#Théroigne de Méricourt

Photo

Portrait d’une femme traditionnellement identifiée comme Théroigne de Méricourt, par Jean Baptiste Jacques Augustin (1759-1832).

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want a bedroom like Théroigne

#frev#unsure as to how accurate this is considering how much writers#would embellish things#but its interesting nonetheless#théroigne de méricourt

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from Thierry Lentz on Napoleon and Women:

There is a widely held idea that the Consulate and the Empire put an end to the Revolutionary episode of the gradual accession of women to, if not equality with men, at least to a more equable place in society. This episode is often symbolised by the struggles of emblematic figures, such as the famous Manon Roland, Théroigne de Méricourt and Olympe de Gouges, the lesser-known Pauline Léon and Claire Lacombe, and even the more surprising Charlotte Corday and Marie-Antoinette. After the women’s march on Versailles on 5 and 6 October 1789, “women citizens” – who were in fact not legally citizens – took part in other “great Revolutionary days”, created clubs, published pamphlets and, more generally, demanded or petitioned for what was still far from being called “parity” or “gender equality”. Limited in numbers, this movement was nipped in the bud by the Convention, which repressed the leaders (several of the aforementioned heroines were guillotined), closed the women’s clubs, even postponed plans to develop education for girls and reversed the weak legislative advances that had been conceded. The first discussions on codification which began at this time confirmed this opposition, despite the maintenance of partial equality between spouses (particularly in matters of divorce) and the reduction, also very relative, of the scope of exclusions from professional life (which were not completely abolished until 1965). Social consensus, essentially created by men who alone had access to education, to the means of communication and to power, was then contrary to any idea of legal and political equality (that equality would not come until the 1970s!!). Any challenges on this point were stifled using an arsenal of different justifications, drawing on science, physiology, history, religious precepts, etc.

(Source)

#interesting#Manon Roland#Théroigne de Méricourt#Olympe de Gouges#Pauline Léon#Claire Lacombe#Charlotte Corday#Marie-Antoinette#Napoleon#Thierry Lentz#napoleon bonaparte#Bonaparte#women’s history#women#history#napoleonic era#napoleonic#convention#women’s March on Versailles#france#text post#1800s#1700s#1790s#19th century

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

" (...) le tableau, surmonté d’un bonnet phrygien en laine orné d’une cocarde révolutionnaire, illustre la double origine versaillaise et bretonne fondatrice du Club des Jacobins."

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

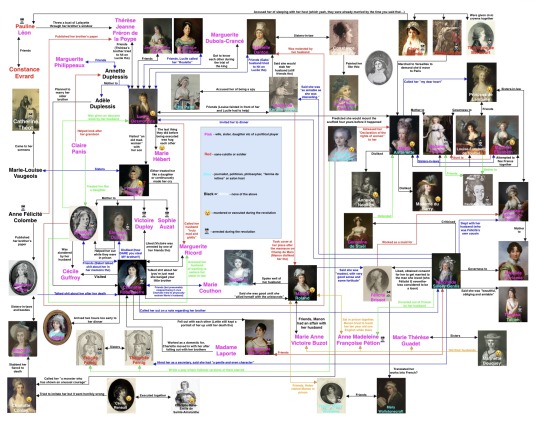

I decided to try this but for the girlies instead.

Are you sure want to click on ”keep reading”?

For Pauline Léon marrying Claire Lacombe’s host, see Liberty: the lives of six women in Revolutionary France (2006) by Lucy Moore, page 230

For Pauline Léon throwing a bust of Lafayette through Fréron’s window and being friends with Constance Evrard, see Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire (2006) by Claude Guillon.

For Françoise Duplay’s sister visiting Catherine Théot, see Points de vue sur l’affaire Catherine Théot (1969) by Michel Eude, page 627.

For Anne Félicité Colombe publishing the papers of Marat and Fréron, see The women of Paris and their French Revolution (1998) by Dominique Godineau, page 382-383.

For the relationship between Simonne Evrard and Albertine Marat, see this post.

For Albertine Marat dissing Charlotte Robespierre, see F.V Raspail chez Albertine Marat (1911) by Albert Mathiez, page 663.

For Lucile Desmoulins predicting Marie-Antoinette would mount the scaffold, see the former’s diary from 1789.

