#Tomb of Rekhmire

Text

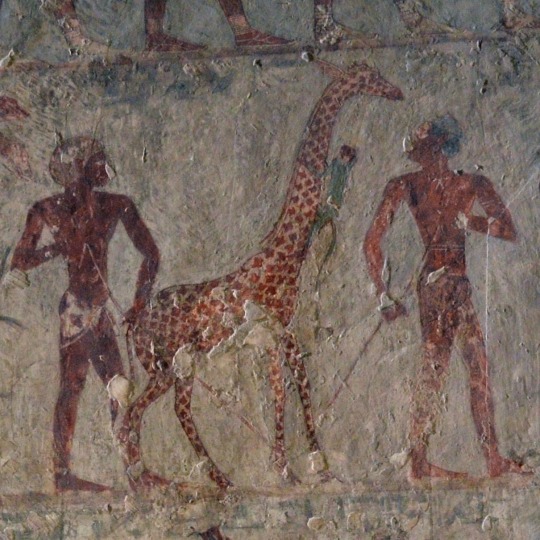

For #WorldGiraffeDay:

Wall art from Tomb of Rekhmire TT100 depicting a Nubian tribute procession, detail of #giraffe with a #monkey on its neck. #AncientEgypt, 18th dynasty, Sheik Abd el-Qurna, Thebes.

image via Wikimedia Commons [Heidi Kontkanen CC BY-SA 2.0]

#ancient Egypt#ancient art#Tomb of Rekhmire#tomb art#wall art#mural#giraffe#monkey#Nubian#Thebes#animal holiday#World Giraffe Day

