents in his ‘Evergreen’ anthology of 1724). Both men (Ramsay certainly) appear to have left their own marks on the MS, as have several anonymous hands, some of them adding extra poems on spare leaves. By the early nineteenth century, the fame of George Bannatyne’s compilation had secured for its author an eminent place in the eyes of Scotland’s literati, and the Bannatyne Club, which was founded in 1823 by Walter Scott and others to print works of Scottish historical and literary interest, was named for George. Strangely, though, at the time of the Club’s foundation, not much was known about George Bannatyne himself. It wasn’t until a few years later, when his “Memoriall Buik” was rediscovered among the papers of his descendant Sir James Foulis of Woodhall and published under the auspices of the Bannatyne Club in 1829, that historians were able to trace the story of Bannatyne and his manuscripts in any depth. The first printing of the Bannatyne MS in its entirety came quite late, with the Hunterian Club’s edition of 1896, but there have been other printings since, and the MS has lost none of its fascination for historians and literary scholars. For all its idiosyncrasies, the Bannatyne MS remains, along with the contemporary Maitland MSS, one of the most valuable literary compilations in Scotland’s history. Without the efforts of George Bannatyne and his circle of friends and family during those uncertain plague-ridden months in 1568, our knowledge of the state of literature in Britain during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries would be much darker.

“Heir endis this buik, writtin in tyme of pest,

Quhen we fra labor was compeld to rest

Into the thre last monethis of the year,

Frome oure Redimaris birth, to knaw it heir,

Ane thowsand is, fyve hundreth, threscoir awcht;

Off this purpoiss namair it neiddis be tawcht,

Swa till conclude, God grant ws all gude end,

And eftir deth eternall lyfe ws send.”

National Library of Scotland Digitisation

Hunterian Club Edition (x) (x) (x) (x)

Scottish Texts Society Edition

‘Memorials of George Bannatyne’ (includes extracts from the Memorial Book)

Notes and References:

* The actual word used for William Fisher is ‘eme’, in contrast to the word ‘uncle’ which is used for George Taillefeir. I may have to do some more digging to establish the exact relationship, but as ‘eme’ usually (though not always) meant uncle I had to go with that for now.

** Without wanting to bore the reader TOO much (and I am aware of how long the above post is) I also wanted to raise a question of my own about where the MS. might have been written in the hopes that someone might be able to help. This question may be the result of a gap in my reading but try as I might I can find no textual reference to the MS. having been compiled in a ‘country retreat’, as the N.L.S., Evelyn S. Newlyn, and others state. All I can find is William Tod Ritchie’s comment that a ‘local tradition’ in Angus claims that the book was written in the north-eastern turret of Bannatyne House, Newtyle. This property was obtained by George’s father James in 1562, but it’s not clear that the tower in question was actually in existence in 1568. Otherwise I’ve not been able to find a source for the statement that Bannatyne left Edinburgh for the country during the plague of 1568, though certainly this was something which those inhabitants of medieval and early modern towns who had the means did do (as in Boccacio’s ‘Decameron’). This did occur in Edinburgh in 1568/9 as well, as evidenced by a letter which the Bishop of Orkney sent to his brother-in-law Sir Archibald Napier of Merchiston (father of the famous mathematician John Napier) in the same year. In it he recommends that due to Merchiston’s proximity to the Burgh Muir where plague victims were then quarantined, Napier should send his children north or west of the city into the southern Highlands:

“for, be the nummer of seik folk that gais out of the toun, the muir is abill to be ouirspred, and it can not be bot throw the nearness of your place, and the indigence of thame that ar put out, thai sall continewallie repair aboutte your roume, and throu thair conversatioun, infect sum of your servandis, quhairby thai sall precipitat yourself and your children in maist extreme danger; and as I se ye hef foirsene the same for the young folk, quhais bluid is in maist perrell to be infectit first, and therefoir purpois to send thame away to Menteith quhair I wald wiss at God that ye war yourself, without offence of authoritie, or of your band, sua that your housss gat na skaith. Bot yit, Schir, thair is ane midway quhilk ye suld not omit, quhilk is to withdraw you fra that syid of the toun to sum houss upon the north syid of the samin, quairof ye may hef in borrowing quhen ye sall hef to do, to wit, the Gray-cruik, Innerlethis self, Weirdle, or sic uther placis as ye culd chose within ane myle; quhairinto I wald suppois ye wald be in les danger than in Merchanstoun; and close up your houssis, your grangeis, your barnis and all, and suffer na man cum therin, quhll it plesit God to put ane stay to this grete plage, and in the mean tyme, maid you to live upoun your penny, or on sic thing as comis to you out of the Lennos or Menteith; quhilk, gif ye do not, I se ye will ruine yourself”

