#The Puppetoon Movie

Text

youtube

The Puppetoon Movie (1987)

My rating: 4/10

So yeah, this is basically an anthology of old cartoons. The framing device is nonsensical and saccharine in a way that would make Disney blush (culminating in a bizarre bit where various advertising mascots appear out of nowhere to go "thank you, George Pal" into the camera), and while the shorts themselves are technically extremely impressive, most of them are also incredibly racist, even for the time.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Bettie Without Her Trademark Bangs

Source: The Puppetoon Movie - Cinemagic

Source: Benny Drinnon

#bettie page#bettiepage#sexy#beautiful smile#long hair#long legs#beautiful#betty page#high heels#profile#beautiful eyes#beautiful face#red lips#no bangs#beautiful lips#Bettie no bangs

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toon talk: In addition to having other movies lined up for release after the 2026 CAT IN THE HAT movie, Warner Bros. Pictures Animation is going through with a musical movie based on... MEERKAT MANOR. A docu-series from a long while ago... I think this shows where Zaslav's Warner animation priorities lie: Nerfing two Looney Tunes movies and multiple other stuff, but... Hey, gotta plug that Discovery stuff, huh? Anyways, it could be a fun movie and all. I mean we do have the first chunk of THE LION KING 1 1/2, but I suppose there's room for another animated meerkat musical? I dunno, it's a choice alright. And even then, it's really not guaranteed to go forward. Let alone be released after completion.

In very cool news, Martin Scorsese and Seth MacFarlane is working on an animation restoration project, preserving work for animation's Golden Age from the 1920s up through the 1940s. The films are largely Fleischer joints, in addition to two George Pal Puppetoons... And amusingly, the Terrytoons THREE BEARS cartoon from 1939... Ya know... THAT ONE:

Again, really cool of MacFarlane and Scorsese to do this. Taking the time to preserve animated treasures from one of its finest eras...

And we got to see concept art of a 2D animated character who will be appearing in INSIDE OUT 2, a sorta BLUE'S CLUES parody preschool character:

Astoundingly, the net's already big on this "Bloofy". There's already fan-art. Much in the same way Anxiety exploded upon the release of the film's teaser. I think Pixar's really, really got something here. I'm gonna be very curious to see how this does at the box office. Does it merely repeat INSIDE OUT's massive success? Or go even higher than that?

But yeah, you have this character being 2D, a FINAL FANTASY-esque PS2 graphics character... Some mixed media stuff, much like "Abstract Thought" in the first INSIDE OUT. It seems like director Kelsey Mann had this really wild idea for a sequel to a beloved Pixar movie, and the director of said beloved Pixar movie (and also head of Pixar) said yes to it. And that's what I'd love to see out of INSIDE OUT 2, a sequel that makes big swings instead of being the first film's greatest hits. That's how I felt about sequels like FINDING DORY, which I otherwise still quite liked.

Then you have Keanu Reeves voicing Shadow The Hedgehog in SONIC 3... Yep, it just writes itself, doesn't it? Gonna be a biggie this Christmas.

1 note

·

View note

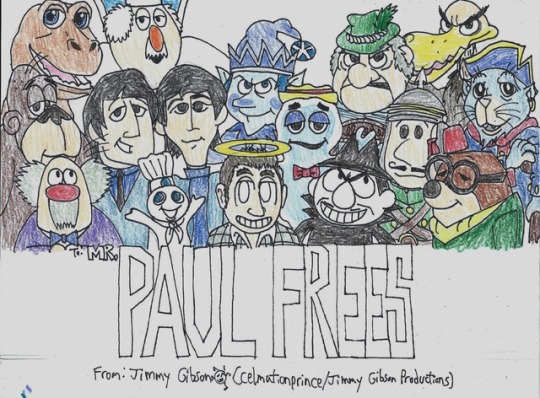

Photo

Still in the Habit of Making these, but Suggestions are Officially Closed, and I still have alot of other Art Ideas to come in Mind. Even for a late holiday entry, here is a Tribute to the Wonderful Mr. Paul Frees, who did Voices for many Rankin/Bass programs such as Burgermeister Meisterburger, Newsreel Announcer, Grimsby, Topper, & Additional Voices in 'Santa Claus is Comin' to Town', Jack Frost & the Traffic Cop in 'Frosty's Winter Wonderland', Aeon the Terrible, Santa Claus, General Ticker, Humpty Dumpty, & 1776 in 'Rudolph's Shiny New Year', and the Wayfarer in 'the Wind in the Willows'(his Final Rankin/Bass program to appear). But he was also the Voice of Boo Berry in the old General Mills' Monster Cereals ads, Arnie the Dinosaur in 'the Puppetoon Movie'(his Last Theatrical Film role, and a Film Dedicated to the Gentleman), the Narrator, Chief of State, Judges in The Pantry of Pomp, & Bailiff in 'Twice Upon a Time', the Pillsbury Doughboy in his old Pillsbury Ads & 'tPM', Boris, Inspector Fenwick, & Captain Peter “Wrongway” Peachfuzz in 'Rocky & Bullwinkle', John Lennon & George Harrison in the Cartoon 'Beatles', Ape, Weevil, Baron Otto Matic, & Various voices in 'George of the Jungle', and Squiddly Diddly, Morocco Mole, Double-Q, Yellow Pinkie, & Claude Hopper in 'the Atom Ant/Secret Squirrel show'.