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

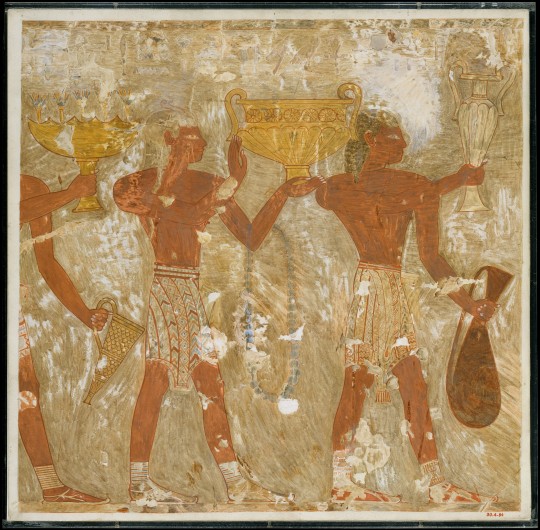

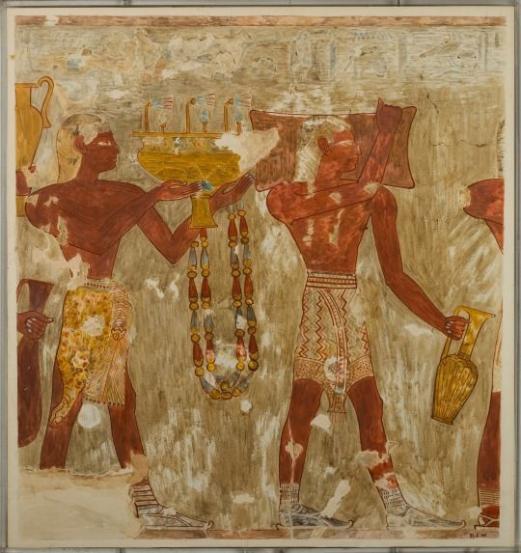

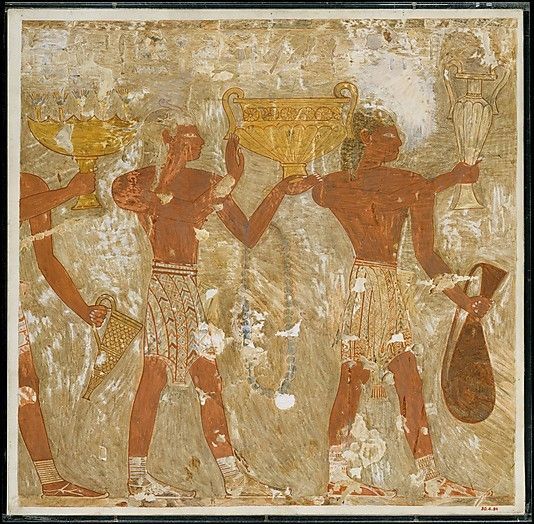

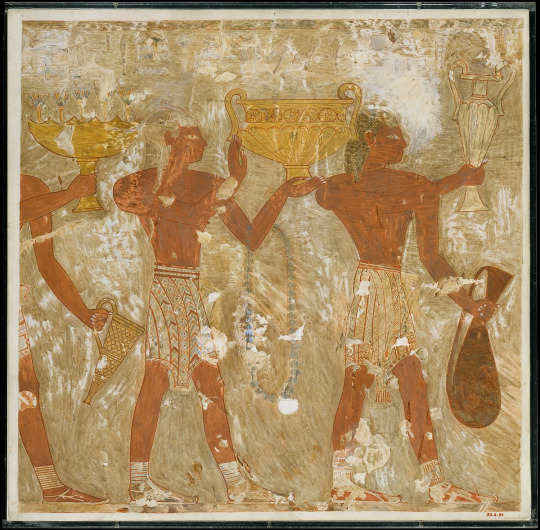

Cretans Bringing Gifts, Tomb of Rekhmire - Met Museum Collection

Note: This is a modern copy of an original

Inventory Number: 30.4.84

Original Dating: New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1479–1425 B.C.

Location Information: Original from Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Tomb of Rekhmire (TT 100)

Description:

This facsimile painting copies a detail from a scene depicting foreigners bringing gifts in the tomb of Rekhmire (TT 100) at Thebes. This part of the scene shows Aegean islanders bringing ingots of metal (31.6.42, 31.6.45) and metal vessels (30.4.84).

#Cretans Bringing Gifts#new kingdom#new kingdom pr#dynasty 18#upper egypt#thebes#sheikh abd el qurna#sheikh abd el-qurna#tomb of rekhmire#met museum#30.4.84#foreigners#NKPRForeigners

0 notes

Text

[ID: Two plates of cookies, one oval and topped with powdered sugar, and the others shaped in rings; one cookie is broken in half to show a date filling; two glasses of coffee on a silver tray are in the background. End ID]

معمول فلسطيني / Ma’moul falastini (Palestinian semolina cookies)

Ma’moul (also transliterated “ma’amoul,” “maamoul” and “mamoul”) are sweet pastries made with semolina flour and stuffed with a date, walnut, or pistachio filling. The cookies are made tender and crumbly with the addition of fat in the form of olive oil, butter, or clarified butter (سمن, “samn”); delicate aromatics are added by some combination of fennel, aniseed, mahlab (محلب: ground cherry pits), mastic gum (مستكه, “mistīka”), and cinnamon.

“مَعْمُول” means “made,” “done,” “worked by hand,” or “excellently made” (it is the passive participle of the verb “عَمِلَ” “‘amila,” "to do, make, perform"). Presumably this is because each cookie is individually filled, sealed, and shaped by hand. Though patterned molds known as طوابع (“ṭawābi’,” “stamps”; singular طابع, “ṭābi’”) are sometimes used, the decorations on the surface of the cookies may also be applied by hand with the aid of a pair of small, specialized tongs (ملقط, “milqaṭ”).

Because of their laborious nature, ma’moul are usually made for feast days: they are served and shared for Eid, Easter, and Purim, a welcome reward after the Ramadan or Lenten fasts. For this reason, ma’moul are sometimes called “كَعْك العيد” (“ka’k al-’īd,” “holiday cakes”). Plates of the cookies, whether homemade or store-bought, are passed out and traded between neighbors in a practice that is part community-maintenance, part continuity of tradition, and part friendly competition. This indispensable symbol of celebration will be prepared by the women of a family even if a holiday falls around the time of a death, disaster, or war: Palestinian food writer Laila El-Haddad explains that "For years, we endured our situation by immersing ourselves in cooking, in our routines and the things we could control."

Other names for these cakes exist as well. Date ma’moul–the most common variety in Palestine–may be called كَعْك بعَجْوَة (“ka'k b'ajwa”), “cakes with date paste.” And one particular Palestinian variety of ma’moul, studded with sesame and nigella seeds and formed into a ring, are known as كَعْك أَسَاوِر (“ka'k 'asāwir”), “bracelet cakes.” The thinner dough leads to a cookie that is crisp and brown on the outside, but gives way to a soft, chewy, sweet filling.