In the absence of any evidence of the Bannatynes taking such measures, I would argue that it might still be possible that the MS was written in Edinburgh (in which case one has to wonder if Bannatyne ever witnessed a tenement’s inhabitants singing that popular hit ‘Ane Ballat Maid off the Tyme the Chefe put the Sunne schyne on Leith”). In any case, whether it was written in Angus or Edinburgh or somewhere else entirely, Bannatyne himself testifies that they were unable to go about their business as usual and so he may have found himself stuck in the house with parents, servants, and at least seven siblings- it is unclear whether this was conducive to his work on the manuscript!

Selected References:

- Obviously I consulted all three versions of the MS linked to above, as well as “Memorials of George Bannatyne”, printed by the Bannatyne Club (for the Memorial Book) and also linked above.

- “Extracts from the Records of the Burgh of Edinburgh, 1528-1557″, edited by J.D. Marwick

- “Memoirs of John Napier of Merchistoun”, by Mark Napier

- “An Urban History of the Plague: Socio-Economic, Political and Medical Impacts in a Scottish Community, 1500-1650″, by Karen Jillings

- “The Bannatyne Manuscript: A Sixteenth Century Poetical Miscellany”, J.T.T. Brown, in the Scottish Historical Review (link)

- “The Bannatyne Manuscript: A Marian Anthology”, A.A. MacDonald in the Innes Review

- “The Literary Culture of Early Modern Scotland”, Sebastian Verweij

- “The Interaction Between Literature and History in Queen Mary’s Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Manuscript and its Prosopographical Context”, by Theo van Heijnsbergen in “The Renaissance in Scotland: Studies in Literature, Religion, History, and Culture Offered to John Durkan”, edited by A.A. MacDonald, Michael Lynch, and Ian B. Cowan.

“The Wryttar to the Reidaris: Editing Practices and Politics in the Bannatyne Manuscript”, by Evelyn S. Newlyn

#A very long post I know but I figure we're all in lockdown we've got the time#Scottish history#British history#Scottish literature#plague#books#historical objects#sixteenth century#George Bannatyne#Edinburgh#Angus#Books and Treasures#everyday life#culture#People#poetry#burgh life#literary culture#literature#Living in medieval Scotland#James Bannatyne#Thomas Bellenden of Auchnoule#John Bellenden of Auchnoule#Bellendens of Auchnoule#Bannatyne family#Taillefeir family#Isobel Mauchane#James Foulis of Colinton#George Foulis of Ravelston#Foulis of Colinton

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

#lizzo#poster#art#indie#plants#pink#linedrawing#good#as#hell#songs#for#walls#artist#goodvibes#summer

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SUEDE: THE FAN-ISH INQUISITION

www.nme.com, April 5-7, 1999

You asked and they answered. NME caught up with Suede and put your questions to them.

Day 1 (April 5)

What’s the worst insult anyone’s shouted at you? (Fred Telfer, London)

Mat: “‘Effete southern wankers.’ Someone shouted that repeatedly through our first ever Scottish gig.”

Simon: “I was in the toilet at that gig, and this bloke came up to me and said, ‘Have you seen Sede? I’m going to smash their teeth in.’ I just pretended to be from Scotland. The hard part.”

Brett: “Someone once shouted, ‘You sound like Rod Stewart.'”

Mat: “No, they said, ‘We remember Rod Stewart.'”

Brett: “Oh, that’s it. That was at a time when everyone was into bands like The Wonder Stuff, and we were playing ballads. I think the Scottish crowd thought we were old hat.”

