#Vladimir Gostyukhin

Photo

VOSKHOZHDENIYE (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

#voskhozhdeniye#the ascent#la ascension#larisa shepitko#boris plotnikov#vladimir gostyukhin#sergey yakovlev#lyudmila polyakova#viktoriya goldentul#anatoliy solonitsyn#mariya vinogradova#nikolai sektimenko#sergei kanishchev#film#cine

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ascent (Voskhozhdenie), Larisa Shepitko (1977)

#Larisa Shepitko#Yuri Klepikov#Boris Plotnikov#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Sergey Yakovlev#Lyudmila Polyakova#Viktoriya Goldentul#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Mariya Vinogradova#Nikolai Sektimenko#Vladimir Chukhnov#Pavel Lebeshev#Alfred Schnittke#Valeriya Belova#1977#woman director

0 notes

Text

Yet again, it's time to indulge in one of my favorite new year traditions: my ten favorite new-to-me films of 2023!

This is a wild, wild group of movies, but all of them got under my skin in one way or another and made this year that much brighter. If you like, consider this a strong endorsement for each of them.

Same rules as always: no movies from this past year (2023) or the year prior (2022). Every other year is fair game.

01. Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (dir. Chantal Akerman, 1975; Belgium/France; 202 mins.)

"I often cry when I think of you, Jeanne."

Sight & Sound's newly crowned Greatest Fim of All-Time was one of my first viewing experiences of 2023, and it loomed like a cloud over the rest of my moviegoing year. It was a bit of an ideal viewing experience - my favorite local independent theater had a showing, and the sizable audience was utterly enthralled by it. The massive Jeanne Dielman is a masterpiece in observation and behavior, and its power reveals itself through the way Akerman creates and unravels Jeanne's routine. She turns the lights off in every room she leaves. She replaces the lid of the money jar every single time. She watches her neighbor's baby for a little while in the afternoon. She looks presentable and pristine at all times, including after her sex work. When parts of these routines start shifting - the lid being left off the jar, the lights being left on for a bit too long, tousled hair - it plays like a jump scare.

I was shocked at how quickly this flew by. By the time the first day ended, I glanced at the time out of curiosity and was surprised to see it had already been an hour. Jeanne Dielman is a film that is frequently called "boring," which is both fair and entirely the point. It's still utterly mesmerizing within that boredom. This is thanks in large part to Delphine Seyrig's performance. With her hypernaturalistic stillness, Seyrig reaches rare levels of unaffected authenticity. Jeanne doesn't really feel like a character at all -- even with as little as we truly know about her, she feels like a human being.

Essential viewing. Long live the queen.

Currently streaming on the Criterion Channel and Max.

02. The Ascent (dir. Larisa Shepitko, 1977; Soviet Union; 111 mins.)

"Thanks for not leaving me. With company, it's... Okay, let's move on."

My final film in my 52 Films by Women challenge from a few years ago (shut up), Larisa Shepitko's The Ascent must be one of the greatest war movies ever made. Admittedly, it's not a genre I'm often drawn to, but Shepitko instills this film with an emotional power that becomes almost too much to bear.

Every act of cruelty, every gun fired, every open wound, is accompanied by a visceral pain. The way Shepitko uses the natural world as a stage for this story is astonishing - the vast snowy expanse of an unforgiving Russian winter, the rows of trees. Each of her actors manages to convey so much with their faces, too, especially the devastatingly good Lyudmila Polyakova, but the heart of the film is in the work of the two leads. Boris Plotnikov and Vladimir Gostyukhin work beautifully as a pair and as individuals. Shepitko masterfully traces the arc of their relationship against the backdrop of the war, and the end result is absolutely shattering.

The Ascent was, tragically, Shepitko's final film before she died in a car accident. It was my introduction to her as a filmmaker. I hope I can catch up with some of her earlier work, but The Ascent on its own is proof that she was a generational talent.

Currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.

03. The Big Snit (dir. Richard Condie, 1985; Canada; 10 mins.)

"And stop sawing the table!!!"