For Lucile being friends with madame Boyer, Brune, Dubois-Crancé, Robert and Danton, calling madame Ricord’s husband ”brusque, coarse, truly mad, giddy, insane,” visiting ”an old madwoman” with madame Duplay’s son and being hit on by Danton as well as Louise Robert saying she would stab Danton, see Lucile’s diary 1792-1793.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Marie Hébert, see this post.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Thérèse Jeanne Fréron de la Poype, and the one between Annette Duplessis and Marguerite Philippeaux, see letters cited in Camille Desmoulins and his wife: passages from the history of the dantonists (1876) page 463-464 and 464-469.

For Adèle Duplessis having been engaged to Robespierre, see this letter from Annette Duplessis to Robespierre, seemingly written April 13 1794.

For Claire Panis helping look after Horace Desmoulins, see Panis précepteur d’Horace Desmoulins (1912) by Charles Valley.

For Élisabeth Lebas being slandered by Guffroy, molested by Danton, treated like a daughter by Claire Panis, accusing Ricord of seducing her sister-in-law and being helped out in prison by Éléonore, see Le conventionnel Le Bas : d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve, page 108, 125-126, 139 and 140-142.

For Élisabeth Lebas being given an obscene book by Desmoulins, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre dissing Joséphine, Éléonore Duplay, madame Genlis, Roland and Ricord, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834), page 76-77, 90-91, 96-97, 109-116 and 128-129.

For Charlotte Robespierre arriving two hours early to Rosalie Jullien’s dinner, see Journal d’une Bourgeoise pendant la Révolution 1791–1793, page 345.

For Charlotte Robespierre and Françoise Duplay’s relationship, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 85-92 and Le conventional Le Bas: d’après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1902) page 104-105

For the relationship between Charlotte Robespierre and Victoire and Élisabeth Lebas, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre visiting madame Guffroy, moving in with madame Laporte and Victoire Duplay being arrested by one of Charlotte’s friends, see Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961)

For Louise de Kéralio calling Etta Palm a spy, see Appel aux Françoises sur la régénération des mœurs et nécessité de l’influence des femmes dans un gouvernement libre (1791) by the latter.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 198-207

For the relationship between Madame Pétion and Manon Roland, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 158 and 244-245 as well as Lettres de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 510.

For the relationship between Madame Roland and Madame Buzot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland (1793), volume 1, page 372, volume 2, page 167 as well as this letter from Manon to her husband dated September 9 1791. For the affair between Manon and Buzot, see this post.

For Manon Roland praising Condorcet, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 14-15.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 1, page 360.

For the relationship between Helen Maria Williams and Manon Roland, see Memoirs of the Reign of Robespierre (1795), written by the former.

For the relationship between Mary Wollstonecraft and Helena Maria Williams, see Collected letters of Mary Wollstonecraft (1979), page 226.

For Constance Charpentier painting a portrait of Louise Sébastienne Danton, see Constance Charpentier: Peintre (1767-1849), page 74.

For Olympe de Gouges writing a play with fictional versions of the Fernig sisters, see L’Entrée de Dumourier à Bruxelles ou les Vivandiers (1793) page 94-97 and 105-110.

For Olympe de Gouges calling Charlotte Corday ”a monster who has shown an unusual courage,” see a letter from the former dated July 20 1793, cited on page 204 of Marie-Olympe de Gouges: une humaniste à la fin du XVIIIe siècle (2003) by Oliver Blanc.

For Olympe de Gouges adressing her declaration to Marie-Antoinette, see Les droits de la femme: à la reine (1791) written by the former.

For Germaine de Staël defending Marie-Antoinette, see Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine par une femme (1793) by the former.

For the friendship between Madame Royale and Pauline Tourzel, see Souvernirs de quarante ans: 1789-1830: récit d’une dame de Madame la Dauphine (1861) by the latter.

For Félicité Brissot possibly translating Mary Wollstonecraft, see Who translated into French and annotated Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman? (2022) by Isabelle Bour.

For Félicité Brissot working as a maid for Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis: sur le dix-huitième siècle et sur la révolution française, volume 4, page 106.

For Reine Audu, Claire Lacombe and Théroigne de Méricourt being given civic crowns together, see Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel, September 3, 1792.