Brett, did your arse ever get sore from hitting it with your tambourine? (Kieren Kelly, Ireland)

Brett: “I used to get a lot of bruising, that’s why I don’t do it any more. I put my aggression into singing these days rather than self-flagellation.”

Are there any songs you wish you’d never written? (Debbie Harding, York)

Brett: “‘Stay Together’. I don’t know why, it’s just not one of my favourites. It was the sole time in our career when one of our records has been successful because of hype. We’ve been accused of that a lot, but that was the only time when it was true. It was just style over content.”

Neil: “I’ve only written three, so I haven’t got much to regret.”

I read somewhere that after you moved out of one of your flats, the council had to have it fumigated. Is that true? And do you like vacuuming as much as Nicky Wire? (Gary Regis, Leicester)

Mat: “That was in The Mirror, wasn’t it?”

Brett: “That’s a bit of an exaggeration. What happened was we were in the middle of a tour, and we finished a gig and I had one too many shandies and a couple of other things, and I was moving house.

“Me and a couple of friends were sitting on my bed while these removal men went around my house throwing things in plastic bags while we were off our tits. It was a bit of a mess when we left, and I apologise to the people who moved in afterwards.

“These days I find vacuuming and washing-up quite therapeutic. I hate having a messy house, it makes me really depressed, so I try to keep my environment clean.”

Which one of you has got the biggest ego? (Softywat, West Sussex)

Brett: “Definitely not me, ha ha. I don’t think any of us has got a big ego, to be honest. It’s another popular misconception about the band. We don’t all need to be pampered, none of us are that fragile. Possibly a few years ago, I had a bit of one, but I think I’ve managed to chip away at that. I don’t feel particularly ego-driven any more.”

If you could stick pins in a voodoo doll of anybody on earth, who would it be? (Kirsty Irving, Grimsby)

Brett: “I don’t have any bad intentions to anyone really. I think when you have bad intentions to other people, you’re just looking for someone else to blame for where you’ve gone wrong with your life. It’s just a coward’s way out, and I try not to entertain thoughts like that. So, nobody.”

What were the first records you bought? (Emily Mugford, Chertsey)

Richard: “My first record was ‘Thriller’ by Michael Jackson. I think I was about six.”

Brett: “‘Never Mind The Bollocks…’ by the Sex Pistols was the first album I bought, and the first single was ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Kate Bush.”

Mat: “I think it was ‘Abba – The Album’. The one with ‘Thank You For The Music’ on it, anyway.”

Neil: “Mine was ‘Another Brick In The Wall (Part Two)’.”

Brett: “Woah, what a record!”

Mat: “What a youngster!”

Neil: “I thought it was amazing.”

Brett: “I loved the video with all the kids and that. I used to have the sleeve painted on my wall. The headmaster.”

Simon: “Ever? David Bowie, ‘Low’. Shall I tell you why? I thought he was a punk, because he had orange hair. I then went out and bought ‘Never Mind The Bollocks…’ after that.”

Brett, were you good at games at school? (Clint Stone, Yeovil)

Brett: “Yeah, I was actually. When you’re young, sport is really important, or at least it was at my school. I held the school record for the 800m for a couple of years. I was a good middle-distance runner. I used to play for the county at football as well.

“It was the only way to avoid getting beaten up. All the bullies tended to leave the kids who were good at sport alone, and not take them into the corner of the field and kick shit out of them. I fancied being an athlete when I was a kid, and then what happens, you get into cigarettes and girls and pop music, and you just end up a fat bloated fool.”

Which member of Suede can drink the most beer? (Mike Crisp, Brighton)

Mat: “Richard, probably.”

Richard: “I don’t think so.”

Brett: “Well, you’re the one who regularly empties their mini-bar wherever we go. Even if we’ve got day rooms. He brushes his teeth with vodka, he does.”

Richard: “Not really.”

Brett: “Well, yes. Who are you trying to kid? This is the man who has a bar in his bag. You sit in the back of a taxi with him and when you get out there’s glasses littered everywhere. That’s no exaggeration. After the pubs shut, you don’t try to find a dodgy offie, you just look in Richard‘s bag. That’s the truth, Mate.”

Simon: “He drinks anything, him.”

