#These two identities of hers would have undoubtedly overlapped but that's the point - they overlapped

Text

"A developed affinity certainly furthered the queen’s own political position, but the institutional ties between the king and the queen’s households enabled the queen to remain an important influence in the political arena. Furthermore, the extension of the queen’s influence and holdings did not solely benefit the queen. Rosemary Horrox has argued that Elizabeth Woodville’s networks and influence across East Anglia were so extensive that her dominance there was considered the main source of royal authority in the region. Moreover, Joanna Laynesmith has identified that when the queen was successful in administering her estates, she ultimately facilitated the king’s own administration in creating a vast spread of royal influence."

-Katia Wright, "A Dower for Life: Understanding the Dowers of England's Medieval Queens", Later Plantagenet and Wars of the Roses Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty

#historicwomendaily#elizabeth woodville#my post#It's nice to see an analysis of EW as a queen whose successful administration facilitated and strengthened royal authority as a whole#rather than merely 'a Woodville' promoting her family#These two identities of hers would have undoubtedly overlapped but that's the point - they overlapped#They weren't distinct or separate from each other because the Woodvilles were ultimately 'part of the royal connection'#Of course at the same time it would be incorrect to ignore the novelty of EW's natal family's presence and effect on her queenship/#administration/patronage - which set the precedent for all future English queens.#(EW also had major interest in the Exeter lands - you can tell by her marriage maneuvers for her eldest son and eldest grandson)#(In 1469 she herself was placed fourth in line to those lands; in 1476 she received an additional annuity from its fee-farms; etc)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genesis of a Genre: Part 1

Defining the four key archetypes of Magical Girl characters found in Japanese Magical Girl media.

I feel this wouldn’t be a great body of research without outlining some kind of historical context for the media were talking about! In this mini-series of essays I’ll be going over the first part of my research, which seeks to define the key influences of the Magical Genre, including industry and production influences, and provide an outline for reoccurring archetypes and conventions found in the narratives. This focuses mainly on Japanese Media, but I might do one about the history of western Magical Girl stuff too!

I pose there are four key archetypes for the protagonist (and sometimes supporting characters) of any Magical Girl franchise: The Witch, The Princess, The Warrior and the Idol. Any given Magical Girl may be one or a combination of several; for example Usagi (Sailor Moon) is a combination of the Warrior and Princess while Akko (Little Witch Academia) is the Witch.

Girl Witches and Growing up

Many writer have cited the Witch as the first true Magical Girl Archetype; Sally the Witch and Magical Akko-chan are often regarded as the progenitors of the Genre. Both were published in the notable shoujo magazine Ribon in the 60’s and both were adapted into anime by Toei; Ribon notably also published several of Arina Tenemura’s works, including the Magical girl series Full Moon while Toei is the studio behind Sailor Moon’s anime in the 90’s, as well as creating both the Ojamo Doremi and Pretty Cure franchises in the late 90’s and 2000’s respectively. Sally was influenced by the popular American sit-com Bewitched, but reimagined to focus on an adolescent girl-witch who must keep her identity secret. She was often alone in her quest too, perhaps with a magical pet confidant, unlike future entries where Magical Girls would be a part of a team or have complex relationships to others with powers. There were ideas of destinies or even secret royal birth-rights, but ultimately the protagonist was simply a girl, who was born with magical powers.

These early entries set off the precedent for Magical Girl as a genre being inherently linked to themes of coming of age; the magic of the young characters often being allegorical for childhood innocence and ultimately being abandoned or given up as a part of their growing up. It’s notable at this point in the genre, very few or no women worked in these spaces; both Sally and Akko are written by men. I wonder how the genre may have been different if it was not the case; could these young girls be allowed to grow up magical if a woman wrote their stories? I feel this is a reoccurring theme in so many future works, so stick a pin in that.

In the contemporary sense, while Magical Witches aren’t quite as frequent as they were in at the start of the genre, there are still several shows that carry on the tradition. Ojamo Doremi, while borrowing several features from later warrior/sentai styled shows like Sailor Moon, has the lead characters as girl witches again. Madoka, though stylistically more a Warrior styled show, also alludes to the history of magical girl as a genre with the naming of it’s initial antagonistic characters being “witches” while the leads are “puella magi” or literally maiden witches, though the way it explores these themes is a conversation for another essay. Lastly, Little Witch Academia is the most recent notable example of the pure Magical Girl Witch. The franchise is like a true homecoming for the genre; I could wax on about how it’s a culmination of everything the genre’s gone through in the last 60 years. From it’s allusions to flashy transformation sequences, to it’s shift in focus to friendships between girls, Little Witch Academia is an absolute treat; it’s main character being named Akko undoubtedly a homage to her ancestor of the same name.

Idol Aspirations

As the genre progressed, women were…allowed into the magazine offices. The genre was reinvigorated in the 70’s, and with these new author came a shift in focus. Stories began to take more elements from Shoujo staples, with more focus given to interpersonal relationships and aspirations of the characters coming into place.

The Magical Idol singer is this weird niche specific thing that sort of came from this period of time, though I think she signifies more than her actual appearances across the genre. Authors for the first time wanted to create stories that reflected the goals of its readers- and at the time that meant Idol culture and aspirations of being a singer or celebrity. While contemporary examples of a by-the-book idol character is a bit rare since values have changed over time, she was the first step in magical powers for Magical Girls no longer being a part of a divine destiny or something to grow out of but instead powers being the means for Girls to achieve their goals. Magical Idol singers also often incorporate the characters noticeably aging up when turning into their alter egos, serving a duel purpose of giving younger viewers a sort of aspirational character to live through while also unfortunately allowing the animators to get away with fan servicey shots of the more mature looking character.

The originator of this subgenre would be Magical Angel Creamy Mami, though Mermaid Melody would be an immediate example I’d personally think of for the Idol type character (with a big old additon of the Princess archetype too), a better example would be the aforementioned Full Moon, in which the sickly Mitsuki transforms into a Magical Idol singer to both live her dreams as a singer and to reunite with her childhood love. I’d also argue that series the Utena and Madoka follow along with this influence; in both cases the characters agree to engage with the magic of their worlds to achieve some kind of goal or dream. Still, I feel there’s lots of potential with this kind of outlook in Magical Girl stuff..!! Perhaps in the future we’ll get more magical girls focused on their careers…

Warrior Princesses

I feel throughout this essay, I’ve been noting how the Warrior and Princess archetype often overlap with the other genres, as well as each other. I believe this is because the ancestor of these two defined archetypes is one and the same, and also the series I believe that actually started magical girl as a genre; that being, Osamu Tezuka’s Princess Knight.

Princess Knight, and bare with me on this, is a story about a Princess born with both a “girl” and a “boy” heart. She forsakes her life as a princess to escape some cruel fate that’s in store for her, and masquerades as a prince by using her “boy” heart. While this is an extremely dated view on gender, it immediately gives us three defining features of magical girl as a genre: First, the Princess archetype, which often holds influence from european fairytales and magical destinies; Second, the Warrior Archetype, in which the lead character must don a more traditionally masculine role of protector against some evil power, and lead a double life; and lastly, the introduction of gender roles as a theme into the genre, and the role of femininity and masculinity in the identities of our characters.

All of these tenets are then repeated in both Sailor Moon and Utena decades later, and it’s arguably these two series that carry it forward to influence future franchises. As the major examples of these archetypes are one and the same, it is difficult to parse the two apart, even though they are quite different.

So I’ll try anyway!

I believe the Magical Warrior is defined as a main character or team of characters who are joined by a destiny to fight against some greater evil, while the Magical Princess is defined as a character who is destined to inherit or reclaim a great power linked to a monarchical structure. Both may have themes linked to western fairytales and fantasy, though often Warrior type characters have a wider breadth of influences while Princesses remain closely linked with ideas of fantasy and fairytale royalty.

While Magical Warrior is definitely the most prolific of the archetypes in modern times, arguably overlapping with nearly every storyline, I think Magical Princesses are fewer. For example, Tokyo Mew Mew is a clear cut Magical Warrior story; they girl’s aren’t born with powers (So not witches), they aren’t doing it for a personal goal (so not Idols) and none of them have some divine destiny (not princesses). However it’s a lot more difficult to find a pure Magical Princess story; in Mermaid Melody, but the story overlaps with both Warrior and Idol archetypes. Princess Tutu might be the best example, as it’s a story of retribution deeply linked with elements from european fantasy.

