#Transformers Synthesis Wars

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Eyeeees~

Uploading something while I work on other stuff for the fanfic, can you identify them all?

Edit: Wow, this thing kinda blew up, if you're interested, here are all the full versions of each face.

#transformers#maccadam#transformers animated#transformers g1#transformers prime#bumblebee#transformers go! go!#transformers cyberverse#transformers one#transformers war for cybertron#transformers wfc#transformers rescute bots academy#transformers live action#Transformers Synthesis Wars

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

2025 is Meliora’s 10th anniversary and I’m not going to be quiet about it.

Recently, I’ve been focusing a lot (…again 😅) on the cultural movements that inspired the entire Meliora era, especially Futurism.

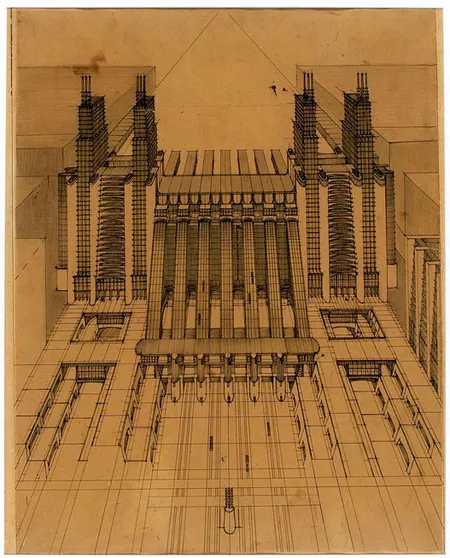

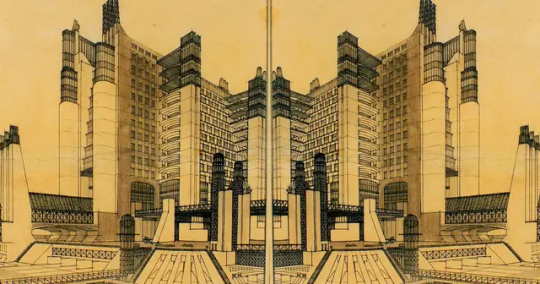

Knowing from Bishop Necropolitus Cracoviensis II that Terzo studied the Futurist manifestos during his formative years in Krakow (most likely Marinetti’s), I like to believe that the main inspiration for Meliora’s aesthetic came from the architectural drawings of Antonio Sant’Elia. The parallels between Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Antonio Sant’Elia with Terzo and Necropolitus are quite evident:

(...) We would sit down to studying exciting Futurist manifestos, sketched the blueprints of utopian metropoles, spiked with shiny skyscrapers stabbing at the heavens belly... Wantonly swollen zeppelins would to carry our gospel of indulgence to the farthest corners of the globe to summon and enslave.

BP Necropolitus

We had stayed up all night, my friends and I, under hanging mosque lamps with domes of filigreed brass, domes starred like our spirits, shining like them with the prisoned radiance of electric hearts. (…) Alone with stokers feeding the hellish fires of great ships, alone with the black spectres who grope in the red-hot bellies of locomotives launched on their crazy courses, alone with drunkards reeling like wounded birds along the city walls.

F.T. Marinetti - Manifesto of Futurism

Easy to imagine Terzo and Necropolitus—half stoned, half dazed, and inexorably intoxicated by a party that had been going on for hours—retracing, for the hundredth time, the highlights of the Futurist Manifestos they had read over and over, fervently discussing the future and the modernity they dreamed of bringing with his papacy.

Sant’Elia was a contemporary of Marinetti, fathers of the Futurist movement, and his Manifesto for Futurist architecture shares much of Terzo’s vision for Meliora, the city he created.

Each generation will have to build its own cities. Sant’Elia said.

that, just as the ancients drew their inspiration from natural elements, we – materially and spiritually artificial – must find our inspiration in the new mechanical world we have created, and our architecture must be its most beautiful expression, its most complete synthesis, its most effective integration; (…) by architecture, I mean the effort to freely and audaciously harmonise man with his environment, that is, to make the material world a direct projection of the spiritual world;

A. Sant’Elia - Manifesto of Futurist architecture

(...) Forged in nostalgia of steam and fire, this brave new world of ambition, vice, lust and greed - all so inherent to the enlightened modernity, was always with him through all these years.

BP Necropolitus

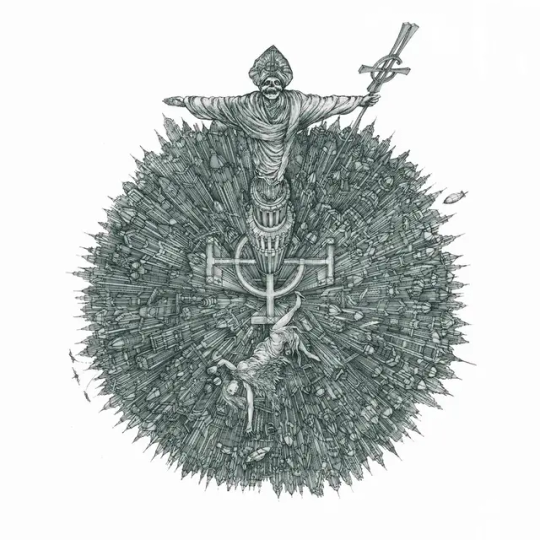

The Futurist movement embraced all forms of art, from painting and sculpture to architecture, music, and literature. It was characterized by a burning hatred for the past, which they wished to destroy, and a glorification of machinery, new technologies (we’re talking about first 20 years of 900), dynamism, speed, modernity, and rebellion. Nothing was meant to stay still, everything had to move, transform, evolve… very much in line with what Terzo seemed to believe.

But there was a downside. The original Italian Futurism became closely tied to fascism. It also celebrated violence and war, seen as tools to “clean up” and make space for the new. Most of the founding artists died in a war (World War I) that they had glorified and willingly taken part in. And when the dictator fell, so did the Futurist movement.

The lives of these artists were brief, but they remained true to their ideals, for better or worse, from beginning to end.

Erect on the summit of the world, once again we hurl defiance to the stars!

F.T. Marinetti - Manifesto of Futurism

At this point, I’d like to explore the association between the shapes in Futurist painting and the shapes of Terzo’s face paint, slipping swiftly into Cubism and Piet Mondrian’s simplification of form as a parallel to Terzo’s geometric, minimalist design… but that’s a story for another time.

#the band ghost#papa emeritus iii#terzo emeritus#bishop necropolitus cracoviensis ii#meliora#I love his era your honor I’ll never going to shut up about him#Happy anniversary Meliora

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ratchet Whump | Transformers: Prime

"I needed that!" IM BACK. 1x03 Darkness Rising Pt.3 - Attacked, saved, war veteran lore 1x04 Darkness Rising Pt.4 - Protected, attacked, pinned, weak, arm injured, arm brace 1x05 Darkness Rising Pt.5 - Optimus bromance 1x06 Masters & Students - Obsessive, angry 1x07 Scrapheap - Scared, attacked, eaten alive, weak, collapse 1x13 Sick Mind - Insane Optimus bromance/worried 1x14 Out of His Head - Punched, thrown/knocked unconscious 1x15 Shadowzone - Caught in explosion 1x22 Stronger, Faster - Injects himself, collapse unconscious, hyper/bloodthirsty, angry, rogue/reckless, gut punched, seriously bleeding, collapses, guilt 1x23 One Shall Fall - Desperate/angry

2x03 Orion Pax Pt.3 - Beaten, knocked down 2x05 Operation Bumblebee Pt.2 - Guilt, Bumblebee relationship lore, near T-Cog transplant, sedated, drowsy 2x14 Triage - Grouchy, screaming (Wheeljacks flying), crashlanding 2x26 Darkest Hour - Devastated x2

3x02 Scattered - Devastated 3x10 Minus One - Loud noise, scared, (presumed electrocuted offscreen) 3x11 Persuasion - Missing/captured, unconscious x2, restrained, electrocuted, blackmailed 3x12 Synthesis - Captured cont., chased, crushed x2, knocked down, thrown, beaten, bleeding 3x13 Deadlock - Thrown, knocked down x2, beaten (mostly offscreen)

#jeffrey combs#jeffrey combs whump#jeffrey combs character#ratchet#ratchet whump#transformers prime#transformers prime whump#ratchet transformers whump#ratchet transformers#transformers whump#whump#whump list#emotional whump#whumplist

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last year Hauser & Wirth presented several works by artist and activist Gustav Metzger for And Then Came the Environment at their downtown Los Angeles location. Metzger was an artist and an activist with strong concerns about environmental issues, ones that continue to this day. Works that address these issues are mixed with others that are explorations of science and technology including his use of liquid crystals before they became a common part of our technology, and the delightful energy of Dancing Tubes (videos of both below).