Oh my God, I loved this so much? Other than being vaguely aware of the title and its good reputation, I had no expectations going into The Big Snit, but everything about it worked for me. The utterly bizarre sense of humor, the voice acting (especially the CAT?!), and Condie's deft combination of a marriage gone stale against the backdrop of nuclear anxiety make for a surprisingly moving ending. I think it might be a masterpiece of the form. And like Jeanne Dielman, it feels profoundly influential - it's easy to see the aftershocks of The Big Snit in a decade's worth of shows on Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network.

Currently streaming on the National Film Board of Canada's website.

04. Vagabond (dir. Agnès Varda, 1985; France; 105 mins.)

"I know little about her myself, but it seems to me she came from the sea."

There really was nobody like Agnès Varda. Vagabond, or Sans toit ni loi, if you prefer its evocative original title, is pretty handily the most emotionally devastating film of hers that I've seen. As Varda shows us Mona's journey through the French countryside, it's hard not to see shades of Wendy and Lucy or even Nomadland. Like the protagonists of those films, Mona struggles to keep her head above water while living on the margins of society, and, like Reichardt and Zhao, Varda manages to find the joyful, the beautiful, and the life-affirming underneath the hardship. She also coaxes stunning work out of Sandrine Bonnaire, who turns in an extraordinarily unaffected and naturalistic performance.

Vagabond's secret weapon might be in its structure. Marrying traditional narrative scenes with a documentary-like direct address, Varda creates an achingly realistic atmosphere. Her work as a documentarian is well-known, and as a bridge between narrative and documentary filmmaking, Vagabond may just be the crown jewel in Varda's expansive body of work.

Currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.

05. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (dir. Steven Spielberg, 2001; USA; 146 mins.)

"And for the first time in his life, he went to that place where dreams are born."

Weepy existential sci-fi remains undefeated!

A.I. Artificial Intelligence is undeniably a huge swing. Genuinely feeling like that impossible mix between Spielberg's and Kubrick's sensibilities, A.I. achieves something of a hat trick - a fairytale steeped in existentialism. The Pinocchio comparisons are immediate and on-the-nose, but that doesn't make it any less fertile grounds for a compelling story. There's so much in this film that physically hurts the heart and the head to think about for too long - so much grief, so much cruelty - that framing it around David's immediately accessible journey toward becoming a real boy is pretty ingenious.

Of course, this film, maybe more than any of Spielberg's others, is deeply reliant on its lead performance. Haley Joel Osment is astonishing in this film, a blank slate for an entire world's love and anguish to project itself. Without him, the film would probably still be a fascinating sci-fi epic, but Osment lends the film the bulk of its emotional power. If we don't believe that David's entire reason for being comes from his need for love from his adopted mother (which, admittedly, is a pretty thin clothesline for the film's heavy plot to hang on), then we don't care. Osment makes us care. From anybody, this performance would be a triumph, but from a 12-year-old? It might be one of the miracles of acting.

Available to rent on demand.

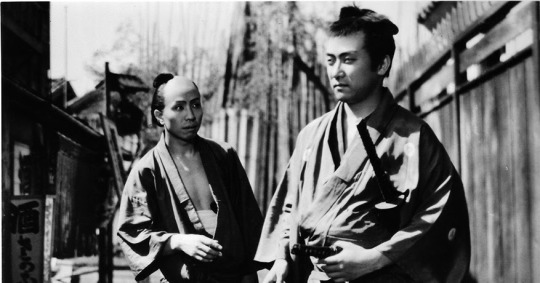

06. Humanity and Paper Balloons (dir. Sadao Yamanaka, 1937; Japan; 86 mins.)

"How could he kill himself on such a nice day? How utterly selfish of him."

Up until watching this film, I don't think I ever paid any special attention to Sadao Yamanaka's name. Within a year of the release of Humanity and Paper Balloons, the 28-year-old Yamanaka would be dead.

His untimely death only hints at the kinds of films he could have made with more time. This, though, is surely one of the finest (and most depressing) final films I can think of. One of the great strengths of Humanity and Paper Balloons is how startlingly modern it all feels: it's a 1930s drama, yes, but Yamanaka's thoughtful, assured direction really brings the poetic and tragic script (written beautifully by Shintaro Mimura) and performances (especially Kanemon Nakamura as Shinza the hairdresser) to life. Like the best tragedies, the events of Humanity and Paper Balloons feel senselessly cruel and brutally inevitable, but unlike other tragedies, Yamanaka is careful to keep just a bit of disarming humor to prevent the film from feeling too heavy.