#magical girl#sailor moon#tokyo mew mew#full moon wo sagashite#revolutionary girl utena#pretty cure#little witch academia#mermaid melody#essay#context#princess tutu#princess knight#ojamo doremi#puella magi madoka magica

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

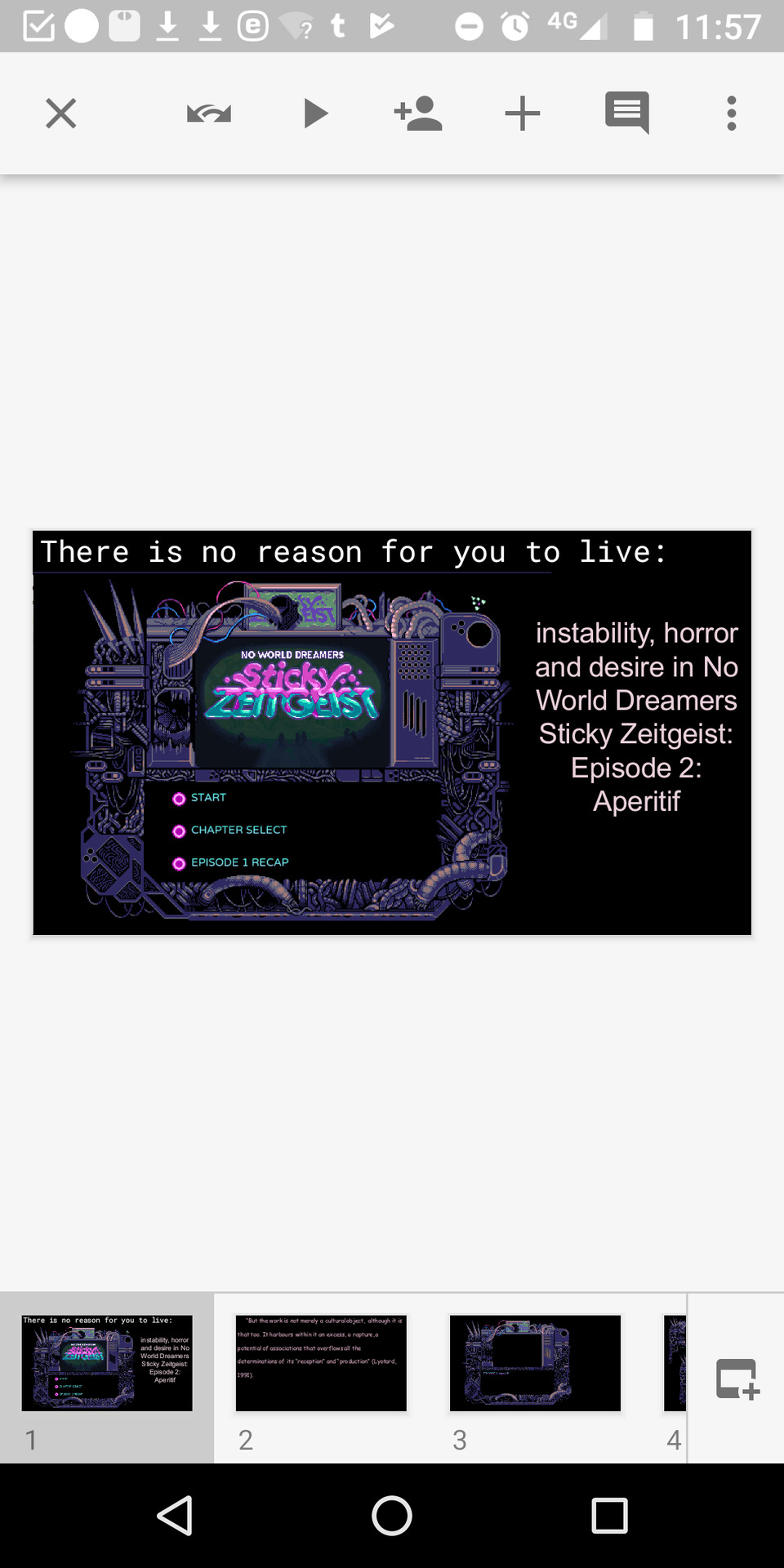

The Three Hidden Conversations

When I say "theories" I mean "established methods" more often than "hypotheses", so when I want to translate it in that sense, I have a bit of a problem.

Well, that doesn't matter, but there's something I want to confirm about Levi and Historia.

Somehow Isayama cleverly hides the fact that there is a conversation between the two of them and that they have probably become quite close to each other.

Levi and Historia are having a close conversation without the reader being able to see it. There are at least three scenes in which this can be seen.

(1)

One of those scenes, of course, is the Hood scene.

There's no doubt in my mind that the Hood is Levi, as I've proven. The two silhouettes overlap perfectly.

So why does Isayama have to make Levi an enigma like that? It's natural for the two of them to talk in the orphanage. The orphanage was built by the two of them, and Historia is a soldier of the Survey Corps while being a queen.

But Isayama hid the fact that Historia was talking to Levi before she spoke to the Farmer, hiding Levi's entire existence.

Even if the talk related to the succession, he has already expressed his opinion in the Giant Tree Forest in favor of turning Historia a titans. (Although he does preface it with "if Historia is ready.")

Since that has already been portrayed, the scene in the Hood is not about whether or not to turn Historia into a titans.

In Chapter 131, we find out that the pregnancy was something Historia had mentioned. So the person in the Hood didn't encourage Historia to get pregnant, as Rogue says he did.

Is there any topic between them that needs to be hidden, other than talk about the titans?

There's something about it. It's hidden.

Anyway, Levi and Historia are having a conversation here that is so important that it has to be hidden.

(2)

Levi is not at the meeting with Kiyomi. He's at the venue, but he somehow disappears. And his unnatural absence from the middle of the meeting is not mentioned. No one explains or mentions where Levi has gone after he's gone.

The last time we see Levi during the meeting is in the panel where Eren says that Mikasa was only showing Eren a tattoo that Mikasa was not supposed to show to others.

(The reader can see here that Mikasa has been intending to marry and have children with Eren since she was a child, that is, Mikasa's feelings for Eren are of the kind that she "I want to be his wife."

It's worth noting that Levi and Historia are in that panel)

It's the panel that should be Mikasa that is worth noting here, even with the expression on Historia's face. Nonetheless, Levi is looking at Historia, not Mikasa. At such a close distance that their bodies are touching each other.

Yes, the distance between them is very close. If they had walked together at that distance, they would have come while talking about something. Unless Levi was a pervert who preferred to walk in silence while sticking to the young girl's back.

But there's no scene of Historia and Levi talking to each other itself.

And if the reader doesn't pay careful attention to this panel, we may recognize that Levi and Historia are together, but we don't realize that they would have had any conversation before then.

Levi and Historia walked at this distance talking.

At this point, Levi and Historia have become very good close. It's more than their titles.

(3)

Right after the Survey Corps returns to Paradis from Male and before he and Zeke go to the Giant Tree Forest, Levi goes to meet Historia.

This is because even though the Survey Corps was supposed to be hiding out in Male for months, the size of Historia's belly that Levi imagines in Chapter 112 is the exact size of Historia's belly today. And, politely, it's the same figure and angle as it is sitting in the chair in Chapter 107.

Regardless of how many months the Survey Corps has been in Male, the size of Historia's belly will undoubtedly be different than it was when he saw it before he went to Male. I don't think Levi can imagine exactly how big a pregnant woman's belly is in months. It's natural to assume that that image is what he actually saw.

We can infer from Armin's line that the day of Sasha's funeral was not the day of their return. When Levi and Zeke are riding in the carriage, the time to spread the news of the "Victory" to the people of the island has passed.

There is plenty of time for him to go see her. In the meantime, Zeke can be safely held in the basement.

But this too is never mentioned. Because of the clever scene development, the reader goes through the reasons why Levi is able to imagine exactly what Historia is like.

Even I, who always think about Historia and Levi, have only recently noticed how odd it is that Levi can accurately imagine the size of Historia's belly.

Levi and Historia are meeting and talking.

There are at least three scenes where that is camouflaged so that the reader doesn't know that they are reading normally.

Well.

Isayama puts up foreshadowing in a way that is not immediately obvious as foreshadowing. And he likes to stage the scene so that it becomes clear later on that the description was foreshadowing.

This hidden conversation between the two will eventually be revealed. At the very least, the Hood's identity as Levi will definitely be revealed.

I predict it will be in Chapter 134.

If Historia is indeed pregnant, her partner is definitely Levi.