The press release provides more information on the exhibition and the artist’s history-

And Then Came the Environment presents a range of Metzger’s scientific works merging art and science from 1961 onward, highlighting his advocacy for environmental awareness and the possibilities for the transformation of society, as well as his latest experimental works, created in 2014. The exhibition title comes from Metzger’s groundbreaking 1992 essay Nature Demised wherein he proclaims an urgent need to redefine our understanding of nature in relation to the environment. Metzger explains that the politicized term ‘environment’ creates a disconnect from the natural world, manipulating public perception to obscure pollution and exploitation caused by wars and industrialization, and that it should be renamed Damaged Nature.

An early proponent of the ecology movement and an ardent activist, Gustav Metzger (1926–2017) was born in Nuremberg to Polish-Jewish parents, and fled Nazi Germany to England when he was 12 with his brother via the Kindertransport. While working as a gardener, he began his art studies in 1945 in war-embroiled Cambridge, a nexus for scientific experimentation and debate as the Atomic Age was dawning. By the late 1950s, Metzger was deeply involved in anti-nuclear protests and developed his manifestos on “auto-destructive” and “auto-creative” art. These powerful statements were aimed at “the integration of art with the advances of science and technology,” a synthesis that gained wide recognition in Europe in the 1960s through his exhibitions, lecture-demonstrations and writing.

Metzger’s quenchless curiosity about new materials and gadgets—from projectors and electronics to cholesteric liquid crystals and silicate minerals such as ‘mica’—led him to conduct experiments in and out of laboratories in collaboration with leading scientists in an effort to amplify the unpredictable beauty and uncertainty of materials in transformation: ‘the art of change, of movement, of growth.’ By the 1970s, increasingly concerned with ethical ramifications, Metzger became closely involved with the British Society for Social Responsibility in Science, raising awareness of ‘grotesque’ environmental degradation and social alienation and arguing for ‘old attitudes and new skills’ to bring science, technology, society and nature into harmony. He initiated itinerant projects to draw attention to the immense pollution caused by car emissions, a pursuit that gained momentum with his proposal for the first UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972 and was later partially realized in 2007 at the Sharjah Biennial.

The artworks on view in And Then Came the Environment reveal Metzger’s lifelong interest in drawing and gesture, presenting works on paper from the mid-1950s alongside models, installations and later, Light Drawings that underpin the artist’s desire for human interaction amidst the reliance on technology that continues to this day. Following his death, The Gustav Metzger Foundation was established to further Metzger’s work and carry on his legacy.

Exhibited for the first time in Los Angeles, works here include the earliest film documentation of Metzger’s bold chemical experiments on the South Bank in London (Auto-Destructive Art: The Activities of G. Metzger, directed by H. Liversidge, 1963); his first mechanized sculpture with Liquid Crystals—Earth from Space (1966)—and the stunning, large-scale projection, Liquid Crystal Environment (1966), one of the earliest public demonstrations of the material that makes Liquid Crystal Displays (LCDs), now omnipresent in our computer, telephone and watch screens.

And Then Came the Environment also presents Dancing Tubes (1968), an early kinetic project Metzger developed in the Filtration Laboratory of the University College of Swansea; various iterations of his projects against car pollution including the model Earth Minus Environment (1992); and the Light Drawing series (2014), using a plotter machine, a technology he first used in 1970, with fiber-optic light directed by air or hand.

The exhibition will be complemented by a new short film created by artist Justin Richburg, who animated Childish Gambino’s 2018 hit Feels like Summer, which references climate change. Richburg’s piece was inspired by and responds to Metzger’s 1992 essay Damaged Nature. The film represents the first time Metzger’s ideas have been directly expressed through a new medium, thus reflecting his interests in ongoing transformation and his conviction that younger generations were the most essential, urgent audiences for his work. In 2012, five years before his death at the age of 90, Metzger wrote:

“The future of the world is what we are after. We start with the young and then when the young are twelve, fifteen, and then twenty-one, they can enter politics, and if they have got this initiation/introduction to key issues … it will make an enormous difference to the future of the world.”

Below are videos from two of the most engaging works- Dancing Tubes and Liquid Crystal Environment.

youtube

For Gustav Metzger's Liquid Crystal Environment (1966/2024), five projectors each contain a single slide with liquid crystals that is projected through a heating and cooling system causing them to change form.

youtube

Also worth a read is Forbes’ article on the exhibition which provides additional background including Metzger’s influence on The Who’s Pete Townshend.

This exhibition was also part of The Getty’s PST ART: Art and Science Collide programming. On Saturday, 3/1, The Getty is hosting Open House at The Ebell in Los Angeles- “a free day-to-night exploration of science and art” that will include a pop-up art book fair from Printed Matter; panel discussions; a Doug Aitken multi-screen installation with a live performance by Icelandic musician Bjarki; a performance by Julianna Barwick, and more.

#Gustav Metzger#Hauser and Wirth#Hauser and Wirth Los Angeles#Art and Science#Los Angeles Art Shows#The Getty#PST ART#Los Angeles Art Show#Doug Aitken#Film and Video#Environmental Art#Julianna Barwick#Bjarki#Liquid Crystals#Los Angeles Events#Mixed Media Art#Music#Pete Townshend#Sculpture#DTLA#TBT#British Society for Social Responsibility in Science#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not yet gone

Rating: T

Quick Quote:

“Who reprogrammed you to serve me?”

“Explanation: A Hollis unit designated as C2-N2. He was the steward of your ship,” HK said, but he made an inarticulate noise as Eva came to her feet.

“C2. You saw C2. He programmed you?” Eva felt a flurry of wings inside her, like birds that were both startled and delighted by the appearance of bread crumbs. …but excitement on the inside did not translate to stability on the outside..

HK had to grab her by both arms to cease her wobbling on her feet. “Concern: Captain, your blood pressure is failing to recalibrate itself appropriately. I suggest resuming your previous position.”

“But you saw him? Talked to him?” Eva even tried to give the HK droid a little shake.

At first, as he had before, he stared at her blankly.

And then…

She felt the slightest squeeze of his right hand on her left bicep, and she figured the right mirrored it (not that she felt it). “Confirmation: I did. I did. He utilized a damaged datacore of an HK-51 unit –”

“Ah ha!” Triumphantly, Eva let the dizziness force her back down, leaving HK-55 standing there, miffed. “I’m not crazy. You are like Huck.”

“Denial: My personality board, affectation, and manner of speech synthesis are derivative of his coding, but C2-N2 did not make me an exact copy. I do not have his memories, nor do I pretend at having any knowledge of you beyond the personnel files that have circulated,” HK answered her. “Your childhood droid has not returned.” A pause, as if calculating the odds of negative impact. “Insistence: I will not answer to the name of ‘Huck,’ as it destabilizes your biosigns.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introducing the 2023 National Book Awards Longlists!

The National Book Foundation has officially announced the longlists for the 2023 National Book Awards! These are just a handful of the titles chosen for the nonfiction category. To see all of the titles selected, be sure to click here.

Fire Weather by John Vaillant

In May 2016, Fort McMurray, the hub of Canada’s oil industry and America’s biggest foreign supplier, was overrun by wildfire. The multi-billion-dollar disaster melted vehicles, turned entire neighborhoods into firebombs, and drove 88,000 people from their homes in a single afternoon. Through the lens of this apocalyptic conflagration—the wildfire equivalent of Hurricane Katrina—John Vaillant warns that this was not a unique event, but a shocking preview of what we must prepare for in a hotter, more flammable world.

Fire has been a partner in our evolution for hundreds of millennia, shaping culture, civilization, and, very likely, our brains. Fire has enabled us to cook our food, defend and heat our homes, and power the machines that drive our titanic economy. Yet this volatile energy source has always threatened to elude our control, and in our new age of intensifying climate change, we are seeing its destructive power unleashed in previously unimaginable ways.

With masterly prose and a cinematic eye, Vaillant takes us on a riveting journey through the intertwined histories of North America’s oil industry and the birth of climate science, to the unprecedented devastation wrought by modern forest fires, and into lives forever changed by these disasters. John Vaillant’s urgent work is a book for—and from—our new century of fire, which has only just begun.