[ID: An extreme close-up on one ka'k al-aswar, broken open to show the date filling; ma'moul and a silver teapot are very out-of-focus in the background. End ID]

History

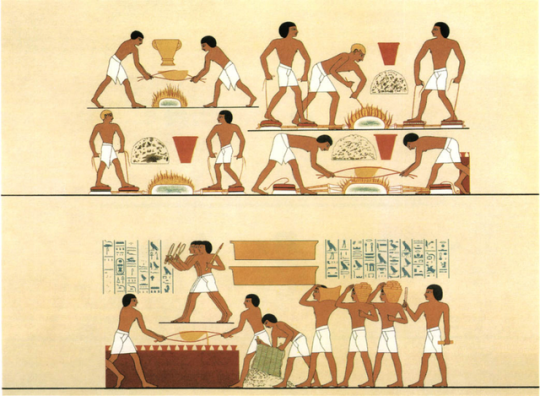

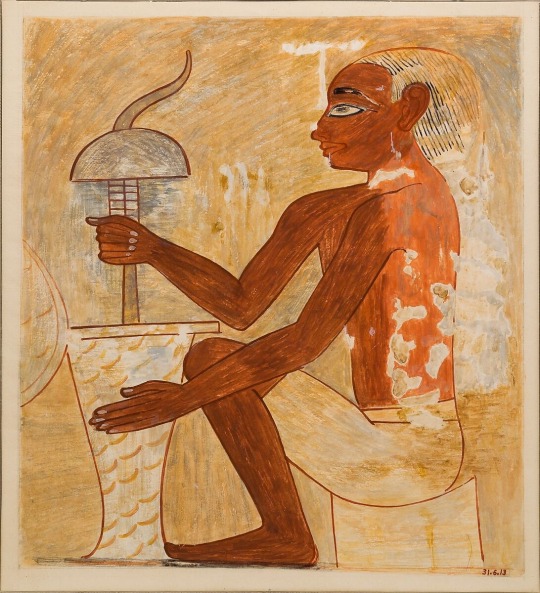

Various sources claim that ma’moul originated in Egypt, with their ancestor, كحك (kaḥk), appearing in illustrations on Pharaonic-era tombs and temples. The more specific of these claims usually refer to “temples in ancient Thebes and Memphis,” or more particularly to the vizier Rekhmire’s tomb in Thebes, as evidencing the creation of a pastry that is related to modern kahk. One writer attests that this tomb depicts “the servants mix[ing] pure honey with butter on the fire,” then “adding the flour by mixing until obtaining a dough easy to transform into forms” before the shaped cookies were “stuffed with raisins or dried dates and honey.” Another does not mention Rekhmire, but asserts that “18th-dynasty tombs” show “how honey is mixed with butter on fire, after which flour is added, turning the substance into an easily-molded dough. These pieces are then put on slate sheets and put in the oven; others are fried in oil and butter.”

Most of these details seem to be unfounded. Hilary Wilson, summarizing the state of current research on Rekhmire’s tomb, writes that the depicted pastries were delivered as an offering to the Treasury of the Temple of Amun; that they certainly contained ground tiger nuts; that they presumably contained wheat or durum flour, since ground tiger nuts alone would not produce the moldable dough illustrated; that the liquid added to this mixture to form the dough cannot be determined, since the inscription is damaged; that the cakes produced “are clearly triangular and, when cooked are flat enough to be stacked” (any appearance that they are pyramidal or conical being a quirk of ancient Egyptian drawing); that they were shallow-fried, not cooked in an oven; and that honey and dates are depicted at the far left of the scene, but their relationship to the pastries is unclear. There is no evidence of the honey being included in the dough, or the cookies being stuffed with dates; instead, Wilson speculates that “It appears that the cooks are preparing a syrup or puree of dates and honey. It is tempting to think that the cakes or pastries were served [...] with a generous portion of syrup poured over them.” Whether there is any direct lineage between these flat, fried pastries and the stuffed, molded, and baked kahk must also be a matter of speculation. [1]

Another origin claim points to ancient Mesopotamia. James David Audlin speculates that ma’moul are "possibly" the cousins of hamantaschen, both being descended from the molded "kamānu cakes that bore the image of [YHWH’s] goddess wife Inanna [also known as Ishtar or Astarte]" that were made in modern-day Syria. Other claims for Mesopotamia cite qullupu as the inspiration: these cakes are described in the contemporary record as wheat pastries filled with dates or raisins and baked. (Food historian Nawal Nasrallah writes that these cookies, which were offered to Ishtar for the new year festival in spring, may also be an origin point for modern Iraqi كليچة, "kleicha.")