RivaHisu shippers, please pray for me to win😉

#snk#aot#attack on titan#shingeki no kyojin#historia#levi ackerman#levi#rivahisu#historia reiss#levi x historia

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

potentially upsetting topics: sui, gender dysphoria, abuse and parents, sex

Elliot Page’s coming out rescued an awful day. Its wording is unbelievably powerful, a comment I have made once before and will continue to do so. In it, he so strongly encompasses the fears, the sorrow, the rage, but most importantly the determination and the defiance of not only him but every trans person. I hesitate to use the word “community” because it implies a certain connection that might just not be there; I play a bit of Counter-Strike but I don’t consider myself part of the Counter-Strike community; yet when I read Elliot’s words I feel solidarity, I feel a pull to the trans community that I often don’t feel I pay my dues to, and it feels good, really good. Like I said on Twitter once, other trans people being, existing, living, is just rad. Inspiring, even, despite how that word has been worn out by cis people.

However, there’s a certain something that Elliot didn’t write, for Elliot never wrote “I am a man”; only his name, and pronouns, how he wishes to be referred to. Of course, we cannot possibly know what this omission means or does not mean to Elliot, but it’s something that concurred with a shift in how I perceive my own gender.

I remember first properly ruminating on gender in 2012 or 2013. My understanding was primitive, coming from Wikipedia. Once I knew what transgender or, given the time period, transsexual, the curiosity never really went away. I knew at this point about transition, and I knew about deed polls because of my resentment of my parents, I knew about HRT and I even knew about the GICs. I felt compelled to be an ally in that turbulent period in both my life and in the online culture I immersed myself in from around 2015 to 2017. At this time a friend was going through their own transition and seeing them gave me pause for thought; partly pride, partly worry but a small kernel of imagination, wondering if that could ever be me. It was when I went to sixth form, with its environment permitting greater yet still constrained self expression, that I felt gender dysphoria hit me with its full weight. Thinking, wondering, worrying about being transgender has been the central dialogue of my internal and external monologue ever since. Not a day passes where I don’t think about the dysphoria I feel over my continued closet-dwelling and the malignantly gendered properties of my body. On a January morning in 2019, at my very lowest point, motionless under the covers, I gave myself a choice between transition and death, and I chose transition.

It’s been a complex journey. When I was 13 I shortened my gender neutral name to make it more masc (which I have now happily embraced as my middle name). I leant into the deepening of my voice because I thought it gave me authority, conditioned through the harsh words of people from public Team Fortress 2 servers. I’ve done almost everything under the sun that gets people to say “I’d never have known!” when you come out to them; I worry that I still do and that nothing has changed. I’ve gone and cross-dressed when my parents were out, and I’ve been traumatised by Susan’s Place. I am autistic, no one who has met me can escape that fact; not that I would want to, and as a consequence I am so much more confident in my presence on the internet than I ever have been in the flesh, despite me still not knowing how to make friends; hence I’ve ended up trying to piece my transition together through 4chan (I know, bad) and Reddit and Twitter.

Perhaps the biggest reason I am not out is the time when I decided I would come out to my mother as trans. When we were in Munich we had walked past a pride parade, and when we got back to the apartment I revealed off hand that I was bi. My mother chided me for not telling them before hand since it was “polite” to do so, as if it were not my choice to make because, as I still believe to this day, it’s not a big deal and it’s none of their business. But I decided this time it was important, and that I could trust her. It turns out that just like every other time, trusting my mother is a bad idea that is guaranteed to cause me pain every time I make that mistake. She told me that because she “knows more about [me] than [I] do”, that she thought that I was just straight up wrong, couched it in rhetoric about how she thought that I was too weak to be trans, and quoted the shockingly offensive “autism is extreme male brain” theory to me. It was really devastating at the time and I think it still affects me to this day, especially as she constantly tries to worm her tendrils back into my life after I moved out.

But enough about my mother; she is a fucking flat out abuser. She has emotionally abused me, and undoubtedly my brother, all our lives. I was relieved that my dad chose not to react aggressively as she did, but with a modicum of respect and agreement not to make such a big deal out of it, something I would never expect my mother to match. In the middle of writing this piece I had to decide that I could not do it any longer, and I would never let her back into my life again.

Where that conversation in late 2018 relates to Elliot Page’s statement is my mother’s purported belief that “you don’t have to define yourself as a man or a woman”. Going past the fact that she is lying, since her tolerance for all trans people is thinner than the grey hairs on her head going on the basis that she couldn’t bring herself to say one positive thing to her own daughter that afternoon, it struck me recently that I can more eloquently describe my gender through elimination rather than a label. I am happy to call myself a woman, a trans woman, and I don’t feel as if I really am wavering in or around the binary. But what I can say for definite is that while I have been a boy for almost all my life, and am holding onto that, I am not, and never will be, a man.

Where that leaves me is that I am not a man, but must I be a woman? If I am perhaps not a woman, am I non-binary? No; it doesn’t feel right. However, if I attach just a convenience to the label woman, I can give myself that flexibility in how I feel and how I present myself, and perhaps the biggest example of that is how in recent months I have made peace with my voice. It is not really a femme voice; I hit vocal fry just speaking normally. But I know how to be expressive with it; it is my voice that I have honed over 19 years after all. One day I want to find someone who will help me upgrade my voice (and yes, upgrade) but keeping it means I fulfil one cool thing about being trans, and that is saying fuck you to the very existence of the gender binary. I keep this voice out of necessity, but I’m still trans femme, I am still a woman and I still want my facial hair zapped off.

As well, I reserve the right to say I used to be a boy. Not a man, but a boy. That’s why they call it boymoding, right? How else can I describe the first 17 years of my life? I can be a boy all the same now, although I may be pushing it aged 20, and at the point at which I am really stretching that concept which at this point I am adhering to solely for my safety and comfort, I shouldn’t need to use it anymore. Wishful thinking, of course.

I think we should consider why we use “man” and “woman” in the first place. From my perspective they are simply words to describe people with two different sets of primary and secondary sexual characteristics, convenient because, well, being cis is unavoidably common. But they are not discrete, as we so often have to reiterate using intersex people as an unwilling crutch, where one does not occur in the other they are so often analogous and often they overlap! Supposedly 60% of teenage boys develop further breast tissue, and 40% of women have some form of facial hair. Thinking that the two are discrete gives rise to the idea of “biological sex”, a concept developed by cis people either to misgender trans people in a way they think is philosophically rigorous, or to reconcile their tenuous support for trans people with a continuing belief in the gender binary. Personally I would like to smash the concept of biological sex to bits because it is not useful to us. At the very least it may describe one’s primary sexual characteristics but bottom surgery exists, and I don’t happen to think that it is “mutilation”. I don’t need to argue that “biological sex can be changed”; they are not discrete categories, and I don’t need to move between them, or seek validation for having moved between them. It is not a helpful generalisation for bodies, diverse as they are.

I must add that as a trans woman the fact that I may have a penis doesn’t mean that I use it in the same way as a man. I use mine to pee, primarily, and it’s definitely not going inside anyone except myself any time soon; a whole zine was written about how trans women fuck and use their bits to fuck, so I definitely don’t need to anyway.

Another bullshit concept is “biological destiny” or “biological reality”, although I will give less breath to this one because at it’s core it is fundamentally misogynistic, and it so often is divorced from any sensible definition of reality. It’s like if I had to have my arm amputated and then someone came up to me and said “you’ll always have two arms, you were born with them and you’ll die with them”.

I’ve heard and thought a lot about gender abolition but it seems to me that its proponents expect that like the state, gendered differences will just disappear over time. But I don’t want that to happen. If the binary is done away with I don’t want gender to disappear I want it to flourish! Because gender is beautiful, men are beautiful, women are beautiful, and everyone in between or outwith are beautiful. On the other hand, me and you don’t need to be men, or women, or call ourselves non-binary to be beautiful. Being trans is about cultivating your own beauty and your own identity. When cissiety demands that the only identity and presentation we’re allowed is one that corresponds to what they decided was between our legs when we were born, why give ourselves only one other choice?

I don’t really know how to end this piece because I wrote one half of it one day and the other half a couple of weeks later. At the very least I’m glad I can attribute my peace with not necessarily being a woman but a femme to Elliot Page, and not my rotten bastard mother.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gravity, chapter 1 (Mirandy)

Andy Sachs was not a scientist.

She felt that this was an important point to make, particularly in the weekly staff meetings, when the scientific editors’ discussion of the latest endosymbiont or cytokine or whatever devolved into semi-hysterical PubMed searches and emphatic data-set thumping. Eventually, after they’d worn themselves out squawking at each other, they’d turn to her to tie-break.

“Guys,” she’d say. “I am not a scientist.”

But she was the managing editor, and despite having a pay grade significantly below that of the Ph.D.s in the room, it somehow fell to her to figure out which of the six nearly-identical Figure 1s to use.