I Saw Death Coming by Kidada E. Williams

The story of Reconstruction is often told from the perspective of the politicians, generals, and journalists whose accounts claim an outsized place in collective memory. But this pivotal era looked very different to African Americans in the South transitioning from bondage to freedom after 1865. They were besieged by a campaign of white supremacist violence that persisted through the 1880s and beyond. For too long, their lived experiences have been sidelined, impoverishing our understanding of the obstacles post–Civil War Black families faced, their inspiring determination to survive, and the physical and emotional scars they bore because of it.

In I Saw Death Coming, Kidada E. Williams offers a breakthrough account of the much-debated Reconstruction period, transporting readers into the daily existence of formerly enslaved people building hope-filled new lives. Drawing on overlooked sources and bold new readings of the archives, Williams offers a revelatory and, in some cases, minute-by-minute record of nighttime raids and Ku Klux Klan strikes. And she deploys cutting-edge scholarship on trauma to consider how the effects of these attacks would linger for decades—indeed, generations—to come.

For readers of Carol Anderson, Tiya Miles, and Clint Smith, I Saw Death Coming is an indelible and essential book that speaks to some of the most pressing questions of our times.

The Rediscovery of America by Ned Blackhawk

The most enduring feature of U.S. history is the presence of Native Americans, yet most histories focus on Europeans and their descendants. This long practice of ignoring Indigenous history is changing, however, with a new generation of scholars insisting that any full American history address the struggle, survival, and resurgence of American Indian nations. Indigenous history is essential to understanding the evolution of modern America.

Ned Blackhawk interweaves five centuries of Native and non‑Native histories, from Spanish colonial exploration to the rise of Native American self-determination in the late twentieth century. In this transformative synthesis he shows that:

• European colonization in the 1600s was never a predetermined success; • Native nations helped shape England’s crisis of empire; • the first shots of the American Revolution were prompted by Indian affairs in the interior; • California Indians targeted by federally funded militias were among the first casualties of the Civil War; • the Union victory forever recalibrated Native communities across the West; • twentieth-century reservation activists refashioned American law and policy.

Blackhawk’s retelling of U.S. history acknowledges the enduring power, agency, and survival of Indigenous peoples, yielding a truer account of the United States and revealing anew the varied meanings of America.

King: A Life by Jonathan Eig

Vividly written and exhaustively researched, Jonathan Eig’s A Life is the first major biography in decades of the civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr.―and the first to include recently declassified FBI files. In this revelatory new portrait of the preacher and activist who shook the world, the bestselling biographer gives us an intimate view of the courageous and often emotionally troubled human being who demanded peaceful protest for his movement but was rarely at peace with himself. He casts fresh light on the King family’s origins as well as MLK’s complex relationships with his wife, father, and fellow activists. King reveals a minister wrestling with his own human frailties and dark moods, a citizen hunted by his own government, and a man determined to fight for justice even if it proved to be a fight to the death. As he follows MLK from the classroom to the pulpit to the streets of Birmingham, Selma, and Memphis, Eig dramatically re-creates the journey of a man who recast American race relations and became our only modern-day founding father―as well as the nation’s most mourned martyr.

When Crack Was King by Donovan X. Ramsey

The crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s is arguably the least examined crisis in American history. Beginning with the myths inspired by Reagan’s war on drugs, journalist Donovan X. Ramsey’s exacting analysis traces the path from the last triumphs of the Civil Rights Movement to the devastating realities we live with a racist criminal justice system, continued mass incarceration and gentrification, and increased police brutality.

When Crack Was King follows four individuals to give us a startling portrait of crack’s destruction and devastating Elgin Swift, an archetype of American industry and ambition and the son of a crack-addicted father who turned their home into a “crack house”; Lennie Woodley, a former crack addict and sex worker; Kurt Schmoke, the longtime mayor of Baltimore and an early advocate of decriminalization; and Shawn McCray, community activist, basketball prodigy, and a founding member of the Zoo Crew, Newark’s most legendary group of drug traffickers.

Weaving together riveting research with the voices of survivors, When Crack Was King is a crucial reevaluation of the era and a powerful argument for providing historically violated communities with the resources they deserve.

#national book award#nonfiction books#nonfiction#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Valentine's Day!

Here's a commission I asked to the wonderful Kai Raccoon! It isn't Valentine theme, but meeeeeeeeh

I need to continue drawing Lillian in all the versions Optimus has

#transformers#maccadam#optimus prime#transformers one#OptiLily#optimus x oc#Transformers Synthesis Wars#TFSW

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

“One of the most influential of the post-Soviet books was the Princeton historian Stephen Kotkin’s “Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization” (1995), a study of the steel city of Magnitogorsk, the U.S.S.R.’s answer to Pittsburgh, as it was constructed in the shadow of the Ural Mountains in the early nineteen-thirties. The book was a sharp-elbowed intervention in the decades-old debate between “totalitarian” historians, who saw in the Soviet Union an omnipotent state imposing its will on a defenseless populace, and “revisionist” historians, who saw a more dynamic and fluid society, with some portion of the population actually supporting the regime. Kotkin’s synthesis was influenced by the philosopher Michel Foucault, who spent several semesters at Berkeley, where Kotkin was a graduate student. Foucault had argued that power did not reside exclusively or even primarily with the state but was disseminated like a web over a society’s institutions. This insight, applied to the Stalinist era, was transformative. Yes, the regime tried to impose its will and its ideas on the population, as the totalitarians had claimed; but also, as the revisionists had counter-claimed, the population was an active participant in and interpreter of this project. With its attention to everyday life, “Magnetic Mountain” was revisionist in form; with its emphasis on ideology (Kotkin’s other influence was Martin Malia, the intellectual historian and ardent cold warrior), it was totalitarian in content. The key theoretical concept was “speaking Bolshevik,” by which Kotkin meant not only the rote language people used to navigate the bureaucracy but also the more evocative language—of “shock work,” “capitalist encirclement,” and, above all, “building socialism”—that people increasingly used to understand themselves and their lives.

Two decades later, Kotkin has seemingly reversed field and produced . . . a Stalin biography. Entering a crowded marketplace, the book makes its mark through its theoretical sophistication, relentless argumentation, and sheer Stakhanovite immensity: two volumes and two thousand closely printed pages in, we’re only up to 1941. (A projected third volume should take us through the war and to Stalin’s death, in 1953.) Kotkin also attempts to answer the chief philosophical question about Stalin: whether the monstrous regime he created was a function of his personality or of something inherent in Bolshevism.

(…)

Kotkin’s first volume, “Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928,” published three years ago, situated the Soviet experiment amid the broad sweep of European history. The revolution was a Russian phenomenon, yes; but it was also a response to the forms of mass politics and total war that shook Europe in the first two decades of the twentieth century. By reducing the Russian Empire to near-starvation, the First World War created the opportunity for the Bolsheviks to seize power. But Kotkin makes clear that the war’s slaughter fields also confirmed the Bolshevik view that the capitalist-imperialist system was plunging the world into suicide—and lowered the price, in everyone’s eyes, of human life.

(…)

A key argument in “Paradoxes of Power” revolved around Stalin’s relationship to Lenin. Stalin played an important but secondary role in the October Revolution; the starring roles were unquestionably Lenin’s and Trotsky’s. Lenin was a brilliant, once-in-a-generation strategist, tacking right when others tacked left, attacking when they retreated, always keeping his end goal in view. Trotsky was a magnificent orator, one of the best propagandistic writers of the twentieth century, and completely fearless. He led the Petrograd Soviet—the representative body for the workers and soldiers of the empire’s capital—in the crucial months before the revolution, and then built from scratch the Red Army that won the civil war. Kotkin argues that a leftist revolution of one kind or another was likely to take place in Russia in 1917, but there did not have to be two of them, and the second did not have to be of the radical Communist variety. “The Bolshevik putsch could have been prevented by a pair of bullets,” Kotkin writes: one each for Lenin and Trotsky. None for Stalin. And this is Stalin’s biographer!

Still, when it came time to build a mass party that could administer a powerful state, Lenin found himself depending more and more on Stalin. It turned out that Stalin had a genius for management—for setting up clear lines of authority and for inspiring and organizing people. Anyone who’s ever spent any time around leftist revolutionaries, or just members of a fractious community garden, will recognize how valuable such skills might be. In 1922, Lenin created a new post expressly for Stalin: General Secretary of the Communist Party.