It's an incredibly sad story beautifully told by a filmmaker struck down in his prime. Extremely worth a watch.

Currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.

07. Mississippi Masala (dir. Mira Nair, 1991; USA; 118 mins.)

"Home is where the heart is. And my heart is with you."

There is so much in Mississippi Masala that's wonderful. There's the beautiful young couple at the center, Sarita Choudhury (in a lovely debut performance) and Denzel Washington (a few years after his first Oscar win), who are so hot together that it feels like the TV might catch on fire. There's the supporting cast, too, including the legendary Sharmila Tagore, the great Charles S. Dutton, and the soulful Roshan Seth, whose sad, exhausted face is the heart of the film. There's the sensitive script by Sooni Taraporevala, that somehow finds an intimate romantic drama in a sprawling story that includes the Indian exodus from Uganda, an immigrant family's assimilation into the American South, and two clearly defined family dramas in vastly marginalized communities.

Perhaps most wonderful is Nair's gorgeous direction. The film has an expressive, vibrant visual palette, with so many different shades of red accompanying Mina and Demetrius' blooming romance. This is a rich, sensual film, and one of the great romantic dramas of the 90s.

Currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.

08. Lingua Franca (dir. Isabel Sandoval, 2019; Philippines/USA; 95 mins.)

"It doesn't matter where I go. They will hunt me down, and take me away."

Speaking of sensual! Sandoval, a true multi-hyphenate, is the director, writer, and lead performer in the stunning Lingua Franca.

The story, following an undocumented trans Filipina caregiver, is urgent, unabashedly political, and deeply moving. Sandoval and Eamon Farren both turn in deeply affecting performances, evocatively painting portraits of bruised souls trying desperately to find a way forward. The beauty in Sandoval's direction shows us that a way forward is within their grasp. It's the choices they need to make in striving for a better life that drive them further apart. The much-discussed sex scene is one of the most sensual and breathtaking in recent memory, but so much of the central romance is painted with such empathy and grace and beautiful visuals that it makes the unraveling feel all the more gutting. Also gutting is Lynn Cohen's quietly perfect performance.

Lingua Franca is not Sandoval's directorial debut, but it does feel like the arrival of a major artist. She's clearly one of the most exciting filmmakers working today.

Currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.

09. The Blue Angel (dir. Josef von Sternberg, 1930; Weimar Republic; 108 mins.)

"Men swarm around me like moths 'round a flame,

And if their wings are singed, surely I can't be blamed."

It's easy to see The Blue Angel as a collision between the expressionism and full-body physicality of silent cinema (embodied in Emil Jannings' performance) and the daring, tempting new-age sound cinema (embodied, of course, by the iconic Marlene Dietrich), but that almost devalues the skill of the actual storytelling and filmmaking going on here. Jannings' relationship with Dietrich - as naive and one-sided as it may sometimes be - is inevitable and pitiful. It's ridiculous and tragic to watch as he throws his entire life away for the most fleeting, meaningless romance imaginable.

Both lead performers are superb, of course. Dietrich, iconic across all of her Sternberg collaborations, is exquisite both in her onstage burlesque performances and her more intimate scenes with Jannings. Their chemistry is really lovely, even as we know it can never last. Jannings is tremendous, a layered and honest performance that culminates in an emotional breakdown that feels almost ripped from a Universal monster movie. The animalistic noises of his anguish are utterly haunting. Brutal stuff, and pretty handily my favorite Sternberg film.

Available to rent on demand.

10. Time Piece (dir. Jim Henson, 1965; USA; 9 mins.)

"Help!"

Why yes, that is the head of a young Jim Henson on that plate!

It's so weird seeing a Henson film without puppets, but if Time Piece is anything, it's weird. It's also brilliant - the product of Henson's singular creative voice. At just nine minutes, the short is a striking, funny, strange meditation on what it means to be beholden to the relentless march of time. It also boasts impeccable sound design and music, courtesy of the late, great Don Sebesky.