What do you say to NME’s editor, who recently included you alongside Ocean Colour Scene, Cast and Reef in a list of bands who “have nothing to say” (NME, April 3)? (Dave Thorley, Shropshire)

Brett: “I don’t think it’s true, to be honest.”

Mat: “There’s always this assumption that if you have something to say, you have to say it in terms of politics and social conditions.”

Brett: “I totally agree. When we’re in places like Germany, we’re always asked, ‘Why are you not political?’ and my answer to that is always the same. If you don’t understand the politics of the songs, then you haven’t looked into them. The songs aren’t flag-waving, they’re more subtle than that.

“I think I’m getting more interested in the music as I’m getting older, but I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I don’t think you lose that fire for life. As long as you’re inspired and have a real passion and rage for your music, that’s something to say in itself. That’s not a cop-out, that’s just how I feel about music and the band.”

Brett, you’re always photographed wearing a silver bracelet. Who gave it to you? (Samantha Jones, London)

Brett: “It was from a fan, actually. Someone sent it to me for my birthday. It’s just a cheap, silver-plated one, but I like it. I’m quite superstitious, and I wear a lot of my jewellery for that reason. This bracelet is a perfect example, it’s been quite lucky. I wrote lots of the album wearing it, so it’ll continue to be on my wrist until something goes wrong.”

When was the last time you cried, and why? (Gontie Tommy, Belgium)

Brett: “I think the last film that I cried at was Watership Down when I was young. The closing scene was really fucking sad.

“My sister used to read books to me, she liked reading to me so much she used to pay me 2p an hour to listen. She’d read stuff like Watership Down and Lord Of The Rings, and I’d cry at that too.”

Simon: “I don’t think I’ve ever cried while watching a film.”

Brett: “Neil?”

Neil: “Nah.”

Simon: “Oh, he’s a butch lad.”

Day 2 (April 6)

Have you dumbed down your lyrics to the point where they’re patronising to the listener? (Tom Stubbs, Dartford)

Brett: “I don’t think they are patronising. If you want to look for intelligence in lyrics, there’s a lot more of it in simplicity. I think the lyrics to our new album are a lot more intelligent than anything on ‘Dog Man Star’.”

Mat: “There’s a difference between dumbing down and being universal. The majority of people who buy Suede records aren’t English, their first language isn’t English.”

Brett: “When you go abroad people are just mystified about what the early stuff is all about. This is an interview for an English music paper, so everyone knows all the cultural reference points, but there’s a whole world out there and I think it’s important to communicate to them as well.

“As I’ve said before, the blueprint for a lot of lyrics on this album came from reading writers I really like, like Camus. His words are just like a simple painting of a triangle or a square or something. There’s nothing clever-clever about them, they’re just there. They describe a situation with a couple of simple brush strokes. That’s what I was trying to do on ‘Head Music’, and if that’s patronising, then sue me.”

What sort of cigarettes do you smoke? (Laura Pike, Aberdeen)

Brett: “Benson & Hedges. It’s always been the same. Mat smokes Silk Cut, but then he doesn’t count.”

If you could be any character in EastEnders, who would it be? (Sarah Glanville, London)

Brett: “I quite like Matthew Rose. I like the real ones P Matthew, Tony, people like that. I can imagine being one of them, they’re in the same sort of age-band. I really like the Mitchells as well.

“Actually, I think I’d be like Phil in the old days. He’s lost the plot a bit as a character since he gave up drink, but I used to love Phil. I’d regularly have dreams about hanging out with him and Grant, and committing various crimes.”

Simon: “I’d be Ian Beale, because I’ve always wanted to own a 50p/’1 shop.”

Brett: “Everyone hates him though, he’s the most hated man in the square.”

Simon: “Suits me.”

Neil: “I’d be Reg Cox (Reg Cox was found dead in the first episode after never speaking a word P EastEnders Ed).”

Richard: “I’d like to be Nick Cotton, but I don’t think I could pull it off. Every time he’s been in it, it’s been great. The time he tried to murder Dot was brilliant.”

Brett: “The best one was when he came back and pretended to be a Christian. That was really sinister. And I love Dot Cotton. Charlie was great as well.”