“Your problem is you’re too capable,” Trixie said, examining the underside of her coffee mug with an expression that was half interest and half revulsion.

“You say that like it’s a bad thing.” Andy closed her laptop and scrubbed both hands over her aching eyeballs. “Are you ready to go?”

“What do you suppose this is?” Trixie held the mug out to Andy, bottom-side first, where a wad of something grayish-blue was firmly affixed.

Andy made a face. “Walt’s gum,” she said.

Trixie shuddered. “I was afraid you’d say that,” she said. She reached over and put the mug onto Walt’s desk. “That dude is a sociopath. I can’t believe I dated him.”

“Stop.” Andy let Trixie pull her to her feet. “I can’t handle any romantic navel-gazing tonight. I need ravioli.”

They stopped at Trattoria Giulia on the way home, stomping their feet on the cracked sidewalk in a vain defense against the icy night wind as they waited at the window.

“Whoever thought a spaghetti counter was a good idea—” Trixie started.

“Was a genius,” Andy finished, tearing into her bag and finding a breadstick. She crammed half of it into her mouth while they walked the rest of the way home.

“SVU?” Trixie asked, once they were ensconced in their apartment.

“Nyet,” Andy said, finding a spoon in the pile of dirty dishes in the sink and wiping it on a dish towel. “Too tired. Going to eat ravioli in bed and pass out.”

Trixie flopped on the couch. “Suit yourself.”

Andy managed to splatter minimal tomato sauce on the bedspread, which was pretty good for ten o’clock at night, she thought. She scrolled through emails as she chewed. Submission, submission, submission, submission. The journal was pretty successful, even though its impact factor would never break the threes. And she liked her job. It wasn’t the hard-hitting journalism career she’d envisioned when she’d graduated from college, but it was good, satisfying work.

It was a little funny, actually, that she’d taken such a roundabout route to end up right back in New York. It had started with a little job in Boston—editing press releases for a medical journal—and when she and Nate had ended it a year later, she’d moved back to Ohio. A colleague from the Boston journal had put a good word in for her in Cincinnati. Eighteen months after she’d started, the whole publication had moved to Queens, and they’d taken her with them. Trixie’s claim that she was too capable had served her pretty well, all things considered, and she’d been promoted to managing editor just before her thirty-first birthday.

Submission, submission, submission. All things that could be handled at the office tomorrow. She scrolled faster.

And then she saw a name.

Andy’s thumb slammed on her phone screen so hard she accidentally minimized her mail app. “Fuck,” she muttered, opening it again, and there it was, in bold Helvetica Neue.

Every cell in Andy’s body seemed to turn to ice.

EXTERNAL, the email said. Submission.

And the name above it:

Cassidy Priestly.

***

They’d be twenty-two now. It was hard to fathom—her brain had put them into a kind of temporal lock, freezing them eternally as bratty twelve-year-olds. She’d spent more time than she cared to admit Googling Miranda, but she had sort of forgotten about the twins.

Cassidy didn’t have a LinkedIn, but Caroline did. She was following in her mother’s footsteps, apparently—her current position was listed as Photography Intern, Elias-Clark. She looked like a younger, freckled Miranda, all cheekbones and chin and that aquiline nose. Heavy eyeliner. No smile.

Andy flipped back to Cassidy’s submission. It was a PDF, too small to read on her phone, so she put the ravioli container on her nightstand and reached for her laptop. Cassidy was the first author, so she would have done the bulk of the writing. The last name listed was a Ph.D. at Columbia. It was a name she’d seen in print a number of times, although never at Cellular Function.

Andy read. For a moment, absorbed in the text, she allowed herself to forget the paper’s author. It was a descriptive study on regulatory kinesins in microtubules, and although it was quite a bit more specialized than what the journal usually published, the writing was good and the design seemed solid. She skimmed enough to decide which of her colleagues should review it, deidentified it, and forwarded it to Rashad. Her hands, she realized, had become ice-cold.

She felt nervous.

It was a strange, foreign feeling, like someone had whooshed her consciousness back into her twenty-three-year-old body. She felt exactly like she had for the entirety of the almost-year at Runway, and she knew exactly why.

Miranda.

She wouldn’t be the one to decide whether or not the paper would be accepted—that was Rashad’s job, and he’d review it blindly, without knowing the authors. But it would be her name on the letter. She could just imagine Cassidy presenting a rejection to her mother. Would she remember Andy?

She wondered, briefly, if it was possible to recuse herself from a submission, as an attorney might recuse herself from a case in which there was a conflict of interest. Oh, God. If the paper got rejected, she was going to have to quit her job.

No. She shook herself. What was she thinking? Cellular Function had nothing to do with Runway. There was absolutely no overlap between scientific journals and fashion writing. Miranda reigned over Elias-Clark, sure; her reach might even extend to print media beyond New York. But Andy would bet her left pinky that no one in her current sphere—besides Trixie, of course—even knew who Miranda Priestly was.

She swallowed her anxiety with a few more bites of her now-cold ravioli. Old habits, it turned out, died hard.

She showered, turned off the lights, and climbed into bed, but sleep was a long time coming.

***

The paper did not get accepted.

Andy had known it wouldn’t. Upon closer reading the following morning, it really was too specialized for their applied-science journal. More suited for Experimental Cell or Developmental Immunology. Three weeks after she sent it to Rashad, she got the email back that it had been rejected. Fuck.

She copy-pasted the rejection template into an email reply to Cassidy and her coauthors, staring at it for a long time as she chewed on her thumbnail. It was a good study. It would surely be accepted at a different journal, and she could come up with four or five off the top of her head.

Cassidy’s mentor would know that. She was undoubtedly accustomed to rejections, and would have a list of next choices to which the article would be submitted.

And yet.

It wasn’t exactly forbidden to deviate from the standard reply, nor was it exactly forbidden to give recommendations for future submissions. But in her seven years at the publication, Andy had never done so; had never seen the need. Now, though, she wanted to, and she had the uncomfortable realization that it wasn’t because she worried about Cassidy’s disappointment.

It was because she was worried about Miranda’s.

She didn’t want Miranda to see Andy’s name at the bottom of that letter and think that Andy was responsible for her daughter’s failure to appear in the journal she’d selected. After all this time, after everything Miranda had put her through, she didn’t want to let Miranda down.

She sent the template off to Cassidy, just as she’d done for the past seven years, with no additional commentary or suggestions. Then she did something that was either exceptionally kind or exceptionally stupid: she opened her personal email and sent Cassidy a message.

Dear Ms. Priestly:

Thank you for your submission to Cellular Function. Although your work was not accepted, the writing was — what? Andy thought. Good? No, it was better than good, although Cassidy’s youth and inexperience showed. The writing was more than acceptable. Please consider submitting to the following journals.

She listed the five she could think of—she had friends at three of them—thanked Cassidy again for her work, and sent the email before she could think better of it.

Probably exceptionally stupid, she decided, immediately after the soft whoosh of the message zooming away. She had no doubt that her boss would have something to say about her endorsement of journals other than their own.

She wondered if Cassidy would tell Miranda about it. The thought made her feel unsettled and uneasy—and, although she didn’t like to admit it to herself, just the tiniest bit hopeful.

***

Cassidy’s reply that afternoon was just one sentence, and Andy’s burst of laughter was so loud that Trixie jumped and glared at her.

ANDREA SACHS IS THAT YOU?

Well. Maybe not so stupid after all.

It’s me, she typed back. Surprised you remember.

The response this time was almost instantaneous. Of course! Harry Potter! Are you still in the city? Let’s have coffee. And her phone number.

The immediate familiarity, such a stark contrast to her mother’s standoffishness, took Andy slightly aback. At least the brevity was familiar.

Sure, she sent back. Which was why, two days later, she was sitting in a Starbucks on the Columbia campus, waiting to greet someone she had thought she’d never see again.

Cassidy arrived at precisely five-thirty, saw Andy at once, and beamed. “Oh my God,” she said.

Andy got to her feet. Cassidy didn’t quite hug her, but she took Andy’s hand in both of hers and pulled her in for an air-kiss near Andy’s cheek. The residue of high society, Andy supposed.

“I can’t believe it’s you,” Cassidy exclaimed. Her blue eyes were sparkling behind outsized tortoiseshell glasses. Her bright copper hair had been cropped into a shaggy lob, and she was wearing clothes that Andy was fairly certain Miranda would hate: a gigantic Columbia sweatshirt, leggings, and beat-up Ugg boots. A messenger bag with a seat-belt strap was slung over her shoulder. She looked every inch the graduate student.