Currently available on Vimeo.

Special mention: Vittorio De Seta's 1955 documentaries.

In 1955, De Seta released six(!) documentary shorts: Islands of Fire, Surfarara, Easter in Sicily, The Age of Swordfish, Sea Countrymen, and Golden Parable. Stunning as individual films, but taken as a group, they become a meditation on the violence of living off the land and the endless cycle of life and death. Acting as director, editor, and cinematographer, De Seta marries ethnography and anthropology with artistry, creating bite-sized, miraculous films that immortalize life and labor in rural Sicily. The cinematography alone is jaw-dropping. Whether the films chronicle the Stromboli volcano, ancient religious rituals, a day of work in sulfur mines, harvesting grain, or the life of a fisherman, they are immersive and fleeting. The longest of these films is 12 minutes, and they all feel like dreams. Stunning stuff.

All six of these films, and more of De Seta's work, are streaming on the Criterion Channel.

Honorable mentions (in alphabetical order): After Yang (dir. Kogonada, 2021); Akira (dir. Katsuhiro Otomo, 1988); Asako I & II (dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi, 2018); Beverly Hills Cop (dir. Martin Brest, 1984); The Boy Friend (dir. Ken Russell, 1971); Carnal Knowledge (dir. Mike Nichols, 1971); Dogfight (dir. Nancy Savoca, 1991); Game Night (dir. John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein, 2018); Girlhood (dir. Céline Sciamma, 2014); The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (dir. Robert Clampett, 1946); Heat (dir. Michael Mann, 1995); Italianamerican (dir. Martin Scorsese, 1974); Kajillionaire (dir. Miranda July, 2020); Linda Linda Linda (dir. Nobuhiro Yamashita, 2005); Mean Streets (dir. Martin Scorsese, 1973); Night of the Living Dead (dir. George A. Romero, 1968); Pink Flamingos (dir. John Waters, 1972) Saving Face (dir. Alice Wu, 2004); Shake! Otis at Monterey (dir. D. A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, and David Dawkins, 1987); Shiva Baby (dir. Emma Seligman, 2020); Three Thousand (dir. asinnajaq, 2017); Videodrome (dir. David Cronenberg, 1983); When the Day Breaks (Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby, 1999); While You Were Sleeping (dir. Jon Turteltaub, 1995); Windy Day (dir. John Hubley and Faith Hubley, 1968); Wings of Desire (dir. Wim Wenders, 1987); Your Face (dir. Bill Plympton, 1987)

And finally, some miscellaneous viewing stats:

First movie watched in 2023: Akira (dir. Katsuhiro Otomo, 1988)

Final movie watched in 2023: The Devil Wears Prada (dir. David Frankel, 2006)

Least favorite movie: Blonde (dir. Andrew Dominik, 2022)

Oldest movie: The Impossible Voyage (dir. Georges Méliès, 1904)

Longest movie: The Ten Commandments (dir. Cecil B. DeMille, 1956 - 220 mins.)

Shortest movie: Premonitions Following an Evil Deed (dir. David Lynch, 1995 - 1 min.)

Month with the most viewings: January (35)

Month with the fewest viewings: May (5)

First movie from 2023 seen: Rye Lane (dir. Raine Allen-Miller, 2023)

Total movies: 231

Movies! They're good. Sometimes. Happy new year, friends!

#this is not an ad for the criterion channel i promise#jeanne dielman 23 quai du commerce 1080 bruxelles#chantal akerman#the ascent#larisa shepitko#the big snit#richard condie#vagabond#agnès varda#a.i. artificial intelligence#steven spielberg#humanity and paper balloons#sadao yamanaka#mississippi masala#mira nair#lingua franca#isabel sandoval#the blue angel#josef von sternberg#time piece#jim henson#vittorio de seta#islands of fire#surfarara#golden parable#easter in sicily#the age of swordfish#sea countrymen#sometimes elliott watches movies#year in review