Honorable Mentions:

Jerry Mouse in the Tom & Jerry short "Blue Cat Blues"

Ol Dreamy & the Raven in the 1959 dub of 'the Snow Queen'

Meowrice in 'Gay Purr-ee'

Dr. Hu in the English dub of 'King Kong Escapes'

Antiquity in 'the Flight of Dragons'

Mabruk in 'the Last Unicorn'

the Narrator in 'the Fantasy Film Worlds of George Pal'

Wally Walrus, Charlie, Doc, & Various voices in 'the Woody Woodpecker show'

Ali, Aaron's Father, The Three Wise Men, Meshaw, Jamilie, & Various other Male roles in 'the Little Drummer Boy'

Santa Claus, Traffic Cop, & the Ticket Man in 'Frosty the Snowman'

Santa Claus, Man at Thanksgiving Table, Colonel Bunny's assistant, Fireman, & Ben the Rooster in 'Here Comes Peter Cottontail'

Santa Claus, Zero, Spats in 'the First Easter Rabbit'

Bombur & Troll #1 in 'the Hobbit'

Olaf & Donkey Dealer in 'Nestor, the Long-Eared Christmas Donkey'

Jack Frost, Officer Kelly, Winterbolt, Genie of the Ice Scepter, & Keeper of the Cave of Lost Rejections in 'Rudolph & Frosty's Christmas in July'

Father Winter & Kubla Klaus in 'Jack Frost'

Elrond, Orc, Uruk-hai, & Goblin 'the Return of the King'

Ghost of Christmas Past & Present in 'the Stingiest Man in Town'

#Paul Frees#Voice Actor#tribute#drawing#my artwork#arnie the dinosaur#the Puppetoon Movie#ape#george of the jungle#chief of state#judge#twice upon a time#George Harrison#John Lennon#the beatles#Pillsbury Doughboy#jack frost#frosty's winter wonderland#boo berry#general mills#burgermeister meisterburger#grimsby#santa claus is comin to town#morocco mole#secret squirrel#boris#rocky and bullwinkle#wayfarer#the wind in the willows#rankin bass

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

George Pal: Puppet Master

George Pal: Puppet Master

A few months ago, I was laid up with a bad back and you know how when you’re unwell and immobile you’ll watch anything, because well you HAVE to? So I found myself watching Atlantis: The Lost Continent (1961), a giddy-making concoction of stock footage populated with a surreal bargain basement cast that included the Chief from Get Smart (Edward Platt), the Hekawi chief from F Troop (Frank De…

View On WordPress

#animation#director#fantasy#films#George Pal#movies#producer#puppetoons#Puppets#science fiction#special effects#stop motion

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

East German puppetoon movie, THE TRAIL LEADS TO THE SILVER LAKE (Die Spur führt zum Silbersee). 1990.

#stop motion#stopmotion#puppetoon#puppets#east germany#animation#animated#1990s#90s#western#films#movies

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 FACES OF DR LAO (Dir: George Pal, 1964).

George Pal first came to prominence in the 1930s with his series of animated Puppetoons shorts. Switching to live action, first as producer and then director he was responsible for a series of special effects heavy sci-fi and fantasy films, including The War of the Worlds (Byron Haskin, 1953) and The Time Machine (Pal, 1960) which are now rightly deemed classics of their genres. His 5th and final feature as directed was 1964’s 7 Faces of Dr Lao, based upon Charles G Finney’s 1935 novel The Circus of Dr Lao.

Tony Randall stars as the titular Lao, an aged (7322 years!) Chinese gent and owner of a fantastical, magical travelling circus. When the circus stops at the dusty Arizona town of Abalone the townsfolk are taught some valuable life lessons from the highly unconventional exhibits include the mythical soothsayer Apollonius, Merlin the Magician, Pan the God of Love and the fabled Gorgon Medusa. All of whom are portrayed by Randall in a truly mesmerising performance. Aided by some outstanding make-up from William Tuttle who rightly won the Academy Award for his efforts.

Some would rightly question the casting of white American Tony Randall as the Chinese Lao. Yet while the performance does exhibit elements of racial stereotyping it is not malicious. Right or wrong, such casting was perfectly acceptable in the era the movie was made and it would be unfair to castigate it for being out of step with more enlightened viewpoints more than 50 years after release.

7 Faces of Dr Lao is an unusual movie; mixing elements of the western genre with gently moralistic Bradbury-esq fantasy, it is probably fair to say it is a little bit of an acquired taste. If you are a fan of Pal then this movie needs no recommendation. For others, a philosophical fantasy aimed at family audiences might be a hard sell. However, it’s status as one of Pal’s lesser known features is entirely unwarranted. The excellent performances, top quality make-up and effects and feverish, almost surrealist atmosphere of the movie make for a heady mix. In my opinion 7 Faces of Dr Lao is one of the finest fantasies ever committed to celluloid.

Visit my blog: JINGLE BONES MOVIE TIME! Link below.

#7 faces of dr lao#george pal#tony randall#william tuttle#charles g finney#the circus of dr lao#puppetoons#the time machine#the war of the worlds#fantasy#fantasy movies#sci fi#sci fi movies#cult movies#ray bradbury#classic hollywood#vintage hollywood#movie review#movie reviews#jingle bones movie time blog#every movie i watch 2019

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953)

Theodore Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, remains best-known for his children’s books. The Cat in the Hat; Green Eggs and Ham; and Oh, the Places You’ll Go! are household names in English-language literature. Seuss’ bibliography overshadows his work in films, beginning with the adapted screenplay of his own book, The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1943) – directed by George Pal as part of the Puppetoons series. During WWII, Seuss was heavily involved in propaganda films and the Private Snafu (1943-1946) military training films. After the war’s end, Seuss returned to writing children’s books, but also continued to write for movies. The Academy Award-winning animated short film Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950) benefitted from Seuss’ story work, and Seuss’ success there inspired him to write a screenplay for a live-action fantasy film. That screenplay – the unwieldy rough draft coming in at over 1,200 pages – was The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. The eventual movie, produced by Stanley Kramer (1960’s Inherit the Wind, 1961’s Judgment at Nuremberg) and directed by Roy Rowland (1945’s Our Vines Have Tender Grapes, 1956’s Meet Me in Las Vegas) for Columbia Pictures, would be Seuss’ only involvement in a non-documentary feature film.