For Reine Audu taking part in the women’s march on Versailles, see Reine Audu: les légendes des journées d’octobre (1917) by Marc de Villiers.

For Marie-Antoinette calling Lamballe ”my dear heart,” see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 197, 209 and 252.

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Madame du Barry, see https://plume-dhistoire.fr/marie-antoinette-contre-la-du-barry/

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Anne de Noailles, see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 30.

For Louise-Élisabeth Tourzel and Lamballe being friends, see Memoirs of the Duchess de Tourzel: Governess to the Children of France during the years 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 and 1795 volume 2, page 257-258

For Félicité de Genlis being the mistress of Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon’s husband, see La duchesse d’Orléans et Madame de Genlis (1913).

For Pétion escorting Madame Genlis out of France, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis…, volume 4, page 99.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume, page 352-354

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Germaine de Staël, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 2, page 316-317

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théophile Fernig, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 300-304

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 106-110, as well as this letter dated June 1783 from Félicité Brissot to Félicité Genlis.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théresa Cabarrus, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume (1857) page 391.

For Félicité de Genlis inviting Lucile to dinner, see this letter from Sillery to Desmoulins dated March 3 1791.

For Marinette Bouquey hiding the husbands of madame Buzot, Pétion and Guadet, see Romances of the French Revolution (1909) by G. Lenotre, volume 2, page 304-323

Hey, don’t say I didn’t warn you!

#french revolution#frev#marie antoinette#pauline léon#claire lacombe#théroigne méricourt#reine audu#charlotte robespierre#éléonore duplay#élisabeth duplay#élisabeth lebas#lucile desmoulins#louise de kéralio#félicité de genlis#félicité brissot#mary wollstonecraft#manon roland#madame royale#charlotte corday#albertine marat#simonne evrard#catherine théot#madame élisabeth#sophie condorcet#françoise duplay#cécile renault#gabrielle danton#louise sebastien danton#theresa tallien#theresa cabarrus

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

long post, because i'm confused and need help from my mutuals.

this. this really confused me. more well-read mutuals help me if you can:

i'm mostly sure "suggesting a constitutional monarchy" was not the sole reason de gouges was arrested, tried, and executed, and it could not be the main reason. jean-paul marat was once a supporter of constitutional monarchy. Supplément de l’Offrande à la patrie did end with a message of hope for louis xvi to sort every grievance out while still being king. (and it was not just marat, this support for constitutional monarchy was widespread before louis xvi made the questionable decision to attempt to flee the country.) de gouges was executed after louis capet was, and the possibility of having a constitutional monarchy by then was certainly not as high.

i'm not so sure about what is meant by "anarchist beheadings". beheading as a method of execution is not anarchist on its own. beheading existed before frev, as did many, many other types of executions. the english did in ireland some of those other types of executions during the last 10 years of the 18th century, that is to say, at the same time as the frev happened. and we do not use the word "anarchist" to describe english attempts at disproportionately criminalising the irish. so putting the word "anarchist" immediately next to "beheadings" is something i genuinely cannot figure out on my own.

national assembly (20 Jun - 9 Jul 1789),

national constitutional assembly (the one that michel lepeletier worked in, 9 Jul 1789 - 30 Sep 1791),

legislative assembly (the one that made divorce far more accessible than before, 1 Oct 1791 - 20 Sep 1792),

and the national convention (21 Sep 1792 - 26 Oct 1795).

i don't think there was 1 position on the rights of women in any of these four. afaik the jacobins themselves were divided on how much social equality women could achieve. and the brissotins made the questionable decision to declare war on austria, which did not just mean that a very disorganised army was to be put into action, but that working-class women's lives were then affected by inflation and possible hoarding-and-profiteering of grains and of necessities.

again i have much more reading to do on this one.

many more women (e.g. louise-renée leduc, claire lacombe, pauline léon, théroigne de méricourt, félicité fernig, théophile fernig) had more stakes in the frev than de gouges did. often they would put their very lives on the line. their perceived femininity was not their primary concern, e.g. the fernig sisters kept being soldiers even when other soldiers were aware that they were women.

maybe as a tangent: mary wollstonecraft, despite her criticism towards the frev, was still much, much more welcoming of the frev than her theoretical opponent, edmund burke, and her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was translated into french within a year of being published. wollstonecraft lived in paris from 1792 to 1795, and was not persecuted (partly due to the protection of an american man, but still if any suspicion came upon wollstonecraft, it would be because she was english, not because she was a woman or a feminist thinker).