But doubts about their relationship would haunt Stalin throughout his rule. His critics, led by Trotsky, never tired of reminding him of his secondary role in the Bolshevik Revolution. They also never let him forget a document that Lenin drafted in late 1922 and early 1923, shortly before he became incapacitated by his third stroke, in which he urged that Stalin be removed from his post. “Comrade Stalin,” Lenin wrote, or dictated, “having become General-Secretary, has concentrated boundless power in his hands, and I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution.” In an addendum to the letter, apparently after an incident in which Stalin chewed out Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin was more categorical: “Stalin is too rude, and this defect, although quite tolerable in our midst and in dealing among us Communists, becomes intolerable in a General-Secretary.” Lenin hoped his letter would be read aloud at the next Party Congress. Instead, it was read in small group sessions, where it could be more easily controlled, and not published in the Soviet Union until after Stalin’s death.

Here again the opinionated Kotkin enters the arena. The testament is a key document not only because of its dramatic nature—Lenin, on his deathbed, rejecting Stalin—but because it seems to address one of the central questions about the revolution: Did it lead inexorably to Stalin? If the answer is yes, that tells you all you need to know about this revolution. If the answer is no—if there were other, more humane and democratic paths for the revolution to take—then the whole question requires more thought.

Kotkin’s answer is twofold. The first is to allege that the testament was a forgery cooked up by Krupskaya. Kotkin believes that Lenin was too incapacitated to have composed the document in any legitimate way. Krupskaya must have interpreted it, as one would a Ouija board. This was the one claim in the first volume that really rankled other historians. Some of them pointed out that the recent Russian originator of the testament-forgery thesis, on whose work Kotkin relied, was an unapologetic Stalinist. For a historian who prizes evidence as much as Kotkin does, it seemed an unnecessarily extravagant claim. The pugnacious Kotkin has not backed down, however; in Volume II, the testament appears again as “Lenin’s supposed testament.”

But Kotkin has a second and more convincing answer to the question of the succession: Stalin was, quite simply, the man most qualified for the job. Trotsky claimed that Stalin was adept at manipulating the bureaucracy, and meant this as an insult. In fact, these were the skills necessary to govern a modern state, and they explain why Stalin had already won so much power while Lenin still lived. Trotsky did not have the talent for the dull work of administration. Even in exile, he was constantly undermining his allies and arguing with his friends. In Kotkin’s unsentimental appraisal, Trotsky was “just not the leader people thought he was, or that Stalin turned out to be.”

(…)

A distinguished previous biographer, Robert C. Tucker, once confessed to fantasizing that one of Stalin’s comrades would assassinate the Great Leader: “Sometimes in the quiet of my study I have found myself bursting out to their ghosts: ‘For God’s sake, stab him with a knife, or pick up a heavy object and bash his brains out, the lives you save may include your own!’ ” In the nineteen-twenties, assassination wouldn’t have been necessary; a concerted effort by Stalin’s opponents, especially with Lenin’s testament in their pockets, could easily have unseated him. They were too timid to do it, but also, Kotkin concludes, they just didn’t realize what Stalin would become. They had had some intimations: they knew he could be rude, and they even knew he could be psychologically cruel. During his Siberian exile, he had briefly lived with Yakov (Yashka) Sverdlov, a fellow-Bolshevik and later the titular head of the Soviet government, but the two broke up house because Stalin refused to do the dishes and also because he had acquired a dog and started calling him Yashka. “Of course for Sverdlov that wasn’t pleasant,” Stalin later admitted. “He was Yashka and the dog was Yashka.” More significant was Stalin’s activity during the civil war. When he went to the city of Tsaritsyn (later renamed Stalingrad), on the Southern Front, to try to turn the tide for the Bolsheviks, he immediately caused a mess by fighting with the tsarist-era officers who were saving the Red Army from defeat, and then pursuing (and executing) supposed enemies of the people.

And yet Stalin’s fellow-Bolsheviks couldn’t see whom they were dealing with. During the period of collective leadership that followed Lenin’s death, one group allied with Stalin to oust Trotsky; the next allied with Stalin to oust the first group. And so on. There could indeed have been another path for the Bolshevik Revolution: the very naïveté, idealism, and lack of guile demonstrated by so many of the Old Bolsheviks remains a testament to their decency. Kotkin proposes a series of interlocking arguments to explain the Stalinist outcome: the conspiratorial rigidity of Bolshevism; the state’s total domination of life in the absence of private property; the peculiar personality of Stalin; and the pressures of geopolitics. An attempt by very determined people to carry out radical change in a huge country was never going to be without bloodshed. And the worldwide financial crisis and the instability in Europe were going to make for a difficult decade, no matter what. But nothing foreordained the extent of the violence.

Kotkin’s first volume closed in 1928, with Stalin, having consolidated his power, making a rare trip to Siberia to launch what would become his war against the peasants. The second volume, “Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941,” opens in the same place. But something has happened in between. The Stalin of the first volume was reacting to external stimuli, in a more or less reasonable manner. The Stalin of the second volume has lost his mind, and is fully in control.

(…)

The tragedy of Stalin’s agricultural collectivization unfolded in stages. In the summer of 1929, more than twenty-five thousand “politically literate” young Bolsheviks fanned out from Moscow to the nation’s rural areas, charged with setting up the new collectives. In the villages, they encountered fierce resistance. Most peasants had no wish to give up their livestock and be herded to giant farms; they began, en masse, to slaughter their livestock and eat it. When Bolsheviks came to demand their grain, the peasants shot them—more than a thousand were killed in 1930 alone. In some ways, this resembled the back-to-the-people movement of the nineteenth century, in which young progressives had been sent to the countryside to be with “the people,” and the people had rejected them.

But this time the progressives returned with machine guns. The so-called kulaks were arrested and exiled, and sometimes shot. Their property was confiscated. Then the definition of “kulak” expanded. There were not two million well-off farmers in the impoverished U.S.S.R. in the late twenties. And yet that’s how many were arrested for being such. By the end of collectivization, five million people had been “dekulakized.”

The slaughter of livestock, the mass arrests, and the requisition of vast quantities of grain led, inevitably, to shortages. A cold spring and a dry summer in 1931 meant disaster. Local and regional bosses pleaded with Stalin to relax the grain-requisitioning quotas, but he was stinting about it; he believed that the peasants were holding out on him. Long after all the grain had been beaten and tortured from them, Stalin still thought that they had hidden reserves. People began to starve. When they tried to leave their villages and head for the cities, where the grain that had been taken from them was turned into bread, they were blocked by armed detachments; when they tried to break into the government silos where their requisitioned grain was kept, they were shot. Parents ate their children. Before it was over, between five and seven million people would die of starvation and disease. Nearly four million of those deaths were in Ukraine, where the famine was accompanied by arrests and executions of the nationalist intelligentsia; more than a million were in sparsely populated Kazakhstan, whose traditionally nomadic farmers were annihilated. Given the destruction in Kazakhstan, Kotkin rejects out of hand the argument that the famine was specifically Ukrainian. “The famine was Soviet,” he writes. But he does not underestimate the catastrophe. The huge loss of life, during peacetime, destabilized the country, and the Party. For the first time, there was serious criticism of Stalin in the Party ranks, and talk of removing him. By then, it was too late.

Kotkin’s Stalin is a workaholic. He is a tireless reader, not just of books but of the endless reports he receives from his ministries and deputies and, most of all, from his secret police. Kotkin compares him favorably with the hedonistic Mussolini and the late-sleeping Hitler. The Führer’s hands-off tyranny has led to a historians’ debate about his actual participation in the crimes of his regime, and to Ian Kershaw’s famous concept of “working towards the Führer”; that is, anticipating his wishes in the absence of direct orders. No such confusion can exist with Stalin. “One comes away flabbergasted,” Kotkin writes, “by the quantity of information he managed to command and the number of spheres in which he intervened.” Stalin adjusted the grain quotas during collectivization, or refused to; he read novels, attended plays, suggested changes to new films; and he edited the interrogation protocols of accused enemies of the people, adding, deleting, urging further lines of questioning as well as methods for getting answers (“Beat Unshlikht for not naming the Polish agents for each region”).

(…)

Kotkin walks us to the threshold of Stalin’s Terror slowly. It had no single cause; the causes were cumulative. There was the stress, throughout the nineteen-twenties, over Lenin’s testament. There was the calamity of collectivization and the opposition it engendered inside the Party. There was the suicide of Stalin’s wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, in 1932, and then the assassination of his close friend Sergei Kirov, the young Party boss of Leningrad, by a deranged former Communist, in 1934. There was the fact that Trotsky, exiled since 1929, remained a popular figure among the Spanish Communists fighting in that country’s civil war.