Like many who speak English as their first language, Dr. Seuss’ books graced my early childhood. So integral to numerous children’s youth is Seuss that his whimsy, wordplay, and authorial stamps are easily recognizable. In that spirit, the cinematic record of live-action Seuss adaptations consists of the scatological Jim Carrey in How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000) and the visual nightmare that is Mike Myers as The Cat in the Hat (2003). Compared to the original works, both films are ungainly, casually cruel, and overcomplicated. Not promising company for Dr. T. But even taking into account the three animated feature adaptations of Seuss – Horton Hears a Who! (2008), The Lorax (2012), and The Grinch (2018) – and the fact that Columbia forced wholesale deletions from the rough draft script of Dr. T to achieve a feasible runtime, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is arguably the most faithful feature adaptation to Dr. Seuss’ authorial intent and signature aesthetic.

In other words, this is one of the strangest films you may ever encounter. No synopsis I could write in one paragraph will ever capture the film’s bizarreries.

Little Bart Collins (Tommy Rettig) is asleep during piano practice and his teacher, Dr. Terwilliker (Hans Conried), is furious. His overworked, widowed mother Heloise (Mary Healey) intuits Terwilliker’s unrealistic expectations (Terwilliker wants to teach the next Paderewski) towards Bart’s piano skills and inability to concentrate. Heloise also appears to be quietly eyeing the plumber August Zabladowski (Peter Lind Hayes) and his wrench. With the lesson done for the day, Bart falls asleep again. This time, he dreams that Terwilliker is now the leader of the Terwilliker Institute, a pianist supremacy mini-state which is built upon five hundred young pianist slave boys (hence, 5,000 fingers) forcibly playing Terwilliker’s latest compositions. His mother is Terwilliker’s unwilling, hypnotized assistant and plumber August Zabladowski (Hayes is essentially playing the same character, but in a different world) is Bart’s only ally around. Together, Bart and Mr. Zabladowski must evade the Institute’s guards as they attempt to undermine Terwilliker’s plans for his next concert.

In its final form, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is a muddled mess of a story. The analogues between Bart’s reality and his dreams are inconsistent, several would-be subplots never resolve (or at the very least develop beyond a basic idea), and the film’s initial lightness is subject to rapid mood swings that make this picture feel disjointed. Indeed, Seuss’ sprawling social commentary in his first draft – including allegories and themes of post-WWII totalitarianism, anti-communism, and atomic annihilation – is in tatters in this final product. The viewer will witness brief fragments of those ideas, remaining in this movie as the barest of hints of the contents of the original screenplay’s rough draft. Even now, Dr. T inspires psychiatric analyses and accusations that Bart’s relationship with his mother reveals signs of an Oedipal complex (to yours truly, the latter is too much of a reach). The grim nature of Terwilliker Institute renders Dr. T unsuitable for the youngest children. For older children and adults, try going into this movie without expectations of narrative logic and embrace the grotesque aspects that only Seuss could imagine.

If my attempts to describe this movie’s preposterousness through its narrative and screenwriting approach have failed, perhaps I can capture that for you by writing on its technical features.

youtube

For its sheer narrative inventiveness – inconsistencies, abrupt tonal shifts, nonsense, and Rowland’s uninspired direction aside – The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is nevertheless an ambitious film, and Columbia bequeathed a hefty budget to match that ambition. Much of that budget went to the film’s visuals. This is an extravagantly-staged motion picture, as nothing could do Dr. Seuss’ illustrations justice without fully committing to his geometric impossibilities: skyward ladders and improbable connections between rooms, an eschewal of right angles and straight lines, and architecture bound to raise the ire of physics teachers. One could compare this to German Expressionism, but Dr. T’s sets tend not to dictate the film’s mood nor are they subject to high-contrast lighting. Seuss went uncredited as the concept artist on Dr. T, and it was up to Clem Beauchamp (1935’s The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, 1952’s High Noon) and the uncredited matte artists to commit those visuals to the real world. Outside of animated film, Beauchamp and the matte artists succeed in creating twisted sets that seem to leap off the pages of Seuss’ most artistically interesting books. Some of the sets appear too stagebound, but the production design accomplishes its need to resemble a world borne from a fever dream (or, at least, a young pianist’s nightmare).

This movie’s outrageous costume design (other than Jean Louis’ gowns for Mary Healey, the costume designer/s for this film are uncredited) comprises absurd uniforms and two of the most ludicrous hats – the “happy fingers” cap (see photo at the top of this write-up) and whatever the hell Terwilliker dons in the film’s climax – one might ever see in a film. Most of the costumes are laughably impractical and ridiculous to even those without fashion sense. In what might be the tamest example, while working under Terwilliker, Bart’s mother wears a suit that is all business formal on the left-hand side and bare-shouldered, sleeveless, and nightclub-y on the right. The delineation of real life – which barely features in the film’s eighty-nine minutes – and this world of Bart’s dreams could not be any more unambiguous thanks to the combination of the production and costume design work.

