#a palestinian meditation in a time of annihilation

Text

Fady Joudah, from A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation

#fady joudah#a palestinian meditation in a time of annihilation#words#lit#essays#typography#palestinian literature#palestine

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Years ago, I received a query from a prominent editor about a line in Mahmoud Darwish’s long poem, “The ‘Red Indian’s’ Penultimate Speech to the White Man,” (If I Were Another). The poem channels Chief Seattle’s voice and spirit. In the poem’s second section, the line in question follows an address to Columbus, “the free [who] has the right to find India in any sea, / and the right to name our ghosts as pepper or Indian.”

The line in question is this: “You have burst seventy million hearts…enough, / enough for you to return from our death as monarch of the new time”:

isn’t it time we met, stranger, as two strangers of one time

and one land, the way strangers meet by a chasm?

We have what is ours…and we have what is yours of sky.

You have what is yours…and what is ours of air and water.

“I just don’t get where he got the seventy million from?” the editor asked.

I didn’t reply. I didn’t wonder about the accuracy of Darwish’s claim. Maybe he included all the Natives annihilated in the Americas over the centuries. The only thought I had in my head was, “Is this really what’s bothering you about the poem?”

Years later, in a daydream, a marginalia of my soul visited me, and it spoke thus: “Do you remember those seventy million punctured hearts in Darwish’s poem? If you’re ever asked again, if the person who asks you says that historical studies show the number is not possible or whatever, remember the buffalos.”

The buffalo hearts are also native hearts.

Who will count the donkeys, dogs, and cats in Gaza?

The birds will return.

— Fady Joudah, in his essay “A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

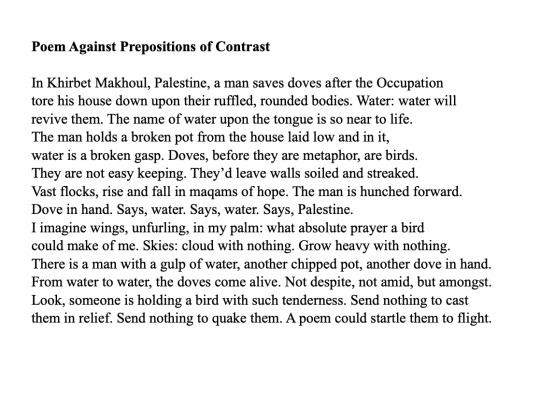

Folks, we have the first commissioned poem. The prompt was animals or birds. More on my Poems for Palestine fundraiser here. I have been thinking of Fady Joudah's A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation: Thirteen Maqams for an Afterlife. I think about how the birds will return. This poem reckons with a photograph from Jordan Valley, Palestine, of a man trying to save doves.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hiba Abu Nada, 32, wrote and published her final poem ten days before Israeli bombs killed her and many others on October 20, 2023, in Gaza. She had a B.A in organic chemistry and a master’s degree in clinical nutrition. In her short life she managed to publish one novel, Oxygen is Not for the Dead. The speaker in Abu Nada’s final poem is an inner I, probably the voice of God welling up inside. Here is an excerpt:

I shelter you

and the children who

are sleeping

as chicks in the lap

of their nest

they don’t walk

in their dreams

because death

towards the house

walks

….

I shelter you

from wound and woe,

and with seven verses

I shield

the taste of orange

from phosphorus,

the color of clouds

from smoke.

"A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation | Thirteen Maqams for an Afterlife", by Fady Joudah, published in Lit Hub, November 1, 2023

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

At Least 13 Palestinian writers have been killed by Israel since October 7

In the last Palestinian poem I shared, the speaker contemplates the very real possibility that they’ll be murdered — this is a subject that has cropped up over and over as I read through Palestinian poems. These poets know that life under occupation is always tenuous, and especially so for anyone who dares to speak up against the occupying force like they do in their poetry.

Professor Refaat Alareer’s poem “If I Must Die,” which has been read all over and translated into multiple languages since his death by Israeli airstrike in December, is one example that I highly recommend you look up if you haven’t heard it yet. (For instance, here it is set to haunting music.)

According to LitHub, Israel has killed at least 13 Palestinian poets and writers since October 7; and in the seven or so decades before then, countless others were targeted for arrest or death — so it makes sense that one’s own death a common topic in Palestinian writing.