The word "määmoul" had entered the English language as a type of Syrian farina cake by 1896.

In Palestine

From its earliest instantiations, Zionist settlement in Palestine was focused on building farming infrastructure from which Palestinians could be excluded: settlers, incentivized by foreign capital, aimed at creating a separate economy based around farms, agricultural schools, communal settlements, and research institutions that did not employ Arabs (though Arab labor and goods were never entirely cut out in practice).

Zionist agricultural institutes in Palestine had targeted the date as a desirable crop to be self-sufficient in, and a potentially profitable fruit for export, by the 1930s. Ben-Zion Israeli (בנציון ישראלי), Zionist settler and founder of the Kinneret training farm, spoke at a 1939 meeting of the Organization of Fruit Growers (ארגון מגדלי פירות) in the Nahalel (נהלל) agricultural settlement to discuss the future of date palms in the “land of Israel.” He discussed the different climate requirements of Egyptian, Iraqi, and Tunisian cultivars—and which among them seemed “destined” (נועדים) for the Jordan Valley and coastal plains—and laid out his plan to collect saplings from surrounding countries for planting despite their prohibitions against such exports.

In the typical mode of Zionist agriculture discourse, this speech dealt in concepts of cultivation as a means of coming into a predestined ownership over the land; eating food suited for the climate as a means of belonging in the land; and a return to Biblical history as a triumphant reclamation of the land from its supposed neglect and/or over-cultivation by Palestinian Arabs over the past 2,000 years. Israeli opened:

נסתכל לעברה של הארץ, אשר אנו רוצים להחיותה ולחדשה. היא השתבחה ב"שבעה מינים" ואלה עשוה אינטנסיבית וצפופת אוכלוסין. לא רק חיטה ושעורה, כי אם גם עצים הנותנים יבול גדול בעל ערך מזוני רב. בין העצים -- הזית [...] הגפן, התאנה והתמר. לשלושה מהם, לזית, לתאנה ולתמר חטאה התישבותנו שאין היא נאחזת בהם אחיזה ציםכר של ממש ואינה מפתחת אותם דים.

We will look to the past of the land [of Israel], which we want to revive and renew. It excelled in "seven species," and these flourished and became densely populated. Not only wheat and barley, but also trees that give a large and nutritious crop. Among the trees: the olive, [...] the vine, the fig and the date. For three of them, the olive, the fig and the date, it is the sin of our settlement that it does not hold on to them with a strong grip and does not develop them.

He continued to discuss the benefits of adopting the date—not then part of the diet of Jewish settlers—to “health and economy” (בריאות וכלכלה). Not only should the “land of Israel” become self-sufficient (no longer importing dates from Egypt and Iraq), but dates should be grown for export to Europe.

A beginning had already been made in the importation of about 8,000 date palm saplings over the past two decades, of which ¾ (according to Israeli) had been brought by Kibbutz Kinneret, and the remaining ¼ by the settlement department of the Zionist Commission for Palestine (ועד הצירים), by the Mandate government's agriculture department, and by people from Degania Bet kibbutz ('דגניה ב). The majority of these imports did not survive. More recently, 1000 smuggled saplings had been planted in Rachel’s Park (גן רחל), in a nearby government plot, and in various places in the Jordan Valley. Farms and agricultural institutions would need to collaborate in finding farmers to plant dates more widely in the Beit-Sha’an Valley (בקעת בית שאן), and work to make dates take their proper place in the settlements’ economies.

These initial cuttings and their descendents survive in large plantations across “Israel” and the occupied Palestinian territories. Taher Herzallah and Tarek Khaill write that “Palm groves were planted from the Red Sea in the south along the Dead Sea, and as far as the Sea of Galilee up north, which has given the Israeli date industry its nickname ‘the industry of the three seas’” Since Israel occupied the Palestinian West Bank in 1967, it has also established date plantations in its illegal settlements in that portion of the Jordan Valley.” Today, these settlements produce between 40 and 60% of all Israeli dates.