The disappointing musical score by Fredrich Hollaender (1930’s The Blue Angel, 1948’s A Foreign Affair) and song lyrics by Seuss rarely connects to the larger narrative unfolding. Seven songs make the final print, with nine (yikes!) Hollaender-Seuss songs ending up on the cutting room floor. Seuss’ wordplay is evident, as are Hollaender’s melodic flourishes. Columbia, a studio not known for its musicals, assembled a 98-piece orchestra – the largest musical ensemble to work on a Columbia film at the time – for The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T alone. That lush sound is apparent throughout for the numerous nonsense songs that color the score in addition to the incidental score. It is unusual to listen to a collection of novelty songs orchestrated so fully. Listen to “Dressing Song: Do-Mi-Do Duds” and its complicated, seeming unsingable lines:

Come on and dress me, dress me, dress me

In my peek-a-boo blouse

With the lovely inner lining made of Chesapeake mouse!

I want my polka-dotted dickie with the crinoline fringe

For I'm going doe-me-doe-ing on a doe-me-doe binge!

The rich orchestration seems to hail from a more lavish film. But too many of these songs are scene-specific, and rarely does Hollaender utilize musical quotations from these songs into his score. “Get Together Weather” is delightful, but it seems so isolated from the rest of the film; elsewhere, “The Dungeon Song” exemplifies a macabre side to Seuss seldom appearing in his books. Nevertheless, Hollaender is able to demonstrate his playfulness across the entire film, none moreso during any scene with the bearded, roller-skating twins and the “Dungeon Ballet”, in which the music complements stunning choreography and fascinating props that recall the jingtinglers, floofloovers, tartookas, whohoopers, slooslunkas, and whowonkas from the Christmas television special How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1966). Yet, Hollaender’s film score and the soundtrack with Seuss seems to demand something – anything – to tie the entire compositional effort together. Perhaps a song or some cue like that was cut from the film, which is ultimately to its detriment.

Hans Conried (who starred as Captain Hook in Disney’s Peter Pan several months prior to Dr. T’s release) stands out from a decidedly average Peter Lind Hayes and Mary Healey – Hayes and Healey, in a sort of in-joke, were married. Conried’s performance as the sadistic, torture- and imprisonment-happy music teacher can be considered camp, but this is anything but “bad” camp. He throws himself completely into this cartoonish role, sans shame, complete with mid-Atlantic accent, and topped off with exaggerated facial and physical acting that fits this fantasy. As Bart, child actor Tommy Rettig (best known as Jeff Miller on the CBS television series Lassie) seems more assured in his performance than most child performers his age during the 1950s. His fourth wall-breaking asides seem more appropriate in a Bugs Bunny cartoon, but Rettig makes it work, and inhabits Bart’s flaws wonderfully.

Columbia demanded numerous reworkings of Seuss’ script, leading to several reshoots – most notably the opening scene (Seuss opposed the conceit of Bart’s dream framing the film) – and a ballooning budget. Upon its release in the summer of 1953, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T bombed at the box office and was assailed by critics. A crestfallen Seuss, who could not stand the production difficulties that beset the film from the start of shooting, would never work in feature films again. He would dedicate himself almost entirely to writing and illustrating children’s books, with many of his most popular titles (including The Cat in the Hat, One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish, and Green Eggs and Ham) published within a decade of Dr. T’s critical and commercial failure. His hesitance to participate in filmmaking informed his reluctance to allow Chuck Jones to adapt How the Grinch Stole Christmas! thirteen years later. Animation suited his books, Seuss thought, and he would never again pay any consideration to live-action filmmaking.

The reevaluation of The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T has seen a rehabilitation of the film’s image in recent decades. Home media releases and television showings have introduced the film to viewers not influenced by the hyperbolic negativity of the film critics working in 1953. This is not a sterling example of Old Hollywood fantasy filmmaking, due to a heavily gutted screenplay, scattershot thematic development, and incongruent musical score. Yet, the movie’s surrealistic charms and Seussian chaos know no peers, even in the present day.

My rating: 7/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T#The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T.#Dr. Seuss#Roy Rowland#Peter Lind Hayes#Mary Healy#Hans Conried#Tommy Rettig#Allan Scott#Stanley Kramer#Frederick Hollander#Rudolph Sternad#Cary Odell#William Kiernan#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Puppetoons anon, that is so cool about the Clampett Tashlin stop motion thing, I didn’t know that. Speaking of unreleased Clampett projects, didn’t he try to make a rotoscoped John Carter of Mars movie? That would’ve been interesting

BINGO you got it!! he was actually going to make a series of animated cartoons based on the stories! chuck jones helped to animate (this is before their rivalry LOL) and bobe cannon in-betweened, who animated under both of them at warner’s! test footage finished in 1936 and clampett was about to give his notice to warner bros that he was heading to mgm to do the cartoons. unfortunately, because this was 1936, mgm sales reps thought it would be too asinine and difficult for the average viewer to understand why a man from earth was parading around on mars, and that it’d be a “tough sale”, so instead they pushed for a series of tarzan cartoons instead, seeing as tarzan was VERY popular around this time. so the project never made it. you can read more about it here!

and here’s some behind the scenes footage!

undefined

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tag 9 people you’d like to get to know better.

Tagged by: the delightful and enthusiastic @tbehartoo

Top 3 ships: Ohhhh. This is hard for my multi-shipper heart. Kataang (ATLA), Raylum (Dragon Prince), Melizabeth (Seven Deadly Sins) and Lukadrienette (OT3, Miraculous Ladybug). See. Even trying to narrow down to my top 3 resulted in four. And in MLB in particular, I have so many ship flames to fan.

Lipstick or chapstick: I avoid makeup, so we’ll go with the lip balm (usually Burt’s Bees).