“I’m sorry about your paper,” Andy said by way of greeting.

Cassidy waved a dismissive hand and dropped into the armchair across from Andy’s. “Don’t worry about it. Aisha has a publication plan that’s sixteen journals deep for everything she puts her name on.”

Andy felt a little silly at that, since in her mind’s eye, she had only really seen the disappointed face of a young adolescent. “Oh. Good,” she said lamely.

“Your email was so nice,” Cassidy added quickly. “I really appreciated it.” She slid her bag off her shoulder and dropped it on the floor, and as she did so, Andy saw the flash of a small diamond on the ring finger of her left hand.

Cassidy followed her gaze, and for a moment, Andy saw the impish twinkle of so many years ago. She held her hand up and waggled her fingers. “Two months ago,” she said, grinning wickedly. “He’s an engineer. Mom was pissed.”

Andy laughed, even as something in her chest twinged at the mention of Miranda. “I can only imagine.”

It was a nice visit—really nice, Andy thought, after Cassidy had left for class. She’d learned a lot about the twins’ lives. Cassidy was, as she’d assumed, in a Ph.D. program in microbiology. Caroline had graduated from the Tisch photography school. They didn’t live together, but their apartments were three blocks apart, and Cassidy was thinking of moving in with the fiancé after her lease was up.

What she didn’t mention—what Andy desperately wanted to ask, but didn’t dare—was anything about Miranda, other than a brief roll of her eyes when she mentioned “cohabitation.”

She didn’t say if Miranda was still in the townhouse, if she’d remarried, if she was happy. She’d be fifty-six in November; was she still the formidable figure of a decade ago, or had she softened with age?

Cassidy hadn’t said; had carefully avoided the topic at all. Andy had the feeling that there was a lot about Cassidy’s life these days that Miranda didn’t know. So she doubted, very much, that Cassidy would mention their meeting to Miranda.

And she couldn’t quite decide if that knowledge brought relief or disappointment.

***

Cassidy texted her the following week—favor to ask. It turned out she was writing two other papers and wondered if Andy would look over them before she submitted, if she had time.

Andy didn’t have time, but she had liked seeing Cassidy and wanted her to do well. And she had to admit, it gave her a sort of gleeful satisfaction to see the apple falling so far from the polished-gleam tree.

They met two more times at the Starbucks, this time for revisions. The engineer fiancé, Patrick, stopped by the second time. He was sweet to Cassidy, and cheerfully greeted Andy, and for a moment Andy remembered how in love she’d been with Nate at twenty-two. She hoped Patrick and Cassidy would last.

The fourth time they met, Cassidy arrived looking pale and terrified. “I’m sorry—” she got out, just before the door swung open and Miranda stepped inside.

Andy froze.

The Chanel sunglasses rotated slowly and stopped at Andy. One eyebrow crept up.

“I don’t know how she knew it was you—” Cassidy hissed, as Miranda took slow, deliberate steps toward them. Her cheeks were bright pink. “I’m really sorry.”

“Andrea.” Miranda’s voice, cool and aloof, unchanged in ten years.

Andy realized she was standing. When had she stood up? Her heart was hammering so hard she could feel it in her toes.

Miranda looked—well. Miranda looked amazing. It was still cool enough, in early April, for outerwear, and Miranda’s black fitted coat cut a silhouette far too classy for a college campus coffee shop. A white silk scarf was knotted at her throat—Hermès, no doubt. Her lips were pale pink, a shade entirely at odds with her terrifying deportment. Heads turned.

“Miranda,” Andy managed to say. Her voice sounded strangled.

Miranda lowered herself elegantly into the chair next to Cassidy’s, as though it was completely normal for the editor-in-chief of the biggest fashion magazine in the industry to be hanging around with graduate students and aspiring playwrights. She tipped her chin down just a little—just enough for Andy to meet her ice-blue gaze. “So you’re the mysterious proofreader,” she murmured, her expression entirely unreadable.

Cassidy collapsed back into her chair and put her face in her hands. “Why are you like this,” she groaned.

Miranda appeared not to notice. “Sit, please, Andrea.”

Andy sat.

“Cassidy, bobbsey,” Miranda said, removing her sunglasses and placing them on the crumb-dusted table, “be a darling and get Mummy a latte, won’t you?”

“Oh my God,” Cassidy said, with an adolescent flounce, but she got up and went to the counter.

Andy couldn’t think. Literally couldn’t think. How many times had she imagined this scene—reuniting with Miranda, apologizing for her phone-tossing temper tantrum and for her epic Parisian storm-out? Garnering Miranda’s forgiveness? Maybe, heaven help her, even earning a little of Miranda’s respect for the place she’d carved out for herself in publishing? She was, after all, an editor now too.

But despite herself, she was just sat here, dumbly staring at the woman whose presence loomed so large in her life even now, and she couldn’t think of a damn thing to say.

Fortunately, Miranda didn’t seem to require much of a response. Or any, for that matter.

“Cassidy’s happiness is of utmost importance to me,” Miranda said softly.

Well, duh. “Right,” Andy said blankly.

“She is an extremely driven young woman.” Miranda’s eyes darted momentarily toward her daughter, who was now nibbling on a pink cake pop as she waited for the latte. Then they fixed back on Andy, “And her drive has taken her into a field about which I know very little.”

I’ll say. Still, Andy was surprised that Miranda was willing to admit any gap in her knowledge, no matter how obvious. She tried to keep her expression neutral, to avoid reinforcing Miranda’s assertion and possibly causing offense.

“You, Andrea,” Miranda continued, not quite meeting Andy’s gaze, “are in the unique position to influence my daughter’s career more than I.”

Ah.

So that was it. Miranda wanted to make sure she didn’t fuck up Cassidy’s trajectory. Of course that was what it was. She had no interest in Andy’s apology, no interest in Andy’s life.

Caught between dismay and indignation, Andy straightened her spine. “Look, Miranda,” she said, “I may not be walking the red carpet, but I’m good at my job. I’m not going to crash her plane into the mountain, okay?”

Something that looked like surprise flashed across Miranda’s face, but before she could respond, Cassidy appeared at her elbow. “Your latte, your majesty,” she said, setting the cup onto the table.

Miranda’s expression morphed into a gracious smile. “Thank you, my love,” she said, reaching for her sunglasses. “I’ll let you two work, shall I?” She stood without a second glance at Andy, taking her coffee, and kissing the air beside Cassidy’s head before gliding out the door to her waiting car.

Cassidy looked mortified. “What did she say? Never mind. I don’t want to know.”

“It’s fine.” Andy’s heart rate was starting to come back down into the normal range. “Don’t worry about it.” Although she still felt flushed and angry at the implication that she was going to —what? Get Cassidy blacklisted from Cell? Keep her from a tenure-track position?

“I’m sorry,” Cassidy said again, miserably.

“Seriously,” Andy said. “Stop. Let’s just finish this draft, okay?”

***

Andrea,

I would appreciate a meeting. Wednesday at The Modern, 8pm?

“What the fuck,” Andy muttered.

What did that even mean? I would appreciate a meeting. “Well, I would appreciate a raise and an extra six weeks of vacation,” Trixie said, when Andy spun the laptop toward her emphatically. “Are you going to go?”

“I mean—” Andy flopped her hands helplessly at her side. She didn’t particularly relish the idea of an encore of the Starbucks conversation. At the same time, the brief interaction had reminded her why she sought—why she craved—Miranda’s approval way back then.

Of course, a few other things had come to light in the past few years, as well.

After she and Nate had reconciled and she’d made the move to join him in Boston, he had been so happy. The new job. A bigger apartment. He’d brought her flowers every week on his way home from the restaurant. Andy had blamed her diminishing interest—and libido—on depression: she’d been unable to find a position with any of the local newspapers, not even in Classifieds, and she refused to call Runway for a reference. Miranda had already handed her one favor and she would not be further beholden. When she finally landed the little position at the medical journal, she did feel better, but something with Nate had been irrevocably lost.

There was a girl at the journal. Her name was, improbably, Logan, and she had close-cropped hair and graceful wrists.

Andy would gaze at the ceiling while Nate groaned and sweated against her, and she would think about those wrists. She started to close her eyes when Nate kissed her. The feeling of his stubble against her skin made her flinch.

Nate wasn’t obtuse. “Is there someone else?” he’d asked.

No, of course not, she’d said, and there hadn’t been, even though her thoughts had wandered long ago to arms, and shoulders, and the brush of short auburn curls against the curve of a downy neck.