In 2022, Israel exported 67,042 tons of dates worth $330.1 million USD; these numbers have been on a steady rise from 4,909 tons worth $1.2m. in 1993. Palestinian farmers and their children, disappropriated from their land and desperate for income, are brought in to date plantations to work for long hours in hazardous conditions for low pay. Workers are lifted into the date palms by cranes where they work, with no means of descending, until the crane comes to lower them down again at the end of the day. Injuries from falls, pesticides, heat stroke, and date-sorting machinery are common.

Meanwhile, settlers work to curtail and control Palestinian production of dates. The Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza is used as a pool of cheap labor and a captive market to purchase Israeli imports, absorb excesses in Israeli goods, stabilize Israeli wages, and make up for market deficits. Thus Palestinian date farmers may be targeted with repressive measures such as water contamination and diversion, destruction of wells, crop destruction, land theft, military orders forbidding the planting of trees, settler attacks, closing of checkpoints and forbidding of exports, and the denial of necessary equipment or the means to make it, in part to ensure that their goods do not compete with those of Israeli farmers in domestic or foreign markets. Leah Temper writes that these repressive measures are part of a pattern whereby Israel tries to “stop [Palestinian] growth in high value crops such as strawberries, avocados and dates, which are considered to be ‘Israeli Specialties’.”

At other times, Palestinian farmers may be ordered to grow certain crops (such as strawberries and dates), and forbidden to grow anything else, when Israeli officials fear falling short of market demand for a certain good. These crops will be exported by Israeli firms, ensuring that the majority of profits do not accrue to Palestinians, and that Palestinians will not have the ability to negotiate or fulfill export contracts themselves. Nevertheless, Palestinian farmers continue to defy these oppressive conditions and produce dates for local consumption and for export. Zuhair al-Manasreh founded date company Nakheel Palestine in 2011, which continues production despite being surrounded by Israeli settlements.

Boycotts of Israeli dates have arisen in response to the conditions imposed on Palestinian farmers and workers. Herzallah and Khaill cite USDA data on the effectiveness of boycott, pressure, and flyering campaigns initiated by groups including American Muslims for Palestine:

Israel’s exports of dates to the US have dropped significantly since 2015. Whereas 10.7 million kilogrammes (23.6 million pounds) of Israeli dates entered the US market in 2015-2016, only 3.1 million kilogrammes (seven million pounds) entered the US market in 2017-2018. The boycott is working and it is having a detrimental effect on the Israeli date industry.

Date products may not be BDS-compliant even if they are not labeled as a product of Israel. Stores may repackage dates under their own label, and exporters may avoid declaring their dates to be a product of Israel, or even falsely label them as a product of Palestine, to avoid boycotts. Purchase California dates, or dates from a known Palestinian exporter such as Zaytoun or Yaffa (not “Jaffa”) dates.

[ID: Close-up of the top of ma'moul, decorated with geometric patterns and covered in powdered sugar, in strong light and shadow. End ID]

Elsewhere

Other efforts to foreground the provenance and political-economic context of dates in a culinary setting have been made by Iraqi Jew Michael Rakowitz, whose store sold ma’moul and date syrup and informed patrons about individual people behind the hazardous transport of date imports from Iraq. Rakowitz says that his project “utilizes food as a point of entry and creates a different platform by which people can enter into conversation.”

[1] Plates from the tomb can be seen in N. de G. Davies, The tomb of Rekh-mi-Rē at Thebes, Vol. II, plates XLVII ff.

Purchase Palestinian dates

Donate to evacuate families from Gaza

Flyer campaign for eSims

Ingredients:

Makes 16 large ma'moul and 32 ka'k al-aswar; or 32 ma'moul; or 64 ka'k al-aswar.

For the dough:

360g (2 1/4 cup) fine semolina flour (سميد ناعم / طحين فرخة)

140g (1 cup + 2 Tbsp) white flour (طحين ابيض)

200g (14 Tbsp) margarine or vegetarian ghee (سمن), or olive oil

2 Tbsp (15g) powdered sugar

1 1/2 Tbsp (10g) dugga ka'k (دقة كعك)

1/2 tsp (2g) instant yeast

About 2/3 cup (190mL) water, divided (use milk if you prefer)

1 tsp toasted sesame seeds (سمسم)

1 tsp toasted nigella seeds (قزحه / حبة البركة)

Using olive oil and water for the fat and liquid in the dough is more of a rural approach to this recipe; ghee and milk (or milk powder) make for a richer cookie.