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

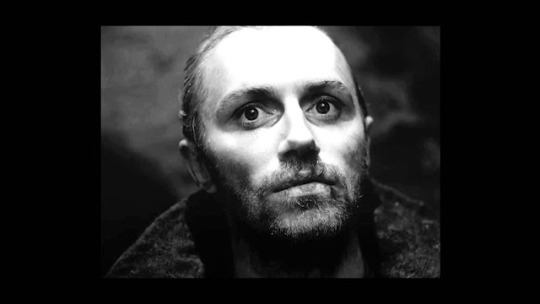

Boris Plotnikov in The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

Cast: Boris Plotnikov, Vladimir Gostyukhin, Sergey Yakovlev, Lyudmila Polyakova, Viktoriya Goldentul, Anatoliy Solonitsyn, Mariya Vinogradova, Nikolai Sektimenko. Screenplay: Yuri Klepikov, Larisa Shepitko, based on a novel by Vasiliy Bykov. Cinematography: Vladimir Chukhnov, Pavel Lebeshev. Production design: Yuriy Raksha. Film editing: Valeriya Belova. Music: Alfred Schnittke.

In some ways, The Ascent is the movie that the overpraised The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015) could and perhaps should have been: a rewarding but harrowing story, made without flashy technology, that asks as much of the viewer as it did of the actors and crew. Made under extreme winter weather conditions -- temperatures dropped to 40 degrees below zero -- in January 1974, it tells the story of two Russian partisans in World War II, Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov) and Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukin), who go in search of food for their small group of fellow resistance fighters. When they're spotted by some German soldiers, Sotnikov kills one but is wounded in the leg. Through deep and blinding snow -- there's a memorable scene in which Rybak has to thaw a frozen Sotnikov with his own breath -- Rybak helps Sotnikov reach a cabin where a young woman, Demchikha (Lyudmila Polyakova), who lives alone there with her three children, helps them hide in the attic. But they're discovered by the Germans and taken to their headquarters in a Russian village, where the head of the collaborating Russian police, Portnov (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), interrogates them. Portnov tortures Sotnikov first, branding a star onto his chest, but Sotnikov stoically resists. When Rybak is brought in, he assumes that Sotnikov has already told everything, so he proceeds to give Portnov as much information as he has. To his dismay, he is sentenced to death along with Sotnikov, Demchikha, and two others. Sotnikov, gravely ill, confesses that he killed the German and maintains that he alone of the five deserves execution. Rybak, on the other hand, persuades Portnov that he could be of use as a collaborating policeman, and is spared execution. After the others are hanged, Rybak becomes the target of the contempt of the witnessing villagers, who mutter "Judas" at him. Torn by guilt, he tries to hang himself but fails, and at the end is left to his misery. This was the last film by Larisa Shepitko, who died in an automobile accident at the age of 41. She and her actors and crew underwent great hardships filming it, coming down with frostbite, but the film was almost suppressed by the Soviet authorities, who thought it was too much of a Christian parable. In fact, Shepitko had insisted on an actor who resembled traditional images of Christ, and Plotnikov's lean, ascetic appearance is heightened by the cinematography of Vladimir Chukhnov and Pavel Lebeshev, especially as Sotnikov stands with the noose around his neck at the film's climax. Fortunately, Shepitko and her husband, director Elem Klimov, were able to gain the support of former World War II partisans who testified to the veracity and emotional power of the film.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ascent (1977)

126 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

135 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ascent (Shepitko, 1977)

#the ascent#Восхождение#larisa shepitko#shepitko#boris plotnikov#vladimir gostyukhin#anatoli solonitsyn#lyudmila polyakova#cinema#film#soviet#soviet union#belarus

212 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Восхождение (The Ascent), dir. Larisa Shepitko, 1977.

#Larisa Shepitko#The Ascent#Лари́са Шепи́тько#Восхождение#Cinema#Soviet Cinema#Boris Plotnikov#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Anatoli Solonitsyn

970 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sweet smell of success#piers marchant#ssos#movies#films#arkansas democrat gazette#criterion edition#the ascent#larisa shepitko#wwII#Boris Plotnikov#Vladimir Gostyukhin

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Larisa Shepitko “Восхождение” (The Ascent) April 2, 1977.