Last song: The Wizard of Oz by Chen Yue (it was stuck in my head this morning)

Last movie: Klaus, the Netflix Christmas special that felt like it combined the Emperor’s New Groove and the Rankin and Bass Santa Claus in Comin’ to Town (stop action puppetoon). I also recently binged on season 2 of Avatar: The Last Airbender, which isn’t a movie, but it was a full day affair, so I’m counting it, too.

Reading: Pretty much any fanfic featuring Lukanette, Lukadrien, Kagaminette, any version of the love square, and any combination of Luka, Marinette, Adrien, and Kagami. Select ATLA stories by writers who got me into Tumblr and AO3 to begin with.

I’m also in the middle of many books because I’m a disorganized mess. I should try to wrap up a few of these in the next two days, and then hit the rest (as well as my ridiculous shelf of crap to read) for 2020. These include: Baguazhang: Theory and Applications, Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, Nothing Holy About It: Zen and the Art of Being Just Who You Are, Ranma 1/2 vol 3, Midnight Riot, The Art and Etiquette of Polyamory, The Titan’s Curse, and Agents, Adepts & Apprentices.

Tagging: This is a no pressure tag. While I’d love to get to know you more, I also get that time and privacy may be precious to some of you. @saijspellhart, @galahadwilder, @edendaphne, @ao3bronte, @raymiazaki, @jamiehascateyes, @hilzabub, @lnc2, & @alexseanchai

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellowface, You’ve Got The Cutest Li’l Yellowface…

Yellowface -- and its illegitimate cousins black-, brown-, and redface -- carts a long and dishonorable history.

Too often racial impersonation is at the service of racism: Minority actors simply rejected sight unseen by audiences and casting directors.

Occasionally it is a little less offensive; there’s at least an attempt to portray the minority character benignly.

Charlie Chan is the most notable example, with the four actors playing him in the sound era all being whites using tinted skin and eyefold appliances.

Chan was intended as a positive role model, and watched in that context the movies are not consciously insulting.

But in a wider context, casting against ethnic or racial type is fraught with danger.

On stage, where a multi-ethnic cast may play the Scots of MacBeth or the Thais of The King And I or the Ozark hillbillies of Li’l Abner, the sheer artifice of theatricality allows audiences to overlook casting against ethnicity.

Patrick Stewart famously played Othello against an all African-American supporting cast, and stage productions where multi-ethnic casts play biological family members are readily accepted.

But film and TV impersonations (with the exception of comedy skits that play towards theatrical tropes) are supposed to be real and convincing. Trying to pass off any performer as a different ethnicity, particularly a significantly different one physically, risks alienating a huge portion of one’s audience.

But…it can be done…if one earns it…and The 7 Faces Of Dr. Lao earns it.

It is not a universally loved film:

It’s corny and derivative and producer / director George Pal steers the production with an unsteady hand, but it also possesses heart and soul and more than a little philosophy that turns out to be surprisingly profound.

If you love it, you’re going to really love it. If you’re going to stub your toe on the clunky parts, there’s a lot of clunky parts for a lot of toes.

So, is Tony Randall’s turn as Dr. Lao + 6 other characters an acceptable case of cultural appropriation / ethnic impersonation or not?

Well, consider…

In the context of the story Dr. Lao is a quintessential Trickster come to a remote American West town to teach the good -- and not-so-good -- citizens a thing or two. As a Trickster, he employs a variety of methods to divert attention and deflect questions, including a grab bag of voices, accents, and dialects. He speaks most often in refined, flawless, unaccented English, but switches to sing-song “Chinee” pidgin when people start getting too inquisitive. Exactly who he is could be anyone’s guess since most of his cultural references are European and Greek while his few Asian references are dismissed as lies and fabrications. So for an Asian character to be portrayed by an Anglo-looking Jewish-American actor works in the story itself since Dr. Lao as a character is shown to be a fictional construct overlaying the real yet still hidden persona.

In the context of the film, Randall the actor plays a wide variety of human and non-human characters: Dr. Lao (presumably Asian, not necessarily human), Merlin (Anglo, human), Apollonius (Greek, human with disability), Pan (Greek, non-human), Medusa (Greek, non-human female), The Abominable Snowman (Asian, non-human), and the voice of The Great Serpent (Biblical, presumably Middle-Eastern, non-human). (Randall also appears in a one-shot cameo sans make-up as a spectator at Dr. Lao’s circus.) So the film sets itself up as the kind of movie where part of the deliberate artifice is that one actor will play multiple characters and actively invites the audience to search for him among the rest of the cast (the irony being that The Abominable Snowman in the film was played by a bodybuilder made up to look like Tony Randall wearing Snowman make-up; Randall only donned the make-up for publicity photos). From that perspective, Randall could have been replaced by any comparable actor of any ethnicity or gender and the end result would have been the same.

In the context of theme, transformation and illusion are crucial foundations upon which the story is built, with several characters loaning their appearance to others (including a sea monster that sprouts 6 extra heads, all of them characters Randall played). And this does not touch on transformations of heart and soul and mind and body that also take place, nor does it take into consideration that Dr. Lao never appears in the same shot with any of the other characters, suggesting all of them are really him (in fact, except for the Abominable Snowman pulling The Great Serpent’s cage in the parade and the aforementioned sea monster scene, none of the characters played by Randall appear together). The possibility that anything and everything is either malleable or an illusion permeates the film and calls into question whether Randall’s various performances themselves are self-referential to this theme.