He asked, and she protested. Again and again, for months, until one day he stopped asking, stopped trying to touch her at all. When she told him she was leaving, he didn’t look surprised.

She kissed a woman for the first time two days after her twenty-sixth birthday, both of them happily tipsy in the middle of the dance floor of a downtown Cincinnati nightclub. Andy hadn’t even gotten her name, but the following morning, lying in bed with a screaming hangover, she thought a lot of things in her life had just become a whole lot clearer.

It had taken Trixie’s droll observation after her third date in a week—“You definitely have a type”—to make Andy realize that there was a huge, terrifying reason that she had tried so hard to curry Miranda’s favor.

“I wanted to sleep with my boss,” she told Trixie over the phone, at three in the morning on a Wednesday.

Trixie’s voice was thick with sleep, but she sounded shocked nonetheless. “Cheryl?” she said.

“No.” Andy put her hand over her eyes. “Miranda.”

“Oh.” The shock dissipated. “Yeah, dude, you and everyone else.”

Andy blinked. “Really?”

“Yes.” Trixie sounded like she was rolling her eyes. “Hot and mean? Duh. I’m going back to sleep.”

***

“So are you?”

Andy blinked. “What?”

Trixie pointed at the screen. “Going to meet Miranda.”

“Oh.” Andy turned the laptop back toward herself. “Um. I don’t know. I guess so. Yeah.”

“Good thing you have two days to make up your mind,” Trixie said, sounding amused, and turned back to her own computer.

Would she go? Of course she would go. Any uncertainty was pretense.

She sent back one word.

Yes.

#mirandy#wip#janewestin writes#miranda priestly#andrea sachs#andy sachs#the devil wears prada#fanfiction#work in progress

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Blue Paladin

Short fic based on THIS cool AU

https://inomana.tumblr.com/post/159586928118/space-pirate-au

Check them out here! @inomana

Feel free to leave comments on how to improve my writing, or other AU’s I could write for. Enjoy!

Btw I use female pronouns for Pidge even though its supposed to be the first episode because honestly using male pronouns feels so fucking weird.

Keith groaned as he and Hunk walked back into the throne room. It turns out that planet wasn’t nearly as “peaceful” as Coran had told them. Pidge and Shiro were already there waiting for them. They said their mission had been difficult, too, but Keith had a sneaking suspicion it hadn’t been. All four of them turned to Coran, who was explaining the situation.

“All right everyone, now this may be a bit more challenging than the last two.”

“More challenging than that?” Hunk asked incredulously. “We barely survived that last trip!”

“Why, where are we going Coran? Is it controlled by Galra or something?” Pidge asked.

“Nope. I’m afraid to say the Blue Lion is in the hands of some rather nasty looking pirates. I’ve had a couple run-ins with some of their lot before. Remember that awful time we had at that Unilu swapmeet, Allura?”

Allura seemed to sense a long winded story approaching. “Yes, yes, get to the point Coran, we have limited time here!” she said, quickly shutting him up.”

“Er, right. The point is that we need to get the lion and get out before we arouse too much suspicion. And, there’s the fact that we have no one to pilot the blue lion.”

“Because we are not sure who will pilot the lion, we will need to be able to get it without piloting it, which will undoubtedly be a hassle if its shield is up,” Allura added.

“Quite so! This means that one of you will need to enter the ship, sneak around until you find the cargo bay, and open the doors so that we can get the lion!”

Shiro and Lance both looked immediately to Pidge. She hung her head, sighing as she realized there was only one person up to the job.

“Coran, are you sure we shouldn’t use our lions?” Hunk asked for the third time.

“Yes! We can’t just blow them out of the sky, they could have prisoners onboard. These rotten gangs are infamous for abducting random aliens. Not to mention, if they spot us coming, they’ll probably try to escape in hyperspace, and come back with Galra, or even more of their pirate friends!”

Keith groaned inside of the green lion. Hunk’s lion was the strongest, so he was waiting nearby to escort the blue lion. Which meant Keith was tasked with distracting the pirates while Pidge hacked into the cargo bay doors or whatever. The entire group knew that it would be difficult for anyone to navigate the ship without being noticed, so Keith would be in charge of keeping an audience. He knew it was the best plan, but it still worried him. They had no idea how long it would take, or how many crew members there would be. They were almost completely blind. It wasn’t the greatest feeling in the world.

Pidge activated the temporary cloak she had somehow managed to rig up, and they made their way into the ship.

The first thing he noticed was the smell. It didn’t smell how he expected a pirate ship to smell. He had also expected it to be filthy, with dirt caking the walls along with unidentifiable smears and stains. It wasn’t flawless, like the castle, or the lions, but it was well-kept. There was a faint aroma of lavender, like…God it smelled like the air fresheners at the garrison. He hadn’t expected to be struck with homesickness in the middle of an alien pirate ship but there he was.

He thought back to how they’d gotten this far. They had found Shiro lying in that pod, only to be pulled off the ground by the massive tractor beam of an alien vessel. It had been chance really, that they made it out of that Galra cruiser alive. That ship had just happened to be the one carrying the red lion. When he had struggled against his captors (nearly getting killed in the attempt), and from within the ship the red lion had come to save him, crashing straight through the deck of the ship. It hadn’t been the most relaxing day for him.

“Keith! Snap out of it!”

He nodded to Pidge and tried to clear his head. “I know, I know, but-“

“I know, Keith. I smell it too,” she whispered. “But right now we have bigger problems.”

She was right of course. He shook his head to clear it once more, and made his way to the main deck, where he’d announce his presence. He could see cameras placed strategically to capture nearly every angle. They all overlapped in one spot. He took a breath and moved into the limelight.

Almost immediately, alarms began blaring all around him. Most of the pirates closest to him were frozen in shock, but he knew it wouldn’t last long. He took off running.

Dozens of guards began trying to flank him as he sped through the ship trying desperately not to get lost in a dead end. At some points he could see three or four guards after him, occasionally eleven or twelve. Both Keith and the pirates knew this chase wouldn’t last much longer.

Eventually, he looped back to the main deck. This time he was completely surrounded. He drew his bayard and raised his shield as some twenty guns and knives were aimed at his head.

A man walked out of the circle who seemed to be the leader, and again, his expectations were shattered. He was thin and wiry almost, and barely taller than Keith, but despite his small frame, the expressions of the men around him were ones of awe and respect. This was not only someone they feared, but someone they trusted. If Keith tried to hurt him in any way, there was no doubt he’d be at the mercy of every one of them. There were two guns visible at his hips, but he was likely hiding a few extra weapons in the many pockets of his clothing. Keith could get no read on him. His whole face was hidden with a large hood, goggles, and a mask around his mouth. He even had gloves on, as though he were trying to hide just about anything that could reveal his identity.

“So, who are you, and what exactly do you think you’re doing on my ship?” Keith shuddered. Even his voice was garbled so it was indistinct and unidentifiable.

“I’m here for the blue lion.” He figured it would be best to be direct, since he didn’t really have any other good reason to be there.

He was wrong.

The crowd visibly shuddered. Then like a wave laughter spread through their ranks, all the way until it reached the captain. Though Keith couldn’t see his face, he somehow managed to radiate both derision and displeasure.

He spoke again, voice still garbled, but now containing an unmistakable lilt of mirth. “Well, at least he’s honest about it! What do you say, guys? Should we hand it over? I don’t know if I’d want to get on his bad side, he looks scary!”

Keith growled as fresh laughter circled him. He’d never been all that good at talking anyway. He lifted his sword and charged the leader, hoping to surprise him.

Faster than he could even register it, both guns were out of their holsters and pointed at him. Two shots were fired, one after another. Keith felt a stinging pain in his hand, forcing him to drop his sword just as the second shot hit him square in the face. He flew backward, unbalanced and defenseless. Groaning, he tried to get up, only to be forcibly yanked off the floor by the pirates standing closest to him. His helmet was yanked off his head, and he looked up to see the leader holding a pistol to his forehead.

As he looked up at him, the man seemed to falter, as though confused. Keith could feel his eyes boring into his, questioning ad, for the briefest of moments, unsure. Then the moment, and he laughed, harder than he had before, like the universe had played a joke on him and he was just now understanding it. He lowered his gun, doubling over in hysterics.

Desperately, he tried to regain his composure. The man removed his goggles, placing them on his forehead while he wiped tears from his eyes. They were startlingly blue, and filled with genuine humor.

“I should have known the second I saw that mullet! I can hardly believe it!” He paused as fits of laughter coursed through him once more. His eyes seemed to harden, though Keith could tell he was smiling. “It’s nice to see you again, Keith.”

He froze, eyes widening.