with the exception of leduc, every woman mentioned here died after 1793. now i am aware that this is a small sample size, and misogyny definitely existed during the 18th century (not surprisingly), but i cannot find in any primary source evidence suggesting the existence of a systematic exclusion of outspoken women or women of action or feminist thinkers.

i am aware that suffrage and/or being part of the national assembly (later national constituent assembly, later legislative assembly, later national convention) were not the only ways of participating in politics. working-class women in the 18th century not having the right to vote was sad when compared to working-class women in the 21st century having this right. but they were allowed to influence the men in their communities to vote, which was fortunate when compared to the lack of the right to vote in general in the old regime.

my general grasp so far is that, any kind of written or spoken output during the frev had very real risks attached, because literacy was quite low, and many "readers" of newspapers or pamphlets heard the contents by others retelling what was read out at cafés. spreading misinformation, or using gross invectives as marat called it, was not just unhelpful, but possibly damaging to the organisation of the urban poor.

now personally i do not believe that de gouges deserved to be executed, but that is because i do not believe anybody deserved or deserves to be executed. (that's for a different post.)

if male journalists such as hébert were losing their lives for misleading their readers and for unnecessary verbal violence, however, then de gouges being subjected to similar levels of scrutiny was a sign of equality -- for men and women of letters at the very least.

voting rights for women being granted only in the 1940s was

a) still a good thing. that it happened at all was a good thing. that it is still here is a good thing.

and

b) the result of feminist thoughts coinciding with economic and political realities. between the frev and the 1940s were three republics and two empires, and it would be reductive to blame what was delayed until the 1940s solely on the frev. feminism, as a group of schools of thoughts, did not doom itself because de gouges died.

and

c) still not equality yet. voting allows, but only allows, more women to think about the state that exercises disproportionate power over them, and to describe this state, and to study this state. i am reminded of a quote from dear Karl here.

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have some good sources about how women during the frev thought about universal male suffrage?

(i've been uncomfortable with some claims about how the frev was not feminist enough because women got the rights to vote in the 20th century, but cannot back up this discomfort.)

"I am quite limited on certain subjects and this is one of them (I am currently researching the exact thoughts of women during the French Revolution on universal suffrage).

Unfortunately, it has been a great shame that the French Revolution was misogynistic despite the meager rights that were gradually taken away from them over time. Even the greatest progressives like Sylvain Maréchal, who was an important disciple of Babeuf, had as a project to ensure that women did not have a say in the learning of reading.

The fact that misogyny was already present during the Ancien Régime (Marie Antoinette is blamed for all evils when in reality she did not have much say during her husband's reign, to better absolve Louis XVI and the policy of France under this absolute regime) or that Napoleon made the condition of women worse than that of Italy or Spain (I mentioned this in my post 'Women's Rights Suppressed') while being a great hypocrite does not absolve the revolutionaries for what they did in their misogyny.

There was a habit of attacking the wives of their adversaries to better discredit them (like Manon Roland, Marie Françoise Goupil, wife of Hébert, Lucile Duplessis, wife of Desmoulins), which is an interesting parallel on this point with the attacks against Marie Antoinette.

Olympe de Gouges spoke about the rights of women and citizens. Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, who demanded the right to organize in the national army. Théroigne de Méricourt, Louis Reine Audu, and again Claire Lacombe fought in the Tuileries and yet, despite being rewarded with a civic crown, they would not have the right to speak on universal suffrage.

Chaumette was a great misogynist, Robespierre too (one could tell me that he supported Louise de Keralio's candidacy for her entry into the academy, but in political matters, it was another story), Danton, Sylvain Maréchal, Amar, etc. I am not here to blame Robespierre and I deplore that there is a black legend about him, but one can see a certain purely political gesture in my opinion for the action he will take towards Simone Evrard.