Most significant, from Stalin’s perspective, was that he really did have critics within the Party. He had critics because he was not Lenin. He had not almost single-handedly built a revolutionary party and then led it to power in the world’s largest country. And he made mistakes. He urged the Red Army to capture Lwów in 1920, contributing to the loss of Poland; he urged the Chinese Communists to ally with the Nationalists, resulting in thousands dead; most fatefully, he refused to allow European Communist parties to ally with social democrats—a decision that helped propel Adolf Hitler to power. As Kotkin points out, “In no free and fair election did the Nazis ever win more votes than the Communists and Social Democrats combined.”

On top of all these failures was the sheer, maddening difficulty of governing such a huge country. Kotkin’s Stalin is obsessed with statecraft. He continues to read Lenin, arguing with him in his mind. He is the ruler of a vast, nominally socialist empire, but none of the socialist sages have much advice for him—none had thought beyond the revolution. How is he to make sure that he is obeyed? How to make sure that his subjects are loyal? How to keep the state from being taken over (as Trotsky said had happened) by an entrenched, self-seeking bureaucracy?

(…)

Those arrested were then tortured: forced to remain standing for days on end; beaten with fists, sticks, lamps. Their eyes were gouged out and their eardrums punctured. Some died from these beatings or were crippled; others were shot afterward. Some survived and entered the Gulag. The best known of the Bolshevik higher-ups were subjected to grotesque public trials, the transcripts of which were duly translated and circulated around the world. Western leftists racked their brains to figure out why the Old Bolsheviks confessed to crimes they could not possibly have committed. Arthur Koestler, in his novel “Darkness at Noon” (1940), depicted an old revolutionary who decides to confess as a final service to the revolution. In some cases, this impulse may have played a part: Kotkin describes how Lev Kamenev, Stalin’s old Pravda co-editor, and Grigory Zinoviev, who with Stalin and Kamenev had formed a ruling troika during Lenin’s final illness, were dragged out of their prison cells in 1936 for a meeting with Stalin; he urged them to confess, for old times’ sake. But they were also aware that their families were being arrested, and must have hoped to spare them.

The first phase of the Terror was seen by some as an intra-Party affair. Farmers who had been forced off their land by commissars shed no tears when they saw those commissars being arrested. The Terror soon dramatically expanded, however. One of the genuine shocks in the archives was the discovery of N.K.V.D. order No. 00447, from July 1937, “On the operation for the repression of former kulaks, criminals, and other anti-Soviet elements.” In three neat columns, the order set quotas for executions and imprisonments by region (the third column gave the total). Four thousand to be shot in the Sverdlovsk region, six thousand to be sent to prison or to the Gulag. One thousand to be shot and thirty-five hundred imprisoned in the Odessa region. Local authorities could and did ask that these numbers be increased; the original order set executions at seventy-five thousand nine hundred and fifty, but this was eventually increased to three hundred and fifty-six thousand one hundred and five. In fact, the number shot under the order was closer to four hundred thousand. That same summer of 1937, the N.K.V.D. issued a series of orders against ethnic communities in the U.S.S.R. that were thought to be vulnerable to entreaties from the country’s enemies. Ethnic Germans and Poles bore the brunt of this, again in the hundreds of thousands. These two “operations”—targeting anti-kulak/anti-Soviet persons and the “nationalities”—made up the bulk of the million and a half arrests and nearly seven hundred thousand executions carried out in 1937 and 1938.

What was Stalin thinking? Could he possibly have believed that he had this many enemies or that his old friends were all British spies? No one knows. But Kotkin refers repeatedly to Stalin’s editing of the interrogation transcripts, which he then circulated to members of his inner circle. Apparently, Stalin was trying to make a point: he had been warning of spies in their midst, and now here was proof. He made certain that the others were up to their elbows in blood, just as he was. He would solicit their opinions; they would call for executions, as they knew they were expected to. When anyone asked for the highest measure, Stalin would inevitably approve. Here is a typical telegram from Stalin to one of his associates, from July, 1937:

J.V. Stalin to A.A. Andreev in Saratov

The Central Committee agrees with your proposal to bring to court and shoot the former workers of the Machine Tractor Stations.

Stalin

Vyacheslav Molotov, now Stalin’s faithful henchman, later said of the purges, “It is doubtful that these people were spies, but they were connected with spies, and the main thing is that in the decisive moment there was no relying on them.” The suspiciousness of the regime was a murderous projection of its own self-criticism. The more tyrannical Stalin became, the more people had cause to doubt him, and the more likely it became that they would abandon him. Stalin had to keep the killing going because otherwise he would never be secure.

The numbers are hard to fathom. According to the best current estimates, Stalin was responsible for between ten and twelve million peacetime deaths, including victims of the famine. But the most hands-on period of killing was the Terror of 1937 and 1938. At its height, fifteen hundred people were being shot every day. Most of the victims were ordinary citizens, caught up in a machine that was seeking to meet its quotas. But the Communist Party, too, was devastated—in many provinces, first secretaries, second secretaries, third secretaries all gone. Entire editorial staffs were erased. The officer corps of the Army was devastated. Five hundred of the top seven hundred and sixty-seven commanders were arrested or executed; thirteen of the top fifteen generals. “What great power has ever executed 90 percent of its top military officers?” Kotkin asks. “What regime, in doing so, could expect to survive?” Yet this one did. Kotkin, like Tucker before him, finds himself fantasizing about someone assassinating Stalin. No one dared. They feared for their lives, of course, but it was also in the nature of the Terror that people hoped, until it was too late, that the wave would pass them by. Those who survived the Gulag described how Communist inmates were always sure that others were guilty, that they alone were innocent. At night in the cells, they dreamed of Stalin—of meeting the leader and convincing him of their innocence.

The Terror, which had started in early 1937, ended in the fall of 1938, with the removal of the head of the N.K.V.D., Nikolai Yezhov. He was blamed for “excesses,” and eventually executed. Some of the people who’d been arrested were now released. The interrogators beat Yezhov’s underlings into confessing that he had ordered them to beat confessions out of others. And the secret police kept arresting and killing people; Isaac Babel, for example, was arrested in May, 1939, and shot eight months later.

In addition to everything else the Terror did, it greatly weakened the country’s international position. Stalin’s justified fear of the coming war made this war only more likely. The French and the British, contemplating a stand against Hitler over Czechoslovakia in 1938, did not feel they could count on the now depleted Red Army. Worse still, the Terror made Stalin an unacceptable ally for the British in 1939. Kotkin shows that Stalin’s first choice in the months before the war was not Hitler but Chamberlain. He sent detailed terms to Britain for a military alliance. Chamberlain was not interested, and Kotkin, refusing the benefits of hindsight, doesn’t blame him. Stalin had just murdered hundreds of thousands of his own citizens, staged show trials of his former comrades, and carried out purges of putative socialist allies in Spain. Hitler would eventually overtake him, but as of 1939 Stalin had killed more people by far. He was, as Kotkin says, “an exceedingly awkward potential partner for the Western powers.” And then, on top of all the killing, the Soviets were also socialists who had repudiated tsarist-era debts.

(…)

He trusted no one, including his spies. When, in May, 1941—just six weeks before the invasion—Pavel Fitin, the head of N.K.V.D. foreign intelligence, brought him the most credible reports to date that the invasion was on its way, Stalin blew up. “You can send your ‘source’ from the headquarters of German aviation to his fucking mother,” he shouted. “This is not a source but a disinformationist.” The fact that Stalin had executed so many of his previous intelligence chiefs—in the case of military intelligence, the last five—did not encourage his intelligence officials to talk back. As Fitin, who later organized the spy network that infiltrated the Manhattan Project, remarked of Stalin’s blowup, “Despite our deep knowledge and firm intention to defend our point of view on the material received by the intelligence directorate, we were in an agitated state. This was the Leader of the Party and country with unimpeachable authority. And it could happen that something did not please Stalin or he saw an oversight on our part, and any one of us could end up in a very unenviable situation.”

This is the standard narrative of the months leading up to the invasion, and, once again, Kotkin helpfully complicates it. For one thing, in addition to the accurate warnings, Stalin was also receiving inaccurate ones, many of them placed there deliberately by the Germans. The most effective lie—because it was the one Stalin most wanted to believe—was that the German troop buildup at the border was a bluff that would culminate in an ultimatum from Hitler, perhaps for a long-term “lease” of Ukraine. Stalin could then stall for time. That his officer corps was not yet ready was no secret to Stalin. Even the longtime loyalist Kliment Voroshilov—Stalin’s minister of defense and an enthusiastic participant in the purges—had yelled at him, in the aftermath of the disappointing Finnish campaign of the year before, “You’re to blame for this! You annihilated the military cadres.”