“It is Keith, isn’t it? Keith Kogane? Here I thought you were just some punk looking for a fight, but now I can see that’s not the case. You just don’t really know the rules around here just yet. Not your fault really, but you must understand I can’t allow you to stay on my ship.”

Keith shook his head, more confused than ever. “Wha-wait how do you know my name? Who are you?”

He laughed, again, more somber than before. “Even if you knew my name, I doubt you’d have remembered me. You likely had other things on you mind.”

He racked his brains, trying desperately to identify him. This person could be from earth, but that was impossible. Even if he’d been at the Garrison, there was no way he’d been able to get this far into space. But how else could he know his name?

The pirates holding him forced his helmet roughly back onto his head. The captain turned back to him, his eyes filled with something…regret? Then he sighed, and replaced his goggles.

“Well, I hate to do this to you, buddy, but I run a tight ship. I don’t have room for stowaways.” He signaled the men holding him.

“Wait, please! Tell me your name, where I know you from, anything!” he shouted, desperation filling his voice.

The captain looked at him, cocking his head as though considering him. “No one is getting my lion. When you get picked up by the rest of your crew, you had better tell them to run far, far away from here.” He turned and walked back into the crowd, shouting for everyone to get back to work.

“Come on, Pidge,” he thought. The two aliens shoved him roughly into an airlock. He quickly closed off the shield of his helmet and tried to brace himself. He could hear a robotic voice counting down the seconds.

“8…7…6…”

Then, through the window he could see the alarms blaring on the inside of the ship. People began rushing by, all heading in the same direction. Pidge had managed to open the cargo bay doors.

“4…3…2…”

He saw the captain outside the airlock. Even with his entire face shielded and masked, Keith could feel the bitter rage pouring from him.

“…1. Airlock opening.”

The doors opened, and he was pulled into the vacuum of space.

For a few seconds he could feel nothing, just the breath in his lungs and the distinct feeling of motion. Then he was swallowed up by the jaws of Hunk’s lion. He made it to the cockpit and nearly collapsed, still shaken from all that had happened.

“Keith are you alright? Are you hurt?” he asked. The blue lion was already in the yellow lion’s paws, and they could see Pidge nearby with the pod.

He looked back toward the airlock of the ship, remembering the haunted look of the captain’s blue eyes they stared into his.

“I’m fine.”

Shiro was able to take control of his lion, but the blue lion remained empty. Both Coran and Allura had attempted to enter it, but its particle barrier had gone up as soon as it touched Arusian soil.

Later, over some of Hunk’s cooking, they discussed the problem of the fifth paladin.

“I still don’t quite understand. How are we supposed to find them? Couldn’t it be literally anyone in the entire universe?” Pidge asked.

Allura frowned into her bowl of goo. “I don’t know, but we must trust that we will find them. It will likely happen completely by chance. Like when you were picked up off your planet by the one ship with the red lion in it. I think we may find the blue paladin when we least expect it.”

“In the meantime, we’ll just have to work together as best we can. We can’t form Voltron, but we still need to practice working as a team. Each of us must have a strong bond with our lions, or we may never defeat the Galra,” Shiro said. Coran stood up from the table. “While you’re all doing that, me and Allura will see to the repair of the castle. It is ten thousand years old after all!”

Keith groaned. He couldn’t wait to leave. Something about being still for so long kept gnawing at him. He didn’t know why, but he felt trapped, caged like the lions in their hangars.

The sun set over Arus. Nearly all of the paladins were asleep, and Allura had finally gone to bed at Coran’s insistence. Besides him, Keith was the only one still awake. He couldn’t shake the eerie feeling he kept getting, so he was listening to music to pass the time until he was tired enough to pass out.

Unbeknownst to him and the rest of the paladins, a ship was carefully landing in the courtyard.

Keith was just about to fall asleep when he was jerked out of subconsciousness by blaring alarms. He could hear the other Paladin’s shouts of surprise, and over the intercom Coran began shouting incoherently.

“Paladins wake up, quick! We didn’t pick them up on our scanners you’ve got to-“ his voice became washed out by static. Keith hurriedly put on his armor and grabbed his bayard. Running past the other’s rooms he made his way to the bridge of the castle. Before he could get there, however, he ran into someone he had not expected to see.

“You.”

Keith barely had time to register the familiar modulated voice as several of the pirates charged at him. He dodged the first two and ducked under the blade of the third. He tried to sweep the legs out from underneath the fourth and raised his shield to block the bullets headed for his skull. Flying into a whirlwind he used his shield and the hilt of his sword to knock them down. In the close quarters of the hallway they couldn’t hope to surround him like they had on the ship, and they went down one after another. Finally, he faced the captain. The guns were out again, but this time Keith was ready. He held his shield up, flinching as several shots hit him but did no damage. As the captain attempted to reload his blasters Keith brought his shield up over his head and rammed it down as hard as he could.

He groaned, voice modulator cracked and messing up his voice even more than before. Before the man could get up Keith kicked away the guns in his hands. He brought his sword under his chin.

“Now you’re going to tell me exactly who you are. How did you know my name? Who are you?” he demanded.

The captain made to get up, hands lifted above his head. Not taking chances, Keith quickly backed him up against the wall.

“Easy, pal, I’d like to keep my face if you don’t mind,” he said, his breath coming slowly. Carefully, and in full view, he pulled back his hood and removed the goggles and broken mask. Keith nearly dropped the sword. The captain wasn’t even a man. He couldn’t have been any older than Keith, despite being slightly taller than him. But that wasn’t the strangest thing. He was…

“You…you’re human.”

“Surprised?”

Keith lowered his bayard and tried to get a better look at him. He had short brown hair, but not short enough that it was wiry. His skin was tanned, and he had a kind of impish grin, one that made Keith so nervous he shuddered.

“How?” He only had room for a few words at a time. He kept getting distracted by those eyes. They were blue, like the ocean, but they had a kind of harshness to them, so that even when he smiled, he looked ready to murder. This kid was battle-worn and sharp as the blade in Keith’s hand.

“Even if I told you my name, I don’t think you’d recognize it. But it still fits me after several deca-feebs.” He smirked, stepping closer and gently nudging the sword out of the way. “The name’s Lance.”

Keith only had time to blink in surprise as he attacked, grabbing his sword hand and pulling a knife from inside a coat pocket. He could do nothing as Lance flipped him around, pinning him to the wall with the blade pressed against his throat. He tried to shout, but felt the knife press into his skin, effectively choking off his protests.

“Listen, Keith, I really don’t want to hurt you. But I need that lion you stole from me. Seems to me like you’ve got four perfectly good ones, so I don’t think you really need mine. Really, how many lions does a guy need?”

Keith knew he could die. Lance would kill him, and he might sleep uneasily for a few nights, but it would pass. Still, despite his better judgement, he didn’t want to give up the Blue Lion. It could end up with the Galra, or worse. He strained desperately against Lance’s grip, but he was taller, and much, much stronger than he looked.

“I’m only going to ask you once, man. Where. Is. My. Lion!”

“Stop!”

Lance whirled, as he heard Shiro’s shout. His knife hand was still pressed against Keith’s neck, but he quickly drew another knife and was about to throw it when he saw the entirety of the group. Keith felt his grip slacken and took the opportunity to shove him toward the other side of the room, as far away from him as possible. Retreating to the rest of the paladins, they turned to face Lance, only to find he was…laughing.

He composed himself enough to look up at the group. “Well, this is not how I thought this day was going to go,” he remarked, dissolving into giggles once again.

Keith was confused, but Hunk stepped forward, his face set in a worried frown.

“Lance?” he asked. Then Keith finally remembered. Back at the garrison there had been a boy who took the blame for his disciplinary issue, all because Keith was the better pilot. Lance had been right. He barely remembered the name. The only person he’d ever heard it from was Hunk, his old engineer.

Lance looked up, his eyes filled with a kind of bitter sadness. For the first time he smiled a true genuine smile. It looked like it hurt, like his face was cracking, and they could finally see the loneliness hidden beneath. “It’s good to see you, man. It’s been, what? Two deca-feebs or so? It feels like forever,” he said, his voice tinged with a mixture of sadness and relief.

Hunk looked frozen, scared almost, but he his jaw was set in a determined line. “How the quiznak did you get here? The last I heard you were kicked out of the garrison then, nothing. Nobody knew where you went. I thought...” he trailed off.

Lance hesitated, then sheathed both knives and retrieved his blasters. He seemed to take a moment to consider something, then shook his head as if trying to dismiss the idea. Finally, he said resignedly, “You want answers, and that’s fair, but you have to get me to the blue lion first. Then, I’ll explain everything, cool?”