The 7 Faces Of Dr. Lao is based on Charles G. Finney’s novel The Circus Of Dr. Lao and bears the same relationship to its source as the film L.A. Confidential shares with James Elroy’s novel (i.e., same theme, and several characters and plot points port over, but otherwise totally different).

The screenplay is credited to Charles Beaumont but how much he actually contributed is in doubt. Beaumont, a prolific short story and TV writer in the 1950s, suffered a severe physiological and cognitive decline in the early 1960s. Many of his post 1963 credits were actually written in part or in total by writer friends who wanted to ensure his wife and children received health care and residuals after his death.

Most of the script is probably the work of Ben Hecht, the incredibly prolific Chicago crime reporter turned novelist / playwright / movie producer. Hecht, well known for 1930s gangster films and screwball comedies, also possessed a taste for the fantastic and macabre (read his novel Fantazius Mallare for a sample of his imaginative writing). He died in 1964, shortly after The 7 Faces Of Dr. Lao’s release, but screenplays he’d written or worked on continued being produced for decades after that.

When work on the screenplay started is unclear. Hecht’s style seems more in tune with Finney’s than Beaumont’s, but Beaumont in his prime would have been an excellent choice as an adaptor.

The 7 Faces Of Dr. Lao addresses the issue of racial prejudice quite directly, and while all three writers involved are known for their firm stands in favor of racial equality, to me the final flourishes belong to Hecht. Early in the film one grizzled old Western character wonders if Dr. Lao is “a Jap” and is immediately corrected by one of his friends who correctly identifies Dr. Lao (or at least the clothes he is wearing) as Chinese. When asked how he knows this, the friend replies: “Because I ain’t stupid.”

Through out the film there are examples of racism and racial prejudices being confronted and confounded, and by the end even the chief antagonist has come to change his ways.

Producer / director George Pal holds a venerated place in the history of fantastic cinema, but his own career was dotted with racially problematic works. Pal, a Hungarian animator who brought his Puppetoon films to Hollywood, did not harbor the racial animosity of many white Americans, but his visual style was influenced by American stereotypes.

Pal made several short films featuring a character named Jasper, based on African-American culture as seen through white eyes. One can look at those films and tell Pal did not make them with malicious intent, but unintended stereotypes sting just as badly as deliberate ones.

To his credit, Pal responded to criticisms of the Jasper shorts by making John Henry and the Inky Poo, using more physiologically accurate puppets to depict the legendary African-American folk hero.

When Pal segued into live action feature films, he tended to avoid racial issues by avoiding racial minorities. Conquest Of Space featured a Japanese astronaut but When Worlds Collide shows only white people surviving the end of the world. The Naked Jungle’s white plantation owner browbeats native workers into fighting off a massive swarm of army ants, and Pal’s last film Doc Savage tried to recapture the feel of 1930s pulp adventures but unfortunately dredged up native stereotypes of that era as well.

Pal’s feature career is rather uneven:

When he made a good film it was really good, when he misfired it was a resounding dud. The 7 Faces Of Dr. Lao marks the beginning of the end of his active career. It faltered at the box office and while it shows he clearly wanted to move into more mature, more thoughtful films, his family friendly reputation trapped him. It took him four years to produce his next film, The Power, an edgy for the era sci-fi thriller, then seven years after that for his last movie, the remarkably unappealing Doc Savage, a kiddee matinee pastiche.

Back to the issue of racial impersonation.

As stated above, it’s very, very difficult to justify racial or ethnic impersonations today. The 7 Faces Of Dr. Lao is one of the extremely rare cases where it can be excused, if not justified, based on the particular (if not downright peculiar) elements of the story and the intent behind them.

© Buzz Dixon

#7 Faces Of Dr Lao#Tony Randall#Charles Beaumont#Ben Hecht#George Pal#Charles G. Finney#fantasy#media#ethics#morality#prejudice#racism#ethnic impersonations#yellowface#philosophy#things of the spirit

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Well poke me in the belly and make me giggle! It’s Day 28 of #mascotmarch2022, and today’s icon is #poppinfresh, the @pillsbury #Doughboy! Since the stop-motion sensation premiered in 1965, he’s appeared in commercials not only for #Pillsbury Products, but also for @geico, @gotmilk, & #sprint (now @tmobile), and even cameoed in the #puppetoon movie! He’s also been a pop culture inspiration, spawning characters like the #adipose from @bbcdoctorwho, #Baymax from @bighero6.disney, and (as I’ve shown here) @ghostbusters infamous #stapuftmarshmallowman! #illustration by @mirthquakecartoons and as always, the #mascotmarch #artchallenge is brought to you by @kimberlandart & @ichallengeyou2a_doodle https://www.instagram.com/p/CbpeaWLLXMD/?utm_medium=tumblr

#mascotmarch2022#poppinfresh#doughboy#pillsbury#sprint#puppetoon#adipose#baymax#stapuftmarshmallowman#illustration#mascotmarch#artchallenge

0 notes

Text

Why Clash Of The Titans Was The End Of An Era

https://ift.tt/3xChOFQ

It was 40 years ago, in June 1981, that Clash of the Titans, the last film to feature the stop-motion animation effects of Ray Harryhausen, was released.

Starring a then-unknown Harry Hamlin, along with veteran stars like Laurence Olivier, Maggie Smith, Burgess Meredith, and Ursula Andress, the film was loosely based on the Greek myth of Perseus (Hamlin), weaving in strands of other mythologies and legends and putting its hero into conflict with creatures like the Kraken, Calibos, Medusa the Gorgon and a two-headed dog named Dioskilos.