#Larisa Shepitko#Восхождение#The Ascent#1977#Seventies#World War II#WWII#Drama#Tragedy#Stills#Foreign#Boris Plotnikov#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Lyudmila Polyakova#Anatoly Solonitsyn#🇷🇺

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

#the ascent#larisa shepitko#shepitko#quote#1977#death#faces#black and white#snow#cold#winter#Voskhozhdeniye#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Boris Plotnikov#hands

602 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ascent (1977, Soviet Union)

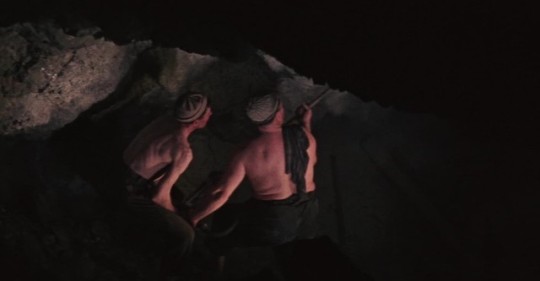

In 1939, representatives from Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Moscow. The pact was to guarantee a policy of mutual non-aggression towards the two nations, also stipulating that neither nation would ally itself with an enemy of the other. Countries across Europe not yet conquered by either nation looked on in fear and disbelief – there was little to stop the Germans or the Soviets. Yet the lack of violence does not necessarily mean peace. German-Soviet relations deteriorated as soon as both Hitler and Stalin began to annex neighboring states, with the Nazis invading the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

Larisa Shepitko would have been three years old when the pact was dissolved. Born in Soviet Ukraine, her lasting memories of the war included constant hunger, emotional distress, displacement. In 1954 after graduating high school, she enrolled at the esteemed Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow, with Alexander Dovzhenko (1929′s Arsenal, 1930′s Earth) as her mentor. A fellow Ukrainian, Dovzhenko’s social realism and use of stark imagery (as any giant of the silent film era mastered) with religious influences would have the most lasting influence on Shepitko’s brief directorial career. The Ascent – her final film, and her breakthrough work among Western audiences – is the confluence of Shepitko’s memories of wartime and the expertise she gained while studying with Dovzhenko at VGIK. What appears to be a straightforward war film on paper is anything but, as Shepitko demonstrates with her singular artistry.

It is the winter of 1942 in the Byelorussian SSR (modern-day Belarus). A company of partisans is retreating from a horde of Nazi soldiers when they finally have a moment of quiet. Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov) and Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukhin) are ordered to search for food in a nearby village. Along the way, the men encounter more German soldiers – Sotnikov incurs a leg wound, and Rybak drags his comrade to a nearby home. Inside the home is Demchikha (Lyudmila Polyakova), who has three children. As the film progresses, Sotnikov and Rybak will be in the custody of Portnov (Anatoly Solonitsyn) – a former director of the local club-house (in Soviet parlance, a cultural and recreational institute) who has become the leader of the local Byelorussian Auxiliary Police. In other words, Portnov is working for a Nazi-affiliated paramilitary comprised of other local defectors, tasked with keeping the locals pliant, staging public executions to those aiding the Soviet Union.

Like a Dante-esque scene, Sotnikov and Rybak are constantly surrounded by mounds of knee-deep snow and trees long shorn of leaves. The color white is omnipresent except for the film’s few indoor shots. This harsh landscape reveals the character of those who dare to brave it, whether or not they escape death. The Ascent flares the senses – especially sight – early and often. Long stretches of the film’s scenery contain nobody except our two protagonists. Cinematographers Vladimir Chukhnov (1978′s On Thursday and Never Again) and Pavel Lebeshev (1977′s An Unfinished Piece for Mechanical Piano, 1998′s The Barber of Siberia) make use of hand-held cinematography for many of these outdoor scenes and especially the firefights – hand-held cinematography remained a rarity in cinema anywhere and everywhere until the 2000s. Their camerawork makes the few, brief battles more visceral, increasing the impact of the gunfire and any wounds incurred. After Sotnikov and Rybak are captured, the cinematography and editing (the editor is uncredited) slow down. Locked in a cell with other partisan-sympathetic villagers, their physical and mental imprisonment is captured by stilled camerawork and fewer cuts. The final minutes of The Ascent features a stunning lack of cuts – forcing the viewer to internalize all the characters’ emotions as they are being led to their fates.