As much as Simone Evrard is a very intelligent woman, with an extraordinary destiny very underestimated, capable of making very good political speeches (one of the people of the French Revolution that I admire the most), I wonder if the fact that Robespierre personally introduced her into the Assembly was just an opportunistic gesture because he would have had an additional reason to discredit Jacques Roux and Théophile Leclerc thanks to the speech she made while he was among the revolutionaries who approved the restriction of women's rights. Respect towards Simone Evrard regarding her dignity and intelligence (maybe even surely) opportunism, I would be tempted to answer on this by affirmative.

Risking repeating myself, Napoleon being a greater oppressor towards women by taking away the few rights they had, enacting oppressive and hypocritical laws, and even bloody ones concerning them, does not absolve the other revolutionaries of their sexism.

And there is no excuse that it was of their time (in fact, I noticed that this lie is used in my opinion to absolve Napoleon but not the revolutionaries, but forced to see that it fits into the same idea)... First of all, Charles Gilbert Romme was more progressive in women's rights, Marat and Charlier too, Camille Desmoulins thought that women could have the right to vote, Condorcet demanded gender equality, Guyomar opposed the exclusion of women from universal suffrage. Worse than anything, while the clubs and societies of women ended up being banned, which is a regression.

In 1795, for attempting to revolt against the Assembly which abolished the social policies of the Montagnards, they were prohibited from attending assemblies and even from gathering in the streets in groups of more than 5. Moreover, the term 'tricoteuse' to insult women was not invented during the Napoleonic era or the royalist era but in 1795.

What did women think about this? This is where I am quite limited because besides the answers I have given about these women and their actions, unfortunately, there is not much else I can say due to my limited knowledge.

In any case, I hope I have helped a bit to support the aforementioned statements.

In the meantime, I can provide some of my sources: the historian Mathilde Larrère, Antoine Resche who made very good summarized portraits of some revolutionary women on the website 'veni vidi sensi', I would also recommend reading the book by the writer Claude Guillon on Robespierre, women, and the Revolution (even though I completely disagree with some of his books that have been legally condemned, this one is rather good and he had a quite good blog on the French Revolution that I recommend checking out), and the historian Jean-Clément Martin, 'La révolte brisée'."

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Redraw from a painting of Théroigne de Méricourt

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"È tempo che le donne contrastino la vergognosa incompetenza in cui l'ignoranza, l'orgoglio e l'ingiustizia maschili le ha per così lungo tempo tenute prigioniere.“

Théroigne de Méricourt Rivoluzionaria francese

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ciara's Counsel - 07/30/2022

My AC podcaster friends - ACLandmarks and The Science of Assassin's Creed - are hosting another Assassin's Creed virtual tour & trivia session! To commemorate its celebration, we will be touring Colonial America during the Seven Year's War in Rogue tomorrow at 12:00 noon EST! Hope to see you there!

In case you missed it, here are the trivia questions from the Unity virtual tour:

Who is the person exploring the memories of Arno Dorian in Unity?

One of Arno's earliest missions with the Assassin Brotherhood was to protect Théroigne de Méricourt during what event?

How old were Jacob & Evie Frye when they met Jayadeep Mir, aka Henry Green?

During the events of Liberation, New Orleans was under the control of which country?

What is the name of Eivor's adoptive father?

How did Edward acquire a pair of hidden blades?

Who was against the idea of Eivor leading Ravensthorpe in Sigurd's absence?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

È tempo che le donne contrastino la vergognosa incompetenza in cui l’ignoranza, l’orgoglio e l’ingiustizia maschili le ha per così lungo tempo tenute prigioniere.

(Théroigne de Méricourt)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

president should’ve let them fight it out.

#frev#theroigne would have sent him packing#their friendship breakup is so funny#collot d'herbois#théroigne de méricourt

19 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Théroigne de Méricourt had swaggered in with duelling pistols attached to her belt and a sword at her waist. Famous for her outlandish behaviour, she did not want to discuss the rights of women, she wanted to act on them, preferably with her sword.

Charlotte Gordon on a famous French feminist in 1793 (Romantic Outlaws)

#charlotte gordon#Théroigne de Méricourt#feminism#feminist#romantic outlaws#french revolution#book quotes#book quote

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I know the Cordeliers Club allowed female members but considering even the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes did not allow its female members to be president, do you know if there were any limits put on female member participation in the Cordeliers Club or if there was a tiered membership more generally?