“Greek and Roman myths contained characters and fantastic creatures that were ideal for cinematic adventures,” wrote Harryhausen in his memoir, Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life. “If some of the adventures were combined with 20th century storytelling, a timeless narrative could be constructed that would appeal to both young and old.”

Harryhausen was already a filmmaking legend by the time he began work on Clash of the Titans. Born in Los Angeles on June 29, 1920, a 13-year-old Harryhausen’s life was changed when he saw King Kong for the first time in 1933. Inspired by the groundbreaking stop-motion animation work in that film by Willis O’Brien, Harryhausen began experimenting with his own short films employing the same process.

He got to meet O’Brien at one point, with the visual effects pioneer encouraging the young Harryhausen to keep refining and improving his work. Some years later, after attending USC, doing a stint in the military during World War II and working at his first professional job on George Pal’s Puppetoons, Harryhausen landed a job as O’Brien’s assistant on Mighty Joe Young (1949).

It was on 1953’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, the first film on which Harryhausen was in charge of the visual effects, that he created the process known as “Dynamation,” which allowed for greater and more realistic interaction between his stop-motion creatures and live actors.

In 1955, Harryhausen met producer Charles H. Schneer and formed a partnership that would begin with Harryhausen’s next feature, It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), and last all the way through their final collaboration on Clash of the Titans.

Their run of pictures included fantasy and sci-fi classics such as Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), Jason and the Argonauts (1963), One Million Years B.C.(1966), The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1974) and many others.

Unlike many visual effects artists even to this day, Harryhausen had an unusually high degree of creative control over his projects. He didn’t just animate the monsters; he was involved in the conceptual and story development, production design, and many other aspects, acting as a co-producer with Schneer and sometimes as a co-director — an agreement that any director of a Harryhausen film had to abide by.

Harryhausen even received co-producer credit on The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, a title he would also officially obtain on his and Schneer’s next and last two pictures, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) and Clash of the Titans. “I felt he deserved it,” Schneer told Starlog magazine (#152) in March 1990. “It was a recognition that Ray contributed more than just the special FX. His input was added from day one.”

Clash of the Titans was an idea that Harryhausen had been kicking around since the late 1950s, with screenwriter Beverley Cross (who wrote the final script for Titans) penning a treatment called Perseus and the Gorgon’s Head in 1969. Although the plans were delayed by the next two Sinbad pictures, work on the project began in earnest as Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger neared completion.

“The original legend of Perseus is complex and convoluted,” wrote Harryhausen in An Animated Life. “So we had to manipulate events, stealing from one legend and putting it in another.” Harryhausen cited the creation of the winged horse Pegasus as one example: in the original story, Pegasus is born from the blood of Medusa’s severed head. But since her death would come near the end of the film, a different scene involving Perseus capturing and training Pegasus was conceived to bring him in earlier.

With a screenplay and production storyboards ready, Schneer presented the film to Columbia Pictures, where he and Harryhausen had a number of successes over the years. But the studio balked at the $15 million budget — more than all Harryhausen and Schneer’s previous films combined — so Schneer next brought it to Orion Pictures.

MGM/Warner Bros.

That company had one request: cast a then obscure but up-and-coming bodybuilder-turned-actor named Arnold Schwarzenegger as Perseus. This time Schneer and Harryhausen balked. “I told them he didn’t fit the part, because it had dialogue,” Schneer told Starlog. “But Orion considered his casting to be a deal breaker. They refused to accept another actor, so I walked out on them.” Eventually, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer showed great enthusiasm for the project, providing the full budget and even a bit more.

Schneer, Harryhausen and director Desmond Davis — whom Schneer had hired because of his work with Shakespearean actors on several BBC productions of the Bard’s plays — looked at Malcolm McDowell, Michael York and Richard Chamberlain for Perseus before choosing Hamlin. “Harry had only made one picture, but had considerable stage experience,” wrote Harryhausen. “Not only was it felt that he would be able to handle the role and the effects, but he also looked the part.”

Hamlin told Starlog (#46) in May 1981 that he was initially reluctant to take the role, thinking it would be strictly a monster picture, until he saw the rest of the cast that was involved. But he was also drawn to the idea of playing a hero in the classical sense.

“I’m playing an across-the-board Greek hero type,” he explained. “Perseus has no superpowers himself. He has a few accoutrements, such as a sword and a helmet which makes him invisible. He has a magic shield. He’s a real hero in the classic sense. It’s a good role. I’ve always wanted to be a hero.”

Esteemed British actors like Olivier, Smith, Jack Gwillim, Claire Bloom and Sian Phillips embodied the constantly scheming, calculating gods Zeus, Thetis, Poseidon, Hera, and Cassiopeia, while Meredith — best known as the Penguin on the Batman TV series — was cast as the playwright Ammon. John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson and even Orson Welles were considered for Zeus until Olivier accepted the role.

“I told Ray that if he thought he was the star of our pictures, then I was going to upstage him once and for all,” Schneer jokingly told Starlog. “I was going to cast actors who were bigger names than he was, and whose work the world knew better than his. I wanted to see if he could survive.”

Read more

Movies

10 Forgotten Giant Monster Movies

By Marc Buxton

Movies

25 great stop-motion moments in live-action films

By Ryan Lambie

The movie begins with an infant Perseus and his mother Danae being sealed in a box and cast into the sea by Danae’s father, King Acrisius, who is enraged that the god Zeus (Olivier) impregnated Danae with the child. Perseus is rescued and grows to become a young man, while a furious Zeus orders from Olympus that the Kraken — last of the Titans — be released to destroy Acrisius and his kingdom.