The film is based on Belarusian author Vasil Bykaŭ’s novella Sotnikov, and was adapted to the screen by Shepitko and Yuri Klepikov (1966′s The Story of Asya Klyachina, 1972′s Dauriya). One might expect The Ascent to be littered with Soviet propaganda and, given how the Soviet Union treated war movies (set in any era, such as its treatment of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Alexander Nevsky), such assumptions would be understandable. But Shepitko’s films, even at their most political, are rooted in principle and humanity. The famously irreligious Soviet government and its censors seemed to have missed (or, perhaps, let slide because of how one character is portrayed) the Christian allegory in the Shepitko and Klepikov screenplay. Sotnikov and Rybak – how they act in the face of temptation, their sense of duty – resemble a wartime Jesus Christ and Judas Iscariot (just pretend Jesus’ eleven other disciples never existed). The faithful partisan between the two of them is lit and framed in respects to his martyrdom. But their dynamic is never simplistic as they remain grounded by the military and political realities of their mission and service to those they wish to protect. Shepitko’s approach probably appeased the Soviet censors – after a loosening of standards under Nikita Khrushchev, the cultural censors under Leonid Brezhnev were returning to Stalin-era guidelines – while employing her signature triumphing of human virtues. Bravery and cowardice are juxtaposed throughout the final half of The Ascent. It is to Shepitko’s credit that she makes her hero’s actions unassuming, her coward’s betrayal understandable.

Indirectly but intentionally, The Ascent notes how Nazi Germany’s atrocity-laden campaign against the Soviet Union has affected how the latter has treated its enemies – foreign and domestic – in the years during and after the war (does this mean that The Ascent has ulterior themes criticizing the Soviet government? I don’t believe so). The Nazis – through Portnov and his subordinates – attempt to turn conquered citizens and captured partisans against each other, engage in whataboutism, and have no compunctions about using violence to solve problems. In the final minutes, the film’s Soviet Judas is distraught to see how one seemingly easy decision has enabled injustice. This Judas figure believes he can reverse, maybe compensate for what horror he has been party to. But ultimately, he accepts that he cannot be what he was, and finds absurdity and tragedy in his actions.

Boris Plotnikov (1988′s Heart of a Dog) makes his crediting acting debut in The Ascent is magnificent as Sotnikov. His distant stare and deliberate movements suggest weariness – of the war, of the world. So too as Vladimir Gostyukhin (1991′s Close to Eden) as Rybak – although the greatest moments of his performance appear in the dying minutes of the film, as he struggles with an internal conflict. Anatoly Solonitsyn, as Portnov, is the hard-nosed defector – with no expression suggesting any second thoughts on the devastation he has wreaked on his neighbors, his former friends and colleagues. Solonitsyn’s supporting performance pierces through the film’s moral center, subordinating it to the machinal madness of Nazi policy towards its enemies.

A fascinating, sparsely-cued score by Soviet-German composer Alfred Schnittke complements a film that I would have otherwise imagined to have no music. Schnittke was primarily known for his work in classical music rather than film and television scores. But Schnittke, unlike earlier Soviet composers like Sergei Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich, is not so much interested in nineteenth-century-influenced melodies and rousing idea- or character-driven leitmotifs, but texture, atonalism, and the use of multiple styles of music at once (“polystylism”; which Schnittke is often credited as innovating). Given the discordant and numbing nature of The Ascent, Schnittke’s music – which might be a difficult listen for audiences who are not familiar with the difference with “classical music” and “contemporary classical music” – empowers scenes of physical and spiritual desolation. This is a score that, in the few instances that it appears (especially in a moment resembling Jesus’ last steps to Calvary), is allowed to be front and center when it does.

youtube

Larisa Shepitko would not be able to enjoy the subsequent acclaim this film (and her career) would eventually find in the West. This overdue appreciation of Shepitko’s work can be attributed to the lack of awareness of Soviet cinema beyond certain directors and attitudes towards female directors. Shepitko, the director of one of the greatest war films of all time, was killed in a car accident in 1979 while scouting shooting locations for an adaptation of Valentin Rasputin’s novel Farewell to Matyora. The accident also took the lives of cinematographer Chukhnov, production designer Yuri Fomenko, and three other members of the crew. Shepitko’s husband, director Elem Klimov, would finish his late spouse’s work in 1983 – two years before the release of his shattering war film Come and See (1985).