Kotkin also points out that, in fact, a major mobilization of Soviet forces had taken place throughout 1941. There were nearly three million troops on the western border—a fearsome defense, but vulnerable. Stalin was afraid that Hitler would use the slightest pretext to launch an invasion, and warned his forces to do nothing provocative. Hitler, of course, was going to launch an invasion anyway. Stalin’s morbid suspiciousness and lack of scruples had kept the country out of the European war for almost two years—two years more than Tsar Nicholas II had managed with the previous war. But now time was up.

Kotkin’s second volume ends in Stalin’s office in the Kremlin on June 21, 1941, a Saturday, the eve of the German invasion. His two top commanders—Semyon Timoshenko and Giorgy Zhukov—deliver their assessment, based on the testimony of a German defector in the frontier district, that an invasion is truly imminent. Stalin is skeptical, but in Timoshenko and Zhukov, after the bloodletting at the top of the armed forces, he has finally found capable people whom he can trust. He allows them to issue an order for frontier troops to man their battle stations and disperse the Soviet Air Force away from the border.

The order was too late. By the time it went out, German saboteurs (real ones) had crossed the front lines and cut off communications. Most frontier officers heard nothing. Many would die that night in their beds. The Soviet Air Force was destroyed on the ground. In the next few months, the Germans would kill or capture much of the Soviet Army, gobble up most of Ukraine, lay siege to Leningrad, and approach Moscow. In the territories that they captured, which included most of the old Pale of Settlement, the Einsatzgruppen would begin the mass murder of Europe’s Jews. It had been a terrible decade that saw famine kill millions, and their countrymen enslave, imprison, torture, and murder millions more. But for Stalin, and for most of the people who lived in his empire, the worst was yet to come.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

German Kitchens and the Art of Functional Beauty in Interior Design

Interior design, as a discipline, seeks harmony between aesthetics and usability. A beautifully designed space that neglects utility may appear visually pleasing, yet it fails in delivering long-term satisfaction. Functional beauty refers to design choices that serve practical purposes while retaining visual sophistication. Nowhere is this philosophy more vividly realized than in the kitchen, a room where form and function must align to support everyday life. Among the many approaches to kitchen design, German kitchens stand out for their meticulous integration of utility and elegance. This synthesis of purpose and appearance makes them paragons of functional beauty.

Historically, German design has leaned toward minimalism, precision, and engineering excellence. These qualities translate seamlessly into kitchen architecture. The result is an environment where every drawer, cabinet, and appliance operates with intentionality. Beauty is not an afterthought but emerges naturally from logical arrangement and material integrity. This ethos does more than make a kitchen visually appealing; it transforms the space into a practical tool for living. As lifestyles become more dynamic and kitchens increasingly serve multiple roles, from cooking to socializing, the value of such intelligent design cannot be overstated.

The Philosophical Foundations of German Kitchen Design

The roots of German kitchen design can be traced back to a broader cultural commitment to structure and order. Post-World War II reconstruction and the economic miracle period led to an emphasis on rebuilding with discipline and foresight. Industrial design flourished in this climate, characterized by clean lines, efficient forms, and a preference for durability. These principles gradually migrated into domestic interiors, especially kitchens. The modern German kitchen emerged not as an artistic indulgence but as a rational response to modern living.

Functional zoning is a cornerstone of this design tradition. Every aspect of the layout is meticulously planned to reduce unnecessary movement and optimize workflow. The "work triangle"—the spatial relationship between the stove, sink, and refrigerator—is refined into a highly efficient matrix. Additionally, storage is not merely about volume but about access and organization. Drawers pull out silently and fully; corners are utilized through innovative mechanisms. These details demonstrate how function is elevated to an aesthetic principle. The result is a kitchen that feels natural and intuitive, qualities that enhance both its beauty and usability.

Engineering Precision Meets Everyday Use

What distinguishes German kitchens from many other design traditions is the engineering mindset behind their creation. Manufacturers approach kitchen design with the same rigor applied to automotive or industrial products. Tolerances are exacting, materials are tested for resilience, and systems are designed for longevity. This scientific approach results in kitchen environments that maintain their integrity over decades, both structurally and visually.

Materials are carefully selected for their performance under stress. Laminates, metals, and engineered wood products are treated to withstand heat, moisture, and wear. Finishes resist fingerprints, while hinges and drawer slides undergo thousands of test cycles. These technical features are not visible at first glance, but they contribute significantly to the overall user experience. Reliability becomes a form of beauty, a sense that everything simply works as it should. In this way, German kitchens extend the notion of craftsmanship beyond surface details to the unseen mechanisms that support daily use.

Spatial Efficiency as a Design Ethic

In many urban environments, space is at a premium. The German approach to kitchen design addresses this challenge not by reducing functionality, but by enhancing it through smarter organization. Every inch of the kitchen is considered valuable, and no space is left unutilized. Tall cabinets reach to the ceiling, plinth drawers offer hidden storage, and integrated appliances conserve counter space. Even the alignment of cabinet fronts is planned to maintain visual coherence.

This efficiency does not imply austerity. On the contrary, it allows for greater personalization and comfort. With clutter removed and storage optimized, users experience a sense of calm and control. Surfaces are kept clear, enabling the kitchen to adapt to different activities—preparing meals, hosting friends, or even remote work. The ability to transition seamlessly between these roles is a hallmark of functional beauty. German kitchens exemplify how intelligent planning can produce spaces that feel more expansive and adaptable than their dimensions might suggest.

Aesthetic Discipline and Material Integrity

A key element in the visual appeal of German kitchens lies in their restraint. Designers often favor neutral palettes—whites, grays, and natural wood tones—that serve as a backdrop rather than a focal point. This allows the form and texture of materials to take precedence over decorative embellishments. The absence of visual noise helps to highlight the clarity of design and the harmony of proportions.

Material integrity plays a crucial role in achieving this aesthetic. Surfaces are selected not only for their durability but for their visual coherence. Natural stone, engineered composites, matte lacquers, and brushed metals are used to convey a sense of quality and consistency. These materials age gracefully, developing character without losing their elegance. In this way, the kitchen becomes not just a functional space but a reflection of enduring values. Rather than chase trends, German kitchens invest in a timeless look grounded in structural honesty and material excellence.

The Social Role of the Kitchen in Contemporary Living

The kitchen has evolved from a utilitarian zone into a central hub of the home. In contemporary living, it serves as a place for cooking, dining, conversation, and even work. German kitchen design accommodates this shift by incorporating multi-functional elements that support diverse uses. Islands often double as dining tables, breakfast bars, or workstations. Lighting is zoned to create different moods, while acoustics are managed to reduce noise and enhance comfort.

Furniture-like cabinetry and integrated technology further blur the boundaries between kitchen and living spaces. Sliding panels conceal appliances when not in use, allowing the kitchen to maintain a clean and cohesive look. This flexibility is not merely cosmetic; it reflects an understanding of how people live today. The design supports spontaneous gatherings, quiet evenings, and everything in between. In doing so, it elevates the kitchen from a workspace to a social environment, reinforcing the concept of functional beauty through its adaptability.

The Role of Customization and Modularity

Another strength of German kitchen design lies in its embrace of customization. While the aesthetic principles remain consistent—clarity, precision, material integrity—each kitchen is tailored to the user's specific needs. Modular systems allow components to be arranged in numerous configurations, accommodating different room sizes, habits, and ergonomic preferences. This personalization ensures that the kitchen not only fits the space but also aligns with the lifestyle of its inhabitants.

Customization extends to finishes, handles, lighting, and organizational inserts. Users can choose layouts that prioritize cooking, storage, or social interaction. Advanced planning software allows designers and clients to visualize different options in real-time, ensuring that form and function evolve together. This user-centric approach exemplifies functional beauty by prioritizing the daily experience of the space. The kitchen is not a static design statement but a living environment, continually shaped by the rhythms of life.

Influence of German Kitchens on Global Design Trends

The principles that define German kitchen design have had a significant impact on international interior design. Elements such as handle-less cabinetry, integrated appliances, and modular layouts are now standard features in high-end kitchens worldwide. These trends can be traced back to the German emphasis on efficiency, precision, and visual clarity. As more homeowners seek spaces that combine luxury with logic, the appeal of this design philosophy continues to grow.