But God, it breaks my heart. Things should not be this way! People whose only weapon is a pen should not fear assassination. People just trying to live should not fear death by bombing or torture.

I’ll be sharing some Palestinian poems on this theme in the next few days. In the meantime, here’s a piece of writing by Heba Abu Nada, who died in an Israeli airstrike in October. This is one of the last social media posts she made before she was killed:

"Each of us in Gaza is either witness to or martyr for liberation. Each is waiting to see which of the two they’ll become up there with God. We have already started building a new city in Heaven. Doctors without patients. No one bleeds. Teachers in uncrowded classrooms. No yelling at students. New families without pain or sorrow. Journalists writing up and taking photos of eternal love. They’re all from Gaza. In Heaven, the new Gaza is free of siege. It is taking shape now.”

(Quote taken from the excellent "Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation" by Fady Joudah)

I pray Heba Abu Nada is in peace in that heavenly Gaza now. But here and now, it is our sacred task to do everything we can to end Gaza’s hell on earth.

No more dead poets. No more elders and children killed. Palestine must be free.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fady Joudah, from A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation

#tumblr#free palestine#i stand with palestine#palestine#stop genocide#death to israel#death to america#i stand with gaza#free gaza#gaza#end war#humanity

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stuff I Read in January 2024

bold indicates favourites

Novels

Death's End, Cixin Liu

The Maze Runner/The Scorch Trials/The Death Cure, James Dashner

Echopraxia, Peter Watts

Other Long-Form

Against the Gendered Nightmare, baedan [anarchist library]

Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin

What Is To Be Done, Lenin

Yuri/GL

Ring My Bell, Yeongol

Dallae, Choonae

Now Loading! Mikanuji

Even If It Was Just Once, I Regret It / Ichido Dake Demo, Koukai Shitemasu, Miyako Miyahara

Maka-Maka, Torajirou Kishi

Blooming Sequence, Lee Eul

Love Bullet, inee

Honey Latte Girl, Ayu Inui

I'm Sorry I Know / Wakatte Iru No Ni Gomenna, Ayu Inui

Night and Moon / Yoru to Umi, Goumoto

Handsome Girl and Sheltered Girl / Ikemen Onna to Hakoiri Musume, Mochi au Lait & majoccoid

The Forbidden Peach / Suimitsutou Ha Shoujo Ni Kajirareru, Iroha Amasaki

Goodbye, My Rose Garden, Dr Pepako

Blood Lust, yoshimired [link]

Palestine

The Grim Reality of Israel's Corpse Politics, Jaclynn Ashly [jacobin]

Mohammed El-Kurd and Ahmad Alnaouq on the complicity of mainstream media in Israel’s genocidal attack on Gaza [link]

Inside Israel's torture camp for Gaza detainees, Yuval Abraham [archive]

The Work of the Witness, Sarah Aziza [link]

Who profits from keeping Gaza on the brink of humanitarian catastrophe? Shir Hever [archive]

Misreading Palestine, Max Ajl [link]

A Pediatrician's Two Weeks Inside a Hospital in Gaza, Isaac Chotiner [link]

A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation, Fady Joudah [link]

Gender/Sexuality

Assigned Faggot: Gender Roles, Sex, and the Division of Labour, Sophia Burns [link]

Gendered Bodies: The Case of the 'Third Gender' in India, Anuja Agrawal [doi]

Paola Revenioti: The Greek transgender activist on blowing up sexual taboos in the name of art, Hannack Lack [link]

Wages Against Housework, Silvia Federici [pdf]

My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage, Susan Stryker [pdf]

Race

This is Crap, Hannah Black [link]

Social Constructions, Historical Grounds, Shay-Akil McLean [link]

White Psychodrama, Liam K. Bright [doi]

‘I don’t think you’re going to have any aborigines in your world’: Minecrafting terra nullius, Ligia López López, Lars de Wildt, Nikki Moodie [doi]

Singular Purpose: Calculating the Degree of Ethno-Religious Over-representation in the US No-Fly List, Matteo Garofalo [doi]

Iran

Samad Behrangi's Experiences and Thoughts on Rural Teaching and Learning, M. H. Fereshteh [jstor]

The "Westoxication" of Iran: Depictions and Reactions of Behrangi, al-e Ahmad, and Shariati, Brad Hanson [jstor]