This is a film arguing for moral goodness – something unmentioned in Soviet communist ideology. The Ascent, filled with religious visual and thematic allusions, is as spiritual as any Soviet film could possibly be. Its spirituality is displayed and tested in the theater of warfare, making any viewer of this film go through the whirlwind of emotions. Abandonment, desolation, hopelessness, regret all flow through the screen, speaking to those heeding Shepitko’s appeal for conscientiousness when confronted with cruelty.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. The Ascent is the one hundred and fifty-first feature-length or short film I have rated a ten on imdb (this write-up was expedited before the write-ups on the films that will be the 149th and 150th).

#The Ascent#Larisa Shepitko#Boris Plotnikov#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Sergei Yakolev#Lyudmila Polyakova#Viktoriya Goldentul#Anatoly Solonitsyn#Yuri Klepikov#Vladimir Chukhnov#Pavel Lebeshev#Vasil Bykau#Alfred Shnittke#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voskhozhdeniye – Tırmanış

Voskhozhdeniye – Tırmanış

Savaş acıdır, kandır, vahşettir, insanın insana yapabileceği en büyük kötülüktür. Başkalarının yüksek çıkarları için diğer insanları öldürmenin adıdır. Savaş ile ilgili aklınıza gelebilecek her türden olumsuz nitelemeyi buraya ekleyebilirsiniz. Ama ya ülkeniz işgal edilmiş ise, size sadece işbirliği yaptığınız sürece bir hayat hakkı tanınıyor ise ne yaparsınız, geriye…

View On WordPress

#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Aufstieg#Boris Plotnikov#Film eleştirileri#Larisa Shepitko#Lyudmila Polyakova#Mariya Vinogradova#Nikolai Sektimenko#Obelisk. Sotnikov#Süleyman Deveci#Sergey Yakovlev#The Ascent 1977#Vasiliy Bykov#Viktoriya Goldentul#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Voskhozhdeniye – Tırmanış#Yuri Klepikov

0 notes

Photo

The Ascent aka Voskhozhdenie (1977), dir. Larisa Shepitko

#Восхождение#Лариса Шепитько#voskhozhdenie#voskhozhdeniye#the ascent#larisa shepitko#russian#soviet#world war 2#bykov#sotnikov#rybak#ussr#novel#yuri klepikov#boris plotnikov#vladimir gostyukhin#soviet union#mosfilm#black and white

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ascent (1977, Larisa Shepitko)

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ascent (1977)

So, you can add The Ascent to the long list of amazing movies Russia made about World War II. Ever since watching this movie, I’ve been trying to put my finger on what exactly makes Russian war movies so damned good. I think it has something to do with the fact that they don’t shy away from, or try to glorify, the fact that the Soviet Union was utterly savaged in World War II. They fully embrace the tragedy of it all–like the deaths of good young men in Ballad of a Soldier; or the decimation of Soviet youths’ hopes and futures in The Cranes Are Flying; or the destruction of the general, overall innocence of children growing up in all the chaos in Come and See. The Ascent portrays the hopelessness of the Russian people in wartime–you can be a dead hero or a live coward, an innocent child or a mercenary or anything in between. No matter which road you follow, your destination is going to be some style of doom. That’s really what the reality of the situation in Russia during World War II seemed to be. It’s generally believed that 20 to 30 million Soviets were killed in the war, the most of any fighting nation. Wikipedia says that one in four Russian citizens were killed or injured. That’s insane.

So The Ascent was sad, and haunting, and amazing. The visuals especially are striking–from the shots of soldiers trekking through snow to a young Russian boy watching public executions. Its director, Larisa Shepitko, never falters or turns away to spare the audience. Sad to say that she died two years after making this movie, in a car accident.

But yeah, check it out. Good Russian movie.

1 note

·

View note