Tell us about your brown rice diet… (Johnny Robinson, Kettering)

Brett: “I still eat brown rice every morning. You get hooked on it, because it’s just so clean and good for you. I’m really looking after my body at the moment. I spent so many years abusing it, it’s time to give it a break I think.”

Mat: “I met someone at a Super Furry Animals gig who was such a Suede fan he’d started just eating brown rice. I was trying to convince him that you don’t have to do that to be a Suede fan. He should have seen Brett a few minutes earlier, he had a whole load of prawns stuffed into his mouth.”

Brett: “You’ve got to make sure you get the right sort of rice. It can’t just be brown, it’s got to be wholegrain. What I recommend to our fans is go to a standard Indian restaurant and have a fish masala. That’s very nice. I eat like a horse these days. Brown rice just gives you energy.”

Brett, did you ever want to punch Damon Albarn? (Paperback Rioter, Walthamstow)

Brett: “Punch? Nah, I’m not a violent person. Lots of people have had a go at me, but you just have to learn to deal with it because you’re always going to be a target for someone.”

Suede always seem well-groomed. How vain are you? (Jackie Long, Manchester)

Brett: “Personally, I’m pretty vain. You can only afford not to be if you’re really confident about yourself. If you’re always sticking your face in front of a camera and looking like a dog, you try to do something about it, don’t you? I spend a lot of time looking in the mirror just to iron the creases and get rid of stray bits of fluff.

“Simon‘s quite vain. The first thing he does when he gets into a hotel room is unpack his huge case of toiletries. He’s got five different sorts of aftershave, you name it. So actually, he’s the vainest member of the band, and probably the best dressed.”

Simon: “Yes, I’m glad you’ve noticed my Gucci shirt. Mat‘s got the best shoes, though.”

Mat: “They’re from Prada.”

Richard: “They’ve still got that revolting stain on them.”

Mat: “(Sheepishly) Yeah, someone was sick on them. Me, actually.”

Brett, are you still an eco-warrior (A reference to a recently unearthed school essay in which Brett complained about vandals defacing trees)? (Leonard Brown, Portsmouth)

Brett: “Oh God! I was eight years old. Listen, right, all that stuff from my past, anyone who wants to criticise that, I’d like to ask them what they were like when they were that age. When you’re eight years old you’re not boozing and injecting drugs into your eyes, are you? You’re just into stupid things. And no, I’m not an eco-warrior, it’s not something that keeps me awake at night.”

Neil: “He does live in a tree, though.”

Brett: “I have concessions to a green lifestyle, but it’s only buying eco-friendly washing powder. I’m not obsessive about it.”

Is it true you only listen to your own music and surround yourself with people who admire you in obsessive and fanatic ways? (Moa Ranum, Sweden)

Brett: “No, that’s bollocks. A lot of my close friends are into the band, but there are a lot of friends who’ve never heard a Suede song. A lot of our friends are ravers, and the music we make has no connection with their life at all.”

Simon: “My best friend in Scotland hates us.”

Brett: “I don’t think we’re that fragile that we need a load of people telling us we’re great. I think we’ve grown out of that to be honest.”

Day 3 (April 7)

Does Neil like antiques? (Purple Girl, England)

Neil: “I’m glad you asked me that. Not really, and I hate watching The Antiques Roadshow. It’s always shown in the winter on Sunday evenings, and it’s really depressing. It’s always dark outside. It’s so English, and it’s all part of that dreary idea of what it is to be English. It’s really parochial, seedy, it’s all about poking your nose into someone else’s business.”

People bully me at school for liking Suede. What should I say to defend myself? (Barry Beautiful One, Carlisle)

Brett: “Tell them they’re the cowards. If they have to persecute someone to make their own lives seem better then that’s pathetic. Tell them we’re going to go up to their school and get them.

“I don’t know, when you’re into music at school it says a lot about your identity and personality, and a lot of it was about getting into trouble with other people. You have to break an egg to make an omelette, don’t you?”

Your life depends on collaborating musically with either Damon Albarn or Bernard Butler. Which one do you choose? (Derek Brodie, Manchester)

Mat: “Well, we’ve done one of them, so it would have to be Damon.”

Brett: “What song would we do? We’d probably do a cover of ‘I’ve Got A Lovely Bunch Of Coconuts’.”