To make the bracelets easy to shape, I call for the inclusion of 1 part white flour for every 2 parts semolina (by volume). If you are only making molded cookies and like the texture of semolina flour, you can use all semolina flour; or vary the ratio as you like. Semolina flour will require more added liquid than white flour does.

For the filling:

500g pitted Madjoul dates (تمر المجهول), preferably Palestinian; or date paste

2 Tbsp oil or softened margarine

3/4 tsp dugga ka'k (دقة كعك)

3/4 tsp ground cinnamon

5 green cardamom pods, toasted, skins removed and ground; or 1/4 tsp ground cardamom

Small chunk nutmeg, toasted and ground, or 1/4 tsp ground nutmeg

10 whole cloves, toasted and ground, or 1/4 tsp ground cloves

The filling may be spiced any way you wish. Some recipes call for solely dugga ka'k (or fennel and aniseed, its main components); some for a mixture of cinnamon, cardamom, nutmeg, and/or cloves; and some for both. This recipe gives an even balance between the pungency of fennel and aniseed and the sweet spiciness of cinnamon and cloves.

Palestinian date brands include Ziyad, Zaytoun, Hasan, and Jawadir. Palestinian dates can also be purchased from Equal Exchange. You can find them online or at a local halal market. Note that an origin listed as "West Bank" does not indicate that a date company is not Israeli, as it may be based in a settlement. Avoid King Solomon, Jordan River, Mehadrin, MTex, Edom, Carmel Agrexco, Arava, and anything marked “exported by Hadiklaim”. Also avoid supermarket brands, as the origin of the dates may not be clearly marked or may be falsified to avoid boycots.

Instructions:

For the dough:

1. Melt margarine in a microwave or saucepan. Measure flours into a large mixing bowl and pour in margarine; mix thoroughly to combine. Rub flours between your hands for a few minutes to coat the grains in margarine. The texture should resemble that of coarse sad. Refrigerate the mixture overnight, or for up to 3 days.

2. Add dry ingredients to dough. If making both molded ma'moul and ka'k al-aswar, split the dough in half and add sesame and nigella seeds to one bowl.

3. Add water to each dough until you get a smooth dough that does not crack apart when formed into a ball and pressed. Press until combined and smooth, but do not over-knead—we don't want a bready texture. Set aside to rest while you make the filling.

For the filling:

1. Pit dates and check the interiors for mold. Grind all ingredients to a paste in a food processor. You may need to add a teaspoon of water, depending on the consistency of your dates.

To shape the cookies:

Divide the filling in half. One half will be used for the ma'moul, and the other half for the bracelets.

For the ma'moul:

1. With wet hands, pinch off date filling into small chunks about the size of a walnut (13-16g each, depending on the size of your mold)—or roll filling into a long log and divide into 16-20 even pieces with a dough scraper. Roll each piece of filling into a ball between your palms.

2. Divide the dough (the half without seeds) into the same number of balls as you have balls of filling, either using a kitchen scale or rolling into a log and cutting.

3. Form the dough into a cup shape. Place a ball of filling in the center, and fold the edges over to seal. Press the dough into a floured ma'moul mold to shape, then firmly tap the tip of the mold on your work surface to release; or, use a pair of spiked tweezers or a fork to add decorative designs by hand.

4. Repeat until all the the dough and filling has been used, covering the dough you're not working with to keep it from drying out. Place each cookie on a prepared baking sheet.

For the ka'k al-aswar:

1. With wet hands, divide the date filling into about 32 pieces (of about 8g each); they should each roll into a small log about the size of your pinkie finger.

2. Divide the dough (the half with the seeds) into as many pieces as you have date logs.

3. Take a ball of dough and flatten it into a thin rectangle a tiny bit longer than your date log, and about 3 times as wide. Place the date log in the center, then pull the top and bottom edges over the log and press to seal. Seal the ends.

4. Roll the dough log out again to produce a thin, long rope a little bit thinner at the very ends than at the center. Press one side of the rope over the other to form a circle and press to seal.

5. Repeat until all the the dough and filling has been used, covering the dough you're not working with to keep it from drying out. Place each cookie on a prepared baking sheet.