Designers across the globe now look to German manufacturers for inspiration and innovation. The export of these ideas has helped elevate the global perception of kitchen design from a purely functional undertaking to a sophisticated design discipline. Through trade shows, publications, and digital platforms, the aesthetics and methodologies of German kitchens have entered mainstream consciousness. This international influence underscores the universal relevance of functional beauty. It also challenges other design traditions to rethink their approach to utility and elegance.

Intersecting with Broader Movements in Modern European Kitchens

German kitchens do not exist in isolation. They are part of a broader movement that includes the growing popularity of modern European kitchens. This shared design ethos values simplicity, cohesion, and quality craftsmanship. While national styles differ in execution—Italian kitchens may emphasize flair and artisanal touches, for instance—the underlying goals are often similar: to create spaces that are as efficient as they are beautiful.

The convergence of these styles is leading to a more unified European design language in domestic interiors. This fusion respects regional differences while promoting shared values such as sustainability, material integrity, and user-focused planning. German kitchens contribute to this dialogue by providing a model of what can be achieved when function is treated as a form of beauty. Their influence helps raise the standard for kitchen design across the continent and beyond.

The Value of Kitchen Catalogs in Design Planning

For homeowners embarking on a kitchen renovation, access to high-quality kitchen catalogs can be an invaluable resource. These catalogs serve not merely as promotional tools but as educational guides that outline the possibilities of modern kitchen design. They offer detailed information on materials, configurations, and accessory options, allowing users to make informed decisions.

What sets German kitchen catalogs apart is their attention to both technical detail and aesthetic presentation. Layouts are accompanied by dimensional drawings, while finishes are displayed with high color fidelity. This balance of information and inspiration makes the planning process more transparent and effective. Users are not overwhelmed by options but are guided through a curated selection of designs that embody the principles of functional beauty. In this way, catalogs support the design journey, transforming abstract ideas into tangible outcomes.

Conclusion: Functional Beauty as a Living Principle

The enduring appeal of German kitchens lies in their ability to marry functionality with visual elegance. They demonstrate that utility need not come at the expense of beauty, and that intelligent design can enhance both the experience and performance of a space. From the engineering of their components to the coherence of their materials, every element is crafted to support daily life with grace and efficiency.

As the role of the kitchen continues to evolve, the principles behind German design remain profoundly relevant. They offer a framework for creating interiors that are adaptable, durable, and emotionally satisfying. In doing so, they affirm that functional beauty is not a static ideal but a living principle—one that responds to the changing needs of modern life without losing sight of its foundational values. Whether viewed as a space for cooking, gathering, or simply being, the German kitchen endures as a testament to the power of thoughtful design.

0 notes

Text

Резиденція Вибачте Номерів Немає рада представити в Закарпатському академічному обласному театрі ляльок БАВКА прем'єру документальної аудіоп'єси Володимира Кузнецова «Гречка з м'ясом» з «Антології української кухні 2022–2024». За адресою: пл. Театральна, 8, м.Ужгород. 19.00, 5 березня, 2025

Дійові особи: Волонтери й волонтерки Київщини, Ржищівщини, Чернігівщини, Сумщини, Запоріжжя, Одещини, волонтерська група «Борщ для ЗСУ», «Ольшаницькі борщовари», «Спілка Учасників, Ветеранів, Інвалідів АТО та бойових дій» (СУВІАТО), десятки й сотні відомих і невідомих героїв та героїнь тилу. Музика: Мар’яна Клочко.

«Антологія української кухні 2022–2024», а вже й 2025 – це документація життєвих історій, досвідів та актів солідарності, відібраних на основі матеріалів Архіву Війни (Ukraine War Archive) й персональних відео- та аудіозаписів художника Володимира Кузнецова. Аудіоп’єса – художня форма, яку автор використовує для розповіді про феномен українського волонтерства. Цей феномен набуває обрисів великої бувальщини, легенди, трансформуючись згодом у міфи й казки. Аудіоп’єса транслюватиметься українською мовою із субтитрами SDH (з адаптацією для нечуючих). Аудіоп’єсу було створено у 2024 році в межах міждисциплінарної мистецької програми DOCU/СИНТЕЗ, 21 Docudays UA.

Програму резиденції ВНН, участь Володимира Кузнецова та прем'єру документальної аудіоп'єси В.Кузнецова «Гречка з м'ясом» реалізовано завдяки грантовій підтримці від The Académie des beaux-arts in Paris (French Academy of Fine Arts)

Вхід безкоштовний

(eng)

The residence Sorry No Rooms Available is pleased to present the premiere of Volodymyr Kuznetsov’s documentary audio play «Buckwheat with Meat» from «Anthology of Ukrainian Kitchen 2022-2024» at the Transcarpathian Academic Regional Puppet Theater BAVKA. At the address: 8 Teatralna Sq., Uzhhorod 19.00, March 5, 2025

Characters: Volunteers from Kyiv, Rzhyshchiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, Zaporizhzhia, Odesa, volunteer group “Borsch for the Armed Forces”, “Olshanytsia borshch cooks”, “Union of Participants, Veterans, Disabled ATO and Combatants” (SUVIATO), dozens and hundreds of known and unknown heroes and heroines of the home front. Music: Maryana Klochko.

«Anthology of Ukrainian Kitchen 2022-2024 and 2025» is a documentation of life stories, experiences and acts of solidarity, selected on the basis of materials from the Ukraine War Archive and personal video and audio recordings by the artist Volodymyr Kuznetsov. The audio play is an artistic form that the author uses to tell the story of the phenomenon of Ukrainian volunteerism. This phenomenon takes on the shape of a great story, a legend, transforming later into myths and fairy tales. The audio play will be broadcast in Ukrainian with SDH subtitles (adapted for the deaf). The audio play was created in 2024 as part of the interdisciplinary art program DOCU/SYnthesis, 21 Docudays UA.

The SNRA residency program, the Volodymyr Kuznetsov’s participation and the premiere of V. Kuznetsov’s documentary audio play «Buckwheat with Meat» were implemented thanks to the grant support from The Académie des beaux-arts in Paris (French Academy of Fine Arts)

The entrance is free

0 notes

Text

Prowl Art - Synthesis Wars

Another character challenge finished!

If you want to check my Choose your Bumblebee, is right here.

I thought there weren't that many Prowl's out there and would you look at this, 9 of them in total. of course there's also Earthspark and the who knows how many designs in IDW. Here's the full version:

The Prowl in my continuity was also a resident form Iacon, serving as part of the law enforcement team, alongside Barricade. Once Barricade joined the Decepticons, Prowl tried to silence him... permanently. Ultimately he failed, not because he couldn't, it was an unfair fight.

Prowl doesn't consider Barricade as his rival or Inimicus (term used in this continuity), he is just an obstacle for achieving justice. Once they arrive at Earth he becomes the guardian of Ethan Witwicky, the oldest of the group. He doesn't mind him since is the only human that doesn't get into trouble, unlike the rest, specially the teenagers.

Before the war, he had assigned two cadets under his wing for training. He wonders if both are still alive.

For now, I'll take a pause for the next "Choose your" challenge, maybe in the future I'll pull up polls for the following characters. Right now, I'll focus on writing the fic. Have a nice night!

#transformers#maccadam#transformers animated#transformers g1#transformers prime#transformers go! go!#transformers cyberverse#transformers one#tf prowl#prowl#transformers prowl#synthesis wars#my own au#Transformers Synthesis Wars#TFSW

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Fatal Flaw most people have.