Sometime later, the adult Perseus wants to win the hand of the beautiful Andromeda (Judi Bowker), who was once betrothed to a prince named Calibos. But Calibos (played by both actor Neil McCarthy and a stop-motion model) was turned into a monster by Zeus after the former offended the gods, and any prospective new husband for Andromeda must now answer a riddle concocted by the man-monster.

Andromeda is eventually offered to the Kraken as a sacrifice even after Perseus successfully answers the riddle. The only way for the giant sea creature to be defeated is for Perseus to voyage to the island of Medusa, sever her head, and use her eyes to turn the Kraken into stone — unless Perseus succumbs first.

Clash was shot at England’s Pinewood Studios, with location filming in Spain, Malta, and southern Italy. Principal photography began in May 1979 and concluded in September of the same year. Harryhausen then began the arduous, 18-month process of creating all the Dynarama effects (Dynamation had been renamed) and animating all the film’s creatures, from Calibos to the Kraken to the eerie Medusa to the mechanical owl Bubo, which Harryhausen said was not a riff on R2-D2 from Star Wars.

To complete the post-production work in time for the film’s June 1981 release, Harryhausen — who usually worked completely alone — brought in additional animators Steve Archer and Jim Danforth.

MGM/Warner Bros.

“I enjoy working by myself,” Harryhausen said in Starlog #127 (February 1988). “I did all but one of my films entirely on my own. Clash of the Titans was the only picture on which I had assistants for the animation. I always liked to put my mark on the work because that’s the final imprint you see on the screen. I felt a personal attachment to my films.”

But Harryhausen admitted that the grueling work of sitting alone in a studio, doing the frame-by-frame movements and shots that are at the core of stop-motion animation, began getting to him as he raced to finish his work in January 1981.

“It is always a frame-by-frame process which takes time,” he told Fangoria magazine in June of that year. “One of the greatest problems in this field is that after everyone’s forgotten the picture you have to go on keeping excited and interested in what you are doing in order to go on for another year. Sometimes it gets a bit dismal but I survive.”

The film did meet its release date as MGM’s major release for the summer of 1981. Released on the same date as Raiders of the Lost Ark, it came in second to that film with a first weekend gross of $6.5 million. It finished 19th for the year at the domestic box office with total earnings of $30 million. Although some reports had it earning a total of $70 million worldwide, it actually topped out at $44.4 million — still a sizable hit against its $15 million budget and the equivalent of nearly $99 million today.

Critics and fans were mixed on the film, with the former giving it a 67% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes and the latter awarding it a slightly better 70% score. While Roger Ebert called it a “grand and glorious romantic adventure, giving it three-and-a-half out of four stars, Variety absolutely buried the film, calling it an “unbearable bore” and targeting Harryhausen’s “endless array of flat, outdated special effects.”

For Harryhausen, the Variety slam in particular seemed to flip a switch inside him. “When I came to read the Variety review…I became very disillusioned,” he wrote in An Animated Life. “I gave the film so much of myself that when it was vindictively and unconstructively torn apart, the passion of filmmaking seemed to die.”

Schneer told Starlog that he sensed a change in his longtime friend and partner after Clash was completed. “It was a gradual process,” he said. “It didn’t happen overnight. I saw it coming at the end of Clash. I could see that Ray was getting older….the trial of making a picture is so draining, that I don’t blame him for backing away from it.”

While Harryhausen’s work in the field of fantasy filmmaking is unparalleled in its imagination and influence — everyone from George Lucas to James Cameron to Guillermo Del Toro has cited the man’s work as an inspiration — it’s clear that Clash of the Titans did indeed mark the end of an era. The effects look dated now, which could certainly be expected 40 years later; but at the time of the movie’s release, the previous five years alone had seen a massive upheaval in cinematic visual effects.

Star Wars, Superman, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Alien and The Empire Strikes Back had all come out in the years immediately before Clash, with all of those movies revolutionizing the way in which visual effects were achieved to one degree or another.

The incredible new techniques used to create epic space battles, detailed and awe-inspiring starships and lifelike monsters and extra-terrestrials all left Harryhausen’s painstakingly handcrafted and impressive — if now undeniably quaint — methods in the dust (although stop-motion was still deployed in small doses in several films, most notably The Empire Strikes Back).

Computers were already being used to create the dazzling space dogfights shots in movies like Star Wars, and even more groundbreaking use of computers — the CG revolution — was on the way, with Tron giving the first glimpse of what was to come just a year after Clash of the Titans came out (Clash itself was remade in 2010, using many of the techniques fashioned in the last 30 years with disappointing results).

Harryhausen himself seemed to recognize what was coming. Although he and Schneer began preparing two more films — Sinbad Goes to Mars and Force of the Trojans — neither project got the necessary backing and Harryhausen decided to quit while he was ahead. “The decision to end my career at that point was absolutely right,” he recalled in An Animated Life. “I was forced to concede that it was time to stand aside for others and their new technology to take over.”

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

For movie lovers and fantasy fans of a certain age, Clash of the Titans was their first exposure not just to the work of Ray Harryhausen (who died on May 7, 2013, at the age of 92), but to the magic of fantasy storytelling, the wonders of stop-motion animation and the resonance of Greek mythology.

All of Harryhausen’s films provided that kind of entertainment and enlightenment to different generations, and were the link between the work of Willis O’Brien on King Kong and the trailblazing era of effects defined by companies like Industrial Light and Magic, Digital Domain and Weta. Progress is necessary and change is inevitable; yet Clash of the Titans brought down the curtain on a career and a style of filmmaking that may be behind us, but will live on in the imaginations of all they touched.

The post Why Clash Of The Titans Was The End Of An Era appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3wI6Azp

0 notes

Link

0 notes