Mat: “In a ragga stylee.”

Simon: “He’ll probably phone us up now and demand to know how we knew what he was working on.”

Have Suede become a parody of themselves? (John Rickleford, Kent)

Brett: “Not at all. Part of being in a band is being a parody. I don’t think anyone will listen to ‘Head Music’ and think it’s a parody of Suede. I think what we’ve done on it is develop the sound of the band, but keep to the heart of what Suede‘s all about.

“It’s true that there are certain constants in Suede‘s world that we go back to, but there’s a fine line between repetition and just having a lexicon of words to fall back on. Sometimes I fall the wrong side of it, but I like to have a palette of words that I use, like an artist has a style. That’s part of what makes Suede what they are.”

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once Upon a Series Rewatch Press Release--5x6 The Bear and the Bow

5x6 The Bear and the Bow

Synopsis: In a Camelot flashback, a chance encounter with Merlin, David, Hook and Belle gives Merida new hope in her quest to save her brothers from the usurping clans of DunBroch. Unwilling to leave anything up to fate, Merida brings Belle along on a dangerous journey that culminates with an invaluable lesson in bravery. In Storybrooke, Regina, Mary Margaret and David discover the spell that would allow one of Merlin’s chosen to communicate with him, but when Arthur fails to reach the missing sorcerer the heroes grow suspicious. Meanwhile, Emma commands Merida to kill Belle in hopes of forcing Mr. Gold’s heroic transformation. With Merida unable to disobey Emma’s orders, Gold must find the courage to fight for Belle’s life or risk losing her forever.

Written by: Tze Chun, Andrew Chambliss

Directed by: Ralph Hemecker

Starring: Ginnifer Goodwin (Snow White / Mary Margaret Blanchard); Jennifer Morrison (Emma Swan); Lana Parilla (Evil Queen / Regina Mills); Josh Dallas (Prince Charming / David Nolan); Emilie de Ravin (Belle French); Colin O’Donoghue (Captain Killian ‘Hook’ Jones); Jared Gilmore (Henry Mills); Rebecca Mader (Zelena); Sean Maguire (Robin Hood); Robert Carlyle (Rumplestiltskin / Mr. Gold)

Guest Starring: Liam Garrigan (King Arthur); Elliot Knight (Merlin); Amy Manson (Merida); Sinqua Walls (Sir Lancelot); Joana Metrass (Queen Guinevere); Paul Telfer (Lord Macintosh); Marco D’Angelo (Lord Macguffin); Josh Hallem (Lord Dingwall); Ingrid Torrance (severe nurse); Colton Barnert (brother #1); Jordan Olson (brother #2); Matthew Olson (brother #3); McKenna Grace (young Emma Swan); Tom MacNeill (peasant); Peter Marcin (Chief Bromden (mop patient)

The Bear and the Bow airs September 15 at 9:00 pm EST

1 note

·

View note

Text

Telfer Wall, Heriot Place

As you walk around the ancient city of Edinburgh you might notice several sections of a fortified wall that seem slightly out of place in relation to the other buildings that stand alongside them.

Most people only make it onto the steps at The Vennel to get the selfie pic with the castle in the background, I did that today too and will cover it in another post when I talk about the Flodden Wall.

This part of the wall is the "newer" section was constructed circa 1628-36 to enclose land that had been acquired by the town council, including the land now occupied by George Heriot's School and land south of Greyfriars Churchyard, close to the old Royal Infirmary.

The Telfer Wall, named after its mason, John Tailfer or Tailefer, was essentially an extension of the Flodden Wall. The Telfer Wall was also built of a local sandstone, but the blocks used in its random rubble construction are of a different colour and tend to be larger than those used in the Flodden Wall.

The first Port (gateway) in the wall from Edinburgh Castle where the wall started, was the West Port the road from the west into the Grassmarket at the foot of the Vennel Steps. West Port is more famous, or infamous nowadays for it's strip bars nicknamed the "Pubic Triangle" It was also the area that Burke & Hare lived.

The second Port on the wall was the Bristo Port which stood at what is now Forrest Road a plaque denotes its position, the next gateway was Potterrrow Port which would have stood at the south west corner of Edinburgh University building across Lothian Street.