The Warrior's Trinity: Unifying the Physical, Psychological, and Ethical Mindset

The Warrior's Trinity: Unifying the Physical, Psychological, and Ethical Mindset In today’s world of constant challenges and distractions, The Warrior’s Trinity provides a transformative guide to mastering life’s ultimate battleground: yourself. Written by Donald M. Husband Jr., a seasoned martial artist and philosopher, this groundbreaking book weaves ancient wisdom with modern insights to help readers build physical strength, psychological resilience, and ethical clarity—the three pillars of the Warrior’s Trinity. At its core, this book is a practical framework for personal mastery. Drawing from centuries of martial arts traditions, The Warrior’s Trinity explores the teachings of Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and the discipline of Spartan warriors alongside the strategic brilliance of Sun Tzu’s Art of War. This unique synthesis provides tools to cultivate inner and outer strength while empowering you to face adversity with courage, composure, and integrity. More than a theoretical exploration, this book equips you with actionable strategies to enhance your body, mind, and character. Through exercises, meditative practices, and advanced combat drills, it bridges martial discipline with daily life, helping you overcome fear, manage stress, and navigate challenges with ethical grounding. Key Highlights: Physical Strength: Training methods for building functional power, endurance, and precision. Mental Resilience: Techniques to overcome fear, sharpen focus, and develop situational awareness. Ethical Clarity: Practical guidance for living with humility, honor, and integrity. Historical Insights: Stories and lessons from Shaolin monks, Spartan warriors, and modern martial arts systems. Actionable Practices: Exercises and reflective prompts to align your body, mind, and ethics. Whether you are a martial artist, leader, first responder, or simply someone seeking self-mastery, The Warrior’s Trinity will inspire and guide you. It’s a philosophy for living with purpose, turning conflict—internal or external—into an opportunity for growth. Discover what it means to embody strength, balance, and honor. Step onto the path of the Warrior’s Trinity and begin your timeless journey of resilience, wisdom, and self-mastery. Order yours today:

Available: Hardback & Paperback available on Amazon https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DS28X3P9

Paperback available on Barnes & Noble https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-warriors-trinity-donald-husband-jr/1146774111?ean=9798992297515

Most people have this one fatal flaw.

Author's Site: http://www.donaldmhusbandjr.com Website: http://www.shihansdojo.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/shihansDojo/ Tumblr: https://www.tumblr.com/blog/shihansdojo X: @shihansdojo

#HealingJourney #MentalResilience #GrowthMindset #RiseStronger #OvercomeAdversity #Leadership #ethicaldecisionmaking #warriorsmindset #selfdefense #confidencechallenge #Strength #martialartsmastery #atheleticfocus #warriorsspirit #hopefortomorrow #booktok

0 notes

Video

youtube

Brian Tyler Cohen & Cenk clash in FIERY debate

COMMENTARY:

Cenk, the thing that you and all the Progressive bed wetters of "Independent Journalism" have to confront is that you, collectively, eleected Trump when you pursued that conceit that Biden's brains were turning to mush and threw away his winning vots by forcing him off the ballot.

Speking only for my self as an Eisenhower Republican woke Biden voter, I wouldn't care if he had to be spoon fed his oatmal in the moring and half of it drooled out the side of his mouth, As long as he was President, Kamala Harris was creating the Gen Z Democrat Party and Pete Buttigieg was at the helm of Transprotation. He was doing the spade work to restore 4o years of criminal Conservative neglect to the infrastructure from Supply Side Marxism and Grover Norquist's "starve the beast" agenda ensuring that infrastructure will be albe to exploit the SpaceX element of the US Space Force, which is the final structure of Stage 2 of Eisenhower and van Braun's transformation of the Military Industireal Complex to the Starship Capitalism of 2001:q Space Odyssey,

Trump ha been handed the best economy since before Project 2025 stole the 2000 election with the butterfly ballot. What Proect 2025 wants to do is to dismantle all these economies of scale and "privatize" America at salvage value, like after the George Bailey Savings and Loan industry was liquidated by the Resolution Trust Corporation and handed over to the Oligarchs.

Here's the thing: LTC Tulsi Gappard is the only person inside the Beltway who thinks in terms of Clausewitz like Putin and the US Army War College. The unit she is assigned to iis the 440th Civil Affairs Battalion, Tje heritage of its mission of this unit goes back to the Nation Building side of Clausewitz of George Marshall's reforms of 1942 inat installed the mechanisms of the League of Nations into the General Staff with G5, Civil Affairs, so that dumb ass civilian ideologues like Tommy Tuberville, Newt Gingrich, Bill Kristol and John Bolton couldn't dismantle them in favor of Pete Hegseth's idea of 'war fighting", G5 is the leading edge of the Marshall Plan and the Marshall Plan, the Atlantic Charter, the United Nations and NATO are the primary reason we don't ned an draft for Naitonal Sexurity,

When it comes to Clausewitz, Trump is a total dildo. The New York Military Academy was a reform school for rich kids. The irony is that Trump ran on Bill Clinton's Darton Accords foreign policy in 2015 in contrast to the regime stylings of Hillary Clinton and her Russian Nnarrative, That's why Charimn Kim wrote him love letters. Clausewitz. The Dayton Accords and the NATO-Russia Kosovo Protocls were the end of the Cold War. Bush/Cheney rebooted it with the criminal invasion of iraq and Obama/Clinton extended it because they don't know shit about Clausewitz.

Here's the thing: you guys and Pakman are in a box with Ben Shapiro: you are just opposite side of the same dialtectical coin. You are just differnt sides of Supply Side Marxism, the difference being the alturism of senimental liberalism and Ayn Rand's Virute of selfishness. The way out of your box is through Hegel and the Generoisty of Spirit that is the dialectical synthesis of transcendent self interst of paradox and the Declaration of Independence

But that's another story, Right now, quit trying to blame Biden's brain turning to mush and your own moral ambitions and intellectual contortions for how you fucked up.

0 notes

Text

Xuefeng Preaching Tao (6)

Xuefeng

June 3, 2008

(Translation edited by Jiejing)

Tao is the consciousness of the Greatest Creator, the driving force behind the movement and transformation of all things in the universe. It is the lifeblood of the universe, it is nature, and the synthesis of all laws.

Tao possesses eight characteristics: holographic order, eternal reliability, instantaneous sensitivity and adaptability, transcendence over time and space with no interior or exterior, spirituality, justice, non-obstruction, and illusory yet actual existence.

The Sixth Characteristic of the Tao: Justice

“If we look at things from a moment-to-moment perspective, it’s almost impossible to discern the justice of Tao. Where does the justice of Tao manifest when a kind person encounters a car accident? Where does the justice of Tao manifest when a place experiences an earthquake, causing mass casualties and injuries? Where does the justice of Tao manifest when some opportunists exploit and oppress good people, living in wealth and comfort, while hardworking, kind, and sincere individuals struggle with hardship and despair?

To see the justice of Tao, one must look at it from a macro perspective, from a holistic viewpoint, from the perspective of causality, from the long river of history, from the interplay of debts, from the future consequences, and from the principles of “Misfortune, that upon which happiness depends; happiness, that underneath which misfortune lurks.” and "If you want to contract something, you must first expand it; if you want to weaken something, you must first strengthen it; if you want to abolish something, you must first promote it; if you want to seize something, you must first give to it.”

When someone suffers from a headache, there is always a reason behind it. There is absolutely no headache without a cause. The occurrence of any phenomenon or event always has its reasons; there are no occurrences without reasons. All illnesses, pains, and disasters have their origins. When we trace back to their roots, we may find that some originate not long ago, while others have origins from a very long time ago. We tend to forget events from a long time ago because we cannot find their roots. Due to this, we often misunderstand the justice of Tao and mistakenly conclude that life is unpredictable and that the occurrence of all phenomena and events is merely coincidental.

In fact, the justice of Tao manifests not only on a macro and global scale but also on a micro and local level From quarrels between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law to palace intrigues, from slipping and falling outside to facing difficulties in tasks, from joys and sorrows, separations and reunions, to changes in weather and the waxing and waning of the moon, from personal fights to world wars, the justice of Tao is evident everywhere. The reason we often fail to perceive the justice of Tao is because we have not identified the root causes that lead to or trigger events.

In hell, there isn’t a single unjustly condemned spirit; between the realms of yin and yang, there isn’t a single unjustly condemned ghost; in the human world, there isn’t a single person who is unjustly accused. “As one sows, so shall one reap”; “Divine punishments, though slow, are always sure; with big meshes, yet letting nothing slip through”. The two levels are in symmetry, and yin and yang are in balance. Everything is a result of our own actions; there’s no point in blaming heaven, earth, society, or others.

Let’s explore the justice of Tao through a few examples.

The inevitability of death for everyone is a significant aspect of the justice of Tao. The poor die; the wealthy die; the great die; the insignificant die; the powerful die; the powerless die; the beautiful die; the ugly die... How fair it is! If some people didn't die, would there be any way out for us?

Has the sun not shone upon everyone? Regardless of who you are, the sun shines upon you. Is this not fair? The air circulates throughout the world, allowing every living being to breathe freely without charge. Is this not fair? Regardless of height, weight, wealth, or poverty, regardless of race, every person is given a pair of bright eyes. Is this not fair? Love attracts love, bringing joy to the heart. Everyone experiences this. How fair Tao is!