The paladins had been unanimous. Keith was reluctant, but even he was curious about the boy who seemed far too young to be in this kind of scenario (a lot like them, he thought). They led him cautiously toward the hangar where the lion was waiting. As they got closer, he began to walk faster and faster. He paused, as though listening for something, then sprinted down the castle’s hallways. Alarmed, the Paladins shouted and ran after him, but he seemed to know exactly where to go to lose sight of them. Finally, Keith found him next to the blue lion. What he saw sent shivers down his spine.

The lion’s particle barrier was down, and its jaws were open to let Lance inside. Lance was the blue paladin.

He turned around before stepping into the lion and smiled knowingly. “Surprised?” His tone held none of the mockery it had before. His smile was wide and his blue eyes sparkled. Keith noticed how much they looked like gems. He looked back up at the metal beast with admiration, like one would look at a close friend.

“She saved me, you know. When I got kicked out of the Garrison no one came to get me. My family just, didn’t show up. So I just left, walked out into the desert. I don’t know why, but this one place in the cliffs seemed to call to me. I found a cave there, with glowing blue markings. They guided me to where the lion was hidden.”

He didn’t know why, but Keith felt the need to explain himself as well. “I never knew you’re name, but the commander at the Garrison always told me how I nearly got kicked out and was only allowed to stay because they shifted the blame onto you to keep me there. It felt like prison sometimes. Hunk and Pidge made it better of course, but it sucked there.”

“I wonder if my parents ever cared that I was gone.”

Keith stared in disbelief. “Of course they did! There was a huge story about it. The Garrison told everyone you ran away, and your entire family tried to sue them, but they couldn’t because they didn’t have enough concrete evidence.”

Lane looked at him, confused. “Really?” he asked, not daring to believe it. “Then why weren’t they there? Why didn’t anyone come for me?”

“I don’t know. All I really know is that you were presumed dead. They probably had a funeral and everything.”

Tears welled up in his eyes as he saw that Keith wasn’t joking. “I…I can’t believe it. All this time I’ve been avoiding Earth because I didn’t think anyone wanted me there, but now…” he trailed off. “Now I don’t know what to think. I miss them. I miss them so much.”

He began to sob then, tear after tear dripping down his cheeks. He made no move to wipe them off. Still crying he suddenly hugged Keith and sobbed into his shoulder. Keith hesitated, stunned, but then carefully wrapped his arms around him.

“Thank you, Keith.”

They broke apart nervously, and Lance wiped his eyes on his glove as the other Paladins burst through the doors.

“Keith, are you alright? What happened…” Allura trailed off as she saw who the blue lion had accepted.

“I’m fine. Everyone, meet Lance, the new paladin of the blue lion.”

#voltron#klance#klangst#lance#keith#angst#first meeting#space pirates#pirate lance#space pirate au#give lance a hug

19 notes

·

View notes

Link

Nonoverlapping Magisteria

by Stephen Jay Gould

“Incongruous places often inspire anomalous stories. In early 1984, I spent several nights at the Vatican housed in a hotel built for itinerant priests. While pondering over such puzzling issues as the intended function of the bidets in each bathroom, and hungering for something other than plum jam on my breakfast rolls (why did the basket only contain hundreds of identical plum packets and not a one of, say, strawberry?), I encountered yet another among the innumerable issues of contrasting cultures that can make life so interesting. Our crowd (present in Rome for a meeting on nuclear winter sponsored by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences) shared the hotel with a group of French and Italian Jesuit priests who were also professional scientists.

At lunch, the priests called me over to their table to pose a problem that had been troubling them. What, they wanted to know, was going on in America with all this talk about "scientific creationism"? One asked me: "Is evolution really in some kind of trouble. and if so, what could such trouble be? I have always been taught that no doctrinal conflict exists between evolution and Catholic faith, and the evidence for evolution seems both entirely satisfactory and utterly overwhelming. Have I missed something?"

A lively pastiche of French, Italian, and English conversation then ensued for half an hour or so, but the priests all seemed reassured by my general answer: Evolution has encountered no intellectual trouble; no new arguments have been offered. Creationism is a homegrown phenomenon of American sociocultural history—a splinter movement (unfortunately rather more of a beam these days) of Protestant fundamentalists who believe that every word of the Bible must be literally true, whatever such a claim might mean. We all left satisfied, but I certainly felt bemused by the anomaly of my role as a Jewish agnostic, trying to reassure a group of Catholic priests that evolution remained both true and entirely consistent with religious belief.

Another story in the same mold: I am often asked whether I ever encounter creationism as a live issue among my Harvard undergraduate students. I reply that only once, in nearly thirty years of teaching, did I experience such an incident. A very sincere and serious freshman student came to my office hours with the following question that had clearly been troubling him deeply: "I am a devout Christian and have never had any reason to doubt evolution, an idea that seems both exciting and particularly well documented. But my roommate, a proselytizing Evangelical, has been insisting with enormous vigor that I cannot be both a real Christian and an evolutionist. So tell me, can a person believe both in God and evolution?" Again, I gulped hard, did my intellectual duty, and reassured him that evolution was both true and entirely compatible with Christian belief—a position I hold sincerely, but still an odd situation for a Jewish agnostic.

These two stories illustrate a cardinal point, frequently unrecognized but absolutely central to any understanding of the status and impact of the politically potent, fundamentalist doctrine known by its self-proclaimed oxymoron as "scientitic creationism"—the claim that the Bible is literally true, that all organisms were created during six days of twenty-four hours, that the earth is only a few thousand years old, and that evolution must therefore be false. Creationism does not pit science against religion (as my opening stories indicate), for no such conflict exists. Creationism does not raise any unsettled intellectual issues about the nature of biology or the history of life. Creationism is a local and parochial movement, powerful only in the United States among Western nations, and prevalent only among the few sectors of American Protestantism that choose to read the Bible as an inerrant document, literally true in every jot and tittle.

I do not doubt that one could find an occasional nun who would prefer to teach creationism in her parochial school biology class or an occasional orthodox rabbi who does the same in his yeshiva, but creationism based on biblical literalism makes little sense in either Catholicism or Judaism for neither religion maintains any extensive tradition for reading the Bible as literal truth rather than illuminating literature, based partly on metaphor and allegory (essential components of all good writing) and demanding interpretation for proper understanding. Most Protestant groups, of course, take the same position—the fundamentalist fringe notwithstanding.

The position that I have just outlined by personal stories and general statements represents the standard attitude of all major Western religions (and of Western science) today. (I cannot, through ignorance, speak of Eastern religions, although I suspect that the same position would prevail in most cases.) The lack of conflict between science and religion arises from a lack of overlap between their respective domains of professional expertise—science in the empirical constitution of the universe, and religion in the search for proper ethical values and the spiritual meaning of our lives. The attainment of wisdom in a full life requires extensive attention to both domains—for a great book tells us that the truth can make us free and that we will live in optimal harmony with our fellows when we learn to do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly.

In the context of this standard position, I was enormously puzzled by a statement issued by Pope John Paul II on October 22, 1996, to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, the same body that had sponsored my earlier trip to the Vatican. In this document, entitled "Truth Cannot Contradict Truth," the pope defended both the evidence for evolution and the consistency of the theory with Catholic religious doctrine. Newspapers throughout the world responded with frontpage headlines, as in the New York Times for October 25:

"Pope Bolsters Church's Support for Scientific View of Evolution."

Now I know about "slow news days" and I do admit that nothing else was strongly competing for headlines at that particular moment. (The Times could muster nothing more exciting for a lead story than Ross Perot's refusal to take Bob Dole's advice and quit the presidential race.) Still, I couldn't help feeling immensely puzzled by all the attention paid to the pope's statement (while being wryly pleased, of course, for we need all the good press we can get, especially from respected outside sources). The Catholic Church had never opposed evolution and had no reason to do so. Why had the pope issued such a statement at all? And why had the press responded with an orgy of worldwide, front-page coverage?

I could only conclude at first, and wrongly as I soon learned, that journalists throughout the world must deeply misunderstand the relationship between science and religion, and must therefore be elevating a minor papal comment to unwarranted notice. Perhaps most people really do think that a war exists between science and religion, and that (to cite a particularly newsworthy case) evolution must be intrinsically opposed to Christianity. In such a context, a papal admission of evolution's legitimate status might be regarded as major news indeed—a sort of modern equivalent for a story that never happened, but would have made the biggest journalistic splash of 1640: Pope Urban VIII releases his most famous prisoner from house arrest and humbly apologizes, "Sorry, Signor Galileo… the sun, er, is central."