Geographies of Capital and Capital of Geographies: Reckoning the Embodied City of Tehran through Cosmetic Surgeries, Marzieh Kaivanara

Economics

China in Africa: A Critical Assessment, Ahjamu Umi [link]

Small Scale Farmers and Peasants Still Feed the World, Report by ETC Group [link]

16 Million and Counting: The Collateral Damage of Capital [link]

The Keynesian Counterrevolution, Mike Beggs [jacobin]

Jobs For All, Mike Beggs [jacobin]

Other

How This Climate Activist Justifies Political Violence, David Marchese interviewing Andreas Malm [NYT]

Against Domestication, Jacques Camatte [marxists dot org]

The Annihilation of Caste, B. R. Ambedkar, [archive]

#reading prog#ftr i didn't read the original maze runner trilogy because i thought it would be good (it is bad in fact)#but to finally turn the page on an autistic Situation i had like five years ago

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation by Fady Joudah ‹ Literary Hub

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation

Thirteen Maqams for an Afterlife

By Fady Joudah

November 1, 2023

I

Hiba Abu Nada, 32, wrote and published her final poem ten days before Israeli bombs killed her and many others on October 20, 2023, in Gaza. She had a B.A in organic chemistry and a master’s degree in clinical nutrition. In her short life she managed to publish one novel, Oxygen is Not for the Dead. The speaker in Abu Nada’s final poem is an inner I, probably the voice of God welling up inside. Here is an excerpt:

I shelter you

and the children who

are sleeping

as chicks in the lap

of their nest

they don’t walk

in their dreams

because death

towards the house

walks

….

I shelter you

from wound and woe,

and with seven verses

I shield

the taste of orange

from phosphorus,

the color of clouds

from smoke."

I reproduced only the beginning of this text of Fady Judah. His whole text can be found on:

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

[id: screenshot that reads "But I have a more daring question. The Israeli people at large, the Jewish communities outside Israel that identify strongly or faintly, defensively or hawkishly with Israel, the mainstream Western world, and all expressions of Zionism, what do they want from Palestinians?" end id]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation ‹ Literary Hub

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fady Joudah, “A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation”

#I just...#w#lit#fady joudah#mahmoud darwish#all beautiful poetry is an act of resistance#from the river to the sea

986 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

On the morning that water entered our house, we rushed, all four of us, to salvage what we could from the first floor. Some of those items were my books, especially those on the lower shelves. Months later, after the house was remodeled, I got those books out of their boxes to reshelve them. For days, I was obsessively lost in my memories: books I had read decades ago, my marginalia and underlined sentences, flagged paragraphs, arrows, earmarks, all modes of signs and signals I had left behind—like a map for myself in an afterworld I was certain would come but didn’t know how or when: what I once was, how I once thought, felt, searched, loved, and whether I still feel the same.

Isn’t this what burial rites are about? We send our lost loved ones, who are part of ourselves, to an afterlife, with or without accessories, but always with words, prayers that launch their departure into our memories. And so it is with the parts of ourselves we bury in our books: memories of the self that, when we revisit in the marginalia we leave behind on the printed page, we encounter as a version of our afterlife.

Hiba Abu Nada did not live long enough to encounter her afterlife through her books.

"A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation | Thirteen Maqams for an Afterlife", by Fady Joudah, published in Lit Hub, November 1, 2023

#fady joudah#hiba abu nada#quotes#essays#words#found*#palestine#on the spiritual#i excerpted this but encourage you to read the entire essay

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

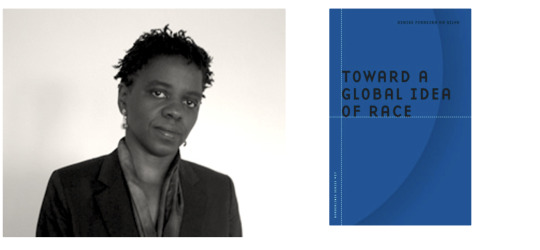

The Ghost of the Subject

In Toward A Global Idea of Race (2007), da Silva raises several trenchant questions that are extremely relevant to the Palestinian context. For example, read the following quotes:“How does social scientific knowledge justify the murder of people of color? My reply is, How does its arsenal explain it?” (xiv) If God was dead in late eighteenth century Europe, “should we not expect that a lesser entity would eventually share the same fate?……if the Subject, the thing that actualizes reason and freedom, had been born somewhere in time, would it not also eventually die?” (xx) Meditating on the co-occurrence of subaltern voices and the announcement of “the death of the subject” under “postmodernity” among Western academics, da Silva recenters many indigenous and black women’s political sensibility. Whose death? Who is perceived as terrifying and threatening to kill? Who’s lamenting the fragility, mortality, and perceived death of the universal Subject? In the name of what do they defend this Subject, science or history?