The next Port was the Kow gate (Cowgate Port) which stood from the pleasance to St Mary's Wynd (Street) at the end of the Cowgate. The Main Port into Edinburgh the Nether Bow Port was next at the foot of the High Street and the final port was Leith Wynd Port that stood next to Trinity College Church which was at the edge of the Nor Loch. Below the Calton Hill in line with the Governor's House.

The most famous gate was at the bottom of The High Street and called The Netherbow Port. If you ever venture down there look for the brass plates on the road denoting where is was. The World's End takes it's name from this gate, for some, if you went out into Canongate it was the end of their world, as far as the people of Edinburgh were concerned, the world outside the walls was no longer theirs.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Former Rugby Sevens Captain Inducted Into World Rugby Of Fame

New Post has been published on https://newscheckz.com/former-rugby-sevens-captain-inducted-into-world-rugby-of-fame/

Former Rugby Sevens Captain Inducted Into World Rugby Of Fame

Former Shujaa Sevens Captain, Humphrey Khayange will be inducted into Rugby wall of fame 2021. This has been announced today by the World Rugby.

The Hall of Fame for rugby recognizes the players who have made an outstanding contribution in the rugby game throughout their careers. This includes demonstrating rugby’s character-building values of integrity, passion, solidarity, discipline and respect on and off the field.

Kayange, who has been inducted number 150, became a history maker with his Shujaa teammates when they lifted their first ever Rugby Sevens Cup Final victory in Singapore in 2016.

He appeared in the commonwealth games of 2014 and 2010.

He finished his career on the World Series as Kenya’s third highest points scorer in sevens, was also part of the panel that helped Rugby Sevens become an Olympic sport.

The other five legends inducted alongside him are Osea Kolinisau (Fiji), Huriana Manuel-Carpenter (New Zealand), Cheryl McAfee (Australia), Will Carling (England) and Jim Telfer (Scotland).

0 notes

Photo

https://www.thedodo.com/close-to-home/cat-tries-to-knock-down-tree-hanging-from-wall The Dodo Random Horse Wanders Into Guy's House And Makes Herself At Home No big deal 💅 BY STEPHEN MESSENGER PUBLISHED ON 12/05/2019 HORSESNEW ZEALAND The neighborly spirit is clearly alive and well in the town of Dunedin, New Zealand. Just ask this friendly local horse named Sharq. Ben Telfer-Hynes The other day, Sharq slipped away from her owner’s place to take a stroll around the neighborhood. What sort of adventures she had along the way is anyone’s guess, but we do know where she ended up. Sharq concluded her journey by strolling into a stranger’s house — where she quickly made herself at home. But what’s more remarkable, perhaps, is how casually Sharq was received. Here’s a Facebook post from the homeowner who suddenly found himself playing host to a horse: Imgur/geekgoat Despite having taken quite a few liberties as an uninvited guest, Sharq had found someone willing to make her part of his family if she needed one. Thanks to that post, however, Sharq's owner Ben Telfer-Hynes was alerted to what his horse had done. Surprisingly, it wasn't all that surprising. "She’s actually an inside horse, so it was no shock to me when I saw she was lurking inside this man's home," Telfer-Hynes told The Dodo. "I’m so glad that she was able to find such a lovely place to reside for a short while." Ben Telfer-Hynes The horse was safely returned to her proper residence without incident, but the story of her adventure that day isn't entirely inconsequential. It proves that in the town of Dunedin, New Zealand, a stranger is more like a friend you just haven't met yet. And the same holds true for neighbors who say "neigh." . . . . . #memes #meme #momos #cats #momos #fun #funny #dogs #dog #cheezburguer #lol #LMAO #cat #LMFAO https://www.instagram.com/p/B55yTJPFFuo/?igshid=17ojmg5e9dr3s

0 notes

Text

Building firm fined £900,000 after fatal wall collapse

Building firm fined £900,000 after fatal wall collapse

A company has been fined £900,000 after the death of an employee who died from head injuries when a wall collapsed on a construction site at Lyme Regis.