To bake:

1. Bake ma'moul at 350 °F (175 °C) in the center of the oven for about 20 minutes, until very lightly golden brown. They will continue to firm up as they cool.

2. Increase oven heat to 400 °F (205 °C) and bake ka'k al-aswar in the top third of the oven for about 20 minutes, until golden brown.

Sprinkle cookies with powdered sugar, if desired. Store in an airtight container and serve with tea or coffee, or give to friends and neighbors.

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musicians playing the harp and the lute

New kingdom, 18th dynasty, ca. 1479- 1413 BC

Tomb of Rekhmire, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, West Thebes

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

The scene showing metal workers is part of a wall depicting different professions in the tomb of Rekhmire', vizier of Tuthmosis III and Amenophis II. Above, the fires are kept ablaze with foot-operated bellows; below, the men are casting bronze doors in a large mould. The inscription states that the bronze is brought from Asia, from the land of Retjenu.

Atlas of Egyptian art. Page 119

#egyptian hieroglyphs#egyptian#kemetism#egyptian architecture#kemeticism#ancient egypt#egyptology#egyptian gods#architecture#sekhmet#Egyptian doors#door#doors#Hieroglyphics#Egyptian house

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

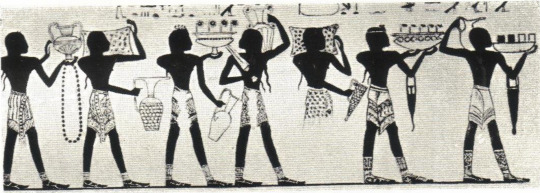

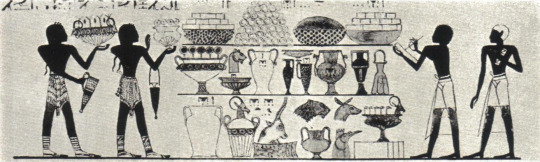

Keftiu (Minoan, Cretan, later Mycenaean) men depicted bringing tribute within the tomb chapel of the vizier Rekhmire (TT100).

New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, reign of Thutmose III - Amenhotep II, c. 1479-1400 B.C.

Valley of the Nobles, Theban Necropolis

Photograph by manna4u

http://facebook.com/Egypt.Museum

#ancient egypt#minoan#mycenaean#crete#ancient crete#cretan#ancient mediterranean#eastern mediterranean#mediterranean#ancient trade#history#egypt

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tomb of Rekhmire, who was ancient Egyptian royalty and lord, provides a glimpse into ancient Egyptian social systems and cultural traditions. This ornate tomb, located in the Theban Necropolis on the Nile's west bank near modern-day Luxor, was meticulously built to serve as Rekhmire's ultimate resting place as well as a space to remember his legacy.

The Tomb of Rekhmire, built during the New Kingdom period, is made up of numerous chambers decorated with elaborate wall murals and inscriptions. These decorations show scenes from Rekhmire's life, including his different responsibilities in the royal court and relationships with gods and goddesses. The tomb was intended not just to preserve Rekhmire's physical remains, but also to preserve his presence in the afterlife, surrounded and comforted by items and tokens that he cherished during his time on earth.

Following Rekhmire's death, his family and descendants would have paid their respects at the tomb, assuring his continuing well-being in the afterlife. The tomb may have also functioned as a venue for celebrations commemorating Rekhmire's achievements and contributions to society. In that time, this ceremony was an extremely important and spiritual event to his family and to those who wanted to honor him.

Additionally, the tomb's wall murals and inscriptions provide unique insights into ancient Egyptian religious beliefs, social systems, and artistic practices. Scenes representing the soul's journey, the judgment of the deceased, and meetings with gods and goddesses provide insight into the Egyptian view of the afterlife and the rites involved with death and burial.

Today, the Tomb of Rekhmire is a prime example of ancient Egypt's enduring legacy, providing a wealth of knowledge to archaeologists, historians, and tourists alike. Its complex decorations and architectural features serve as reminders of ancient Egyptian artisans' ability and craftsmanship, as well as the value of commemorating the deceased in Egyptian society.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This isn’t even related to my previous post I’m just posting these for fun. Depictions of Minoan peoples in ancient Egyptian art, from the Tomb of Rekhmire in Thebes, Egypt :~)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

de Garis Davies, Nina. Brickmakers Getting Water from a Pool, Tomb of Rekhmire. New Kingdom, ca. 1479-1425 BC. Tempera on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

0 notes

Text

Drilling a Stone Vase, Tomb of Rekhmire

Nina de Garis Davies (replica painted from the original for archeological research).