According to The women of Paris and their French Revolution (1998) by Dominique Godineau, the Cordeliers did allow women to speak during their debates, however, that is not to say they were seen as equals:

In the other great Parisian club, the Cordeliers, women did not have a deliberative voice either. But it is probable that this club gave them greater respect, for several female citizens declared that they belonged to it, which no woman ever asserted about the Jacobin club. Thus we have the female citizen Bébiant, “a member of the Cordelier Society since it was founded and through esteem nicknamed [by them] their aunt,” as well as the wife of Metrasse, who, ”just like a member of the Cordelier Society…has constantly attended their meetings.” Unlike the Jacobin club, the Cordelier club drew a female attendance that was primarily local. Several times, different police informers remarked that women were more numerous than men. They also mentioned the presence of ”women who were regularely in the galleries, those who always occupied the front row” and made ”motions before the meeting opened.”

The Cordeliers club also didn’t let women become members right from the beginning, as shown by this extract from number 14 (March 1 1790) of Desmoulins’ Révolutions de France et de Brabant:

On the request of Mademoiselle Théroigne [de Méricourt] to be admitted to the district with a consultive vote, the assembly followed the conclusions of the president, that they would vote to thank this excellent citoyenne for her motion; that a canon of the Council of Mâcon having formally recognized that women have a soul and reason like men, they can not be prohibited from making such good use of it as the speaker; that mademoiselle Théroigne and those of her sex will always be at liberty to propose whatever they believe to be advantageous to the fatherland, but as regards the question of state, as to whether Mlle Théroigne should be admitted to the district with a consultative vote only, the assembly is not competent to take sides on this question, and this is not the place to settle it.

In Journal du Club des Cordeliers: 1791 (which was the closest thing to minutes I could find for the club) I also only discovered one place where women really appeared at all:

Almost all the patriots seem to have forgotten the unfortunate Reine Odu [sic], one of the victims of the affair of October 5 and 6, by the infamous chatelet tribunal, and the only one who was plunged into the prisons. The National Assembly, by declaring, by a decree, that there existed no grounds for accusation against the main authors of this alleged conspiracy, has in fact annulled the monstrous procedure begun by this tribunal; and yet Reine Odu [sic], co-accused, against whom there therefore is no cause of accusation pronounced by the National Assembly, still groans in the horrors of harsh captivity! For some time now, the Society of Friends of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which does not measure the relief it brings to the oppressed or the rank they occupy in the world, because all men are truly equal before it, deeply indignant at such revolting injustice, has been attending to the means of breaking her chains; and it gave as her defender Mr. Desvieux, one of its members; a lawyer, as educated as he was eager to seize opportunities to relieve the unfortunate. M. Desvieux therefore went several times to the Châtelet prisons; and in one of the previous sessions of the club, he painted such a touching picture of the extreme misery to which the woman of the nation (this is what the prisoners of the castle had nicknamed the interesting Reine Odu [sic]) was reduced, that it was unanimously decided that the club would give her 3 livres per week; that it would have her put under protection, and that it would invite the other patriotic clubs of the capital, through commissioners appointed for this purpose, to unite with it to soften the fate of this woman. Several members wanted to give clothes which she completely was without; and on the observation made that it would be appropriate for a person of her own sex to carry them to her, Mlle. Lemaure, one of the ladies who most assiduously attend the sessions, was appointed by acclamation to fill this honorable role. Today the treasurer of the company (M. Coqueret) was authorized by an express mandate to hand over nine livres and ten sols to Miss Lemaure, to put Reine Odu [sic] under protection.

Judging by the same source, ”brothers and friends” or ”brothers and fellow citizens” also seems to have been the most common greeting to or from the club, so not a very inclusive area here either…

21 notes

·

View notes

Quote

A contemporary of Sade's who had dined next to him at the table of Charenton [Asylum]'s director...heard him say that the only woman for whom he had ever felt a genuine passion was none other than Théroigne de Méricourt...Full of admiration for her "strongly etched character," he was unstinting of his praise for the beautiful firebrand, whom he reportedly compared to certain biblical heroines. "I assure you," he allegedly added, "that there was something sublime in that girl."

Maurice Lever. Sade (1991)

Me:

#marquis de sade#cw sade#Théroigne de Méricourt#thp#i mean your mileage may vary on memoirs which lever points out immediately after i cut him off#but GEESH

22 notes

·

View notes