Bournemouth Crown Court heard how, on 2 June 2015, Thomas Telfer was working as a bricklayer employed by Capstone Building Ltd, when he was struck by falling masonry after a retaining wall failed as it was being back filled with concrete.

An investigation by the Health and Safety Executive found that the company had failed to appropriately manage the work that was being carried out at the site at Chatterton Heights, Lyme Regis and failed to ensure the health, safety and welfare of employees on site, including Thomas Telfer.

Capstone building Limited, which is in administration, were found guilty after a trial to breaching Section 2 and Section 3 of the Health and Safety at Work Etc Act 1974, were £900,000 and ordered to pay costs of £60,336.99.

The firm’s sole director, Stephen Ayles, of Lomond Drive, Weymouth, was found not guilty of the same charges.

Speaking after the hearing, HSE inspector Ian Whittles said: “This tragic incident could so easily have been avoided if the appropriate measures were in place to provide a safe working practice.

“Companies should be aware that HSE will not hesitate to take appropriate enforcement action against those that fall below the required standards.”

0 notes

Text

Facts About Matt Damon

Find out more about Matt Damon, who is an actor, screenwriter, producer and philanthropist

Bio

Matt Damon was born on October 8, 1970. He was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. His parents are Kent Telfer Damon and Nancy Carlsson-Paige. He has an older brother named Kyle Damon.

Family Background

Damon’s father is a stockbroker and his mother are an early childhood education professor at Lesley University. His older brother Kyle is a sculptor and artist by profession. His father belongs to an English and Scottish Ancestry whereas his father belongs to a Finnish and Swedish descent. Damon lived with his mother as their parents divorced at the age of two years old.

Physical Stats

Matt’s height is 5 feet and 10 inches. He has an athletic build with weight around 84 kilograms. His chest size is 43 inches, waist size is 32 inches and biceps size are 15 inches. His Blue eyes and Brown hair make him even more attractive.

Wife and Kids

Damon’s wife is Luciana Bozan Barroso. He married Luciana in 2005 after dating for two years. The couple have three daughters. Furthermore, he also has a step-daughter.

Awards Received

Matt Damon has won 27 awards out of the 94 nominations he received. He won 1 Academy Award, two Golden Globe Award, one American Cinematheque Award, 1 Awards Circuit Community Award, two Berlin International Film Festival Awards, 1 Blockbuster Entertainment Award, 1 Chicago Film Critics Association, Two Empire Awards, 1 Florida Film Critics Circle Award, 1 Humanities Prize, 2 Las Vegas Film Critics Society Award, 3 National Board of Review and one Online Film Critics Society.

List of Movies

· Mystic Pizza

· The Good Mother

· Field of Dreams

· School Ties

· Geronimo: An American Legend

· Glory Daze

· Courage Under Fire

· Chasing Amy

· The Rainmaker

· Good Will Hunting

· Saving Private Ryan

· Rounders

· Dogma

· The Talented

· Titan A.E.

· The Legend of Bagger

· Finding Forrester

· All the Pretty Horses

· Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back

· Ocean's Eleven

· The Majestic

· Gerry

· Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron

· The Third Wheel

· The Bourne Identity

· Confessions of a Dangerous Mind

· Stuck on You

· EuroTrip

· Jersey Girl

· The Bourne Supremacy

· Ocean's Twelve

· Howard Zinn: You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train

· Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D

· The Brothers Grimm

· Syriana Bryan

· The Good Shepherd

· Ocean's Thirteen

· The Bourne Ultimatum

· Youth Without Youth

· Running the Sahara

· Che: Part Two

· Ponyo

· The Informant!

· Invictus

· Green Zone

· Hereafter

· True Grit

· Inside Job

· The Adjustment Bureau

· Contagion

· Margaret

· Happy Feet Two

· We Bought a Zoo

· Promised Land

· Behind the Candelabra

· Elysium

· The Zero Theorem

· The Monuments Men

· The Man Who Saved the World

· Interstellar

· The Martian

· Jason Bourne

· The Great Wall

· Downsizing

· Suburbicon

· Thor: Ragnarok

· Unsane

· Ford v Ferrari

· Jay and Silent Bob Reboot

0 notes

Text

Check Out China's Alamo: How Just a Small Amount of Troops Took on a Japanese Army