Via Metropolitan Museum of Art

0 notes

Photo

Bugün aynı zamanda Dünya Zürafalar Günü!! 🦒 Yılın en uzun günü olan 21 Haziran’da, yaşayan en uzun hayvanlar da hatırlanarak bu gün Dünya Zürafalar Günü olarak kutlanmaktadır. 1- Nicolas Huet the Younger - Study of the Giraffe given to Charles X by the Vicetoy of Egypt / 2- Kunyanda Shikamo - Giraffe / 3- Unknown - Giraffe Head / 4- Nina de Garis Davies - Nubians with a Giraffe and a Monkey, Tomb of Rekhmire / 5- George Skadding - Unknown / 6- Jacques-Laurent Agasse - Nubian Giraffe / 7- Comb with a Giraffe / 8- Francis Trevelyan Miller - Unknown #art #sanat #painting #photography #nicolashuettheyounger #kunyandashikamo #ninadegarisdavies #georgeskadding #jacqueslaurentagasse #francistrevelyanmiller #worldgiraffeday #dünyazürafagünü #giraffeday #sanat #benibunaannemzorladi https://www.instagram.com/p/CfEeEjTosWS/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#art#sanat#painting#photography#nicolashuettheyounger#kunyandashikamo#ninadegarisdavies#georgeskadding#jacqueslaurentagasse#francistrevelyanmiller#worldgiraffeday#dünyazürafagünü#giraffeday#benibunaannemzorladi

0 notes

Photo

Ancient Minoans, as depicted by ancient Egyptians. Egyptians called the island of Crete “Keftiu”

1. Minoan envoys on the tomb of User (on left) and Rekhmire (on right)

2-3. Minoan procession from tomb of Rekhmire

4. Minoan procession, recording of gifts from Keftiu by the Egyptian officials, from the tomb of Rekhmire

5-6. Cretans Bringing Gifts, Tomb of Rekhmire ca. 1479–1425 B.C., facsimile painting by Nina de Garis Davies

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cretans Bringing Gifts, Tomb of Rekhmire - Met Museum Collection

Note: this is a modern copy of an original

Inventory Number: 31.6.42

Original Dating: New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1479–1425 B.C.

Location Information: Original from Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Tomb of Rekhmire (TT 100)

Location Information:

This facsimile painting copies a detail from a scene depicting foreigners bringing gifts in the tomb of Rekhmire (TT 100) at Thebes. This part of the scene shows Aegean islanders bringing ingots of metal (31.6.42, 31.6.45) and metal vessels (30.4.84).

#Cretans Bringing Gifts#Tomb of Rekhmire#new kingdom#new kingdom pr#dynasty 18#upper egypt#thebes#sheikh abd el-qurna#tomb of rekhmire#met museum#31.6.42#foreigners#NKPRForeigners

0 notes

Photo

Rekhmire was a wizier during the reign of Tuthmose III and Amenhotep II in ancient Egypt's eighteenth dynasty. He also had the title of Governor of the Rekhmire. He was amongst the highest civil officers of the area and was also responsible for administrating the area from Aswan to Assiut. He was also the Steward of the Temple of Amun at Karnak and the mayor of Thebes #egypt #history #man #man #ancient #tomb #painting #paint #painter #artwork #work #art #learning #education #travelphotography #photo #photoshoot #photography #tourism #voyage #highlights #knowledge #knowledgeispower https://www.instagram.com/p/CTSdmkNIcms/?utm_medium=tumblr

#egypt#history#man#ancient#tomb#painting#paint#painter#artwork#work#art#learning#education#travelphotography#photo#photoshoot#photography#tourism#voyage#highlights#knowledge#knowledgeispower

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nubian with a Giraffe and a Monkey

New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1504-1425 BC.

Tomb of Rekhmire (TT100), Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sculptors at Work, Tomb of Rekhmire, ca. 1479–1425 B.C. New Kingdom. reign of Thutmose III–early Amenhotep II, tempera on Paper, by Nina de Garis Davies (1881–1965).

The original mural comes from Upper Egypt, Thebes, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Tomb of Rekhmire.

4 notes

·

View notes