We are living in the aftermath of such announcement and the paranoia it produces. I cannot but read this as a painful reminder of Israel’s targeted assassinations of prominent writers, journalists, and scholars in Gaza. Most recently, the beloved Dr. Refaat al-Areer was killed yesterday amidst Israel’s targeted bombardment of his house. The history of white supremacist settler colonial modernity must defend its Subject, a Subject predicated on the absolute annihilation of all traces its others. No wonder any mentioning of Palestinian lives is immediately (and pathologically) deemed as a call to wage war on the Israeli Subject. Such is the onto-epistemological premise the modern Subject in the form of the nation-state operates upon. It is not self-victimizing, it is by definition a victim. Victimhood is its unnegotiable onto-status.

To whom is this death of the Subject real and relevant? Consider the following scenario from her reflection:

“Many of my undergraduate students, some actively involved in the struggle for global justice, stare blankly at my mention of the death of the subject. ‘The death of whom?” they ask, demanding clarification. After my initial surprise, I usually find myself trying to explain why the political significance of his death derives precisely from the ontoepistemological irrelevance of his death: the subject may be dead, I tell them, but his ghost—the tools and the raw material used in his assemblage—remain with us.” (xxiii)

In the following pages of the Introduction, she firmly rejects the impulse to interpret subaltern voices through the paradigm of inclusive representation, especially considering that this “epistemological emancipation” of the Subject or Human “seemed out of sync with the concept’s ontological inheritance”. (xxi) Following this, she simultaneously rejects reformist accounts of the Subject. This includes, among others, the anti-racial-capitalist Subject, arguing that historical materialism’s privileging of historicity fails to take racialization (as a post-Enlightenment strategy of power) seriously. That is, by theorizing race as merely a byproduct of capitalist modernity, historical materialists in effect relegate any racial project as ahistorical and therefore excluding them from the realm of the Subject. It remains unclear why any political project should prioritize historicity at all at the cost of subjugating discussions of race. It is for this line of thinking that I deem the Leninist-historical inquiry of “What Is to Be Done” at the moment as a dangerous betrayal of the Palestinian cause. Likewise, I find her critique of anti-colonial transnational feminist Subject spot-on, as it too falls into the tropological trap of representative inclusivity.

If the problem is not inclusivity and exclusivity, what then? Following Joan Scott and like Gayatri Spivak, she seems to target the discursive power of modernity-coloniality per se. It indicates that any modern political projects that presupposes a universal Subject, in its countless forms, fails to get to the root of the problem. This gives rise to a whole different set of questions, but at the core of these is “why, despite its moral ban, the racial still constitutes a prolific strategy of power.” (xxxi) Unlike Scott and Spivak, however, she explicitly refuses to center her project around the documentation and demonstration of historical-discursive exclusivity. Instead, she seeks to investigate the seemingly unbroken triangle of ethics, morality, and justice, that is, the mental gymnastics of the Subject:

“engage in the kind of analytical groundwork necessary for a critical account that moves beyond listing how each excludes, and, instead, examine how the racial combines with other social categories (gender, class, sexuality, culture, etc.) to produce modern subjects who can be excluded from (juridical) universality without unleashing an ethical crisis.” (xxxi)

In other words, this is a critical project that stretches the narrative glue of the modern Subject to its limits in order to test what sustains it. What Paul Ricoeur calls the “ontological vehemence” undergirding his theory of the narrative self would be, in da Silva’s eyes, a self-defeating (and self-deceptive) insistance on the transparency thesis and its promised interiority. By unpacking the modern “symbolic trinity” of the national, the racial, and the cultural, she refuses to overlook the predicament that narrativist approach to anti-racism cast on our collective emancipatory projects. Narrative activism based on racial identities serves as a form of auto-inclusion into the transparent social configuration governed by universality and historicity.

0 notes